Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing international interest in exploring young children’s musical experiences in everyday family contexts, particularly the musical interaction (hereinafter, MI) occurring between parents and children. This body of research includes a range of approaches and focal points. One strand explores instinctive musical communication between adults and young children, identifying features and patterns referred to as communicative musicality (Malloch & Trevarthen, Reference MALLOCH and TREVARTHEN2009). Another examines the types of musical activities used in parent–child interaction – primarily singing, listening, and instrumental play (e.g., Custodero, Reference CUSTODERO2006; Denac, Reference DENAC2008) – as well as their frequency (Custodero & Johnson-Green, Reference CUSTODERO and JOHNSON-GREEN2003; de Vries, Reference DE VRIES2009; Evans et al., Reference EVANS, DEAN and BYETT2022). In parallel, some studies have addressed the potential developmental benefits of these activities when compared to other forms of leisure (Williams et al., Reference WILLIAMS, BARRETT, WELCH, ABAD and BROUGHTON2015).

A complementary line of inquiry focuses on the functionality of music within the parent–child relationship. In this view, musical expression helps adults navigate daily caregiving situations – a concept encapsulated by Koops (Reference KOOPS2019) as Parenting Musically. Music is used, for example, to capture attention (Evans et al., Reference EVANS, DEAN and BYETT2022), soothe and calm (Corbeil et al., Reference CORBEIL, TREHUB and PERETZ2016), support routines (Young & Gillen, Reference YOUNG, GILLEN, Gillen and Cameron2010), or simply share a lullaby (Bainbridge et al., Reference BAINBRIDGE, BERTOLO, YOUNGERS, ATWOOD, YURDUM, SIMSON, LOPEZ, FENG, MARTIN and MEHR2021). Alongside these functions, scholars have also examined the contexts in which MI arises: changing nappies (Addessi, Reference ADDESSI2009), managing distress (Hallam, Reference HALLAM2015), car journeys (Koops, Reference KOOPS2014), bedtime (Sole, Reference SOLE2014), play (Custodero et al., Reference CUSTODERO, BRITTO and XIN2002), and emotional co-regulation (Lerma-Arregocés & Pérez-Moreno, Reference LERMA-ARREGOCÉS and PÉREZ-MORENO2022; Young & Gillen, Reference YOUNG, GILLEN, Gillen and Cameron2010). While this body of research has focused primarily on the adults’ intentions, emerging perspectives emphasise the child’s active participation and responsiveness within these contexts (e.g., Español et al., Reference ESPAÑOL, SHIFRES, MARTÍNEZ, PÉREZ, Español, Martínez and Rodríguez2022; Pitt & Welch, Reference PITT, WELCH, Barrett and Welch2023).

Notably, much of this work centres on mother–infant dyads, highlighting how maternal vocal expressions support bonding, calm, and emotional regulation (Corbeil et al., Reference CORBEIL, TREHUB and PERETZ2016; Hallam, Reference HALLAM2015). From a sociocultural perspective, the significance of maternal singing and traditional repertoire has been explored through studies of lullabies and early enculturation processes (Campbell, Reference CAMPBELL1996; Trehub & Trainor, Reference TREHUB and TRAINOR1998). Infants are sensitive to musical structure from early on (Trehub & Gudmundsdottir, Reference TREHUB, GUDMUNDSDOTTIR, Welch, Howard and Nix2015), responding to different vocal styles with rhythmic or tonal babbling (Stadler Elmer, Reference STADLER ELMER2012), and gradually engaging in proto-musical dialogues that reflect turn-taking responses (Provenzi et al., Reference PROVENZI, SCOTTO DI MINICO, GIUSTI, GUIDA and MÜLLER2018).

Methodologically, most of these studies rely on adult perceptions and self-reports (e.g., Blackburn, Reference BLACKBURN2017; Lamont, Reference LAMONT2008). Some have incorporated observational approaches – such as short home visits – to capture MIs in situ (e.g., Young & Gillen, Reference YOUNG, GILLEN, Gillen and Cameron2010). These perspectives have been crucial for establishing foundational knowledge about family MI, especially in non-formal learning environments. However, this methodological approach also possesses limitations. Parents’ perspective when studying a communicative phenomenon that is shared, bidirectional, and reciprocal (Español et al., Reference ESPAÑOL, SHIFRES, MARTÍNEZ, PÉREZ, Español, Martínez and Rodríguez2022; Provenzi et al., Reference PROVENZI, SCOTTO DI MINICO, GIUSTI, GUIDA and MÜLLER2018) could benefit from including long, regular, and in-context observations of the MI.

The main goal of this research was to identify the characteristics of parent–child participation in everyday musical and communicative interactions that primarily involve vocal expression, in five families with at least one child aged between 6 and 36 months. This article responds to one of the specific goals: To contrast the data collected from vocal MI in authentic everyday scenarios with the perceptions of the parents in the families in which these musical encounters were studied.

Methodological design

This study follows an emergent qualitative design (e.g. Aguirre, Reference AGUIRRE1995) and adopts a multiple case study approach to explore everyday parent–child MIs through real-life family contexts. This method enables the identification of both shared and distinctive patterns across five families. As described by Chetty (Reference CHETTY1996), it is particularly suitable for addressing complex research questions and examining under-theorised phenomena from multiple perspectives, thus allowing for a comprehensive and context-sensitive analysis.

Participants

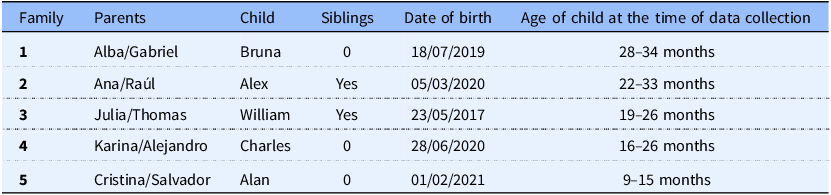

The participants (see Table 1) were five families that met the following selection criteria: the family nucleus included the mother, father and at least one child aged between 6 and 36 months; the children represented different developmental stages, and families resided in the same urban area (Barcelona, Spain). Musical background was not a selection criterion. However, in order to better understand the context of each family, parents were later asked about their musical and sociocultural backgrounds during interviews. These families were contacted through the researcher’s personal and professional references, in view of the characteristics of this study and the type of data collection instrument used (see section 2.2). The participants had to make a considerable commitment because each audio recording of a family day was supposed to be a total immersion in their everyday private lives.

Table 1. Participants

Information on each family’s social and musical background, as reported in the interviews, is included to contextualise the findings. These details enrich interpretation but were not used as inclusion criteria.

-

• Family 1 (F1): Both parents, university lecturers in early childhood education, value music as a natural, holistic language that plays a central role in family life and cultural transmission. Alba studied piano and solfeggio formally; Gabriel is self-taught in guitar and singing.

-

• Family 2 (F2): The mother holds a degree in psychology; the father completed secondary education. Ana learned how to play the guitar and theory until age 13; Raúl has no musical training. They use music to navigate challenging parenting moments and enrich daily routines.

-

• Family 3 (F3): The mother has a PhD in education and degrees in music didactics and musicology; the father studied art history and attended piano classes at a conservatory. They view music as a playful, child-led form of shared experience.

-

• Family 4 (F4): The mother is a dentist, and the father has a degree in political science, economics and finance. Karina learnt to play percussion instruments at school, and Alejandro had some piano and flute classes when he was a child. They describe music as a way of transmitting calm and a sense of well-being to their child.

-

• Family 5 (F5): The mother holds a degree in music education and works as a primary school music teacher. The father completed secondary school and took some piano lessons. They view music as an essential family resource with proven benefits.

Data collection instruments

Audio recorder

The primary data collection tool was a DLP (Digital Language Processor) audio recorder associated with LENA® software – a small, portable device that fits in a child’s coat pocket and records sound for up to sixteen hours (see Pérez-Moreno et al., Reference PÉREZ-MORENO, LERMA-ARREGOCÉS and DOSAIGUAS2025 for further information on the DLP).

This research focuses on vocal interactions due to one peculiarity of this instrument: it only records sound, and thus, the only characteristic that can be attributed to the participants is their voice. No other recorded sound – such as a musical instrument, body percussion, or recorded music – can be assigned to any participant unless it is accompanied by unequivocal speech. While this aspect restricts some types of data, the DLP’s benefits outweigh the limitations: it allows for long recordings, is easy for families to operate, captures children’s immediate sound environment, and is minimally intrusive.

Each family completed monthly weekend recordings over nine months. Six recordings were collected per family, except for Family 4, which completed five.

Interview

All the families completed a semi-structured interview consisting of 15 open-ended questions, which had been designed and validated in prior phases of this research (see Lerma-Arregocés & Pérez-Moreno, Reference LERMA-ARREGOCÉS and PÉREZ-MORENO2023). The interviews aimed to explore parents’ perceptions of parenting and music, as well as the relationship between these two aspects in their family life, the importance of music education in their homes, the way they shared music with their children on an everyday basis, the types of activities they used the most to interact musically, the characteristics of the vocal MI with their children – primarily singing – and the emotional content of these sung interactions, among other matters.

Ethical considerations

The study followed the ethical guidelines of the host institution. Informed consent was obtained from all participating adults for both audio recordings and interviews. Verbal assent procedures were followed with the children, adapted to their age and level of comprehension. Families were fully informed about the study’s purpose, procedures, and the use of the data for scientific purposes. Participation was entirely voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time. The ethical implications of the methodological approach, including the use of LENA®, are discussed in detail in Pérez-Moreno et al., Reference PÉREZ-MORENO, LERMA-ARREGOCÉS and DOSAIGUAS2025.

Data analysis

Two procedures were completed simultaneously: examination of the audio recordings and the interviews.

-

(1) Recordings

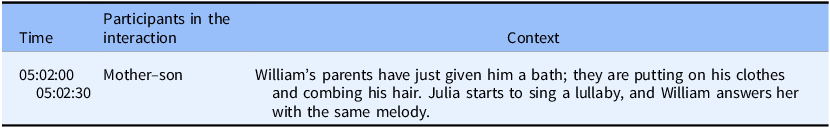

Firstly, we listen to each one of them (around 420 hours in total) in their entirety. Episodes that featured participation and MI through the voice were identified. MI between the participants was considered if at least one of them employed a vocal discourse that articulated tonal, melodic, and/or rhythmic patterns (Cross & Morely, Reference CROSS, MORLEY, Malloch and Trevarthen2009) to create organised sound (Blacking, Reference BLACKING2006), even if the other party’s vocal discourse was more associated with the communicative expressions of language and the emotions. A spreadsheet with an indexing table was used to log this phenomenon (see Table 2). The timeline of the events in each recording was noted every 30 seconds, and annotations were made indicating the participants and the context.

Table 2. Part of the indexing table

Following the identification process, each episode (a total of 195 across all recordings) was analysed using the MICAD – Musical Interaction among Children and Adult Descriptors – (see Lerma-Arregocés & Pérez-Moreno, Reference LERMA-ARREGOCÉS and PÉREZ-MORENO2023), specially designed and validated for this study. It was developed from a comprehensive literature review and refined through interaction with the data. The instrument comprises three blocks:

-

- Block 1: identification (coding) and duration of each vocal MI episode.

-

- Block 2: contextual information (e.g., adult participant, order of participation, setting, situation, probable function).

-

- Block 3: musical and communicative features (e.g., type of vocal expression, type of interaction, repertoire, emotional expressions).

This process allowed for both horizontal analysis (in-depth qualitative exploration of each episode) and vertical analysis (global quantification across all recordings).

-

(2) Interviews

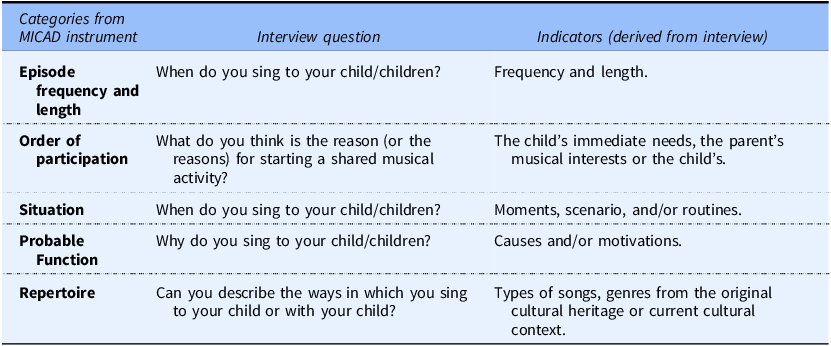

The interview transcripts were analysed using a directed content analysis approach (Hernández -Sampieri et al., Reference HERNÁNDEZ-SAMPIERI, FERNÁNDEZ and BAPTISTA2014). Coding was guided by the categories defined in the MICAD, allowing for systematic alignment between parental discourse and observed data. For instance, responses to the question ‘When do you sing to your child/children?’ were associated with the ‘situation’ category (e.g., play time, meals), and answers such as ‘often’, ‘a lot’ or ‘all the time’ were linked to ‘episodes frequency and length’. Table 3 illustrates how selected interview questions corresponded to specific categories from the MICAD instrument.

Table 3. Relationships between interview content and the categories from the analysis instrument

Discussion of results

The results for the categories shown in Table 3 are presented in this section. Quantitative data (or vertical analysis) from the recordings are discussed in dialogue with parents’ interview responses and theoretical frameworks to enable a more comprehensive interpretation and triangulation of the data.

While each category is addressed individually for analytical clarity, they remain deeply interconnected, reflecting the holistic nature of everyday vocal MI between parents and children. Presenting discussion and data together supports a more integrated approach suited to the multidimensionality of the phenomenon.

Episode frequency and length

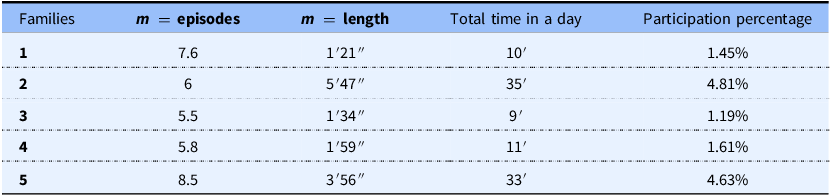

To understand the families’ level of engagement in vocal MI, we examined the average number and duration of episodes over 5-6 days of continuous audio recordings per family. We also calculated the percentage of daily recorded time (12-16 hours of recorded time) devoted to vocal MI. Table 4 summarises the results:

Table 4. Frequency of families’ participation in MI

Parents were asked: ‘When do you sing to your child/children? [how often and for how long?]’. Their responses reflect frequent and informal use of singing:

-

- ‘I sing a lot, with her or without her, not necessarily because Bruna wants me to but because I feel like it. That’s how much we sing every day’ (father, F1).

-

- ‘I sing to them a lot, but for no reason in particular, there’s no set time, although it’s almost always at lunchtime and at bedtime’ (mother, F2).

-

- ‘Generally, I sing as a way of starting a game with Charles’ (father, F4).

-

- ‘At home we sing all the time […] and I almost always use singing as part of a routine’ (mother, F5).

Although parental reports often describe singing as frequent and music as an ever-present element in family life – supporting previous findings (e.g., Custodero & Johnson-Green Reference CUSTODERO and JOHNSON-GREEN2003; de Vries, Reference DE VRIES2009; Evans et al., Reference EVANS, DEAN and BYETT2022; Koops, Reference KOOPS2019) – the recorded data revealed a comparatively brief duration of vocal MI, ranging from 1.45% to 4.63% of the day (M=2,74%, ≈ 16 minutes). This divergence underscores the importance of complementing self-reported data with more naturalistic observation: while interviews shed light on the symbolic and emotional meanings that parents attribute to music, recordings reveal how musical expression emerges in brief yet recurrent forms across the day (this will be explored in the following sections).

Despite their brevity, these MI cannot be dismissed as insignificant. Prior analyses (Lerma-Arregocés, Reference LERMA-ARREGOCÉS2023) show that even short episodes may display rich musical and communicative features – such as anticipation, imitation, synchrony, variation, or melodic and rhythmic development – supporting theoretical perspectives that parents displayed vocal styles depending on the context (e.g., slow and soft for calming, rhythmic and playful for games, Young, Reference YOUNG2023) while infants, in turn, are sensitive to these musical styles, responding with rhythmic or tonal babbling, contour-matching vocalisations, or even initiating turn-taking sequences that resemble proto-duets (Español et al., Reference ESPAÑOL, SHIFRES, MARTÍNEZ, PÉREZ, Español, Martínez and Rodríguez2022; Stadler Elmer, Reference STADLER ELMER2012; Trehub & Gudmundsdottir, Reference TREHUB, GUDMUNDSDOTTIR, Welch, Howard and Nix2015). Thus, short episodes still reveal meaningful musical engagement grounded in expressive exchange.

Order of participation

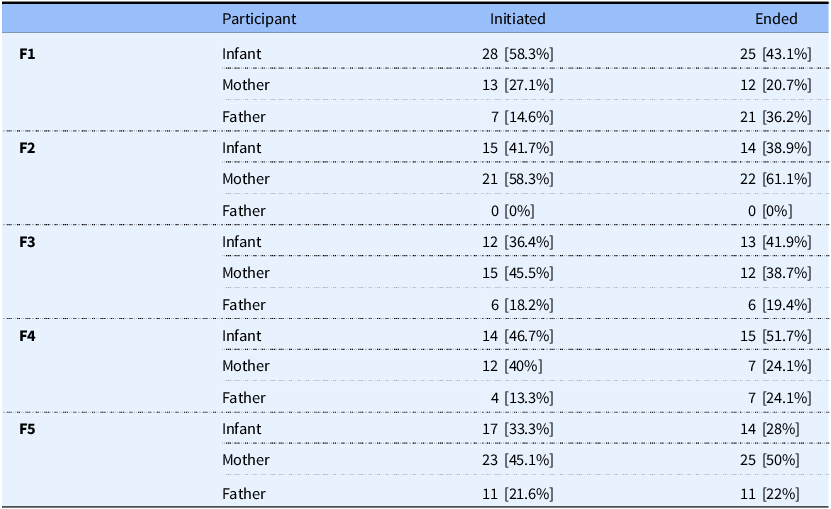

To examine patterns of participation, we reviewed the 195 episodes to identify who initiated and/or ended each interaction. Table 5 presents both frequency and the percentage distribution of these roles across participants in each family.

Table 5. Number of times and percentage in which participants initiated and/or ended the MI

Overall, children initiated 43.4% and ended 39.7% of the interactions; mothers initiated 42.4% and ended 38.2%; fathers contributed less frequently (14.1% initiations and 22.1% endings). These data show that mothers and children were more actively engaged in initiating and sustaining MI.

There was often a correlation between who initiated and who ended the interaction. This may be due to: (a) musical closure that naturally concluded the interaction; or (b) a loss of interest by one or both participants.

Parents were asked, ‘What do you think is the reason (or reasons) for starting a shared musical activity?’ Their responses reflect both child- and adult-driven motivations:

-

- ‘I think that it emerges from Bruna’s interest or an everyday scenario. For example, a fly comes into the house, and she notices it, so we start singing about the fly’ (mother, F1).

-

- ‘Sometimes to calm them down a little but also because they really like music and they ask me for songs’ (mother, F2).

-

- ‘As far as I’m concerned, let them begin the activity, it’s rarely me who takes the initiative. The fact is I’m more open to being invited to make music’ (mother, F3).

-

- ‘Generally, because I want to get something done, get Charles off to sleep, get him to relax, or when we want to have fun’ (mother, F4).

-

- ‘In this case, after I got pregnant, I sang a lot and played the piano all the time, music is something I really live for’. (mother, F5).

In some cases, perceptions and recorded behaviour aligned – e.g., in F1 and F2, both mothers mentioned their children’s interest or their own motivation, which matched the data. In F3, the mother claimed she ‘rarely’ initiated MI, yet she led most often (45.5%). In F4, the mother said she initiated to regulate her son, but the child led slightly more (child: 46.7%, mother: 40%). In F5, alignment was again observed, as the mother expressed strong musical motivation and was the main initiator (45.1%).

The data suggest that MIs are often co-constructed, with both adults and children taking turns in initiating and concluding the exchanges. This points to a dynamic in which musical engagement is not solely driven by adult caregiving goals, but also by children’s own communicative and expressive initiatives. These early signs of mutual responsiveness support the view of MI as a reciprocal practice (e.g., Provenzi et al., Reference PROVENZI, SCOTTO DI MINICO, GIUSTI, GUIDA and MÜLLER2018). In this light, we propose the term Family Musicality (Lerma-Arregocés, Reference LERMA-ARREGOCÉS2023) to refer to the shared musical agency of both children and caregivers, laying the groundwork for deeper exploration in the sections that follow.

Situation

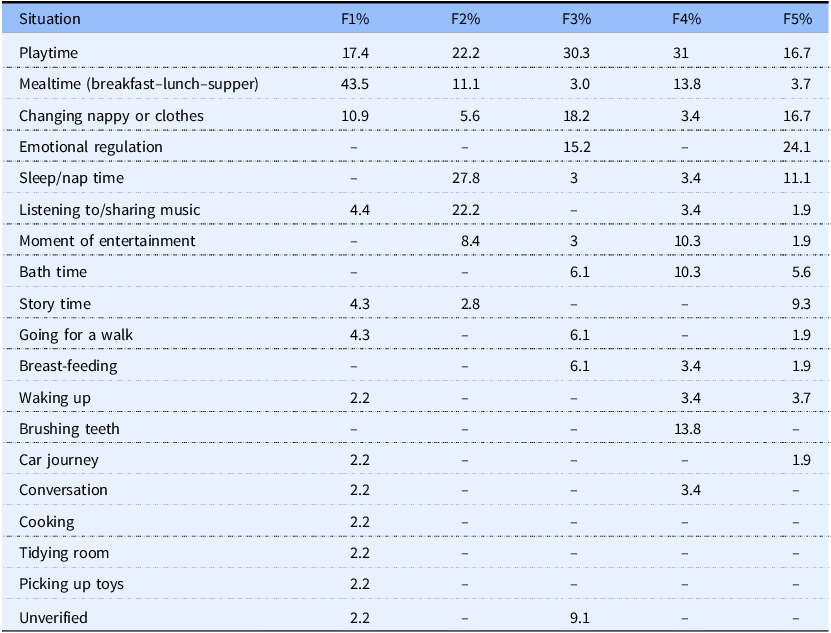

The everyday scenarios in which MI occurred have been categorised for each family. Table 6 presents them in order of the most to the least common detected.

Table 6. Percentage of vocal MI by scenario and family

Note: [–] indicates no vocal MI episodes in that scenario.

Parents’ responses to ‘When do you sing to your child?’ generally aligned with the most frequent recorded scenarios. For example:

-

- F1’s mother mentioned mealtimes – ‘When we’re about to eat’. Recordings confirmed that 43.5% of MI occurred during meals.

-

- F2’s mother cited bedtime – ‘Singing is kind of sacred at nap time and at nighttime’, which aligned with 27.8% of MI occurring at that time.

-

- F4’s mother mentioned brushing teeth as a moment to sing – ‘I sing to him a lot. I like doing it when I am changing his nappy in the morning, when I pick him up, and sometimes I make up songs to brush his teeth’. Even though it wasn’t the most frequent scenario, MI occurred 13.8% of the time in this situation.

-

- F5’s father referred to play – ‘We use singing for routines but also, especially, when we’re playing’, consistent with 16.7% percentage of MI during play.

However, some discrepancies appeared:

-

- F4’s mother identified nappy changing as a common situation where shared singing occurred; however, in the recordings, this scenario accounted for only 3.4% of the MI.

-

- F5’s father emphasised play, yet emotional regulation was more common in recordings (24.1%).

-

- F3’s parents described the presence of MI in emotional regulation scenarios – ‘Certainly, when they needed to be calmed down’ (father, F3); ‘When we spend time together […] at mealtimes, at bath time’ (mother, F3) – yet play (30.3%) and changing clothes (18.2%) were the most frequent contexts.

These contrasts suggest that while parents can recall salient musical episodes, recordings reveal a broader and often unnoticed range of situations in which vocal MI naturally arises. This supports the notion of MI as dynamic, culturally shaped, and intuitively enacted practices (Young, Reference YOUNG2018).

From theoretical perspective, everyday musical exchanges – whether during play, mealtime, or routine care – exemplify what Koops (Reference KOOPS2019) calls Parenting musically: using music to structure caregiving tasks. These findings reinforce that MI is not limited to designated “musical moments” but permeates spontaneous, embodied family life. As Addessi (Reference ADDESSI2009) argues, daily routines offer cyclic, predictable frameworks that foster musical communication. Our data extend these insights, revealing scenarios such as ‘bath time’, ‘story time’, ‘waking up’ or ‘tidying’ that parents often overlook, yet emerged as musically rich.

In sum, vocal MI emerges across a broad range of relational and routine contexts, not as isolated events but as embedded forms of early communication. These findings align with research framing MI as innate, flexible, and culturally grounded practice (Malloch &Trevarthen, Reference MALLOCH and TREVARTHEN2009; Pitt & Welch, Reference PITT, WELCH, Barrett and Welch2023) and highlight the importance of everyday situations not just as background settings, but as structuring elements in how MI unfolds within family life.

Probable function

This finding offers relevant information on how music favours different aspects of the parent-child relationship. When the scenario is played, the most probable function would be to accompany the game and/or entertain, if it affects the child’s emotional regulation: soothing; if it is sleeping time: to get the child to sleep and/or calm him or her down. If the scenario concerns changing nappies/clothes, the probable function would be to get the child’s attention or entertain; if it is about waking up the infant, the function would be greeting. Figure 1 shows, in percentages, the number of times that the categorised functions were identified.

Figure 1. Probable function of MI.

Regarding question – Why do you sing to your child? The answers were:

-

- ‘When she was younger, it was mostly associated with some routine, though not so much now that she is older. But for example, when she must wash her hands, then it’s a way of telling her we’re going to eat’ (mother, F1).

-

- ‘Music helps me draw him into times of relaxation and sleep. For me it is very important because I use it as a tool to get him to relax and fall asleep’ (mother, F2).

-

- ‘[…] we used to sing a lot to amuse William, in the shower for example, which was a horrible moment for him’ (mother, F3).

-

- ‘I invent songs to make him laugh or get his attention’ (mother, F4).

-

- ‘We sing all the time at home, in the shower, when we’re going to sleep or waking up, while we play’ (mother, F5).

Parents’ perceptions show they were aware of the purpose of singing in their homes. However, results also show that parents found more uses for vocal expression than they reported. Quantitative results show that the most frequent function was entertainment, which occurred in all the participating families, representing 48.7% of the total, followed by play accompaniment, 19.5% of the total. Interestingly, F5 was the only case where soothing (27%) surpassed play accompaniment (13%), possibly due to the child’s age (9–15 months), when MI often supports emotional regulation and bonding (e.g., Bainbridge et al., Reference BAINBRIDGE, BERTOLO, YOUNGERS, ATWOOD, YURDUM, SIMSON, LOPEZ, FENG, MARTIN and MEHR2021; Young & Gillen, Reference YOUNG, GILLEN, Gillen and Cameron2010).

These findings suggest that MI serves multiple overlapping functions, not only to manage routines (as explained in the situation category) but also to nurture affective connection and shared attention. Vocal MI is better understood as a relational and communicative practice shaped by mutual or bidirectional responsiveness, where children are not passive recipients but active participants in musical meaning-making and affective exchange (Español et al., Reference ESPAÑOL, SHIFRES, MARTÍNEZ, PÉREZ, Español, Martínez and Rodríguez2022; Pitt & Welch, Reference PITT, WELCH, Barrett and Welch2023).

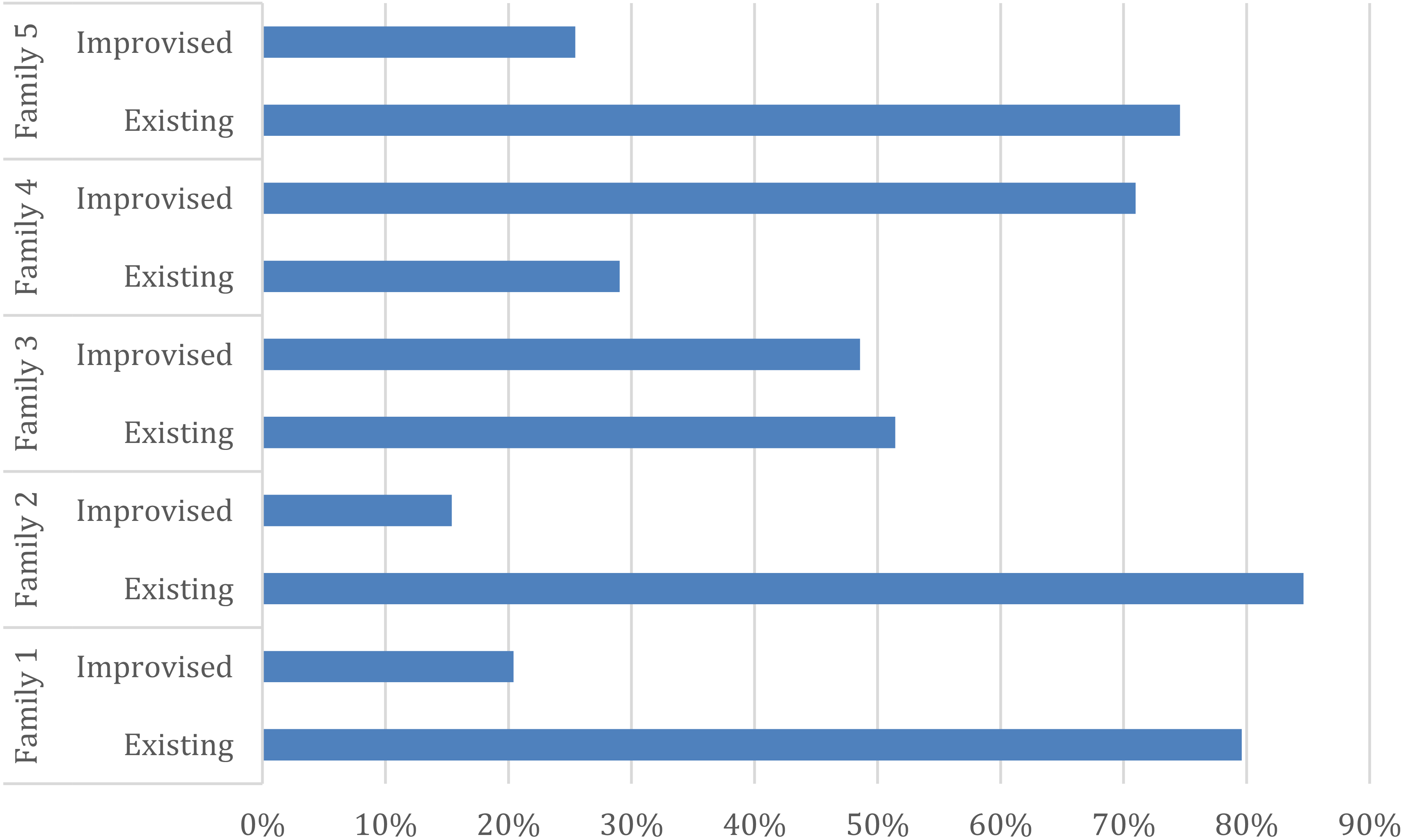

Repertoire

This section explores the type of repertoire used during vocal MI episodes, distinguishing between existing and improvised forms, based on observable musical traits in the recordings. A repertoire was classified as existing when recognisable songs or melodies could be identified, and as improvised when the vocal material appeared spontaneous, intuitively generated, or created in-the-moment through melodic or rhythmic invention. Figure 2 shows the distribution of these two categories across families.

Figure 2. Percentages of types of repertoire.

When asking about the repertoire they used, some answers were:

-

- ‘The entire traditional Catalan repertoire for children, also all sorts of music that she (Bruna) has picked up and so she asks for it. Especially music with lyrics, music by the groups El mic and Pot petit, by Jorge Drexler, and “Let it be” by the Beatles’ (father, F1).

-

- ‘We sing anything: Iron Maiden, Jurassic Park, Pot petit. They like a bit of musical variety, not just children’s music […] and also songs that my mother and my grandparents sang to me’ (mother, F2).

-

- ‘I’m really bad at song lyrics, I don’t remember any of them, so I improvise as much as possible, it’s more like playing a game’. (father, F3).

-

- ‘I sing him pop songs that I like, and I change the lyrics intuitively […] the music I sing doesn’t necessarily have to be something I learnt but something that all of a sudden becomes spontaneous’ (mother, F4).

-

- ‘Basically, the songs I learnt during my musical training, the typical ones from the traditional children’s repertoire in Catalan’ (mother, F5).

Parents reported using a broad repertoire with identifiable songs – including traditional children’s music, popular tunes, and personally meaningful pieces – which falls within what we classified as existing repertoire. Recordings confirmed that this type of material dominated overall (67.1%), particularly in F1, F2, and F5 (79.6%, 84.6%, and 74.6%, respectively). This supports earlier findings that parents transmit cultural aspects of their society through the repertoire they share with their children (e.g., Campbell, Reference CAMPBELL1996; Trehub & Trainor, Reference TREHUB and TRAINOR1998).

However, while improvisation was rarely mentioned by parents, it emerged in all families’ recordings. Notably, in F4, 71% of vocal MI episodes were improvised, in line with the mother’s description of intuitive and spontaneous singing. In contrast, F3 showed a more balanced distribution, although the father emphasised improvisation more than the recordings suggested.

This discrepancy points out how improvised vocalisations – often playful, situational, and relational – may go unrecognised by adults as meaningful musical acts. Yet, they reflect a key dimension of early MI: responsiveness. As Español et al. (Reference ESPAÑOL, SHIFRES, MARTÍNEZ, PÉREZ, Español, Martínez and Rodríguez2022) argue, children are not passive recipients but ‘skilled participants’ in musical exchanges, actively shaping the communicative process. Thus, MI repertoire should not be seen solely as content to transmit, but as a flexible, co-constructed medium shaped by interactional demands.

Conclusions

This study offers a detailed comparison between parents’ accounts and the actual occurrence of vocal MI in daily family life. While participants described singing as frequent and meaningful, the recordings revealed that vocal MI occurred in short but recurring episodes. These findings underscore the value of combining interviews with context-sensitive observation to better understand how music emerges in spontaneous and relational ways.

Across all categories, discrepancies were observed: MI appeared in more varied situations than parents recalled, served multiple overlapping functions beyond routine regulation, and included a greater degree of improvisation than was verbally acknowledged. Moreover, children often initiated or sustained these interactions, suggesting that MI is not solely an adult-directed strategy, but rather a dynamic and co-constructed communicative practice.

These insights point to the need to consider both adult and child contributions in early musical exchanges. Vocal MI functions not only as a caregiving tool but also as a site for affective connection, shared agency, and musical creativity.

Limitations and future directions

This study focused exclusively on vocal interactions, leaving out instrumental or gestural forms of musicality. It is important to mention that while parents in the interviews had the whole perspective, the data set for each family consisted of just six recordings.

Another limitation is the small and demographically homogeneous sample – composed of highly educated families. While systematic frameworks (e.g., MICAD analysis instrument) and triangulation helped reduce interpretative bias, the analysis remains subjective in nature. Additionally, children’s perspectives were accessed only indirectly through their vocal responses. Future research should aim to include more diverse family profiles and explore ways to integrate children’s voices more explicitly into both design and interpretation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the families that made this study possible.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research.