Throughout the twentieth century, ceramics were primarily used in Mesoamerican archaeology to establish periods of social, economic, and political stability and change (Cobean Reference Cobean, Carrión and Cook2005:56). The most frequently used methods of analysis were types and type-variety classifications based on shared constellations of attributes, such as paste, surface finish, vessel form, and decorative motifs. In addition to the use of methods such as radiocarbon dating to establish chronologies, by the 1960s attention shifted to the development of analytical methodologies to describe other aspects of ceramic behavior, such as resource, technology, and production activities. Although these analyses can be accomplished on sherds that comprise most recovered materials, we highlight here a newer approach that focuses on the decoration of whole vessels from sites in the Lake Pátzcuaro, Cuitzeo, and Zacapu Basins of central and northern Michoacán (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of sample locations in Michoacán and southern Guanajuato. (Color online)

Rather than enumerating the separate motifs that appear on sherds, this approach, popularly labeled “symmetry analysis,” focuses on whole designs and classifies them by the geometries that repeat the constituent motifs. The preliminary test comparison we describe here considers a sample of the symmetries of whole-vessel designs from north-central Michoacán that indicate critical breaks or transitions in the sequence from the Late Preclassic to the Late Postclassic periods that did not match the transitions indicated by type-variety classification or paste sourcing production models. We present the comparisons and interpretations of each approach and discuss their implications for cultural continuities and changes in this region.

The Type-Variety Classification of Ceramics

During the 1980s the chronology of ceramic phases for the Zacapu Lake Basin was established by Carot (Reference Carot2001), Michelet (Reference Michelet1992, Reference Michelet, Mastache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008), and Pereira (Reference Pereira, Williams and Weigand1996). In the early 1990s ceramic chronologies for the eastern and southern portions of the Cuitzeo Basin were established by Filini (Reference Filini2007) and Healan and Hernández (Reference Healan and Hernández2023). However, before 1990, the sequence of cultural phases was unknown for the Lake Pátzcuaro Basin. Then, between 1990 and 2006 Pollard (Reference Pollard1993, Reference Pollard2000, Reference Pollard2001, Reference Pollard2005) classified almost 60,000 sherds and whole vessels from both survey and excavation for this area. In all three lake basins, these stratigraphically defined typological chronologies were associated with radiocarbon dates. They described the succession of settlement patterns and mortuary, ritual, and monumental architecture (Espejel Carbajal et al. Reference Carbajal, Claudia, Haro and Carbajal2014; Healan and Hernández Reference Healan and Hernández2023; Michelet Reference Michelet1992; Reference Michelet, Mastache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008; Pereira Reference Pereira1997, Reference Pereira1999; Pollard Reference Pollard2000, Reference Pollard2005, Reference Pollard, Williams and Maldonado2016; Pollard and Cahue Reference Pollard and Cahue1999).

These ceramic typological chronologies revealed major changes in vessel form and decoration that marked the beginning and end of the Classic period (AD 100–600/650), the end of the Epiclassic period (AD 600–850/900), and the end of the Early Postclassic period (AD 1100/1200). They also defined short transitional phases during which ceramics from adjacent phases overlapped (see Table 2). Specifically, the Loma Alta ceramic phases of the Pátzcuaro and Zacapu Basins and the Mixtlán phase in the Cuitzeo Basin during the Classic period revealed contact between local elites and Teotihuacan in, for example, thin orange pottery, Pachuca green obsidian, and the burial of individuals from the Pátzcuaro Basin in the Oaxaca barrio at Teotihuacan (Filini Reference Filini2007; Pereira Reference Pereira, Williams and Weigand1996; Pollard and Haskell Reference Pollard and Haskell2006; Spence et al. Reference Spence, Gómez Chávez, Longstaffe, Gazzola, Pereira, Olsen and Pollard2024). During the Lupe and Early Urichu / Early Palacio phases, there was contact with Tula as shown by, for example, Macana-type ceramics, flutes, projectile point types, and Mazapan-style figurines (Forest et al. Reference Forest, Jadot and Testard2020; Healan and Hernández Reference Healan and Hernández2023; Michelet Reference Michelet, Mastache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008; Pollard Reference Pollard2001; Pollard and Cahue Reference Pollard and Cahue1999). With the emergence of the Tarascan state in the Pátzcuaro Basin after AD 1350, and its spread across north-central Michoacán, the Tariacuri phase ceramics defined at Tzintzuntzan became widespread.

Archaeometry and the Study of Paste, Temper, and Technology of Production

Once these basic ceramic sequences for the Pátzcuaro Basin were defined, interest turned to analysis of production locales using neutron activation analysis (NAA) of pastes and tempers. Analyses at the Missouri University Research Reactor (MURR) and the Ford Nuclear Reactor at the University of Michigan of 171 sherds from the three Pátzcuaro sites that were used to create the basin chronologies (Table 1) and of 36 clay and ash samples (Hirshman and Ferguson Reference Hirshman and Ferguson2012), as well as more recent analysis of 300 sherds from Angamuco, a site in the southeastern Pátzcuaro Basin (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Hirshman, Pierce and Ferguson2023), indicated the stability of the INAA groups within the basin over time. Recently Cohen (Reference Cohen2024) confirmed this observation based on the previous NAA analysis of the 300 sherds and 30 clay samples, plus the petrographic study of 36 sherds and nine geological samples from Angamuco. The consistent use of these “long-lived” compositional recipes suggests that there was little change in the process of ceramic production, scale of production at the household level, and organization and means of distribution through local markets, despite major shifts in the political economy as the Tarascan state formed and then became part of the Spanish Empire (Hirshman Reference Hirshman2008; Hirshman and Haskell Reference Hirshman, Haskell, Williams and Maldonado2016; Juarez Olvera Reference Olvera and Berenice2019; Pollard Reference Pollard2017).

Table 1. Sherds in the Lake Pátzcuaro Basin Used for Basic Classification and Chronology.

In contrast, a technological study using neutron activation, petrography, and a chaîne opératoire approach to Postclassic ceramic assemblages from the adjacent Zacapu Basin (Jadot Reference Jadot2016) documented major innovations during the Milpillas phase of the Middle Postclassic. Changes in production methods were indicated by ceramic firing temperatures that could not be achieved by simple open firing, as used by modern potters (e.g., Williams Reference Williams2017); the use of resist decoration; and changes in clay coiling practice: these are associated with a change in population or ethnicity, such as the appearance of specialized potting communities, which represents migration from the Bajío of Guanajuato just north of the Zacapu Basin into northern Michoacán (Jadot Reference Jadot2016).

Symmetry Analysis of Whole-Vessel Designs from the Chupícuaro Phase (Late Preclassic) to the Tariacuri Phase (Late Postclassic)

From the time of the earliest archaeological studies, analytical efforts focused on ways to describe and classify fragmentary remains. In contrast to broken ceramics—sherds—that are found in profusion on archaeological sites and thus offer robust samples for analysis, whole vessels are not always available in sufficient numbers, especially for comparative analyses. Nevertheless, we introduce “symmetry analysis” to Mesoamerican archaeologists as a test case study with the hope that it will stimulate the amassing of sufficient whole-vessel samples. Washburn conduced a similar effort over several decades, gathering a sample of more than 20,000 decorated vessels from over 500 sites in the American Southwest that enabled analysis of Puebloan activities during a 1,000-year period from AD 600 to 1600 (Washburn et al. Reference Washburn, Crowe and Ahlstrom2010), as illustrated by an interactive digital map that enables comparison of symmetry and type distributions (Washburn et al. Reference Washburn, Vetter, Zhu, Korzh and Knowles-Kellett2022).

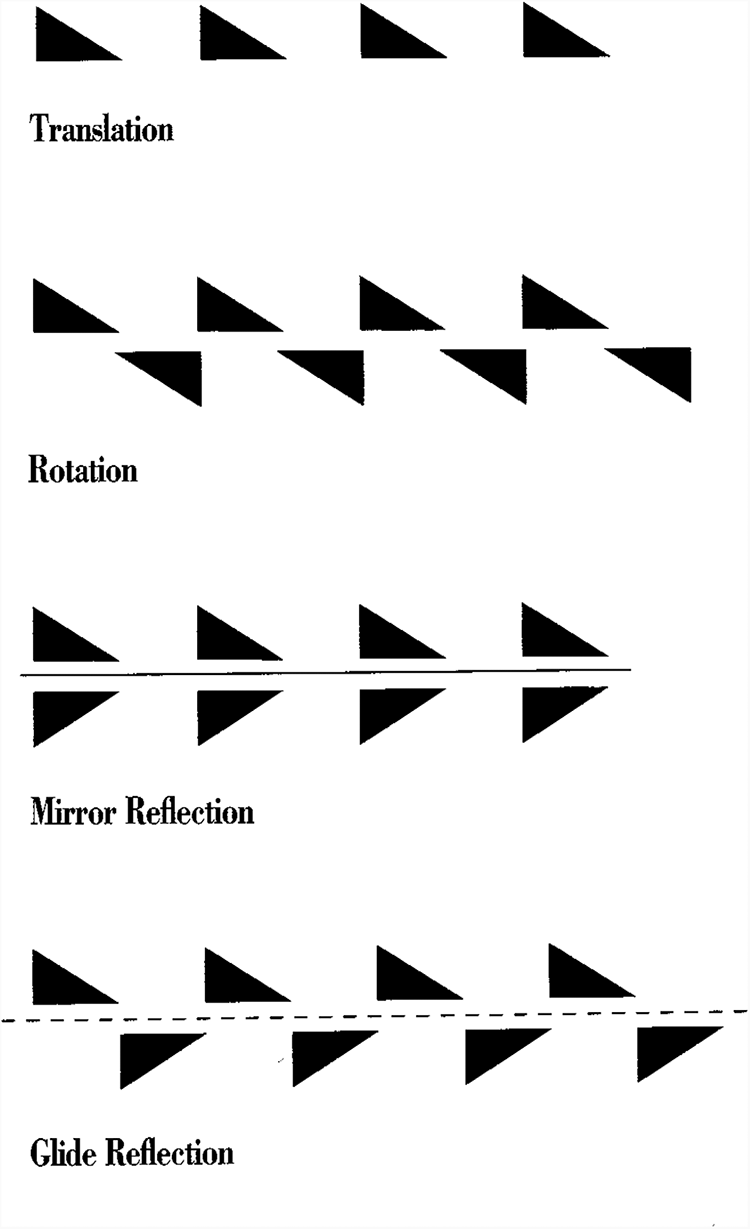

Symmetry analysis is a methodological approach that focuses on the geometric symmetries—translations, rotations, mirror reflections, and glide reflections—that organize and repeat motifs in a design (Figure 2). The model is semiotic: it is essentially a mathematical grammar that describes the construction of a pattern by the geometric symmetry motions that superimpose motifs one on top of the next as they move along line and around point axes. This structural description of matter, basic to physics and chemistry, was codified in three dimensions at the turn of the twentieth century by Russian crystallographers and later by mathematicians for the Euclidean planar classes (for a brief history, see Washburn and Crowe Reference Washburn and Crowe1988).

Figure 2. The four movements in the plane (Washburn and Crowe Reference Washburn and Crowe1988:44–51).

Here we follow the suggestion of Anna Shepard who, in a little-known 1948 publication of the Carnegie Institution, advocated the analysis of cultural designs by pattern symmetries, illustrating her discussion with examples of Pueblo and Cocle ceramic designs. Washburn and her colleague mathematician Donald Crowe (Reference Washburn and Crowe1988) sought to make this approach available to pattern analysts in many fields from textile and ceramic design to mosaic and architectural features by compiling a handbook for non-mathematicians that describes the Euclidean symmetries of finite, one-dimensional, and two-dimensional patterns in the plane. Stevens (Reference Stevens1980) and Hargittai and Hargittai (Reference Hargittai and Hargittai1994) also describe the basics with numerous helpful illustrations. Since then, numerous analysts have used symmetry to analyze decorated materials worldwide, many of which are described in a recent annotated bibliography (Washburn Reference Washburn2024), as well as in edited volumes (Washburn Reference Washburn2004; Washburn and Crowe Reference Washburn and Crowe2004), books (Teague and Washburn Reference Teague and Washburn2013), and journal articles (see Washburn Reference Washburn2024).

We focus in this article on the different kinds of insights and information afforded by each analytical approach. From a methodological perspective, typologies and symmetry analysis are simply analytical approaches. Typologies are formed from co-occurring groups of shared attributes: they are constructs of the analysts’ perceptions of attributes likely to be significant and thus recorded. In contrast, symmetry classes are rigidly defined, mathematically based ways of classifying the repetition of units of the same shape.

From a cultural perspective, however, one of the most important differences between the two classification approaches lies in the cultural information embedded in separate motifs versus the symmetrical ways that the motifs are structured in a design. It is important to ask what kinds of cultural meaning, if any, are embedded in these two approaches, one of which includes design parts as just one among many attributes of a type class, and the other that focuses solely on the mathematical configuration of the parts. Washburn (Reference Washburn1983, Reference Washburn2018) and Hann (Reference Hann2013) discuss the cultural significance of structure.

One important reason to attend to the symmetries in pattern structure derives from perceptual studies that indicate the fundamental salience of the property of symmetry for object recognition and identification; for reviews, see Locher and Nodine (Reference Locher and Nodine1989) and Tyler (Reference Tyler2002). That the property of symmetry plays a key role in human cognitive development has deep roots in the evolutionary history of Homo sapiens (Hodgson Reference Hodgson2015). Significantly, numerous studies have shown that (1) structural classifications of pattern by geometric symmetries indicate that different cultures preferentially choose only certain symmetries and use them consistently to structure their designs and (2) the structural symmetries in the designs of a particular culture are visual signs of the same ordering principles in other domains of that culture (Washburn Reference Washburn1999). Indeed, there is a pervasive presence of symmetrical organization throughout culture that has been documented ethnographically; for example, in social relationships (Lévi-Strauss Reference Lévi-Strauss1969), village layout (Adams Reference Adams1973; Arnold Reference Arnold and Washburn1983), architectural form (Cunningham Reference Cunningham1964), textiles (Franquemont and Franquemont Reference Franquemont, Franquemont, Dorothy and Donald2004; Grünbaum Reference Grünbaum1990), and cosmology (Witherspoon and Peterson Reference Witherspoon and Peterson1995).

Here we argue that we can recover some of these important social, economic, political, and religious organizational activities in archaeological materials through the recognition of continuities and changes in design symmetries. Especially fruitful are studies that define long-term and wide-ranging continuities and changes in design symmetries that can be correlated with other political, economic, and environmental changes; for example, Washburn and colleagues’ (Reference Washburn, Crowe and Ahlstrom2010) study of 1,000 years of prehistory in the American Southwest; Erbudak’s studies of interactions pathways among medieval peoples in the Mediterranean, Asia, and the Middle East (e.g., Erbudak and Onat Reference Erbudak and Onat2020); and Roe’s (Reference Roe and Dorothy2004) studies on migration patterns throughout the Antilles.

The mechanics of symmetry analysis can be found in Washburn and Crowe (Reference Washburn and Crowe1988) for the plane pattern designs analyzed in this article that occur in finite (Figure 3), one-dimensional (band) (Figure 4), and two-dimensional (wallpaper) dimensions (Figure 5). The nomenclature indicates the motions present and, where relevant, with primes, changes in color. We illustrate samples of each symmetry class with ceramic designs from each phase, focusing on how changes in symmetrical organization correlate with changes in temporal phase transitions.

Figure 3. A finite design (c2) with examples of possible patterns (Washburn and Crowe Reference Washburn and Crowe1988:57). Photo of Loma Alta phase 2 bowl from Erongarícuaro (photograph by Helen Perlstein Pollard). (Color online)

Figure 4. An infinite one-dimensional pattern (p111) with examples of possible patterns (Washburn and Crowe Reference Washburn and Crowe1988:59). Photo of Tariacuri phase spouted vessel from Urichu (photograph by Helen Perlstein Pollard). (Color online)

Figure 5. An infinite two-dimensional pattern (p’c4gm) with examples of possible patterns (Washburn and Crowe Reference Washburn and Crowe1988:61). Photo of Loma Alta phase 3 bowl from Erongarícuaro (photograph by Helen Perlstein Pollard). (Color online)

We identified the symmetry patterns found on 60 complete vessels (Pollard and Washburn Reference Pollard and Washburn2016) primarily associated with burials from the Lake Pátzcuaro Basin sites of Erongarícuaro (Pollard Reference Pollard2005; Pollard and Haskell Reference Pollard and Haskell2006), Tzintzuntzan (Castro Leal Reference Castro Leal1986), Urichu (Pollard Reference Pollard2000, Reference Pollard2001) and Angamuco (Cohen Reference Cohen2016; see Figure 1). We augmented this analysis with 83 vessels from the type-site Chupícuaro (Porter Reference Porter1956), the Cuitzeo Basin site Queréndaro (Carot Reference Carot2001), and three sites in the Zacapu Basin (Loma Alta, El Palacio, and Malpaís Prieto; Jadot Reference Jadot2016; Michelet Reference Michelet, Mastache, Cobean, Cook and Hirth2008). For identifications for each vessel in the sample see Supplementary Material 1. Although there is no current evidence of Chupícuaro phase occupation in either the Pátzcuaro or Zacapu Basins, Chupícuaro occupation is found in the eastern and southern Cuitzeo Basin, and the following phase includes all regions of north-central Michoacán: “The Formative Chupícuaro culture has been reputed for the quality of its ceramics since excavations began in the Valley of Acámbaro in 1945. This singular tradition was so powerful that it influenced neighboring regions and left a durable imprint on later ceramic styles” (Darras and Hamon Reference Darras and Hamon2020:445). This is clear in the Mixtlán phase of the Cuitzeo/Ucareo Basins and the Loma Alta phases of the Zacapu and Pátzcuaro Basins.

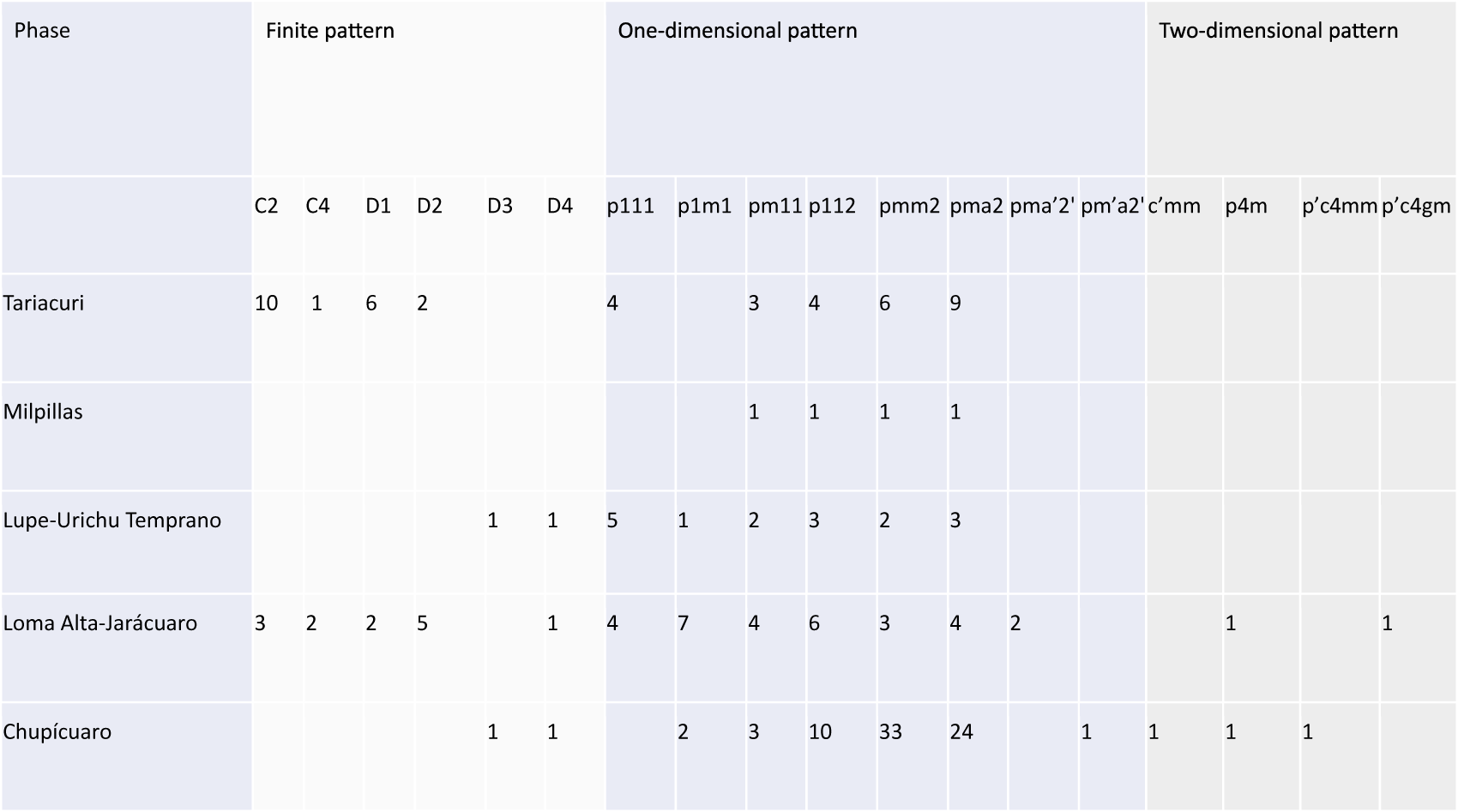

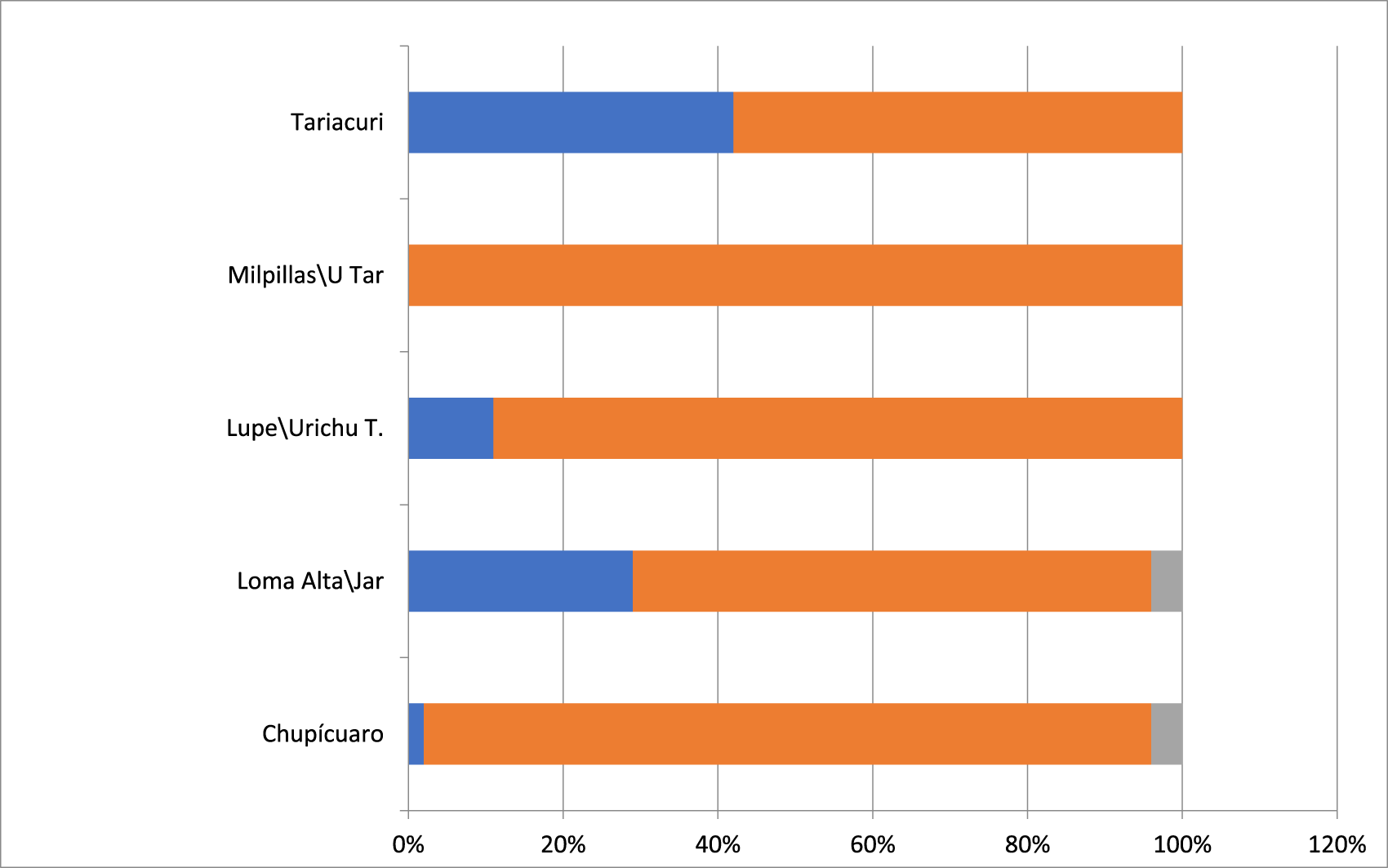

Figure 6 presents the total number of vessels in the sample (143) for each site for each of the five phases shown in Table 2: Chupícuaro (65), Loma Alta-Jarácuaro (32), Lupe-Urichu Temprano (13), Milpillas-Urichu Tardío (3), and Tariacuri (30). Two phases, Lupe and Urichu Temprano, were combined because of the uneven sample sizes in this pilot study. Because some vessels have more than one design and thus have more than one symmetric class (Figure 7), the total number of symmetry patterns in the analysis is 190. Figure 6 presents the specific symmetry classes for each phase and groups the symmetry classes into the three axial categories: finite, one-dimensional, and two-dimensional, whereas Figure 8 highlights the variation in axial categories by the five phases. To confirm synchronous symmetry classes given the length of some of the phases, we looked at the co-occurrence of classes on vessels from the same burials and caches. It supports the results found on Figure 8 and thus the general synchronicity of vessels within phases.

Figure 6. The symmetry patterns by phase.

Figure 7. Multiple symmetries on a vessel. Photo of a Tariacuri phase spouted vessel from Urichu (photograph by Helen Perlstein Pollard). (Color online)

Figure 8. Finite (blue), one-dimensional (orange), and two-dimensional (gray) patterns by phase. (Color online)

Table 2. Basic Chronologies of Michoacán.

Notes: References for the Pátzcuaro Basin: Pollard Reference Pollard2000, Reference Pollard2005, Reference Pollard2017; for the Zacapu Basin: Carot Reference Carot2001; Jadot Reference Jadot2016; for the Cuitzeo/Ucareo Basins: Healan and Hernández Reference Healan and Hernández2023; Hernández Reference Hernández, Williams and Maldonado2016; and for Chupícuaro: Darras Reference Darras2006; Darras and Faugère Reference Darras, Faugère, Williams, Weigand, Mesías and Grove2005.

The results of this preliminary study suggest both continuity and change in the prehispanic ceramic tradition of central and northern Michoacán. Six of the seven possible one-color, one-dimensional, infinite classes are found in the ceramic sample; four of these classes are found in all phases (pm11, p112, pmm2, and pma2). Two-dimensional infinite patterns are rare and found only in the Chupícuaro and Loma Alta-Jarácuaro phases; that is, during the Late Preclassic and Classic periods. Finite designs are more prevalent in the Loma Alta-Jarácuaro and Tariacuri phases. The Loma Alta-Jarácuaro phase examples primarily date from the Loma Alta 3 and Jarácuaro phases (AD 350–600), occur on all the major decorated ceramic types from both the Pátzcuaro and Zacapu Basins, and may reflect elite interaction with Central Mexico (Filini Reference Filini2007; Spence et al. Reference Spence, Gómez Chávez, Longstaffe, Gazzola, Pereira, Olsen and Pollard2024) or the emergence of centralized elites, such as multilineage chiefs (Carot Reference Carot2001; Filini Reference Filini2007; Pereira Reference Pereira, Williams and Weigand1996; Pollard Reference Pollard2005). Of note, archaeological evidence of the Chupícuaro society is not found in the Zacapu or Pátzcuaro Basins, but by 100 BC the descendant Loma Alta society was spreading throughout both basins and adjacent areas, including Tingambato (Punzo Díaz Reference Díaz and Luis2022) and Morelia (Manzanilla López Reference Manzanilla López1988). The extremely high frequency of finite designs in the Late Postclassic period (42%) is of note because these finite c2 and d1 symmetry classes are often found on the most elaborate zoomorphic, spouted, miniature, and large tripod vessels primarily associated with elite residential and public ritual zones in the Tarascan sample (Pollard Reference Pollard, Williams and Maldonado2016).

The Loma Alta and Tariacuri phases were two periods during which notable changes occurred in symmetry design. In contrast to the type-site of Loma Alta in the Zacapu Basin (Carot Reference Carot2001; Pereira Reference Pereira, Williams and Weigand1996, Reference Pereira1999), the currently available Loma Alta burial data from the Pátzcuaro Basin revealed stronger continuities with earlier Chupícuaro patterns (Darras Reference Darras2006; Darras and Faugère Reference Darras, Faugère, Williams, Weigand, Mesías and Grove2005; Porter Reference Porter1956) than with the later Lupe (Epiclassic) and Early Urichu (Early Postclassic) mortuary patterns seen at Urichu, Tingambato, or Guadalupe (Pereira Reference Pereira1997, Reference Pereira1999), possibly reflecting a slower emergence of strong elites. However, because of the extremely small Early and Middle Postclassic samples in this symmetry study, confirmation of these trends awaits analysis of larger datasets. A mortuary study of the Late Postclassic (Tariacuri) burials from the Pátzcuaro Basin, including the Tarascan capital at Tzintzuntzan, supports a Late Postclassic pattern first isolated at Urichu, with additional evidence for increased social hierarchy and the state political economy (Acosta Reference Acosta1939; Cabrera Castro Reference Cabrera Castro and Puche1987; Espejel Carbajal Reference Carbajal, Claudia, Haro and Carbajal2014; Gali Reference Gali1946; Pollard Reference Pollard2017; Rubín de la Borbolla Reference de la Borbolla and Daniel1939, Reference de la Borbolla and Daniel1941). Thus, the dramatic changes documented in the design symmetry structure at this time mirror episodes of the restructuring of society.

Conclusion

The use of multiple analytical approaches enables data to be assessed from several different perspectives. As new data become available from new excavations, we will be better able to determine whether (1) the design symmetry analysis that indicates major innovation during the Classic and Late Postclassic periods, (2) the ceramic technological analyses that emphasize continuity throughout the sequence, and (3) the type-variety definition of phases that see major changes in vessel form and decoration with the emergence of the Classic, Epiclassic, and Postclassic periods are monitoring different dimensions of change and continuity in response to different social and environmental factors at different temporal and spatial scales. We are fully aware that our uneven samples from each phase of occupation may be creating patterns of different kinds of activity that did not actually exist in the human past.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Lopez Varela and Charles Kolb for organizing the “Ceramics and Archaeological Sciences” session at the 89th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, held in April 2024 in New Orleans, at which this article was first presented, and the discussant Kostalena Michelaki for her encouraging comments. Helen Perlstein Pollard also thanks her coauthor Dorothy Washburn for her development of ceramic symmetry analysis.

Funding Statement

Helen Perlstein Pollard received funding for the acquisition and analysis of ceramics from the Lake Pátzcuaro Basin from Wenner-Gren and Columbia University Latin American Center (1970–1972), Wenner-Gren and National Geographic (1990–1992), the NSF and NEH (1994–1998), and the Heinz Foundation (2001–2003); David Haskell received funding from Wenner-Gren (2005–2007). All field and laboratory research was done under permits from the Consejo de Arqueología, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mexico, to Helen Perlstein Pollard (see Informes in References Cited).

Data Availability Statement

Data from the Lake Pátzcuaro Basin are available in the Informes and published material in the References Cited.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2025.10147.

Supplementary Material 1. Symmetry types in the sampled pottery with sites they are from in parenthesis.