Introduction

In the current refugee migration into Europe, disaster relief agents have to deal with an unprecedented 1.256 million asylum applications in 2015 in EU28 alone; followed by 1.206 applications in 2016Footnote 1 (Eurostat 2019). About 1.3 million applications a year is one and a half times of the previous peak of 850,000 in 1992, i.e., the large refugee movement following the breakup of the bipolar order that dominated Europe since the 1950s (see UNHCR 2000; Dustmann et al. Reference Dustmann, Fasani, Frattini, Minale and Schönberg2017). The current movements are essentially a consequence of the events following the 2001 bombings of the twin towers in New York and the ‘Arab Spring’ uprising in the Middle East (see Dustmann et al. Reference Dustmann, Fasani, Frattini, Minale and Schönberg2017, 2). Small countries like Austria with a total population of 8.7 million and a relatively large refugee share provide an excellent example of effects of this refugee migration. The arrival of nearly 500,000 refugees, all in the autumn of 2015—representing an exceptional situation—posed a severe challenge for policy makers and disaster relief organizations alike. Even though formally designated disaster relief organizations made assiduous efforts, they could not fully alleviate the suffering of refugees. There was obviously a gap in the disaster response (Simsa et al. Reference Simsa, Herndler, Totter, Theuvsen, Andessner, Gmür and Greiling2017; Roth Reference Roth2017, 6; Maduz and Roth Reference Maduz and Roth2017, 2 ff.; Gratz Reference Gratz2016, 167 ff.), which indicates that they were not capable of reshaping and restoring the prevailing physical and social environment (Smith and Wenger Reference Smith, Wenger, Rodriguez, Quarantelli and Dynes2007, 246). Local individuals and groups became aware of this gap and spontaneously came to disaster sites for providing relief (Simsa et al. Reference Simsa, Rameder, Aghamanoukjan and Totter2018; Simsa Reference Simsa2017; Frühwirth and Lachmayer Reference Frühwirth and Lachmayer2015).

The problems of the formal relief organizations can be particularly attributed to the refugee migration’s characterization as a large-scale disasterFootnote 2 (Maduz and Roth Reference Maduz and Roth2017; Gratz Reference Gratz2016, 167). The nature of the disaster ‘leads to emergence and requires the participation of multiple actors whose legitimacy is derived from alternative authority structures’ (Drabek and McEntire Reference Drabek and McEntire2003, 108). Majchrzak et al. (Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 147) add ‘in disasters of large scale and scope, formal plans break down in unexpected ways as the disaster unfolds.’Footnote 3 This is because plans, organizational structure, and capacities of disaster relief organizations are appropriate—guaranteeing both stability and flexibility—only for a time-restricted emergency case, rather than for extended periods (Meyer and Simsa Reference Meyer and Simsa2018, 1166). Particularly, the command–control structures hindered creativity and adaptive behaviors of employees (McManus et al. Reference McManus, Seville, Vargo and Brunsdon2008; Marcum et al. Reference Marcum, Bevc and Butts2012), which would have been needed to address unexpected events (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 149). Governmental restraints compounded the insufficiencies of plans and structures (Gratz Reference Gratz2016). Moreover, political directives were also unstable (‘from welcome culture to border-closed strategy’) (Maduz and Roth Reference Maduz and Roth2017, 2 ff.; Simsa Reference Simsa2017). In summary, formal disaster relief organizations, i.e. NPOs lacked an appropriate ‘overall plan’ and organizational structure as well as human resources. As well, on site emerging—or synonymously used ‘spontaneous,’ ‘unaffiliated,’ or ‘informal’—volunteers (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Shaw, Scully, Smith and Hieke2017; Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015) also struggled with providing relief, in the form of food, clothing, and shelter, or acting as interpreters (Maduz and Roth Reference Maduz and Roth2017). Even if they were very highly motivated and worked hard, a lack of coping mechanisms/framework for action and a lack of shared purpose about what to do, made their engagement inefficient, causing discouragement and also imposing emotional and physical constraints (Simsa et al. Reference Simsa, Rameder, Aghamanoukjan and Totter2018; c.f. Gardner Reference Gardner2013, 257).

In summary, formal disaster relief organizations, for example, NPOs, as well as emerging volunteers were challenged in regard to their ‘orientation’ because of a lack of a notion, how to proceed and organizational structure. Meyer and Simsa (Reference Meyer and Simsa2018, 1167) describe this situation as context showing that the inherent flexible structures of organizations were not sufficient to meet the challenges, requiring a necessary change to the structural organization. The environmental constraints associated with the migration disaster of 2015/16 gave cause for reconsidering the current disaster relief approaches and for reorienting toward new strategies to create sustainability in disaster response.

Existing research suggests that collaboration between nonprofit and other sectors is a fruitful approach to solve complex societal problems and to create value that benefits the partners and society (Al-Tabbaa et al. Reference Al-Tabbaa, Leach and March2014; c.f. Bryson et al. Reference Bryson, Crosby and Stone2006; Austin and Seitanidi Reference Austin and Seitanidi2012). In the disaster context, collaboration often emerges among the actors involved. Emergent collaboration, where participants voluntarily unite and respond to the environmental demands without having a central authority, requires contributions from multiple interdependent actors (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014; c.f. Dougherty and Dunne Reference Dougherty and Dunne2011). Emergent collaboration demonstrates a highly self-organizing character including, e.g., the development of superordinate goals or the deployment of a portable structure. Thus, ‘idiosyncratic local organizing actions’, predominately rooted in a lack of shared understanding (‘no overall plan’) at the beginning of the disaster, become more harmonized (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014).

Moreover, these collaborative performance efforts between NPOs and spontaneous volunteers play an important role for sustainable disaster relief because collaborative performance includes the mentioned development of goals, structures, etc. and thus the creation of a common understanding of the tasks as well as the responders perception as a collective (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014; Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007; Gardner Reference Gardner2013). Hence, emergent collaboration temporarily bridges the formal structures and the notion of how to proceed after the disaster and thus provides, as previously mentioned, sustainable disaster relief (recovery in original), referred to as the ‘process of restoring, rebuilding, and reshaping the physical, social, economic, and natural environment’ (Smith and Wenger Reference Smith, Wenger, Rodriguez, Quarantelli and Dynes2007, 246), whereby the focus was on reshaping in ‘refugee crisis’. The definition reflects the widely accepted dimensions of sustainability in disaster research (WCED 1987, 43).Footnote 4

In the case of the migration disaster, emergent collaboration between NPOs and emerging volunteers was observable in operations, (Roth Reference Roth2017, 7; Gratz Reference Gratz2016, 64 ff.),Footnote 5 such as complementary functions, for example, childcare or translation in collaboration with the Red Cross, or supplementary functions, for example, with Caritas, where emerging volunteers were entrusted with leadership functions in a new installed emergency unit (Meyer and Simsa Reference Meyer and Simsa2018). In particular, the enablers of such emergent collaboration (or collaborative efforts) between NPOs and emerging volunteers need to be studied (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016, 2043; Strandh and Eklund Reference Strandh and Eklund2017).Footnote 6

Since cognitive and relational resources are supposed to play an important role in disaster response, in general, (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017), we draw on cognitive, relational, and structural social capital as access, mobilization, learning, and hence performance-enabling resource stock (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017). And, due to the fact that disaster management is largely organized in teams (Subramaniam et al. Reference Subramaniam, Ali and Mohd Shamsudin2010; c.f. Ford and Schmidt Reference Ford and Schmidt2000), we correspondingly address the following research question: which social capital-based components underpin collaborative disaster relief performance on a team level?

We propose that collaborative disaster relief performance as emerging efforts between NPOs and volunteers on the team level is social capital-driven (Adler and Kwon Reference Adler and Kwon2002; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Considering the context, we have chosen the country of Austria, since it has to deal with a relatively large refugee share and thus provides an excellent area for disaster research. We present the results of a regression analysis among emerging volunteers and NPO (paid and voluntary) members deployed in refugee camps all across Austria.

Our paper makes the following contributions: Firstly, we contribute to the existing disaster research with focus on volunteering by illustrating that emergent collaboration between NPOs and emerging volunteers based on social capital represents an appropriate approach to enhance performance and thus to jointly respond to social disasters. Due to the fact that emergent collaborative efforts go along with the creation of a shared understanding of goals, tasks, structure, and the responders as collective, they also contribute to sustainability in disaster relief. By choosing refugee migration as our research context, we enrich research particularly in the context of social disasters that are less studied than natural disasters. Secondly, by illustrating which social capital components affect collaborative efforts of NPOs and volunteers on a team level, the study refines social capital components ‘suitable’ for disaster relief and thus enhances the small body of research discussing behavioral enablers of collaborations in the disaster context. This refinement not only includes the specification of the single social capital components, but also the interdependences between the different components.

The paper is structured as follows. Having illustrated the implications of refugee migration on formal disaster agents in the nonprofit sector, we briefly delineate emerging collaboration as our conceptual framework in the following section and point out the research gap. We then show how our research model explains the effects of social capital on these emergent collaborative efforts. Thereafter, we present the research design and the empirical findings of our survey study based on a regression analysis. We finally summarize the paper, discuss the results, draw conclusions, and provide implications for practice and theory.

Emergent Collaboration as Conceptual Framing of Disaster Relief

There is consensus that disaster relief in large-scale disasters requires a kind of collaboration between formally designated relief organizations and emerging volunteers (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017; Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015; Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007; Roth Reference Roth2017; Gratz Reference Gratz2016). Collaboration refers to a union of various agents who try to achieve an objective based on their common strengths. Synonymously used terms are ‘partnership’, ‘cooperation’, ‘alliance’, or ‘network’ (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Haynes and Hudson2010, 164; Nolte and Boenigk Reference Nolte and Boenigk2014, 149 f.).

With regard to the formative process of emergent collaboration in the disaster context, we basically follow Beck and Plowman (Reference Beck and Plowman2014). Based on the Columbia Space Shuttle disaster response, they develop a grounded theory for temporary emergent collaborations relying on complexity theory. Self-organization and emergence are the central features of complex adaptive systems (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014, 1246). A disaster causes a far-from-equilibrium situation in which conditions of nonlinear interactions (e.g., breakdown of disaster relief plans) promote emerging, self-organizing behavior, and structures. According to Beck and Plowman (Reference Beck and Plowman2014) these self-organizing actions include (1) creating superordinate goals, (2) collocating, (3) deploying portions of a portable structure, and (4) experimenting. The self-organizing activities lead to a deepening of trust and collective identity (from ‘situation-based swift trust’ and ‘social identity’ to ‘relation-based trust’ and ‘collective identity’) that are critical to emergent collaboration. Beck and Plowman (Reference Beck and Plowman2014, 1244) conclude that as soon as members feel trust and know each other, experimenting becomes more ‘ordered’.

In regard to self-organizing activities, the development of superordinate goals is particularly important because there is no overall plan to which emerging collaborations can refer. Thus, developing goals essentially supports the responders in their ability to interact and experiment. Beck and Plowman (Reference Beck and Plowman2014, 1247) note that ‘achievement of common goals strengthened the responders’ shared sense of purpose and understanding of who they were as collective’. Also, Sawyer (Reference Sawyer2000) emphasizes that emergent activities are based on shared structures of meaning between collaborating social agents. Collaboration activities can also be characterized by a ‘try it attitude’ (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014, 1241). This is, in particular, due to the assumption that urgency as well as the dynamics of the disaster require responders to combine resources innovatively and adapt processes and structures quickly (Simsa et al. Reference Simsa, Herndler, Totter, Theuvsen, Andessner, Gmür and Greiling2017 331 f.; Simsa Reference Simsa2017, 92). Thus, innovating and experimenting can be regarded as ‘key features’ of emerging disaster activities (Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015, 362).

Similar to Beck and Plowman (Reference Beck and Plowman2014), Majchrzak et al. (Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 150) also refer to a ‘learn-by-doing […] action-based model of coordinated problem solving’ of emergent behavior. Learning by doing involves sensemaking and improvisation rather than spending time deliberating on future consequences of actions. Moreover, this form of coordinated problem solving is based on taking advantage of emerging opportunities. In reference to emergent collaboration between NPOs and emerging volunteers in particular (‘spontaneous volunteering under the auspices of a civil society organization’), Simsa et al. (Reference Simsa, Rameder, Aghamanoukjan and Totter2018) also emphasize the ‘try it attitude,’ i.e., the improvisational character of action of emerging volunteers. Basic elements of coordination—either self-defined or defined by NPOs—are necessary for an efficient response, though. Thus, scholars consider a structured self-organization, ‘which means to give space to self-organized processes but enable their efficiency by basic structures, clear (although often very short time) goals, and organization’ (Simsa et al. Reference Simsa, Rameder, Aghamanoukjan and Totter2018, 13) as appropriate. This is in line with Meyer and Simsa (Reference Meyer and Simsa2018), who state that improvisation depends on the structure of the relief organization in the sense that a relief organization, e.g., NPO, focuses on its core fields of action, for example, providing ambulances, but also loosens its regulations and thus provides the ‘space’ for freedom of action for volunteers. They define this process as a second-order learning phase, which happened when swift reactions of relief organizations (first-order learning) were not sufficient to meet the challenges of disaster.

In summary, ‘learn-by-doing’ is an inherent characteristic of emergent collaboration. Researchers from various disciplines (e.g., Helfat Reference Helfat1997; Cohen and Levinthal Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990) claim that there is a link between learning and the resource, respectively, knowledge stock of the agents (Kang and Snell Reference Kang and Snell2009). Cognitive, relational, and emotional resources are, in general, supposed to be an appropriate resource stock and enabler of disaster response (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017).

Given our interest in exploring further what enables emergent collaboration between NPOs and volunteers, we concentrate our literature review on disaster management research, in general, with special focus on disaster volunteering as a subfield. This is, in particular, due to the point of view that disasters represent a ‘unique operational environment’ due to their ‘level of unpredictability, urgency, and reconfigurability’ (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 149). In general, emergent phenomena in the disaster context have attracted the interest of disaster research for the last three decades (Drabek and McEntire Reference Drabek and McEntire2003). In summary, there is scarce research dealing with the enablers of emergent collaborations in disaster context (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014, 1235; Gardner Reference Gardner2013).

A research stream that is strongly related to (or even identical with) emergent collaboration is research dealing with emergent multi-organizational networks (Marcum et al. Reference Marcum, Bevc and Butts2012; Day Reference Day2014) or ad-hoc networks in a disaster context (Nolte and Boenigk Reference Nolte and Boenigk2014). Whereas the former primarily discusses enablers on the network level, the later primarily deals with enablers of networks between public and nonprofit organizations and not with a specific focus on volunteers. There is also a closely linked, small body of literature discussing emergent response groups, which are ‘collectives of individuals who use nonroutine resources and activities to apply to nonroutine domains and tasks, using nonroutine organizational arrangements’ (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 150) as well as the cooperation of such groups with other disaster relief actors. This research deals predominantly with the existence, identification of characteristics, and value of emergent response groups as well as with preconditions of disaster response (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007). Inter alia, dynamics and coordination of emergent response groups or local ventures has recently aroused the interest of researchers, but with few exceptions, this research takes a predominantly sociological rather than a management point of view (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007; Williams and Shepherd Reference Williams and Shepherd2016).

As the literature review of Moshtari and Gonçalves (Reference Moshtari and Gonçalves2017) shows, there is another research stream principally discussing enablers of collaboration between humanitarian organizations in the disaster context. This literature, though, neither has a specific focus on emerging phenomena nor does it particularly refer to the specific collaboration between nonprofit organizations and volunteers. Moshtari and Gonçalves (Reference Moshtari and Gonçalves2017) claim that this research would benefit from new insights, such as how behavioral issues impact collaboration.

Finally, the literature stream focusing on disaster volunteering (Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015; Strandh and Eklund Reference Strandh and Eklund2017; McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016; Twigg and Mosel Reference Twigg and Mosel2017), discusses the collaboration between NPOs and emergent volunteers predominantly from a normative management perspective, for example, providing typologies or general policies for collaboration or phases of collaboration (Helsloot and Ruitenberg Reference Helsloot and Ruitenberg2004; Boin and Bynander Reference Boin and Bynander2015; Strandh and Eklund Reference Strandh and Eklund2017). It thus lacks a profound discussion of conditions and capacities to provide collaborative relief (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016). Hence, enablers of emergent collaboration need to be studied (McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016, 2043; Strandh and Eklund Reference Strandh and Eklund2017). Also, ‘further research is needed to examine how […] structures are changing to account for informal volunteerism’ (Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015, 366). Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that most of the disaster volunteering research refers to natural disasters and not to social disasters. Social disasters rudimentarily differ from natural ones, referring, in particular, to social disasters’ ongoing peaks and changes, depending on (governmental) decisions and lack of consensus about the nature of disasters or approaches to avoid them (Simsa et al. Reference Simsa, Rameder, Aghamanoukjan and Totter2018, 5; c.f. Harris et al. Reference Harris, Shaw, Scully, Smith and Hieke2017).

In summary, our literature review shows that there is a general need for research regarding collaboration between NPOs and emerging volunteers. Emergent collaboration is an appropriate approach, but one that is generally understudied and needs thoughtful research of its enablers. In reference to behavioral enablers, there is a lack of research discussing collaboration in humanitarian disaster aid in general. In the following chapter, we introduce the concept of social capital as an enabler of emergent collaboration.

Social Capital Formation in Emergent Collaborative Efforts: Research Model and Hypotheses

As previously mentioned, we refer to a ‘learn-by-doing […] action-based model of coordinated problem solving’ (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 150) and claim—following researchers from various disciplines (e.g., Helfat Reference Helfat1997; Cohen and Levinthal Reference Cohen and Levinthal1990; Kang and Snell, Reference Kang and Snell2009)—that social capital substantially affects the emergent collaboration (or collaborative efforts) between spontaneous volunteers and NPOs. Social Capital (SC) refers to the mobilization of available resources or assets through a social structure, for example, ongoing relationships and corresponding interactions among individuals or organizations (Hsu and Wang Reference Hsu and Wang2012, 5; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Following Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998), social capital facilitates knowledge acquisition and exploitation by affecting the conditions that are necessary to exchange and combine existing knowledge (Yli-Renko et al. Reference Yli-Renko, Autio and Sapienza2001). The term ‘social capital’ has its origins in community studies in which it highlighted the crucial importance of networks of personal relationships as the basis for trust, cooperation, and collective action for the survival and functioning of city neighborhoods (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998; Jacobs Reference Jacobs1965). Social capital theory proposes that networks of relationships constitute a valuable resource for running social matters (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). The networks with their contacts and connections also make other resources available. ‘Weak ties’ (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973) allow network members to gain access to information and opportunities. We follow Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998) in defining social capital as both the network and the assets may be mobilized through that network (see also Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu and Richardson1986; Burt Reference Burt1992).

Similarly, Kang and Snell (Reference Kang and Snell2009) define social capital as ‘overall patterns of relationships among employees (i.e., internal, global networks), which serve as an important mechanism for knowledge exchange and combination within the firm’ (69). Thus, the individual’s knowledge stock is enriched by the experience, explicit, and tacit knowledge of his/her team. Research on social capital also seems to play a key role in transforming knowledge into innovation (Subramaniam and Youndt Reference Subramaniam and Youndt2005). There are numerous accounts that social capital strongly affects organizational outcomes (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998; Kostova and Roth Reference Kostova and Roth2003) as well as civic engagement (Hommerich Reference Hommerich2015). Van der Vegt et al. (Reference Van Der Vegt, Essens, Wahlström and George2015, 973) state that particularly in disaster contexts, relationships and social networks in which responders are embedded strongly impact the availability and accessibility of resources and capabilities for adaptive response.

Because we analyze collaborative disaster relief performance on a team level, we draw on an interpersonal perspective of social capital (see Lin Reference Lin2001) and focus on structural social capital, cognitive social capital, and relational social capital as dimensions of social capital (Adler and Kwon Reference Adler and Kwon2002; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Although the separation of these three forms of social capital makes sense from an analytical perspective, they are highly interrelated. In the following paragraphs, we introduce these three forms of social capital and their connection to our research context of emergent collaborative efforts in disaster relief, as well as our hypotheses.

Structural social capital (SSC) relates to configurations and structures of social relationships and discusses how to reach whom (Burt Reference Burt1992), i.e., how individuals are connected as well as how frequently they interact with each other (Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). Structural embeddedness (Granovetter Reference Granovetter, Nohria and Eccles1992) is a key to understand the characteristics of the network of relations. The linkages allow the network members access to resource exchange with other members (Hatak et al. Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016). Some authors emphasize the role of a dense network structure for social capital building (Coleman Reference Coleman1990). Particularly, ‘interaction (frequency)’ has a great influence on the creation as well as the coordination of the organizational capability because it provides the basis for knowledge sharing. The more individuals interact, the deeper and more intensively people are involved in topics (Mäkelä et al. Reference Mäkelä, Sumelius, Höglund and Ahlvik2012, 1466 f.), which in turn facilitates the completion of tasks for which they are responsible. Hence, we suggest:

- H 1 (+ )

-

The higher the interaction frequency between responders is, the higher is the collaborative disaster relief performance.

Cognitive social capital (CSC) illustrates, together with relational social capital, the content-related dimension of social capital. Cognitive social capital refers to the ‘cognitive similarity’ of individuals in terms of shared codes, shared mental models, common visions and goals including, for example, a common language, narratives, and (proper) collective actions (Tsai and Ghoshal Reference Tsai and Ghoshal1998; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998; see also Nolte and Boenigk Reference Nolte and Boenigk2014). Cognitive social capital is also considered to be an essential lever for knowledge sharing. It enhances the ability for knowledge exchange (Kang and Snell Reference Kang and Snell2009) because it represents the cognitive reference frame individuals can draw on for perceiving and interpreting the others’ knowledge. In the case of a lack of cognitive social capital, individuals have problems in recognizing knowledge because they cannot process it (Carlile Reference Carlile2004; Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010, 97 f.). A lack of cognitive similarity also may result in attribution errors, misunderstandings, increased communication endeavor, and inefficiency in how knowledge is shared and used (DeSanctis and Monge Reference DeSanctis and Monge1999). The combination of disaster context, fluid team composition, and changing tasks of emergent response teams may restrict the evolvement of cognitive similarity (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007; Drabek and McEntire Reference Drabek and McEntire2003). Following these arguments and based on the operationalization of cognitive social capital in ‘common professional experience’ and ‘avoidance of misunderstanding,’ we suggest that

- H 2a (+ )

-

The more distinctive common professional experience is, the higher is the collaborative disaster relief performance.

- H 2b (+ )

-

As mutual understanding is enhanced, the better is the collaborative disaster relief performance.

Relational social capital describes the kind of personal relationships individuals have due to their interactions (Granovetter Reference Granovetter, Nohria and Eccles1992). It symbolizes ‘the capability for resource exchange’ (Andrews Reference Andrews2010, 586) between the collaborating individuals. Relational social capital relates to assets such as trust as well as felt obligations and expectations embedded in these relationships (Tsai and Ghoshal Reference Tsai and Ghoshal1998; Nahapiet and Ghoshal Reference Nahapiet and Ghoshal1998). We focus on ‘emotional intensity’ and ‘intimacy (multiplicity)’ as indicators of relational social capital (Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010).

If individuals enjoy emotional closeness in the team, they are more willing to support the other team members, for example, by providing explanations to their colleagues (e.g., what to do and the underlying reasoning) or even helping the others in applying the knowledge (Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010, 97). Intimacy (or multiplicity of relationships) refers to the fact that the relationships go beyond professional level and also affect private life. Multiplicity can result in a distinctive position of an individual in the other members’ life, which provides the individual with an extra relational level (in addition to the work-life) for influencing this colleague. Thus, the individual can switch between these two levels in order to influence the other one. In sum, multiplicity of relations is supposed to improve the exchange of knowledge (Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010, 93). Intimacy also enhances motivation to share knowledge due to mutual confidence (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973). Mirroring the arguments above, we put forth the following hypotheses:

- H 3a (+ )

-

The more emotionally intense relationships are, the better is the collaborative disaster relief performance.

- H 3b (+ )

-

The more intimate the relationships are, the better is the collaborative disaster relief performance.

In addition to the analysis of separate effects of social capital components on collaborative disaster relief performance, we are also interested in exploring, how the interactions between the different social capital components affect the collaborative efforts. As previously mentioned, structural social capital represents the basis or rather the access point to knowledge exchange (Mäkelä et al. Reference Mäkelä, Sumelius, Höglund and Ahlvik2012; Hatak et al. Reference Hatak, Lang and Roessl2016). Hence, we focused on the interaction effects of ‘interaction frequency’ and (a) cognitive and (b) relational social capital components.

Frequent interaction is said to generate ‘rich communication channels,’ foster a common understanding and facilitate feedback loops (Maurer et al. Reference Maurer, Bartsch and Ebers2011, 162; see also Tortoriello and Krackhardt Reference Tortoriello and Krackhardt2010). In other terms, frequent interaction provides team members with (increased) opportunities for knowledge sharing and coordination, which facilitates them, contributing to their common professional background and avoiding misunderstandings. These aspects facilitate knowledge assimilation and transfer, which in turn fosters the collaborative disaster relief performance. Accordingly, we propose:

- H 4a (+ )

-

The interaction between interaction frequency and common professional experience affects the collaborative disaster relief performance positively.

- H 4b (+ )

-

The interaction between interaction frequency and avoidance of misunderstanding affects the collaborative disaster relief performance positively.

In line with this argument, we also assume that ‘interaction frequency’ affects the evolvement of relational social capital. Frequent interaction provides an appropriate condition for generating a mutual feeling of emotional attachment. ‘Interaction frequency’ can also increase the likelihood that individuals extend relationships beyond ‘business’ (‘intimacy’). Frequent interaction can bridge motivational barriers, too (Bartsch et al. Reference Bartsch, Ebers and Maurer2013). Hence, we suggest that the interrelation between ‘interaction frequency’ and relational capital, in total, affects collaborative disaster relief performance positively because it boosts the feeling of familiarity, mutual confiding, and also obligation, which increase the collaborating individuals’ motivation to help and to share knowledge with each other.

- H 5a (+ )

-

The interaction between interaction frequency and emotional intensity affects the collaborative disaster relief performance positively.

- H 5b (+ )

-

The interaction between interaction frequency and intimacy affects the collaborative disaster relief performance positively.

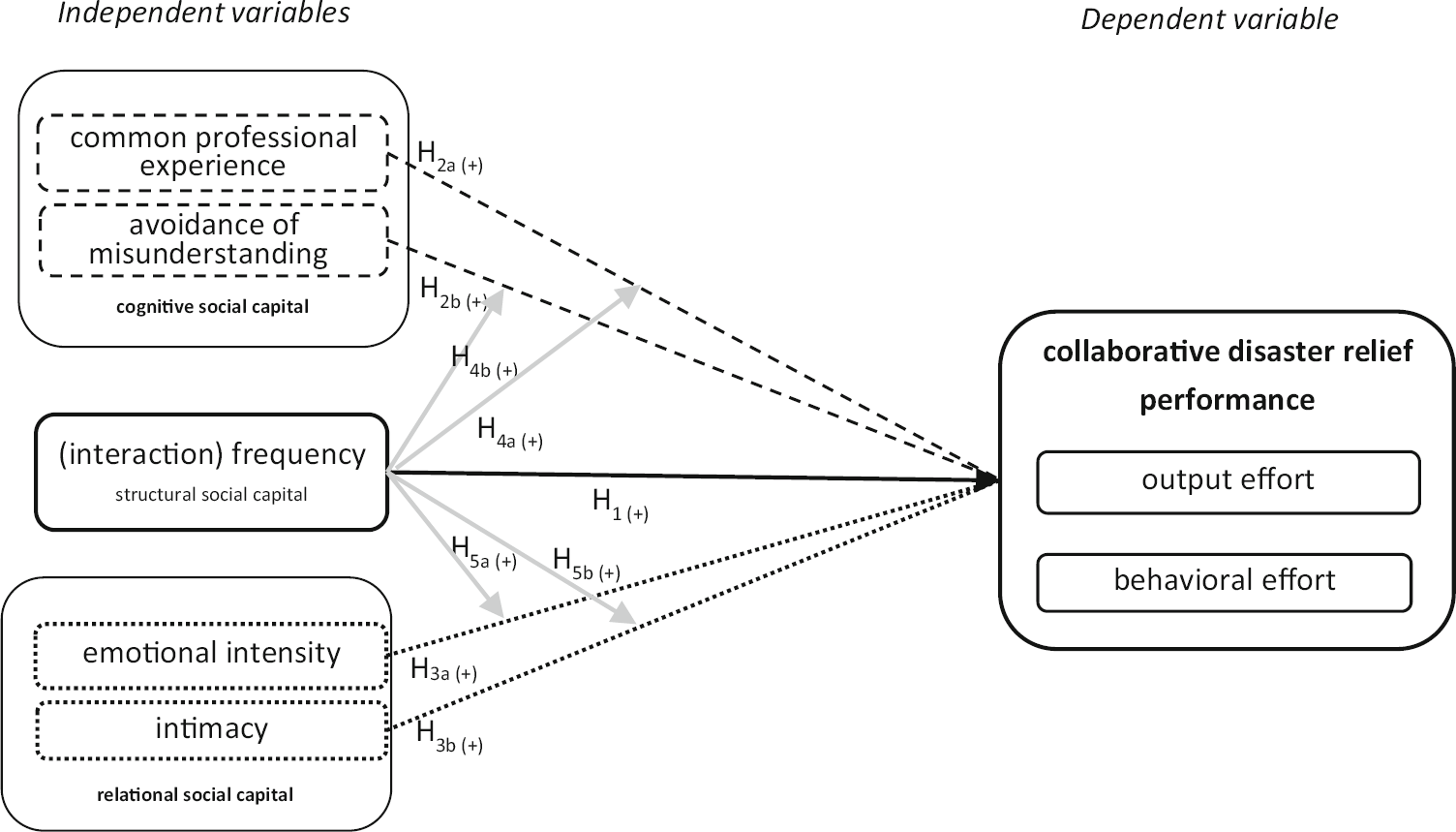

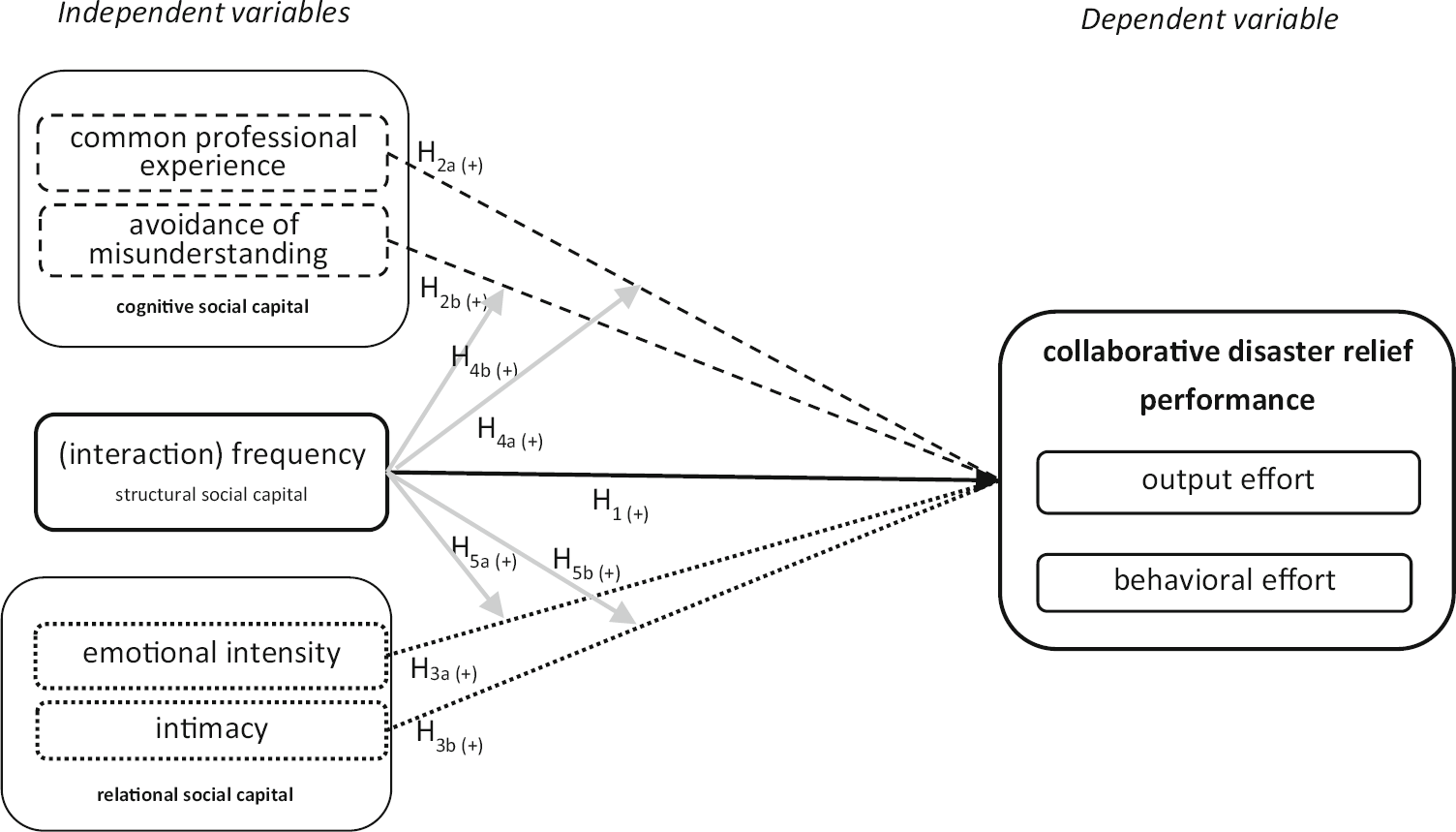

Figure 1 illustrates our research model and the corresponding hypotheses.

Fig. 1 Research model and hypotheses

Research Design

Data Collection

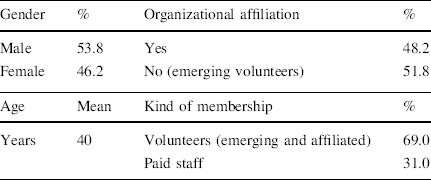

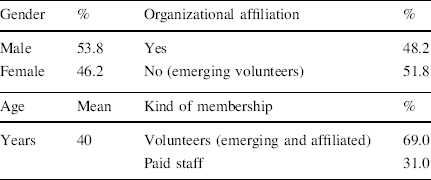

We developed a questionnaire in close cooperation with a variety of experts to analyze the effects of social capital on collaborative disaster relief performance in the Austrian refugee migration of 2015/2016. At first, we conducted interviews with two NPO managers and two scientists in the fields of strategic management and human resource management about the questionnaire and the most appropriate group of respondents. Secondly, four NPO practitioners ran a pretest resulting in small adaptations of the questionnaire. These were individuals without management positions, engaging in teams consisting of NPO members and volunteers. In contrast to managers, these practitioners were continuously operatively active and could assess how ‘learn-by-doing’ action occurred. During the peak of the refugee migration, a particularly dynamic situation, it was extremely challenging to get individuals to answer the questionnaire. In total, 345 respondents started the survey of which 90 held management functions and were, therefore, not included in the analysis. Our final sample consists of 249 operative individuals. Due to the exceptional environmental circumstances, 122 fully completed and usable questionnaires were returned. Table 1 describes the sample.

Table 1 Respondent characteristics

Gender |

% |

Organizational affiliation |

% |

|---|---|---|---|

Male |

53.8 |

Yes |

48.2 |

Female |

46.2 |

No (emerging volunteers) |

51.8 |

Age |

Mean |

Kind of membership |

% |

|---|---|---|---|

Years |

40 |

Volunteers (emerging and affiliated) |

69.0 |

Paid staff |

31.0 |

N = 249

Sample

In general, there were a more or less equal number of men (53.8%) and women (46.2%) engaging operatively in refugee migration. On average, they were about 40 years old. About half of the respondents (51.80%) did not have any affiliation with a NPO before and thus represented emerging volunteers. The other 48.2% were members of two well-established Austrian national associations active in civil aid and rescue services and engaged either as affiliated volunteers or as paid staff. National association A has about 8200 paid employees plus 73,000 affiliated volunteers and 4300 civil servants. National association B has 14,000 paid and 40,000 affiliated volunteers. In sum, about two-third (69.0%) of the respondents were volunteers (affiliated and emerging ones) and one-third (31.0%) represented paid staff.

Measures

Dependent Variable

Following Hoegl and Gemuenden (Reference Hoegl and Gemuenden2001, 438) and Hoch (Reference Hoch2007, 95), collaborative disaster relief performance was indexed by four items, wherein two items refer to output effort (performance results) and two items refer to behavioral effort (performance endeavor) (see also Hoch and Kozlowski Reference Hoch and Kozlowski2014). The survey participants were asked to assess these items ranging from 0 to 100%.

Independent Variables

We mostly draw on the scales of Bartsch et al. (Reference Bartsch, Ebers and Maurer2013) and Bartsch (Reference Bartsch2010) to measure social capital as independent variables. We chose these scales because they have been previously used in a similar setting. Bartsch et al. (Reference Bartsch, Ebers and Maurer2013) explored the effects of social capital on performance of temporary organizations similar to the emerging collaboration in the disaster context. Moreover, they also follow a learning perspective.

Social capital. As previously mentioned, we refer to an interpersonal perspective of social capital and thus differentiate between cognitive social capital, relational social capital, and structural social capital. In total, social capital was assessed by five items on a 5-point Likert scale asking the survey participants for their level of agreement (1 = totally agree, 5 = totally disagree). In line with Bartsch et al. (Reference Bartsch, Ebers and Maurer2013) and some adaptations, these are ‘common professional experience’ (adapted from Lui and Ngo Reference Lui and Ngo2005, 1150) and ‘avoidance of misunderstanding’ (adapted from Abrams et al. Reference Abrams, Cross, Lesser and Levin2003, 67) for illustrating cognitive social capital. Relational social capital was considered as the kind of personal relationships individuals have due to their interactions (Granovetter Reference Granovetter, Nohria and Eccles1992) and assessed by two items. These are ‘emotional intensity’ (adapted from Hansen et al. Reference Hansen, Mors and Lovas2005, 708) and ‘intimacy or multiplicity’ (adapted from Reagans and McEvily Reference Reagans and McEvily2003, 250) (Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010). Finally, structural social capital was measured by ‘interaction frequency’ (adapted from Reagans and McEvily Reference Reagans and McEvily2003, 250).

Control Variables

Finally, we integrated five control variables in our model. Based on one item each, we controlled for ‘task complexity’ (Gaitanides and Stock Reference Gaitanides and Stock2004), ‘environmental dynamics’ (Jansen et al. Reference Jansen, Van den Bosch and Volberda2006), and ‘task dynamics’ (Li and Liu Reference Li and Liu2014) illustrating the perceptions of the respondents. Control variables were complimented by gender and age.

Validity and Reliability

Due to the explorative character of the effects of social capital on performance and hence the need for detailed understanding, we chose not to construct scales but to analyze the effects of social capital components on a single-item base. Due to the fact that disaster relief performance as dependent variable does not represent a reflexive but a formative scale, there is no formal reliability or validity check possible (Rossiter Reference Rossiter2002, 311).

Findings

We employed a hierarchical regression analysis to test the hypothesized effects. Hierarchical regression analysis is particularly appropriate, when the prediction of incremental contributions of independent variables to the criterion is in the focus of interest (Bühner and Ziegler Reference Bühner and Ziegler2009). In a first step, the dependent variable was regressed on the independent variables. Secondly, we added the interaction terms in the model. Due to the fact that the interaction frequency can be considered as foundation for social capital building (Coleman Reference Coleman1990), we analyzed the interaction terms between ‘interaction frequency’ and cognitive as well as relational social capital components.

As a check for correspondence of model assumptions, we use scatterplots, VIF, and a Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normal distribution and did not find hints pointing to autocorrelation, multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, or non-normal distribution.

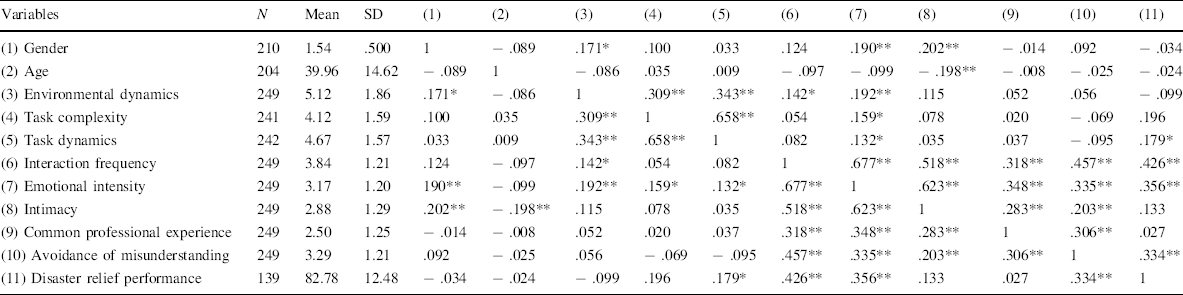

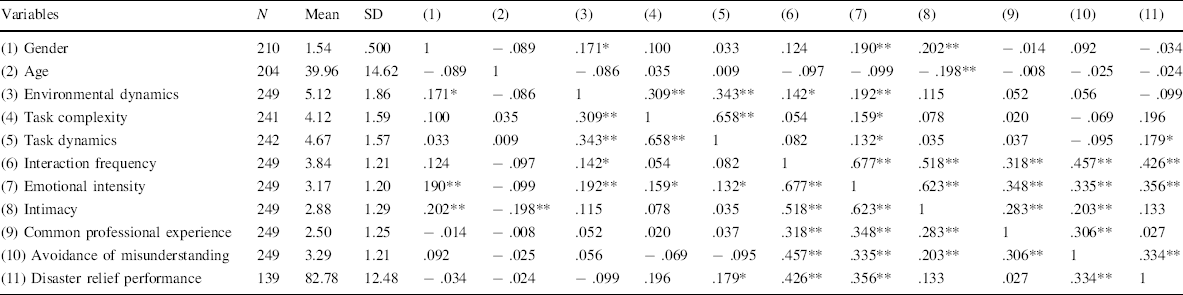

Table 2 contains means, standard deviations, and correlations. It shows that collaborative disaster relief performance significantly correlates with ‘interaction frequency’ (structural social capital), ‘emotional intensity’ (relational social capital), and ‘avoidance of misunderstanding’ (cognitive social capital). These relationships are medium strong. The relationships to ‘intimacy’ (relational social capital) as well as to ‘common professional experience’ (cognitive social capital) are not significant, though. In reference to control variables, there is a weak significant relationship between disaster relief performance and task dynamics. Age, gender, task complexity, and environmental dynamics do not show any effects. ‘Interaction frequency’ relates (very) strongly and significantly with ‘emotional intensity’ and ‘intimacy’. The relationships between ‘interaction frequency’ and ‘common professional experience’ as well as with ‘avoidance of misunderstanding’ are significant and medium strong. In general, ‘emotional intensity’ and ‘intimacy’ are significantly correlated with cognitive social capital components. Significant relations between independent variables are not relevant for testing moderating hypotheses (Baron and Kenny Reference Baron and Kenny1986).

Table 2 Descriptives and correlations

Variables |

N |

Mean |

SD |

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

(4) |

(5) |

(6) |

(7) |

(8) |

(9) |

(10) |

(11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(1) Gender |

210 |

1.54 |

.500 |

1 |

− .089 |

.171* |

.100 |

.033 |

.124 |

.190** |

.202** |

− .014 |

.092 |

− .034 |

(2) Age |

204 |

39.96 |

14.62 |

− .089 |

1 |

− .086 |

.035 |

.009 |

− .097 |

− .099 |

− .198** |

− .008 |

− .025 |

− .024 |

(3) Environmental dynamics |

249 |

5.12 |

1.86 |

.171* |

− .086 |

1 |

.309** |

.343** |

.142* |

.192** |

.115 |

.052 |

.056 |

− .099 |

(4) Task complexity |

241 |

4.12 |

1.59 |

.100 |

.035 |

.309** |

1 |

.658** |

.054 |

.159* |

.078 |

.020 |

− .069 |

.196 |

(5) Task dynamics |

242 |

4.67 |

1.57 |

.033 |

.009 |

.343** |

.658** |

1 |

.082 |

.132* |

.035 |

.037 |

− .095 |

.179* |

(6) Interaction frequency |

249 |

3.84 |

1.21 |

.124 |

− .097 |

.142* |

.054 |

.082 |

1 |

.677** |

.518** |

.318** |

.457** |

.426** |

(7) Emotional intensity |

249 |

3.17 |

1.20 |

190** |

− .099 |

.192** |

.159* |

.132* |

.677** |

1 |

.623** |

.348** |

.335** |

.356** |

(8) Intimacy |

249 |

2.88 |

1.29 |

.202** |

− .198** |

.115 |

.078 |

.035 |

.518** |

.623** |

1 |

.283** |

.203** |

.133 |

(9) Common professional experience |

249 |

2.50 |

1.25 |

− .014 |

− .008 |

.052 |

.020 |

.037 |

.318** |

.348** |

.283** |

1 |

.306** |

.027 |

(10) Avoidance of misunderstanding |

249 |

3.29 |

1.21 |

.092 |

− .025 |

.056 |

− .069 |

− .095 |

.457** |

.335** |

.203** |

.306** |

1 |

.334** |

(11) Disaster relief performance |

139 |

82.78 |

12.48 |

− .034 |

− .024 |

− .099 |

.196 |

.179* |

.426** |

.356** |

.133 |

.027 |

.334** |

1 |

*p < .05; **p < .01; p*** < .001

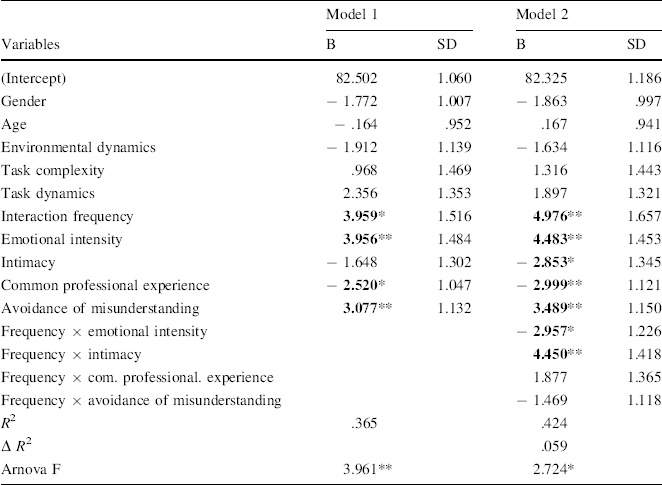

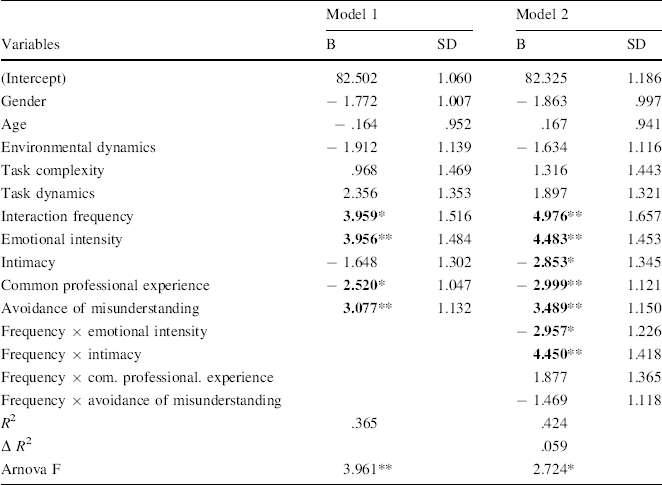

Table 3 summarizes the results for the hypothesized effects of all independent variables as well as of the interaction effects on collaborative disaster relief performance. Model 1 indicates that ‘interaction frequency’ significantly correlates with collaborative disaster relief performance (b = 3.959; SE = 1.516; p < .05) and thus supports (H 1). Furthermore, the results indicate that ‘common professional experience’ (b = − 2.520; SE = 1.047; p < .05) and ‘avoidance of misunderstanding’ (b = 3.077; SE = 1.132; p < .01) have a significant influence on collaborative disaster relief performance. Whereas the effect of ‘avoidance of misunderstanding’ is positive, the relationship between ‘common professional experience’ and performance is negative. Thus, we found a support for Hypothesis 2b but not for Hypothesis 2a; it posited a positive relationship between ‘common professional experience’ and collaborative disaster relief performance. Furthermore, Model 1 illustrates the effects of relational social capital in terms of ‘emotional intensity’ and ‘intimacy’ of relationships. ‘Emotional intensity’ is significantly and positively associated with performance (b = 3.956; SE = 1.484; p < .01), which is in line with Hypothesis 3a. Finally, we see a negative and nonsignificant association between ‘intimacy’ and performance (b = − 1.648; SE = 1.302; p < n.s.). Hence, Hypothesis 3b is rejected.

Table 3 Results of regression analysis: social capital and collaborative disaster relief performance (significant values in bold)

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Variables |

B |

SD |

B |

SD |

(Intercept) |

82.502 |

1.060 |

82.325 |

1.186 |

Gender |

− 1.772 |

1.007 |

− 1.863 |

.997 |

Age |

− .164 |

.952 |

.167 |

.941 |

Environmental dynamics |

− 1.912 |

1.139 |

− 1.634 |

1.116 |

Task complexity |

.968 |

1.469 |

1.316 |

1.443 |

Task dynamics |

2.356 |

1.353 |

1.897 |

1.321 |

Interaction frequency |

3.959* |

1.516 |

4.976** |

1.657 |

Emotional intensity |

3.956** |

1.484 |

4.483** |

1.453 |

Intimacy |

− 1.648 |

1.302 |

− 2.853* |

1.345 |

Common professional experience |

− 2.520* |

1.047 |

− 2.999** |

1.121 |

Avoidance of misunderstanding |

3.077** |

1.132 |

3.489** |

1.150 |

Frequency × emotional intensity |

− 2.957* |

1.226 |

||

Frequency × intimacy |

4.450** |

1.418 |

||

Frequency × com. professional. experience |

1.877 |

1.365 |

||

Frequency × avoidance of misunderstanding |

− 1.469 |

1.118 |

||

R 2 |

.365 |

.424 |

||

Δ R 2 |

.059 |

|||

Arnova F |

3.961** |

2.724* |

||

Unstandardized regression coefficients with standard errors in parentheses are reported

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001. N = 122

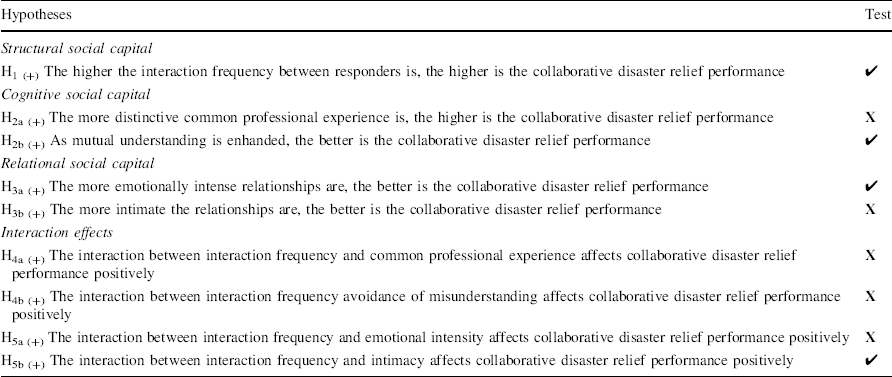

In a following step, we analyzed the interaction effects between ‘interaction frequency’ as ‘foundation’ for social capital building and cognitive as well as relational social capital. This is illustrated in Model 2. We found a negative and significant relationship between ‘interaction frequency’ and ‘emotional intensity’ on performance (b = − 2.957; SE = 1.226; p < .05). Although this finding provides evidence for a significant effect—emotional intensity affects disaster performance depending on the interaction frequency—Hypothesis 5a has to be rejected because we assumed a positive effect. The table also shows a positive and significant effect of ‘intimacy’ combined with ‘interaction frequency’ (b = 4.450; SE = 1.418; p < .01). Hence, the effect of intimacy on collaborative disaster relief performance differs depending on ‘interaction frequency’, which in turn supports Hypothesis 5b. In combination with ‘frequent interaction’, ‘intimacy’ has a positive and significant impact on disaster relief performance. Finally, we had a look on the interaction effects between ‘interaction frequency’ and cognitive social capital components. Both effects were not significant; thus, Hypotheses 4a and 4b have to be rejected.

Discussion and Conclusion

There is an increasing consensus in research that relief in large-scale disasters requires collaboration between formally designated relief organizations, such as NPOs and emerging volunteers (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd and Zhao2017; Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015; Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007; Roth Reference Roth2017; Gratz Reference Gratz2016). Thus, emerging volunteering gains in importance in disaster relief (Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, McLennan and Handmer2015; Strandh and Eklund Reference Strandh and Eklund2017; McLennan et al. Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016). The form of collaboration that evolves between NPOs as formal disaster relief organizations and these emerging volunteers during disaster can be regarded as an emergent collaboration. Emergent collaborations follow a ‘[…] action-based model of coordinated problem solving’ (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007). That means collaborative agents gain an enhanced understanding both of their tasks and the responders, as a collective, through their performance. In other words, (structured) self-organization results from connections, actions, and reactions of the collaborative agents (Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014). Thus, emergent collaboration enables NPOs and volunteers to solve their ‘structural problems and planning problems’; it particularly supports NPOs as well as volunteers to create balance of flexibility and structure (Meyer and Simsa Reference Meyer and Simsa2018, 1167 ff.). Hence, it temporarily bridges the formal structures and the notion of how to proceed after the disaster and thus provides sustainable disaster relief in terms of reshaping and restoring—prevailing primarily—the physical and social environment (Smith and Wenger Reference Smith, Wenger, Rodriguez, Quarantelli and Dynes2007, 246).

Following McLennan et al. (Reference McLennan, Whittaker and Handmer2016) and other scholars, for example, Moshtari and Gonçalves (Reference Moshtari and Gonçalves2017), research on (emergent) collaboration in a disaster context in particular, lacks clearly identified (behavioral) factors that facilitate collaboration. Because emergent collaboration between NPOs and volunteers is supposed to have, as already mentioned, a ‘learn-by-doing action-based model of problem solving’ (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007, 150), we draw on social capital as access, mobilization, and learning enhancing resource endowment. We aim at examining the link between these components and collaborative disaster relief performance as an emerging effort between NPOs and volunteers on team level.

Our findings highlight the importance of social capital in providing collaborative disaster relief performance. With regard to structural social capital, we found evidence for the influence of ‘interaction frequency’ on collaborative disaster relief performance. This evidence corresponds with previous findings demonstrating that the more team members interact, the better they know each other and this in turn reduces barriers to knowledge sharing. Furthermore, the chance of getting feedback is higher (Maurer et al. Reference Maurer, Bartsch and Ebers2011; Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010).

We also explored the effects of cognitive social capital on collaborative disaster relief performance and thus enhance an understanding of the influence of social capital. The effect of ‘avoidance of misunderstanding’, which symbolizes cognitive similarity, influenced performance significantly. Disaster context is usually characterized by a high degree of improvisation. This fact usually correlates with a high rate of change. Participants, therefore, draw on colleagues to compensate for failures resulting from misunderstandings, which in turn may reduce the negative effect of misunderstandings on performance. We also found support for a performance effect of ‘common professional experience’. Common professional experience affects collaborative disaster relief performance negatively, not positively as proposed. One reason for that may be that routines and previous experience acquired in non-disaster contexts hindered flexibility and adaptability necessary to cope with disasters (Gardner Reference Gardner2013). As Model 2 shows, interactions between cognitive social capital and structural social capital, i.e., ‘interaction frequency’, do not show any significant effects. This may be rooted in the fluid team memberships (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007) leveling these interaction effects.

We also examined the effects of the third component of social capital, relational social capital. Regression analysis proved that ‘emotional intensity’ correlates positively with collaborative disaster relief performance. This is in line with previous research, for example, Bartsch (Reference Bartsch2010), who states that if individuals enjoy emotional closeness with their team members, they will be more willing to support them. Considering the interaction effects, we see a negative effect between ‘emotional intensity’ and ‘interaction frequency’. This means that ‘emotional intensity’ reduces performance when there is much interaction in teams. This might be effects of social loafing (Karau and Williams Reference Karau and Williams1993), a reduction in motivation and effort when people are working collectively—interacting frequently in our case. George (Reference George1992) also shows how intrinsic involvement affects social loafing. So these aspects might be able to explain the negative relationship between ‘emotional intensity’ and ‘interaction frequency’ on performance. If ‘intimacy’ in terms of multiplicity of relationships is enriched by ‘interaction frequency’, it shows a positive significant effect on performance. Thus, frequent interaction provides the individual with the appropriate conditions to enfold his/her distinctive position in the other’s life. The development of intimacy represents a dynamic process of self-disclosing, partner disclosing, and interpreting the response as validating and understanding, which requires a certain interaction frequency (Laurenceau et al. Reference Laurenceau, Barrett and Pietromonaco1998). The individual can use both, the work level as well as the private (relational) level to influence the team members and thus to improve knowledge sharing and finally performance (Bartsch Reference Bartsch2010, 93). Intimacy is also considered to be related with open communication, which in turn enhances knowledge sharing information even on unpleasant issue, e.g., negative experience in disaster relief (Brown and Konrad Reference Brown and Konrad2001).

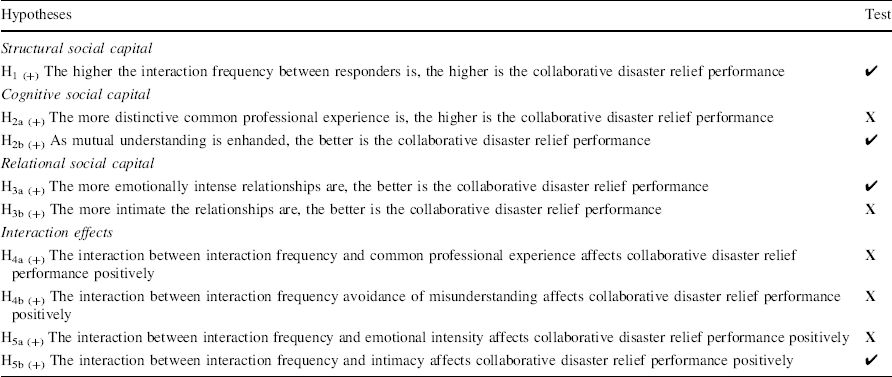

Table 4 provides an overview regarding the tested hypotheses we have discussed above.

Table 4 Overview over hypotheses support

Hypotheses |

Test |

|---|---|

Structural social capital |

|

H1 (+) The higher the interaction frequency between responders is, the higher is the collaborative disaster relief performance |

✓ |

Cognitive social capital |

|

H2a (+) The more distinctive common professional experience is, the higher is the collaborative disaster relief performance |

X |

H2b (+) As mutual understanding is enhanded, the better is the collaborative disaster relief performance |

✓ |

Relational social capital |

|

H3a (+) The more emotionally intense relationships are, the better is the collaborative disaster relief performance |

✓ |

H3b (+) The more intimate the relationships are, the better is the collaborative disaster relief performance |

X |

Interaction effects |

|

H4a (+) The interaction between interaction frequency and common professional experience affects collaborative disaster relief performance positively |

X |

H4b (+) The interaction between interaction frequency avoidance of misunderstanding affects collaborative disaster relief performance positively |

X |

H5a (+) The interaction between interaction frequency and emotional intensity affects collaborative disaster relief performance positively |

X |

H5b (+) The interaction between interaction frequency and intimacy affects collaborative disaster relief performance positively |

✓ |

✓, hypothesis supported; X, hypothesis rejected

The study contributes to extant research in various ways. Firstly, we contribute to the existing disaster research with focus on volunteering by showing that emergent collaboration between NPOs and emerging volunteers based on social capital represents an appropriate approach to enhance performance and thus to jointly respond to social disasters. Due to the fact that emergent collaborative efforts go along with the creation of a shared understanding of goals, tasks, structure, and the responders as collective, they also contribute to sustainability in disaster relief. By choosing refugee migration as research context, we particularly enrich research in the context of social disasters, which are less studied than natural disasters.

Secondly, by illustrating which social capital components affect emergent collaborative efforts of NPOs and volunteers on a team level, the study refines social capital components ‘suitable’ for disaster relief and thus enhances the small body of research discussing behavioral enablers of collaborations in a disaster context. This refinement not only includes the specification of the single social capital components, but also the interdependences between the components. In summary, collaborative efforts can be regarded as distinctively highly socially driven.

Our findings result in the following implications for practice: NPOs should actively approach as well as supply volunteer(s) (groups) in case of a large-scale disaster (Williams and Shepherd Reference Williams and Shepherd2016, 2096) and integrate them into their disaster relief efforts. This aspect requires that NPOs modify their training procedures. In addition to standardized training procedures, NPOs should implement trainings that focus on learning (a) how to quickly recognize emergent volunteers’ capacity (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007) and (b) when to ‘use’ volunteers and for which purposes/tasks. In order to ‘use’ the potential of emergent collaboration, organizational change is needed. This aspect particularly refers to reconsidering NPOs’ command-and-control structures in fields not representing core activities (such as ambulances), which have to be automatically relaxed in case of disaster. In order to improve connectedness with volunteers, additional liaison officers could be installed. Moreover, emergent collaboration could be integrated into disaster exercises.

Theoretically, our analysis indicates that social capital constantly develops through action (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007; Beck and Plowman Reference Beck and Plowman2014). In addition to trust and identity aspects affecting emergent collaboration identified by Beck and Plowman (Reference Beck and Plowman2014), we show that emergent collaborative efforts (performance) are invigorated through social capital. Secondly, our study also enriches strategic management research dealing with environmental dynamics and the level discussion. It shows that both the individual and the team level are sources of stability and flexibility at the same time (Majchrzak et al. Reference Majchrzak, Jarvenpaa and Hollingshead2007) and thus it contributes to the debate of (microfoundations of) dynamic capabilities and ambidexterity in strategic management (Raisch and Birkinshaw Reference Raisch and Birkinshaw2008; Helfat and Peteraf Reference Helfat and Peteraf2015; Mahringer and Renzl Reference Mahringer and Renzl2018).

Our findings must be viewed in the light of some limitations, though. First and foremost, our study draws on a relatively small sample size which restricts the generalizability of our results. Secondly, although we deliberately draw on collaborative efforts perceived by agents on a team level because they can assess their performance better than managers who are only partly present due to the demanding and dynamic situation, the dependent variable is nevertheless perception-based (disaster relief performance represents a self-rated variable). Thirdly, we draw on a very simplified research model; interactions are likely to be more complex than illustrated and might be enhanced in more elaborated models by future research. Fourth, we focused our analysis on the phase where emergent collaboration evolved, also called second-order learning phase (Meyer and Simsa Reference Meyer and Simsa2018, 1164). Further research might extend the analysis to the other phases during the occurrence of disasters and provide a more comprehensive view on disaster relief.

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Paris Lodron University of Salzburg.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.