Introduction

Higher education as a public good is under threat! The multiple intersecting crises in which our societies are immersed, from environmental devastation to the collapse of democracy, from economic exploitation to racial and sexual violence, have been both enabled and critiqued, in its spaces. Barnett (Reference Barnett2024) has argued that higher education is social, real and critical. For some time, it has been seen to be responsible for addressing these social and real intersecting crises through education for sustainability (Gale et al., Reference Gale, Davison, Wood, Williams and Towle2015), even though this potential responsibility has been claimed to be unlikely (Stein, Reference Stein2019) if we consider what is to be sustained.

As higher education institutions, universities simultaneously constrain and enable action as a response to such crises in intricate, complex and, often, contradictory ways (McCowan, Reference McCowan2019). They are expected, on the one hand, to develop work-ready graduates who will fit into current societal structures, get jobs and be “successful,” whilst, on the other hand, to nurture critics and transformers who can bring about change (Stein & Andreotti, Reference Stein and Andreotti2025). As the metacrisis demands radical change, it is unsurprising that universities appear trapped in this tension, and are losing the faith of their staff, their communities and governments.

University educators are located at the heart of this conundrum. They have been asked to grapple with its trajectories and implications, whilst at the same time operating within a “business” which is required to churn out graduates who face a complex and uncertain future but who expect an education that enables them to progress in life (often viewed as financial and material progress). In this context, what are university educators doing to respond to the metacrisis, and how should they respond?

In this paper, as four Aotearoa New Zealand university educators from different disciplines in one institution in conversation with each other, we examine the impact the metacrisis has had on our work and reflect on our responses to it. We engage in structured conversation with each other about how universities (re)produce and challenge the metacrisis, and the complex forms in which this tension is exemplified in our everyday work.

We begin by identifying what the metacrisis means to us through our diverse theoretical and conceptual perspectives, and how it is impacting higher education generally, before exploring our lived experiences of the metacrisis in our work, and drawing implications for the field of environmental education in higher education.

Identifying the metacrisis within universities

The metacrisis has been described as an amalgam of intersecting crises affecting all sectors of society and the Earth’s capacity to sustain life (Wheatley, Reference Wheatley2025; Irwin & Everth, Reference Irwin and Everth2024; Stein, Reference Stein2022). These include climate change, ecological collapse, weakening of democratic institutions and social cohesion, widespread racial and sexual violence, increasing economic inequality and poverty, rise of mis/disinformation, refugee migration and so on. As Wheatley (Reference Wheatley2025) explains, these are not separate challenges – they form a single, interconnected global metacrisis. It is interconnected as the various socio-ecological crises feed into each other (e.g., climate disasters exacerbate economic inequalities, which in turn threaten social cohesion).

Contingent historical conditions have given rise to social systems and ideologies that have prioritised hegemonies and economic progress, contributing to a separation of humans from nature. The ever-hastening pace of the march from corporate capitalism to oligarchic capitalism has been exemplified in neoliberalism’s promotion of what Stein and Andreotti (Reference Stein and Andreotti2025) have called “hyper-individualism” and “hyper-polarisation.” Hyper-individualism and hyper-polarisation are a consequence of “hyper-specialisation” (Millgram, Reference Millgram2015). Hyper-specialisers focus upon one fine-grained topic within a broader area and cultivate a proprietary vocabulary that only other experts in that narrow topic may comprehend. This leads to an extreme form of a division of labour (Lumsden & Ulatowski, Reference Lumsden and Ulatowski2019). For example, environmental economists communicate well with other environmental economists but can hardly be understood by specialists in econometrics or experimental economics. Lewis Gordon (Reference Gordon2006) has argued convincingly that this is a sign of “disciplinary decadence” which occurs “when a discipline gives up its reach for or at least movement toward reality and turns inward to make itself into reality. It, thus, treats its methods as practices created by the equivalents of gods. “Fetishizing of methods emerges” (Gordon, Reference Gordon2006, p. 39). Our move toward specialisation in very narrowly conceived projects is a sign of epistemic colonisation (Gordon, Reference Gordon2014; Monahan, Reference Monahan2011). For example, consider political parties. Feelings of superiority occur when political party members only understand other party members because they share the same values and policies. Communicating with people who do not share their views becomes impossible.

This communicative breakdown eroding democracy has reinforced old forms of colonialism (Stein, Reference Stein2019) and introduced new ones, thereby deepening racial, gender and economic inequalities, and reducing social cohesion. The metacrisis has also been fuelled by a growing distrust of experts and the knowledge they have and share with others (Osborne et al., Reference Osborne, Pimentel, Alberts, Allchin, Barzilai, Bergstrom, Coffey, Donovan, Kivinen, Kozyreva. and Wineburg2022), a muddying of truth and an obfuscating of who we are and what we might become (Lynch, Reference Lynch2019, Reference Lynch2025; O’Connor & Weatherall, Reference O’Connor and Weatherall2019). This lack of clarity and direction has loosened our sense of place on this Earth and divided us from a realistic understanding of our impact on Earth systems (Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Richardson, Rockström, Schellnhuber, Dube, Dutreuil, Lenton and Lubchenco2020).

Higher education, particularly in universities, has been considered to have a role in developing knowledge and skills for “societal progress” (McCowan, Reference McCowan2019). There is a tension in the balance between the pursuit of what is conceived of as progress and the notion of sustainability clearly evident in university life (Gale et al., Reference Gale, Davison, Wood, Williams and Towle2015). In recent years, universities have been tasked by the United Nations with addressing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Hessen & Schmelkes, Reference Hessen and Schmelkes2022; Serafini et al., Reference Serafini, de Moura, de Almeida and de Rezende2022), which exemplify one way in which progress may be measured, whilst simultaneously aiming to achieve sustainability goals (Times Higher Education, 2025; McCowan, Reference McCowan2019). This imperative has been reported in many areas of university endeavour, including teacher education (Beasy et al., Reference Beasy, Richey, Brandsema and To2024).

Furthermore, there is a tension between making university study accessible to everyone and making university a marketable product. While universities were originally the bastion of the few who were able to forgo domestic responsibilities, the rise of the tertiary sector and neoliberalism opened the way for growth of higher education. However, the focus of academic capitalism (Slaughter & Rhoades, Reference Slaughter and Rhoades2004) on “bums on seats,” competition and performativity has got “into our minds and our souls (…) and into our social relations with others” (Ball, Reference Ball2012, p. 18). The political project of commodification of universities acts on the very subjectivities of university educators through the technology of performativity. In that way, the issues that we think about are significantly determined by economic rationalities and demands, such as enrolment numbers and employability (Hartmann & Komljenovic, Reference Hartmann and Komljenovic2021).

The culture of performativity has disconnected university academics and their students from socio-ecological issues, from their disciplines, and from each other. Commodifying higher education has increased demand for certain subjects because they are seen to be economically-instrumental, but which may perpetuate the metacrisis when focused exclusively on vocational pathways, at the expense of others that develop the critical and creative potential to re-imagine our way out of this dilemma (McKinnon, Reference McKinnon2023). Students’ expectations rise when they pay fees and invest in studying offshore, dislocating from place and disconnecting from their communities (Kraus, Reference Kraus2023; McMurtie, Reference McMurtie2024). University academics, whose collegial tendencies to share and learn from each other are disrupted by accountability mechanisms and competition for students, find tensions between apparent calls for collaboration and the reward structures which privilege the individual (Godonoga & Sporn, Reference Godonoga and Sporn2022).

This performativity corrodes the act of thinking: as a cultural praxis in which knowledge is nourished; as a political praxis in which critique is elicited; and as an ethical praxis in which academics are both constituted and transformed. We draw on Ball’s (Reference Ball2003) definition of performativity as:

a technology, a culture and a mode of regulation that employs judgements, comparisons and displays as means of incentive, control, attrition and change, based on rewards and sanctions (both material and symbolic). The performances (of individual subjects or organizations) serve as measures of productivity or output, or displays of ‘quality’, or ‘moments’ of promotion or inspection. As such, they stand for, encapsulate or represent the worth, quality or value of an individual or organization within a field of judgement. (p. 216)

Knowledge and knowing, by both academics and students, becomes commodified (Lyotard, Reference Lyotard1984) as it is justified in terms of “productivity,” represented and made visible in forms of measurement, such as journal publication and SDG rankings, marking rubrics, or student enrolments. As Ball (Reference Ball2012) argued, “in regimes of performativity, experience is nothing, productivity is everything” (p.19). This culture of performativity pervades the university curriculum, pedagogy and assessment, as well as research and operations. It has considerably undermined the capacity of public universities to produce dissent, encourage critical thinking, search for truth, hold power accountable and inspire radical imagination (Giroux, Reference Giroux2014).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the neoliberal programme of the late 1980s and its higher education reform, Learning for Life (Lange & Goff, Reference Lange and Goff1989), instituted a new way of understanding higher education as a commodity and profit-making exercise (see Codd, Reference Codd, Codd and Sullivan2005). In the 21st century, the Third Way ideas of Aotearoa New Zealand as a knowledge economy and society largely consolidated this understanding and the culture of performativity explained above. This also diminished the role of higher education institutions as “critics and conscience of society,” which significantly limited their ability “to conceive and build alternative futures” (Roberts, Reference Roberts, Codd and Sullivan2005, p. 40). In recent times, this culture has been illustrated on the one hand by influence in shutting down criticism of corporations (Radio New Zealand, Reference Zealand2024), whilst on the other hand, external influences meddle with university decisions about academic freedom. In the latter case, these influences seek to enact legislation to force universities to allow speakers with discriminatory agenda to have a platform on campuses (New Zealand Parliament, 2025). These tensions compromise the responsibility/response-ability of a university (Barnett, Reference Barnett2024) to confront or simply perpetuate the metacrisis.

In considering these tensions, our conversation focused on the premise that the metacrisis requires an interdisciplinary, collegial approach that goes beyond any one discipline, individual and/or disconnected analyses of one set of problems (Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Wreford, Blackett, Hall, Woodward, Awatere, Livingston, Macinnis-Ng, Walker, Fountain, Costello, Ausseil, Watt, Dean, Cradock-Henry, Zammit and Milfont2023). We draw upon structured conversation with each other in which we purposefully explore the tensions we experience in our diverse social and environmental fields and seek pathways to move us beyond the metacrisis.

Our structured conversation approach

We are a group of colleagues working in a range of disciplines in higher education, bound together by a common interest in the metacrisis, its impact on our university and our interdisciplinary aim to forestall any descent into hyper-specialisation in our work. Chris has been employed at the University of Waikato for more than 30 years in the sciences and more recently education, specifically environmental and sustainability teacher education. Marta, Pablo and Joe have joined the University in the last 5 – 10 years but have been employed within the higher education sector for 10 – 20 years. Marta has a background in social sciences education, Pablo has a focus on sociology of education, and Joe teaches philosophy.

Our methodology may be traced to Socrates. We adopted a form of “Socratic Method,” but not the form where interlocutors, sometimes relentlessly, question others and people prepare answers in the hopes of not being resoundingly refuted and sometimes humiliated. The more sanguine approach we employed premised that interactions can reveal how non-combative and conciliatory discussions between interlocutors put us in a better position to understand more complex ideas, acquire a more sophisticated skill set, and advance our understanding of the world Drawing on Levinas’ Socratic-inspired principle that “thought is inseparable from expression” (Levinas, Reference Levinas1989, p. 126), we considered “conversations” as prolific sites that lay out enabling conditions for new understandings and becomings. Our structured conversations, on this basis, were not only attempts to make sense of the metacrisis and its urgencies, but “a momentary disruption of the life of the everyday” that enabled us to “develop a sensitivity” (Todd, Reference Todd2015, p. 249) to the situation that we inhabit.

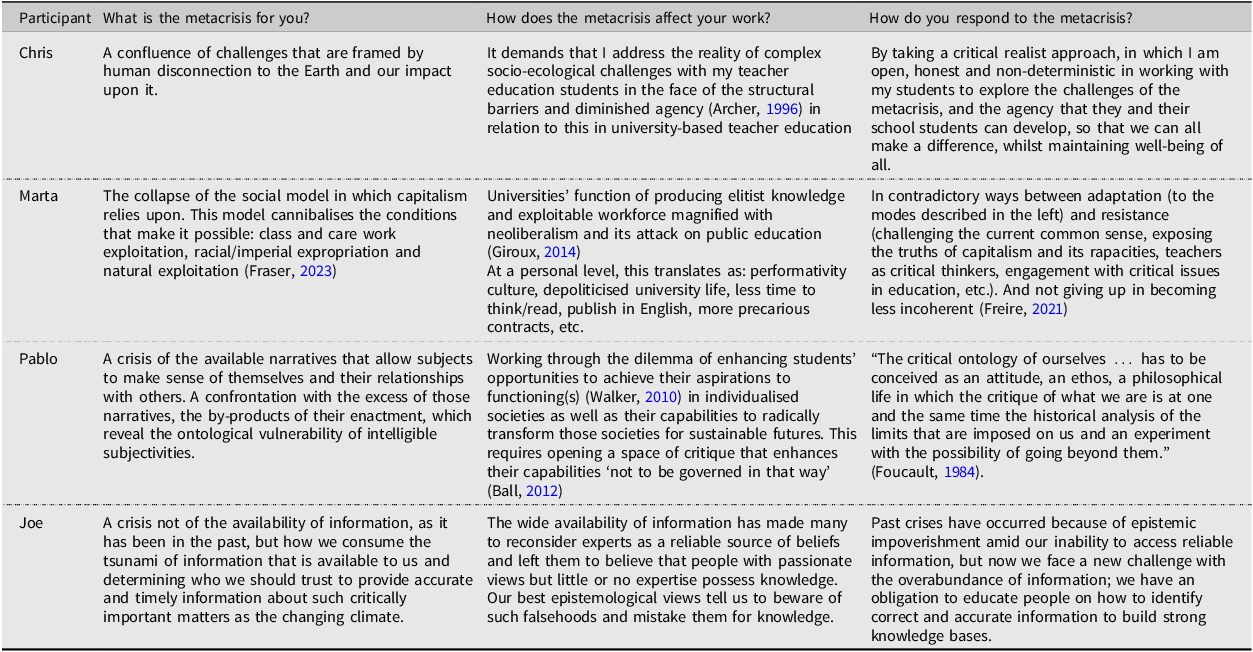

It is important to be explicit on the discursive conditions of these conversations – we are academics who were provoked to write upon reading a call for papers for a special issue of an indexed academic journal. On this basis, the conversations brought forward our academic voices, which tended to hegemonise the space, we relied on theory and method to elaborate our ideas, and we spoke as scholars to an academic audience. Yet, our structured conversations also gave space to our personal responses, to sharing our lived experiences of our profession, and our sense of place and purpose in the university, A final element that requires reflection is the article itself, in which we have come together, with our disciplines and theories, our lived experiences and emotions. This article, in various ways, justified the conversations. As well as being a measurable output of our professional activity, it is a creation made up of diverse philosophical “sensitivities” (Kincheloe, Reference Kincheloe2001, p. 688) that are articulated as a collage that presents, and suggests, common and different understandings and experience (de Rijke, Reference de Rijke2024). In the metacrisis, we are in challenging and uncharted territory that requires us to think with new concepts and methods (Berseth & Letorneau, Reference Berseth and Letourneau2025). This article-as-collage, with its articulations and breaks, is crafted to expand the broader conversation on the metacrisis, but also as material for further creations and thought. We began our work together by individually writing our thoughts on questions about the metacrisis and how it is affecting our work, and how we are responding to it (see Table 1). We read each other’s writing and discussed our analyses of the metacrisis. Our next step was to design a structured conversation through which we used the same questions to discuss, with each of us in turn being the focus, more deeply our sense of how the metacrisis was impacting our work and how we were responding in our own ways. These conversations lasted 25 – 30 minutes for each person.

Table 1. Summary of initial written thoughts

Data were initially captured by audio recording and subsequently transcribed using online software (Microsoft Teams). We then read all the transcriptions, and conducted a thematic coding collectively, drawing on our diverse theoretical and conceptual perspectives. We critiqued and discussed codes over several meetings before arriving at consensus.

From an ethical point of view, we were conscious of the fact that we are employees of a university. As a member of a university and under New Zealand law, we have a legal obligation to be “the conscience and critic of society” (The New Zealand Education Amendment Act Sec 162(4)(a)(v)). However, we also appreciate that the university, our employer, may not uphold the views that we express in this article, as articulated above. For this reason, we feel it is important to indicate that the views and opinions expressed in this article are our own and not those of our university. Moreover, the views that we express here do not apply to our university alone; we are thinking more widely about the higher education sector and all the universities and other institutions that form the sector.

The metacrisis in our work

Our conversation about the metacrisis and its effects on our work in higher education began with the recognition of the different ways of seeing and experiencing the world. This recognition led us to share our initial thoughts in a written form (see Table 1).

These initial written thoughts made it obvious that we had very different readings of the nature of the metacrisis. For Chris, the problem lies in the human disconnection to the Earth and the lack of agency in addressing the issues constituting the metacrisis; for Marta, the metacrisis embodies the collapse of the social model upon which capitalism relies; for Pablo, it is a crisis of available narratives; and for Joe, it consists of crises where accurate information is not difficult to come by but difficult to discern from misinformation. As the Table shows, these different diagnoses led us to different interpretations of the effects and responses of/to the metacrisis. The oral conversations that we had afterwards, however, helped us to see commonalities in these initial written thoughts and to develop new ideas for addressing the metacrisis. These commonalities/themes are presented below, with examples from our conversation.

Universities as a space for critique

Despite the neoliberal logic of the institution, for all of us, universities offered a space for critique of society or, more particularly, of the metacrisis. We understand this critique as a form of resistance to power, yet this resistance had different meanings for each of us. For Chris, resistance is related to the raising of environmental awareness and, in particular, to the reconnection of ourselves to the Earth – an act of resilience and regeneration. For Joe, it is linked to the cultivation and acknowledgement of the limits of our knowledge, epistemic humility, amid an information crisis. For Marta, drawing on Gramsci, resistance is connected to the possibility of challenging the current common sense, the search for truth and the building of counter hegemonic blocs. Finally, for Pablo, resistance has to do with the possibility of becoming/doing otherwise. As expressed in his conversation:

I think it has to do with, drawing on Foucault, to be able to pronounce who we are, differently. Basically, the possibility to pronounce a critique of education, [which] is also a possibility of becoming differently. So it has to do with this set of responsive abilities. We live in this world, we live, in this particular kind of education - and it’s not about the freedom of conscience of saying, I know this is wrong, but I still do it. It’s about trying to do it differently somehow.

Despite the differences between our ways of understanding resistance, the possibility to think, to discuss, to dissent, to question the taken-for-granted, to raise critiques and to reflect about the consequences of our acts as individuals and societies provided all of us with a sense of meaning to our work. Yet, as we all agreed, this possibility is often served in small doses and emerges at the margins of our institutional work. Pablo reflected on a meaningful, critical conversation with students that happened at these margins:

The university is probably one of those spaces in our lives, in our biographies where we can think some things that we won’t be able to think in other spaces… even conversations, having a critical conversation. I remember this semester, I was giving a tutorial, the topic had been finished. So, after that some students left and some stayed. And just by chance a colleague arrived and we had a really fantastic conversation about charter schools in [Aotearoa] New Zealand and how they operated, and being really critical in terms of the questions that we could be posing, and I think that could be an example of that sort of education [that could happen] otherwise. And [is was possible] because we had completed our [class] duty in terms of performativity.

Pablo was not the only one pointing out the constraints for critique under the performativity regime of universities. The four of us agreed that the function of universities as a space for critique is increasingly being reduced to a minimum in this regime. Drawing on the work of philosopher Byung Chul-Han (Reference Han2023), Marta spoke about the loss of our ability to do nothing, arguably essential for critical thinking and praxis to emerge. She considered time – to stop, to think, to do nothing – as a critical claim that we all should be pursuing to guarantee the critical role of universities. As she expressed it in her conversation:

…we have lost our ability to do nothing. And when we lose that ability, which is what actually makes us human and distinguishes us from these machines, then we lose our ability to think. He [Byung-Chul Han] has this metaphor that I think is really powerful that says ‘there’s no music without silence, only noise and sound’. And it’s so real. We can’t really think when we don’t stop, when we don’t have time.

Joe also expressed concerns about contemporary restrictions on academic freedom. As he explained in relation to prohibitions against academic freedom, such as seen recently in his native USA:

I’m even more worried about implicit forms of restrictions [in] academic freedom coming from administrators within higher education, and that is actually deeply concerning me because it’s a form of epistemic arrogance … We need a means of being a critic and conscience of society.

Chris reflected on the apparent lack of concern and commitment expressed by some of his beginning teachers towards socio-ecological challenges, despite them being exposed to, and engaging in critique of these challenges. In his conversation, between humour and frustration, he raised the prospect of whether democracy was offering an effective pathway to address these challenges:

We don’t want to tell people what to do, do we want to lay out opportunities in front of them and give them a chance to think about those with the hope, sometimes vain hope, that they’ll come to their senses, whatever that looks like, and make the right decisions for the future. So, interesting how that plays out, and obviously it hasn’t played out very well in the last 50 years as we’ve drifted more towards the metacrisis. So maybe we do have to be more deterministic, maybe we’ve got to take a bit more control and we’ve got to tell people what to do?

Marta shook her head, while Pablo tried to work through his discomfort. For Marta, this reasoning provides a pathway for authoritarianism to flourish, regardless of whether it is embodied by a politician or by a more benign looking–climate expert. For her, the role of universities as a space for critique attempts precisely to avoid “telling people what to do,” but to provide more refined and sophisticated tools to examine society, always attentive of the ways in which power coopt these tools. Pablo felt fearful of his ignorance and felt vulnerable. He would subscribe to the idea that ignorance on climate change is a public threat, but at the same time he considered himself ignorant - while he hid this staining mark under his carefully practiced academic manners. The stakes were low in this collaborative conversation, but he wondered what might the consequences be if we were to have any influence in government. What kind of violence would we be willing to accept in the name of protecting the planet, or rather, our species? Suddenly returning from his daydream to the glassed meeting room, he felt overwhelmed by the responsibility of his position. He was not in a government taskforce, but he was a lecturer in a university. His statements unavoidably carried forms of authority and power that were dangerous in the uncertain contexts of the metacrisis.

Disconnection, performativity and epistemic humility

how we see ourselves in relation to ecosystems, how we see ourselves in relation to each other, how we see ourselves in relation to ourselves. If we understand and develop our thinking in those spaces, then I think that’s got to be powerful and helpful (Chris)

One of the fundamental issues that emerged in our conversations was the acknowledgement of the ways in which the current state of our academic profession and university disconnects us from each other, from larger civic issues, from the environment and ourselves at various levels. We identified the culture of performativity as a ubiquitous issue, which undermines these relationships that are constituted by, and constitutive of, the university. The culture of performativity separates knowledge from thought, as thinking becomes a performative exercise, rather than a process of becoming differently, a transformative experience and act. In the above quotation, Chris suggested that we need to re-think our relationships in the metacrisis – and our conversations looked into how performativity is eroding the very conditions of possibility of thinking and thought in our institutional contexts and practices.

Pablo proposed that knowledge is currently detached from higher education. It is “a performative exercise to satisfy a rubric or a marking criteria” - and we could add, a citation or impact indicator that eventually contributes to university rankings. These forms of measurement come to represent the value of knowledge, following logics of economic efficiency and profit. Marta agreed that the contemporary neoliberal university “is about following economic imperatives, creating exploitable workers, and it’s also about pursuing individual careers”. The culture of performativity in higher education is a tool of neoliberal government to make universities operate as businesses, where the value of education is only justified in terms of student enrolments and passing rates. This culture also leads scholars, including ourselves, to pursue research projects focused on profit-making, increasingly disconnected from larger civic issues.

We discussed how the culture of performativity intensifies the pressures of employability on teaching and learning in the university. That is, higher education becomes both instrumental in the production of a workforce, as well as in obtaining a qualifying degree that will increase the opportunities to be employed. Pablo discussed how, in the role of programme development, there is a responsibility to respond to students’ aspirations for employment, but at the same time those very forms of employment are currently conducive to an unsustainable, unliveable, world. Chris added that the different professions contribute to the siloing of knowledge, and the culture of performativity establishes disconnections between bodies of knowledge, and thinking becomes siloed along divisions established by the organisation of labour.

A further effect of the culture of performativity that undermines the practice of thought is the intensification of work and the disconnection between personal success in the profession and public service. Marta argues that part of the problem lies in that “we are very busy following our own agendas to get a better job, to get a better position, to get to the top”. Chris noted how “academic work is predicated on workload management, on the money that comes in - it’s attached to student numbers”. This lead, as Marta pointed out, to excessive workloads which undermine intellectual work, how “it is so difficult to find time to read”. On these bases, we agreed that it is necessary to refuse resist or even refuse the “performativity mindset” that corrodes the academic profession and is constitutive of the metacrisis.

Epistemic humility

The conversation around performativity elicited an imagination and a desire for a different ontology, a re-constituting of ourselves as university educators freed from the entrapment of performativity. We discussed what the virtue of epistemic humility meant for us and its relevance in the construction of a different university.

Joe explained that epistemic humility is “understanding that you don’t possess pieces of information or evidence for reason or reasons, for whatever claim might be made” (Ballantyne, Reference Ballantyne2019), and being aware of one’s own ignorance. This requires understanding that “we are all fallible creatures, that we don’t know everything and that we have to rely on others”, to check or expand our information and forms of reason. The act of knowing, therefore, is painful and discomforting because it requires constant testing and confronting our own ignorance (Tuana, Reference Tuana, Proctor and Schiebinger2008). Humility is, therefore, an epistemic virtue, or character trait that one habitually reinforces through its being regularly exercised. It is distinct from cognition and emotions or feelings. Being aware of one’s own ignorance exposes us to our own fallibility and vulnerability. On this basis, it sets the conditions to rely on others, it is a principle of relationality, which is being undermined in the metacrisis.

Marta agreed on the importance of this virtue, despite its often painful implications, yet its meaning had different connotations. For her, epistemic humility should not stop with the acceptance of our own ignorance and the inevitable reliance on others. Using as a reference the work of the three “masters of suspicion”, Marx, Freud and Nietzsche, as Ricoeur described them, she argued that this virtue requires an attitude of constant critique to society and culture and, particularly, the illusory narratives that are provided to us about reality. In this sense, epistemic humility is a necessary condition to reveal the irrationality of the social system that has led us to the metacrisis.

Chris reflected on how epistemic humility is also a virtue that enables the practice of critique as it allows for the subject to be aware of, not only their epistemic limitations, but also their material limitations, which are intricately related:

I’ve navigated those sort of things, not always very well, within this university for more than 35 years. And I’ve come to realise that there are some things that you have to do and some things you can’t do (…). So, it’s the picking the battles to see what can be important.

In this way, a constant revision of what is important, and a careful arrangement of the possible, become virtuous practices in the micropolitics of higher education.

Another aspect of epistemic humility in the context of the micropolitics of higher education is the acknowledgement of the necessary interdependence of political action. Chris argued that we need to “listen to other people in society, because we need those relationships to work in order to be able to change something”. Engagement with other agendas poses difficult questions: “do I think climate change is more important than everything else? Absolutely” because climate change constitutes an existential crisis. “But there are other things that do matter along that journey”, which are beyond “my point of view”, Chris added. These considerations of epistemic humility led us to focus on the place of knowledge in higher education in the metacrisis.

Being epistemic agents and truth

For all of us, our approach to teaching in the metacrisis has attempted to work towards expanding our students’ ability to shape their own knowledge and understanding of the world – what we may refer to as “epistemic agency” (Gunn & Lynch, Reference Gunn, Lynch and ackeya2021). This notion, however, inevitably led us to the question of truth. For Marta, the focal point of student learning is the acquisition of more critical and comprehensive ways of explaining the world, which is an explicit consequence of developing one’s epistemic agency. The pursuit of more accurate forms of reading the world (however difficult this might be) is a core part of this endeavour. Marta follows Hannah Arendt’s distinction between factual and rational truth as an analytical tool to distinguish between manipulable and non-manipulable forms of belief. For Marta, if factual truth were subject to political whims there would be no justice:

I am very much Arendtian in that sense of – without truth, there is no justice. And it might be very difficult to get to truth because we have really limited tools (and power) to do so. So, our job should be really to pursue that truth in spite of our limitations.

For Marta, the notion of epistemic agency is also very connected to the Gramscian concept of counterhegemony (Gramsci, Reference Gramsci1971). It is about critiquing the existing status quo and the creation of an alternative ethical view of society that embraces political change. Epistemic agency, therefore, not only involves a cognitive domain, but an ethical and political one.

Yet, for others, the question of truth is less obvious because it cannot be clearly distinguished from honesty or truthfulness (Pablo) or if the question of the nature of truth is secondary (Chris). Pablo is not primarily concerned with the question of truth, but with putting into question the ways in which we come to represent others, our relationships and ourselves, to loosen the space between experience and representation. The humble epistemic agent, as Pablo explained, “there are some ways to challenge ourselves, basically through problematisation, through questioning our assumptions”. He saw that the response to the metacrisis is ultimately enabled by the event of a relationship with the other – human and more-than-human (Levinas, Reference Levinas1989). Chris agreed that relationships were central and that these were being eroded by our disconnected response to reality. A critical viewing of truth could be counterhegemonic and bring about change.

A key aspect at the core of epistemic agency highlighted by Joe is an insatiable curiosity about the world that surrounds us. Learning-centred epistemic agents are curious about the world around them, constantly seeking how to engage with that world. However, curiosity is not possible if we’re limited to what bombards our Instagram feeds and Facebook walls. As Joe explained, just as the quick and cheap diet of McDonald’s negatively affects our physical health, the quick and cheap diet of scrolling the internet adversely affects our intellectual health and well-being. We become victims and agents of misinformation and disinformation campaigns. He identified learning as an ability that one develops over time and through interaction with others:

There is a certain skill set as well as a kind of competence, epistemic competence, that we use to advance in our career. So, you can think of agents as not some kind of empty vessel where you’re trying to fill that vessel with information throughout your career or education. […] It is more important that we become more adept at acquiring new pieces of information.

As highlighted in our conversations, the difficult part of developing epistemic agency is being able to identify when we know things and when we don’t. Admitting that we don’t know something is as much a part of our epistemic agency as curiosity is, as Pablo explained:

Students [should] be allowed to express the fact that they don’t know, because I think that there are sets of anxieties and a sort of malaise that I think is already there. […] And I think that the classroom could be a space in which we can say I ‘actually, I don’t know, and that worries me, and that makes me think that I have no hope’.

As Joe explained, epistemic agents have narrowly conceived specialisations within highly articulated domains (Millgram, Reference Millgram2015; Lumsden & Ulatowski, Reference Lumsden and Ulatowski2019). Hyperspecialists not only acquire content but acquire how to do their job correctly, accurately, and sincerely. Yet, a challenge arises when we miss important context clues because other people don’t communicate the way we do. We fail to speak the same language.

In our conversation, we discussed the context of polarisation and division in which we live and the lack of public debate about controversial issues that surprisingly comes with it. In this context, we tend to rely upon how we feel about matters over what the facts tell us in areas with which we are unfamiliar. This divisiveness leads to the opposite of education, to the opposite of the free-flow of ideas. Marta stated, “If we know that something is going to be very controversial, then we don’t talk about it and this is so, so dangerous for democracy really”. Controversies tend to be avoided in polarised epistemic communities, ultimately abandoning free speech and fundamental democratic principles. People tend only to look for evidence that conforms with their pre-existing opinions. This confirmation bias inhibits our epistemic agency.

As university educators, we also recognised our limits to encourage our students to become epistemic agents, as they are free to deflect the evidence that we provide or to reject facing the challenges associated with critique, including emotional challenges. As Joe explained:

I may find something deeply attractive, emotionally attractive, as you might say, but realise that after looking around it’s something I shouldn’t hold because there’s lots of disconfirming pieces of evidence and you just have to learn to give up on that piece of information. That’s the kind of humility that you have to exercise.

If we do that, then we may be more apt to consider the evidence that turns out to show our view to be false, exhibiting the epistemic humility needed to address the metacrisis. We turn now to consider specifically how we act in our work to support our thinking about epistemic humility and agency.

Pedagogy as action in the metacrisis

We now consider our pedagogical responses to epistemic humility and agency and introduce the idea of action humility. Our notion of action humility is based on our belief that teaching is what Marta called “a political commitment” in the metacrisis. The metacrisis demands that we do things differently, that these actions are grounded in critical thinking and epistemic humility and that we connect our work as educators to this political project.

For all of us, critical thought is a hallmark of epistemic humility, a core part of our pedagogical work and a necessary step towards action humility. Marta recounted her recent experience at a teacher conference where private companies offered workshops in which they marketed their resources to teachers attending “and the whole message was ‘you don’t need to think, other researchers and experts have done all the work for you and now everything is ready for you to use’”. She was “horrified because that’s just the opposite of what I want for a teacher, [which is] that they think!”. In her interview, she explained that in her teacher education classes encouraging critical thinking means “denaturalizing and historicising” our taken-for-granted assumptions about the curriculum and that students “understand that education is political”. Similarly, Chris understands that a crucial part of his work is to help “students realise that they themselves might have to question” their knowledge as we, as educators, model that we “are constantly questioning our own views about a variety of matters”, what Pablo described as the problematisation of assumptions about “what education could be or should be”.

For Joe, a challenging part of his pedagogical work is to communicate clearly and with any certainty about what is known. As he argued, this challenge has made “people reconsider experts as a source of beliefs and left us open to the idea that people, with little or no expertise, who have strong views on matters, should be taken seriously”. This has led to a rise in misinformation and disinformation though which humility regarding knowledge disintegrates, and power is usurped by those who appear certain but often not knowledgeable. For university educators, this creates a quandary in a space where the performativity discussed earlier influences student and institutional expectations of the process and outcomes of education, which can privilege simple transaction of knowledge and inhibit critical thought (Seatter & Ceulemans, Reference Seatter and Ceulemans2017).

In the teacher education space, Chris drew on the interplay between structure and agency (Archer, Reference Archer1996) to engage in “a lot of time talking to the pre-service teachers about when they’re teaching their own students, they’ll be some barriers that they will come across. So, we talk through some of the strategies and some of the considerations that they may have to face”, when working with their own students on socio-ecological challenges. As we all agreed, this overt engagement with issues like social inequality, neoliberal politics and climate change is crucial if our future generations are to develop agency to bring about change. Epistemic humility requires us to support our students to perforate the epistemic bubbles which lock us into ways of thinking that contribute to reproducing inequalities and the current metacrisis.

We see action humility is associated with the use of strategies that allow for an ethical and political response to happen, no matter how small, and despite the barriers. In his interview, Chris discussed how this action requires strategy, “like knowing what you can do and what will make a difference and also understanding what you may not be able to do at that time. That’s just deciding where to put your energy so that you’re able to make a difference in some way”. As a university educator in environmental education for 20 years, he was clear that “you have to look after yourself. And I think anybody who’s going to address the metacrisis has to bear that in mind”, especially as we have all been contributors to “many of the challenges which have led to the metacrisis” to various extents ourselves.

Action humility then relies on being honest about our contribution, and being committed to act personally and professionally to make a difference. As Pablo articulated, “I find that the metacrisis is putting into question the sense of future. I think it’s already changed, it’s already undefined. And I think that we need to be able to live within that…”. The metacrisis demands we deal with a set of questions and dilemmas that are not easily answered. Exposing this state of uncertainty – about our understanding of the world as well as about how to live with/in it - is an action pedagogy of humility.

Discussion and implications for environmental education in higher education

We stand on the precipice of a set of intersecting socio-ecological challenges which threaten our world. We are now in the Anthropocene, a period of time when human activity is having deep and potentially irreversible impacts on this planet Earth and all who inhabit it. Climate action is perilously slow, as witnessed at the just concluded Conference of Parties 30 in Brazil, where the outcome was “a very minimal basis for global climate action, and “the pace remains far too insufficient to meet the urgency of the climate crisis” (European Parliament, 2025), as major nations and oil producers stalled for more time. Environmental degradation is disrupting social cohesion, acerbating cultural loss, and destabilising economic structures. This metacrisis is creating a hostile environment; hostile for humans and for all other species.

Our conversation focused on our response in higher education. We recognised Stein and Andreotti’s (Reference Stein and Andreotti2025) call to repurpose the inherited (and outdated) role of the university toward relevance and responsibility” (p. 130) to feed the recomposition of the world, and Tikly’s (Reference Tikly2025) argument to shift the narrative of neoliberalism that has driven universities to being complicit and conducive to an unsustainable world. Our conversation across our varied scholarly traditions proposed a response that centres around epistemic humility and action humility.

Environmental education opens the possibility for new ways of being. In our institutional context, this entails resisting or refusing performativity, promoting openness and critique for who we are, how we are engaging with the world, which “regimes of truth” (Foucault, Reference Foucault1980) are feeding this crisis, and who is benefiting (or not) from them. The actions of our teaching and research can, at least to some extent, resist the focus on pass rates and publication metrics and, instead, focus on exposing the “truths” that have led us to the metacrisis and on what can make a difference for all species on Earth. We believe this critique can foster intergenerational thinking and action between epistemic agents.

Epistemic humility entails a constant revision of what we know, including our deeper assumptions and beliefs, however painful this exercise might be. It is driven by genuine attempts to understand our world and the conditions that have led us to the irrationality of the metacrisis and the environmental collapse. Epistemic humility, as we conceive it, nurtures conversations that face controversy and polarisation, is open to multiple trajectories for change (Stein, Reference Stein2024) and an ecology of knowledges (de Sousa Santos, Reference de Sousa Santos2007) and seeks to dismantle hegemonic power and reconnect our work, ourselves, with society and the environment. Through the cultivation of this virtue, university education can contribute to challenge the “narratives of inevitability” (Snyder, Reference Snyder2017) that condemn us to the metacrisis, and help to articulate different futures.

Our higher education institutions – and us within them – are perpetuating the metacrisis through their conscious and unconscious systems that lock us into dominant hegemonies of societal progress based on economic growth and hyper-individualism. We do not see the perils of this walk as a reason for despair, but as a reminder to be mindful of our talk - of wishful thinking and soothing or exciting ideals, of better futures and solutions. Rather, epistemic humility opens the possibility to dwell in the unknown and in the potential to know, to assert it as a condition for thought and a liveable state of being; and sets the conditions for the possibility of that new ontology of ourselves as actors in pursuit of what we can come to think of as a just and healthy world.

Finally, only action can bring about change, and action humility begins with the recognition of our role within the system. Universities are not abstract entities. As bureaucracies, they tend to dissipate the ethical and political responsibility of individuals (Arendt, Reference Arendt1970), but they are institutions that operate through the actions of their members. We can contribute to the reproduction of their rules and norms, but also to their potential modification. This is where humble action can take place – in actions that reclaim space for unproductive and reflective conversation, for critique and for collective action. For environmental education in higher education, this means acknowledging the metacrisis, recognising its antecedents, reorienting or refusing performativity to embrace the regeneration of our socio-ecological world, and embedding epistemic and action humility in our practice.

Our conversations about the metacrisis in university education have elucidated a myriad of challenges that we face in our sector. Here, we have focused on some of them and concluded that humility must underpin approaches to addressing these challenges. This humility can help to re-position higher education as a force that contributes to socio-ecological change at this critical moment in time.

Acknowledgements

This article recognises the support that our institution, our colleagues and students provide in developing and challenging our ideas.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standard

There was no requirement for formal ethical approval of this study as there were no human participants other than the authors.

Author Biographies

Chris Eames is a Professor in the School of Education at the University of Waikato. He teaches pre-service teacher education and supervises many research students in environmental and sustainability education. His current research focus is climate change education, and specifically what curriculum could look like in this field in Aotearoa New Zealand and other countries. Chris is a national executive member of the New Zealand Association for Environmental Education and a founding member of the Aotearoa Climate Education Coalition.

Marta Estelles is Senior Lecturer in the Division of Education at The University of Waikato. Her research analyses educational policies, discourses, and curricula as sites of broader socio-political struggles aimed at shaping particular kinds of citizens. Her research draws from a variety of disciplines, including sociology of education, curriculum and policy studies, social theory, history, and philosophy. Her latest research, funded by the Spencer Foundation, explores the increasing confluence of safety and citizenship discourses in education. She is the author of The Safetyfication of Education: Neoliberalism, Psychopolitics and the End of Critical Education (Bloomsbury Academic, 2025).

Pablo del Monte is Lecturer in Education in the School of Education at the University of Waikato. His research analyses different forms of disadvantage in the field of education and explores the ways in which educational institutions can respond to social problems.

Joe Ulatowski is Senior Lecturer in Philosophy and Assistant Vice-Chancellor Sustainability at the University of Waikato. His areas of research interest span across areas in metaphysics and epistemology with a concentration on the nature and value of truth, and action theory. He is the author of The Identities of Action (Bloomsbury, 2026), Commonsense Pluralism about Truth (Palgrave, 2017), and editor of special issues on alethic minimalism and on “Truth without Borders,” featuring cross-cultural analyses of truth. With Robert Colter, he is the author of The Socratic Classroom (Bloomsbury, 2025) and a handful of articles in the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning.