1 Introduction

There has been an increasing emphasis in educational assessment on formative evaluation and diagnostic feedback (Black & Wiliam, Reference Black and Wiliam2009; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Perry and Wardle2021). Cognitive diagnostic assessment (CDA) addresses this need by providing detailed information about examinees’ mastery of specific skills or attributes (Leighton & Gierl, Reference Leighton and Gierl2007; Rupp et al., Reference Rupp, Templin and Henson2010). To improve the efficiency of CDA administration, cognitive diagnostic computerized adaptive testing (CD-CAT) has emerged as a powerful approach that combines the benefits of cognitive diagnosis with the efficiency of adaptive testing (Cheng, Reference Cheng2009).

A critical component in CD-CAT is the item selection algorithm, which determines the items and the sequence in which they are administered to each examinee. Various item selection methods have been proposed, most of which are fundamentally connected through information theory principles, as demonstrated by Cheng (Reference Cheng2009) and Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Song, Wang, Gao and Xiong2020). These methods include the original Kullback–Leibler (KL) index (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chang and Douglas2003), likelihood-weighted KL and posterior-weighted KL (PWKL) indices (Cheng, Reference Cheng2009), modified PWKL (MPWKL) index (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015), the Shannon entropy (SHE) procedure (Tatsuoka, Reference Tatsuoka2002), and mutual information methods (Wang, Reference Wang2013). While these approaches may appear distinct, they all derive from related information-theoretic concepts, with KL divergence, Shannon entropy, and mutual information sharing deep mathematical connections in quantifying information gain and uncertainty reduction (Cover & Thomas, Reference Cover and Thomas1991). More recently, the generalized deterministic inputs, noisy “and” gate (G-DINA) model discrimination index (GDI) was introduced as an efficient alternative (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015). GDI quantifies the weighted variance in item success probabilities given a specific attribute distribution.

While these methods have demonstrated effectiveness in attribute-level classification accuracy, they face a significant computational challenge: as the number of attributes (K) increases, the computational burden grows exponentially. This occurs because most existing methods require evaluating all possible attribute patterns (

![]() ${2}^K$

) for each item in the bank before selecting the most suitable one as the next item to administer. For instance, with K = 10 attributes, algorithms must evaluate 1,024 possible patterns for each candidate item. This computational intensity can make real-time implementation challenging, particularly in settings requiring rapid item selection decisions.

${2}^K$

) for each item in the bank before selecting the most suitable one as the next item to administer. For instance, with K = 10 attributes, algorithms must evaluate 1,024 possible patterns for each candidate item. This computational intensity can make real-time implementation challenging, particularly in settings requiring rapid item selection decisions.

The only existing method that attempts to reduce the computational burden is the GDI method, which partially addresses this issue by working with reduced attribute patterns. Although GDI is more computationally efficient than the PWKL method (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015), which is known to be the most computationally intensive, its efficiency relative to KL and SHE—two other widely discussed methods in CD-CAT—remains unclear. This study aims to address this gap by evaluating GDI’s computational efficiency relative to KL and SHE. Moreover, the primary objective is to propose a novel and flexible approach that not only substantially reduces computational demands but also maintains the theoretical foundations and measurement precision of existing methods.

This article introduces the likelihood-based profile shrinkage (LBPS) algorithm as a solution to this challenge. The key insight of LBPS is that as testing proceeds, the set of plausible attribute patterns for an examinee rapidly shrinks based on their response patterns. By focusing only on the most likely attribute patterns, LBPS achieves substantial efficiency gains while preserving measurement accuracy. Importantly, LBPS can be integrated with any existing item selection method, making it a flexible enhancement to current CD-CAT implementations. In addition, LBPS can be implemented without requiring changes to existing item banks or cognitive diagnostic models (CDMs). Through simulation studies, we demonstrate that LBPS achieves comparable attribute classification accuracy to traditional methods while greatly reducing computation time, particularly for long tests measuring larger numbers of attributes. The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the theoretical framework of CDMs and existing item selection methods. Section 3 introduces the LBPS algorithm and establishes its theoretical properties. Section 4 presents simulation studies comparing LBPS with existing methods across various conditions. Section 5 discusses practical implications and future research directions.

2 Background

2.1 CDM framework

2.1.1 Basic setup

CDMs aim to provide detailed information about examinees’ mastery of specific skills or attributes underlying test performance. In CDA, the goal is to measure examinees’ mastery of K discrete attributes or skills. Each examinee’s mastery profile is represented by an attribute pattern

![]() $\boldsymbol{\alpha} =\left({\alpha}_1,\dots, {\alpha}_K\right)$

where

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} =\left({\alpha}_1,\dots, {\alpha}_K\right)$

where

![]() ${\alpha}_k=1$

indicates mastery of attribute k and

${\alpha}_k=1$

indicates mastery of attribute k and

![]() ${\alpha}_k=0$

indicates non-mastery for k = 1, 2, …, K attributes. Note that the terms “pattern” and “profile” are used interchangeably in the paper to refer to α. For K attributes, there are

${\alpha}_k=0$

indicates non-mastery for k = 1, 2, …, K attributes. Note that the terms “pattern” and “profile” are used interchangeably in the paper to refer to α. For K attributes, there are

![]() ${2}^K$

possible attribute patterns, representing all possible combinations of mastery and non-mastery across the measured attributes (de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2011). The relationship between items and attributes is specified through a J × K Q-matrix (Tatsuoka, Reference Tatsuoka, Nichols, Chipman and Brennan1995), where entry

${2}^K$

possible attribute patterns, representing all possible combinations of mastery and non-mastery across the measured attributes (de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2011). The relationship between items and attributes is specified through a J × K Q-matrix (Tatsuoka, Reference Tatsuoka, Nichols, Chipman and Brennan1995), where entry

![]() ${q}_{jk}=1$

if item j requires attribute k and

${q}_{jk}=1$

if item j requires attribute k and

![]() ${q}_{jk}=0$

otherwise. The Q-matrix represents the cognitive specifications of the test by mapping each item to its required attributes.

${q}_{jk}=0$

otherwise. The Q-matrix represents the cognitive specifications of the test by mapping each item to its required attributes.

2.1.2 Types of CDMs

CDMs can be categorized based on how they model the relationship between attributes and item responses (Ravand & Baghaei, Reference Ravand and Baghaei2020). In conjunctive models, examinees must master all required attributes to have a high probability of correctly answering an item. The Deterministic Inputs, Noisy “And” Gate (DINA) model (Junker & Sijtsma, Reference Junker and Sijtsma2001) and the Noisy Inputs, Deterministic “And” Gate (NIDA) model (Maris, Reference Maris1999) are prominent examples of conjunctive models. These models are particularly appropriate when skills build upon each other in a non-compensatory way. Disjunctive models assume that mastery of any one of the required attributes is sufficient for a high probability of success. The Deterministic Input, Noisy “Or” Gate (DINO) model (Templin & Henson, Reference Templin and Henson2006) exemplifies this approach. Such models are suitable when multiple solution strategies can lead to correct answers and mastery of one attribute can compensate for non-mastery of others.

Additive models, such as the additive CDM (ACDM; de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2011) and the linear logistic model (LLM; Maris, Reference Maris1999), take a different approach in which each mastered attribute contributes independently to the probability of a correct response. These models are appropriate when attributes have cumulative but independent effects on performance.

More recently, general diagnostic models have been developed that can accommodate multiple types of attribute relationships within the same assessment. The generalized DINA model (G-DINA; de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2011), the log-linear CDM (LCDM; Henson et al., Reference Henson, Templin and Willse2009), and the general diagnostic model (GDM; von Davier, Reference von Davier2005) allow different items to exhibit different attribute relationships. These general models provide greater flexibility but typically require larger sample sizes for stable parameter estimation.

2.1.3 The DINA model

While the methods developed in this article apply to any CDM, we use the DINA model for illustration due to its parsimony and wide use in diagnostic testing applications (Junker & Sijtsma, Reference Junker and Sijtsma2001; de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2009). Under the DINA model, an examinee must master all required attributes to have a high probability of answering an item correctly, making it a conjunctive model. For an examinee i with attribute pattern α responding to item j, the ideal response is

$$\begin{align}{\eta}_{ij}\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=\prod \limits_{k=1}^K{\alpha_{ik}}^{q_{jk}},\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}{\eta}_{ij}\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=\prod \limits_{k=1}^K{\alpha_{ik}}^{q_{jk}},\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${\eta}_{ij}\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1$

indicates mastery of all required attributes and

${\eta}_{ij}\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1$

indicates mastery of all required attributes and

![]() ${\eta}_{ij}\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0$

indicates a lack of at least one required attribute (de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2009).

${\eta}_{ij}\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0$

indicates a lack of at least one required attribute (de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2009).

The probability of a correct response of examinee i on item j is given by

where

![]() ${s}_j$

is the slipping parameter (probability of incorrect response despite mastery) and

${s}_j$

is the slipping parameter (probability of incorrect response despite mastery) and

![]() ${g}_j$

is the guessing parameter (probability of correct response despite non-mastery). These item parameters account for the probabilistic nature of the response process, where examinees who have mastered all required attributes may still make mistakes (slips), and those who lack required attributes may still answer correctly through guessing (de la Torre & Douglas, Reference de la Torre and Douglas2004). The DINA model’s simple form makes it particularly useful for understanding the fundamental principles of cognitive diagnosis while still capturing essential features of the response process. Its parsimony in parameter estimation and clear interpretation of results have made it a popular choice in diagnostic testing applications.

${g}_j$

is the guessing parameter (probability of correct response despite non-mastery). These item parameters account for the probabilistic nature of the response process, where examinees who have mastered all required attributes may still make mistakes (slips), and those who lack required attributes may still answer correctly through guessing (de la Torre & Douglas, Reference de la Torre and Douglas2004). The DINA model’s simple form makes it particularly useful for understanding the fundamental principles of cognitive diagnosis while still capturing essential features of the response process. Its parsimony in parameter estimation and clear interpretation of results have made it a popular choice in diagnostic testing applications.

2.2 Item selection methods in CD-CAT

Item selection methods in CD-CAT can be broadly categorized into parametric and nonparametric approaches (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chiu and Tsai2019). While non-parametric methods have emerged recently to address certain limitations of parametric approaches (Chiu & Chang, Reference Chiu and Chang2021), parametric methods remain fundamental to CD-CAT implementation. These parametric methods can be further classified as single-purpose or dual-purpose (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chang and Douglas2012). Single-purpose methods focus solely on optimizing the measurement of attribute profiles, while dual-purpose methods simultaneously measure both attribute profiles and general ability (Dai et al., Reference Dai, Zhang and Li2016; Kang et al., Reference Kang, Zhang and Chang2017; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zheng and Chang2014). This article proposes a new algorithm within the framework of parametric single-purpose item selection methods. Therefore, we focus our review on existing methods in this category, which form the foundation for CD-CAT item selection and remain the most widely used in practice.

2.2.1 Basic framework

In CD-CAT, parametric single-purpose item selection methods aim to optimize the measurement of examinees’ attribute mastery profiles. These methods utilize item parameters and probability models within a cognitive diagnostic framework to select items that maximize information about attribute patterns. After J items have been administered to an examinee, let

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}=\left({x}_1,\dots, {x}_J\right)$

denote the vector of observed responses, where xj

∈ {0,1}. Following Bayes’ theorem, the posterior probability of the attribute pattern is

${\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}=\left({x}_1,\dots, {x}_J\right)$

denote the vector of observed responses, where xj

∈ {0,1}. Following Bayes’ theorem, the posterior probability of the attribute pattern is

where

![]() ${\pi}_0\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

is the prior probability and

${\pi}_0\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

is the prior probability and

![]() $L\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)={\prod}_{j=1}^JP\left({X}_j={x}_j|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

is the likelihood function under the specified CDM. Define the item h as a candidate item in the pool of available items, from which the (J+1)-th item is to be selected based on a specified item selection method.

$L\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)={\prod}_{j=1}^JP\left({X}_j={x}_j|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

is the likelihood function under the specified CDM. Define the item h as a candidate item in the pool of available items, from which the (J+1)-th item is to be selected based on a specified item selection method.

2.2.2 Information-theoretic methods.

Kullback–Leibler-based approaches

The Kullback–Leibler (KL) information (Cover & Thomas, Reference Cover and Thomas1991; Kullback & Leibler, Reference Kullback and Leibler1951) provides a foundation for measuring the distance between probability distributions under different attribute patterns. For item j and two attribute patterns

![]() $\boldsymbol{\alpha}, \boldsymbol{\alpha}^{\prime}\in {\left\{0,1\right\}}^K$

, the KL information is defined as

$\boldsymbol{\alpha}, \boldsymbol{\alpha}^{\prime}\in {\left\{0,1\right\}}^K$

, the KL information is defined as

$$\begin{align}D_j\!\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \,\|\, \boldsymbol{\alpha}'\right)&=\sum_{x=0}^1P\left({X}_j=x|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right){log}\;\left[\frac{P\left({X}_j=x|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)}{P\left({X}_j=x|{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\right)}\right],\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}D_j\!\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \,\|\, \boldsymbol{\alpha}'\right)&=\sum_{x=0}^1P\left({X}_j=x|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right){log}\;\left[\frac{P\left({X}_j=x|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)}{P\left({X}_j=x|{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\right)}\right],\end{align}$$

where

![]() $P\left({X}_j=x|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

denotes the probability of response x given attribute pattern

$P\left({X}_j=x|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

denotes the probability of response x given attribute pattern

![]() $\boldsymbol{\alpha}$

under the specified CDM. Building on this framework, the KL index was proposed by Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Chang and Douglas2003) to select the next item maximizing:

$\boldsymbol{\alpha}$

under the specified CDM. Building on this framework, the KL index was proposed by Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Chang and Douglas2003) to select the next item maximizing:

$$\begin{align}KL_h\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\right)=\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}D_h\!\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} \,\|\, \boldsymbol{\alpha}_c\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}KL_h\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\right)=\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}D_h\!\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} \,\|\, \boldsymbol{\alpha}_c\right),\end{align}$$

where h represents the candidate item in the pool of available items,

![]() $\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}$

is the current estimate of the examinee’s attribute pattern, and c indexes attribute patterns (c = 1, 2, …,

$\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}$

is the current estimate of the examinee’s attribute pattern, and c indexes attribute patterns (c = 1, 2, …,

![]() ${2}^K$

). This index measures the total divergence between the response distributions under the estimated pattern and all other possible patterns. Cheng (Reference Cheng2009) enhanced this approach by incorporating posterior probabilities through the posterior-weighted KL (PWKL) index:

${2}^K$

). This index measures the total divergence between the response distributions under the estimated pattern and all other possible patterns. Cheng (Reference Cheng2009) enhanced this approach by incorporating posterior probabilities through the posterior-weighted KL (PWKL) index:

$$\begin{align}PWKL_h\!\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\right)&=\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}D_h\!\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} \,\|\, \boldsymbol{\alpha}_c\right)\pi\!\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_c|\boldsymbol{x}_J\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}PWKL_h\!\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}\right)&=\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}D_h\!\left(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\alpha}} \,\|\, \boldsymbol{\alpha}_c\right)\pi\!\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_c|\boldsymbol{x}_J\right),\end{align}$$

where

![]() $\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)$

is the posterior probability after J items have been answered, and

$\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)$

is the posterior probability after J items have been answered, and

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}_J$

is the response vector.

${\boldsymbol{x}}_J$

is the response vector.

Other KL information-based item selection methods include the modified PWKL (MPWKL) method (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015), and posterior-weighted CDM discrimination index (PWCDI) method (Zheng & Chang, Reference Zheng and Chang2016). This study employs only PWKL for comparison, as MPWKL, while achieving comparable performance to GDI, incurs substantial computational costs (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015). Additionally, PWCDI demonstrates inferior performance to PWKL with small calibration samples (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Chiu and Tsai2019), making PWKL the most suitable KL-based comparator for this investigation.

Shannon entropy-based approaches.

Shannon entropy (Cover & Thomas, Reference Cover and Thomas1991; Shannon, Reference Shannon1948) provides an alternative framework for quantifying uncertainty in the posterior distribution of attribute patterns. In the context of CD-CAT, after J items have been selected, the entropy of a distribution

![]() $\pi$

is defined as

$\pi$

is defined as

$$\begin{align}H\left(\pi \right)=-\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right){log}\;\left[\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)\right].\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}H\left(\pi \right)=-\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right){log}\;\left[\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)\right].\end{align}$$

Lower entropy values indicate greater certainty about the true attribute pattern. Building on information theory principles (Cover & Thomas, Reference Cover and Thomas1991), Tatsuoka (Reference Tatsuoka2002) proposed selecting items by minimizing the expected posterior entropy:

$$\begin{align}SH{E}_h=\sum_{x=0}^1H\left(\pi |{X}_h=x,{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right),\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}SH{E}_h=\sum_{x=0}^1H\left(\pi |{X}_h=x,{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right),\end{align}$$

where

![]() $\pi \mid {X}_h=x,{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}$

denotes the posterior distribution after observing response x to the candidate item h in the pool of available items,

$\pi \mid {X}_h=x,{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}$

denotes the posterior distribution after observing response x to the candidate item h in the pool of available items,

![]() $P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}\right)$

denotes the predicted probability of observing response x conditional on the response vector

$P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{J}}\right)$

denotes the predicted probability of observing response x conditional on the response vector

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}_J$

, and

${\boldsymbol{x}}_J$

, and

$$\begin{align}P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)=\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c\right)\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right).\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right)=\sum_{c=1}^{2^K}P\left({X}_h=x|{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c\right)\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_c|{\boldsymbol{x}}_J\right).\end{align}$$

Recent methodological advances have extended this framework through the expected mutual information index (Wang, Reference Wang2013) and the Jensen–Shannon divergence (JSD) index (Minchen & de la Torre, Reference Minchen and de la Torre2016; Yigit et al., Reference Yigit, Sorrel and De La Torre2019). Theoretical investigations have established that JSD is mathematically equivalent to mutual information in quantifying the information gain about an examinee’s attribute pattern (Yigit et al., Reference Yigit, Sorrel and De La Torre2019). Furthermore, a linear relationship was found between SHE and JSD (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Song, Wang, Gao and Xiong2020), indicating that these methods yield equivalent item selection decisions in CD-CAT applications. Given these theoretical equivalences, the present study employs the SHE method (Tatsuoka, Reference Tatsuoka2002) as the representative entropy-based approach in our comparative analyses.

2.2.3 GDI approach

Building on the G-DINA framework (de la Torre, Reference de la Torre2011), Kaplan et al. (Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015) introduced the G-DINA discrimination index (GDI). This index offers computational advantages by working with reduced attribute patterns, which are made up by

![]() ${K}_h^{\ast }$

attributes required by item h. For example, if a

q

-vector is defined as (1, 0, 1, 0, 1),

${K}_h^{\ast }$

attributes required by item h. For example, if a

q

-vector is defined as (1, 0, 1, 0, 1),

![]() ${K}_h^{\ast }=3$

attributes since this item only requires the first, third, and fifth attributes. Consequently, there are eight reduced attribute patterns based on the three required attributes. The GDI for item h is defined as

${K}_h^{\ast }=3$

attributes since this item only requires the first, third, and fifth attributes. Consequently, there are eight reduced attribute patterns based on the three required attributes. The GDI for item h is defined as

$$\begin{align}GD{I}_h=\sum_{c=1}^{2^{K_h^{\ast }}}\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right){\left[P\left({X}_h=1|\;{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)-{\overline{P}}_h\right]}^2,\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}GD{I}_h=\sum_{c=1}^{2^{K_h^{\ast }}}\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right){\left[P\left({X}_h=1|\;{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)-{\overline{P}}_h\right]}^2,\end{align}$$

where

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast }$

represents the c-th reduced attribute pattern for item h (

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast }$

represents the c-th reduced attribute pattern for item h (

![]() $c=1,2,\dots, {2}^{K_h^{\ast }}$

),

$c=1,2,\dots, {2}^{K_h^{\ast }}$

),

![]() $\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)$

is the posterior probability of the reduced attribute pattern after J items have been selected, and

$\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)$

is the posterior probability of the reduced attribute pattern after J items have been selected, and

![]() ${\overline{P}}_h=\sum_{c=1}^{2^{K_h^{\ast }}}\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)P\left({X}_h=1|{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)$

is the mean success probability. The GDI measures an item’s ability to differentiate between reduced attribute vectors, emphasizing those with higher success probabilities. The item with the highest GDI in the pool is selected.

${\overline{P}}_h=\sum_{c=1}^{2^{K_h^{\ast }}}\pi \left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)P\left({X}_h=1|{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}_{ch}^{\ast}\right)$

is the mean success probability. The GDI measures an item’s ability to differentiate between reduced attribute vectors, emphasizing those with higher success probabilities. The item with the highest GDI in the pool is selected.

2.2.4 Comparative properties

These methods offer distinct advantages for a single-purpose CD-CAT. The KL-based methods directly measure discrimination between attribute patterns, with PWKL improving upon the original KL index by incorporating posterior information (Cheng, Reference Cheng2009). The entropy-based methods approach item selection through uncertainty reduction in the posterior distribution. While SHE directly minimizes expected uncertainty, the mutual information method provides a theoretically equivalent formulation through information gain (Wang, Reference Wang2013). The GDI achieves computational efficiency through dimension reduction while maintaining measurement precision, particularly advantageous for assessments with many attributes (Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015). Despite their demonstrated effectiveness, opportunities remain for improving attribute pattern estimation efficiency in CD-CAT. The following section introduces a LBPS algorithm that builds upon these theoretical foundations while addressing certain limitations in existing approaches.

2.3 Computational considerations in CD-CAT

The practical implementation of CD-CAT item selection methods faces significant computational challenges, primarily arising from the need to evaluate large numbers of attribute patterns during the item selection process. For KL-based methods, item selection entails computing and summing up the KL information between the current attribute pattern estimate and all

![]() ${2}^K$

possible patterns, and this is done for all eligible items in the bank. When using PWKL, additional computational burden comes from calculating posterior probabilities for each pattern combination.

${2}^K$

possible patterns, and this is done for all eligible items in the bank. When using PWKL, additional computational burden comes from calculating posterior probabilities for each pattern combination.

Consider a test measuring K = 5 attributes with an item bank of 300 items as an example. Even in this relatively simple case, 32 possible attribute patterns must be evaluated for each item selection decision. The PWKL method requires computing and summing KL divergence values across all 32 patterns for each item under consideration. This computation must be performed for all eligible items in the bank to select the next item. The Shannon entropy method involves similar computational intensity, requiring the calculation of expected entropy by evaluating posterior distributions for possible responses across all attribute patterns, again repeated for each item in the bank.

The GDI method introduced by Kaplan et al. (Reference Kaplan, De La Torre and Barrada2015) offers some computational advantages by working only with the attributes required for each item. This reduces the pattern space from

![]() ${2}^K$

to

${2}^K$

to

![]() ${2}^{K_h^{\ast }}$

, where

${2}^{K_h^{\ast }}$

, where

![]() ${K}_h^{\ast}$

is typically much smaller than K, and requires fewer posterior probability calculations. However, even with these improvements, significant computational challenges remain. These computational demands become particularly acute when tests measure many attributes and as the item bank expands.

${K}_h^{\ast}$

is typically much smaller than K, and requires fewer posterior probability calculations. However, even with these improvements, significant computational challenges remain. These computational demands become particularly acute when tests measure many attributes and as the item bank expands.

The practical implications of these computational demands are substantial. They can affect response time between items, overall test administration efficiency, and the system resources required to implement CD-CAT. When multiple examinees are tested simultaneously, as is common in educational settings, these computational requirements become even more demanding. While the GDI method has made progress in reducing computational burden through reduced attribute patterns, there remains a clear need for more efficient approaches that can maintain measurement precision while reducing computation time and scaling effectively with the number of attributes.

3 The likelihood-based profile shrinkage algorithm

3.1 Key ideas

The computational burden of traditional CD-CAT item selection methods grows exponentially with the number of attributes K, as each method evaluates all

![]() ${2}^K$

possible attribute patterns for each eligible item in the bank at every item selection decision. However, as testing proceeds, the set of plausible, or most likely, attribute patterns for an examinee typically shrinks based on their response pattern. This observation motivates the key insight of LBPS: by focusing on the most likely attribute patterns for item selection while maintaining full pattern space for estimation, substantial computational savings can be achieved without sacrificing measurement precision.

${2}^K$

possible attribute patterns for each eligible item in the bank at every item selection decision. However, as testing proceeds, the set of plausible, or most likely, attribute patterns for an examinee typically shrinks based on their response pattern. This observation motivates the key insight of LBPS: by focusing on the most likely attribute patterns for item selection while maintaining full pattern space for estimation, substantial computational savings can be achieved without sacrificing measurement precision.

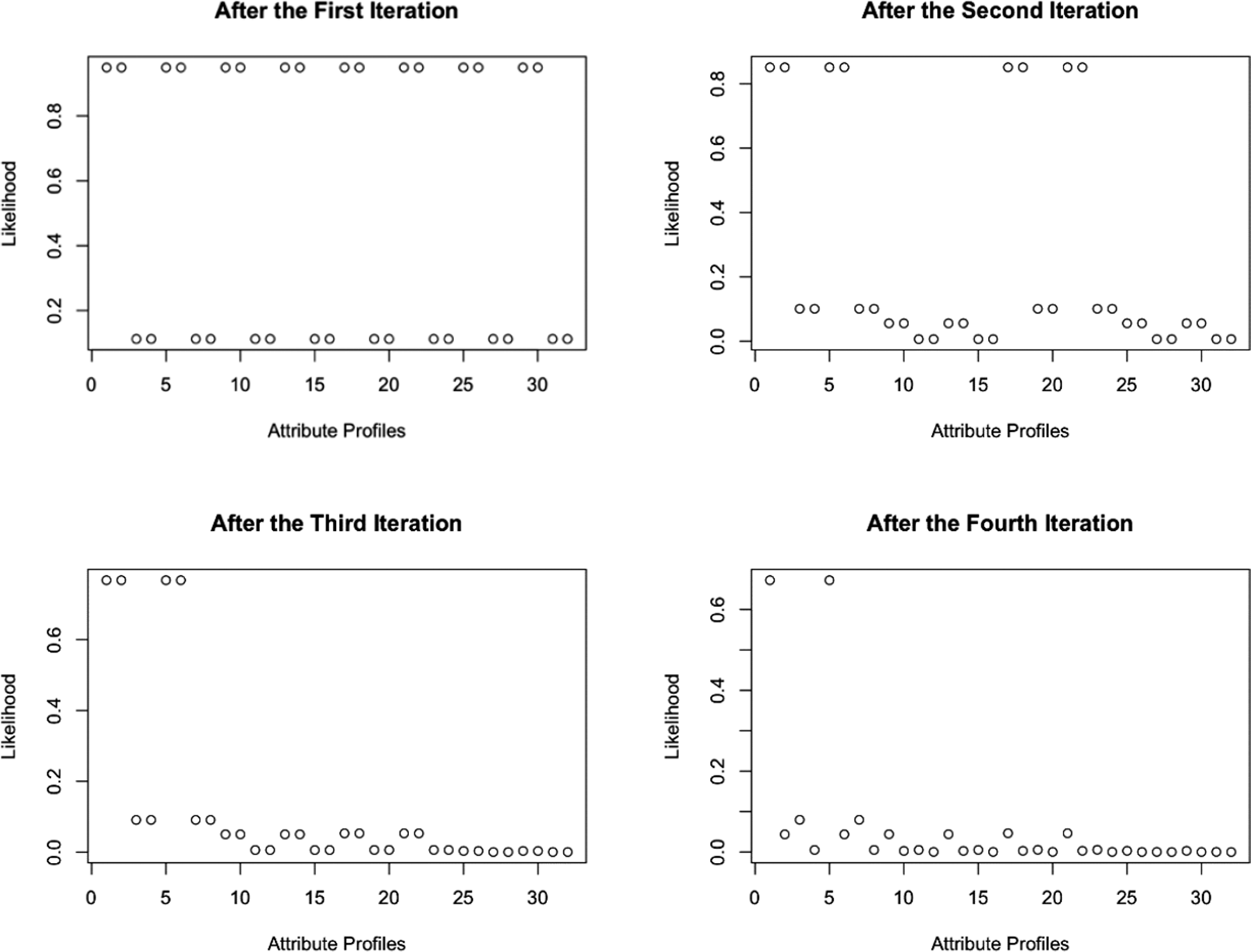

The likelihood function provides a natural mechanism for identifying these plausible patterns. After each response, patterns with maximum likelihood represent the most probable true states given the observed data. Figure 1 illustrates changes in attribute profiles’ likelihoods using LBPS with KL when K = 5. Early on, multiple profiles may have similar likelihoods, but as the test proceeds, the number of likely profiles shrinks (see Figure 1). By restricting item selection calculations to these patterns while using all patterns for estimation, LBPS balances computational efficiency with measurement accuracy.

Figure 1 An illustration of changes in attribute profiles’ likelihoods using LBPS with KL when K = 5.

Note: An iteration refers to a single cycle of the adaptive testing process: selecting the next item, collecting the examinee’s response, and updating the likelihoods of all attribute profiles and the examinee’s estimated attribute profile based on the accumulated responses.

3.2 Theoretical framework

Let

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}_t=\left({x}_1,\dots, {x}_t\right)$

denote the response vector after t items have been administered. For any attribute pattern

${\boldsymbol{x}}_t=\left({x}_1,\dots, {x}_t\right)$

denote the response vector after t items have been administered. For any attribute pattern

![]() $\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in A={\left\{0,1\right\}}^K$

, the likelihood under a cognitive diagnostic model is

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in A={\left\{0,1\right\}}^K$

, the likelihood under a cognitive diagnostic model is

$$\begin{align}L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)=\prod \limits_{j=1}^tP\left({X}_j={x}_j|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right).\end{align}$$

$$\begin{align}L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)=\prod \limits_{j=1}^tP\left({X}_j={x}_j|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right).\end{align}$$

Define the set of attribute patterns with the largest likelihood after t items have been answered as

For the response pattern

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}_t$

and a new item j that is answered with a response

${\boldsymbol{x}}_t$

and a new item j that is answered with a response

![]() ${x}_j$

,

${x}_j$

,

![]() $L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)=L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)P\left({X}_j={x}_j|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

.

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)=L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)P\left({X}_j={x}_j|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)$

.

Theorem 1

(Pattern set size after first item).Under the DINA model with

![]() ${s}_j,{g}_j<0.5$

, for an item requiring k attributes:

${s}_j,{g}_j<0.5$

, for an item requiring k attributes:

-

i.

$If\;{x}_1=1:\left|M\left({x}_1\right)\right|={2}^{K-k}$

$If\;{x}_1=1:\left|M\left({x}_1\right)\right|={2}^{K-k}$

-

ii.

$If\;{x}_1=0:\lvert M(x_1) \rvert={2}^K-{2}^{K-k}$

$If\;{x}_1=0:\lvert M(x_1) \rvert={2}^K-{2}^{K-k}$

where |M| represents the size of the set M, that is, the number of unique attributes patterns in the set M.

Proof:

-

a. Under the DINA model, for item 1

$, L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{x}_1\right)=P\left({x}_1|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)={\left(1-{s}_1\right)}^{\eta_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)}{g_1}^{1-{\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)}$

, where

$, L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{x}_1\right)=P\left({x}_1|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)={\left(1-{s}_1\right)}^{\eta_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)}{g_1}^{1-{\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)}$

, where

${\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=\prod_{k=1}^K{\alpha_k}^{q_{1k}}$

.

${\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=\prod_{k=1}^K{\alpha_k}^{q_{1k}}$

. -

b. For

${x}_1=1$

,

${x}_1=1$

,

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{x}_1=1\right)$

is maximized when

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{x}_1=1\right)$

is maximized when

${\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1$

since

${\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1$

since

$\left(1-{s}_1\right)>{g}_1$

. This requires all k attributes specified by item 1 to be mastered. The remaining

$\left(1-{s}_1\right)>{g}_1$

. This requires all k attributes specified by item 1 to be mastered. The remaining

$K-k$

attributes can be 0 or 1. Therefore,

$K-k$

attributes can be 0 or 1. Therefore,

$\lvert M(x_1) \rvert = 2^{K-k}$

.

$\lvert M(x_1) \rvert = 2^{K-k}$

. -

c. For

${x}_1=0$

,

${x}_1=0$

,

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{x}_1=0\right)$

is maximized when

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{x}_1=0\right)$

is maximized when

${\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0$

since

${\eta}_1\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0$

since

$\left(1-{g}_1\right)>{s}_1$

. This occurs when any required attribute is 0. So, in this case

$\left(1-{g}_1\right)>{s}_1$

. This occurs when any required attribute is 0. So, in this case

$\left|M\left({x}_1\right)\right|$

=

$\left|M\left({x}_1\right)\right|$

=

${2}^K-{2}^{K-k}$

.

${2}^K-{2}^{K-k}$

.

Theorem 2

(Pattern set change). After t items have been answered (

![]() $t\ge 1$

), response pattern

$t\ge 1$

), response pattern

![]() ${\boldsymbol{x}}_t$

and any new response

${\boldsymbol{x}}_t$

and any new response

![]() ${x}_j$

from item j, the set of attribute patterns with the largest likelihood is

${x}_j$

from item j, the set of attribute patterns with the largest likelihood is

Let

![]() ${M}_{1t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1\right\}$

(i.e., patterns within

${M}_{1t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1\right\}$

(i.e., patterns within

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that mastered all attributes required item j), and

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that mastered all attributes required item j), and

![]() ${M}_{0t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0\right\}$

(patterns within

${M}_{0t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0\right\}$

(patterns within

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that miss one or more attributes required by item j). The updated pattern set

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that miss one or more attributes required by item j). The updated pattern set

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

follows one of the three cases:

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

follows one of the three cases:

Case 1 (Shrinkage): If

![]() ${M}_{1t}\ne \varnothing$

, and

${M}_{1t}\ne \varnothing$

, and

![]() ${M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

(which implies

${M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

(which implies

![]() $\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\ge 2$

), then

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\ge 2$

), then

![]() $\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|<\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|$

. This occurs because item j separates patterns within

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|<\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|$

. This occurs because item j separates patterns within

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

, with at least one pattern mastering all required attributes, while others miss at least one attribute. If

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

, with at least one pattern mastering all required attributes, while others miss at least one attribute. If

![]() ${x}_j=1,M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{1t}$

; if

${x}_j=1,M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{1t}$

; if

![]() ${x}_j=0,M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{0t}$

. This is the most common case when

${x}_j=0,M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{0t}$

. This is the most common case when

![]() $\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|$

is large, which tends to be the case at the beginning of the test, especially when K is large.

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|$

is large, which tends to be the case at the beginning of the test, especially when K is large.

Case 2 (Stability): If either (a)

![]() ${M}_{1t}\ne \varnothing, {M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

and

${M}_{1t}\ne \varnothing, {M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

and

![]() ${x}_j=1$

, or (b)

${x}_j=1$

, or (b)

![]() ${M}_{1t}=\varnothing, {M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

and

${M}_{1t}=\varnothing, {M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

and

![]() ${x}_j=0$

, then

${x}_j=0$

, then

![]() $\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\rvert=\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

. This occurs when all patterns within

$\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\rvert=\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

. This occurs when all patterns within

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

lead to the same

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

lead to the same

![]() ${\eta}_j$

and the observed response

${\eta}_j$

and the observed response

![]() ${x}_j$

matches

${x}_j$

matches

![]() ${\eta}_j$

.

${\eta}_j$

.

Case 3: If (1)

![]() ${M}_{1t}=\varnothing$

and

${M}_{1t}=\varnothing$

and

![]() ${x}_j=1$

, or (2)

${x}_j=1$

, or (2)

![]() ${M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

and

${M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

and

![]() ${x}_j=0$

:

${x}_j=0$

:

-

a. Growth occurs when external patterns, i.e., patterns outside of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

, have precisely the threshold likelihood:

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

, have precisely the threshold likelihood:

$L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot \frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

for

$L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot \frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

for

${x}_j=1$

, or

${x}_j=1$

, or

$L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot \frac{s_j}{1-{g}_j}$

for

$L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot \frac{s_j}{1-{g}_j}$

for

${x}_j=0$

. Here,

${x}_j=0$

. Here,

${L}^{\ast }=L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for any

${L}^{\ast }=L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for any

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \boldsymbol{\in}M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

. This exact equality is mathematically possible but rare in practice.

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \boldsymbol{\in}M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

. This exact equality is mathematically possible but rare in practice. -

b. Replacement occurs when there exists at least one external pattern

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

leading to

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

leading to

$L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that exceeds the threshold likelihood ratio. This can result in

$L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that exceeds the threshold likelihood ratio. This can result in

$\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\rvert$

being larger, smaller, or equal to

$\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\rvert$

being larger, smaller, or equal to

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|$

depending on the number of qualifying external patterns.

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|$

depending on the number of qualifying external patterns. -

c. Stability occurs when no external patterns meet the threshold.

Proof:

Define

![]() ${A}_{1t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in \boldsymbol{A}\backslash M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1\right\}$

(i.e., patterns outside of

${A}_{1t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in \boldsymbol{A}\backslash M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1\right\}$

(i.e., patterns outside of

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that should lead to a correct answer to item j), and

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that should lead to a correct answer to item j), and

![]() ${A}_{0t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in \boldsymbol{A}\backslash M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0\right\}$

(i.e., patterns outside of

${A}_{0t}=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in \boldsymbol{A}\backslash M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right):{\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0\right\}$

(i.e., patterns outside of

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that should lead to an incorrect answer to item j). Let

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

that should lead to an incorrect answer to item j). Let

![]() ${L}^{\ast }=L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for any

${L}^{\ast }=L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for any

![]() $\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

, and

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

, and

![]() ${L}^{\ast \prime }=L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for any

${L}^{\ast \prime }=L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for any

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\notin M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

. Note that

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\notin M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

. Note that

![]() ${L}^{\ast }>{L}^{\ast \prime }$

by the definition of

${L}^{\ast }>{L}^{\ast \prime }$

by the definition of

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

.

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

.

(1) When the response

![]() ${x}_j=1$

:

${x}_j=1$

:

Under DINA, if

![]() ${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1,P\left({X}_j=1|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1-{s}_j$

; if

${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1,P\left({X}_j=1|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1-{s}_j$

; if

![]() ${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0,P\left({X}_j=1|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)={g}_j$

. Since

${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0,P\left({X}_j=1|\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)={g}_j$

. Since

![]() ${s}_j,{g}_j<0.5$

, we have

${s}_j,{g}_j<0.5$

, we have

![]() $\left(1-{s}_j\right)>{g}_j$

. After observing

$\left(1-{s}_j\right)>{g}_j$

. After observing

![]() ${x}_j=1$

:

${x}_j=1$

:

-

• For

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in {M}_{1t}:L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

.

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in {M}_{1t}:L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

. -

• For

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in {M}_{0t}:L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

.

$\boldsymbol{\alpha} \in {M}_{0t}:L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

. -

• For

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}:L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

.

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}:L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

. -

• For

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{0t}:L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot {g}_j$

.

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{0t}:L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot {g}_j$

.

Case 1: If

![]() $M_{1t} \ne \varnothing \text{ and } M_{0t} \ne \varnothing$

, then the maximum likelihood after observing

$M_{1t} \ne \varnothing \text{ and } M_{0t} \ne \varnothing$

, then the maximum likelihood after observing

![]() ${x}_j$

is

${x}_j$

is

![]() ${L}^{\ast}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

, since

${L}^{\ast}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

, since

![]() $\left(1-{s}_j\right)>{g}_j$

and

$\left(1-{s}_j\right)>{g}_j$

and

![]() ${L}^{\ast }>{L}^{\ast \prime }$

. This only happens for attribute patterns in

${L}^{\ast }>{L}^{\ast \prime }$

. This only happens for attribute patterns in

![]() ${M}_{1t}$

. Therefore,

${M}_{1t}$

. Therefore,

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

shrinks to

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

shrinks to

![]() ${M}_{1t}$

when

${M}_{1t}$

when

![]() ${M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

.

${M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

.

Case 2: If

![]() ${M}_{1t}\ne \varnothing \text{ and } {M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

(i.e.,

${M}_{1t}\ne \varnothing \text{ and } {M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

(i.e.,

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)={M}_{1t}$

), all patterns in

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)={M}_{1t}$

), all patterns in

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

achieve

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

achieve

![]() ${L}^{\ast}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

. Therefore,

${L}^{\ast}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)$

. Therefore,

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)=M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

(Stability).

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)=M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

(Stability).

Case 3: If

![]() ${M}_{1t}=\varnothing\ \mathrm{and}\;{M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

(i.e.,

${M}_{1t}=\varnothing\ \mathrm{and}\;{M}_{0t}\ne \varnothing$

(i.e.,

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)={M}_{0t}$

), all patterns in

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)={M}_{0t}$

), all patterns in

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

achieve

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

achieve

![]() ${L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

.

${L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

.

-

• For

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_0,L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot {g}_j<{L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, so those patterns do not enter

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_0,L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t,{x}_j\right)={L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot {g}_j<{L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, so those patterns do not enter

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

. Therefore, we can focus on

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

. Therefore, we can focus on

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

.

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

. -

• For

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

:

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

:-

○ if

${L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, that is,

${L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)={L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, that is,

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}=\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

, then pattern

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}=\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

, then pattern

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

ties with patterns in

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

ties with patterns in

${M}_{0t}$

and becomes a part of

${M}_{0t}$

and becomes a part of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

(growth);

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

(growth); -

○ if

${L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)>{L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, that is,

${L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)>{L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, that is,

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}>\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

, then pattern

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}>\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

, then pattern

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

achieves a higher likelihood than all patterns in

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

achieves a higher likelihood than all patterns in

${M}_{0t}$

, so

${M}_{0t}$

, so

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}:L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)>{L}^{\ast}\cdot \frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}\right\}$

(replacement), and the size of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}:L\left({\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }|{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)>{L}^{\ast}\cdot \frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}\right\}$

(replacement), and the size of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

may increase, decrease, or remain unchanged relative to the size of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

may increase, decrease, or remain unchanged relative to the size of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

;

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

; -

○ if

${L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)<{L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, that is,

${L}^{\ast \prime}\cdot \left(1-{s}_j\right)<{L}^{\ast}\cdot {g}_j$

, that is,

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}<\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

, then pattern

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}<\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

, then pattern

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

doesn’t become a member of

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime }$

doesn’t become a member of

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

, so

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

, so

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{0t}=M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

(stability).

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{0t}=M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

(stability).

-

Therefore, when

![]() ${x}_j=1$

, for

${x}_j=1$

, for

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

to expand beyond

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

to expand beyond

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

,

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

,

![]() $\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}$

must be at least as large as

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}$

must be at least as large as

![]() $\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

. If equality holds for some patterns

$\frac{g_j}{1-{s}_j}$

. If equality holds for some patterns

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

, growth occurs; if inequality holds for some patterns

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

, growth occurs; if inequality holds for some patterns

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

, replacement occurs; if no external patterns meets threshold, stability occurs.

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{1t}$

, replacement occurs; if no external patterns meets threshold, stability occurs.

(2) When the response

![]() ${x}_j=0$

, the same logic applies. Whether the size of

${x}_j=0$

, the same logic applies. Whether the size of

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

increases or shrinks compared to

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

increases or shrinks compared to

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

depends on

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

depends on

![]() $\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}$

and

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}$

and

![]() $\frac{s_j}{1-{g}_j}$

. If they are equal for some patterns

$\frac{s_j}{1-{g}_j}$

. If they are equal for some patterns

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{0t}$

, the size increases; if

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{0t}$

, the size increases; if

![]() $\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}>\frac{s_j}{1-{g}_j}$

holds for some patterns

$\frac{L^{\ast \prime }}{L^{\ast }}>\frac{s_j}{1-{g}_j}$

holds for some patterns

![]() ${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{0t}$

, the size may increase, remain stable, or decrease.

${\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\prime}\in {A}_{0t}$

, the size may increase, remain stable, or decrease.

A special case: When

![]() $\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

= 1

$\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

= 1

A critical scenario arises when the pattern set contains only a single pattern:

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\ast}\right\}$

. This situation may arise at a late stage of a test. With only one pattern, Case 1 (i.e., mixed mastery) in Theorem 2 is impossible. The single pattern either meets item j’s requirements (

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\ast}\right\}$

. This situation may arise at a late stage of a test. With only one pattern, Case 1 (i.e., mixed mastery) in Theorem 2 is impossible. The single pattern either meets item j’s requirements (

![]() ${M}_{1t}=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\ast}\right\},{M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

) or doesn’t (

${M}_{1t}=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\ast}\right\},{M}_{0t}=\varnothing$

) or doesn’t (

![]() ${M}_{1t}=\varnothing, {M}_{0t}=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\ast}\right\}$

). This is a special case of either Case 2 or Case 3 discussed in Theorem 2. According to Theorem 2,

${M}_{1t}=\varnothing, {M}_{0t}=\left\{{\boldsymbol{\alpha}}^{\ast}\right\}$

). This is a special case of either Case 2 or Case 3 discussed in Theorem 2. According to Theorem 2,

![]() $\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

either stays at 1 or possibly expands. There is no chance of further shrinkage in terms of the size of the set.

$\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

either stays at 1 or possibly expands. There is no chance of further shrinkage in terms of the size of the set.

Conditions driving shrinkage in LBPS. The probability of shrinkage (Case 1) in Theorem 2 depends critically on heterogeneity within

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

—that is, whether some patterns meet all requirements of item j, while others do not. This heterogeneity is likely to occur when K is large and testing is in early stages, due to the combinatorial structure of the pattern space. After t items which have tested m < K attributes,

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

—that is, whether some patterns meet all requirements of item j, while others do not. This heterogeneity is likely to occur when K is large and testing is in early stages, due to the combinatorial structure of the pattern space. After t items which have tested m < K attributes,

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

must contain all

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

must contain all

![]() ${2}^{K-m}$

variants on untested attributes for each viable tested configuration. This ensures a diverse set of attribute patterns that item j can potentially differentiate.

${2}^{K-m}$

variants on untested attributes for each viable tested configuration. This ensures a diverse set of attribute patterns that item j can potentially differentiate.

While early stages benefit from guaranteed shrinkage, repeated shrinkage often drives

![]() $\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

to a small number of patterns at the later stage of testing. This results in a computational advantage: with LBPS, item selection methods like KL, PWKL, or SHE need to evaluate items against only a handful of patterns remaining in

$\lvert M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\rvert$

to a small number of patterns at the later stage of testing. This results in a computational advantage: with LBPS, item selection methods like KL, PWKL, or SHE need to evaluate items against only a handful of patterns remaining in

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

; while without LBPS, they must evaluate all

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

; while without LBPS, they must evaluate all

![]() ${2}^K$

patterns at every stage. Thus, LBPS effectively leverages the structure of high-dimensional attribute spaces to mitigate the computational burden of exhaustive pattern evaluation. Its advantage is pronounced when K is large, offering the greatest benefit precisely when traditional methods become computationally prohibitive.

${2}^K$

patterns at every stage. Thus, LBPS effectively leverages the structure of high-dimensional attribute spaces to mitigate the computational burden of exhaustive pattern evaluation. Its advantage is pronounced when K is large, offering the greatest benefit precisely when traditional methods become computationally prohibitive.

Theorem 3

(Pattern set size reduction). General reduction: When Case 1 (shrinkage) occurs, the reduction in the pattern set size of

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

is

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

is

$$\begin{align*}\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\left|{M}_{1t}\right|,\quad if\;{x}_j=1,\\ {}\left|{M}_{0t}\right|,\quad if\;{x}_j=0.\end{array}\right.\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\left|{M}_{1t}\right|,\quad if\;{x}_j=1,\\ {}\left|{M}_{0t}\right|,\quad if\;{x}_j=0.\end{array}\right.\end{align*}$$

The reduction ratio is

${p}_j=\frac{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|}{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\frac{\left|{M}_{1t}\right|}{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|},\quad if\;{x}_j=1,\\ {}\frac{\left|{M}_{0t}\right|}{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|},\quad if\;{x}_j=0.\end{array}\right.$

${p}_j=\frac{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|}{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\frac{\left|{M}_{1t}\right|}{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|},\quad if\;{x}_j=1,\\ {}\frac{\left|{M}_{0t}\right|}{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|},\quad if\;{x}_j=0.\end{array}\right.$

This ratio depends on the proportion of patterns in

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

that would ideally yield each response. As a special case, when item j measures only untested attributes:

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

that would ideally yield each response. As a special case, when item j measures only untested attributes:

-

1.

$If\;{x}_j=1:\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\cdot \frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}$

$If\;{x}_j=1:\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\cdot \frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}$

-

2.

$If\;{x}_j=0:\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\cdot \left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}\right)$

$If\;{x}_j=0:\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\cdot \left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}\right)$

Here,

![]() ${k}_{new}$

refers to the number of newly introduced attributes—that is, attributes required by item j but not yet assessed by any of the first t items. When

${k}_{new}$

refers to the number of newly introduced attributes—that is, attributes required by item j but not yet assessed by any of the first t items. When

![]() ${k}_{new}>1$

, the reduction of the most likely pattern space is sharper for a correct response (

${k}_{new}>1$

, the reduction of the most likely pattern space is sharper for a correct response (

![]() ${x}_j=1$

), and less sharp but still substantial for an incorrect response (

${x}_j=1$

), and less sharp but still substantial for an incorrect response (

![]() ${x}_j=0$

). When

${x}_j=0$

). When

![]() ${k}_{new}=1$

, the reduction is by half for a correct response or an incorrect response.

${k}_{new}=1$

, the reduction is by half for a correct response or an incorrect response.

Proof: This follows directly from Case 1 of Theorem 2, where we showed that

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{1t}$

when

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{1t}$

when

![]() ${x}_j=1$

and

${x}_j=1$

and

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{0t}$

when

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)={M}_{0t}$

when

![]() ${x}_j=0$

.

${x}_j=0$

.

For the special case:

-

a. When

${x}_j=1$

,

${x}_j=1$

,

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

is maximized when

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

is maximized when

${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1$

. This means that each new required attribute must be mastered. Only

${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1$

. This means that each new required attribute must be mastered. Only

$\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}$

of all patterns in

$\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}$

of all patterns in

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

can have 1’s on all the new attributes. Therefore,

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

can have 1’s on all the new attributes. Therefore,

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\frac{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|}{2^{k_{new}}}$

.

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\frac{\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|}{2^{k_{new}}}$

. -

b. When

${x}_j=0$

,

${x}_j=0$

,

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

is maximized when

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)$

is maximized when

${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0$

. This means that at least one of the new required attributes is not mastered, and the proportion of such patterns in

${\eta}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=0$

. This means that at least one of the new required attributes is not mastered, and the proportion of such patterns in

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

is

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)$

is

$1-\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}$

. Therefore,

$1-\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}$

. Therefore,

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\cdot \left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}\right)$

.

$\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}},{x}_j\right)\right|=\left|M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_{\boldsymbol{t}}\right)\right|\cdot \left(1-\frac{1}{2^{k_{new}}}\right)$

.

When

![]() ${k}_{new}=1$

, following a) and b), the size of the set of attribute patterns that maximize the likelihood is reduced by half.

${k}_{new}=1$

, following a) and b), the size of the set of attribute patterns that maximize the likelihood is reduced by half.

The aforementioned theorems suggest that the efficiency of LBPS is influenced by the q-vectors of the selected items. The sequential selection of items that assess new attributes leads to a reduced pattern space for item selection in LBPS. This insight coincides with Xu et al.’s (Reference Xu, Wang and Shang2016) optimal initial item selection theory for CD-CAT. Specifically, Xu et al. (Reference Xu, Wang and Shang2016) demonstrated that to achieve minimum test length, the first administered item must assess exactly one attribute, followed by items that sequentially introduce single, previously unmeasured attributes. If this condition is not met, identifying all attribute profiles within K items becomes infeasible, resulting in test lengths exceeding K. If the condition is met, following Theorems 2 and 2, LBPS should help shrink the search space by half at each step during the early stage of the test when K is large, thereby achieving substantial computational gains.

Note that the above theorems are built on the DINA model, but they can be extended to other CDMs with ideal response functions. For example, for the DINO model with

![]() ${\omega}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1-\prod_{k=1}^K\left(1-{\alpha_k}^{q_{jk}}\right)$

, the theorems hold with

${\omega}_j\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} \right)=1-\prod_{k=1}^K\left(1-{\alpha_k}^{q_{jk}}\right)$

, the theorems hold with

![]() ${\omega}_j$

replacing

${\omega}_j$

replacing

![]() ${\eta}_j$

. For CDMs without ideal response functions (e.g., general CDMs such as LCDM and G-DINA), LBPS can still be implemented, as it operates directly on likelihood values and relies on likelihood updating. Shrinkage of

${\eta}_j$

. For CDMs without ideal response functions (e.g., general CDMs such as LCDM and G-DINA), LBPS can still be implemented, as it operates directly on likelihood values and relies on likelihood updating. Shrinkage of

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

may occur when patterns within

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

may occur when patterns within

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

yield different response probabilities, because likelihood updating favors patterns whose predicted probabilities better align with the observed outcome. Such behavior is more likely when

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

yield different response probabilities, because likelihood updating favors patterns whose predicted probabilities better align with the observed outcome. Such behavior is more likely when

![]() $\mid M\left({x}_t\right)\mid$

is large, as characterized under the DINA model. That said, the specific theoretical properties established in this article (e.g., the characterization of shrinkage via

$\mid M\left({x}_t\right)\mid$

is large, as characterized under the DINA model. That said, the specific theoretical properties established in this article (e.g., the characterization of shrinkage via

![]() ${M}_{1t}$

and

${M}_{1t}$

and

![]() ${M}_{0t}$

) do not directly apply, and further investigation of LBPS performance under these models is needed.

${M}_{0t}$

) do not directly apply, and further investigation of LBPS performance under these models is needed.

While the above theorems demonstrate how the set of potential likely attribute patterns changes with each item response, practical implementation requires a concrete algorithm. The following section outlines the step-by-step LBPS procedure.

3.3 Algorithm description

The LBPS algorithm maintains two key sets: (1)

![]() $M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

: most likely patterns or patterns that lead to the maximum likelihood, and (2)

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

: most likely patterns or patterns that lead to the maximum likelihood, and (2)

![]() ${M}^{\ast}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

: working pattern set used for item selection. Note that the estimation of each examinee’s attribute profile uses the full pattern space (all possible

${M}^{\ast}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

: working pattern set used for item selection. Note that the estimation of each examinee’s attribute profile uses the full pattern space (all possible

![]() ${2}^K$

attribute profiles); the working pattern set is only used for item selection. In terms of the working set size, at any stage t,

${2}^K$

attribute profiles); the working pattern set is only used for item selection. In terms of the working set size, at any stage t,

![]() $2\le \mid {M}^{\ast}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)\mid \le {2}^K$

. This ensures minimally two distinct patterns for item selection decisions. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

$2\le \mid {M}^{\ast}\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)\mid \le {2}^K$

. This ensures minimally two distinct patterns for item selection decisions. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

Step 1: First item selection

-

a. Use full pattern space A

-

b. Select an item using the traditional method (or randomization)

-

c. Obtain response

${x}_1$

${x}_1$

-

d. Calculate

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for all α ∈ A

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for all α ∈ A -

e. Define initial

$\mathrm{M}({x}_1) $

and

$\mathrm{M}({x}_1) $

and

${M}^{\ast}({x}_1)$

:

${M}^{\ast}({x}_1)$

:

$\mathrm{M}({x}_1)$

is the set of attribute patterns with the largest likelihood after the first item has been answered.

$\mathrm{M}({x}_1)$

is the set of attribute patterns with the largest likelihood after the first item has been answered.

${M}^{\ast}({x}_1)$

is the working pattern set used for item selection defined as follows:where

${M}^{\ast}({x}_1)$

is the working pattern set used for item selection defined as follows:where $$\begin{align*}{M}^{\ast}\left({x}_1\right)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{M}\left({x}_1\right),\quad \mathrm{if}\;\left|\mathrm{M}\left({x}_1\right)\right|\ge 2,\\ {}\left\{{\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(1)}^1,{\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(2)}^1\right\},\quad \mathrm{if}\;\left|\mathrm{M}\left({x}_1\right)\right|=1,\end{array}\right.\end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}{M}^{\ast}\left({x}_1\right)=\left\{\begin{array}{c}\mathrm{M}\left({x}_1\right),\quad \mathrm{if}\;\left|\mathrm{M}\left({x}_1\right)\right|\ge 2,\\ {}\left\{{\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(1)}^1,{\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(2)}^1\right\},\quad \mathrm{if}\;\left|\mathrm{M}\left({x}_1\right)\right|=1,\end{array}\right.\end{align*}$$

${\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(1)}^1$

has maximum likelihood and

${\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(1)}^1$

has maximum likelihood and

${\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(2)}^1$

has the second-highest likelihood at stage 1 (t = 1).

${\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3b1}}}_{(2)}^1$

has the second-highest likelihood at stage 1 (t = 1).

-

f. Estimate the examinee’s attribute profile (using full pattern space A) based on the response

$\mathrm{M}({x}_1)$

using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE).

$\mathrm{M}({x}_1)$

using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE).

Step 2: Subsequent items (t > 1)

For each eligible item in the pool:

-

a. Pattern space update

-

○ Calculate

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for all α ∈ A

$L\left(\boldsymbol{\alpha} |{\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)$

for all α ∈ A -

○ Identify

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} :L\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)={L}^{\ast}\right\}$

,

$M\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)=\left\{\boldsymbol{\alpha} :L\left({\boldsymbol{x}}_t\right)={L}^{\ast}\right\}$

,

${L}^{\ast }$

is the current maximum likelihood value among all profiles’ likelihoods

${L}^{\ast }$

is the current maximum likelihood value among all profiles’ likelihoods -

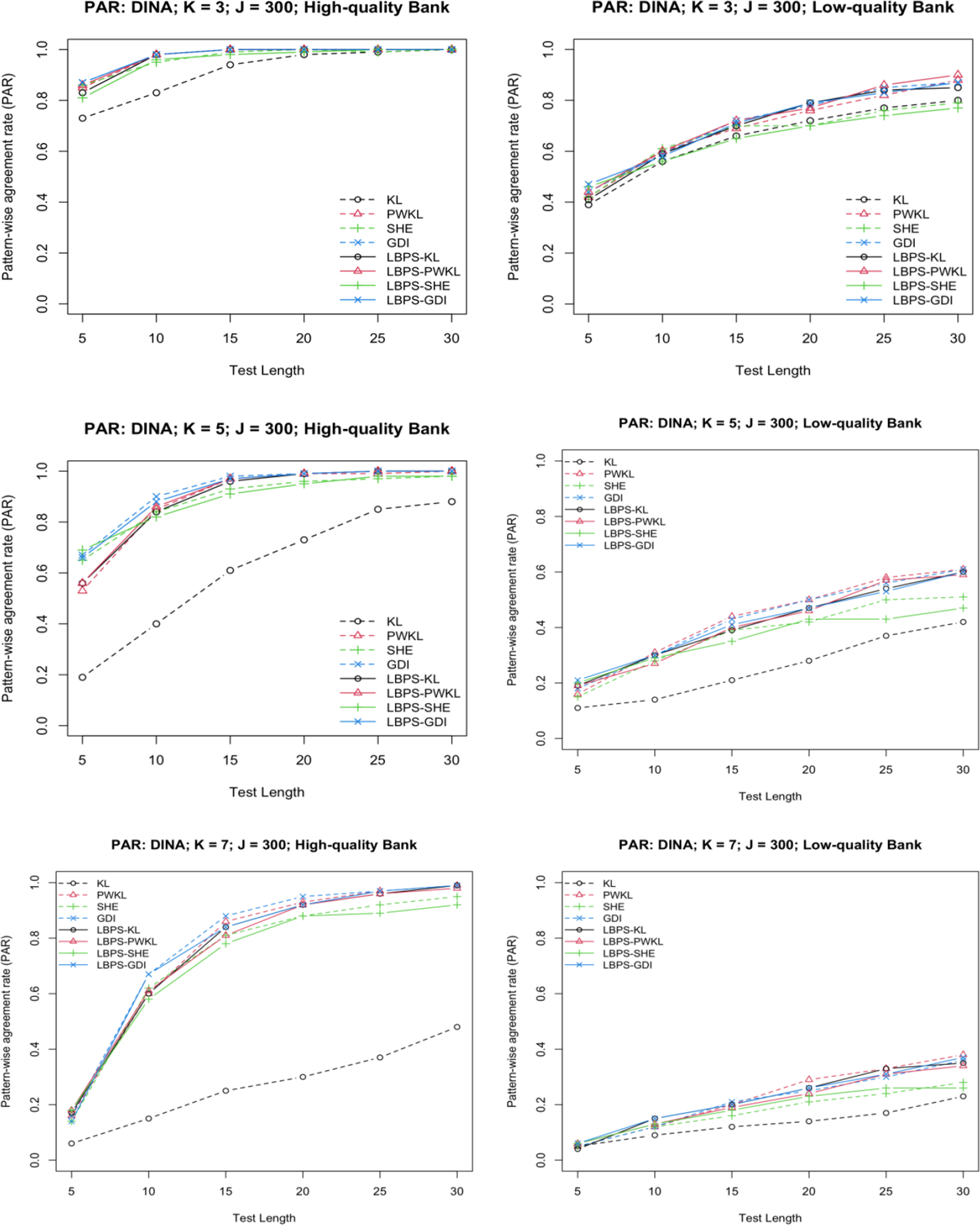

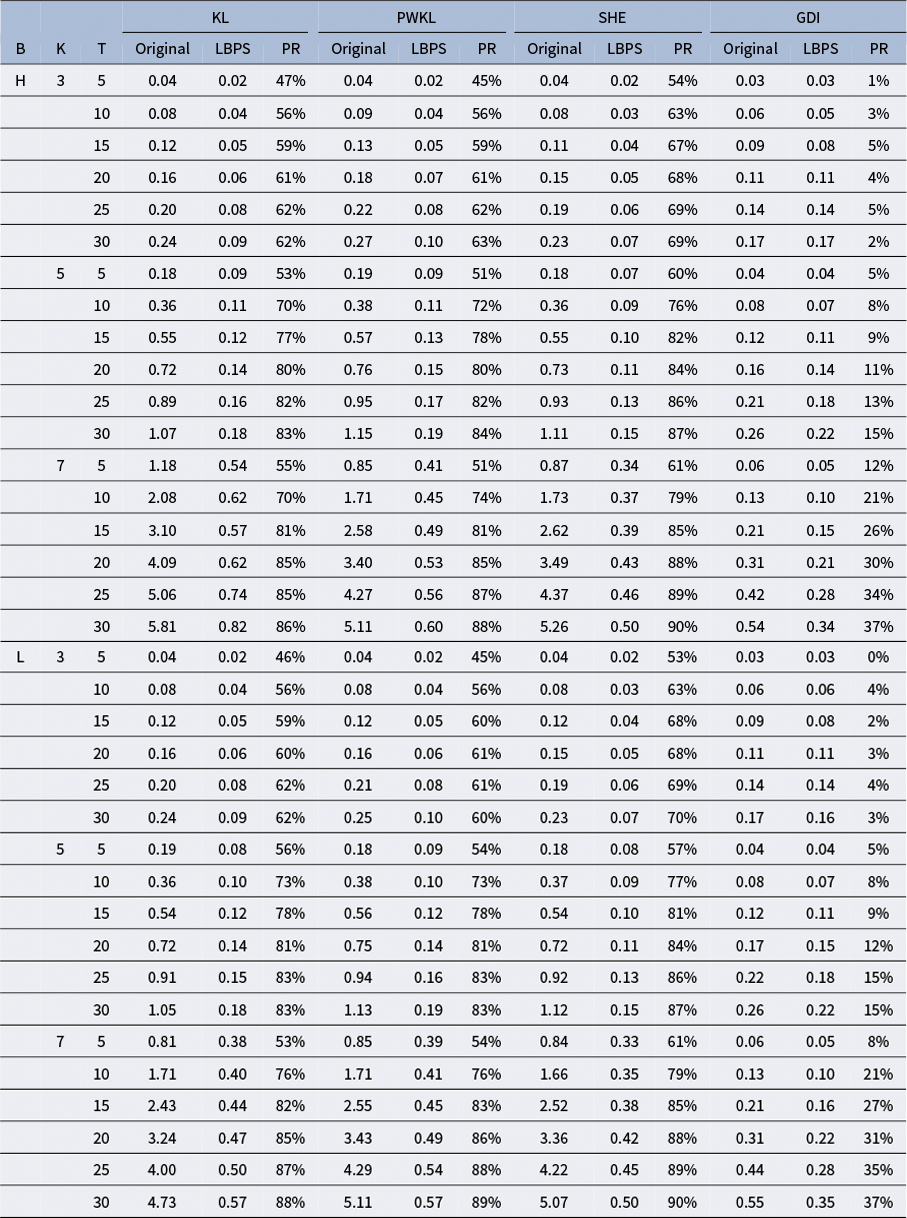

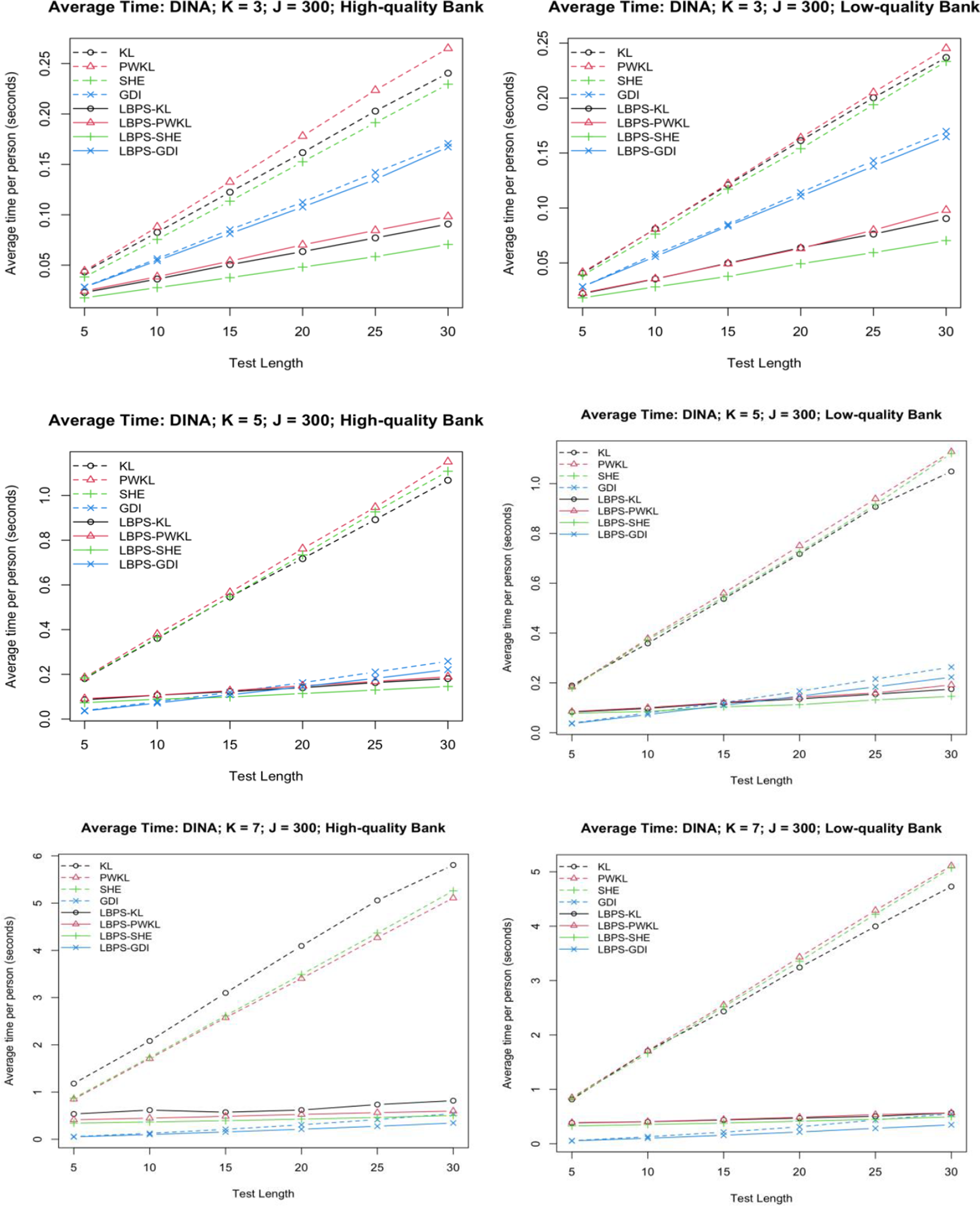

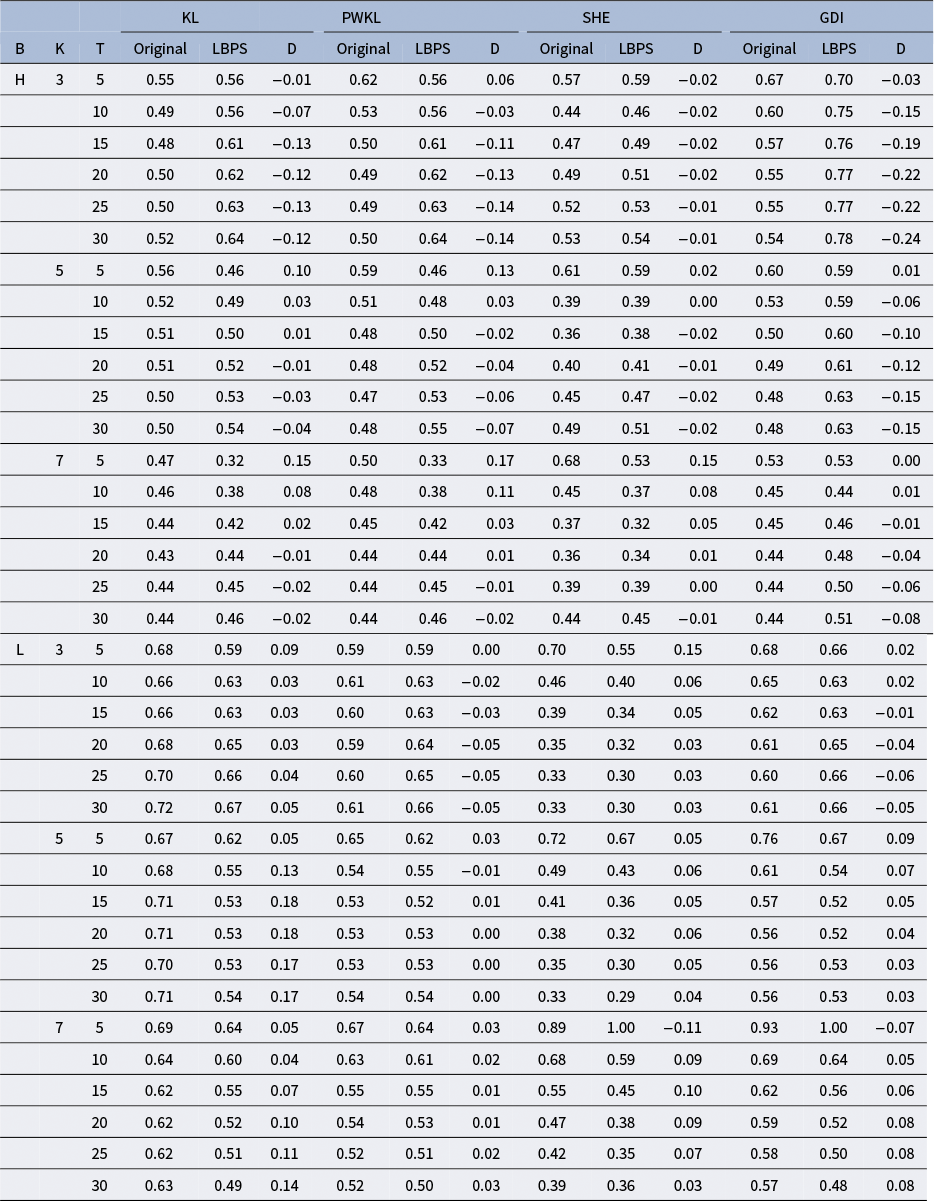

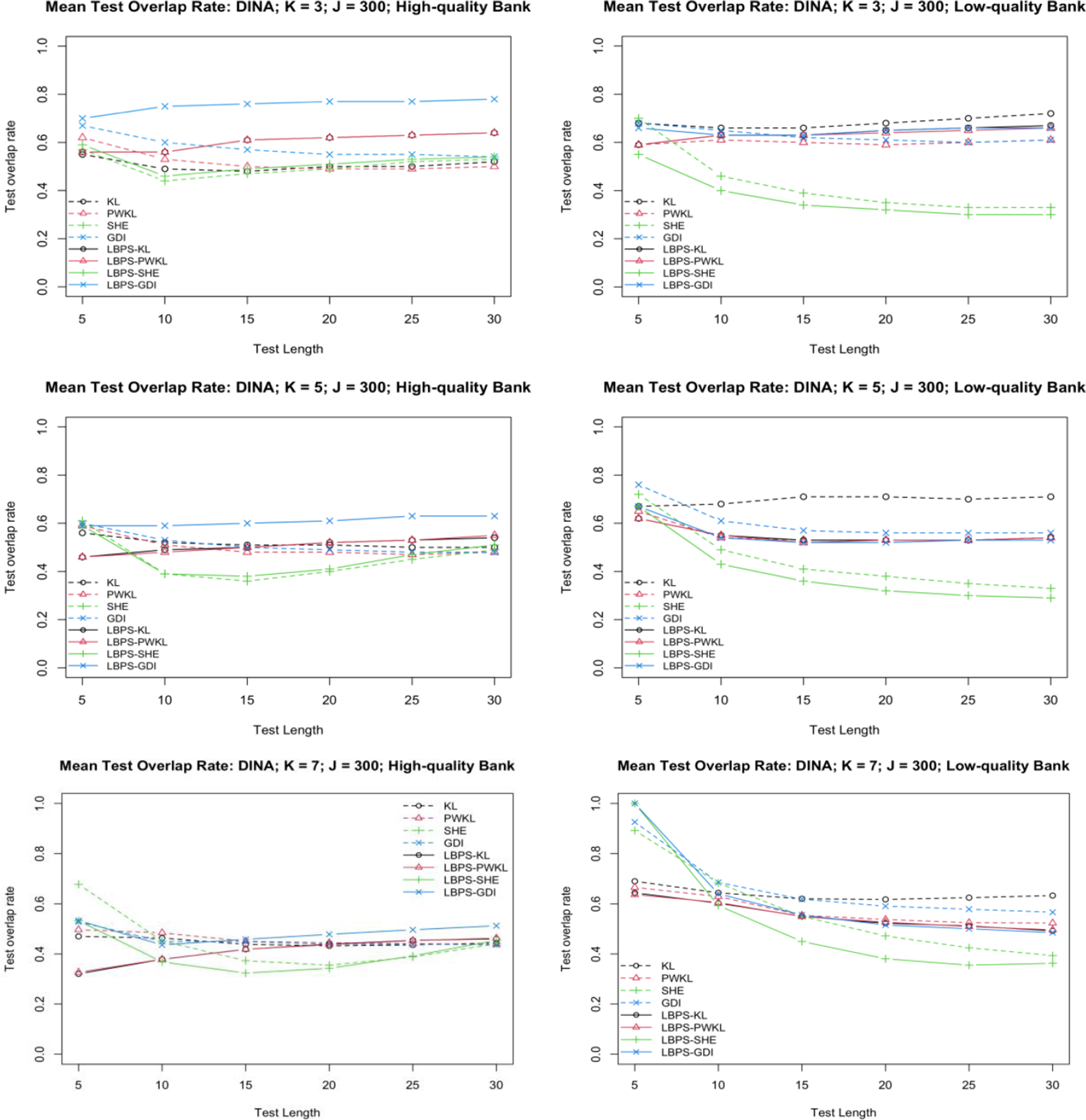

○ Define working set: