Introduction

The Kom al-Ahmer/Kom Wasit Project of the Italian–Egyptian Archaeological Mission commenced in 2012 and is expected to last for ten years.Footnote 1 Work at the sites began after a series of systematic surveys in Beheira province conducted by Penelope Wilson in 2004 and Mohamed Kenawi from 2008 to 2010 (Kenawi Reference Kenawi2014; Wilson and Grigoropoulos Reference Wilson and Grigoropoulos2009). These surveys documented many archaeological sites, demonstrating that this area of the Nile Delta was extensively occupied during the Roman period. Four years of subsequent fieldwork have revealed that Kom Wasit was populated from the Late Dynastic period until the Late Hellenistic period. The nearby site of Kom al-Ahmer, which seems to have replaced the village of Kom Wasit, was inhabited from the end of the Hellenistic period and the Early Roman period through to the arrival of the Arabs, until at least the tenth century AD.

Kom al-Ahmer is located in the modern province of Beheira in the Western Delta, 44 km south-east of Alexandria, 7 km west of Mahmoudia, and 55 km east of the border of the Libyan Desert (Western Desert; see Figure 1).Footnote 2 The modern geography of the site is completely different from what it would have been in the past. The Delta region changed considerably between 1800, when Mohamed Ali Pasha began to implement land reclamation projects, and 1971, when the Aswan Dam was completed. In the Roman period, the site was probably located along the banks of the Rosetta branch of the Nile (known as the Bolbitine branch in Antiquity), which would have linked it directly with both the Mediterranean Sea and Middle and Upper Egypt. Kom al-Ahmer's position along one of the most important channels of the Nile would have facilitated its control of the surrounding territory from at least the Hellenistic period to the Roman or Early Byzantine periods. Indeed, the town can probably be identified as ancient Metelis, the only nomos capital not yet located precisely in the Delta area (Kenawi and Rossetti Reference Kenawi, Rossetti and Pirelli2013, 169–70; Marchiori Reference Marchiori, Platts, Pearce, Barron, Lundock and Yoo2014).

Figure 1. Kom al-Ahmer and Kom Wasit 2015 (The Italian–Egyptian Mission in Beheira, Israel Hinojosa Balino, CAIE).

The archaeological areas

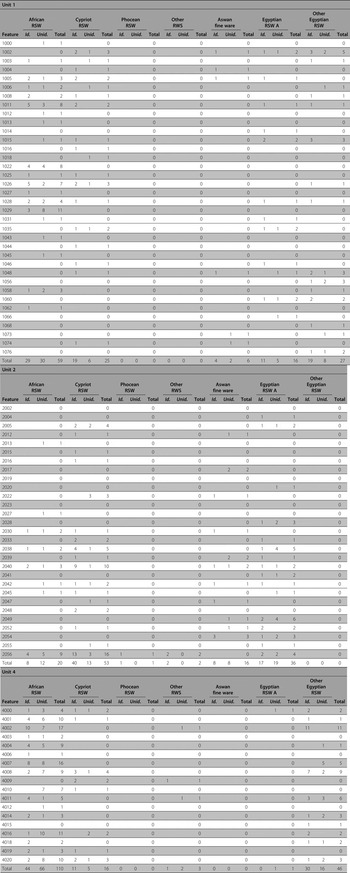

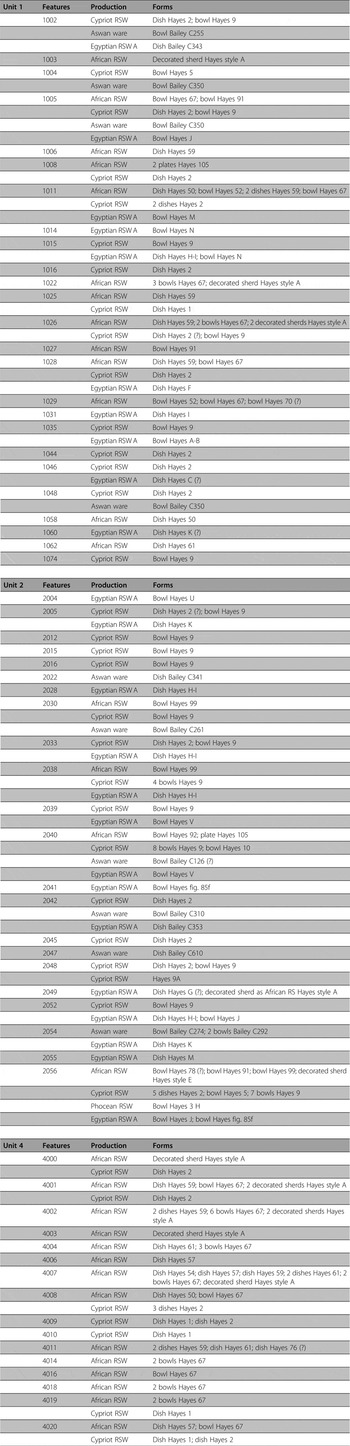

Excavations at Kom al-Ahmer began in 2012. To date, five archaeological areas have been opened, four of which have produced red slip ware (RSW): Unit 1 along the northern slopes of the second kom; Unit 2 along the southern slopes of this kom, Unit 3 on the summit of the kom, and Unit 4 to the west of the central mound, near the Roman baths excavated in 1942 by the Egyptian inspector Abd el-Mohsen el-Khashab (Reference El-Khashab1949) (Figure 2). The study of the pottery is based on 32,762 sherds, of which 472 are RSW (Table 1). As work is still in progress on the site the dataset presented here is not yet complete.

Figure 2. Kom al-Ahmer, 2015: Topographic map of the site with the location of excavated Units 1–5 (The Italian–Egyptian Mission in Beheira, Israel Hinojosa Balino and Giorgia Marchiori, CAIE).

Table 1 Pottery in Kom al-Ahmer contexts.

RSW imports were found in four separate areas of the site: Units 1, 2 and 3 are located on the highest parts of the site (Figure 2) where the sabakheen did not plunder the mud-brick structures, while Unit 4 is on a lower level. Unit 1 (10 × 13 m) was excavated to a depth of 5 m during the first year of investigations in 2012. Many structures were uncovered that warranted special attention, particularly a fired-brick basin coated in hydraulic plaster and a limestone floor covering an oval cistern coated in hydraulic plaster. Unfortunately, part of this floor and other layers were partially damaged by looting in 2013. Of the 15,007 sherds from this unit that were studied, 133 are RSW. The most interesting find in this unit was the limestone floor (Feature 1034) covering the cistern (Feature 1080). Its chronology is based primarily on the discovery of early Islamic glazed pottery and coins found in features on this floor (Features 1028, 1068, 1069, 1070, 1074 and 1075), which date to the first half of the seventh century. The finding of a Heraclius coin dated AD 618–28 in Feature 1050 is also interesting because this layer lies below the floor (Feature 1034). As all of the imported fine ware comes from the layers covering the floor, it clearly belongs to the final phases of occupation and abandonment.

Unit 2 (10 × 10 m) provided interesting and important insights into the last phase of habitation at Kom al-Ahmer and its subsequent total abandonment. The excavation unearthed a quadrangular structure likely related to the neighbouring Islamic cemetery. Of the 9,569 sherds from this unit that were studied, 163 are RSW. This unit has not been excavated beyond the funerary level. Regarding the chronology, sherds of early Islamic glazed pottery and coins dating to the first half of the seventh century were found. The discovery of an early Islamic cemetery provided some archaeological evidence for the state of affairs in the Delta in the early Arab period. No destruction marks or any other disturbances have been found in the archaeological layers.

In Unit 3 (10 × 10 m), which was excavated to a depth of 1 m, a single base sherd of Cypriot RSW was found. This unit is located on the top of the kom, to the south of Unit 1. Few objects were found in this unit because its excavation was not pursued. The stratigraphy in Unit 3 resembled that seen in the upper levels of Units 1 and 2, consisting of a natural deposit of Nile silt at least 3 m deep, which covered the second kom. This unit is not considered further in this article.

Of the 8,186 sherds found in Unit 4, 176 of RSW have been studied. This unit is located in the northwest area of the Roman baths, on an elevated level that was not extensively damaged by sabakheen in the previous century. Aerial photographs taken in the first part of the 2014 archaeological season revealed a complex structure here, and subsequent excavations brought to light a rectangular building with many small rooms, identifiable as shops. The excavated area is large (20 × 20 m) but not deep (0.5 m), because the abandonment levels and evidence of the last phase of habitation were found only a few centimetres under the topsoil. Work was slowed by the large number of coins found in this area, 450 in total. The pottery analysed in this article relates to the final phase of the structure. Removal of the topsoil uncovered Features 4000–10 as well as many tops of walls resulting in 8,183 sherds. The stratigraphic sequence of Features 4011–12 and 4014–20 extends more deeply in only two of the many rooms in the building. The excavation of this unit continued in 2015, but has not yet reached the floor levels. The study of the coins, the better preserved of which date to Theodosius II/Valentinian III (AD 425–35), has established its chronology more definitely. The study of the pottery and counts therefore presented here are based only on the sherds collected in 2014. Due to the enormous amount of sherd finds, it has not yet been possible to study the pottery from the 2015 excavation season.

The building uncovered in Unit 4 is more ancient in structure than the ones at Units 1 and 2. In contrast, Unit 2 is the most recent; the large quantity of Islamic glazed ware found in this area dates it to at least the tenth century AD. The RSW found in the upper levels of Unit 1 sheds light on the last phase of the settlement in this area, which appears to connect Units 2 and 4. Comparing the pottery found in these three units allows us to understand the evolution of imports here. Unit 3 is not considered in this study because the excavation only reached phases of the natural deposit covering the archaeological level.

Fine ware from Kom al-Ahmer

The study of pottery at Kom al-Ahmer involves the collection and cleaning of sherds and the reconstruction of the forms (where possible). The study of collected materials is divided into functional groups (fine ware, amphorae, utilitarian ware, lamps, etc.; see Figure 3) and sorted by provenance (Egyptian, foreign imports, etc.). Within the different groups, sherds are classified as either diagnostic (rims, bases, body sherds and handles with distinctive elements) and non-diagnostic (identifiable as belonging to a functional group by examination of the fabric alone.Footnote 3

Figure 3. Pottery from Kom al-Ahmer.

The excavation of Units 1, 2 and 4 yielded 32,762 pottery sherds for study, of which 1.4 per cent are red slip fine tableware. Altogether, 472 sherds of RSW have been studied and 364 are imported ware (Table 2). Of the latter, 53 per cent (194 sherds) have been identified with types (Table 3). Fine wares from Upper Egypt account for 39 per cent of the total (75 sherds), while the remaining 61 per cent (119 sherds) are fine ware from the Mediterranean basin. This paper focuses on fine ware imported from the Mediterranean and Upper Egypt.

Table 2 Tableware found in the excavation units.

Table 3 African RSW, Cypriot RSW, Phocean RSW, Aswan fine ware and Egyptian RSW A in the Kom al-Ahmer contexts.

With regard to the pottery produced along the Mediterranean coast, 189 sherds are African RSW (52 per cent of imported pottery and 40 per cent of all RSW at Kom al-Ahmer; 81 are dateable) and 94 sherds are Cypriot RSW or Late Roman (LR) D (26 per cent of imported pottery and 20 per cent of all RSW sherds; 70 are dateable). There is also a single Phocean RSW or LR C sherd and two unidentified rim sherds of purified clay. Finally, 51 sherds from Upper Egypt are Egyptian RSW A (14 per cent of imported pottery and 11 per cent of the RSW sherds; 28 are recognisable).

African RSW (Figure 4)

Although African RSW D was mainly produced in Africa Proconsularis, it is the best-known ware in use during the Late Roman period because it was exported throughout the Roman world. It is well represented at Kom al-Ahmer although excavations only began in 2012. The RSW from Tunisia predominates in the layers dated to the fourth and fifth centuries (Unit 4). None of the African RSW vessels have been preserved intact.

Figure 4. African RSW.

Unit 4

The majority of African fine tableware found at Kom al-Ahmer is from Unit 4 (110 sherds, of which 44 are recognisable).Footnote 4 The best-represented form is the dish type Hayes 67 with at least 21 rim sherds; this form is usually dated from the second half of the fourth century to the middle of the fifth. Hayes 59 is also present in this unit (6 sherds; see Figure 6.3). This form is well known in the Mediterranean basin and has been found in contexts dating from the fourth century to the beginning of the fifth. Four sherds are recognisable as Hayes 61, which is common in Mediterranean contexts; this form is dated to the fourth to fifth centuries and is widely found in Alexandria (Bonifay and Leffy Reference Bonifay and Leffy2002, 40, n. 6). This unit also yielded seven sherds with stamped decorations, a style of ornamentation dating to the second half of the fourth century and first half of the fifth (Hayes A ii and iii). The poor preservation of these sherds makes it impossible to associate them with a form. Among the sherds with stamped decorations is a base with two grid lozenges and the image of a bird at the centre (Feature 4002; see Figure 6.2). The bird is stylised and its species is difficult to identify.Footnote 5 The head is detached from the body and the wing and legs are depicted simply. The majority of stamped bird decorations are found on Hayes form E i; however, the bird's association with the lozenges could date it a few decades earlier. The context and shape of this very low ring foot suggest that the sherd could be identified as a Hayes 67 base. African RSW sherds found in Unit 4 are generally dated to the fourth and fifth centuries.

Unit 1

Unit 1 yielded 29 African RSW sherds. The forms found in this unit closely resemble those found in Unit 4. The type Hayes 67 is the most common with nine recognisable rim sherds; six are Hayes 59 dish sherds; four are decorated body and base sherds identifiable as Hayes style A. The most common forms of decoration are stamped designs of concentric circles and grid lozenges. Two poorly preserved rims with a dolphin appliqué decoration were found in Unit 1 (Features 1011 and 1029; see Figure 6.1) that may be compared with Hayes 52B. This shape appeared at the end of the third century and late versions are dated to the mid-fifth century. Unit 1 has yielded later forms than Unit 4, specifically Hayes 91/92 and 105. One rim is identified as Hayes form 91B/C, while a base with roulette decoration could be Hayes 91 or 92 (Hayes Reference Hayes1972, 140–45). Hayes 91 is very common throughout the Roman world and dates from the end of the fifth century to the first half of the sixth. Two Hayes 105 dish rims come from Feature 1008. A few open form examples in the studied layers date to the second half of the sixth century and first half of the seventh. The context of the two rims is covered by a layer containing Islamic ware (Feature 1011). This chronology will be confirmed when the study of the stratigraphy is complete. However, a longer stratigraphic sequence should apply to Unit 1, which contains imports from Africa Proconsularis dating from the fourth to the seventh century.

Unit 2

Unit 2 has only yielded eight African RSW sherds. The best-represented type is Hayes 99, one of the most common African slip ware forms found at Mediterranean sites. At Kom al-Ahmer three rim sherds date from about the mid-sixth century to the beginning of the seventh. The forms Hayes 91, 92 and 105 are also attested.

Cypriot RSW or Late Roman D (Figure 5)

After African RSW, the most common Mediterranean fine ware imports at Kom al-Ahmer are RSW from Cyprus and the southern coast of Turkey.Footnote 6 So far, 94 sherds have been unearthed, of which 70 are dateable. In contrast to African fine ware, Cypriot ware had a limited number of forms, and only five forms were found in the course of the excavation.

Figure 5. Cypriot RSW.

The count of Cypriot RSW sherds found in the three units contrasts with that of the African RSW. The largest quantity of Cypriot RSW came from Unit 2 while only 16 sherds have been found in Unit 4. Of these, ten sherds are dateable.

Examples of Hayes 1, the earliest shape, are rare and only four rim sherds of this type were found. This dish form was used during the late fourth and fifth centuries. Hayes 2 is more common and seven sherds of this form are recognisable (Figures 6.4–6.5). The rims are 18–32 cm in diameter and the bodies are usually decorated with roulette bands. Hayes H2 imports appears from the mid-fifth century and Cypriot RSW sherds are recognisable as this form has been found in shallow levels (Features 4000, 4001, 4008 and 4009). A single rim came from the fill of one of the rooms (Feature 4020).

Figure 6. African RSW: (1) Hayes 52B; (2) stamped decorations with two grid lozenges and a bird; (3) Hayes 59. Cypriot RSW: (4–5) Hayes 2. Aswan fine ware: (6) Bailey C225. Egyptian RSW A: (7) Hayes J.

Unit 1

Unit 1 yielded 25 Cypriot RSW sherds of which 19 are recognisable. Four different forms were found: Hayes 1, 2, 5 and 9, the most common of which was Hayes 2 with 11 sherds. The majority of the forms date from the third quarter of the fifth century to the early sixth century.

The second most attested form is Hayes 9 with six recognised sherds. This long-lived form was produced from the sixth century to the beginning of the seventh. Hayes 9 sherds from the site have different profiles and the majority have one or more irregular roulette decorations on the outer wall.

One example of Hayes 1 and one of Hayes 5 were found in Unit 1. A poorly preserved grooved base Hayes 5 has also been recognised in Feature 1004. This type of small bowl was in use from the second half of the sixth to the seventh century.

Unit 2

The majority of Cypriot RSW sherds found at Kom al-Ahmer came from Unit 2, which has yielded 53 catalogued sherds of which 40 are recognisable forms. Hayes 9 is represented by 28 sherds dated from the sixth century to the beginning of the seventh. The second most attested form is Hayes 2, with ten rim and base sherds. Hayes 10 is represented in this unit by a single rim (Feature 2040). This form is not widespread in the Mediterranean basin, but is quite common on the Levantine coast and in Alexandria (Meyza Reference Meyza2007, 70).

The first imports of Cypriot RSW are dated to the second half of the fourth century, and this type becomes dominant from the second half of the fifth century to the first half of the seventh. From the second half of the seventh century, concurrent with the Arab invasion, Cypriot tableware imports appear to decrease. Indeed, only two Hayes 5 sherds and one Hayes 10, which were produced until the end of the seventh century, have been found so far.

Phocean RSW or Late Roman C

Of the tableware from the Mediterranean basin, a single rim sherd of Phocean RSW has been brought to light. This sherd, which dates to the sixth century and comes from Unit 2 (Feature 2056), is recognisable as Hayes 3 (probably type H), one of the most common forms exported from western Turkish region. The diameter of this poorly preserved sherd was impossible to calculate, but three lines of roulette decoration are visible on the outer part of the rim. The context of this sherd contains a large number of fine ware imports that date from the sixth to the seventh century. These forms are very common along the Aegean coasts and present in the Levant and North African coastal regions, including Africa Proconsularis and Cyrenaica (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Bonifay, Marchand and Guédon2012, 88; Fulford Reference Fulford, Fulford and Peacock1984, 87; Hayes Reference Hayes1972, 329–36; Kenrick Reference Kenrick1985, 379–86; Reynolds Reference Reynolds, Cau, Reynolds and Bonifay2011b).

Egyptian RSW A and Aswan fine ware

Pottery imported from Upper Egypt has been primarily found in Units 1 and 2 with a single body sherd found in Unit 4, Feature 4000 (surface). Several different types of Upper Egyptian productions are attested at Kom al-Ahmer. These are typically characterised by a pink fabric, and the most common class is Egyptian RSW A. Types with a yellowish-white slip and a matt whitish-brown slip on the rim are also common (Bailey Reference Bailey1996, 55–59; Bailey Reference Bailey1998, 8–38; Hayes Reference Hayes1972, 387–97; Katzjäger Reference Katzjäger2014).

Unit 1

Unit 1 has yielded six sherds of Aswan fine ware, of which four rims are recognisable. The fabric of these better preserved bowls consists of hard pink clay with mica and small black-brown inclusions. The rims are coated with a matte brown slip. A rim from Feature 1002 is recognisable as Bailey form C225 (Figure 6.6), a small bowl dated from the sixth to eighth century in the context of El-Ashmunein, and to the seventh century (620–60) in Cesarea (Bailey Reference Bailey1998, 18). The other three rims resemble Bailey C350 and come from a context dateable from the fifth to the seventh century (Bailey Reference Bailey1998, 22).

Egyptian RSW A is attested in Unit 1 with 16 sherds, of which 11 are recognisable. The vessels are all open forms with a variety of profiles, including Hayes A-B, C (?), F, H-I, J (Figure 6.7), K, M, N, and Bailey C343. Most of the pottery from Upper Egypt is dated from the sixth to the eighth century.

Unit 2

Unit 2 has yielded 36 sherds of Egyptian RSW A and 16 sherds of Aswan fine ware, eight of which are recognisable forms. The chronology is usually wide, spanning the fifth to the seventh century and, for the forms Bailey C261 and C610, to the beginning of the eighth century. A chronology from the second half of the fifth to the seventh century is also confirmed for the 17 recognisable Egyptian RSW A sherds. A rim sherd from Unit 2 has been found in an El-Ashmunein context dated from the sixth to the eighth century. For this, it can be assumed that pottery from Upper Egypt was only imported later in the life of the kom. The absence of this ware in Unit 4 (the only sherd was found in the topsoil) indicates that these imports began after the second half of the fifth century.

The chronology of the units in relation to the study of the pottery

As mentioned above, the studied pottery from Unit 4 was found in the surface layers. However, it appears likely that the final phase of the life of the building occurred between the second half of the fourth century and the first half of the fifth.

The stratigraphy of Unit 1 is more complex. Mediterranean RSW dating from the fourth to at least the seventh century was found in the excavated layers. The presence of Islamic glazed ware sherds and pottery from Upper Egypt attests to activity at the area until at least the eighth century, and probably later.

The pottery found in the cemetery of Unit 2 post-dates that found in Units 1 and 4. The presence of pottery from Upper Egypt and glazed ware in the stratigraphy allows us to date the area to the Islamic period, the final phase before the abandonment of the kom. Above the archaeological structure in Unit 2 (as in Unit 1), only the natural silt was found.

RSW trade at Kom al-Ahmer

The trade of tableware has always been considered secondary and subsidiary to the main goods often exported in amphorae. Michel Bonifay (Reference Bonifay2010, 44–48; 2011, 19–21) has recently revised this assumption on the basis of the African RSW finds recently discovered in the Mediterranean basin. In fact, a large amount of African RSW does not correspond to an equally significant presence of African amphorae. Bonifay therefore hypothesises that the African tableware was either imported independently or was linked to other goods not transported in amphorae. These suggestions are in keeping with the finds at Kom al-Ahmer where the percentage of African RSW is more significant than that of amphorae produced in Africa Proconsularis or along the same trade route (a few examples of Tripolitanian amphorae are also present).

The Cypriot RSW requires a different explanation. Late Roman Amphorae (LRA) 1 imports, which were produced in the same area as the Cypriot RSW and traded along the same routes, are found in plentiful quantities at Kom al-Ahmer, dating from the second half of the fourth to the fifth century. Cypriot tableware was quite rare in this period; however, in later centuries the quantity of LRA 1 imports at Kom al-Ahmer remained constant while there was a marked increase in Cypriot fine wares. This indicates that fine ware imports were not exclusively linked with the transport of other goods; instead, their trade must have been independent or affected by other factors.

One of the main factors that influenced Cypriot tableware imports at Kom al-Ahmer was unquestionably the Vandals’ invasion of North Africa. The flow of imported African fine wares reflects the political events affecting Africa Proconsularis. Ware from this region represents almost a monopoly on fine pottery imports through the fourth century and the first half of the fifth (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Bonifay, Marchand and Guédon2012, 92). Around AD 430, the Vandals invaded North Africa and the annonaria system was shattered in the same century. These events heralded a significant reduction in African pottery imports not only at Kom al-Ahmer, but also from throughout the rest of Egypt and the Levant (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Bonifay, Marchand and Guédon2012, 88–89, 93–94; Bonifay Reference Bonifay and Attoui2011, 19).Footnote 7

Although the Metelis region was affected by these trade dynamics, the amount of imported vessels in general did not decline. The only change that occurred was in these imports’ areas of origin. From the mid-fifth century, a considerable amount of Cypriot RSW was imported. In particular, the first substitutes for African RSW were Cypriot RSW Hayes form 2 and its later evolution, Hayes 9.

Hayes 2 was an imitation of African RSW Hayes 84, which is so far unattested at Kom al-Ahmer. As noted above, the choice to import tableware from Cyprus and the Turkish coast was likely promoted by the already active trade with these regions.Footnote 8

After the conquest of Carthage and North Africa by the Byzantine Empire in 534, pottery imports from North Africa resumed in many Mediterranean contexts. However, the available data does not demonstrate this scenario at Metelis.Footnote 9 In fact, in comparison with the commercial activity indicated by the Cypriot RSW imports, trade between North Africa and this region of the Delta remained limited.

The end of Mediterranean RSW imports in Egypt and the Delta was probably determined by another moment of historical significance: the arrival of the Arabs in Egypt. After the conquest of Alexandria in 641, followed by the rest of Egypt soon after, the pottery record changed completely. RSW imports ceased with the arrival of glazed pottery, which is widely attested in the contexts of Unit 2 at Kom al-Ahmer, and in lesser quantities in Unit 1. Mediterranean RSW was also replaced by imports from Upper Egypt, which are attested from the fifth to the eighth century. The value of fine Mediterranean pottery in the economy of Egypt, the Delta and the Metelis region is evident both from the number of imports and from imitations produced by local potteries.

In conclusion, prior to the Vandals’ invasion, fine ware from the North African/Tunisian region was clearly preferred. After this invasion, however, the Delta and Metelis regions appear to have diversified their imports. The data collected at Kom al-Ahmer indicates that the trade route from Cyprus and southern Turkey became predominant (Figure 7), while the routes from North Africa remained present, but less significant.

Figure 7. The provenance of the tableware imports found in the excavation.

Finally, it is important to highlight the difference in the presence of African RSW at sites along the Nile during and after the Vandals’ invasion of Africa Proconsularis. As reported by Bonifay (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Bonifay, Marchand and Guédon2012, 93, 98–99), the presence of Cypriot RSW in these contexts was negligible, while that of African tableware was extensive. Bonifay concluded that the trade route must have changed, suggesting that, while the main route was previously fluvial, after the Vandals’ invasion the majority of African RSW was transported through the desert. According to this theory, the role of Kom al-Ahmer and other sites in the Delta region as trade ports between the Mediterranean basin and Middle and Upper Egypt probably declined or ceased after the mid-fifth century. Yet, the presence of Upper Egyptian fine ware at Kom al-Ahmer confirms that the Nile trade route was used during the seventh and eighth centuries. This may indicate that the trade role played by Delta towns changed from the use and sale of goods to simple consumption.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Society for Libyan Studies, which provided me with two grants enabling me to carry out this research; Eleni Schindler-Kaudelka and Gocha Tsetskhladze, who wrote the reference letters; and Michel Bonifay for his suggestions. Thanks are also due to Mohamed Kenawi and Giorgia Marchiori from the Italian–Egyptian Archaeological Mission at Kom al-Ahmer, Michele Asolati and Cristina Crisafulli for the information about coins. In Egypt, thanks are due to the Ministry of Antiquities (MSA) and the Inspectorate Office of Damanhour; the director of the MSA office, Mr Ahmed Kamel, the director of the excavation department, Mr Ashraf Abdel Rahman; and various inspectors who worked with us. We are also grateful for the visit of the Minister of Antiquities, Dr Mamdouh el-Damaty, to Kom al-Ahmer in July 2014. I am grateful to Mohamed Kenawi and Tiffany Chezum (Oxford University) for editing the final draft of this work.