Flash forward

When Eusapia Palladino arrived in the United States in late 1909, she was already a diva. She was not, however, what the Americans had imagined she would be. “Many have passed Eusapia Palladino in the streets of New York without being impressed by her. She seems at first a middle-aged woman … without much concern in life except to be comfortable. She would never be selected as a Witch of Endor. Her form is stout and short” (The Inter Ocean 1909). Above all, Palladino was completely unable to utter a word in English. Yet she had succeeded, over the previous twenty years, in convincing many internationally celebrated scientists, even Cesare Lombroso, the most famous of the Italian positivists, that she was one of the most powerful mediums in the world.

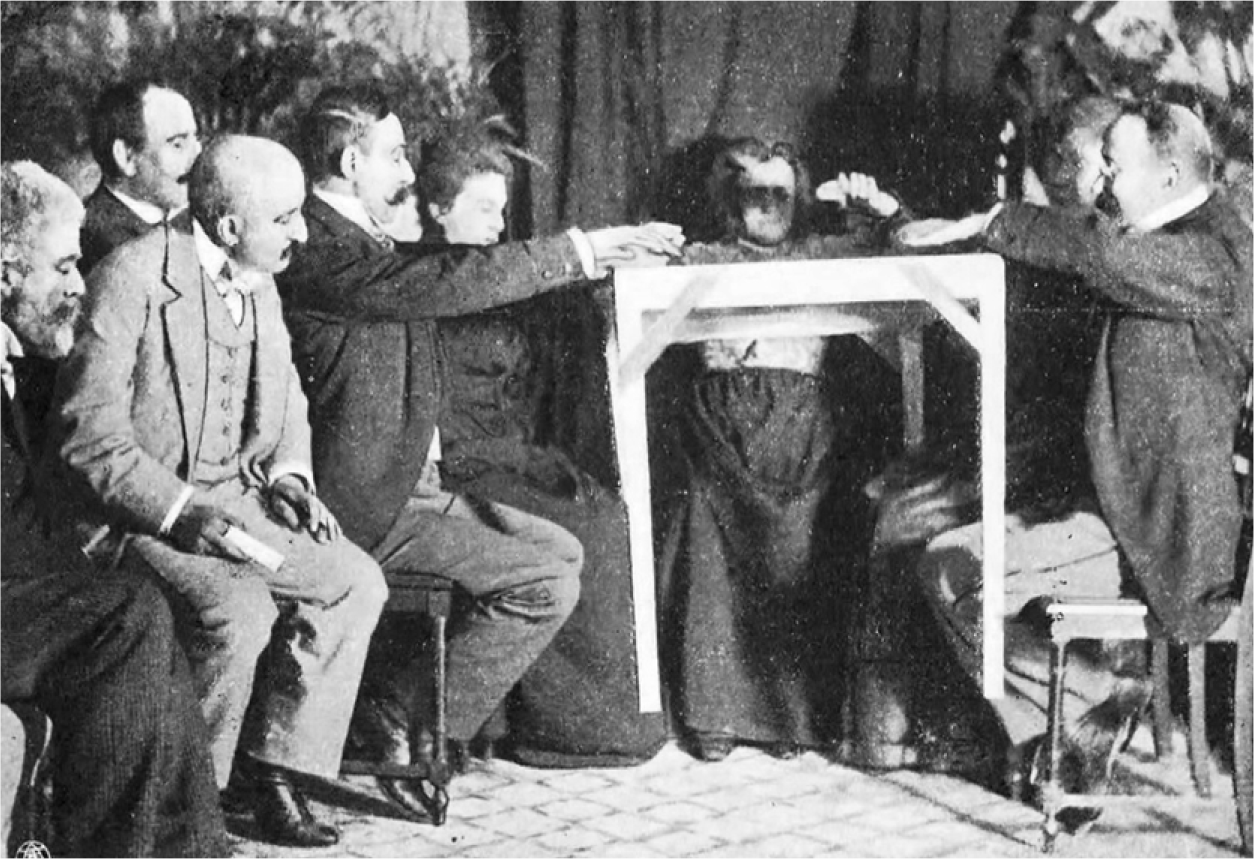

Palladino had been brought to the United States by Hereward Carrington, a pseudonym of Hubert Lavington, an amateur magician, who after observing her in Naples in 1908 on behalf of the Society for Psychical Research, had become her manager. Carrington had gone to great pains to prepare Palladino’s American tour: he had used the press to introduce the woman to the general public and to build anticipation (Kurtz Reference Kurtz and Kurtz1985, 204; Alvarado Reference Alvarado2011, 91-92). The newspapers had magnified the prodigious capacity of the Italian woman with exotic charm; they described her success in Europe and told the story of her poignant past (whether it was true or not), which made her seem like the protagonist of a novel: the premature death of her parents, the risk of ending up in a convent, the period spent as a maid, the discovery of her psychic abilities, and the first stages of her career. Cleverly engineered by Carrington, everything about Palladino’s arrival took on a sensational tone: from “leaked” rumors about the sessions she held aboard the ship Princess Irene, to the presence of many journalists who came to the press conference organized upon her arrival on American soil, to the public demonstration of the woman’s mediumship on the stage of Lincoln Square Theater (Natale Reference Natale2016, 98-99). But, just like those who had preceded him in the complicated role of the medium’s impresario (Kurtz Reference Kurtz and Kurtz1985, 204), Carrington knew that to persuade everyone he would first have to convince the very select audience of the scientific world. Hence, even in the United States, Eusapia Palladino had to undergo the certification process that in Europe had made her the “diva of scientists” (Alvarado Reference Alvarado1993; Blondel Reference Blondel, Bensaude-Vincent and Blondel2002; Evrard Reference Evrard2010) (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Snapshot of the “levitation” of the table during the meeting held on 31 May 31 1901 (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, tab. III).

The tantalizing first objective on American soil was to convince Hugo Münsterberg, director of the laboratory of experimental psychology at Harvard. Like his mentor Wilhelm Wundt, he had declared himself adverse to psychic research. However, unlike Wundt, Münsterberg had never sat at a medium’s table before (Münsterberg Reference Münsterberg1899, 78; Sommer Reference Sommer2012, Reference Sommer2013). Nevertheless, aware of the effect that the unmasking of Eusapia Palladino would have, he had consented to do so (Dennis Reference Dennis2002; Sommer Reference Sommer2012), saying to himself, “Madame Palladino is your best case. She is the one woman who has convinced some world-famous men. I never was afraid of ghosts; let them come!” (Münsterberg Reference Münsterberg1910a, 560; Reference Münsterberg1910b, 120).

Therefore, on 15 November 1909, the New York Times announced on the front page that Münsterberg had accepted Carrington’s invitation to be part of a scientific committee that investigated the Eusapia phenomenon.Footnote 2 It took just two sessions, on 13 and 18 December, to loudly shatter the plans of those who were already anticipating her conquest of America. At 23:44 on 18 December, Palladino let forth a scream that froze the blood of the participants (Carrington Reference Carrington1957, 113; Sommer Reference Sommer2012).

What had happened? Neither the medium nor Mr. Carrington had the slightest idea that a man was lying flat on the floor and had succeeded in slipping noiselessly like a snail below the curtain into the cabinet. I had told him that I expected wires stretched out from her body and he looked out for them. What a surprise when he saw that she had simply freed her foot from her shoe and with an athletic backward movement of the leg was reaching out and fishing with her toes for the guitar and the table in the cabinet! (Münsterberg Reference Münsterberg1910a, 571; Reference Münsterberg1910b, 142-143)

The Carrington-Palladino couple had been dealt a harsh blow. It would not, however, be the only one.Footnote 3 Something very similar happened soon after, during a second series of séances organized at Columbia University. Following these, the commission published, in the 20 May 1910 issue of Science, an article stating that, even in the dialectic of differing opinions, “no convincing evidence whatever of such a phenomenon could be obtained” and that, conversely, “many indications were obtained … that trickery was being practiced on the sitters” (Wood, Miller, Hallock Reference Wood, Miller and William1910, 776).Footnote 4 Eusapia Palladino was a fraud. Moreover, she had already been accused of fraud many times in her long career. She was, therefore, a charlatan: end of the story.

However, the story of the Eusapia Palladino phenomenon should not be dismissed so easily. First of all, for example, it is worth asking how this woman was able to emerge and to assert herself alone in the ruthless market of the mediums who performed in Europe at the time? Moreover, how was she, an illiterate maid, able to come into contact with a world so traditionally masculine as that of science in general, and the university in particular, to the point of duping the most beautiful minds on the continent? How can we think, then, that the scientists who participated in her sessions were so naive as not to identify tricks, which in some cases were not even particularly sophisticated? Above all, why, after being exposed several times, was Palladino repeatedly invited by other men of science who wished to organize sessions to ascertain whether something had not escaped their predecessors’ attention? (Lodge Reference Lodge1894; Ochorowicz Reference Ochorowicz1896; Feilding, Baggally and Carrington Reference Carrington1909).

It is clear that the question is more complex than the article published in Science would suggest. From a historical point of view, in fact, the problem is not so much whether Palladino cheated or not, but how her alleged powers, and she herself, could, at a certain point, become an “epistemic object” (Rheinberger Reference Rheinberger1997, 28) discussed by some significant representatives of the scientific community of the time (Blondel Reference Blondel, Bensaude-Vincent and Blondel2002, 146-147; Leporiere Reference Leporiere2016b, 331). Eusapia Palladino is often described as the “queen of physical mediumship” (Sommer Reference Sommer2012, 26), but her career was bumpy, and the outcome of a complex system of relationships, collaborations, entrepreneurial and cultural choices. This is why we will try to reconstruct the first phases, almost completely unknown prior to now: her childhood, her transfer to Naples, her first attempts to catch the attention of a greater audience than that of the city, her decline and, finally, her international revival thanks to a patron who guaranteed her the support of the man who was perhaps the most famous Italian scientist in the world at that time. The history of Palladino’s affirmation can thus constitute a window through which to look at the complex relationships between science and occultism, in particular spiritualism, between the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth.

A star is born

Eusapia Palladino had not always been a queen. On the contrary, she was born into a humble peasant family, in Minervino Murge, Puglia, on 21 January 1854. That is almost everything we know with certainty about the first few years of her life. The rest is wrapped in a thick fog of confused, dubious, and sometimes contradictory information. This is also because, once she became famous, Palladino began to embellish her autobiographical stories. Perhaps her stories were not out-and-out lies, but rather attempts to render more interesting and adventurous a childhood which, she must have thought, was poorly suited to the image of the great medium that the spiritualists were creating for her. In doing so, she would not have behaved differently from other public operators – such as charlatans, acrobats, and hucksters – capable of interacting with various types of publics, modifying their performances and the narratives of their histories as required (Porter Reference Porter, Burke and Porter1987, Reference Porter[1989] 2000; Ramsey Reference Ramsey1988; Podgorny Reference Podgorny2015). As Irina Podgorny explains, “the charlatan speaks to us of one of the characteristics of knowledge: the concept of wandering. However, since charlatans do not write, or they do so infrequently, the imprints of their itineraries have overlapped and cancelled each other out” (Podgorny Reference Podgorny2012, 13).

Palladino’s stories thus tended to be different at each telling. What remained constant was the dark and tragic background of the various versions. She claimed to have been orphaned at a young age: her mother Irene was said to have died giving birth to her, and her father Michele to have been killed shortly thereafter, before the helpless eyes of his daughter, by the gang of the famous brigand Carmine Crocco (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 118; Courtier Reference Courtier1908, 479). This would explain the epithet “daughter of fear” that was applied to Palladino by her biographers (Alippi Reference Alippi1962, 127).

Was it all true? Upon looking for confirmation of these stories in the archives, significant discrepancies emerge. The data reported in the certificates of birth, baptism, and extreme unction kept at the State Archives of Bari (Trani section) and the Capitular Archives of Minervino Murge do, in fact, suggest that Palladino’s mother died only seven years after giving birth to her. Footnote 5 This was probably due to complications related to childbirth - not Eusapia’s, but that of another child, Savino, who died shortly thereafter (de Ceglia and Leporiere Reference de Ceglia and Lorenzo2018, 44-45). Of course, there remains some discrepancy between the dates on the documents, and there might be cases of homonymy, but if this hypothesis is correct, Palladino, in recounting the incident, seems to have carved out a more consistent role for herself as the tragic protagonist, “daughter of death,” in an episode that was certainly dramatic, but in which she played only a secondary role.

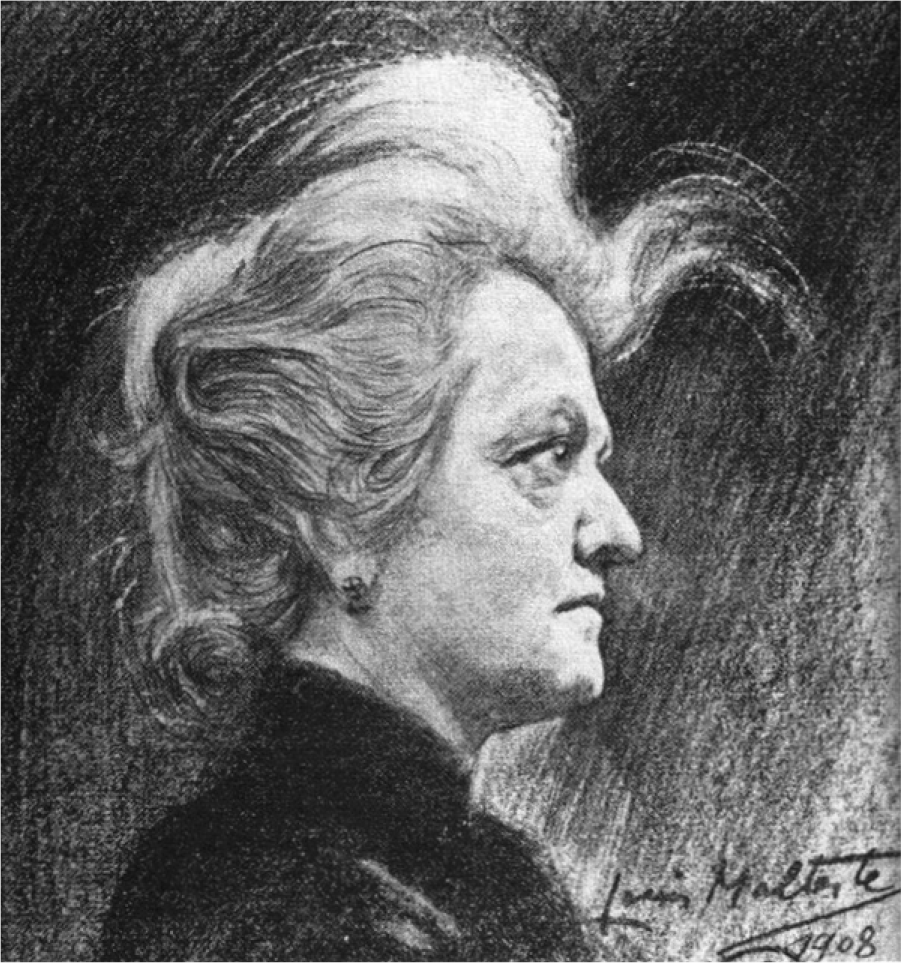

After the tragic event, as Palladino recounted, her father had sent her to be brought up on a farm in the countryside by caring people who, when she had not yet completed a year of life, had dropped her on the ground. Thus, she had a cranial lesion which, when years later she would fall into a trance, released an icy wind, clearly perceived on several occasions by the participants in the sessions (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1907, 392). At other times, Palladino is believed to have said that she had gotten the lesion between the ages of eight and nine, when, falling prey to typhus delusions, she had fallen out of bed (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 118). These two versions are also an evident attempt to identify some narrative to account for an anatomical detail about which scientists had wondered at length. On the scar, or in its immediate vicinity, a strand of white hair soon grew. In portraits of Eusapia Palladino it was valued almost as a “hyper-visible” signal of the anatomical-mediumistic peculiarity of the woman. In the culture of the Europe of the belle époque it seemed like a secularized version of what had once been the “witches’ mark,” and gave the medium her own unique visual identity that distinguished her from her competitors (fig. 2).

Figure 2. Portrait of Palladino by the French illustrator Louis Malteste, dated 1908.

It is difficult to express an opinion regarding the violent death of Palladino’s father, which cannot be found in the chronicles of the time. However, Enrico Carreras, one of the few to have ventured into the difficult task of shedding light on these early years, reports an interesting story that was told immediately after the death of the medium by some of the villagers who had known her as a young woman. According to the story, at the age of twelve Palladino left her parents to join a group of traveling jugglers. It was said that both parents were still alive (whereas, instead, if the results in the archive prove correct, at least the mother had to be dead at the time). So, in a partial, after the fact, reconstruction of her tragedy, she is said to have run away. The following year she is then thought to have become a servant at the home of a doctor in the nearby town of Venosa, and there she would discover her own mediumistic gifts (Carreras Reference Carreras1918, 134).

There is no certainty about this either: even in the different versions, Palladino said that in the end some family friends had taken her to Naples. It seems she was already there in 1871. In what, until a decade earlier, had been the capital of a real kingdom, she is said to have stayed, probably working as a servant, in two or three houses: which leads one to think that she had a less than idyllic relationship with her employers. The mature Eusapia Palladino would later say that she ran away from those who wanted to teach her to read and write, to wash and to comb her hair. Perhaps it is true, but it can be assumed that she was sent away for being sloppy or for insubordination. Indeed, she was a very independent and lively adolescent. As far as we know, she finally found employment at the home of a postman, a certain Mr. Migaldi. And it was there that, apparently, she met the person who would revolutionize her life.

The Pygmalion and the illiterate woman

On 16 October 1913, at the Hofburg Theater in Vienna, the famous play, Pygmalion, written by George Bernard Shaw, was performed for the first time. Amid uproarious laughter, and some indignation, the audience watched the German adaptation of the story of Professor Higgins who bets he can transform the crude flower girl Eliza into a sophisticated duchess. Forty years earlier, in Naples, the young Eusapia Palladino was preparing to undergo a similar metamorphosis, which would transform a humble maid into the “queen of the cabinet” (Polidoro Reference Polidoro2009, 30). The Pygmalion in her story was Giovanni Damiani, a gentleman originally from Palermo, but Neapolitan by adoption, who had lived in England for some time (Peebles Reference Peebles and Damiani1880, 3-6). Why did he choose her of all people?

Damiani, at first a fervent Catholic, then a rationalist and even a “Comtist,” as he himself put it, had begun to approach spiritualism after participating, in 1865, in a séance with Mary Marshall, “the first professional English medium” (Fodor Reference Fodor1934), who, a few months later, would help to introduce even Alfred Russel Wallace to spiritualism (Wallace Reference Wallace1875, 128), and a few years later, William Crookes (Doyle Reference Doyle1926, vol. 1, 239). During her stay in Clifton, the woman had made it possible for Damiani to contact the spirit of his deceased sister, of whose existence, later confirmed by his elderly mother, he knew nothing (Damiani Reference Damiani1869, Reference Damiani1871). The story, true or not, would be used by Damiani as an extraordinary instrument of persuasion as to the veracity of the revelations of spirits, of which he became a strong supporter, so much so that he proposed to wager a thousand guineas on the topic against the Irish physicist John Tyndall and the English philosopher George Henry Lewes, who had expressed their opposition to spiritualism (Damiani Reference Damiani1868). Damiani, who may well have harbored some cultural ambitions, with this striking gesture wanted to drag two illustrious names of culture into the arena, in this way entering a debate on spiritualism that looked promising. But the two did not accept the bet, which, moreover, was ridiculed by some newspapers. Nevertheless, Damiani did not abandon his project, and sought the support of the anti-clerical and Masonic forces that came together in the so-called anti-council, an event that was held in 1869 in Naples in opposition to the First Vatican Council (Peebles Reference Peebles and Damiani1880, 10-12). Meanwhile Damiani travelled through England, France, and Italy, participating in séances with more than 100 mediums, only three of whom operated professionally or, in any case, for money (Damiani Reference Damiani1869). It was in that context that he encountered the spirit of John King.

Who was this John King? In spiritualist circles there was a legend that John King had lived, between 1635 and 1688, in the body of the Welsh Buccaneer Henry Owen Morgan, admiral, pirate, and governor of Jamaica (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 2, 62; Doyle Reference Doyle1926, vol. 1, 32, 247). His name was often associated with that of his daughter Katie, called Annie while she was alive (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 2, 250). In 1866-67 they were together in Marshall’s home, where they conducted vocal demonstrations. In truth, the King family was far more numerous, as recalled by the Italian psychiatrist Enrico Morselli in his monumental monograph on the relationship between psychology and spiritualism. It was in fact a clan of 165 spirits, who had appeared for the first time in the séances of two Jewish American mediums who soon migrated to Europe (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 22, vol. 2, 449; Bozzano Reference Bozzano1932). However, the father and daughter pair were the first to be far more active on the international mediumship scene. Katie’s name would, in fact, remain essentially linked to the séances held between 1871 and 1874 by the medium Florence Cook, who the scientist William Crookes strongly supported, and who was repeatedly photographed arm in arm with the spirit (Chéroux, Apraxine and Fischer Reference Chéroux, Pierre and Andreas2005; Raia-Grean Reference Raia-Grean, Kang and Woodson-Boulton2008).

It seems it was thanks to an indication from John – or Gion (the Italianized form that appears on the back of some photos sent years later by Eugenio Gellona to Cesare Lombroso) – that Damiani was able to meet Palladino, who, at the time, was serving in the house of the Migaldi family (Carreras Reference Carreras1918, 134), effectively sanctioning a continuity between Palladino and the great spiritualists and mediums who had preceded her. Belonging to a group, according to an ideal tradition, was fundamental to finding one’s own place and visibility in the mediumistic panorama.

Damiani’s first contact with Palladino, it is said, was through another woman.

At Naples an English lady who had become the [second] wife of Signor Damiani was told at a table séance by a spirit, giving the name of John King, to seek out a woman named Eusapia, the street and the number of the house being specified. He said she was a powerful medium through whom he intended to manifest. Madame Damiani went to the address indicated and found Eusapia Palladino, of whom she had not previously heard. The two women held a séance and John King controlled the medium, whose guide or control he continued ever after to be. (Doyle Reference Doyle1926, vol. 2, 3)

Again, the facts may not have happened exactly like this, given the non-impartiality of the source. As it was, when Palladino was approximately eighteen years old, she was able not only to cause raps, but also “mediumistically” to move and rearrange furniture, even including a piano (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 120-121). After having met her, Damiani quickly realized that he had in his hands a valid “argument” for reentering the international debate on spiritualism in a significant way. So it was that in 1872 he published an article in the British spiritualist journal Human Nature in which he announced that he had found in Naples, after much research, “a medium of most extraordinary and varied powers. Her name is Sapia Padalino” (Damiani Reference Damiani1872, 222). Yes, Sapia Padalino, an obvious distortion of the name Eusapia Palladino that, in this form or other similar ones – Sapo, for her first name, and Paladino, with a single “l,” for her surname – was often found in articles, especially in the early years.Footnote 6 Whilst it could have been a repeated typo, the persistence with which the variant appears (Damiani Reference Damiani1896) suggests rather that the woman, illiterate and away from her family, did not even know her name exactly, which would not be so unusual for the time. From this point of view, the story of the medium could be told as that of “becoming Eusapia” – of this woman’s evolution, guided by wise “protectors,” from Sapia Paladino, a humble woman, probably devoid of any form of self-awareness, into the international diva Eusapia Palladino.

In Damiani’s first article there was also another detail: in describing the qualities of this “seer, clairaudient and impressional medium,” he stated that “she is, however, far from being developed, and a few investigators sit with her three times a-week for the purpose of development” (Damiani Reference Damiani1872, 223). Once he had found the “chosen one” and had made the announcement to international spiritualist circles, Damiani, quite attentive to the philosophical-cultural dimension of spiritualism, needed to train her. Indeed, it was a common belief that even mediums had to be educated in order to learn the theory and perfect their practice. The Pygmalion’s task was, therefore, to provide his Neapolitan Eliza with the right conditions to grow. Young, inexperienced, accustomed to obedience (so Damiani thought), with no family ties, totally raw, but instinctively intelligent and, above all, able-bodied, Eusapia Palladino must have appeared to him to be the ideal candidate to become the “perfect medium” who would clearly prove the theory of the spirits (Chéroux, Apraxine and Fischer Reference Chéroux, Pierre and Andreas2005).

One has to ask what this “development” or, to quote Lombroso, “psychic breeding” consisted in (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1909a, 47). Some of the work served to correct the “peculiar and disagreeable bent of her mediumship,” which involved the disappearance of objects such as wallets, watches, and cloaks during séances. This fact was attributed to some mischievous “low spirits,” which in turn needed “educational development” (Damiani Reference Damiani1872, 223; on the nature of these spirits, see Damiani Reference Damiani1880, 110-111). In an anthropological reading of events, this actually reveals a certain habit – or at least willingness – of the medium for theft and, in any case, would confirm her dexterity. Damiani, who probably wanted to use Palladino as an “entry” into the most sophisticated spiritualistic circles (for which he was just a certain “Mr. Damiani”), was clearly annoyed by the fact. He therefore instituted a “moral growth” program and began, so to speak, to “clean up” the customs of his protégée. This allowed her to become a symbol of a spiritualism that he did not fail to present with an exotic Italian coloring. However, as Morselli explained, there was more to Damiani’s program than merely teaching Palladino “good manners”: “obviously, it was a striking action carried out day by day by the skillful and convinced spiritualist to direct the young girl’s mediumship towards pre-determined effects, to inculcate in her the explanatory hypotheses of communications with spirits, and, especially, to get her used to the techniques already in use in British spiritualistic circles” (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 121).

Damiani would, therefore, primarily influence Palladino, teaching her the fundamentals of the spiritualist doctrine. It is difficult to say what the unruly girl made of these teachings. Certainly she never managed to master that complex doctrinal framework that Damiani had adhered to by attending the English spiritualist circles: essentially the same one codified years before by the Frenchman Hippolyte Léon Denizard Rivail, better known under the pseudonym of Allan Kardec.Footnote 7 However, it seems plausible that, whatever her initial ideas about spirits and extraordinary powers had been, Palladino did end up believing in them seriously, at least in part. After all, at the time, especially in the culturally and economically weaker strata of society, almost everyone believed in external forces that acted upon the lives of men. This, among other things, would explain her otherwise incomprehensible reactions to certain episodes that happened to her. For example, when years later, she suffered a theft, she turned to a famous “somnambulist” to try to track down the perpetrators (Graus Reference Graus1907, 205).

What we can say with certainty is that Damiani trained Palladino, maybe even for four years, “with frequent exercises,” to operate in the setting of a séance (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 121-122). It is unknown how effective the work of the mentor was, but he had to have played an important role even in the medium’s choice to move temporarily to Rome to continue her education with the spiritualist Achille Tanfani (Tanfani Reference Tanfani1872). In fact, in the capital, “at meetings of the newly formed society of Roman spiritualism, a course of experimental sessions was started with Eusapia, which lasted eight months; during which time Eusapia, then an adolescent, was entrusted to the care of a reputable spiritualist, Mrs. Maddalena Cartoni” (Tanfani Reference Tanfani1918, 139, emphasis in original). One can surmise that there the young medium learned techniques that, while relatively widespread in the Roman environment (La Civiltà Cattolica 1881; cf. Tenerelli Reference Tenerelli2020, 29-47), were quite distant from the more composed idea of “British” spiritualism cultivated by Damiani. In fact, during those months strange and unpleasant events occurred: canaries hypnotized by the spirits and cats found dead after having disturbed the séance with their mewing, the materialization of dead rats and, especially, the disappearance of valuables. As far as is known, Damiani rebuked the low spirits that tormented Palladino and even went so far as to ask for suggestions from the readers of certain English spiritualist magazines, who suggested that he treat hers as the case of an obsessed or possessed woman, and also gave practical advice (The Spiritualist 1873).

The characterization of the medium thus revealed itself to be a question of “discernment of spirits,” as was said in theological terms (Caciola Reference Caciola2003). This was because, when someone revealed that he or she had come into contact with forces coming from another dimension, it was not so easy to understand the nature of these entities. From this point of view, the boundaries between good and evil have historically always been very uncertain and the result of negotiation - to the point that, even in the religious world, for example a nun who was initially presented as a “living saint” and had visions of angels and saints, could then, depending on how the narrative of her spiritual encounters were reworked by the ecclesiastical authorities, also be considered a simulator, a madwoman or possessed by demons (Jacobson Schutte Reference Jacobson Schutte2001). In this process of defining the nature of mystical experiences – real, simulated, pathological or diabolical – the confessor played a pivotal role. He was the first to collect the words of the “aspiring saint” in order to interpret them and eventually make them public, and to support them in official offices, undertaking a path of growth and strengthening these beliefs with the woman. But the confessor was also the one who, if he doubted the genuineness of those phenomena or the benevolent nature of the spiritual powers involved, censored, blunted, punished, and denounced the lost sheep. He was, in other words, the bridge that the women of the past – often confined to a convent and unable to access autonomous communication channels – had with the world. Damiani was, so to speak, the confessor of the aspiring secular and illiterate Saint Sapia, around whom some had started to smell the scent of sulfur (de Ceglia and Leporiere Reference de Ceglia and Lorenzo2018, 56-63).

This is probably why, thinking that the situation was getting out of hand, Damiani thought it best to return Palladino to Naples. And here the problems continued, because the woman seemed unable to free herself of those annoying presences – the predisposition that matured in Rome, one could say – so much so that she was even fired from the new job that she had obtained as a maid (Damiani Reference Damiani1896, 429). Damiani had failed as a Pygmalion: he had wanted to create a perfect tool through which to show the world the veracity of spiritualism, but instead had helped to shape a medium with disturbing phenomena and who, moreover, did not worry about making whatever she liked disappear (Damiani Reference Damiani1896, 429). Eusapia Palladino, still known as Sapia at this point, was unpresentable and he had to accept it. It was necessary to allow her to return to her old life.

Now Palladino was alone, a woman alone. Because, unlike male mediums, often autonomous managers of their careers (Owen Reference Owen1989), the performances of female mediums – like those of actresses of the era – according to the economic, cultural, and gender structures of Italy of the second half of the mid-nineteenth century, needed the figure of an impresario (Rosselli Reference Rosselli1984, 101-134; Simoncini Reference Simoncini2011), of a protector, strictly a man - an intermediary who would be able to promote a person who could not even write her own letters in those environments that count (and pay). Would Palladino be able to find someone else?

Unexpected complicities

At this point in Palladino’s career, it seemed that the prosperous and stimulating life that Damiani had let her dream of had vanished. Moreover, accounts of her life claim that “for a few years, since Eusapia was engaged to a young man who did not look well upon her relationships with strangers who seemed to exploit those mysterious faculties, her spiritual practices slowed down; from 1872 to 1886 she gave very few séances, and those were reserved for a few trusted friends” (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 122-123). It is not known whether Palladino’s almost total absence from the scene really depended on her boyfriend’s inclination, or on her own inability, after having already been accused of theft, to assert herself without a guide in Naples. There, although the doctrine of spiritualism still struggled to be taken seriously, there were many who, even among those belonging to the higher social classes, had begun to play that “society game” (Pappalardo [1910] Reference Pappalardo1922, 162; [1922] Reference Pappalardo1976, 136). What is certain is that Palladino continued to perform only occasionally.

Standing out among the séances in this period, otherwise destined to remain in oblivion, were a handful of sessions held at a time not better defined, presumably in the early 1880s. The young writer Carlo Petitti spoke of them in a letter sent to the comedy writer and journalist Roberto Bracco. It is the latter who was very lucid in explaining the game of “cooperation,” more or less openly declared, that was set up during a spiritual session:

In spiritualism there is the active part and there is the passive part. And then there is another part, which I would call: cooperative. The active part is entrusted to the medium. The passive part is entrusted to peaceful believers. The cooperative part is entrusted to faithful believers. The spiritual phenomenon is conceived, directed, organized, and produced by the medium. The faithful believers are unconscious accomplices. The peaceful believers are simple spectators, they are onlookers, and therefore they, too, cannot be excluded from unconscious complicity. In other words, the faithful believers are necessary, or almost necessary, accomplices, and the peaceful believers are unnecessary accomplices. (Bracco Reference Bracco1907, 59)

The medium produces, in a fraudulent manner, some mechanical phenomenon, which the convinced spiritualists elaborate, in good faith, in an interpretation, and hence a narration, conforming to their expectations. It is, therefore,

A complex of first-degree hallucinations. And I say “first degree” because the spiritualist really sees something, he really hears something, really touches something, for the simple reason that the medium materially produces something. Except that he, the spiritualist, feels, believes, thinks, claims to see, hear and touch much more than the medium produces…. The spiritualists are neither swindlers nor imbeciles; the spiritualists are the result of three facts: the deception of the medium, self-suggestion and hallucination. (Ibid., 72-73, 78)

Of course, Bracco’s words must be contextualized. He, an anti-spiritualist, had never made any secret of his skepticism (Iaccio Reference Iaccio1992, 262). His uncompromising zeal and passion for the coup de theater thus led him to denounce the spiritualistic system and those who, in his eyes, were its hidden apparatus. The “spiritualistic system,” to be exact, and not Palladino’s system, since, ça va sans dire, although the subject of Bracco’s discussion were the sessions of the Neapolitan medium, for him she was certainly not the only one who resorted to fraud, nor unique in being thus somehow “helped.” The cases of Daniel Dunglas Home, Henry Slade (McCabe Reference McCabe1920), Florence Cook (Hall Reference Hall1963; Gerloff, Reference Gerloff1965), Stanisława Tomzcyk, Rudi Schneider (Gregory Reference Gregory1977, Reference Gregory1985), Marthe Béraud (Evrard Reference Evrard2016, 174-182) and almost all others would seem to provide important confirmation of the interpretation suggested by Bracco.

Later, others would be accused of helping Palladino, this time for personal interests, to scam sitters (Zingaropoli Reference Zingaropoli1905, 202; Marzorati Reference Marzorati1905, 441; Davis Reference Davis1909; Kurtz Reference Kurtz and Kurtz1985, 209). Whether true or not, the insinuations would seem to refer to something very different from what Bracco denounces: these sitters were indeed “conscious accomplices in a scam,” not “unconscious accomplices due to suggestiveness.” Nevertheless, thus far there was cooperation with quite intuitive dynamics. What is surprising is the introduction of a third category of accomplices emerging from Petitti’s account to Bracco. He says:

I soon knew what was going on and I played the same game…. She, the medium, made efforts to give an ultramundane appearance to all her games, which, unfortunately, did not produce a strong impression. I understood, indeed, she and I understood each other, and then with no intent to offend those respectable people, without showing that I knew something, I began to cooperate, to help and push that poor medium, my only purpose being to laugh about the incident and proposing to myself every night to tell the truth to my friends. (Bracco Reference Bracco1907, 97-98)

What emerges from Petitti’s story is the figure of the “conscious accomplice in the prank,” namely the person who, while not believing in, or at least being skeptical of, spiritualism, cooperated more or less tacitly with the medium for the sole purpose of teasing the remaining sitters. What is interesting is the result of the prank, because these accomplices contributed, despite themselves, to spreading appreciation for Palladino, who, if for nothing else, must be recognized for her ability to identify and, in some kind of tacit negotiation, interact with those people who, independently of the intended purposes, could play along with her. So, says Petitti, thanks to him the mediumship phenomena became even more stunning from one evening to the next. Once, pretending it was the work of a spirit, he even found himself playing the guitar on the table and asking one of the other people present to sing. Another evening, taking advantage of the darkness, with the sulfur covering the matches he had brought with him, he wrote numbers on the table and some scribbles that were taken for Hebrew words. “After that I stopped,” concluded Petitti, “because causing people who I respected to lose their minds ended up becoming a bad thing to do” (Bracco Reference Bracco1907, 101).

Petitti’s case is not an isolated one: the theatrical dimension in which the sessions were held raised in many opponents of spiritualism or simple pranksters an irrepressible desire to cooperate with the medium, if only to prove to themselves that they were capable of producing apparently inexplicable phenomena. Or at least this is the version they gave. Following another reading, one could venture that, conditioned by the atmosphere and charisma of the “delusional primary,” they were induced to become “delusional secondaries” and to carry out actions that accredited the positions of their adversaries. It was as if that “illusion,” in the etymological sense of the term (from the Latin, in + ludere, at + play/mock), left no way out and obliged everyone to participate in the construction of the mediumship phenomenon. Having done so, the only thing left to them was to find a theoretical justification for why they were doing it. After all, William Benjamin Carpenter had been explaining for some time how “the continued concentration of the attention upon a certain idea gives it a dominant power, not only over the mind, but over the body; and the muscles become the involuntary instruments whereby it is carried into operation” (Carpenter Reference Carpenter1853, 547-549; Crabtree Reference Crabtree1993, 256).

Perhaps not all the actions of the sitters were completely conscious and there was on their part the temptation to “play at spiritualism,” to echo the model of the homo ludens (Huizinga 1939 [Reference Huizinga and Hull1949]), which seemed not to spare even men of science. For example, the psychiatrist Leonardo Bianchi, at the end of one of Palladino’s first sessions with Lombroso, admitted that he, purely as a joke, had taken advantage of the darkness to drop a trumpet from the table, passing off the fact as one of those wonderful phenomena that were so anticipated, but that were scarce that evening (Ciolfi Reference Ciolfi1891). But, if it was indeed the case that during the séances it was easy to fall into some altered state of consciousness that induced one to engage in behaviors for which one was not fully responsible, this could also have happened for the medium. It would therefore not make much sense to imagine a Manichaean juxtaposition between deceiver and deceived: all would have contributed, to a different extent, to the construction of the event or performance.

Palladino apparently welcomed these collaborations, whether she was aware of what they were or not, as long as they did not get in the way of her work. The price of doing so was suffering her anger, and the – at times violent - exclusion of those accomplices from the game. For example, the journalist Federigo Verdinois tells of a session during which a man, to make a joke, produced light and knocking phenomena, causing the laughter of the poet and novelist Gabriele D’Annunzio who had wanted to participate in the medium’s performance. This undermined the other sitters and Palladino herself, at which point, it is said, a dark “brute force” fell on the disturbers and knocked them to the ground (Verdinois Reference Verdinois1920, 253-255; Giglio Reference Giglio and Angelo2005, 146-147).

The patron and the burden of proof

Interaction with more or less occasional collaborators could have helped Palladino make her séances a bit more lively, but without a patron, someone with excellent financial resources who could do their best and invest in her, she would never have emerged. For about fifteen years, she continued to put on only rare performances, so much so that by the mid-1880s she had almost been forgotten (Biondi Reference Biondi1988, 99-100). In short, there was nothing left of that extraordinary medium of which the English magazines had spoken. The story could have ended here.

Instead, in 1885 Palladino married Raffaele Del Gaiso, a thirty-eight-year-old Neapolitan, of whom very little is known, almost certainly the same man as the boyfriend who had limited her sittings. Footnote 8 Though Palladino had always presented him as being somewhat against her activities as a medium (Schettini Reference Schettini2014), many people insinuated that the man was “an amateur theatrical artist, whose store she helped to manage and from whom undoubtedly she learned various conjuring tricks” (Liljencrants Reference Liljencrants1918, 39-40). Considering this last, oft-repeated version (Kurtz Reference Kurtz and Kurtz1985, 197; Carrington Reference Carrington1909, 19), it cannot be ruled out that Del Gaiso’s familiarity with theatrical tricks, probably even initially learned as a means of exposing the frauds of the medium (Carreras Reference Carreras1918, 135-136), could later have been useful tools with which to enrich Palladino’s repertoire, eventually leading her to perform again. Nevertheless, it was not Del Gaiso who made Palladino into a diva, but another man named Ercole Chiaia.

Chiaia, aged fifty at the time he and Palladino met, had had a lively life. With a university degree in medicine from the University of Naples, he had been in the military in various places, and, after having married a wealthy woman, he finally dedicated himself to commerce and industry (Biondi Reference Biondi1988, 123). It was then, in 1885, that he met Palladino, probably through the journalist Verdinois (Reference Verdinois1920, 274-278). In the past, Damiani, like an authentic Pygmalion, had, at least temporarily, brought the medium out of anonymity. He had given her preliminary training; he had introduced her to British spiritualists; he had shown her what her new life could have been. But he had had to give up the project because of Palladino’s lingering lapses in taste - or those of her spirits. Now Chiaia, like a true “patron,” declared himself ready to make available the goods and connections necessary for Palladino to become the diva des savants - on condition that she would abandon herself to him completely.Footnote 9 From this point of view, Chiaia closely resembles the early modern patrons investigated by scholars such as Mario Biagioli or Paula Findlen who, by publicly taking responsibility for a client, not only allowed that client to make enormous career progress, but also gave the science or the art that they cultivated a more solid position in the encyclopedia of the time (Biagioli Reference Biagioli1990; Findlen Reference Findlen1994). In short, it is clear that a patronage like that of Chiaia would have done Palladino good, and would also have benefited all of spiritualism.

Bracco says, indeed, of the woman: “she is a hired medium, seized by cavalier Chiaia, whose munificence is so great that even his kidnappings are a good and generous action” (Bracco Reference Bracco1907, 46). In turn, Bracco continues, Chiaia “asks only for the medium’s loyalty” (ibid.). Unlike Damiani, Chiaia was more interested in the concrete demonstrations of the medium than in cultural reflections (Zingaropoli [Reference Zingaropoli1908?], 90). He was also much more inclined than that intransigent Pygmalion to modulate its own narrative according to the taste of those who tried to ingratiate themselves. Eusapia Palladino thus became a “marvel to exhibit,” which Chiaia exhibited at his home or in the residence of notables in the city, a network which seemed to be created, or at least tightened, precisely because of those séances (so much so that Del Gaiso, who had seemed recalcitrant in previous years, might have changed his mind precisely because of Chiaia’s generosity).

Chiaia, in addition to continuing to work on the medium, decided to work even more on the public. Therefore, he sought to produce permanent evidence of what was said to have happened during the sessions. The fear that the phenomena were not real, but only the fruit of suggestion, obsessed many (Richet Reference Richet1880, Reference Richet1884; Janet Reference Janet1886a, Reference Janet1886b) and it would continue to do so for a long time (Morselli Reference Morselli1908). To overcome this possibility,

Chiaia made … use of sculptor’s clay, reduced to a paste so that it allowed the occult agents, the intelligent, dynamic, tangibilized entities to make face, hand, or footprints. Then, into the cavities thus obtained, fine liquid plaster was poured, which once solid created high reliefs, or whole shapes according to the nature of the cavities. (Cavalli [Reference Cavalli and Zingaropoli1908?], 141; cf. Gellona Reference Gellona1905, 508; Pappalardo [1910] Reference Pappalardo1922, 82)

The casts provided the proof that it was a “real effect, attesting to the real, objective, sensitive cause” (Cavalli [Reference Cavalli and Zingaropoli1908?], 142). They supplied what Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison would call “mechanical evidence” of those strange phenomena (Siegel Reference Siegel1980; Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison2013, 115-190), which were considered even more persuasive than the first spiritualist photographs of light columns or globes in correspondence with the mediums obtained in Naples, starting in 1875, thanks to Damiani (Pappalardo [1910] Reference Pappalardo1922, 162; [1922] Reference Pappalardo1976, 136; Biondi Reference Biondi1988, 107; Cundari Reference Cundari2012, 65). Obviously, this is what the medium’s supporters believed, and they even found a way to justify the often-obvious resemblance of the features impressed in the clay to those of Palladino (fig. 3) (Rochas [1896] Reference Rochas1906; Bozzano Reference Bozzano1909). But that is another story.

Figure 3: The comparison between one of the mysteriously obtained molds (Bozzano Reference Bozzano1903) and a picture of Palladino’s profile shows the evident resemblance of the two faces.

Chiaia thought he had a demonstratio ad oculos of those inexplicable materializations (Cavalli [Reference Cavalli and Zingaropoli1908?], 143) and was waiting for the opportunity to give Palladino the visibility she deserved. The Catholic Church was adopting an increasingly less open attitude towards spiritualism, even though it had not yet formally condemned it (Biondi Reference Biondi and Christopher2013). It was, therefore, necessary, as soon as possible, to find some highly “visible scientist,” to quote Rae Goodell, willing to express uncomfortable positions and to scientifically certify the genuineness of the Eusapian phenomena (Goodell Reference Goodell1977, 6-7).

The occasion was provided when Cesare Lombroso, perhaps the most famous Italian positivist scientist of the time, in the pages of the Roman weekly Fanfulla della Domenica, admitted, albeit perhaps rhetorically: “even now the academic world laughs at criminal anthropology, laughs at hypnotism, laughs at homeopathy; who knows if my friends and I who laugh at spiritualism are not mistaken” (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1888a). Thus, on 19 August 1888, Chiaia took the opportunity and replied with an open anonymous letter published in the same newspaper, inviting the famous professor to a séance with the “witch” so as to attest to the “seriousness of the marvellous phenomenon” and “investigate its mysterious causes” (Chiaia Reference Chiaia1888). The gauntlet had been thrown down.

Cleverly, Chiaia was silent about any reference to spirits and, speaking in Lombrosian terms, pathologized Palladino’s phenomena, presenting her as “infirm” and afflicted by a mysterious “disease” (cf. Natale Reference Natale2016, 97). Under pressure, Lombroso stated that he could accept, on the condition that the séance room was “as bright as day” (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1888b). After all, he argued, “if there is a force capable of overcoming the laws of gravity, it must be able to work as much in darkness as in light, and without light there is no security against deception” (ibid). But since Chiaia was not willing to accommodate such “puerile needs” (Chiaia Reference Chiaia1889, 51), the professor could easily decline the invitation, even when the medium was brought, as per his order, to Milan (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1888c; Chiaia Reference Chiaia1889, 51). Therefore, once again, nothing came of the challenge.

The scientist and international accreditation

In truth, things had not gone so badly. The challenge, although not immediately successful, intrigued many, leaving other (less famous) scientists the opportunity to take the place of the recalcitrant professor Lombroso (Graus Reference Graus2016). If they were able to shed light on the alleged powers of the medium, they could say they were successful in a venture that not even the great criminal anthropologist had felt up to facing. Moreover, the director of Psychische Studien, Alexandre Aksakof, a Russian Councillor of the State engaged in the defense of spiritualism, encouraged Chiaia to extend the invitation rejected by Lombroso to the famous physiologist Charles Robert Richet, with whom the Neapolitan eventually came into contact (Zingaropoli [Reference Zingaropoli1908?], 154). In short, the unaccepted challenge allowed the patron to engage in important international relations: it was then that Chiaia realized he could count on an international network that in a few years’ time would allow him to launch Palladino not only in Italy, as he credibly thought in 1888, but throughout Europe. Damiani had not benefited greatly from his wager, which, although very detailed, seemed completely abstract, so to say, on the principles of spiritualism, since he did not name a specific medium to be subjected to examination. Chiaia, on the contrary, called upon science to examine the phenomena of a woman with a specific name and surname (the right ones, now). He protected her and financed her. In a certain sense, Eusapia Palladino was “his” and those who wanted to study her had to go through him, so that he too, in turn, became a public figure.

Chiaia did not intend to change his first strategy and so the proposal was renewed a few years later, when Lombroso went to Naples for work. Unlike the first, the second came privately, with a simple letter delivered through the spiritualist Ernesto Ciolfi. Once again, the professor did not hesitate to dictate his conditions: that the press not be informed in advance and that he be allowed to examine the room before the sitting. The lighting clause had, therefore, been dropped, suggesting that the first time the scientist had been curbed more by the judgment of public opinion than by concerns about the experimental conditions (Zingaropoli [Reference Zingaropoli1908?], 85). So, finally, on the evening of 28 February 1891, Lombroso, along with the psychiatrist Augusto Tamburini and other skeptical alienists, sat next to Palladino for the first time (Ciolfi Reference Ciolfi1891; Graus Reference Graus2016). That night, it is told, Chiaia was not well and Ciolfi took his place, accompanying the medium to Hotel Genève in Naples. Therefore, it was Ciolfi, as is stated in the manuscript record of the facts of that night conserved at the Cesare Lombroso Museum of Criminal Anthropology of the University of Turin, who asked for the production of the famous raps and taps.Footnote 10 He was the one who calmed the participants during the first phenomena. He admonished a sitter because he went out of the circle and rebuked him again when he, hiding near Palladino and hearing a bell ringing in the air, lit a match to find the trick. Finally, on 2 March, Ciolfi did not fail to send a letter to Chiaia, which he later published, to give him a complete account of what had happened (Ciolfi Reference Ciolfi1891). This latter circumstance could suggest that Chiaia’s indisposition was not real, but only one way of not attending the session (if the phenomena had occurred, they could have been attributed to his collaboration). In any event, thanks to his absence, he had, through Ciolfi’s letter, an excuse to publish a report written by someone who, at least formally, was not one of the two parties involved.

Despite the limited number of phenomena produced that evening, Lombroso decided to postpone his departure from Naples so as to attend a second séance. On 2 March Palladino was again in his presence. Among the sitters there was also the aforementioned Leonardo Bianchi, who had already attended a séance by Palladino, remaining unsatisfied (Bracco Reference Bracco1907, 116-125). On the evening of 2 March, what left Lombroso thunderstruck was a phenomenon that happened not during but after the séance, when some of the participants had already left: in full light, a coffee table in the room moved closer to Palladino, who was still tied to the chair. It was probably this, more than any “objective” test provided by Chiaia, that convinced Lombroso, causing him to declare, “I am very ashamed and sorry to have fought with such persistence the possibility of so-called spiritualistic facts; I say the facts, because I am still contrary to the theory. But the facts exist and I am proud of being a slave to facts” (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1891). The man who was perhaps the most visible Italian scientist in the world at the time had, therefore, surrendered to favoring “the finding of fact” over every other scientific principle (Scarpelli Reference Scarpelli1993, 153).

This “conversion,” not to spiritualism but to a sort of mediumism, had consistency in Lombroso’s work: he had conducted research on altered states of consciousness, especially on hypnotism, and reached the conviction that thought was the “effect of a molecular movement of brain cells” (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1887, 37). If the psychic anomalies could be understood as the effect of a mutated orientation of these molecules, he argued, it was not impossible that a materialistic interpretation could also be offered for mediumship manifestations (Frigessi Reference Frigessi2003, 401; Galluzzi Reference Galluzzi and Montaldo2015, 228). As is known, Lombroso believed that subjects with asocial behaviors, such as “born criminals,” were true evolutionary fossils, in some way prehistoric human beings (Lombroso [1876] Reference Lombroso1889, vol. 1, 168-170). A few years before meeting Palladino, for instance, he had argued that phenomena such as telepathy were simply residues of an animal stage (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1887). And now the very presence of a lesion on Palladino’s skull seemed to provide him with an opportunity to return to talking about the somatic origin of some behaviors: it was Palladino’s anomalous body that accounted for her highly atypical attitude. Mediumship was not a wonderful gift, in Lombroso’s opinion, but the expression of a sui generis body.

Was Eusapia Palladino just a poor sick person? For Lombroso, perhaps yes, at least at the beginning. But the stakes were clearly much higher than the definition of the behaviors of a single medium. He had, for example, defined two ecstatics like Maria von Mörl and Louise Lateau as “hysterics” (Lombroso [1893] Reference Lombroso1903, 203). Atavism, degeneration and the pathologization of phenomena of transcendence in the broad sense were, in fact, the tools with which the science of late positivism was trying to carry out a reductio ad naturam of what the Church had up to that time considered miraculous or, alternatively, diabolical. Could the naturalization of Eusapian phenomena have been only a stage in the more ambitious project of the naturalization of the supernatural? “Who would have said in past centuries that the miracle,” observed an optimistic Enrico Morselli, “which has so many analogies with telepathy and psychic actions at a distance, would be destroyed forever by science?” (Morselli Reference Morselli1897, 45).

And if, instead of a fraud, it was the work of John King?

The plan, which lasted for years, had therefore succeeded: Chiaia, whose activity in Naples had lost momentum following a practical joke some years earlier (1886) by some skeptics who had made him evoke a non-existent spirit (Bracco Reference Bracco1907, 185-195), now aimed high, first gaining Lombroso’s support, then that of many other Italian and foreign scientists (Morelli [Reference Morelli and Zingaropoli1908?]). He had understood that it was not necessary to work on Palladino herself (perhaps because her “development” had already been undertaken by Damiani and, maybe, by Del Gaiso), but rather on those who could provide her with a scientific validation. And he thought that Lombroso was precisely the man to do so.

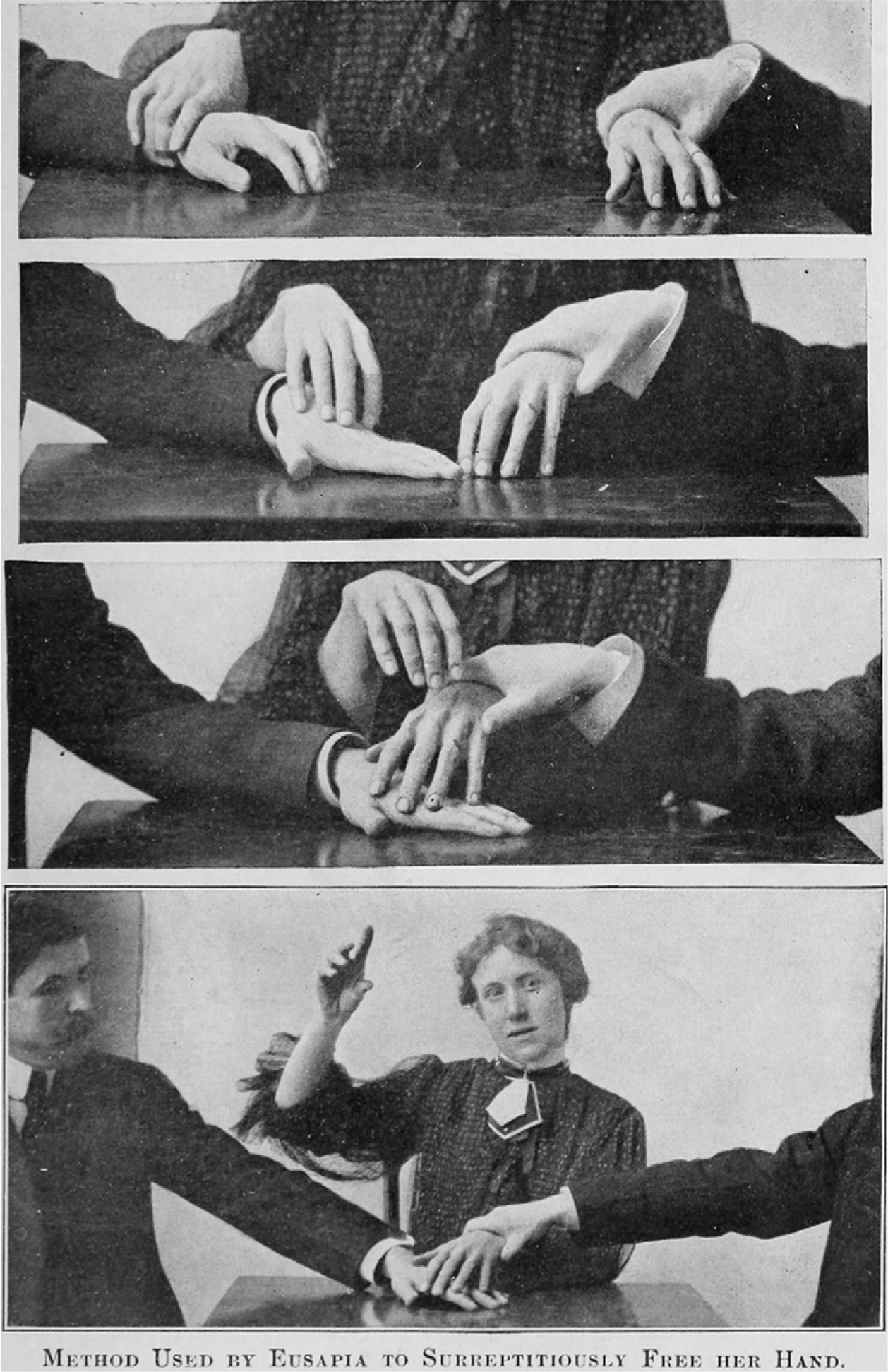

Admittedly, Lombroso’s fortunes had begun to decline, especially in Italy (Bulferetti Reference Bulferetti1975, 436-438; Frigessi Reference Frigessi2003, 406), and not everyone was convinced of his new theories. For example, for the French anthropologist and psychologist Gustave Le Bon, “from the time when he approached the study of spiritual phenomena, [Lombroso’s] science vanished and was replaced by infinite credulity” (Le Bon Reference Le Bon and Rossigneux1910, 3). However, for most people Lombroso remained Lombroso: and that is why the echo produced by his openness to those phenomena served as an extraordinary tool for promoting scientific research on spiritualism, or at least on mediumship. The phenomena produced by Palladino thus became the subject of spasmodic attention. From 1891 to 1898, their “evidence” was witnessed in numerous sessions in Paris, Cambridge, Rome, Munich, Warsaw, etc. involving physicians and psychologists, including Frederic William Henry Myers, Oliver Lodge, Charles Robert Richet, Albert de Rochas and Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, but also astronomers such as Camille Flammarion (Violi Reference Violi2012, 246). Of course, there was no lack of diametrically opposed opinions and even accusations of deception, even before the revelations of Hugo Münsterberg with which this article was opened, or the merciless verdict of “systematic fraud” pronounced in 1895 at Cambridge by members of the Society for Psychical Research. The latter, upon studying Palladino’s case, caught her cheating and believed they could say the last word on her phenomena (see the huge amount of materials in Cambridge University Library, SPR.MS 44/Eusapia Palladino Papers). In fact, Eugenio Torelli Viollier, director of the newspaper Corriere della Sera, had already revealed Palladino’s tricks in 1892 (Torelli Viollier Reference Torelli Viollier1892a, Reference Torelli Viollier1892b, Reference Torelli Viollier1892c) (fig. 4).

Figure 4. Illustrations showing how, according to Torelli Viollier, Palladino managed to free one of two hands from the grip of the inspectors (Flammarion Reference Flammarion1907).

Did all this force Chiaia to reconsider his plans? It would seem not. Or not by much. In the words of Mario Biagioli, “not only did patrons trigger disputes, but they often acted as arbiters in them…. Victories were better than defeats, but to trigger a challenge or have a champion challenge was already honorable to a patron …. It seems as if patrons … thought statistically. He would win the next. Therefore, what interested patrons was the ‘good sport’ displayed during the ‘duel’” (Biagioli Reference Biagioli1990, 30). This observation is convincing: but while it is understandable that Chiaia did not change his mind, why did scientists continue to give Palladino credit? Because, as Lombroso argued, the hypothesis of fraud was “the simplest explanation, most suited to the tastes of the majority and which spares us from thinking and studying” (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1892, 42). Many scientists did not deny that she sometimes resorted to tricks – especially when she was tired or had “performance anxiety” – but did not believe that this deception could explain all the complex phenomena that occurred during the séances (Aksakof, Schiaparelli and Du Prel [1892] Reference Aksakof, Giovanni and Carl1893; Lodge Reference Lodge1894; Aggazzotti, Foà and Herlitzka Reference Aggazzotti, Carlo and Amedeo1907; Courtier Reference Courtier1908; cf. Brancaccio Reference Brancaccio2014, 82). If there was fraud, commented the Polish psychologist Julian Ochorowicz, it was not conscious, because Palladino often fell into a trance during the séances (Ochorowicz Reference Ochorowicz1896, 97). Moreover, the scenarios opened up by recent studies on multiple personalities and altered states of consciousness seemed to guarantee plausibility for alternative explanations that the science of the new century could not afford to hastily dismiss (Gyimesi Reference Gyimesi2009). The hypothesis of fraud was, therefore, more complex than it appeared and had to be evaluated in a broader clinical picture - perhaps neuropathological (Lombroso Reference Lombroso1892, 146), physiological (Bottazzi [1909] Reference Bottazzi1996, 245) or schizophrenic - induced by autosuggestion.

For some, Palladino was not aware of herself during the séances. It is no coincidence that some called her a “sleepwalker” and imagined her to be in a trance while she let herself be “hypnotized” by the spirits. This terminological overlap emphasizes Adam Crabtree’s observation that “the histories of animal magnetism, hypnotism, and psychical research are inextricably intertwined” (Crabtree Reference Crabtree1988, XV). In fact, although when discussing magnetism and somnambulism, reference was usually made to an exchange of fluids of unspecified nature; in hypnotism, to an altered state of consciousness activated by some suggestive practice; in spiritualism, to the action of disembodied beings, in each of these cases there was always a subject who was “enraptured” in a special condition, in which it seemed that wonderful things could happen. The answer to the question of why this condition had happened, (i.e. the label that was attributed to what happened), was determined by the interpreters, schools, cultures, religions, languages and contexts involved. Just as there had once been confessors, there were now the lay patrons and doctors who intervened to establish the boundaries between the natural and the supernatural, the possible and the impossible. Delia Frigessi summarizes the point well, noting that “from hypnotism and spiritualism, from sleepwalking and suggestion, arise disturbing questions about human will and responsibility, free will, the powers of the psyche and the role of the unconscious. And the discussions around psychic phenomena … contribute to introducing a comparison between the sciences and philosophy, law, and theology” (Frigessi Reference Frigessi2003, 397-398).

Studies on multiple personalities were teaching the complexity of the human psyche and, according to some, they could have been the key to the interpretation of mediumistic phenomena. The Italian alienist Augusto Tamburini, who, with Lombroso, had attended Palladino’s famous Neapolitan sessions in 1891, was convinced of this. Unlike his illustrious colleague, Tamburini had not been so impressed by the physical phenomena he had witnessed. Therefore, he had diplomatically concluded that “without denying the possibility of the facts, the experiences in Naples did not give me a scientific demonstration” (Tamburini Reference Tamburini1892, 419-420). He decided to go back to experimenting with Palladino, but was fascinated by John King, whom the medium presented as her guiding spirit: what if this was the fruit of the split in the woman’s personality? At this point, for Tamburini the explanation of the phenomena was the following: the medium, truly convinced of the existence of spirits, self-suggested. Her conscious part therefore acted on the unconscious part, inducing in it the formation of a different personality, separate and ignored by the conscious one. The spirit evoked during the sessions, therefore, was no more than this new personality. John King was, in some way, a protective substitute for Palladino’s deceased father (Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 2, 254). And, like the Martians of the medium Catherine Élise Müller, aka Hélène Smith, (Flournoy [1911] Reference Flournoy1913), he had, therefore, a kind of reality, being the expression of another, profound personality of the medium. In both cases, as the scholar Roberto Giacomelli points out, “the trance … constituted the splitting between an infantile, archaic, grandiose and anarchic personality, and the adult one of the waking state: a real war, therefore, between the ego and the unconscious, during which the two women report being in the company of a parasitic personality who gives voice – it is evident – to their depths” (Giacomelli Reference Giacomelli2008, 317).

Tamburini’s explanatory hypothesis explicitly referred to the works of Michel Eugène Chevreul, but he also took inspiration from the most recent works by Charles Robert Richet, Pierre Janet and Alfred Binet. On the one hand, it showed the influence exerted on Italian alienists by the French psychopathological orientation (Ellenberger [1970] Reference Ellenberger1994, 403). On the other hand, the interest of psychology, even of German experimental psychology, in relation to so-called psychical phenomena (Plas Reference Plas2000), reinforced the belief that reducing everything to fraud alone meant not considering the complexity of the human psyche that science was demonstrating in those very years.

Would this pathologizing reading, therefore, be more credible than that proposed by those who claimed fraud? It is difficult to say, not least because neither excludes the possibility of other narratives, like the one in which Palladino was neither a scammer nor mentally ill, but a performer, indeed a real star (Nadis Reference Nadis2005; Natale Reference Natale2016). In that narrative, even those who helped her and were accused of being “conscious accomplices in fraud,” would appear as “managers” or simple staff members. Next to these, there would then be the narration of certain Catholic intellectuals, especially Jesuits, who perceived women like Palladino as possessed by demons, and accordingly saw their phenomena as spells and devilry, and their sitters as sinners (Franco Reference Franco1885).

What urgently needs to be highlighted here is not the unlikely primacy of one narrative over others, but the fact that, in the transition from one narrative to another, the language, priorities, objectives, argumentative strategies - and, above all, the responsibilities - changed. Even the weight and content of certain categories became noticeably different. This is why the tricks underlying some of the prodigious phenomena could at once be a point of obsessive interest for certain narratives (those we might call “investigative”), and almost completely irrelevant for others (such as the Catholic one, or the one we could call “play-theatrical”). Conversely, the category of sin, important to an eminently Catholic matrix, could be irrelevant to the pathologizing narrative.

A medium in the laboratory

As it was, once Lombroso had expressed himself on the topic of Eusapia Palladino, science felt called upon to try and understand something more. It was insinuated on many sides that the phenomena of the medium could depend on collective hallucinations (Ochorowicz Reference Ochorowicz1896, 109; Morselli Reference Morselli1908, vol. 1, 405; Bottazzi [1909] Reference Bottazzi1996, 108). Contributing to the spread of this fear was perhaps the debate triggered in Italy a few years earlier around the performances of stage magnetizers such as Donato or Pickman, the famous mind reader (Thornton Reference Thornton1976; Brancaccio Reference Brancaccio2017).

One way to rule out the possibility of hallucination was the casts obtained by Chiaia. But now it was necessary “to let the instruments speak and eliminate the human factors of fascination and disturbance” (Blondel Reference Blondel, Bensaude-Vincent and Blondel2002, 146). Achieving such an ambitious goal obviously required extensive preparation. It took years before Palladino accepted the idea of being studied in the laboratory. The first step, after the much talked about sitting with Lombroso, was to subject the prodigious phenomena to a committee. And so in 1892, thanks above all to the work of Alexandre Aksakof, a commission met in Milan, composed for the most part, in truth, by people who today we would hardly define as scientists: secondary school teachers (Angelo Brofferio and Giuseppe Gerosa), graduates in physics (Giovanni Battista Ermacora and Giorgio Finzi) and a philosopher (Carl du Prel). Highly respectable people, without a doubt, but, in some cases, already sympathizers of spiritualism. Nevertheless, Aksakof did succeed in making one “precious acquisition” for his commission by involving in the investigation the famous astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, Director of the Milan Observatory (Rivista di Studi Psichici 1903, 62), who until that moment had remained extraneous to spiritualism, but already suffered from severe vision problems and had no specific experimental skills in the field of psychical phenomena. Besides these people, Richet and Lombroso were also present at some of the séances.

As in the sessions of the previous year with Lombroso, once again complete control of the situation was not given to the improvised “investigators,” to the extent that, in a letter to his colleague Flammarion, Schiaparelli vented:

It must be admitted that these experiments have been made in a manner little calculated to convince impartial judges of their sincerity. Conditions were always imposed that hindered the right comprehension of what was really taking place. When we proposed modifications in the program suited to give to the experiments the stamp of clearness and to furnish evidence that was lacking, the medium invariably declared that, if we did so, the success of the séance would thereby be made impossible. In fine, we did not experiment in the true sense of the word: we were obliged to be content with observing that which occurred under the unfavourable circumstances imposed by the medium. (Flammarion, Reference Flammarion1907, 64)

At the end of the seventeen sessions, the commission, despite a thousand uncertainties, declared that no elements had emerged that would suggest fraud (conscious or unconscious) by the medium, or hallucination in the observers (Aksakof, Schiaparelli and du Prel [1892] Reference Aksakof, Giovanni and Carl1893, 63; Richet Reference Richet1893, 31). In fact, the two most credited hypotheses, fraud and hallucination, seemed to be no longer the only eligible ones (Richet Reference Richet1893, 31). Alongside these, new hypotheses were already being formulated, many of which also arose within those same investigative, play-theatrical or pathological narratives that we mentioned - hypotheses that sometimes clashed and sometimes combined with those that arose within other narratives, such as the Catholic and, of course, the spiritualist narratives. This is why a clear taxonomy is difficult and everyone could find confirmation of their ideas. This explains why the fact that this commission was open to the possibility that the mediumistic phenomena were real was touted by the spiritualists as a success or even a proof of spiritualism.

The outcome of this verdict may have depended, at least in part, on the rules of the game imposed by Chiaia. But it is also true that after his death, even when scientists were allowed to make more systematic observations on Palladino, they did not reach very different conclusions from those of the first commission. This was also the case when conjurers, perhaps more suitable than scientists to discover tricks, examined the medium. When, for example, in 1908 a group of investigators was sent to Naples by the Society for Psychical Research to shed light on Palladino’s phenomena, they were ultimately forced to admit that those phenomena could not exclusively be result of clever deceptions (Feilding, Baggally and Carrington Reference Carrington1909).

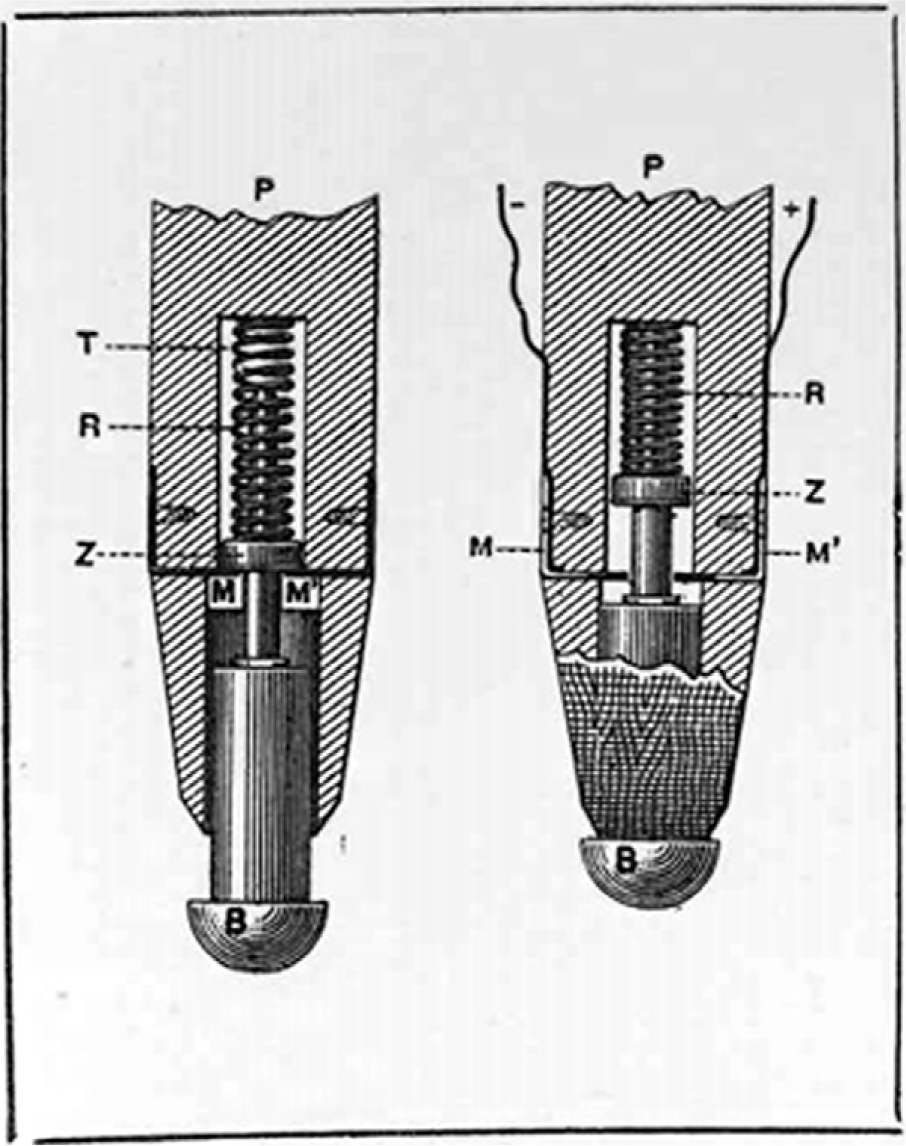

In contrast to these earlier examinations, the investigations that took place between 1905 and 1908 at the Institut Général Psychologique in Paris were very different. Here, at Richet’s suggestion, Palladino’s mediumship was subjected to investigations which led to far more rigorous evaluations. This was not only because high-profile scientists, including spouses Pierre and Marie Curie, were called to join the commission, but because selected measurement instruments were used, targeted tests were carried out, and graphic tracks were obtained, which were then critically discussed (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Electrical contacts placed under the feet of the seat table (Courtier Reference Courtier1908).

In the end a report was drafted. It was so thorough and detailed (Courtier Reference Courtier1908) that in 1913 it earned an award from the Académie des Sciences. Even in this case, however, the conclusion was far from definitive: Palladino had proved to be a “detestable” subject, had made rigorous controls impossible and had repeatedly been caught cheating. But the tricks noted were not enough to explain the totality of the observed phenomena. Further investigations were, therefore, deemed necessary (Evrard Reference Evrard2016, 245).

In the same period, similar research was also taking place in Italy. Palladino was first studied in Turin by three assistants of the physiologist Angelo Mosso, who used recording devices and some photographic plates that revealed, among other things, presumed radioactive phenomena (Aggazzotti, Foà and Herlitzka Reference Aggazzotti, Carlo and Amedeo1907). Further investigation was conducted in Naples, where the search for “scientific validation” seemed to have achieved a fundamental goal: here Filippo Bottazzi managed to bring the medium into his own physiology laboratory to study her, treating her, apparently, like any other subject of investigation. For the occasion, his colleague Richet would later acknowledge, Professor Bottazzi “surrounded himself, as in a classical physiological experience, with all the modern instrumental devices” (Richet Reference Richet1922, 638). Thanks to these devices, it was possible to obtain numerous tracks, proof of the authenticity – so it was supposed – of Palladino’s phenomena. Were they really proof? It is difficult to say. Clearly, however, all of those tools performed a more apparent and, so to speak, “rhetorical” function, and the conclusions reached by Bottazzi were hardly the outcome of an evaluation of those laboratory results (Leporiere Reference Leporiere2018, 113).

How, then, did Palladino’s phenomena occur? According to Bottazzi:

They occur as if created by the extension of natural limbs or by additional limbs that bud out of the medium’s body, and then they re-enter the body and disappear, after a variable amount of time, but in the meantime due to the sensations that they provoke in us, they appear as limbs in no fundamental way different from natural ones. (Bottazzi [1909] Reference Bottazzi1996, 249)

In short, after exhausting negotiations and tiring preparations, it was finally possible to bring Palladino into the laboratory to have her studied by professionals with appropriate tools. And yet, no definitive certainties had been achieved. Why was science so obsessed with Palladino and, in general, with phenomena referred to as “mediumistic”? Why did mediums become epistemic objects upon which only an investigation in the laboratory was deemed able to shed light?

Conclusions: The living scientific instruments

Bottazzi’s failure to obtain definitive scientific confirmation of Palladino’s phenomena in his laboratory was only the last, in a series of such failures. Ever since Lombroso had assumed the role, so to speak, of Palladino’s scientific guarantor, there had been attempts to authenticate her phenomena, but this goal was never achieved. This was a scientific authentication that, indeed, already many other mediums and spiritualists had also tried in vain to obtain (Pierssens Reference Pierssens, Bensaude-Vincent and Blondel2002, 41).

Spiritualist imagery had been intertwined with scientific and technological imagery since its origins. This connection is evident as early as 1848, when the Fox sisters of Hydesville declared that they could establish a communication with the spirits through “raps” (Evrard Reference Evrard2016, 61), making it possible, as Barbara Weisberg put it, for “eternity’s silence” to become “quite noisy” (Weisberg Reference Weisberg2004, 73). This type of interaction, called typtological (from the Greek typto, beat or strike), in establishing contact with the other world, evidently imitated the communication that wireless telegraphy had made possible from one part of this world to the other (Leporiere Reference Leporiere2016a). Only four years earlier, the first Morse code message had, in fact, been sent by Washington to Baltimore (Enns Reference Enns, Kontou and Willburn2012). The world of the occult and that of science and technology seemed to find in this similitude a first, important point of encounter. One of the first to underline the analogy between the two modes of communication seems to have been the Reverend Ashahel H. Jervis, a Methodist priest who had the opportunity to meet the Fox sisters right away (Weisberg Reference Weisberg2004, 102-103). He had called typtology the “Telegraph of God,” with all the enthusiasm of those who felt they had evidence to throw in the face of agnostics and infidels (Capron, Barrow Reference Capron and Barrow1850, 39). The similitude was, however, repeatedly taken up in the following years, among other things giving the name to the famous weekly Spiritual Telegraph, the first authentic spiritualistic magazine published for eight years in the United States, starting in 1852. In the end, there was also talk in similar terms in Europe, when, in the mid-fifties, spiritualism crossed the Atlantic. Allan Kardec made use of this image in his description of mediums’ “experimental” activity: