Introduction: Church, state, and religious law over time

The relationship between religion and the state remains one of the most significant and complex issues in contemporary societies. In mainstream liberal theories, religion is often treated as a distorting variable in ethical practice, reducing decision-making to a fixed calculus that bypasses the uncertainties of lived experience (Nussbaum Reference Nussbaum2004, Reference Nussbaum2012). According to Rawls and Habermas, laws and public policies must therefore be justified in neutral terms, namely reasons that people with conflicting worldviews could reasonably accept, rather than religious ones (Habermas Reference Habermas2008; Sikka Reference Sikka2016; Yates Reference Yates2007). While Western democracies frequently present themselves as adhering to models of church-state separation, religious legacies continue to shape societal practices and policies, even in highly secular contexts. This persistence can be explained by the institutional dynamics of path dependency and increasing returns, whereby early patterns become entrenched and self-reinforced (Collier et al. Reference Collier and Collier1991; Pierson Reference Pierson2004).

Specifically, this study investigates, under what conditions does religious law, rooted in state establishment, decline in democracies? We argue that when (1) state founders or political elites intentionally refrain from embedding religious arrangements within state institutions, (2) the state apparatus enforces a constitutionalized and explicit prohibition against government-sanctioned religion, and (3) legal justifications shift from religious to secular rationale to maintain their justifiable constitutionality, then reliance on religious law within the state diminishes. However, due to institutional path dependence, laws initially rooted in religious arrangements/traditions may persist but are increasingly framed in secular terms, aligning with the broader secularization of modern Western societies, regardless of the extent of separation between religion and state. Hence, the religious influence and objectives of these laws endure despite the secular disguise.

To exemplify this phenomenon and uncover this causal mechanism, we use a single case study design of a democratic state that holds a “light secularism” design, namely the United States. In the United States, the separation of religion and state is understood as the exclusion of the state from religious affairs and the corresponding exclusion of religion from state affairs (Bhargava Reference Bhargava2014). The concept of “light secularism” refers to a moderate approach to this separation, where the government remains neutral toward religion while allowing certain public expressions of faith. This model accommodates religious practices and symbols in the public sphere (Lewis Reference Lewis2014) as long as no single religion is privileged. It is particularly relevant in the United States, where a balance is maintained between religious freedom and the non-establishment principle. McConnell (Reference McConnell1992) describes this as an “accommodationist” approach, arguing that the United States’ model of religious freedom, particularly the balance between the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause, creates a unique environment in which the state acknowledges religion without establishing it. Casanova (Reference Casanova1994) supports this view, asserting that religion can remain influential in public life while respecting secular boundaries. Further, Monsma and Soper (Reference Monsma and Christopher Soper2009) and Sullivan (Reference Sullivan2005) demonstrate how the United States fits within a “light secularism” framework by balancing secular governance with public religion and religious accommodations.

This study contributes to understanding the American secular framework by examining Blue laws, which, despite the country’s firm tradition of church-state separation, are rooted in the Christian belief that Sunday is a holy day reserved for rest and worship. Advocated by Sabbatarians from colonial times through the late 20th century, many Blue laws have been gradually repealed over the past century (Cohen-Zada and Sander Reference Cohen-Zada and Sander2011; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lee Reference Lee2013). However, some remain in effect, persisting across states with diverse political and geographical profiles. Given the United States’ tradition of religious freedom, it is crucial to explore how these laws became embedded in American legislation and shaped public attitudes toward Sunday as a day of rest, even as they coexisted with secularist ideologies.

Indeed, the United States serves as a valuable case study because it (1) maintains a legal-institutional separation of church and state, yet (2) possesses a strong religious culture deeply rooted in both its legal arrangements and society; (3) offers detailed, albeit sometimes difficult to retrieve, legal records that are accessible; and (4) exhibits policy diversity across its states, allowing for comparative analysis among them. These factors combined enable us to observe how religious laws have evolved over time, while religious remnants persist stubbornly within the legal codes of the fifty states. In this sense, the United States is particularly instructive because it deviates from the expected cross-case pattern in which secular democracies are thought to display a steady decline in religious influence. By examining how religiously grounded laws in the United States have been reframed in secular terms while still retaining religious traces, we can uncover the mechanisms underlying this process of transformation.

Theory-wise, adopting an institutional perspective, we innovate by highlighting that in democratic systems that formally aim to separate religion and state yet possess a strong religious background in their pre-state or early statehood years, religious remnants are likely to persist in legislation through the historical institutionalist mechanisms of path dependency and increasing returns. Consequently, enduring gaps may emerge between existing legal-institutional arrangements and public preferences in Western secular societies (Golan-Nadir Reference Golan-Nadir2022). In the American case, this pronounced pre-state religious influence renders it a deviant case study, where religion is highly evident in legislation, even when using secular terminology. Furthermore, this study illustrates that religion may serve as a paradigmatic case of an all-encompassing ideology that can hinder legislative change, much like other ideologies such as liberalism or socialism.

By employing the process tracing technique (Collier Reference Collier2011) to analyze religion-based legislation from the nation’s founding to the present, this study utilizes archival reviews of primary and secondary sources to examine how Blue laws evolved, particularly at critical junctures when they were modified or challenged. Our analysis aims to clarify the institutional legacies that interact with political and religious elements of the United States’ legal system in regard to the ostensibly outdated Blue laws. This approach not only deepens our understanding of the American Blue laws but also contributes towards discussions in the field of political science and public policy regarding the impact and instances of enduring institutional resilience versus public will.

The historical institutionalist framework to study legislative persistence

From a New Institutionalist perspective, institutions are top-down structures composed of formal and informal rules that constrain and enable political behavior (North Reference North1990). They structure state-society relations across various domains (Farrell and Héritier Reference Farrell and Héritier2003; Hall Reference Hall1986; Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Victoria Murillo2009; Moe Reference Moe2005; North Reference North1990; Streeck and Thelen Reference Streeck and Thelen2005; Thelen and Steinmo Reference Thelen, Steinmo, Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992, Reference Thelen and Steinmo2014). Institutions, hence, reduce transaction costs by embedding rational decision-making frameworks (Levi Reference Levi, Lichbach and Zuckerman2009, 29).

Within the New Institutionalist framework, historical institutionalism emphasizes that initial policy choices shape institutional trajectories long into the future (Hall and Taylor Reference Hall and Taylor1996; Lecours Reference Lecours and Lecours2005). Once institutional patterns are established, self-reinforcing processes make policy change difficult (King Reference King1995; Pierson Reference Pierson2000; Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992). Institutional evolution follows extended periods of path dependency, interrupted by critical junctures that redefine policy objectives, establish new priorities, and form new political and administrative coalitions (Capoccia and Kelemen Reference Capoccia and Daniel Kelemen2007; Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1991; Greif and Laitin Reference Greif and Laitin2004; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2000, Reference Mahoney2001, Reference Mahoney, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003; North Reference North1990; Pierson Reference Pierson2004; Pierson and Skocpol Reference Pierson, Skocpol, Katznelson and Milner2002; Rixen and Viola Reference Rixen and Anne Viola2015; Steinmo et al. Reference Steinmo, Thelen and Longstreth1992). Decisions made during these junctures lock in specific trajectories, generating self-reinforcing processes (Büthe Reference Büthe2002; Collier and Collier Reference Collier and Collier1991; Mahoney Reference Mahoney2000; Peters et al. Reference Peters, Pierre and King2005; Pierson Reference Pierson2000, Reference Pierson2004). Increasing returns further entrench institutional designs over time (Pierson Reference Pierson2004, 135). In state-religion relations, foundational policy choices during critical junctures determine religion’s role in the public sphere. These arrangements tend to persist unless another critical juncture disrupts them, enabling institutional change (Rixen and Viola Reference Rixen and Anne Viola2015). Within the institutional framework, religion is viewed as a classic example of a legal-institutional arrangement, as it often assumes an institutional form (Gill Reference Gill2001).

The varying relations between religion and state

The role of religion in relation to the state and society is shaped by the legal, historical, and political contexts in which these entities operate. As these contexts evolve, so too does religion’s role (Lord Reference Lord2008). Structurally, religion often takes an institutional form (Gill Reference Gill2001; Kaya Reference Kaya2019), shaping its position within civil society, political society, and governmental arenas (Casanova Reference Casanova1994; Stepan Reference Stepan1988). Focusing on the latter, Alfred Stepan’s Twin Tolerations (Reference Stepan2000) posits that religious freedom prohibits both religious imposition on democracy and state-enforced religion. While religious norms may influence public policy (Gill Reference Gill2001), elected officials in democratic states must retain sufficient autonomy to formulate constitutional policies free from interference by unelected religious authorities (Driessen Reference Driessen2010).

State support for religion can lead to its bureaucratization, wherein religious institutions, such as religious departments and courts, become integrated into governmental structures (Finke Reference Finke2013; Fox Reference Fox2021; Golan-Nadir and Christensen Reference Golan-Nadir and Christensen2023; Golan-Nadir et al. Reference Golan-Nadir, Bloomberg and Baranes2025; Grim and Finke Reference Grim and Finke2010) and are enforced through government sanctions (Stark Reference Stark1992). Economically, religious regimes vary: some states control religious markets, dictating expenditures, while others allow independent markets. For the government, this trade-off is clear: state control allows the state to tailor religious spending to align its objectives in a monopolized manner. In contrast, an independent religious market caters to the preferences of citizens (Coşgel and Miceli Reference Coşgel and Miceli2009).

The state-religion relationship can be understood as a continuum ranging from full integration of religion into state institutions to complete separation (Fergusson Reference Fergusson2004; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2011). Each point along this continuum constitutes a religious regime, a configuration reflecting the degree of religious freedom, the state’s reliance on religion for legitimacy, and the interaction between religious and political authorities (Koster and Meijers Reference Koster and Meijers1991; Ongaro and Tantardini Reference Ongaro and Tantardini2023b, Reference Ongaro and Tantardini2023c; Van Dam and Van Trigt Reference Van Dam and Van Trigt2015). In democratic contexts, three main types emerge: liberalism, ensuring religious freedom; Caesarism, where the state regulates religion; and identification, where a state religion is institutionally embedded (Ongaro and Tantardini Reference Ongaro and Tantardini2023a, b, c).

In cases of religious monopolies, societal dissatisfaction is more likely because diverse needs cannot be met by a single provider (Berger and Hefner Reference Berger and Hefner2003; Gill and Jelen Reference Gill, Jelen and Ted2002; Pollack and Olson Reference Pollack and Olson2012). The economics of religion emphasizes the crucial role of government regulations in shaping religious trends, participation, and the extent to which individuals identify as non-religious (Gill and Lundsgaarde Reference Gill and Lundsgaarde2004; Iannaccone et al. Reference Iannaccone, Finke and Stark1997). Religious preferences are inherently pluralistic, even in homogeneous societies, as no single religion can satisfy everyone (Gill Reference Gill2005; Stark Reference Stark1992). Research shows that pluralistic religious environments foster greater vibrancy and participation than state-supported monopolies, offering members valued goods and addressing societal dissatisfaction (Gill Reference Gill1999, Reference Gill2021; Iannaccone Reference Iannaccone1991, Reference Iannaccone1992, Reference Iannaccone1994). These theories assume individuals treat religion as a choice, changing preferences over time (Iannaccone Reference Iannaccone1992, Reference Iannaccone1998). Religion thus exemplifies an institutional barrier to law and policy modification, similar to other entrenched structures.

Religion and state relations in the United States

The United States has maintained a legal separation between government and religion since its founding (Corbett et al. Reference Corbett, Corbett-Hemeyer and Wilson2014; Owen Reference Owen2015). The First Amendment’s Establishment Clause states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” creating a constitutional barrier between church and state (Galloway Reference Galloway1989; Laycock Reference Laycock1993). However, this does not imply that the founders envisioned a secular nation. Thomas Jefferson’s reference to a “wall of separation” coexisted with the belief that American society should be religious and moral (Jefferson Reference Jefferson1802; Owen Reference Owen2015; Salton Reference Salton2013). John Adams similarly stated that the Constitution was designed for “a moral and religious people” (National Archives n.d.). Alexis de Tocqueville observed that in the United States, religion (Christianity) was intertwined with liberty, not through direct mixing but through their mutual reinforcement (de Tocqueville Reference de Tocqueville1986, 335). The founders sought a state where individuals could worship freely, without government interference (Salton Reference Salton2013; Shearer Reference Shearer1943).

Despite the Establishment Clause, Judeo-Christian values have been deeply embedded in American political culture. Every state constitution references God or a supreme being, and the phrase “the year of our Lord” appears in the United States Constitution (Sandstrom Reference Sandstrom2017). Religious references, such as the national motto “In God We Trust” and public officials swearing oaths on the Bible, reinforce the perception of the United States as a highly religious democracy (Jones Reference Jones1989; Lacorne Reference Lacorne2011). Many of these traditions emerged during the Civil War and the Cold War to reinforce national unity and differentiate the country from the secular Soviet Union (Kirby Reference Kirby and Kirby2003; Lacorne Reference Lacorne2011). However, the roots of American religiosity trace back to the Puritan settlements of the 1600s and the First Great Awakening of 1734 (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987). The Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) influenced the Bill of Rights, granting autonomy to the Church and enumerating rights based on religious principles (Berman Reference Berman1983).

Although religion is viewed as a private matter, American law has often reflected Judeo-Christian ideals. The Declaration of Independence references the “laws of Nature and Nature’s God,” and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas affirmed in Zorach v. Clauson, 343 U.S. 306 (1952), that “We are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.” Over time, secularization in the United States emerged from Enlightenment ideals emphasizing individualism, rationalism, and nationalism, with liberal democracy itself becoming a form of secular religion (Berman Reference Berman1983). While figures like Jefferson promoted this shift, Americans, influenced by Adams and other founders, long resisted a total separation of church and state (Lacorne Reference Lacorne2011; Salton Reference Salton2013; Shearer Reference Shearer1943; Stein Reference Stein2000). This belief in moral governance inspired movements like Prohibition, driven by religious groups advocating for national purity (Fanning Reference Fanning2023), and helps explain Owen’s (Reference Owen2015) statement that the Supreme Court of the United States, and liberal theory in America for that matter, are neither secular nor religious, but rather a type of neutral institution between the two.

Understanding this historical dynamic is key to assessing the role of religion in the American democracy. The founders debated the extent of religion’s influence on politics, balancing classical traditions of moral governance with Lockean principles of protecting religious freedom (Davis Reference Davis2000). They envisioned a system where morality was shaped in the private sphere, with the government ensuring religious liberties without imposing a state-sanctioned moral code (Davis Reference Davis2000; Lacorne Reference Lacorne2011; Salton Reference Salton2013). This principle underpinned laws based on religious ideals, namely the Blue laws.

The Blue laws

The first Blue laws (also called “Sunday laws” or “closing laws”) enforced within the territory of the modern-day United States were those adopted by the Jamestown colony in the 1610s, after the first Jamestown Legislative Assembly (Burgesses) voted to mandate church attendance on Sundays (Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; Lovenheim and Steefel Reference Lovenheim and Steefel2011; Lutz Reference Lutz1998). As such, these Blue laws have a religious origin, having been created through the union of church and state in the American colonies and aimed at restricting trade, travel, work, and forms of pleasure on Sunday (Cohen-Zada and Sander Reference Cohen-Zada and Sander2011; Gavison and Perez Reference Gavison, Perez, Cane, Evans and Robinson2009; Han et al. Reference Han, Branas and MacDonald2016; Hyman Reference Hyman1973; Meany et al. Reference Meany, Berning, Smith and Rejesus2018; Teupe Reference Teupe2019). The different colonies in North America quickly adopted legislation to ensure that the Sabbath remained a day of holiness, basing their wording on the English restrictive Sunday laws passed by King Charles II (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Gruber and Hungerman2016; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007).

After the American Revolution and the establishment of the United States, many states that adopted Blue laws used nearly verbatim the original religious laws from the colonial period, seeing little change despite the enactment of the First Amendment (Hyman Reference Hyman1973; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007). These laws continued to be promoted by Sabbatarians in the United States until the late 19th century and even today remain present in some state legislation (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber, Gruber and Hungerman2016; Humphreys Reference Humphreys2016).

Legally, Blue laws were deemed constitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420 (1961),Footnote 1 despite being based on and originally designed for religious purposes; they were found to serve secular goals of “health, safety, need for rest and common day of relaxation…” The Court further declared that “the cause is irrelevant; the fact exists” (Carroll Reference Carroll1967; Cohen-Zada and Sander Reference Cohen-Zada and Sander2011; Herlocker Reference Herlocker1962; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lee Reference Lee2013; Lovenheim and Steefel Reference Lovenheim and Steefel2011; McGrath Reference McGrath1960; Raucher Reference Raucher1994, 30). Notably, McGowan v. Maryland (1961) not only deemed Blue laws constitutional in Maryland, thereby setting precedent for other states, but also realigned their justification from religious to secular rationale, as states needed to pass the “rational basis test” to prove their Blue laws had secular justifications (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987). The Supreme Court provided the secular rationale of promoting a uniform day of rest for all citizens, allowing for societal well-being by providing time for family, recreation, and relaxation. Three additional major Blue law cases during this period were Braunfeld v. Brown, 366 U.S. 599 (1961), Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley, 366 U.S. 582 (1961), and Gallagher v. Crown Kosher Supermarket, 366 U.S. 617 (1961) (Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007). In each of these cases, the Supreme Court upheld Blue laws on secular grounds, legitimizing secular justifications in two additional states, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, and establishing precedent for using secular rationale as a defense for state Blue laws. Notably, much like the motto “In God We Trust,” which was adopted as an anti-secular and anti-communist tool to unify the United States during the Cold War, perhaps the religious origins and remaining aspects of Blue laws influenced the Supreme Court to preserve them under new wording rather than abolish them, though this remains speculative (Kirby Reference Kirby and Kirby2003; Lacorne Reference Lacorne2011).

Socio-economic trends also aligned with the changes in the law’s justification. In and around the 1960s, the increasing secularization of the United States, the rising demand for weekend shopping driven by growth in suburban living after World War II, the growth of progressive women in the workforce, an increase in religious pluralism, the rise of radical liberalism (critical of religion), and the decline of blue-collar unionism that had supported many Blue laws all contributed to eroding Sunday laws, making them far less prominent today than they were decades ago (Eisgruber Reference Eisgruber2006; Gann and Duignan Reference Gann and Duignan1995; Herlocker Reference Herlocker1962; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lindsay Reference Lindsay2023; Melton Reference Melton2001; Voas and Chaves Reference Voas and Chaves2016). Arguably, the changing times and atmosphere of progressive reform during the post-World War II era helped influence the Supreme Court when deciding McGowan v. Maryland (1961) and shaping the future of Blue law justification in the United States. Altogether, shifting societal attitudes toward work, alcohol, and religion; the inconsistent and exemption-riddled enforcement of Blue laws; the continuing constitutional challenges to their validity; and the technological innovations that render them obsolete and inefficient have all contributed to the recent trend of repealing Blue laws at the state level (Burda and Weil Reference Burda and Weil2004; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Robbins Reference Robbins2022). Yet, this is not to say that Blue laws lacked defenders. Special interest groups such as Southern Baptists, dominant politicians in state legislatures, and small family-owned businesses have fought to uphold some level of Blue laws despite studies revealing possible neutral or negative effects of the laws on crime, education, and the economy (Connolly et al. Reference Connolly, Graziano, McDonnell and Steinbach2023; Han et al. Reference Han, Branas and MacDonald2016; Heaton Reference Heaton2012; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lee Reference Lee2013).

While most religion-based pre-state Blue laws are no longer enforced, quite a few remain embedded in various states’ legal codes (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Robbins Reference Robbins2022). An examination of the fifty states’ Blue laws shows that today, most active Blue laws, or prohibitions and limitations on Sunday activities, fall under three main categories: alcohol sales, car sales, and hunting, with additional miscellaneous restrictions (e.g., bans on professional sports, prohibitions on the sale of electronics, clothing, and furniture, all forms of non-essential or entertainment work, and private lawn watering on Sunday) (Azagba et al. Reference Azagba, Shan, Ebling, Wolfson, Hall and Chaloupka2022; Gottschall Reference Gottschall2013; Han et al. Reference Han, Branas and MacDonald2016; Herlocker Reference Herlocker1962; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; Lovenheim and Steefel Reference Lovenheim and Steefel2011; Meany et al. Reference Meany, Berning, Smith and Rejesus2018; Yörük Reference Yörük2014). In line with McGowan v. Maryland (1961), most of these laws are justified through secular rationale rather than religious grounds. However, several contradictions arise. First, their origins are religious, with many state statutes referencing Sunday as “The Lord’s Day” or “The Sabbath.” Second, their arbitrary enforcement across states, businesses, and restricted products undermines any tangible public benefit. Third, economic comparisons show no clear advantage for citizen well-being in states with Blue laws (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; McNiel and Yu Reference McNiel and Yu1989; Teupe Reference Teupe2019). These elements sustain the ongoing debate over Blue laws.

The debate over Blue laws: full repeal or secularization of rationale

The debate over Blue laws has been most clearly articulated through litigation. In McGowan v. Maryland (1961), John M. Jones Jr., Maryland’s Special Assistant Attorney General, rejected claims of religious coercion, insisting that “this is hardly a law establishing a religion. We think if anything it encourages activities which are not ordinarily associated with the Christian Sunday or any other religious observance.” He further argued that “there must be an accommodation between religion and the civil regulations, that always happens when you have a civil society.” The challengers, by contrast, maintained that Sunday restrictions privileged Christianity, creating economic inequities for Sabbatarians: “because there is a Sunday law which prohibits retail activities, a Sabbatarian… is in a position where he sells four and a half days a week whereas the non-Sabbatarian sells six.” The Court upheld the statute, concluding that while Blue laws had religious origins, their contemporary justification rested on secular goals of “health, safety, recreation, and general well-being” (Gavison and Perez Reference Gavison, Perez, Cane, Evans and Robinson2009). Subsequent cases echoed this rationale. In State v. Rogers, 105 N.H. 366 (1964), the New Hampshire court found that the law aimed “not to coerce religious observance of the Lord’s Day but to safeguard and improve the health, safety, recreation and general well-being of our citizens.” Similarly, in Vornado, Inc. v. Hyland, 77 N.J. 347 (1978), the New Jersey Supreme Court ruled that “the judiciary should not attempt to impose its own concept of what is socially desirable,” leaving Sunday closing to legislative discretion.

The opposing side of the debate has also been forcefully expressed in cases that struck down Blue laws. In County of Spokane v. Valu-Mart Inc., 69 Wn.2d 712 (1966), the Washington Supreme Court invalidated Sunday sales restrictions, declaring that “an ordinance which leaves in operation all of the other departments in the store [while prohibiting specific goods] is not reasonably necessary and appropriate… The ordinance is thus an excessive and invalid exercise of the police power and void.” In Skag-Way Department Stores, Inc. v. City of Omaha, 140 N.W.2d 28 (1966), the Nebraska court acknowledged that “early cases… sustained Sunday closing on the theory that it promoted the health, peace, safety, and good order of society,” but concluded that “We fail to see… how the Sunday closing ordinances before us have any relation to public safety, health, morals, or public welfare.” Likewise, in Kroger Co. v. O’Hara Tp., 481 Pa. 101 (1978), the Pennsylvania Supreme Court struck down Sunday restrictions, concluding that “The objective of providing a uniform day of rest and recreation for all citizens of Pennsylvania is… undermined by the exception which gives to some a right to open their business and sell prohibited merchandise on a Sunday if they close their business on some other day.”

The debate endures into the present, both in the courts and in public discourse. For example, the 2025 case of Paramus v. American Dream in New Jersey challenged Sunday sales restrictions on clothing (American Dream Megamall Sued 2025), while North Dakota repealed its retail Blue laws in 2019 after prolonged legislative disagreement (Peguero Reference Peguero2019; N.D. CENT. CODE § 12.1-30-01 (2023)). Scholarly research has further examined the consequences of repeal: Han et al. (Reference Han, Branas and MacDonald2016) found increased crime around Pennsylvania liquor stores, whereas Heaton (Reference Heaton2012), Connolly et al. (Reference Connolly, Graziano, McDonnell and Steinbach2023), and Lovenheim and Steefel (Reference Lovenheim and Steefel2011) reported mixed or negligible effects. Lee (Reference Lee2013) suggested broader social costs, showing that repeal may reduce educational attainment by increasing “time-competing diversions.” Taken together, these legal and scholarly examples demonstrate that the debate over Blue laws remains active, with arguments revolving around secular justifications, religious legacies, and broader societal impacts. While these issues have evolved over the years, it is clear that McGowan v. Maryland (1961), though providing a fundamental basis for subsequent Blue law decisions, did not offer a definitive resolution to the question of whether Blue laws belong in the American legal system (Robbins Reference Robbins2022).

As American society becomes more diverse and secular, the pressure to repeal or modify these laws continues to grow (Berman Reference Berman1983; Lee Reference Lee2013; Lindsay Reference Lindsay2023; Robbins Reference Robbins2022). In the ongoing debate surrounding the retention or repeal of Blue laws, various stakeholder groups present differing perspectives on the laws’ benefits and drawbacks. These groups include small and large business owners, employees, progressive advocates (such as women in the workforce), religious leaders, politicians, consumers, and special interest lobbyists, each arguing for their positions based on distinct concerns and priorities (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; McNiel and Yu Reference McNiel and Yu1989; Teupe Reference Teupe2019).

Indeed, shifting societal attitudes toward work, alcohol, and religion, combined with inconsistent enforcement, legal challenges, and technological workarounds, have contributed to the trend of repealing Blue laws (Robbins Reference Robbins2022; Teupe Reference Teupe2019). For example, since the 2000s, the rise of weekend brunch and daytime drinking has diminished support for alcohol bans (Robbins Reference Robbins2022). Additionally, the internet has allowed consumers to bypass restrictions through online purchases of alcohol and other items, disadvantaging brick-and-mortar businesses that remain closed due to Sunday bans (Robbins Reference Robbins2022; Teupe Reference Teupe2019). However, Blue laws have been justified both as worker protections and as moral restrictions, particularly on alcohol sales. Workers fear that without Blue laws, employers could coerce them into working Sundays under threat of job loss (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987). To address these concerns, some states repealing Sunday labor laws have included job security provisions. Nevertheless, the absence of Blue laws may still leave vulnerable workers at risk of exploitation and financial loss.

To influence Blue law legislation, these varied stakeholder groups focus on key factors including religious freedom, equal protection, vague wording that complicates enforcement, church membership and contributions, energy use, state funding for arts and recreation, labor participation, societal well-being (such as marriage, divorce, suicide, and crime rates), public health, economic activity per capita, and business size relative to employee counts (Herlocker Reference Herlocker1962; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; McGrath Reference McGrath1959, Reference McGrath1960, Reference McGrath1962; McNiel and Yu Reference McNiel and Yu1989; Meany et al. Reference Meany, Berning, Smith and Rejesus2018; Rogers Reference Rogers1979). In recent decades, pressure against Blue laws has intensified beyond the growth of a progressive workforce and increasing secularization. The 21st century has introduced new legal, social, economic, and technological challenges to their enforcement (Beard et al. Reference Beard, Ekelund, Ford, Gaskins and Tollison2013; Lindsay Reference Lindsay2023; Robbins Reference Robbins2022; Twenge et al. Reference Twenge, Exline, Grubbs, Sastry and Keith Campbell2015). Recent court cases, such as Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc., 573 U.S. 682 (2014), and state-level repeals of alcohol bans in Arkansas, Connecticut, Minnesota, and Washington, D.C., reflect this broader shift toward religious freedom and diversity as well as an increasingly secular legal landscape.

Despite the mounting societal forces against them, many Blue laws persist due to legislative inertia, religious advocacy, and concerns over worker exploitation, all supported by a “politically well-organized minority” protecting these laws (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987). However, Blue laws face growing pressure for repeal from non-Sunday observant voters and secular legislatures. This pressure has intensified as more states have enacted Religious Freedom Restoration Acts (RFRAs) following the Supreme Court’s ruling in City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997), which deemed the federal RFRA unconstitutional as applied to states. Additionally, the legal doctrine of desuetude, which voids unenforced laws, provides further grounds for challenging Blue laws (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; Robbins Reference Robbins2022).

Figure 1 illustrates important junctures in the evolution of Blue legislation (based on: Gruber and Hungerman Reference Gruber and Hungerman2008; Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; Robbins Reference Robbins2022).

Figure 1. Historical critical junctures in the evolution of Blue legislation.

Research design

This qualitative single-case study examines Blue laws in the United States, focusing on their origins, evolution, and secular reinterpretation. It relies on secondary sources (i.e., academic books) to provide background on the legislation’s development, rationale, and modifications. In addition, qualitative content analysis is applied to primary sources, including Blue laws and the Supreme Court of the United States rulings, to trace the initial motives behind the legislation and the subsequent shift toward secular justifications. Because documentation makes it possible to follow legal and ideological changes over time, this approach offers valuable insights (Flick Reference Flick2018).

Case selection-wise, the study treats the United States as a deviant case (Seawright and Gerring Reference Seawright and Gerring2008). In this sense, it is valuable precisely because it deviates considerably from the expected cross-case pattern in which secular Western democracies display a steady decline in religious influence. By examining how religiously grounded laws in the United States have been reframed in secular terms, we can explore the mechanisms of transformation under conditions of unusually strong religiosity. This deviant case design therefore enables the probing of causal processes that may remain less visible in more typical cases (e.g., Western European countries), while also complementing future comparative research across a wider range of democracies.

Process tracing

The process tracing timeline in this single-case study spans from the critical juncture of state formation (1776) to 2024, with a historical review of Colonial-era legislation to capture the religious roots of Blue laws. To test the causal mechanism, we use a two-step methodological approach integrating theory, chronology, and comparison (Bengtsson and Ruonavaara Reference Bengtsson and Ruonavaara2017). Process tracing within a defined timeline aids both in describing political and social phenomena and in assessing causality (Collier Reference Collier2011). As Hall (Reference Hall, Mahoney and Rueschemeyer2003, 391–392) argues, systematic process analysis is essential for understanding causal complexity. Applied to the United States, this approach reveals how legal-institutional dynamics evolve, showing shifts in legislative justifications as religious rationale is mostly replaced by a secular one.

Our data collection includes an archival review and analysis of primary and secondary sources. Given that this study examines state law, documentation constitutes a significant component of the research. Primary sources (legislation and court decisions issued by official state institutions), along with secondary sources (academic literature, research center reports, and newspaper articles), collectively illustrate the country’s legal framework. Documentation is particularly effective in research conducted over a timeline, as it enables the tracking of legal and institutional change when present (Harrison and Startin Reference Harrison and Startin2013; Yin Reference Yin1994).

Practically, it is important to note that no comprehensive database exists containing all Blue laws in the United States, which has posed a significant challenge in the research process. To overcome this hurdle, we have consulted experts, state secretaries, and the Library of Congress to understand their methods for locating Blue laws or to clarify the specific Blue laws of each state. Experts’ correspondence emphasized the profound lack of literature and centralized information on Blue laws. Professor David Laband (Auburn University) explained that when he and Deborah Heinbuch published their book, there was “virtually no academic research on Blue laws,” and stressed that little has changed in the past four decades, leaving the field without the data necessary for broad, fact-based analysis. He further noted that what little information exists is scattered across local and state sources, making systematic study prohibitively difficult. Professor Ira Robbins (American University) echoed these concerns, describing the absence of a centralized source as “frustrating to say the least,” and argued that the problem reflects both the long historical span of Blue laws and their diversity across states. He concluded that this very scarcity calls for the establishment of a clearinghouse of information. Together, their observations highlight that even in the digital age, academic research on Blue laws remains fragmented, inaccessible, and strikingly underdeveloped. Nonetheless, our data collection drew on both secondary and multiple primary sources to minimize potential discrepancies to the best of our ability.

To acquire information on Blue laws, we began by reviewing secondary sources, including Blue Laws: The History, Economics, and Politics of Sunday Closing Laws by Laband and Heinbuch (Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987), Red, White, but Mostly Blue: The Validity of Modern Sunday Closing Laws under the Establishment Clause by Lawrence-Hammer (Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007), and The Obsolescence of Blue Laws in the 21 st Century by Robbins (Reference Robbins2022). These sources allowed us to establish that Blue laws today primarily regulate three realms, namely alcohol sales, motor vehicle sales, and hunting, and focus our data analysis on them. These categories are the most consistently reflected across the law books of the fifty states, whereas other domains appear only marginally, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions. Such marginality largely reflects each state’s geography, local culture, and historical context, for example, Nevada’s ban on private lawn watering on Sundays in response to water scarcity.

To verify the existence and status of these laws, whether they have been upheld with secular rationale or repealed, we consulted state legal databases and the online legal platform Justia Law.Footnote 2 Justia Law was chosen as the primary database due to its reliability, comprehensive coverage, and robust search capabilities. It provides access to a wide range of legal resources, including the Supreme Court of the United States cases, federal and state regulations, and historical legislation. The platform also offers direct links to state legal databases, allowing us to cross-reference and confirm the accuracy of information regarding Blue laws. Additionally, Justia Law’s archival records enabled us to track modifications or repeals of specific laws over time.

Technically, to locate specific laws in each state, we relied on the search feature of Justia Law. The process involved entering the name of the state followed by a particular area of Blue law restrictions (e.g., car sales). This method was repeated systematically in order to capture all related Blue laws, past and present, for that state. For example, a search for “Virginia Sunday Liquor/Alcohol Sales” would be followed by searches for “Car/Automobile Sales,” “Hunting,” and so forth, until every law containing references to “Sunday” or its variants (e.g., Sabbath, Lord’s Day) had been identified. The results were compiled into lists distinguishing between currently upheld Blue laws and those recently repealed. To identify relevant statutes, we used Justia Law with targeted search prompts such as “Oregon Hunting Laws, Sunday” “Maine Motor Vehicle Sales, Sunday” and “New York Alcohol/Liquor Sales, Sunday.” We also employed broader prompts (e.g., “Tennessee Sunday Laws,” “South Dakota Sunday Restrictions”) to capture additional cases beyond these three domains and affirm its marginality.

Importantly, since state legislatures organize their statutes differently, Blue laws appear in varied sections. For instance, New York’s are consolidated in General Business Laws §2-17 (2023), whereas Maine’s are dispersed: hunting restrictions in Title 12: Conservation (§11205, 2023) and motor vehicle sales in Title 17: Crimes (§3203, 2023). Complications also arise in locating statutory justifications. In Kentucky, for example, the Blue law restricting Sunday alcohol sales (§244.290, 2023) is separated by 23 statutes from its justification, to avoid disorderly behavior, found in §244.120 (2023). Finally, once identified, we examined justifications (religious or secular) and traced statutes back to their original versions for comparison.

While Justia Law served as our primary source, other online platforms helped identify states that restrict alcohol sales, car sales, and hunting on Sundays, the three key areas of interest in our study. These sources included the National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative ActionFootnote 3 (for hunting restrictions), CarParts.comFootnote 4 (for car sales bans), and USA Today Footnote 5 (for alcohol sales regulations). The information gathered from these sources was systematically cross-checked against Justia Law and official state government websites to ensure accuracy. After compiling a list of over one hundred Blue laws currently enacted in state legislatures, we analyzed them to determine their geographic distribution and primary areas of focus. Subsequently, we traced relevant Supreme Court cases to examine how these laws have been interpreted over time and to identify critical junctures in Blue law history. To do this, we relied on Justia Law and Oyez.Footnote 6 Oyez is an online legal project affiliated with Cornell’s Legal Information Institute, Justia Law, and the Chicago-Kent College of Law, providing access to Supreme Court rulings and legal interpretations. These two databases were instrumental in identifying and analyzing key court cases, offering important contextual insights into the broader evolution of Blue laws.

Additionally, while comparing pre- and post-McGowan v. Maryland (1961) Blue laws wording, the sources were drawn from two types of materials. Current laws were identified using Justia Law, while pre-1961 laws, some dating as far back as 1817 and others chosen for their proximity to 1961 (e.g., 1959), were obtained from digitized state law books available to the public (Dewey Reference Dewey1872, 650–651; Indiana 1817, 165–166; Massachusetts 1921, 1:331; 2:1376–77, 1380; State of Missouri 1959, 4736–4737; Townsend Reference Townsend1902, 397–398).

For analysis, classical content analysis is employed to examine the qualitative data. This systematic, flexible, and replicable method allows for the interpretation of text data through coding and theme identification (Burla et al. Reference Burla, Knierim, Barth, Liewald, Duetz and Abel2008; Patton Reference Patton2005; Stemler Reference Stemler2001). Specifically, we used the conventional approach to content analysis, which is suited for describing phenomena when existing theory or literature is limited. This approach enables direct insight without imposing predefined categories or theoretical frameworks (Kondracki et al. Reference Kondracki, Wellman and Amundson2002).

Findings—rationale for Blue laws—a shift towards secular justification

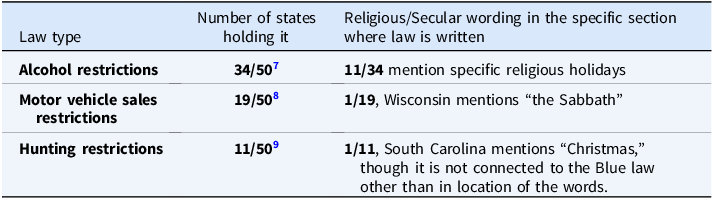

From the early 1600s to the 1800s, hundreds of religiously justified Blue laws were enacted, modified, and repealed across the American Colonies and the United States. Over time, shifting views on religion, society, culture, and economics fueled growing opposition (Laband and Heinbuch Reference Laband and Hendry Heinbuch1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007). A critical juncture for America’s Blue laws occurred in the middle of the 20th century that transformed how the laws were thereafter treated and justified. This turning point is evident in the modification of the laws. Originally, all Blue laws were religiously justified and worded accordingly, yet our textual analysis indicates that today roughly 30% of states retain religious connotations in their Blue laws. The reason for this shift is embedded in the court ruling of McGowan v. Maryland (1961), which established that Blue laws are constitutionally justified in Maryland as long as they do not “infringe upon the religious provisions of the First Amendment” (366 U.S. at 450). This ruling set precedent for other states but, importantly, also realigned the justification of Blue laws from religious to secular rationale—one of promoting a uniform day of rest for all citizens (Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007). Table 1 illustrates existing Blue laws and their rationale.

Table 1. Existing Blue laws and their rationale

As Table 1 above illustrates, our textual analysis shows that in 2024, roughly 70% (34) of the states restrict or ban alcohol sales on Sunday. Of those states, only 11 (31.4%)—Delaware, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Massachusetts, Mississippi, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, and Texas—mention specific religious holidays, such as Christmas or Easter, in the legislation itself. Further, motor vehicle sales are restricted or banned in 38% (19) of the states, with all using secular wording within their legislation except Wisconsin, which uses “The Sabbath” as justification to determine who is exempt. Finally, hunting is restricted or banned on Sundays in 22% (11) of the states, all also using secular wording within the laws, except South Carolina, which mentions Christmas. Other areas of restriction for Blue laws include professional sports games and other retail sales on Sunday, but both affect fewer than 20% of the states in their respective categories and were outside the scope of this study.

Evidently, following McGowan v. Maryland (1961), many states began defending their Blue laws with secular rationale that could withstand tests of constitutionality. The actual use of secular justification revolves around the wording used in the 1961 ruling, mainly claiming that Blue laws prevent “public nuisances” or “disorder” within their states. Examples include Texas Transportation Code § 728.004 (2023), which claims the sale of cars on both Saturday and Sunday creates a public nuisance; Missouri Revised Statutes § 311.770 (2023), which urges prosecutors to uphold their Blue law restricting Sunday liquor sales, as they prevent the creation of “such place as a nuisance”; and Kentucky Revised Statutes § 244.120 (2023), which states that all crimes constituting a misdemeanor as punishment, such as breaking the restrictions on Sunday liquor sales [Ky. Rev. Stat. § 244.290 (2023); Ky. Rev. Stat. § 244.990 (2023)], are to be labeled as creating or maintaining “disorderly premises.” Lastly, three Blue laws on Sunday hunting restrictions [N.J. Rev. Stat. § 23:4-24 (2023); N.C. Gen. Stat. § 103-2 (2023); 34 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 2303 (2023)] stress public safety (limits of 200-500 yards from a place of religious worship as a hunting-prohibited zone) and wildlife management.

While states upheld their Blue laws in court on secular grounds, not all states have completely abandoned the religious roots and arguably religious rationale of their Blue laws. New York and Oklahoma both have legislation that regards “Sabbath breaking” as a misdemeanor and is worded as such in their statutes [N.Y. Gen. Bus. Law § 2 (2023); 21 Okla. Stat. § 907 (2023)]. Maine also refers to “The Lord’s Day” as the time between 12 o’clock on Saturday night and 12 o’clock on Sunday night [17 Me. Rev. Stat. § 3201 (2023)]. All three exemplify religious connotations in current Blue laws. Many states also restrict commerce on religiously linked holidays, as seen in Delaware, Idaho, Massachusetts, and Wisconsin. For example, Delaware [4 Del. Code § 709 (2023)] groups its alcohol sale restrictions on Sunday together with religious holidays, including Christmas and Easter. Idaho [Idaho Code § 23-307 (2023)] prohibits alcohol sales on Sundays, Memorial Day, Thanksgiving, and the specifically Christian holiday of Christmas. It should be noted, however, that this law, as is common among all types of Blue laws, has its exceptions and exemptions, in this case depending on the county’s decision to implement this Blue law at all. Massachusetts restricts alcohol sales on Sunday [Mass. Gen. Laws ch. 138, § 33 (2023)] and, following a trend, includes Christmas as another religious holiday on which sales are also restricted. Lastly, Wisconsin retains the right to revoke sale licenses from car dealerships that are open for buying and selling on Sundays [Wis. Stat. § 218.0116 (2023)]. The law does allow for Sunday sales if the owner believes that Saturday is the “Sabbath” and practices religion, not business, on that day.

Geographically, Blue laws remain most common in the northeastern and southern United States, reflecting the regions’ religious, cultural, and historical traditions, particularly the Puritan legacy along the East Coast (Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007; Robbins Reference Robbins2022). This trend is consistent with the Pew Research Center’s Religious Landscape Study, which shows declining Christian identification and rising religious non-affiliation nationwide between 2007 and 2024. By 2024, the South reported the highest share of Christians at 68% (down from 83% in 2007), followed by the Midwest at 64% (down from 80%), the Northeast at 58% (down from 76%), and the West at 55% (down from 71%) (Pew Research Center 2025). Although the Midwest remains slightly more Christian than the Northeast, the latter’s longer and deeper religious traditions, rooted in earlier settlement patterns, help explain its stronger emphasis on Blue laws compared to the Midwest (Pew Research Center 2025). In 2024, states such as Massachusetts, New York, and South Carolina still maintain some of the most extensive Sunday restrictions in terms of sheer number of laws rather than types of restrictions in place. Conversely, states such as California and Oregon shed their Blue laws by the 1920s and Florida by 1969, while Alaska remains the only state to never have enacted any Blue laws from its incorporation into the Union in 1959 (Gruber and Hungerman Reference Gruber and Hungerman2008).

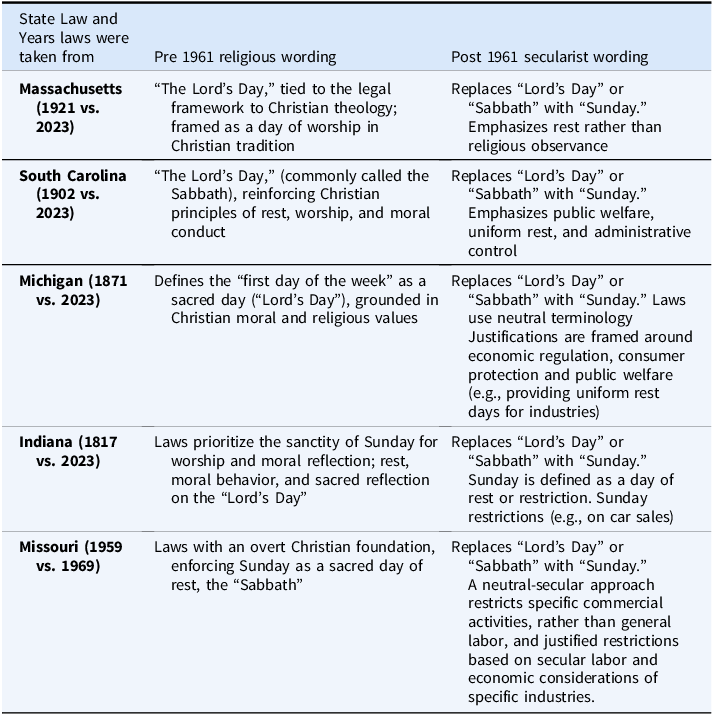

Tracing the evolution of Blue laws across five states, we conducted a textual analysis of various iterations of state legislation. Our sample represents states that have retained restrictions originally established under Blue laws, as the primary objective of this analysis is to examine how religious justifications for these laws have been gradually reframed into secular rationales. Although these states are predominantly located in the Eastern region of the country, they exhibit diversity in their political and economic characteristics. Additionally, all five states have strong historical ties to Christianity, making them particularly suitable for assessing the development and transformation of their Blue laws over time. Their accessible legal archives, including Blue laws from before and after 1961, enable a comprehensive longitudinal analysis. Table 2 below exemplifies the transition in rationale for these laws.

Table 2. Textual analysis of five state’s Sunday observance Blue legislation

A comparison of pre-state and contemporary versions of Sunday observance laws reveals a shift from overtly religious justifications to more secular framing. However, traces of the laws’ religious origins persist. This transformation demonstrates how Blue laws have been adapted to comply with constitutional requirements for secular governance while retaining elements of their religious foundations.

The textual analysis illustrates that early Blue laws employed explicitly moral language, with references to “immoral practices” and frequent use of terms such as “profanely,” “Sabbath breaking,” and the “Lord’s Day,” underscoring a distinctly Christian moral framework. These laws prioritized the sanctity of Sunday for worship and moral reflection, often regulating personal behavior, including prohibitions on swearing, reflecting an intent to impose religious morality on both public and private life. The evolution of these laws following McGowan v. Maryland (1961) marks a significant shift. The justifications for Sunday restrictions now emphasize economic and practical considerations, including labor protections, industry regulations, public welfare, uniform rest periods, and administrative jurisdiction. The language of the statutes has been secularized, with religious terminology such as “Lord’s Day” and “Sabbath” largely omitted, signaling a move away from explicitly Christian doctrine. Although penalties and restrictions remain, they are now framed within public order and economic rationale rather than theological imperatives.

Despite these changes, religious remnants continue to shape modern legislation, as the core restrictions of religious legislation remain, albeit justified in secular terms. The enduring influence of Christian Sabbath traditions is evident in several key aspects of contemporary legislation:

-

1. Sunday-specific restrictions—The continued designation of Sunday as a day for certain prohibitions reflects its historical role as a Christian day of rest.

-

2. Exemptions for Seventh-Day observers—Provisions allowing for religious accommodations, particularly for those observing the Sabbath on Saturday.

-

3. Enduring moral influence—Though ostensibly secular, these laws continue to reflect moral justifications, such as promoting the “public good” or maintaining societal order.

These elements illustrate the enduring impact of religious tradition on modern legal frameworks, even as Blue laws have evolved to align with constitutional secularism and shifting societal norms.

Discussion

The evolving landscape of religious legislation in the United States reflects the ongoing negotiation between the two institutionalized religious freedoms (freedom of and freedom from religion) and the state’s interests, namely the twin tolerations (Stepan Reference Stepan2000). As detailed in the findings, legislative efforts surrounding religious expression, accommodation, and regulation demonstrate a persistent tension between social zeitgeists that value individual rights and legal-institutional arrangements carrying religious remnants. The theoretical framework applied in this study, rooted in historical institutionalism, illustrates how Blue laws, in many cases, persist despite wearing a secular disguise that aims to align with Western democracy’s public preferences.

One of the key themes emerging from the findings is the fluctuating nature of legal interpretations concerning religious freedoms. Judicial decisions and legislative actions often oscillate between reinforcing religious autonomy and imposing regulatory constraints, depending on prevailing political, social, and ideological contexts. This dynamic suggests that religious legislation (or in many cases, its rationale) is not a fixed entity but a responsive mechanism shaped by broader cultural and political shifts. Consequently, the implications for both citizens and policymakers are significant, as legal protections and restrictions continue to evolve in response to contemporary societal concerns. Yet, in many cases, despite the fact that the rationale for the laws has altered throughout history, the institutional restrictions themselves have not, causing a gap between public will and legal-institutional arrangements (Golan-Nadir Reference Golan-Nadir2022). This gap endures throughout history regardless of party politics.

Politics-wise, our review of contemporary Blue laws reveals that no clear partisan divide exists regarding Blue laws, nor have they featured prominently in party platforms. The Warren Court’s decision in McGowan v. Maryland (1961), which upheld their constitutionality, was reached by an 8–1 majority of justices appointed by both Republican and Democratic presidents, suggesting political ideology was not decisive. The other three Blue law cases decided that year—Braunfeld v. Brown, Two Guys from Harrison-Allentown, Inc. v. McGinley, and Gallagher v. Crown Kosher Supermarket—reflect the same trend (Luban Reference Luban1999; McGowan v. Maryland 1961). Moreover, McGowan was argued in December 1960 and decided in 1961, limiting any influence from either Eisenhower or Kennedy despite their appointments to the Court. By contrast, Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014) revealed a clear ideological split, with a 5-4 division along conservative and liberal lines. Although the case was connected to the Affordable Care Act, presidential influence over the ruling itself was negligible.

Partisan differences in attitudes toward religion, however, are evident. A 2019 Pew study found that 83% of Republicans (or those leaning Republican) believed religion is losing influence in American life, and 63% saw this as negative, compared to 74% of Democrats (or those leaning Democrat), of whom only 27% saw this as negative (Lipka Reference Lipka2019). Similarly, 71% of Republicans agreed that churches and religious organizations do more good than harm, compared to 44% of Democrats. These results suggest Republicans are more inclined to support the preservation of Blue laws, while Democrats are less so. Still, contemporary debates occasionally cut across partisan lines; for example, there is bipartisan support in the Northeast for repealing Sunday hunting bans as a means of controlling deer overpopulation (Robbins Reference Robbins2022).

Further, although religious legislation is often associated with conservatism or the Christian Right, this has not always been the case. For instance, Christian support for socialist Eugene Debs in the early 20th century demonstrates this complexity (Lienesch Reference Lienesch1982). Such complexities highlight the need for further research on the intersection of religion, law, and political polarization, particularly as divisions increasingly shape all aspects of American life (Campbell Reference Campbell2020).

Public sentiment in the United States increasingly favors the repeal of Blue laws, driven by social and economic considerations rather than religious opposition (Laband and Heinbuch 1987; Lawrence-Hammer Reference Lawrence-Hammer2007). Although the country remains predominantly Christian, secularization and growing religious diversity suggest that Blue laws may not endure much longer (Lindsay Reference Lindsay2023; Robbins Reference Robbins2022). However, as our findings show, their institutional entrenchment presents significant legal obstacles to repeal. Further, Perez (Reference Perez2023) highlights a rising trend of government support for religious institutions through public-private religious partnerships (PPRPs), which could reinforce legal justifications for Blue laws by framing them as legitimate state policies rather than unconstitutional religious endorsements. As religious institutions receive increasing public funding while maintaining a degree of autonomy, similar arguments may be leveraged to sustain Blue laws under the framework of state accommodation of religion.

Conclusion

In this study we have investigated, under what conditions does religious law, rooted in state establishment, decline in democracies? We argued that when (1) state founders or political elites intentionally refrain from embedding religious arrangements within state institutions, (2) the state apparatus enforces a constitutionalized and explicit prohibition against government-sanctioned religion, and (3) legal justifications shift from religious to secular rationale to maintain their justifiable constitutionality, then reliance on religious law within the state diminishes. However, due to institutional path dependence, laws initially rooted in religious arrangements/traditions may persist but are increasingly framed in secular terms, aligning with the broader secularization of modern Western societies, regardless of the extent of separation between religion and state. Hence, the religious influence and objectives of these laws endure despite the secular disguise. The textual analysis we have conducted supports the hypothesis. Evidently, while Blue laws have evolved in form and shape, their fundamental purpose remains unchanged, serving as a legislative mechanism for upholding Christian values, even if under a secular disguise.

The contribution of this study lies in adopting an institutional perspective, emphasizing that in democratic systems that formally aim to separate religion and state yet possess a strong religious legacy rooted in their pre-state or early statehood years, religious remnants are likely to persist in legislation through historical institutionalist mechanisms such as path dependency and increasing returns. In this process, religious elements may assume a secular guise, yet their underlying nature endures. Consequently, enduring gaps may emerge between existing legal-institutional arrangements and public preferences in Western secular societies (Golan-Nadir Reference Golan-Nadir2022). Furthermore, this study illustrates that religion may serve as a paradigmatic case of an all-encompassing ideology that can hinder legislative change, much like other ideologies such as liberalism or socialism.

Though this study is moderately generalizable, as is appropriate in qualitative methodology (Payne and Williams Reference Payne and Williams2005), the case is still a prime example that can be used to examine how secularization and institutional change occur together within one institutional system. In terms of transferability, the hypotheses tested here can be verified in other democratic states that contain institution-based policy restrictions (e.g., education, taxes, and social work). Hence, although other or additional variables may be incorporated in other contexts or time periods, the mechanism presented here can be considered a preliminary framework for future research. This is to say that our overall theoretical hypotheses are generalizable, while the case in point may be considered deviant, leaving future researchers with only minor adjustments when borrowing from this study for application to different democracies as well as other policy realms.

One of the limitations of our study is that the case presented here is specific in terms of time, place, and context; therefore, we do not claim that identical turns of events will operate in all circumstances. While our hypotheses were validated using data from the relationship between religion and state, we maintain that they apply to other macro-level restrictions in areas such as economics, culture, or the environment. Hence, religion may be considered a paradigmatic case study, a barrier to the provision of public services just as any other barriers are.

Future research should explore religious legislation in more typical case studies, namely other Western democracies such as England, the Netherlands, and France, to provide comparative insights into how different legal systems balance religious freedoms and secular governance. Examining the evolution of religious exemptions, legal restrictions, and political influences in these contexts could highlight broader trends and alternative policy approaches, even in states with strict separation between religion and state, such as France. Additionally, studies should focus on the role of supranational institutions, such as the European Court of Human Rights, in shaping religious laws. Investigating the impact of demographic changes, including increasing religious pluralism, on legislative frameworks would also offer valuable contributions to the field.

Niva Golan-Nadir is a Research Associate at the Center for Policy Research, University at Albany, SUNY, and at the Institute for Liberty and Responsibility, Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy & Strategy, Reichman University. Her research focuses on comparative politics and state-religion relations. In 2024, she was a visiting scholar at the Taub Center for Israel Studies, New York University.

Daniel Smith is a BA student at the Lauder School of Government, Diplomacy & Strategy at Reichman University.