Memory is an important cognitive function that has been divided into two categories according to the emotional processing pathway: emotional and non-emotional memory. The characteristic of emotional memory is the effects of emotional arousal and valence on information storage and retrieval. Reference Talmi, Lohnas and Daw1 This type of memory has often been investigated through emotional stimulus materials (e.g. faces). Reference Pine, Lissek, Klein, Mannuzza, Moulton and Guardino2 Non-emotional memory is involved in basic intellectual and developmental learning functions, Reference Giofrè, Stoppa, Ferioli, Pezzuti and Cornoldi3 frequently measured by performance on digit memory tasks. Reference Gong, Zheng, Chen, Ge, Lv and Zhang4 The deficits of both types of memory have been found not only to affect the treatment outcomes of general mental health abnormalities, Reference Dong, Zhao, Ong and Harvey5 but are also associated with suicidal tendencies and long-term problems in psychosocial functioning. Reference Cambridge, Knight, Mills and Baune6 Thus, studying the risk factors of these two types of memory could help in enhanced understanding of cognitive and emotional processes.

The emotional and non-emotional memory deficits relevant to mental problems are evidenced as being associated with a number of cognitive factors, mainly dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and mind-wandering. Reference Blondé, Sperduti, Makowski and Piolino7,Reference Williams8 The concepts of these cognitive factors derive from the cognitive model of psychopathologising, with dysfunctional attitudes proposed by Beck 50 years ago Reference Beck9 and new concepts subsequently incorporated, including rumination Reference Nolen-Hoeksema10 and mind-wandering. Reference Randall, Oswald and Beier11 Some hypotheses have suggested that both emotional and non-emotional memory deficits may be associated with dysfunctional cognitive development. Reference Disner, Beevers, Haigh and Beck12,Reference Roiser and Sahakian13 In recent years, it has been suggested that cognitive resources are diminished due to these cognitive factors Reference Randall, Oswald and Beier11,Reference Beck14,Reference Levens, Muhtadie and Gotlib15 and allocated less to target memory content, and thus contribute to the emotional and non-emotional memory deficits pertaining to psychopathology. Reference Randall, Oswald and Beier11,Reference Whitmer and Gotlib16,Reference Spinhoven, Bockting, Kremers, Schene, Mark and Williams17

Cognitive factors and memory

Several empirical studies have explored the mechanisms underlying the relationships between dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and mind-wandering with emotional and non-emotional memory. Reference Blondé, Sperduti, Makowski and Piolino7,Reference Williams8 Dysfunctional attitudes are negative, stubborn, cognitive schemas that can be activated by adverse environmental events. Reference Beck9 Research on emotional autobiographical memory has found that emotional stimuli can activate dysfunctional attitudes, leading to a focus on negative mental schemas and self-knowledge, thus reducing the resources allocated to memorisation of details. Reference Spinhoven, Bockting, Kremers, Schene, Mark and Williams17 There is also the hypothesis that cognitive avoidance of details is used to mitigate the emotional impact of negative stimuli, with the contribution of negative thoughts. Reference Köhler, Carvalho, Alves, McIntyre, Hyphantis and Cammarota18 Mind-wandering is another cognitive factor defined as a spontaneous shift in thinking content away from ongoing events. Reference Smallwood and Schooler19 The role of mind-wandering in non-emotional working memory deficit has been a focal point, and has been suggested as causing difficulties in updating memory content and ‘blocking out’ irrelevant information, by diverting attention. Reference Kam and Handy20 Rumination is a passive response pattern to distress. Reference Nolen-Hoeksema10 It belongs to both the negative thoughts that can be induced by dysfunctional attitudes and the spontaneous, repetitive thinking that is limited to the negative content of mind-wandering. Reference van Vugt and van der Velde21 Rumination has been demonstrated to be associated with a variety of both emotional and non-emotional memories. Reference Whitmer and Gotlib16 It may allow for immersion in emotions or avoidant thinking of specific cognition having being attracted to a negative stimulus, thus reducing attention to other details of the emotional memory Reference Williams8,Reference Kornacka, Skorupski and Krejtz22 while occupying cognitive resources of the target non-emotional memory through negative, repetitive thinking. Reference Whitmer and Gotlib16

Existing research has found relationships only between dysfunctional attitude and rumination with emotional memory, and between rumination and mind-wandering with non-emotional memory. Moreover, previous studies on cognitive factors and memory deficits have primarily focused on the impact of a single factor on memory, and only the association with either emotional or non-emotional memory. Further research comparing different factors and memory types could help in understanding the negative relationships of cognitive factors with emotional and non-emotional memories. It may also provide valuable insights into the treatment of cognition and memory problems pertaining to psychopathology.

Aims and hypotheses

We aimed, therefore, to explore the relationships of these common cognitive factors (i.e. dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and mind-wandering) with emotional and non-emotional memory, respectively, in non-clinical participants. Informed by prior research, we asked the following questions: (a) Are negative thoughts (dysfunctional attitude and rumination) the cognitive factors that are strongly associated with emotional memory? (b) Is spontaneous thinking (mind-wandering and rumination) the cognitive factor significantly correlated with non-emotional memory?

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from Central South University (Hunan Province, China) through selective inclusion criteria, as follows: (a) undergraduate college students aged between 18 and 25 years; (b) without a history of psychiatric disorders or significant physical illnesses; and (c) with consent to participate in our study. The sample size was calculated by linear multiple regression: fixed model, R 2 increase in a priori power analysis using G*Power version 3.1.9.7 software for Windows (Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany; https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/gpower). With 0.05 as the level of significance, a statistical power of 0.8 and 3 predictors, the effect size was set at 0.15 in reference to previous research, Reference Cécillon, Mermillod, Leys, Bastin, Lachaux and Shankland23 resulting in a sample size of n = 77. However, a sample size of about 100 is required according to recent studies of cognitive factors and memory. Reference Cécillon, Mermillod, Leys, Bastin, Lachaux and Shankland23,Reference Poulos, Zamani, Pillemer, Leichtman, Christoff and Mills24 Accordingly, a total of 123 participants completed a questionnaire. They were also invited to perform two tasks, task 1 (Yes–no emotional face memory recognition task, n = 111 completed) and task 2 (Yes–no digit memory recognition task, n = 110 completed).

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects/patients were approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (approval no. 2022-020). All participants were informed of the academic study purposes, uses, benefits and risks, and were provided with the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Each participant received 25 Chinese yuan (US$7.65) for participating in one task.

Design

In this cross-sectional study, eligible participants were invited to fill out a set of questionnaires and complete two tasks (Yes–no emotional face memory recognition task and Yes–no digit memory recognition task; Supplementary Fig. 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10930). Participants finished the online questionnaire through the Wenjuanxing online survey tool (Changsha Ranxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Changsha, China; https://www.wjx.cn) before the tasks started on the same day. The questionnaire included demographic information, the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), the Rumination Responses Scale (RRS), the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Form A (DAS-A) and the Mind-Wandering Frequency Scale (MWQ-F). After all 123 participants had completed the questionnaire, they were invited to complete two behavioural tasks – task1 (Yes– no emotional face memory recognition task) and task 2 (Yes–no digit memory recognition task), programmed successfully by E-Prime version 2.0 for Windows (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, Sharpsburg, Pennsylvania, USA; https://pstnet.com/products/e-prime/). In total, 111 students participated in task 1, 110 in task 2 and 98 participants completed both tasks. The percentage of correct reactions and reaction time in both tasks were calculated as task performance metrics. To examine the relationships between dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and mind-wandering and emotional and non-emotional memory, we derived values for dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and mind-wandering from scale scores, and obtained representative values for emotional and non-emotional memory from task performance metrics in tasks 1 and 2 for data analysis. All procedures were carried out in the Psychological Behaviour Laboratory of Central South University.

Measures

Demographic information

Participants’ demographic information, including age, gender (male/female), undergraduate major (science and engineering/other subjects) and grade (freshman/sophomore/junior/senior), were recorded.

Depression

Recent depressive symptoms experienced over the past week were measured by CES-D. Reference Radloff25 This self-report scale consists of 20 items, each scored from 0 (less than one day) to 4 (nearly every day for 2 weeks). Higher scores represent more severe depressive symptoms. The Chinese version has proven reliable and valid, Reference Jiang, Wang, Zhang, Li, Wu and Li26 with a reliability of 0.921 in this study. The reason for using the CES-D scale is that it has been widely applied for sample recruitment in the general population, meeting the criteria of this study.

Rumination

The Chinese version of RRS was used in this study; this scale has been developed by Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow. Reference Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow27 Previous Chinese studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the scale. Reference Kong, He, Auerbach, McWhinnie and Xiao28 Twenty-two items in this scale assess rumination from three dimensions: brooding, reflective pondering and symptom rumination. The score of each item ranges from 1 (never) to 4 (very often). Higher total scores on the scale indicate more severe rumination symptoms. The reliability of the RRS scale was 0.922 in this study.

Dysfunctional attitude

The Chinese version of DAS-A was utilised in this study to investigate participants’ activated negative cognitive schema. Reference Wang, Lu, Gao, Wei, Duan and Hu29 DAS-A has high reliability and validity in the Chinese general population. Reference Wong, Chan and Lau30 A total of 40 items were presented in a 7-point Likert-type response format. The scale consisted of eight factors: vulnerability, attraction and repulsion, perfectionism, compulsion, seeking applause, dependence, self-determination attitude and cognition philosophy. Higher scores indicate greater dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes. The scale had a reliability of 0.834 in the present sample.

Mind-wandering

We also measured the mind-wandering frequency of participants in their daily life, via MWQ-F. This scale assesses mind-wandering frequency from three aspects: spontaneous thinking, overall evaluation and loss of attention. It includes 21 items plus a lie test item, with each rated from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). The reliability and validity of this scale were demonstrated in a sample of Chinese students. Reference He, Li, Chen, Wei, Shi and Wu31 The internal consistency reliability of the scale in our current study was 0.964.

Experimental procedure

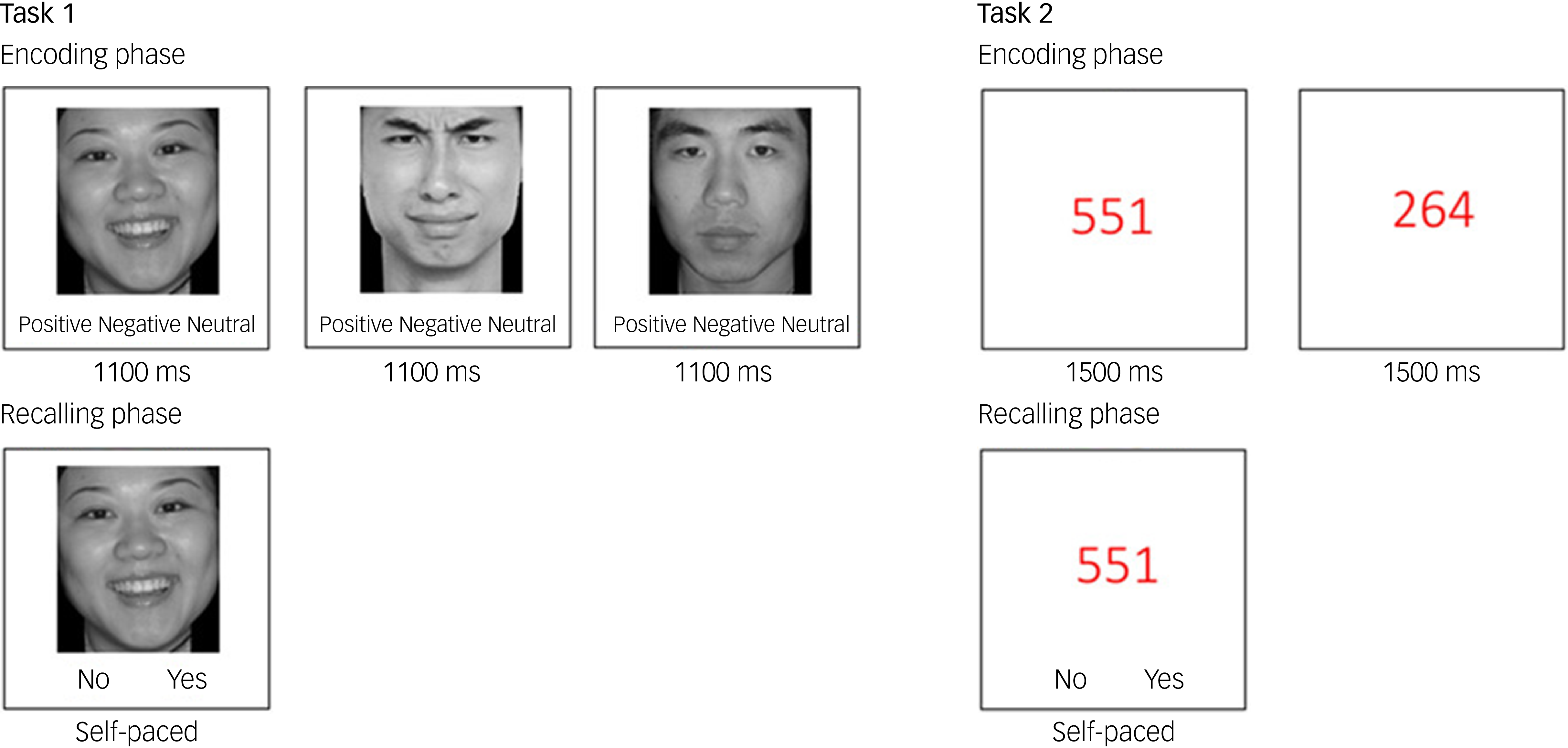

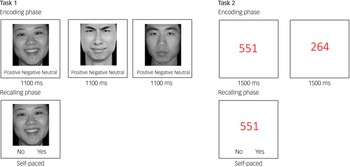

Task 1

This task was adapted from a previous emotional faces task, consisting of two main components – encoding and recognition for face memory Reference Pine, Lissek, Klein, Mannuzza, Moulton and Guardino2 – to assess emotional face memory recognition performance. The face images used in the task were selected from the Chinese Facial Affective Picture System, Reference Xu, Huang, Yan and Luo32 with selection based on the valence and arousal accuracy scale. The task comprised two parts: (a) memory-encoding information, employing positive, negative and neutral faces and (b) memory recognition information, using a mixture of old and new faces. The mean arousal levels for neutral, negative and positive faces were 4.26, 6.43 and 5.08, respectively. Negative faces in this task consisted of equal numbers of sad, fearful, surprised, angry and disgusted faces. The reaction times (memory reaction time) and percentage of correct reactions (memory accuracy) of every type of emotional face memory were calculated and recorded.

Initially the desktop computer screen displayed instructions. Also, a ‘+’ symbol was displayed at the centre of the screen for 500 ms before each image appeared. In the first part, participants viewed 90 faces (30 negative, 30 positive 30 neutral) shown in a pseudo-random order, each being presented for 1500 ms. Participants were instructed to identify the emotional types of the faces and to remember the faces on display. Participants were then asked to run the second part immediately following the first. In this part they were presented with 225 faces, categorised into negative, positive and neutral – each category containing 75 faces. Among those 75 faces in each category, 30 had previously been shown in the first part and 45 were new faces that had never previously been displayed. Participants pressed ‘f’ if they had seen the face in the first task and ‘j’ if not. All stimuli were presented only once, at a self-paced speed.

Task 2

The Yes–no digit memory recognition task was developed based on Gong et al. Reference Gong, Zheng, Chen, Ge, Lv and Zhang4 The process of this task was similar to that of the face memory task (task 1), and was divided into two phases: memory encoding and memory recognition. Digit memory capacity performance was assessed using three-digit numbers, a non-emotional material. Memory reaction times and memory accuracies of the digital memory were recorded.

Similar to task 1, the desktop computer screen initially displayed instructions, with the ‘+’ symbol appearing for 500 ms at the centre of the screen before each image appeared. In task 2, participants were then instructed to memorise 21 three-digit numbers displayed continuously in a pseudo-random order, each for 1500 ms. Following this memory-encoding phase, participants were required to identify the 21 numbers that they had seen previously and were asked to distinguish these from 21 new numbers. Participants were instructed to press the ‘f’ key if they had seen the face in the first task and the ‘j’ key if not. Each stimulus was presented only once, and was self-paced.

Tasks 1 and 2 were programmed by E-prime 2.0; the experimental design can be found in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 The paradigm of task 1 (Yes–no emotional face memory recognition task) and task 2 (Yes–no digit memory recognition task).

Before the task commenced, the desktop computer screen presented instructions. In addition, before each image was shown, a ‘+’ symbol was displayed at the centre of the screen for 500 ms. Each image was presented for 1500 ms, followed by self-paced re-recognition.

Data analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0, with the significance level set at 0.05, two-tailed. Data were first assessed for normality through histograms. Separate and joint descriptive information for both tasks was analysed for continuous variables (mean, standard deviation) and categorical variables (frequency, percentage). Because a small number of participants were involved in only one of the tasks, the chi-square test and analysis of variance were employed to establish that there was no difference in demographics between groups of participants in task 1, task 2 and both. Pearson correlation coefficients explored the associations between aimed cognitive factors (i.e. dysfunctional attitudes, rumination, mind-wandering and depression) and memory performance (memory reaction time and accuracy). Hierarchical linear regressions were conducted to estimate whether the variables that exhibited significance in correlation analyses could significantly predict the memory performance accuracy of emotional faces in task 1 and numbers in task 2. Demographic factors, including age, grade and gender, as potential factors of emotional and non-emotional memory in previous studies, Reference Gong, Zheng, Chen, Ge, Lv and Zhang4,Reference Harvey, Bodnar, Sergerie, Armony and Lepage33 were included in the regression model in order to analyse the results from both tasks.

Results

Demographics

The demographic characteristics of participants are shown in Supplementary Table 1. There were no significant differences in gender, age, grade and major among participants in tasks 1 and 2, nor in those who participated in both. The mean age of participants was around 20 years. More people in lower than higher grades participated in our tasks, and more participants majored in science and engineering than in other subjects. We found no significant difference (T = −0.43, P = 0.966) in comparison of digit memory accuracy between those who participated in task 2 only (n = 13) and those who participated in task 2 after finishing task 1, demonstrating that the findings were not confounded by learning effects.

Results of emotional memory: task 1

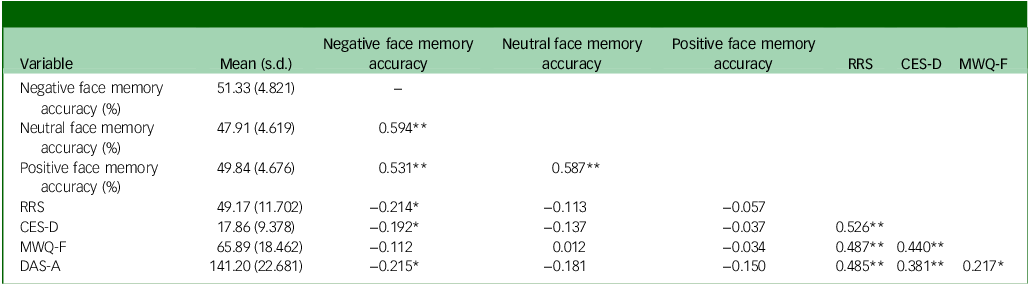

Correlation analyses

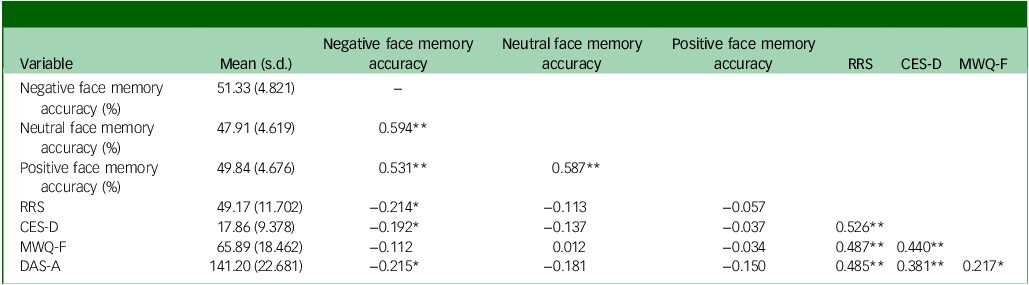

Correlation analysis was conducted to examine whether rumination, dysfunctional attitudes and mind-wandering were associated with face memory accuracy in task 1 (Table 1). The results indicated that the accuracy of negative face memory performance was negatively correlated with depression (P = 0.045), rumination (P = 0.025) and dysfunctional attitudes (P = 0.024), but not with mind-wandering. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the relationship between rumination/dysfunctional attitude and the accuracy of negative face memory performance. Neutral and positive face memory accuracy had no association with any of these variables (all P > 0.05). Negative, neutral and positive face memory reaction times showed no significant correlation with these variables, their mean values being 678, 670 and 669 ms, respectively.

Table 1 Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations in task 1

RRS, Rumination Responses Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; MWQ-F, Mind-Wandering Frequency Scale; DAS-A, Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Form A. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed).

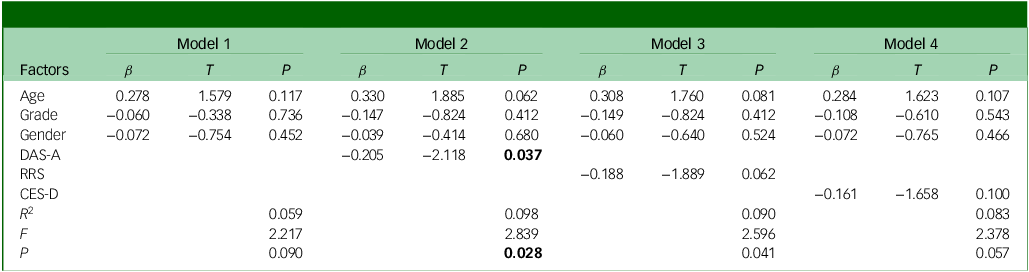

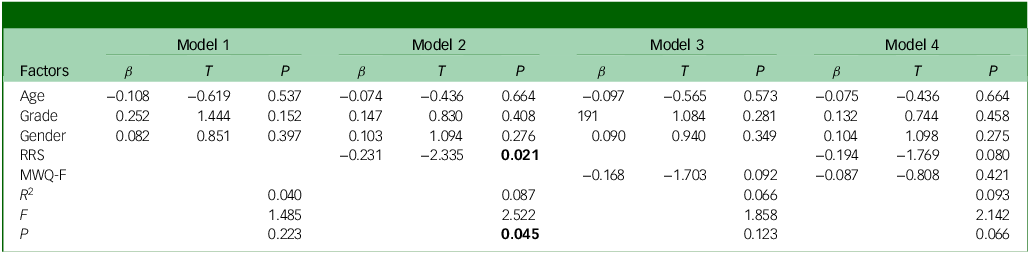

Linear regression analyses of task 1

We investigated variables that showed significance in the correlation analyses (dysfunctional attitudes, rumination and depression) and demographic factors (age, grade and gender) that might be predictive of negative face memory accuracy in a hierarchical regression equation. We first introduced the demographic factor in the first level (see model 1 in Table 2). Next, dysfunctional attitude, rumination and depression were placed in the second level to form models 2, 3 and 4, respectively. There was no significant predictor in the first-level equation. The model with the most robust explanatory power accounted for 9.8% of variance of negative face memory accuracy (R 2 = 0.098; see model 2 in Table 2), with dysfunctional attitude being the only significant predictor (β = −0.205, T = −2.118, P = 0.037). At the same time, neither rumination nor depression had significance as a predictor of negative face memory performance. When depression or rumination was included alone as the second-level variable in the equation (see models 3 and 4 in Table 2), or dysfunctional attitude − along with depression or rumination − was placed in the second level of the equation (see models 5–7 in Supplementary Table 2), there were no significant predictor variables. The variance inflation factor (VIF), which represents the degree of collinearity, was <3.8, demonstrating that there is no multicollinearity.

Table 2 Hierarchical linear regression analysis of task 1 for negative face memory accuracy

DAS-A, Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Form A; RRS, Rumination Responses Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale.

Bold font indicates P-values where both the model and variable are statistically significant.

Results of non-emotional memory: task 2

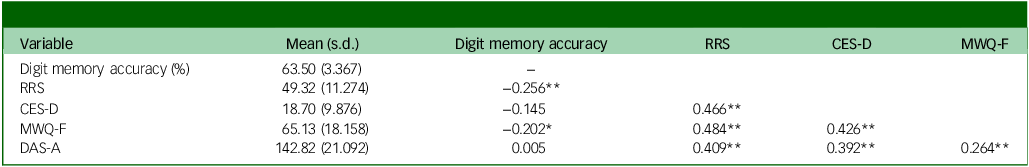

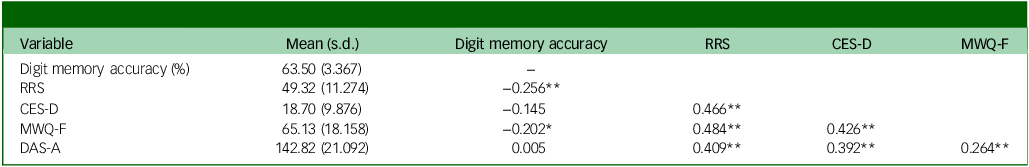

Correlation analyses

In the correlation analysis of task 2 (Table 3), we also focused on the correlation between digit memory performance accuracy and rumination, mind-wandering and dysfunctional attitudes. The results showed that digit memory accuracy was negatively correlated with rumination (P = 0.007) and mind-wandering (P = 0.034). The respective correlation curves between rumination/mind-wandering and digit memory accuracy can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 3. No evidence was found for an association between digit memory reaction time (mean value 932 ms) and psychological factors (rumination, depression, mind-wandering and dysfunctional attitude).

Table 3 Means, standard deviations and intercorrelations in task 2

RRS, Rumination Responses Scale; CES-D, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; MWQ-F, Mind-Wandering Frequency Scale; DAS-A, Dysfunctional Attitude Scale Form A. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (two-tailed).

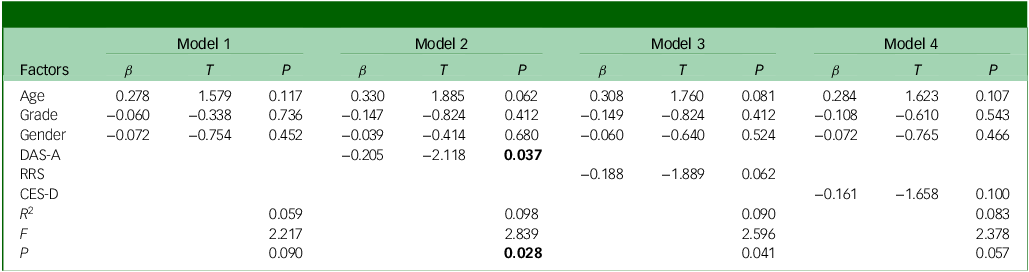

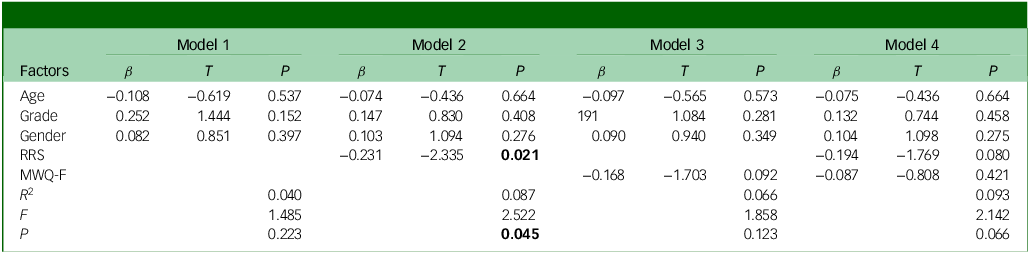

Linear regression analysis of task 2

First, demographic information (age, grade and gender) was entered into the model in task 2 representing first-level variables; no significant variables were found in the equation (see model 1 in Table 4). Two significant factors in correlation analyses (rumination and mind-wandering) were then included in the hierarchical regression. When rumination was added to the equation as the second-level variable, it became the only significant predictor of digit memory (β = −0.205, T = −2.118, P = 0.021), and this regression model explained 8.7% of the variance in numerical memory accuracy (R 2 = 0.087; see model 2 in Table 4). In equations where mind-wandering, or mind-wandering plus rumination, were included as second-level variables, no variable had a significant predictive role (see models 3 and 4 in Table 4). There was no multicollinearity in the results of this regression, with all VIF <3.8.

Table 4 Hierarchical linear regression analysis of task 2 for digit memory accuracy

RRS, Rumination Responses Scale; MWQ-F, Mind-Wandering Frequency Scale.

Bold font indicates P-values where both the model and variable are statistically significant.

Discussion

The present study examined the relations between rumination, dysfunctional attitudes and mind-wandering and emotional and non-emotional memory in a non-clinical sample. The level of face and digit memory accuracy was similar to that found in the results of previous experiments. Reference Gong, Zheng, Chen, Ge, Lv and Zhang4,Reference Harvey, Bodnar, Sergerie, Armony and Lepage33 Consistent with our hypotheses, we found that negative emotional memory was predicted by dysfunctional attitudes while non-emotional memory was predicted by rumination. Rumination and-mind wandering had correlations with emotional and non-emotional memory, respectively, but these correlations disappeared after controlling for potential demographic confounding factors. Our findings suggest that worse negative emotional memories are associated with a negative schema of dysfunctional attitude, and non-emotional memories may be disrupted by the negative, repetitive-thinking process known as rumination.

For emotional memory, we indicated the negative associations of dysfunctional attitudes with negative face memory. Dysfunctional schemas, which could be activated by negative valence stimuli, Reference Disner, Beevers, Haigh and Beck12 are a significant predictor of negative face memory. As suggested by research related to autobiographical memory, a dysfunctional attitude may cause participants to pay more attention to negative schemas and less to targeting emotional memories. Reference Spinhoven, Bockting, Kremers, Schene, Mark and Williams17 Consequently, this can hinder the detailed processing of complex facial information. Reference Spinhoven, Bockting, Kremers, Schene, Mark and Williams17 Moreover, one study among female college students supported the association between dysfunctional thinking and poor memory recognition of emotional and interpersonal information details. Reference Lehtonen, Jakub, Craske, Doll, Harvey and Stein34 Although rumination is also thought to disrupt the specificity of negative memories, Reference Williams8 the correlation between rumination and negative face memory in this study no longer existed after controlling for confounding factors. Taken together, dysfunctional attitudes may be the crucial predictor of poorer memory recognition of negative faces.

In addition, it should be noted that, although our findings are less consistent with previous evidence regarding the relationship between negative cognitive bias and depression, Reference Disner, Beevers, Haigh and Beck12 there is also evidence suggesting a potential negative association between depression and emotional memory capacity. Reference Guyer, Choate, Grimm, Pine and Keenan35 For instance, an earlier investigation found memory deficits for fearful faces among depressed children and adolescents. Reference Pine, Lissek, Klein, Mannuzza, Moulton and Guardino2 In the present study, depression also showed a negative correlation with negative face memory accuracy in the correlation test, but only dysfunctional attitude predicted negative face memory accuracy in the multiple-regression analysis. This suggests that the association of negative cognition with emotional memory may deserve more attention compared with depressive mood, especially in non-clinical samples without major depression. Considering the small sample size of this study, more research is needed to clarify the relationships among emotional memory, depression and dysfunctional attitude.

Regarding non-emotional memory, our findings highlight the role of rumination in digit memory. Mind-wandering and rumination are spontaneous thoughts that occur in daily life. Reference Poulos, Zamani, Pillemer, Leichtman, Christoff and Mills24 Moreover, rumination has been defined as mind-wandering with more constraints on negative content, and was established as a necessary factor for mind-wandering to relate to psychopathology and cognition. Reference van Vugt and van der Velde21,Reference Welz, Reinhard, Alpers and Kuehner36 Consequently, rumination may be more closely related to worsening non-emotional memory than mind-wandering. This is consistent with the findings of this study, which indicate that rumination can predict non-emotional memory while mind-wandering loses its correlation with non-emotional memory after controlling for confounding factors. The results suggest that, when people cannot inhibit negative repetitive thoughts unrelated to the task, it may interfere with the memory cognitive resources allocated to target material. Reference Randall, Oswald and Beier11,Reference Whitmer and Gotlib16 These findings are similar to the widely observed association of rumination and non-emotional working memory, Reference Whitmer and Gotlib16 indicating that rumination could be associated with both complex cognitive control and basic memory task performance.

There may be some disparities between the mechanisms underlying the association of emotional and non-emotional memory with cognitive factors. Emotional memory is closely associated with a dysfunctional attitude, which may be caused by its vulnerability to negative emotions. Non-emotional memory is associated with the negative, repetitive thinking of rumination. For negative emotional memory, when the negative schema-guided emotional processing is activated by negative stimuli, this could cause interference in remembering detailed facial information. Reference Spinhoven, Bockting, Kremers, Schene, Mark and Williams17,Reference Köhler, Carvalho, Alves, McIntyre, Hyphantis and Cammarota18 For non-emotional memory, when the ability to manage cognitive resources becomes rigid and difficult to self-control, Reference Kornacka, Skorupski and Krejtz22 it could allow a negative repetitive-thinking process to interfere with the process of digit memory. The present study helps us understand the cognitive factors negatively contributing to memory in different contexts. In this sample, the noteworthy cognitive factors of dysfunctional attitudes and rumination predicted emotional and non-emotional memory, respectively, supporting the notion Reference Liu, McArthur, Burke, Hamilton, Mac Giollabhui and Stange37 that cognitive deficits are not directly linked to mental symptoms but are mediated by cognitive phenotypes.

Our findings also provide insights into effective and targeted cognitive treatment for memory deficits. Based on existing research, classical cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) targeting dysfunctional attitudes may be related to the effect of improving emotional memory. Reference Quilty, McBride and Bagby38 Non-emotional cognition is also a stubborn symptom often resistant to intervention, Reference Roiser and Sahakian13 and requires more comprehensive treatment strategies. This study suggests that treatment focused on reducing rumination, e.g. rumination-focused CBT, Reference Watkins, Mullan, Wingrove, Rimes, Steiner and Bathurst39 has potential in improving non-emotional memory.

There are some limitations involved in this study. First, the linear regression R 2 value in this study was small. This could be attributed to the fact that a significant number of factors relate to memory, and cognitive factors are just one of many key factors demanding our attention. In addition, we used only memory accuracy to represent memory functions: reaction times did not show significance in our study. In order to incorporate greater emotional stimulus interference, the seen and unseen faces shown in task 1 of this study were not exactly equal. In addition, the correct rate of task 1 was not very high (at the 50% level), possibly due to participants’ overall engagement levels being potentially quite low. Future research could improve engagement by refining task design, such as adjusting reaction times and stimulus repetitions, as shown in prior works. Reference Harvey, Bodnar, Sergerie, Armony and Lepage33,Reference Guyer, Choate, Grimm, Pine and Keenan35 Also, due to the limited number of faces included in the design of task 1, our results show only the relationships of cognitive factors to overall negative face memory, and further research is needed on the specific types of emotions included. In addition, given the relatively small sample size and limited university student population, this study is a preliminary cross-sectional behavioural experiment that is expected to provide suggestions for future studies. More refined future studies could use path analysis to explore the indirect effects of different cognitive factors on memory.

The present cross-sectional study explored the relationships of rumination, dysfunctional attitudes and mind-wandering to emotional and non-emotional memory in a non-clinical sample. It is the first study to demonstrate that the worsening of negative face memory is closely associated with negative schema-dysfunctional attitudes. The study also highlights the fact that rumination is a significant predictor of worse non-emotional memory. The findings also suggest that the cognitive factors relating to emotional and non-emotional memories can differ. Furthermore, dysfunctional attitudes, as a negative schema, may be a target for intervention in emotional memory, while improving non-emotional memory is related more to rumination as a negative repetitive-thinking process.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2025.10930

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Y.J., upon reasonable request. All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank all participants for participating in this study.

Author contributions

S.T., Y.J. and Y.Y. co-conceptualised and co-designed the study. Y.J. reviewed the manuscript and supervised the review and revision process. Y.C., X.W. and Z.Z. recruited participants and collected data. Y.C. carried out the initial analysis. Y.C. and W.O. drafted and revised the manuscript. Y.R. revised the manuscript. C.K. contributed to statistical analysis. All authors have read and approved the manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 82101612), Hunan Provincial Degree and Graduate Student Education Reform Research Project (No. 2024JGYB035) and China Medical Board (No. 19-343). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, publication decisions or manuscript preparation.

Declaration of interest

None.

Ethical standards

All methods were carried out following the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation, and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 2013. Each participant provided written informed consent, and the study design was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committees of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (approval no. 2022-020).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.