Introduction

The crustose lichen genus Lecanora Ach. in Luyken, was created by Acharius as a segregate of the genus Lichen L. Shortly afterwards, Acharius (Reference Acharius1810) considerably expanded Lecanora, which included three subdivisions (Rinodina, Psoroma and Placodium), 132 species and 166 forms (as α, β, γ, etc.). Currently, the exact number of species reported to belong to Lecanora is unknown but is probably in the range of 600 (Lumbsch & Elix Reference Lumbsch, Elix, McCarthy and Mallett2004). Since the advent of molecular sequence data and its use in taxonomy, new species have continually been discovered and added to the genus (e.g. Lendemer & Tripp Reference Lendemer and Tripp2015; Malíček et al. Reference Malíček, Berger, Palice and Vondrák2017; Printzen et al. Reference Printzen, Blanchon, Fryday, de Lange, Houston and Rolfe2017; Yakovchenko et al. Reference Yakovchenko, Davydov, Ohmura and Printzen2019; Ivanovich et al. Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025).

When Acharius created the genus (Acharius, in Luyken Reference Luyken1809), he provided a general description, ‘Apoth. orbiculatum crassum sessile; lamina proligera colorata immarginata discum plano convexum formante margineque thallode tumido elevato sublibero cincta, intus cellulifera striataque. Thallus crustaceus uniformis vel effiguratus’ [‘Apothecium circular, thick, sessile; bright coloured lamina forming a flat-convex disc, surrounded by a ring of semi-free raised swollen thalline margin, cellular and striated inside. Thallus crustose, uniform or effigurate’]. The first genus to be segregated from Lecanora was Zeora Fr. in his ‘Systema Orbis Vegetabilis’. Later, Massalongo (Reference Massalongo1852, Reference Massalongo1853, Reference Massalongo1855) proposed the segregation of multiple genera from Lecanora, for example Acarospora A. Massal., Aspicilia A. Massal., Gyalolechia A. Massal., Haematomma A. Massal., Lecania A. Massal., Mischoblastia A. Massal., Ochrolechia A. Massal., Pachyospora A. Massal., Polyozosia A. Massal. and Thalloidima A. Massal. This led to a circumscription of the genus roughly equivalent to the family Lecanoraceae as currently understood. Regarding this large split, Massalongo (Reference Massalongo1852) wrote:

‘Coming now to the details of each genus, it should be noted that the genus Lecanora was reduced by me to the species with a crustose thallus and very small homogeneous spores, thus preserving for the most part the limits set by its author. The genus Rinodina, used by Acharius to indicate a section of his Lecanora, as well as the name Catillaria of the [genus] Lecidea, are here used in the opposite sense, so that they can be considered as new genera. The former, I hope, will be preserved, but the latter will perhaps be considered by some as a spurious genus, if it proves that the spores which I knew to be bilocular constantly insensibly change to monolocular, and that the excipulum is also subject to change. The genera Gyalolechia, Thalloidima, Acarospora, Ochrolechia, Haematomma, Pachyospora, Mischoblastia, which I propose for the first time, if not now, then later, will certainly be accepted, so natural and distinct are they!’Footnote 1.

With Massalongo’s (Reference Massalongo1852) proposal to place multiple groups with different morphology outside Lecanora, he understood the heterogeneity of the genus in its old circumscription and the need to divide it into ‘natural and distinct’ groups.

Further attempts to split Lecanora into more natural or practical groups included the separation of, for example, Myriolecis Clem., Rhizoplaca Zopf, and the creation of new subgeneric groups for morphologically similar species (Fries Reference Fries1871–Reference Fries74; Smith Reference Smith1921; Zahlbruckner Reference Zahlbruckner, Engler and Prantl1926). Most authors in the early and mid-20th century largely maintained the circumscription of Lecanora used by Zahlbruckner (Reference Zahlbruckner, Engler and Prantl1926) in his catalogue and some of its subgroups introduced by Smith (Reference Smith1921), such as the Lecanora subfusca-, L. symmicta- and L. varia-groups. One exception was Choisy (Reference Choisy1929, Reference Choisy1949) who, acknowledging the diversity of Lecanora, proposed several new genera combining species with a small number of shared characters. These included Glaucomaria M. Choisy, Lecanoropsis M. Choisy ex Ivanovich and Straminella M. Choisy, all treated in this paper, as well as Protoparmeliopsis M. Choisy. Further attempts to split Lecanora into more natural units were made by Poelt (Reference Poelt1958), Eigler & Poelt (Reference Eigler and Poelt1965) and Eigler (Reference Eigler1969), who among others introduced Squamarina Poelt, and recognized Aspicilia as well as Glaucomaria and Straminella as separate genera. Genera segregated more recently from Lecanora include Bryonora Poelt, Miriquidica Hertel & Rambold, and the resurrected Protoparmeliopsis (Hafellner & Türk Reference Hafellner and Türk2001).

DNA-based phylogenetic approaches provide a better taxonomic understanding of Lecanora s. lat., from species to subgeneric groups and their evolutionary relationships (e.g. Grube et al. Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004; Pérez-Ortega et al. Reference Pérez-Ortega, Spribille, Palice, Elix and Printzen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015; Kondratyuk et al. Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019; Yakovchenko et al. Reference Yakovchenko, Davydov, Ohmura and Printzen2019; Ivanovich et al. Reference Ivanovich, Dolnik, Otte, Palice, Sohrabi and Printzen2021, Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025; Medeiros et al. Reference Medeiros, Mazur, Miadlikowska, Flakus, Rodriguez-Flakus, Pardo-De la Hoz, Cieślak, Śliwa and Lutzoni2021). Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015) have provided the most comprehensive phylogenetic overview and classification of Lecanora s. lat. based on molecular data to date. In their study, Protoparmeliopsis and Rhizoplaca were confirmed to be monophyletic and their segregation from Lecanora s. str. is now generally accepted. The Lecanora dispersa-group was also confirmed to be monophyletic and the generic name Myriolecis was suggested for it. Although the Lecanora carpinea/rupicola-, L. polytropa- and L. varia-groups appeared phylogenetically distinct and received strong statistical support, they were not segregated (Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015). Other groups treated in this latter publication, such as the Lecanora saligna- and L. subcarnea-groups, were not strongly supported. The L. saligna-group was finally raised to genus level by Ivanovich et al. (Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025), who resurrected and validated the invalidly published name Lecanoropsis M. Choisy (Reference Choisy1949) for this group of species.

As a consequence of some other studies, further genera have recently been segregated from Lecanora, such as Palicella Rodr. Flakus & Printzen (Rodriguez Flakus & Printzen Reference Rodriguez Flakus and Printzen2014) and Pulvinora Davydov et al. (Davydov et al. Reference Davydov, Yakovchenko, Hollinger, Bungartz, Parrinello and Printzen2021). These genera were segregated on the basis of their supported monophyly (in addition to other evidence), but appeared nested within Lecanora s. lat. On the other hand, several morphologically circumscribed groups have been retained in Lecanora and not segregated into new genera because researchers hesitated to separate them based on equivocal or sparse morphological and/or chemical data (Lumbsch et al. (Reference Lumbsch, Plümper, Guderley and Feige1997), with the Lecanora carpinea-group; Grube et al. (Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004), with the L. rupicola-group; Printzen (Reference Printzen2001), with the L. saligna-group; Śliwa & Wetmore (Reference Śliwa and Wetmore2000), with the L. varia-group). This currently leaves the genus Lecanora still polyphyletic and morphologically heterogeneous.

Our study seeks to further clarify the taxonomic structure and generic circumscriptions within Lecanora s. lat. By including more mitochondrial regions in the phylogenetic analysis, a small number of additional lineages were recovered as monophyletic and statistically well supported (the Lecanora carpinea/rupicola-, L. symmicta- and L. varia-groups). Based on morphological and chemical characters, and phylogenetic support, we propose the segregation of these groups into the genera Glaucomaria, Zeora and Straminella, respectively. We include descriptions for the newly established genera, comment on their nomenclature and propose new taxonomic combinations. Finally, we include a list of taxa that we suspect may belong to the newly segregated genera, but for which no DNA sequences are available for confirmation.

Materials and Methods

Taxa selection

Specimens of Lecanora s. lat. were collected by the authors or obtained on loan from the following herbaria: ASU, BRY–C, FR, GLM, H, HBG, ICH, MIN, NY, PRA, S, UCR, UPS, and the private collections of Rainer Cezanne and Marion Eichler (Darmstadt, Germany), Bruce McCune (Corvallis, USA), Toby Spribille (Edmonton, Canada), and Christian Dolnik (Kiel, Germany).

Morphological and chemical analyses on selected specimens were performed as described in Ivanovich et al. (Reference Ivanovich, Dolnik, Otte, Palice, Sohrabi and Printzen2021). Photographs of specimens shown in Figs 3–7 were obtained using a Zeiss Axio Zoom V16 stereomicroscope. Chemical analyses (spot tests KOH 10% (K), Sodium hypochlorite (C), Paraphenylenediamine (Pd) (Orange et al. Reference Orange, James and White2001) and amphithecial granule solubility (KOH/HNO3) were performed on hand-cut sections of apothecia of selected specimens.

Multiple GenBank (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Karsch-Mizrachi, Lipman, Ostell and Sayers2016) sequences were added to the dataset based on the similarity of the selected species to Glaucomaria, Straminella and Zeora. Additional sequences from GenBank were included to represent in a comprehensive way the different genera segregated from Lecanora s. lat. and morphological groups distinguished within the genus. Preferably (but not exclusively) species were chosen for which ITS, mtSSU and nuLSU amplified from the same voucher were available. Pseudephebe minuscula (Nyl. ex Arnold) Brodo & D. Hawksw., Usnea antarctica Du Rietz and Usnea aurantiacoatra (Jacq.) Bory were included as outgroup. The selected outgroup taxa belong to the family Parmeliaceae, which is relatively closely related to Lecanoraceae (both belonging to Lecanorales; Miadlikowska et al. Reference Miadlikowska, Kauff, Högnabba, Oliver, Molnár, Fraker, Gaya, Hafellner, Hofstetter and Gueidan2014), and was the chosen outgroup family in Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015).

DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing

DNA was extracted from apothecia using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) or the GF-1 Plant DNA Extraction Kit (GeneOn), following the manufacturers’ protocols. Remnants of the substratum were cleaned from apothecia under a dissecting microscope prior to DNA extraction. PCR was performed on seven loci: ITS, nuLSU, mtSSU, atp6, cob, cox3 and nad1. A summary of primers and cycler programs used to amplify the different loci can be found in Table 1. Amplification of the selected regions was performed using PCR Ready-To-Go beads (GE Healthcare) in 25 μl reactions containing 5 μl DNA, 18 μl of double-distilled H2O and 1 μl of each primer. PCR products were checked on 1% agarose gels using electrophoresis. Successful PCR amplicons were Sanger-sequenced by Macrogen Europe (Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Forward and reverse sequences were assembled in Geneious Prime 2019.2.1 (https://www.geneious.com) and manually edited. DNA sequences were submitted to GenBank (Table 2).

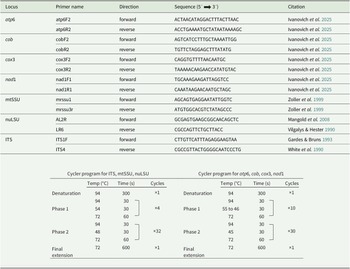

Table 1. Summary of primers and PCR programs used in the phylogenetic analyses.

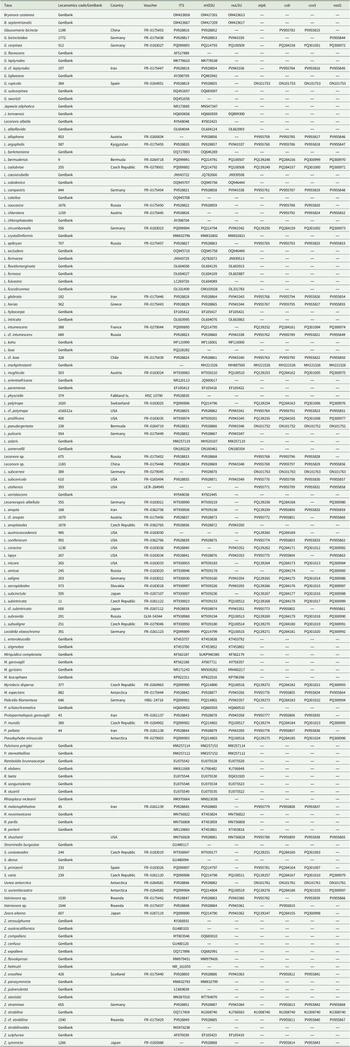

Table 2. Specimen voucher information and GenBank Accession numbers for the Lecanoraceae sequences used in the phylogenetic analyses. Lecanomics ID refers to the online database https://lecanomics.org.

Phylogenetic reconstruction

Alignments

Locus-specific alignments of consensus sequences were created through GUIDANCE2 (Landan & Graur Reference Landan and Graur2008; Penn et al. Reference Penn, Privman, Ashkenazy, Landan, Graur and Pupko2010; Sela et al. Reference Sela, Ashkenazy, Katoh and Pupko2015). For ITS, nuLSU and mtSSU, aligned positions with a score below 0.93 were removed. For the coding regions atp6, cob, cox3 and nad1, columns with low scores were not removed from the alignments. Instead, sequences with indels were compared to their original chromatograms, and singleton columns were subsequently removed after checking for codon frame shifts and translational coherency (no stop codons within the sequence) in the sequences and the alignments. Additionally, both ends of all the datasets were trimmed. Single-locus trees, concatenated nuclear loci (ITS and nuLSU) trees, and concatenated mitochondrial loci trees were then inferred from alignments using the IQ-TREE web server (Nguyen et al. Reference Nguyen, Schmidt, von Haeseler and Minh2015; Trifinopoulos et al. Reference Trifinopoulos, Nguyen, von Haeseler and Minh2016). The resulting topologies were visually compared to each other to check for statistically supported incongruencies (Som Reference Som2015).

Phylogenetic analysis

All single-locus datasets were merged into a concatenated alignment and a partitioning scheme was suggested, considering each codon position of the coding regions of the mitochondrial loci, the regions ITS1, 5.8S and ITS2 for the ITS region, and mtSSU and nuLSU as a single partition. A maximum likelihood (ML) tree and the optimal partition scheme were inferred with IQ-TREE using the default settings of an Ultrafast Bootstrap (Minh et al. Reference Minh, Nguyen and von Haeseler2013; Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Chernomor, von Haeseler, Minh and Vinh2017), 3000 bootstrap repetitions, and automatic substitution model selection with ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. Reference Kalyaanamoorthy, Minh, Wong, von Haeseler and Jermiin2017). For the Bayesian Inference analysis (BI), the same partition scheme was applied, and substitution models obtained in ModelFinder were translated into models supported by MrBayes (Table 3). Pseudephebe minuscula was selected as outgroup. Substitution model parameters were unlinked between data partitions. The branch length prior was set after calculating the average branch length of the ML tree, following the method outlined by Ekman & Blaalid (Reference Ekman and Blaalid2011). The BI was executed through MrBayes v. 3.2 (Ronquist et al. Reference Ronquist, Teslenko, van der Mark, Ayres, Darling, Höhna, Larget, Liu, Suchard and Huelsenbeck2012) as implemented on the CIPRES platform (Miller et al. Reference Miller, Pfeiffer and Schwartz2010), where three independent runs starting from random trees and six Markov chains incrementally heated by a factor of 0.15 were set to run for 40 000 000 generations. Trees were sampled every 200 generations and the first 50% of the sampled trees was discarded as burn-in. The analysis was set to stop when the standard deviation between split frequencies dropped below 0.01, considering only those bipartitions with a frequency of at least 30% in the tree sample. The resulting ML and BI trees were visualized and graphically improved using iTOL (Interactive Tree of Life webpage; Letunic & Bork Reference Letunic and Bork2021), where the best-fit ML tree was chosen for display (Figs 1 & 2), and posterior probabilities obtained from the BI were mapped onto the tree nodes (Fig. 2). Clades with ≥ 95% ML bootstrap (% UFBoot; as BS) and ≥ 0.95 posterior probability (PP) are considered well supported.

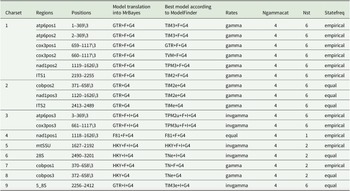

Table 3. Substitution models and parameters chosen for each partition set of the concatenated data matrix for ML and BI approaches.

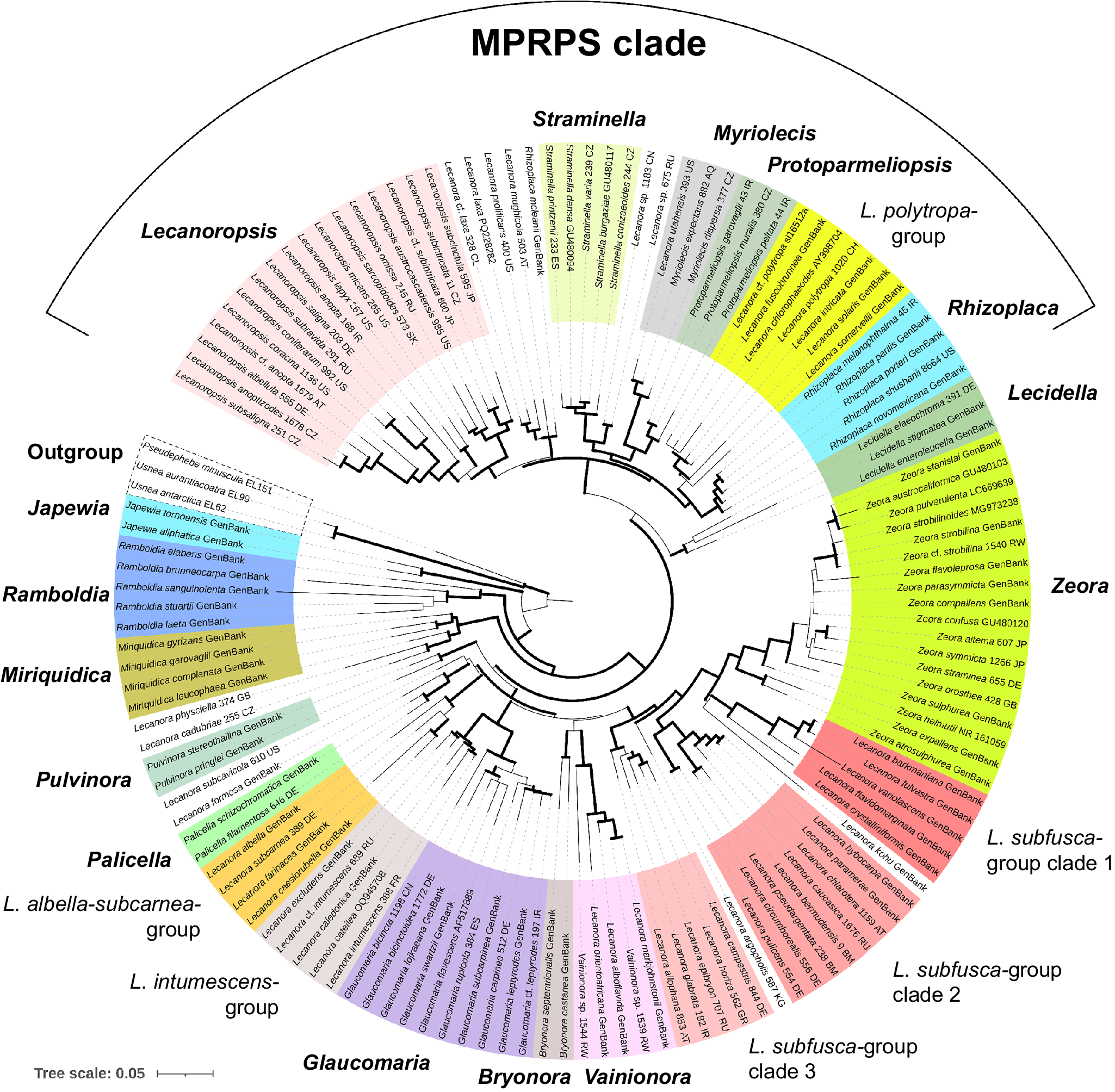

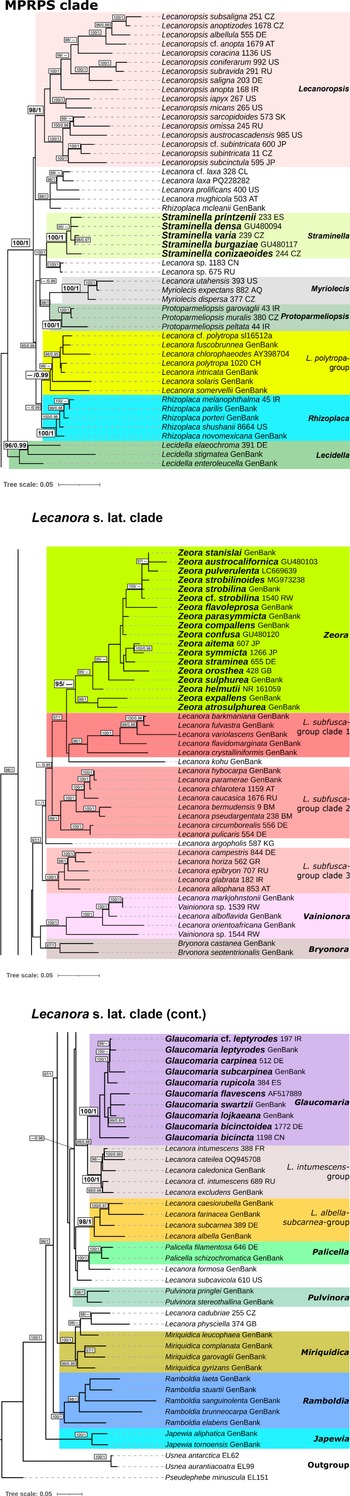

Figure 1. Maximum likelihood overview topology of Lecanora s. lat. based on a 7-loci concatenated dataset. Supported nodes (bootstrap support values ≥ 95%; Bayesian posterior probability ≥ 0.95) are shown in bold.

Figure 2. Maximum likelihood detailed topology of Lecanora s. lat. based on a 7-loci concatenated dataset. Bootstrap support values (BS) ≥ 95% and Bayesian posterior probability (PP) ≥ 0.95 are depicted on the nodes as follows: BS/PP. Lower bootstrap values on nodes with high posterior probability and vice versa are not shown. Newly resurrected genera are shown in bold: Glaucomaria (for the Lecanora carpinea/rupicola-group), Straminella (for the L. varia-group), and Zeora (for the L. symmicta-group).

Results

In total, 408 single-locus DNA sequences were generated for 70 specimens: 65 for ITS, 65 for mtSSU, 45 for nuLSU, 55 for atp6, 65 for cob, 59 for cox3, and 54 for nad1. Additionally, 164 sequences obtained from GenBank were added to the dataset. A total of 136 specimens and 572 sequences were included in this analysis. All sequences generated in this work were deposited in GenBank (Table 2). The concatenated alignment matrix spanned 3201 aligned nucleotide positions, with 1138 parsimony-informative positions, 402 sites with a single substitution, and 1661 constant sites. Substitution models applied to each partition are listed in Table 3.

The phylogeny shows that multiple morphologically and chemically circumscribed groups and genera were recovered as monophyletic with statistical support (Figs 1 & 2). However, internal nodes that would help to elucidate relationships between these genera and groups were usually unsupported.

The phylogeny presented in Figs. 1 and 2 shows that almost all taxa included in the analysis are assigned to genus-level clades with high support. This encompasses the genera Japewia Tønsberg (BS = 100%/PP = 1), Ramboldia Kantvilas & Elix (100/1), Miriquidica (100/1), Pulvinora (98/1), Palicella (100/1), Glaucomaria (100/1), Bryonora (97/1), Vainionora Kalb (100/1), Zeora (95/0.93), Lecidella Körb. (96/0.99), Rhizoplaca (100/1), Protoparmeliopsis (100/1), Myriolecis (100/1), Straminella (100/1) and Lecanoropsis (98/1), as well as the Lecanora albella/subcarnea-group (98/1), and the L. intumescens-group (100/1). Species from the L. subfusca-group are paraphyletic and distributed across three clades, here called L. subfusca-group clade 1 (96/1), clade 2 (99/1) and clade 3 (100/1). In addition, there are two yet unnamed species groups: a clade (99/1) containing the saxicolous Rhizoplaca mcleanii (C. W. Dodge) Castello along with four species similar to Lecanoropsis (relationship unsupported), and one containing Lecanora cadubriae (A. Massal.) Hedl. and L. physciella (Darb.) Hertel (98/0.93) in a highly supported (100/1) relationship with Miriquidica. A small number of orphaned species appear among these clades: Lecanora formosa (Bagl. & Carestia) Knoph & Leuckert and L. subcavicola B. D. Ryan appear paraphyletic at the base of Palicella; Lecanora argopholis (Ach.) Ach. is basal to the L. subfusca-group clade 2, clade 1 and Zeora; and Lecanora kohu Printzen et al. is sister to the L. subfusca-group clade 1.

Japewia, Ramboldia and the Miriquidica/L. cadubriae/L. physciella clade appear in this order at the base of Lecanoraceae. The remainder of the genera and groups fall into two major clades. One of these comprises the well-supported (100/1) MPRPS clade sensu Medeiros et al. (Reference Medeiros, Mazur, Miadlikowska, Flakus, Rodriguez-Flakus, Pardo-De la Hoz, Cieślak, Śliwa and Lutzoni2021) (Fig. 1) and Lecidella, the other an unsupported clade comprising most of the other species included in this analysis plus a small number of genera outside Lecanora s. lat.

Discussion

We used four recently published mitochondrial loci (Ivanovich et al. Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025) that proved to be useful for providing critical insight into phylogenetic relationships within Lecanoraceae. The success rates of DNA amplification and the high levels of variability of the regions atp6, cob, cox3, and nad1, indicate their suitability for the delimitation of genera in difficult systematic groups such as Lecanoraceae. The combination of these new markers with those more conserved such as nuclear LSU and mitochondrial SSU provided enough phylogenetic signal to support the monophyletic nature of some of the morphologically and chemically circumscribed groups within Lecanora s. lat.

The effectiveness of the new markers in also inferring relationships at subgeneric level is illustrated by the fact that within Lecanoropsis, where most taxa are represented by a complete 7-loci dataset, internal nodes are mostly well resolved, while within Zeora, where for the majority of the taxa only ITS, mtSSU and/or nuLSU were available, internal nodes are unsupported or supported in only one of the analyses. Comparison with previously published phylogenetic analyses also points to the effectiveness of these mitochondrial loci for phylogenetic resolution of previously unsolved lineages. For example, in the analysis of Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015), Lecanoropsis (the Lecanora saligna-group) appears unsupported in their 2-loci analysis. In Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019), the multiple clades formed by the genera Glaucomaria, Miriquidica, Ramboldia and Straminella also appear unsupported.

The 7-loci dataset resulted in a phylogenetic reconstruction (Figs 1 & 2) in which the monophyly of several previously distinguished morphological groups within Lecanora, including the Lecanora carpinea/rupicola- (= Glaucomaria), the L. symmicta- (= Zeora) and the L. varia-groups (= Straminella), was confirmed. This result aligns with other phylogenies published previously (Pérez-Ortega et al. Reference Pérez-Ortega, Spribille, Palice, Elix and Printzen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015; Ivanovich et al. Reference Ivanovich, Dolnik, Otte, Palice, Sohrabi and Printzen2021, Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Clancy, Jensen, McMullin, Wang and Leavitt2022; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Arup and Schiefelbein2023), indicating that there is sufficient evidence to support the generic segregation of these groups.

Other groups that appear to be monophyletic and received good support are the Lecanora albella/subcarnea-, the L. intumescens-, and the L. polytropa-groups. For the time being, we have chosen not to segregate these groups due to their unclear morphological circumscriptions which make it difficult to assess which Lecanora species could belong to them.

Interestingly, specimens belonging to the Lecanora subfusca-group formed three separate supported clades. Unexpectedly, L. argopholis, a species so far included in the L. subfusca-group, appeared outside of all three L. subfusca clades in an unresolved position. The L. subfusca-group clades are not discussed further in this paper since an in-depth analysis of this group is in progress (L. Li et al., unpublished data).

Taxonomy

The genus Glaucomaria M. Choisy

Glaucomaria was one of several new genera created by Choisy (Reference Choisy1929) to subdivide the large genera Lecanora and Lecidea Ach., since he understood that many species that probably belonged in Lecanora were wrongly placed in the genus Lecidea. Choisy (Reference Choisy1929) decided to elevate some of the more characteristic groups within Lecanora to generic level. Regarding L. glaucoma (= L. rupicola (L.) Zahlbr.), L. angulosa (= L. carpinea (L.) Vain.) and L. albella (= L. pallida Rabenh.), he wrote:

‘… distinct by a commonly colourless or very pale epithecium, characteristic of apothecia covered with a thick white pruina (rarely attenuated, the disc being then more or less dark and the epithecium olive or more rarely yellow). This group can form a particular genus that I will name Glaucomaria nov. gen. Choisy.’Footnote 2

Eigler (Reference Eigler1969) later accepted the generic segregation of Glaucomaria by Choisy and recognized within it the G. carpinea- and G. pallida-groups. Later, Santesson (Reference Santesson1993) found that Lecanora pallida (Schreb.) Rabenh. was an illegitimate younger homonym of L. pallida Chevall., and introduced the name Lecanora albella (Pers.) Ach., based on Lichen albellus Pers. (= Lecanora albella (Pers.) Ach.) as the oldest available name for the species. Brodo et al. (Reference Brodo, Haldeman and Malíček2019) accordingly changed the name of the Lecanora pallida-group to the L. albella-group. Following Brodo et al. (Reference Brodo, Haldeman and Malíček2019), the Lecanora albella-group is characterized by pruinose apothecial discs, a Pd+ red or yellow reaction, a lack of large oxalate crystals in the amphithecium, and a poorly developed or absent amphithecial cortex. Our phylogenetic results provide no evidence of a close relationship between the Lecanora albella- and the L. carpinea/rupicola-groups. Thus, for now, we do not include the L. albella-group in Glaucomaria.

Hafellner (Reference Hafellner1984) lectotypified Glaucomaria on Lecanora rupicola (L.) Zahlbr. without providing any comment. Leuckert & Poelt (Reference Leuckert and Poelt1989) analyzed the L. rupicola-group in depth, focusing mainly on the diversity of secondary metabolites, finding that all taxa accepted by them produced the chromone sordidone (or its derivative eugenitol) in the hymenium and/or thallus. Similarly, Lumbsch et al. (Reference Lumbsch, Plümper, Guderley and Feige1997) found the presence of chromones in several corticolous, pruinose taxa of Lecanora. Some of the species studied by Lumbsch et al. (Reference Lumbsch, Plümper, Guderley and Feige1997) had already been suggested as belonging to the L. carpinea-group by Eigler (Reference Eigler1969). Grube et al. (Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004) pointed out that all species within this group have apothecia with a conspicuous whitish to yellowish pruina made of sordidone. However, they did not accept the generic status of Glaucomaria without clarification of the phylogenetic relationships of the species within Lecanora s. lat. Later, phylogenetic analyses unveiled the monophyly of the sordidone-producing taxa of Lecanora (Blaha & Grube Reference Blaha and Grube2007; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015; Malíček et al. Reference Malíček, Berger, Palice and Vondrák2017; Kondratyuk et al. Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019). Cannon et al. (Reference Cannon, Malíček, Ivanovich, Printzen, Aptroot, Coppins, Sanderson, Simkin and Yahr2022) recognized the genus Glaucomaria for the Lecanora rupicola-group and included the species occurring in the British Isles. Our phylogeny also supports the segregation of the Lecanora carpinea/rupicola-group characterized by the production of the chromones sordidone and eugenitol under Glaucomaria.

Glaucomaria sulphurea (Hoffm.) S. Y. Kondr. et al. is a combination based on one ITS sequence (AY541260; Grube et al. Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004) of Lecanora rupicola subsp. sulphurata (Ach. ex Nyl.) Leuckert & Poelt that was placed in the Glaucomaria clade in the analysis of Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019). However, when creating the new combination, Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019) incorrectly indicated Verrucaria sulphurea Hoffm. as the basionym. The correct basionym of Lecanora rupicola subsp. sulphurata (Ach. ex Nyl.) Leuckert & Poelt (the name of the specimen used in their analysis) is Lecanora glaucoma var. sulphurata Ach., as pointed out by Leuckert & Poelt (Reference Leuckert and Poelt1989). Lecanora sulphurea (Hoffm.) Ach., the currently accepted name of Verrucaria sulphurea Hoffm., is a member of the Lecanora symmicta-group (treated here as Zeora sulphurea (Hoffm.) Flot., see below). Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019) did include one specimen of L. sulphurea in their analysis. This specimen appears in the Lecanora symmicta-group, which is concordant with our analysis. The failure to include a ‘full and direct reference’ to the basionym makes the combination Glaucomaria sulphurea (Hoffm.) S. Y. Kondr. et al. invalid according to Art. 41.5 (Turland et al. Reference Turland, Wiersema, Barrie, Gandhi, Gravendyck, Greuter, Hawksworth, Herendeen, Klopper and Knapp2025).

The correct new combination for Lecanora rupicola subsp. sulphurata should have been either Glaucomaria rupicola subsp. sulphurata or G. sulphurata if treated at species rank. We refrain from suggesting any of these combinations because current evidence from molecular studies indicates that Glaucomaria rupicola subsp. sulphurata is conspecific with Glaucomaria rupicola subsp. rupicola (Grube et al. Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004).

Lumbsch et al. (Reference Lumbsch, Plümper, Guderley and Feige1997) studied Lecanora subpallens Zahlbr., a later synonym of Lecanora protervula Stirton, and reported the presence of sordidone in this species. Brodo et al. (Reference Brodo, Haldeman and Malíček2019), who showed the name Lecanora protervula to be the oldest name available for L. subpallens, provided a detailed description of the species, fitting into the concept of Glaucomaria. Unfortunately, no molecular data are available for L. protervula to confirm this assumption.

Glaucomaria M. Choisy

Bull. Soc. bot. Fr. 76, 522 (1929); type: Lecanora rupicola (L.) Zahlbr., designated by Hafellner (Reference Hafellner1984).

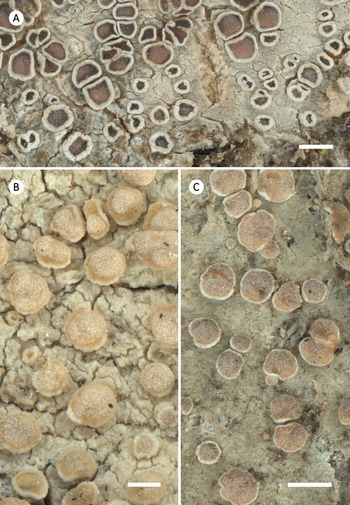

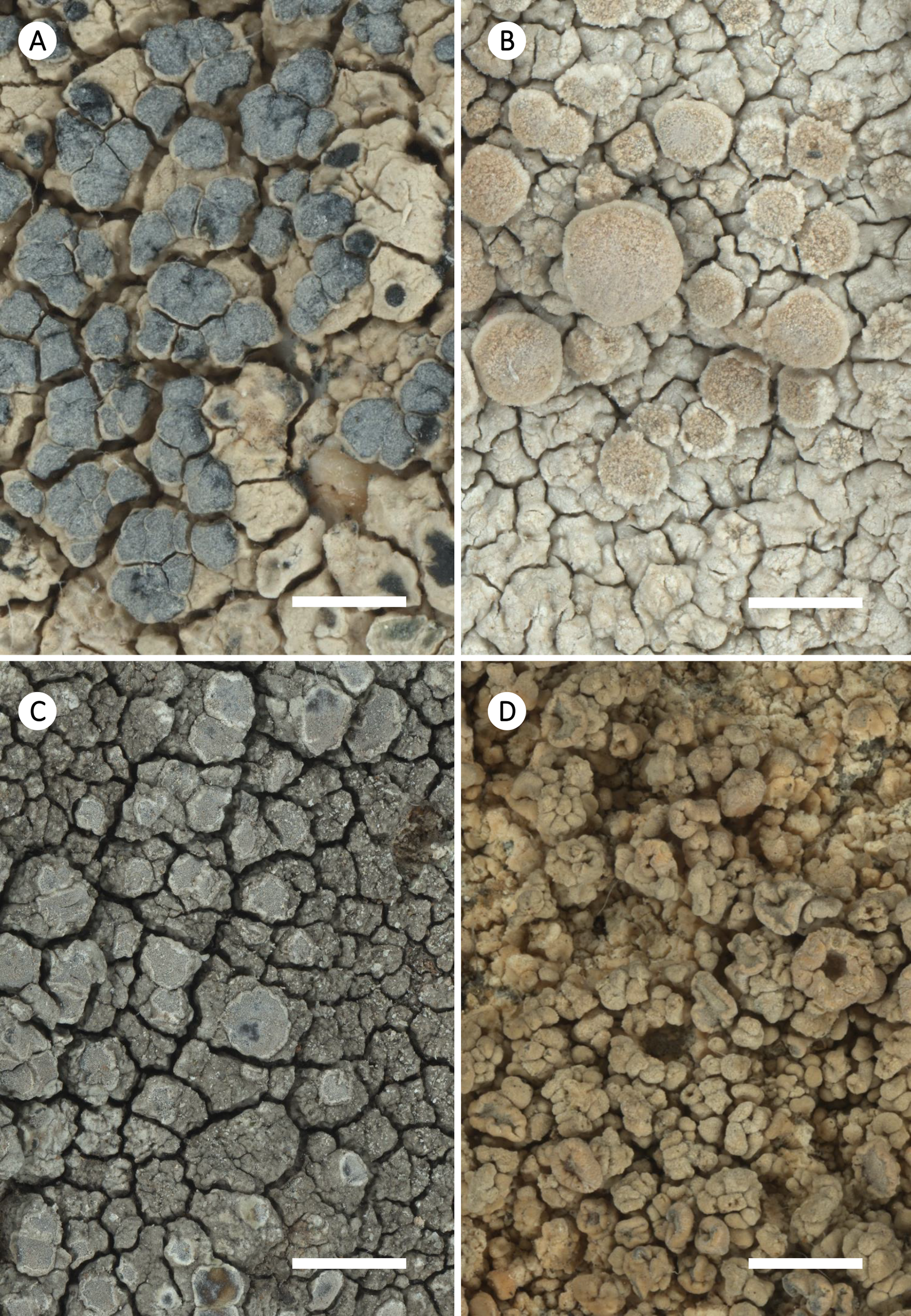

Figure 3. Habitus of selected corticolous species of Glaucomaria. A, G. carpinea; Germany, Thüringen, R. Cezanne & M. Eichler 11561 (FR-0183027; L512). B, G. leptyrodes; Sweden, Värmland, U. de Bruyn 4862 (FR-0261657). C, G. subcarpinea; Russia, Altaysky Kray, C. Printzen 8574 (FR-0045453). Scales: A & C = 1 mm; B = 0.5 mm.

Figure 4. Habitus of selected saxicolous species of Glaucomaria. A, G. bicincta; China, Changdu, L. S. Wang 18-60827 (FR–0175453). B, G. bicinctoidea; Germany, Hessen, R. Cezanne & M. Eichler 12338 (FR–0175438). C, G. rupicola; Czech Republic, Prague, Z. Palice 21087 (FR-0264960). D, G. swartzii; Slovakia, Prešov, H. Lojka 25 (FR-0080158). Scales: A & B = 1 mm; C & D = 2 mm.

Thallus crustose, episubstratal, usually whitish to pale grey, yellowish with a tint of green, grey or orange, greenish grey to greyish brown, continuous, smooth to rimose or verrucose-areolate, most species esorediate, sorediate in G. flavescens, G. lojkaeana, and in the varieties G. bicincta var. sorediata and G. rupicola ssp. rupicola var. efflorens (Leuckert & Poelt Reference Leuckert and Poelt1989); isidia absent, generally without true cortex or/and hypothallus. Prothallus white, whitish grey or beige, bluish brown to blackish or absent.

Apothecia lecanorine, adpressed to sessile, single to crowded; discs flat to convex, yellowish to pinkish and carneous to brown and dark brown, typically covered by conspicuous whitish, yellowish or bluish grey pruina, rarely nearly epruinose. Glaucomaria flavescens and G. lojkaeana are typically sterile taxa and can be found very rarely with apothecia. Margin concolorous with thallus, mainly prominent and persistent, entire to flexuose. Margin lecanorine, variable, commonly inspersed with small granules dissolving in KOH, POL+, sometimes underdeveloped or absent in specimens where apothecia are immersed or weakly erumpent from the substratum. Glaucomaria carpinea shows a thick, strongly gelatinized cortex, whereas the G. rupicola/bicincta complex is characterized by an amphithecial ‘phenocortex’ sensu Poelt (Reference Poelt1989), of dead hyphal and algal cells (Blaha & Grube Reference Blaha and Grube2007). Glaucomaria swartzii- subgroup develops an ‘eucortex’ which corresponds to a typical amphithecial cortex in lecanorine margins. Epihymenium hyaline or yellowish brown, greyish brown to brown and dark brown, also greenish to dark olivaceous brown; granular. Hymenium hyaline. Subhymenial layers hyaline to pale yellow. Parathecium hyaline (except in G. bicincta which has an apically pigmented parathecium that can be seen as an inner black ring around the apothecial disc). Asci Lecanora-type, clavate, with 8 spores. Ascospores ellipsoid, simple.

Conidia as leptoconidia sensu van den Boom & Brand (Reference van den Boom and Brand2008), filamentous, curved.

Chemistry

K+ pale yellow to yellow (K− in G. bicincta; K± yellow in G. bicinctoidea); C+ yellow, orange to orange-red; Pd± pale yellow to yellow (orange-red in the thallus of G. lojkaeana). All Glaucomaria species produce sordidone and atranorin as major metabolites, with chloroatranorin and/or eugenitol as minors. Most saxicolous species also produce roccellic acid, and some taxa may produce psoromic acid and xanthones (arthothelin, thiophanic acid, and their derivatives). A rare compound 3a-hydroxy-4-O-demethylbarbatate, was reported from G. bicinctoidea (Blaha & Grube Reference Blaha and Grube2007).

Substratum

Corticolous (L. carpinea-subgroup; Grube et al. Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004); saxicolous (G. rupicola- and G. swartzii- subgroups; Grube et al. Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004).

Distribution

Subcosmopolitan; species from this genus are present on almost all continents, except for Antarctica.

List of species

Glaucomaria bicincta (Ramond) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 153 (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019).—Lecanora bicincta Ramond, Mém. Acad. Sci. Inst. France 6, 132 (1823 [1827]).

(Fig. 4A)

Glaucomaria bicinctoidea (Blaha & Grube) Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov

MycoBank No.: MB 858687

Lecanora bicinctoidea Blaha & Grube, Mycologia 99(1), 53 (2007).

(Fig. 4B)

Glaucomaria carpinea (L.) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al, Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 153 (2019).—Lichen carpineus L., Sp. pl. 2, 1141 (1753).—Lecanora carpinea (L.) Vainio, Meddn Soc. Fauna Flora Fenn. 14, 23 (1888).

(Fig. 3A)

Glaucomaria flavescens (Cl. Roux & Tønsberg) Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858688

Lepraria flavescens Cl. Roux & Tønsberg, in Tønsberg, Graphis Scripta 13(2), 48 (2002).—Lecanora rouxii S. Ekman & Tønsberg, in Grube et al., Mycol. Res. 108(5), 512 (2004).

Notes

When transferring G. flavescens from Lepraria to Lecanora, Ekman & Tønsberg (in Grube et al. Reference Grube, Baloch and Arup2004) proposed the new epithet ‘rouxii’ because the name Lecanora flavescens (Bagl.) Bagl. already existed. In the genus Glaucomaria, the older epithet has priority. The basionym Lepraria flavescens Cl. Roux & Tønsberg was previously published by Clauzade & Roux (Reference Clauzade and Roux1977), but it lacked proper reference to the type specimen (‘Holotypus in herbario Cl. Roux’), making it invalid according to Art. 40 (Turland et al. Reference Turland, Wiersema, Barrie, Gandhi, Gravendyck, Greuter, Hawksworth, Herendeen, Klopper and Knapp2025). A later attempt to validate this name in Clauzade & Roux (Reference Clauzade and Roux1980) failed by not correctly citing the exact page of the protologue, but rather a general reference to the publication itself (Arts 38.14 and 41.5). Later, Tønsberg (Reference Tønsberg2002), in his work on Lepraria from Norway, provided a direct reference to the original diagnosis and a full citation of the type, thereby validating the name. However, he mistakenly indicated ‘Lepraria flavescens Cl. Roux & Tønsberg’ as a replacement name (‘nom. nov.’). and not a new species ‘sp. nov.’). This can, however, be treated as a ‘correctable error’ according to Art. 6.14, and thus the publication of Lepraria flavescens Cl. Roux & Tønsberg by Tønsberg (Reference Tønsberg2002) counts as validly published.

Glaucomaria leptyrodes (Nyl.) Ivanovich-Hichins & Printzen comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 859412

Lecanora angulosa (Schreb.) Ach. var. leptyrodes Nyl., Lich. Env. Paris: 59 (1896: 59).—Lecanora leptyrodes (Nyl.) G. B. F. Nilsson, Ark. Bot. 24A(no. 3), 82 (1931).

(Fig. 3B)

Notes

This taxon was first mentioned by Nylander (Reference Nylander1874) as L. angulosa var. leptyrodes, but a valid description was first published later (Nylander Reference Nylander1896). This variety was then elevated to species rank by Nilsson (Reference Nilsson1931) as L. leptyrodes (Nyl.) G. B. F. Nilsson. Nilsson cited the correct basionym without providing a direct citation for it, which could have been either Nylander (Reference Nylander1874) or Nylander (Reference Nylander1896). Nevertheless, this combination fulfils Art. 41.1 and Art. 41.3 and is therefore valid. Lumbsch et al. (Reference Lumbsch, Plümper, Guderley and Feige1997) published a description and lectotypified the name L. leptyrodes. Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019), when transferring the species from Lecanora to Glaucomaria, cited the incorrect basionym, referring to ‘Lecanora leptyrodes G. B. F. Nilsson’ and not Lecanora angulosa (Schreb.) Ach. var. leptyrodes Nyl. Additionally, they cited the incorrect authorship for the name, citing Lecanora leptyrodes G. B. F. Nilsson and not Lecanora leptyrodes (Nyl.) G. B. F. Nilsson, thus rendering Glaucomaria leptyrodes (G. B. F. Nilsson) S. Y. Kondr. et al. an invalid combination.

Glaucomaria lojkaeana (Szatala) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 154 (2019).—Lecanora lojkaeana Szatala, Annls. hist.-nat. Mus. natn. hung. 46 (n.s. 5), 135 (1954).

Glaucomaria rupicola (L.) P. F. Cannon

In Cannon et al., Revisions of British and Irish Lichens 25, 75 (2022). —Lichen rupicola L., Mant. Pl. 1, 132 (1767).—Lecanora rupicola (L.) Zahlbr., Cat. Lich. Univers. 5, 525 (1928).

(Fig. 4C)

Notes

The combination Glaucomaria rupicola (L.) S.Y. Kondr. et al. in Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019) was invalidly published by the authors according to Art. 41.1, because no basionym was cited and no statement of ‘comb. nov.’ was included.

Glaucomaria subcarpinea (Szatala) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 154 (2019).—Lecanora subcarpinea Szatala, Annls. hist.-nat. Mus. natn. hung. 46(n.s. 5), 136 (1954).

(Fig. 3C)

Glaucomaria swartzii (Ach.) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 154 (2019).—Lichen swartzii Ach., K. Vetensk-Acad. Nya Handl. 15(3), 185 (1794).—Lecanora swartzii (Ach.) Ach., Lich. Univ., 363 (1810).

(Fig. 4D)

The genus Straminella M. Choisy

Straminella was introduced by Choisy (Reference Choisy1929), with Lecanora varia (Hoffm.) Ach. (as Lecanora varia ‘Ach.’) as the type species. The genus was characterised as having a yellow thallus, claviform asci, conglutinate and partially branching paraphyses, as well as filiform, curved conidia (Choisy Reference Choisy1929). Eigler (Reference Eigler1969) and Hafellner (Reference Hafellner1984) list Straminella as a genus in Lecanoraceae, while Motyka (Reference Motyka1995–Reference Motyka1996) assigned some species of the group to different sections (L. varia to sect. Chlaronae or L. conizaeoides Nyl. ex Cromb. to sect. Conizaeae) but chose to maintain Lecanora as the generic name.

Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019) accepted the name Straminella for what was elsewhere known as the Lecanora varia-group (e.g. Smith Reference Smith1918, Reference Smith1921; McCune Reference McCune2017) and based this decision on molecular data without providing any further descriptions. They incorporated six species into Straminella, including Straminella bullata (Follmann & A. Crespo) S.Y. Kondr. et al. and S. maheui (Hue) S.Y. Kondr. et al. as separate species. However, Gómez-Bolea & Barbero Castro (Reference Gómez-Bolea and Barbero Castro2009) showed that Rhizoplaca bullata (Follmann & A. Crespo) Leuckert & Poelt is conspecific with Polycauliona maheui Hue, which they recombined into Rhizoplaca maheui (Hue) Gómez-Bolea & M. Barbero. In the phylogeny provided by Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019), S. bullata is not included, and S. maheui is in a sister relationship with all other Straminella species. Due to its fruticose growth form and apothecial characters that set it clearly apart from the other species in Straminella, we suggest retaining the name Rhizoplaca maheui (Hue) Gómez-Bolea & M. Barbero and excluding it from Straminella until further studies have been conducted. We provide here a description of the genus and a provisional list of taxa belonging to it.

Straminella M. Choisy

Bull. Soc. Bot. Fr. 76, 522 (1929); type: Lecanora varia (Hoffm.) Ach. (1810), designated by Choisy (Reference Choisy1929).

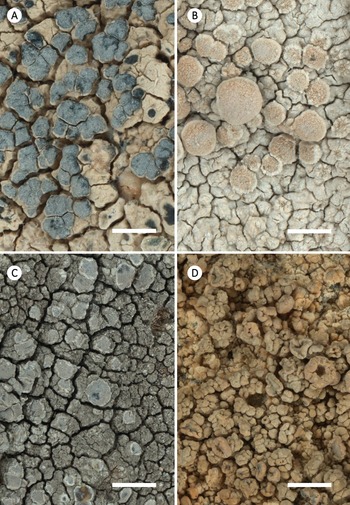

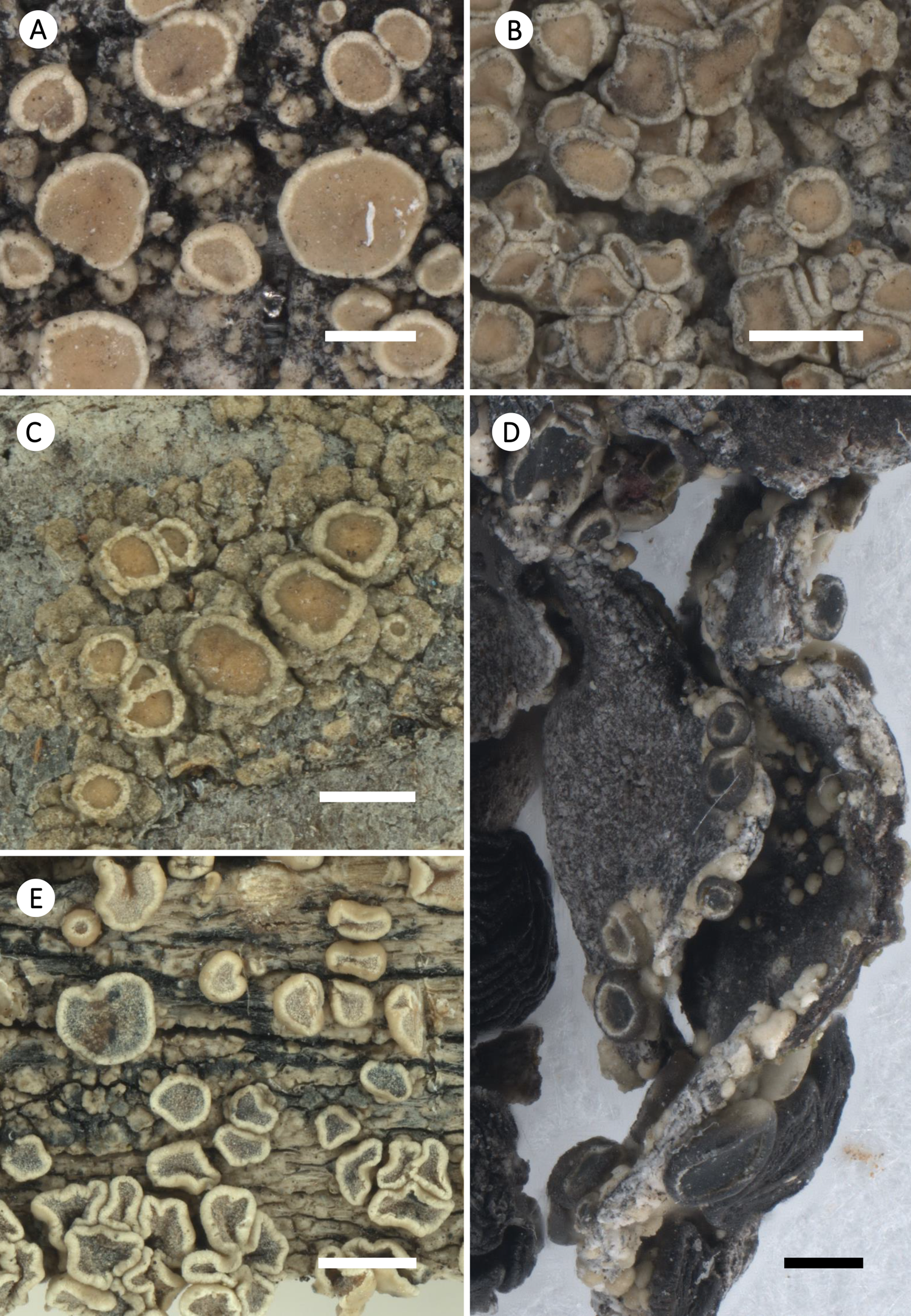

(Fig. 5)

Thallus mainly episubstratal, greenish yellow, greenish, greyish yellow to beige, typically esorediate (except S. conizaeoides which can produce soredia). Prothallus not apparent.

Figure 5. Habitus of selected species of Straminella. A, S. burgaziae; Spain, Zamora, S. Pérez-Ortega & A. Álvarez (FR-0212659). B, S. conizaeoides; Germany, Hessen, J. H. Reimer (FR-0055139). C, S. densa; USA, Arizona, S. Pérez-Ortega (FR-0212649). D, S. printzenii; Spain, Castilla y León, S. Pérez-Ortega & M. Arróniz-Crespo (FR-0183026; L233; isotype; growing on Umbilicaria sp.). E, S. varia; Austria, Tirol, S. Pérez-Ortega & C. Printzen (FR-0212999). Scales: A– D = 0.5 mm; E = 1 mm.

Apothecia lecanorine, single to crowded and very numerous, slightly immersed to adpressed to sessile, rounded to flexuose, moderately concave to flat to weakly convex; disc pale yellow to brownish or yellowish green to greenish or greyish brown (becoming blackish in both S. printzenii and S. varia), apothecial discs epruinose to pruinose. Margin typically prominent and persistent in old apothecia. Margin lecanorine, basally distinctly thickened, hyaline to brown (blackened in S. printzenii), with POL+, KOH-soluble granules. Epihymenium brown or greenish brown to greenish black, with POL+, KOH-soluble granules. Hymenium hyaline to pale yellow. Paraphyses simple to weakly branched, 1–2 μm wide, anastomosing below, not or slightly widened at the apex. Subhymenial layers distinct, sometimes very short in height in relation to the hymenium, subhymenium hyaline or pale yellow. Asci Lecanora-type (sensu Honegger Reference Honegger1978), 8-spored, cylindrical-clavate. Ascospores hyaline, non-septate, ellipsoid to broadly ellipsoid, length to width ratio 1.73–2.3.

Conidia filiform, curved.

Chemistry

C−, K± yellow, Pd+ yellow (orange to red in S. conizaeoides). Usnic acid is the main substance; additionally, psoromic acid and 2′-O-demethylpsoromic acid can be found in the majority of the Straminella taxa, with the exception of S. conizaeoides which produces fumarprotocetraric acid instead.

Substratum

Frequently on bark or wood. Straminella conizaeoides can be found on a wide range of low pH substrata. Straminella printzenii is lichenicolous, reported to inhabit Umbilicaria Hoffm. and Psorinia Gotth. Schneid. (Flakus & Śliwa Reference Flakus and Śliwa2012).

Distribution

Currently known from North America, North Africa, Europe, East Asia and Australia.

Notes

Eigler (Reference Eigler1969) kept all species with a yellow-green thallus under Straminella M. Choisy em. Eigler, including taxa belonging to Zeora (the Lecanora symmicta-group, see below under the Zeora section) and Lecanoropsis. Following the circumscription by Eigler (Reference Eigler1969), the general characters of the group would be the presence of usnic acid and the absence of large calcium oxalate crystals in the amphithecium (Brodo & Elix Reference Brodo and Elix1993). Our own results and the molecular studies of Lecanoraceae by other authors (Pérez-Ortega et al. Reference Pérez-Ortega, Spribille, Palice, Elix and Printzen2010; Zhao et al. Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015; Kondratyuk et al. Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019; Lee & Hur Reference Lee and Hur2021; Weber et al. Reference Weber, Arup and Schiefelbein2023; Ivanovich et al. Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025) clearly show that species with these traits are found in separate clades. Straminella (as the ‘Lecanora varia-group’) has received attention from several authors (Śliwa & Wetmore Reference Śliwa and Wetmore2000; Printzen Reference Printzen2001; Laundon Reference Laundon2003; Martínez & Aragón Reference Martínez and Aragón2004; Pérez-Ortega et al. Reference Pérez-Ortega, Spribille, Palice, Elix and Printzen2010; de la Rosa et al. Reference de la Rosa, Messuti and Lumbsch2010; Flakus & Śliwa Reference Flakus and Śliwa2012), and descriptions of particular species of the genus, as well as their heterotypic synonyms, can be found in the cited references.

List of species

Straminella burgaziae (I. Martínez & Aragón) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 158 (2019).—Lecanora burgaziae I. Martínez & Aragón, Bryologist 107(2), 223 (2004).

(Fig. 5A)

Straminella conizaeoides (Nyl. ex Cromb.) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 158 (2019).—Lecanora conizaeoides Nyl. ex Cromb., J. Bot., Lond. 23, 195 (1885).

(Fig. 5B)

Straminella densa (Śliwa & Wetmore) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 158 (2019).—Lecanora varia subsp. densa Śliwa & Wetmore, Bryologist 103(3), 486 (2000).—Lecanora densa (Śliwa & Wetmore) Printzen, Bryologist 104(3), 394 (2001).

(Fig. 5C)

Straminella printzenii (Pérez-Ort., M. Vivas & Hafellner) Pérez-Ort. & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858686

Lecanora printzenii Pérez-Ort. et al., in Lumbsch et al., Phytotaxa 18, 76 (2011).

(Fig. 5D)

Straminella varia (Hoffm.) S. Y. Kondr., Lőkös & Farkas

In Kondratyuk et al., Acta Bot. Hung. 61(1–2), 158 (2019).—Patellaria varia Hoffm., Descr. Adumb. Plant. Lich. 1(4), 102 (1790).—Lecanora varia (Hoffm.) Ach., Lich. Univ., 377 (1810).

(Fig. 5E)

Notes

There are some species, such as Lecanora subviridis de la Rosa & Messuti and L. vinetorum Poelt & Huneck, that have been suggested to belong to the Lecanora varia-group, but we hesitate to assign them to Straminella due to a lack of molecular data.

Lecanora laxa (Śliwa & Wetmore) Printzen was assigned to the Lecanora varia-group by Śliwa & Wetmore (Reference Śliwa and Wetmore2000), Laundon (Reference Laundon2003) and Pérez-Ortega et al. (Reference Pérez-Ortega, Spribille, Palice, Elix and Printzen2010). In contrast, Printzen (Reference Printzen2001) stated that L. laxa is morphologically and chemically more similar to Lecanoropsis coniferarum (Printzen) Ivanovich & Printzen and L. saligna (Schrad.) Ivanovich & Printzen than to Straminella densa and S. varia. Our phylogenetic analysis places Lecanora laxa in neither the Lecanoropsis nor the Straminella clade, but rather in a third, well-supported clade together with Lecanora mughicola Nyl. and L. prolificans Ivanovich et al.. Due to its placement outside of both clades, we refrain from recombining Lecanora laxa into either Lecanoropsis or Straminella.

The genus Zeora Fr.

Zeora was first introduced by E. Fries (Reference Fries1825), who characterized it as having waxy apothecia with a disappearing, pulverulent thalline margin. Furthermore, the author noted that many species are sterile with a leprose thallus, and listed several species. Flotow (Reference Flotow1850) used the name Zeora very broadly for crustose lichens with a lecanorine margin and made the combination Zeora orosthea (Ach.) Flot. Also focusing on the excipulum, Körber (Reference Körber1855) and Leunis (Reference Leunis1886) considered Zeora to be similar to Lecanora, but with species usually having a margin composed of a dark proper excipulum within the thalline margin. The term for this, a zeorine margin, is mainly used when the proper exciple can be recognized as a parathecial crown, as is the case, for example, in many species of Acarospora or in Glaucomaria bicincta, but not in any of the taxa understood here as Zeora. Choisy (Reference Choisy1929) used the name Zeora Fr. for Lecanora species with a more or less dark greenish epihymenium and a well-developed proper margin, and included Lecanora cenisia Ach. and L. sulphurea (Hoffm.) Ach. (as L. sulphurea Ach. in Choisy (Reference Choisy1929)) within it. Hafellner (Reference Hafellner1984) designated Lecanora orosthea (Ach.) Ach. as the type species of Zeora.

For the combination Glaucomaria sulphurea (Hoffm.) S. Y. Kondr. et al. (Kondratyuk et al. Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019), see above.

In the circumscription suggested by our phylogeny, Zeora comprises species with a typically yellowish-greenish, sometimes sorediate thallus, a disc margin often becoming excluded, and the amphithecial margin appearing ecorticated and lacking large crystals. Most species are corticolous or lignicolous, although saxicolous species do occur in the group (e.g. Z. atrosulphurea and Z. orosthea). They typically produce usnic acid and zeorin, but no atranorin (except for Z. sulphurea). Zeora differs from Straminella by the thallus appearance (granular, farinose and/or sorediate in Zeora vs esorediate and warted in Straminella), the disc margins (usually becoming excluded in Zeora, persistent in Straminella) and the amphithecial margin being corticated in Straminella. Additionally, species of Zeora produce zeorin but no psoromic acid, whereas those of Straminella typically produce psoromic acid (except S. conizaeoides) but not zeorin.

In our phylogenetic analysis, Zeora clustered closely with clade 1 of the Lecanora subfusca-group, represented here by Lecanora barkmaniana Aptroot & Herk (as ‘barkmaneana’), L. crystalliniformis (B. G. Lee & Hur) Li J. Li & Printzen, L. flavidomarginata B. de Lesd., L. fulvastra Kremp. and L. variolascens Nyl. Species in this clade share more morphological and chemical similarities with Lecanora subfusca s. str. and the taxa included in Lecanora subfusca clades 2 and 3 than with Zeora, such as a persistent apothecial margin, large KOH-insoluble crystals in the amphithecium, and the production of atranorin. Phylogenetically, however, the Lecanora subfusca clade 1 appears to be more closely related to Zeora than to the other L. subfusca clades present in our analysis.

Taxa assigned here to Zeora were previously assigned to the informal Lecanora symmicta-group (e.g. Smith Reference Smith1921; Printzen & May Reference Printzen and May2002) or sulphurea-group (Smith Reference Smith1921) but also the Lecanora varia-group (Śliwa & Wetmore Reference Śliwa and Wetmore2000). Based on margin anatomy, Printzen (Reference Printzen2001) assigned some species to his group 1 (Lecanora confusa and L. strobilina) and others to group 2 (L. symmicta). The heterogenous classification of species from the L. symmicta-group carried out by different authors shows the difficulty in discriminating species of Zeora from taxa belonging to other groups within Lecanora s. lat. that also produce usnic acid.

Zeora Fr.

Syst. orb. veg. 1, 244 (1825); type: Lecanora orosthea (Ach.) Ach. (1810), designated by Hafellner (Reference Hafellner1984).

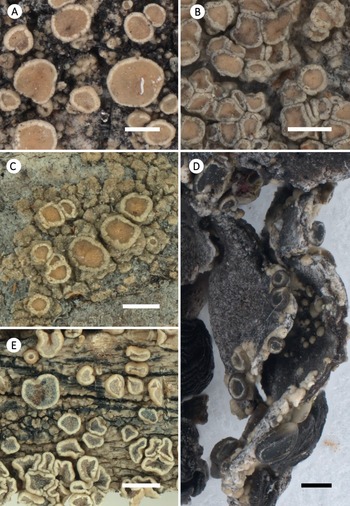

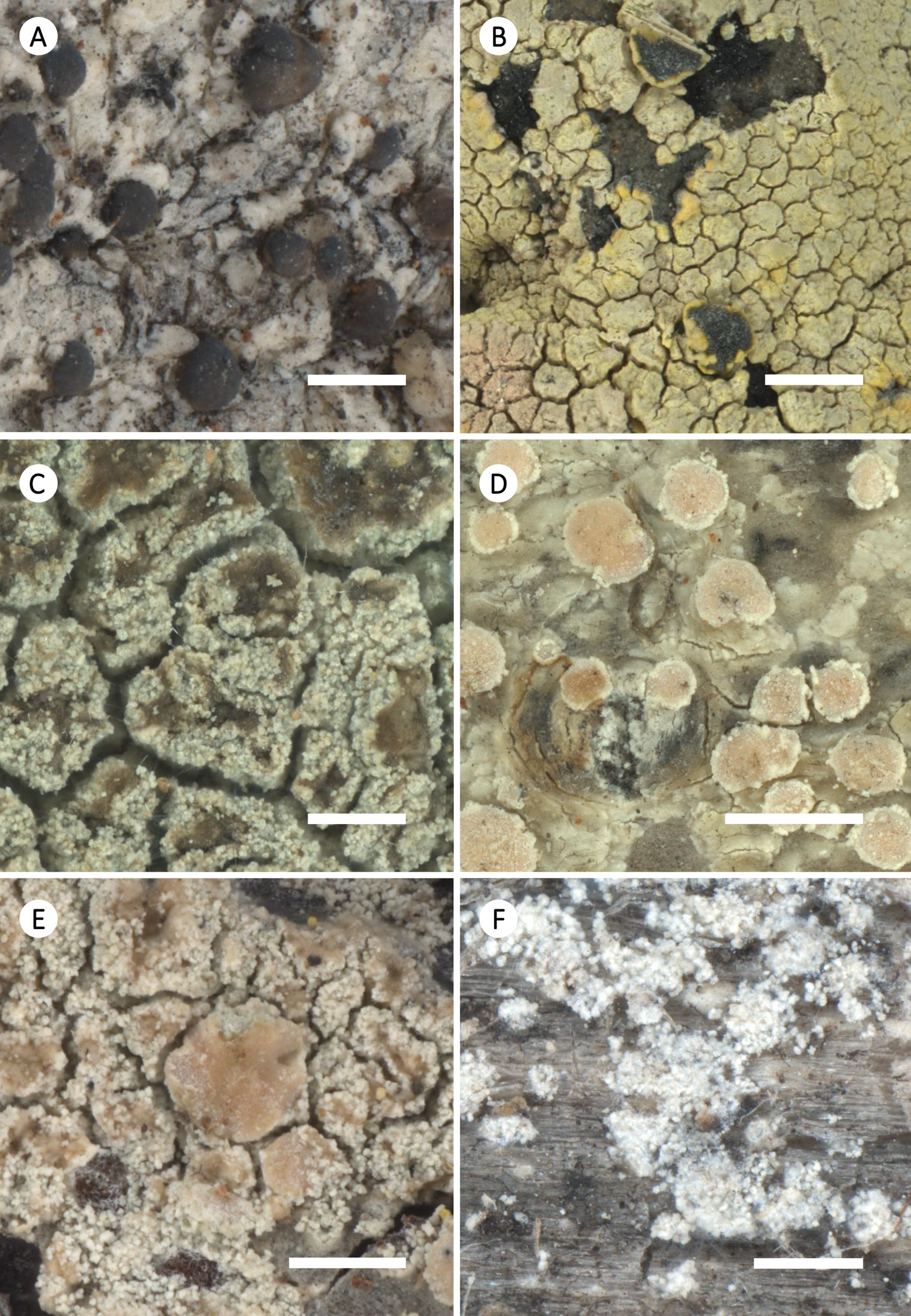

Figure 6. Habitus of selected species of Zeora. A, Z. aitema; Norway, Hordaland, C. Printzen, T. Tønsberg & S. Ekman s. n. (FR- 0211866). B, Z. atrosulphurea; Portugal, Madeira, H. J. Reimer (FR-0057516). C, Z. compallens; Germany, Niedersachsen, U. de Bruyn 1693 (FR-026141). D, Z. confusa; Great Britain, Scotland, B. Coppins s. n. (FR-0068184). E, Z. expallens; USA, Alaska, C. Printzen 5078 (FR-0259478). F, Z. flavoleprosa; Russia, Altayski krai, E. Davydov 6792 (FR-0089689). Scales: A, B & D = 1 mm; C, E & F = 0.5 mm.

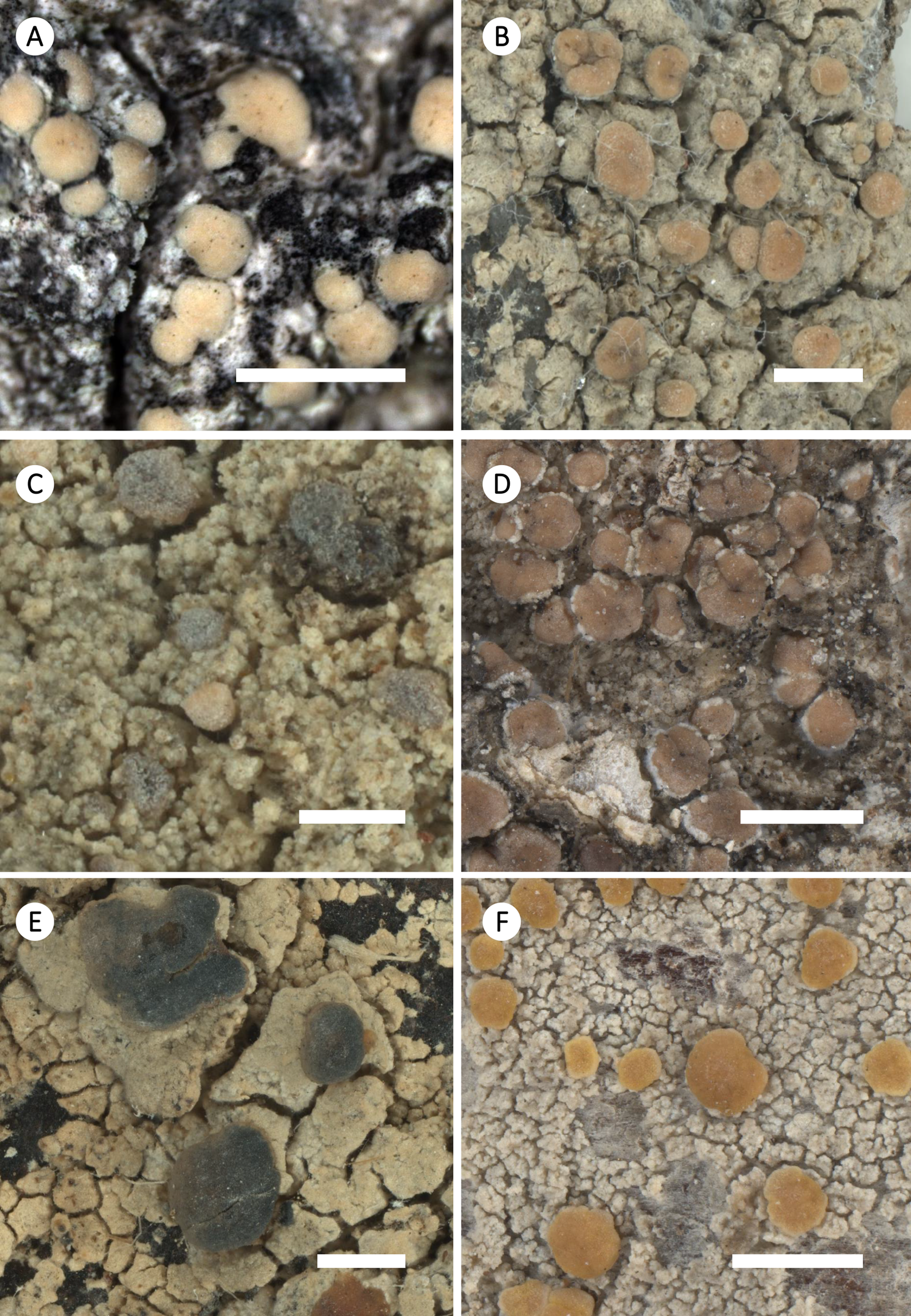

Figure 7. Habitus of selected species of Zeora (cont.). A, Z. helmutii; Australia, Tasmania, Kantvilas 460/11 (HO-563771; type). B, Z. orosthea; Great Britain, Scotland, B. Coppins 25566 (FR-0175440; L428). C, Z. straminea; Germany, Nordrhein-Westfalen, J. Lahm 1829 (FR-0050171). D, Z. strobilina; Ecuador, Galápagos Isl., W. Weber Exs. 138 (FR-0059930). E, Z. sulphurea; Greece, South Aegean, K. Fritsch 12242 (FR-0080152). F, Z. symmicta; Russia, Altayski krai, C. Printzen 8334 (FR-0068138). Scales: A & B, D–F = 1 mm; C = 0.5 mm.

Thallus thin and partially endophloedal to thick, episubstratal, with a granular, farinose to entirely sorediate surface and with a pale yellow, yellow-green to mint green, bluish/greyish yellow or yellowish brown thallus surface, rarely whitish, sometimes with a black hypothallus. Photobiont chlorococcoid algae.

Apothecia rarely lacking, flat to convex, some with white pruina on yellow to brown discs, sometimes darkening with age. Zeora compallens and Z. stanislai have so far only been found sterile. Margin biatorine or lecanorine, typically excluded, with granules typically dissolving in KOH (except Z. strobilina, with granules insoluble in KOH but soluble in HNO3), without large oxalate crystals. Epihymenium with a large variety of pigmentation or hyaline, with crystals dissolving in KOH. Hymenium hyaline to pale yellow to yellowish brown. Subhymenial layers hyaline (except Z. expallens and Z. strobilina that can have subhymenial layers pigmented pale yellow). Paraphyses simple to sparsely branching and anastomosing, without swollen apices or weakly capitate. Asci Lecanora-type (sensu Honegger Reference Honegger1978), 8 spores per ascus (except Z. strobilinoides with (12–)16(–32) spores). Ascospores hyaline, simple, narrowly ellipsoid to broadly ellipsoid, occasionally 1-septate.

Conidia as leptoconidia sensu van den Boom & Brand (Reference van den Boom and Brand2008), filamentous, frequently curved, simple 12–25 × 0.5–1 μm.

Chemistry

C± yellow to orange; K± faint yellow to yellow-brown; KC± faint yellow to yellow-brown; Pd± orange-red. Usnic acid and zeorin are the usual major substances; atranorin, arthothelin, α-collatolic acid, decarboxysquamatic acid, fumarprotocetraric acid, gangaleoidin, norstictic acid, placodiolic acid, skyrin or thiophanic acid are present in some species, sometimes only in trace amounts. Additionally, a range of unknown substances has been reported for several species, such as ‘expallens-unknown’ or ‘flavoleprosa-unknown’, compounds detected in Z. expallens (Tønsberg Reference Tønsberg1992) and Z. flavoleprosa (Tønsberg Reference Tønsberg1992; Czarnota et al. Reference Czarnota, Flakus and Printzen2009) respectively. Printzen (Reference Printzen2001) also reported an unidentified xanthone for Z. confusa.

Substratum

Most species grow on bark or wood, some are saxicolous on siliceous rocks.

Distribution

Subcosmopolitan; species of this genus are present on almost all continents, except for Antarctica.

List of species

Zeora aitema (Ach.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858689

Lecidea aitema Ach., K. Vetensk-Acad. Nya Handl. 29, 261 (1808).—Lecanora aitema (Ach.) Hepp, Flecht. Europ., no. 69 (1853).

(Fig. 6A)

Zeora atrosulphurea (Wahlenb.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858690

Lichen atrosulphureus Wahlenb., Fl. Lapp., 411 (1812).—Lecanora atrosulphurea (Wahlenb.) Ach., Syn. Meth. Lich. (Lund), 149 (1814; as ‘atro-sulphurea’).

(Fig. 6B)

Zeora austrocalifornica (Lendemer & K. Knudsen) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858691

Lecanora austrocalifornica Lendemer & K. Knudsen, Opuscula Philolichenum 6, 73 (2009).

Zeora compallens (Herk & Aptroot) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858692

Lecanora compallens Herk & Aptroot, Lichenologist 31(6), 544 (1999).

(Fig. 6C)

Zeora confusa (Almb.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858693

Lecanora confusa Almb., Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakad. Avhandl. Natursk. 11, 72 (1955).

(Fig. 6D)

Zeora expallens (Ach.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858694

Lecanora expallens Ach., Lich. Univ., 374 (1810).

(Fig. 6E)

Zeora flavoleprosa (Tønsberg) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858695

Lecanora flavoleprosa Tønsberg, Sommerfeltia 14, 161 (1992).

(Fig. 6F)

Zeora helmutii (Pérez-Ort. & Kantvilas) Pérez-Ort., L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858696

Lecanora helmutii Pérez-Ort. & Kantvilas, Herzogia 31(1), 643 (2018).

(Fig. 7A)

Zeora orosthea (Ach.) Flot.

Lichen orostheus Ach., Lich. suec. prodr. (Linköping), 38 (1799 [1798]).—Lecanora orosthea (Ach.) Ach., Lich. Univ., 400 (1810).

(Fig. 7B)

Zeora parasymmicta (B. G. Lee & Hur) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858697

Lecanora parasymmicta B. G. Lee & Hur, MycoKeys 84, 172 (2021).

Zeora pulverulenta (Müll. Arg.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 859417

Lecanora pulverulenta Müll. Arg., Nuovo G. Bot. Ital. 23(1), 124 (1891).

Zeora stanislai (Guzow-Krzem., Łubek, Malíček & Kukwa) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858700

Lecanora stanislai Guzow-Krzem. et al., in Guzow-Krzemińska et al., Phytotaxa 329(3), 205 (2017).

Zeora straminea (Stenh.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858701

Biatora straminea Stenh. K. svenska Vetensk-Akad. Handl., ser. 3 34, 196 (1846).—Lecanora sublivescens (Nyl.) Arnold, Flora 67, 336 (1884).

(Fig. 7C)

Notes

As stated in Weber et al. (Reference Weber, Arup and Schiefelbein2023), Biatora straminea is effectively the oldest valid name for Lecanora sublivescens (Nyl.) Arnold but, at species level and within Lecanora, the epithet ‘straminea’ was blocked by the older Lecanora straminea Ach. Within Zeora, however, this combination is available.

Zeora strobilina (Spreng.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858698

Parmelia strobilina Spreng., Syst. veg., Ed. 16 4(1), 300 (1827).—Lecanora strobilina (Spreng.) Kieff., Bull. Soc. Hist. Nat. Metz 19, 74 (1895).

(Fig. 7D)

Zeora strobilinoides (Giralt & Gómez-Bolea) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858699

Lecanora strobilinoides Giralt & Gómez-Bolea, Lichenologist 23(2), 107 (1991).

Zeora sulphurea (Hoffm.) Flot.

Verrucaria sulphurea Hoffm., Descr. Adumb. Plant. Lich. 1(2), 56 (1790).—Lecanora sulphurea (Hoffm.) Ach., Lich. Univ., 339 (1810).

(Fig. 7E)

Zeora symmicta (Ach.) L. M. Weber & Ivanovich-Hichins comb. nov.

MycoBank No.: MB 858702

Lecanora varia var. symmicta Ach., Lich. Univ., 379 (1810; as L. varia θ L. symmicta).—Lecanora symmicta (Ach.) Ach., Syn. Meth. Lich. (Lund), 340 (1814).

(Fig. 7F)

Notes

Discussions by Kantvilas & LaGreca (Reference Kantvilas and LaGreca2008), LaGreca & Lumbsch (Reference LaGreca and Lumbsch2013) and Weber et al. (Reference Weber, Arup and Schiefelbein2023) indicate that Zeora symmicta might constitute an aggregate of various species or a ‘species complex’. It may therefore be helpful in a future taxonomic revision of Zeora to circumscribe this species based on molecular genetic analyses and to epitypify Zeora symmicta s. str. to a specimen with DNA sequences.

There are some additional species that most likely belong to Zeora but we hesitate to assign them to this genus due to a lack of molecular data: Lecanora americana (B. de Lesd.) Printzen (nom. illeg., non Lecanora americana (B. de Lesd.) Zahlbr.; if this taxon were eventually moved into Zeora, the epithet americana would be available), Lecanora brucei Printzen, L. confusoides Bungartz & Printzen, Lecanora conizella Nyl., L. cupressi Tuck. ex Nyl., L. fluoroxylina Aptroot & M. F. Souza, L. orae-frigidae R. Sant., L. perconfusa Printzen, L. sabinae Hern.-Padr. & Vänskä, L. simeonensis K. Knudsen & Lendemer, L. subaureoides Aptroot & Bungartz, L. substrobilina Printzen, L. subtecta (Stirt.) Kantvilas & LaGreca, and L. terpenoidea Bungartz & Elix.

For more detailed descriptions of all species in the List of Species, see Giralt & Gómez-Bolea (Reference Giralt and Gómez-Bolea1991), Tønsberg (Reference Tønsberg1992), van Herk & Aptroot (Reference van Herk and Aptroot1999), Printzen (Reference Printzen2001), Kantvilas & LaGreca (Reference Kantvilas and LaGreca2008), LaGreca & Lumbsch (Reference LaGreca and Lumbsch2013), Guzow-Krzemińska et al. (Reference Guzow-Krzemińska, Łubek, Malíček, Tønsberg, Oset and Kukwa2017), Pérez-Ortega & Kantvilas (Reference Pérez-Ortega and Kantvilas2018), Lee & Hur (Reference Lee and Hur2021) and Weber et al. (Reference Weber, Arup and Schiefelbein2023).

The genus Lecanoropsis M. Choisy ex Ivanovich and associated taxa

In our phylogenetic analysis, the monophyly of Lecanoropsis confirms the results published by Ivanovich et al. (Reference Ivanovich, Weber, Palice, Hollinger, Otte, Sohrabi, Sheehy and Printzen2025). Lecanoropsis can then be circumscribed as corticolous and lignicolous crustose lichens with an endosubstratal to poorly developed episubstratal (except L. coracina Ivanovich et al.), esorediate thallus, lecanorine apothecia (except for L. anopta (Nyl.) Ivanovich & Printzen, which forms more or less biatorine mature apothecia), a corticate thalline margin without large KOH-insoluble crystals, several types of conidia (the most conspicuous are called macroconidia), and containing dibenzofuran-derivatives such as isousnic and usnic acid, but without atranorin or psoromic acid.

Taxa with morphological and chemical similarities such as Lecanora mughicola and L. prolificans (clade between Lecanoropsis and Straminella, see Figs 1 & 2), previously thought to belong in the Lecanora saligna-group, cluster in another well-supported monophyletic clade together with Lecanora laxa and Rhizoplaca mcleanii. They produce isousnic and usnic acid but lack macroconidia.

Rhizoplaca mcleanii is a saxicolous Antarctic species that develops a dark brown-grey or black squamulose, peltate to foliose umbilicate thallus, with numerous lecanorine apothecia that are typically marginal, immersed at first and becoming sessile later, producing broad ellipsoid spores with thick walls (Castello Reference Castello2010). Rhizoplaca mcleanii was first transferred from Lecanora into Rhizoplaca by Castello (Reference Castello2010), and later to Lecanoropsis by Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019) on the basis of a single locus (ITS) in their ML analysis. The thallus morphology in R. mcleanii matches the circumscription of Rhizoplaca (Arup & Grube Reference Arup and Grube2000), which makes its placement in Lecanoropsis dubious. Additionally, in Kondratyuk et al. (Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019), the transfer of R. mcleanii into Lecanoropsis receives no statistical support. According to their results (see Kondratyuk et al. Reference Kondratyuk, Lőkös, Jang, Hur and Farkas2019: fig. 2), Lecanoropsis forms a non-supported clade separated from Rhizoplaca mcleanii. Since the morphology of R. mcleanii does not match that of Lecanoropsis, and in our analysis the specimen of R. mcleanii appeared outside of Lecanoropsis, we have no reason to support the transfer of Rhizoplaca mcleanii into Lecanoropsis. Therefore, for now we suggest retaining the name Rhizoplaca mcleanii (C. W. Dodge) Castello.

The genus Myriolecis Clem., Lecanora utahensis H. Magn. , and a brief commentary on the genus name Polyozosia A. Massal.

Myriolecis (= Polyozosia A. Massal., formerly the Lecanora dispersa-group) forms a well-supported clade close to Protoparmeliopsis in our analysis. These results are consistent with phylogenies published by Śliwa et al. (Reference Śliwa, Miadlikowska, Redelings, Molnar and Lutzoni2012, Reference Śliwa, Mazur and Wirth2023) and Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Leavitt, Zhao, Zhang, Arup, Grube, Pérez-Ortega, Printzen, Śliwa and Kraichak2015). The Lecanora dispersa-group was treated in detail by Śliwa (Reference Śliwa2007). According to these authors, the genus comprises corticolous or saxicolous crustose lichens, with a typically endosubstratal, more rarely well-developed thallus and lecanorine apothecia (except for M. persimilis (Th. Fr.) Śliwa et al., which appears to have biatorine-like apothecia) with a thick persistent margin and becoming conspicuously crenulate with time. Species of Myriolecis produce a wide range of xanthones, with some also producing gyrophoric acid (e.g. M. salina (H. Magn.) Śliwa et al.) or pannarin (e.g. M. dispersa (Pers.) Śliwa et al.) as minors. Several taxa do not produce any compound detectable by TLC (e.g. Myriolecis sambuci (Pers.) Clem.).

Lecanora utahensis H. Magn. is a saxicolous species often found on sandstone rocks and soil in the Sonoran Desert (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Lumbsch, Messuti, Printzen, Śliwa, Nash, Nash, Ryan, Diederich, Gries and Bungartz2004). It shares the majority of characters that circumscribe Myriolecis, except that it does not produce xanthones but rather isousnic acid. Ryan et al. (Reference Ryan, Lumbsch, Messuti, Printzen, Śliwa, Nash, Nash, Ryan, Diederich, Gries and Bungartz2004) placed L. utahensis in the L. dispersa-group, whereas Śliwa (Reference Śliwa2007) indicated that it does not belong there due to its chemistry. Later, however, Śliwa et al. (Reference Śliwa, Mazur and Wirth2023: 378) described Myriolecis suevica V. Wirth et al., which produces isousnic acid like Lecanora utahensis, thereby expanding the concept of Myriolecis. Our results show a close phylogenetic relationship between L. utahensis and the species of Myriolecis included in our dataset. As pointed out by Śliwa et al. (Reference Śliwa, Mazur and Wirth2023), this genus comprises several subclades, one of which conforms to Polyozosia, a name resurrected only recently by Kondryatyuk et al. (2019) as the older and valid name for Myriolecis. According to Massalongo (1855) Polyozosia originally comprised Polyozosia ?? aipospila (Wahlenb.) A. Massal., P. poliophaea (Wahlenb.) A. Massal. and P. spodophaea (Wahlenb. ex Ach.) A. Massal. (as ‘spadophaea’), and was typified by Hafellner (Reference Hafellner1984) based on Polyozosia poliophaea. We refrain from recombining Lecanora utahensis into Myriolecis because it is currently unclear to which of these subclades L. utahensis belongs.

Acknowledgements

This work benefited from the sharing of expertise within the DFG priority program SPP 1991 ‘Taxon-Omics’ and support from DFG grant PR 567/19–1 to CP. CI was partially supported by the Goethe Research Academy for Early Career Researchers (GRADE) during this research. LW was financially supported by the Finnish Ministry of the Environment as part of the PUTTE research program 2021–2022, the Volkswagen Foundation (project id 98060) and the Nessling Foundation. ZP acknowledges the continuous support of the long-term program of the Czech Academy of Science (RVO no. 67985939). The authors would like to thank Mikhail Andreev, Frank Bungartz, Rainer Cezanne, Sergey Chesnokov, Evgeny Davydov, Christian Dolnik, Marion Eichler, Alan Fryday, Jason Hollinger, Sophia Kern, Liudmila Konoreva, Scott LaGreca, Bruce McCune, Volker Otte, Ulf Schiefelbein, Matthias Schultz, Matthias Schwarz, Steve Sheehy, Dietmar Teuber, Roman Türk and Li-Song Wang for providing specimens. CI would also like to thank the staff at H, especially Leena Myllys, Annina Kantelinen and Teuvo Ahti, for hosting him and assisting in the work. Additionally, the authors thank Juraj Paule for his help with the mitochondrial genome assembly, and Ulf Arup for helpful comments on the Lecanora symmicta-group. This research paper is part of the PhD dissertation of CI.

Author ORCIDs

Cristóbal Ivanovich, 0000-0002-2810-0084; Lilith Weber, 0000-0002-6856-8095; Lijuan Li, 0000-0003-1048-1971; Steven Leavitt, 0000-0002-5034-9724; Lucia Muggia, 0000-0003-0390-6169; Zdeněk Palice, 0000-0003-4984-8654; Sergio Pérez-Ortega, 0000-0002-5411-3698; Mohammad Sohrabi, 0000-0003-4864-3905; Christian Printzen, 0000-0002-0871-0803.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.