Introduction

Exposure to traumatic or highly stressful events may lead to considerable psychological distress, which in some cases develops into post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). PTSD symptomatology includes intrusive memories, avoidance of trauma-related stimuli, negative changes in mood and cognition, and heightened arousal and reactivity. These symptoms cause significant distress or impairment in functioning that do not result from another medical condition or substance use (APA, 2013). PTSD can be found not only in adults but also in children. The specific diagnosis criteria in the DSM-5 varies with age. Two recent meta-analyses showed that 5% of children who are less than 6.5 years of age and who were exposed to traumatic events meet the adult criteria for PTSD, while 24% of them meet age-appropriate criteria (Woolgar et al., Reference Woolgar, Garfield, Dalgleish and Meiser-Stedman2022), which is similar to the prevalence within adults (Schincariol et al., Reference Schincariol, Orrù, Otgaar, Sartori and Scarpazza2024). Moreover, Woolgar et al., have indicated that the prevalence was higher when the context of the traumatic event was interpersonal and repeating.

On October 7, 2023, Isreal experienced an extreme terror attack, including the destruction and evacuations of whole communities. This was followed by many months of continuous war and daily missile attacks on those communities that were not evacuated. Those who experienced it the most and first hand were citizens living on Israel southern border, who became at-risk for developing PTSD (APA, 2013). Developmental theories have long emphasized the mutual influences between mothers and their children, particularly in early stages of life, when children are highly dependent on external sources of regulation (e.g., Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). The literature suggests that more developed mechanisms of self-regulation might be protective against the development of psychopathology and PTSD symptoms (Koenen, Reference Koenen2006; Zweerings et al., Reference Zweerings, Pflieger, Mathiak, Zvyagintsev, Kacela, Flatten and Mathiak2018; and more). However, there are no longitudinal or prospective studies that have evaluated such dyadic relations and mutual effects. In this study we examined the mutual moderating effects of mothers and their children’s PTSD symptoms on the predictive value of their self-regulation – as indicated by post-error slowing (PES) – for their PTSD symptoms when they coped with a real-life highly stressful situation.

Self-regulation refers to the ability to flexibly manage cognition, actions, and emotions, encompassing both conscious and unconscious efforts to control one’s internal state (Berger, Reference Berger2011; Nigg, Reference Nigg2017; Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart2000; Vohs & Baumeister, Reference Vohs and Baumeister2016). The development of self-regulation is most prominent during early childhood, as neuro-cognitive and neuro-emotional systems of executive attention and inhibitory control undergo rapid growth (Berger, Reference Berger2011; Denervaud et al., Reference Denervaud, Knebel, Immordino-Yang and Hagmann2020; Pozuelos et al., Reference Pozuelos, Paz-Alonso, Castillo, Fuentes and Rueda2014; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Moyano and Rico-Picó2023). This is a complex and multilayered process influenced not only by genetics and maturation, but also through constant interactions with the environment (Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Burt, Edwards and Deater-Deckard2015; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). Positive and negative developmental cascades significantly shape this trajectory (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; Bridgett et al., Reference Bridgett, Burt, Edwards and Deater-Deckard2015; Nigg, Reference Nigg2017; Posner & Rothbart, Reference Posner and Rothbart2000; Rothbart, Reference Rothbart2011).

One well-known behavioral indicator of executive attention and self-regulation is PES, which is the tendency to slow down the next response after committing an error. PES is defined as the increasing of reaction time (RT) after an error, compared to the RT after a correct response (Laming, Reference Laming1979; Rabbitt & Rodgers, Reference Rabbitt and Rodgers1977). It is a well-known behavioral marker of adjustments on a trial-by-trial basis (Botvinick et al., Reference Botvinick, Braver, Barch, Carter and Cohen2001; Lavro et al., Reference Lavro, Levin, Klein and Berger2018; Li et al., Reference Li, Hu, Li, Long, Gu, Tang and Chen2021) and seems to reflect processing of the error in the fronto-parietal system (Dosenbach et al., Reference Dosenbach, Fair, Miezin, Cohen, Wenger, Dosenbach, Fox, Snyder, Vincent, Raichle, Schlaggar and Petersen2007, Reference Dosenbach, Fair, Cohen, Schlaggar and Petersen2008; Petersen & Posner, Reference Petersen and Posner2012; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Pozuelos and Cómbita2015; Sestieri et al., Reference Sestieri, Corbetta, Spadone, Romani and Shulman2014).

Although initial brain activity related to error detection has already been found in infants (see review in Berger & Posner, Reference Berger and Posner2023), the earliest behavioral manifestation of slowing after an error has been found in toddlers at the age of around 3 years old (Ger & Roebers, Reference Ger and Roebers2023; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rothbart and Posner2003; Yeshua & Berger, Reference Yeshua and Berger2024), with PES continuing to grow until the age of 6 to 9 years, and then decreasing (de Mooij et al., Reference de Mooij, Dumontheil, Kirkham, Raijmakers and van der Maas2022; Gupta et al., Reference Gupta, Kar and Srinivasan2009). This enlargement of the PES effect is considered to be one of the indices of the development and maturation of the executive attention network and cognitive control functions (Cravet & Ger, Reference Cravet and Ger2026; de Mooij et al., Reference de Mooij, Dumontheil, Kirkham, Raijmakers and van der Maas2022; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Moyano and Rico-Picó2023), abilities for which the most intensive and critical age period for development is preschool and kindergarten (Davidson et al., Reference Davidson, Amso, Anderson and Diamond2006; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rothbart and Posner2003; Pozuelos et al., Reference Pozuelos, Paz-Alonso, Castillo, Fuentes and Rueda2014; Rico-Picó et al., Reference Rico-Picó, Hoyo, Guerra, Conejero and Rueda2021; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Moyano and Rico-Picó2023; Zelazo et al., Reference Zelazo, Anderson, Richler, Wallner-Allen, Beaumont and Weintraub2013; Zelazo & Carlson, Reference Zelazo and Carlson2012). Even though PES can already be observed at an early age, consistently there are substantial individual differences among children of the same age (Cravet & Ger, Reference Cravet and Ger2026; Yeshua & Berger, Reference Yeshua and Berger2024). Compared to adults, these differences are more pronounced in early childhood, and the overall effect size in adulthood is nearly half of that observed in kindergarten-aged children (Yeshua & Berger, Reference Yeshua and Berger2024).

Although no study has explored the relation between PES and PTSD, extensive research has investigated the relation between self-regulation and PTSD (Jagger-Rickels et al., Reference Jagger-Rickels, Stumps, Rothlein, Park, Fortenbaugh, Zuberer, Fonda, Fortier, DeGutis, Milberg, McGlinchey and Esterman2022; Koenen, Reference Koenen2006; Swick & Ashley, Reference Swick and Ashley2020; Swick et al., Reference Swick, Lwi, Larsen and Ashley2024; Van der Kolk, Reference Van der Kolk and Panksepp2003; Zweerings et al., Reference Zweerings, Pflieger, Mathiak, Zvyagintsev, Kacela, Flatten and Mathiak2018; and more), although this literature is mostly on adults, cross-sectional, and correlational, limiting the ability to assess the potential predictive value of self-regulation and its plausible role as a risk/protective factor against PTSD. Adults diagnosed with PTSD show lower levels of inhibitory control, compared to a matched control group (Falconer et al., Reference Falconer, Bryant, Felmingham, Kemp, Gordon, Peduto, Olivieri and Williams2008). At the neuro-cognitive level, they show impaired connectivity between neural networks responsible for executive function and the top-down regulation of attention (Jagger-Rickels et al., Reference Jagger-Rickels, Stumps, Rothlein, Park, Fortenbaugh, Zuberer, Fonda, Fortier, DeGutis, Milberg, McGlinchey and Esterman2022). In their review of 14 cognitive psychology articles and 17 neuroimaging studies on maltreatment-related PTSD in children, Carrion et al. (Reference Carrion, Wong and Kletter2013) presented aggregated evidence indicating that these children exhibit poorer performance on measures of attention and executive functions. Additionally, the review highlighted reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), particularly in the anterior cingulate cortex and medial PFC, which are brain structures associated with attention control and post-error adaptation (Chidharom et al., Reference Chidharom, Krieg, Pham and Bonnefond2021). As mentioned above, to the best of our knowledge, so far no study has examined the predictive role of self-regulation indicators (such as PES), either at an early age or adulthood, for the development of PTSD symptomatology in children and adults when they face stressful situations later on in their lives.

Although the literature is lacking on empirical data regarding longitudinal predictions of self-regulation for PTSD symptoms, there are theoretical frameworks, as well as empirical works on the dyadic effects, that can establish the working hypotheses. The current study is grounded in the transactional theoretical frameworks that emphasize the dynamic interplay between individual vulnerabilities and environmental influences (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). These theories emphasize that developmental outcomes are shaped through continuous, bidirectional exchanges between the child and their caregiving environment, particularly within the parent–child dyad. These mutual interactions accumulate over time and are especially critical during early childhood (Cuevas et al., Reference Cuevas, Deater-Deckard, Kim-Spoon, Watson, Morasch and Bell2014; Tiberio et al., Reference Tiberio, Capaldi, Kerr, Bertrand, Pears and Owen2016), when children rely heavily on external sources of regulation. Each member’s psychological state continually shapes – and is shaped by – that of the other. Together, these models suggest that more developed self-regulatory capacity can promote less risk for developing PTSD symptoms. However, the mother’s and child’s psychological states can mutually influence each other over time, such that elevated PTSD symptoms in one member of the dyad may act as a stressor that exacerbates the other’s vulnerability, therefore modulating the risk of developing PTSD symptoms in the face of extreme stress exposure.

In line with these frameworks, we hypothesized that: (1) Maternal and child PTSD symptoms will be positively associated (H1). (2) More developed PES at T1 will predict lower PTSD symptoms at T2 in both children (H2a) and their mothers (H2b). Operationally, larger PES in children (indicating more developed self-regulation) will predict fewer PTSD symptoms, while larger PES in mothers (indicating poorer self-regulation in adults) will predict more PTSD symptoms. (3) The degree of PTSD symptoms in the mother will moderate the predictive role of the child’s PES for the child’s PTSD symptoms (H3a). Specifically, for children whose mothers exhibited high PTSD symptoms, more developed PES would serve as a protective factor predicting lower PTSD symptoms. Moreover, the degree of PTSD symptoms in the children will moderate the predictive role of the mother’s PES for the mother’s PTSD symptoms (H3b). Specifically, for mothers whose children exhibit high PTSD symptoms, more developed PES would serve as a protective factor predicting lower maternal PTSD symptoms.

Method

Participants

At T1, prior to the terror attack, 175 mother–child dyads participated in the study that included report-based questionnaires and behavioral tasks. At T2, half a year after the day of the terror attack, all 175 mothers were contacted and asked to respond to a survey; we succeeded in collecting data from 104 dyads. Of the 104 dyads, 61 children were boys (59%), aged between 3y (years) to 6y 6m (months) (M = 4y 6m ± 6m) at T1. Mothers were aged between 36y 8m to 48y 6m (M = 36y 7m ± 4y). The mean time difference between the lab visit in Study 1, to the filling of the questionnaires in Study2 was 1.5 years (SD = half year). At T2, the average age of the children was 6y 1m (SD = 9m; 4y 8m – 8y 5m). The age of the child at T2 was not correlated either with their PES or their PTSD symptoms. After multiple imputations and removal of outliers (see details in the Analytical Plan section) and examination of full data cases, a sample of 95 mothers and children was analyzed in the main analyses. No significant differences (p’s > .05) were found between the dyads included in the analyses for this study and those from the original sample that were not, in terms of mothers’ and children’s Raven scores, mothers’ and children’s ages, socioeconomic status (SES), household chaos, or mothers’ and children’s PES.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Research Committee of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (T1 protocol number 2257-1; T2 protocol number 753-2) and by the Helsinki committee (protocol number 0342-15-SOR). The studies were supported by the Israel Scientific Foundation (ISF; Grant number 533/20). Ethical standards were upheld throughout the study. At T1, participants provided oral consent during the introductory call and subsequently signed an online informed consent form. Only the lead researcher knew their identity. Upon arriving at the lab, mothers also completed Helsinki forms for themselves and their children. The children gave oral consent to participate in every part of the study. All participants were assigned a participation code, which was used in all study sections, ensuring anonymity and privacy. Upon completing their participation, participants received an agreed-upon payment from the lead researcher. At T2, mothers signed an online informed consent form. If either the mothers or their children exceeded the clinical thresholds on the questionnaires, they were contacted and encouraged to further evaluate the results with a qualified professional, to determine whether any follow-up was needed.

Procedure

Prior to the traumatic event (T1), participants were recruited through online advertisements on platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, where they provided their contact information. Subsequently, the lead researcher contacted the mothers and provided them with initial information about the study. Those who agreed to participate completed a survey concerning themselves and their child, which was divided into two parts with a minimum of 2 days between them. Afterward, the mothers and their children visited the laboratory for a 2-hr session during which they performed computerized and behavioral tasks, completed the same EEG/ERP tasks, and engaged in filmed mother–child interactions. The EEG/ERP data was not included in the current study. A half year after the traumatic event (T2), mothers were contacted and were asked to take part in a survey regarding themselves and their children who participated in T1.

Measures

At T1, the mothers answered a survey built on the Qualtrics platform that included questionnaires about themselves, as well as about their child. Among the questionnaires, the following were used in this study: demographic questions evaluating SES and the child’s socioemotional difficulties (SDQ; Goodman, Reference Goodman1997). At the lab, both mother and child participated in several behavioral tasks, including the Emotional Day-Night Task, Intelligence estimation, and the Etch-A-Sketch task. At T2, the mothers answered another survey built on the Qualtrics platform that included questionnaires about themselves, as well as about their child. Among the questionnaires, the following were used in this study: the mothers reported on their own PTSD symptoms (PCL-5 [Psychometric analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5]; Wortmann et al., Reference Wortmann, Jordan, Weathers, Resick, Dondanville, Hall-Clark, Foa, Young-McCaughan, Yarvis, Hembree, Mints, Peterson and Litz2016), as well as their children’s PTSD symptoms (CPSS [Child PTSD Symptom Scale]; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Johnson, Feeny and Treadwell2001). They also reported on their news consumption and objective exposure to traumatic events (i.e., having a family members or friends who were killed/murdered, kidnapped, injured, or missing).

T1 independent variable – post-error slowing (Emotional Day-Night Task; EDN)

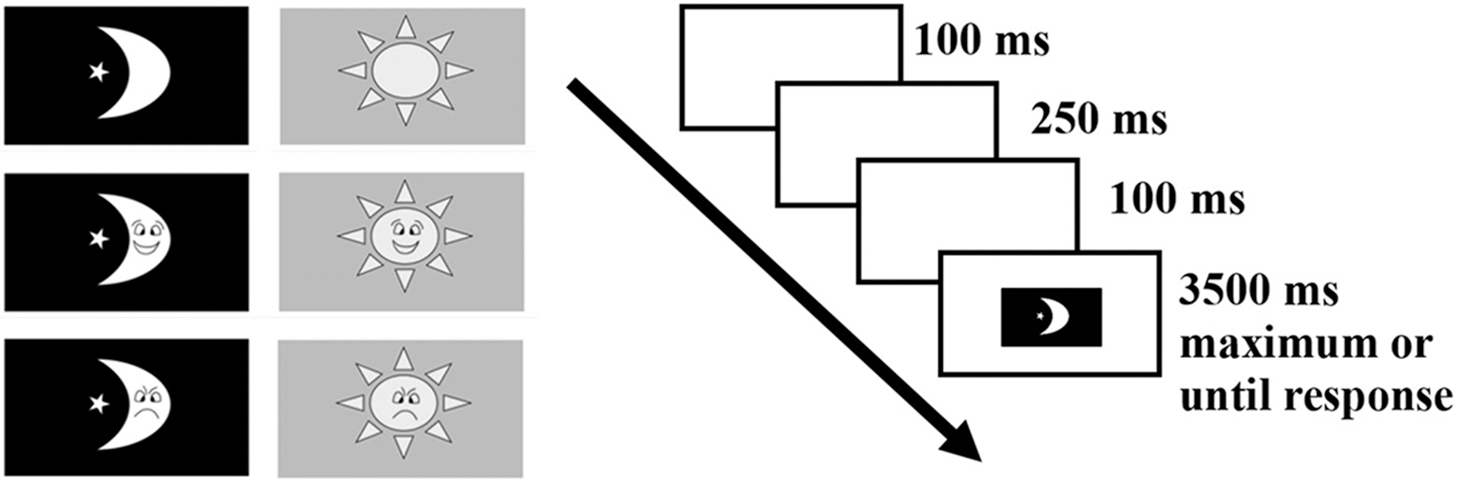

As described in Yeshua and Berger (Reference Yeshua and Berger2024), the EDN task was adapted and programmed using E-Prime 2 (with the tasks accessible at https://github.com/MaorYeshua/EDNT.git). It is based on Go/NoGo and Stroop-like paradigms. Participants were shown six stimuli: three sun images and three moon images, each displaying a happy, angry, or neutral face (with no face superimposed in the neutral condition). Participants responded to each stimulus using a keyboard, pressing the “P” key for “day” or the “W” key for “night.” For children, the task was structured into four blocks, each consisting of 36 trials: 18 “day” trials (six for each emotion: happy, angry, and neutral) and 18 “night” trials (six for each emotion: happy, angry, and neutral). The first three blocks were congruent, requiring children to press the “day” key for a sun image and the “night” key for a moon image. The fourth block was incongruent, with the rules reversed.

At the beginning of each block, children were provided with a “NoGo rule,” indicating that one of the face types (happy, angry, or neutral) was designated as a NoGo stimulus, to which they had to withhold their response. The specific NoGo stimulus was randomly chosen for each block (see Figure 1 for the trial flow and possible stimuli). The adult version of the EDN task closely mirrored the children’s version in terms of the stimuli used and the block rules. However, the adult version comprised 12 blocks of 36 trials each, including six congruent and six incongruent blocks. In the adult task, the “NoGo rule” was more detailed, specifying that one of the six stimuli would serve as the NoGo stimulus.

Figure 1. Single flow trial. Note. Drawn from Yeshua and Berger (Reference Yeshua and Berger2024). Sun stimuli were colored yellow against a blue background. For mothers, maximum appearance time of a stimulus was 2,000 ms.

The PES effect was calculated separately for each mother and each child – always using RTs only from correct Go trials, excluding data from the first block. This resulted in a maximum of 72 Go trials per child and 330 per mother. RTs faster than 150 ms (List et al., Reference List, Rosenberg, Sherman and Esterman2017), which is below the threshold for processing visual perceptual stimuli, were excluded. Additionally, any RT exceeding three standard deviations within each subject was removed. After this preprocessing, the average number of trials per child was 53.60 (SD = 9.83; 29–70), and per mother was 288 (SD = 29; 173–321).

To calculate the participants’ PES effect, each trial was categorized into one of two conditions: (1) post error (PE), if the previous trial was an error, such as an incorrect Go (responding incongruently or failing to respond) or an incorrect NoGo (responding when they shouldn’t); or (2) not post error (NPE). The PES effect was then determined by subtracting the participant’s grand mean of the NPE trials from the participant’s grand mean of the PE trials for each participant (

![]() $\overline{{\rm PE}}-\overline{{\rm NPE}}={\rm PES}$

).

$\overline{{\rm PE}}-\overline{{\rm NPE}}={\rm PES}$

).

T2 dependent variable – mothers’ and children’s PTSD symptoms (PTSD checklist for DSM-5 for adults [PCL-5] and children [CPSS])

This is a reported questionnaire screening for presence and severity of PTSD symptoms, in accordance with the criteria of the DSM-5. Both the adults’ version (PCL-5; Wortmann et al., Reference Wortmann, Jordan, Weathers, Resick, Dondanville, Hall-Clark, Foa, Young-McCaughan, Yarvis, Hembree, Mints, Peterson and Litz2016) and the children’s version (CPSS; Foa et al., Reference Foa, Johnson, Feeny and Treadwell2001) consist of 20 items, which were responded to on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = Not at All, to 4 = Extremely. A sum was computed, with higher values indicating more severe PTSD symptoms. The assessed domains were intrusive symptoms, avoidance symptoms, mood and cognition symptoms, and arousal and reactivity symptoms. Cronbach’s Alpha for the PCL-5 was .90 and for the CPSS was .93.

T1 controlled covariate

Child’s socioemotional difficulties (The strength and difficulties questionnaire; SDQ). The questionnaire was developed by Goodman (Reference Goodman1997). The SDQ consists of 25 items and five factors that are responded to on a 3-point Likert-like scale ranging from 0 = Wrong to 2 = Absolutely right. An average was computed, with higher values indicating higher levels of the reported constructs. A factor of the child’s socioemotional difficulties at T1 was extracted using the Principal Component Analysis method. The factor was loaded by the four difficulty scales: Hyperactivity (.69 loading), Emotional Symptoms (.75 loading), Conduct Problems (.76 loading), and Peer Problems (.72 loading).

Mothers’ parenting practices. They were coded within the Etch-A-Sketch behavioral lab task for the mother and child. This task was a 7-min mother–child interaction (Stevenson-Hinde & Shouldice, Reference Stevenson-Hinde and Shouldice1995) that involved a degree of cooperation, responsiveness and compliance between mothers and children. The Etch-A-Sketch toy has two dials – one for moving the drawing point vertically and the other for moving it horizontally. The researcher assigned each individual a dial to use; both of the participants were instructed not to touch the other’s dial. Each 7-min recording was divided to four segments of 1 min and 45 s. Two coders coded the interaction using an adapted version of the Parent Child Interaction System (PARCHISY; Deater-Deckard et al., Reference Deater-Deckard, Pylas and Petrill1997). Based on a 10-recording sample, the ratings were found to be reliable (Cohen’s Kappa = .74; ICC = .93). Each mother in each coding had four ratings, which were summed-up and divided by four. This was in order to calculate a proportional mean value.

Twelve scales were coded: (1) Positive control (ranged between 1 = No positive control, to 7 = Exclusive use in positive control throughout the task) – the use of praise, explanations and opened questions by the mothers as scaffolders for the child to succeed in the task. (2) Negative control (ranged between 1 = No negative control, to 7 = Exclusive use in negative control throughout the task) – the use of verbal criticism by the mothers or deliberate physical control on the dials/child’s arm or body. (3) Positive affect (ranged between 1 = No positive affect, to 7 = Constant positive affect throughout the task) – the presence of a smile and laughter by the mothers, as well as a generally calm room atmosphere. (4) Negative affect (ranged between 1 = No negative affect, to 7 = Always responds immediately) – the presence of rejection, shouting, frowning, a cold/harsh voice by the mothers, as well as a generally tense room atmosphere. (5) Responsiveness (ranged between 1 = Never responds, to 7 = Constant negative affect throughout the task) – responsiveness to the child’s questions, comments, and behaviors, including the child’s verbal and nonverbal signals and requests. (6) On task (ranged between 1 = No interest in task, to 7 = Constant interest and persistence) - parent is engaged (initiative/persistence) in playing with the child as instructed by the researchers. (7) Verbalizations (ranged between 1 = Non, to 7 = Speaks throughout the interaction) – verbal communication with the child. (8) Competitiveness (1 = The mother plays, however she does not put emphasis on the need to finish the drawings or on the pace of the task; 2 = The mother plays and there is some emphasis on the need to finish the drawings or on the pace of the task, however she is not dictating the dyadic rhythm in the game; 3 = The mother plays and there is great emphasis on the need to finish the drawings or on the pace of the task – she is dictating the dyadic rhythm in the game) – the mother’s desire to “win” in the game. We added four additional sub-scales: (9) Social acceptance (1 = No expressions of social acceptance, 2 = Few expressions of social acceptance (one or two expressions), 3 = Many expressions of social acceptance (three expressions and above)) – the level to which the mother respects the child’s opinion and accepts modes of action other than her own. (10) Intolerance (1 = No expressions of intolerance, 2 = Few expressions of intolerance (one or two expressions), 3 = Many expressions of intolerance (three expressions and above)) – the level to which the mother forces a way of action and ignores the child’s offers. (11) Empathy (1 = No expressions of empathy, 2 = Few expressions of empathy (one or two expressions), 3 = Many expressions of empathy (three expressions and above)) – the level to which the mother tries to understand and identify with the feelings and emotions of the child. (12) Social disinterest (1 = No expressions of insensitivity, 2 = Few expressions of insensitivity (one or two expressions), 3 = Many expressions of insensitivity (three expressions and above)) – the mother does not try to understand the feelings and emotions of the child or reacts in an insensitive manner.

An exploratory factor analysis was performed on all 12 codes, extracting factors with Eigen values >1 as being acceptable. Principal component analysis with Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization was used for extraction. All loadings less than .35 were suppressed to avoid cross-loadings (Ledesma et al., Reference Ledesma, Ferrando, Trógolo, Poó, Tosi and Castro2021; Yong & Pearce, Reference Yong and Pearce2013). Table 1 summarizes factor loadings and variance. The observed codes converged into three factors that conceptually align with (1) Maladaptive parenting practices, (2) Adaptive parenting practices, and (3) Competitiveness.

Table 1. Parenting practices factor loadings matrix based on observed behaviors of the mother in the Etch-A-Sketch Task

Intelligence estimation. Mothers and children were tested with the Raven Standard and Colored Progressive Matrices (SPM, CPM; Raven & Raven, Reference Raven, Raven and McCallum2003), respectively, for ensuring normative intellectual development. Sum scores of correct responses were calculated.

Demographic variables. Mothers’ and children’s age, as well as children’s sex (0 = Male, 1 = Female) were used. Moreover, a SES factor was extracted using the principal component analysis method loaded by mothers’ years of education (.52), household income (.80), number of cars (.71) and number of household rooms (.68).

T2 controlled covariates

The mothers were asked if they have a safe-room in their house (0 = Yes, 1 = No), how much time they have to get inside the safe-room when a siren goes on (1 = Instant, 6 = 1.30 min), how much time (in hours) a day (on average) they watched news on all media platforms available to them, and if anyone from their close family/friends were hurt on the day of the attack (killed/murdered, kidnapped, injured or missing) and since the day of the attack. In order to account for the aggregated effect of having close family/friends who were hurt on the day of the attack, a summarized value was computed of all the eight items.

Analytical plan

Preliminary analyses and processing

First, in order to receive more robust factor scores, all the factors outlined in the Method section were computed on all available data (167 ≤ N ≤ 172). Afterwards, only cases with T2 reports were examined (N mothers = 104; N children = 101). In order to have more robust findings, multiple imputations process was performed on T1 variables. T2 were not imputed due to the nature of the data collection and the conceptual implications of the missingness. While T1 included both behavioral tasks and questionnaire data collected from mothers and their children in a relatively controlled setting, T2 involved only follow-up questionnaires sent to the mothers, focusing on post-traumatic symptoms experienced by them and their child 6 months after a traumatic event. Approximately half of the mothers did not respond at T2. The absence of responses may reflect meaningful psychological or contextual factors, such as avoidance or disengagement, which are relevant in the context of trauma. Therefore, we considered the missingness to be potentially nonrandom and theoretically informative, and opted to analyze only the available data rather than artificially filling in values that may not accurately reflect the participants’ true states.

Out of the T1 variables that had missing values (SES, child’s SDQ, parenting factors, and child’s PES), 16.5% of cases had at least one missing value, hence the data was imputed 17 times, as is considered acceptable. The data was missing completely at random (Little′s MCAR test: χ 2= 10.82, p = .930). Using the SPSS built-in function for multiple imputations, we used a linear regression model to impute each missing value. After the multiple imputations process, outlier detection and removal was performed, using Tukey’s method, resulting in 95 complete cases (out of 104 cases that answered T2). To determine which background variables should be controlled for in each part of the model, a zero-order correlation matrix was calculated.

Main analyses

In order to examine the mutual effects of the mother–child relation on PTSD symptoms, two separate hierarchical regression analyses were performed. The first examined the prediction of the child’s PTSD symptoms at T2 by their own PES at T1, their mother’s PTSD symptoms at T2, and the interaction effect between the two. The second examined the prediction of the mother’s PTSD symptoms at T2 by their own PES at T1, their child’s PTSD symptoms at T2, and the interaction effect between the two. For examining the interaction effects, simple slopes analyses were conducted.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Out of the total sample that was assessed at T2, eleven children (10.58%) and 13 mothers (12.87%) met the cutoff criteria of the PTSD questionnaires (i.e., score greater than 31). Moreover, about half of the mothers reported on having close family/friends who were hurt (i.e., killed/murdered, kidnapped, injured or missing) on the day of the attack (43.43%).

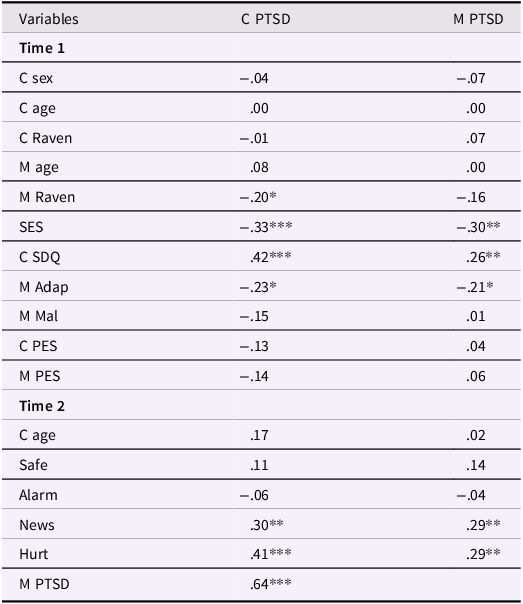

Zero-order correlations of the main variables and the possible covariates were examined (see Table 2). First, it was found that the child’s PTSD symptoms at T2 were correlated with their mother’s PTSD symptoms at T2 (r = .64, N = 98, p < .001), consistent with H1. Given the high correlation observed between maternal and child PTSD symptoms, and the fact that both measures were reported by the mother, we conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the potential inflation due to single-reporter bias. Assuming that shared method variance accounts for between 10 and 30% of the shared variance (as acceptable), the corrected correlation would range between approximately .33 ≤ r ≤ .56. This suggests that even under conservative assumptions, a moderate–high association would remain.

Table 2. Zero-order correlations between study variables after multiple imputations

Note. 95 ≤ N ≤ 101. C = child; M = mother; Sex = children’s sex (0 = Male, 1 = Female); SES = socioeconomic status factor; SDQ = socioemotional difficulties factor; Adap = adaptive parenting practices factor; Mal = maladaptive parenting practices factor; PES = post-error slowing effect; Safe = existence of a safe-room inside the house (0 = Yes, 1 = No); Alarm = how much time they have to get inside the safe-room when the alarm goes on; News = hours per day of watching news; Hurt = aggregated effect of objective experience of traumatic events; PTSD = PTSD symptoms; *p ≤ .05, **p ≤ .01, ***p ≤ .001, two-tailed.

Moreover, it was found that the child’s PTSD symptoms at T2 was correlated with their mother’s Raven score at T1 (r = −.20, N = 101, p = .042), SES at T1 (r = −.33, N = 101, p < .001), socioemotional difficulties at T1 (r = .42, N = 101, p < .001), adaptive parenting factor at T1 (r = −.23, N = 101, p = .022), news consumption at T2 (r = .30, N = 95, p = .003), and aggregated objective exposure at T2 (r = .41, N = 96, p < .001). As a result, all these variables were controlled for when predicting the child’s PTSD symptoms at T2.

Mother’s PTSD symptoms at T2 was correlated with SES at T1 (r = −.30, N = 98, p = .003), child’s socioemotional difficulties at T1 (r = .26, N = 98, p = .010), adaptive parenting factor at T1 (r = −.21, N = 98, p = .041), news consumption at T2 (r = .29, N = 95, p = .005), and aggregated objective exposure at T2 (r = .29, N = 96, p = .004). As a result, all these variables were controlled for when predicting the mothers’ PTSD symptoms at T2.

Main analyses

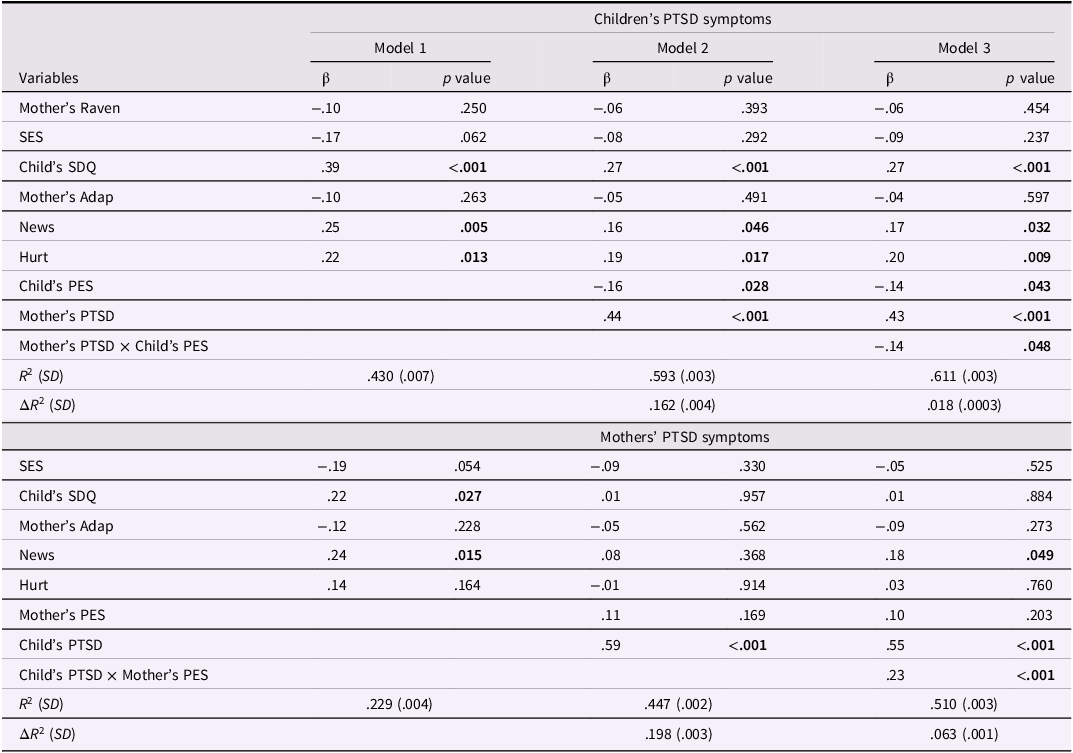

To test the study hypotheses, two three-step hierarchical linear regression analyses were conducted using pooled estimates from 17 imputed datasets, with child’s/mother’s PTSD symptoms as the dependent variable. First the analysis on the children will be presented and then on the mothers. All variables were standardized.

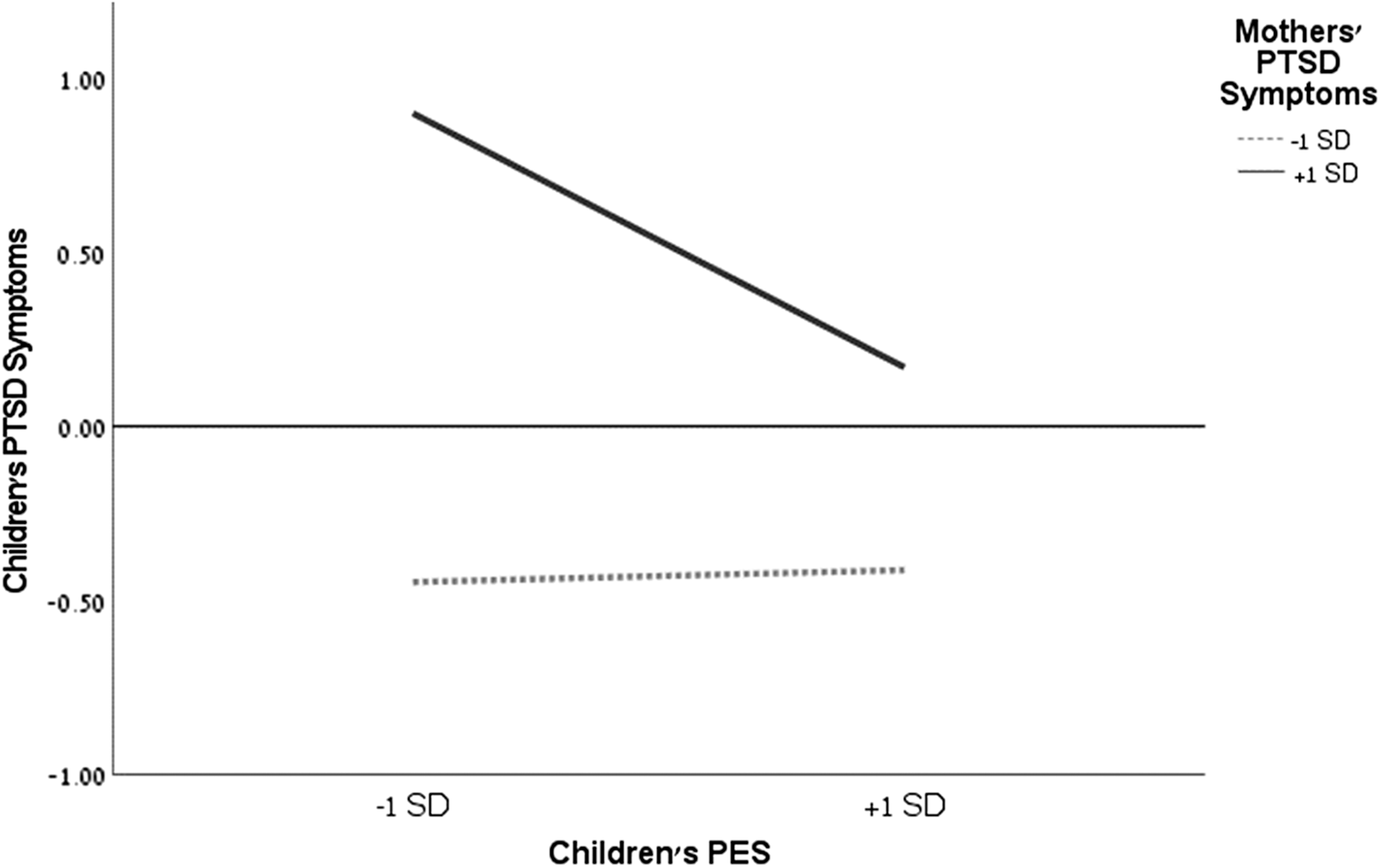

Children’s PTSD symptoms

Following the preliminary analysis, the first model included the background covariates, the second model added the child’s PES and mother’s PTSD symptoms, and the third model added their interaction effect. The first model accounted for an average of 43% (SD = .007) of the variance in the child’s PTSD symptoms. The second model explained an additional 16.2% (SD = .004) of the variance, for an average total of 59.3% (SD = .003). The third model explained an additional 1.8% (SD = .0003) of the variance, for an average total of 61.1% (SD = .003); see Table 3 for the full models’ results. Consistent with H2a, within the third model, there was a main effect for the children’s PES (β = −.14, p = .043) and mothers’ PTSD symptoms (β = .43, p < .001). Meaning, more developed PES of the child at T1 and lower PTSD symptoms of the mother were related to lower PTSD symptoms of the child. Moreover, the interaction between the children’s PES and their mothers’ PTSD symptoms was found to be significant (β = −.14, p = .048), beyond the effects of all the other variables, consistent with H3a. Simple slopes analysis revealed that when the mothers had high PTSD symptoms, there was a prediction of the child’s PES of their own PTSD symptoms (β = −.30, p = .006). Meaning, the more developed the child’s PES was at T1, the lower their PTSD symptoms were. When the mothers had low PTSD symptoms, there was no significant relationship between the child’s PES of their own PTSD symptoms (β = −.01, p = .903), and overall their PTSD symptoms level was below average (see Figure 2). In order to explore the moderating effect impact, Johnson–Neyman significance region analysis was conducted and revealed that the moderation effect was significant for 48% of the sample (Mothers’ PTSD = −.01, Slopeβ = −.15, p = .050).

Table 3. Hierarchical linear regression analysis predicting children’s and mothers’ PTSD symptoms after multiple imputations

Note. Nmothers = 95; Nchildren = 95. Number of imputations performed = 17. SES = socioeconomic status factor; SDQ = socioemotional difficulties factor; Adap = adaptive parenting practices factor; News = hours per day of watching news; Hurt = aggregated effect of objective experience of traumatic events; PES = post-error slowing effect; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder. Significant effects in bold.

Figure 2. Predicting children’s PTSD symptoms by the interaction effect between children’s PES and mothers’ PTSD symptoms. Note. Y-axis values are standardized and the thin horizontal line represents the average score; dashed line = insignificant slope; solid thick line = significant slope; PES = post-error slowing; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Mother’s PTSD symptoms

Following the preliminary analysis, the first model included the background covariates, the second model added the mothers’ PES and children’s PTSD symptoms, and the third model added their interaction effect. The first model accounted for an average of 24.9% (SD = .004) of the variance in the mothers’ PTSD symptoms. The second model explained an additional 19.8% (SD = .003) of the variance, for an average total of 44.7% (SD = .002). The third model explained an additional 6.3% (SD = .001) of the variance, for an average total of 51% (SD = .003); see Table 3 for the full models’ results. Within the third model, there was a main effect for the children’s PTSD symptoms (β = .55, p < .001), however there was no effect for the mothers’ PES (p > .05), inconsistent with H2b. Meaning, higher PTSD symptoms of the child were related to higher PTSD symptoms of the mother. Moreover, the interaction between the mother’s PES and the child’s PTSD symptoms was found to be significant (β = .23, p < .001), beyond the effects of all the other variables, consistent with H3b. Simple slopes analysis revealed that when the child had high PTSD symptoms, there was a prediction of the mother’s PES of their own PTSD symptoms (β = .33, p = .001). Meaning, the less developed the mother’s PES was at T1, the higher their PTSD symptoms were. When the child had low PTSD symptoms, there was no significant relationship between the mother’s PES of their own PTSD symptoms (β = −.10, p = .384), and overall their PTSD symptoms level was below average (see Figure 3). In order to explore the moderating effect impact, Johnson–Neyman significance region analysis was conducted and revealed that the moderation effect was significant for 29% of the sample (Children’s PTSD = .26, Slope β = .16, p = .050).

Figure 3. Predicting mothers’ PTSD symptoms by the interaction effect between mothers’ PES and children’s PTSD symptoms. Note. Y-axis values are standardized and the thin horizontal line represents the average score; dashed line = insignificant slope; solid thick line = significant slope; PES = post-error slowing; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine – using a prospective model – the predictive value of mothers’ and children’s PES, as an objective behavioral marker of self-regulation capacities for their own PTSD symptoms that develop under extreme, stressful conditions, and the moderating effect of the partner’s PTSD symptoms within mother–child dyads. The findings highlight the protective effect of more developed PES against psychopathology manifestation, and the mutual moderating effects of PTSD symptoms. Below we discuss in more detail each one of these findings separately.

PTSD prevalence

Although not the primary focus of our study, our findings regarding the prevalence of children exceeding the cutoff point show that ∼10% met the criteria in the current study. In contrast, prevalence estimates based on adult criteria stand at approximately 5%. The higher prevalence observed in our study may be attributed to context, as the children in this study were regularly exposed to traumatic events, culminating in the sudden attack on Israel’s southern border, which may have intensified their PTSD symptomatology.

Regarding the prevalence rate in adults, our findings showed that about ∼13% of the mothers met the cat-off criteria. Although this is three times larger than the 12-month prevalence among U.S adults (∼4%; APA, 2013), it is lower than the current estimation that stands at ∼24% (Schincariol et al., Reference Schincariol, Orrù, Otgaar, Sartori and Scarpazza2024). Yet, when compared to an Israeli context, our questionnaire-based estimation is relatively close to those of Hoffman et al. (Reference Hoffman, Diamond and Lipsitz2011) and Ben-Ezra et al. (Reference Ben-Ezra, Karatzias, Hyland, Brewin, Cloitre, Bisson, Roberts, Lueger-Schuster and Shevlin2018), which stand at 9%. The difference in estimations may indicate the importance of taking into account the cultural and regional socio-political climate.

Moreover, our findings might point to a worrying trajectory of incline in PTSD manifestation, as our estimation is a bit higher, and might represent under evaluation, as about half of the mothers did not respond to the T2 survey.

Mother–child relation in PTSD symptoms

As expected, mothers and their children showed a strong positive association in PTSD symptoms: mothers who reported higher levels of symptoms for themselves also reported higher levels of symptoms for their children. Importantly, this association remained high even after sensitivity analysis (.33≤r≤.56) and after checking unique contributions within the regression models (β = .43 and β = .55, predicting children’s and mothers’ PTSD symptoms, respectively). These findings are in line with previous research on an Indian post-tsunami sample (Exenberger et al., Reference Exenberger, Riedl, Rangaramanujam, Amirtharaj and Juen2019) and further elaborate it in an Israeli context. It emphasizes the bidirectional exchanges between the child and their caregiving environment, particularly within the parent–child dyad (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). Moreover, the current findings also highlight the substantial proportion of the variance in maternal and child symptoms that was explained by the severity of the partner’s symptoms within the dyad (i.e., maternal symptoms explained by child symptoms, and vice versa), in comparison to the interaction effects that accounted for a smaller proportion of variance. Although this does not undermine the meaningfulness of the interaction effects, it highlights the importance of considering environmental stressors in the proximal context and their significant impact on the development of psychopathology (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994). Symptoms of each member of the dyad exert a substantial and measurable impact on the other, highlighting the bidirectional and continuous flow between mother and child, which significantly contributes to the development of psychopathology. This aligns with previous findings emphasizing the critical role of non-supportive parental behavior in the development of children’s executive functions (Cuevas et al., Reference Cuevas, Deater-Deckard, Kim-Spoon, Watson, Morasch and Bell2014) as well as the close association between parental and child psychopathology (Dinshtein et al., Reference Dinshtein, Dekel and Polliack2011; Morand-Beaulieu et al., Reference Morand-Beaulieu, Banica, Freeman, Ethridge, Sandre and Weinberg2024).

Do more developed levels of PES predict lower PTSD symptoms following stressful events?

Initially it was hypothesized that more developed PES would predict a lower level of PTSD both for mothers and children; however, it was found only for children. Although relatively modest, the child’s PES effect had a unique contribution to the prediction of the child’s PTSD symptoms, beyond the effects of prior socioemotional difficulties of the child, the mother’s PTSD symptoms, the mother’s news consumption and objective exposure to traumatic events. However, no such unique effect was found for the mothers (rather, an interaction effect was found [discussed later]). This is the first prospective study in children showing the predictive value of a computerized measure of self-regulation for PTSD symptoms. Our findings demonstrate that individual differences in PES predict mental health, coping with ongoing high-stress situations, and PTSD. It is fully consistent and expands previous research claiming that more developed mechanisms of self-regulation might predict better coping with stressful real-life events and lower levels of psychopathology and PTSD (Koenen, Reference Koenen2006; Zweerings et al., Reference Zweerings, Pflieger, Mathiak, Zvyagintsev, Kacela, Flatten and Mathiak2018; and more). Moreover, this finding is consistent with the extensive literature showing that kindergarten is a pivotal time for the development of executive attention and error processing (Grammer et al., Reference Grammer, Carrasco, Gehring and Morrison2014; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rothbart and Posner2003; Rueda et al., Reference Rueda, Posner, Rothbart, Blair, Zelazo and Greenberg2016; Yeshua & Berger, Reference Yeshua and Berger2024), and that at this age individual differences in these functions have long-term implications for the ability of children to self-regulate and adapt when facing challenges (Calkins & Marcovitch, Reference Calkins, Marcovitch, Calkins and Bell2010; Howard & Williams, Reference Howard and Williams2018; Moffitt et al., Reference Moffitt, Arseneault, Belsky, Dickson, Hancox, Harrington, Houts, Poulton, Roberts, Ross, Sears, Thomson and Caspi2011).

Are there mutual moderating effects between mothers and children’s PTSD symptoms?

Mutual moderating effects were found in both directions of the child–mother dyads: Specifically, for children whose mothers exhibited high PTSD symptoms, more developed PES served as a protective factor predicting fewer PTSD symptoms. While for children whose mothers exhibited low PTSD symptoms, there was no relation between their PES and their PTSD symptoms and on average they showed lower symptomatology. Alongside these findings, similar results were found for the mothers. For mothers whose children exhibited high PTSD symptoms, more developed PES served as a protective factor predicting fewer maternal PTSD symptoms. While for mothers whose children exhibited low PTSD symptoms, there was no relation between their PES and their PTSD symptoms and on average they showed lower symptomatology.

These novel findings are fully consistent with a transactional view of development, where the child and the parent continuously affect each other in bidirectional exchanges (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010) and highlight the protective effect of more developed mechanisms of self-regulation against psychopathology, as was claimed in previous research (Koenen, Reference Koenen2006; Zweerings et al., Reference Zweerings, Pflieger, Mathiak, Zvyagintsev, Kacela, Flatten and Mathiak2018; and more), and further validate them using a prospective model.

Each member of the dyad’s psychopathology was shaped – and was being shaped – by the psychopathology of the other (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984; Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). These findings give further support for the role of the microsystem and proximal processes for producing and sustaining development (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994), and specifically, the moderating effect of the PTSD symptoms in the mother–child dyad as a proximal process. Moreover, it emphasizes the roles of regulatory resources, individual differences and contextual stressors as determinants of psychopathology (Belsky, Reference Belsky1984) and that the mutual exacerbations in the mother–child dyad might produce problematic behavior in both partners (Sameroff, Reference Sameroff2010). Another level that could be addressed as a valuable contributor for the psychopathological outcome is the chronosystem (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner, Gauvain and Cole1994), as the high-stress situation on the southern border of Israel has been long-lasting and climaxed in a large-scale traumatic event.

Applied implications

These findings carry important clinical implications, emphasizing the need for both individual and dyadic trauma-focused interventions. The mutual moderating effects observed between mothers’ and children’s PTSD symptoms suggest that targeting only one member of the dyad may be insufficient for meaningful and sustained improvement. Instead, integrative therapeutic approaches that address the trauma experiences, emotional processing, and self-regulation capacities of both the mother and the child are likely to be more effective. Such interventions can not only reduce individual symptomatology but also interrupt maladaptive feedback loops within the dyad, thereby promoting healthier relational dynamics.

Limitations and future research

There are several limitations in the current study, and several recommendations for future research. First, the sample was composed of mothers only. As there are differences between mothers and fathers (e.g., Kitamura et al., Reference Kitamura, Shikai, Uji, Hiramura, Tanaka and Shono2009), there is a great need in future research to include father–child dyads. Additionally, as this study was the first to present prospective findings relating self-regulation and PTSD, further replication and examination is needed using other indicators of self-regulation. Moreover, it is important to note that the effect sizes of the interaction effects as well as the main effect of children’s PES on their own PTSD symptoms were small. Yet, they were significant beyond the background covariates and the use of a laboratory-based indicator. Hence, it is valuable to further elaborate these findings using other indexes of self-regulation. Although the hypotheses that were retrospectively tested were very specific and clearly emanated from the literature, this was not an a priori or preregistered study, as no one could have predicted the stressful events that happened in reality.

Conclusions

This study highlights the notion that executive attention and error processing are basic underlying skills enabling coping with situational stress emanating from the immediate surrounding, especially when facing abnormally stressing situations.

Data availability statement

Availability of Data: The data are available at https://github.com/MaorYeshua/PES-PTSD.git

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers for their valuable comments, which have significantly improved the manuscript. We also wish to thank Mrs. Desiree Meloul for her careful review and formatting of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This study was partially supported by the Israel Science Foundation (AB; grant number 533/20).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical standards

The study was approved by the Human Subjects Research Committee of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, protocol number 2257-1.

Preregistration statement

This study was not preregistered due to the nature and timing of the research. All analyses were determined prior to conducting the statistical procedures.

AI statement

Generative AI tools (ChatGPT, OpenAI) were used solely for partial language editing. The authors wrote themselves and verified all content, ideas, data interpretations, and conclusions.

Contributor roles

Maor Yeshua, Ph.D. – Contributed to the study and manuscript conceptualization and data set creation. He conducted the analyses and drafted all the manuscript sections; Andrea Berger, Ph.D. – Contributed to the study and manuscript conceptualization, supervised the project, acquired funding, and reviewed and revised the overall manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.