Bishkek, the capital of Kyrgyzstan, began its modern history playing a military role. From around 1825, it was a small, fortified position used by the Khan of Kokand to control passing caravans.Footnote 1 In the early 1860s it was levelled and then captured by the Russian empire. This was presented in Soviet historiography, and is still presented in some Kyrgyz historiography today, as a response by the Russians to a request from the Kyrgyz who were seeking protection from the Kokand Khanate. In 1870, Bishkek became a minor bureaucratic centre for the Russian colonial authorities, and in 1878 it was nominated as the capital for its own small district. Meanwhile, the mountainous parts of what is now southern Kyrgyzstan remained out of St Petersburg’s reach for a little longer.Footnote 2 Tsarist authorities introduced a grid urban planning system for further development, although Bishkek was always a poor sister to Vernyi, now Almaty, the nearby centre of the Semirech’e region (Zhetysu). By 1916, Bishkek’s population had reached 22,000, mainly composed of Russian settlers.Footnote 3 The city was fed by a series of waterways that trickled from the Tian-Shan mountain range downhill into what is today south-eastern Kazakhstan.

Like so many other places, the city was rocked by the series of crises that befell the Russian empire from 1914 onwards: the privations of World War I, the extensive violence of the 1916 Central Asian revolt, the Russian Revolution and the Civil War. Bishkek saw some of the worst colonial violence of 1916. Russian actions caused ‘an estimated 250,000 Kyrgyz to flee across the border to China, suffering terrible mortality in what became known as the Ürkün – “exodus”’.Footnote 4 The remaining Russian population consolidated in the local cities of Tokmak, Przheval’sk and Bishkek itself for protection.Footnote 5 The permanent urban population of Bishkek remained overwhelmingly Russian into the mid-1920s, but Central Asians began to enter into the mix, not only Kyrgyz but Uzbeks, Dungans, Uighurs and other ethnic groups.Footnote 6 As the bitter violence began to subside in 1922–23 and the Communist Party solidified its control, a highly dynamic and unstable situation lingered on in the city.

This article will argue that a particular combination of factors affected the decision-making of those managing Bishkek’s urban growth in the first decade of Soviet power. Principles of property and ownership, nationality politics, lifestyle and water scarcity all had an impact. The Communist Party’s response led to atypical outcomes in the allocation of land and the spatial politics of the city, whereby Kyrgyz pastoralists continued to receive pasturage rights on land controlled by the city later than they likely would have elsewhere in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). This practice was not the outcome of any straightforward deference towards their nationality, but rather emerged from separate legal and economic processes underway in Bishkek, especially demunicipalization, or the reallocation of property from state authorities to residents. As will be outlined later in this article, demunicipalization was both an acknowledgment of the state’s limitations and an attempt to increase economic activity.

As Soviet Bishkek redistributed land and ceded control of property, returning Kyrgyz made use of the peculiar politics of the moment to reap small benefits from the demunicipalization process. Land and property were being ceded by state authorities that lacked the capacity to exploit them properly; it would not be easy to justify the privileging of Russians and others in this process around the capital of the new Kyrgyz Republic. While the city was hardly alone within the Soviet Union in facing myriad pressures after the Russian Civil War, its position was quite singular among comparable cities, such as Ashgabat, capital of the Turkmen Soviet Republic, or Osh, second city of Kyrgyzstan.

Becoming a capital

The trajectory of Bishkek’s urban development changed significantly as a result of its eventual appointment as capital of the Kyrgyz Republic within the larger USSR. The Kyrgyz journey to Soviet titular national status was halting and complicated, partly a corollary of political decisions made about the shape of neighbouring Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. An early effort to separate the Kyrgyz from the Kazakhs in administrative and ethnic terms – a separation that the late tsarist administration had not accepted – was the 1922 proposal from Kyrgyz elites for a Kara-Kirghiz Mountain Oblast. The proposal caused considerable controversy and was swiftly suspended by Moscow; Joseph Stalin himself intervened, raising questions about bourgeois nationalist separatism and the danger of fragmentation for the nascent Soviet bloc.Footnote 7 Nevertheless, a Kara-Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast (KKAO) was eventually created in October 1924, renamed the Kirghiz Autonomous Oblast (KAO) in May 1925, before settling as the Kirghiz Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR) in February 1926 (it would not become a full Union republic until 1936). The KKAO was initially governed from Tashkent while debates took place about the proper placement of the Kyrgyz administrative centre. Arguments in favour of Bishkek included its size, its comparably high infrastructural development and estimates about the literacy rates of its population. The Communist Party’s powerful Central Asian Bureau resolved the matter, and Bishkek became the centre of government for the KKAO in December 1924. The city’s status was thereby rapidly elevated between 1924 and 1926 from a regional administrative centre to the capital city of an ethno-national republic within the USSR.Footnote 8

Like its host region, the name of the city itself changed more than once in the 1920s. Written as Pishpek in the first Russian-language Soviet documents, the city was renamed Frunze in 1926 to coincide with the creation of the Kirghiz ASSR. It is indicative of the ambivalent ethnic politics of the early Soviet Union that the capital city of a new Kirghiz Republic should be named after Mikhail Frunze, a civil war hero and associate of Vladimir Lenin who was born in the city but whose family background was Moldavian and Russian. The city retained the name Frunze until 1991, when the parliament of a newly independent Kyrgyzstan voted to name the city Bishkek. For convenience, the city is referred to throughout the article simply as Bishkek. Mentions of Kara-Kirghiz and Kirghiz in the source material will be rendered as Kyrgyz. Although this greatly simplifies a fluctuating ethnic category in Soviet governance, it communicates the basic premise of a discrete ethno-national group with its administrative centre or capital in a single place.

Further adding to the complexity of Bishkek’s spatial history are the changing administrative structures and territorial areas associated with the city. The early Soviet Union experimented with various typologies of spatial administration, in Russian volost’, uezd, okrug and, in the Kyrgyz ASSR, kanton. Bishkek was also subject to the same dual power structures as elsewhere in the USSR, with both Communist Party and Soviet organs providing oversight. The city was governed by a Communist Party Uezd-City Executive Political Committee until 30 November 1924, when an Okrug Revolutionary Committee or Revkom was created to take its place, part of the bureaucratic outcome of the creation of the KKAO. Then, on 6 December 1926, a Bishkek Kanton Executive Political Committee replaced the Revkom within the new Kyrgyz ASSR. As for the soviet structures, on 14 January 1926, the Bishkek City Soviet of Workers, Peasants and Red Army Deputies was established. From 1926 to 1929, the city’s soviet had six sections: finance and budget, military, trade-cooperative, health, education and communes. In 1929, three more units were added: Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate, administrative-legal and Interhelpo, partly reflecting the growing nuance and specificity of Soviet power in the area.Footnote 9

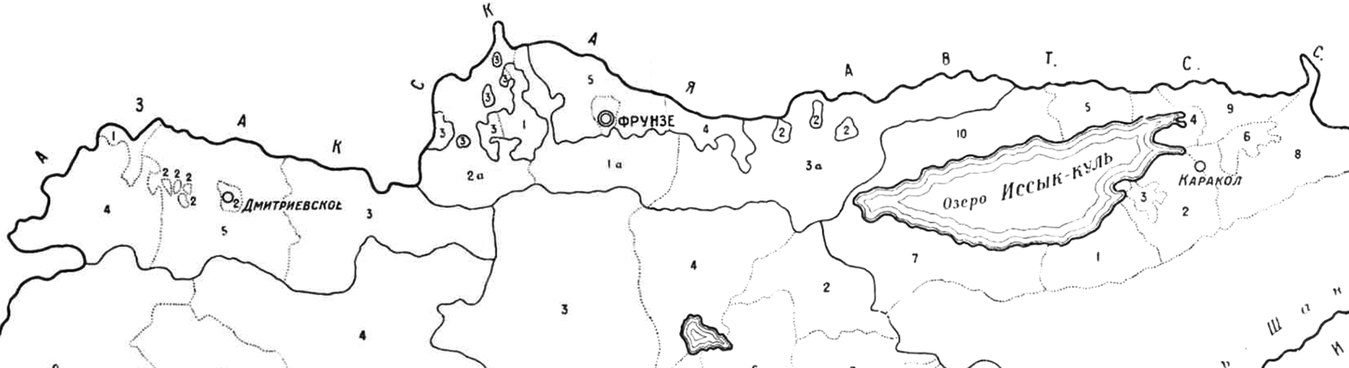

Some of these changes were more impactful for the management of Bishkek’s urban growth than others. The categorization of the space to which Bishkek was tethered changed the city’s notional economic function within the larger Soviet system. Just as important, though, to the undulating outer limits of the city’s jurisdiction was the migratory behaviour of local Kyrgyz. The politics of the city’s innermost core were in dialogue with the city’s outermost environs, not least because it would have been too difficult to delimit these zones with much precision in the late 1920s, given how new and changeable these territorial categories were. A schematic map of the divisions of the Kyrgyz ASSR for 1 January 1927 reveals a Bishkek kanton that stretches narrowly north–south, from the Kazakh–Kyrgyz border to the mountains, and more widely east–west, again from the border with Kazakhstan towards Lake Issyk-Kul. Within the Bishkek kanton, a dotted line on the map forms a rough circle around the city indicating the Bishkek volost’, which marked not its urban core but its territorial limits stretching into the countryside. In every sense, the city’s borders were porous (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Northern Kyrgyz ASSR, 1927.

Source: Vsesoiznaia perepis’ naseleniia: Kyrgyzskaia ASSR Otd. 1 (1926), 242–3. Maps of Soviet Bishkek are available in TsGA KR but reproduction permissions vary. See for example F. 1246. Op. 1. D. 59. L. 5 (1925), or F. 1445. Op. 15. D. 252. L. 73ob (1960s).

The granting of capital status to Bishkek further ethnicized and nationalized the administration of a region and city where ethnic relations were already strained. The implications of this decision were quite plain at the time. In the words of the city soviet in early 1926:

Since [Bishkek] is about to become a capital, one way or another, its population will grow, hence it is worth considering whether it is being serviced properly, in all regards, but the city soviet, from the start, with but one representative, has to take a grip of all the work, as a result of which over the course of barely 2 months it hasn’t been possible to organize works for education or health, so the Plenum considers it necessary to create an independent apparatus of the city soviet with the participation of the Executive Committee.Footnote 10

The point the new city soviet grasped is that Bishkek’s choice as a capital heightened the stakes of the city’s management and its success. Notwithstanding the economic exploitation of the region by the Communist Party, pronounced signs of prosperity in the Central Asian republics were seen by Moscow as a way of advertising the benefits of socialism to other parts of the colonial world; Stalin himself said as much in a letter to the Kyrgyz Communist Party in 1925.Footnote 11 How would it look, the Communist Party asked itself, if not only Kyrgyz citizens, but subjects of the British crown and French colonial empire, saw the capital of the Kyrgyz Republic as a provincial backwater?

The proper management of space in and around 1920s Bishkek became an important battleground in the struggle for development. But this space contained various intersecting features, none of which were easy to control. The political salience of Bishkek as a new capital city was ultimately at the discretion of the central Communist Party apparatus, not its local city branch. Similarly, the heavy pressure placed on local decision-makers to precipitate economic growth, regardless of local specificities, came from the Soviet centre. Then there were the features completely outside of the Party’s early control: the squalor and poverty of city life, the poor administrative capabilities of the authorities and the habits of local Kyrgyz to pasture animals within and around the city’s limits. Each of these will be addressed in turn.

Economic imperatives

Alongside the project of national delimitation, the 1920s was the era of the New Economic Policy (NEP), which is typically presented as a period of relatively laissez-faire economics and political non-intervention after the Civil War. In parts of Central Asia this picture does not hold true; political and economic transformation was on the agenda right from the beginning. But in Bishkek, the economic story does fit more neatly into the NEP model. As a Soviet capital city, a kind of exhibition space for socialist modernization, Bishkek had to develop fast.

It was not entirely a standing start. Bishkek already hosted a diverse range of commercial sites and buildings including hundreds of small traders’ stalls, a slaughterhouse, grain market, breweries, tanneries, flour and oil mills and a public bath. Shopping spaces could be rented out at a fixed rate by retailers.Footnote 12 A temporary cinema ran in the winter.Footnote 13 Latent potential for increased productivity was seen everywhere as the years of acute violence subsided. The Communist Party’s land and water reforms came to Bishkek and other northern regions of Kyrgyzstan earlier than in the south-western half of the republic.Footnote 14

But the city was also wracked with problems and the administration was very weak. The city’s militia received no wages for two months in 1923 and for much of spring 1924.Footnote 15 In August 1924, the prison in Bishkek was a converted caravanserai, steadily undergoing renovation work. The city’s prison service had 22 staff members for 114 prisoners.Footnote 16 Bishkek faced a slew of social problems: unemployment, poverty, prostitution, ill-health and drunkenness.Footnote 17 Foreign Party-affiliated professionals, including clerical staff and legal experts, typically stayed in Bishkek only briefly before requesting permission to relocate north to European Russia.Footnote 18 The economic functions of the city’s administration ‘existed only on paper’, with barely the power to nominate patrons, and lacking even the most basic bureaucratic resources.Footnote 19 All the while, the city’s population was growing; the 1926 all-Union census listed 36,610 individuals living in Bishkek, still overwhelmingly Russian, and 129,093 in its larger kanton.Footnote 20

As was often the case in the early Soviet era, lists of objectives for local soviets and Communist Party committees communicated not only the huge ambitions of the authorities, but also the extent of their ignorance. The Bishkek City Committee had at best patchy information on the ownership and use of large swathes of its jurisdiction.Footnote 21 All the same, Bishkek had to use this information to achieve economic growth. Land was to be made as productive as possible. Surveyors were hired to assess land for new farms, industries and infrastructure. Bazaars had to be regulated; residential property had to be fire-proofed; four new city wells had to be dug and waste disposal – among the city’s most pressing issues – had to be professionalized. Some streets were caked with alluvial sediment; the Alamüdün River cut across the city but there were not enough crossings for ease of transit.Footnote 22

The degree of incipience in the urban economy is perhaps best exemplified by the first protocol of the congress of local committees held on 26 March 1928 to discuss budgetary matters connected to the construction of the Turkestan–Siberian railway. The protocol planned in minute detail the day-to-day operations of a new general shop for the city, down to the proper method for displaying product prices and the location of a complaints box.Footnote 23 But in another way, this protocol was unrepresentative. In recognition of its low administrative capacity, the city soviet’s most typical approach to development in the 1920s was to hand over ownership and control of local resources back to residents, where it had often rested before the Revolution. This instinct, born of necessity, would have counterintuitive consequences. Some of the new residents then entering Bishkek combined strong political claims to land and property with an economic profile which the Communist Party did not value.

Returning nomads

If there was already a stark contrast between the realities of city life and the authorities’ growing ambitions for administrative control (a contrast felt across the Soviet Union at this time), in Bishkek the juxtaposition was heightened by the entry and re-entry of Kyrgyz pastoralists into the city limits. Some Kyrgyz came as part of the returning ebb and flow of seasonal migration following the disruption of the Civil War. Many others entered the area from outside Soviet territory, particularly from Xinjiang, where they had fled during the 1916 uprising and the colonial violence that followed, and waited until the worst upheavals of the Soviet 1920s had passed before returning to their homeland. Frequently, they still found new settlers from European parts of Russia constructing dwellings in their family’s traditional pastureland, a jarring experience given the Bolshevik regime’s public pronouncements about the end of tsarist injustice in the new era of communism. Others returned to land that they themselves had cultivated to grow and harvest grains, whether to feed livestock or themselves.Footnote 24 That the Kyrgyz were often destitute, presenting themselves as refugees in their own capital, further intensified their resentments.Footnote 25 Even where settlers had occupied a plot before 1916, the nomadic habit of leasing lands to European settlers during the tsarist era may have meant that the Kyrgyz still deemed the land to be their property.Footnote 26 The state was not in a strong position to dissuade them otherwise. In October 1924, the local Party committee added to its usual complaints about its position, such as its dearth of funds, facilities and workers, the lack of clarity about the ‘national-territorial demarcation of districts which was only decided upon recently’.Footnote 27

Kyrgyz pastoralists entered the city with their herds of cattle and sheep, sometimes to trade at bazaars, sometimes to resettle permanently on viable land, but also to pasture during the winter months. Traditionally transhumant, many Kyrgyz led their animals high up in the mountains during the summer, and then trekked back to Bishkek in the lowlands as the weather turned cold and ice covered the mountains. Even those Kryrgyz without herds might have been peripatetic and rarely settled permanently. The city soviet was troubled by all this coming and going, associating it with poor hygiene and sanitation, contaminated waterways and declining veterinary standards. Administrators asked the militia to halt the slaughtering of animals by the side of the road. They also established veterinary points tasked with inspecting 50,000 heads of cattle per year, ideally at each animal’s day of arrival at a new pasture.Footnote 28 Even just outside the city, pastoralism’s impact was felt. When nomadic cattle were watered at the source of the Ala-Archa spring to the south of Bishkek, they churned up sediment. The water then arrived in the city discoloured and undrinkable.Footnote 29 But nomads also compromised water infrastructure in the city itself by allowing their livestock to trample through new aryks, or irrigation channels.

Two things made this entry and re-entry of Kyrgyz possible. First, the Bishkek authorities’ jurisdiction extended well beyond the administrative centre of the city, north into the open fields towards the Kyrgyz–Kazakh border and south towards the foothills of the Tian-Shan mountain range. They governed not just an urban core, but also a large rural periphery. But second, this distinction between environs and city centre should not evoke images of a tight, dense central urban space and a rural surrounding expanse. Bishkek’s centre was itself a sprawling village with a great deal of land between scattered buildings and just a few crossings over the waterways that cut through paths and bordered estates.Footnote 30 The city soviet sought to make a virtue of this, celebrating a garden city. But Bishkek’s administrative area covered 55,000 desiatina of land and even within the city’s innermost area, a sizeable proportion of this space was used for barely regulated pasturage of animals.Footnote 31 This contrasted, for example, with Ashgabat, another Russian imperial frontier city chosen as the capital of a new ethnic republic. As Ashgabat grew up along the Trans-Caspian railway, its urban environment hugged closely to the rail station, the source of employment, resources and security. Turkmen lived in pocketed communities around Ashgabat. They entered it only to trade and negotiate, but did not crisscross it in search of pasture.Footnote 32 On the other hand, Bishkek hosted only two closed, short industrial rail lines until it was connected to the larger rail network in 1924.Footnote 33 Its surrounding environment also incentivized different kinds of transhumance.

When Kyrgyz nomads came into Bishkek, they provoked a competition between two different conceptions of space: their pasturage versus ‘vacant’ urban land awaiting a hundred different kinds of development.Footnote 34 The Communist Party wanted to survey, delimit and distribute all this land for specific and state-approved usage, but lacked the full administrative capacity to do so. To put it in the language of Turkestan authorities in 1926: ‘There still remains to be delimited many plots of arable land despite work entailed in previous plans for land development. Failures are blamed on a lack of technical skill, time and resources…this region is held back due to its location in a mountainous semi-nomadic region.’ By this point, the soviet was hoping to reach the next year with only 157.665 hectares of land left to delimit.Footnote 35

The problem would not be going away. Counterintuitively, the region chosen for the most rapid urban development in the Kyrgyz ASSR was also one of the most important within the long-established nomadic economy. A fort settlement was originally established where Bishkek stood for the same reasons that still applied: access to water, fertile land and easy transit.Footnote 36 The Kyrgyz needed the land and the city was nominated as their capital.

Like the broader history of urban growth in the Soviet Union, Bishkek’s specific history of population surges, showcase industrial development, ambitious social policy, and the complications of mobile pastoralism expressed partly though ethnic tensions, had echoes in other non-Soviet contexts. Later in the twentieth century, post-colonial African states pursued Soviet-inspired High Modernist urban development policies that both frustrated and were frustrated by nomadic migrations.Footnote 37 In both examples, governments used statist economic policies to manage the legacies of colonialism while seeking a distinct, modern form of economic progress connected to notions of emancipation and national pride. Bishkek’s problems and many of its solutions are therefore recognizable from a longer and more global story of industrial modernity, in which new post-colonial authorities decried the repression of old empires but also deemed some indigenous rural social forms as pre-colonial and backward. Post-Soviet Kyrgyz historiography has not altogether parted from that assessment of early Soviet nomadic practice, again presenting the Soviet period less as a rupture and more as part of a longer story of urbanization and industrialization.

Evicting settlers

The arduous management of interests between ethnic groups within the environs of the city best exemplifies the difficult mesh of countervailing pressures brought upon the city’s administrators, who may have most trusted Russians to expedite urban growth but had to celebrate that growth in Bishkek as a capital for Kyrgyz.

In 1926, a group of German settlers were granted a plot of land for agricultural development by Bishkek, just one of many such groups that took land with the formal sanction of city authorities as part of land reorganization and consolidation processes. They found themselves with land in the eastern half of the Bishkek kanton, the Tokmak volost’, which was thought of as a hotbed of manapstvo, or Kyrgyz bourgeois resistance, by the Communist Party.Footnote 38 Tellingly, manapstvo was also associated with wealthy Kyrgyz exploiting the landless and forcing these paupers into indentured servitude or crippling debt.

Three years later, in February 1929, the German settlers submitted a petition of complaint to Communist Party organs in Moscow. First, the German settlers outlined how they were granted land in 1926 in the form of a long-term loan, describing the process as taking place ‘as if we were new settlers’. Second, the petition accused the ‘local population’ of immediately seeking to sabotage the settlers’ work. This apparently began early but intensified in the ensuing years. Kyrgyz nomads reportedly set about flattening buildings, letting cattle trample garden allotments and ruining irrigation efforts. This activity escalated from 1927 to 1928 into efforts by the nomads to summarily evict the settlers from their land.

But the German settlers were particularly disturbed that the local authorities, especially those responsible for the Alamüdün district to the south, had for many months seemed to side with the nomads. The settlers accused the Alamüdün district officials of treating them as transient and belabouring them with nuisance paperwork and furthering the business of local manaps. The petition ends thus: ‘At present, all the desire of government bodies is aimed at raising the cultural level of the population and making sedentary, cultural farmers out of uncultured nomads, only the Alamüdün District Land Management Committee is trying, on the contrary, to make nomads out of cultured settled peasants.’Footnote 39 Cases like this were a matter of life or death for Kyrgyz and settlers alike. At the end of the 1920s, communities were still precarious in the aftermath of state violence, war and revolution. Reliable access to farmland was the difference between stability and destitution for both Kyrgyz and Germans.

Notwithstanding the urgency of the issues at stake, the Kyrgyz authorities were also prone to slow-walk the implementation of new regulations.Footnote 40 This tendency was specifically related to the land question in Bishkek in early 1928. On 5 March 1928, while the German case was playing out nearby, the Kyrgyz Central Executive Committee issued a declaration which suspended the allotment (that is, the confiscation) of surplus residential plots for development; this was in defiance of an order that had been issued in February 1928. The Kyrgyz voiced concern over the lack of formal instructions issued by Moscow (specifically, the NKVD RSFSR) to the city soviet over the proper legal orders for seizing surplus land from landowners. This might be interpreted as an effort by Kyrgyz authorities to stymie the demands for more rapid urban growth, as they were trying to manage the complex ethnic politics in which lands could change hands rapidly and create social friction. Pressure was coming from below as well: later that year, developers declared themselves ready and were pushing for the confiscation to take place.Footnote 41

On 17 April 1928, a type of conflict-resolution commission of three members was created to review disputes arising from housing goals in Bishkek.Footnote 42 A similar tripartite committee of kanton regional bodies looked at the Germans’ case. In December 1929, 10 months after the German community raised its final complaint in a formal petition, the committee formulated an act which moved the German settlers to new surplus land. The location of this land was not specified. The committee stipulated that such a calamitous outcome for the Germans was already foreseen when the settlers were originally granted their plot.Footnote 43

This was not an isolated case. In 1928, a ‘Karl Marx’ commune was granted a new, extensive piece of pasturage for various forms of cultivation in the western half of the Bishkek kanton. The land contained two plots of winter pasture belonging to a Kyrgyz citizen from the neighbouring Kalinin volost’. The commune used those plots for haymaking, and when the Kyrgyz herder returned to their winter pastureland with cattle in tow, the commune’s hay stocks were ruined. Said herder apparently ignored pleas from the commune to respect their ownership and use of the land. They appealed to the managers of the Kalinin volost’ to intervene, revealing the way that executive power had been territorialized (and, by corollary, ethicized) by the municipal authorities.Footnote 44 The Kalinin volost’, like the Alamüdün volost’, sat within the Chui kanton next door to Bishkek, but the Chui kanton’s governing centre was, again, Bishkek itself. The Kalinin kanton’s response was to suggest ‘freeing’ the winter pastures from the commune and compensating the residents of Karl Marx for their losses.Footnote 45

Bishkek’s special dispensations

The specificities of Bishkek’s circumstances seemed to be producing uncommon results. Elsewhere in the USSR, it was unusual for contestations over land use and ownership to be resolved to the benefit of nomads so late in the 1920s. As the decade wore on, the increasing number of cases involving the allocation of land previously used by nomadic groups to new occupants resulted in sedentary farming taking priority over mobile pastoralism. As Stalin tightened his grip, Moscow became both less nervous of secessionism and more suspicious of nationalism. A consensus emerged that class-based analysis could be applied in Central Asia as in Russia, meaning that Kyrgyz could not rely on straightforward assumptions that they were disadvantaged in comparison to European settlers. Some Kyrgyz were themselves class enemies. Most significantly, aspirations for national equality increasingly gave way to the exigencies of economic development, and sedentary agriculture was seen as more productive than mobile pastoralism.Footnote 46

Furthermore, it must be emphasized that in other aspects of Kyrgyz political life, trends pushed in the opposite direction. The late 1920s witnessed a palpable increase in oppressive measures notionally targeting the Kyrgyz manaps or native bourgeoise.Footnote 47 As elsewhere in Central Asia, this resulted in the expropriation of property and exile for prominent Kyrgyz, especially those whom the authorities deemed suspicious.Footnote 48 In part, these were local manifestations of Stalin’s Union-wide policy of full collectivization in the early 1930s. But it had ethnic specificities in the non-Russian parts of the USSR. The language of manapstvo created a pretext to appropriate land when it was already clearly occupied by Kyrgyz, let alone when it could feasibly by presented as empty.Footnote 49

The Bishkek authorities were therefore unusual in still resolving land disputes in favour of nomadic Kyrgyz, and at the expense of sedentary Europeans, so late into the 1920s. They did so not in the further reaches of the Tian-Shan, but in kantons governed from the republic’s foremost urban centre. How can this be explained? Perhaps the most obvious explanation is the political significance of Bishkek itself as a capital city. Kyrgyz were returning, whether from summer pastures in the USSR or from political exile outside Soviet territory, to a city that was now their capital. With so many of them in situ and an understaffed militia in charge, the Bishkek authorities naturally acquiesced to Kyrgyz demands.

This interpretation appears to be consistent with the logic of narrative documents submitted by Kyrgyz about settlers and developers in their pastures. The Bishkek soviet heard from a number of angry European communities who had been forcibly removed from the city’s jurisdiction in the late 1920s. It also received documents, such as petitions and correspondence on behalf of returning nomads who hoped for the ejection of settlers or who were defending the actions they had taken to eject the settlers themselves. They elaborated their position in specifically anti-colonial terms, albeit with some deference paid to the changing class politics of the Soviet Union, and could cite Soviet decrees back at local officials. Their stories were familiar: wrongly evicted from their homes during the 1916 revolt, they fled to western China. When the Bolshevik revolution took place, and following the declaration of a new Kyrgyzstan, the Kyrgyz naturally returned to their customary pastureland. Hard-working and involved in the structures of the Communist Party at the local level, they were natural allies of the government and should not have been forced into to exile from their homeland again.Footnote 50

This explanation is not enough, however. It understates the singularity of the Bishkek case. Pastoralists all over Central Asia, especially in Kazakhstan but also in Kyrgyzstan, were being dispossessed in the late 1920s whether they spoke the language of the regime, suffered egregiously during 1916, or otherwise. Nomadic pasturage was encroached upon to make way for new agricultural and infrastructural projects. The Bolsheviks’ early support for non-Russian national sovereignty, which in any case had never been equivalent to a respect for cultural difference, gave way to the primacy of development. By 1928, the Kazakh Republic’s devastating collectivization drive was just getting underway, an ultimate expression of the Communist Party’s disregard for the lives and livelihoods of nomadic pastoralists, among others.Footnote 51 Persecution of the Kyrgyz manaps escalated to forced expulsion in late 1928.Footnote 52

The nationality politics of the early Soviet Union did take on a different dynamic in Bishkek. But its status as a capital city for the Kyrgyz does not explain this difference. It might be assumed that a capital would be the most intense site of decolonial justice, which was the redistribution of land to indigenous peoples. But by the late 1920s, notions of decolonial justice had been absorbed into a larger political project, the building of socialism, while nationalism had become a target for Stalin’s paranoia. So, if anything, Bishkek was the site of the most intense developmental drive in the Kyrgyz Republic; an exhibition space for the benefits of urban socialism, an idealized model for post-colonial progress. As already explained, this developmental drive was considered to be in tension with the preservation or repatriation of pasturage to Kyrgyz nomads, meaning the latter still needs some further explanation. As predominantly mountain nomads, Kyrgyz would typically be more integrated into urban economies for trade and transit than the Kazakhs of the open steppe.Footnote 53 From the perspective of a Soviet official, the Kyrgyz may have seemed more reliant on travel through and around Bishkek, with fewer alternative options on their seasonal migrations, which were comparably shorter than those that sometimes led Kazakhs into the Kyrgyz ASSR from the north. It is arguable that the Bishkek authorities were more accommodating within their kanton because of these local economic conditions, as in other ways they were less stringent than some of their Kazakh counterparts.

The Bishkek soviet’s paperwork is replete with the same complaints and condescension about nomads as can be found in most Soviet state repositories. But there are further reasons to think that authorities in Bishkek might have been more sensitive and accommodating to the needs of the local nomadic economy. A ‘Case of the Thirty’, involving the isolation of key Kyrgyz figures as bourgeois separatists, gripped the Communist Party there in 1925.Footnote 54 In a story recognizable from elsewhere in Soviet Central Asia, those Kyrgyz involved in the original proposal of a Kara-Kirghiz Mountain Oblast in 1922 were persecuted and purged.Footnote 55 The Kyrgyz Communist Party branch was then riven with in-fighting for the rest of the decade. Ethnic factionalism between Russians and Kyrgyz, which was also institutional factionalism between central and local organs, manifested in administrative tugs of war, especially over the fraught matter of grain requisitioning and the meeting of quotas imposed by Tashkent and Moscow.Footnote 56 Frustrations over the length of time it took for Bishkek to implement other administrative decisions were partly a product of this enmity as well. Decisions favourable to local nomads may have been a manifestation of administrative defiance by Bishkek-based Kyrgyz in the competition between central and republic-level institutions.

Finally, there is another highly specific factor which together with these other local contexts might help to explain the success of Kyrgyz petitions within the Bishkek kanton. It again traces its roots to the years 1916 and 1917. During the Ürkun, Bishkek faced huge population shifts and immiseration. One of the measures taken to cope with these challenges was the haphazard municipalization of much of the property in the city. Residential and commercial buildings were taken under the control of the soviet once it was established after 1917. The soviet then leased out properties back to people seeking shelter. This sweeping extra-legal decision created resentment and conflict for the rest of the decade, especially over the duration of loans in kind made to settlers.Footnote 57 Dispossessed landlords especially felt the loss and keenly awaited the return of their property. This may explain the German petitioners’ specific complaint that they had been granted land in 1926 ‘as if they were new settlers’ (emphasis added).Footnote 58 Perhaps they felt the land, or at least some land, had been theirs to begin with.

The soviet now felt responsible for the social problems associated with the families living under its housing mandate. In early 1924, the city authorities noted that municipalization had deleterious consequences for the upkeep and maintenance of many buildings. Residents could not or did not take care of their dwellings. Buildings were found in a state of disrepair and lawlessness.Footnote 59 They were also badly overcrowded. Municipalization may have mitigated the immediate housing crisis, but it did not solve it. In 1925, the city was still subject to an ‘extreme degree of overpopulation’.Footnote 60 But by then, the authorities’ answer to this was more buildings and more private development, not more state control. Overburdened with problems and faced with hugely ambitious targets received from Moscow, the soviet sought to discharge itself of the maintenance and upkeep of Bishkek’s buildings, and to rely instead on the non-state economy in the context of the NEP.

City authorities themselves began questioning the original legal grounds for municipalization. They drew up long lists of buildings that had been taken under municipal ownership in the early 1920s, and which were due for return to private ownership.Footnote 61 Not all properties made their way back to their original owners. Some municipalized buildings were put out for rent, for residential or commercial use, or deployed for services like the Red Cross, the militia and a children’s nursery. Municipalized land was rented out for use as allotments. ‘Empty’ land was distributed to the Koshchi Union, representatives of the Red Army, professional unions members and so on.Footnote 62 But one way or another, the city disencumbered itself of its holdings.

The basic legal principle of demunicipalization in Bishkek, then, was to return the land to its pre-1917 owners, including empty land. In some cases, these people were Kyrgyz and the land was theirs. The Kyrgyz might have seen the land as their pasturage, or as their agricultural plot, and persuaded the soviet of this, even where the land had previously been designated as ‘vacant’. The notion of empty land is always fraught in an area where nomadic and urban spaces cohabit. It should be noted that the Kyrgyz may not have previously owned the land in the strictly legal sense understood by the tsarist state, which had effectively nationalized much nomadic pasturage in the late nineteenth century.Footnote 63 But in local customary terms, in terms of use, and in terms of the Communist Party’s anti-imperial language, the land had been Kyrgyz. The blatant unfairness of a communist state handing back buildings full of paupers to landowners, while denying Kyrgyz their previously owned pasturelands in a place so badly hit by the 1916 revolt, might have given the nationality politics of the 1920s the added intensity it needed to further Kyrgyz interests and produce Bishkek’s atypical results. Urban legal precedents met revolutionary justice, though only briefly, since the resettlements took place at the very end of the NEP era. Stalin’s First Five Year Plan, and the full collectivization campaign, were just about to commence.

Conclusion

The authorities in Bishkek were neither homogeneous nor constant in the period of demunicipalization. Nonetheless, day after day, Bishkek officials received entreaties from Soviet citizens hoping to receive and develop land. Generally, they approved them, specifying only the size, rough location and water source for each new plot and postponing the management of any ensuing appeals and complaints until later.Footnote 64 The potential for disruption in such a mode of operation was clear given the city’s mission for urban development. But Bishkek’s specific circumstances made this unusual, even self-defeating approach more likely. The city’s administrative borders were widely and vaguely delimited, its urban centre was sprawling and spacious, its administrative systems were unstable and its administrative capacities were limited. The Bishkek Communist Party branch was fractious and sometimes intransigent. The city was spread across important waterways and valuable pasturage, and it received increasing numbers of Kyrgyz refugees and travelling pastoralists. It was the new Kyrgyz capital and, crucially, the nationality politics of the early 1920s would have sat awkwardly alongside a demunicipalization policy which favoured non-Kyrgyz.

After collectivization in the early 1930s, many Kyrgyz remained rural and agricultural in profession, but their mobile pastoralism suffered greatly and halted the seasonal encroachment of herders into the urban environment. The notorious Soviet system of internal passports was used to control urban growth.Footnote 65 As such, a stricter dichotomy between urban and rural space, the kind favoured by an anxious Communist Party branch, became easier to enforce, and was replicated by the culture and identity of city-dwellers, in Bishkek as elsewhere in the USSR.Footnote 66

For the city soviet, this arrangement was more propitious for the transformation of Bishkek into a showroom for the achievements of a non-Russian Soviet nationality in the context of socialism. Bishkek continued to expand. But its transition from light to heavier industry would not come until the Great Patriotic War, which hugely expedited changes in Bishkek’s economic and urban environment. Factories near the Eastern Front (28 in total), in places such as Donetsk and Kursk, were relocated directly to Kyrgyzstan in 1941. This number doubled again the following year. Workers and refugees followed the equipment. Around 90 per cent of the evacuated industrial materials were sent to Bishkek and the Chui Valley region. With the new industrial base came new investments in electrical and transport infrastructure, among other transformations.Footnote 67 The forced deportation of certain national groups to Central Asia by the Stalin regime also changed the demography of Bishkek’s environs.

By June 1984, months after Konstantin Chernenko succeeded Yuri Andropov as general secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, the neighbouring jurisdictions of the Bishkek City Soviet and the Alamüdün district were again under review, trading villages back and forth partly in recognition of the industrial nature of Bishkek’s economy and the more rural economy of Alamüdün. The administrative borders of the city were by this time more orderly and less porous, clearly delineated by long verbal descriptions and by cartography. Bishkek was also vastly larger by population than it had been in the 1920s; the Soviet of People’s Deputies of the USSR listed the city’s population as 632,000 in 1987.Footnote 68 The development of new Bishkek industries increased the productivity of the republic.Footnote 69

Still, Bishkek enjoyed a reputation within the USSR as a garden city; greener, more spacious and less densely packed than its Soviet capital rivals like Tashkent and Almaty. Meanwhile, the permanent Kyrgyz element of Bishkek’s population would remain fairly negligible until the late Soviet period; barely 20 per cent in 1989.Footnote 70 Not until the USSR collapsed and controls on internal migration were eased did Kyrgyz come to outnumber Russians in the city. Then, in the post-Soviet period, Bishkek saw another huge wave of growth and urbanization, coupled with dramatic redevelopment in the residential and industrial landscape, as well as yet more shifts in the ethnic politics of the city.