I. Introduction

The integration of bank lending and market-based finance for corporations is central to a recurring policy debate, reflecting firms’ strong reliance—particularly among small and medium enterprises (SMEs)—on bank loans, worldwide but especially in Europe. While U.S. firms benefit from well-developed capital markets, European capital markets remain fragmented across countries, and fewer companies are listed or issue bonds. Enhancing access to market finance could broaden firms’ funding options and reduce their dependence on bank loans, alleviating credit constraints and supporting investment and growth. Policymakers have pursued various initiatives to remove regulatory obstacles to the use of market finance, such as the 2012 JOBS Act in the United States and the Capital Markets Union plan in the European Union (EU Commission (2020), EU Council (2024), and European Central Bank (2024)).Footnote 1 Given firms’ financing needs, assessing the effects of recent policy initiatives in Europe is important for drawing implications for future policy design.

Our study contributes to the academic and policy debate on the choice between bank lending and market finance by studying how first-time bond issuance affects firms’ financing conditions and performance. Using loan-level credit register data, we explore whether access to bond markets allows issuer firms to obtain better loan conditions from banks and how it affects their overall debt structure. These questions are particularly relevant for firms with no prior access to capital markets and that largely rely on bank loans.

Our analysis presents two main challenges: first, we need to identify an exogenous event that changes firms’ ability to obtain market funding, enabling previously ineligible firms to issue bonds; second, for a sample of issuer firms (treated), we must construct a counterfactual sample of non-issuer firms (control) with comparable ex ante characteristics.

A 2012 regulatory reform in Italy provides an interesting experiment well suited to studying the effects of first-time bond issuance and addressing the challenges outlined earlier.Footnote 2 The reform removed existing limits on bond issuance by unlisted firms, provided that the securities are traded on a regulated market or a multilateral trading facility reserved for professional investors, and extended the favorable tax treatment previously granted to listed firms. Since these new bonds were expected to be relatively small, they became known as “minibonds.”

We exploit this reform to examine the impact of the first minibond issuance on bank lending conditions applied to issuer firms and on their performance. To this end, we perform a difference-in-differences (DID) analysis at both the firm–bank and firm levels. To build the counterfactual sample of non-issuer firms, we implement a coarsened exact matching procedure on a broad set of pre-issuance characteristics, including balance sheet variables, financing conditions, and investment opportunities. Our data set combines multiple sources. We collect minibond data from the Italian Security Register Database (Bank of Italy), integrated with information from Borsa Italiana (the Italian Stock Exchange in Milan). We merge these data with loan-level information from the Italian Credit Register (Centrale dei Rischi) and the Bank of Italy’s survey on lending rates, as well as with firms’ balance sheet data.

The DID analysis shows that, after the first minibond issuance, issuer firms experience a decrease in bank loan rates: at the firm level, rates decline by 27 basis points (bps) for long-term loans, 13 bps for advances, and 20 bps for overall loans in the 2 quarters following issuance. The analysis of loan volumes shows that issuer firms partially substitute bank loans with minibonds, reducing used loans by 42% at the firm level. The decline in granted loans for issuer firms is smaller (11%) and not statistically significant. Taking both effects into account, issuer firms reduce the ratio of used to granted loans—a common proxy for credit constraints—by 10 percentage points (pp). Including minibond amounts, issuer firms increase their total financial debt by 62%.

This evidence is confirmed by a staggered DID analysis: issuer firms obtain a progressively larger decrease in bank loan rates in the quarters following issuance, along with the largest decline in used bank loans at the end of the issuance quarter, followed by a smaller yet persistent decrease thereafter. The findings are robust to a wide range of checks, including a propensity score matching as an alternative matching strategy; an analysis of treatment intensity based on the ratio of minibond issuance amount to existing used bank loans; alternative estimation windows; and subsamples based on firm size, location, and bond maturity.

We explore the channels behind the reduction in bank loan rates. First, we examine whether first-time bond issuance serves as a public information signal, benefiting outside banks without previous relationships with the firm. We find no evidence that outside banks reduce loan rates to issuers more than inside banks, consistent with the reform’s design, which entailed limited information disclosure.

Second, since bank loans are senior to bonds, we study how the change in the seniority structure of corporate debt due to minibond issuance affects bank loan conditions. In our analysis, firms that increase their total financial debt to a larger extent through minibonds obtain greater reductions in bank loan rates, suggesting that the associated increase in assets serves as collateral and reduces credit risk for banks as senior lenders (Merton (Reference Merton1974), Hackbarth, Hennessy, and Leland (Reference Hackbarth, Hennessy and Leland2007)).

We then test whether access to bond markets strengthens issuers’ bargaining power with relationship banks. Issuer firms that are ex ante more reliant on their main bank tend to obtain larger loan rate reductions, consistent with reduced hold-up; however, once controlling for bond issuance size, the debt seniority effect appears to dominate the bargaining power explanation.

We further investigate whether improved financing conditions affect firm performance. A DID analysis of key indicators of balance sheet composition, turnover, and profitability shows that, after their first minibond, issuer firms increase turnover, total assets, and fixed assets—particularly intangible assets—and raise leverage, while reducing the share of bank loans in total financial debt. Since the matching procedure controls for investment opportunities, these findings suggest that issuer firms use minibond proceeds to support internal growth and investment.

Our study contributes to the literature on firms’ capital structure, particularly the choice between bank loans and corporate bonds and the effects of changes in capital structure on firms’ financing costs.Footnote 3 In the theoretical literature on capital structure, beyond the choice between equity and debt, several studies explore the firm characteristics that shape the composition of debt between bank loans and bonds (Diamond (Reference Diamond1991), Besanko and Kanatas (Reference Besanko and Kanatas1993), Boot and Thakor (Reference Boot and Thakor1997), Holmström and Tirole (Reference Holmström and Tirole1997), and Bolton and Freixas (Reference Bolton and Freixas2000)). Structural models of default risk (Merton (Reference Merton1974)) analyze the value of corporate debt as a function of firm asset value and capital structure. Hackbarth et al. (Reference Hackbarth, Hennessy and Leland2007) further develop the trade-off theory (Leland (Reference Leland1994)) to study debt composition for strong firms (using both bank loans and corporate bonds) and weak firms (using only bank loans), and to show the optimal priority of bank loans over bonds.Footnote 4

In the empirical literature, various studies examine the determinants of public bond offerings, mostly by large U.S. firms (Denis and Mihov (Reference Denis and Mihov2003), Faulkender and Petersen (Reference Faulkender and Petersen2006), Hale and Santos (Reference Hale and Santos2008), and Rauh and Sufi (Reference Rauh and Sufi2010)), including work analyzing the impact of policy measures supporting corporate bond markets (Darmouni and Siani (Reference Darmouni and Siani2025)). Some studies investigate the effects of changes in capital structure due to equity IPOs (Pagano, Panetta, and Zingales (Reference Pagano, Panetta and Zingales1998), Schenone (Reference Schenone2010), and Saunders and Steffen (Reference Saunders and Steffen2011)). Previous research analyzes the effects of bond issuance on firms’ financing costs, focusing on U.S. listed firms (Santos and Winton (Reference Santos and Winton2008), Schwert (Reference Schwert2020)). Hale and Santos (Reference Hale and Santos2009) examine the information release when listed firms enter the public bond market.

Darmouni and Papoutsi (Reference Darmouni and Papoutsi2025) document the recent rise in bond financing among midsize firms in the Euro Area, while Iannamorelli, Nobili, Scalia, and Zaccaria (Reference Iannamorelli, Nobili, Scalia and Zaccaria2024) study the motivations for bond issuance by Italian firms as a signal of credit quality to external stakeholders. The credit crunch during the global financial and sovereign debt crises likely intensified the need for market finance in Europe (Becker and Ivashina (Reference Becker and Ivashina2014), (Reference Becker and Ivashina2018)). Balloch (Reference Balloch2024) examines the macroeconomic spillovers of the liberalization of convertible bonds for listed firms in Japan in the 1980s. In our study, by exploiting a deregulation reform primarily targeting SMEs, we examine the benefits of bond market access for unlisted firms that rely almost exclusively on bank loans as a source of external finance. We show that these firms obtain lower bank loan rates, ease credit constraints, and are able to expand investment—particularly in intangible assets—and turnover.

Our study also relates to the literature on firm–bank lending relationships. While firms benefit from established lending relationships (Diamond (Reference Diamond1984), Petersen and Rajan (Reference Petersen and Rajan1994), and Bolton, Freixas, Gambacorta, and Mistrulli (Reference Bolton, Freixas, Gambacorta and Mistrulli2016)), they may also be subject to hold-up: incumbent banks can exploit their informational advantage to extract monopoly rents (Sharpe (Reference Sharpe1990), Rajan (Reference Rajan1992), and Von Thadden (Reference Von Thadden2004)). This may explain firms’ decisions to switch lenders (Ioannidou and Ongena (Reference Ioannidou and Ongena2010)) or to increase the number of banking relationships (Farinha and Santos (Reference Farinha and Santos2002)).

We study the shift from bank lending to market finance and find some evidence that issuer firms that are ex ante more reliant on their main banks benefit from larger loan rate reductions. However, when comparing different mechanisms, we show that the post-issuance decrease in bank loan rates is mainly driven by the change in the debt seniority structure after bond issuance: since bank loans are senior to bonds, the increase in assets available as collateral to senior lender banks reduces the risk of bank loans and, consequently, the loan rates offered to issuer firms.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section II presents the institutional background and stylized facts on minibonds. Section III introduces the data and empirical strategy. Section IV presents the results at the firm–bank level, while Section V discusses the analysis at the firm level. Section VI presents the staggered DID analysis. Section VII discusses additional robustness tests. Section VIII concludes.

II. Institutional Background and Stylized Facts

The regulatory reform introduced in Italy in 2012 aimed to promote corporate bond issuance by unlisted firms in a context of strong reliance on bank lending and limited access to capital markets (OECD (2015)). In June 2012, the so-called “Decreto Sviluppo” (Decree 83/2012, later converted into Law 134/2012) removed existing restrictions on bond issuance by unlisted firms (other than micro-enterprises), provided that the securities were traded on a regulated market or a multilateral trading facility. The reform also extended to minibonds the same tax treatment applied to bonds issued by listed firms, including tax relief on interest payments and issuance costs, as well as a preferential tax regime for investors’ interest income.

Following these regulatory changes, in March 2013 Borsa Italiana (the Milan Stock Exchange, part of the London Stock Exchange Group until October 2020 and now part of Euronext) created a dedicated multilateral trading facility, ExtraMOT PRO, open only to professional investors and offering unlisted firms a cost-effective market suitable for issuing and trading minibonds.Footnote 5 Listing requirements on ExtraMOT PRO are simplified compared with other bond markets: no prior approval from the financial market supervisory authority is required; issuers must publish only a simplified admission document and their latest audited financial statements; and credit ratings are not mandatory. This simplified regime for a market reserved to professional investors aimed to balance lower issuance costs for companies with adequate investor protection.Footnote 6

The favorable regulatory framework for minibonds was initially used also by relatively large unlisted firms. However, from the second half of 2013 onward, medium-sized and small enterprises increasingly raised funds through minibond issuances (see Figure C1 in the Supplementary Material). Between 2013 and 2019, about 30% of all companies issuing bonds for the first time in Italy used minibonds and, in terms of volumes, minibond issuances accounted for more than 40% of first-time issuances in Italy. For firms previously relying only on bank loans, minibonds also offered the opportunity to extend debt maturity profiles toward longer term funding.Footnote 7

III. Empirical Analysis

A. Data

The data set used in the analysis combines several data sources. Information on minibond issuances comes from the Italian Security Register Database (Bank of Italy), which covers both listed and unlisted bonds issued by Italian companies and institutions and is integrated with data from Borsa Italiana (the Italian Stock Exchange in Milan). In line with the reform’s requirements, we define minibonds as debt securities issued by unlisted firms and traded on regulated markets or multilateral trading facilities. Commercial paper with maturity below 1 year is excluded.

We focus on securities issued from 2013 to 2019, thereby excluding minibonds issued during the pandemic period. Although issuances remained robust at that time, many firms issued minibonds primarily for liquidity purposes, supported by public guarantees applicable to both loans and bonds, which may have altered the profile of issuers relative to previous years. We gather information on 540 minibonds issued by 275 firms from 2013 to 2019, for a total issuance amount of EUR 50.2 billion (Table 1). In the population of issuer firms (Table 1, Panel A), most bonds pay a fixed rate coupon (76.7%) of around 5%.

TABLE 1 Characteristics of Minibond Issuances

We obtain firms’ annual balance sheet data, Z-scores (Altman (Reference Altman1968)), industry classification, and headquarters’ location from the Cerved database.Footnote 8 By merging the bond issuance data with Cerved, we have balance sheet information on 232 issuers for the 2012–2021 period.

We use quarterly data on bank loans, including both granted and used loan amounts and the interest rates charged by banks in individual firm–bank relationships. Data on bank loans come from the Bank of Italy’s Central Credit Register (Centrale dei Rischi, CR). The CR covers all loans above EUR 30,000 and reports lender and borrower identities, as well as loan type (credit lines, advances, long-term loans). These loan contracts differ in design, collateral, and conditions.Footnote 9 Credit lines allow the borrower to draw funds up to a contractually predetermined limit and generally lack real collateral. Advances provide short-term lending against commercial credit claims held by the borrower toward third parties; repayment occurs as intermediaries collect payments on the underlying claims, which serve as collateral. Long-term loans, such as mortgages, have contractually determined maturities and are typically collateralized (mostly real, related to buildings, and sometimes personal collateral). Due to these collateral features, advances and long-term loans are senior relative to corporate bonds.

Data on bank lending rates come from the Bank of Italy’s Interest Rate Database, which reports the interest rates charged by a sample of over 200 banks operating in Italy, along with lender and borrower identities and loan type. Short-term interest rates (credit lines and advances) refer to all outstanding positions at a given date, while interest rates on long-term loans refer to newly granted loans in each quarter.

By merging data on bond issuances, firm balance sheets, and credit register information on loan amounts and rates, we obtain complete records for 216 issuer firms (prior to matching). We exclude financial firms (typically holding companies of industrial groups), as well as firms without balance sheet data or without bank relationships, around the time of issuance.

B. Identification Strategy

The Italian minibond reform provides a notable deregulation experiment to study the effects of access to debt capital markets on corporate financing conditions and performance. This applies primarily to unlisted firms, the direct beneficiaries of the reform, and particularly to SMEs. We exploit this reform to analyze the impact of the first bond issuance for issuer firms relative to ex ante similar non-issuer firms.

Among all unlisted firms potentially eligible under the new regulatory framework, only a limited number actually issued and listed minibonds on a regulated market or a multilateral trading facility. Therefore, when defining the control sample, we cannot rely on the universe of eligible firms but must select a sample of ex ante comparable corporations.

We allow the selection of issuer versus non-issuer firms to be driven by firm-level characteristics rather than by a purely random assignment. Firms decide whether to issue minibonds based on their financial conditions and forward-looking growth prospects. Such self-selection could bias our impact evaluation if these firm features—affecting issuance probability—are correlated with the outcome variables. We address this concern by implementing an exact matching procedure based on ex ante firm characteristics, restricting the analysis to comparable groups of issuers and non-issuers in a way consistent with the unconfoundedness assumption. This methodology extends the empirical approach developed by Ioannidou and Ongena (Reference Ioannidou and Ongena2010) to study switching behavior across banks.Footnote 10

We identify the matched control sample by considering observable firm-level features—prior to the first issuance—that are relevant for bank lending conditions and volumes. These include balance sheet variables, proxies for investment opportunities and creditworthiness, the type of main bank, and industry and location dummies (see the next subsection for details). By controlling for these ex ante characteristics, and conditional on them, treatment and outcomes can be assumed independent, allowing us to attribute post-issuance changes in loan conditions to minibond issuances. The large and heterogeneous population of eligible firms allows us to fulfill the overlap assumption: for almost 80% of treated firms with complete data, we can identify units in both the treatment and control groups for any setting of covariates.

We define ex ante and ex post outcomes considering only the first minibond issuance: even if some firms undertake multiple issuances over time, the first one conveys the initial signal to banks that a given firm can also obtain finance from debt capital markets. The analysis compares the 2 quarters before issuance (ex ante) with the issuance quarter and the following 2 quarters (ex post).

C. Treated and Control Samples

The pool of potential control firms includes all Italian firms with turnover and total assets of at least EUR 2 million (as for issuer firms) at the beginning of the sample period, and reporting balance sheet information in the Amadeus-Bureau van Dijk database (around 35,000 firms). Within this sample, we define the control group by matching firms’ characteristics in the year before the first issuance.

We apply coarsened exact matching (CEM), which requires matching on all characteristics relevant for the control sample. By design, CEM removes the imbalance between treated and control firms for a given level of coarsening chosen for relevant observable firm characteristics. In contrast, propensity score matching (PSM) identifies matched entities based on the expected probability of treatment, computed over an overall set of characteristics, without guaranteeing exact matching on all criteria.

CEM has been shown to outperform alternative matching methods in reducing imbalance between treated and control groups (Iacus, King, and Porro (Reference Iacus, King and Porro2011)). This advantage makes it preferable for our study, as it helps address the potential endogeneity of firms’ issuance decisions. CEM is applied to both categorical and continuous variables; continuous variables are grouped into discrete intervals, determined either by economically relevant categories (e.g., firm size class) or by the distribution of covariates in the sample (e.g., investment measures or interest rates). For robustness, we also run PSM using the same covariates as in CEM.Footnote 11 The results based on PSM confirm the findings obtained with CEM (see Section VII.B and Supplementary Material Appendix F).

Since the treatment (i.e., the first minibond issuance) occurs at different times across firms, we apply the CEM procedure separately for each year using firm characteristics observed in the year preceding the first issuance. Each control firm is then assigned the same event time as its matched treated firm.Footnote 12

Among the pre-treatment characteristics, we consider:

-

1. At least one bank loan in the pre-treatment year and no bond issuance.

-

2. Total assets (three classes): less than EUR 10 million; EUR 10–43 million; greater than EUR 43 million (following the EU classification of firms as small, medium, and large).

-

3. Economic activity (five classes): i) agriculture and fishing; ii) manufacturing industries; iii) non-manufacturing industries (mining, electricity, gas); iv) construction; v) services.

-

4. Firm location (three areas): north, center, and south.

-

5. Firm credit risk (two classes): low risk (Z-score between 1 and 4); medium and high risk (Z-score between 5 and 9).

-

6. Leverage ratio (two classes): up to 50%; above 50%.

-

7. Ratio of total fixed assets to total assets (average over the previous 3 years, five classes).

-

8. Investment rate (average growth rate of total fixed assets over the previous 3 years, 10 classes).

-

9. Size of the main bank (two size classes): bank total assets above or below EUR 26 billion; the main lender bank is defined as the bank from which the firm receives the largest share of loans (out of total used bank loans) in the year before issuance.

-

10. Average firm-level interest rate on bank loans (weighted average across all loan contracts in the year before issuance, eight classes).

The matching criteria, particularly 7 and 8, account for firms’ investment opportunities prior to treatment. Firms with higher growth trajectories are more likely to have higher financing needs—and hence issue bonds—and could benefit from more favorable bank lending conditions. To address potential self-selection based on investment opportunities, we include indicators of both the level and growth rate of investment in the pre-treatment period.Footnote 13

The matching variables also capture credit risk: in addition to balance sheet indicators (leverage, Z-score), we consider a market-based measure—the weighted average interest rate on existing bank loans at the firm level—which reflects banks’ ex ante pricing of borrower risk. Moreover, information barriers may play some role in firms’ financing decisions, by limiting the diffusion of information about new funding opportunities like minibonds. Given the limited contacts of unlisted firms with investment banks, their main relationship bank may influence their awareness of, or advice regarding, minibond issuance.Footnote 14 We therefore include the size of the main bank among the matching criteria.Footnote 15

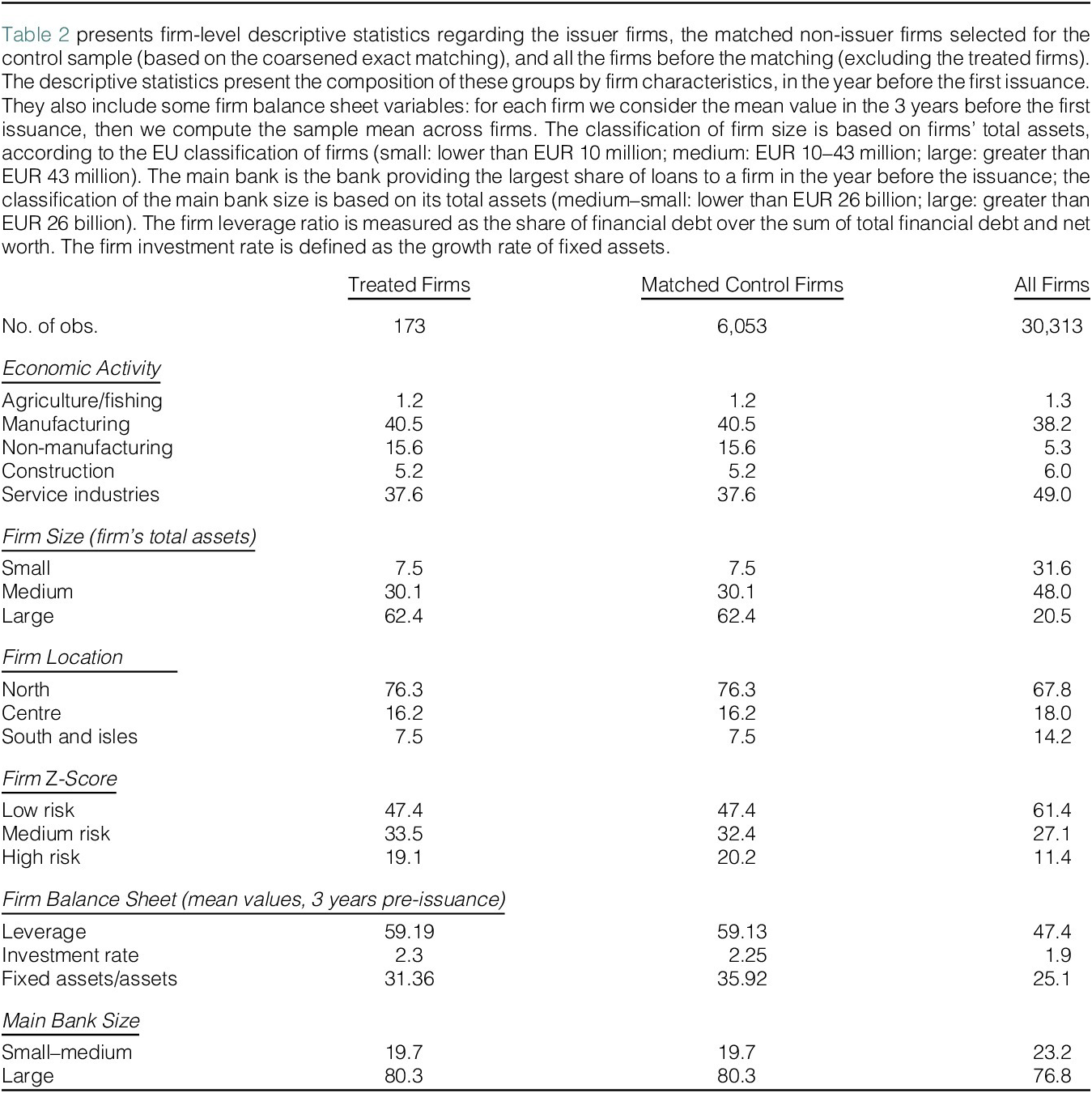

We are able to match 173 treated firms (more than 80% of all treated firms with complete data) with 6,053 control firms (Table 2). On average, each treated firm has 34 control firms, though the distribution is positively skewed, with a median of 13 controls per treated firm (see Tables D2 and D3 for details).Footnote 16 For robustness, we also run propensity score matching using the same selection variables, with a varying number of matched control firms.

TABLE 2 Characteristics of Minibond Issuers and Control Firms: Firms’ Composition and Balance Sheet Data

By construction, treated and matched control firms display the same distribution across categorical matching variables (economic activity, location, and size class) and negligible differences across coarsened variables (leverage ratios, Z-score, investment rates). Issuer and matched non-issuer firms are concentrated in manufacturing and services, based in Northern Italy, and are mostly medium- or large-sized firms by total assets; they primarily rely on a large bank as the main lender (Table 2). Compared with the full population of firms (excluding treated firms), matching substantially reduces the imbalance between treated and matched control groups on all criteria. Among matched issuer firms, 80% issued fixed coupon bonds, with an average coupon rate of 4.8% for the first minibonds (Table 1, Panel B).

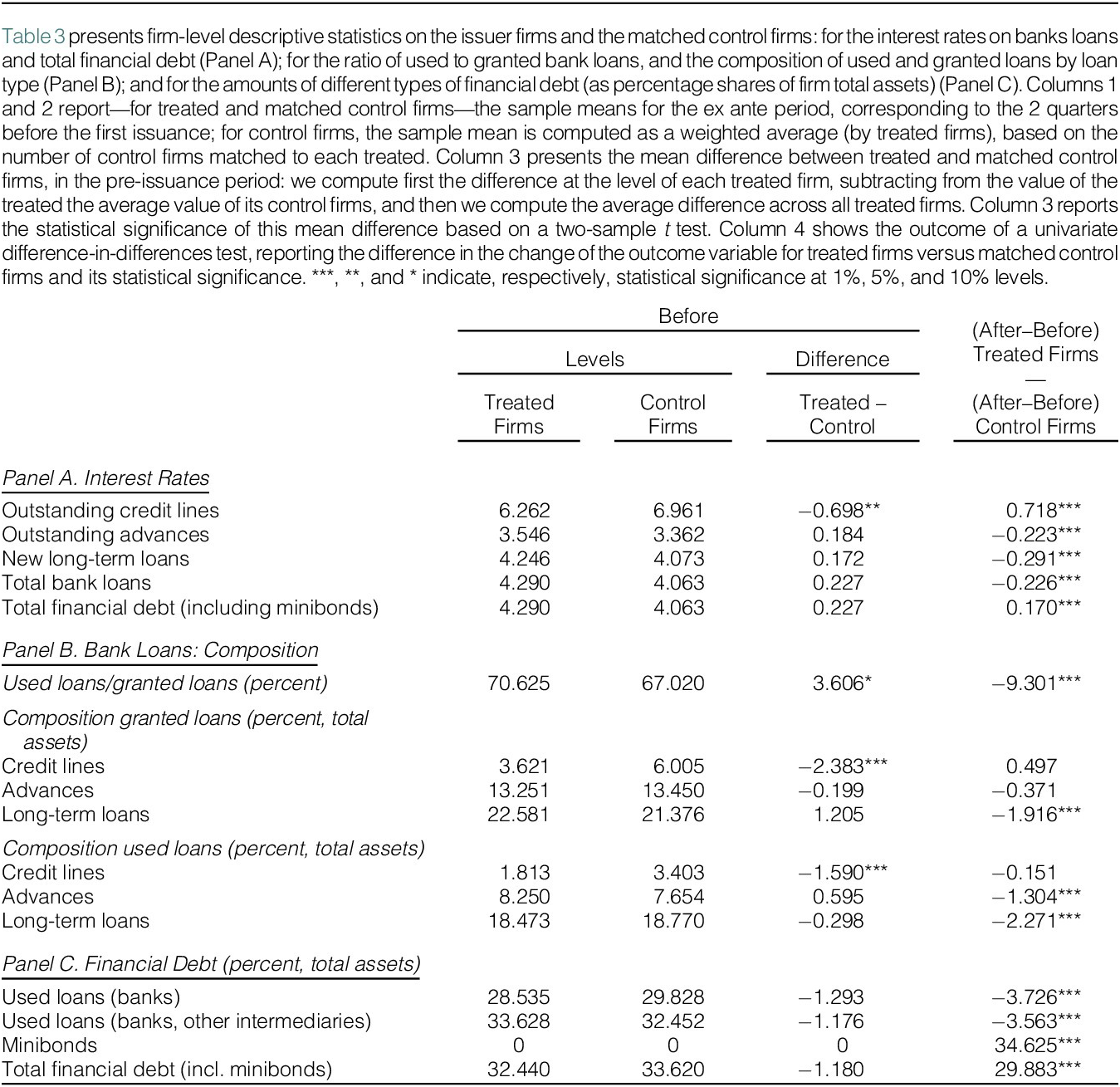

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics on interest rates, bank loans, and total financial debt. The analysis defines the ex ante period as the 2 quarters before issuance and the ex post period as the issuance quarter and the following 2 quarters. Before issuance, issuer firms display an average bank lending rate of 3.55% on advances, 4.25% on long-term loans, and 4.29% on all existing bank loans (including credit lines, advances, and long-term loans) (Table 3, Panel A, column 1).Footnote 17 Small differences in ex ante bank loan rates between treated and control firms before issuance are not statistically significant for advances, long-term loans, or total bank loans (column 3), confirming the comparability of the two groups after exact matching. The univariate DID test (column 4) further shows that, after the first minibond, issuer firms experience a larger decline in bank lending rates for advances, long-term loans, and total loans, with differences in post-issuance changes across the two groups significant at the 1% level.

TABLE 3 Characteristics of Minibond Issuers and Control Firms: Interest Rates, Bank Loans and Financial Debt

In terms of bank loan composition, long-term loans and advances account for the vast majority of used bank loans. After issuance, firms experience an easing of credit constraints: the ratio of used to granted loans decreases substantially for issuer firms relative to control firms (Table 3, Panel B). Issuer firms also reduce the amount of used bank loans while significantly increasing total financial debt through minibond issuances (Panel C).

Finally, we test the common trend assumption underlying the DID approach. We check graphically whether the outcomes of treated and matched control firms follow parallel trends in the absence of treatment. We find evidence supporting a common trend before the first issuance for lending rates on advances and long-term loans, as well as for the ratio of used to granted loans, though not for lending rates on credit lines.Footnote 18 After issuance, the reduction in interest rates is evident for advances and long-term loans and strengthens over time, while the impact on the ratio of used to granted loans occurs immediately and then stabilizes, suggesting partial repayment of outstanding loans.

D. Difference-in-Differences Specification and Hypothesis Testing

Based on exact matching between issuer firms and ex ante comparable non-issuer firms, we apply a DID model to estimate the impact of the first minibond issuance on bank loan rates and volumes. In the firm–bank level analysis, the main dependent variables are: i) quarterly bank loan rates, classified by loan type—credit lines, advances, long-term loans—and for overall loans; ii) quarterly amounts of granted and used bank loans, the ratio of used to granted loans for overall loans, and amounts of used loans by loan type.

The analysis of the first set of dependent variables investigates whether minibond issuances allow firms to obtain lower bank loan rates than non-issuer firms. We examine three potential economic channels: i) the release of public information by firms issuing bonds; ii) the change in the seniority structure of corporate debt, which reduces the risk of (senior) bank loans relative to (junior) corporate bonds; iii) an increase in the bargaining power of issuer firms in their lending relationships with banks. The empirical analysis explores the contribution of each channel in explaining the observed effects of minibond issuances on firms’ financing conditions (theoretical background and empirical results are presented in Sections IV.B and V.B).

The second set of dependent variables examines whether, and to what extent, minibond issuances affect the volume of loans granted by banks or the amount of loans used by firms. The impact on used bank loans depends on the purpose of the issuance: firms may issue minibonds to replace bank loans with market funding or to finance new investment projects requiring additional resources. The impact on granted bank loans may instead reflect supply decisions, which can be either bank- or firm specific: a bank may adjust the amount of loans granted due to changes in its general lending policy or for firm-specific reasons (e.g., the firm’s creditworthiness or profitability). Since generalized changes in granted amounts across all firms are captured by bank and time fixed effects, the effect of minibond issuance on loans granted to a firm reflects the bank’s assessment of firm-specific factors.

Our main specification exploits panel data for individual firm–bank relationships, with outcomes defined as interest rates and loan amounts for each quarter and each firm–bank pair. The treatment is defined as whether firm i has issued minibonds (Minibond = 1). The dummy variable “Minibond” is interacted with the dummy “Post,” which equals 1 after the first issuance:

where i indicates the firm, j the bank, t the quarter, and T the year. We include firm (

![]() $ {\alpha}_i $

), bank (

$ {\alpha}_i $

), bank (

![]() $ {\delta}_j $

), and quarter (

$ {\delta}_j $

), and quarter (

![]() $ {\gamma}_t $

) fixed effects. The coefficient on the interaction between the first minibond issuance (Minibond) and the post-issuance dummy (Post) captures the average treatment effect of the first issuance on bank lending rates and volumes.Footnote 19

$ {\gamma}_t $

) fixed effects. The coefficient on the interaction between the first minibond issuance (Minibond) and the post-issuance dummy (Post) captures the average treatment effect of the first issuance on bank lending rates and volumes.Footnote 19

As control variables, we include annual firm-level characteristics: total assets (log), leverage, and Z-score, all measured with a 1-year lag. Regressions are weighted using CEM-strata weights, and standard errors are clustered at the firm level. The effect of minibond issuance is measured in the quarter of the first issuance and the following 2 quarters, relative to the 2 quarters before the event. As a robustness check, we also estimate the model using a longer sample—including 6 quarters after issuance—and the results are confirmed.Footnote 20

IV. Firm–Bank Level Analysis

A. Empirical Results: Post-Issuance Bank Lending Rates and Volumes

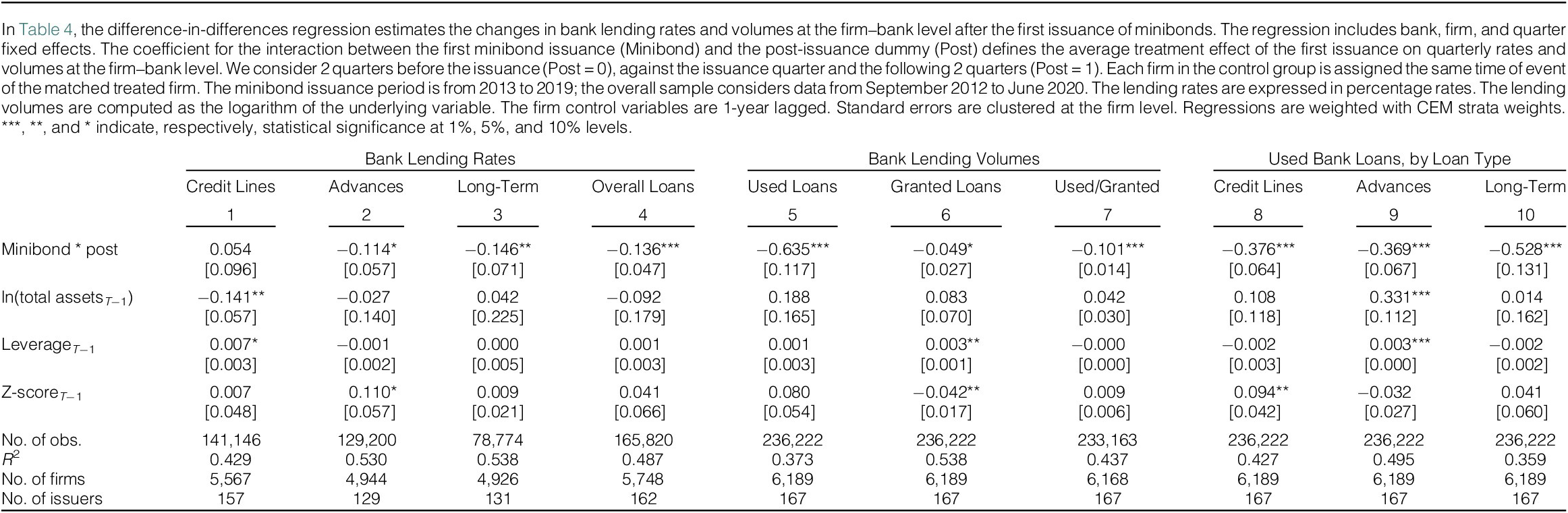

The main specification, as described in Section III.D, uses firm–bank level data on loan volumes and rates for each quarter, allowing us to control for firm, bank, and quarter fixed effects. Table 4, columns 1–4, presents the estimates of the impact on bank lending rates. The coefficient of interest (

![]() $ {\beta}_1 $

) is negative and significant for advances and long-term loans, as well as for overall firm–bank loans.Footnote 21 Lending rates decrease by 11 bps on advances, 15 bps on long-term loans, and 14 bps on overall loans; the effect on credit lines is not significant.

$ {\beta}_1 $

) is negative and significant for advances and long-term loans, as well as for overall firm–bank loans.Footnote 21 Lending rates decrease by 11 bps on advances, 15 bps on long-term loans, and 14 bps on overall loans; the effect on credit lines is not significant.

TABLE 4 Firm–Bank Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond Issuance on Bank Lending Rates and Volumes

Table 4, columns 5–7, reports the estimated effects on granted and used bank loan amounts. After the first minibond, issuer firms reduce used bank loans at the firm–bank level by 64%,Footnote 22 while the decline in granted bank loans is much smaller, only 5%. This suggests that even when firms repay bank loans with bond proceeds, banks remain willing to extend loans, reducing granted amounts only marginally. As a result, the ratio of used to granted loans falls by 10 pp.

Some heterogeneity may exist across firms: while some reduce used bank loans to substitute across funding sources, others may use minibond proceeds to finance new investment opportunities. In particular, during the early years of our sample, the sovereign debt crisis strongly constrained bank lending, making bond finance an important alternative source of external funding (Becker and Ivashina (Reference Becker and Ivashina2018)).Footnote 23 We further explore this point using firm-level data in Section V.A. The effects on loan rates and volumes are persistent over time and are confirmed in analyses over a longer ex post period of 6 quarters after issuance (Table E1 in the Supplementary Material).

B. The Decrease in Bank Loan Rates: The Mechanisms at the Firm–Bank Level

The decrease in bank loan rates following minibond issuances can be driven by several potential mechanisms, as discussed in Section III.D. In this section, we examine the hypothesis that the first bond issuance entails some public information disclosure: if so, outside banks could benefit from information previously accessible only to inside banks and might have an incentive to offer issuer firms better lending conditions than incumbents (Hale and Santos (Reference Hale and Santos2009), Schenone (Reference Schenone2010)). However, the strength of this information release effect likely depends on the extent of information actually disclosed through the issuance.Footnote 24

We investigate this hypothesis by exploiting heterogeneity between inside and outside lenders. Firm–bank loan-level data allow us to compare the lending behavior of different banks toward the same firm, depending on whether they have (inside) or lack (outside) a pre-existing lending relationship. Using a DID analysis with heterogeneous treatment, we study whether outside banks apply a larger post-issuance reduction in loan rates than inside banks. While the post-issuance decrease in bank loan rates is confirmed for advances and long-term loans, we do not find a statistically significant difference between outside and inside banks (Table E2 in the Supplementary Material).

Consistent with the limited information disclosure associated with minibond issuances, this evidence suggests that information release does not play a major role in explaining the decline in bank loan rates after the first minibond. The minibond initiative was designed to incentivize bond issuance by unlisted firms by minimizing fixed issuance costs; since only professional investors are allowed to purchase minibonds, disclosure requirements are less stringent than those for corporate bonds listed on regulated markets. These features indicate a lower informational value of the issuance compared with a bond IPO (Hale and Santos (Reference Hale and Santos2009)). Thus, the first minibond issuance may have a relatively limited information release effect, while still signaling publicly that a firm can access capital markets.Footnote 25 We further explore the economic channels behind the reduction in bank loan rates in Section V.B.

V. Firm-Level Analysis

In this section, we examine whether, and to what extent, minibond issuances improve the overall financing conditions and performance of issuer firms. We shift the focus from individual firm–bank relationships to the total bank loans received by each firm.

We study the impact of minibonds on bank loan rates and volumes at the firm level and additionally explore the effects on interest rates and the amount of total financial debt used by firms. We also investigate potential heterogeneity in the effects of minibonds across firms, depending on the increase in total financial debt and the strength of banks’ hold-up power.

A. Bank Loans and Total Debt: Rates and Volumes

Based on the described matching procedure, we conduct a DID analysis using the following specification at the firm level:

where i indicates the firm, t the quarter, and T the year. We control for firm

![]() $ \left({\alpha}_i\right) $

and quarter

$ \left({\alpha}_i\right) $

and quarter

![]() $ \left({\gamma}_t\right) $

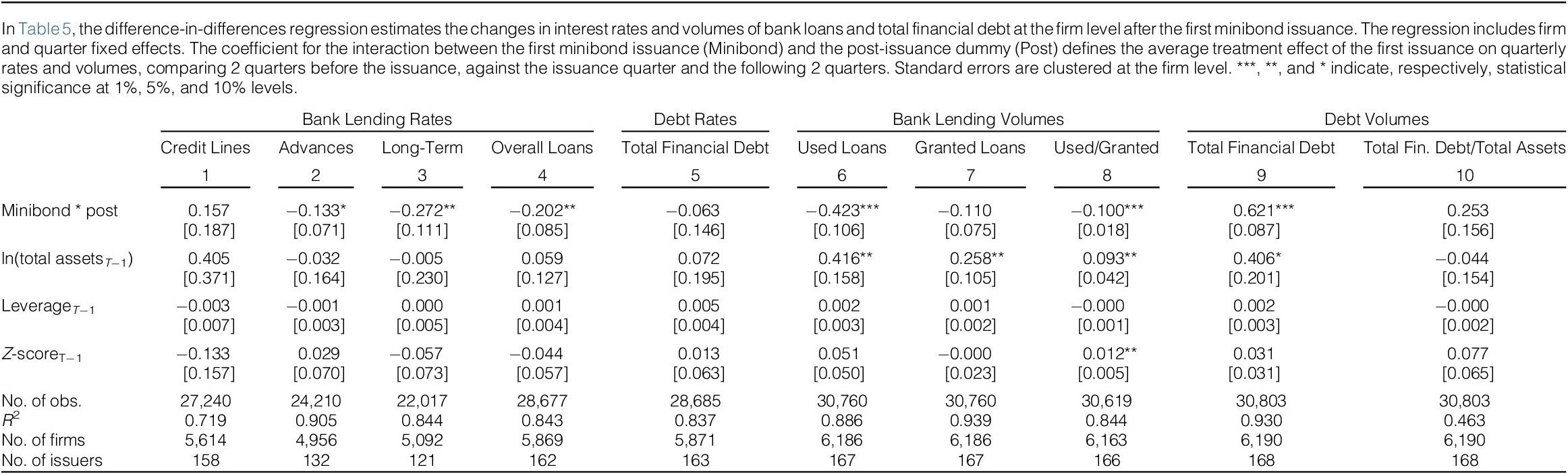

fixed effects. Table 5 presents the firm-level results, confirming the effects observed at the firm–bank level. Columns 1–4 show the results for bank lending rates: after the first minibond, issuer firms experience a decrease of 13 bps on advances and 27 bps on long-term loans. The average interest rate on overall bank loans falls by 20 bps.

$ \left({\gamma}_t\right) $

fixed effects. Table 5 presents the firm-level results, confirming the effects observed at the firm–bank level. Columns 1–4 show the results for bank lending rates: after the first minibond, issuer firms experience a decrease of 13 bps on advances and 27 bps on long-term loans. The average interest rate on overall bank loans falls by 20 bps.

TABLE 5 Firm-Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond Issuance on Bank Loan and Total Debt Rates and Volumes

We also examine interest payments on total financial debt (column 5). Despite the increase in financial debt due to minibonds, the average interest rate on total financial debt does not show a statistically significant change, with the coefficient pointing to a non-significant decrease of 6 bps. This suggests that the reduction in bank loan rates for issuer firms partially offsets the higher coupons on minibonds. It is worth noting that bank loans and minibonds differ in cash flow structure, seniority, and maturity; thus, costs based on par values may not be directly comparable.

Columns 6–8 report estimates for bank loan volumes at the firm level. Consistent with the firm–bank level analysis (Section IV.A), issuer firms reduce used bank loans by 42% after the first minibond, whereas granted bank loans show a smaller and non-significant decrease (around 11%). Consequently, the ratio of used to granted loans falls by approximately 10 pp.

We also analyze the overall debt position of issuer firms by including other financial debts and minibond issuances alongside used bank loans (Table 5, columns 9–10). Issuer firms increase total financial debt by 62%. The ratio of total financial debt to total assets displays a non-significant increase by 25 pp. The sizeable expansion in total financial debt—enabled by minibonds—occurs without a statistically significant change in its average interest rate; it is doubtful whether these firms could have reached the same result only relying on bank loans.

It is important to note that, while our analysis matches issuer and control firms before issuance, it remains an open question why some firms issued minibonds while similar firms did not. Firms may differ in investment opportunities, which could be recognized by lenders or investors. Our matching strategy addresses this concern by including indicators of pre-issuance investment opportunities for unlisted firms, capturing firms’ investment patterns prior to the minibond issuance.

B. The Decrease in Bank Loan Rates: The Mechanisms at the Firm Level

We examine two key potential channels at the firm level: i) changes in the debt seniority structure of issuer firms, and ii) increases in the bargaining power of issuer firms with their relationship banks. To study these mechanisms, we exploit heterogeneity across firms along two dimensions: the increase in total financial debt following bond issuance and the strength of pre-existing hold-up by banks.

1. The Seniority Structure of Corporate Debt

The issuance of bonds changes the seniority structure of corporate debt: as bank loans are senior to bonds, banks are repaid before bondholders (on the seniority structure of corporate debt, see Park (Reference Park2000), Hackbarth et al. (Reference Hackbarth, Hennessy and Leland2007), and Donaldson, Gromb, and Piacentino (Reference Donaldson, Gromb and Piacentino2025); for empirical studies, see Rauh and Sufi (Reference Rauh and Sufi2010), Cerqueiro, Ongena, and Roszbach (Reference Cerqueiro, Ongena and Roszbach2016, Reference Cerqueiro, Ongena and Roszbach2020)). In our setting, both long-term loans and advances are senior to bonds because they benefit from collateral: for long-term loans, mostly real collateral and occasionally personal; for advances, the credit claim from the underlying commercial transaction (see Section III.A and Table D1 on loan types).Footnote 26 This seniority is also reflected in interest rates: despite the limited comparability of bonds and loans on several features, in our sample, at the time of issuance, the coupons on first minibonds are on average higher than the lending rates on pre-existing bank loans.

In structural models of corporate debt (Merton (Reference Merton1974), Leland (Reference Leland1994), and Hackbarth et al. (Reference Hackbarth, Hennessy and Leland2007) for corporate debt with non-zero coupon), firms that issue bonds in addition to bank loans raise total financial debt and, in turn, expand the total assets that can serve as collateral to banks as senior creditors. This larger collateral can reduce the risk on bank loans, and consequently, lower bank loan rates. Accordingly, issuer firms with a larger increase in asset value due to bond issuances would be expected to benefit from a larger ex post decrease in bank loan rates.

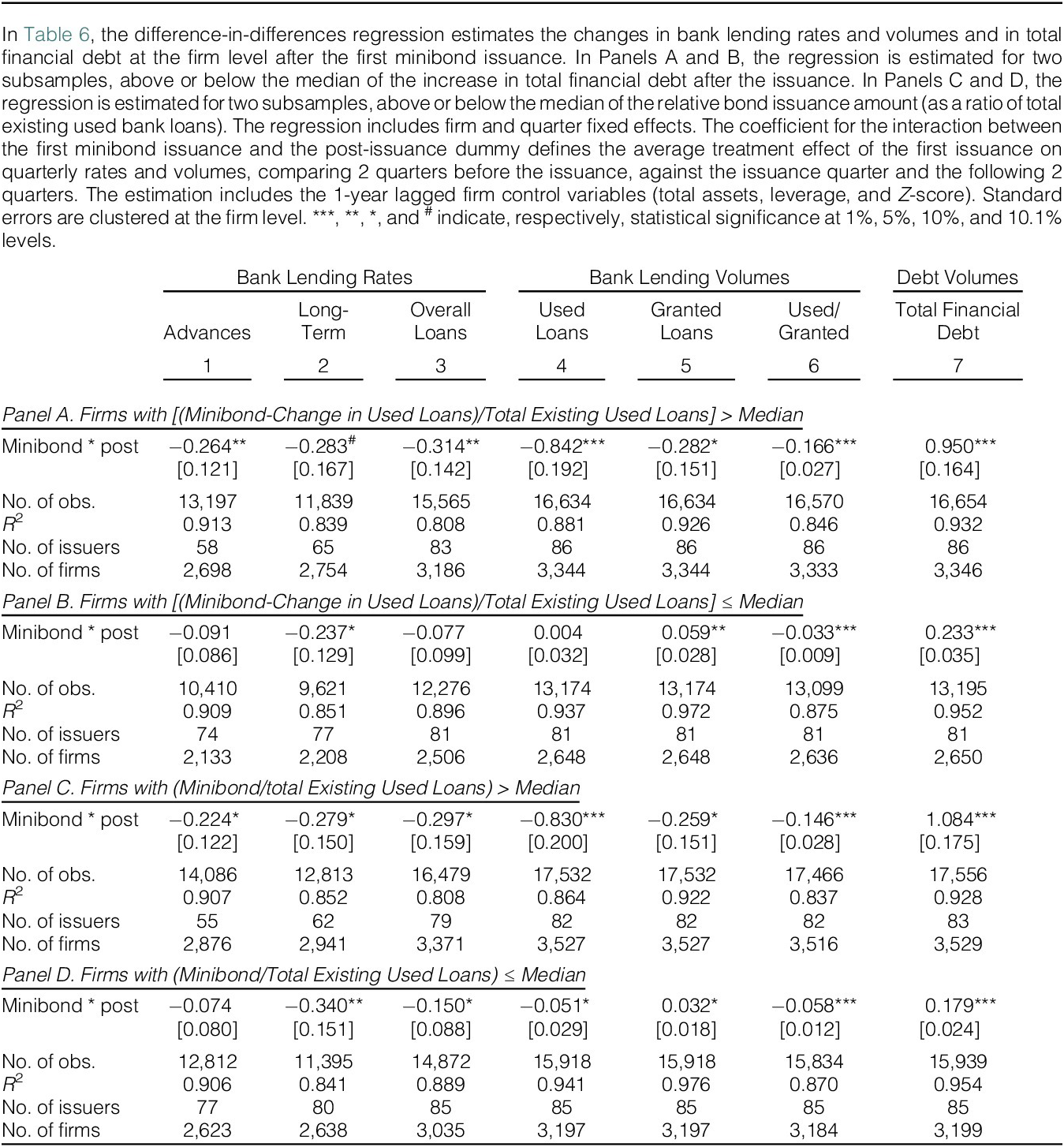

To test the debt seniority argument, we examine the change in total financial debt following minibond issuance. We construct this variable as a ratio, with the minibond issuance amount (net of changes in used bank loans) as the numerator and total existing used bank loans as the denominator.Footnote 27 This captures the extent to which issuer firms increase total financial debt—and consequently total assets available as collateral—after the bond issuance. We split the sample at the median of this ratio (54.9% in our sample) and report the results in Table 6.

TABLE 6 Firm-Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond: Firm Heterogeneity in Increase of Total Financial Debt

In the subsample above the median (Panel A), issuer firms with a larger balance sheet expansion experience a stronger reduction in bank loan rates: 26 bps on advances, 28 bps on long-term loans (significant at the 10.1% level), and 31 bps on overall loans. These firms also reduce used bank loans by 84% and granted bank loans by 28%, easing credit constraints (the ratio of used to granted loans decreases by 17 pp). In the subsample below the median (Panel B), issuer firms with a smaller balance sheet increase show no significant change in bank loan rates on advances and overall loans, while observing a 24-bps decline on long-term loans. These firms do not reduce used bank loans, increase granted loans by 6%, and experience a modest decrease in the ratio of used to granted loans of 3 pp.

This evidence indicates that issuer firms with a larger increase in total financial debt due to minibonds experience a stronger reduction in bank loan rates, as the higher amount of collateral assets reduces more the credit risk for banks as senior creditors. Overall, this supports the debt seniority structure argument in explaining the ex post decrease in bank loan rates.

In a complementary analysis, we examine the potential role of credit substitution resulting from minibond issuances. Across the overall sample, issuer firms reduce used bank loans substantially (42% at the firm level). However, heterogeneity in minibond amounts relative to existing used bank loans may affect the extent of this substitution. We study whether the effects of minibonds vary in relation to credit substitution. To explore this, we compute the ratio of the minibond issuance amount to total existing used loans (averaged over the 4 quarters preceding the issuance) and split the sample of first-time issuers at the median of this ratio (43% in our sample), with results reported in Table 6.

In the subsample above the median (Panel C), firms with larger minibond issuances exhibit stronger credit substitution, with a reduction in used bank loans of 83% and a decrease in the ratio of used to granted loans by 15 pp, indicating a pronounced easing of credit constraints. These firms also experience a decline in bank loan rates of 22 bps on advances, 28 bps on long-term loans, and 30 bps on overall loans. In the subsample below the median (Panel D), firms with smaller minibond issuances display limited credit substitution, reducing used bank loans by only 5%. Nevertheless, they still observe decreases in long-term loan rates of 34 bps and overall loan rates of 15 bps. These findings suggest that credit substitution plays a limited role in explaining the post-issuance reduction in bank loan rates.Footnote 28 The observed decline in lending rates can occur even when issuer firms do not reduce bank loans, provided that the increase in collateral value lowers the credit risk for lender banks as senior creditors.

2. The Bargaining Power of Firms with Lender Banks

We investigate whether access to bond markets strengthens the bargaining power of issuer firms with their relationship banks. This hypothesis is supported by the theoretical literature on hold-up by relationship banks due to informational advantages (Sharpe (Reference Sharpe1990), Rajan (Reference Rajan1992), and Santos and Winton (Reference Santos and Winton2008)). If firms are subject to hold-up, access to bond markets could relax funding constraints and increase their bargaining power with relationship banks, resulting in lower bank loan rates. Importantly, structural models like Hackbarth et al. (Reference Hackbarth, Hennessy and Leland2007) also predict that firms with high bargaining power issue both (senior) bank loans and (junior) bonds, whereas firms with little or no bargaining power rely solely on bank loans. In this context, a reform enabling access to capital markets could improve firms’ bargaining power with banks.

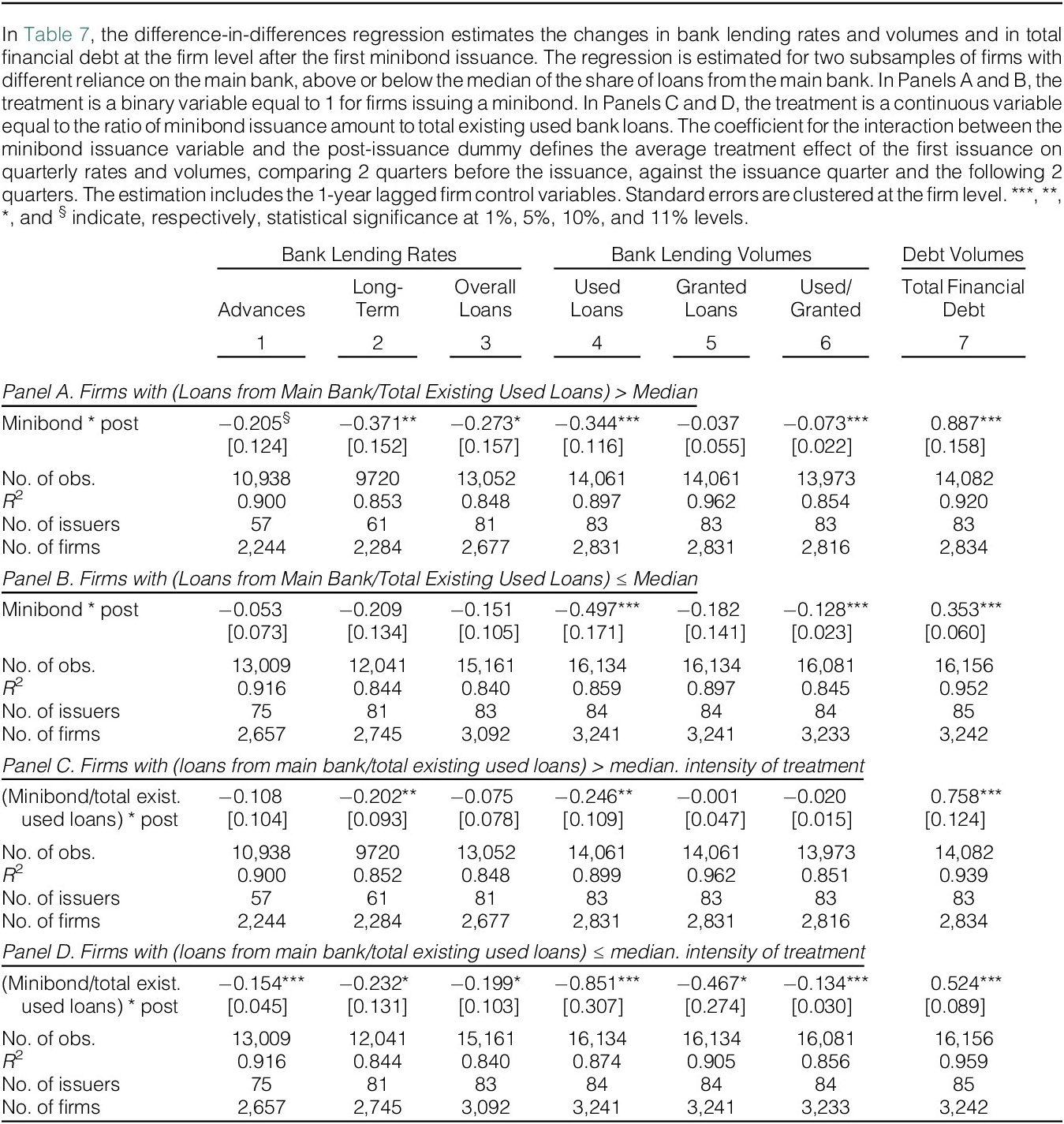

In our setting, minibond issuance may enhance bargaining power because it creates a credible threat that firms could partially replace loans from their relationship banks with minibonds. Banks might then have an incentive to retain creditworthy borrowers by offering more favorable loan conditions. To examine this channel, we exploit heterogeneity in the intensity of hold-up, proxied by the share of loans provided by the main bank relative to total used bank loans prior to the first issuance. The main bank supplies the largest share of a firm’s bank loans, and it is more difficult to replace its loans entirely with bonds; given its informational advantage, the main bank can exert the strongest hold-up power. Firms that are more reliant on their main bank could, after issuing minibonds, improve their bargaining position and secure better lending terms. Conversely, firms less dependent on their main bank are likely to benefit less from minibond issuance, as their bargaining power is already relatively strong and the hold-up effect on their loan spread is limited.

We compute the ratio of loans from the main bank to total existing used loans, averaged over the 4 quarters preceding the first issuance, and split the sample into two subsamples: below and above the median share of main bank loans (28.6% in our sample). The results are reported in Table 7 (Panels A and B). Issuer firms that were ex ante more reliant on the main bank (Panel A) experience a larger reduction in bank loan rates: 37 bps on long-term loans and 27 bps on overall loans. These firms reduce used bank loans by 34% and increase total financial debt by 89%. In contrast, firms less dependent on the main bank (Panel B) do not experience statistically significant changes in bank loan rates; they reduce used bank loans by 50% and raise total financial debt by 35%. These findings provide some evidence that firms more exposed to hold-up may benefit more from minibond issuance via larger reductions in bank loan rates. Notably, this effect emerges for more recent issuances, coinciding with a more developed minibond market.

TABLE 7 Firm-Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond Issuance: Firm Heterogeneity in Reliance on Main Bank

We also observe that firms ex ante more reliant on the main bank increase their total financial debt to a greater extent through minibonds. As discussed in Section V.B.1, a larger rise in total financial debt can increase total assets, and thus the collateral available to lender banks as senior creditors. Consequently, the greater reduction in bank loan rates for firms more dependent on their main bank may reflect a lower credit risk due to larger minibond issuances rather than an increase in bargaining power.

To disentangle these channels, we need to control for the size of minibond issuances. We replace the binary issuance variable with a continuous measure of relative issuance size, defined as the ratio of the minibond amount to total used bank loans, and estimate regressions for the same subsamples (Table 7, Panels C and D). For firms more reliant on their main bank (Panel C), a minibond issuance equal in size to existing used bank loans reduces long-term loan rates by 20 bps. For firms less dependent on their main bank (Panel D), an issuance of the same relative size reduces lending rates by 15 bps on advances, 23 bps on long-term loans, and 20 bps on overall bank loans. These results indicate that, after controlling for relative issuance size, there is only limited support for the bargaining power channel: ex ante more hold-up-exposed firms do not systematically experience larger reductions in bank loan rates. Overall, the evidence suggests that the debt seniority channel dominates the bargaining power mechanism in explaining the post-issuance decrease in bank loan rates for issuer firms.

C. Ex Post Outcomes: Firm Performance and Balance Sheet Indicators

The firm-level analysis suggests that minibond issuance improves firms’ financing conditions, enabling an expansion of overall financial debt while reducing reliance on bank loans. We now investigate whether these improved financing conditions translate into enhanced firm performance.

We estimate a DID model using firm-level data, where the dependent variables capture asset and liability composition, turnover, and profitability. On the asset side, we consider the log of total assets, fixed assets, and intangible fixed assets, as well as the ratio of total fixed assets to total assets. On the liability side, we analyze the ratio of bank loans to total financial debt and the leverage ratio. Additionally, we examine the log of turnover and return on assets (ROA) as a measure of profitability. Using annual financial statement data, we compare firm performance in the year before the first issuance and the two subsequent years,Footnote 29 employing the following specification:

where i indicates the firm and T the year, and

![]() $ {\mathrm{Post}}_{i,T} $

is equal to 1 in the 2 years following the first issuance and 0 in the year before. We include firm

$ {\mathrm{Post}}_{i,T} $

is equal to 1 in the 2 years following the first issuance and 0 in the year before. We include firm

![]() $ \left({\alpha}_i\right) $

and year

$ \left({\alpha}_i\right) $

and year

![]() $ \left({\alpha}_T\right) $

fixed effects.

$ \left({\alpha}_T\right) $

fixed effects.

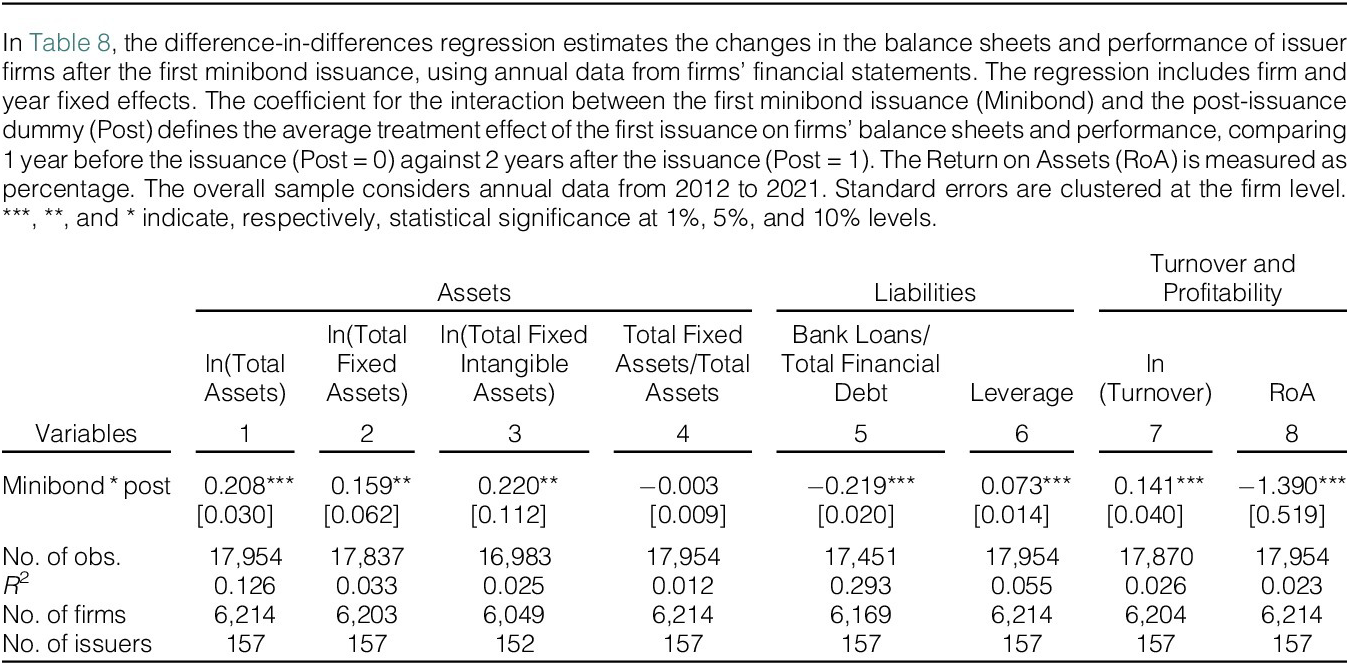

The results are reported in Table 8. Following the first minibond issuance, issuer firms experience a 21% increase in total assets (column 1), partly reflecting the rise in overall financial debt. These additional resources appear to be primarily allocated to investment: total fixed assets increase by 16% (column 2) and intangible fixed assets by 22% (column 3). While these increases could also reflect greater investment opportunities, we have designed our matching strategy to explicitly control for pre-issuance investment patterns in unlisted firms, including the ratio of fixed assets to total assets and the 3-year growth rate of fixed assets (Section III.C). Hence, we interpret these results as evidence that issuer firms utilize minibond proceeds to support internal growth and raise investments in fixed assets, consistent with theoretical and empirical findings on bond market access and firm investment (Crouzet (Reference Crouzet2018), Harford and Uysal (Reference Harford and Uysal2014)).Footnote 30

TABLE 8 Firm-Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond Issuance on Firm Ex Post Outcomes

On the liability side, the increase in total financial debt is reflected in a 7-pp rise in leverage and a 22-pp reduction in the share of bank loans in total financial debt. We also find a significant 14% increase in turnover over the 2 years following the first minibond, while profitability shows a 1.39-pp ex post decrease in RoA.Footnote 31

VI. Staggered Difference-in-Differences Analysis

We also conduct a staggered DID analysis to account for heterogeneous treatment timing in our sample, as firms issued minibonds at different points between 2013 and 2019 (Baker, Larcker, and Wang (Reference Baker, Larcker and Wang2022), Roth, Sant’Anna, Bilinski, and Poe (Reference Roth, Sant’Anna, Bilinski and Poe2023)). We implement the estimator proposed by Callaway and Sant’Anna (Reference Callaway and Sant’Anna2021) to evaluate the effects of the first minibond issuance over a time window spanning 4 quarters before and 4 quarters after each firm-specific issuance time.

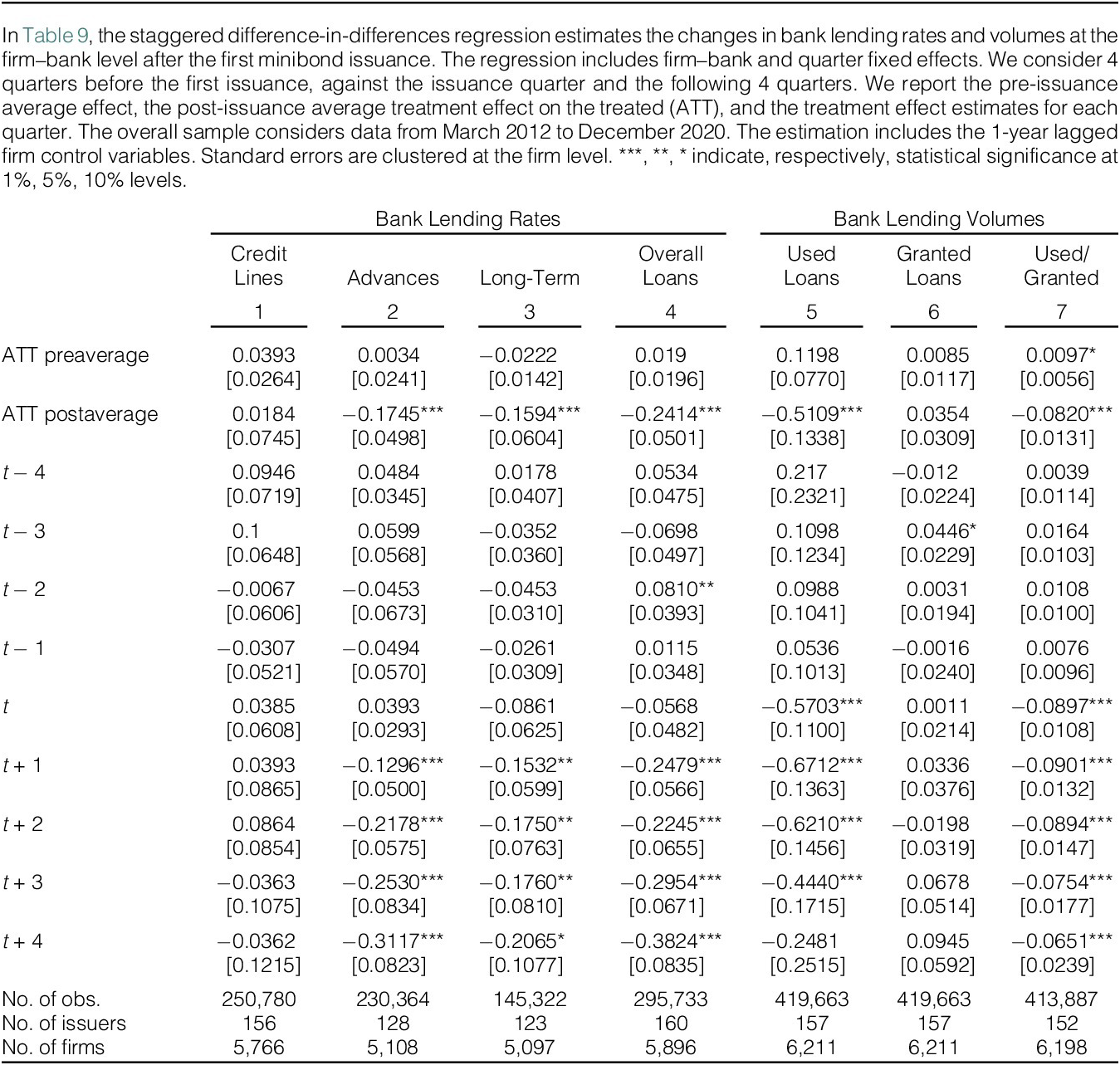

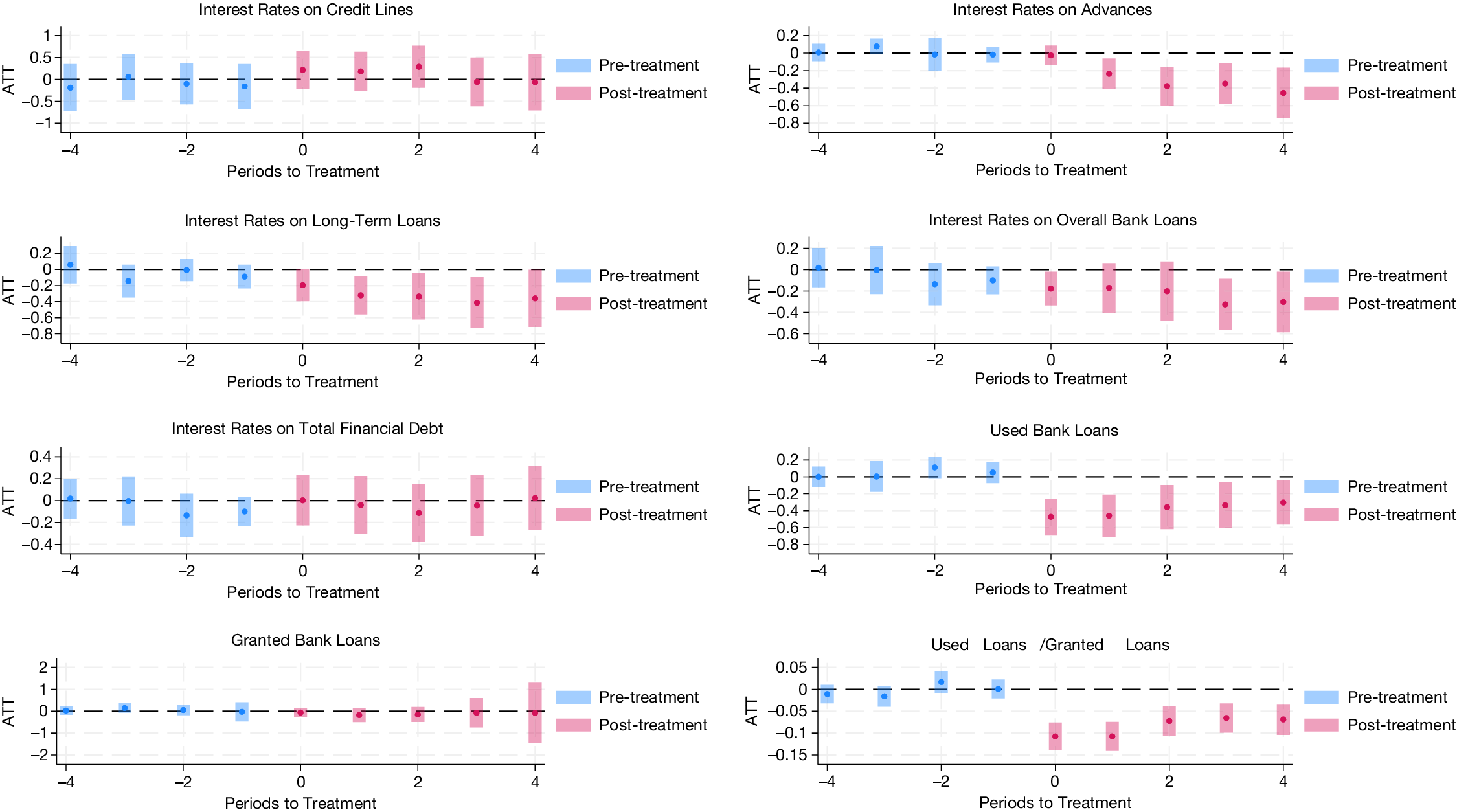

The firm–bank level results are presented in Table 9, and the firm-level results in Table 10. We report the pre-issuance average effect, the post-issuance average treatment effect on the treated, and the quarterly treatment effect estimates. To visualize the dynamics, Figures 1 and 2 show the point estimates and 95% confidence intervals of the analysis for interest rates, bank loan volumes, and total financial debt.

TABLE 9 Staggered Firm–Bank Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond Issuance on Bank Lending Rates and Volumes

TABLE 10 Staggered Firm-Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond on Bank Loan and Total Debt Rates and Volumes

FIGURE 1 Staggered Difference-in-Differences Analysis: Firm–Bank Level Estimates

Figure 1 shows the results of the staggered difference-in-differences analysis for the effects of the first minibond issuance on bank lending rates and volumes at the firm–bank level. The charts display the estimates for the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), as well as the 95% confidence intervals. Each chart shows the dynamics in one of the outcome variables over time, in a time horizon from 4 quarters before to 4 quarters after the firm-specific issuance time.

FIGURE 2 Staggered Difference-in-Differences Analysis: Firm-Level Estimates

Figure 2 shows the results of the staggered difference-in-differences analysis for the effects of the first minibond issuance on the interest rates and volumes of bank loans and total financial debt at the firm level. The charts display the estimates for the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), as well as the 95% confidence intervals. Each chart shows the dynamics in one of the outcome variables over time, in a time horizon from 4 quarters before to 4 quarters after the firm-specific issuance time.

At the firm–bank level (Figure 1 and Table 9), the estimates reveal a progressive decline in bank lending rates in the quarters following the first issuance. For advances, rates decrease from 13 bps in the first post-issuance quarter to 31 bps in the fourth quarter, with an average post-issuance effect of 17 bps. Long-term loan rates decline from 15 to 21 bps, averaging 16 bps over the post-issuance period. Overall loan rates fall from 25 to 38 bps, with an average effect of 24 bps. Concurrently, used bank loans drop sharply, falling by 57% by the end of the issuance quarter and by 67% in the first post-issuance quarter, before gradually stabilizing in subsequent quarters, with an average post-issuance reduction of 51%. The early and substantial decrease in used bank loans suggests partial substitution between minibonds and bank loans. This is accompanied by a loosening of credit constraints, as reflected in an average 8 pp reduction in the ratio of used to granted bank loans.

The firm-level analysis confirms these patterns. Bank loan rates progressively decline over time: for advances, from 24 bps in the first post-issuance quarter to 46 bps in the fourth, with an average ex post reduction of 29 bps; for long-term loans, from 19 bps at the end of the issuance quarter to 41 bps in the third quarter, averaging a 32-bps decline over the post-issuance period. Interest rates on overall bank loans decrease by an average of 24 bps. Simultaneously, used bank loans exhibit the largest reduction at the end of the issuance quarter (47%), gradually tapering to 30% by the fourth quarter, with an average ex post decrease of 39%. This trend is mirrored in the ratio of used to granted loans, which falls by 11 pp at the end of the issuance quarter and by 8 pp on average during the post-issuance period. Total financial debt increases steadily following the issuance, rising from 56% at the end of the issuance quarter to 79% in the fourth quarter, with an average ex post increase of 69%. These dynamics suggest that issuer firms initially substitute bank loans with minibonds, and subsequently expand their total financial debt.

Overall, the staggered DID estimation reinforces our main findings on the effects of minibond issuances: they reduce bank lending rates, lower bank loan usage, and increase total financial debt, while highlighting the evolution of these effects over time.

VII. Robustness Analysis

We conduct additional robustness analyses to ensure the validity of our findings. First, we re-estimate the baseline specifications using the intensive margin of minibond issuance—that is, the ratio of the minibond amount to total existing bank loans—rather than the binary indicator for the first issuance, to assess the impact on bank loan rates and volumes, and total financial debt. Second, we implement an alternative matching approach based on propensity score matching to verify whether the effects are consistent. Finally, we perform estimations on various subsamples, distinguishing firms by bond maturity, firm size, and geographic location.

A. The Intensity of Treatment

Beyond the issuance decision, the size of the issuance may influence the effects of minibonds. To capture this, we examine the impact of minibond issuances allowing for heterogeneous treatment intensity by replacing the binary variable for the first issuance with a continuous measure of the issuance amount, normalized by total existing used bank loans.

The results are presented in Table 11, at both the firm–bank level (Panel A) and the firm level (Panel B). At the firm level, a minibond issuance equal in size to existing used bank loans (i.e., a ratio of 1) reduces bank loan rates by 14 bps on advances and 19 bps on long-term loans, decreases used bank loans by 38%, and lowers the ratio of used to granted loans by 4 pp. It also increases total financial debt by 70%, while raising the average interest rate on total financial debt by 23 bps. This evidence suggests that larger minibond issuances relative to existing bank loans can substantially increase leverage, potentially raising the minibond coupon rate and the average interest rate on total financial debt.

TABLE 11 Firm–Bank and Firm-Level Analysis: Effects of the First Minibond Issuance: Relative Issuance Amount as Treatment Variable

At the firm–bank level, a comparable minibond issuance (equal to existing used loans) reduces used bank loans by 6% and the ratio of used to granted loans by 1 pp, and lowers rates on advances by 2 bps, but without statistically significant effects on long-term or overall loan rates.

For further robustness, we also consider the minibond amount in absolute terms (log of minibond issuances plus 1, to account for non-issuance). The results, reported in Tables E6 and E7 (Supplementary Material Appendix E), confirm that larger minibond issuances lead to greater reductions in bank loan rates, stronger decreases in used bank loans, and larger increases in total financial debt, both at the firm–bank and firm levels.

B. Propensity Score Matching

As an alternative matching strategy, we perform a propensity score matching (PSM) (see also Hale and Santos (Reference Hale and Santos2009)) to construct a sample of comparable control firms, with results reported in Supplementary Material Appendix F (Tables F1–F5). The propensity score is estimated based on the same firm characteristics used in the coarsened exact matching (CEM). The flexibility of PSM allows us to further refine the matching criteria, for example, using more granular classifications for firm location and industry. Control groups are identified via nearest neighbor or radius matching algorithms. After matching, we re-estimate the DID regressions on these alternative samples. The results based on PSM confirm the estimates obtained with CEM and remain robust to stricter matching criteria, different matching algorithms, and to the selection of a smaller number of matched control firms.

C. Further Robustness on Subsamples

We further test the robustness of our findings to heterogeneity in minibond characteristics and firm types. The firm-level analysis is reported in Table E8 in the Supplementary Material .

First, we examine bond maturity. A longer maturity profile of total debt, including long-term bonds, may signal lower firms’ risk to banks, potentially improving financing conditions; bonds with longer maturities, however, may also carry higher interest rates due to greater uncertainty. Results for minibonds with maturities of at least 5 years confirm the post-issuance reduction in long-term bank loan rates and the increase in total financial debt (Table E8, Panel A).

Second, we investigate heterogeneity by firm size, focusing on SMEs (defined by turnover below or equal to EUR 50 million), the primary target of the reform. SMEs exhibit an increase in total financial debt and a notable decrease in bank loan rates, comparable to the main findings. Importantly, the reduction in loan rates occurs even without credit substitution between minibonds and bank loans, since SMEs show no significant decrease in used bank loans, suggesting that SMEs mainly use minibonds to obtain additional funding for growth, in line with the purposes of the minibond reform (Table E8, Panel B).

Finally, we explore geographic heterogeneity, considering that the proximity to financial centers may foster information about market financing sources (Saunders and Steffen (Reference Saunders and Steffen2011)).Footnote 32 We consider a sample of firms located outside Lombardy (the region of Milan, the Italian financial center); our main results are confirmed for these firms as well (Table E8, Panel C).

VIII. Conclusions

This study examines the effects of access to debt capital markets—through the first issuance of bonds by unlisted firms—on their financing costs and debt structure, compared to ex ante comparable non-issuer firms identified via an exact matching procedure. We exploit a regulatory reform in Italy that enabled unlisted firms, previously reliant solely on bank loans, to issue corporate bonds, known as minibonds. Using firm–bank loan-level credit register data, combined with firm balance sheet and bond issuance information, we conduct a DID analysis for minibond issuances between 2013 and 2019, at both the firm–bank and firm levels.

Our firm-level results show that, following the first issuance, issuer firms experience a reduction in bank lending rates—27 bps on long-term loans, 13 bps on advances, and 20 bps on overall bank loans—while simultaneously adjusting their debt structure: used bank loans decrease by 42%, and total financial debt rises by 62%. These results are robust across various checks, including staggered DID estimation, treatment intensity measures, propensity score matching, alternative time windows, and subsample analyses by firm size, location, and bond maturity.

We exploit heterogeneity across banks and firms to explore the channels driving the reduction in bank loan rates. The effect is not driven by different lending behaviors by outside versus incumbent banks, consistent with the limited information disclosure of minibond issuances. Instead, the key factor is the change in debt seniority: since bank loans are senior to bonds, firms that increase total financial debt—and thus assets and collateral—benefit from reduced credit risk, leading to lower bank loan rates. While increased bargaining power with relationship banks may contribute, particularly for firms heavily reliant on a main bank, controlling for issuance size we show that the debt seniority channel predominates.

We further examine the implications for firm performance. Issuer firms use the additional funding to expand total and fixed assets, particularly intangible ones, and increase turnover; they also raise leverage while reducing the share of bank loans in total financial debt.

Our findings carry important policy implications for the Capital Markets Union, especially for unlisted firms and SMEs. Deregulation reforms that remove barriers to market finance can broaden funding sources, increase financial resources for investment and growth, improve bank lending conditions, and alleviate credit constraints, highlighting the benefits of enabling market-based financing for smaller and unlisted companies.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0022109025102548.

Funding statement

Scopelliti acknowledges financial support from Internal Funds KU Leuven (STG/21/048). The views presented in this article are those of the authors and should not be attributed to Banca d’Italia, the European Central Bank or the Eurosystem.