Introduction

The prevalence of illicit and nonmedical substance use typically peaks during adolescence or young adulthood [1, Reference Degenhardt, Whiteford, Ferrari, Baxter, Charlson and Hall2]. These developmental periods are considered highly sensitive periods for brain maturation in the prefrontal cortical regions. These regions play a central role in high-level cognitive processes and continue to develop well into the mid-twenties [Reference Casey, Tottenham, Liston and Durston3–Reference Fuhrmann, Knoll and Blakemore5]. Disruptions in their development can result in impaired cognitive functions such as attention and memory, skills that are critical for effective daily and occupational functioning. Indeed, the use of illicit substances during these developmental periods has been linked to various functional impairments. For example, frequent cannabis use during adolescence negatively affects intellectual and educational performance [Reference Silins, Horwood, Patton, Fergusson, Olsson and Hutchinson6, Reference Meier, Caspi, Ambler, Harrington, Houts and Keefe7]. However, the cognitive consequences of exposure to the full spectrum of recreational substances in young adulthood are not fully understood. This study investigates the associations between cognitive functions and the most commonly used substances, such as cannabis, cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “Ecstasy”), opioids, ketamine, and dextromethorphan (DXM), which were measured by toxicological hair testing.

Cognitive effects of cannabis use

Cannabis is the most used illicit substance worldwide [8]. Its main psychoactive compound, Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), remains in the human body for a relatively long time [Reference Musshoff and Madea9]. Accordingly, it can cause both acute and post-acute effects on cognitive functions. Small-to-moderate doses of experimentally administered THC have been found to acutely reduce verbal learning and memory performance [Reference Zhornitsky, Pelletier, Assaf, Giroux, Li and Potvin10]. Meta-analyses of cross-sectional studies have consistently identified small-to-moderate associations between the post-acute effects of chronic cannabis use and reduced attention, memory, and executive function [Reference Lovell, Akhurst, Padgett, Garry and Matthews11, Reference Figueiredo, Tolomeo, Steele and Baldacchino12]. In turn, these functions improve with length of abstinence [Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur13, Reference Bourque and Potvin14].

Cognitive effects of cocaine use

The global supply and demand for cocaine are currently at record levels [15]. Since 2016, wastewater analyses in European cities have documented a steady increase in the concentration of benzoylecgonine, the main excreted metabolite of cocaine [16]. Similar trends have been observed in Australia and Brazil [15]. These trends are particularly concerning because both cocaine addiction [Reference Potvin, Stavro, Rizkallah and Pelletier17, Reference Jovanovski, Erb and Zakzanis18] and regular recreational cocaine use have been associated with reduced cognitive functions, specifically attention, working memory, and declarative memory [Reference Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller, Jenni, Baumgartner and Stohler19]. Neurodevelopmental impairments following cocaine exposure during adolescence have been reported in rodent models [Reference Harvey, Dembro, Rajagopalan, Mutebi and Kantak20–Reference Mottarlini, Racagni, Brambilla, Fumagalli and Caffino22]. Moreover, a younger age of onset of cocaine use has been associated with greater cognitive impairments in a large clinical sample of cocaine users confirmed by hair testing [Reference Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller, Jenni, Baumgartner and Stohler19].

Cognitive effects of substituted amphetamines

Ecstasy, which typically contains the substituted amphetamine derivative MDMA, is another commonly used substance among young adults [8, 23]. Previous research has reported cross-sectional associations between frequent self-reported and hair-tested MDMA use and chronic impairments, particularly in declarative memory [Reference Kalechstein, De La Garza, Mahoney, Fantegrossi and Newton24–Reference Quednow, Jessen, Kühn, Maier, Daum and Wagner26]. Similarly, a few small longitudinal studies have suggested that MDMA use induces memory deficits in novice users that persist after long-term abstinence, possibly because of its neurotoxic effects [Reference Schilt, Maartje De Win, Koeter, Jager and Korf27–Reference Zakzanis and Young29]. Regarding the non-medical use of methamphetamine, inhibitory control has been identified as the most strongly affected cognitive domain in young users [Reference Guerin, Bridson, Plapp and Bedi30]. Notably, among individuals with methamphetamine use disorder, deficits in attention, executive functioning, as well as visual learning and memory have been observed [Reference Potvin, Pelletier, Grot, Hébert, Barr and Lecomte31]. Finally, in rodents, adolescent exposure to amphetamine-type stimulants, such as MDMA, amphetamine, and methamphetamine, is associated with worse learning and working memory [Reference Teixeira-Gomes, Costa, Feio-Azevedo, de Lourdes Bastos, Carvalho and Capela32].

Cognitive effects of prescription opioids, dissociatives, and polysubstance use

Nonmedical use of prescription opioids, such as opioid painkillers (e.g., morphine, oxycodone) and cough syrup (e.g., codeine), has recently reached epidemic proportions in the US [Reference Judd, King and Galke33] and has increased steadily in Europe [8]. However, the effects of chronic nonmedical use of prescription opioids on cognition are poorly understood. To date, a single study employing hair testing has suggested that frequent nonmedical opioid use is associated with reduced attention and declarative memory performance [Reference Kroll, Nikolic, Bieri, Soyka, Baumgartner and Quednow34].

Studies of cognitive impairments associated with less frequently used substances are also limited. For example, chronic ketamine use has been linked with impairments in several memory functions and attention [Reference Morgan and Curran35, Reference Ke, Ding, Xu, He, Wang and Deng36], which appear to be more pronounced with an adolescent onset of use [Reference Acevedo and Siegel37]. Systematic studies examining the chronic effects of DXM use on cognition are lacking, but one case report suggested potential neuropsychological deficits after long-term use [Reference Hinsberger, Sharma and Mazmanian38]. Finally, there is limited research on the cognitive consequences of polysubstance use, despite its high prevalence in early adulthood [Reference Steinhoff, Bechtiger, Ribeaud, Eisner, Quednow and Shanahan39]. However, preliminary data suggest that polysubstance use, including stimulants or MDMA, is associated with widespread cognitive deficits affecting attention, working memory, declarative memory, and socio-cognitive functioning [Reference Wunderli, Vonmoos, Fürst, Schädelin, Kraemer and Baumgartner25, Reference Kroll, Wunderli, Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller and Bosch40].

Limitations of previous studies

Previous research on substance use and cognitive functions has largely focused on small samples of individuals with chronic and regular use patterns. While these studies offer valuable insights into high-risk populations, they are susceptible to selection bias [Reference Tyrer and Heyman41] and represent only a small fraction of the overall user population. Casual or recreational use, which is far more prevalent, has been investigated less frequently, particularly in community-based samples. Moreover, most prior studies relied on self-reported substance use measures, often of questionable validity [Reference Steinhoff, Shanahan, Bechtiger, Zimmermann, Ribeaud and Eisner42], or have focused on a narrow range of single substances, even though polysubstance use is now the norm rather than the exception [Reference Bailey and McHugh43].

In addition, most studies have adjusted for only a limited set of confounders, such as age, sex, and education, without accounting for broader sociodemographic or lifestyle factors that significantly influence cognitive functioning at the population level. Research on age-related cognitive declines, for example, underscores the importance of socioeconomic status (SES) and migration background (e.g., [Reference Steinhoff, Shanahan, Bechtiger, Zimmermann, Ribeaud and Eisner42–Reference Larnyo, Dai, Nutakor, Ampon-Wireko, Larnyo and Appiah44]). These covariates should also be considered in studies of adolescents and young adults [Reference Leonard, Mackey, Finn and Gabrieli45–Reference Moss, Zhang, Tamplain and Gu47]. Furthermore, in the context of computerized tests of cognitive functions, prior experience with specific tasks, such as playing action video games, may enhance performance (see, e.g., the meta-analysis by [Reference Bediou, Adams, Mayer, Tipton, Green and Bavelier48]), which is particularly relevant for younger age groups. Finally, lifestyle factors such as smoking [Reference Lydon, Wilson, Child and Geier49–Reference Chamberlain, Odlaug, Schreiber and Grant52] and frequent alcohol use [Reference Kopera, Wojnar, Brower, Glass, Nowosad and Gmaj53–Reference Scaife and Duka55] have been consistently linked with cognitive performance.

Aim of the present study

For years, there have been calls for more evidence-based drug policies [Reference Nutt, King, Saulsbury and Blakemore56]. The cognitive consequences of substance use among adolescents and young adults are an important part of this evidence, especially in view of the global increase in use among these age groups [57] and the ongoing debate on the legalization of cannabis and other substances [Reference Csete, Kamarulzaman, Kazatchkine, Altice, Balicki and Buxton58]. The aim of this study was to investigate associations of substance use and cognitive performance in a large community study of young adults with known high prevalence and intensity of use of a broad range of substances [Reference Quednow, Steinhoff, Bechtiger, Ribeaud, Eisner and Shanahan59]. To objectively confirm and quantify substance use, we used hair testing, which is sensitive to many compounds and enabled us to detect occasional or recreational use of substances (except for cannabis, for which hair testing typically captures highly regular use only [Reference Steinhoff, Shanahan, Bechtiger, Zimmermann, Ribeaud and Eisner42, Reference Taylor, Lees, Henderson, Lingford-Hughes, Macleod and Sullivan60]). In addition to single substances, we measured polysubstance use. Finally, we adjusted for several known confounders in multivariable regression models, such as sex, SES, migration background, education, gaming experience, and tobacco and alcohol use.

Based on previous findings, we expected that (1) regular cannabis use is associated with decreased attention and declarative memory [Reference Lovell, Akhurst, Padgett, Garry and Matthews11–Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur13]; (2) cocaine use is associated with decreased attention, working memory, and declarative memory [Reference Potvin, Stavro, Rizkallah and Pelletier17–Reference Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller, Jenni, Baumgartner and Stohler19]; (3) MDMA use is associated with decreased declarative memory [Reference Kalechstein, De La Garza, Mahoney, Fantegrossi and Newton24–Reference Quednow, Jessen, Kühn, Maier, Daum and Wagner26]; (4) prescription opioid use is associated with decreased attention and declarative memory [Reference Kroll, Nikolic, Bieri, Soyka, Baumgartner and Quednow34]; (5) ketamine use is associated with decreased declarative memory [Reference Morgan and Curran35, Reference Ke, Ding, Xu, He, Wang and Deng36]; (6) DXM use is associated with decreased working and declarative memory [Reference Hinsberger, Sharma and Mazmanian38]; and (7) polysubstance use is associated with decreased attention, working memory, and declarative memory (38).

Methods and materials

Participants

We used data from the Zurich Project on Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood (z-proso), a prospective, longitudinal, community-based cohort study initiated in 2004 to investigate the social, emotional, and behavioral development of children and to identify risk and protective factors for antisocial behavior and mental health across the life course [Reference Ribeaud, Murray, Shanahan, Shanahan and Eisner61]. The cohort was designed to be representative of children entering first grade in the city of Zurich in August 2004 (target sample N = 1,675). For the current analysis, no exclusion criteria were applied beyond the availability of valid hair samples and cognitive test data in the ninth assessment wave (W9) when participants were 24 years old (M = 24.5, SD = 0.4, range = 23.1 to 25.9). The absence of additional exclusion criteria ensured that the community population was represented as closely as possible.

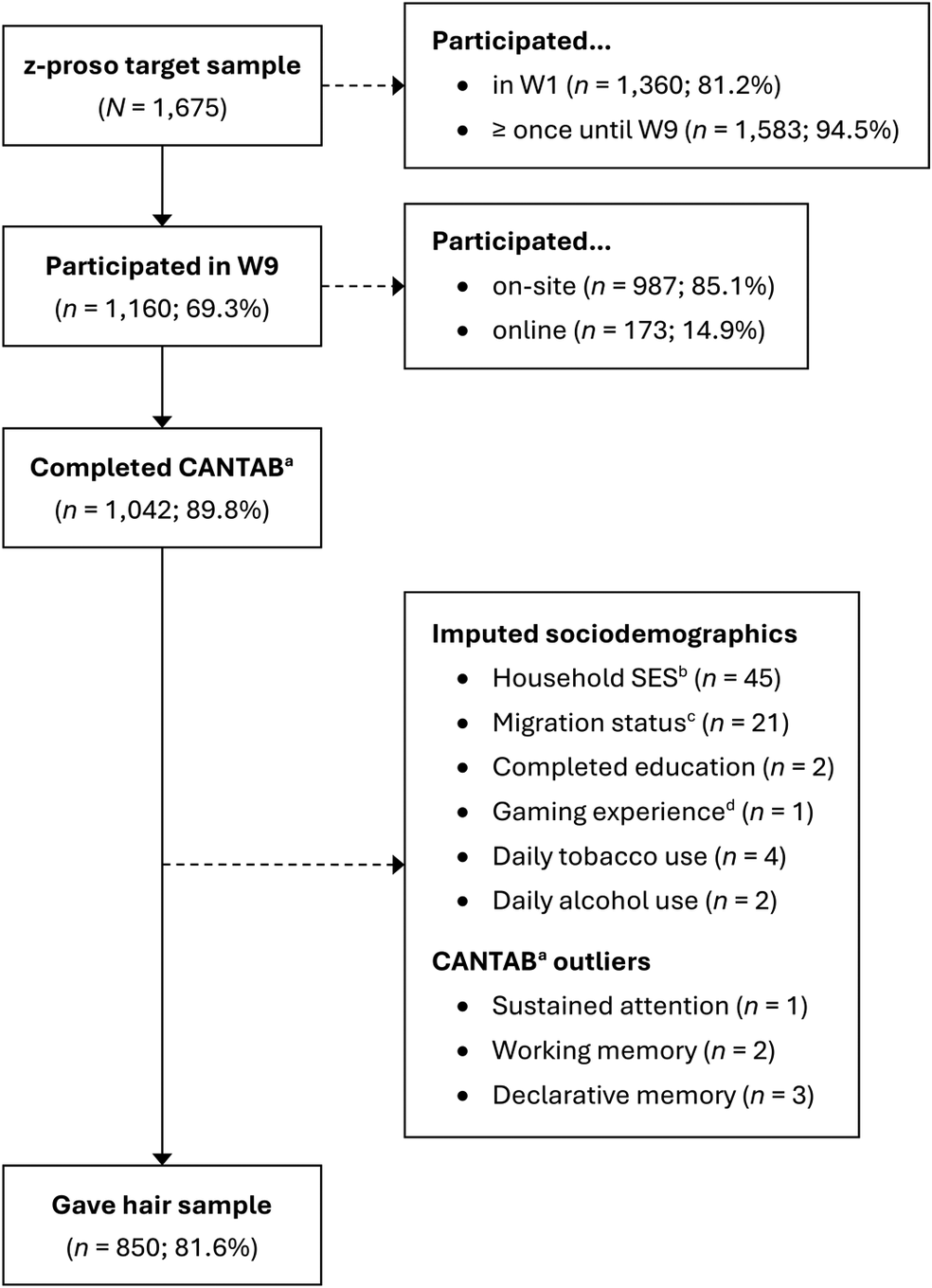

Of the 1,160 participants assessed in W9, 1,042 (89.8%) completed the cognitive test battery, 887 (76.5%) provided a hair sample, and 850 (73.3%) both, completed the cognitive tests and provided a hair sample (Figure 1). Six participants in the cognitive test sample (n = 1,042) had outliers, which were replaced by missing values (Supplementary Figure S1). A random forest algorithm was used to impute the sociodemographic information of 71 participants. Information on sample agreement rates is provided in Supplementary Text S1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram for study sample (n = 850).

Note. N/n = number of participants. W1 – W9 = assessment waves, ranging from age 7 (W1) to age 24 (W9).

a Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery.

b Socioeconomic status assessed with the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status, ranging from 14 (unskilled worker) to 90 (judge).

c Positive migration background if both parents were not born in Switzerland.

d Frequency of playing action-packed video games in the past year, averaged across ages 20 and 24.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human subjects were approved by the Cantonal Ethics Committee Zurich (BASEC #2017-02021) and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences of the University of Zurich. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants received monetary compensation for completing the survey, the cognitive tests, and for providing a hair sample (on-site: 150 CHF, 50 CHF, and 30 CHF; online: 100 CHF, 40 CHF, and 50 CHF, respectively).

Measures

Sociodemographic and lifestyle factors

Information was collected on participants’ sex assigned at birth (0 = male, 1 = female); the SES of the household in which they grew up (ranging from 16 = unskilled worker to 90 = judge), using the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status ([Reference Ganzeboom, De Graaf and Treiman62]); migration background (0 = at least one parent born in Switzerland, 1 = both parents not born in Switzerland), and highest completed education (0 = below apprenticeship, 1 = apprenticeship, 2 = vocational tertiary, 3 = academic tertiary). Participants reported their experience of playing action-packed violent computer or video games in the past year (e.g., first-person shooters; ranging from 1 = never to 7 = daily) and their daily tobacco and alcohol consumption (dichotomized as 0 = never or less than daily and 1 = daily). A more detailed overview of these assessments is shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Mental health symptoms

To evaluate mental health symptoms, the anxiety-depressive (internalizing) and ADHD (externalizing) symptom scales from the Social Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ; [Reference Tremblay, Loeber, Gagnon, Charlebois, Larivée and LeBlanc63]) were used. Participants rated in eight items how often they experienced internalizing symptoms (e.g., “couldn’t enjoy anything”) in the previous month and in four items externalizing symptoms (e.g., “were easily distracted”) in the past 12 months. Responses were provided on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Previous studies have established the SBQ’s adequate psychometric properties in the z-proso study [Reference Murray, Obsuth, Eisner and Ribeaud64].

Hair toxicological analysis

The concentration of 114 substances and metabolites in the hair of the participants was determined by a validated liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) method. After washing (water, acetone, hexane) and extraction, analytes were separated on Kinetex® C18 (THC, CBD, CBN)/F5 columns (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) and detected in scheduled multiple reaction monitoring mode, using a QTrap 5500 system (Sciex, Marlborough, MA, USA) with atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/electrospray ionization, depending on analyte class. The method was revalidated for selectivity, linearity (r ≥ 0.98), limits of quantification (0.5–100 pg/mg depending on analyte), accuracy and precision (acceptance criteria ±30% RSD for the bias, RSDR ≤ 30%, and RSDT ≤ 30% for the repeatability and the intermediate precision), and robustness (RSD ±30%), according to forensic toxicology guidelines. Full validation data are available elsewhere [Reference Scholz, Cabalzar, Kraemer and Baumgartner65, Reference Scholz, Baumgartner, Kraemer and Binz66].

Since at least 3 cm of hair was analyzed for each sample, except for eight samples with ≥1.5 cm, the concentrations approximately reflected the cumulative substance exposure over the 3 months prior to the assessment. Importantly, THC in hair can only be detected in the context of regular use [Reference Steinhoff, Shanahan, Bechtiger, Zimmermann, Ribeaud and Eisner42, Reference Taylor, Lees, Henderson, Lingford-Hughes, Macleod and Sullivan60]. For the present study, we grouped related substances and their metabolites into categories and converted medical opioids into morphine-equivalent concentrations, according to (32) and (65). To avoid power constraints, we only considered substance categories with n > 30 positive cases. We also employed a polysubstance use severity index (PSUSI; [Reference Kroll, Wunderli, Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller and Bosch40]), which was calculated for each participant by summing tertial scores of hair concentration levels (not detected = 0, low = 1, medium = 2, high = 3) across all substances. For example, a person with a medium level of MDMA [level 2], a high level of cocaine [level 3], and a low level of ketamine [level 1] received a PSUSI of 6. All substance concentrations were log-transformed using the formula log(x + 1) to facilitate linear estimation. An overview of the substance use variables and morphine equivalents (ME) is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

Cognitive test battery

We used the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB; [67]), which is a fully computerized nonverbal cognitive test battery. We used three tasks: rapid visual processing (measure: A prime) to assess sustained attention, spatial working memory (measure: total errors) to assess visuospatial working memory performance, and paired associates learning (PAL; measure: adjusted total errors) to assess declarative visuospatial memory performance. We inverted the working memory and declarative memory scores so that positive values indicated positive performance. Furthermore, we calculated a total cognitive score by creating a sum score across the three z-standardized and, if applicable, inverted individual tasks.

Statistical analysis

We regressed hair substance concentrations as a continuous dose variable and all covariates onto the four CANTAB scores, estimating both bivariate and multivariable associations. We also estimated the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for each substance by comparing the marginal mean CANTAB scores of participants without any substance concentration to those with (a) any substance concentration and (b) low, medium, and high concentrations (i.e., concentration levels), based on a tertile split. More details are provided in the Supplementary (Text S2). Finally, we conducted robustness checks by including internalizing and externalizing symptoms as additional covariates to adjust for potential confounding of psychiatric symptoms. Notably, these scales were not part of our a priori covariate set but were included post hoc due to their conceptual relevance to both substance use and cognitive outcomes. All calculations were performed using R version 4.3.2 statistical software [68].

Results

Sample descriptives

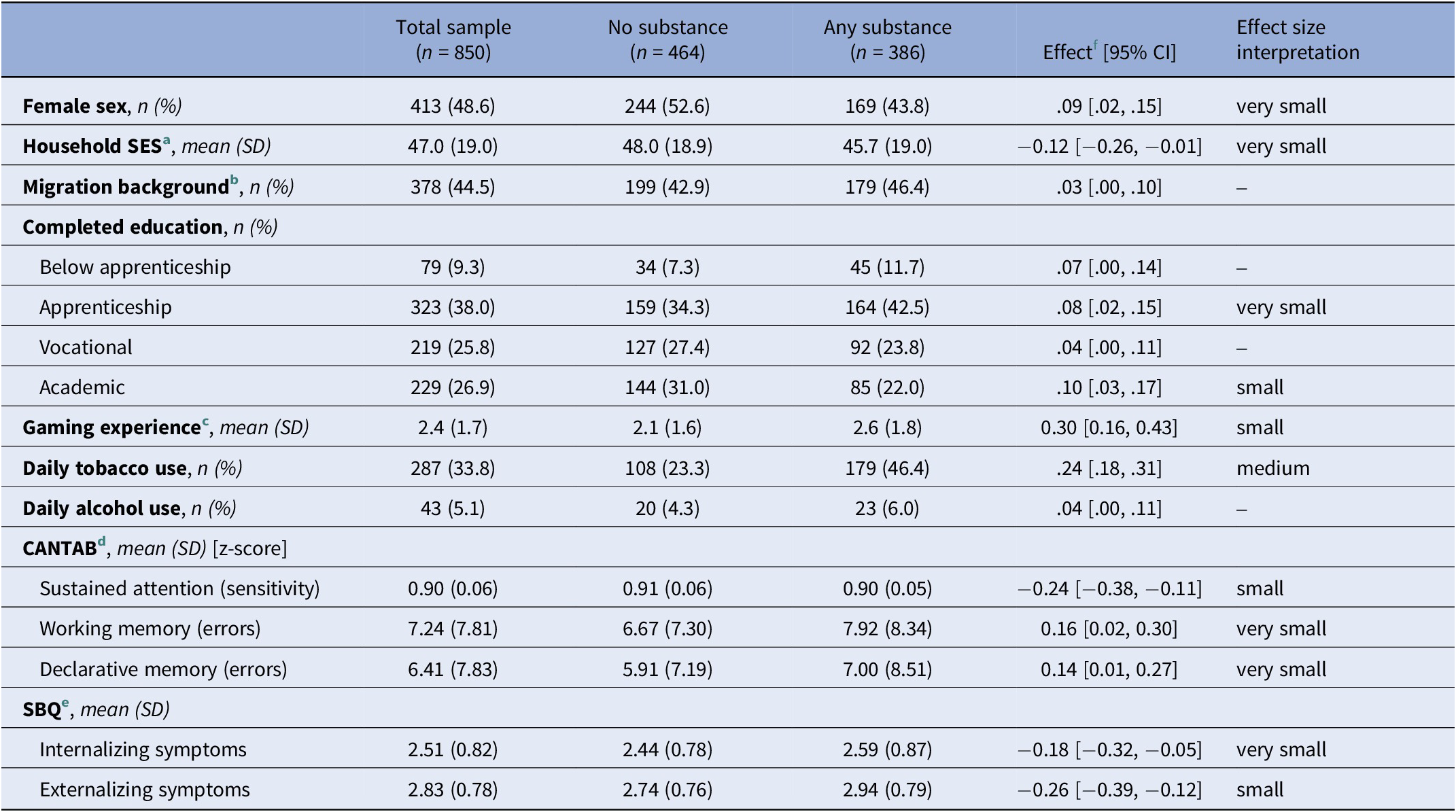

Approximately half of the sample was female (48.6%), and 44.5% had a migration background. Complete descriptives are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics stratified by any kind of illicit substance detected in hair

Note. n = number of participants.

a Socioeconomic status assessed with the International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status, ranging from 14 (unskilled worker) to 90 (judge).

b Positive migration background if both parents were not born in Switzerland.

c Frequency of playing action-packed video games in the past year, averaged across ages 20 and 24.

d Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery.

e Social Behavior Questionnaire.

f Cohen’s d for numeric and Cramer’s V for nominal variables, with two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI).

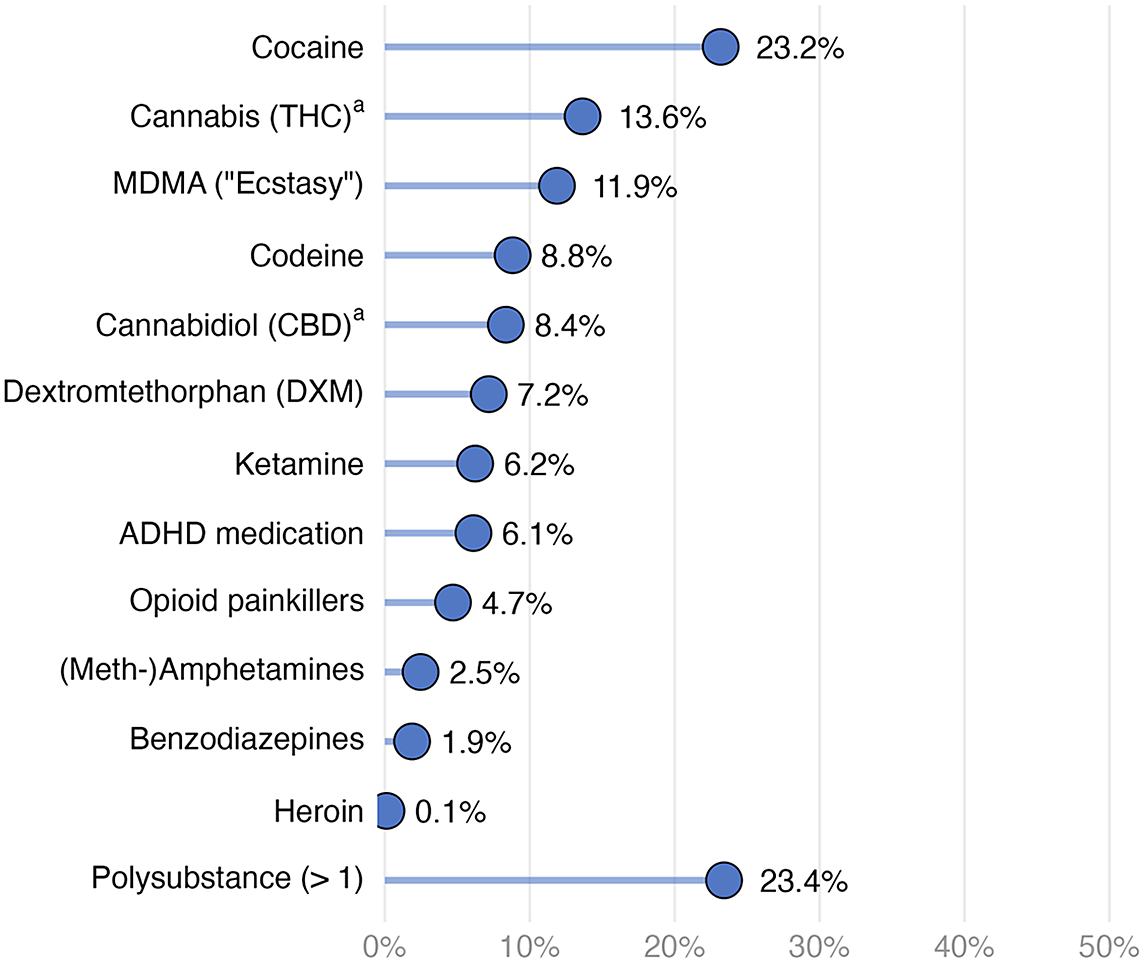

Figure 2 shows that cocaine was the most prevalent (23.2%) illegal substance detected in hair, followed by THC (13.6%, indicating regular cannabis use only), MDMA (11.9%), and codeine (8.8%). Substances with fewer than 30 positive cases (i.e., amphetamines other than MDMA, benzodiazepines, and heroin) were not included in further analyses due to power constraints. Among substances with at least 30 cases, opioid painkillers had the lowest prevalence rate (4.7%). Approximately a quarter of the participants tested positive for more than one substance (23.4%). The distribution of hair concentrations revealed that most substances were typically used occasionally or recreationally (Supplementary Figure S2), except for THC, where detection in hair reflects regular use.

Figure 2. Prevalence of substances in hair (n = 850).

Note. Polysubstance means at least two different substances being detected in hair. Substances with n < 30 (i.e., (meth-)amphetamines, benzodiazepines, and heroin) were not included in the analyses due to power constraints.

a Prevalence rates for THC and CBD reflect frequent (weekly+) use.

Bivariate correlations and detailed descriptive statistics of covariates and cognition scores are provided in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4.

Substance use and cognitive functions

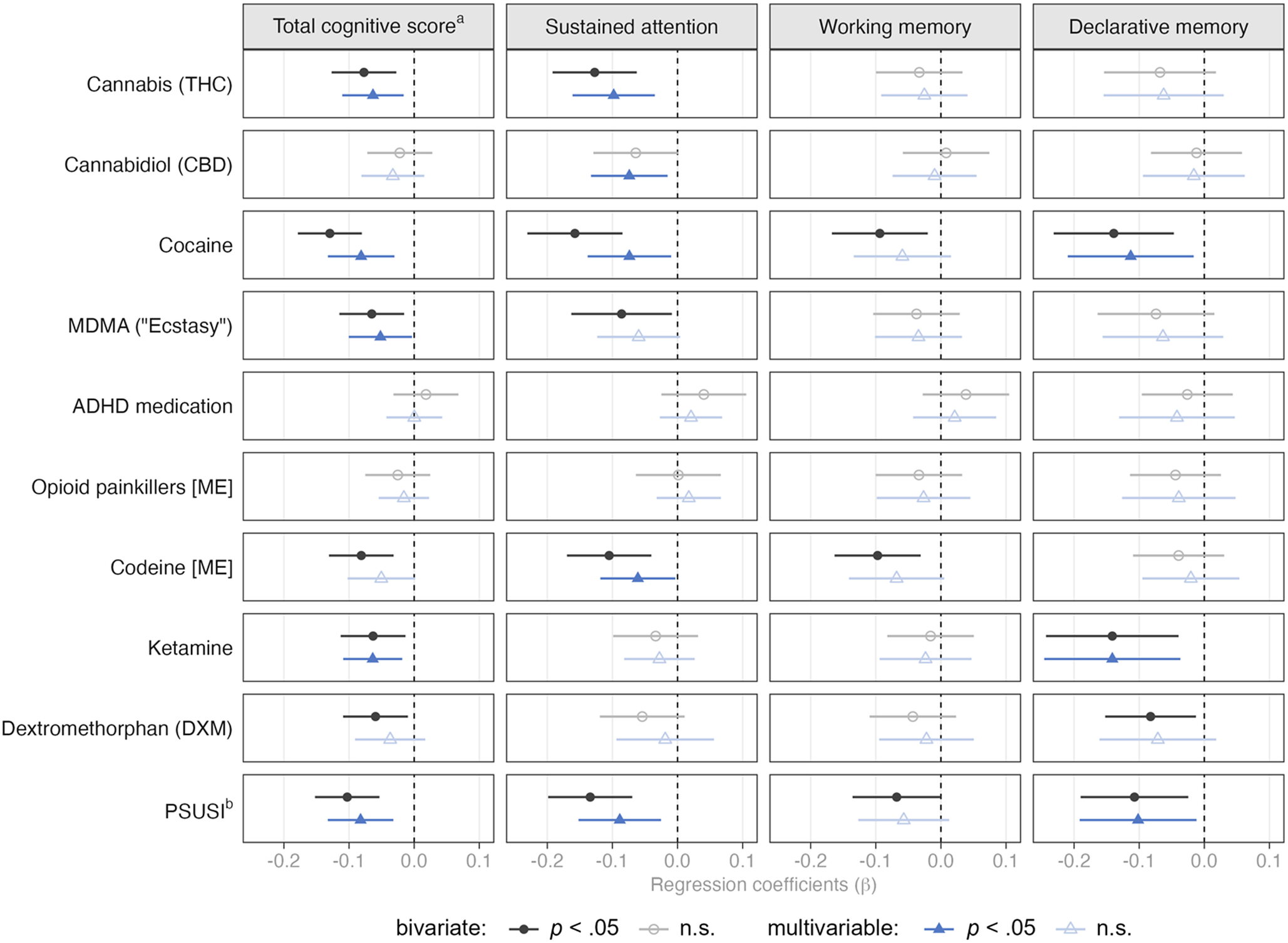

Multivariable regression analyses indicated that higher THC concentrations were associated with worse total cognitive performance and worse performance on sustained attention (Figure 3). When examining concentration levels (low/medium/high; Supplementary Table S5), we found that THC concentrations at the lower end – which still indicate regular use – seemed to drive this association. For cocaine, higher concentrations were associated with worse cognitive performance on the total cognitive score, sustained attention, and declarative memory. Particularly, the highest cocaine concentration levels were associated with poorer performance. MDMA concentrations were negatively associated with the total cognitive score only after adjusting for covariates. Here, primarily medium concentration levels were associated with worse performance. Interestingly, the association between medium concentrations of ADHD medications and working memory performance was positive. However, this was only evident when examining concentration levels and not the continuous dose variable.

Figure 3. Bivariate and multivariable associations between substance concentrations in hair and cognitive functions.

Note. Multivariable models include sex, household SES, migration background, education, gaming experience, daily tobacco use, and daily alcohol use as control variables. [ME] = morphine equivalents.

a Total cognitive score reflects mean score of the three CANTAB scores on sustained attention (z-standardized), declarative memory (inverted and z-standardized), and working memory (inverted and z-standardized).

b Polysubstance-Use Severity Index.

The association of codeine and sustained attention was negative, mainly driven by high concentration levels. Notably, low doses were associated with worse working memory performance, but only when considering concentration levels and not the continuous dose variable. Ketamine concentrations were negatively associated with total cognitive and declarative memory performance, particularly at low and high concentration levels. The PSUSI was negatively associated with total cognitive performance, sustained attention, and declarative memory, particularly for medium and high PSUSI levels.

In contrast to the multivariable regressions, much stronger effects were observed in the bivariate unadjusted regression models, highlighting the need to adjust for confounders when assessing associations of substance use and cognition. Detailed bivariate and multivariable model estimates are presented in the Supplementary (Figures S3, S4, S5, and S6).

Finally, a higher percentage of participants using substances deviated more than 1.5 or 2 standard deviations from the mean cognitive scores than participants not using substances (Supplementary Table S6). Additional robustness checks, which adjusted the regression models for internalizing and externalizing symptoms, did not significantly change any of the associations between substance concentrations and cognitive functions (Supplementary Figure S7).

Discussion

Summary of results

This study examined cross-sectional associations between substance concentrations in hair and cognitive functions in a large community sample of young adults, primarily exhibiting recreational use patterns [Reference Quednow, Steinhoff, Bechtiger, Ribeaud, Eisner and Shanahan59, Reference Janousch, Eggenberger, Steinhoff, Johnson-Ferguson, Bechtiger and Loher69]. Specific substances were associated with distinct cognitive functions: Sustained attention was reduced in users of cannabis, cocaine, and codeine, as well as in young adults with polysubstance use. Declarative visuo-spatial memory was reduced in young adults with cocaine or ketamine use as well as in those with polysubstance use. Total cognition was poorer in young adults with cannabis, cocaine, MDMA, ketamine, and polysubstance use. In contrast, visuo-spatial working memory was largely not associated with substance use after adjusting for covariates.

Substance-specific associations with cognitive functions

Confirming our first hypothesis, higher THC hair concentrations in presumed regular cannabis users (n = 116) were associated with poorer total cognitive performance (any use: d = 0.31) and worse attention (d = 0.40), which is consistent with recent meta-analyses [Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur13, Reference Bourque and Potvin14]. The expected association with declarative memory (d = 0.20) was not significant, although a meta-analysis found the largest effect sizes in the learning domain and significant results for delayed memory [Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur13]. However, most of the studies included in this meta-analysis tested verbal declarative memory, and very few tested visuo-spatial associative learning, as we did. Given that a study of long-term daily cannabis users showed that verbal memory was significantly more impaired than visuospatial memory (including the PAL) [Reference D’Souza, Ganesh, Cortes-Briones, Campbell and Emmanuel70], the PAL was likely not the optimal test to reliably detect memory deficits in weekly to daily cannabis users.

Notably, our study identified individuals with cannabis use through hair testing, which primarily detects weekly to daily use [Reference Steinhoff, Shanahan, Bechtiger, Zimmermann, Ribeaud and Eisner42, Reference Taylor, Lees, Henderson, Lingford-Hughes, Macleod and Sullivan60, Reference Janousch, Eggenberger, Steinhoff, Johnson-Ferguson, Bechtiger and Loher69]. Our marginal means analyses suggest that even low THC concentrations in hair are associated with reduced attention. THC concentrations in hair may be a less reliable reflection of actual cannabis use intensity, which contrasts with other substances measured in hair such as cocaine [Reference Kroon, Cousijn, Filbey, Berchtold, Binz and Kuhns71, Reference Grison, Johnson-Ferguson, Vonmoos, Baumgartner and Quednow72]. Considering the meta-analysis by Scott et al. [Reference Scott, Slomiak, Jones, Rosen, Moore and Gur13], our findings likely reflect post-acute effects of frequent cannabis use on sustained attention. Reduced attention due to cannabis use is highly relevant in the context of the recent debate on cannabis legalization, especially considering that cannabis legalization in the US has increased the prevalence rates of cannabis use among young adults [Reference Patrick, Miech, Johnston and O’Malley73]. These findings underscore the need for a comprehensive prevention and harm reduction strategy within the cannabis legalization discourse, aimed at informing the public and mitigating the potential cognitive consequences of increasing cannabis use among young adults.

Regarding our second hypothesis, higher cocaine hair concentrations among occasional cocaine users (n = 197 tested positive) were associated with slightly worse total cognitive performance (any use: d = 0.24), attention (d = 0.21), and declarative memory (d = 0.20), but not with working memory performance (d = 0.10). Although previous meta-analyses [Reference Bourque and Potvin14, Reference Jovanovski, Erb and Zakzanis18] reported larger effect sizes, the included studies primarily focused on chronic and dependent users with intensive consumption. Similarly, a large study that also investigated recreational users [Reference Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller, Jenni, Baumgartner and Stohler19] found stronger effect sizes for these cognitive domains (d = 0.43–0.44). However, those participants were regular users, averaging 1.1 g of cocaine per week, and exhibited much higher cocaine hair concentrations (mean: 3347 pg/mg), compared to the present sample (mean: 1645 pg/mg). The weaker association with working memory (i.e., only bivariate) may be explained by the fact that working memory deficits are partially reversible with prolonged cocaine abstinence or reduced use [Reference Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller, Minder, Baumgartner and Quednow74]. Consequently, occasional users with infrequent consumption may recover their performance. Our results suggest that high cocaine concentrations appear to underlie cognitive performance impairments (Supplementary Table S5), as effect sizes were largest for high users (total cognitive performance: d = 0.52, attention: d = 0.40, declarative memory: d = 0.45, working memory performance: d = 0.25) and within the range of previously published effect sizes [Reference Bourque and Potvin14, Reference Jovanovski, Erb and Zakzanis18, Reference Vonmoos, Hulka, Preller, Jenni, Baumgartner and Stohler19]. While low-to-moderate doses may be less likely to cause clinically significant cognitive impairments, the strikingly high prevalence rate of approximately 23% remains concerning, not only due to cocaine’s high addictive potential but also because of its well-documented adverse effects on mental and physical health [Reference Nutt, King, Saulsbury and Blakemore56, Reference Degenhardt and Hall75].

We also hypothesized an association between MDMA use (n = 101) and impaired declarative memory performance; however, we observed only an association with total cognition (any use: d = 0.25) and a bivariate association with reduced attention (d = 0.25), which aligns with findings from a previous meta-analysis [Reference Kalechstein, De La Garza, Mahoney, Fantegrossi and Newton24]. The relatively high prevalence of concurrent use of MDMA with other substances, such as cannabis and cocaine (n = 14 pure MDMA users, or 13.9% of all MDMA users), suggests that the attention and global cognitive effects associated with cannabis and cocaine use (see above) may have influenced this population. Moreover, MDMA users in this sample were predominantly rare occasional users, as reflected by the relatively low MDMA hair concentrations (mean 460 pg/mg, median 54 pg/mg). In contrast, previous studies from our laboratory that reported large effects sizes for declarative memory deficits examined individuals with substantially more intensive MDMA use ([Reference Wunderli, Vonmoos, Fürst, Schädelin, Kraemer and Baumgartner25]: mean 3414 pg/mg; [Reference Coray, Zimmermann, Haugg, Baumgartner, Steuer and Seifritz76]: mean 4828 pg/mg; [Reference Coray, Beliveau, Zimmermann, Preller, Wunderli and Baumgartner77] median: 819 pg/mg). Importantly, in MDMA users, verbal declarative memory performance was more strongly affected than visuospatial memory [Reference Kalechstein, De La Garza, Mahoney, Fantegrossi and Newton24, Reference Wunderli, Vonmoos, Fürst, Schädelin, Kraemer and Baumgartner25]. A verbal memory test would therefore have been more sensitive to detecting MDMA-related memory deficits.

We found a significant association between impaired attention (any use: d = 0.22) and intake of codeine (n = 75), an opioid commonly found in cough medications, which we analyzed separately from opioid painkillers, such as oxycodone. However, the latter did not show the hypothesized associations with attention or declarative memory. This lack of association may be due to the small number of opioid painkiller users in our sample (n = 40), who exhibited only sporadic use (mean ME 154 pg/mg, median ME 20 pg/mg in hair). By contrast, a previous study of prescription opioid users [Reference Kroll, Nikolic, Bieri, Soyka, Baumgartner and Quednow34] (mean ME 543 pg/mg) reported stronger deficits in attention (Hedge’s g = 0.85) and declarative memory (g = 0.66). Notably, 52% of participants in that study used codeine or dihydrocodeine, which aligns well with our findings for codeine. Notably, reduced attention was primarily associated with higher codeine concentrations, which are typically required to achieve the euphoric effects linked to codeine use. This suggests that the observed effects may stem from nonmedical use of codeine-containing medications.

We further observed the hypothesized association between ketamine exposure (n = 53) and impaired declarative memory (any use: d = 0.59), which represented the strongest effect in our sample, despite relatively low hair concentrations. These memory deficits are consistent with previous studies on chronic ketamine users, which reported significant impairments, particularly in tasks involving visual stimulus material [Reference Zhang, Xu, Zhang, Hao and Tang78–Reference Liang, Lau, Tang, Chan, Ungvari and Tang80]. In contrast, we found no unique association between DXM exposure (n = 61) and cognitive performance after adjusting for covariates. While DXM hair concentrations likely reflect its medical use as a cough suppressant, the primary medical use of ketamine, as an anesthetic or for treatment-resistant depression, are unlikely in this young community sample.

We also observed the expected associations between polysubstance use severity (as measured by the PSUSI) and impairments in total cognition (d = 0.21), attention (d = 0.17), and declarative memory (d = 0.12), but not working memory (d = 0.15) after adjusting for covariates. Overall, polysubstance use showed the strongest effects, likely due to its combined number and intensity of different substances. This cumulative exposure may be particularly detrimental to cognitive functioning, even within the recreational and non-dependent use patterns observed in this community sample.

Sample characteristics

The sample composition and characteristics warrant discussion. First, the prevalence of substance use in this sample is remarkably high, even for Zurich, which typically reports high rates for substances such as cannabis, cocaine, MDMA, and ketamine based on wastewater analyses [16]. The estimated prevalence of cocaine use of approximately 23% is particularly striking. According to recent work [Reference Grison, Johnson-Ferguson, Vonmoos, Baumgartner and Quednow72], a median hair cocaine concentration of 157 pg/mg corresponds to a consumption of roughly 0.13 g/week, whereas the average use in the 95th percentile equals approximately 15.7 g per week. Furthermore, the sample was predominantly well educated, with more than half of participants having completed tertiary education (vocational or academic). Although some self-selection bias may have occurred because participants could choose whether to provide a hair sample, only 10.1% attending the on-site assessment declined to do so.

Notably, although our interpretation assumes that psychoactive substance exposure may contribute to cognitive impairment, the reverse direction cannot be ruled out due to the cross-sectional design of this study. Individuals with pre-existing lower cognitive functioning or executive control may be more prone to substance use or experience greater difficulty regulating consumption [Reference Smith, Mattick, Jamadar and Iredale81–Reference Latvala, Kuja-Halkola, D’Onofrio, Larsson and Lichtenstein84]. Thus, the observed associations may reflect bidirectional or predisposing effects rather than direct consequences of use. Longitudinal and preclinical studies are needed to clarify the temporal sequence and causal pathways underlying these relationships.

Strengths and limitations

Limitations include, first, the cross-sectional design of the analyses, which does not allow for causal or temporal inferences. Second, we observed mostly small effect sizes for the associations between substance use and cognitive functions, which was expected given the recreational use patterns in this community-based cohort. However, it is important to note that participants’ educational level explained a substantial proportion of the variance in cognitive performance (see, e.g., [Reference Rovio, Pahkala, Nevalainen, Juonala, Salo and Hutrikähönen46]). Third, the cognitive test battery used in the present study was not exhaustive due to strict time constraints aimed at limiting participant burden, meaning that functions such as processing speed, executive functions, and decision-making – domains shown to be affected in substance-using populations [Reference Verdejo-Garcia, Garcia-Fernandez and Dom85] – could not be assessed.

Finally, a major strength of our study is the objective assessment of substance use through hair testing, which is particularly important given the high rates of underreporting of illegal substances, such as cocaine [Reference Steinhoff, Shanahan, Bechtiger, Zimmermann, Ribeaud and Eisner42]. Additionally, selection bias was minimal, as the original sample was community-representative [Reference Ribeaud, Murray, Shanahan, Shanahan and Eisner61].

Conclusion

Our results indicate high prevalence rates of substance use among young adults and lower cognitive performance associated with predominantly occasional and recreational use of substances such as cannabis, cocaine, codeine, MDMA, and ketamine, as well as polysubstance use. On the one hand, the high prevalence of substance use in this population likely increases the risk of functional impairments [Reference Shanahan, Steinhoff, Bechtiger, Copeland, Ribeaud and Eisner86, Reference Hill, Blanco, Hasin, Wall, Flórez-Salamanca and Hoertel87], reduced well-being [Reference Nutt, King, Saulsbury and Blakemore56, Reference Degenhardt and Hall75], and the development of substance use disorders later in life [Reference McCabe, Schulenberg, Schepis, McCabe and Veliz88, Reference Jordan and Andersen89]. On the other hand, the immediate consequences of cognitive dysfunction due to recreational substance use may include impaired driving ability [Reference Dahlgren, Sagar, Smith, Lambros, Kuppe and Gruber90], diminished educational or occupational performance, or an increased risk of serious falls, even among younger individuals using opioids [Reference Hopkins, Bharat, Buizen, Close, Ivers and Draper91]. Our findings should be considered in the context of recent discussions about the legalization of substances such as cannabis, providing important evidence to inform drug policy (e.g., [Reference Csete, Kamarulzaman, Kazatchkine, Altice, Balicki and Buxton58]). However, further research using longitudinal designs and advanced methods is needed to establish the directionality of these effects and account for additional potential covariates.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2026.10156.

Data availability statement

Anonymized data, protocols, or other material from earlier project data collections are generally available to the scientific community upon request from author DR (denis.ribeaud@jacobscenter.uzh.ch).

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all participants, field managers, and the toxicology laboratory team for their invaluable contributions to the study’s success.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: L.E., C.J., L.S., B.B.Q.; Methodology: L.E., C.J., L.S., B.B.Q.; Formal analysis: L.E.; Investigation: D.R., M.E., L.S., B.B.Q.; Data curation: L.E., C.J., L.J.F., D.R., M.R.B., T.M.B.; Writing – original draft: L.E.; Writing – review & editing: L.E., C.J., L.J.F., M.R.B., T.M.B., D.R., M.E., L.S., B.B.Q.; Visualization: L.E.; Supervision: C.J., L.S., B.B.Q.; Project administration: L.S., B.B.Q.; Funding acquisition: D.R., M.E., L.S., B.B.Q.

Financial support

This study was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant #10531C_189008 awarded to LS and grant #10F114_170402 to BQ. The research reported in this manuscript has also been financially supported by the SNSF as a research infrastructure (grant #10FI14_170402 awarded to Michael Shanahan; grant #10FI14_198052 awarded to DR and LS), by the Jacobs Center (JC), and by the Jacobs Foundation (JF). The Zurich Project on Social Development from Childhood to Adulthood is a long-term study initially set up by MPE and DR. Earlier phases of the study (2003–2016) were funded by the SNSF, the JF, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, the Department of Education of the Canton of Zurich, the Swiss State Secretariat of Migration and its predecessors, the Julius Bar Foundation, and the Visana Plus Foundation. Funding was received for independent fundamental research.

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethics statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Cantonal Ethics Committee Zurich [BASEC #2017–02021] and the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Zurich.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.