Nominating conventions are week-long events held in a different location every four years to select a party’s presidential general election nominee and conduct official party business. In recent elections, the cities chosen by the two parties to host their convention have been expected to raise approximately $75 million to cover convention costs incurred by the party and the city associated with the event (Garrett and Reese Reference Garrett and Reese2016). Many prospective host cities agree to these terms because conventions generate considerable publicity and signal the city’s ability to manage other large-scale conventions. Much of the convention fundraising is conducted by city-created host committees whose official purpose is to promote the city, not the party or its candidate. In the past, donors were a combination of national organizations seeking access to politicians rather than to support a specific party or candidate, partisan individual donors, and local donors boosting the marketing of their city (Heberlig, Leland, and Swindell Reference Heberlig, Leland and Swindell2017). Our evidence reveals that access-oriented donors have a less prominent role in funding conventions because host committees have become more reliant on partisan and local donors.

Our evidence reveals that access-oriented donors play a less prominent role in funding conventions because host committees have become more reliant on partisan and local donors.

Cities are allowed to raise and spend funds through several mechanisms, but the host-committee fund and a security grant from the federal government are the primary funding sources (Heberlig, Leland, and Swindell Reference Heberlig, Leland and Swindell2017). Most campaign-finance regulations are justified on the premise that donors should not be capable of bribing candidates. Host committees are not candidates; therefore, their fundraising is not subject to the same restrictions imposed on campaigns about who can donate or how much they can donate. Host committees typically are organized as 501c3 charities or 501c6 business leagues; thus, contributions to them often are tax-deductible. Contributions to a host committee do not have to be reported publicly until after the convention, making it impossible for citizens and the media to track who is trying to gain the attention of lawmakers with their sponsorship of convention activities.

The financing of these events is considered by reform advocates to be a major loophole in the campaign-finance system (Holman, Canterbury, and Bridges-Curry Reference Holman, Canterbury and Bridges-Curry2008; Weissman Reference Weissman2008) because donors could gain the attention of a presidential candidate with unlimited contributions to the host committee. Many host-committee donors are “access-oriented” (Heberlig, Leland, and Swindell Reference Heberlig, Leland and Swindell2017) because nominating conventions are “a political party’s single largest public gathering of local, state, and federal elected officials and party leaders” (Noble and Fischer Reference Noble and Fischer2016, 5). Moreover, donor packages include opportunities to attend receptions and seminars with convention attendees. Noble and Fischer (Reference Noble and Fischer2016, 17) pointed out that, traditionally, the “biggest convention sponsors are those with companies pressing issues before the federal government.” The nature of these events has led some watchdog organizations to be concerned about the outsized influence these donors may obtain by contributing to the conventions. These concerns continued to increase in 2014 when Congress further deregulated the rules regulating nominating convention fundraising, which ended public financing of nominating conventions and allowed political parties to raise private donations with higher caps to offset convention costs.

However, this change in the rules about nominating convention funding occurred when the US Supreme Court also was removing other regulations regarding corporate and union fundraising and spending in Citizens United v. FEC (2010). Corporations and wealthy donors now have more opportunities to spend large sums of money in ways that might directly impact competitive presidential and congressional elections. The advent of independent expenditure-only PACs (i.e., “Super PACs”) may mean that corporations and individuals have less incentive to contribute to nominating convention funds than they had before the 2014 rules change because they can spend unlimited sums directly promoting a candidate.

Additionally, the rise of Donald Trump fueled increasing political polarization. Several corporate donors who traditionally had contributed to host committees of both conventions ceased to contribute to either to avoid alienating customers (Martin and Haberman Reference Martin and Haberman2016; Mider and Dexheimer Reference Mider and Dexheimer2016). This polarization limits the ability of host committees to attract traditional access donors and potentially limits the willingness of local donors to view nominating conventions as merely local boosterism rather than a partisan event. Local donors from the “out-party” are likely to be less willing to contribute in a polarized environment.

This study assessed changes in the amounts and sources of nominating convention fundraising. We cannot prove that any of these changes are attributable solely to changes in the law or in the broader political culture. However, we can clarify what has changed and which rationales for change seem to be the most convincing. This study shows that polarization has influenced the behavior of donors but that changes in the law likely have changed the way that host committees solicit funds.

This study assesses changes in the amounts and sources of nominating convention fundraising.

THE EVOLUTION OF FINANCING NATIONAL NOMINATING CONVENTIONS

The Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) amendments of 1976 prohibited parties from receiving private donations to pay for nominating conventions. Instead, Congress established a public convention fund. This was one of several campaign-finance subsidies paid for through voluntary income-tax checkoffs (Federal Election Commission n.d.). Initially, the major political parties received $4 million; the rate was indexed for inflation, reaching $18.2 million by 2012. The parties were to use the presidential election campaign money to pay for “inside the hall” activities including arena renovations, operations, and planning (Garrett and Reese Reference Garrett and Reese2016). The host committees raised funds to cover facility rent, security and transportation services, and promotion of the city. The parties increasingly used the convention bid process to convince host committees to cover more expenses (Heberlig, Leland, and Swindell Reference Heberlig, Leland and Swindell2017).

In April 2014, President Barack Obama signed into law a Republican-sponsored measure that ended the use of public funds to pay for national nominating conventions and established fundraising limits on what political parties could raise from private citizens and PACs (Garrett and Reese Reference Garrett and Reese2016). The limits allowed individual citizens and PACs, respectively, to contribute $33,400 and $15,000 annually to each party’s national nominating account.

On New Year’s Eve 2014, Congress passed an omnibus bill containing a provision that allowed political parties to raise an additional $102,000 from donors who were interested in contributing to a party’s convention account and several other new party accounts.Footnote 1 As a result of these new provisions and special accounts, “an individual will be able to contribute over half a million dollars directly to a party for its convention over the four years between each convention” (Noble and Fischer Reference Noble and Fischer2016, 17).

The 2014 law still does not allow parties to raise money from entities previously prohibited from contributing (e.g., corporations, banks, and labor unions), but it does enable individual donors and PACs to donate substantially larger amounts. However, corporations and unions are permitted to give unlimited sums to a host city’s convention committee. The political parties are permitted to receive free or discounted services or products from corporations and wealthy donors, which are considered in-kind contributions for the purpose of promoting the city or its commerce during a convention. In the two presidential election cycles between the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 and the US Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. FEC (2010) ruling, nominating conventions were among the least-regulated options for individual and corporate spending. As a result, by 2008, the proportion of funding for conventions by private donors and corporations had increased to 80% (Weissman Reference Weissman2008). Our review of Federal Election Commission (FEC) reports of convention fundraising by host committees revealed that, by 2020, more than 95% of the money was contributed by private donors, businesses, and corporations (Sebold, Heberlig, and Boatright Reference Sebold, Heberlig and Boatright2026). Given the emphasis in campaign-finance jurisprudence on limiting corruption, the persistent financial support of conventions by donors raises questions about the divergence of convention fundraising rules and patterns from campaign-finance laws governing other aspects of campaigns.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Neither the political parties nor the host-city nominating convention committees have limits on what they can spend for events; therefore, the 2014 convention finance rules likely will lead to more fundraising by both entities—but the changes may influence these two entities differently. Given the loosening of party contribution limits while host-committee rules have remained constant, we first ask whether fundraising is shifting from host cities to political parties. Political parties maintain existing donor lists and have an incentive to steer their donors to party convention accounts rather than to a host-city’s committee. Donors still may have tax incentives or other motives for giving to the host-city committees, but these committees do not necessarily comprise the loophole they were before 2014.

The second question is whether there has been a change in the geography of donors to host-city committees—specifically, whether they are raising fewer donations from local donors. We had mixed expectations on this point. On the one hand, given the increasing costs of hosting nominating conventions, it is possible that more donors to host committees are not located in the states that host the convention. Furthermore, in recent years, the host cities have differed in their capacity, composition, and goals. Most notably, the Democratic host cities in 2016 and 2024 were much larger than the Republican host cities. Therefore, it is likely that some cities have a greater opportunity to raise more local donations for their conventions whereas others may need to build a national fundraising network.

On the other hand, we might expect the proportion of local donors to increase beginning in 2016 because national political parties may be tapping out their major national donors for their convention accounts. This leaves host-city committees more reliant on local donors who give to support their hometown’s week in the national spotlight. We made this determination (and all of the subsequent questions) by examining the composition of the host-city committees’ donor pools over time—keeping in mind that 2020 was an odd year because convention plans were altered due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The third question is how partisan are donors to the host-city committees. Donors are supporting a political-party convention, so we expected them to be highly partisan in their contribution patterns. However, if donors contribute to support the host city, they may not be traditional party donors. Moreover, access donors often support both political parties and host committees of both cities. We assessed trends in the partisanship of the donors by examining the partisan mix of candidates financed by the host committee’s individual donors, whether donors gave to host committees for the same party in multiple election cycles, and whether donors gave to both party conventions.

FINDINGS

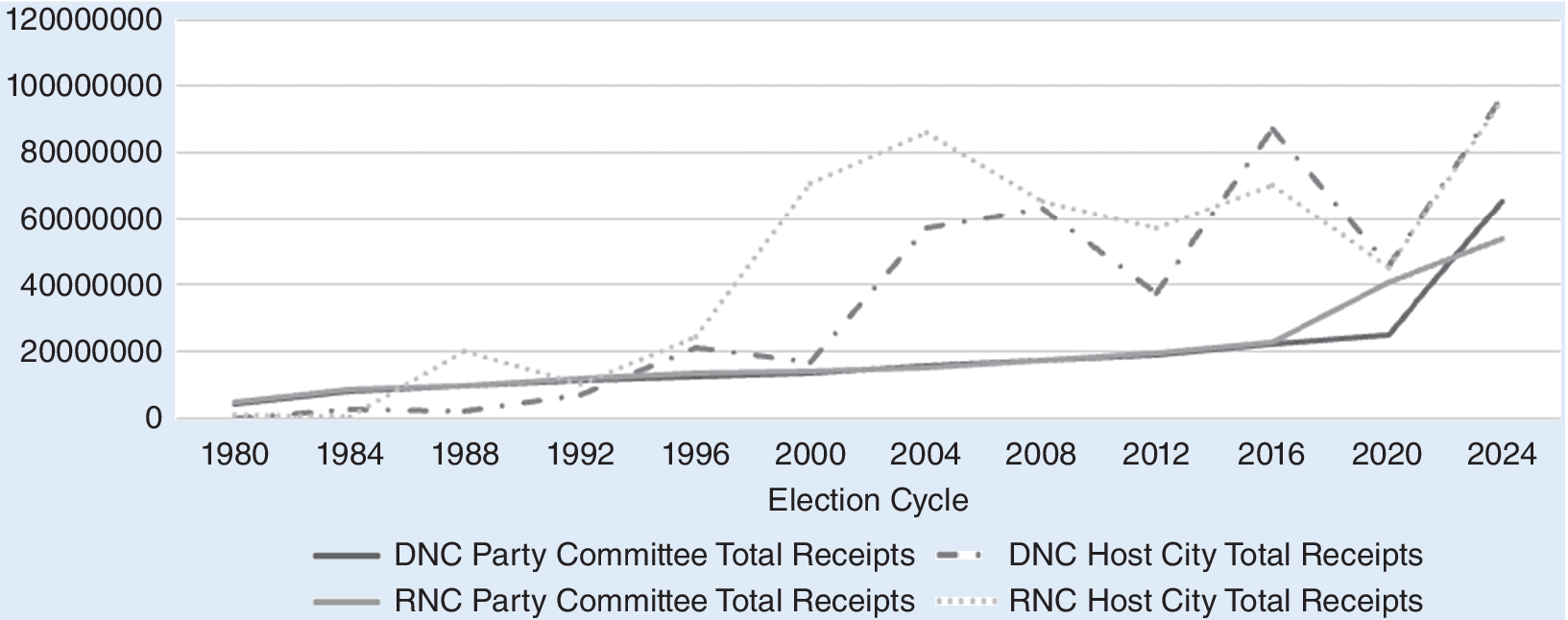

Figure 1 draws on financial reports to the FEC by host cities and political-party convention committees from 1980 to 2024. This period was selected because it succeeded the 1976 FECA Amendment banning political-party fundraising of private donations for nominating conventions. Beginning in 1980, private fundraising was replaced by a federal grant, and host cities were permitted to engage in supplemental fundraising efforts. The period also illustrates any changes in fundraising patterns after the law that provided convention grants for the political parties ended in 2014.

Figure 1 Nominating Convention Fundraising, 1980–2024

Source: Campaign Finance Data (Federal Election Commission n.d.-a)

Figure 1 shows that host-city fundraising was not affected by the increased involvement of parties in funding conventions. Fundraising by host cities grew exponentially by the 2000s, then tapered off in the 2012 election cycle. This was due, in part, because both host cities (i.e., Tampa and Charlotte) are smaller cities with limited histories of political giving and in part because President Obama banned corporate and lobbyist contributions to the Charlotte host-city committee (Heberlig, Leland, and Swindell Reference Heberlig, Leland and Swindell2017). Democratic host-city fundraising bounced back in 2016 and reported record-high fundraising in 2024. The Republican host city bounced back modestly in 2016 before tapering off in 2020. The waning fundraising by the host cities in 2020 was almost certainly a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the cancellation of in-person nominating convention activities.

The parties took advantage of their ability to accept large contributions to their new convention accounts following the 2014 reforms. In 2020, the Republican National Committee (RNC) raised almost double the amount of its previous convention revenues and continued its rapid increase in 2024. Democratic National Committee (DNC) fundraising remained relatively level in 2016 and 2020 but experienced a substantial boost in 2024. The fact that both political parties and the host committees raised substantial funds in 2024 suggests that each organization was able to recruit donors without “cannibalizing” each other’s donor pools. The next three figures use host-city committees’ FEC reports of their donors to assess changes in the donor pool from 2004 to 2024. Before 2004, FEC reports were not itemized by individual donors to host-city committees.

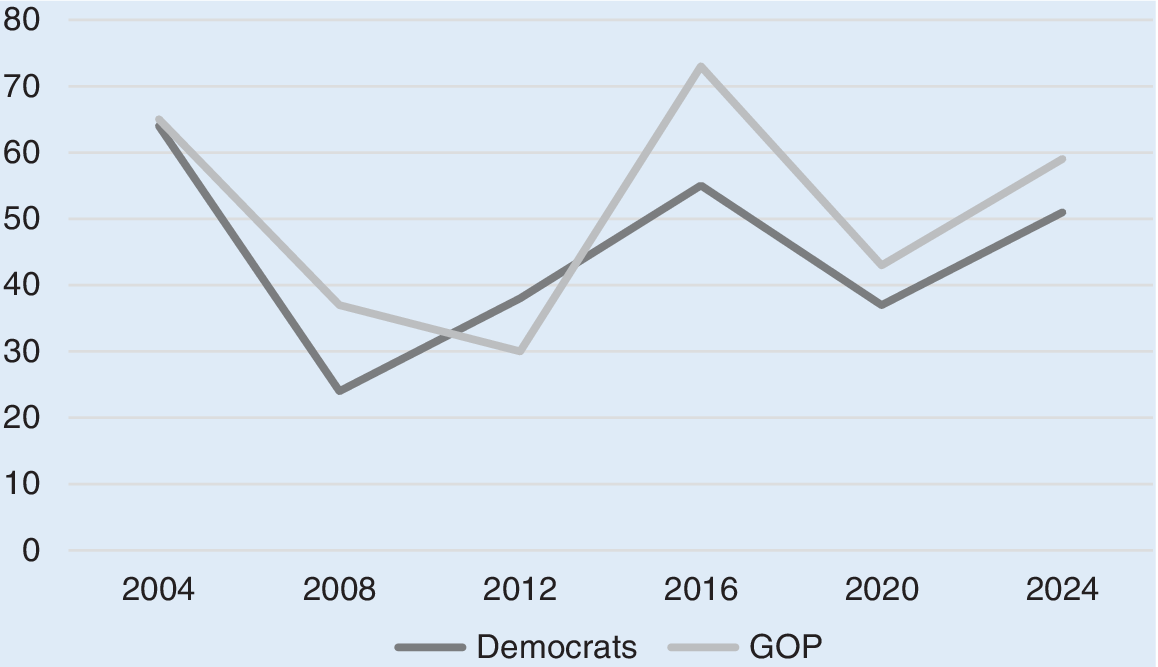

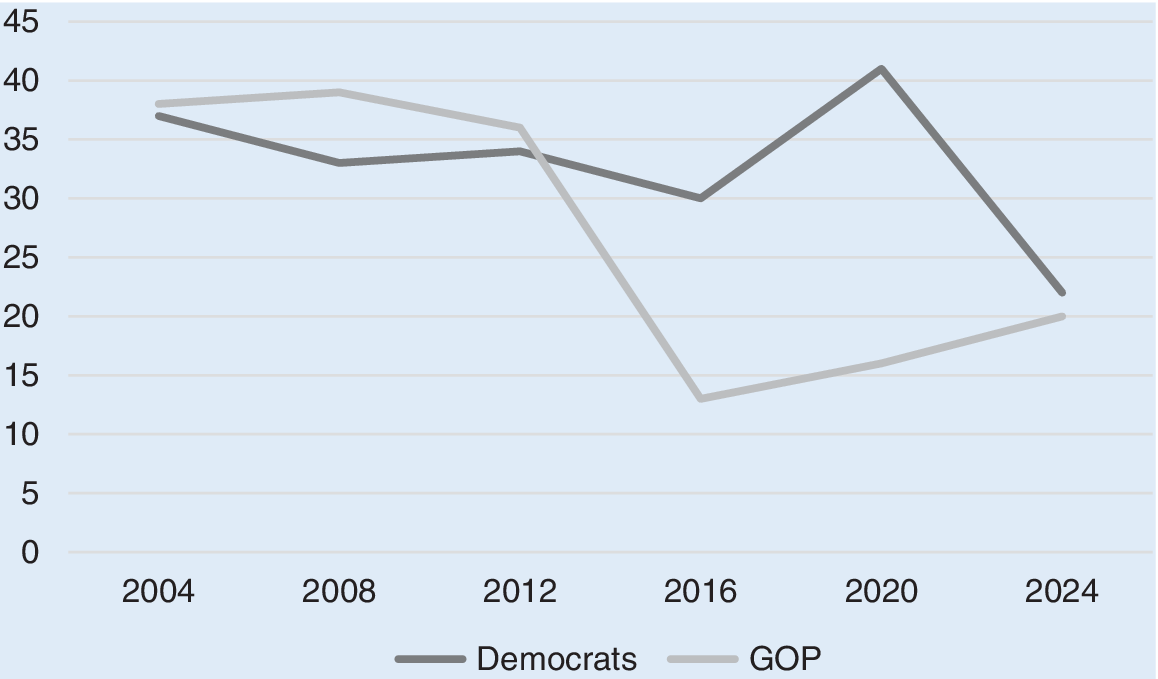

Figure 2 presents the proportion of local donors to host-city committees from 2004 to 2024. Donors were coded as local if they reported residing in the state hosting the convention. Figure 2 displays similar trends between the two parties. In 2004, both host cities—New York and Boston—raised more than 60% of their funds locally. When the conventions moved to smaller cities with less history of political giving (i.e., Denver, Saint Paul, Charlotte, and Tampa) in 2008 and 2012, the proportion of local donors decreased substantially, and the cities relied more on outside donors. By the 2020 election cycle, there was again a high proportion of local donors despite continuing to have smaller host cities (i.e., Charlotte and Milwaukee). In fact, Milwaukee’s proportion of funds from local donors was higher than Chicago’s in 2024—despite the $14.2 million from the Pritzker family for the Chicago DNC). Local money is consistently higher after the 2016 changes to the law, suggesting that political parties are continuing to press host cities for more money and that the parties are tapping the national donors for their convention accounts—or many traditional access donors have stopped giving to conventions in the Trump era—leaving host-city committees to rely more on local money due to a lack of alternatives.

Figure 2 Percentage of Local Donors to Host-City Committees, 2004–2024

Source: Campaign Finance Data (Federal Election Commission n.d.-a)

The similarity in the trend lines between the political parties suggests that the changes over time are not driven by the characteristics of the host cities. One reason why Republicans raise more from local donors than Democrats in most years may be that Democrats draw a significant percentage of their support from unions. That is, Democrats raised more than 10% of their funds from unions in all years except 2012 and they raised more than 20% of their funds from unions in 2020 and 2024.

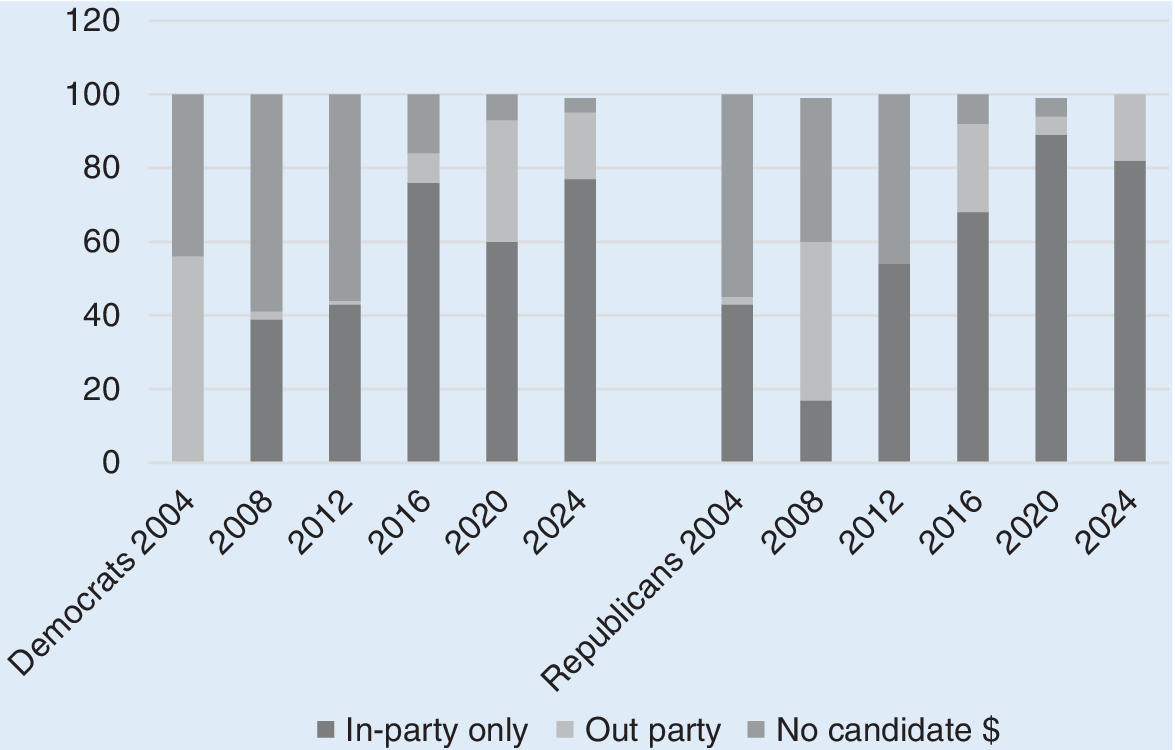

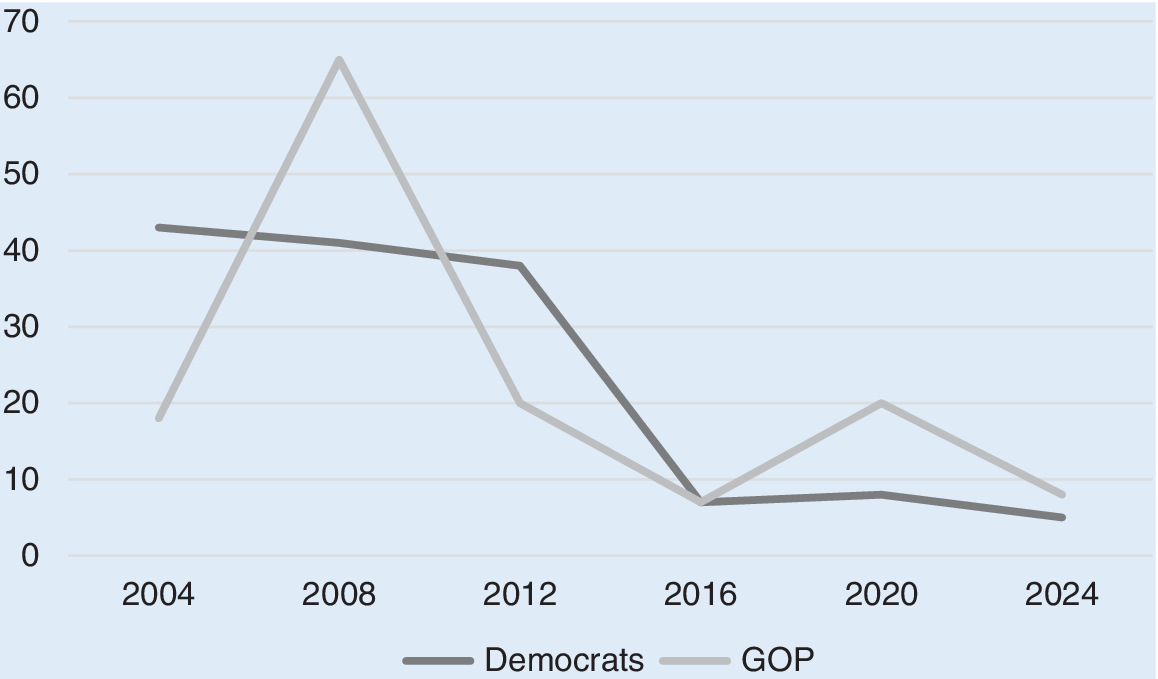

It is widely recognized that the American political system has become more polarized in recent decades and that negative partisanship has strengthened. Figure 3 measures the partisanship of each set of host-city committee donors—whether the donor gave only to candidates of the same party as the convention (i.e., in-party) in the previous election cycle; the donor gave to any candidates from the other party (i.e., out-party); or the donor did not give to candidates of either party. Figure 3 demonstrates that there has been an increase in the proportion of in-party donors to host-city committees for both parties. Most donors gave nothing to candidates of one party in the previous election cycle. That is, they are not giving even to local members of Congress of the opposing party for “business” or access reasons. In addition, host-city committee donors who also have not given to candidates have almost vanished. That is, over time, fewer apolitical donors have supported their city’s efforts to host a partisan event. This may be a demand-side effect—a function of a host-city committee’s decision to target partisan donors—or it may reflect the supply of donors and/or the greater proclivity of partisan donors to respond to solicitations from host-city committees. The significant shift in 2016 also suggests that this may be a result of the parties’ nominees.

Figure 3 Contributions to Candidates by Host-City Committee Donors, 2004–2024

Source: Campaign Finance Data (Federal Election Commission n.d.-a)

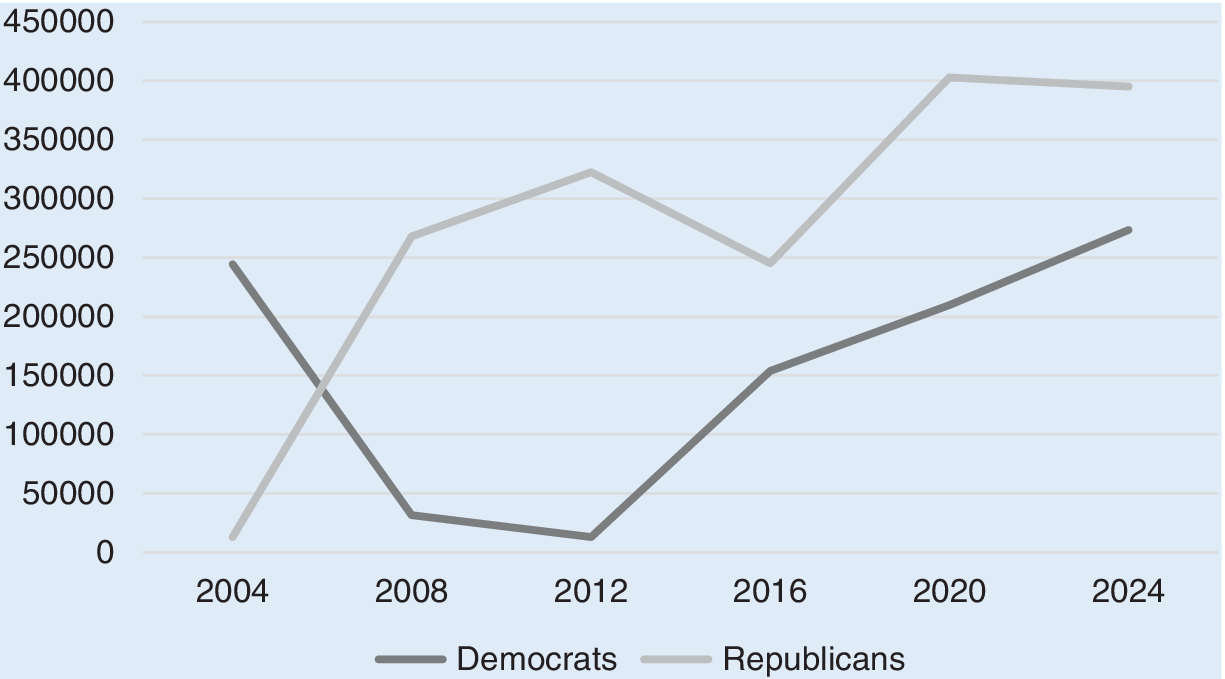

As donors have become more partisan, they simultaneously have given larger average sums, as illustrated in figure 4. Even with the opportunity to give uncapped sums to Super PACs and “dark-money” organizations, host-city committees have succeeded in attracting increasingly large donations. The number of individual donors to host-city committees is generally fewer than 100.Footnote 2 This indicates that host-city committees are not attracting a wide swath of donors and may rely heavily on their members, similar to other fundraising committees that often rely on their volunteers and committee members to raise most of the funds.

Figure 4 Mean Individual Donations to Host-City Committees, 2004–2024

Source: Campaign Finance Data (Federal Election Commission n.d.-a)

Figure 5 shows changes in the percentage of host-city committee funds received from repeat donors—that is, those who gave to a party’s host city in the previous election cycle. The figure shows that there has been a decline in the proportion of donors who gave to the host-city committee of the same party in a previous election cycle. Although they are giving to the same party’s convention in consecutive cycles, these donors are not necessarily giving for entirely partisan reasons. Their objectives may include access to party leaders or support for the system. From 2004 to 2012, there was a higher rate of repeat donors to host-city committees in subsequent elections—in some cases reaching 40% of the total. The proportion of same-party donors decreased by more than half for both parties in 2016 when Trump first became the GOP nominee. However, the proportion of repeat donors to GOP host-city committees increased in 2020 and 2024, suggesting that the GOP donor coalition has stabilized and regenerated. In 2024, the host-city committees were close to one another in the percentage of repeat donors, mainly because Chicago’s percentage of funds from repeat donors to Democrats decreased (even with substantial union and Pritzker money).Footnote 3 Without the spike in 2020, which likely was a function of the COVID pandemic (i.e., unions and other habitual donors giving early before the pandemic ended in the in-person activities and therefore a reason for casual contributors to donate), the trend for Democrats was down.

Figure 5 Repeat Donors to Host-City Committees, 2004–2024

Source: Campaign Finance Data (Federal Election Commission n.d.-a)

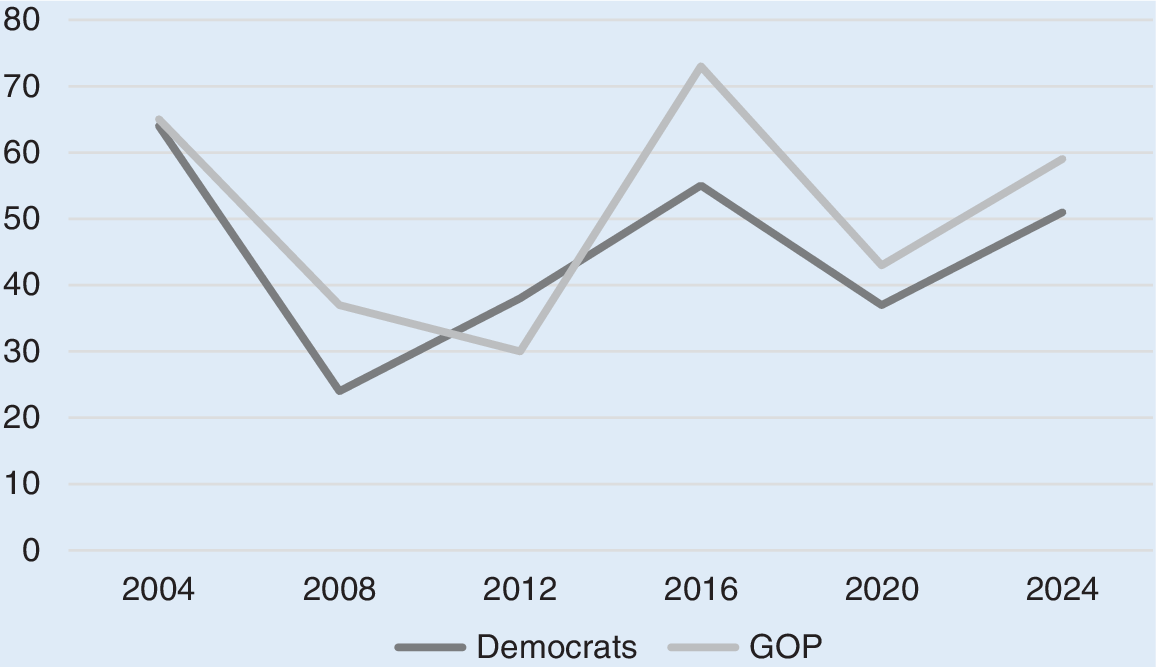

The increased partisanship of host-city committee fundraising also is shown in the decline in the proportion of donations from donors who gave to both host-city committees in the same election cycle from 2004 to 2024 (figure 6). Donating to both host-city committees typically is a sign of a desire for access to politicians because donors are not siding with a particular philosophy.

Figure 6 Donors to Both Host-City Committees, 2004–2024

Source: Campaign Finance Data (Federal Election Commission n.d.-a)

Figure 6 indicates similar patterns from previous findings on repeat donors (see figure 5), but the partisan deviations are more dramatic. In the election cycles from 2004 to 2012, the percentage of bipartisan donors to host-city committees was as high as 70% for donors to Republican host cities and 45% for Democratic host-city donors. By 2016, the rate decreased by more than 10 percentage points for both parties’ conventions and dropped even further from the Republicans’ 2008 peak. The rate increased only slightly for both parties in the 2020 election cycle, then fell again in 2024. Donors who traditionally sought access to public officials of both parties or who sought to appear bipartisan for their stakeholders or customer base are increasingly unwilling to continue giving to both host-city committees in a more polarized and contentious political environment. Indeed, the proportion of host-city committees’ total funds provided by donors to both committees decreased from an average of 38% from 2004 through 2012 to 8% from 2016 to 2024. The role of access-oriented donors in underwriting conventions has diminished.

CONCLUSION

Despite changes to nominating convention fundraising laws, host cities and political parties continue to raise large sums of money to pay for the conventions. These findings suggest that parties have replaced their public funds with private funds but have not reduced the fundraising expectations of the host cities. Given that contributions to host-city committees usually are tax-deductible and that cities are incentivized to follow through on the financial commitments made in their bids, it is unsurprising that they continue to raise large sums of money. This provides evidence that local businesses, corporations, and individual donors continue to robustly support presidential nominating conventions despite the decreasing importance of party conventions and the increasing political polarization in recent election cycles.

Our findings suggest that recent changes in the law, the waning importance of political party nominating conventions, and the current political environment have not deepened host cities’ reliance on access donors. The polarizing political environment and the rise of Trump in the Republican Party seem to have reduced the prominence of access-oriented donors to host-city committees. Our evidence supports this interpretation in two ways. First, the proportion of funds from local donors has not declined—in fact, it rebounded in 2016 and 2020 after a decline. Local donors and members of host-city committees are more likely to be contributing to support their cities’ efforts as hosts rather than as a means of attaining access for lobbying. Thus, increased reliance on local donors suggests less reliance on national lobbying organizations.

Our findings suggest that recent changes in the law, the waning importance of party nominating conventions, and the current political environment have not deepened host cities’ reliance on access donors. The polarizing political environment and the rise of Trump in the Republican Party seem to have reduced the prominence of access-oriented donors to host-city committees.

Second, the number of returning donors—those who give to the same party’s host cities in multiple election cycles and those who give to both parties’ host-city committees—and the proportion of funds they provide have declined substantially. Instead, host-city committees increasingly rely on the parties’ existing donor bases. If conventions are perceived as a festival for the political party and its activists, our evidence suggests that the parties’ donors increasingly pay for their own party. To be sure, the money is still coming from well-heeled individual and organizational donors; however, cities have decided they would rather solicit funds efficiently from a relatively few major politically active donors than risk antagonizing local taxpayers by using city funds to pay for a party for politicians. It also is possible that some of the access-oriented donors who previously gave to host-city committees are now giving to the parties’ convention accounts instead or to other opportunities for uncapped contributions (e.g., Super PACs or dark-money organizations).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/XXYPYP.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.