1. Introduction

An essential property of turbulence is that it is dissipative. Turbulence dissipation plays a key role in all turbulent flows. The scaling of the turbulence dissipation rate is pivotal in theories and models of turbulent flow statistics and dynamics (e.g. Tennekes & Lumley Reference Tennekes and Lumley1972).

The Kolmogorov scale-by-scale equilibrium for homogeneous stationary turbulence leads to a well-known expression for the turbulence dissipation rate

![]() $\epsilon$

(Batchelor Reference Batchelor1953; Tennekes & Lumley Reference Tennekes and Lumley1972; Sreenivasan Reference Sreenivasan1984; Frisch Reference Frisch1995):

$\epsilon$

(Batchelor Reference Batchelor1953; Tennekes & Lumley Reference Tennekes and Lumley1972; Sreenivasan Reference Sreenivasan1984; Frisch Reference Frisch1995):

![]() $\epsilon = C_{\epsilon }k^{3/2}/L$

, where

$\epsilon = C_{\epsilon }k^{3/2}/L$

, where

![]() $k$

is the turbulent kinetic energy,

$k$

is the turbulent kinetic energy,

![]() $L$

is a measure of the largest turbulent eddies in the flow (an integral length scale) and

$L$

is a measure of the largest turbulent eddies in the flow (an integral length scale) and

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

is a dimensionless coefficient independent of Reynolds number. The Kolmogorov equilibrium means that the average rate

$C_{\epsilon }$

is a dimensionless coefficient independent of Reynolds number. The Kolmogorov equilibrium means that the average rate

![]() $C_{\epsilon }k^{3/2}/L$

with which the large turbulent eddies lose energy to smaller eddies equals the average rate with which the turbulence loses energy by viscous dissipation. However, a different turbulence dissipation scaling has emerged over the past 15 years in various turbulent flows where non-stationarity (including streamwise decay/non-homogeneity) cannot be overlooked: freely decaying periodic turbulence (Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2016b

) where a significantly long early time range exists where

$C_{\epsilon }k^{3/2}/L$

with which the large turbulent eddies lose energy to smaller eddies equals the average rate with which the turbulence loses energy by viscous dissipation. However, a different turbulence dissipation scaling has emerged over the past 15 years in various turbulent flows where non-stationarity (including streamwise decay/non-homogeneity) cannot be overlooked: freely decaying periodic turbulence (Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2016b

) where a significantly long early time range exists where

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

grows while the Taylor length-based Reynolds number decreases; and decaying turbulence generated by fractal or regular grids (Vassilicos Reference Vassilicos2015), turbulent bluff body wakes (Castro Reference Castro2016) and turbulent jets (Cafiero & Vassilicos Reference Cafiero and Vassilicos2019) where a long centreline near-region exists where

$C_{\epsilon }$

grows while the Taylor length-based Reynolds number decreases; and decaying turbulence generated by fractal or regular grids (Vassilicos Reference Vassilicos2015), turbulent bluff body wakes (Castro Reference Castro2016) and turbulent jets (Cafiero & Vassilicos Reference Cafiero and Vassilicos2019) where a long centreline near-region exists where

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

increases whilst

$C_{\epsilon }$

increases whilst

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

decreases along the streamwise direction. In all these cases,

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

decreases along the streamwise direction. In all these cases,

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

and

$C_{\epsilon }$

and

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

vary according to

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

vary according to

![]() $C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

, where

$C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

, where

![]() $ \textit{Re}_G$

is some global Reynolds number characterising inlet/initial/boundary conditions. Time fluctuations of

$ \textit{Re}_G$

is some global Reynolds number characterising inlet/initial/boundary conditions. Time fluctuations of

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

and

$C_{\epsilon }$

and

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

in forced periodic turbulence (Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2015; Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2016a

) and in atmospheric turbulence (Waclawczyk et al. Reference Waclawczyk, Nowak and Malinowski2022a

, Reference Waclawczyk, Nowak, Siebert and Malinowski2022b

) follow the exact same scaling:

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

in forced periodic turbulence (Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2015; Goto & Vassilicos Reference Goto and Vassilicos2016a

) and in atmospheric turbulence (Waclawczyk et al. Reference Waclawczyk, Nowak and Malinowski2022a

, Reference Waclawczyk, Nowak, Siebert and Malinowski2022b

) follow the exact same scaling:

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

increases as

$C_{\epsilon }$

increases as

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

decreases and

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

decreases and

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

decreases as

$C_{\epsilon }$

decreases as

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

increases following

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

increases following

![]() $C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

.

$C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

.

Whilst the non-equilibrium dissipation scaling

![]() $C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

seems to define a rather wide universality class of time fluctuations and streamwise profiles, it is not fully universal. A similar anticorrelation in time fluctuations of the Taylor length-based Reynolds number and various definitions of

$C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

seems to define a rather wide universality class of time fluctuations and streamwise profiles, it is not fully universal. A similar anticorrelation in time fluctuations of the Taylor length-based Reynolds number and various definitions of

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

was found in fully developed turbulent channel flow (Apostolidis, Laval & Vassilicos Reference Apostolidis, Laval and Vassilicos2022) but following a power law with slightly different exponents between

$C_{\epsilon }$

was found in fully developed turbulent channel flow (Apostolidis, Laval & Vassilicos Reference Apostolidis, Laval and Vassilicos2022) but following a power law with slightly different exponents between

![]() $-1$

and

$-1$

and

![]() $-3/2$

(depending on

$-3/2$

(depending on

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

definition and wall distance) as opposed to the

$C_{\epsilon }$

definition and wall distance) as opposed to the

![]() $-1$

exponent in

$-1$

exponent in

![]() $C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}} Re_{\lambda }^{-1}$

. It has also been claimed that the streamwise profiles of

$C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}} Re_{\lambda }^{-1}$

. It has also been claimed that the streamwise profiles of

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

and

$C_{\epsilon }$

and

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

(obtained from time and azimuthally averaged quantities) in a non-equilibrium region downstream of a slender rather than bluff body are related by

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

(obtained from time and azimuthally averaged quantities) in a non-equilibrium region downstream of a slender rather than bluff body are related by

![]() $C_{\varepsilon } \sim (\sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda })^{n}$

with

$C_{\varepsilon } \sim (\sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda })^{n}$

with

![]() $n=4/3$

rather than

$n=4/3$

rather than

![]() $n=1$

at high enough global Reynolds numbers (Ortiz-Tarin, Nidhan & Sarkar Reference Ortiz-Tarin, Nidhan and Sarkar2021).

$n=1$

at high enough global Reynolds numbers (Ortiz-Tarin, Nidhan & Sarkar Reference Ortiz-Tarin, Nidhan and Sarkar2021).

Opposite trends between local Reynolds number and local turbulence dissipation coefficient (i.e. one grows while the other one decays) is not found only in time fluctuations and streamwise profiles but also in transverse spatial profiles. This was shown by Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Cuvier, Foucaut, Ostovan and Vassilicos2021) and Alves-Portela & Vassilicos (Reference Alves-Portela and Vassilicos2022) who studied transverse profiles of time-average turbulent kinetic energy, turbulence dissipation rate and integral scale at various streamwise locations in three qualitatively different turbulent wakes of pairs of square prisms, in which case the reported power law exponent

![]() $n$

is between

$n$

is between

![]() $1.3$

and

$1.3$

and

![]() $1.5$

. There seems to be a qualitative universality in non-stationarity and non-homogeneity:

$1.5$

. There seems to be a qualitative universality in non-stationarity and non-homogeneity:

![]() $C_{\varepsilon }^{-1}$

is the ratio between the rate

$C_{\varepsilon }^{-1}$

is the ratio between the rate

![]() $k^{3/2}/L$

with which the large scales lose energy and the rate

$k^{3/2}/L$

with which the large scales lose energy and the rate

![]() $\epsilon$

with which the small scales dissipate energy, whereas

$\epsilon$

with which the small scales dissipate energy, whereas

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

is the ratio between the turbulent kinetic energy

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

is the ratio between the turbulent kinetic energy

![]() $k$

mostly in the large scales and the turbulent kinetic energy

$k$

mostly in the large scales and the turbulent kinetic energy

![]() $\sqrt {\nu \varepsilon }$

at the smallest scales (

$\sqrt {\nu \varepsilon }$

at the smallest scales (

![]() $\nu$

is the fluid’s kinematic viscosity). The universal property seems to be that, when

$\nu$

is the fluid’s kinematic viscosity). The universal property seems to be that, when

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

is not constant, these two ratios increase and decrease together, whether in time or space, in a wide range of turbulent flows. As already noted by Vassilicos & Laval (Reference Vassilicos and Laval2024), the strong anticorrelation or opposite trends between

$C_{\epsilon }$

is not constant, these two ratios increase and decrease together, whether in time or space, in a wide range of turbulent flows. As already noted by Vassilicos & Laval (Reference Vassilicos and Laval2024), the strong anticorrelation or opposite trends between

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

and

$C_{\epsilon }$

and

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

suggests that the turbulence non-equilibrium between

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

suggests that the turbulence non-equilibrium between

![]() $k^{3/2}/L$

and

$k^{3/2}/L$

and

![]() $\epsilon$

is self-regulating (the term ‘self-regulating’ in the context of the turbulence cascade was first used by Steiros Reference Steiros2021). When turbulent kinetic energy decays slower at the large scales than at the small scales, the rate of loss of energy grows faster at the large scales than at the small scales; and when turbulent kinetic energy decays faster at the large scales than at the small scales, the rate of loss of turbulent kinetic energy grows more slowly at the large scales than at the small scales. Kolmogorov equilibrium is not designed for non-stationary and/or non-homogeneous turbulence, yet some qualitative universality may exist for such non-equilibrium turbulence. Note that, even though the values of the exponent

$\epsilon$

is self-regulating (the term ‘self-regulating’ in the context of the turbulence cascade was first used by Steiros Reference Steiros2021). When turbulent kinetic energy decays slower at the large scales than at the small scales, the rate of loss of energy grows faster at the large scales than at the small scales; and when turbulent kinetic energy decays faster at the large scales than at the small scales, the rate of loss of turbulent kinetic energy grows more slowly at the large scales than at the small scales. Kolmogorov equilibrium is not designed for non-stationary and/or non-homogeneous turbulence, yet some qualitative universality may exist for such non-equilibrium turbulence. Note that, even though the values of the exponent

![]() $n$

reported till now in the literature are between approximately

$n$

reported till now in the literature are between approximately

![]() $1$

and

$1$

and

![]() $1.5$

, a priori any

$1.5$

, a priori any

![]() $n\gt 0$

satisfies the necessary condition for self-regulating non-equilibrium.

$n\gt 0$

satisfies the necessary condition for self-regulating non-equilibrium.

A couple of years ago, Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Koto, Nagata and Watanabe2023a

) and (Reference Zheng, Nakamura, Nagata and Watanabe2023b

) studied experimentally the time fluctuations of turbulence dissipation rate, integral scale and turbulent kinetic energy in the turbulence downstream of both regular and active grids. They demonstrated that these fluctuations are in self-regulating non-equilibrium both where the streamwise evolution of their time averages is self-regulating and where it is not. Earlier experiments by Mora et al. (Reference Mora, Muñiz Pladellorens, Riera Turró, Lagauzere and Obligado2019) and Zheng, Nagata & Watanabe (Reference Zheng, Nagata and Watanabe2021) had shown that

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

(obtained from long time averages) remains constant while

$C_{\epsilon }$

(obtained from long time averages) remains constant while

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

(also obtained from long time averages) decays along streamwise space in active grid-generated turbulence. Such absence of streamwise self-regulation also exists in regular grid-generated turbulence but only in the far field (Vassilicos Reference Vassilicos2015): upstream of this far field,

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

(also obtained from long time averages) decays along streamwise space in active grid-generated turbulence. Such absence of streamwise self-regulation also exists in regular grid-generated turbulence but only in the far field (Vassilicos Reference Vassilicos2015): upstream of this far field,

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

(obtained from long time averages) increases whilst

$C_{\epsilon }$

(obtained from long time averages) increases whilst

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

(also obtained from long time averages) decreases following

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

(also obtained from long time averages) decreases following

![]() $C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

in the streamwise direction. It does not matter whether the time fluctuations are probed in a region of grid-generated turbulence where streamwise variations follow

$C_{\varepsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

in the streamwise direction. It does not matter whether the time fluctuations are probed in a region of grid-generated turbulence where streamwise variations follow

![]() $C_{\epsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

or in a region where

$C_{\epsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

or in a region where

![]() $C_{\epsilon }$

remains constant as

$C_{\epsilon }$

remains constant as

![]() $ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

varies in the streamwise direction (streamwise variations for time average quantities), these time fluctuations are in self-regulating non-equilibrium and follow the same scaling

$ \textit{Re}_{\lambda }$

varies in the streamwise direction (streamwise variations for time average quantities), these time fluctuations are in self-regulating non-equilibrium and follow the same scaling

![]() $C_{\epsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

but in time, both in regular and active grid-generated turbulence (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Koto, Nagata and Watanabe2023a

, Reference Zheng, Nakamura, Nagata and Watanabe2023b

).

$C_{\epsilon } \sim \sqrt {Re_{G}}/Re_{\lambda }$

but in time, both in regular and active grid-generated turbulence (Zheng et al. Reference Zheng, Koto, Nagata and Watanabe2023a

, Reference Zheng, Nakamura, Nagata and Watanabe2023b

).

To our best knowledge, self-regulating non-equilibrium has never been studied experimentally in the turbulent wake of a slender rather than bluff body. In this paper we report analyses of high-speed stereo particle image velocimetry (SPIV) data taken in the turbulent wake of a 6 : 1 prolate spheroid with its principal axis aligned with the streamwise direction, the exact case of a slender body wake simulated with high-fidelity large eddy simulations by Ortiz-Tarin et al. (Reference Ortiz-Tarin, Nidhan and Sarkar2021). These authors found evidence of self-regulating non-equilibrium in streamwise profiles but did not study transverse profiles and time fluctuations at various positions in the flow. Our high-speed SPIV measurements are taken in transverse planes at four streamwise positions and we concentrate attention on self-regulating non-equilibrium in transverse profiles and time fluctuations at various spatial positions in the flow. Our study of time fluctuations follows the methodology introduced by Zheng et al. (Reference Zheng, Koto, Nagata and Watanabe2023a ) and (Reference Zheng, Nakamura, Nagata and Watanabe2023b ). As explained in § 4.4, this methodology presents the important advantage of plotting quantities in a way that significantly increases signal to noise ratio. Additionally, the high-speed nature of our spatially resolved SPIV can be exploited for noise reduction of turbulence dissipation rate estimates. This denoising procedure is detailed in § 2.

The paper is organised as follows. The experimental procedure is presented in § 2 and a detailed characterisation of the flow is given in § 3. Spatial profiles and time fluctuations of turbulence dissipation rate, turbulent kinetic energy and integral scales are studied in § 4, where a detailed assessment of self-regulating non-equilibrium is made. Our main conclusions are summarised in § 5.

2. Experimental methodology

Experiments on the wake of a 6 : 1 prolate spheroid were conducted in the LMFL wind tunnel (see Carlier & Stanislas Reference Carlier and Stanislas2005 for details). The 6 : 1 prolate spheroid’s diameter at its centre (

![]() $x,y,z=$

0) is 80 mm and its length along the principal axis is 480 mm. Experiments were conducted with inlet velocity

$x,y,z=$

0) is 80 mm and its length along the principal axis is 480 mm. Experiments were conducted with inlet velocity

![]() $U_{0} = 9$

m sec

$U_{0} = 9$

m sec

![]() $^{-1}$

and an inlet Reynolds number

$^{-1}$

and an inlet Reynolds number

![]() $ \textit{Re} (\equiv U_{0} D/\nu )$

equal to

$ \textit{Re} (\equiv U_{0} D/\nu )$

equal to

![]() $4.8 \times 10^{4}$

. The inlet velocity and the spheroid’s principal axis are aligned with the streamwise (

$4.8 \times 10^{4}$

. The inlet velocity and the spheroid’s principal axis are aligned with the streamwise (

![]() $x$

) direction. The

$x$

) direction. The

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

directions are shown in the schematic of the experimental set-up in figure 1.

$z$

directions are shown in the schematic of the experimental set-up in figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic of the experimental measurement set-up for stereo-PIV measurement.

Single-point hot-wire anemometry (HWA) and high-speed SPIV measurements were performed at four streamwise locations that are

![]() $x/D=$

19.54, 31, 40 and 51.6. The HWA measurements were performed on the geometric centreline (

$x/D=$

19.54, 31, 40 and 51.6. The HWA measurements were performed on the geometric centreline (

![]() $y,z=0$

) only and the resulting centreline isotropic surrogate of the turbulent dissipation rate

$y,z=0$

) only and the resulting centreline isotropic surrogate of the turbulent dissipation rate

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

$\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

![]() $\equiv {15 \nu }/{\bar {U}^2} \overline { ( {\partial u^\prime }/{\partial t} )^2}$

(assuming small-scale isotropy and Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis,

$\equiv {15 \nu }/{\bar {U}^2} \overline { ( {\partial u^\prime }/{\partial t} )^2}$

(assuming small-scale isotropy and Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis,

![]() $\bar {U}$

being the streamwise mean velocity at the spatial location where the measurement is made) and Kolmogorov length

$\bar {U}$

being the streamwise mean velocity at the spatial location where the measurement is made) and Kolmogorov length

![]() $\eta _k = (\nu ^{3}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w})^{1/4}$

are given in table 1 (

$\eta _k = (\nu ^{3}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w})^{1/4}$

are given in table 1 (

![]() $\nu$

is the fluid’s kinematic viscosity). Stereo-PIV provided measurements of the three components of velocity,

$\nu$

is the fluid’s kinematic viscosity). Stereo-PIV provided measurements of the three components of velocity,

![]() $u$

(

$u$

(

![]() $x$

direction),

$x$

direction),

![]() $v$

(

$v$

(

![]() $y$

direction) and

$y$

direction) and

![]() $w$

(

$w$

(

![]() $z$

direction), by using two cameras focused on the common measurement region and a high-speed laser. The schematic of the experimental set-up with the laser and the two cameras recording images in the transverse

$z$

direction), by using two cameras focused on the common measurement region and a high-speed laser. The schematic of the experimental set-up with the laser and the two cameras recording images in the transverse

![]() $y{-}z$

plane (normal to the streamwise direction) is shown in figure 1. Note that the recording in forward scattering mode ensures maximum illumination of seeding particles at the camera sensor.

$y{-}z$

plane (normal to the streamwise direction) is shown in figure 1. Note that the recording in forward scattering mode ensures maximum illumination of seeding particles at the camera sensor.

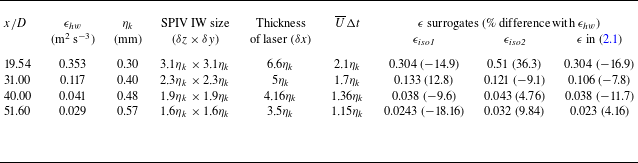

Table 1. Turbulence kinetic energy dissipation rate measurement parameters and estimations on the centreline. Here,

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

is the turbulent dissipation rate calculated on the geometric centreline of the wake from HWA and

$\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

is the turbulent dissipation rate calculated on the geometric centreline of the wake from HWA and

![]() $\eta _k$

is

$\eta _k$

is

![]() $(\nu ^3/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w})^4$

. The averaging size of the IW,

$(\nu ^3/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w})^4$

. The averaging size of the IW,

![]() $\delta x$

,

$\delta x$

,

![]() $\delta y$

and

$\delta y$

and

![]() $\delta z$

, is stated in terms of

$\delta z$

, is stated in terms of

![]() $\eta _k$

.

$\eta _k$

.

The SPIV measurements were high speed and performed at 14 kHz by using two lasers at 7 kHz each (the time

![]() $\Delta t$

between consecutive images is such that

$\Delta t$

between consecutive images is such that

![]() $1/\Delta t = 14$

kHz). An Nd:YLF laser from Quantronix with M

$1/\Delta t = 14$

kHz). An Nd:YLF laser from Quantronix with M

![]() $^2$

(beam quality) around 20 and two CMOS cameras (Phantom 340) of 10

$^2$

(beam quality) around 20 and two CMOS cameras (Phantom 340) of 10

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m pixels sensor size were used in the SPIV measurement. The laser sheet was 2 mm thick and ensured sufficient overlap of seeding particles for the SPIV cross-correlation. The wake deficit region grows with streamwise distance. As a result, larger fields of view are needed further downstream. At

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m pixels sensor size were used in the SPIV measurement. The laser sheet was 2 mm thick and ensured sufficient overlap of seeding particles for the SPIV cross-correlation. The wake deficit region grows with streamwise distance. As a result, larger fields of view are needed further downstream. At

![]() $x/D=19.54$

the field of view is

$x/D=19.54$

the field of view is

![]() $72$

mm long (in the

$72$

mm long (in the

![]() $z$

direction) and

$z$

direction) and

![]() $8.8$

mm wide (in the

$8.8$

mm wide (in the

![]() $y$

direction), but an additional SPIV measurement plane with an offset of

$y$

direction), but an additional SPIV measurement plane with an offset of

![]() $z=+60$

mm was also recorded at

$z=+60$

mm was also recorded at

![]() $x/D$

= 31.00, 40.00 and 51.60 as shown in figure 1. Hence, at

$x/D$

= 31.00, 40.00 and 51.60 as shown in figure 1. Hence, at

![]() $x/D =19.54$

the field of view is made of one measurement plane and covers the coordinates

$x/D =19.54$

the field of view is made of one measurement plane and covers the coordinates

![]() $y = [-4$

to

$y = [-4$

to

![]() $4]$

mm and

$4]$

mm and

![]() $z = [-6.2$

to

$z = [-6.2$

to

![]() $65.8]$

mm whereas at

$65.8]$

mm whereas at

![]() $x/D$

= 31.00, 40.00 and 51.60 the field of view is made of two measurement planes and covers the coordinates

$x/D$

= 31.00, 40.00 and 51.60 the field of view is made of two measurement planes and covers the coordinates

![]() $y = [-4$

to

$y = [-4$

to

![]() $4]$

mm and

$4]$

mm and

![]() $z = [-6.2$

to

$z = [-6.2$

to

![]() $125.8]$

mm.

$125.8]$

mm.

Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis has been used in this paper both on HWA and SPIV data. It states that if the turbulent eddies have not significantly evolved as they advect, the streamwise velocity derivative can be approximated from the temporal derivative, i.e.

![]() $(\partial /\partial x) = (1/\bar {U}) \boldsymbol{\cdot }(\partial /\partial t)$

. For Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis to be valid, the turbulence intensity should be below

$(\partial /\partial x) = (1/\bar {U}) \boldsymbol{\cdot }(\partial /\partial t)$

. For Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis to be valid, the turbulence intensity should be below

![]() $10\,\%\hbox{--}15\,\%$

and the mean streamwise velocity component (

$10\,\%\hbox{--}15\,\%$

and the mean streamwise velocity component (

![]() $x$

direction here) should be much larger than the mean transverse velocity components (

$x$

direction here) should be much larger than the mean transverse velocity components (

![]() $y$

$y$

![]() ${\textrm{and}}$

${\textrm{and}}$

![]() $z$

directions here); see, for example, Gledzer (Reference Gledzer1997) and references therein. Throughout our PIV measurement regions (which include the geometric centreline where HWA measurements were made), the mean streamwise velocity was an order of magnitude larger than the mean transverse velocities, and turbulent velocity was also below or at most 2.5

$z$

directions here); see, for example, Gledzer (Reference Gledzer1997) and references therein. Throughout our PIV measurement regions (which include the geometric centreline where HWA measurements were made), the mean streamwise velocity was an order of magnitude larger than the mean transverse velocities, and turbulent velocity was also below or at most 2.5

![]() $\%$

of the mean velocity (see also figure 3(b) noting that the centreline streamwise mean velocity deficit

$\%$

of the mean velocity (see also figure 3(b) noting that the centreline streamwise mean velocity deficit

![]() $U_d$

is an order of magnitude smaller than

$U_d$

is an order of magnitude smaller than

![]() $\bar {U}$

). Out-of-plane derivatives (

$\bar {U}$

). Out-of-plane derivatives (

![]() $\partial /\partial x$

) were therefore calculated from temporal derivatives (

$\partial /\partial x$

) were therefore calculated from temporal derivatives (

![]() $\partial /\partial t$

) by using Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis. (Since we are using two distinct lasers (each at 7 KHz to get 14 KHz acquisition), temporal derivatives are calculated using a central differencing scheme over the time interval

$\partial /\partial t$

) by using Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis. (Since we are using two distinct lasers (each at 7 KHz to get 14 KHz acquisition), temporal derivatives are calculated using a central differencing scheme over the time interval

![]() $2\Delta t$

. This ensures that the same laser is used in temporal derivative calculations, which avoids errors on derivative calculations caused by minor differences in the two distinct laser characteristics.)

$2\Delta t$

. This ensures that the same laser is used in temporal derivative calculations, which avoids errors on derivative calculations caused by minor differences in the two distinct laser characteristics.)

The study of self-regulating non-equilibrium requires measurements of turbulent kinetic energies, integral scales and turbulent dissipation rates. Stereo-PIV allows access to the full turbulent kinetic energy in the entire field of view. Fields of integral scales are obtained as described at the start of § 4 by integrating autocorrelation functions over time. Accurate estimation of derivatives of fluctuating velocities at high spatial resolution is required for extracting turbulence dissipation rates from our data given

\begin{align} \epsilon =& \nu \left ( 2 \left [ \overline { \left (\frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial x}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial y}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial z}\right )^2 } \right ] + 2 \left [ \overline { \frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial y} \frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial x} } + \overline { \frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial z} \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial x} } + \overline { \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial y} \frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial z} } \right ] \right. \notag \\& \left. + \left [ \overline { \left (\frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial y}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial x}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial z}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial x}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial z}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial y}\right )^2 } \right ] \right)\!, \end{align}

\begin{align} \epsilon =& \nu \left ( 2 \left [ \overline { \left (\frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial x}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial y}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial z}\right )^2 } \right ] + 2 \left [ \overline { \frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial y} \frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial x} } + \overline { \frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial z} \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial x} } + \overline { \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial y} \frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial z} } \right ] \right. \notag \\& \left. + \left [ \overline { \left (\frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial y}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial x}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial z}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial x}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial v^\prime }{\partial z}\right )^2 } + \overline { \left (\frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial y}\right )^2 } \right ] \right)\!, \end{align}

where the overbars signify time averaging and

![]() $u'$

,

$u'$

,

![]() $v'$

and

$v'$

and

![]() $w'$

are the fluctuating velocities obtained from

$w'$

are the fluctuating velocities obtained from

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

, respectively, after Reynolds decomposition. For statistical convergence of our statistics, at all four

$w$

, respectively, after Reynolds decomposition. For statistical convergence of our statistics, at all four

![]() $x/D$

positions of our measurements, we recorded 66 experimental runs each having a recording time of 3 sec and have checked that all the statistics presented in this paper are fully converged.

$x/D$

positions of our measurements, we recorded 66 experimental runs each having a recording time of 3 sec and have checked that all the statistics presented in this paper are fully converged.

Images with a mean spatial resolution of

![]() $52$

$52$

![]() $\unicode{x03BC}$

m pixel size are processed with an in-house four-pass adaptive window PIV processing method (detailed in Beaumard et al. (Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024)). This PIV processing results in a velocity field that is averaged over an interrogation window (IW) of size 16

$\unicode{x03BC}$

m pixel size are processed with an in-house four-pass adaptive window PIV processing method (detailed in Beaumard et al. (Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024)). This PIV processing results in a velocity field that is averaged over an interrogation window (IW) of size 16

![]() $\times$

24 pixels and an overlap of around 58

$\times$

24 pixels and an overlap of around 58

![]() $\%$

. A Cubic b-spline interpolation using grey level and bilinear interpolation image deformation (Scarano Reference Scarano2001; Lecordier & Trinite Reference Lecordier and Trinite2004) was also used before the final pass. The model described in Soloff, Adrian & Liu (Reference Soloff, Adrian and Liu1997) was used to calculate the magnitude of all three components of velocity from two planar PIV results from two cameras. To account for corrections due to misalignment between the light sheet and the calibration plane, the self-calibration correction method (Coudert & Schon Reference Coudert and Schon2001; Wieneke Reference Wieneke2005) is also used in the SPIV processing. The IW size in terms of

$\%$

. A Cubic b-spline interpolation using grey level and bilinear interpolation image deformation (Scarano Reference Scarano2001; Lecordier & Trinite Reference Lecordier and Trinite2004) was also used before the final pass. The model described in Soloff, Adrian & Liu (Reference Soloff, Adrian and Liu1997) was used to calculate the magnitude of all three components of velocity from two planar PIV results from two cameras. To account for corrections due to misalignment between the light sheet and the calibration plane, the self-calibration correction method (Coudert & Schon Reference Coudert and Schon2001; Wieneke Reference Wieneke2005) is also used in the SPIV processing. The IW size in terms of

![]() $\eta _k$

is stated in table 1. For estimation of

$\eta _k$

is stated in table 1. For estimation of

![]() $\epsilon$

, a spatial resolution (i.e. IW size) of around

$\epsilon$

, a spatial resolution (i.e. IW size) of around

![]() $4\eta _k$

or below is usually considered sufficient (see Lavoie et al. Reference Lavoie, Avallone, De Gregorio, Romano and Antonia2007; Tokgoz et al. Reference Tokgoz, Elsinga, Delfos and Westerweel2012; Laizet, Nedić & Vassilicos Reference Laizet, Nedić and Vassilicos2015). Our transverse plane spatial resolutions

$4\eta _k$

or below is usually considered sufficient (see Lavoie et al. Reference Lavoie, Avallone, De Gregorio, Romano and Antonia2007; Tokgoz et al. Reference Tokgoz, Elsinga, Delfos and Westerweel2012; Laizet, Nedić & Vassilicos Reference Laizet, Nedić and Vassilicos2015). Our transverse plane spatial resolutions

![]() $\delta z$

and

$\delta z$

and

![]() $\delta y$

are all below

$\delta y$

are all below

![]() $4\eta _k$

, as can seen in table 1.

$4\eta _k$

, as can seen in table 1.

The thickness of the laser sheet is such that the IW size

![]() $\delta x$

in the streamwise direction varies from

$\delta x$

in the streamwise direction varies from

![]() $6.6\eta _k$

to

$6.6\eta _k$

to

![]() $3.5\eta _k$

with increasing

$3.5\eta _k$

with increasing

![]() $x/D$

measurement position (see table 1). However, Zaripov, Li & Dushin (Reference Zaripov, Li and Dushin2019) have demonstrated in a turbulent boundary layer that the turbulence dissipation rate can be estimated sufficiently accurately with a IW size larger in the direction of smallest variation (streamwise here) than in the other directions.

$x/D$

measurement position (see table 1). However, Zaripov, Li & Dushin (Reference Zaripov, Li and Dushin2019) have demonstrated in a turbulent boundary layer that the turbulence dissipation rate can be estimated sufficiently accurately with a IW size larger in the direction of smallest variation (streamwise here) than in the other directions.

The small-scale resolution of our SPIV is necessary but not sufficient to ensure accurate

![]() $\epsilon$

estimation because of the noise contamination of the measured velocities. One of the major sources of noise results from the approximation of the location of the seeding particles in the pixelised images (as explained in the supplementary material of Beaumard et al. Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024). To eliminate this noise in the estimation of

$\epsilon$

estimation because of the noise contamination of the measured velocities. One of the major sources of noise results from the approximation of the location of the seeding particles in the pixelised images (as explained in the supplementary material of Beaumard et al. Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024). To eliminate this noise in the estimation of

![]() $\epsilon$

, Beaumard et al. (Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024) proposed the use of high-speed PIV (or SPIV in our case) and calculation of squares of fluctuating velocity derivatives as products of fluctuating velocity derivatives at the same location but nearby times. Beaumard et al. (Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024) argued that the noise in these derivatives taken at the same location decorrelates very quickly with time whereas the signal does not. Hence, if the time separation is small enough for the signal to remain effectively the same but large enough for the noise to decorrelate sharply, the products of fluctuating velocity derivatives at nearby times will be suitably denoised estimates of squares of fluctuating velocity derivatives (see also George & Stanislas Reference George and Stanislas2021).

$\epsilon$

, Beaumard et al. (Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024) proposed the use of high-speed PIV (or SPIV in our case) and calculation of squares of fluctuating velocity derivatives as products of fluctuating velocity derivatives at the same location but nearby times. Beaumard et al. (Reference Beaumard, Bragança, Cuvier, Steiros and Vassilicos2024) argued that the noise in these derivatives taken at the same location decorrelates very quickly with time whereas the signal does not. Hence, if the time separation is small enough for the signal to remain effectively the same but large enough for the noise to decorrelate sharply, the products of fluctuating velocity derivatives at nearby times will be suitably denoised estimates of squares of fluctuating velocity derivatives (see also George & Stanislas Reference George and Stanislas2021).

To find the small time separation

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t$

that is appropriate for denoising squares of velocity derivatives obtained from SPIV, we compare the isotropic surrogate

$n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t$

that is appropriate for denoising squares of velocity derivatives obtained from SPIV, we compare the isotropic surrogate

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

of the turbulence dissipation rate obtained from the HWA with two isotropic surrogates of the turbulence dissipation rate

$\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

of the turbulence dissipation rate obtained from the HWA with two isotropic surrogates of the turbulence dissipation rate

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

and

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

and

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

obtained from SPIV on the basis of (2.2):

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

obtained from SPIV on the basis of (2.2):

\begin{align} \epsilon _{\textit{iso1}} =& \frac {15 \nu }{\bar {U}^2} \left [\overline { \left ( \frac { \partial u^\prime }{\partial t} \right )_t \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left ( \frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial t}\right )_{ (t+ n_{\textit{sep}}\Delta t)}} \right ]\!; \notag \\\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}} =& 15 \nu \left [ \overline { \left (- \frac { \partial v^\prime }{\partial y}- \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial z} \right )_t \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left (- \frac { \partial v^\prime }{\partial y}- \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial z} \right )_{t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t} } \right ] \! . \end{align}

\begin{align} \epsilon _{\textit{iso1}} =& \frac {15 \nu }{\bar {U}^2} \left [\overline { \left ( \frac { \partial u^\prime }{\partial t} \right )_t \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left ( \frac {\partial u^\prime }{\partial t}\right )_{ (t+ n_{\textit{sep}}\Delta t)}} \right ]\!; \notag \\\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}} =& 15 \nu \left [ \overline { \left (- \frac { \partial v^\prime }{\partial y}- \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial z} \right )_t \boldsymbol{\cdot }\left (- \frac { \partial v^\prime }{\partial y}- \frac {\partial w^\prime }{\partial z} \right )_{t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t} } \right ] \! . \end{align}

The isotropic surrogate

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

is obtained by time averaging the product of

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

is obtained by time averaging the product of

![]() $ ( { \partial u^\prime }/{\partial t} )_t$

at time

$ ( { \partial u^\prime }/{\partial t} )_t$

at time

![]() $t$

with

$t$

with

![]() $ ( { \partial u^\prime }/{\partial t} )_{t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t}$

at time

$ ( { \partial u^\prime }/{\partial t} )_{t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t}$

at time

![]() $t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t$

; and the isotropic surrogate

$t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t$

; and the isotropic surrogate

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

is calculated by time averaging the product of

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

is calculated by time averaging the product of

![]() $ (- ({ \partial v^\prime }/{\partial y})- ({\partial w^\prime }/{\partial z}) )_t$

at time

$ (- ({ \partial v^\prime }/{\partial y})- ({\partial w^\prime }/{\partial z}) )_t$

at time

![]() $t$

with

$t$

with

![]() $(- ({ \partial v^\prime }/{\partial y})- ({\partial w^\prime }/{\partial z}) )_{t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t}$

at time

$(- ({ \partial v^\prime }/{\partial y})- ({\partial w^\prime }/{\partial z}) )_{t+n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t}$

at time

![]() $t+n_{\textit{sep}}\Delta t$

. The quantity

$t+n_{\textit{sep}}\Delta t$

. The quantity

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

is an estimate of

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

is an estimate of

![]() $\epsilon$

based on the hypothesis of small-scale isotropy and Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis. The quantity

$\epsilon$

based on the hypothesis of small-scale isotropy and Taylor’s frozen turbulence hypothesis. The quantity

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

is an estimate of

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

is an estimate of

![]() $\epsilon$

based on the hypothesis of small-scale isotropy and continuity. Whilst there is of course some uncertainty in the HWA estimate of the isotropic surrogate of

$\epsilon$

based on the hypothesis of small-scale isotropy and continuity. Whilst there is of course some uncertainty in the HWA estimate of the isotropic surrogate of

![]() $\epsilon$

, it is not as high as the uncertainty caused by the noise in the location of seeding particles in PIV’s or SPIV’s pixelated images. Indeed, setting

$\epsilon$

, it is not as high as the uncertainty caused by the noise in the location of seeding particles in PIV’s or SPIV’s pixelated images. Indeed, setting

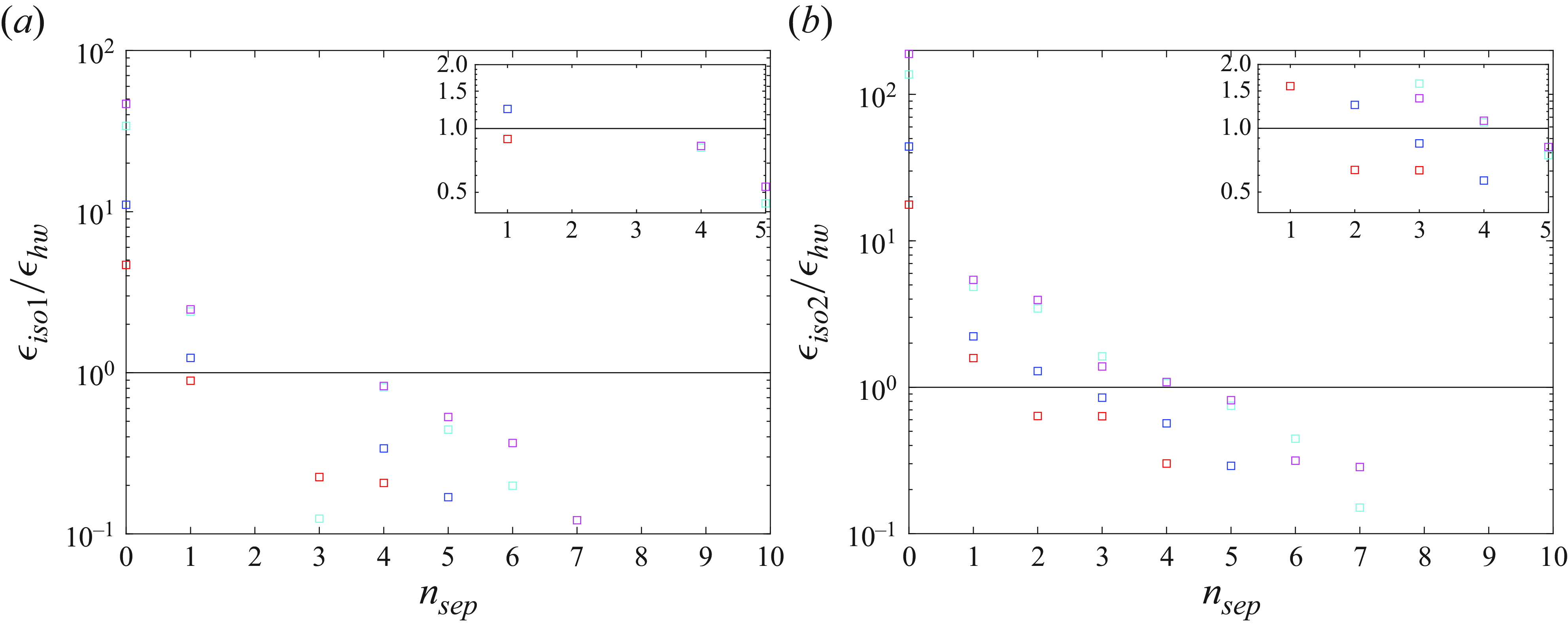

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=0$

leads to order of magnitude differences between

$n_{\textit{sep}}=0$

leads to order of magnitude differences between

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

and either

$\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

and either

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

or

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

or

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

as can be seen in figure 2. This difference drops dramatically for

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

as can be seen in figure 2. This difference drops dramatically for

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

as can also be seen in figure 2 where we plot the ratios

$n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

as can also be seen in figure 2 where we plot the ratios

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

(panel a) and

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

(panel a) and

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

(panel b) versus

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

(panel b) versus

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}$

. As

$n_{\textit{sep}}$

. As

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}$

increases, these ratios decrease towards

$n_{\textit{sep}}$

increases, these ratios decrease towards

![]() $0$

because they increasingly sample the decorrelation in the actual velocity derivative signal itself rather than just in the noise. Note that there are no data for

$0$

because they increasingly sample the decorrelation in the actual velocity derivative signal itself rather than just in the noise. Note that there are no data for

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=2$

in figure 2(a). This is because streamwise derivatives are calculated using a central difference scheme and there can be common velocity components in derivative calculations leading to spurious correlations between velocity gradients at times

$n_{\textit{sep}}=2$

in figure 2(a). This is because streamwise derivatives are calculated using a central difference scheme and there can be common velocity components in derivative calculations leading to spurious correlations between velocity gradients at times

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}\Delta t=2\Delta t$

apart.

$n_{\textit{sep}}\Delta t=2\Delta t$

apart.

Figure 2. (a,b) Comparisons of isotropic surrogates of turbulence dissipation rate from SPIV with

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

from HWA for various temporal separations

$\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

from HWA for various temporal separations

![]() $n\Delta t$

. The results at

$n\Delta t$

. The results at

![]() $x/D$

= 19.54, 31.00, 40.0 and 51.6 are shown with

$x/D$

= 19.54, 31.00, 40.0 and 51.6 are shown with

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() symbols, respectively.

symbols, respectively.

Looking at the two plots (and their inserts) in figure 2 we first see that with

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

(for which

$n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

(for which

![]() $\bar {U} n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t/\eta _k$

is between 2.1 and 1.15 depending on

$\bar {U} n_{\textit{sep}} \Delta t/\eta _k$

is between 2.1 and 1.15 depending on

![]() $x/D$

; see table 1), the noise in the SPIV estimates is significantly reduced and their order of magnitude is correct at all streamwise locations. For the first two streamwise locations,

$x/D$

; see table 1), the noise in the SPIV estimates is significantly reduced and their order of magnitude is correct at all streamwise locations. For the first two streamwise locations,

![]() $x/D=19.54$

and

$x/D=19.54$

and

![]() $31.00$

,

$31.00$

,

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

is enough for

$n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

is enough for

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

to be near-equal to

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}$

to be near-equal to

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

, whereas

$\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

, whereas

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=4$

is significantly better for the further two locations, i.e.

$n_{\textit{sep}}=4$

is significantly better for the further two locations, i.e.

![]() $x/D=40.00$

and

$x/D=40.00$

and

![]() $51.60$

. Similar behaviour is observed for

$51.60$

. Similar behaviour is observed for

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

except that the best value of

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}$

except that the best value of

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}$

is now 3 rather than 1 at

$n_{\textit{sep}}$

is now 3 rather than 1 at

![]() $x/D=31.00$

. A reason for time separations larger than

$x/D=31.00$

. A reason for time separations larger than

![]() $\Delta t$

, i.e.

$\Delta t$

, i.e.

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}$

strictly larger than 1, required in some locations may be the larger noise-to-signal ratio as discussed in Appendix A. From the IW sizes (

$n_{\textit{sep}}$

strictly larger than 1, required in some locations may be the larger noise-to-signal ratio as discussed in Appendix A. From the IW sizes (

![]() $\delta x$

) and streamwise separations (

$\delta x$

) and streamwise separations (

![]() $\bar {U}\Delta t$

) in table 1, it is evident that after

$\bar {U}\Delta t$

) in table 1, it is evident that after

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=3$

there is no overlap between IWs and, therefore, complete denoising is possible if the turbulent velocity derivatives remain highly correlated as appears to be the case in streamwise locations

$n_{\textit{sep}}=3$

there is no overlap between IWs and, therefore, complete denoising is possible if the turbulent velocity derivatives remain highly correlated as appears to be the case in streamwise locations

![]() $x/D=40.00$

and

$x/D=40.00$

and

![]() $x/D=51.6$

; see figure 2. In all our locations, whether

$x/D=51.6$

; see figure 2. In all our locations, whether

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}$

equals 1, 3 or 4, it is such that

$n_{\textit{sep}}$

equals 1, 3 or 4, it is such that

![]() $\bar {U} n \Delta t/\eta _k$

is between 2 and 5. The ratios

$\bar {U} n \Delta t/\eta _k$

is between 2 and 5. The ratios

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

and

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

and

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

drop below 1 at normalised time separations

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

drop below 1 at normalised time separations

![]() $\bar {U} n \Delta t/\eta _k$

larger than 5 or 6, suggesting that the signal starts to decorrelate at such time separations. However, as we have just seen, the noise decorrelates dramatically at time separations smaller than that, i.e.

$\bar {U} n \Delta t/\eta _k$

larger than 5 or 6, suggesting that the signal starts to decorrelate at such time separations. However, as we have just seen, the noise decorrelates dramatically at time separations smaller than that, i.e.

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

,

$n_{\textit{sep}}=1$

,

![]() $3$

or

$3$

or

![]() $4$

.

$4$

.

From the results for

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

in figure 2, it can be inferred that the streamwise derivatives

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso1}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

in figure 2, it can be inferred that the streamwise derivatives

![]() $( ( \partial u^{\prime}_{i} ) / ( \partial x) )^2$

(for all velocities that are obtained here from our SPIV using Taylor’s hypothesis) can be denoised with time separations

$( ( \partial u^{\prime}_{i} ) / ( \partial x) )^2$

(for all velocities that are obtained here from our SPIV using Taylor’s hypothesis) can be denoised with time separations

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}} =$

1, 1, 4 and 4 for locations

$n_{\textit{sep}} =$

1, 1, 4 and 4 for locations

![]() $x/D=$

19.54, 31.00, 41.00 and 51.6, respectively. Similarly from the results for

$x/D=$

19.54, 31.00, 41.00 and 51.6, respectively. Similarly from the results for

![]() $\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

, it can be inferred that the transverse derivatives

$\epsilon _{\textit{iso2}}/\epsilon _{\textit{h}w}$

, it can be inferred that the transverse derivatives

![]() $( ( \partial u^{\prime}_{i} ) / ( \partial y) )^2$

and

$( ( \partial u^{\prime}_{i} ) / ( \partial y) )^2$

and

![]() $( ( \partial u^{\prime}_{i} ) / ( \partial z) )^2$

obtained from our SPIV can be denoised with time separations

$( ( \partial u^{\prime}_{i} ) / ( \partial z) )^2$

obtained from our SPIV can be denoised with time separations

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}} =$

1, 3, 4 and 4 for locations

$n_{\textit{sep}} =$

1, 3, 4 and 4 for locations

![]() $x/D=$

19.54, 31.00, 41.00 and 51.6, respectively. In calculating

$x/D=$

19.54, 31.00, 41.00 and 51.6, respectively. In calculating

![]() $\epsilon$

, all the terms in (2.1) were denoised with separations

$\epsilon$

, all the terms in (2.1) were denoised with separations

![]() $n_{\textit{sep}}$

as explained above. We show in the following section that transverse profiles of

$n_{\textit{sep}}$

as explained above. We show in the following section that transverse profiles of

![]() $\epsilon$

obtained this way conform with expectations. An additional way to increase signal-to-noise ratio, specific to time fluctuations of turbulence dissipation, is presented and used successfully in the third paragraph of § 4.4.

$\epsilon$

obtained this way conform with expectations. An additional way to increase signal-to-noise ratio, specific to time fluctuations of turbulence dissipation, is presented and used successfully in the third paragraph of § 4.4.

3. Characterisation of the flow

3.1. Velocity statistics

The transverse (along

![]() $z$

) variation of the time-averaged streamwise velocity

$z$

) variation of the time-averaged streamwise velocity

![]() $\bar {U}$

at

$\bar {U}$

at

![]() $y=0$

is shown in figure 3(a). The

$y=0$

is shown in figure 3(a). The

![]() $5\,\%$

discontinuity in

$5\,\%$

discontinuity in

![]() $\bar {U}$

observed in this plot for

$\bar {U}$

observed in this plot for

![]() $x/D =$

31.00, 40.00 and 51.60 occurs in the merging region of the two measurement planes. At the last three streamwise locations, two distinct SPIV measurements were performed at different times (see figure 1), therefore, manual misalignment of distinct SPIV measurements, optical error due to distortion at the edges of the recording cameras and/or calibration differences can cause this discontinuity that is customary in such dual SPIV set-ups. The mean flow velocity

$x/D =$

31.00, 40.00 and 51.60 occurs in the merging region of the two measurement planes. At the last three streamwise locations, two distinct SPIV measurements were performed at different times (see figure 1), therefore, manual misalignment of distinct SPIV measurements, optical error due to distortion at the edges of the recording cameras and/or calibration differences can cause this discontinuity that is customary in such dual SPIV set-ups. The mean flow velocity

![]() $\bar {U}$

increases in the streamwise and transverse directions. Even in the region

$\bar {U}$

increases in the streamwise and transverse directions. Even in the region

![]() $z/D \gt 1.2$

, where the

$z/D \gt 1.2$

, where the

![]() $\bar {U}$

profile is approximately uniform in

$\bar {U}$

profile is approximately uniform in

![]() $z$

,

$z$

,

![]() $\bar {U}$

increases slightly with streamwise direction. This increase in

$\bar {U}$

increases slightly with streamwise direction. This increase in

![]() $\bar {U}$

is due to the increase in the effective blockage caused by the growth of the boundary layers at the walls of the wind tunnel. However, the streamwise increase of

$\bar {U}$

is due to the increase in the effective blockage caused by the growth of the boundary layers at the walls of the wind tunnel. However, the streamwise increase of

![]() $\bar {U}$

on the wake’s geometric centreline is even greater (see figure 3) so that the mean deficit velocity decreases with streamwise distance. The wake half-width

$\bar {U}$

on the wake’s geometric centreline is even greater (see figure 3) so that the mean deficit velocity decreases with streamwise distance. The wake half-width

![]() $b(x)$

is defined as the transverse distance

$b(x)$

is defined as the transverse distance

![]() $z=b(x)$

where the mean velocity deficit has dropped to half its value at the geometrical centre

$z=b(x)$

where the mean velocity deficit has dropped to half its value at the geometrical centre

![]() $z=0$

, and it is used to normalise the transverse distance

$z=0$

, and it is used to normalise the transverse distance

![]() $z$

in our plots.

$z$

in our plots.

Transverse profiles (along

![]() $z/b$

) of normalised turbulent stresses

$z/b$

) of normalised turbulent stresses

![]() $(\overline {u^\prime _i u^\prime _j }/U_d^2)$

, (

$(\overline {u^\prime _i u^\prime _j }/U_d^2)$

, (

![]() $u^{\prime}_{i} \equiv u_i{-} \bar {u_i}$

, where the overbar signifies time averaging and

$u^{\prime}_{i} \equiv u_i{-} \bar {u_i}$

, where the overbar signifies time averaging and

![]() $U_d$

is the centreline streamwise mean velocity deficit) are also shown in figure 3(b,c). Similar to the mean flow profile, errors (less than 16

$U_d$

is the centreline streamwise mean velocity deficit) are also shown in figure 3(b,c). Similar to the mean flow profile, errors (less than 16

![]() $\%$

) in the merging region of the two planes are also present in the turbulent stress profile. Just like other canonical free turbulent shear flows, for example, jets (Cafiero & Vassilicos Reference Cafiero and Vassilicos2019) and wakes (Alves Portela, Papadakis & Vassilicos Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2018; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Cuvier, Foucaut, Ostovan and Vassilicos2021), the normal turbulent stresses are anisotropic, i.e.

$\%$

) in the merging region of the two planes are also present in the turbulent stress profile. Just like other canonical free turbulent shear flows, for example, jets (Cafiero & Vassilicos Reference Cafiero and Vassilicos2019) and wakes (Alves Portela, Papadakis & Vassilicos Reference Alves Portela, Papadakis and Vassilicos2018; Chen et al. Reference Chen, Cuvier, Foucaut, Ostovan and Vassilicos2021), the normal turbulent stresses are anisotropic, i.e.

![]() $\overline {u^\prime u^\prime }$

is typically larger than both

$\overline {u^\prime u^\prime }$

is typically larger than both

![]() $\overline {v^\prime v^\prime }$

and

$\overline {v^\prime v^\prime }$

and

![]() $\overline {w^\prime w^\prime }$

. However, unlike bluff body wakes that are axisymmetric, the wake of our prolate spheroid is not axisymmetric around the prolate spheroid’s streamwise axis of symmetry even though it is aligned with the incoming flow. Indeed, figure 3(b,c) shows

$\overline {w^\prime w^\prime }$

. However, unlike bluff body wakes that are axisymmetric, the wake of our prolate spheroid is not axisymmetric around the prolate spheroid’s streamwise axis of symmetry even though it is aligned with the incoming flow. Indeed, figure 3(b,c) shows

![]() $\overline {v^\prime v^\prime } \neq \overline {w^\prime w^\prime }$

and

$\overline {v^\prime v^\prime } \neq \overline {w^\prime w^\prime }$

and

![]() $\overline {u^\prime v^\prime } \neq \overline {u^\prime w^\prime }$

. Whilst

$\overline {u^\prime v^\prime } \neq \overline {u^\prime w^\prime }$

. Whilst

![]() $\overline {u^\prime v^\prime }$

and

$\overline {u^\prime v^\prime }$

and

![]() $\overline {v^\prime w^\prime }$

appear negligible,

$\overline {v^\prime w^\prime }$

appear negligible,

![]() $\overline {u^\prime w^\prime }$

is very significant and its transverse profile shows an off-centre peak as classically observed in turbulent wakes of bluff bodies. This asymmetry has already been observed experimentally by Ashok, Van Buren & Smits (Reference Ashok, Van Buren and Smits2015) who have attributed it to a kind of swirl in the evolution of the wake generated by a pair of unequal vortices in the wake. The asymmetry is also clearly visible in the turbulent fluxes

$\overline {u^\prime w^\prime }$

is very significant and its transverse profile shows an off-centre peak as classically observed in turbulent wakes of bluff bodies. This asymmetry has already been observed experimentally by Ashok, Van Buren & Smits (Reference Ashok, Van Buren and Smits2015) who have attributed it to a kind of swirl in the evolution of the wake generated by a pair of unequal vortices in the wake. The asymmetry is also clearly visible in the turbulent fluxes

![]() $\overline {u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{j} }$

given that

$\overline {u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{j} }$

given that

![]() $\overline {w^\prime u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} }$

and

$\overline {w^\prime u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} }$

and

![]() $\overline {v^\prime u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} }$

(

$\overline {v^\prime u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} }$

(

![]() $w'\equiv u^{\prime}_{3}$

,

$w'\equiv u^{\prime}_{3}$

,

![]() $v'\equiv u^{\prime}_2$

) are very different for all

$v'\equiv u^{\prime}_2$

) are very different for all

![]() $i=1,2,3$

(see figure 3

d–f). The maximum magnitude fluxes of turbulent energy appear around

$i=1,2,3$

(see figure 3

d–f). The maximum magnitude fluxes of turbulent energy appear around

![]() $z/b \approx 1$

.

$z/b \approx 1$

.

Figure 3. Transverse (

![]() $z$

direction) profiles of various one-point velocity statistics. (a) The mean velocity in the streamwise direction. (b,c) Averages of products of two fluctuating velocities. (d–f) Averages of products of three fluctuating velocities. The wake half-width is

$z$

direction) profiles of various one-point velocity statistics. (a) The mean velocity in the streamwise direction. (b,c) Averages of products of two fluctuating velocities. (d–f) Averages of products of three fluctuating velocities. The wake half-width is

![]() $b=41\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

$b=41\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

![]() $x/D=19.54$

,

$x/D=19.54$

,

![]() $b=44\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

$b=44\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

![]() $x/D=31.00$

,

$x/D=31.00$

,

![]() $b=48\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

$b=48\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

![]() $x/D=40.00$

and

$x/D=40.00$

and

![]() $b=51\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

$b=51\,{\textrm{mm}}$

at

![]() $x/D=51.60$

. (Here

$x/D=51.60$

. (Here

![]() $D=80\,{\textrm{mm}}$

.)

$D=80\,{\textrm{mm}}$

.)

3.2. Averaged one-point turbulent energy advection, transport and production

Turbulent energy fluxes are part and parcel of the turbulent kinetic energy budget

\begin{align} \underbrace { \bar {u}_j \frac {\partial k}{\partial x_j} }_{\mathcal{A}} + \underbrace { \left (\overline {u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{j} } \right ) \frac {\partial \bar {u}_i}{\partial x_j} }_{\mathcal{P}} &= -\frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \overline {u^{\prime}_{j} p^\prime } \right ) - \underbrace { \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \frac { \overline { u^{\prime}_{j} u^{\prime}_{i} u^\prime _i}}{2} \right ) }_{\mathcal{D} } + \nu {\nabla} ^2 k - \epsilon, \end{align}

\begin{align} \underbrace { \bar {u}_j \frac {\partial k}{\partial x_j} }_{\mathcal{A}} + \underbrace { \left (\overline {u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{j} } \right ) \frac {\partial \bar {u}_i}{\partial x_j} }_{\mathcal{P}} &= -\frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \overline {u^{\prime}_{j} p^\prime } \right ) - \underbrace { \frac {\partial }{\partial x_j} \left ( \frac { \overline { u^{\prime}_{j} u^{\prime}_{i} u^\prime _i}}{2} \right ) }_{\mathcal{D} } + \nu {\nabla} ^2 k - \epsilon, \end{align}

where

![]() $k\equiv 0.5 \overline {u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} }$

is the turbulent kinetic energy per unit mass and the overbars signify time averaging (note that the average turbulence dissipation rate

$k\equiv 0.5 \overline {u^{\prime}_{i} u^{\prime}_{i} }$

is the turbulent kinetic energy per unit mass and the overbars signify time averaging (note that the average turbulence dissipation rate

![]() $\epsilon$

is also obtained by time averaging). The point now is not to further demonstrate the absence of axisymmetry, this asymmetry has already been demonstrated, but to give some idea of how the energetics of our turbulent wake vary with streamwise (

$\epsilon$

is also obtained by time averaging). The point now is not to further demonstrate the absence of axisymmetry, this asymmetry has already been demonstrated, but to give some idea of how the energetics of our turbulent wake vary with streamwise (

![]() $x$

) and transverse (z) distances.

$x$

) and transverse (z) distances.

Figure 4. Transverse profiles of

![]() $\mathcal{A}$

,

$\mathcal{A}$

,

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

$\mathcal{P}$

![]() ${\textrm{and}}$

${\textrm{and}}$

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

(defined in (3.1)) at four streamwise locations.

$\mathcal{D}$

(defined in (3.1)) at four streamwise locations.

Using the velocity statistics described in § 3.1, the advection (

![]() $\mathcal{A}$

), production (

$\mathcal{A}$

), production (

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

) and turbulent transport/diffusion (

$\mathcal{P}$

) and turbulent transport/diffusion (

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

) of turbulent kinetic energy (defined in (3.1)) are calculated and plotted in figure 4. The streamwise derivatives

$\mathcal{D}$

) of turbulent kinetic energy (defined in (3.1)) are calculated and plotted in figure 4. The streamwise derivatives

![]() $(\partial /\partial x)$

are estimated as follows: firstly, the velocity vectors in all four streamwise locations with the same

$(\partial /\partial x)$

are estimated as follows: firstly, the velocity vectors in all four streamwise locations with the same

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

coordinates are fitted by a power law dependence on

$z$

coordinates are fitted by a power law dependence on

![]() $x$

and the streamwise derivative at each location is calculated by differentiating the power law fit. Secondly, all the streamwise derivatives with the same

$x$

and the streamwise derivative at each location is calculated by differentiating the power law fit. Secondly, all the streamwise derivatives with the same

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

coordinates are averaged over

$z$

coordinates are averaged over

![]() $y$

and only

$y$

and only

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

dependencies are kept for all the terms of (3.1). It is important to mention that the advection term is approximated as

$z$

dependencies are kept for all the terms of (3.1). It is important to mention that the advection term is approximated as

![]() $ \mathcal{A} \approx \overline {U}({\partial k}/{\partial x}) $

on account of

$ \mathcal{A} \approx \overline {U}({\partial k}/{\partial x}) $

on account of

![]() $\overline {U} \gg \overline {u_2}\equiv \overline {V}, \overline {u_3}\equiv \overline {W}$

. In the turbulence production (

$\overline {U} \gg \overline {u_2}\equiv \overline {V}, \overline {u_3}\equiv \overline {W}$

. In the turbulence production (

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

) and turbulent diffusion (

$\mathcal{P}$

) and turbulent diffusion (

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

) rates, the maximum contribution of terms involving a streamwise derivative is less than 5

$\mathcal{D}$

) rates, the maximum contribution of terms involving a streamwise derivative is less than 5

![]() $\%$

and 7

$\%$

and 7

![]() $\%$

, respectively. The PIV window stitching error mentioned at the start of § 3.1 is also present in figure 4 in the measurement merging regions. The discontinuity in the estimate of

$\%$

, respectively. The PIV window stitching error mentioned at the start of § 3.1 is also present in figure 4 in the measurement merging regions. The discontinuity in the estimate of

![]() $\mathcal{A}$

is higher than in the

$\mathcal{A}$

is higher than in the

![]() $\mathcal{D}$

and

$\mathcal{D}$

and

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

estimates. This could be related to the power law fitting approximation used for calculating the streamwise derivatives for

$\mathcal{P}$

estimates. This could be related to the power law fitting approximation used for calculating the streamwise derivatives for

![]() $\mathcal{A}$

.

$\mathcal{A}$

.

The profiles of

![]() $\mathcal{A}$

,

$\mathcal{A}$

,

![]() $\mathcal{P}$

$\mathcal{P}$

![]() ${\textrm{and}}$

${\textrm{and}}$

![]() $\epsilon$

in figure 4 are qualitatively similar to results reported in Townsend (Reference Townsend1949) for wakes of circular cylinders, in Kewalramani et al. (Reference Kewalramani, Ji, Dossmann, Becker, Gradeck and Rimbert2024) for round turbulent jets and in Cimarelli et al. (Reference Cimarelli, Mollicone, Van Reeuwijk and De Angelis2021) for temporal jets. As shown in the figure where we also plot results by Uberoi & Freymuth (Reference Uberoi and Freymuth1970) from a sphere’s axisymmetric wake for comparison, they are also qualitatively similar to profiles in axisymmetric wakes. In particular, the advection changes sign from negative to positive as

$\epsilon$

in figure 4 are qualitatively similar to results reported in Townsend (Reference Townsend1949) for wakes of circular cylinders, in Kewalramani et al. (Reference Kewalramani, Ji, Dossmann, Becker, Gradeck and Rimbert2024) for round turbulent jets and in Cimarelli et al. (Reference Cimarelli, Mollicone, Van Reeuwijk and De Angelis2021) for temporal jets. As shown in the figure where we also plot results by Uberoi & Freymuth (Reference Uberoi and Freymuth1970) from a sphere’s axisymmetric wake for comparison, they are also qualitatively similar to profiles in axisymmetric wakes. In particular, the advection changes sign from negative to positive as

![]() $z/b$

increases both in our slender body’s turbulent wake and in the sphere’s turbulent wake of Uberoi & Freymuth (Reference Uberoi and Freymuth1970). This change of sign reflects a change of sign in the turbulent transport/diffusion in both flows as turbulence is transported outwards by turbulence from

$z/b$

increases both in our slender body’s turbulent wake and in the sphere’s turbulent wake of Uberoi & Freymuth (Reference Uberoi and Freymuth1970). This change of sign reflects a change of sign in the turbulent transport/diffusion in both flows as turbulence is transported outwards by turbulence from

![]() $z=0$

to a

$z=0$

to a

![]() $z$

of the order of

$z$

of the order of

![]() $b$

and then inwards for higher values of

$b$

and then inwards for higher values of

![]() $z$

. Note, however, that the advection curves for

$z$

. Note, however, that the advection curves for

![]() $z/b \gt 1$

increase with increasing

$z/b \gt 1$

increase with increasing

![]() $x$

because

$x$

because

![]() $\overline {U}$

increases with

$\overline {U}$

increases with

![]() $x$

in that outer region (see comments on effective blockage at the start of § 3.1). In the absence of effective blockage they should be slowly decreasing in intensity like the turbulent transport/diffusion curves. The ratio

$x$

in that outer region (see comments on effective blockage at the start of § 3.1). In the absence of effective blockage they should be slowly decreasing in intensity like the turbulent transport/diffusion curves. The ratio

![]() $\mathcal{D}/\epsilon$

does not vary much with streamwise

$\mathcal{D}/\epsilon$

does not vary much with streamwise

![]() $x$

as in the grid turbulence results reported by Valente & Vassilicos (Reference Valente and Vassilicos2014).

$x$

as in the grid turbulence results reported by Valente & Vassilicos (Reference Valente and Vassilicos2014).

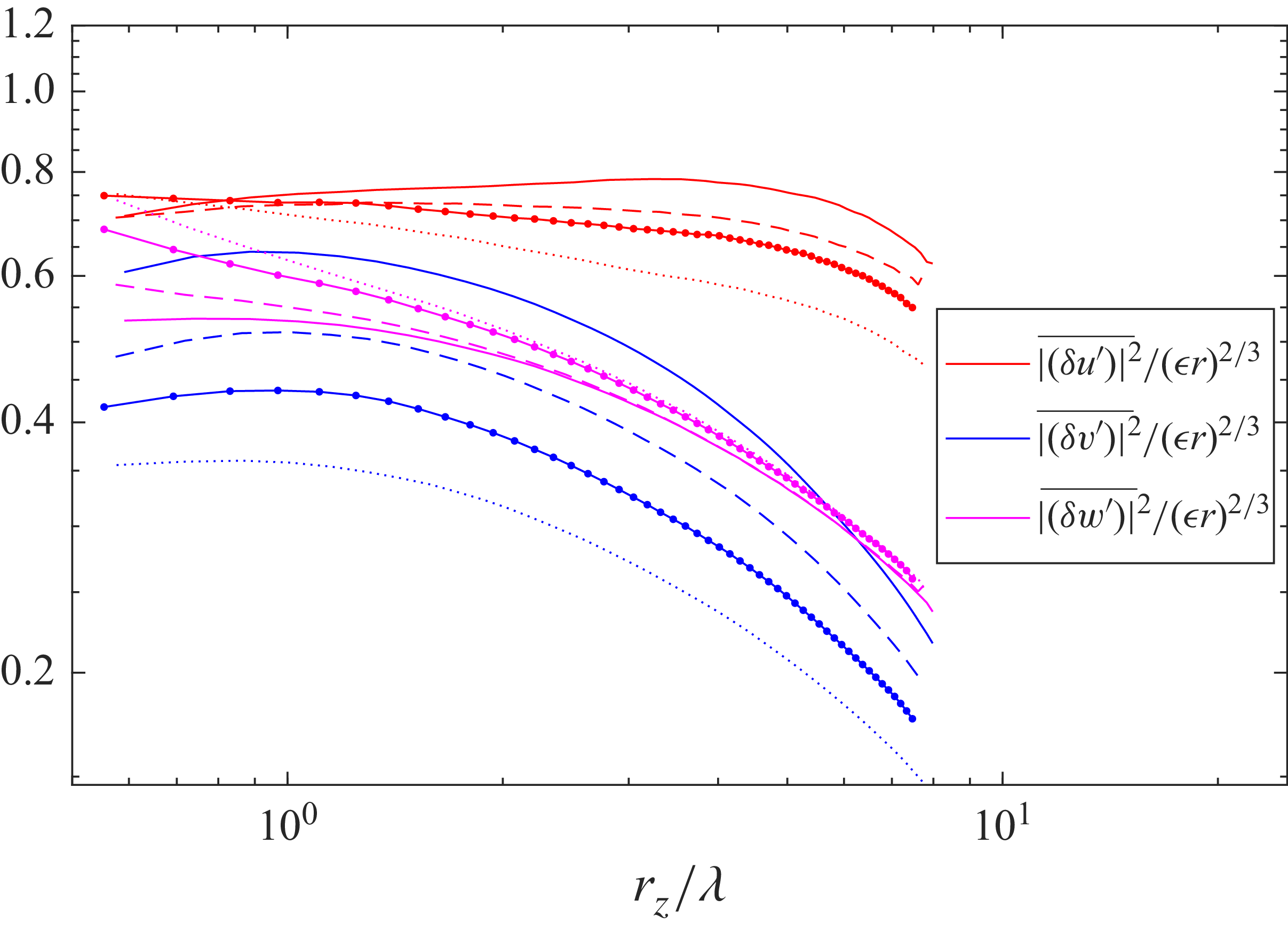

Figure 5. Compensated structure function

![]() $\overline {| \delta u^\prime |^2 }/(\epsilon r )^{2/3}$

at the centre of the field of view. The results at

$\overline {| \delta u^\prime |^2 }/(\epsilon r )^{2/3}$

at the centre of the field of view. The results at

![]() $x/D =19.54$

,

$x/D =19.54$

,

![]() $31.00$

,

$31.00$

,

![]() $40.00$

and

$40.00$

and

![]() $51.60$

are shown with solid, dashed, solid dotted and dotted lines, respectively.

$51.60$

are shown with solid, dashed, solid dotted and dotted lines, respectively.

3.3. Second-order structure functions

We close the characterisation of our prolate spheroid’s wake with second-order structure functions

where the overbars indicate time averaging as in the statistics of §§ 3.1 and 3.2.

In figure 5 we plot structure functions at the centre

![]() $y=0$

,

$y=0$

,

![]() $z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}$

of the PIV measurement regions. Specifically, we plot

$z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}$

of the PIV measurement regions. Specifically, we plot

![]() $\overline {|\delta u^\prime _1 (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}},}$

$\overline {|\delta u^\prime _1 (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}},}$

![]() $\overline {r_3) |^2} \equiv \overline {|\delta u^\prime (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2}$

,

$\overline {r_3) |^2} \equiv \overline {|\delta u^\prime (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2}$

,

![]() $\overline {|\delta u^\prime _2 (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2} \equiv \overline {|\delta v^\prime (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2}$

and

$\overline {|\delta u^\prime _2 (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2} \equiv \overline {|\delta v^\prime (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2}$

and

![]() $\overline {|\delta u^\prime _3 (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2} \equiv \overline {|\delta w^\prime (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2}$

, where

$\overline {|\delta u^\prime _3 (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2} \equiv \overline {|\delta w^\prime (x, y=0, z=36\,{\textrm{mm}}, r_3) |^2}$

, where

![]() $r_3 \equiv r_z$

. We present these structure functions normalised by

$r_3 \equiv r_z$

. We present these structure functions normalised by

![]() $(\epsilon r_z )^{2/3}$

because a turbulent flow is characterised by a

$(\epsilon r_z )^{2/3}$

because a turbulent flow is characterised by a

![]() $2/3$