Unilever first marketed the leading Clearblue brand of home pregnancy test in the mid-1980s. Since then home pregnancy tests have become a ubiquitous and highly familiar reproductive technology and diagnostic tool. Though also displayed in women's magazines, online and on pharmacy shelves, the plastic prognostic sticks are nowhere more strikingly and memorably advertised than when used as props in film and television drama. A particularly versatile trope, pregnancy testing can be accommodated in a range of narratives, including those about teenage pregnancy, single motherhood, romantic love, infertility, abortion or some combination thereof. Frequently portrayed on screen, a typical sequence of shots will link the self-tester's intent downward gaze to a close-up of the small, hand-held object, and a reaction shot of her delighted, disappointed or distraught face. Where did this highly stylized aesthetic convention come from and what can it teach us about the contribution of factors such as product placement to changing mores concerning the public visibility of reproduction?

Considering the present-day visibility of pregnancy testing, surprisingly little is known about its history.Footnote 1 For the US, historian Sarah A. Leavitt has interpreted the ‘regular appearance’ of home tests in Hollywood cinema and on American television as a ‘sure sign’ that they have ‘entered the public consciousness’.Footnote 2 Leavitt surveys plots and explicates the narrative function of pregnancy testing but does little to historicize the entertainment industry that produced dramatic scenes and storylines for public consumption. Lauren Rosewarne, in her investigation of menstruation in film and television, suggests that taboos against openly discussing or showing menstrual blood contributed to the rise of the visually innocuous plastic stick.Footnote 3 And cultural-branding strategists have detailed the process whereby they aligned a 2006 television advertising campaign for Clearblue Digital with ‘third-wave’ ‘body-positive’ feminism by frankly showing urine for the first time.Footnote 4 But we still lack anything resembling a historical account of how the on-screen trope of pregnancy testing became conventional or how it contributed to the normalization of pregnancy testing and, more generally, to a changing and increasingly public culture of reproduction.

This article will attempt to show how the convergent aesthetic conventions of televisual and cinematic pregnancy testing took shape and became constitutive of Britain's increasingly public culture of reproduction in the late 1980s and early 1990s. The politically tumultuous 1980s, a little-studied decade, saw an intensification of public interest in issues around human reproduction.Footnote 5 From the highly publicized birth in 1978 of Louise Brown, the first ‘test-tube baby’, to the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 1990, the tabloid press, parliamentary debate and lobbying focused public scrutiny on IVF.Footnote 6 Margaret Thatcher's Conservative Party, elected in 1979, emphasized ‘family values’; a series of private member's bills and the fledgling anti-abortion movement challenged various aspects of legal abortion; Victoria Gillick, a devoutly Catholic mother of ten, campaigned against the provision of contraception to minors; Mary Whitehouse railed against sex on television; and New Labour renewed the government's commitment to tackling ‘teenage pregnancy’ in the early 1990s.Footnote 7 Meanwhile, unprecedentedly expensive and sophisticated marketing campaigns competed to stock pharmacy shelves with rival home pregnancy and ovulation test kits, aimed at a newly defined category of consumer: the older career woman trying to conceive.Footnote 8

Products of a British boom in entrepreneurial biotechnology that coincided with NHS cutbacks and the rise in health consumerism, home pregnancy tests rapidly emerged as the most lucrative sector of the commercial diagnostics industry.Footnote 9 In 1990, women in England and Wales were responsible for buying an estimated 4.8 million pregnancy tests, or around seven for every live birth.Footnote 10 Competition between Clearblue (Unipath), Discover (Carter Wallace), First Response (Tambrands) and Predictor (Chefaro) resulted in advertisements in women's magazines and, with help from Britain's nascent product-placement industry, in television programmes and films shown in cinemas.

British cinema and television became unusually closely related in the 1980s, when Channel 4 (the fourth terrestrial channel after BBC1, BBC2 and ITV) quickly rose to prominence as a major player in the film industry.Footnote 11 This article builds on research going back to Raymond Williams's Television: Technology and Cultural Form (1974), the classic ‘television studies’ book that also discussed cinema.Footnote 12 It does so by using the pregnancy-test scene to investigate British cinema and television's shared technological resources, genre preoccupations and aesthetic sensibilities. Along the way, it extends film theory's renewed interest in the close-up by exploring the conventionalized sequence of shots that typically link a close-up of the tester's expressive face with that of a small, but dramatically charged, hand-held object – the home pregnancy test.Footnote 13 Based on primary research in disparate paper, video and digital archives, it begins by setting the scene leading up to 1971, when Predictor, Britain's first home pregnancy test, debuted.

Laboratories, toads and Predictor

The Aschheim–Zondek test, invented in Berlin in the late 1920s, was the first laboratory pregnancy test to become widely adopted in Britain. It involved injecting women's urine into female mice or rabbits and then dissecting the animals to inspect the ovaries for visible, physiological changes caused by the ‘pregnancy hormone’ today known as hCG (human chorionic gonadotrophin). Gory illustrations of the ‘bioassay’ took their place in journal articles and medical textbooks alongside schematic depictions of gynaecological examination.Footnote 14 But beyond highly specialized publications, visualizations were scarce. Laboratories dealt only with doctors and kept a low profile at a time when animal research was frowned on and pregnancy testing was a ‘thoroughly unmentionable subject’.Footnote 15

The adoption by the NHS of Xenopus laevis – a toad from South Africa that laid large, visible eggs when injected with human pregnancy urine and so did not have to be dissected in the course of a test – increased the efficiency, cost-effectiveness and social acceptability of pregnancy diagnosis after the Second World War.Footnote 16 It was around this time that the first silent 16 mm films of laboratory pregnancy testing began to circulate. In the late 1940s, Brian Stanford, a London doctor and medical filmmaker, produced The Aschheim–Zondek Test for Pregnancy (in colour) and the pharmaceutical laboratories of the Basel-based chemical company Ciba produced The South African Clawed Toad (in black and white), which covered various aspects of the life cycle of Xenopus, as well as its use in human pregnancy testing (Figure 1).Footnote 17

Figure 1. Screen captures from The South African Clawed Toad (Rolf Meier, c.1946) showing (from top left to bottom right): title card, urine injection, test toad and an ‘extremely positive reaction’. The wire mesh, clearly visible in the bottom left image, was used in some laboratories to prevent the toad from ruining the test by devouring her own eggs. Copyright Novartis International Ltd.

Both films were made for doctors by doctors. The general public remained more or less in the dark about the use of animals in pregnancy testing.Footnote 18 Women's magazines and pregnancy advice manuals occasionally mentioned bioassays in the 1930s and 1940s, but typically discouraged pregnancy testing as an expensive luxury.Footnote 19 Only in 1961 did the popular magazine Woman endorse the toad test as a ‘modern scientific achievement’, and then only in response to concerns about Primodos, a controversial pregnancy-test drug that induced uterine bleeding and was suspected of causing miscarriages and birth defects.Footnote 20 Medical discretion gave way to open public debate in 1965, when commercial laboratories began advertising directly to women not as patients, but as consumers.Footnote 21 By then, mass-produced immunological test kits had supplanted living animals and a ‘huge shift’ in vocabulary had occurred. Previously unmentionable words such as ‘pregnancy’, ‘abortion’ and ‘termination’ were more frequently printed in the press, novels and private letters.Footnote 22 Pregnancy testing, though generally missing from histories of the ‘sexual revolution’, was hotly debated in newspapers and magazines alongside the closely related issues of contraception and abortion.Footnote 23

In 1965, laboratories began taking out classified adverts for their diagnostic services. The standard fee of two pounds a test was equivalent to about a week's rent in Leeds in 1968.Footnote 24 Belmont Laboratories, the largest and most enterprising, fuelled the controversy by placing posters in British Rail and London Underground stations. Some doctors complained, but progressive journalists increasingly portrayed the medical profession as paternalistic and out of step with public opinion. Novelists including Lynne Reid Banks, Anthony Burgess, David Lodge and Andrea Newman narrated pregnancy testing in the 1960s.Footnote 25 By the end of the decade, pregnancy testing confronted not only readers, but also radio listeners, television viewers and cinema-goers.

A 1960s ‘media revolution’ made sex and reproduction more publicly visible than ever before.Footnote 26 British ‘kitchen sink’ cinema contributed to it by audaciously confronting audiences with challenging issues including juvenile delinquency, homosexuality, teenage pregnancy, mixed-race relationships, unmarried motherhood and illegal ‘backstreet’ abortion.Footnote 27 A missed menstrual period, morning sickness or quickening typically confirmed pregnancy in these films. Often the pregnant character was a young, working-class woman who could not have afforded a test anyway. In Tony Richardson's adaptation of Shelagh Delaney's 1958 play A Taste of Honey (1961), pregnant schoolgirl Jo (Rita Tushingham) is exhilarated when she feels her baby's first kick as a thunderstorm is brewing. The philandering eponymous antihero (Michael Caine) of Bill Naughton's Alfie (1966) is alerted by a calendar to his girlfriend's condition (Figure 2A). And pregnancy is disclosed when a factory girl runs to the lavatory to be sick in Up the Junction (1968). Only Waris Hussein's A Touch of Love (1969), based on Margaret Drabble's novel The Millstone (1965), portrayed a ‘positive’ pregnancy test result (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Screen captures from (A) Alfie (Lewis Gilbert, 1966), produced by Lewis Gilbert and Sheldrake Films, distributed by the BFI; (B) A Touch of Love (Waris Hussein, 1969), produced by Amicus and Palomar, courtesy of STUDIOCANAL Films Ltd.

The opening sequence of A Touch of Love, also known as Thank You All Very Much, shows the decidedly middle-class lead, Rosamund Stacey (Sandy Dennis), restlessly circling her lab report in the British Museum reading room, where she is unable to concentrate on her doctoral thesis. The full name of the lab falls outside the frame, but the visible address and postcode identify its provenance as Belmont Laboratories. The earliest cinematic pregnancy test I have seen, the report was probably ‘chosen by a diligent prop man who had done his research and used an actual address’.Footnote 28 Less a trendsetter than an early outlier, Rosamund's lab report is a testament to the degree of publicity stirred up by Belmont and other diagnostic services in the late 1960s.

On BBC1's evening news magazine programme 24 Hours (10 September 1969) the director of Belmont Laboratories explained that it was ‘the woman's prerogative to know if she was pregnant as quickly as possible’.Footnote 29 The BBC1 documentary Mother's Pride (12 February 1971) linked pregnancy testing to a woman's decision to have an abortion, while ‘Congratulations it's a toad’ (4 April 1971), a cheeky episode of London Weekend Television's medical sitcom Doctors at Large, made light of the use of toads and urine for human pregnancy diagnosis. On BBC Radio 2, Woman's Hour (6 March 1970) investigated commercial laboratories, while on Radio 4 You and Yours (13 January 1972) reported on the first self-testing kits.Footnote 30

By the time Chefaro, a subsidiary of the Dutch pharmaceutical company Organon, launched Predictor in 1971, Belmont and other labs had already cultivated a sizable market. Research commissioned by Chefaro found that two-thirds of women aged fifteen to forty-four had already heard of laboratory tests for pregnancy and 62 per cent agreed with the statement ‘It is an excellent method for checking up before going to the doctor’.Footnote 31 Predictor initially retailed for £1.75, just under the going rate for a laboratory test, and was supported by a £60,000 advertising campaign aimed directly at consumers.Footnote 32 An advertisement in the free London magazine Girl about Town (14 June 1976) compared the ‘pregnancy test you do yourself’ to the ease of ‘buying a lipstick’. But the consumer watchdog organization Which? warned that ‘clumsy’ users ‘could get a wrong result, and waste almost £2’; many women continued to rely on doctors, family-planning clinics, chemists and women's centres.Footnote 33 Whereas advice literature before the 1960s discouraged laboratory pregnancy testing, Which? endorsed diagnostic services. In deference to medical authority, however, it stopped short of recommending home test kits. In 1982 Which? described Predictor (now £4.75) and its sole competitor, Carter Wallace's Discover-2 (£5.25), as ‘fiddly to use’.Footnote 34

Women's afternoon television programming frankly discussed pregnancy and childbirth in the 1950s.Footnote 35 Dramas, however, typically elided the process of realization or discovery. For instance, in the very first series of Coronation Street (1960), Linda simply tells her husband that she is expecting, while unabashedly smoking a cigarette.Footnote 36 Some sixteen years and more than 1,500 episodes later, the classic ITV serial had the Langtons anxiously waiting for a doctor to communicate the result of Deirdre's pregnancy test.Footnote 37 In the 1980s, Penny (Jan Francis) and Vince (Paul Nicholas) spend an entire episode of the popular sitcom Just Good Friends (BBC1, 1984) contemplating the future while waiting for a doctor to divulge the result of Penny's pregnancy test.Footnote 38 Parents discuss their teenage daughter's lab report over breakfast in the bilingual sketch comedy programme Let's Parlez Franglais (Channel 4, 1984). Rehana (Meera Syal) advises her friend to ‘see a doctor and get a pregnancy test’ in Majdhar (Channel 4, 1985), a film about immigration and arranged marriage. And the comedy serial The Two of Us (ITV, 1990) ends with the unmarried Elaine Walker (Janet Dibley) telephoning her doctor about a pregnancy test, the result of which is never disclosed to viewers.

Beyond drama and comedy, non-fiction television occasionally went behind the scenes to show laboratory pregnancy testing in action.Footnote 39 The London Programme (LWT, 1978) reused old footage from Ciba's Xenopus film and showed the new rapid slide test in action in a documentary about Primodos (Figure 3).Footnote 40 Peter Williams's Test Tube Explosion (ITV, 1982), timed to coincide with the start of the high-profile public ‘Warnock inquiry’ into IVF and human-embryo research, linked pregnancy testing to a treatment regime that left patients impatiently waiting by the phone to see if they would ‘hold on to their pregnancies’.Footnote 41 And in 1987, an ITV news report on the Alton Bill, which aimed to curb late abortions, showed pregnancy testing by the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS), a leading abortion provider.Footnote 42 From the mid-1980s, however, serialized drama became the main vehicle for beaming pregnancy tests into British homes.

Figure 3. Screen captures from The London Programme, Production Number 22561, recorded on 13 April 1978. Presented by Godfrey Hodgson, produced by Barry Cox, report by Greg Dyke.

Socially engaged drama and realism on television

Television dramas in the 1960s and 1970s were typically shot on video in a studio, where it was common to change the composition of the shot by physically moving the (cumbersome and heavy) camera closer to or further from the action, rather than by cutting in post-production. Tight production schedules and budgetary constraints left little time or money for experimentation, and most television dramas followed the standard visual ‘grammar’ of wide shots of set and closer shots of main characters, alternating with close-ups in a very conventionalized system.Footnote 43 Then, in the early 1980s, a new kind of evening soap opera pioneered by Brookside and EastEnders created new narrative and aesthetic possibilities – including for pregnancy testing.

Commissioned from Mersey Television, a small, independent production company run by Phil Redmond, Channel 4's Brookside was filmed not in a studio, but on location at a suburban housing estate on the outskirts of Liverpool.Footnote 44 Redmond, then known for the BBC1 children's drama Grange Hill, innovatively used Sony's ‘complete “glass to glass” production system’ to produce Brookside at a ‘cost-base the new Channel 4 could afford’.Footnote 45 Each house was fitted with concealed electric cables and cameras, enabling more ‘realistic’ action than possible on a set, and Redmond's adoption of cinema's highly mobile Steadicam further liberated Brookside directors from constraints imposed by the traditional and unwieldy television camera system of dolly and tracks.Footnote 46

Cinematic realism extended to other, more controversial aspects of the show. Whereas Coronation Street had become a cosily nostalgic reflection of the past, Brookside boldly addressed topical social issues from mass unemployment, strikes and deindustrialization to homosexuality, AIDS and the privatization of health care. Its diverse characters included not only trade unionists, but also aspirational yuppies, Channel 4's target audience. The premiere, watched by 7 million on first transmission (2 November 1982), stirred up controversy over bad language. Television's ‘moral watchdog’, Mary Whitehouse, was soon calling for the resignation of chief executive Jeremy Isaacs, but influential Daily Mirror critic Hilary Kingsley was hooked from start.Footnote 47 Brookside did not challenge the viewing figures of Coronation Street, but immediately became Channel 4's most popular programme.Footnote 48

The BBC, having fallen behind ITV in the ratings, decided to produce its own edgy, realist soap along the lines of Brookside. EastEnders, first broadcast on 19 February 1985, surpassed expectations to rapidly become Britain's most popular television programme, reaching an audience of 23 million in February 1986.Footnote 49 It targeted not only women, but also men and younger viewers. Prominent teenage characters experienced credible ‘teenage problems’ from unemployment to abuse and pregnancy.Footnote 50 Whitehouse accused the BBC of corrupting ‘family viewing time’ with gratuitous sex and violence, but the salacious storylines, especially that of sixteen-year-old Michelle Fowler's pregnancy, captivated millions.Footnote 51 Having grown up on a North London council estate, Grange Hill actress Susan Tully brought credibility to the role of Michelle. And in an unusual, perhaps unique, configuration, it was Michelle's grandmother, Lou Beale (Anna Wing), who instigated her home pregnancy test.

First broadcast at 7 p.m. on Tuesday, 17 September 1985, the pregnancy-test episode begins with a cup of tea. Lou, the tough but benevolent matriarch in whom Michelle has confided, advises her to ‘only have one cup’ to keep her from ‘running up and down to the lav’. Lou then explains that she is ‘going up the chemist's’ to ‘buy one of them kits’ because she wants to know if Michelle is pregnant ‘for definite’. Michelle readily accepts Lou's conspiratorial plan, which involves lying to her mother about staying home from school and doing the test later in the day when they will have the place to themselves. When Lou returns from the chemist's, the coast is clear and she hands Michelle the test.

Packaging visibly exchanges hands between Lou and Michelle, but the test itself is not shown; viewers are left to infer that Michelle has successfully performed the test in the privacy of the household lavatory. Whereas Which? described lay users as ‘clumsy’ and home test kits as ‘fiddly’, television typically implied an effortless procedure, off screen and between scenes. The brand, in the case of EastEnders, is not clearly visible, but resembles Predictor. When Michelle emerges, having done the test, she must ‘wait thirty minutes’, an ordeal that ‘calls for [another] cup of tea’. An off-screen clock ticks audibly and ominously, building the tension. Midway through the episode, Michelle emerges from the bathroom for a second time. ‘It's positive’, she announces. The episode, but not the storyline, ends with a cliffhanger as Lou asks, ‘Who did it, Chelle? Who's the father?’

Tabloids and viewers speculated that Michelle would miscarry, possibly in a motorcycle accident, but the titillating question of paternity generated by far the most publicity and discussion.Footnote 52 Jonathan Powell, then head of drama at the BBC, claimed that the ‘human story’ had ‘touched a public nerve’.Footnote 53 A review in The Listener attributed the runaway success of EastEnders to the ‘great drama of Michelle Fowler's schoolgirl pregnancy’.Footnote 54 On Christmas Day 1986, 30 million watched as Michelle's mother learned the identity of the baby's father. The ‘whodunnit’ narrative not only hooked viewers, but also allowed the BBC to fulfil its public-service duty by creating plausible contexts for a health visitor, home tutor and social worker didactically to inform Michelle – and viewers – about the ‘rights and entitlements’ of young, unmarried mothers.Footnote 55 Teachers used the serial to frame classroom discussions, and even Whitehouse approved of Michelle's decision against abortion as a ‘very positive storyline’.Footnote 56 Kingsley lauded EastEnders for ‘teaching Britain's kids more about you-know-what than prissy sex manuals’, even reporting that it had disabused a sixteen-year-old boy of the mistaken belief that pregnancy tests ‘give you abortions’.Footnote 57

Michelle Fowler was at the vanguard of a trend that made pregnancy a controversial staple of 1980s British television well beyond drama. Following the ruling against Victoria Gillick, actress Susan Tully promoted the Family Planning Association (FPA) to minors in BBC2's educational documentary ‘Too young to have a baby?’ (12 March 1986). Anne Diamond became Britain's first visibly pregnant television presenter on ITV's Good Morning Britain (1987).Footnote 58 And Sweden's Neneh Cherry sparked a British debate when she performed her hit single ‘Buffalo stance’ on BBC1's Top of the Pops while seven months pregnant (22 December 1988). Documentaries investigated ‘schoolgirl mums’ and IVF while an impressive range of fiction genres appropriated the home pregnancy test for a variety of ends.Footnote 59

Zenith Productions’ The Dead of Jericho (ITV, 1987), the first television adaptation of an Inspector Morse novel, featured a ‘positive’ Predictor test kit in the medicine cabinet of a distraught Ms Anne Stavely (Gemma Jones).Footnote 60 A close-up of a generic box resembling that of Predictor sets the scene for role-reversing male pregnancy in the ‘Parallel universe’ episode of the cult science fiction sitcom Red Dwarf (BBC2, 1988). In ‘Women's trouble’, one of the first episodes of the long-running sitcom Birds of a Feather (BBC1, 1989), sisters Tracey (Linda Robson) and Sharon (Pauline Quirke) discuss contraception, infertility and STIs in the lavatory while Tracey brushes her teeth and Sharon waits for the result of her Predictor. And in ‘The waiting game’ (Channel 4, 1991), an episode of Guyanese British sitcom Desmond's, a ‘negative’ pregnancy test is passed around like a hot potato until it ends up in the hands of a befuddled Desmond Ambrose (Norman Beaton). All these broadcasts showed packaging or the test result, but not the diagnostic process itself.

Only Peter Bebbington's ‘Positively negative’ (Channel 4, 1990) – a short teleplay in youth editor Stephen Garrett's He-Play/She-Play series to showcase new talent – depicted most of the procedure. Shot in a single day, ‘Positively negative’ is essentially a compressed ‘kitchen sink’ drama about a young Yorkshire couple waiting for the result of a pregnancy test. It opens with a close-up of a First Response box and proceeds to show every step of the process with dynamic close-ups of hands, urine and test kit. Though not apparently intended as didactic, the drama might as well be an instructional video for First Response. Marketed by Tambrands, the US company best known for Tampax, First Response retailed in Britain for £6.95. The test required the user ‘to collect a urine sample’, ‘add it by dropper to a test tube containing powder’, swirl the tube ‘to mix the powder with the urine’, and then to leave it standing ‘for five minutes’ before finally pouring the ‘contents of the test tube’ ‘into a small well covered with a filter paper’. The appearance of a ‘clearly visible’ pink colour indicated a positive result; no colour meant negative.Footnote 61

Though her urine is already collected in a plastic receptacle at the start of the play, Tracey (Victoria O'Keefe) performs every other step of the test on screen as boyfriend Keith (Chris Garner) encourages her to ‘bung it in’, stumbles over technical jargon while reading the instructions and confirms the definitely pink, ‘positive’ result.Footnote 62 An unusually detailed portrayal of pregnancy testing, ‘Positively negative’ captured an elaborate ritual on the verge of extinction. In the early 1990s, televisual and cinematic pregnancy testers overwhelmingly switched to Clearblue, the first brand that viewers could be counted on to recognize.

The first Clearblue close-ups

Launched in June 1985 by Unipath, a subsidiary of the Anglo-Dutch company Unilever, Clearblue was a game changer. Marketing literature boasted that its ‘advanced technology’ made the kit ‘less messy’ and ‘more accurate at an earlier stage’, and gave a ‘clearer result’ in ‘less time’.Footnote 63 The rapid commercial success of Clearblue had as much to do with slick advertising and design as it did with its innovative use of monoclonal antibodies. Beyond technological sophistication, it came in ‘altogether a more attractive package for women – less daunting to use and coupled with advertising designed to give it more feminine appeal’. Market research indicated that the brand name, distinctive fan-shaped logo and blue colour carried a ‘positive meaning’. As with all other home pregnancy tests, Clearblue was marketed to women hoping to conceive, ‘so red for danger would have been quite inappropriate’.Footnote 64

Unilever correctly anticipated that the British market, already valued in 1985 at £3 million, or 600,000 tests a year, would expand as public-sector cutbacks pressured doctors to perform tests only when medically needed. As an article in The Guardian warned, the next time a woman asks her doctor for a pregnancy test, she could be told, ‘I'm sorry, but the National Health Service can't afford to find out if you're pregnant. You'll have to go to the chemist and buy a kit’.Footnote 65 Beyond cuts, Unipath cited the ‘general heightening of health awareness, which means many women are keen to know whether they are pregnant or not as soon as possible so that they can adjust their lifestyle accordingly – another reason for the market to expand’.Footnote 66 As Unipath's marketing director told the Financial Times, ‘It is very important to know as early as possible that you are pregnant so that you can change your lifestyle – for example stop smoking and drinking’.Footnote 67

Clearblue captured 30 per cent of the British market in just three months. It was followed in April 1987 by Clearplan, an ovulation test, and in July 1988 by Clearblue One Step.Footnote 68 Winner of the 1989 British Design Award in Medical Equipment, Clearblue One Step innovatively dispensed with the messy handling of liquid reagents and introduced the now-familiar plastic stick with an absorbent wick at one end and two display windows at the other.Footnote 69 At £8.35, it cost slightly more than First Response.Footnote 70 By then, Unipath had captured half the British market, which had more than doubled to £7 million and was still growing at a rate of 15 per cent every year. Global sales approached £100 million annually.Footnote 71 Billed as ‘the most advanced pregnancy testing kit in the world’, the new product, known as Clearblue Easy in the US, incorporated the use of monoclonal antibodies in a ‘novel format derived from a unique rapid assay technology developed solely by Unipath and protected by patents’.Footnote 72 Advertisements in women's magazines typically portrayed white, middle-class women serenely waiting for the clear blue result in the comfort of their own softly lit bathroom. But the earliest on-screen users were pregnant schoolgirls determined to abort and British Asian women caught between cultures and in difficult relationships.

British Asian cinema took off in the late 1980s with Hanif Kureishi's My Beautiful Laundrette (1985) and Gurinder Chadha's I'm British But … (1989), films both supported by Channel 4. The former, though made for television on a low budget in six weeks, was theatrically released and critically acclaimed. The latter launched Chadha's stellar career. Following Channel 4's lead, the BBC also began to support young British Asian talent. In the early 1990s, the corporation hired Meera Syal, freshly graduated in English and drama from Manchester University, to write the screenplay for a feature-length drama for Screen Two (BBC2, 1985–1994), the successor to Play for Today (1970–1984).Footnote 73 She came up with My Sister Wife.

First broadcast on 23 February 1992, My Sister Wife concerns the conflict between a wealthy Pakistani businessman's two wives: Farah Khan (Syal) and Maryam Shah (Shaheen Khan). At the start of the film, the British-born Farah is modern while the Asian-born Maryam is traditional; by the end, their roles have reversed and Asif Shah, the husband (Paul Bhattacharjee), is dead, accidentally poisoned by Farah's misfired plan to murder her rival. Along the way, sexuality, gender relations and reproductive politics are provocatively dramatized in relation to contraception, pregnancy, miscarriage and sex-selective abortion. A crucial moment in the rivalry between the sister-wives comes when Farah discovers a pack of Clearblue pregnancy tests in Maryam's dresser drawer. In a scene, the mood of which could not be more different from the serenity depicted in women's magazines, the discovery prompts Farah to plot revenge: ‘Kill one baby, start another. So you want to fight dirty, my sister-wife; I haven't even begun’.Footnote 74 Though otherwise unusual in many respects, the sequence linking Farah's downward gaze to a Clearblue close-up (albeit of clearly branded packaging, not the stick itself), followed by a dramatic reaction shot, would soon become standard.

Meanwhile, on Channel 4, Brookside introduced multiple pregnancy tests into a schoolgirl-pregnancy-and-abortion storyline timed to coincide with Christmas, a favourite season for dramatic pregnancy testing. Fifteen-year-old Leanne Powell (Vickie Gates) first chooses the cheaper Boots model, which she uses in the toilet of her friend's house. Hoping for a negative, Leanne purchases several more tests in the next episode. A series of close-ups compares a positive ‘clear blue’ result with the instructions, plugs BPAS and shows Clearblue One Step and Boots packaging (Figure 4). Recognizable logos and legible text convey information as her friend Jacqui Dixon (Alex Fletcher) advises Leanne to go to BPAS. Jacqui didactically explains – as much to young viewers as to Leanne – that the service is confidential and ‘you don't have to be over sixteen to have an abortion’. With help from Jacqui's mother DD (Irene Marot), a devout Catholic who finds the hastily hidden tests under her daughter's bed, Leanne does have the pregnancy terminated shortly after her sixteenth birthday. Not a conclusion, the abortion drives the plot along as Leanne's parents find out about DD's meddling and turn against her.

Figure 4. Screen captures from Channel 4's Brookside, first broadcast 14 December 1992, later rebroadcast on Living.

On 21 January 1993, the day after Leanne's fictional abortion, Bhaji on the Beach opened in cinemas around the country. Directed by Chadha and scripted by Syal, it made history as the first feature film directed by an Asian woman in Britain. Co-produced by Channel 4, the film also brought the Clearblue close-up to the big screen. Syal, who had previously collaborated with Chadha on a short Channel 4 film about arranged marriage, came to her with the basic idea for Bhaji: a group of Asian women from Birmingham go to Blackpool for the day.Footnote 75 In an interview with the British Film Institute's magazine Sight & Sound, Chadha explained that she ‘didn't want the film to be “just a comedy”’. Thus she ‘picked the two most taboo subjects within the Asian community – mixed relationships and separation and divorce – and threw them in as well’.Footnote 76 It is in connection with a mixed relationship, that of the young student Hashida (Sarita Khajuria) and her Afro-Caribbean boyfriend Oliver (Mo Sesay), that pregnancy testing comes in.

As with Farah in My Sister Wife and Leanne on Brookside (who also uses a Boots test kit), Hashida opts for Clearblue. In a similar sequence of shots, the camera cuts from a close-up of the ‘positive’ test result – Hashida’s point of view – to a reaction shot of her troubled, downward gaze; ‘Oh shit’, she exclaims (Figure 5). Though easily mistakable for ‘product placement’ – the controversial form of embedded marketing made famous a decade earlier when Steven Spielberg's E.T. (1982) conspicuously advertised Reese's Pieces – the use of Clearblue up to and including Bhaji was, as far as Syal remembers, ‘simply the props department getting the most easily available over-the-counter product at the time’.Footnote 77 From 1994, however, product placement began to play a role.

Figure 5. Consecutive screen captures from Bhaji on the Beach (Gurinder Chadha, 1993), produced by Channel 4 Films and Umbi films, distributed by Channel 4. The second ‘control’ line in the smaller box is not visible, possibly because a ‘negative’ test result was manipulated on set to give the impression of a ‘positive’ result. See also in Figure 4 (top left).

Embedded marketing

Britain's Independent Television Commission (ITC) prohibited production companies from accepting payment from advertisers, but allowed advertisers to pay an intermediary to supply their brand of a particular prop free of charge to production companies. Ever since the first British placement agency was founded in 1984, Britain's unique ‘free prop supply’ system has acted as a ‘de facto product placement industry’, supplying the non-commercial BBC, the ‘word's largest public service broadcaster’, and its commercial rivals with branded props.Footnote 78 Founded by Graeme Atkinson in 1988, Prop Portfolio, a placement agency based in the Northamptonshire market town of Wellingborough, began working with Unipath in 1994 to ensure that more on-screen pregnancy testers chose Clearblue. Crucially, Unipath was ‘never … concerned with the morality of the scenario [and] as long as the test was seen working and being accurate they were happy’.Footnote 79

Unipath's no-strings-attached policy meant that – in stark contrast to the happily married women portrayed in women's magazines – Clearblue was placed in the most scandalous televisual relationships. Prop Portfolio's first ever placement of Clearblue, on ITV's Emmerdale (1994), a soap set in the Yorkshire Dales, was in the hands of character Rachel Hughes (Glenda McKay), who had been carrying on an affair. Two years later, when Georgia Simpson (Helen Grace) used a pregnancy test as part of Brookside’s boundary-pushing incest storyline, she too chose Clearblue.

Product placement, though more commonly associated with cars, electronics, food, soft drinks and cigarettes, was a particularly effective means of marketing Clearblue in Britain.Footnote 80 The BBC, which still controlled a significant market share, did not broadcast commercials, so viewers would see Clearblue only when it was embedded in a drama or comedy or, less frequently, shown on the news. On the commercial channels, marketing campaigns were prohibitively expensive and heavily regulated. Adverts for ‘sanitary products’, then only recently allowed on television before 8 p.m., were not permitted to show ‘product shots’ of tampons or pads. Nor could they visually demonstrate or describe how such products worked, mention ‘menstruation’ or show ‘anything remotely resembling blood’. Instead of blood, a blue liquid was used. The ITC's position on pregnancy testing was similarly restrictive. Chefaro, having missed out on placement, necessarily adopted an oblique approach when it launched a £1.2 million television ad campaign for Predictor in 1995. As a report in the trade journal Community Pharmacy put it,

Beautifully manicured hands twist the top off a fountain pen, remove the nib, then replace it. They whisk a mascara pen from its holder, then put it neatly back. That's how easy it is to use a pregnancy test, we're told, as a glob of blue splodges down over a pink sponge and a blonde sits gazing wistfully into the mid-distance.Footnote 81

The television commercial echoed Chefaro's 1976 magazine advert in emphasizing ease of use, only substituting lipstick with mascara. But as one critic remarked, the scene was ‘a far cry from what goes on behind the closed doors of most real bathrooms, as women drag themselves out of bed to urinate on a stick at first light and find out whether a late period means what they think it means’. It was also a far cry from the realism provided though product placement. The company, she reported, ‘would have liked to use the word urine’, as it did in print advertising, but ‘simply [was not] allowed to on TV’. Though manufacturers generally agreed that television meant ‘a short-term surge in sales’, the cost was ‘prohibitively high’, and even Chefaro could not afford to ‘screen their ads in the ultra-expensive London region, despite the fact that it accounts for about 35 per cent of national sales’.Footnote 82

Unipath generally preferred to advertise in women's magazines, with posters, and occasionally on the radio. But the company responded to Chefaro's television campaign by launching its own in November 1996.Footnote 83 Where rival Chefaro had coped with ITC constraints by resorting to an extreme close-up of Predictor's pink spongy tip, Unipath invented ‘Molly’, an inoffensive cartoon character who also promoted Unipath's new, faster test in women's magazines. But television commercials remained opaque and product placement continued to play a major role; Prop Portfolio placed Clearblue in dozens of television and film productions every year in the late 1990s and early 2000s, including in a newly flourishing cinematic genre: the British romantic comedy.

From romantic comedy to WombTube

The romantic comedy, a Hollywood staple previously unknown in British cinema, took off in Britain in the 1990s as a result of the combined efforts of screenwriter Richard Curtis, actor Hugh Grant and the independent production company Working Title. Originally made for Film on Four, Channel 4's answer to the BBC's Screen One and Screen Two, Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) established a winning formula for films about middle-class, metropolitan characters. It was set in an enchanted, fairy-tale London, where romance blossomed between American and English lovers.Footnote 84 Curtis and Grant followed the unexpected international box-office success of Four Weddings, their first collaboration with Working Title and the highest-grossing British film up to that point, with Notting Hill (1999), Bridget Jones's Diary (2001), Love Actually (2003) and Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004). American actresses speaking Estuary English and transatlantic relationships boosted the international appeal of British romantic comedies in the ‘Cool Britannia’ years of the Spice Girls, Britpop and The Full Monty (1997).Footnote 85

Not only love and marriage, but also infertility and reproduction motivated plots. Notting Hill ends with a visibly pregnant Anna (Julia Roberts) reclining on a park bench with Will (Hugh Grant), and Maybe Baby (2000), adapted by Ben Elton from his semi-autobiographical Inconceivable (1999), ends with Sam (Hugh Laurie) and Lucy (Joely Richardson) still trying for a baby after a failed IVF cycle. In Sliding Doors (1997), an English ‘concept-comedy’ financed by the American production company Miramax,Footnote 86 Helen (Gwyneth Paltrow) emerges from the toilet with a ‘positive’ pregnancy test in hand. Helen, who experiences a miscarriage in both parallel storylines of the narratively experimental film, chooses Predictor, the brand clearly visible on the packaging she holds up to show her friend and viewers. But most pregnancy testers in British romantic comedies used Clearblue.

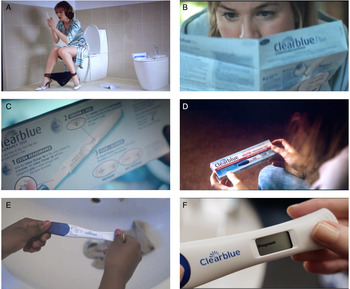

In The One and Only (2002), a box of Clearblue rests on a bidet in the bathroom of an Italian footballer's Newcastle mansion as his English ‘trophy wife’ Stevie (Justine Waddell) counts down the seconds (Figure 6A). When the doorbell interrupts her counting, she rushes downstairs, pregnancy test in mouth, only to be congratulated by the kitchen fitter Neil (Richard Roxburgh). The result is positive and it is love at first sight. Clearblue achieved greater prominence in Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (2004), a film often singled out by critics for its flagrant product placement. Following close-ups of an open box in profile and of the heroine (Renée Zellweger) intently reading instructions, the test is then interposed between Bridget and Mark Darcy (Colin Firth), embodying the potentialities of their future together as they discuss children (Figure 6B).Footnote 87 The result is negative. But twelve years later, when Zellweger and Firth reprised their roles in Bridget Jones's Baby (2016), the result – of a Clearblue Digital – is ‘Pregnant’ (Figure 6 F; Figure 7).

Figure 6. Screen captures from (A) The One and Only (Simon Cellan Jones, 2002), produced by Assassin Films, distributed by Pathé; (B) Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason (Beeban Kidron, 2004), produced by Little Bird, STUDIOCANAL, Working Title; distributed by Universal and Miramax; (C) Puffball (Nicolas Roeg, 2007), produced by Amérique, Dan Films, Grand Pictures, Tall Stories; distributed by Verve; (D) Albatross (Niall MacCormick, 2011), produced by CinemaNX and Isle of Man Film, distributed by Entertainment One; (E) Love Letter (Lucia Yandoli, 2012), courtesy of Lucia Yandoli; (F) Bridget Jones's Baby (Sharon Maguire, 2016), produced by Miramax, Perfect World, STUDIOCANAL, Universal and Working Title; distributed by Universal.

Figure 7. Standard delivery notice (21 September 2015) for Brigit Jones's Baby, listing two Clearblue Digital pregnancy test packs (of two), alongside Belvita breakfast bars, Coca Cola cans and bottles and various other brand-name products. Courtesy of Graeme Atkinson and Scott Shearsmith of Prop Portfolio Ltd.

Beyond romantic comedy, a range of genres appropriated the Clearblue close-up in the early twenty-first century. In Puffball (2007), a supernatural drama based on the Fay Weldon novel from 1980, Liffey (Kelly Reilly), an ambitious young architect, downs a glass of red wine while nervously waiting – stopwatch in one hand and cigarette in the other – for the result of her pregnancy test. The Clearblue logo is conspicuous in close-ups of the ‘positive’ test and instructions on the back of the packaging (Figure 6C). When Oxford-bound Beth (Felicity Jones) has a pregnancy scare in Albatross (2011), a coming-of-age story set in a family-run seaside hotel, streetwise Emilia (Jessica Brown Findlay) fetches her a test from the local pharmacy (Figure 6D). The friends embrace after a Clearblue Digital close-up reveals that Beth is ‘Not Pregnant’. Clearblue is shoplifted in Now Is Good (2012) and used by sixteen-year-old Kerrie (Sandra Enogie) in Lucia Yandoli's Love Letter (2012), an educational film made in collaboration with Highbury Grove School in Islington, North London (Figure 6E).

Beyond cinema and television, the Clearblue close-up has framed portrayals of pregnancy testing in other visual and narrative media. A sponge-tipped test on the cover of Tough Choices: Young Women Talk about Pregnancy (1999) evokes the first-hand accounts compiled within, and the three line-bearing tests pictured in Jools Oliver's Minus Nine to One: The Diary of an Honest Mum (2005) might be those taken ‘for [her] second baby, Daisy’, cherished ‘in a special box and, yes, the lines are still there just like magic!’ The ‘ghostly pale blue lines’ of a home pregnancy test remind a religious character in Zadie Smith's debut novel White Teeth (2000) of ‘the face of the madonna in the zucchini of an Italian housewife’, and on the first page of her fourth novel, NW (2012), the crisis posed by a positive result is conveyed in still fewer words, a literary close-up of sorts: ‘Blue cross on a white stick, clear, definitive. What to do?’Footnote 88

From Josephine Pryde's Embryos and Estate Agents: L'Art de Vivre at the East End's Chisenhale Gallery (2011) to Home Truths: Photography, Motherhood and Identity at the Photographer's Gallery (2013–2014), photographic pregnancy tests now adorn London's leading galleries with some regularity.Footnote 89 Love Is What You Want (2011), the Southbank Centre's Tracey Emin retrospective, displayed the artist's used pregnancy tests, now historical artefacts from a 1999 piece.Footnote 90 London-based artist Gina Glover's Yes! uses rows of pregnancy tests as tally marks to ‘translate the experience of waiting for results during the process of IVF into a stylized, repetitive sentence of images ending in victory’.Footnote 91 And Liv Pennington projected extreme close-ups of pregnancy test results ‘live in real-time’ at performances of Private View (2002–2010) in London, Poitiers, Oslo and Manchester. Comprising ‘forty different women's pregnancy tests from the London performance, combined with text written by the women as they were waiting to take their test’,Footnote 92 the photographic companion piece makes apparent the fingerprint-like uniqueness of each result (Figure 8).Footnote 93

Figure 8. Private View (Liv Pennington, 2006), Digital C type on Aluminium, 80 × 76 cm. Courtesy of Liv Pennington.

Today, the moment of pregnancy testing is an extraordinary event of everyday life that most people will first encounter on screen – not only in cinema and on television, but increasingly also on laptops, tablets and phones. In January 2015, the Daily Mail Online reported that the keyword search for ‘pregnancy test results’ produced more than 18,000 YouTube videos.Footnote 94 Breaking the cultural taboo on disclosing pregnancy before the first routine scan at twelve weeks, ‘WombTubers’ – who freely appropriate the Clearblue close-up – have created a virtual network of support and sympathy for women who experience miscarriage.Footnote 95 But even when pregnancy testing is not filmed for public consumption, cinema and television occasionally provide the frame.Footnote 96 For instance, in her intimate pregnancy memoir, Expecting (2016), Edinburgh journalist Chitra Ramaswamy imagines a ‘camera lens hovering above [her] head’ and allows herself a ‘Hitchcockian moment of suspense’, before finally indulging in the revelatory ‘close-up’ – a moment she compares to a ‘staunchly white’ television advert.Footnote 97 So familiar are the dramatic conventions of the big and small screen that, at least for some women, pregnancy testing can feel a bit like being in a movie.

The flexible politics of the close-up

From the Southbank Centre to WombTube, EastEnders to NW, the appropriation and aestheticization of pregnancy testing apparently knows no bounds. This article has sought to recover how the Clearblue close-up, a surprisingly little-researched cliché, was established and stabilized. Focusing on the intersection of technological, cultural and media change, it has attempted to explain the British explosion of televisual and cinematic pregnancy testing in terms of several conditions of possibility that converged in the late 1980s and early 1990s: the rapid commercial success of Clearblue, itself related to the biotech boom; NHS cutbacks; the rise of health consumerism; the media's dual obsession with teenage mothers and older career women trying to conceive; Channel 4's influence on dramatic television and cinema; ITV's restrictive attitude towards advertising; and Unipath's permissive attitude towards placement.

Free, no-strings-attached placement was especially crucial in Britain, where the non-commercial BBC controlled a large market share. Television and cinema's dramatic close-up and reaction shot, often of a young woman's distraught face, reached larger, younger and more diverse audiences than advertisements in women's magazines ever could. Constitutive of Britain's increasingly public culture of reproduction, this remarkably stable aesthetic convention did much to consolidate Clearblue as a recognizable brand. More than television ad campaigns, which were prohibitively expensive and highly regulated, it was the rise of socially engaged drama and embedded marketing that – prior to Clearblue Digital – helped equate the sight of thin blue lines with pregnancy.Footnote 98 Though often implicating unprotected, underage and otherwise transgressive sex, the innocuous plastic stick also redirected viewers’ attention away from the messier aspects of conception.Footnote 99 Recognizably branded packaging, written instructions and thin blue lines were dramatically charged, coded with meaning and acceptably abstract. The Clearblue close-up ambiguously concealed as much as it revealed. Its visual politics were sufficiently flexible for the aesthetic convention first established in television drama to be appropriated by filmmakers, artists and WombTubers. Abstraction, ambiguity and flexibility were its keys to success.