Household food insecurity (HFI) is broadly described as an ‘uncertainty about future food availability and access, insufficiency in the amount and kind of food required for a healthy lifestyle, or the need to use socially unacceptable ways to acquire food’(Reference Anderson1). HFI is usually determined by a lack of household financial resources and can have a detrimental impact on the health and well-being of all members of a household, including children.

In 2022, the Food Foundation reported that 4 million children in the UK were experiencing HFI(2), and a previously published rapid review of HFI and child health outcomes found that HFI had a detrimental impact on the physical and psychosocial well-being of children and adolescents(Reference Aceves-Martins, Cruickshank and Fraser3). There is also evidence to suggest that the harmful health impact of HFI in childhood may have detrimental health consequences into adolescence and early adulthood(Reference Paquin, Muckle and Bolanis4,Reference Dubois, Bédard and Goulet5) . However, little is known about how HFI leads to or is associated with poor child and adolescent health outcomes.

To the authors’ knowledge, no review has attempted to synthesise the literature on mechanisms to consider HFI’s multiple health impacts and impacts over time. This rapid review aims to fill this evidence gap and additionally provide an updated rapid review of child/adolescent health outcomes associated with HFI, targeting child and adolescent populations in Western high-income countries (HIC), which reflect the UK child/adolescent population.

Aims

The primary aim of this review was to identify and summarise the current literature reporting on the mechanisms by which HFI is associated with child and adolescent health outcomes. The secondary aim of this review was to provide an updated account of the key HFI determinants and the child/adolescent health outcomes associated with HFI. The review was used to inform a conceptual model of HFI and child/adolescent health outcomes to illustrate and consolidate the review findings, for the purposes of highlighting areas for intervention and policy planning.

Methods

Study design

The aims of this review were met using rapid review methods. The fast-growing academic and policy interest in HFI, coupled with the urgency to synthesise good-quality evidence in a timely manner, meant that rapid review methods were preferred over systematic review methods. Rapid reviews use transparent, systematic review search methods to identify and synthesise evidence, while offering flexibility in their methodology. This study design allowed for streamlined search strategies without compromising validity, which aligned with the exploratory and scoping nature of this review(Reference Butler, Deaton and Hodgkinson6). The elements of the systematic review methodology that were adapted for this rapid review were that a grey literature review was not conducted, one reviewer screened and extracted studies and quality assessment was limited to studies reporting on mechanisms only. The lead author was supported by co-authors in shaping the study objectives and search strategy.

Search strategy

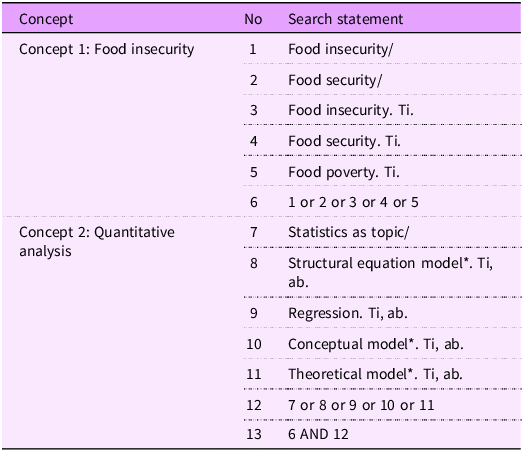

An initial scoping search was performed in PubMed and Google Scholar to identify key publications and retrieve keywords for the search strategy. The search strategy was designed to capture studies that would fulfil both the primary and secondary aims of the review. The search was divided into two concepts: (i) food insecurity/food poverty and (ii) quantitative analysis (encompassing statistical, theoretical and conceptual models relevant to the research problem). An initial scoping search in PubMed found that food insecurity and food poverty were often used interchangeably in studies; thus, both were incorporated as key terms in the search strategy. Searches were conducted in databases: Medline 1946; Web of Science, EMBASE 1947; and the Cochrane Library for articles up to March 2022 (searches were limited to studies published within the past 15 years). Search terms were used as topic headings and Medical Subject Headings and are present in Table 1. Further studies were retrieved using backward and forward citation searching of included articles. The scope of the review was limited to the retrieval of peer-reviewed published literature.

Table 1 Search strategy including search concepts, search terms and their combinations

* The asterisk denotes a truncation symbol used to capture all word variants beginning with the specified root (e.g., model* retrieves “model,” “models,” “modeling,” “modelled”).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

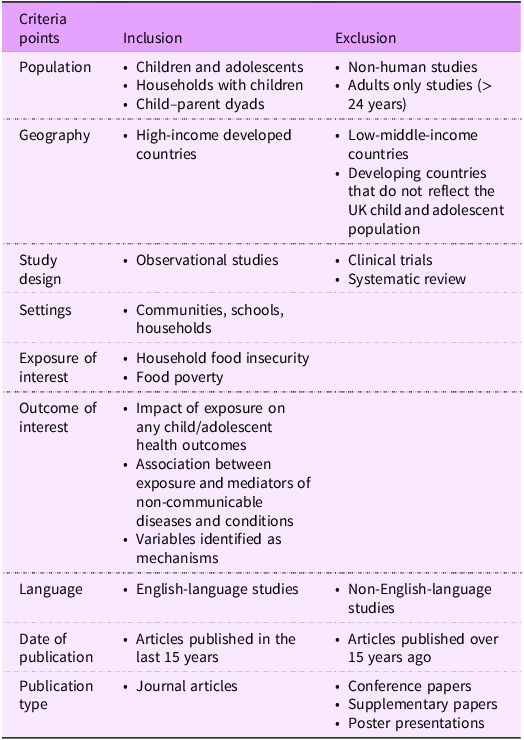

Observational studies were included to reflect the complex relationships between HFI and child/adolescent health outcomes in real-world settings. Studies were included if their population of interest comprised children (aged 3–10 years), adolescents (aged 11–24 years, with a mean age < 19 years) or child/adolescent–parent dyads. The adolescent age range was based on developmental models, which recognised that important aspects of physical, mental and social development continue into early adulthood(Reference Sawyer, Azzopardi and Wickremarathne7). Younger children (aged under 3 years) were not included in the scope of this review. The health impacts of HFI on children can differ by age group, and infants may be more vulnerable to nutrient deficiencies related to HFI, which may contribute to developmental delays in the early years of life(Reference Drennen, Coleman and Ettinger de Cuba8).

Studies from Western English-speaking HIC, including the UK, Ireland, the USA, Canada and Australia, were included. Studies from these countries were included to closely generalise the impact of HFI on child/adolescent health outcomes to the UK child/adolescent population. Studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) were excluded due to differences in food systems, nutritional challenges in child/adolescent populations and social policy(Reference Turner, Kalamatianou and Drewnowski9,Reference Bell, Nguyen and Andreae10) . HFI in LMIC may be associated with infectious diseases, such as malaria, which are uncommon in Western HIC(Reference Pérez-Escamilla, Dessalines and Finnigan11).

Studies were included if the population exposure was defined as HFI or food poverty. The definition of HFI was decided based on the US Department of Agriculture definition of food insecurity: food insecurity is a ‘household-level economic and social condition of limited or uncertain access to adequate food’(12). Only quantitative studies were included, as the review sought to summarise studies that had used statistical methods to confirm relationships between HFI and health outcomes. An advantage of focusing on quantitative studies was that they have utility beyond this review, such as providing insight into parameters for modelling based on the conceptual model. While qualitative studies provide valuable insight into individuals’ lived experiences of HFI, they were excluded as they do not provide the statistical rigour required to identify population-level correlational relationships between HFI, health outcomes and potential mediators.

Studies were selected based on their reporting of child and adolescent health outcomes. Health outcomes were agreed upon by the authors and discussed for discrepancies. Health outcomes were defined as metabolic risk factors (e.g. BMI/cholesterol/fasting glucose levels), health-related conditions (including physical and psychosocial conditions) and biological processes (e.g. sleep). Further details on inclusion/exclusion criteria are presented in Table 2. The lead author of the paper reviewed titles and abstracts to be included in full-text review, and inclusion was determined by the same reviewer with support from co-authors when examining the full text of publications.

Table 2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria used to include studies

Data extraction

The Cochrane data collection form was adapted by removing items that were not relevant for this review, such as experimental designs, for example, duration of participation, number of missing participants and intention-to-treat analysis details(13). Variables extracted included sample size, country, datasets used, participant information (e.g. sociodemographic characteristics), HFI measurement tools, the participant reporting HFI, the health outcome of interest, statistical methods and key study results. Data extraction was completed by the lead author.

Study quality

The Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool analysed the quality of mechanism studies only for risk of bias, as these were the primary studies of this paper(Reference Hayden, van der Windt and Cartwright14). Studies scored low, medium or high risk of bias based on an established set of thresholds within the QUIPS tool.

Results

Description of included studies

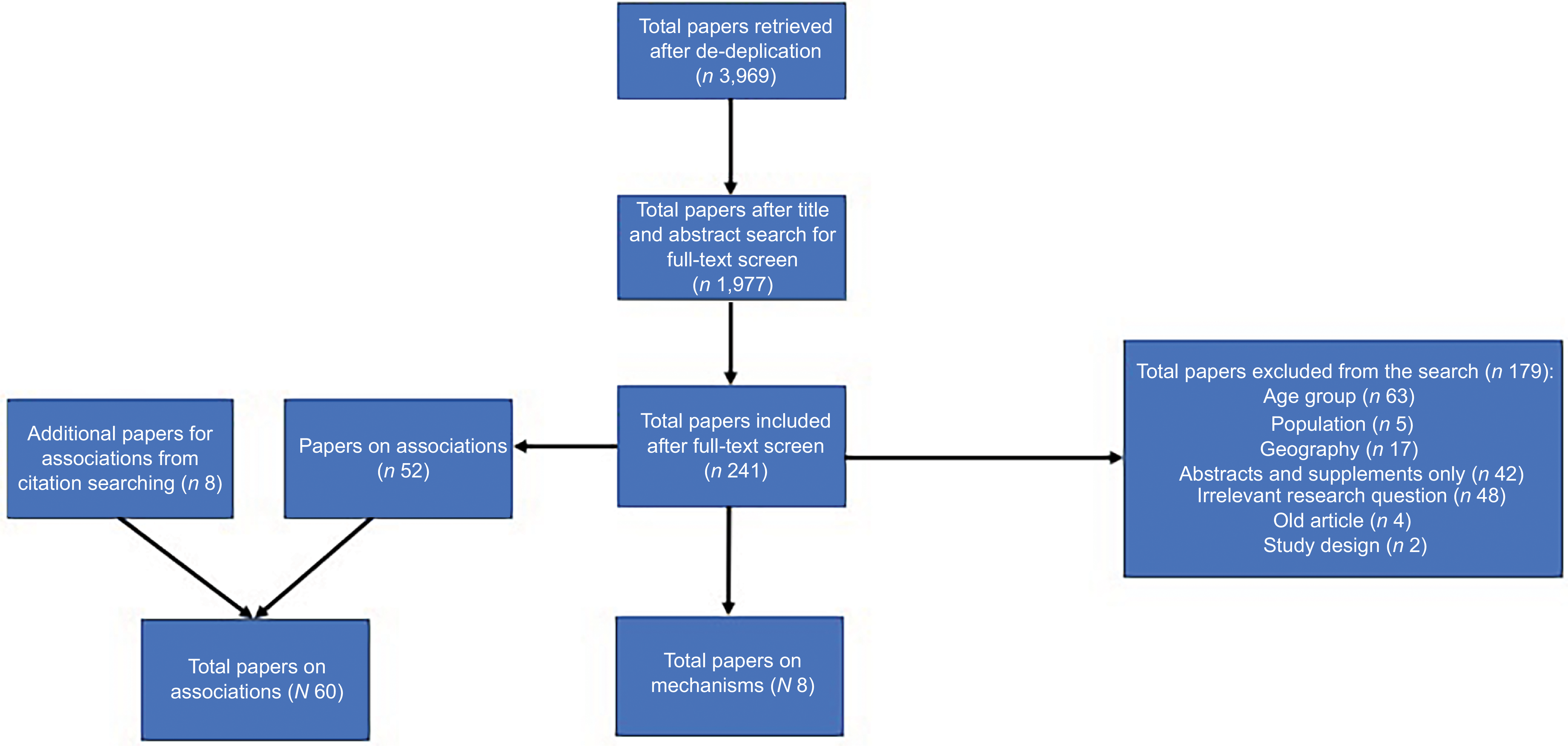

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the search results. After removing duplicates, the search results retrieved n 1977 articles, and their titles and abstracts were screened. A total of n 241 were eligible for full-text screening, of which n 8 were mechanism studies(Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15–Reference Willis and Fitzpatrick22) and n 60 were association studies(Reference Altman, Ritchie and Frongillo23–Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) (n 52 found by the search strategy and an additional n 8 retrieved by citation searching strategy).

Figure 1 Summary of search results for studies assessing the mechanisms by which household food insecurity (HFI) relates to child and adolescent health outcomes and studies assessing the association of HFI and various child and adolescent health outcomes (including appropriate parental outcomes). *Backward and forward citation searching strategy identified additional studies assessing associations of HFI and child and adolescent health outcomes.

Most studies included were of cross-sectional design (n 59), and the remaining were longitudinal (n 10)(Reference Gee and Asim17,Reference Hatem, Lee and Zhao19–Reference Marçal21,Reference Gasser, Mensah and Kerr38,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Eisenmann40,Reference Jackson and Vaughn46,Reference Mangini, Hayward and Zhu57,Reference McIntyre, Williams and Lavorato62,Reference Yang, Sahota and Pickett81,Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) . In terms of geography, n 2 studies were based in Australia(Reference Gasser, Mensah and Kerr38,Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell70) , n 6 from Canada(Reference Godrich, Loewen and Blanchet39,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Marjerrison, Cummings and Glanville58,Reference McIntyre, Williams and Lavorato62,Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar67) , n 1 from the UK, n 1 from Ireland(Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65) and n 59 from the USA. In terms of child age, n 8 studies included the child age group (3–10 years old)(Reference Gee and Asim17,Reference Canter, Roberts and Davis27,Reference Hobbs and King43,Reference Jackson and Testa47,Reference King49,Reference Kral, Chittams and Moore52,Reference Mangini, Hayward and Dong56,Reference Yang, Sahota and Pickett81) , n 29 looked at a mix of child and adolescent populations(Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18,Reference Appelhans, Waring and Schneider24,Reference Drucker, Liese and Sercy28,Reference Dykstra, Davey and Fisher31,Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver32,Reference Gasser, Mensah and Kerr38,Reference Hill42,Reference Kaur, Lamb and Ogden48,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Kuku, Garasky and Gundersen53,Reference Landry, van den Berg and Asigbee54,Reference Mangini, Hayward and Zhu57–Reference Masler, Palakshappa and Skinner60,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell70,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72–Reference Tan, Laraia and Madsen74,Reference To, Frongillo and Gallegos77,Reference Widome, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan79,Reference Wirth, Palakshappa and Brown80,Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) and the rest of the studies (n 34) investigated adolescent populations (11–24 years) only.

Some studies investigated more than one health condition; therefore, there is an overlap in the numbers. Of the total studies included in this review, n 21 investigated weight status, n 3 investigated dental cavities, n 2 investigated asthma, n 4 on diabetes/prediabetes risk, n 5 investigated blood pressure, n 4 investigated cholesterol and other metabolic markers of disease, n 3 investigated sleep, n 3 investigated smoking, drinking and substance abuse, n 19 investigated diet, n 14 investigated mental health and behaviour, n 2 investigated physical activity, n 3 investigated quality of life, n 10 investigated eating behaviours, n 1 investigated anaemia and n 1 investigated bone mass disparities.

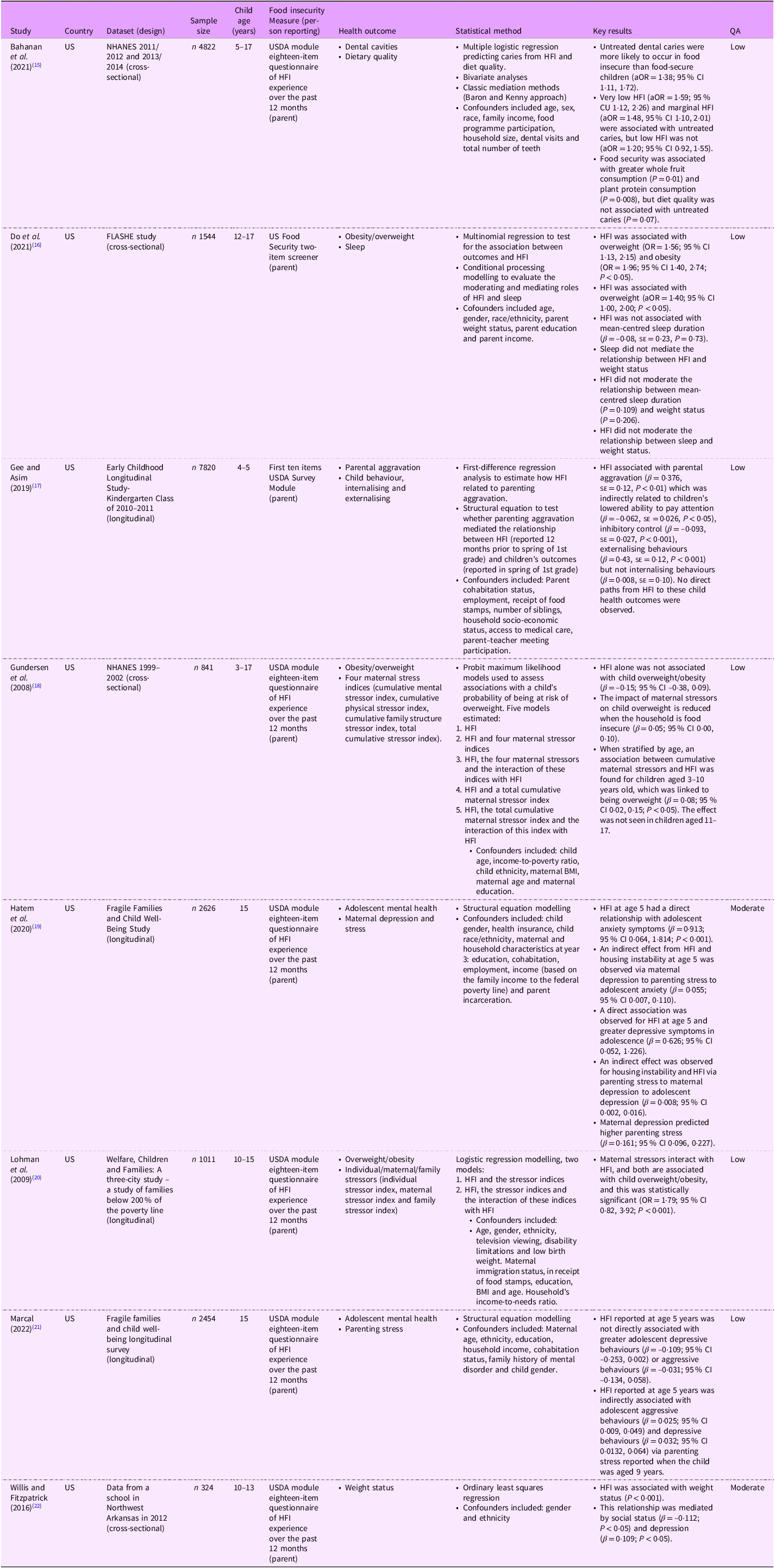

Studies reporting on mechanisms are presented in Table 3, while studies reporting on associations are presented in Table 4. Studies are presented by health outcome below.

Table 3 Included studies that evaluate mechanisms by which HFI may be related to child/adolescent health outcomes

aOR, adjusted OR; HFI, household food insecurity; QA, quality assessment. USDA, US Department of Agriculture.

Table 4 Included studies that evaluate associations between HFI and various child/adolescent health outcomes

Apo B, apo B-100; B, beta; PR, prevalence ratio; RR, relative risk.; RRR, relative risk ratio; SES, socioeconomic status; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages.

Outcomes

Obesity and overweight

Twenty-one studies investigated the relationship between HFI and child overweight/obesity and found mixed results(Reference Do, Bowen and Ksinan16,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18,Reference Lohman, Stewart and Gundersen20,Reference Willis and Fitzpatrick22,Reference Bauer, MacLehose and Loth25,Reference Fleming, Kane and Meneveau34,Reference Fulay, Vercammen and Moran36,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Eisenmann40,Reference Gundersen, Garasky and Lohman41,Reference Holben and Taylor44,Reference Hooper, Telke and Larson45,Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Kuku, Garasky and Gundersen53,Reference Martin and Ferris59,Reference Niemeier and Fitzpatrick66,Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68,Reference Poulsen, Bailey-Davis and Pollak69,Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71,Reference Wirth, Palakshappa and Brown80–Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) . Eight studies found no direct association between HFI and child overweight/obesity using various markers of weight status, including BMI, waist circumference, trunk fat mass, triceps skin folds, body fat percentage, metabolic syndrome, BMI z-scores and weight status(Reference Do, Bowen and Ksinan16,Reference Fulay, Vercammen and Moran36,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Eisenmann40,Reference Gundersen, Garasky and Lohman41,Reference Martin and Ferris59,Reference Niemeier and Fitzpatrick66,Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68,Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71) . Eleven studies found a statistically significant association between HFI and greater odds of overweight/obesity OR range: 1·44–1·81 (95 % CI 1·13, 2·48)(Reference Bauer, MacLehose and Loth25,Reference Fleming, Kane and Meneveau34,Reference Holben and Taylor44,Reference Hooper, Telke and Larson45,Reference Kaur, Lamb and Ogden48,Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Kuku, Garasky and Gundersen53,Reference Poulsen, Bailey-Davis and Pollak69,Reference Wirth, Palakshappa and Brown80–Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) . One study only found an association between greater BMI and HFI in adolescent boys(Reference Bauer, MacLehose and Loth25), while one study found an association in older children and not younger children (< 6 years)(Reference Kaur, Lamb and Ogden48). Two studies in this review did not report a statistically significant association between HFI and overweight. However, they did find a greater prevalence of obesity in food insecure populations(Reference Fleming, Kane and Meneveau34,Reference Hooper, Telke and Larson45) . Only one study found an association between HFI and reduced odds of obesity(Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82).

Studies found that the relationship between HFI and child overweight/obesity was determined by child age, child ethnicity, parental education, household income, maternal BMI and severity and timing of HFI(Reference Bauer, MacLehose and Loth25,Reference Holben and Taylor44,Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Kuku, Garasky and Gundersen53,Reference Niemeier and Fitzpatrick66,Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68,Reference Poulsen, Bailey-Davis and Pollak69,Reference Wirth, Palakshappa and Brown80–Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) . For example, children who were food insecure, older, non-White, whose parents had lower educational attainment level and whose parents were obese were more likely to be overweight. One study found that food insecure girls were more likely to be overweight, compared with food-secure girls, but the same comparison was not drawn for boys(Reference Martin and Ferris59). Furthermore, persistent HFI and timing of HFI were also associated with both weight extremes. Children who experienced persistent HFI throughout their life from early childhood to early adolescence had higher odds of being overweight, while children who experienced a single exposure to HFI in early childhood were associated with underweight in early adolescence(Reference Kuku, Garasky and Gundersen53,Reference Wirth, Palakshappa and Brown80,Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) .

Four studies explored the mechanism by which HFI may be associated with weight status(Reference Do, Bowen and Ksinan16,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18,Reference Lohman, Stewart and Gundersen20,Reference Willis and Fitzpatrick22) . Two studies exploring mechanisms found that an interaction between HFI and maternal stressors had an impact on weight status, for children aged 3–10 years old and adolescents aged 10–15 years old; however, results were mixed(Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18,Reference Lohman, Stewart and Gundersen20) . Both studies did not find a direct association between HFI and child overweight. One study found that an interaction between HFI and maternal stressors amplified the probability of food-secure children being obese or overweight, compared with children living in food insecure households, whose mothers experienced similar stressor levels (P < 0·05)(Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18). In contrast, the second study found that maternal stressors enhanced the likelihood of living with overweight or obesity when an adolescent was exposed to HFI (P < 0·001)(Reference Lohman, Stewart and Gundersen20).

One study found that while HFI was directly associated with adolescent overweight (OR = 1·56; 95 % CI 1·13, 2·15; P < 0·05) and obesity (OR = 1·96; 95 % CI 1·40, 2·74; P < 0·05) an indirect relationship was not mediated by sleep duration (P = 0·23)(Reference Do, Bowen and Ksinan16). Additionally, another study found a direct and indirect relationship between HFI and child overweight, mediated by child psychosocial factors including depression and social status (P < 0·05)(Reference Willis and Fitzpatrick22).

Diet quality

Nineteen studies reported and found an association between HFI and diet quality in both children and adolescents, using various diet quality indicators(Reference Bruening, Lucio and Brennhofer26,Reference Canter, Roberts and Davis27,Reference Duke30–Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver32,Reference Fram, Ritchie and Rosen35,Reference Gasser, Mensah and Kerr38,Reference King49–Reference Kral, Chittams and Moore52,Reference Landry, van den Berg and Asigbee54,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Poulsen, Bailey-Davis and Pollak69,Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72,Reference Tan, Laraia and Madsen74,Reference Widome, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan79,Reference Yang, Sahota and Pickett81) . Six studies found that food insecure children and adolescents were less likely to consume vegetables compared with their food-secure peers(Reference Canter, Roberts and Davis27,Reference Fram, Ritchie and Rosen35,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Landry, van den Berg and Asigbee54,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72) . Three studies found that HFI was associated with reduced consumption of fruit(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72) . Four studies in older children (> 10 years) found no association between HFI and fruit and/or vegetable consumption(Reference Fram, Ritchie and Rosen35,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Poulsen, Bailey-Davis and Pollak69,Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71) . HFI was also associated with reduced healthy and unhealthy food availability in the household(Reference Widome, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan79).

Five studies found that food insecure children and adolescents were less likely to consume dairy products than food-secure children/adolescents(Reference Dykstra, Davey and Fisher31,Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver32,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72) . Studies also found that children and adolescents were likely to consume greater savoury and sweet snacks, sugar-sweetened beverages and fast foods than those who were food-secure(Reference Duke30,Reference Dykstra, Davey and Fisher31,Reference King49,Reference Kral, Chittams and Moore52,Reference Landry, van den Berg and Asigbee54,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72,Reference Yang, Sahota and Pickett81) . Moreover, food insecure children and adolescents were more likely to have higher daily energy intake, with lower energy consumption from protein and wholegrains(Reference Fram, Ritchie and Rosen35,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Landry, van den Berg and Asigbee54,Reference Tan, Laraia and Madsen74,Reference Widome, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan79) . Additionally, two studies found that HFI was associated with a reduced intake of vitamins A, B6, B12, thiamine, Fe, riboflavin, Mg, phosphorus and Zn(Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver32,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50) . The relationship between HFI and diet quality differed by gender, ethnicity and child age(Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver32,Reference Yang, Sahota and Pickett81) .

Eating behaviours

Ten studies found that HFI was associated with poor eating habits in children and adolescents, characterised by reduced frequency of family meals, meal skipping, binge eating and overeating in the absence of hunger(Reference Appelhans, Waring and Schneider24,Reference Bruening, Lucio and Brennhofer26,Reference Duke30,Reference Fulkerson, Kubik and Story37,Reference Hooper, Telke and Larson45,Reference Kral, Chittams and Moore52,Reference Masler, Palakshappa and Skinner60,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71,Reference Widome, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan79) . Maternal binge eating and breakfast skipping were associated with food insecure adolescents mimicking this behaviour(Reference Bruening, Lucio and Brennhofer26). A US study also found that food insecure children enrolled in a national school lunch programme were more likely to skip lunch than those enrolled in the programme(Reference Duke30). Two studies found that HFI was related to weight-control eating behaviour, including fasting, laxative use and increased weight loss attempts in children and adolescents(Reference Hooper, Telke and Larson45,Reference Masler, Palakshappa and Skinner60) .

Dental cavities

Three studies found an association between HFI and dental caries, which varied depending on HFI severity and child age (Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15,Reference Hill42,Reference Jackson and Testa47) . The odds of dental caries were significantly greater (OR = 3·51; 95 % CI 1·71, 7·19; P < 0·05) in children who experienced severe HFI compared with fully food-secure adolescents. Older food insecure children had greater odds of dental caries(Reference Hill42). Children who experienced any HFI across all severities had poorer oral health compared with fully food-secure children(Reference Jackson and Testa47).

One study investigating mechanisms found that HFI was directly associated with untreated dental caries in children and adolescents (OR = 1·38; 95 % CI 1·11, 1·72; P < 0·01). In this study, diet quality was not found to be associated with untreated caries, so the authors did not perform a mediation analysis(Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15). However, HFI was associated with poorer diet quality in this study.

Prediabetes risk

Four studies found evidence demonstrating an association between HFI and increased prediabetes risk(Reference Duke29,Reference Lee, Scharf and Filipp55,Reference Marjerrison, Cummings and Glanville58,Reference Mendoza, Haaland and D’Agostino64) . HFI was associated with greater HbA1c concentrations (> 9 %, which is high risk) in all studies. Studies reported racial disparities between HFI and prediabetes risk, with higher Hispanic and Black children having greater prediabetes risk (P < 0·001) than food insecure children of other races(Reference Lee, Scharf and Filipp55). Another study found higher odds of prediabetes risk among food insecure non-White Hispanic adolescents (adjusted (Reference Mendoza, Haaland and D’Agostino64) OR (aOR) = 2·83; 95 % CI 2·14, 3·73) compared with food insecure adolescents who were of Black race (aOR = 1·88; 95 % CI 1·12, 3·14) and Hispanic adolescents (aOR = 1·84; 95 % CI 1·14, 2·97)(Reference Duke29).

Hospitalisation risk

Two studies found that food insecure children had greater rates of hospitalisation than food-secure(Reference Marjerrison, Cummings and Glanville58). HFI was associated with hospitalisations (aOR = 3·66; 95 % CI 1·54, 8·66)(Reference Marjerrison, Cummings and Glanville58) and emergency department visits (prevalence ratio = 2·95; 95 % CI 1·17, 7·45)(Reference Mendoza, Haaland and D’Agostino64).

Blood pressure

Five studies reported mixed evidence for the association of HFI with blood pressure(Reference Fulay, Vercammen and Moran36,Reference Holben and Taylor44,Reference Lee, Scharf and Filipp55,Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68,Reference South, Palakshappa and Brown73) . Three studies found a small positive association, varying by HFI severity, gender, age, ethnicity and household income(Reference Lee, Scharf and Filipp55,Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68,Reference South, Palakshappa and Brown73) . Two studies found little or no association(Reference Fulay, Vercammen and Moran36,Reference Holben and Taylor44) .

Cholesterol, fasting glucose and other metabolic markers of health

Three studies found no association between HFI and various metabolic markers of health(Reference Fulay, Vercammen and Moran36,Reference Holben and Taylor44,Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68) . One study found a significant difference only for marginally food insecure groups, where the odds of having elevated serum TAG (OR = 1·86 95 %; CI 1·14, 2·82), TAG/HDL-cholesterol (OR = 1·74; 95 % CI 1·11, 2·82) and apo B (OR = 1·98; 95 % CI 1·17, 3·36) were greater than those observed in food-secure groups. In this study, marginally food-secure females had greater odds than males of having low HDL-cholesterol (OR = 2·69; 95 % CI 1·14, 6·37)(Reference Tester, Laraia and Leung75)

Asthma

Two studies found an association between HFI and asthma, which varied by race, household income and timing of HFI(Reference Mangini, Hayward and Dong56,Reference Mangini, Hayward and Zhu57) . Food insecurity was associated with greater odds of asthma in non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics. However, odds were lower in non-Hispanic Black children(Reference Mangini, Hayward and Dong56). One study found that the timing of HFI was an important determinant in the association between HFI and asthma diagnosis(Reference Mangini, Hayward and Zhu57). For example, children who experienced HFI a year before entering kindergarten had 13 % greater odds of an asthma diagnosis in the third grade (OR = 1·13; 95 % CI 1·17, 1·20), while HFI experienced in the year prior to joining third grade was associated with 53 % greater odds of developing asthma in the third grade (95 % CI 1·51, 1·55)(Reference Mangini, Hayward and Zhu57).

Anaemia

One study found a positive association between HFI and anaemia. The odds of iron deficiency anaemia among food insecure adolescents were greater than food-secure adolescents (OR = 2·95; 95 % CI 1·18, 7·37; P = 0·02)(Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver33).

Bone mass disparities

One US study found HFI to be associated with less bone mass, particularly in food insecure male children, who had significantly lower estimated total body (P = 0·05), trunk (P = 0·05), spine (P = 0·2), pelvis (P = 0·05) and left arm (P = 0·02) bone mineral content than food-secure males(Reference Eicher-Miller, Mason and Weaver32). Food insecure males consumed fewer dairy products, thus having lower calcium intake than recommended. HFI was more prevalent in non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American and other ethnic groups.

Physical activity

Two studies found that fully food-secure adolescents were more likely to participate in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity than food insecure adolescents (P < 0·02)(Reference Parker, Widome and Nettleton68,Reference To, Frongillo and Gallegos77) .

Quality of life

Three studies found that food poverty or HFI were significantly associated with lower quality of life(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51) and lower life satisfaction(Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65,Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar67) in children and adolescents aged 10–17 years. Moderate-to-severe HFI was associated with lower health-related quality of life outcomes, particularly psychosocial outcomes (P < 0·05)(Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51).

Sleep

Two studies found a negative association between HFI and sleep (P < 0·001)(Reference King49,Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71) . In both studies, food insecure children and adolescents reported poor sleep quality. One study found that HFI was not associated with mean-centred sleep duration in adolescents(Reference Do, Bowen and Ksinan16).

Smoking, alcohol and substance abuse

HFI was associated with greater odds of cigarette smoking(Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71), alcohol consumption(Reference Robson, Lozano and Papas71), opioid misuse and lifetime use of illicit drug use(Reference McLaughlin, Green and Alegría63,Reference Turner, Demissie and Sliwa78) . The relationship between HFI and smoking, alcohol and substance abuse was dependent on age and ethnicity; for example, one study found that food insecure non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic white children of older age were more likely to partake in substance abuse behaviour(Reference Turner, Demissie and Sliwa78).

Mental health and behaviour

Fourteen studies found an association between HFI and detrimental mental health and behavioural difficulties(Reference Gee and Asim17,Reference Hatem, Lee and Zhao19,Reference Marçal21,Reference Altman, Ritchie and Frongillo23,Reference Godrich, Loewen and Blanchet39,Reference Hobbs and King43,Reference Jackson and Vaughn46,Reference Maynard, Perlman and Kirkpatrick61–Reference McLaughlin, Green and Alegría63,Reference Niemeier and Fitzpatrick66,Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar67,Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell70,Reference Tevie and Shaya76) . Most studies explored the relationship in older children or adolescents, with only two studies(Reference Gee and Asim17,Reference Hobbs and King43) reporting in children under 10 years. Four studies found an association between HFI and anxiety, which was significantly worse in females, older children and adolescents and worsened with HFI severity(Reference Maynard, Perlman and Kirkpatrick61,Reference McLaughlin, Green and Alegría63,Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar67,Reference Tevie and Shaya76) . Reports of anxiety were greater in children and adolescents who were not shielded from HFI by caregivers(Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar67). Four studies found an association between HFI and increased depression/atypical emotional symptoms(Reference McIntyre, Williams and Lavorato62,Reference McLaughlin, Green and Alegría63,Reference Ovenell, Azevedo Da Silva and Elgar67,Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell70) . Furthermore, hunger was associated with greater odds of depression and suicidal ideation in adolescents (OR = 2·3; 95 % CI 1·2, 4·3)(Reference McIntyre, Williams and Lavorato62).

Four studies found a positive association between HFI and misconduct, behavioural difficulties and internalising and externalising symptoms in children and adolescents(Reference Hobbs and King43,Reference Jackson and Vaughn46,Reference McLaughlin, Green and Alegría63,Reference Ramsey, Giskes and Turrell70) . Persistent HFI was associated with greater misconduct in adolescents (bullying/fighting/stealing/cheating/lying/misbehaving), and this was worse in food insecure males than females compared with their food-secure counterparts(Reference Jackson and Vaughn46). Additionally, three studies found that HFI was associated with poor self-esteem in older children and adolescents, and this was stronger in girls than in boys (Reference Altman, Ritchie and Frongillo23,Reference Godrich, Loewen and Blanchet39,Reference Niemeier and Fitzpatrick66) . One study found a positive association between HFI and body dissatisfaction in US adolescents across all races and BMI categories, which was stronger among those with African American race/ethnicity (P < 0·001)(Reference Altman, Ritchie and Frongillo23).

Three studies explored mediatory pathways between HFI and child/adolescent mental health and behavioural outcomes. One study found that HFI, reported by the parent in early childhood (aged 5 years), was directly associated with adolescent anxiety and depressive symptoms. The study found that both HFI and housing instability combined had an indirect impact on adolescent anxiety and depression via parenting stress and maternal depression, reported when the child was aged 9 years(Reference Hatem, Lee and Zhao19). A second study found that HFI, at age 5, was not directly associated with adolescent aggressive or depressive behaviour; however, it did have an indirect impact on aggressive behaviour and depressive behaviour via parenting stress reported when the child was aged 9 years(Reference Marçal21). A third study found that HFI was indirectly associated with lowered ability to pay attention, lower inhibitory control and greater externalising behaviours via parental aggravation in children aged 4–5 years(Reference Gee and Asim17).

Quality assessment of mechanism studies

Eight mechanism studies, all using data from the USA, in children and adolescents aged 3–17 years, were assessed by the QUIPS tool(Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15–Reference Gee and Asim17,Reference Hatem, Lee and Zhao19–Reference Willis and Fitzpatrick22) . Low risk of bias was found in seven(Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15,Reference Do, Bowen and Ksinan16,Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18,Reference Lohman, Stewart and Gundersen20,Reference Marçal21) out of eight studies, while moderate bias was found in one(12). Quality assessments are located in the online supplementary material, Supplemental material.

Conceptual model of results

This review shows that the evidence relating HFI to health outcomes remains mixed. HFI has detrimental health impacts on child health outcomes for prediabetes risk, dental cavities, bone mass, asthma, anaemia, physical activity, quality of life, behaviour, diet quality and mental health. However, it is unclear whether or how HFI is related to child overweight/obesity, blood pressure and cholesterol/other biomarkers.

The associations and mechanisms found in this review are illustrated in Fig. 2. The green arrows represent an OR > 1, while the red arrows represent an OR < 1. Dashed lines represent mixed evidence.

Figure 2 Conceptual framework of review results of mechanisms and associations reported between household food insecurity (HFI) and child/adolescent health outcomes and parental mental health outcomes. Red arrows indicate OR > 1 between HFI and outcomes, green arrows indicate OR > 1 between HFI and outcomes and a thick dashed line indicates mixed evidence regarding an association between HFI and outcomes or between outcomes.

Discussion

This review identified two key mechanistic pathways between HFI and detrimental child/adolescent health outcomes: (i) diet and (ii) mental health, which appeared to be interrelated in complex ways. There was a strength of evidence supporting the role of parent mental health as a mediator between HFI and greater child/adolescent mental health symptoms and behavioural difficulties(Reference Gee and Asim17,Reference Hatem, Lee and Zhao19,Reference Marçal21) . One explanation of this mechanism may be that HFI contributes to poor caregiver mental health, which results in parents’ reduced abilities to partake in positive parenting practices and provide parental warmth(Reference Huang, Oshima and Kim83). This mechanism of action aligns with the Family Stress Model, which suggests that financial strain leads to economic pressures (e.g. HFI), which can contribute to caregiver psychological distress and compromised parenting practices that impact child outcomes(Reference Masarik and Conger84).

This review found mixed evidence for an association between HFI and child weight status, depending on a range of factors, including timing, severity of HFI and sociodemographic factors(Reference Bauer, MacLehose and Loth25,Reference Holben and Taylor44,Reference Kirk, Kuhle and McIsaac51,Reference Poulsen, Bailey-Davis and Pollak69,Reference Yang, Sahota and Pickett81,Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) . While one study found that maternal stressors enhanced the association between HFI and child overweight, another found that the association was enhanced for food-secure children(Reference Gundersen, Lohman and Garasky18,Reference Lohman, Stewart and Gundersen20) . Although no association between HFI and overweight was concluded, there is evidence of higher obesity prevalence among food insecure populations(Reference Fleming, Kane and Meneveau34,Reference Hooper, Telke and Larson45) . These findings are echoed in the literature, which has described this as the food insecurity–obesity paradox, which has been explained by a multitude of factors, including that individuals may eat more when food is in abundance and reduce their intake when food availability is reduced(Reference Dinour, Bergen and Yeh85). In this review, food insecure children were more likely to consume unhealthy snacks and fast foods(Reference Dykstra, Davey and Fisher31,Reference Kral, Chittams and Moore52,Reference Molcho, Gabhainn and Kelly65) . Unhealthy foods are often cheaper than healthier options, which may contribute to higher obesity rates in food insecure populations who lack the resources to access nutritious food or rely on food banks(Reference Dinour, Bergen and Yeh85,Reference Oldroyd, Eskandari and Pratt86) . However, food bank items may not be adequately nutritionally balanced, which can negatively affect child diet quality and influence child weight status(Reference Fallaize, Newlove and White87).

Evidence of the association between HFI and fruit and vegetable consumption was mixed(Reference Fram, Ritchie and Rosen35,Reference Kirkpatrick and Tarasuk50,Reference Soldavini and Ammerman72) , possibly due to caregiver shielding or intra-household HFI, where caregivers may forgo their nutritional needs for their children(Reference Hanson and Connor88). HFI was associated with reduced family meal participation and meal skipping, possibly due to low availability of food and increased caregiver stress, making preparing family meals more difficult(Reference Appelhans, Waring and Schneider24,Reference Widome, Neumark-Sztainer and Hannan79,Reference Berge, Fertig and Trofholz89) . An evidence gap identified in this review in terms of mechanisms was that no study at the time this review was conducted attempted to investigate the role of diet quality, child mental health or child eating behaviours or parent feeding styles as mediators between HFI and child weight status. A study in UK adults found that HFI was indirectly associated with higher BMI, via distress and eating to cope(Reference Keenan, Christiansen and Hardman90). A similar study approach may be applied to children and adolescents using diet quality, parent feeding styles or child eating behaviours as mediators.

While HFI was associated with untreated dental caries, it was not associated with diet quality, where diet quality was ruled out as a mediator of this relationship(Reference Bahanan, Singhal and Zhao15). Other non-dietary mediators that could explain this relationship may be barriers to accessing oral healthcare products (e.g. toothbrushing)(Reference Weigel and Armijos91). Parental stress experienced during food insecurity may influence caregivers’ ability to encourage dental care. Furthermore, the authors may not have observed an association between diet quality and HFI due to the study’s cross-sectional design, which could not determine causality between HFI, diet and dental health. A more insightful approach would be to analyse longitudinal data on HFI and health outcomes, as this review has established that timing, duration and severity of HFI exposure may have a differential impact on these correlational relationships(Reference Mangini, Hayward and Dong56,Reference Zhu, Mangini and Hayward82) .

Limitations

A limitation of this review was the rapid review study design, which relied on a single reviewer to screen studies. This design may have introduced study selection bias and/or failed to capture all relevant literature and outcomes to fulfil the study aims(Reference Butler, Deaton and Hodgkinson6,Reference Grant and Booth92) . There was a lack of consistency in the measures used to report HFI, with some studies using a validated tool and others using one or two questions within a survey. A recent scoping review commissioned by the Food Standards Agency highlighted the diversity between HFI tools used to measure HFI in the UK, emphasising a need for research groups, governmental departments and third parties investigating food insecurity to report and recognise the strengths and limitations of the methods used and acknowledge discrepancies between different measures(Reference Lambie-Mumford, Loopstra and Okell93). Most studies included in this review relied on parent-reported HFI, and incorporating child-reported HFI may provide valuable insights into children’s own experience of HFI, especially in adolescents who may have a greater awareness of HFI and more autonomy over their food environment. Using child-reported measures could offer a more accurate perspective of HFI for developing interventions tailored to the needs of child/adolescent populations(Reference Landry, van den Berg and Asigbee54,Reference Bernard, Hammarlund and Bouquet94) .

It was not appropriate to conduct a meta-analysis due to the heterogeneity between outcomes measured, population selected, study comparators and the varied instruments used to measure HFI across included studies. Additionally, a meta-analysis approach would be overly simplistic to capture the complex systems that impact the relationships between HFI and child/adolescent health outcomes(Reference Rutter, Savona and Glonti95). In this study, statistical significance was used as a practical tool to conceptualise HFI and its associated health outcomes. While this approach may be considered controversial in light of emerging literature suggesting that over-reliance on statistical significance can lead to incorrect conclusions, effect sizes were also reported to provide a more nuanced understanding of the correlational relationships between HFI and child/adolescent health(Reference Grant and Hood96). This dual approach ensured a balanced interpretation of mechanisms and associations while offering a foundation for further exploration of these complex relationships.

Implications of this review

The review identified a gap in the literature for UK-based studies and highlighted that further research using quantitative methods and longitudinal data may be beneficial for gaining more insight into the mechanisms by which HFI is associated with the plethora of outcomes identified in this review. Due to the inclusion criteria, qualitative evidence and studies of LMIC were excluded. This review can be used to inform future research priorities, such as a qualitative review, which could add depth and accounts of individual experiences of HFI to supplement the findings of this review. Additionally, a review exploring HFI and child/adolescent outcomes and mediators in LMIC could be conducted to compare findings.

The conceptual map provides a guide for policymakers to identify where interventions may be beneficial in ameliorating the health impact of HFI in children and adolescents in Western HIC. The study scope was limited to children and adolescents in Western HIC, physical and mental health outcomes and biological processes (e.g. sleep) to reduce the impact of heterogeneity and improve the validity of the results. Given the complexity of the problem of HFI, the findings may not be appropriate for supporting interventions and policies in other settings (e.g. LMIC), for younger child age groups (e.g. infants < 3 years) and for health outcomes that are not explicitly summarised in this review. Policymakers should be aware of these limitations when using this review as evidence for intervention development. However, the results from this review can help guide further research in other settings and child populations.

Conclusions

The present rapid review identified that HFI is related to detrimental child physical and psychosocial health outcomes via (i) diet and (ii) mental health pathways. Maternal mental health and parent stress were identified as mediators explaining the relationship between HFI and child/adolescent behaviour and mental health. A paucity of longitudinal studies and studies of UK child populations highlights evidence gaps and priorities for further research. Sociodemographic factors such as ethnicity and household income were identified as key determinants of HFI, and policymakers should take these into account when planning interventions aiming to improve health in food insecure child populations. Additionally, supplementation of this quantitative review with qualitative evidence will provide a complete picture of this research problem.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980025101092.

Acknowledgements

None

Authorship

S.A. conceived the review and this manuscript draft. P.B. and H.L-M. assisted in the guidance of the review and the manuscript draft. A.S. assisted in the development of the search strategy.

Financial support

This research was supported by a University of Sheffield studentship and Wellcome Trust. This research was funded in whole, or in part, by the Wellcome Trust. For the purpose of Open Access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.’

Competing interests

All authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Ethics of human subject participation

N/A