Introduction

More than half of all medusozoan species belong to the order Leptothecata (2183 out of 3913 meduzoans, WoRMS 2025), a group of thecate-polyp hydroids whose medusae typically have a hemispherical or flattened umbrella, with gonads located on the radial canals (Kramp, Reference Kramp1961). Several lineages in this order have lost the medusa stage entirely, while in others, the polyp (hydranth) stage has never been observed, leading to taxonomic ambiguities and a major knowledge gap in understanding their biology and ecology (Maronna et al., Reference Maronna, Miranda, Peña, Barbeitos and Marques2016). Applying integrative taxonomy, i.e., a combined approach using morphological and molecular identification methods, has advanced our understanding of leptomedusae evolutionary relationships and enabled the detection and association of previously unknown or cryptic polyp stages (Maronna et al., Reference Maronna, Miranda, Peña, Barbeitos and Marques2016; Schuchert et al., Reference Schuchert, Hosia and Leclère2020).

The leptothecate family Dipleurosomatidae (Boeck, Reference Boeck1866) includes five genera of medusae characterized by a narrow-base manubrium, branched or irregularly arranged radial canals, and the absence of statocysts, cordyli and cirri on the umbrella margin (Schuchert and Collins, Reference Schuchert and Collins2024). Hydranths of dipleurosomatids have been described from only one species, Dipleurosoma typicum, based on specimens reared in the laboratory (Cornelius, Reference Cornelius1995). The monospecific genus Dichotomia, represented by the zooxanthellate Dichotomia cannoides (Brooks, Reference Brooks1903), was recorded in the central to northwestern Atlantic Ocean, the South China Sea, and Papua New Guinea (Schuchert and Collins, Reference Schuchert and Collins2024). Here, we used molecular barcoding and in situ photography to describe D. cannoides, recorded for the first time in the Red Sea.

Materials and methods

Five specimens were photographed in situ at North Beach, Eilat, in the northern Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea (29.5428°N, 34.9695°E) (Figure 1) during 25 November 2023, 25 October 2024, 8 November 2024, and 16 November 2024. During 2023, one specimen was photographed using a Canon G7X Mark II camera in a Fantasea FG7XII housing, with a Subsee + 10 diopter and a Sea&Sea YS-D3 Lightning strobe. During 2024, specimens were photographed using a Sony A7RIII camera with a Sony FE 90 mm f/2.8 macro lens in a Salted Line housing with a Subsee + 10 diopter and a Sea&Sea YS-D3 Lightning strobe. All photos were taken while snorkeling, on the surface, during daytime (6:30–9:30 AM).

Figure 1. The distribution map of Dichotomia cannoides. Occurrence data were retrieved from GBIF.Org (https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.2haffv), OBIS (https://obis.org/taxon/289810), and iNaturalist (https://www.inaturalist.org/observations?subview=map&taxon_id=255148) on 8 May 2025. Known occurrences are indicated by blue circles; the new record is marked by a red circle.

On 24 December 2024, one specimen was manually collected while snorkeling in front of the Inter-University Institute of Marine Sciences in Eilat (29.5015°N, 34.9190°E), and was immediately preserved in molecular-grade absolute ethanol. Fieldwork was conducted under INPA permit no. 2024-43522. Mean daily SST at the date of sampling was 22.74 ± 0.05 °C (https://www.meteo-tech.co.il/eilat-yam/eilat_download_en.asp#).

In the lab at the National Institute of Oceanography, Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research (IOLR), the ethanol-preserved sample was examined under a stereomicroscope (SZX16, Olympus, Japan), and its bell diameter was measured. The morphological description was prepared using the photographed specimens, according to Schuchert and Collins (Reference Schuchert and Collins2024).

Total genomic DNA was extracted from the whole specimen using the InviSorb Spin Tissue Mini Kit (Invitek Diagnostics, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s specifications. Following the DNA extraction, the cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) gene was amplified using PCR with universal primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 (Folmer et al., Reference Folmer, Black, Hoeh, Lutz and Vrijenhoek1994). Reaction conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 5 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 45 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 40 s, 51 °C for 40 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, and a final elongation step of 72 °C for 10 min. Obtained PCR products were purified and sequenced by Hylabs (Rehovot, Israel).

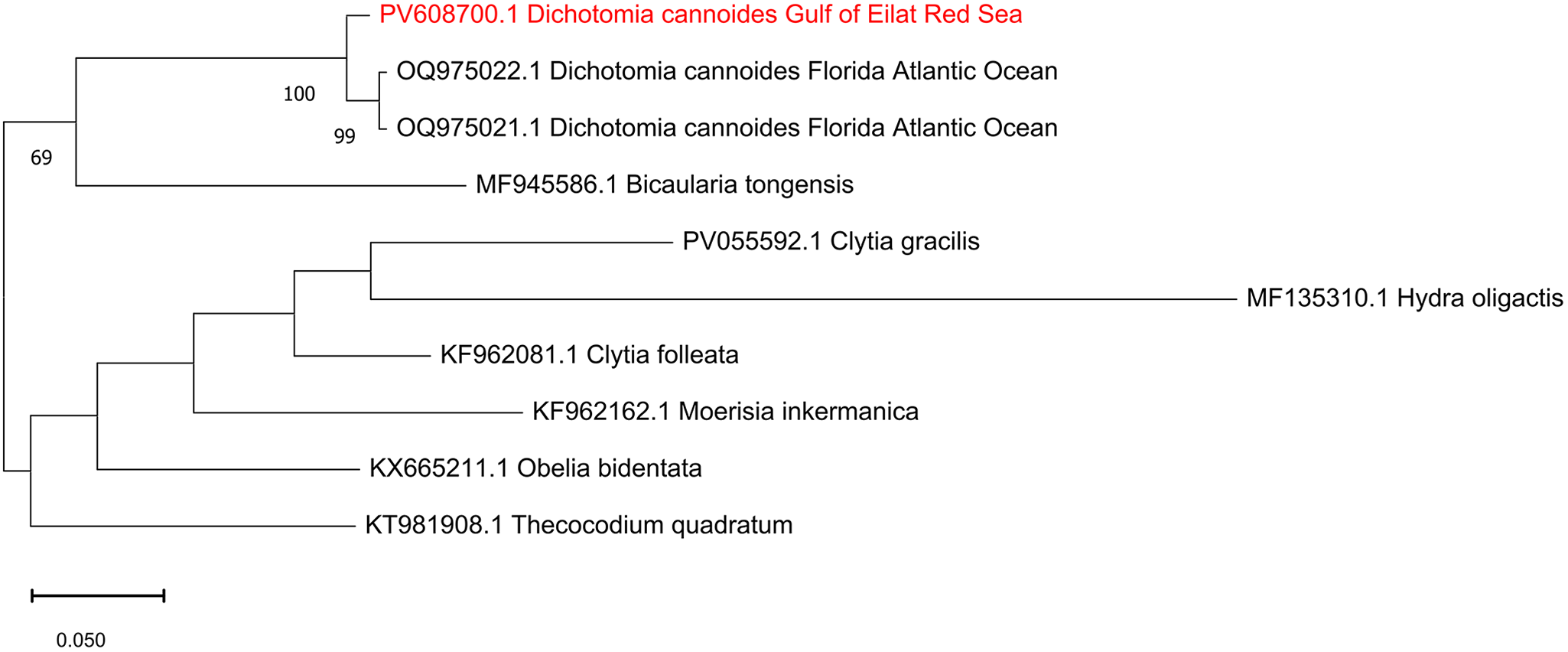

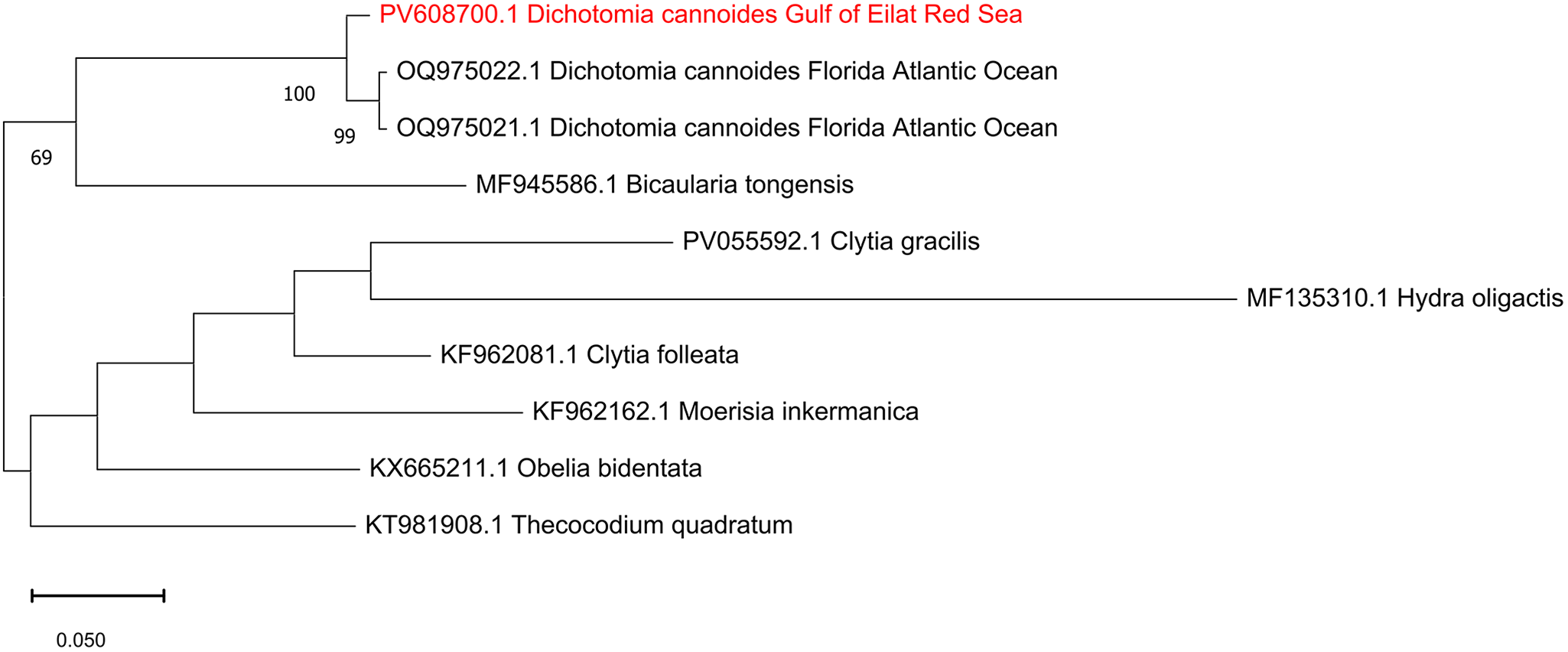

A total of nine COI sequences of hydroids were analysed, including one sequence of D. cannoides obtained in this study and two sequences of D. cannoides from Florida obtained from NCBI GenBank (OQ975021.1- OQ975022.1). As an outgroup, we used Moerisia inkermanica (KF962162.1), Bicaularia tongensis (MF945586.1), Thecocodium quadratum (KT981908.1), Obelia bidentate (KX665211.1), Clytia folleata (KF962081.1), and Hydra oligactis (MF135310.1). Sequence alignment was conducted using ClustalW embedded in MEGA v11.0 (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Stecher and Kumar2021). The best-fitting substitution model was selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion using Maximum-likelihood (ML) model selection in MEGA. ML analysis was performed using the GTR + G model with 1000 bootstrapping replicates.

Results

Morphological description

Dichotomia cannoides (Brooks, Reference Brooks1903): medusae (Figure 2).

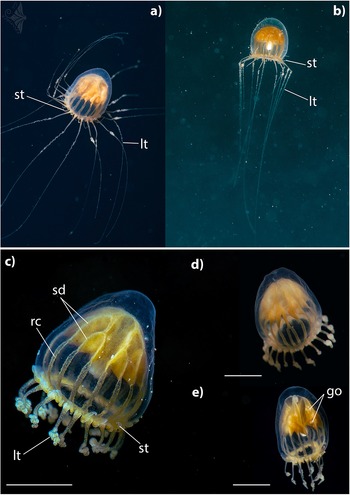

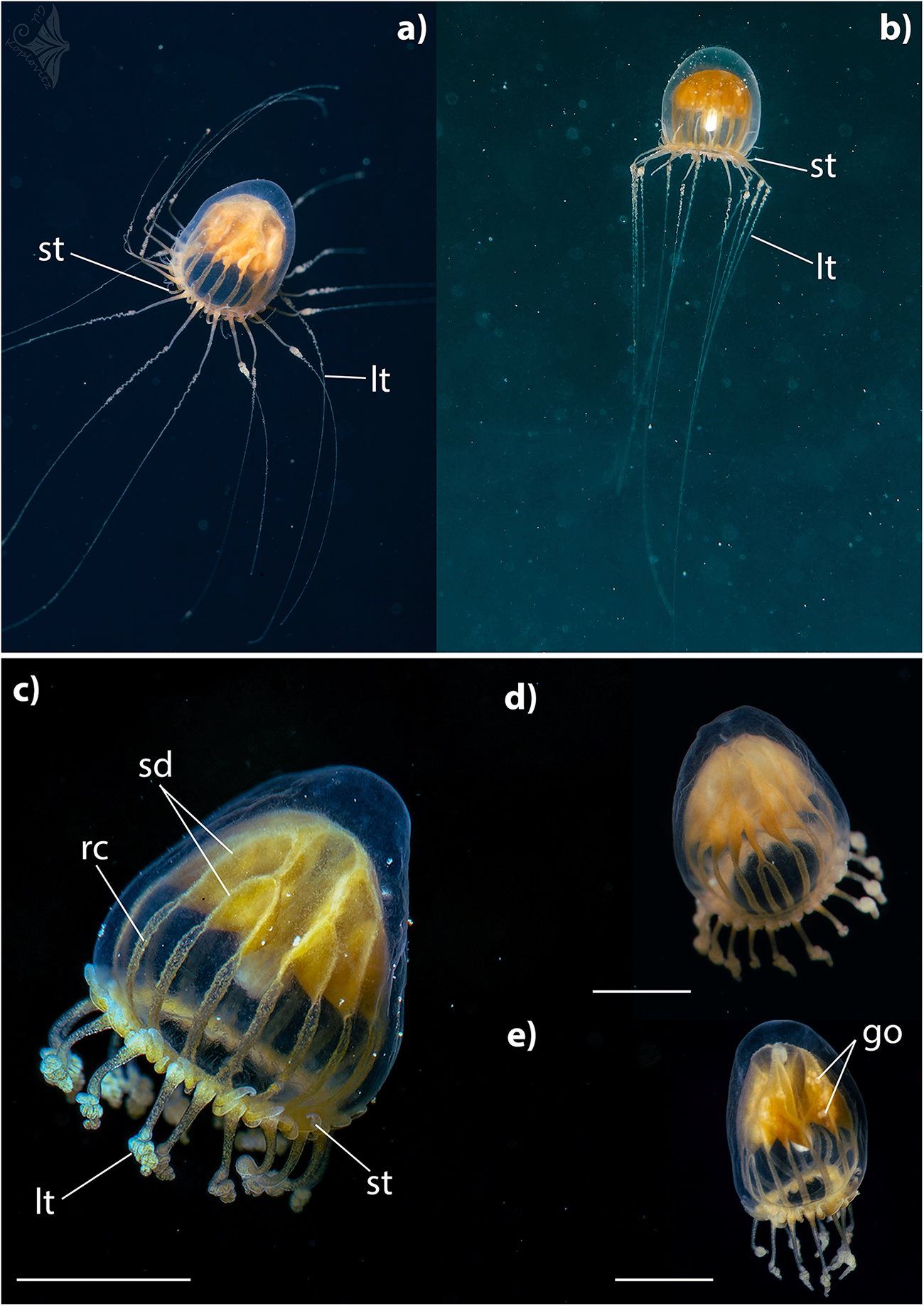

Figure 2. Dichotomia cannoides at North Beach, Northern Gulf of Aquaba, Red Sea. Lt – long tentacles; st – short tentacles; sd – stomach diverticulae; rc – radial canal; go – gonad. Scale bar: 2.5 mm – c,d; 3 mm – e. Photographs were taken in situ by Gil Koplovitz.

Dimensions (preserved specimens): Bell diameter: 3.5 mm. Bell height: 5.5 mm.

Umbrella is morel-shaped. Umbrella height is approximately 1.3–2 times its width. Mesogloea is thickened at apex. Exumbrella is smooth. Stomach is large and complexly branched. Stomach attachment at apex H-shaped, subdividing dichotomously to about 16 diverticula which are then continued as radial canals. Towards the mouth, the manubrium narrows to a cone, with folds on the mouth margin (Figure 2c). Radial canals are approximately half of the subumbrellar height, broad, some subdivided (Figure 2d). Gonads are on stomach diverticula (Figure 2e). Tentacles are continuously arranged along the bell margin. Two types of tentacles distinguishable. Long tentacles up to 16, held downward, evenly tapering, bulb-shaped base with thickened margins and a notch in the middle, distal part curled up, a fine line in the centre. Between each pair of long tentacles 1–3 short thick tentacles that are held upwards, length variable, tip pointed. Manubrium, stomach diverticula, radial canal, and tentacle bases intensively yellow.

DNA barcoding

The DNA barcode consisting of a fragment of 660 bp of the COI gene was sequenced from a medusa of D. cannoides and assembled from forward and reverse sequences. The sequence was deposited in NCBI GenBank under the accession number PV608700. NCBI blastn yielded 98.03% identity to existing two COI sequences of D. cannoides from Florida, USA. Maximum likelihood analysis of hydroid sequences obtained from GenBank (Figure 3) confirmed the identity of the Red Sea D. cannoides.

Figure 3. Maximum-Likelihood phylogenetic tree of Dichotomia cannoides based on the COI gene, using the GTR + G substitution model. The tree was rooted using the hydroid outgroup taxa Moerisia inkermanica, Thecocodium quadratum, Obelia bidentata, Clytia folleata and Hydra oligactis. The numbers below the branches indicate the percentage of ML bootstrap support (1000 replicates) for nodes that received at least 60% support. The scale bar denotes the estimated number of nucleotide substitutions per site.

Discussion

The leptomedusa Dichotomia cannoides was first described in 1903 by Brooks, based on specimens collected in the Bahamas near Nassau in 1887, and at Bimini and Green Turtle in 1886 and 1888, respectively (Brooks, Reference Brooks1903). Subsequent records have documented its presence in the western Atlantic, from the Caribbean to the Gulf of Maine, as well as in the South China Sea and Papua New Guinea (Pagès et al., Reference Pagès, Flood and Youngbluth2006; Schuchert and Collins, Reference Schuchert and Collins2024). The new record of D. cannoides from the northern Gulf of Aqaba represents the occurrence at the highest temperature and salinity levels reported for this species. With the addition of the new D. cannoides record presented here to a previous assessment of hydroid diversity in this region (Pica et al., Reference Pica, Bastari, Vaga, Di Camillo, Montano and Puce2017), the total now stands at 15 species from 9 Leptothecata families.

In situ photography provides the natural shape, colour, and behaviour of delicate gelatinous species, facilitating accurate identification and ecological interpretation (Pantiukhin et al., Reference Pantiukhin, Soto-Angel, Hosia, Hoving and Havermans2024; Schuchert and Collins, Reference Schuchert and Collins2021). Similarly to Schuchert and Collins (Reference Schuchert and Collins2024), the in situ photographs of D. cannoides obtained in this study show upward-directed short tentacles, refuting the assumption that this habitus is due to fixation artefact (Pagès et al., Reference Pagès, Flood and Youngbluth2006). High morphological similarities and overlapping distributions between D. cannoides (Dipleurosomatidae) and the Netocertoides brachiatum (Mayer, Reference Mayer1900) (Melicertidae) led Schuchert and Collins (Reference Schuchert and Collins2024) to argue that they are likely synonym species, and that D. cannoides may belong to Melicertidae. None the less, our COI-based phylogenetic tree shows that D. cannoides and Moerisia inkermanica (Melicertidae) are located in different clades. Molecular data of N. brachiatum is required to test whether it should be reclassified as D. cannoides.

Former occurrences of D. cannoides were recorded in the Western Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea during the beginning-mid twentieth century (Brooks, Reference Brooks1903; Kramp, Reference Kramp1961 Mayor, Reference Mayor1910), yet its small size may have delayed or hampered its identification in other marine regions, including the Red Sea record presented here. While the 2015 hydroid survey of the northern Gulf of Aqaba by Pica et al. (Reference Pica, Bastari, Vaga, Di Camillo, Montano and Puce2017) was conducted in May, our observations of D. cannoides during October to December suggest that its absence in their study may be due to seasonal variation in the medusae presence. Another potential reason for the late detection of D. cannoides in the Red Sea might be a recent introduction by ship ballast or hull fouling (by polyps). Ahuatzin-Hernández et al. (Reference Ahuatzin-Hernández, Ordóñez-López, Herrera-Rodríguez and Olvera-Novoa2024) found the non-indigenous hydromedusa Moerisia cf. inkermanica in the ballast water of oil tankers loaded at the Cayo Arcas oil terminal, Gulf of Mexico. Cargo ships arriving at the ports of Eilat (Israel) and Aqaba (Jordan), both situated at the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba, could have served as vectors for such introduction (Guy-Haim et al., Reference Guy-Haim, Farstey, Iakovleva, Spanier and Morov2024). A more comprehensive analysis of the genetic structure of D. cannoides, including comparisons with Pacific populations and potentially with its symbiotic zooxanthellae (Djeghri et al., Reference Djeghri, Pondaven, Stibor and Dawson2019), may offer further insight into the origin of the Red Sea population.

Several hydrozoan species, including D. cannoides, are known exclusively from their medusa stage, with no validated observations of their polyp (hydroid) phase (Bouillon et al., Reference Bouillon, Gravili, Gili and Boero2006), creating a significant gap in understanding their life cycles, reproductive strategies, and ecological roles. The failure to locate or identify their benthic polyp stages may be due to cryptic morphology, very small or short-lived hydroids, or habitat specificity that makes detection challenging. However, molecular barcoding and the recently-increasing popular use of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding has revolutionized biodiversity assessments, providing highly sensitive, non-invasive tools for detecting organism presence in an ecosystem (Granqvist et al., Reference Granqvist, Goodsell, Töpel and Ronquist2025). Implementing these methods can identify organisms to the species level across different life stages, including those that are elusive (Beng and Corlett, Reference Beng and Corlett2020), cryptic (Hending, Reference Hending2025), parasitic (Iakovleva et al., Reference Iakovleva, Morov, Angel and Guy-Haim2024), rare (Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Simões and Costa2023), or undetectable via traditional methods. These approaches hold great promise for uncovering hidden life stages and resolving long-standing gaps in our understanding of hydrozoan biology.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Miguel Frada, Viviana Farstey, Yoav Avrahami, Merav Gilboa, Asa Oren, and Maya Van Gelder the students who attended the 2024–2025 Introduction to Plankton course at the Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences, Eilat for their assistance in sampling.

Author contributions

T.G-H. has conceived the study, obtained the funding, analysed the data, and interpreted the findings. A.I. has analysed the data and interpreted the findings. G.K and Z.K. has collected the data and helped in the data interpretation. All coauthors contributed to the writing of the article.

Funding

This study was funded by ISF grant no. 1655/21 to T.G-H.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are available in the GenBank Nucleotide Database at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/, and can be accessed with accession number PV608700.1.