1. Introduction

The concept of migration networks, used in publications by organizations such as the Spanish Statistical Office (Reher et al., Reference Reher, Cortés Alcalá, González Quiñones, Requena, Sánchez Domínguez, Sanz Gimeno and Stanek2008) and the European Commission, is fundamental to understanding migration patterns.Footnote 1 The latter describes migration chains as “a process in which initial movements of migrants lead to further movements from the same area to the same area. In a chain migration system, individual members of a community migrate and then encourage or assist further movements of migration.”Footnote 2

Most academic studies of migration chains focus on the analysis of recent migration flows, demonstrating the great potential of their study to advance knowledge of contemporary migration movements. These studies rely on surveys of the migrant population as their main source (Gaete Quezada and Rodríguez Sumaza, Reference Gaete Quezada and Rodríguez Sumaza2010; Somerville, Reference Somerville2015; Van Meeteren and Pereira, Reference Van Meeteren and Pereira2018; Sierra-Paycha, Reference Sierra-Paycha2019). However, the transformation of social networks has reshaped the dynamics of migration networks in the modern era (Dekker and Engbersen, Reference Dekker and Engbersen2014), comparable to the revolutionary impact of transportation advances on physical mobility. This transformation underscores the dynamic nature of migration networks and highlights the distinct conditions under which historical migration movements operated. The physical and informational limitations of the past made migration chains and the resulting social capital even more crucial to the migration process. However, while some authors have referred to their operation, few have attempted to quantitatively analyze their historical impact and functioning (Capel Sáez, Reference Capel Sáez1967; García Abad, Reference García Abad2005; Silvestre et al., Reference Silvestre, Ayuda and Pinilla2015).

Our case study is the internal emigrations to the mining town of Linares (province of Jaén) during the third quarter of the nineteenth century. According to the Spanish population census of 1877, Linares had the second highest percentage of foreigners, only surpassed nationally by Madrid. The time period analyzed is particularly interesting because features of preindustrial elements were merging with those of industrialization and the first globalization. The socioeconomic and production factors of southern Spain were still those of a preindustrial economy, including the predominance of agriculture over other sectors, low levels of literacy, low productivity rates, and average wages close to subsistence levels (Bernal and Parejo, Reference Bernal, Parejo, Zubero, Agelán, de Motes I Bernet and Blanco2001; Parejo and Sánchez Picón, Reference Parejo, Sánchez Picón, Parejo and Sánchez Picón1999). However, the Spanish economy was already being influenced by the significant transformations occurring in the British economy and in those of the firstcomer countries.Footnote 3 In the case of Linares, the international demand for minerals and metals led to an exponential growth in the mining of these resources, which led to profound socioeconomic transformations in the municipality, together with strong population growth, which can be fundamentally explained by the arrival of a vast amount of workers (García Gómez et al., Reference García Gómez, Luque de Haro and Escudero2023). The role of migration chains was crucial in this context, as they facilitated the recruitment and relocation of these essential workers, thereby contributing to the development of the mining sector. As highlighted in several studies, the expansion of the mining industry required more than just seasonal labor; it necessitated the migration of workers who brought with them mining skills and techniques (Gontarski Speranza, Reference Gontarski Speranza2015; Knotter, Reference Knotter2015; Palacios-Mateo, Reference Palacios-Mateo2022).

To analyze the impact of migration chains, we use municipalities as the scale of observation. We consider this type of social capital to be based on personal relationships, which in the nineteenth century required physical proximity that rarely coincided with provincial administrative boundaries. In our approach, we use the entire stock identifiable through the population register of Linares, rather than relying solely on a sample of migrants. We then identify and characterize the migration chains through different mechanisms: (1) by determining the years of residence in Linares of the migrants to identify the pioneers from each place of origin and confirm the relationship between the moment of arrival and the subsequent migration intensity; (2) by analyzing the relationship between the place of origin and different spatial, socioeconomic, and family structure variables; (3) by using a spatial analysis based on the municipalities of origin and the migration intensity of each one, determining the trends and patterns followed; (4) by conducting an econometric analysis of the role of the variables related to the presence of migration chains and that of the principal variables identified by the literature to confirm the importance of each of them in determining the migration flows to Linares.

Among the reasons justifying the use of the framework of the migration networks in the study of population movements is their capacity to connect the micro and macro approaches. This framework is instrumental in conceptualizing migrations as contingent processes, deeply influenced by the social, political, and economic structures historically present both in the origins and destinations of migration (Boyd, Reference Boyd1989). Furthermore, it underscores the centrality of family unity, as opposed to the actions of isolated individuals, highlighting the familial networks as critical components in migration dynamics (Maia, Reference Maia2002). By exploring these chains, we gain valuable insights into the microlevel motivations and mechanisms facilitating migration to Linares during the third quarter of the nineteenth century. This reveals how personal and family networks act not only as conduits of information and support but also as critical assets in capitalizing on the opportunities arising from the era’s broader economic, social, and political transformations.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: the next section briefly reviews the theory and research on migration chains. Section 3 contextualizes the case study of Linares. Section 4 explains the sources and provides a descriptive analysis of the database. Section 5 details the methodology and presents the results, and section 6 summarizes the conclusions.

2. Migration chains

The concept of migration chains is part of the broader theoretical evolution of migration studies, which has significantly developed over more than a century. Starting with classical migration theories, the 12 migration laws identified by Ravenstein (Reference Ravenstein1885) constitute the first formulation of the “pull and push” model. According to these theories, individuals’ movements result from macroeconomic, structural, and impersonal laws, and migrants are seen as passive subjects (Lee, Reference Lee1966). Since the mid-twentieth century, neoclassical approaches have been applied to migration theory, treating migration as a rational calculation of associated costs and benefits (Massey et al., Reference Massey, Arango, Hugo, Kouaouci, Pellegrino and Taylor1993). The New Economy of Migration extends these approaches by emphasizing the family unit, rather than just the individual, as the decision-making entity for migration movements (Piore, Reference Piore1979; Sassen, Reference Sassen1993).

The migration network approach emerged in the 1980s decade and differs from previous approaches in that it focuses on the factors that explain the continuity of flows over time, the dynamic nature of networks and the consequences of their operation (Portes, Reference Portes1979). According to Massey (Reference Massey1988, p. 396), migration chains allude to “a set of interpersonal ties that link migrants, former migrants, and nonemigrants in origin and destination areas through the bonds of kinship, friendship, and shared community origin.” Massey et al. (Reference Massey, Arango, Graeme, Kovaci, Pellegrino and Taylor1998) also describe these networks as a “useful form of social capital” that can reduce the costs and risks associated with the migration process, thereby increasing the expected net returns to migration. For Putnam (Reference Putnam1993), the networks play a fundamental role in information transmission, particularly in the transmission of previous success, which generates trust and reputation as it provides evidence that commitment and collaboration can give rise to positive results. Participants cooperate in two main ways: (1) by providing information on job opportunities or introduction to the specialized labor market in the place of destination; and (2) by setting up a network of support services, such as accommodation which, seems essential in the early stages of the migratory experience (Boyd, Reference Boyd1989; Macdonald and Macdonald, Reference Macdonald and Macdonald1964; Wegge, Reference Wegge1998). Most of these classic studies argue that networks become more useful as the uncertainty of the migration project increases, which is the case with international migration. However, several authors have pointed out the interest of studying migration networks in internal displacements within the same country, despite the lower cultural differences or the assumption of greater information about employment opportunities in the destination areas (Capel Sáez, Reference Capel Sáez1967; Maia, Reference Maia2002; Recaño Valverde, Reference Recaño Valverde2002).

The pioneering work on the reconstruction of migration chains in Spain was conducted by García Abad (Reference García Abad2005). The author employed a methodology of “nominative tracing” of immigrants in the Bilbao Estuary between 1877 and 1935, selecting a sample of immigrants at their destination and reconstructing their migratory paths based on records found in the municipal registers of their places of origin, predominantly in the regions of Castile and León. Silvestre (Reference Silvestre2015) studied both qualitative and quantitative methods to investigate the occupational mobility of rural migrants who moved to Madrid in the 1950s. The findings highlight the crucial role of social networks in achieving success in the labor market. In a more recent study, Arroyo Abad et al. (Reference Arroyo Abad, Maurer and Sánchez‐Alonso2021) analyze the migration chains of Spanish and Italian migrants in Buenos Aires during the second half of the nineteenth century, using as a proxy the proportion of Spaniards or Italians with the same occupation in the same neighborhood. The authors find that Italians had higher wages than Spaniards because they established more effective migration networks, resulting in better economic opportunities. The paper of Eriksson and Ward (Reference Eriksson and Ward2022) examines issues such as segregation and the benefits associated with enclaves and relates them directly to the functioning of migration chains. Finally, García-Barrero (Reference García-Barrero2023) estimates the impact of temporality on migration to Mallorca during the tourist boom of the 1960s. He identifies migrant networks, considering the number of family members already established in the same tourist area as the migrant’s place of work in 1960 and alive in 1965.

3. The migratory boom of Linares in context

3.1. Migrations to Linares

Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, there was a significant rise in external and internal migrations across Europe. Traditionally, the historiography has considered the permanent migratory movements in Spain, both internal and external, during the majority of the nineteenth century to be relatively weak compared to those of other more developed nations (Sánchez Alonso, Reference Sánchez-Alonso2000), with an increase from the second half of the nineteenth century and, particularly, during the first decades of the twentieth century (Beltrán Tapia and de Miguel Salanova, Reference Beltrán Tapia and de Miguel Salanova2017; Pérez Artés and Sánchez Picón, Reference Pérez Artés and Sánchez Picón2023; Santiago-Caballero, Reference Santiago-Caballero2021; Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2005). In contrast, temporary migrations were considerably larger both in the preindustrial period and during the early phases of industrialization. Among other reasons, the importance of the agricultural sector and the seasonality of the crops favored the practice whereby rural workers combined their agricultural tasks with work in other sectors, particularly mining, during the nineteenth century and first decades of the twentieth century (Martínez Soto et al., Reference Martínez Soto, Pérez De Perceval Verde and Sánchez Picón2008; Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2002, Reference Silvestre2007).

The low level of permanent migration during the nineteenth century has been explained by both demand and supply factors. Demand factors primarily include the limited attractiveness of industrial centers, the temporary demand for labor for agricultural work in the latifundios and the high level of protectionism of the agricultural sector (Nadal, Reference Nadal1975; Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2005, Reference Silvestre2022; Tortella, Reference Tortella2017). Supply factors relate to low demographic growth, the lack of agricultural development, challenges in land distribution and access, conservatism, risk aversion, and the pervasive “poverty trap” experienced by much of Spain’s rural population (Carmona and Simpson, Reference Carmona and Simpson2003; Gallego Martínez, Reference Gallego Martínez2001; Sánchez Alonso, Reference Sanchez-Alonso2000). However, the behavior of these factors must not have been the same throughout Spain. While in most territories, the demand factors mostly responded to the strength or weakness of the internal market, in places where export-oriented sectors were predominant, such as in the case of the mining basins, the economy was primarily driven by external demand. During the growth phases of the different mining basins, workers from other municipalities and provinces covered a high percentage of the labor demanded (Martínez Soto et al., Reference Martínez Soto, Pérez De Perceval Verde and Sánchez Picón2008; Palacios-Mateo, Reference Palacios-Mateo2022).

The panorama of internal migrations in Spain during the second half of the nineteenth century was very diverse. The destination of migration flows was concentrated in the principal cities, and the rest of the territory remained in a situation of relative immobility. Madrid and Barcelona acted as the principal centers of attraction of workers as a result of their role as the country’s capital and main industrial center, respectively. Other large cities, such as Seville, Bilbao or Zaragoza were also attraction centers for migrants. However, the volume of the flows toward these latter cities was considerably lower and was restricted mainly to the population in the nearby areas (Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2001; Sánchez Picón, Reference Sánchez Picón2005; Beltrán Tapia and de Miguel Salanova, Reference Beltrán Tapia and de Miguel Salanova2017; Santiago-Caballero, Reference Santiago-Caballero2021).

In Andalusia, aside from the largest cities such as Seville or Malaga, certain exceptions are mainly linked to mining activity. Among them is the case of Linares. The uniqueness of this city, one of the key scenarios of the Spanish mining boom of the nineteenth century, is illustrated in studies such as the one conducted by Santiago-Caballero (Reference Santiago-Caballero2021) on internal migrations in Spain between 1840 and 1870. In this study, the cases of Madrid, Barcelona, and Linares stand out on a national level as in these cities during the period 1840–1870, the immigration rates were more intense, and the average distance of the migration movements was longer than the overall average.

3.2. Linares: economic characteristics and demographic growth

According to Nadal (Reference Nadal1992), Andalusia was the most important mining region in Spain. The emergence of mining capitalism led to the insertion of many Andalusian districts into the global market through mercantile circuits fostered by mining. From the outset, and on the eve of the beginning of Spain’s industrialization process, the Andalusian minerals and metals were, together with wines and oils, one of the principal lines of regional exports.

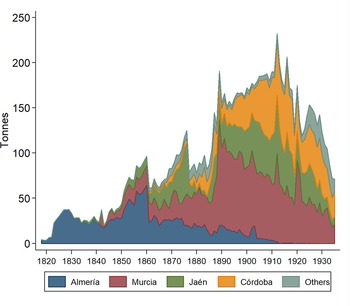

From the mid-nineteenth century until the first decades of the twentieth century, Andalusia’s mining production had achieved a dominant position in Spain, accounting for about half of the value of Spanish mining production. The hegemony of the Penibetic mines (mainly Almería) at the start of the private mining activity of lead minerals, which was penalized by the law of 1825, began to wane from the mid-nineteenth century. The exhaustion of some of these deposits and the technological and economic non-feasibility of small mining operations reduced the metal production of the province of Almería throughout the second half of the nineteenth century. Until the 1850s, the lead from Sierra Morena had not been able to compete with that of the Mediterranean coast, but in the old district of Linares, the investments made by a group of British companies reactivated the mining activities.Footnote 4 The modern technology arising from the widespread use of steam for drainage tasks, together with the integration of mining and metallurgical installations, was behind the success of the lead from Linares (Artillo González et al., Reference Artillo González, Garrido González, Molina Vega, Moreno Rivilla, Ramírez Plaza, Sánchez Caballero and Solís Camba1987; Torró Gil, Reference Torró Gil2023). The improvements in the transport network were also decisive in the reactivation of the mines in the area.Footnote 5 The primacy of the province of Jaén as the leading lead producer was finally consolidated with the growth of the neighboring district of La Carolina (Sánchez Picón, Reference Sánchez Picón and Prieto2006; Sánchez Picón et al., Reference Sánchez Picón, García Gómez and Pérez Artés2023).

Figure 1 shows this “relay race,” in Nadal’s words (Nadal, Reference Nadal1975) that occurred in lead mining and metallurgy during the nineteenth century and the first third of the twentieth century. From 1840 to 1850, the predominance of Almería gave way to two new producing provinces, Jaén and Murcia, which, from the beginning of the twentieth century, became the principal producing areas of lead ingot. The development of the Linares-La Carolina district (Jaén) experienced strong growth from 1860 to 1880. Subsequently, it suffered with particular intensity the impact of the “lead crisis,” caused by a sustained depreciation that was not overcome until well into the 1890s. From then, and with an increasing contribution of the mines located in the La Carolina district, Jaén, together with Córdoba and Murcia, accounted for 90% of Spanish production (Sánchez Picón, Reference Sánchez Picón2005).

Figure 1. Production of metallic lead in Spain (1818–1935). Data in thousands of tonnes.

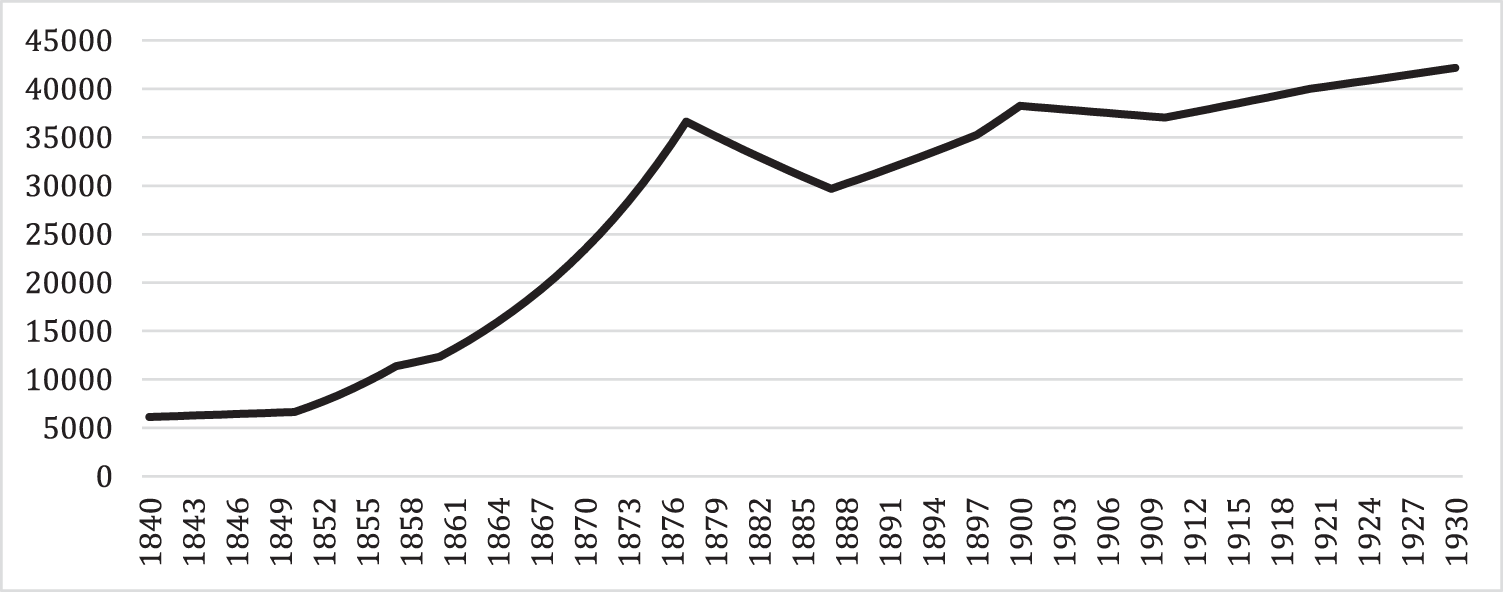

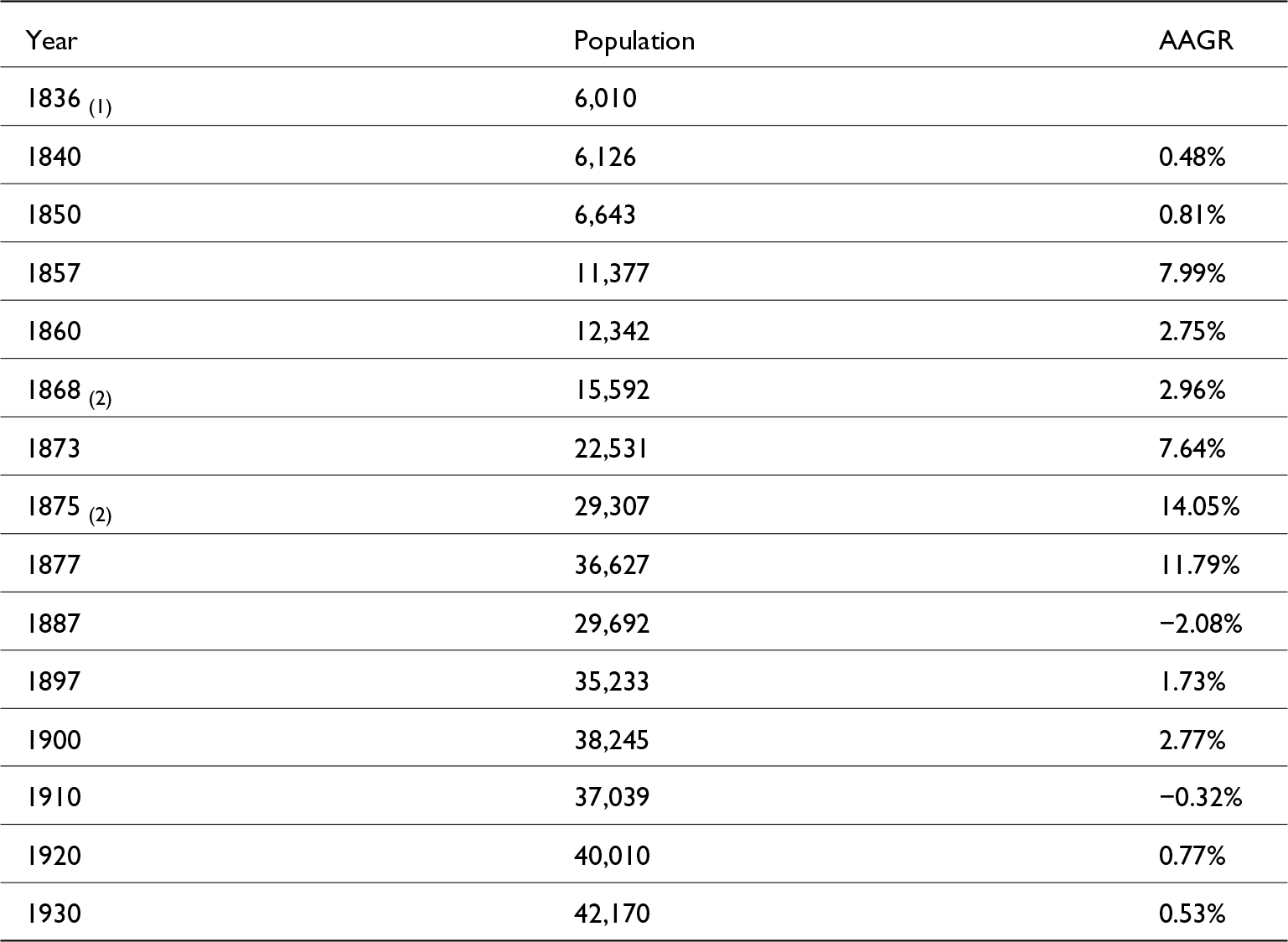

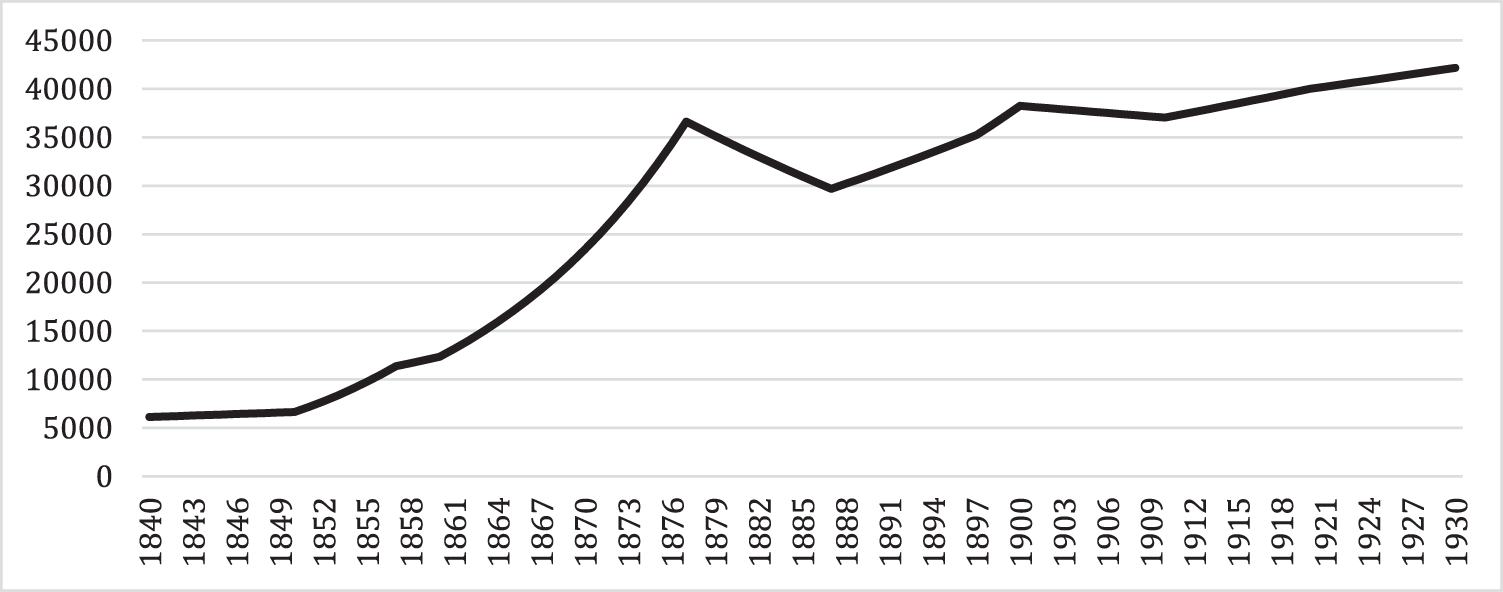

The evolution of the population of Linares from 1840 to 1930 is shown in Figure 2. In the decades immediately preceding this period, Linares experienced considerable demographic growth, although it was much lower than in the subsequent decades (Torró Gil, Reference Torró Gil2023). The increase in the population was particularly intense between 1850 and 1877, causing the population of Linares to increase from 6,643 to 36,627 inhabitants in less than 30 years (Garrido González and Tuñón de Lara, Reference Garrido González and Tuñón de Lara1990; Garrido González, Reference Garrido González1994; López Villarejo, Reference López Villarejo1994). While the increase in the Spanish population between 1850 and 1877 occurred at an annual rate of 0.43% (Maluquer, Reference Maluquer2008), the number of inhabitants in the city of Linares grew during this same period at a rate of 6.53%. The mining industry of the nineteenth century was intensive in the labor factor, and the demand for labor encouraged and sustained large population displacements, among which the case of Linares particularly stands out.

Figure 2. Evolution of the population of Linares (1840–1930).

The evolution of the population of Linares and that of the demographic variables that determined it (births, deaths, and migration movements) is disaggregated by decades, between 1840 and 1920 in Table 1. As we can observe, the contribution of migrations largely explains its growth. In fact, the high levels of mortality experienced in Linares during the second half of the nineteenth century, in the majority of the decades, led to the number of deaths being even higher than that of births.Footnote 6 As previously indicated, the period when the rate of population growth was fastest was between 1850 and 1877. Between this last year and 1887, we can observe a fall in inhabitants. The relationship between migrations and the economic situation of the mining sector seems evident. The “lead crisis” of 1880–1894 affected the economy of Linares intensely and reduced the demand for labor. Therefore, we can confirm that during the 1880s, the city began to experience negative migrations, to which we should also add that the natural growth of the population was also negative during these years. The partial recovery of international prices from 1894 reactivated the sector, generating new population growth during the final years of the nineteenth century. However, despite the considerable contribution of migrations during these years, the increase in mechanization made possible to boost production with a smaller rise in the number of workers than during the first growth phase (Sánchez Picón, Reference Sánchez Picón1995).

Table 1. Participation of the different demographic variables in the growth of the population of Linares (1840–1920)

Source: Own elaboration from Libros de Nacimientos, defunciones y matrimonios (1840–1870) and individual population registers (1836, 1840 and 1850, 1857) (MHAL). Libros de Registro Civil de la Ciudad de Linares 1870–1920 (Registro Civil de Linares). Spanish census 1860, 1877, 1887, 1897, 1900, 1910, and 1920 (INE). Note: The data on net migrations have been calculated through the difference between the natural growth of the population (births–deaths) and the real growth of the population, reflected by the data of the different population censuses and registers. For the years for which no population censuses or registers are available, the population has been calculated based on the average annual variation rate between the immediately preceding and immediately following census or register.

aDue to a lack of data regarding the number of births in 1864, 1865, and 1866, we have calculated the number of births for this decade as the average annual births of the year for which we have records and have multiplied them by 10.

4. Sources and descriptive analysis of the database

The main database for this research is the 1873 population census of the city of Linares and the birth and death records of 1840–1920. For some variables, the Spanish population census of 1860 was used.Footnote 7

We have constructed two databases: the first contains more than 22,500 observations comprising all the individuals registered in the 1873 register. Among the variables included are those related to the family structure, the spatial distribution of the families and the individuals and the socioeconomic status of the subjects. The second database contains information at the municipal level for all municipalities in Spain on the intensity of their migration flows to Linares, as well as those of neighboring municipalities. It also includes data on the distance of each municipality from Linares, its population and the year of arrival of the first emigrant to Linares. The information on the size of the municipalities, the migration intensity of the neighboring municipalities and the literacy rate of the municipality in 1860 has only been included for those places for which we have at least one migrant (737 municipalities). Furthermore, due to the impossibility of obtaining certain variables on a municipal level, we have completed the database with information on a provincial scale regarding wages (Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso, Reference Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso2004) and the magnitude of the temporary migration flows (Silvestre, Reference Silvestre2007). The georeferencing of the streets and the classification of the homes in the neighborhoods of the city of Linares have been conducted using the map of this city in 1876 (Andújar Escobar, Reference Andújar Escobar2017, p. 397).Footnote 8

Retrospective cross-sectional data have potential shortcomings, as highlighted by Borjas (Reference Borjas1987) and Abramitzky and Boustan (Reference Abramitzky and Boustan2017). One limitation is that the data only include individuals who were in Linares at the time of the population census and does not account for migrants who returned or moved to other destinations before 1873. In any case, the intense economic and population growth registered between 1850 and 1878 suggests that migrants would be less prone to return or change locality choices until the onset of the “lead crisis” of 1880–1894. Additionally, cross-sectional data may not capture all changes in individuals’ occupations or home addresses since their arrival in Linares. Therefore, some effects associated with these migration chains would not have been captured. Furthermore, the estimates may be biased due to a different propensity to change jobs or housing among the participants of some migration chains than others or the natives of Linares. Although these potential biases have been considered, other researchers have used cross-sectional retrospective data to provide valuable insights into various aspects of migration literature (García-Barrero, Reference García-Barrero2023; Silvestre et al., Reference Silvestre, Ayuda and Pinilla2015).

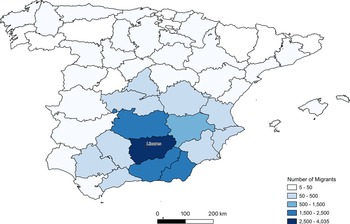

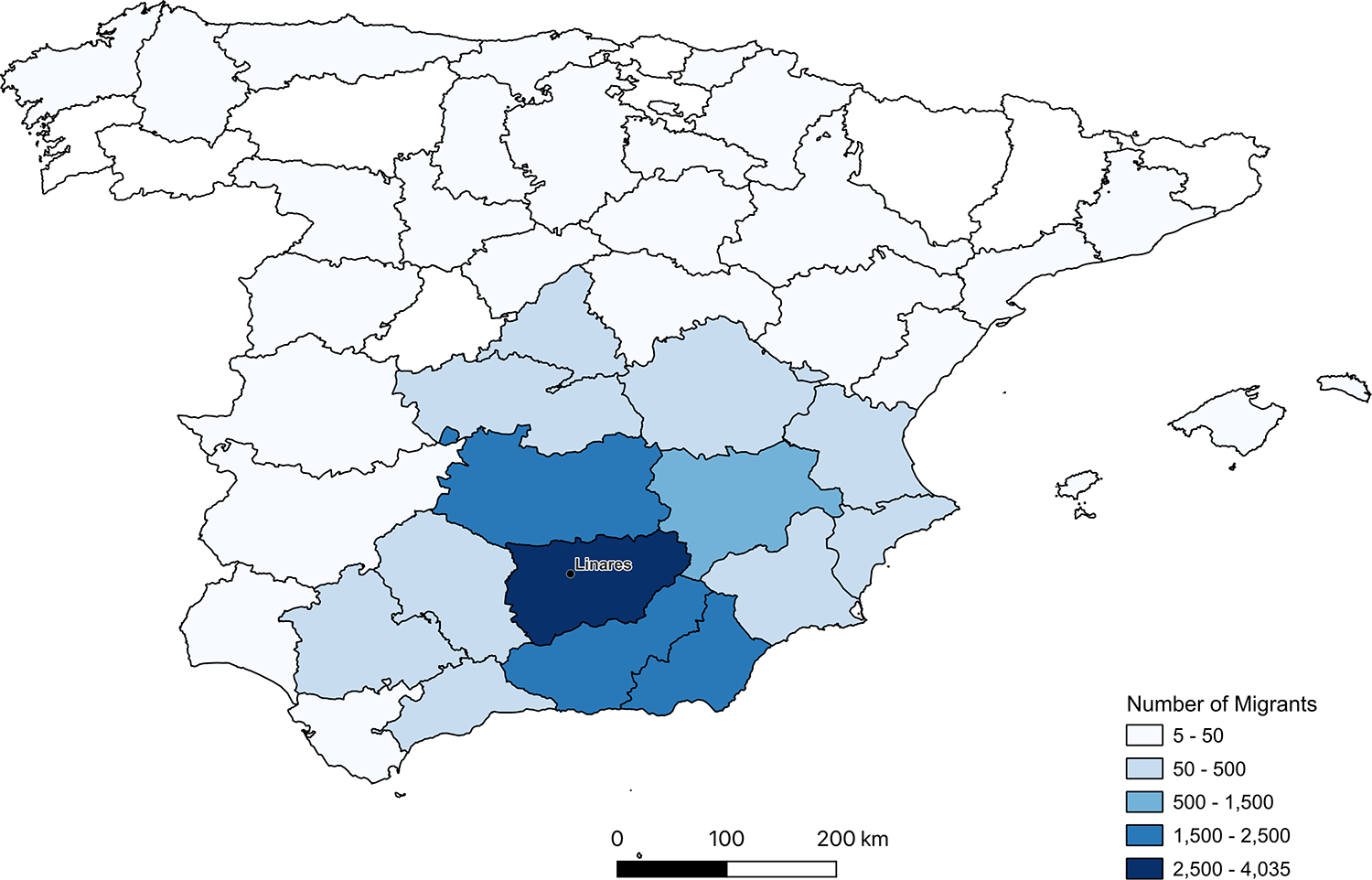

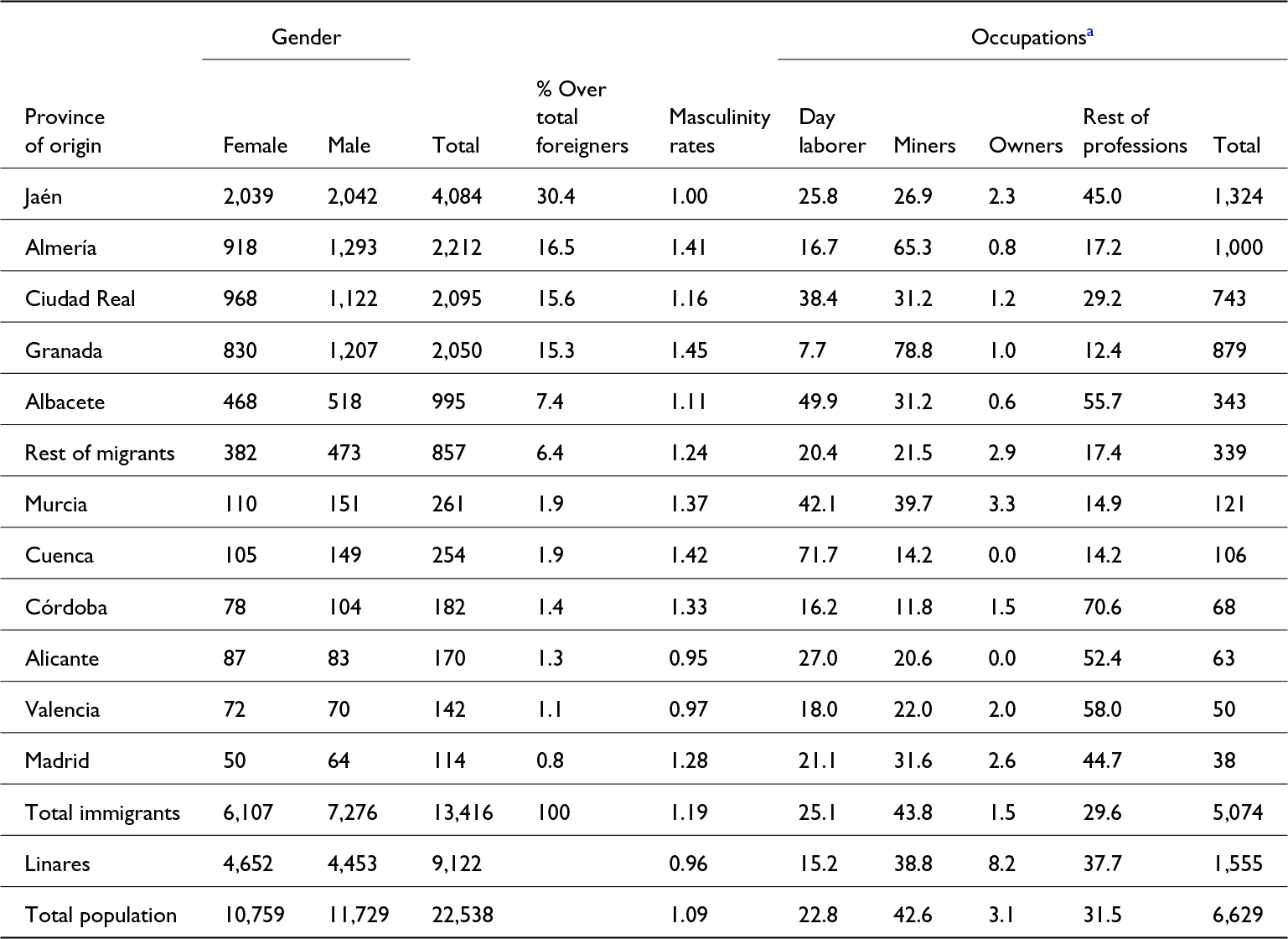

The 1873 population register contains a total of 22,531 inhabitants of which 13,409 were immigrants. Therefore, more than half of the inhabitants of Linares in 1873 (59.5%) were not native of this municipality and 18.1% were from other municipalities in the province of Jaén. As shown in Figure 3, the majority of the migrants were from the south-east part of the peninsula. In order of importance, the immigrant inhabitants of Linares were from the provinces of Jaén, Almería, Granada, Ciudad Real, and Albacete. However, this level of territorial disaggregation does not allow us to see the characteristics of the migration chains. Therefore, it is necessary to change our scale of observation.

Figure 3. Origin of the immigrants of Linares 1873 by province of origin.

Analyzing the origin based on a municipal observation scale with individual data enriches the study considerably. Figure 4 displays the number of migrants according to the municipality of origin. The 10 municipalities that received the highest number of migrants, ordered from the most to the least, were Albuñol (Granada), Baeza (Jaén), Úbeda (Jaén), Jaén capital, Andújar (Jaén), Villanueva de los Infantes (Ciudad Real), Ibros (Jaén), Manzanares (Ciudad Real), La Solana (Ciudad Real), and Alhama de Almería (Almería). The scarce participation of the municipalities of the interior districts of eastern Andalusia (Surco Intrabético), is noteworthy. These are relatively close to the receiving area compared to other towns located further away, such as those of the high Andalusian mountains and the Alpujarras. The study by Torró Gil (Reference Torró Gil2023) on migration movements to Linares before 1835 highlights the minimal representation of migrants from regions like the Cordoba countryside. However, in this previous period, the percentage of migrants of the total population was smaller, and the average distance from the places of origin was significantly shorter. The great majority of the residents born outside were from municipalities located within a radius of 30 km from Linares.

Figure 4. Origin of the immigrants in Linares in 1873 by municipalities of origin.

In order to illustrate the intensity of the migrations to Linares, Figure 5 depicts the percentage of immigrants in Linares from a specific municipality over the total population of the municipality of origin in 1873. Hence, Santa Cruz de Marchena (Almería) is first, as the immigrants from this town in Linares represented 12% of the estimated population of this municipality in 1873. It is followed by Fuensanta (Albacete) with 11% of immigrants, Torreblascopedro (Jaén) with 9%; Albuñol (Granada), Puebla del Príncipe (Ciudad Real), Ugíjar (Granada) with 7%; Alhabia (Almería), Felix (Almería), Ibros (Jaén), Alhama de Almería (Almería), and San Carlos del Valle (Ciudad Real) with 6%. The appearance of more isolated nuclei, such as Almadén in the south-west of the province of Ciudad Real is significant. We can also observe areas relatively close by with intensity rates of under 1%. This is the case of the east of the province of Jaén, the Cordoba and Seville countryside or the north of the province of Granada.

Figure 5. Migration intensity by municipalities in Linares 1873.

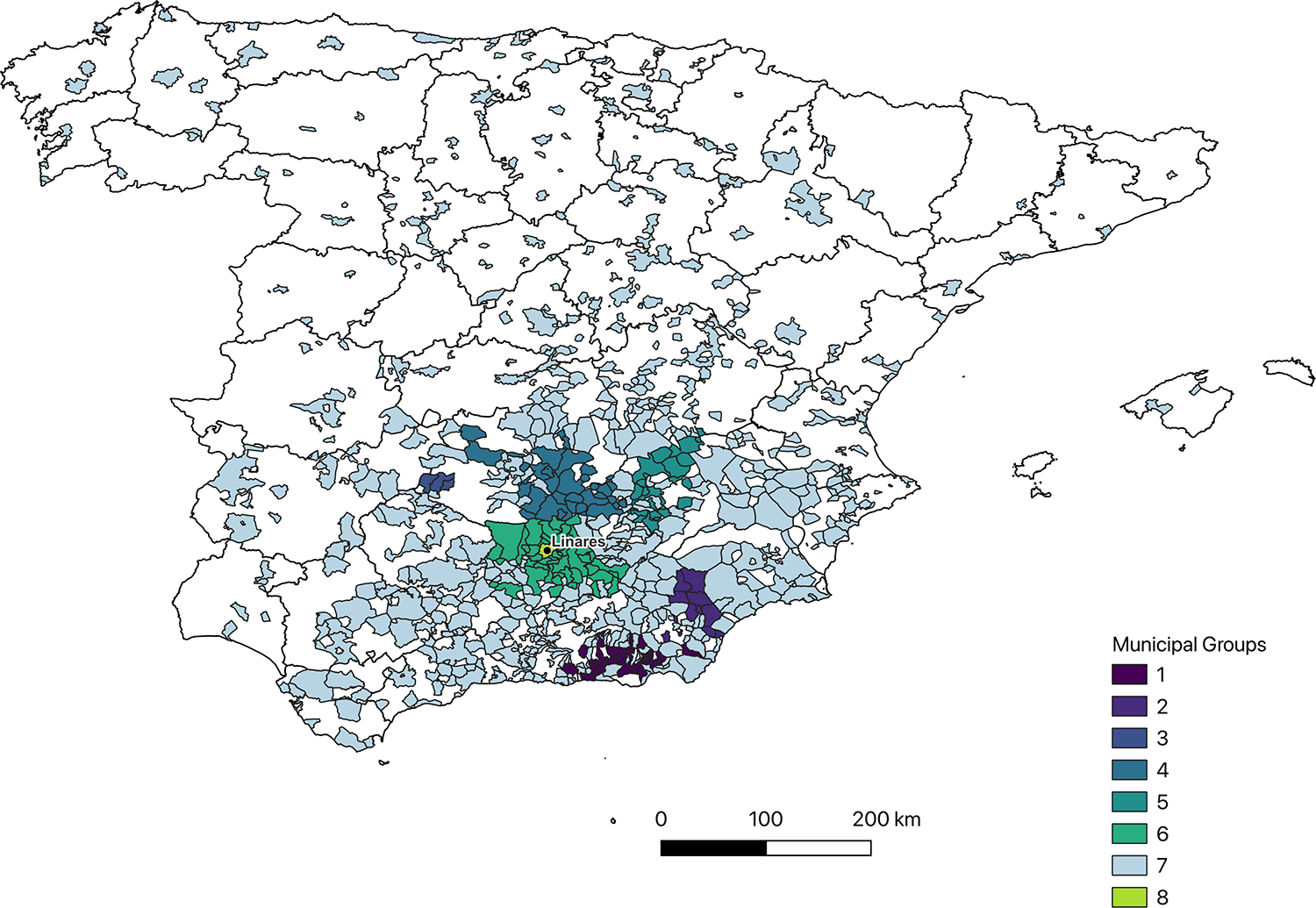

In order to facilitate the comparison of the migrants in accordance with their nature and to enable the study of the phenomenon of migration chains, Figure 6 classifies the municipalities with at least one migrant into seven groups:

• G-1. Mountains of Granada and Almería. The municipalities of the district of the Alpujarras and some municipalities of the neighboring districts of Alto and Bajo Andarax, Río Nacimiento, the countryside of Dalías and Níjar and the Granada Coast. This area included the mining basins of the Sierra de Gádor and the Sierra de Alhamilla, which were characterized by lead mining from the year 1817.

• G-2. The plateaus of the North of Almería. This category is made up of all the municipalities of the Vélez district and some of the districts adjacent to Alto and Bajo Almanzora and that of Campo de Tabernas. It was a mining catchment area as it includes the Almagrera Sierra and the Bédar Sierra.

• G-3. Almadén and its surrounding area in the province of Ciudad Real, where the mining region of Almadén is found, is one of the areas of greatest mercury production on an international level. It has been exploited for more than 2,000 years.

• G-4. The Mancha Baja: This is made up of Campos Montiel and Calatrava.

• G-5. The Mancha Alta: Includes the municipalities of Sierra Alcaraz and Segura.

• G-6 Hinterland of Linares: municipalities less than 100 kilometers from Linares.

• G-7 Rest. This group includes all those municipalities with less than 0.5% of migration intensity.

• G-8 Linares. Refers to the natives of Linares.

Figure 6. Distribution of municipalities by groups.

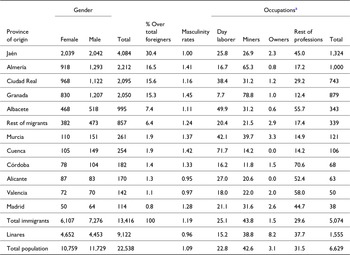

Concerning the distribution of the individuals by sex, the differences in the masculinity rate by the province of origin are noteworthy (see Table A2). The provinces of Almería, Granada, Cuenca, and Murcia have the highest masculinity rates. Meanwhile, the population originating in Linares, the rest of Jaén, Alicante, and Valencia have the lowest number of men to women. Although it is still too early to conclude, the provincial differences seem to reflect the two types of migration referred to by López Villarejo: “those who come alone and those who come with the whole family” (López Villarejo, Reference López Villarejo1994, p. 62).

These differences in the migratory project depending on the province of origin are also related to the professional specialization and the different skills predominant among the migrants from each place. Therefore, we can see in Table A2 that the percentage of men from Almería and Granada employed in mining was considerably higher than the average. Meanwhile, among those from Ciudad Real and the rest of the provinces, there was a high proportion of day laborers. The men from the rest of Jaén were more concentrated in the “rest of occupations.” Finally, concerning owners, we can observe a clear predominance of those born in Linares. The large number of migrants employed in mining contrasts with the very small proportion of non-natives represented in the sector in the 1830s. In 1835, they accounted for less than 5% of the total number of miners, whereas by 1873, this figure had risen to 80% (Torró Gil, Reference Torró Gil2023). The substantial increase during this period indicates that most of the employment demand associated with the mining boom was met by migrant workers.

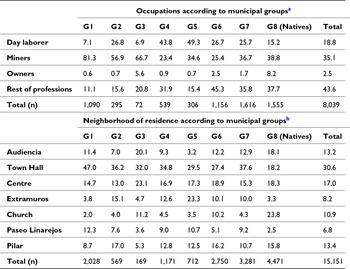

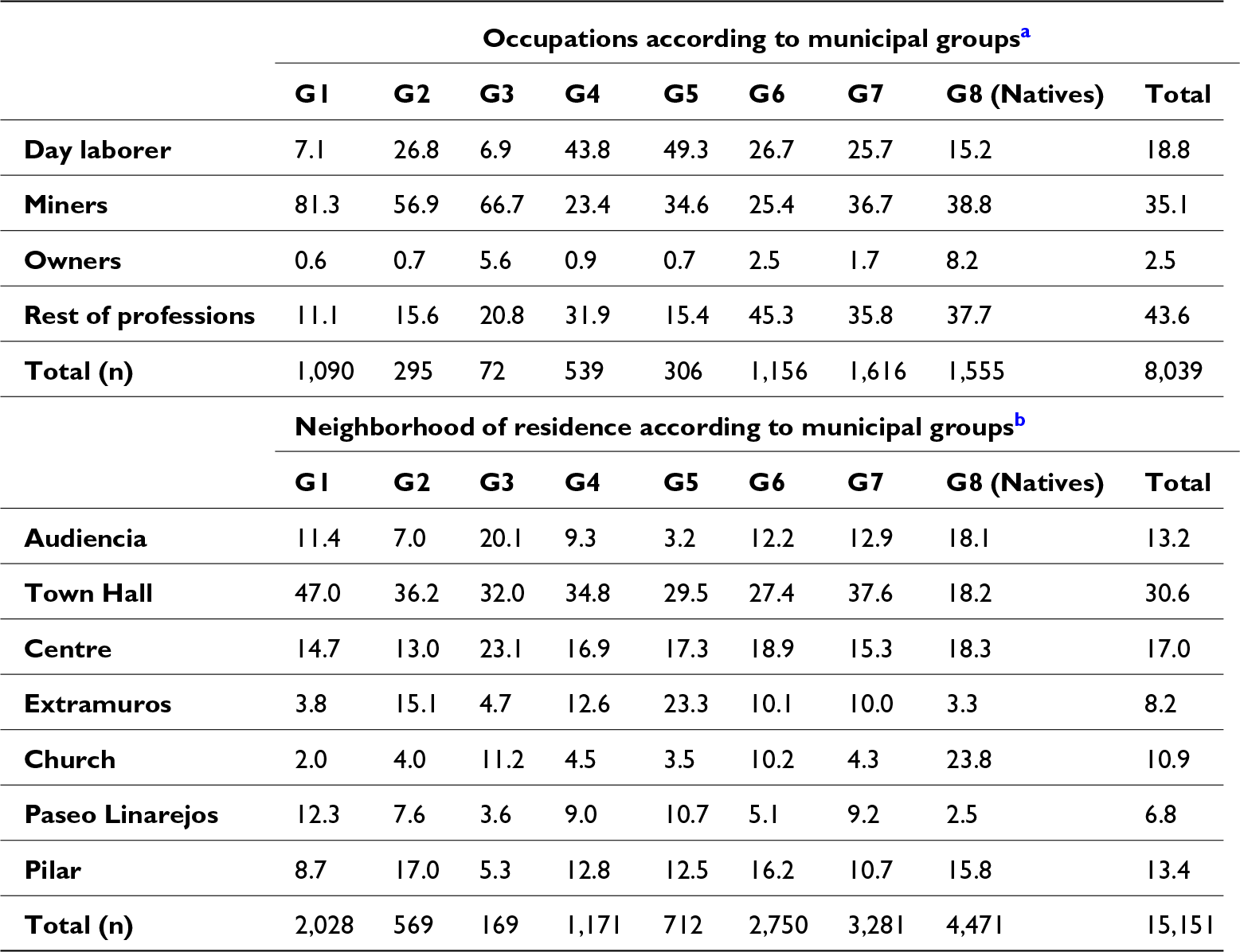

This reasoning is made in provincial terms, but, as we argued above, the differences between the migration chains can be seen more clearly at a smaller level of spatial disaggregation. If we analyze the occupational distribution of the groups of municipalities, in Table 2 we can observe that the production specialization of the migrants was even more acute. While in G-1, more than 80% of the male heads of family over 15 were miners, in G2 and G3 they represented approximately 57% and 68%, respectively. This percentage is much lower in the rest of the groups of municipalities. For the day laborers, the highest percentage can be observed in males from G-4 and G-5 (44% and 49%, respectively). Finally, about the owners, the highest figure can be found in the natives of Linares (8.2%), followed by emigrants from the towns of G-3 (5.6%) and did not reach 3% in any other district.

Table 2. Distribution of the principal occupations and the neighborhood of residence in Linares in accordance with the municipal group of origin

Source: Own elaboration based on the information of the population register of Linares 1873 (Municipal Archive of Linares).

Note: Values in % except for “Overall total” in which absolute values are shown.

a Values in occupations calculated over the total of males of 15 years or over of each of the municipal groups, of those born in Linares or those of the whole population.

b Neighborhood of residence calculated over the total of individuals of 15 years or over of each of the municipal groups, of those born in Linares and or those of the whole population.

The second part of Table 2 shows the distribution of the migrants in the different neighborhood of Linares by the division into municipal groups, given that, as previously explained, we consider that this division reflects the characteristics of each migration chain more accurately. Clearly, the population distribution across the different neighborhoods is not homogeneous. Instead, we notice that the migrants of each of the municipal groups tended to concentrate in certain districts: the migrants of G-1 tended to settle more intensely than the rest in the neighborhood of the Town Hall and the Paseo Linarejos; those from G-2 preferred, to a substantially greater extent than the group as a whole, the Pilar neighborhood; a greater percentage of families from G-3 than the rest resided in homes located in the neighborhood of Audiencia and the center; the neighbors from G-4 were distributed in a relatively similar way to the distribution of the inhabitants of Linares as a whole, with a slightly higher concentration in the Extramuros neighborhood; those from G-5 could be found in Extramuros and Paseo de Linareojos; the neighborhood of Pilar stands out for its high concentration of individuals from the Hinterland (G-6) and, finally, the natives of Linares were concentrated in the church, Pilar and Audiencia neighborhoods.

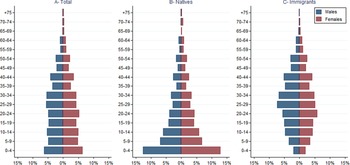

The demographic transformations that gave rise to mass flows of migrants to Linares from the mid-nineteenth century are also reflected in the age structure of the population. Three population pyramids are represented in Figure 7. Pyramid A includes all the inhabitants of Linares of 1873, Pyramid B includes the inhabitants born in the city of Linares, and Pyramid C includes the residents of Linares born in another municipality. In the first pyramid (A), the girls and boys between 0 and 4 years of age represented 12.7% of the population. This percentage does not fall below 10% until the cohorts of 35–39 years of age, which indicates an atypical behavior for a nineteenth-century society. The answer can be found when we compare the pyramid of the population born in Linares (B) with that of the immigrants (C). While in the first, more than 25% of the individuals were between 0 and 4 years old, this cohort represented 4% among the non-natives. Meanwhile, the cohorts between 15 and 44 years of age accounted for 38% of the population born in Linares and 63% of those born in other municipalities. The differences between the two population pyramids are explained by the intense arrival of migrants of working age.

Figure 7. Population pyramids of Linares (1873).

5. Methodology and results

This section presents the results of different econometric models that analyze the significance and robustness of the relationships observed in the descriptive tables, controlling for various variables.

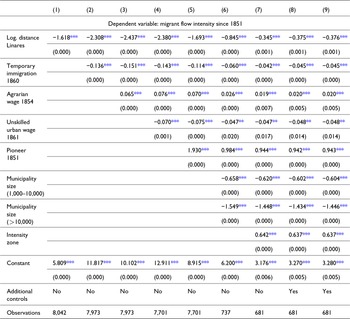

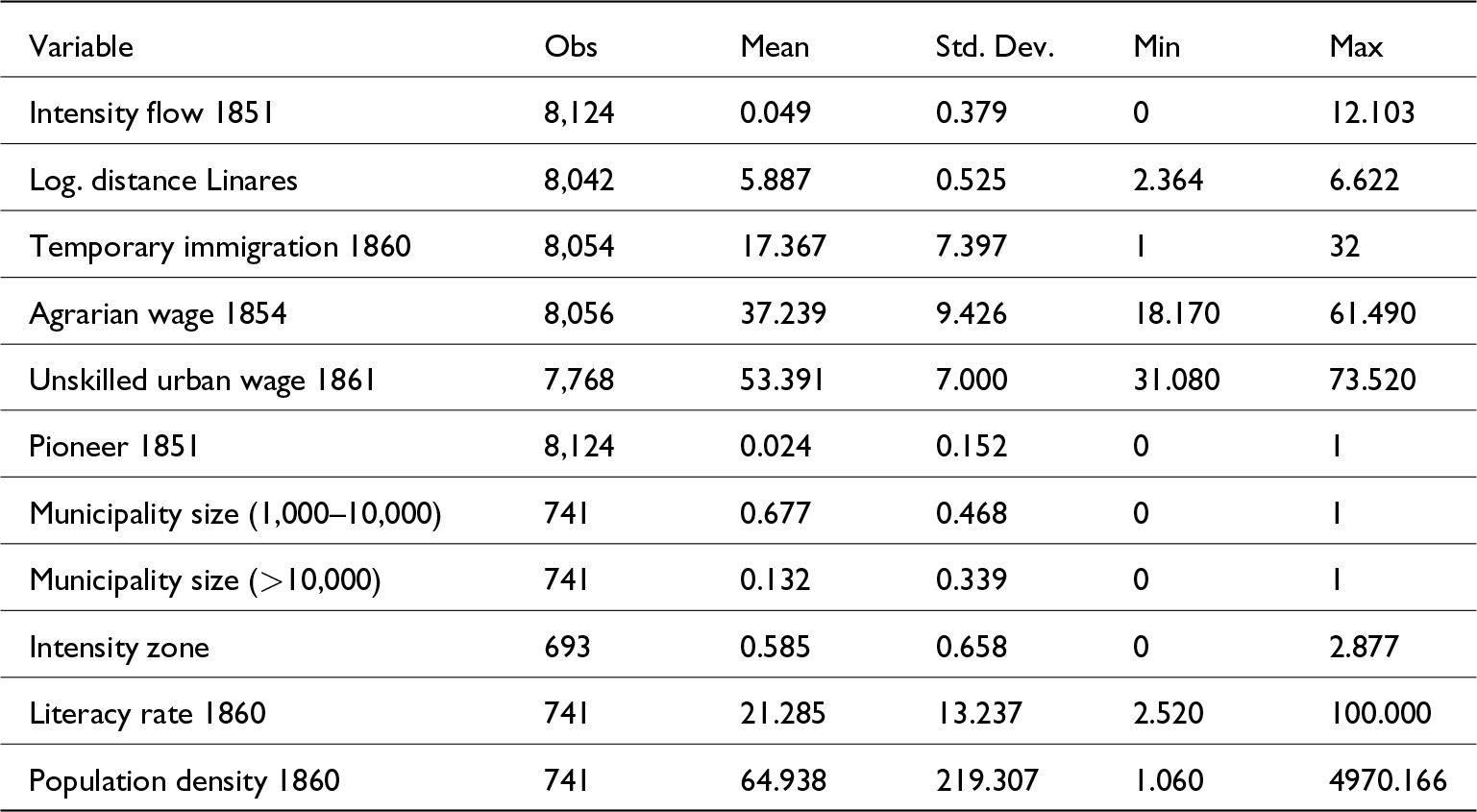

The models in Table 3 study the factors that determined the greater or lesser migration intensity to Linares of each municipality (Inti) from 1851 to 1873. The population of each municipality in 1873 has been calculated based on the jure population in the closest population censuses: that of 1860 and that of 1877. The analysis method used is the Poisson Model (Ordinary Least Squares [OLS] model in Table A4). For these estimates, we have used the information from the database of all of the Spanish municipalities. A summary of the explanatory and control variables included in these models is presented in Table A3.

Table 3. Determining factors of migration to Linares in the years before 1873. Poisson Model

Note: The number of observations in Model 6 is reduced due to the inclusion of new variables, which are limited to municipalities with at least one emigrant record in the Linares 1873 population census.

Robust p values in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

In order to study the phenomenon of the migration chains, we have included, in the Equation 1, as an explanatory variable the presence of pioneers of this municipality in Linares in the first phases of the migratory boom (Piooner1851i). This dichotomous variable takes the value of 1 if there was a migrant from this municipality in Linares in the year 1851 and 0 otherwise. Furthermore, given that the influence of a migration chain is not limited to the municipal administrative boundaries, but the information and social nexus usually extend to the neighboring town, we have included a variable that represents the migration intensity in the adjacent municipalities (Zoneintj), calculated as the sum of the migration intensity of the municipalities that are less than 25 km from the municipality in question, weighted by the size of the population of each of them.

\begin{equation*}Zonein{t_j} = \,\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_j^i In{t_i}\,*\,Populatio{n_i}}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{}^{} Populatio{n_i}}}\end{equation*}

\begin{equation*}Zonein{t_j} = \,\frac{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_j^i In{t_i}\,*\,Populatio{n_i}}}{{\mathop \sum \nolimits_{}^{} Populatio{n_i}}}\end{equation*}Furthermore, other control variables have been included. Distance is used as a proxy for moving costs (Kmi). The distance in a straight line between the municipality of origin and Linares in km is an indicator of travel, information and opportunity costs. For natives, the distance variable is equal to 0. In the regression, this is equivalent to interacting distance with a dichotomous variable that scores 1 if the individual is an immigrant. Additionally, we utilize the temporary internal immigration rate of the province in 1860 (Tpmigp), based on Silvestre’s (Reference Silvestre2007) estimates, to account for pull factors encouraging temporary immigration to these areas. The provincial salary level, based on the estimates of Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso (Reference Rosés and Sánchez-Alonso2004) for agricultural (AgWage1854p) and unskilled urban wages (UnskWage 1861p) in 1854 and 1861 respectively, is used to control for potential impact of wage differences between different provinces of origin. It is logical to hypothesize that lower salary levels within a province would act as a push factor, encouraging migration to Linares in search of better economic opportunities. In the case of urban salaries associated with unskilled jobs, higher wages could attract individuals from rural areas to provincial capitals, thus creating a competing migratory pull away from Linares. The municipality size (Munsizei) is a categorical variable that takes different values based on the estimated population in 1860: lower than 1,000, between 1,000 and 10,000, or higher than 10,000 inhabitants. Individuals from rural areas and smaller municipalities are expected to have a greater propensity to migrate than those from cities. The literacy rate in each municipality according to the population census of 1860 (Lit1860i) is also included to control for the possible impact that differences in human capital could have had in the migrations flows; the estimated population density for each municipality based on the relationship between the population in 1860 and the area of the municipality in km2 (Popdensi). Higher population density could indicate that an area is approaching its Malthusian limit, thereby increasing the propensity to migrate due to land scarcity and competition for jobs. However, it’s also considered that rural areas, despite having lower population densities, might exhibit higher migration rates due to other factors such as a lack of local employment opportunities.

\begin{align}In{t_i} & = \,\alpha + \,{\beta _1}K{m_i} + \,{\beta _2}Tpmi{g_p} + {\beta _3}AgWage{1854_p} + {\beta _4}UnskWage{1861_p} + {\beta _5}Pi{o_i} \nonumber\\

& \quad + \,{\beta _6}Munsiz{e_i} + {\beta _7}Zonein{t_i} + \,{\beta _8}Lit{1860_i}\, + {\beta _9}Popden{s_i} + \,\varepsilon \end{align}

\begin{align}In{t_i} & = \,\alpha + \,{\beta _1}K{m_i} + \,{\beta _2}Tpmi{g_p} + {\beta _3}AgWage{1854_p} + {\beta _4}UnskWage{1861_p} + {\beta _5}Pi{o_i} \nonumber\\

& \quad + \,{\beta _6}Munsiz{e_i} + {\beta _7}Zonein{t_i} + \,{\beta _8}Lit{1860_i}\, + {\beta _9}Popden{s_i} + \,\varepsilon \end{align}As illustrated in Table 3, the variables most closely associated with the phenomenon of migration chains have a significant impact on the intensity of migration. The presence of individuals from a certain municipality in Linares since 1851 shows a positive and significant association with the magnitude of the migrant flows. Specifically, the presence of pioneering individuals is found to enhance migration intensity in our model, with a magnitude of change ranging from 1.93 to 0.94. Similarly, another of the variables with the greatest effect on the migration intensity is the intensity in the adjacent municipalities. It can be observed that for every one per cent increase in the intensity of the area, there is an approximate 0.64 per cent increase in the intensity of the municipality.

In addition, the majority of the remaining variables included in the analysis were found to be significant, with the expected sign of their coefficients. The distance to Linares was negatively related to the migration intensity. Municipalities situated at a greater distance from Linares exhibited a lower migration intensity, while those situated at a shorter distance exhibited a higher migration intensity. Although the proximity factor is important for understanding migration intensity, it does not explain the notable differences between municipalities. These could be due to several factors such as Malthusian behavior or migration pressure derived from the greater population density to the available resources; production specialization which would have conditioned, to a certain degree, the knowledge and skills of the product of these places (in this case mining tradition); and the existence of previous migration networks between the place of origin and destination.

Regarding municipal size, those with a smaller population exhibited a greater population loss. Conversely, medium-sized municipalities (with a population between 1,000 and 10,000) and large municipalities (with a population of over 10,000) exhibited a lower migration intensity. Another variable that has been shown to be significant is the intensity of the temporary migration flows toward the provinces of each municipality. As anticipated, the population whose municipalities belonged to the provinces in which temporary immigration was more prevalent exhibited a lower propensity to migrate to Linares. It could be expected that the same factors that explain the flow toward these provinces, such as the labor opportunities, would have had the opposite effect on the expulsion of the working population. Regarding the effect of salaries, the results are not quite as expected. Urban unskilled wages behave as hypothesized. Higher salaries in the cities of the province reduced the propensity to migrate to Linares by acting as an alternative destination. However, the result associated with the agricultural wage variable has the opposite sign to that expected, showing a positive correlation with the intensity of migration. Among other factors, the fact that wage data are not available at the municipal level but at the provincial level could be one of the reasons for this puzzling effect. The penultimate model includes a control variable for the literacy rate in 1860. The last model includes population density per square kilometer in 1860. No significant changes are observed in the effect of the remaining variables after these additions.

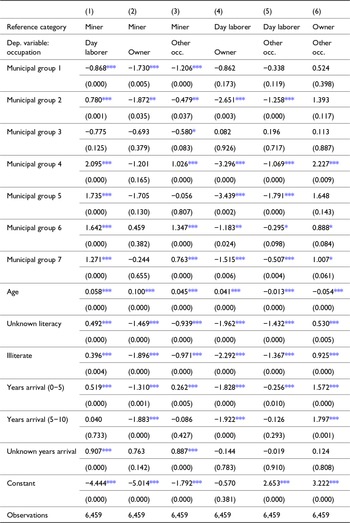

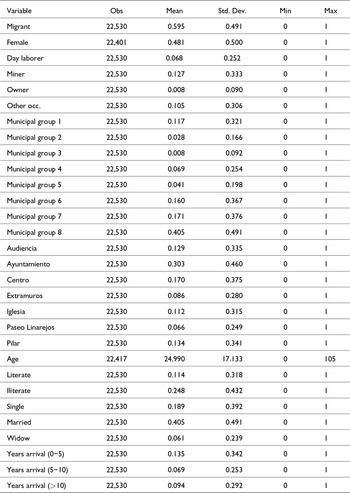

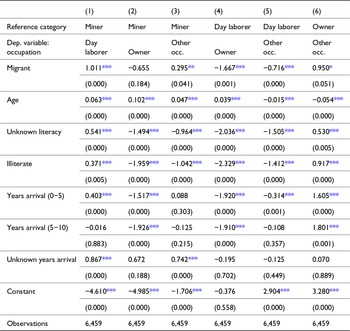

To study the effects of the migration chains in greater depth, we have analyzed the evidence of their functioning in two of the most frequent areas of cooperation: the transmission of information regarding employment opportunities and the search for accommodation (Equations 2 and 3). The relationship between the occupation of the individuals and their place of origin is analyzed in the models in Table 4. On this occasion, the database used includes individualized information on all the inhabitants of Linares in 1873. The calculations were made using data relating to males over the age of 15. The statistical method used is multinomial logistic regression, with the dependent variable being the individual’s occupation (miner, day laborer or owner).

Table 4. Labor specialization according to the municipal group of origin. Multinomial logistic regression

Notes: Males aged 15 years or older. See Table A5 for descriptive statistics.

Robust p values in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

where Occui is the binary variable for individual i. In the first model, the variable takes the value of 1 if the individual is a miner and 0 otherwise; in the second model, 1 if he is a day laborer and 0 otherwise; and in the third 1 if he is an owner and 0 otherwise. On the right, the variable associated with the migration chain functioning is Mungroupi and it refers to the municipal group of origin of the individual. To control for other confounding effects, several control variables are included. Agei is included to control for the possible relation between the individual years and the occupation. Some occupations are associated with older people. It is also possible that the job opportunities available to individuals of each generation in their youth influence their skills and determine their occupation over the years. Literacy (Liti) is introduced to control for the theoretically greater propensity of educated people to be owners or to be in certain occupations such as tradesmen, teachers or craftsmen, which are part of the “other occupations” category, rather than working as day laborers. Time since arrival (Yarrival i) is likely to influence the likelihood of holding certain occupations. More recent migrants are likely to be in lower-paid jobs, such as day laborers, and it is reasonable to assume that if there are opportunities for social mobility, some migrants may, over time, achieve a better position, such as owner or “other occupations.” Marital status has also been included in additional controls.

The results of the models presented in Tables 4 and A6 reveal significant differences in the occupation of migrant and nonmigrant males and among migrants based on their municipal group of origin. The category miner has been used as a reference category in the first three models. In Models 4 and 5, the occupational reference category is day laborer, and in the sixth, it is owner. The propensity to work as a miner was particularly high for individuals from municipal group G1. Individuals from the G3 are also more likely to be miners and less likely to be day laborers, owners, or in other occupations, although the difference is only statistically significant for the last category. Meanwhile, those from municipal group G2, G4, G6, and G7 had a higher propensity to work as day laborers than those born in Linares. The coefficients of the models in which the probability of being an owner is analyzed directly (Models 2, 4) or as a reference category (Model 6) reflect how, in general, it was the natives of Linares who occupied this position.

As we saw previously, the higher propensity to work in one job or another depending on the municipal group of origin is probably related to the existence of migration chains that facilitated the incorporation of the migrants into certain job positions (Ahmad, Reference Ahmad2015; Cante, Reference Cante2007). In any event, we should take into account that it is more than possible that it is also related to the production specialization characteristics of the different territories of origin of the migrants. Specific tasks in the mines required previously acquired skills. In this respect, the experience accumulated in the place of origin by the miners from the Alpujarra in Almería and Granada (G-1) and from Almadén (G-3) together with the reduction in mining activity in these areas due to the exhaustion of certain deposits, must have constituted elements that promoted the migration of the population of these territories to Linares (Martínez Soto et al., Reference Martínez Soto, Pérez De Perceval Verde and Sánchez Picón2008).Footnote 9

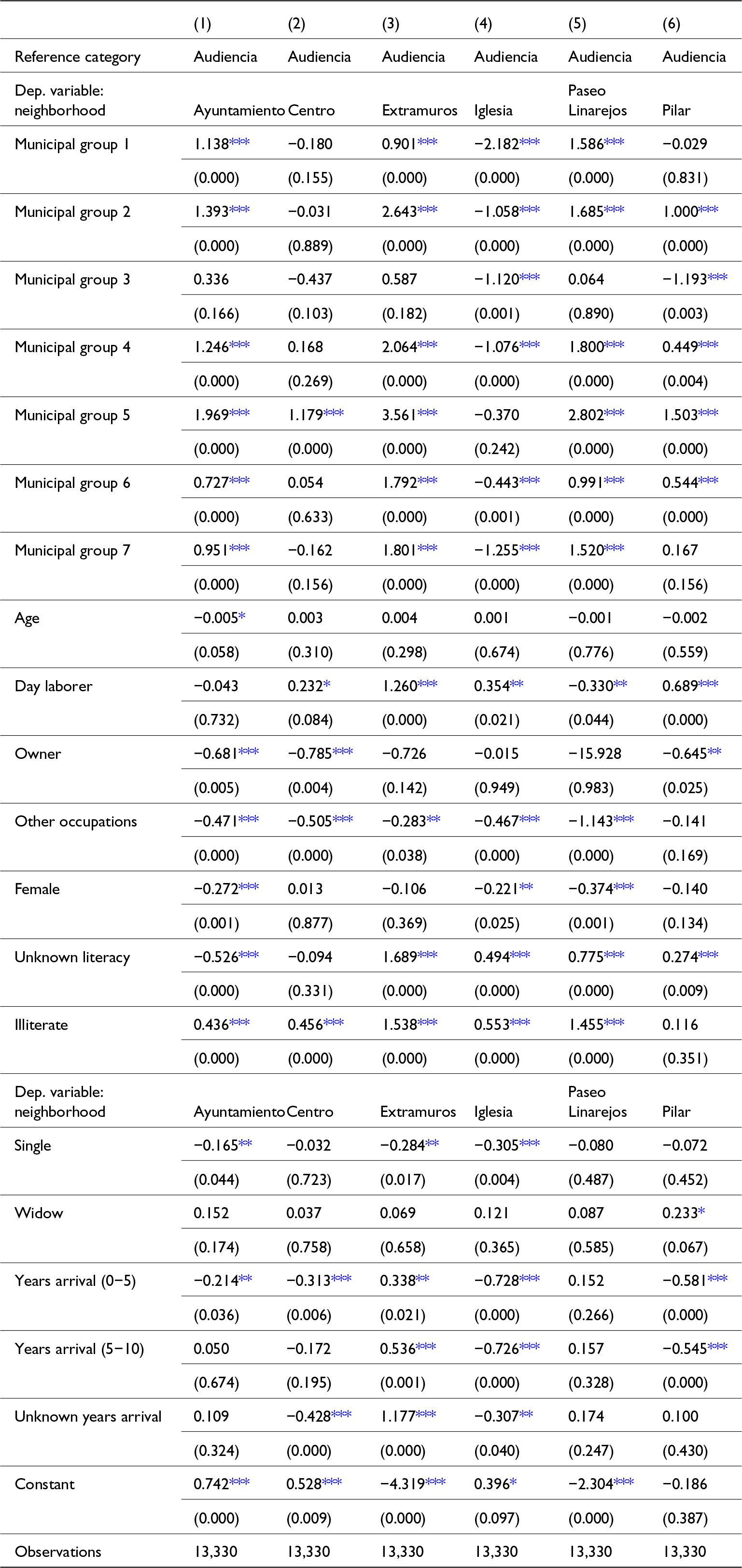

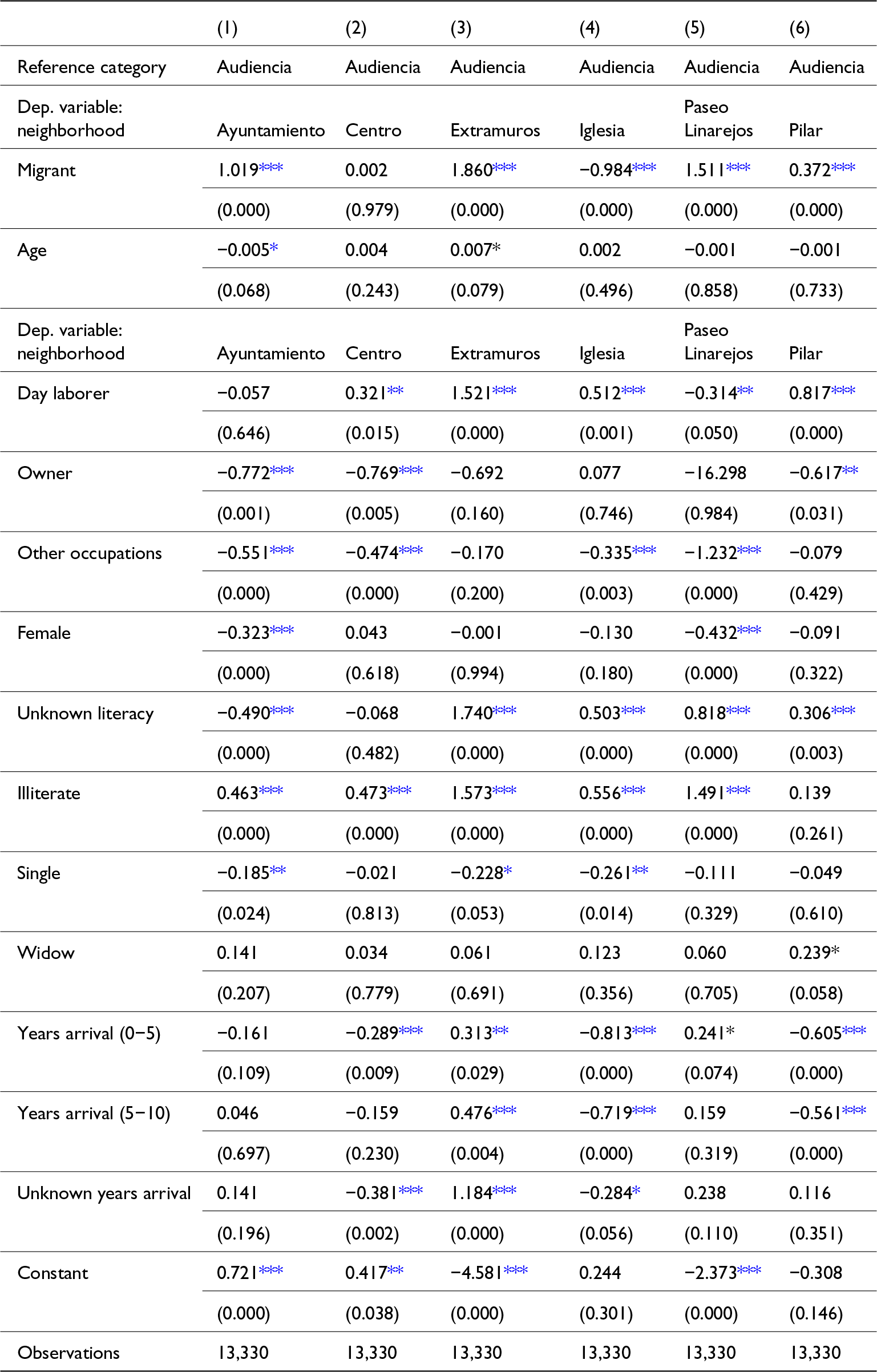

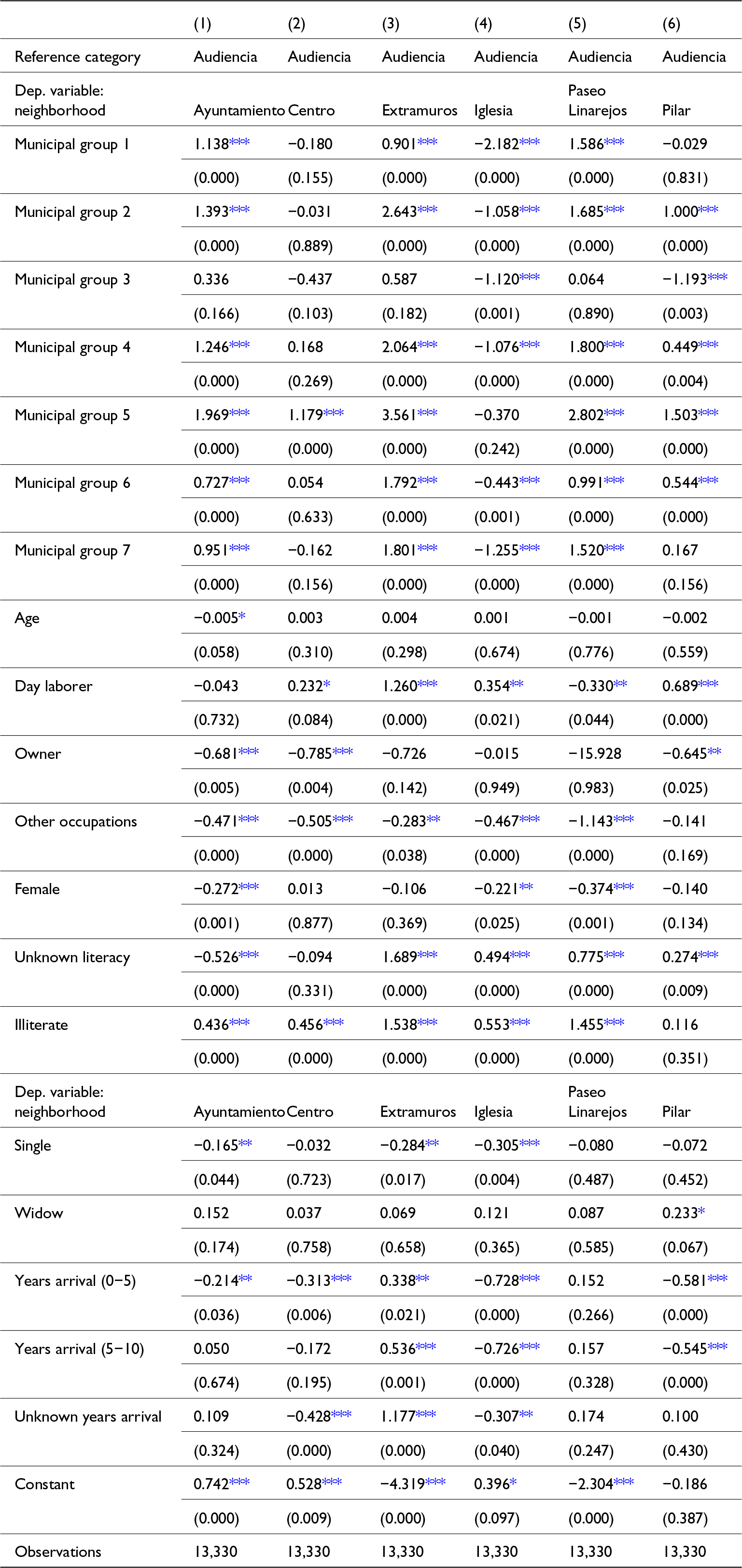

The models in Tables 5 and A7 analyze the effect of the place of origin of the individuals on the location of their homes in Linares. In this case, the database with the personal information of each individual has been used, but this time taking into account both the men and women over the age of 15. We have opted to exclude those under the age of 15, given that we consider that this could bias the estimates as the children of migrants would appear as natives of Linares, but, however, the decision regarding the location of residence would have been taken by their parents. In these models, the dependent variable is the neighborhood of residence (Resi) and the explanatory variable is the municipal group of origin of the individuals (Mungroupi). In order to isolate the effect of region of origin in determining employment at destination, we have included a number of control variables: age, occupation (Occui), sex (SexI), being literate or not (Liti), time since arrival (Yarrivali), and marital status (MSi).

\begin{align}Re{s_i} & = \,\alpha + \,{\beta _1}Mungrou{p_i} + \,{\beta _2}Ag{e_i} + {\beta _3}Oc{u_i} + \,{\beta _4}Se{x_i} + \,{\beta _5}Li{t_i} \nonumber\\

& \quad + {\beta _6}Yarriva{l_i} + {\beta _7}M{S_i} + \,\varepsilon \end{align}

\begin{align}Re{s_i} & = \,\alpha + \,{\beta _1}Mungrou{p_i} + \,{\beta _2}Ag{e_i} + {\beta _3}Oc{u_i} + \,{\beta _4}Se{x_i} + \,{\beta _5}Li{t_i} \nonumber\\

& \quad + {\beta _6}Yarriva{l_i} + {\beta _7}M{S_i} + \,\varepsilon \end{align}Table 5. Spatial distribution of the population in Linares according to the municipal group of origin. Multinomial logistic regression

Notes: Men and women aged 15 years or older. See Table A5 for descriptive statistics.

Robust p values in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

A common feature of the distribution of the population in cities is that in specific neighborhoods there is a higher concentration of the migrant population than in others. The models included in Table A7 reflect significant differences in the location of the houses of migrants compared to those of natives. In comparison to the Audiencia neighborhood, migrants demonstrate a higher propensity to reside in the following districts: Ayuntamiento, Extramuros, Paseo Linarejos, and Pilar. Conversely, they exhibit a lower propensity to live in the Iglesia neighborhood. In this case, the distinction between migrants and those born in Linares is not as pronounced as the variation observed between migrants according to their place of origin. This could be indicative of the functioning of migration chains (Diaz Quidiello et al., Reference Diaz Quidiello, Olmedo and Clavero2009).

The results of these models confirm that the place of origin significantly influenced the location of the residence in Linares. Furthermore, although there are common characteristics that are shared by migrants and that differentiate them from the native population, an analysis of the different groups of migrants reveals that there are also significant differences between them. The varying inclination to reside in the Pilar neighborhood exemplifies this phenomenon. Those hailing from the “Mountains of Granada and Almería” (G-1) exhibit no discernible distinction from those originating from Linares. Conversely, those originating from Almadén (G-3) evince a heightened propensity to inhabit this neighborhood, while those from the plateaus of the North of Almería (G-2) demonstrate a markedly diminished proclivity to do so. With respect to the control variables included, the different occupational categories are significant. In this case, the reference category is mining. The effect of the occupation on the determination of the location of the home is notable. For example, we can observe how the day laborers had more possibilities of living in the Extramuros or Pilar neighborhoods than the miners. Similarly, the remaining control variables are also significant in many cases.

However, while controlling for the rest of the variables, the effect observed of the area of origin is greater in many cases, with significant differences in the value of the coefficients related to each of the municipal groups.Footnote 10 These results coincide with the effect associated with the migration chains, whereby the migration chain acts as an element that facilitates the search for accommodation in the destination (Ryan, Reference Ryan2011; Van Meeteren and Pereira, Reference Van Meeteren and Pereira2018) and from which a spatial concentration of the members of a migration chains in specific neighborhoods or streets is derived.

6. Conclusions

During the mining boom, Linares played a prominent role in one of the most important migratory phenomena in Spain in the second half of the nineteenth century. The results obtained show the usefulness of the migration chains approach to analyzing internal migrations in the preindustrial era and the early phases of industrialization. Some classic variables indicated in the literature, such as distance or municipal size, are shown to be significant determinants but are insufficient to explain the migration flows observed.

While nearby territories made a residual contribution to the migration flows to Linares (provinces of Seville, Cordoba, and other territories of southern Andalusia), the south-east of Spain (Granada, Almería, Murcia) and in some cases places even further away from Linares made larger contributions to the flows. Other districts with a mining tradition also stand out, such as Almadén. Therefore, the migratory movements described differ partly from the classic migration from the country to the city or from the agricultural sector to the industrial sector. In this case, this is largely explained by a displacement from the former mining areas to Linares.

This shows how other factors, such as the prior acquisition of professional competences (Beltrán Tapia and de Miguel Salanova, Reference Beltrán Tapia and de Miguel Salanova2017; Droller, Reference Droller2018; Juif and Quiroga, Reference Juif and Quiroga2019) and the existence of migration chains, are key elements in the phenomenon that is the object of this study (Gaete Quezada and Rodríguez Sumaza, Reference Gaete Quezada and Rodríguez Sumaza2010; Santiago-Caballero, Reference Santiago-Caballero2021). The different cycles of mining experienced by the various mining areas, derived both from the exhaustion of deposits and the differential variation in the price of the different materials, seem to be a transcendental factor. This would encourage workers to emigrate, using the skills they had acquired. In this respect, the information that flowed through the migration chains facilitated the movements of workers from areas where the mining activity was declining, such as the Almeria and Granada mountains, to the dynamic mining industry of Linares in the period studied.

The analyses suggest that when examining migration chains, it is recommended to utilize a scale of observation smaller than the administrative provincial level. Descending to the municipal level allows for a more precise observation of the intensity of their dimensions. From this perspective, it becomes evident how the presence of pioneers from a certain place had a positive influence on the subsequent migration flows. A positive relationship has also been found between the greater migration intensity to Linares from the population of a certain municipality and that of the nearby towns. Moreover, the study of migrations based on microdata has allowed us to confirm the functioning of migration chains by observing their characteristics and effects. In this respect, it has been observed that the spatial distribution of the migrant population in the destination city and their occupations were not random, but clearly related to the places of origin. This result reflects the role played by migration chains in enabling information and reducing the costs associated with the search for job opportunities, accommodation, and housing.

Finally, this approach raises several questions from a dynamic temporal perspective for a future research agenda. In the past, the role of pioneers in forming migratory networks appears to have been pivotal. As we move forward in time, it is crucial to consider the duration of the network and the potential for its dissolution due to the integration of immigrants into the destination community. This integration is likely to occur relatively quickly in internal migrations where minor cultural differences promote integration, for example, through the marriage market. This phenomenon should be reflected in a dissipation of the concentration of migrants in different neighborhoods according to their origin, as well as a reduction of occupational differences between inhabitants.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editor and the anonymous referees for their constructive and valuable feedback, which has significantly improved this article. Additionally, we extend our thanks to participants of the seminar held at the Universidad de Murcia, the ADEH seminar at the University of Zaragoza, and the XIX WEHC in Paris, whose insightful comments and suggestions greatly enriched our research.

This research was supported by projects PID2022-137302NB-C32 and PGC2018-097817-B-C32, funded by the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities of the Spanish Government. Additional support was provided by the PPIT-UAL, Junta de Andalucía-ERDF 2021-2027. Objective RSO1.1. Programme: 54.A. Funding for open access charge: Universidad de Almería (Spain) / CBUA. During the development of this study, María Carmen Pérez Artés benefited from the Margarita Salas Fellowship program financed by the European Union-NextGenerationEU.

Appendix

Figure A1. Map of the city of Linares in 1876.

Table A1. Evolution of the population of Linares

Source: Individual population registers 1836, 1840 and 1850, 1857 Archivo Municipal de Linares (AHML) and Spanish population census 1860 1877, 1887, 1897, 1900, 1910, and 1920 (INE).

AAGR, average annual growth rate.

Table A2. Distribution of the population by sex and occupation according to the province of origin

Source: Own elaboration based on the data of the population register of Linares 1873.

a The calculations of occupations have been made using the data referring to men over the age of 15 with an occupation. Data on occupations in % except the last row with absolute values.

Table A4. Determining factors of migration to Linares in the years prior to 1873. OLS model

Robust p values in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table A5. Descriptive statistic database

Table A6. Results of the econometric models on the occupational distribution of the population in Linares according to migrants and nonmigrants. Multinomial logistic regression

Robust p values in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Table A7. Results of the econometric models on the spatial distribution of the population in Linares according to migrants and nonmigrants. Multinomial logistic regression

Robust p values in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.