The home food environment is significantly associated with children’s dietary habits. In particular, sociocultural factors, such as parental intake and modelling, have been found to be consistently associated with food consumption among children(Reference Horst, Oenema and Ferreira1). Other sociocultural factors with the potential to considerably shape the home food environment are, for example, parenting styles and practices, rules, family eating patterns, parents’ food preparation skills and parental food preferences(Reference Rosenkranz and Dzewaltowski2,Reference Davison and Birch3) . Many of these factors can manifest themselves during family meals, making family meals important situations for a child’s food-related behaviours. Therefore, several studies have explored the associations between family meals and children’s food consumption(Reference Caldwell, Terhorst and Skidmore4–Reference Dugas, Brassard and Bélanger13).

Based on meta-analyses, a robust association seems to exist between frequent family meals and healthier diet among children and adolescents(Reference Dallacker, Hertwig and Mata14,Reference Robson, McCullough and Rex15) . Among preschool-aged children, a few, but not all, studies have reported associations between frequent family meals and higher fruit and vegetable consumption(Reference Caldwell, Terhorst and Skidmore4–Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann8) as well as lower sugar-sweetened beverage consumption(Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann8,Reference Rex, Kopetsky and Bodt9) . Perhaps most consistently, frequent family meals have been linked to higher nutritional quality(Reference Berge, Truesdale and Sherwood10–Reference Berge, Hazzard and Trofholz12), even though not all studies have confirmed the association(Reference Dugas, Brassard and Bélanger13). However, none of the studies published to date have reported results separately for weekdays and weekends, even though families in general have more opportunities for family meals during weekends. To identify the potentially most influential family meals during the week, studies separating meals and weekdays are needed.

Less is known about how family meals may impact food consumption in parents. Some evidence suggests a beneficial link, as associations between frequent family meals and higher fruit and vegetable(Reference Utter, Larson and Berge16) or lower energy-dense snack consumption among parents(Reference Rex, Kopetsky and Bodt9) have been reported. However, an association between family meals and dietary quality was not confirmed in a longitudinal setting(Reference Berge, Hazzard and Trofholz12). Most of the earlier studies have considered only or mostly mothers, and to the best of our knowledge, only one study has reported results separately for mothers and fathers(Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17). This US study found an association between family meals and higher fruit and vegetable consumption among both mothers and fathers, whereas an association between family meals and lower fast-food consumption was observed only among fathers(Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17). These results suggest that the relationship between family meals and parents’ food consumption may differ between mothers and fathers.

To summarise, studies suggest that family meals are associated with healthier diets both among children and parents. However, more research is needed to recognise which particular family meals are of importance and to explore whether the relationship between family meals and dietary quality differs between fathers and mothers. We aimed to fill this gap by examining the associations between family meals and dietary quality separately for children, fathers, and mothers. We hypothesised that more frequent family meals (parent-reported meals shared with the child) would be associated with higher dietary quality among children, fathers, and mothers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore these associations within the same study sample, allowing comparison between different meal types, weekdays and weekend days and fathers and mothers.

Methods

This study used cross-sectional data from the baseline assessment of the DAGIS (Increased Health and Wellbeing in Children, Families and Educational Settings) Intervention. This preschool-delivered, cluster-randomised controlled trial was conducted in Finnish preschools in 2017–2018 and aimed at improving energy balance-related behaviours (e.g. physical activity, screen time and healthy diet) in children(Reference Ray, Kaukonen and Lehto18,Reference Ray, Figuereido and Vepsäläinen19) . All the public preschools (n 29) in Salo and three public preschools in Riihimäki consented to participate, and altogether 1702 eligible children in the groups for 3–6-year-olds and their families were invited to take part in the study. In total, the guardians (later referred to as parents) of 801 children (47 % of the eligible children) gave consent to participate. Baseline data collection took place in September to October 2017 before preschools were randomised into intervention and control arms. A favourable statement was obtained from the University of Helsinki Ethical Review Board of the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences in May 2017 (22/2017). To ensure a sufficient sample size, power calculations were carried out prior to the recruitment for the DAGIS Intervention(Reference Ray, Figuereido and Vepsäläinen19). However, as this study reports secondary analyses, no a priori power calculations were conducted with regards to the variables used in the current analyses.

Family meal frequency

Both parents, should the child have two, were asked to fill in an electronic questionnaire assessing the frequency of family meals. The parents reported on how many weekdays during the past week they had shared (1) dinner and (2) an evening snack together with the child. Weekday breakfast, lunch and daytime snack were not considered because these meals are provided by preschools, and it is unlikely that these meals would be frequently shared within the sample of preschool-attending children. The response options for each meal ranged from 0 to 5, and the responses were dichotomised into ‘On 4 or 5 weekdays’ or ‘On less than 4 weekdays’. Similarly, the parents reported on how many weekend days during the past week they had shared a (1) breakfast, (2) lunch, (3) daytime snack, (4) dinner and (5) evening snack together with the child. For each meal, the response options ranged from 0 to 2, and the responses were dichotomised into ‘On 2 weekend days’ or ‘On less than 2 weekend days’. Analyses were stratified for meal type and weekday/weekend.

Dietary quality

One of the parents filled in a 51-item food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) regarding their child’s food consumption outside preschool hours. The FFQ was intentionally restricted to not cover foods provided by the preschools (breakfast, lunch and afternoon snack) because parents would not have been able to reliably report these foods. We sent a link to the electronic FFQ to all parents and hard copies to those who did not fill in the electronic version. Parents reported how many times during the past week the child had consumed the listed foods. They were instructed to either tick the ‘not at all’ box or to write a number either in the ‘times per week’ or ‘times per day’ column. The FFQ was based on a 47-item FFQ that was designed for the cross-sectional DAGIS survey, particularly aiming to assess the consumption frequencies of vegetables and fruits as well as sugary foods and beverages(Reference Korkalo, Vepsäläinen and Ray20). The original FFQ has shown acceptable relative validity in ranking food group consumption when compared with three-day food records(Reference Korkalo, Vepsäläinen and Ray20): regarding the items used in the current analyses, 60–96 % of the participants were classified into the same or adjacent quarters using the two methods. In a test-retest analysis, 14 items used in this study showed mostly moderate reproducibility, with intraclass correlation coefficients ranging from 0·1 to 0·7(Reference Määttä, Vepsäläinen and Lehto21).

Both parents, should the child have two, were also asked to fill in a 55-item FFQ regarding their own food consumption. The parental FFQ was identical to the child’s FFQ, with the exception that the parents had four additional items included: mild alcoholic drinks (e.g. beer, wine), strong alcoholic drinks (e.g. spirits), coffee and tea. The parents were asked to report all foods they had eaten during the past week.

We used the consumption frequencies of 30 FFQ items to calculate a 10-component Healthy Food Intake Index (HFII)(Reference Meinilä, Valkama and Koivusalo22) for children, fathers and mothers. Of the original 11-component HFII, we excluded three components (fast foods, cooking fat and fat spread), which were not assessed by the FFQ used in this study. To better comply with the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations and a revised version of the HFII(Reference Joutsi, Walsh and Lehto23), we included two new components, which were assessed by our FFQ: red and processed meat, as well as nuts and seeds. The components, food items included in each of them, and scoring criteria are presented in online Supplementary Table 1. The HFII was calculated for children, fathers and mothers by summing the component scores and ranged from 0 to 16, with a higher score implying better dietary quality. The original HFII has been shown to be able to rank participants according to their level of adherence to the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations’ food-based dietary guidelines among overweight and obese pregnant women or pregnant women with a history of gestational diabetes(Reference Meinilä, Valkama and Koivusalo22).

Sociodemographic factors

Sociodemographic variables previously identified as potential confounders(Reference Valdés, Rodríguez-Artalejo and Aguilar24,Reference Patrick and Nicklas25) were considered for the analyses and are presented in Table 1. One of the parents reported sociodemographic factors, such as birthdate and gender, for their child. Child age was calculated as the difference between baseline and birthdate and was used as a continuous variable in the analyses. The parent also reported their own and their spouse’s age and educational level. Educational level was recoded into three groups – low (comprehensive school, vocational school, or high school), middle (bachelor’s degree or similar), and high (master’s degree or licentiate/doctor) – and was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status. In addition, the parent reported the housing arrangements of the child and the number of children living in their household (one, two or three or more, all including the participating child). Housing arrangements were dichotomised into two groups: living with the father/mother (at least 50 % of the time, with or without the other parent or new spouse) or other (with the other parent and/or with other adults). As parents with shift work are likely to have less opportunities to share meals with their children, the parent-reported working time patterns were dichotomised into regular daytime work or not working and irregular working time patterns.

Table 1. Background characteristics of, and frequency of shared meals for participating fathers (n 103) and mothers (n 293) in the DAGIS intervention baseline (2017)

* The number of children is higher than the number of parents because multiple children from the same family could participate.

† Low = secondary school or lower, middle = bachelor’s degree or similar, high = master’s degree or higher.

‡ With or without the other parent or new spouse, at least 50 % of the time.

§ With the other parent and/or with other adults.

|| A meal shared with the child on 4–5 weekdays during the past week.

¶ A meal shared with the child on 2 weekend days during the past week.

Statistical methods

The analytic sample consisted of all parents and children who had FFQ data available for all the HFII components. To be included, the children also had to have at least one parent with sufficient data in the sample. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants in the study. We used Student’s t- and chi-square tests to compare the children included in the analytic sample with those excluded. The associations between the frequency of shared meals and HFII scores were examined using linear regression, separately for parent–child dyads and for parents. The models were adjusted for different confounders depending on whether the child’s or the parent’s dietary quality was examined. The adjusted models include child’s age and gender (parent–child dyads) and parent’s age and educational level (parents). The fully adjusted models also include parents’ age and educational level, as well as number of children living in the same household (parent–child dyads), and child’s age and gender, as well as number of children living in the same household (parents). Further adjustments for parental working time pattern (parent–child dyads and parents) and the parent providing food consumption data on behalf of the child (parent–child dyads) were considered, but the results remained unchanged (data not shown). Crude models are shown in online Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the associations between the frequency of shared meals with the presence of at least one parent (either father or mother) and the children’s HFII scores in a subset of families with complete data from the child, father and mother (data not shown). All analyses included all participants with data on the variables in question and were performed using version 3.6.3 of R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org).

Figure 1. A flow chart depicting the derivation of the analytic sample used in this study.

Results

The analytic sample consisted of 103 fathers, 293 mothers and 296 children. Of the children in the analytic sample, 52 (18 %) had two parents in the analytic sample, and mothers were the primary informants for their child’s food consumption, with 90 % (267) of the reporting parents being mothers. The children in the analytic sample were from higher-educated families than the excluded children (master’s degree or higher education 28 % v. 15 %, P < 0·001), but no differences were observed in terms of age or gender. Together, the participants formed a total of 88 father–child and 270 mother–child dyads. The children were on average 5·3 years old (sd 1·0), while the fathers’ mean age was 38·6 years (sd 6·2) and the mothers’ 36·0 years (sd 5·0). The most common educational level was bachelor’s degree or similar among both fathers (42 %) and mothers (50 %) (Table 1). About half of the families had two children, including the participating child, and most of the children lived with the parent at least 50 % of the time. Most parents had regular working hours. The most commonly shared meal was weekend dinner, which 76 % of fathers and 81 % of mothers had shared with the child twice during the past week. Other frequently shared meals were weekend lunch (69 % of the fathers, 77 % of the mothers), weekend breakfast (62 %, 77 %) and weekday dinner (56 %, 78 %).

The mean HFII score was 7·0 (sd 2·5) among the children, 6·5 (sd 2·7) among the fathers, and 7·7 (sd 2·4) among the mothers (range 0–16). Of the HFII components, the maximum score was most commonly achieved for fish (more than 75 % of all the participants), whereas less than 20 % received the maximum score for the high-fibre, red and processed meats, and nuts and seeds components, with the exception of mothers, of whom 32 % achieved the maximum score for nuts and seeds (online Supplementary Figure 1). Compared with fathers and children, a higher percentage of mothers received the maximum score for vegetables. For sugar-sweetened beverages, a lower percentage of children than parents received the maximum score, whereas for processed meats, the percentage of fathers achieving the maximum score was lower compared with mothers and children.

Children’s dietary quality

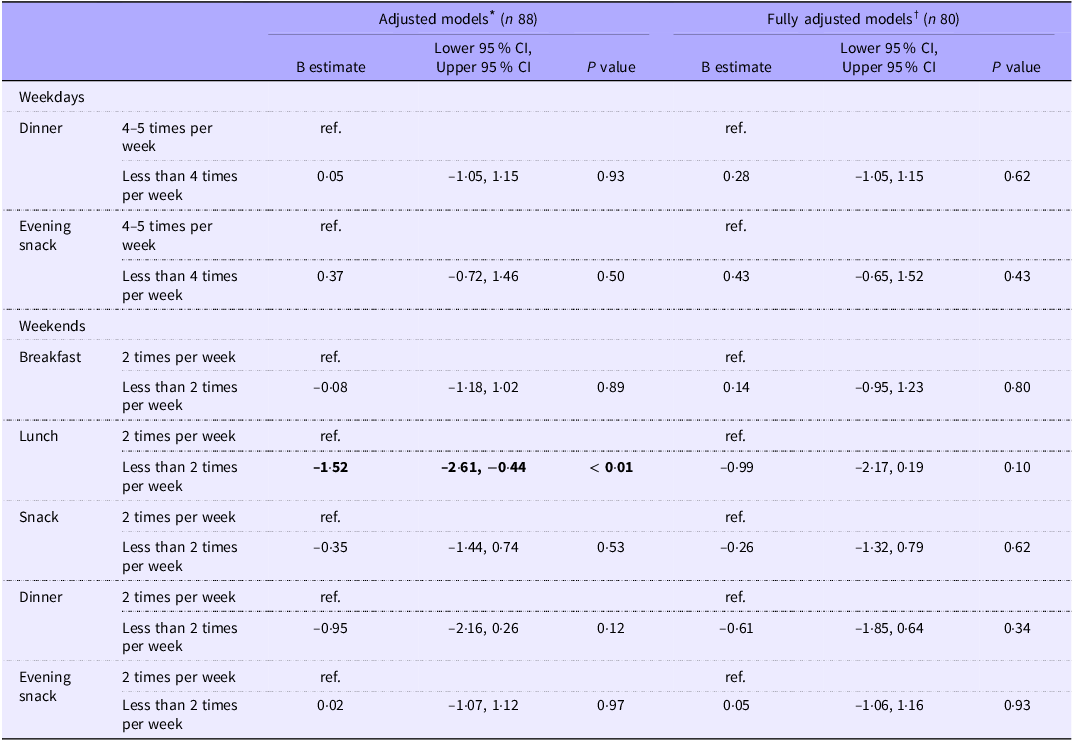

After adjustments for child’s age and gender, father-reported less frequent weekend lunch was statistically significantly associated with the child’s lower HFII score (B estimate –1·52, 95 % CI –2·61, –0·44) (Table 2). With further adjustments (father’s age and educational level, number of children living in the same household), the association weakened but was still somewhat close to statistical significance (B estimate –0·99, 95 % CI –2·17, 0·19). No statistically significant associations were found for other meal types.

Table 2. Linear regression models investigating the associations between father-reported frequency of shared meals and children’s Healthy Food Intake Index in the DAGIS intervention baseline (2017)

Boldface indicates statistically significant estimates (p < 0.05) along with their 95% confidence intervals.

* Models adjusted with child’s age and gender.

† Models adjusted with child’s age and gender, father’s age and educational level and number of children living in the same household.

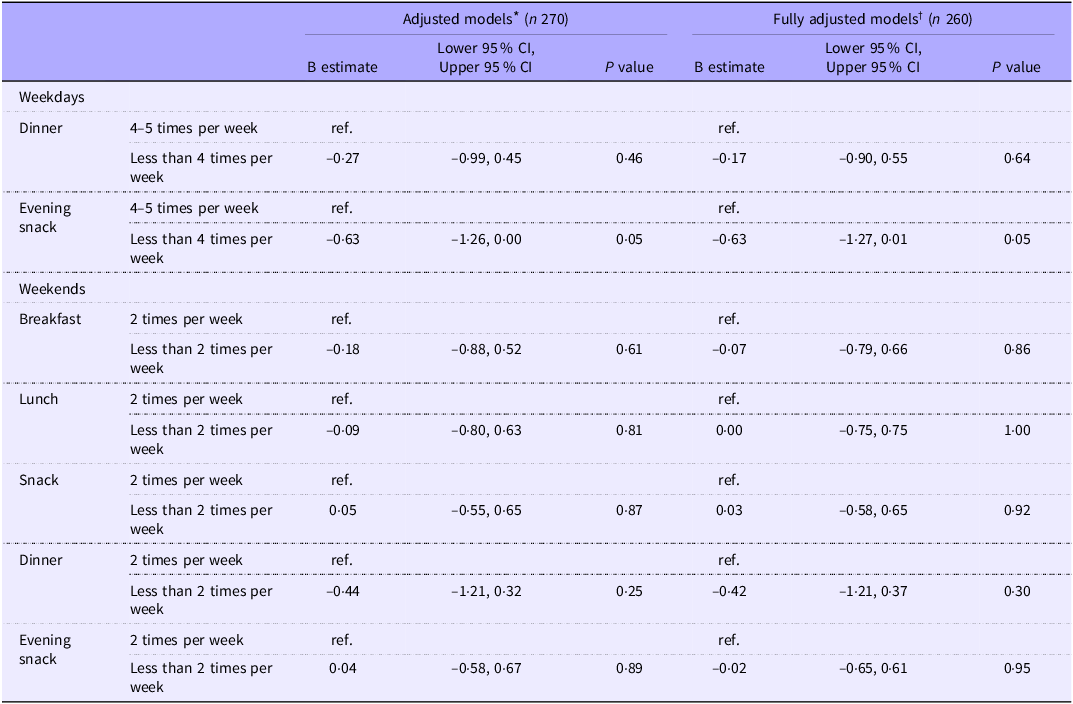

When looking at mother-reported shared meals, we found a borderline significant association between less frequent weekday evening snack with the child and the child’s lower HFII score in the adjusted (B estimate –0·63, 95 % CI –1·26, 0·00) and fully adjusted models (B estimate –0·63, 95 % CI –1·27, 0·01) (Table 3). The sensitivity analysis among families with complete data (n 52) showed that less frequent weekday dinner with at least one parent present was associated with the child’s lower HFII score (B estimate −1·82, 95 % CI −3·62, −0·01).

Table 3. Linear regression models investigating the associations between mother-reported frequency of shared meals and children’s Healthy Food Intake Index in the DAGIS Intervention baseline (2017)

* Models adjusted with child’s age and gender.

† Models adjusted with child’s age and gender, mother’s age and educational level and number of children living in the same household.

Parents’ dietary quality

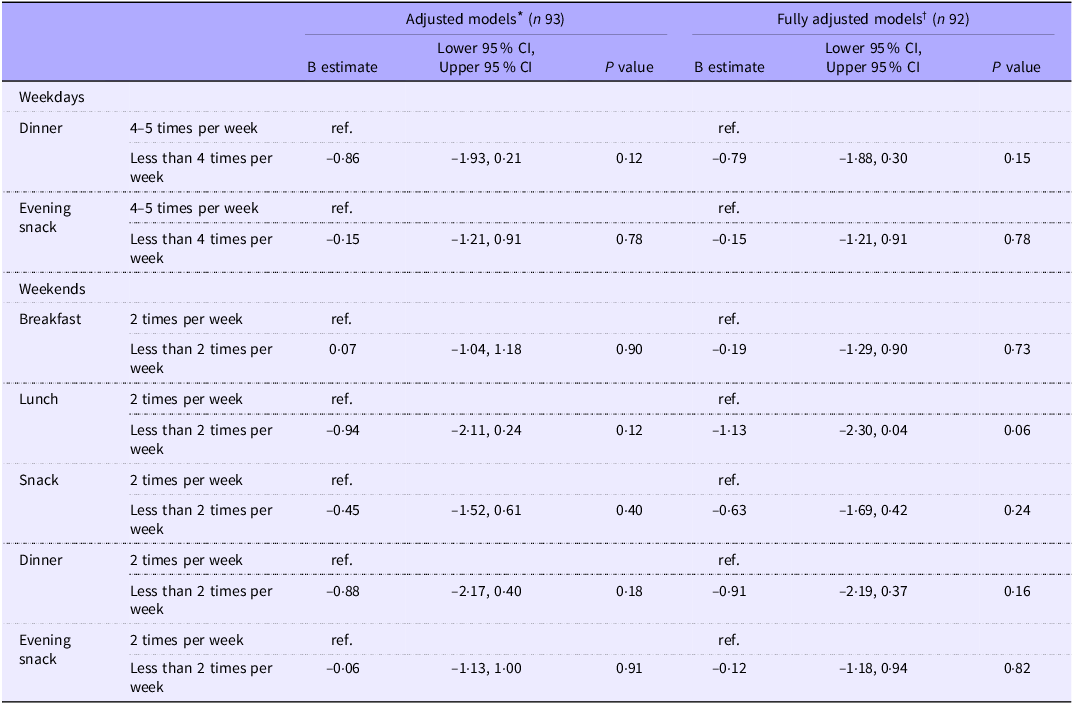

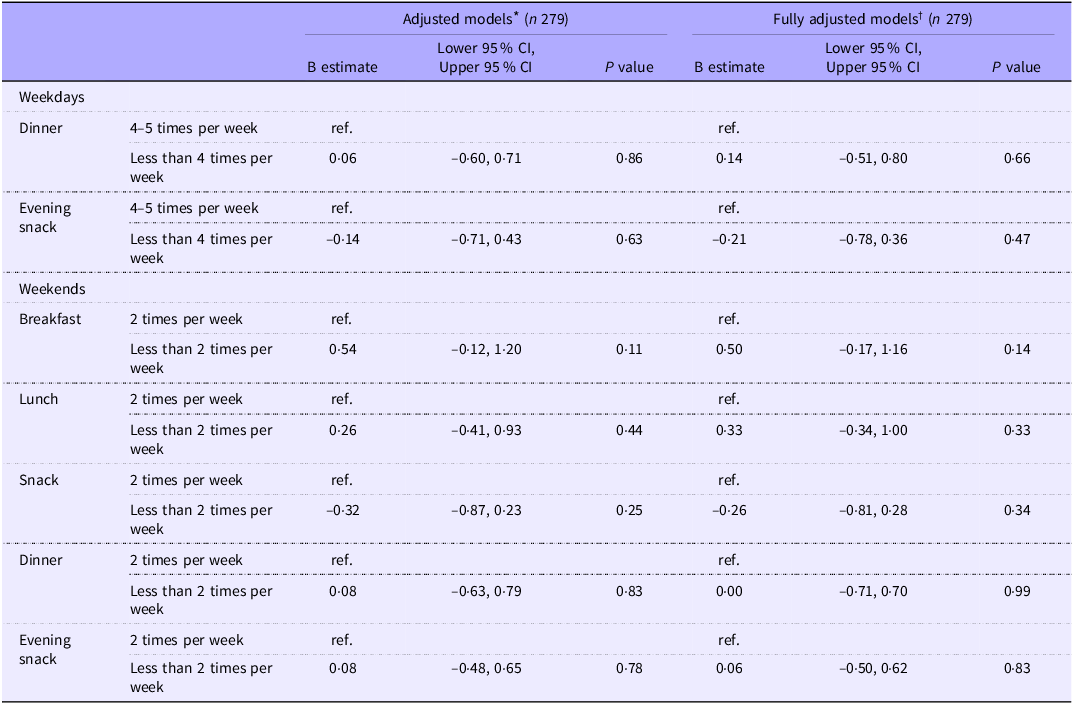

Father-reported less frequent weekend lunch with the child was borderline statistically significantly associated with the father’s lower HFII scores in the fully adjusted model (B estimate –1·13, 95 % CI –2·30, 0·04) (Table 4). We found no statistically significant associations for other meal types. Mother-reported frequency of shared meals was not associated with the mothers’ HFII scores (Table 5).

Table 4. Linear regression models investigating the associations between father-reported frequency of shared meals and fathers’ Healthy Food Intake Index in the DAGIS Intervention baseline (2017)

* Models adjusted with fathers’s age and educational level.

† Models adjusted with father’s age and educational level, child’s age and gender and number of children living in the same household.

Table 5. Linear regression models investigating the associations between mother-reported frequency of shared meals and mothers’ Healthy Food Intake Index in the DAGIS Intervention baseline (2017)

* Models adjusted with mother’s age and educational level.

† Models adjusted with mother’s age and educational level, child’s age and gender and number of children living in the same household.

Discussion

According to the hypothesis, we found that in families where fathers reported less frequently sharing a weekend lunch with the child, both the children and fathers had lower dietary quality. The difference was modest in absolute terms, but the 1-point (6 %) difference between the groups still suggests that family meals may be an important determinant of dietary quality for both children and fathers. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the associations between father- and mother-reported shared meals and dietary quality separately. Furthermore, the study is one of the first to separate weekday and weekend meals as well as different meal types, thus enabling comparison of their significance.

This study revealed three novel findings. First, even though both father- and mother-reported shared meals were associated with dietary quality among children, the associations were stronger among father–child dyads. Earlier studies have revealed a similar association but have studied only, or mostly, mothers(Reference Mou, Jansen and Raat11,Reference Berge, Hazzard and Trofholz12) or have not specified whether the primary caregivers were fathers or mothers(Reference Berge, Truesdale and Sherwood10). Thus, the current paper is the first to identify such an association in father–child dyads. This is of importance, since while mothers still view themselves as the primary caregivers in families, fathers also have at least some responsibility to feed their child(Reference Rahill, Kennedy and Kearney26). Moreover, around three-quarters of a sample of Finnish fathers have reported often or always being responsible for obtaining or preparing food for their preschool-aged child(Reference Tallberg27). Taken together, these results highlight the importance of fathers as active parents and contributors to the home food environment. Intervention studies should aim to engage and recruit fathers also instead of acknowledging mothers as the default parent that matters.

Second, father-reported frequent family meals were associated not only with higher dietary quality among the children but also among the fathers themselves. It is possible that the fathers’ role in modelling healthy food behaviours to their child thus also improves their own diets. Our result is in line with an earlier cross-sectional study that reported higher fruit and vegetable and lower fast-food consumption among fathers who had frequent family meals(Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17). Unlike earlier studies(Reference Rex, Kopetsky and Bodt9,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17) , we did not find an association between mother-reported family meals and the dietary quality of the mothers. A possible explanation for this null finding is the high prevalence of frequent family meals among mothers. In our sample, 78–82 % of the mothers reported frequent main meals (weekday dinner and weekend breakfast, lunch and dinner) together with the child, whereas the corresponding percentages among the fathers ranged between 56 % and 76 %. Mothers also had higher HFII scores compared with fathers in the current study, which was expected as women are known to adhere to a healthy diet more closely compared with men(Reference Valsta, Tapanainen and Kortetmäki28). This may relate to, for example, better nutritional knowledge among women(Reference Kliemann, Wardle and Johnson29), which, in turn, may be reflected in improved dietary quality(Reference Spronk, Kullen and Burdon30). As we know from our previous study that fathers and mothers of preschool-aged children tend to have at least moderately similar diets(Reference Vepsäläinen, Nevalainen and Fogelholm31), families sharing a meal frequently could potentially improve both the children’s and the fathers’ dietary quality.

Third, the association between father-reported shared meals and dietary quality was observed for weekend lunch only. However, as the estimate for weekend dinner was noticeably higher than for other meal types, it is possible that with a larger sample size, the association would have been statistically significant also for weekend dinner. These observations suggest that weekends hold more significance in terms of dietary quality in families, perhaps due to, for example, more relaxed schedules and reduced time pressure, which may allow parents to focus on meal preparation and enable children to participate in cooking. There is limited research on the significance of weekend meals compared with weekday meals, but more meals seem to be shared on weekends(Reference Berge, Doherty and Klemenhagen32) and a shift towards weekend shared meals as a way for the whole family to spend time together has been identified in a sample of mothers in Mexico(Reference Villegas, Hammons and Wiley33). Future interventions should emphasise weekend meals and provide families with healthy, environmentally sustainable and easy-to-cook recipes, which allow child involvement.

Eating together as a family creates opportunities for the parents to act as role models and, on the other hand, for the children to assimilate health behaviours, such as healthy food consumption(Reference Ong, Ullah and Magarey34). In our previous study, role modelling was the strongest home environmental factor predicting fruit and vegetable consumption among 3 to 6-year-old Finnish children(Reference Paasio, Ray and Kokkonen35), and a similar, consistent result has also been found in a meta-analysis of 37 studies(Reference Yee, Lwin and Ho36). However, as there is still limited research on family meals and their significance, correlates and mechanisms of action, more research is needed to clarify these complicated relationships(Reference Boles and Gunnarsdottir37). For instance, reviews have suggested that families having more time may predict more frequent family meals(Reference Snuggs and Harvey38) and that family meal frequency may act as a proxy for family functioning(Reference Robson, McCullough and Rex15), suggesting that intermediate or independent explanatory variables may be missing in many of the studies. Moreover, most of the studies investigating shared meals and dietary quality in families, including the current one, have been conducted in cross-sectional settings (e.g. (Reference Caldwell, Terhorst and Skidmore4,Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann8,Reference Berge, Truesdale and Sherwood10,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17) ), which makes it challenging to evaluate the direction of the observed associations. Therefore, studies focusing exclusively on family meals and using standardised assessment methods in longitudinal and experimental settings are badly needed.

Strengths and limitations

The study has several strengths. First, unlike earlier studies(Reference Caldwell, Terhorst and Skidmore4–Reference Rex, Kopetsky and Bodt9,Reference Berge, Hazzard and Trofholz12,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17) , we were able to explore the different meal types (lunch, dinner and snacks) as well as weekdays and weekends separately, enabling a deeper understanding of the complex factors related to eating behaviours. Second, even though the number of fathers in our sample was relatively small, we were able to investigate the associations between family meals and children’s dietary quality separately for fathers and mothers. This study may thus serve as a stepping stone for future studies taking a closer look at the role of fathers at the dinner table. Third, the current study offers invaluable information about an understudied North European population, given that family meal culture and traditions may differ from North America, where most of the previous studies have been conducted(Reference Caldwell, Terhorst and Skidmore4–Reference Noiman, Lee and Marks6,Reference Fink, Racine and Mueffelmann8–Reference Berge, Truesdale and Sherwood10,Reference Berge, Hazzard and Trofholz12,Reference Dugas, Brassard and Bélanger13,Reference Berge, MacLehose and Loth17) . Finally, instead of focusing on single food groups, such as fruit and vegetables or sugar-sweetened beverages, we used an FFQ-based dietary quality index, which has previously been used among Finnish adults. Thus, we were able to take the whole diet into account while considering the healthiness of the diet.

The current study also has limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, we used HFII as an indicator of dietary quality, although its validity among healthy mothers, fathers and especially children is unknown. Moreover, as the child FFQ only included foods eaten outside preschool hours, it most probably underestimated the HFII among the children. However, as this was the case for all the children and the relative validity of the FFQ has been shown to be acceptable(Reference Korkalo, Vepsäläinen and Ray20), it is likely that this systematic error did not affect the explored associations. Second, as only 37 % of the children participating in the DAGIS Intervention could be included in the current study, the sample was somewhat selected. This limits generalisability of the results, although the included and excluded children did not differ in terms of age and gender. Moreover, the small number of fathers included in the study could have led to both overestimation and loss of power in the analyses. Keeping this in mind, our results should be viewed as preliminary and tested in future studies. Third, multiple factors influence both dietary quality and family meal frequency, and capturing all of them would be impossible. For example, the parents’ opportunities for healthy eating during working hours may depend on their occupational status(Reference Raulio, Roos and Prättälä39), and having a TV on or other media devices present during family meals can influence dietary quality(Reference Snuggs and Harvey38,Reference Robinson, Domoff and Kasper40) . Therefore, even though we aimed to cover the most significant confounders, residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

Conclusions

This study found that less frequently shared weekend lunch was associated with lower dietary quality among fathers and children. The observed associations were modest, yet potentially meaningful for overall diet patterns. Therefore, both fathers and children could benefit from families eating together more often and fathers should be encouraged to share meals together with their child to support a healthy home food environment. Weekend main meals, in particular, seem to have potential for modelling healthy food behaviours. As these results were drawn from a small, cross-sectional sample, future studies should be conducted in longitudinal and experimental settings, recognise the role of fathers in shaping the family food environment and invest in recruiting fathers as study participants to neutralise the role of mothers as the primary caregiver.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114525105722

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the preschools, the preschool personnel and the families for their participation in the DAGIS study, and the research staff for data collection. The authors thank the collaborating partners of the DAGIS study for providing assistance in designing the DAGIS study.

This study was financially supported by the Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, the Research Council of Finland (Grant: 315816), the Päivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation, Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation, Folkhälsan Research Center and the University of Helsinki. The funding bodies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

H. V.: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualisation. R. L.: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing. A. M. R.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing. J. B.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing. J. R.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing. N. S.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing. E. R.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. C. R.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing, Project administration, Funding acquisition. M. E.: Conceptualisation, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

The study was reviewed by the Research Ethics Committee in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences of the University of Helsinki (22/2017; 16 May 2017) and found ethically acceptable. A parent or legal guardian of each participating child provided an informed consent.

The data generated and analysed in this study are not publicly available due to the privacy of participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.