Introduction

Depression is one of the most common complications of pregnancy [Reference Gavin, Gaynes, Lohr, Meltzer-Brody, Gartlehner and Swinson1]. It has been linked to heightened risk of suicide for the mother [Reference Lee, Tien, Bai, Lin, Yin and Chung2], sleep disturbances [Reference Dias and Figueiredo3], malnutrition, decreased growth rates for the infant [Reference Rahman, Iqbal, Bunn, Lovel and Harrington4], and long term effects such as psychoemotional problems [Reference Fransson, Sörensen, Kunovac Kallak, Ramklint, Eckerdal and Heimgärtner5, Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman and McCallum6],and low cognitive development for the child [Reference Urizar and Muñoz7]. Despite the fact that about one in five mothers are depressed in the peripartum period [Reference Yin, Sun, Jiang, Xu, Gan and Zhang8, Reference Shorey, Chee, Ng, Chan, Tam and Chong9], the condition often goes underdiagnosed and untreated [Reference Smith, Rosenheck, Cavaleri, Howell, Poschman and Yonkers10, Reference Earls11].

Although the literature has mainly focused on the postpartum period, postpartum depression is no longer a distinct diagnosis in the Diagnostic Statistic Manual-5 (DMS-5). Instead, a depressive episode that emerges during pregnancy or during the first 4 weeks postpartum is classified as a major depressive disorder with peripartum onset [12]. ICD-11 describes peripartum depression (PPD) as a syndrome of mental and behavioral features, mostly depressive symptoms, commencing during pregnancy or within 6 weeks from delivery [13]. In research settings, this period is often extended to include the first year after delivery [Reference McCall-Hosenfeld, Phiri, Schaefer, Zhu and Kjerulff14, Reference Woolhouse, Gartland, Perlen, Donath and Brown15].

It is considered that the sudden decrease in the levels of reproductive hormones after the delivery plays a crucial part in the pathophysiology of depression with postpartum onset [Reference Hendrick, Altshuler and Suri16], a mechanism that may be particularly relevant in women who have previously shown sensitivity to hormones through e.g., premenstrual syndrome (PMS), previous depression or migraine [Reference Wikman, Axfors, Iliadis, Cox, Fransson and Skalkidou17]. Nevertheless, studies are showing no difference in the concentrations of estrogen and progesterone between women who developed postpartum depression and women who did not [Reference Bloch, Schmidt, Danaceau, Murphy, Nieman and Rubinow18, Reference Mehta, Newport, Frishman, Kraus, Rex-Haffner and Ritchie19], indicating that postpartum depression does not depend solely on hormone levels, but also on women’s sensitivity to their fluctuations [Reference Schiller, Meltzer-Brody and Rubinow20]. Similarly, ovarian hormones are found in identical levels in women with PMS and controls [Reference Rapkin and Akopians21].Thus, researchers hypothesize that there is a specific subgroup of women with high sensitivity to hormonal fluctuations which can occur during different reproductive phases, who are susceptible to developing mental health symptoms during these phases [Reference Mehta, Newport, Frishman, Kraus, Rex-Haffner and Ritchie19, Reference Nielsen, Stika and Wisner22–Reference Payne, Palmer and Joffe24]. Furthermore, several studies have noted an association between postpartum depression and PMS [Reference Stewart and Boydell25–Reference Payne, Roy, Murphy-Eberenz, Weismann, Swartz and McInnis29], as well as between postpartum depression and perimenopausal depressive symptoms [Reference Stewart and Boydell25, Reference Payne, Roy, Murphy-Eberenz, Weismann, Swartz and McInnis29, Reference Gregory, Masand and Yohai30], suggesting that a history of a depressive episode during a hormonal transition phase might predict the occurrence of another episode during a different period of hormonal fluctuations.

Oral contraceptives (OCs) are the most common type of hormonal contraceptives in the Nordic countries [Reference Hognert, Skjeldestad, Gemzell-Danielsson, Heikinheimo, Milsom and Lidegaard31, Reference Lindh, Skjeldestad, Gemzell-Danielsson, Heikinheimo, Hognert and Milsom32]. There are two types of OCs, progestin-only pills (POPs) and combined OCs (COCs), containing both a type of estrogen as well as a progestin. Research showcases that monophasic OCs result in hormonal fluctuations, as endogenous estradiol levels decrease during active pill phase while they dramatically increase during placebo phase [Reference Rodriguez, Casey, Crossley, Williams and Dhaher33]. Perceived mental side effects is one of the reasons why women discontinue the usage of OCs in Sweden [Reference Lindh, Blohm, Andersson-Ellström and Milsom34], affecting an estimated 4–10% of users [Reference Poromaa and Segebladh35]. However, a Swedish register based study showed no direct association between COCs and depression [Reference Lundin, Wikman, Lampa, Bixo, Gemzell-Danielsson and Wikman36]. Additionally, a recent meta-analysis concludes no increase in depressive symptoms in adult users of hormonal contraceptives [Reference de Wit, de Vries, de Boer, Scheper, Fokkema and Schoevers37]. Nevertheless, a randomized controlled trial noted a causal effect of COCs on depressed mood [Reference Petersen, Kearley, Ghahremani, Pochon, Fry and Rapkin38], while two Danish studies showcase that the use of hormonal contraceptives, including OCs, is associated with an increased risk of depression especially when initiated in adolescence [Reference Skovlund, Mørch, Kessing and Lidegaard39] or postpartum [Reference Larsen, Ozenne, Mikkelsen, Liu, Bang Madsen and Munk-Olsen40]. Interestingly, a randomized controlled trial noted that COCs might cause mood changes such as mood swings in the intermenstrual phase, while in the premenstrual phase they were associated with improved mood [Reference Lundin, Danielsson, Bixo, Moby, Bengtsdotter and Jawad41].

Research on the association between mood disturbances caused by hormonal contraceptives and PPD is scarce and has mixed results. First, women who had experienced both PMS and postpartum depression exhibited a higher likelihood of experiencing side effects from OCs compared to women who had experienced only postpartum depression [Reference Dennerstein, Morse and Varnavides42]. Then, other studies have also identified an association between mood symptoms from hormonal contraceptives and postpartum mood disorders [Reference Bloch, Rotenberg, Koren and Klein28, Reference Larsen, Mikkelsen, Lidegaard and Frokjaer43]. Meanwhile, a recent study reported no significant association between mood swings from OCs and postpartum depression [Reference Nayak, Jaggernauth, Jaggernauth, Jadoo, Jagmohansingh and Jaggernauth44].

Understanding the predictors and correlates of PPD is crucial, as it can pave the way for high-risk identification, earlier diagnosis and intervention, particularly since PPD is commonly underdiagnosed. This can further advance our understanding of PPD pathophysiology and its possible subtypes [Reference Wikman, Axfors, Iliadis, Cox, Fransson and Skalkidou17, Reference Chechko, Stickel, Losse, Shymanskaya and Habel45]. Aiming to address the gap in the existing literature we seek to present a variable of potential interest for future PPD prediction models. Thus, this study examined whether women with self-reported mood swings during OC use had higher risk of reporting depressive symptoms at different time points during the peripartum period compared to women without such experiences. We furthermore examined the association between self-reported mood swings during OC use in relation to newly developed peripartum depressive symptoms (PPDS) in different time points in the peripartum period.

Methods

The present study uses data from Mom2B study, a Swedish national longitudinal cohort study focusing on the development of prediction models for peripartum complications that utilizes a smartphone application for data collection [Reference Bilal, Fransson, Bränn, Eriksson, Zhong and Gidén46]. Mom2B study fulfills the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requirements and the ethical approval was granted from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (dnr: 2019/01170, with amendments).

Study population

All adult Swedish-speaking women, pregnant or within 3 months postpartum, were eligible to participate. Recruitment was conducted using social media campaigns, alongside posters and brochures handed out in primary and maternal healthcare centers throughout Sweden. The recruitment process started when the Mom2B application was launched in November 2019 and is still ongoing. Each participant got information about the aims of the study, the confidentiality and security of their data before giving consent and registering. Participants could withdraw consent at any time without the need to provide a reason.

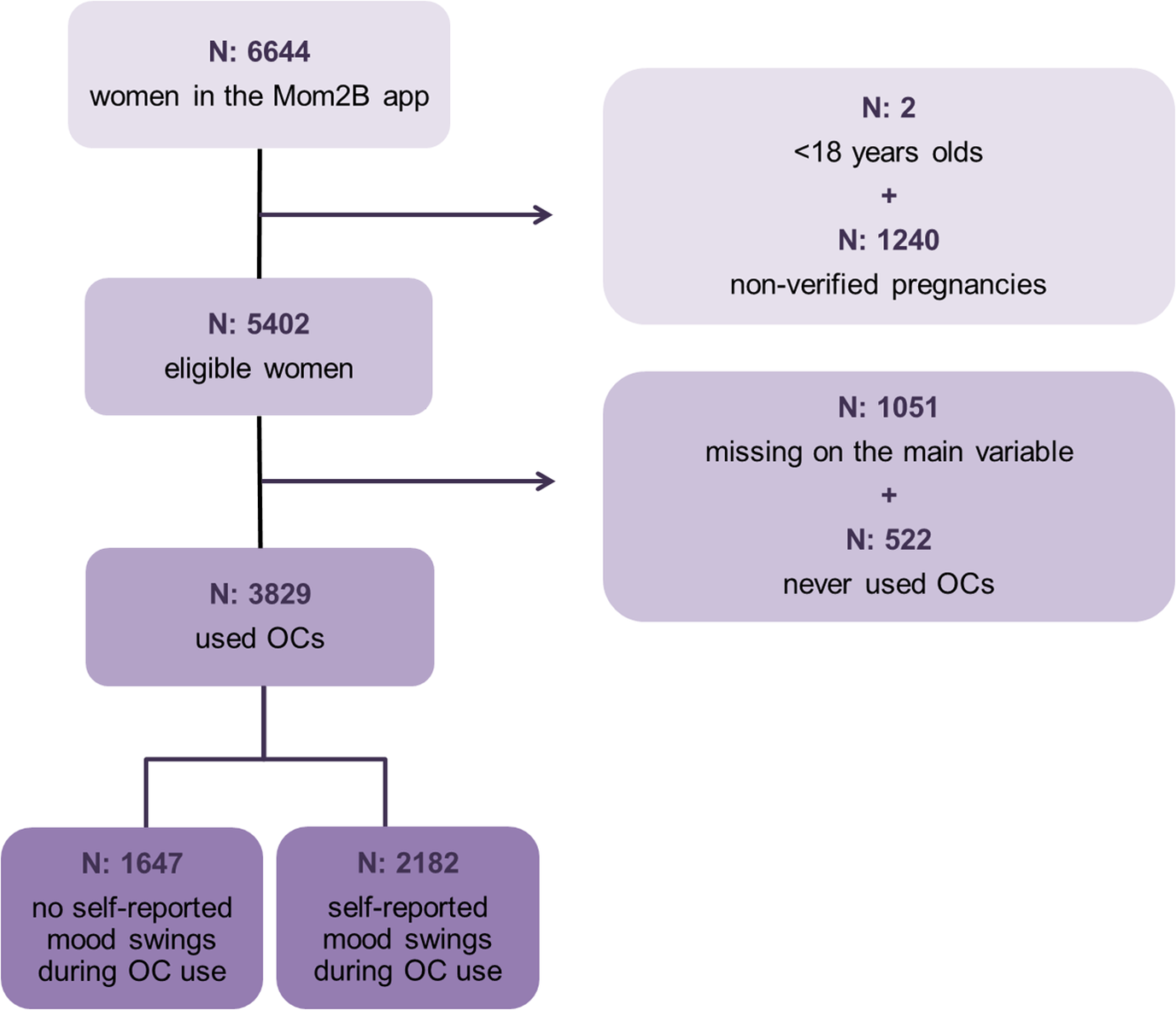

For the present study, we analyzed data collected between November 2019 and December 2024, including all women enrolled in the study thus far (n = 6644). As shown in Figure 1, nonverified pregnancies by the pregnancy registry, women who did not answer to the question about OCs and women who had never taken OCs were excluded from the analysis. Consequently, the sample used for analysis consisted of 3829 women.

Figure 1. Flowchart. OCs, oral contraceptives.

Exposure

To enhance generalizability, we included women with milder mood fluctuations, not only those with a clinical depression diagnosis while on OCs; thus, we chose our exposure to be self-reported mood swings during OC use which was assessed with the question: “Have you had mood swings from birth control pills?.” Women could choose between the following answers: “No,” “Yes” and “Have never used birth control pills.”

Outcome and covariates

The outcome of interest was PPDS. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). EPDS is a 10-item self-report questionnaire made for postpartum depression screening [Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky47]. Depending on the symptom severity, each response is scored from 0 to 3; therefore, total EPDS scores vary from 0 to 30. A cut-off of 13 was used for pregnant women, while a cut-off of 12 was used for postpartum women, in line with the Swedish validation of EPDS for pregnancy and postpartum stages, respectively [Reference Rubertsson, Börjesson, Berglund, Josefsson and Sydsjö48,Reference Wickberg and Hwang49]. EPDS was administered via the Mom2B application. For our analysis, we utilized EPDS scores from six different time points (gestational weeks 12–22, 24–34, 36–42 and postpartum weeks 6–13, 14–23, and 24–35).

The confounders taken into account were age at registration, BMI before pregnancy, highest level of education completed, history of depression, and medical indications for the use of OCs including any among the following: PMS, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and endometriosis.

Statistical analyses

Demographic and clinical characteristics (including PMS, PCOS, and endometriosis) were compared between exposure groups using Pearson’s chi-square test. In order to compare the distributions of the total EPDS score on each time point between the two groups, we used Mann–Whitney U Test for each of the six different time points, as the EPDS scores were not normally distributed. We evaluated the differences in rates of those above the EPDS cut-off score at each time point in relation to self-reported mood swings during OC use using Pearson’s chi-square test for each of the six time points. In order to focus on the newly developed PPDS, we ran the same analysis excluding women having EPDS scores above the cut-off on the previous time point. This analysis was applied to all time points, except the first pregnancy time point as we do not have an EPDS score prior to gestational week 12, thus making it impossible to exclude women with previous EPDS scores above the cut-off.

To estimate the association between self-reported mood swings and PPDS, we conducted logistic regressions at all time points for each covariate individually and for the full multivariable model. The outcome was dichotomized EPDS; predictors were self-reported mood swings and confounders. To examine the association with newly developed PPDS, we ran logistic regressions at all time points except the first one, excluding those who already had EPDS above the cut-off. Each regression was performed both as a crude model and as an adjusted model including the confounders mentioned above as predictors covariates. Missing data were accounted for via multiple imputation with 50 imputed datasets.

SPSS version 29.0 was used for the statistical analyses. Statistical significance was set at a p value <0.05.

Results

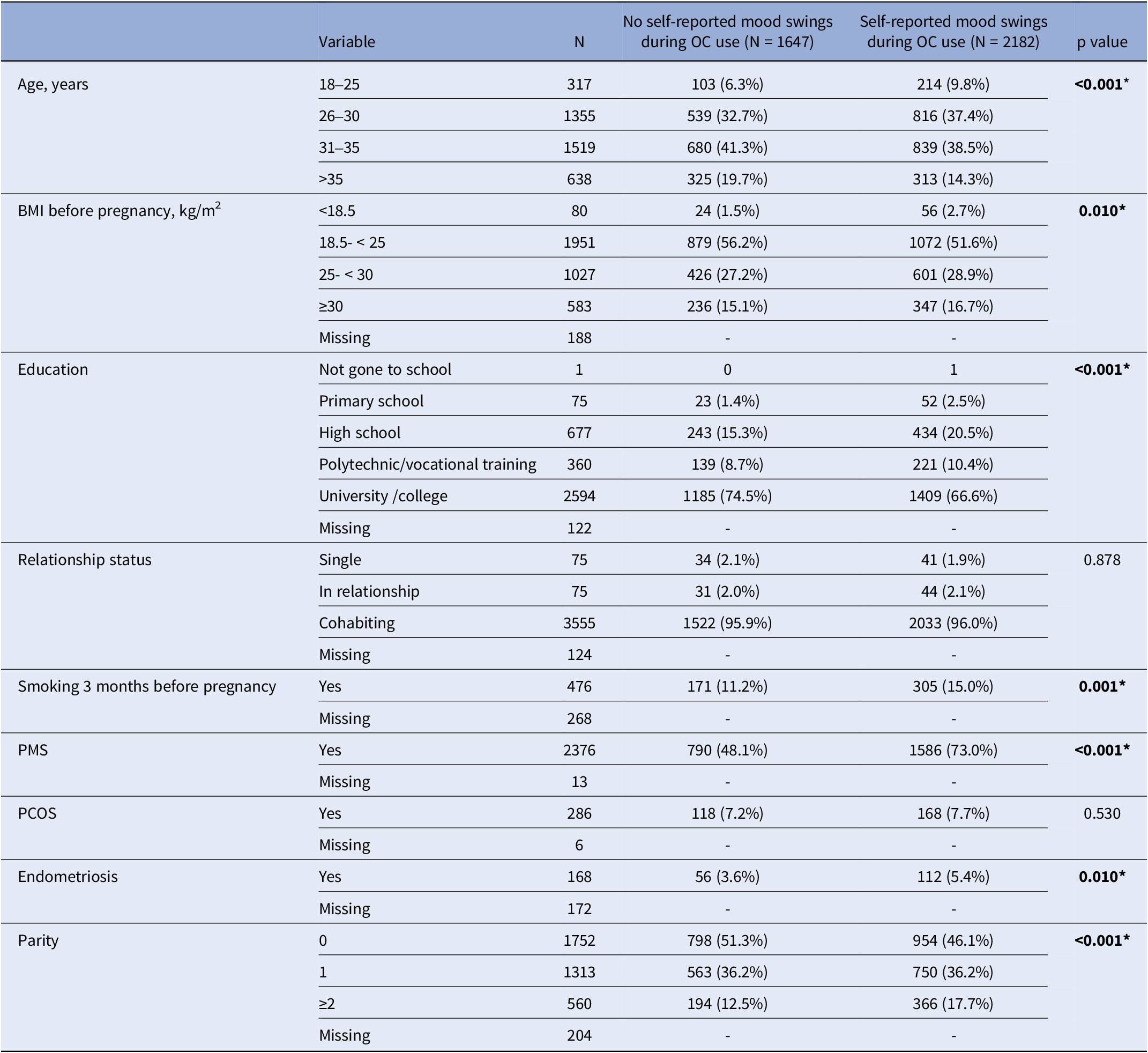

Among the 3829 women who had used OCs, 2182 (57%) reported experiencing mood swings. Table 1 showcases demographics and clinical characteristics among the two exposure groups. Women with self-reported mood swings during OC use had higher rates of endometriosis (p = 0.010) and PMS (p < 0.001). Additionally, they had lower or higher than normal BMI before pregnancy (p = 0.010), lower levels of education (p < 0.001), and higher rates of smoking the last three months before pregnancy (p = 0.001) in comparison to women with no self-reported mood swings.

Table 1. Demographics and clinical characteristics of the participants by groups; no self-reported mood swings during OC use and self-reported mood swings during OC use

BMI, body mass index; OCs, oral contraceptives; PCOS, polycystic ovary syndrome; PMS, premenstrual syndrome. *p<0.05

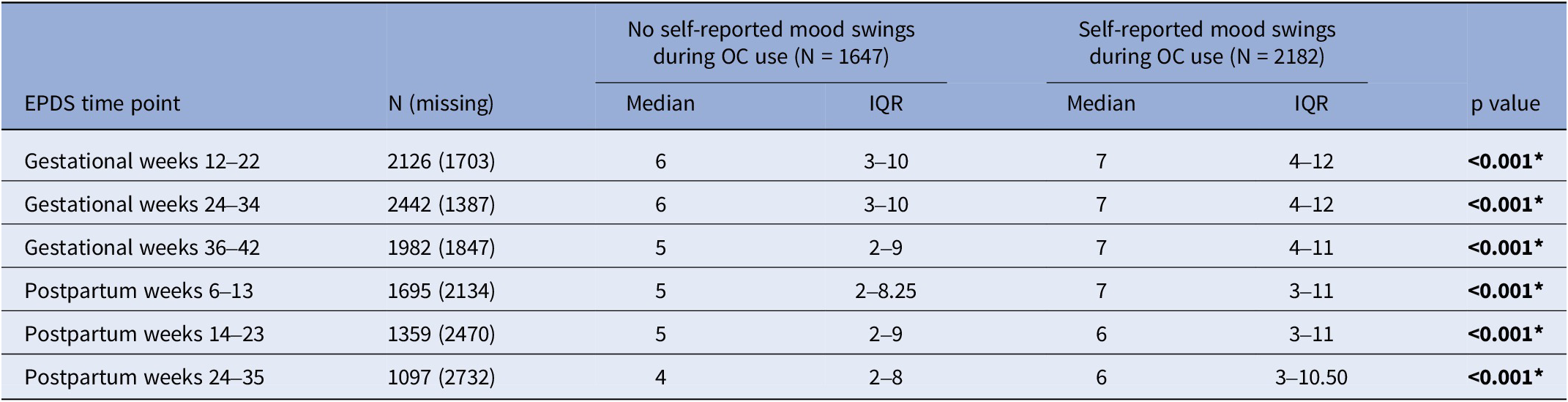

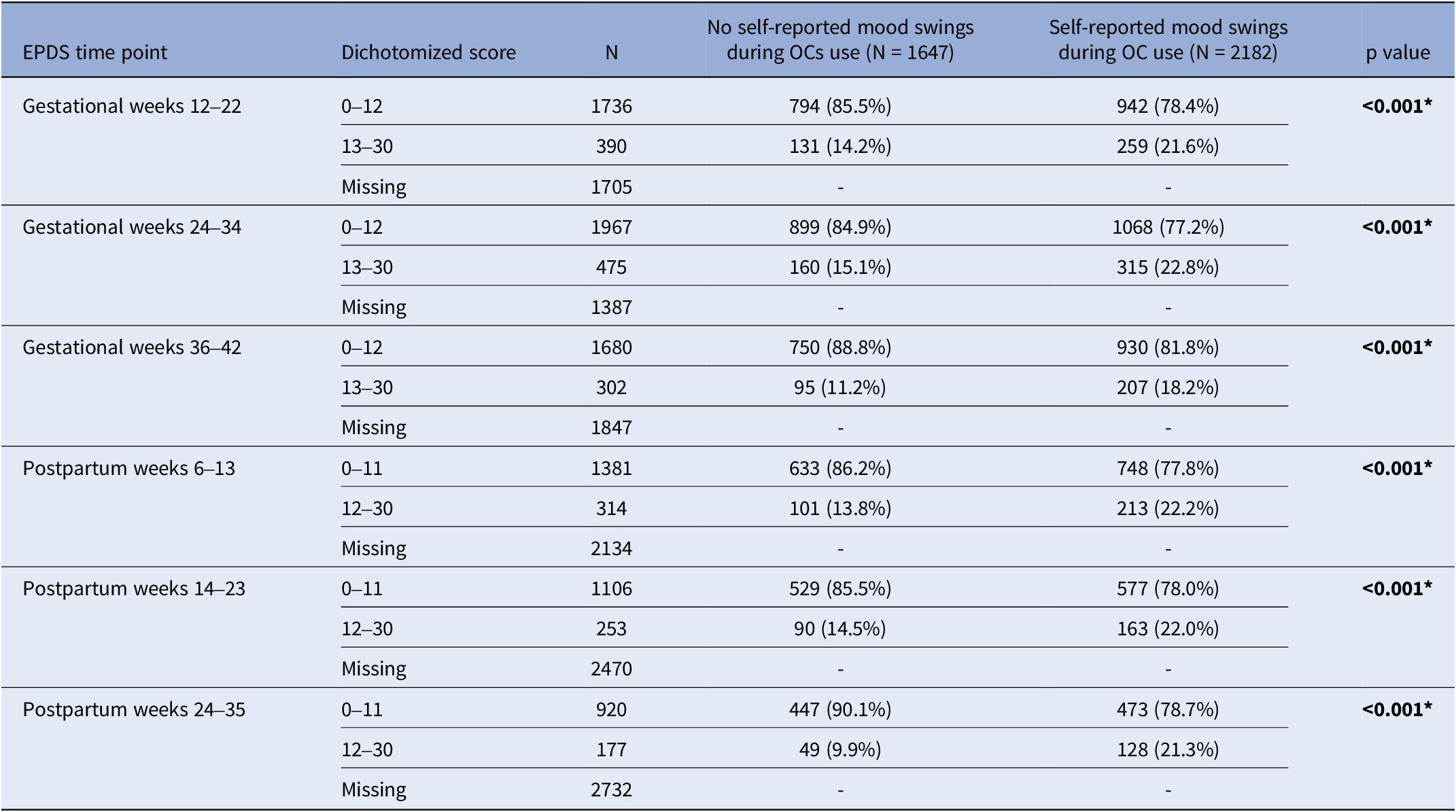

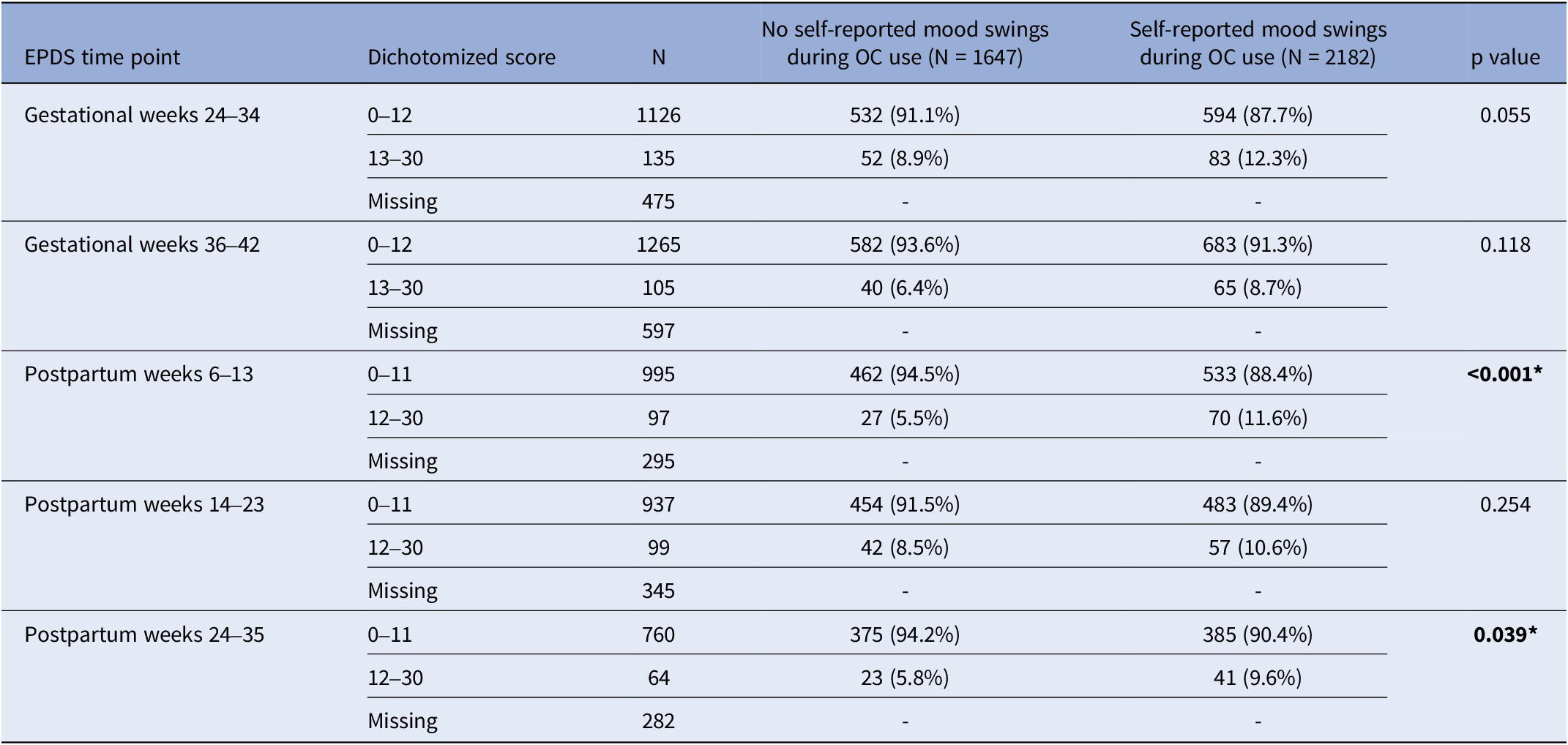

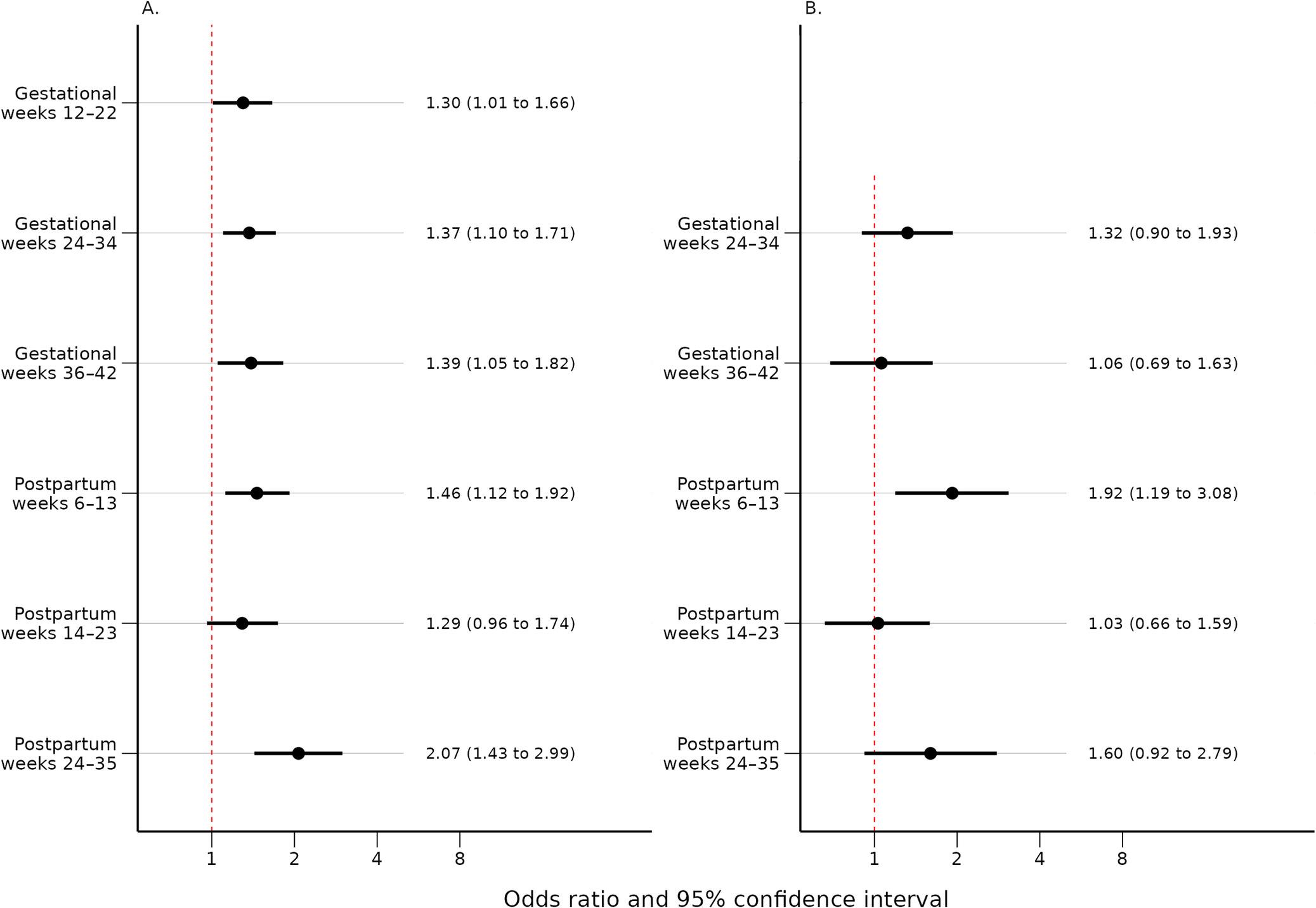

Women with self-reported mood swings during OC use had statistically significant higher median EPDS total score at every time point throughout pregnancy and postpartum compared to women who had not (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Self-reported mood swings during OC use were associated with dichotomized EPDS scores in every pregnancy and postpartum time point (p < 0.001) (Table 3). After excluding women having EPDS scores above the cut-off on the previous time point, the association remained significant only in postpartum weeks 6–13 (p < 0.001) and 24–35 (p = 0.039) (Table 4). The adjusted logistic regressions confirmed the patterns observed above. Self-reported mood swings during OC use were associated with higher odds of scoring above the cut-off on EPDS in all pregnancy (ORs between 1.30 and 1.39) and postpartum (ORs between 1.46 and 2.07) time points, except for postpartum 14–23 (Figure 2A). After excluding women having EPDS scores above the cut-off on the previous time point, self-reported mood swings during OC use were associated with higher odds of newly developed PPDS only in postpartum weeks 6–13, with an OR of 1.92 (95% CI, 1.19–3.08) (Figure 2B).

Table 2. Median EPDS scores and IQR during pregnancy and postpartum by groups: no self-reported mood swings during OC use and self-reported mood swings during OC use

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; IQR, interquartile range; OCs, oral contraceptives. *p<0.05

Table 3. Number of women and percentages for normal and high EPDS throughout pregnancy and postpartum by groups: no self-reported mood swings during OC use and self-reported mood swings during OC use

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; OCs, oral contraceptives. *p<0.05

Table 4. Number of women and percentages for normal and high EPDS throughout pregnancy and postpartum by groups: no self-reported mood swings during OC use and self-reported mood swings during OC use, after exclusion of women with high EPDS scores on the previous time point (≥13 for the gestational time points and ≥ 12 for the postpartum time points)

EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; OCs, oral contraceptives. *p<0.05

Figure 2. (A) Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between self-reported mood swings during OC use and an EPDS score above cut-off for each time point adjusted for age, BMI, education, medical indications for OCs, and history of depression. (B) Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association between self-reported mood swings during OC use and an EPDS score above cut-off for each time point, after exclusion of women with high EPDS scores on the previous time point (≥13 for the gestational time points and ≥ 12 for the postpartum time points). Adjusted for age, BMI, education, medical indications for OCs, and history of depression. BMI, body mass index; EPDS, Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; OCs, oral contraceptives.

Discussion

More than half of the OC users in our study reported mood swings during OC use. Although higher than expected, mental side effects have been shown to be the most commonly reported adverse effects and a leading cause of discontinuation of hormonal contraception [Reference Lindh, Hognert and Milsom50, Reference Jaskari, Tekay, Saloranta, Korjamo, Heikinheimo and Gyllenberg51].

The results of our study point toward a robust association between self-reported mood swings during OC use and the presence of significant depressive symptoms throughout all of pregnancy and most of the postpartum time points. Interestingly, another major finding of our study was that women with self-reported mood swings during OC use have twice the risk of newly developed PPDS during postpartum weeks 6–13.

Few studies have explored this association throughout pregnancy and the postpartum period. Our results are in line with a previous study that noted that history of mood swings from OCs was a significant risk factor for mood disorders during postpartum weeks 6–8 [Reference Stewart and Boydell25]. Furthermore, a recent Danish cohort study researching hormonal contraceptives showcased a link between history of depression associated with hormonal contraceptives and postpartum depression. The association was maintained even when including those depressed during pregnancy [Reference Skovlund, Mørch, Kessing and Lidegaard39].

Although it is unclear whether OCs create a hypo- or hyper-hormonal state in the brain [Reference Casto, Jordan and Petersen52], OC users’ endogenous estradiol and progesterone levels are lower than among naturally cycling women [Reference Frye53, Reference Schmidt, Hennig and Munk54] and the levels of inflammatory markers higher [Reference Larsen, Cox, Colbey, Drew, McGuire and Groth55, Reference Divani, Luo, Datta, Flaherty and Panoskaltsis-Mortari56]. In parallel, women after delivery present with decreased levels of estradiol and progesterone [Reference Kuijper, Ket, Caanen and Lambalk57, Reference Dukic, Johann, Henninger and Ehlert58], while some inflammation markers rise and are even found to be increased in those with postpartum depression [Reference Bränn, Fransson, White, Papadopoulos, Edvinsson and Kamali-Moghaddam59], indicating a possible common pathophysiological mechanism. There might of course be other mechanisms by which OCs impact on mood, such as higher levels of estrogen receptor stimulation, the choice of synthetic progestogen, or the lower androgen levels. It cannot be ruled out that depressive symptoms during pregnancy could be due to the first of these mechanisms, while peripartum depressive symptoms to the latter.

Our findings pinpoint strongest associations during the early postpartum and late postpartum time points. In the early postpartum, estrogens and progesterone suddenly drop [Reference Dukic, Johann, Henninger and Ehlert58], while oxytocin rises [Reference Jobst, Krause, Maiwald, Härtl, Myint and Kästner60]. Additionally, the last postpartum time point could be associated with the ending of breastfeeding and thus drop in oxytocin and prolactin, or even the start of hormonal contraception [Reference Jobst, Krause, Maiwald, Härtl, Myint and Kästner60]. As a result, both periods represent phases of great hormonal fluctuations, leaving many women vulnerable to mood disturbances. Bloch et al. pharmacologically imitated the fluctuations of sex hormones that normally occur during pregnancy and postpartum on euthymic women and found that, in those with a history of postpartum depression, depressive symptoms increased when estrogen and progesterone were introduced and peaked during the phase when both hormones were withdrawn [Reference Bloch, Schmidt, Danaceau, Murphy, Nieman and Rubinow18]. This aligns especially with our finding that women with self-reported mood swings during OC use had a higher risk of newly developed PPDS during postpartum weeks 6–13. It is also in line with another Mom2B substudy showcasing that women with PMS exhibited higher risk of developing PPD during all the postpartum time points [Reference Schleimann-Jensen, Sundström-Poromaa, Meltzer-Brody, Eisenlohr-Moul, Papadopoulos and Skalkidou61]. These findings indicate that a certain subgroup of women have an abnormal response to the abrupt decrease of sex hormones following delivery and present more evidence for the existence of a hormonal sensitive subgroup of women to a growing body of literature.

The biological mechanism behind this hormonal sensitivity is yet to be fully understood. Some researchers suggest that it might be attributed to a dysregulation of estrogen signaling as most of the116 transcripts that were found to be differentially expressed between women with postpartum depression and euthymic women in late pregnancy were linked to it [Reference Mehta, Newport, Frishman, Kraus, Rex-Haffner and Ritchie19]. Another study showed that women who developed postpartum depression exhibited attenuated connectivity in the anterior cingulate cortex, amygdala, hippocampus, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex despite having similar derivatives of progesterone levels to healthy comparison subjects [Reference Deligiannidis, Sikoglu, Shaffer, Frederick, Svenson and Kopoyan62]. Although women with and without postpartum depression exhibit comparable levels of allopregnanolone, this metabolite of progesterone has been associated with the pathophysiology of reproductive mood disorders such as PMDD and PPD by inducing affective dysregulation in a susceptible group of women [Reference Schiller, Meltzer-Brody and Rubinow20, Reference Schiller, Schmidt and Rubinow63]. Clinical trials have also highlighted the robust antidepressant effect of Brexanolone, a synthetic allopregnanolone analog [Reference Meltzer-Brody, Colquhoun, Riesenberg, Epperson, Deligiannidis and Rubinow64], which is now an FDA-approved treatment of postpartum depression [Reference Powell, Garland, Preston and Piszczatoski65].

Clinical implications and future studies

Our results indicate that self-reported mood swings during OC use is a strong risk factor for PPD. Although causality cannot be assumed, this finding should be regarded as an indicator worth considering in clinical assessments. Incorporating a brief question about mood disturbances during OC use into medical intake during the early stages of pregnancy could help identify high-risk women, ensuring earlier diagnosis and intervention for women at high risk of developing PPD.

Future studies could investigate if mood deterioration after the use of specific types of OCs is more strongly associated with PPD. Categorizing participants based on OC type yields greater precision in assessing the relationship between mood disturbances from OCs and PPD. Additionally, other hormonal contraceptives, such as intrauterine devices (IUDs) or injections, should be investigated separately. Finally, it would be interesting for future studies to examine the association between mood swings during OCs and depressive symptoms during other periods of significant hormonal fluctuations, such as menarche or perimenopause.

Strengths and limitations

The study used data from the national Mom2B project, a Swedish longitudinal study that is being conducted via a smart phone application, which enables the close monitoring of a national, population-based cohort of participants from pregnancy to up to 1 year postpartum.

The use of validated instruments for the assessment of depressive symptoms and controlling for several confounding factors are strengths of the present work. The replication of known associations, such as with history of depression, high BMI, and medical indications for OCs (full tables can be found in the Supplementary Material) is also seen as a strength, as they are in line with previous studies [Reference Johansen, Stenhaug, Robakis, Williams and Cullen66–Reference Cao, Jones, Tooth and Mishra68]. A novelty of the current work is the subanalysis that assessed the newly developed PPDS at each peripartum time point, showcasing the early postpartum one as a period of particular vulnerability for women with self-reported mood swings during OC use.

Limitations should also be considered when interpreting our findings. Firstly, as the Mom2B application is only available in Swedish, our cohort mainly consists of women born in Sweden, influencing the generalizability of our results. Additionally, the study’s focus on perinatal mental health may have attracted women with prior mental health issues. Moreover, it should be noted that there is a considerable amount of missing data relating to the EPDS questionnaire in the last postpartum time points. This may be due to some participants not having reached that stage of postpartum alongside time constraints and survey fatigue [Reference Wierenga, Pagoni, Skalkidou, Papadopoulos and Geusens69]. To address this problem, we used 50 multiple imputations to handle the missing in each time point. Furthermore, the specific type of OCs that each woman has used (that is, POPs or COCs) was not specified in the related surveys. The heterogeneity of OCs makes it hard to draw more precise conclusions. Lastly, mood swings were evaluated based on a self-report question that was asked during pregnancy. Thus, we can only capture whether OC users perceive the mood swings to be caused by the contraceptive method – not whether there is an actual causal relationship.

Conclusions

In summary, this Mom2B substudy showcases that women with self-reported mood swings during OC use had higher risk of depressive symptoms across the peripartum period, but also notably increased risk of newly developed PPDS during the early postpartum. Our findings contribute to the growing body of evidence indicating a hormonal sensitive subgroup of women who struggle in their response to hormonal fluctuations and suggest that self-reported mood swings during OC use could be used when predicting and identifying high-risk women. Furthermore, our work highlights the importance of incorporating questions about each woman’s experience with OCs in the routine check-ups during early pregnancy.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2025.10135.

Data availability statement

The data supporting this research are available from the authors on a reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all women who participated in the Mom2B study for their invaluable contributions to this research. We are particularly grateful to Dr. Richard A. White for the valuable statistical advice and to Natasa Kollia for the data management. We also wish to acknowledge Ulf Elofsson and Molly Hanson for coordination of the Mom2B study and their practical support with the dataset, as well as the Swedish Network for National Clinical Studies in Obstetrics and Gynecology (SNAKS).

Financial support

The Mom2B project has received funding from the Swedish Research Council (grant numbers 2020-01965, 2024-03199), the Swedish Brain Foundation (grant numbers FO2021-0161, FO2022-0098), the Swedish state under the ALF-agreement, the Olle Engkvists Foundation (224-0064), and the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. H.W. is financially supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG – project: IRTG2804). Fe.G. is financially supported by the European Union (MSCA postdoctoral fellowship – project 101063659) and Research Foundation Flanders (FWO senior postdoctoral fellowship – project 1239223 N). Fr.G. is a Sigrid Juselius postdoctoral fellow with additional postdoctoral funding from Finska Läkaresällskapet. The data handling was enabled by resources provided by the National Academic Infrastructure for Supercomputing in Sweden (NAISS), partially funded by the Swedish Research Council through grant agreement no. 2022-06725.

Competing interests

Fr.G. has participated in scientific meetings arranged by Gedeon Richter and received payments for lectures from Bayer AG. The rest of the authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.