High comorbidity rates of internalizing and externalizing problems have been extensively documented among youth and adults (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, Reference Angold, Costello and Erkanli1999; Cerdá, Sagdeo, & Galea, Reference Cerdá, Sagdeo and Galea2008). Epidemiological evidence supports the notion that comorbidity, a condition where two unrelated types of problems co-occur with a rate that far exceeds chance (Caron & Rutter, Reference Caron and Rutter1991), is not a mere artifact of sampling or clinical referral bias (e.g., Angold et al., Reference Angold, Costello and Erkanli1999; Cerdá et al., Reference Cerdá, Sagdeo and Galea2008; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McGonagle, Zhao, Nelson, Hughes, Eshleman and Kendler1994, Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas and Walters2005). The prevalence of comorbidity across internalizing and externalizing problems highlights the need to reconceptualize psychopathology and its development (Eaton, Rodriguez-Seijas, Carragher, & Krueger, Reference Eaton, Rodriguez-Seijas, Carragher and Krueger2015; Eaton, South, & Krueger, Reference Eaton, South, Krueger, Millon, Krueger and Simonsen2010; Krueger & Markon, Reference Krueger and Markon2006). Traditional nosology has been challenged on the grounds that seemingly discrete symptoms may represent at least in part a common underlying pathology for internalizing and externalizing problems (Caron & Rutter, Reference Caron and Rutter1991). Moreover, risk and protective factors need to be investigated in light of comorbidity, because examining one type of problem in the absence of the other is likely to produce biased or incomplete results (Caron & Rutter, Reference Caron and Rutter1991; Liu, Bolland, Dick, Mustanski, & Kertes, Reference Liu, Bolland, Dick, Mustanski and Kertes2016). Comorbidity may also indicate shared etiological factors, as well as direct reciprocal influences, between the two types of problems (e.g., Beyers & Loeber, Reference Beyers and Loeber2003; Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman, & Rathouz, Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011; Timmermans, van Lier, & Koot, Reference Timmermans, van Lier and Koot2010). However, the current research field lacks a strong methodology to represent comorbidity, let alone investigate its risk and protective factors.

Comorbidity is often assessed using DSM diagnoses (e.g., Ha, Balderas, Zanarini, Oldham, & Sharp, Reference Ha, Balderas, Zanarini, Oldham and Sharp2014; Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, Adler, Berglund, Green, McLaughlin, Fayyad and Zaslavsky2014). Such a categorical approach to represent psychopathology has long been criticized, and a dimensional approach has been advocated (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Offord, Racine, Szatmari, Fleming and Sanford1996; Plomin, Haworth, & Davis, Reference Plomin, Haworth and Davis2009; Widiger & Samuel, Reference Widiger and Samuel2005). A dimensional approach is especially relevant for problems emerging during adolescence, as biological, psychological, and social changes during this developmental period blur the boundary between normal and abnormal behaviors (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch2002). One analytic approach to the “problem” of comorbidity in developmental research has been to control for comorbid problems in regression analyses (e.g., Sentse, Ormel, Veenstra, Verhulst, & Oldehinkel, Reference Sentse, Ormel, Veenstra, Verhulst and Oldehinkel2011). This approach is useful for identifying unique risk and protective factors for a specific type of problem. However, it is less useful for identifying common risk and protective factors that predict comorbidity.

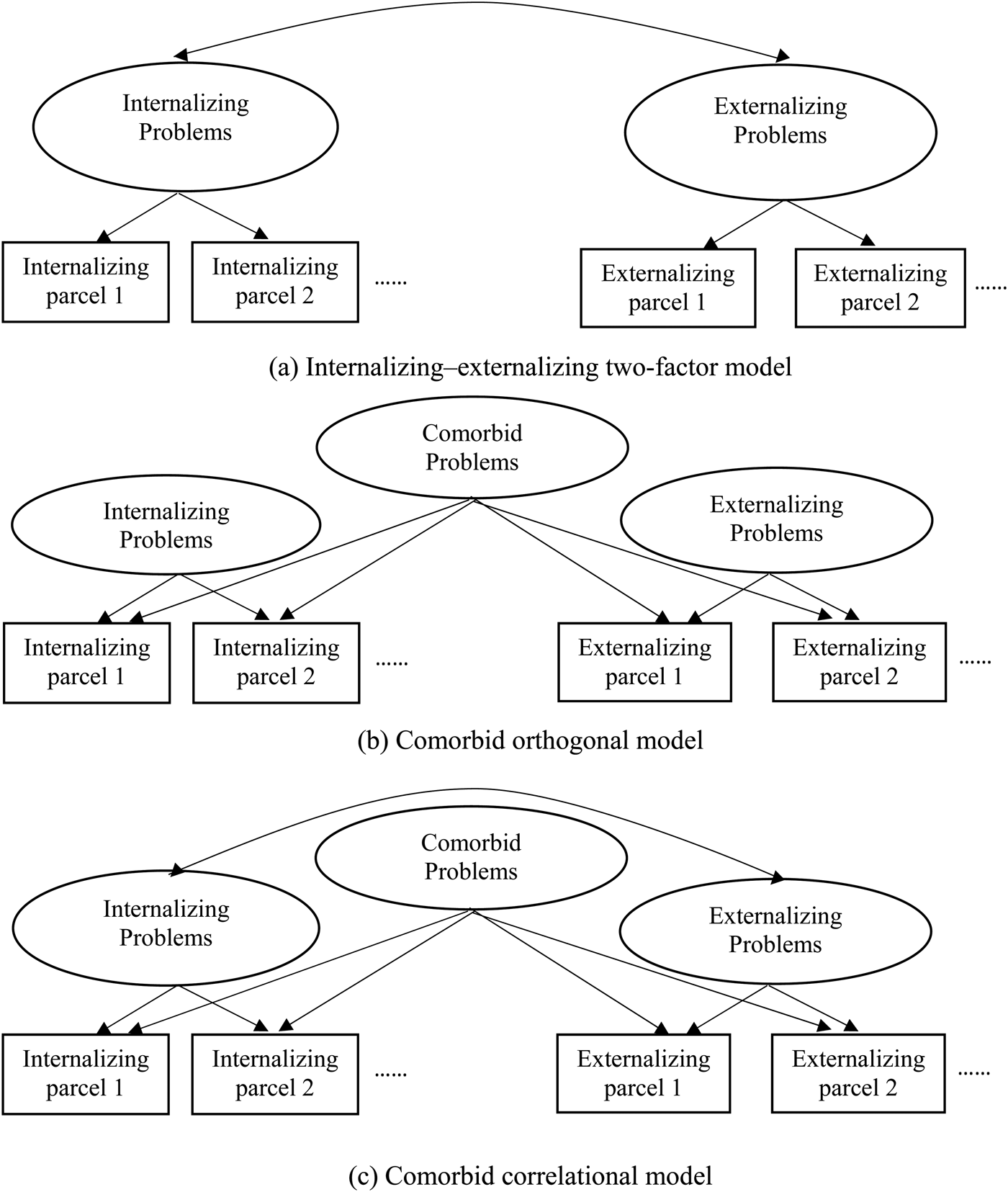

Some efforts have been made recently to address this issue by identifying latent components underlying internalizing and externalizing problems using a structural equation modeling framework. Several latent models for comorbidity have been tested, reflecting different ways of conceptualizing psychopathology. The internalizing–externalizing two-factor model represents discrete symptoms, such as withdrawn/depressed and somatic symptoms, by an internalizing factor, and aggression and rule-breaking behavior by an externalizing factor. Thus, in this model, internalizing and externalizing are cohesive but distinct latent factors (e.g., Rodriguez-Seijas, Stohl, Hasin, & Eaton, Reference Rodriguez-Seijas, Stohl, Hasin and Eaton2015). Although this model has been used with various populations (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, South, Krueger, Millon, Krueger and Simonsen2010), it does not address the covariation across internalizing and externalizing factors. In these models there is often a positive correlation observed between the internalizing and externalizing factors (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, South, Krueger, Millon, Krueger and Simonsen2010). In contrast, other statistical models capture the heterogeneity of internalizing and externalizing problems by distinguishing a general factor underlying both internalizing and externalizing problems from specific factors unique to each type of problem. These models, although varying in what the general factor is labeled, all use the same statistical modeling technique (a bifactor model; Gibbons & Hedeker, Reference Gibbons and Hedeker1992) and all tap into the same underlying issue: that there is a latent factor underlying the commonly observed comorbidity of internalizing and externalizing problems (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge, & Pettit, Reference Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge and Pettit2003; Laceulle, Vollebergh, & Ormel, Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011, Reference Lahey, Applegate, Hakes, Zald, Hariri and Rathouz2012; Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson, & Klein, Reference Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson and Klein2014). When comorbidity is explicitly modeled, the positive correlation disappears, and sometimes residual internalizing and externalizing factors show a negative correlation (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015). This latent structure is found among adults using DSM diagnoses (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Applegate, Hakes, Zald, Hariri and Rathouz2012) as well as children and adolescents using self- or parent-reported questionnaires, such as the Youth Self-Report and the Child Behavior Checklist (Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011; Olino et al., Reference Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson and Klein2014).

One substantial gap in this emerging literature is the lack of attention paid to minority and high-risk populations. Although early reports using latent variable modeling used nationally representative samples, it is unknown whether the latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems is the same among groups that are typically underrepresented in such samples. Epidemiological studies often report lower rates of common psychiatric disorders among African Americans compared to White Americans (e.g., Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Keyes, Krueger, Noordhof, Skodol, Markon and Hasin2013). However, some evidence suggests that African American adults and youth express mental health problems with a symptom profile that is not well captured by common criteria used in national surveys. For example, African Americans show lower rates of DSM diagnosed major depression than White Americans; however, non-DSM instruments capture lower levels of well-being and higher depressive symptoms and distress among African Americans (Eaton et al., Reference Eaton, Keyes, Krueger, Noordhof, Skodol, Markon and Hasin2013). African American youth also report increased externalizing problems, such as anger and aggression, along with depression compared to youth from other racial groups (Anderson & Mayes, Reference Anderson and Mayes2010). These findings argue for a potentially unique latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems among African American youth.

In addition, compared to other racial groups, African American youth disproportionally represent residents living in high-poverty neighborhoods (e.g., Brody et al., Reference Brody, Ge, Conger, Gibbons, Murry, Gerrard and Simons2001; Zenk et al., Reference Zenk, Schulz, Israel, James, Bao and Wilson2005). Cultural ecological theories have proposed that such conditions inhibit the development of competencies in minority children (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Crnic, Lamberty, Wasik, Jenkins, García and McAdoo1996) and present multiple risk factors for developmental psychopathology (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, Gipson, Campbell and Westerholm2006; Ingram & Price, Reference Ingram and Price2010). Thus, the current study aimed to extend newly emerging latent variable models of specific and comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems to a difficult to reach population, namely, African American youth residing in high-poverty neighborhoods.

In addition to elucidating the structure of psychopathology among an underrepresented population in developmental research, a second aim of the study was to examine several salient risk and protective factors within the latent variable modeling framework. The latent variable modeling approach provides a powerful framework to investigate risk and protective factors for comorbid and specific mental health problems (Krueger & Markon, Reference Krueger and Markon2006). Previous studies using latent variable modeling have identified more risk factors that contribute to a comorbid-type factor compared to specific internalizing and externalizing factors (Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge and Pettit2003; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Applegate, Hakes, Zald, Hariri and Rathouz2012). Specific to this sample, we aimed to examine risk factors that are salient for high-poverty neighborhoods not well captured by prior surveys. Residents in high-poverty neighborhoods experience more stressful life events and higher exposure to violence (Carlson, Reference Carlson2006; Evans & English, Reference Evans and English2002). Racial minority youth experience additional adverse events, including racial discrimination (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Crnic, Lamberty, Wasik, Jenkins, García and McAdoo1996). Although there is evidence to suggest that these stressor types increase risk for internalizing and externalizing problems when examined separately, the bulk of this research has been conducted among White and mixed-race samples of youth; moreover, the issue of comorbidity has rarely been taken into consideration.

In studies that examined internalizing and externalizing problems separately, stressful life events, such as major physical injury, loss of a family member, and transition of a primary caregiver, have been linked with both types of problems among predominantly White youth (e.g., Kim, Conger, Elder, & Lorenz, Reference Kim, Conger, Elder and Lorenz2003). Among African American adolescents, stressful life events are associated with internalizing problems (e.g., Gaylord-Harden, Elmore, Campbell, & Wethington, Reference Gaylord-Harden, Elmore, Campbell and Wethington2011; Sanchez, Lambert, & Cooley-Strickland, Reference Sanchez, Lambert and Cooley-Strickland2013), whereas its relation with externalizing problems is far less studied (Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Malone, Stevens, Dodge, Bates and Pettit2006).

Similar to stressful life events, research with White and mixed-race samples of youth has established the negative impact of exposure to violence on internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively (for a meta-analysis, see Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura, & Baltes, Reference Fowler, Tompsett, Braciszewski, Jacques-Tiura and Baltes2009). However, evidence has been less consistent among African American youth (Mrug & Windle, 2009). Exposure to violence has been associated with externalizing problems among African American adolescents in some studies (e.g., Lambert, Boyd, Cammack, & Ialongo, Reference Lambert, Boyd, Cammack and Ialongo2012; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Lambert and Cooley-Strickland2013) but not others (e.g., Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz, & Walsh, Reference Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz and Walsh2001; Grant et al., Reference Grant, McCormick, Poindexter, Simpkins, Janda, Thomas and Taylor2005; Sterrett et al., Reference Sterrett, Dymnicki, Henry, Byck, Bolland and Mustanski2014).

Racial discrimination has been associated with a wide range of mental health problems for African Americans (Clark, Anderson, Clark, & Williams, Reference Clark, Anderson, Clark and Williams1999), including but not limited to depression and anxiety (e.g., Banks, Kohn-Wood, & Spencer, Reference Banks, Kohn-Wood and Spencer2006; English, Lambert, Evans, & Zonderman, Reference English, Lambert, Evans and Zonderman2014), conduct problems (e.g., Brody et al., Reference Brody, Chen, Murry, Ge, Simons, Gibbons and Cutrona2006, Reference Brody, Beach, Chen, Obasi, Philibert, Kogan and Simons2011), and other general psychological distress (Brown & Tylka, Reference Brown and Tylka2011; Bynum, Burton, & Best, Reference Bynum, Burton and Best2007). However, far more studies on racial discrimination have been conducted among African American adults rather than adolescents (e.g., see Williams & Mohammed, Reference Williams and Mohammed2009). Yet compared to adults, minority adolescents might be especially vulnerable to the negative mental health outcomes of racial discrimination, because adolescents are particularly sensitive to social stressors (e.g., Stroud et al., Reference Stroud, Foster, Papandonatos, Handwerger, Granger, Kivlighan and Niaura2009) but possess less matured ethnic identity and stress regulation capacity (e.g., Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Yeh, Gerrard, Cleveland, Cutrona, Simons and Brody2007). In addition, prior studies that did focus on African American adolescents tended to examine a few discrete mental health disorders, in particular depression (e.g., Lambert, Robinson, & Ialongo, Reference Lambert, Robinson and Ialongo2014). The impact of racial discrimination on a wide spectrum of internalizing and externalizing problems has been less examined.

Previous studies have rarely addressed the issue of comorbidity when examining the impact of stressors on internalizing and externalizing problems. Most studies analyzed internalizing and externalizing problems in separate regressions (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Conger, Elder and Lorenz2003; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Lambert and Cooley-Strickland2013), which could not differentiate the effects of stressors on one specific type of problems from the effects on their comorbidity. Some studies analyzed one type of problem while controlling for the other type. For example, stressful life events showed an impact on both internalizing and externalizing problems when their comorbidity was controlled for (King & Chassin, Reference King and Chassin2008). However, this approach is unable to elucidate the impact of stressful life events on comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems. Two studies have examined relations among stressors and mental health problems via mediation analysis using linear regressions. These studies reported that the effects of stressful life events and racial discrimination on internalizing problems were mediated by comorbid externalizing problems among African American adolescents (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bolland, Dick, Mustanski and Kertes2015) and that the effects of racial discrimination on internalizing and externalizing problems were both mediated by trait anger among African American boys (Nyborg & Curry, Reference Nyborg and Curry2003). Both of these studies indicated heterogeneity within one type of problem and covariation between internalizing and externalizing problems; however, these mediation analyses were still unable to pinpoint the impact of stressors on the specific and comorbid components underlying internalizing and externalizing problems. In the present study, we sought to further clarify the relations among stressors with internalizing and externalizing problems using a latent variable modeling approach that could statistically tease apart unique and shared variances among internalizing and externalizing problems.

Moreover, few studies have examined protective factors for comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems, even though both protective and risk factors are essential to understanding the risk and resilience processes in developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Reference Cicchetti and Rogosch2002). Despite the heightened risks related to living in impoverished communities and being a racial minority, most African American adolescents living in disadvantaged neighborhoods do not develop mental health problems. Social support from parents, peers, and community has been documented as one of the important protective processes against adverse developmental outcomes (Cohen & Wills, Reference Cohen and Wills1985; García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Crnic, Lamberty, Wasik, Jenkins, García and McAdoo1996; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, Gipson, Campbell and Westerholm2006; Lee & Goldstein, Reference Lee and Goldstein2016). However, social support has typically been examined on an individual or family level rather than on a neighborhood level (e.g., Browning, Gardner, Maimon, & Brooks-Gunn, Reference Browning, Gardner, Maimon and Brooks-Gunn2014). The ecological systems theory of human development (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1986) suggests that individual development is influenced by risk and protective processes on multiple levels, ranging from individual and family, to community and broader contexts. Neighborhood factors are especially relevant to adolescents, as they start to engage in more activities outside their own households in the community (Aber, Gephart, Brooks-Gunn, & Connell, 1997; Bhargava & Witherspoon, Reference Bhargava and Witherspoon2015). The cultural ecological theory (García Coll et al., Reference García Coll, Crnic, Lamberty, Wasik, Jenkins, García and McAdoo1996) especially emphasizes neighborhood environments for racial and ethnic minority youth, as a neighborhood can be either inhibiting or promoting the development of minority youth depending on its characteristics. African Americans, in particular, tend to establish extended interpersonal connectedness and social support networks (Boyd-Franklin, Reference Boyd-Franklin1989; Choi, Reference Choi2002; Taylor, Chatters, Woodward, & Brown, Reference Taylor, Chatters, Woodward and Brown2013); as such, collectively protective processes around neighborhoods may be especially relevant for youth in neighborhoods that are predominantly African American communities. Previous research suggests that a neighborhood with good connections, spontaneous engagement in the community, high levels of mutual trust, and shared values among residents tends to be associated with fewer risks and is believed to promote positive development. These features of a neighborhood are characterized as collective efficacy (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997).

Neighborhoods with high collective efficacy have been found to have lower violence and crime rates (Ahern et al., Reference Ahern, Cerdá, Lippnnan, Tardiff, Vlahov and Galea2013; Mazerolle, Wickes, & McBroom, Reference Mazerolle, Wickes and McBroom2010; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). Collective efficacy may also buffer the risk effect of neighborhood violence on mental health problems, such as substance use (Fagan, Wright, & Pinchevsky, Reference Fagan, Wright and Pinchevsky2014) and internalizing and externalizing problems (Browning et al., Reference Browning, Gardner, Maimon and Brooks-Gunn2014). Beyond violence exposure, evidence for any protective effect of collective efficacy on other outcomes has rarely been studied in youth of any race. To our knowledge, there is only one study documenting that collective efficacy buffered the risk of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms; however, it was conducted with adults of Asian descent residing in Hong Kong (Chou, Reference Chou2012). There have been no studies testing whether collective efficacy predicts internalizing or externalizing problems among African American youth or whether it may buffer risks associated with racial discrimination or stressful events among residents of high-poverty neighborhoods.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to address several gaps in the literature on understanding comorbidity of internalizing and externalizing problems among an underrepresented population of youth. The first goal of the study was to establish the latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems among a sample of high-risk youth: African American adolescents residing in high-poverty neighborhoods. We analyzed and compared the internalizing–externalizing two-factor model and comorbid models using a bifactor solution that identify a specific internalizing, specific externalizing, and a comorbid problems factor (see Statistic Analysis Plan section and Figure 1). Based on previous results in other populations, we expected the comorbid models to have substantially better model fit than the internalizing–externalizing two-factor model. In addition, because prior studies found negative correlations between the specific internalizing and externalizing factors (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015), we aimed to test whether a similar negative correlation can be found among the present sample.

Figure 1. Alternative confirmatory factor analysis models for the latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems. Youth Self-Report items were grouped into parcels. See the Statistical analysis plan section for a full description.

The second goal was to examine the impact of multiple types of stressors on the latent factors underlying internalizing and externalizing problems. These analyses aim to clarify inconsistent findings between stressors and internalizing/externalizing problems among African American youth in prior studies. Because the three stressors: racial discrimination, stressful life events, and exposure to violence, have been associated with both internalizing and externalizing problems, we hypothesized that all stressors would show significant effects on the comorbid problems factor. Whether these three stressor types would predict the specific internalizing and externalizing factors was less clear a priori, as few studies have utilized the latent model of psychopathology to examine the impact of risk or protective factors. One exception is a study that found an impact of general life stress on a specific externalizing factor across ages 5 to 14 years (Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge and Pettit2003). However, because the study was conducted among predominantly White, middle-class preadolescents and based on maternal report, its results may not necessarily generalize to the present sample.

Finally, we focused on an uncommonly studied but potentially important protective factor, collective efficacy, to advance the understanding of neighborhood impacts on minority adolescents’ mental health. Based on the extensive research of Sampson and colleagues’ (e.g., Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997) in Chicago neighborhoods, we hypothesize that high collective efficacy would mitigate the negative impact of neighborhood violence and other stressors on internalizing and externalizing problems.

Method

Participants

Five hundred and ninety-two African American adolescents (291 male; M age = 15.9 years, SD = 1.43 years; range 13–19 years) from 439 households were recruited from targeted neighborhoods in the Mobile Metropolitan Statistical Area in Alabama. Because of the hard to reach nature of the sample, any adolescents living in the household within the target age range who agreed to participate were enrolled. All statistical analyses corrected for nonindependent observations within household (see Statistical analysis plan section). According to US Census data (2012), 31.5% of African American residents in the Mobile Metropolitan Statistical Area had incomes below the poverty level. Among the present sample, 81.9% lived in a household with less than $20,000 annual income.

Procedure

The present study is part of the Gene, Environment, Neighborhood Initiative. The broad goals of this initiative are to investigate predictors of health outcomes among racial minority adolescents living in high-poverty environments. Families with adolescents between the age of 13 and 19 years in neighborhoods targeted based on US Census data of low household income were reached via flyers and home visits. Interested parents and adolescents were scheduled for an approximately 2-hr survey in a local community center. Some of the families were part of a federal program to relocate from public housing, but analyses of the program found no effects of relocation on internalizing or externalizing outcomes (Byck et al., Reference Byck, Bolland, Dick, Swann, Henry and Mustanski2015), so this effect was not incorporated into analyses presented here. Adolescents and their caregivers provided written assent and consent, respectively. Adolescents provided responses to surveys via a combination of audio–computer-assisted self-interview and interviewer-administered questionnaires (along with biomarker data not reported here). Financial compensation was provided after the study.

Measures

Internalizing and externalizing problems

The Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991) was used to measure internalizing and externalizing problems. The YSR surveys 112 behavioral and emotional problems in children and adolescents from age 11 to 18 years. Each item was scored on a 0 (not true) to 2 (very true) scale. Raw scores were used for statistical analyses. T scores were also generated based on established national norm for descriptive purposes only. A T score above 60 indicates an at-risk level of internalizing or externalizing problems (Achenbach, Reference Achenbach1991). Internalizing problems were composed of three subscales: anxious/depressed, withdrawn/depressed, and somatic complaints. Externalizing problems were composed of two subscales: aggressive behavior and rule-breaking behavior. Each subscale contained 10 to 15 items. The Cronbach α values in this sample were 0.86 for internalizing problems and 0.90 for externalizing problems.

Stressful life events

The Stress Index (Attar, Guerra, & Tolan, Reference Attar, Guerra and Tolan1994) was used to measure stressful life events. It contains 16 questions about frequencies of life events during the past 12 months, such as “A close relative or friend died” or “Your family's property got wrecked or damaged due to fire, burglary, flood, or other disaster.” Frequencies of stressful events were scored on a 0 (none) to 3 (three times or more) scale. Scores on all items were summed to create one summary composite score. The Cronbach α value in this sample was 0.75.

Racial discrimination

The Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff, Reference Landrine and Klonoff1996) was used to assess experiences of racial discrimination within the past 12 months. The original measure developed for use with adults is composed of 18 items, such as “How often have you been accused or suspected of doing something wrong because you are Black?” rated on a 6-point Likert scale (never to almost all of the time). Wording and items were adapted for use with adolescents, resulting in a total of 14 questions of racist events on a 3-point scale (never, sometimes, or a lot). Scores were summed and rescaled to 0–28. The Cronbach α value in this sample was 0.90.

Exposure to violence

A questionnaire version of the Exposure to Violence Interview (Gorman-Smith & Tolan, Reference Gorman-Smith and Tolan1998) was used to assess exposure to violence. Nine specific questions related to victimization and witnessing violence within the last 12 months were asked. Examples of the questions are “Have you seen anyone get shot or stabbed/cut in your neighborhood?” and “Have you been robbed or mugged in your neighborhood?” Answers were coded as 0 (no) or 1 (yes), and scores were summed across all questions. The Cronbach α value in this sample was 0.80.

Collective efficacy

The Collective Efficacy Scale (Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997) was used. The scale originally created for use with adults contains 10 items, such as “How likely is it that your neighbors would get involved or intervene if children were skipping school and hanging out on a street corner?” One item related to city budgets was not included in the adolescent version. The remaining 9 items were scored on a 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely) scale. Scores were averaged to generate a collective efficacy score, with higher scores indicating higher collective efficacy. The Cronbach α value in this sample was 0.77.

Statistical analysis plan

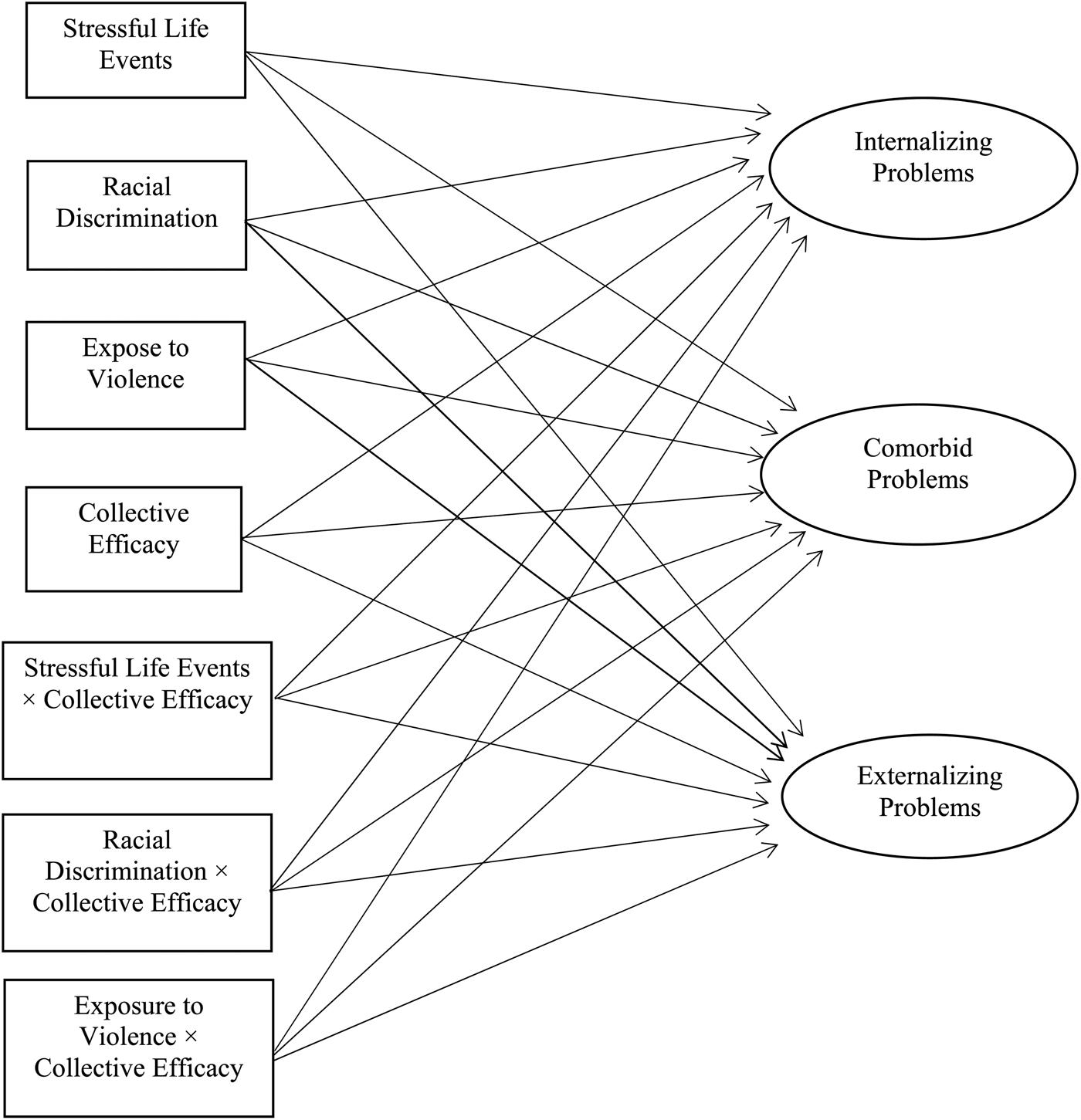

To address the first aim, a latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems was developed by comparing alternative confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) models previously examined in other demographic groups (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge and Pettit2003; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015). Model A, the internalizing–externalizing two-factor model (Figure 1a), established the internalizing and externalizing factors underlying internalizing and externalizing problems, respectively. The correlation between internalizing and externalizing factors was estimated. We estimated two additional models using a bifactor solution (Gibbons & Hedeker, Reference Gibbons and Hedeker1992). Model B, the comorbid orthogonal model (Figure 1b), estimated an additional factor, representing comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems. No correlations between the specific internalizing and externalizing factors or the comorbid factor were allowed. Model C, or the comorbid correlated model (Figure 1c), resembled Model B, except the correlation between the specific internalizing and externalizing factors was estimated. These CFA models were estimated based on parcels of the YSR items, as recommended for questionnaires with numerous individual items (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, Reference Little, Cunningham, Shahar and Widaman2002). Following Little et al.’s (2002) guideline, questionnaire items within each subscale (e.g., anxious/depressed and rule-breaking behavior; see Figure 2) were randomly divided into 2 or 3 parcels, resulting in 12 parcels, each with five to six items. Participants from the same households were clustered to account for nonindependent observations (Byck, Bolland, Dick, Ashbeck, & Mustanski, Reference Byck, Bolland, Dick, Ashbeck and Mustanski2013). Maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors and a scaled test statistic (Satorra & Bentler, Reference Satorra, Bentler, Eye and Clogg1994) was used to account for positively skewed YSR scores and clustered sample. Goodness of fit indices of alternative models were compared based on χ2 to degrees of freedom ratio, comparative fit index, root mean square error of approximation, standardized root mean square residual, Akaike information criterion, and Bayesian information criterion. A χ2 to degrees of freedom ratio of <2, comparative fit index values of >0.95, root mean square error of approximation scores of <0.05, and standardized root mean square residual scores of <0.06 are considered good fit (Hu & Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999). Across alternative models, lower Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion indicate better model fit with parsimonious model parameters.

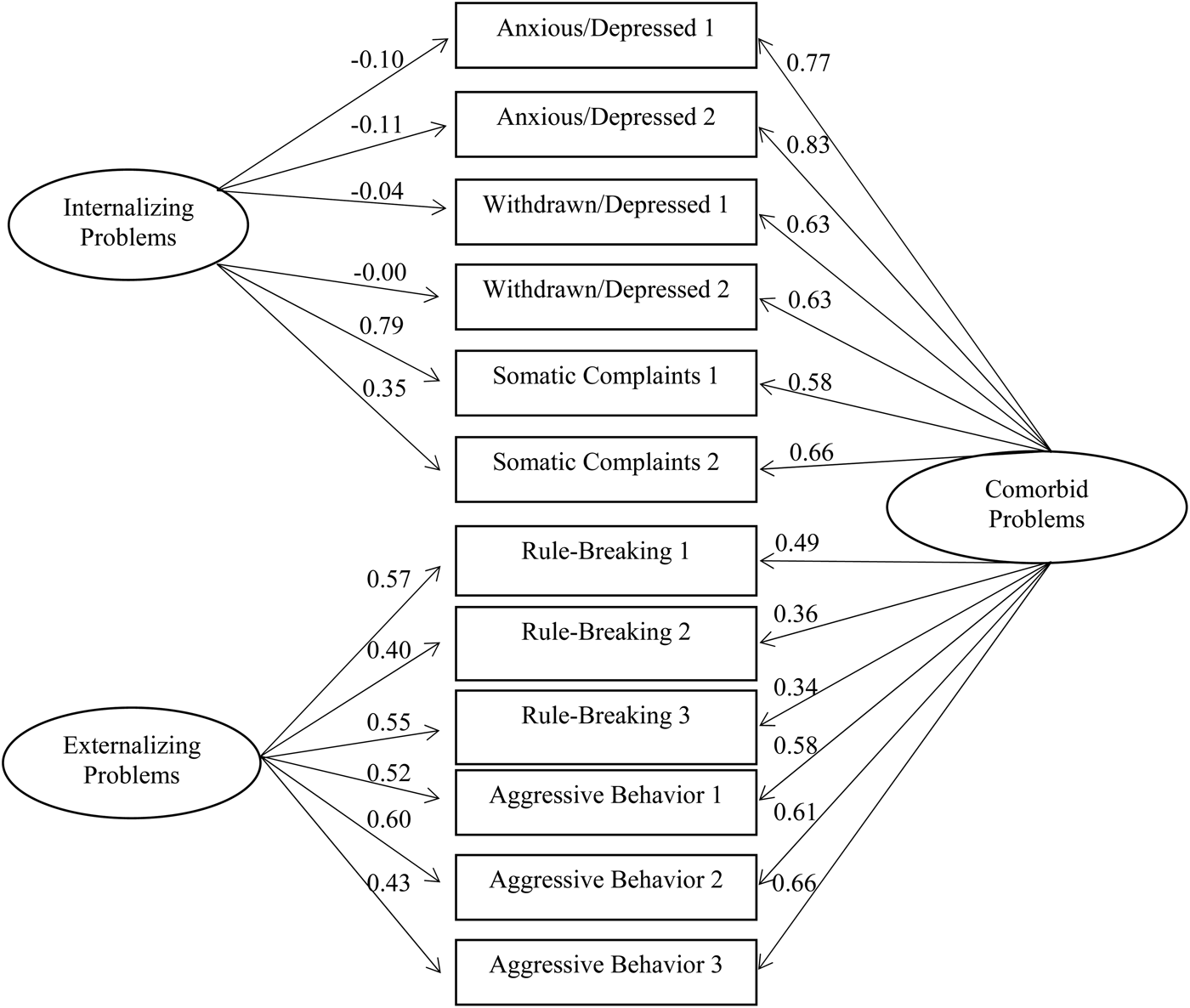

Figure 2. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Youth Self-Report parcels. χ2 = 101.73, df = 42, root mean square error of approximation = 0.05, standardized root mean square residual = 0.03, comparative fit index = 0.98. Standardized factor loadings are shown.

The next set of analyses addressed the second aim of the study to examine risk and protective factors for comorbid and specific internalizing/externalizing problems. The best fitting latent model from the previous step was used to construct a structural equation model (SEM) in which risk and protective factors were included in the model as predictors. Regression paths of stressful life events, racial discrimination, exposure to violence, and collective efficacy on latent factors underlying internalizing and externalizing problems were estimated, controlling for age and gender. To test whether collective efficacy buffers the risk effects of the three stressors, interaction terms between collective efficacy and the three stressor types were computed and entered to the SEM as predictors for the latent factors.

Results

SPSS 22.0 was used to generate descriptive statistics. Mplus version 7.3 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2012) was used for CFA and SEM. Missing data were at low rates (YSR 2.1%, Stress Index 5.1%, racial discrimination 5.1%, exposure to violence 5.1%, collective efficacy 5.1%) and were treated as missing at random.

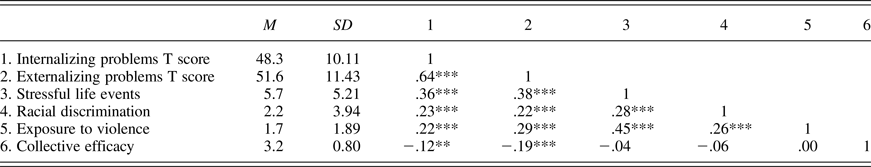

Table 1 lists the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of the variables tested. Internalizing and externalizing problems were highly correlated with each other (r = .64, p < .01). All risk and protective factors were significantly correlated with internalizing and externalizing problems (r = –.19 to .38, p < .01). The three stressor types were significantly correlated with each other (r = .26–.45, p < .01), but not correlated with collective efficacy (r = –.06 to .00, ns).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables tested

**p < .01. ***p < .001.

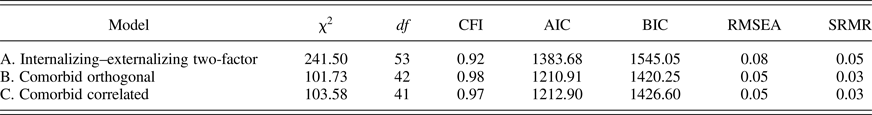

The three alternative CFA models (see Figure 1) were tested and compared by model fit indices. The internalizing–externalizing two-factor model (Model A) showed substantially worse model fit compared to the two comorbid models that use a bifactor solution (Models B and C, see Table 2). The latter two models showed similar model fit indices, with the comorbid orthogonal model (Model B) showing slightly better model fit than the comorbid correlated model (Model C). Moreover, correlation between the specific internalizing and externalizing factors in Model C was not significant (r = .00, ns). Therefore, the comorbid orthogonal model (Model B, Figure 1b) was chosen as the best fitting model for the latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems. Subsequent SEM was based on the comorbid orthogonal model.

Table 2. Model fit comparisons for alternative latent comorbidity models

Note: CFI, Comparative fit index; AIC, Akaike information criterion; BIC, Bayesian information criterion; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual.

Figure 2 shows the latent structure and factor loadings of internalizing and externalizing problems in the comorbid orthogonal model. Parcels from internalizing subscales loaded onto a specific internalizing factor, and parcels from externalizing subscales loaded onto a specific externalizing factor. In addition, both internalizing and externalizing parcels loaded onto a comorbid factor. Parcels from two of the internalizing subscales, anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed, had very low, nonsignificant factor loadings on the specific internalizing factor; only somatic complaints loaded above .35 on the specific internalizing factor. Therefore, the specific internalizing factor should be interpreted as reflecting the component of internalizing problems manifest as somatic symptoms. In contrast, all the internalizing parcels had consistently high loadings (.58–.83) on the comorbid factor. Externalizing parcels had moderate to high (.34–.66) loadings on both the specific externalizing factor and the comorbid factor.

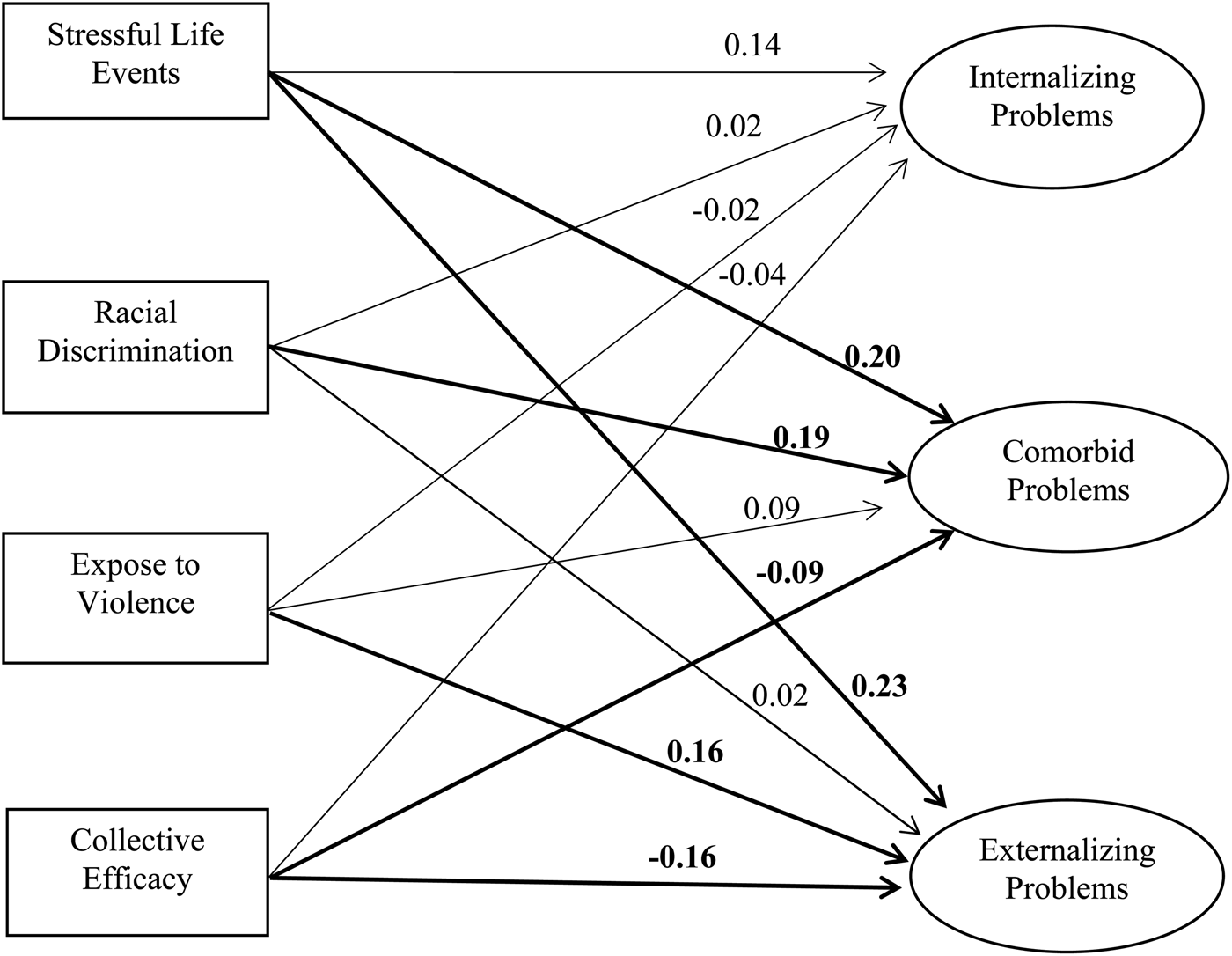

The SEM estimated the effects of risk and protective factors on the latent factors, controlling for age and gender (Figure 3). The comorbid factor was significantly associated with higher stressful life events and racial discrimination (βs = 0.20 and 0.19, p < .01), and was inversely related to neighborhood collective efficacy (β = 0.09, p < .05). The specific externalizing factor was significantly associated with higher stressful life events and exposure to violence (βs = 0.23 and 0.16, p < .05) and was also inversely related to neighborhood collective efficacy (β = –0.16, p < .05). The specific internalizing (somatic) factor was not associated with any of the risk or protective factors assessed in this study.

Figure 3. Effects of stressors and collective efficacy on latent factors of psychopathology. Regression coefficients were standardized. Regression paths and coefficients in bold were significant at p < .05. χ2 = 256.13, degrees of freedom = 96, root mean square error of approximation = 0.06, standardized root mean square residual = 0.03, comparative fit index = 0.94.

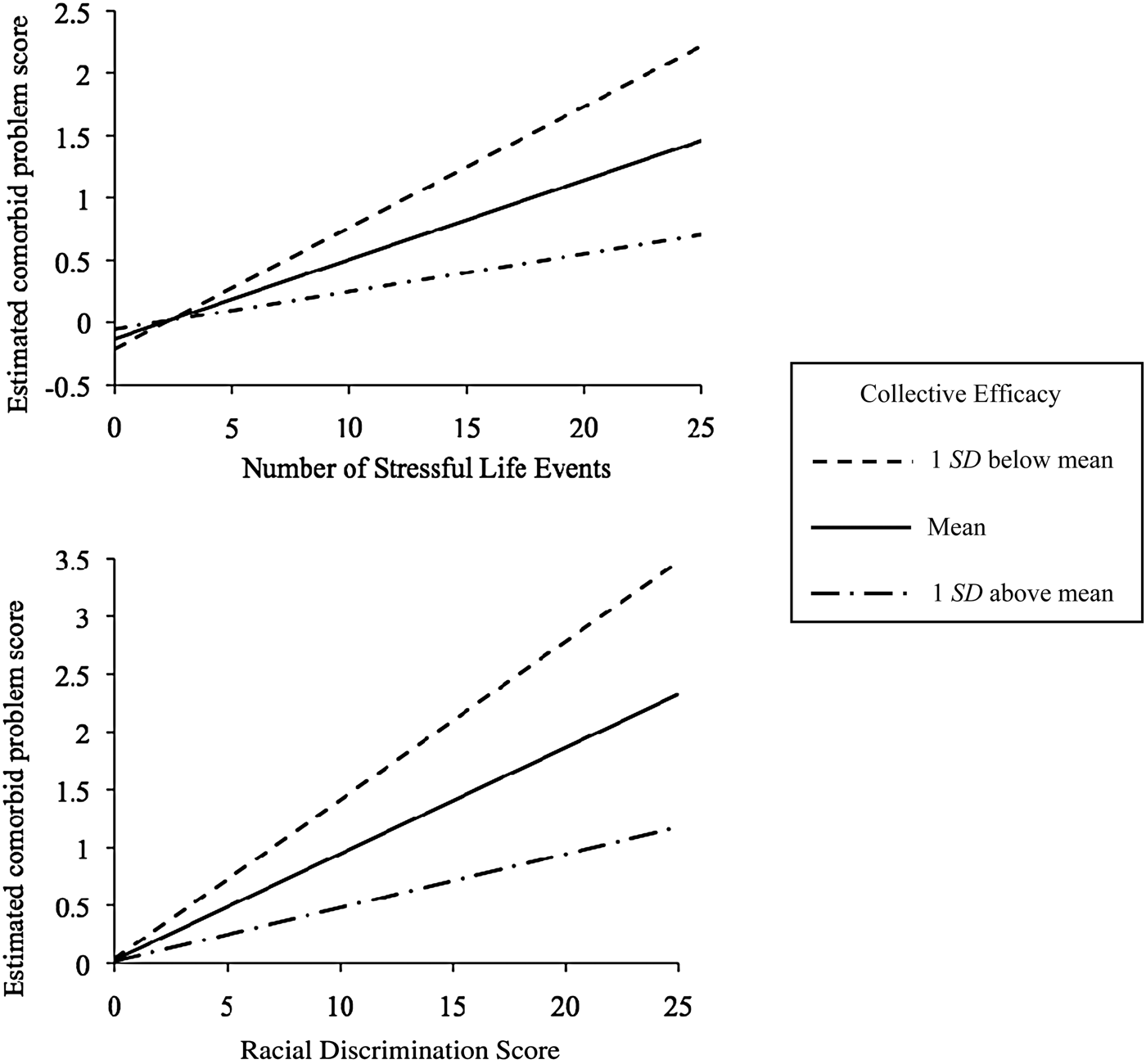

Next the interactions between collective efficacy and the three stressor types on the latent factors were tested (as per analysis model shown in Figure 4). The effects of stressful life events and racial discrimination on the comorbid factor were significantly moderated by collective efficacy (βs = –0.11 and –0.12, p < .05). To interpret these two interactions, we followed Aiken and West's (Reference Aiken and West1991) guideline on plotting interactions between continuous variables. Estimated comorbid problem scores were calculated based on the regression coefficients obtained from the final structural equation model. Figure 5 demonstrated that when neighborhood collective efficacy level was higher (shown as 1 SD above mean), the association between stressful life events/racial discrimination and comorbid problems was weakened compared to when neighborhood collective efficacy level was lower (1 SD below mean). This suggests that high neighborhood collective efficacy buffered the risk effects of stressful life events and racial discrimination on comorbid problems.

Figure 4. Structural equal model testing the interactions between collective efficacy and the three stressors on the latent factors. Main effect variables were Z-transformed to avoid multicollinearity.

Figure 5. Associations between racial discrimination/stressful life events and comorbid problems at different levels of neighborhood collective efficacy.

Discussion

The present study explored the latent structure of specific and comorbid internalizing and externalizing problems in a sample of economically disadvantaged African American adolescents and investigated the impact of stressful life events, exposure to violence, racial discrimination, and neighborhood collective efficacy in the latent variable model. Our results showed a high level of comorbidity of internalizing and externalizing problems. This was evident initially via bivariate correlation among the measured variables. Relevant for latent variable modeling, parcels from both internalizing and externalizing items showed high factor loadings on the latent comorbid factor, suggesting that a substantial portion of variation across internalizing and externalizing problems was attributed to a shared underlying factor. This result is consistent with the growing body of evidence suggesting high factor loadings of internalizing and externalizing problems on a common factor (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge and Pettit2003; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011, Reference Lahey, Applegate, Hakes, Zald, Hariri and Rathouz2012; Olino et al., Reference Olino, Dougherty, Bufferd, Carlson and Klein2014). Previous studies differed substantially from each other and from the present study, in terms of participant race (predominantly White vs. African American), age range (from 3 to 38 years), and measures of psychopathology (ranging from clinically diagnosed DSM disorders to quantitative measures using self-report), yet all studies found a common factor underlying a broad spectrum of internalizing and externalizing problems with high factor loadings. Collectively, these studies demonstrate the robustness of this finding across a variety of populations.

Where the present results diverge from prior reports was the observation in this study of low factor loadings of anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed on the specific internalizing factor. Laceulle et al. (Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015) measured a comparable set of anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed problems among Dutch adolescents and found similarly low factor loading (.39 and .14) on a specific internalizing factor. However, they also measured other DSM internalizing symptoms, such as general anxiety disorder, social anxiety, and panic disorder, and found relatively higher loadings (.21–.59) on the internalizing factor. Other studies that have used the bifactor model have not specifically analyzed the anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed subscales; therefore, results were not directly comparable to the present study. However, regardless of whether data were obtained via diagnostic interview or questionnaire measures among adolescents or adults, internalizing problems in general seem to show lower factor loadings on its specific factor compared to externalizing problems (Caspi et al., Reference Caspi, Houts, Belsky, Goldman-Mellor, Harrington, Israel and Moffitt2014; Kim & Eaton, Reference Kim and Eaton2015; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015; Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Applegate, Hakes, Zald, Hariri and Rathouz2012). One exception is a report that described comparably moderate factor loadings for internalizing and externalizing problems on their respective specific factors (Keiley et al., Reference Keiley, Lofthouse, Bates, Dodge and Pettit2003). However, that study was based on maternal and teacher report among children 5 to 14 years. The observed structure of internalizing and externalizing problems may vary by informant (Youngstrom, Findling, & Calabrese, Reference Youngstrom, Findling and Calabrese2003) or by developmental changes prior and subsequent to the transition to adolescence.

Even among prior studies reporting relatively low factor loadings of internalizing problems on a specific internalizing factor, none reported factor loadings of anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed as low as those found in the present study. There are several possible explanations for this difference. First, compared to White and Hispanic Americans, African American youth are less likely to co-endorse somatic symptoms along with affective symptoms of depression; instead, somatic symptoms among African Americans are a relatively distinct component of health problems (Choi & Park, Reference Choi and Park2006). Consistent with this notion, in the present study somatic complaints loaded primarily onto the specific internalizing factor, whereas anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed both had only very low factor loadings on that same factor, which were not statistically significant. Second, African American youth show distinct symptom expressions of internalizing problems compared to other racial and ethnic groups. Anderson and Mayes (Reference Anderson and Mayes2010) reported that compared to White youth, African American youth are more likely to express depression as anger, aggression, and irritability, which may outwardly manifest as externalizing problems. This may explain why symptoms of anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed in the present sample showed high comorbidity with observed externalizing problems but retained very little unique variance. Third, the present sample was drawn from high-poverty inner-city neighborhoods. Poverty is a documented risk factor for both internalizing and externalizing problems (Yoshikawa, Aber, & Beardslee, Reference Yoshikawa, Aber and Beardslee2012). Thus, it is also possible that chronic exposure to poverty and its related risk factors could more commonly precipitate the development of comorbid problems rather than a specific type of problem (Compas & Andreotti, Reference Compas, Andreotti, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2013).

This study also found no correlation between the specific internalizing and externalizing factors, which differs from the negative correlation sometimes reported in studies using a bifactor model structure (Caspi et al.; 2014; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015). This finding may be due to differences in how symptoms loaded onto the specific and comorbid factors in the population we targeted compared to other studies. It has been suggested that inhibition, which may be characteristic of individuals high in withdrawn/depressed or anxious/depressed symptoms, is “protective” against externalizing problems (e.g., Schwartz, Snidman, & Kagan, Reference Schwartz, Snidman and Kagan1996). In that view, once the comorbidity of internalizing and externalizing is modeled, the residual specific factors would show a negative correlation (Caspi et al.; 2014; Laceulle et al., Reference Laceulle, Vollebergh and Ormel2015). This would not be expected in populations where the specific internalizing factor mainly represents somatic symptoms, whereas withdrawn/depressed and anxious/depressed are largely loading onto a comorbid factor along with externalizing problems. This is precisely what was observed in our sample of African American youth from high-poverty, high-violence neighborhoods. By teasing apart the comorbid component underlying internalizing and externalizing problems from their specific components, the latent comorbid model clarifies the often perplexing relations observed between internalizing and externalizing symptoms.

In brief, the latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems in the present sample demonstrated a comorbid factor as a core feature of psychopathology, a model that is gaining traction in developmental psychopathology. At the same time, the unique findings in the present study with respect to how internalizing and externalizing items loaded onto specific and comorbid factors highlight the importance of applying the latent modeling approach to a diverse set of populations, including those from difficult to reach communities. By separating the comorbid factor from the specific factors underlying internalizing and externalizing problems, our results show distinct impacts of several environmental stressors and the protective effect of collective efficacy on internalizing and externalizing problems via various underlying components.

With respect to racial discrimination, this stressor has previously been shown to negatively impact both internalizing and externalizing problems (e.g., Clark et al., Reference Clark, Anderson, Clark and Williams1999; Williams & Mohammed, Reference Williams and Mohammed2009). The present study incorporated racial discrimination as a predictor in the bifactor model representing specific and comorbid problems. In so doing, our results demonstrated that among African American youth from disadvantaged neighborhoods, the impact of racial discrimination on internalizing and externalizing problems may be fully attributed to their shared component, as racial discrimination did not show an effect on either the specific internalizing (somatic) or externalizing factor. These findings suggest that studies using a traditional regression approach, regardless of whether comorbidity was not assessed or statistically controlled for, may have overlooked the effects on comorbidity between internalizing and externalizing problems. These findings demonstrate the importance of representing both comorbid and specific components underlying psychopathology.

The number of recent stressful life events was significantly associated with higher comorbid and specific externalizing problems but not specific internalizing problems. The results of this study clarify prior research on the association of stressful life events in this population. Using traditional measured variables of internalizing and externalizing problems, the effect of stressful life events on internalizing problems was previously reported as partially mediated by externalizing problems (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bolland, Dick, Mustanski and Kertes2016). However, the latent structure revealed in the best fitting latent variable model demonstrated that the bulk of the variation in internalizing problems in this population was largely accounted for by a comorbid factor, with anxious/depressed and withdrawn/depressed symptoms loading almost exclusively on this factor. Stressful life events predicted the comorbid factor but not the specific internalizing factor, the latter of which reflected only somatic symptoms in this population of African American youth from economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. For externalizing problems, the present results were consistent with and expanded upon prior findings. Among White and mixed-race samples, stressful life events have previously been shown to predict externalizing problems (Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon, & Gipson, Reference Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon and Gipson2004). The present findings expand upon these findings in demonstrating that among high-risk African American adolescents, stressful life events was associated with externalizing problems, and that it did so via effects on a latent externalizing factor as well as a comorbid factor.

For exposure to violence, this risk factor has been associated with externalizing problems in some studies of African American adolescents (e.g., Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Boyd, Cammack and Ialongo2012; Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Lambert and Cooley-Strickland2013) but not others (e.g., Cooley-Quille et al., Reference Cooley-Quille, Boyd, Frantz and Walsh2001; Grant et al., Reference Grant, McCormick, Poindexter, Simpkins, Janda, Thomas and Taylor2005). By isolating the comorbid factor from the specific factor underlying externalizing problems, our results indicated that exposure to violence impacted externalizing problems exclusively via the specific component but not the comorbid component. These findings enabled a clearer understanding that exposure to violence predicts externalizing problems specifically and further illustrates the advantages of employing a bifactor solution incorporating both specific and comorbid components to understand risks for developmental psychopathology.

Higher neighborhood collective efficacy was associated with lower comorbid problems and specific externalizing problems but not specific internalizing problems. Moreover, the results showed that collective efficacy buffered the risk effects of stressful life events and racial discrimination on comorbid problems. These results supported the protective effect of collective efficacy on internalizing and externalizing problems both directly and by mitigating the effects of other risk factors.

Neighborhood collective efficacy appeared to be a distinct predictor of internalizing/externalizing problems, as it was not correlated with any of the three stressor types assessed in this study. Of note, this stands in contrast to some prior research documenting an association of higher collective efficacy with lower violence in Chicago neighborhoods (Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, Reference Morenoff, Sampson and Raudenbush2001; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). However, the studies conducted in Chicago neighborhoods drew from a wide range of socioeconomic status (SES) and racial backgrounds, whereas the present study specifically targeted high-poverty neighborhoods. Previous research suggests that economically disadvantaged neighborhoods often show lower collective efficacy (Kilewer, Reference Kilewer2013; Sampson et al., Reference Sampson, Raudenbush and Earls1997). The average reported collective efficacy in the present study (M = 2.8) seemed to be lower than reported in previous studies (e.g., M = 3.9; Morenoff et al., Reference Morenoff, Sampson and Raudenbush2001). Nevertheless, the present study is the first to report that higher collective efficacy buffers the risks of stressful life events and racial discrimination on a shared component underlying both internalizing and externalizing problems.

Interpretations of this data should be made in light of some limitations. First, we specifically targeted African American youth from extremely disadvantaged neighborhoods; thus, the results may differ compared to other racial or economic groups. Nevertheless, the successful recruitment of a population of youth who are traditionally underrepresented in research and difficult to reach is a strength of the study. Moreover, focusing on disadvantaged neighborhoods may have increased the internal validity of the findings, as we eliminated potentially unmeasured confounding effects of SES, which is often the case in studies of populations with heterogeneous SES backgrounds (see for discussion Umlauf, Bolland, & Lian, Reference Umlauf, Bolland and Lian2011). Second, environmental stressors and mental health problems often show reciprocal influences over time (e.g., Grant et al., Reference Grant, Compas, Thurm, McMahon and Gipson2004; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Conger, Elder and Lorenz2003). The present study demonstrated that environmental stressors were associated with comorbid and specific externalizing problems, but due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, we were unable to examine whether the specific and comorbid components of psychopathology predict future incidences of stressful events. The latent bifactor model should be applied to existing and novel longitudinal studies to elucidate the developmental trajectories of specific and comorbid components underlying internalizing and externalizing problems. Third, reports of collective efficacy in the present study were based on participants’ reported characteristics of the neighborhoods. Comparisons of self-report to other objective neighborhood measures (e.g., presence of neighborhood watch groups) would be important to address in future research. Fourth, future studies incorporating genetic risk factors into latent variable models are also needed. One twin study examining heritability of the latent components underlying DSM disorders found that a latent factor common to internalizing and externalizing problems can be largely attributed to shared genetic risk factors (Lahey et al., Reference Lahey, Van Hulle, Singh, Waldman and Rathouz2011). With the latent structure of internalizing and externalizing problems established, genetic factors and gene–environment interactions can be easily adapted to the latent modeling framework.

Overall, the present study provided consistent evidence for a comorbid factor underlying internalizing and externalizing problems among African American adolescents from high-poverty neighborhoods. The results highlight the benefits of a dimensional rather than a categorical approach to understanding the structure of and risk factors for internalizing and externalizing problems. The structure of psychopathology found in this study indicates that measured internalizing and externalizing symptoms are manifestations of three distinct latent factors. Therefore, research on internalizing and externalizing problems needs to tease apart the unique latent components from their shared comorbid component when examining their developmental trajectory as well as risk and protective factors. In contrast, the distinct features of the specific and comorbid problems found in the present sample compared to previously published reports in other populations call for more studies on youth from diverse sociocultural backgrounds. The latent modeling approach also provided a powerful framework to demonstrate the impact of risk and protective factors on specific and comorbid problems. Specifically, stressful life events and racial discrimination predicted higher comorbid problems, whereas stressful life events and exposure to violence predicted higher specific externalizing problems. Collective efficacy demonstrated its protective effects by directly predicting lower comorbid problems and specific externalizing problems and buffering the risk effects of stressful life events and racial discrimination on comorbid problems. These results provide a promising first step to further understanding the development of internalizing and externalizing problems among racial minority youth and residents of disadvantaged neighborhoods.