1. Introduction

This paper presents a mathematical derivation of magnetic field anomalies in three dimensions induced by a tsunami generated by a slender fault. Recent field observations have shown that earthquake-generated tsunamis are able to induce a measurable modification of the Earth’s magnetic field (Toh et al. Reference Toh, Satake, Hamano, Fujii and Goto2011; Minami & Toh Reference Minami and Toh2013; Tatehata, Ichihara & Hamano Reference Tatehata, Ichihara and Hamano2015; Lin, Toh & Minami Reference Lin, Toh and Minami2021). Physically, this intriguing phenomenon is due to electromagnetic induction, whereby a conductor (seawater) that moves inside an existing magnetic field (the Earth’s) generates an electric field with associated electric currents, which in turn perturb the ambient magnetic field. The strength of this perturbation is proportional to the fluid conductivity

![]() $\sigma$

, speed

$\sigma$

, speed

![]() $u$

and length scale

$u$

and length scale

![]() $\lambda$

of the fluid motion (Galtier Reference Galtier2016). For a tsunami, the large speed

$\lambda$

of the fluid motion (Galtier Reference Galtier2016). For a tsunami, the large speed

![]() $u\sim 100\,\textrm{m s}^{-1}$

and length scale

$u\sim 100\,\textrm{m s}^{-1}$

and length scale

![]() $\lambda \sim 10^5\,\textrm{m}$

mean that the induced perturbation of the Earth’s magnetic field is strong enough to be detected by underwater geomagnetic observatories (Toh et al. Reference Toh, Satake, Hamano, Fujii and Goto2011).

$\lambda \sim 10^5\,\textrm{m}$

mean that the induced perturbation of the Earth’s magnetic field is strong enough to be detected by underwater geomagnetic observatories (Toh et al. Reference Toh, Satake, Hamano, Fujii and Goto2011).

Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023) recently derived the underlying mathematics explaining this interesting phenomenon, using an idealised two-dimensional geometry, with one-dimensional wave propagation along the longitudinal

![]() $x$

-axis. They showed that the tsunami-induced magnetic field is made by an evanescent component, fast decaying with time soon after the occurrence of the earthquake, and a transient oscillatory component which travels away from the epicentre. This oscillatory component, in turn, is made by a self-induction and a magnetic diffusion part. The self-induction part, proportional to an Airy function, moves jointly with the tsunami. However, the diffusive part, proportional to a Scorer function, displays a phase difference with respect to the tsunami and travels ahead of it. Developing a large-time asymptotic theory, Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023) showed that the relative importance of self-induction versus diffusive components depends on the magnetic Reynolds number,

$x$

-axis. They showed that the tsunami-induced magnetic field is made by an evanescent component, fast decaying with time soon after the occurrence of the earthquake, and a transient oscillatory component which travels away from the epicentre. This oscillatory component, in turn, is made by a self-induction and a magnetic diffusion part. The self-induction part, proportional to an Airy function, moves jointly with the tsunami. However, the diffusive part, proportional to a Scorer function, displays a phase difference with respect to the tsunami and travels ahead of it. Developing a large-time asymptotic theory, Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023) showed that the relative importance of self-induction versus diffusive components depends on the magnetic Reynolds number,

where

![]() $h$

is the water depth,

$h$

is the water depth,

![]() $g$

is gravity and

$g$

is gravity and

![]() $\eta$

is magnetic diffusivity, providing a mathematical framework to interpret the observations of Toh et al. (Reference Toh, Satake, Hamano, Fujii and Goto2011), Minami & Toh (Reference Minami and Toh2013) and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Baba, Linag, Shimizu and Utada2014a

).

$\eta$

is magnetic diffusivity, providing a mathematical framework to interpret the observations of Toh et al. (Reference Toh, Satake, Hamano, Fujii and Goto2011), Minami & Toh (Reference Minami and Toh2013) and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Baba, Linag, Shimizu and Utada2014a

).

Propagation in two horizontal dimensions is more complex and not fully investigated mathematically. Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Utada, Shimizu, Baba and Maeda2014b ) developed a three-dimensional electromagnetic (EM) induction code with a heterogeneous source term, based on the modified iterative dissipative method (MIDM). Their model showed good agreement with site data concerning the 2011 Tohōku tsunami at several locations in the Pacific Ocean. Minami et al. (Reference Minami, Toh, Ichihara and Kawashima2017) developed a finite element numerical model to simulate electromagnetic fields associated with tsunamis propagating over three-dimensional space with realistic smooth bathymetry. Their model shows that close to the epicentre, a linear long wave approximation is enough to characterise the associated magnetic anomaly. However, at greater distances from the epicentre, it is essential to include dispersive effects to accurately reproduce magnetic variations.

While previous numerical studies have made noteworthy contributions, there remains a distinct need for a mathematical model to provide deeper insights into the effects of dispersion in two-horizontal dimensions (2-HD) on the tsunami and induced magnetic field. A mathematical investigation of the problem can offer a clearer understanding of how 2-HD propagation influences the dynamics of the coupled tsunami–magnetic field system. This understanding is especially critical for the future development and reliability of tsunami early warning systems (TEWSs) based on magnetic field detection.

Here, we present a novel theory for electromagnetic anomalies induced by a tsunami generated by a slender fault, i.e. a deformation of the seabed whose lateral extension

![]() $2L$

is much larger than the longitudinal scale

$2L$

is much larger than the longitudinal scale

![]() $2d$

, so that there is a natural small parameter

$2d$

, so that there is a natural small parameter

![]() $\epsilon =d/L\ll 1$

. Large tsunamis frequently originate from slender seabed ruptures, where

$\epsilon =d/L\ll 1$

. Large tsunamis frequently originate from slender seabed ruptures, where

![]() $\epsilon$

typically decreases with increasing earthquake magnitude (Mei & Kadri Reference Mei and Kadri2018; Li, Mei & Chan Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019). It is also theoretically possible for less severe earthquakes to arise from slender faults (Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019).

$\epsilon$

typically decreases with increasing earthquake magnitude (Mei & Kadri Reference Mei and Kadri2018; Li, Mei & Chan Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019). It is also theoretically possible for less severe earthquakes to arise from slender faults (Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019).

Mei & Kadri (Reference Mei and Kadri2018) studied the propagation of underwater sound signals generated by a slender fault using a frequency-domain approach with a multiple-scale expansion in the spatial coordinates

![]() $X=\epsilon ^2x,Y=\epsilon x$

. A similar method was later employed by Williams, Kadri & Abdolali (Reference Williams, Kadri and Abdolali2021) for acoustic-gravity waves generated by multiple slender ruptures on an elastic seabed. This approach is well suited to acoustic-gravity waves because their dynamics are governed by discrete modal wavenumbers, given by the acoustic–gravity dispersion relation (Renzi & Dias Reference Renzi and Dias2014; Renzi Reference Renzi2017; Mei & Kadri Reference Mei and Kadri2018; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Kadri and Abdolali2021). In that setting, the solution naturally decomposes into a discrete set of propagating and evanescent modes whose spatial variation is weak and accumulates only over long ranges; hence, the introduction of explicit slow spatial coordinates. Once generated, the acoustic modes propagate transoceanically without coupling to the surface gravity wave, as they travel much faster (Renzi Reference Renzi2017; Mei & Kadri Reference Mei and Kadri2018).

$X=\epsilon ^2x,Y=\epsilon x$

. A similar method was later employed by Williams, Kadri & Abdolali (Reference Williams, Kadri and Abdolali2021) for acoustic-gravity waves generated by multiple slender ruptures on an elastic seabed. This approach is well suited to acoustic-gravity waves because their dynamics are governed by discrete modal wavenumbers, given by the acoustic–gravity dispersion relation (Renzi & Dias Reference Renzi and Dias2014; Renzi Reference Renzi2017; Mei & Kadri Reference Mei and Kadri2018; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Kadri and Abdolali2021). In that setting, the solution naturally decomposes into a discrete set of propagating and evanescent modes whose spatial variation is weak and accumulates only over long ranges; hence, the introduction of explicit slow spatial coordinates. Once generated, the acoustic modes propagate transoceanically without coupling to the surface gravity wave, as they travel much faster (Renzi Reference Renzi2017; Mei & Kadri Reference Mei and Kadri2018).

In contrast, the electromagnetic anomaly associated with a tsunami is a broadband signal continuously driven by the evolving surface gravity wave (Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023); hence, a broadband approach in the wavenumber domain is more appropriate. Following the framework of Mei, Stiassnie & Yue (Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005) (Chapter 14), we adopt a two-dimensional Fourier transform in the horizontal plane and then apply the method of multiple scales in time. We introduce two slow time scales,

![]() $t_1=\epsilon t$

,

$t_1=\epsilon t$

,

![]() $t_2=\epsilon ^2t$

, anticipating that the wavefront evolution occurs on time scales much longer than the generation process itself. We show that these temporal scales are required to resolve secularities arising at

$t_2=\epsilon ^2t$

, anticipating that the wavefront evolution occurs on time scales much longer than the generation process itself. We show that these temporal scales are required to resolve secularities arising at

![]() $O(\epsilon )$

and

$O(\epsilon )$

and

![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$

.

$O(\epsilon ^2)$

.

Using linearised potential flow theory, a double Fourier transform, to account for a broad band of wavelengths and propagation directions, and a multiple-scale perturbative approach with three timings (Michele, Renzi & Sammarco Reference Michele, Renzi and Sammarco2019), we determine the super slow evolution of the wave field and induced magnetic anomaly for transoceanic propagation at large distances from the fault. The framework is validated through comparison with deep-ocean hydrodynamic and magnetic observations from the 2011 Tōhoku-oki tsunami.

We show that lateral propagation along the main fault direction decreases the period of both the surface wave and induced magnetic anomaly with respect to a two-dimensional scenario. The initial seabed displacement generates transient waves propagating along a direction orthogonal to the fault. Over time, however, lateral propagation becomes significant, causing the wave fronts to stretch and bend, eventually spreading in all directions, though the main direction of travel remains the longitudinal one. The magnetic anomaly follows a similar pattern, but gradually separates from the tsunami, with the magnetic signal travelling ahead of the leading tsunami crest at large time. Remarkably, the distance between the leading magnetic signal and the leading tsunami crest is found to be proportional to the fault’s longitudinal scale.

Furthermore, we investigate the parametric dependence of surface wave behaviour and the induced magnetic field on lateral propagation and the magnetic Reynolds number. Our results demonstrate that increased lateral propagation diminishes the detectability of the magnetic anomaly. Finally, we derive an asymptotic formula for the magnetic anomaly associated with the leading long wave propagating ahead of the wave group. Remarkably, this formula provides highly accurate predictions, even under conditions of appreciable lateral propagation along the fault’s main axis. These findings offer valuable insights for the development of tsunami early warning systems based on the detection of magnetic precursors.

2. Mathematical model

We consider a magnetically conductive ocean layer of depth

![]() $h$

, bounded above by air and below by the seafloor. The magnetic diffusivity is

$h$

, bounded above by air and below by the seafloor. The magnetic diffusivity is

![]() $\eta =1/(\mu _0\sigma )$

, where

$\eta =1/(\mu _0\sigma )$

, where

![]() $\mu _0=4\pi \times 10^{-7}\,\textrm{N}\,\textrm{A}^{-2}$

is the permeability of free space and

$\mu _0=4\pi \times 10^{-7}\,\textrm{N}\,\textrm{A}^{-2}$

is the permeability of free space and

![]() $\sigma$

is the electrical conductivity (Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013; Minami, Toh & Tyler Reference Minami, Toh and Tyler2015). For seawater, the electrical conductivity is

$\sigma$

is the electrical conductivity (Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013; Minami, Toh & Tyler Reference Minami, Toh and Tyler2015). For seawater, the electrical conductivity is

![]() $\sigma _w\sim 2-6\,\textrm{S}\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

, depending on salinity, while for the seafloor, typical values are of the order

$\sigma _w\sim 2-6\,\textrm{S}\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

, depending on salinity, while for the seafloor, typical values are of the order

![]() $\sigma _s\sim 0.1\,\textrm{S}\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

. The electrical conductivity of air is of the order of

$\sigma _s\sim 0.1\,\textrm{S}\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

. The electrical conductivity of air is of the order of

![]() $\sigma _a\sim 1\times 10^{-15}\,\textrm{S}\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

and, hence, it can be neglected.

$\sigma _a\sim 1\times 10^{-15}\,\textrm{S}\,\textrm{m}^{-1}$

and, hence, it can be neglected.

Within the framework of kinematic dynamo theory (Galtier Reference Galtier2016), we assume that the small perturbation of the Earth’s magnetic field associated with the tsunami has negligible influence on the oceanic flow field. Hence, the hydrodynamic and electromagnetic problems are decoupled, see Tyler (Reference Tyler2005), Wang & Liu (Reference Wang and Liu2013) and Minami et al. (Reference Minami, Toh and Tyler2015). In the following, we will first solve the mathematical problem for the tsunami and then move to the magnetic field.

2.1. Tsunami

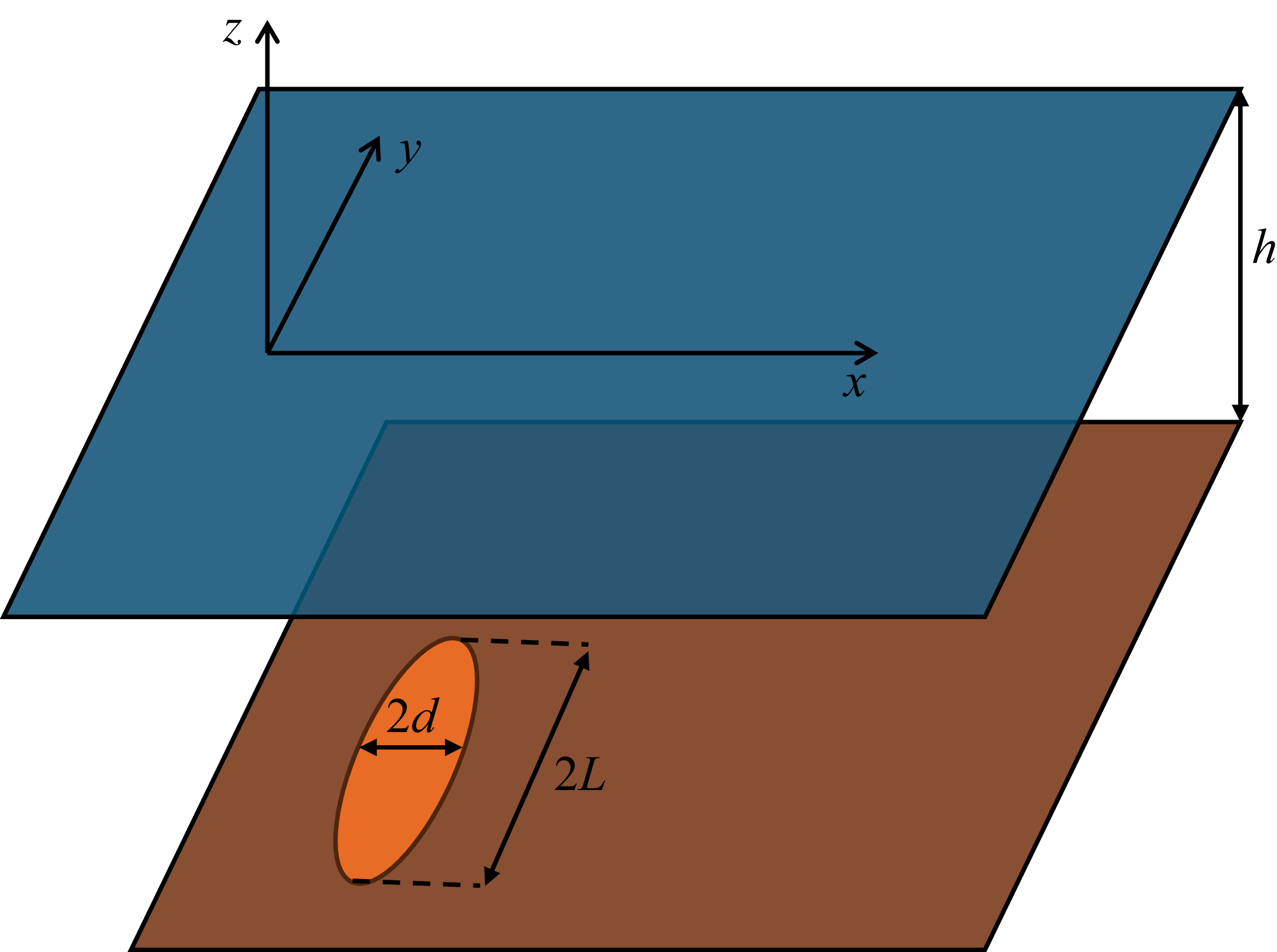

We develop a general model for transient dispersive waves generated by slender fault on an ocean of constant depth

![]() $h$

. Set a Cartesian reference frame with the

$h$

. Set a Cartesian reference frame with the

![]() $(x,y)$

plane on the undisturbed sea surface, with the

$(x,y)$

plane on the undisturbed sea surface, with the

![]() $x$

-axis along the main propagation direction and the vertical

$x$

-axis along the main propagation direction and the vertical

![]() $z$

-axis positive upwards, with its origin at the undisturbed sea level, as sketched in figure 1. Hence, the liquid layer occupies the region

$z$

-axis positive upwards, with its origin at the undisturbed sea level, as sketched in figure 1. Hence, the liquid layer occupies the region

![]() $-h\lt z\lt 0$

, while air is located at

$-h\lt z\lt 0$

, while air is located at

![]() $z\geqslant 0$

, and the seafloor is at

$z\geqslant 0$

, and the seafloor is at

![]() $z\leqslant -h$

.

$z\leqslant -h$

.

Figure 1. Sketch of the system’s geometry. The slender fault has characteristic width

![]() $2d$

much smaller than its length

$2d$

much smaller than its length

![]() $2L$

.

$2L$

.

The liquid is inviscid and incompressible and the motion is irrotational. Therefore, there exists a velocity potential

![]() $\varPhi (x,y,z,t)$

such that the velocity field

$\varPhi (x,y,z,t)$

such that the velocity field

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}=\boldsymbol{\nabla }\varPhi$

, where

$\boldsymbol {u}=\boldsymbol{\nabla }\varPhi$

, where

![]() $t$

is time. Wave motion is generated by a localised seabed displacement with vertical velocity

$t$

is time. Wave motion is generated by a localised seabed displacement with vertical velocity

![]() $W(x,y,t)$

, starting at time

$W(x,y,t)$

, starting at time

![]() $t=0$

. The rise time of seabed deformation at any cross-section is typically very short, of the order of a few minutes (Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019), which is much smaller than the time scale of tsunami propagation (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). Hence, we consider an instantaneous uplift of the seabed, whose surface is denoted by

$t=0$

. The rise time of seabed deformation at any cross-section is typically very short, of the order of a few minutes (Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019), which is much smaller than the time scale of tsunami propagation (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). Hence, we consider an instantaneous uplift of the seabed, whose surface is denoted by

![]() $z=-h$

for

$z=-h$

for

![]() $t\leqslant 0^-$

and by

$t\leqslant 0^-$

and by

![]() $z=-h+H_0$

for

$z=-h+H_0$

for

![]() $t\geqslant 0^+$

. The function

$t\geqslant 0^+$

. The function

![]() $H_0=H_0(x,y)\ll h$

describes a slender fault of characteristic width

$H_0=H_0(x,y)\ll h$

describes a slender fault of characteristic width

![]() $2d$

along the

$2d$

along the

![]() $x$

-axis and length

$x$

-axis and length

![]() $2L$

along the

$2L$

along the

![]() $y$

-axis, with

$y$

-axis, with

![]() $\epsilon =d/L\ll 1$

. In this context, we consider scenarios where

$\epsilon =d/L\ll 1$

. In this context, we consider scenarios where

![]() $d$

is finite and

$d$

is finite and

![]() $L\in \mathbb{R}^+$

, so that the limit

$L\in \mathbb{R}^+$

, so that the limit

![]() $\epsilon =0$

corresponds to a one-dimensional wave field excited by a fault of infinite length along the

$\epsilon =0$

corresponds to a one-dimensional wave field excited by a fault of infinite length along the

![]() $y$

-axis. The present formulation is valid for an arbitrary constant water depth

$y$

-axis. The present formulation is valid for an arbitrary constant water depth

![]() $h$

and does not rely on any asymptotic relationship between depth and the horizontal length scales of the problem. The seabed vertical velocity is

$h$

and does not rely on any asymptotic relationship between depth and the horizontal length scales of the problem. The seabed vertical velocity is

![]() $W(x,y,t)=H_0(x,y)\delta (t)$

, where

$W(x,y,t)=H_0(x,y)\delta (t)$

, where

![]() $\delta (t)$

is the Dirac delta distribution.

$\delta (t)$

is the Dirac delta distribution.

A typical seabed deformation generates a tsunami with an amplitude

![]() $a\sim 1\,\textrm{m}$

in open ocean and wavelength proportional to the deformation’s scale

$a\sim 1\,\textrm{m}$

in open ocean and wavelength proportional to the deformation’s scale

![]() $d$

, usually of the order

$d$

, usually of the order

![]() $10^3{-}10^5\,\textrm{m}$

(Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). Since the tsunami amplitude is much smaller than both its wavelength and the ocean depth, a linearised model can be used. Within the framework of linear potential flow theory, the velocity potential

$10^3{-}10^5\,\textrm{m}$

(Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). Since the tsunami amplitude is much smaller than both its wavelength and the ocean depth, a linearised model can be used. Within the framework of linear potential flow theory, the velocity potential

![]() $\varPhi (x,y,z,t)$

must satisfy the Laplace equation in the fluid domain and associated boundary conditions on the surface and at the seabed:

$\varPhi (x,y,z,t)$

must satisfy the Laplace equation in the fluid domain and associated boundary conditions on the surface and at the seabed:

where

![]() $g$

is the acceleration due to gravity,

$g$

is the acceleration due to gravity,

![]() $\zeta (x,y,t)$

is the free-surface elevation and

$\zeta (x,y,t)$

is the free-surface elevation and

![]() $|\boldsymbol{\nabla }H_0|$

is sufficiently small such that second-order terms are negligible (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005).

$|\boldsymbol{\nabla }H_0|$

is sufficiently small such that second-order terms are negligible (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005).

2.1.1. Non-dimensionalisation

Let us now introduce the following non-dimensional variables:

where

![]() $A\ll h$

is the maximum vertical displacement of the seabed. Hence, the boundary-value problem (BVP) in (2.1)–(2.4) becomes

$A\ll h$

is the maximum vertical displacement of the seabed. Hence, the boundary-value problem (BVP) in (2.1)–(2.4) becomes

where the property

![]() $\delta (\alpha t) = \delta (t)/|\alpha |$

has been used and

$\delta (\alpha t) = \delta (t)/|\alpha |$

has been used and

![]() $\beta =d/h$

.

$\beta =d/h$

.

Since

![]() $d$

and

$d$

and

![]() $h$

are both finite,

$h$

are both finite,

![]() $\beta =O(1)$

, i.e. a finite constant independent of

$\beta =O(1)$

, i.e. a finite constant independent of

![]() $\epsilon$

. Physically,

$\epsilon$

. Physically,

![]() $\mu =1/\beta =h/d$

measures the strength of frequency dispersion, as the dominant excited wavelength is controlled by the characteristic source scale

$\mu =1/\beta =h/d$

measures the strength of frequency dispersion, as the dominant excited wavelength is controlled by the characteristic source scale

![]() $d$

(Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019). Thus,

$d$

(Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019). Thus,

![]() $\beta =O(1)$

(equivalently

$\beta =O(1)$

(equivalently

![]() $\mu =O(1)$

) ensures that dispersive effects are fully retained. While

$\mu =O(1)$

) ensures that dispersive effects are fully retained. While

![]() $\varepsilon$

controls the geometric slenderness of the source, dispersive effects are governed by the geometric parameter

$\varepsilon$

controls the geometric slenderness of the source, dispersive effects are governed by the geometric parameter

![]() $\beta$

, with no asymptotic coupling between the two. Finally, in (2.6), the small parameter

$\beta$

, with no asymptotic coupling between the two. Finally, in (2.6), the small parameter

![]() $\varepsilon ^2$

introduces slow propagation along

$\varepsilon ^2$

introduces slow propagation along

![]() $y'$

.

$y'$

.

To consider a broad band of spatial scales and propagation directions, we introduce the Fourier transform pair

Using (2.10), combining (2.7)–(2.8) and dropping the primes for simplicity, the BVP (2.6)–(2.9) becomes

2.1.2. Multiple-scale analysis

To investigate the effect of emerging

![]() $y$

-axis propagation at large time, we introduce the slow and super-slow times

$y$

-axis propagation at large time, we introduce the slow and super-slow times

and concurrently expand the potential in powers of

![]() $\epsilon$

,

$\epsilon$

,

Substituting the latter expansion into the BVP (2.12)–(2.14) and noting that

we can now solve at each order of

![]() $\epsilon$

.

$\epsilon$

.

Leading order

![]() $O(1)$

$O(1)$

Retaining only terms independent of

![]() $\epsilon$

, the BVP reads

$\epsilon$

, the BVP reads

The solution to (2.18) is

Substituting the latter in (2.20), we find

Further substitution of (2.21) and (2.22) in (2.19) yields a differential equation for

![]() $B(t,t_1,t_2)$

, namely

$B(t,t_1,t_2)$

, namely

where

This dispersion relation is valid for

![]() $\beta =O(1)$

(i.e.

$\beta =O(1)$

(i.e.

![]() $\mu =O(1)$

) and naturally contains the weakly dispersive limit

$\mu =O(1)$

) and naturally contains the weakly dispersive limit

![]() $\beta \gg 1$

(

$\beta \gg 1$

(

![]() $\mu \ll 1$

) as a special case (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005).

$\mu \ll 1$

) as a special case (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005).

Because of the discontinuity at

![]() $t=0$

introduced by the Dirac delta, we solve (2.23) for

$t=0$

introduced by the Dirac delta, we solve (2.23) for

![]() $t\geqslant 0^+$

. Let us now consider the initial conditions associated with (2.23). Physically,

$t\geqslant 0^+$

. Let us now consider the initial conditions associated with (2.23). Physically,

![]() $B(t=0^+)$

represents an initial pressure impulse acting on the free surface (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). Since we do not consider surface pressure perturbations, we have

$B(t=0^+)$

represents an initial pressure impulse acting on the free surface (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). Since we do not consider surface pressure perturbations, we have

Furthermore, integrating (2.23) across the delta function yields

Hence, the fluid is set into motion because of an acceleration imparted by the seabed deformation during the instantaneous uplift.

The initial-value problem (2.23)–(2.26) yields

where

Finally, substitution of (2.22) and (2.27) into (2.21) gives the leading order potential for

![]() $t\gt 0^+$

,

$t\gt 0^+$

,

The free-surface elevation can now be determined from (2.8) by Fourier transforming with (2.10), introducing the slow times (2.15) and expanding

![]() $\hat \zeta$

in powers of

$\hat \zeta$

in powers of

![]() $\epsilon$

. At the zeroth order, it is

$\epsilon$

. At the zeroth order, it is

\begin{equation} \left . \hat \zeta _0=-\frac {\partial \hat \varPhi _0}{\partial t}\right |_{z=0}=\omega \left [a(t_1,t_2)\sin (\omega t)-b(t_1,t_2)\cos (\omega t)\right ]. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \left . \hat \zeta _0=-\frac {\partial \hat \varPhi _0}{\partial t}\right |_{z=0}=\omega \left [a(t_1,t_2)\sin (\omega t)-b(t_1,t_2)\cos (\omega t)\right ]. \end{equation}

The unknown amplitudes

![]() $a(t_1,t_2)$

and

$a(t_1,t_2)$

and

![]() $b(t_1,t_2)$

, satisfying the initial conditions (2.28), are to be determined at the higher orders.

$b(t_1,t_2)$

, satisfying the initial conditions (2.28), are to be determined at the higher orders.

Note that, in the two-dimensional limit

![]() $\epsilon =0$

, the seabed deformation

$\epsilon =0$

, the seabed deformation

![]() $H_0^{\prime}$

in (2.9) is a function of

$H_0^{\prime}$

in (2.9) is a function of

![]() $x'$

only. Hence, the Fourier transform (2.10) yields

$x'$

only. Hence, the Fourier transform (2.10) yields

![]() $\hat {H}_0=\breve {H}_0(k_x)\delta (k_y)$

, where

$\hat {H}_0=\breve {H}_0(k_x)\delta (k_y)$

, where

![]() $\breve {H}_0(k_x)$

is the one-dimensional Fourier transform of

$\breve {H}_0(k_x)$

is the one-dimensional Fourier transform of

![]() $H_0$

along

$H_0$

along

![]() $x$

, and again primes are dropped for simplicity. Following the same procedure as previously, but with

$x$

, and again primes are dropped for simplicity. Following the same procedure as previously, but with

![]() $t_1=t_2=0$

, the free-surface elevation in the Fourier space is

$t_1=t_2=0$

, the free-surface elevation in the Fourier space is

Inverse transform via (2.11) yields

As expected, the free-surface elevation (2.32) is one-dimensional and corresponds to the well-known solution of Mei et al. (Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). We now move to the higher orders of

![]() $\epsilon$

.

$\epsilon$

.

Order

![]() $O(\epsilon )$

$O(\epsilon )$

Retaining only terms proportional to

![]() $\epsilon$

, the BVP for

$\epsilon$

, the BVP for

![]() $\hat \varPhi _1$

reads

$\hat \varPhi _1$

reads

Again, (2.33) gives

Application of the homogeneous seabed boundary condition (2.35) yields

![]() $C=D\tanh (k_x/\beta )$

. Substituting (2.21) and (2.36) into the free-surface condition (2.34) yields

$C=D\tanh (k_x/\beta )$

. Substituting (2.21) and (2.36) into the free-surface condition (2.34) yields

Now, the inhomogeneous term on the right-hand side of (2.37) contains the homogeneous solution (

![]() $\sin (\omega t), \cos (\omega t)$

), making it a resonant forcing term. To avoid secularity, it must be

$\sin (\omega t), \cos (\omega t)$

), making it a resonant forcing term. To avoid secularity, it must be

This is possible for all

![]() $t\gt 0^+$

only if

$t\gt 0^+$

only if

![]() $a=a(t_2)$

and

$a=a(t_2)$

and

![]() $b=b(t_2)$

. Hence, the zeroth-order potential

$b=b(t_2)$

. Hence, the zeroth-order potential

![]() $\hat \varPhi _0$

(2.29) does not depend on

$\hat \varPhi _0$

(2.29) does not depend on

![]() $t_1$

. As a consequence, the BVP (2.33)–(2.35) is homogeneous. However, the homogeneous solution for

$t_1$

. As a consequence, the BVP (2.33)–(2.35) is homogeneous. However, the homogeneous solution for

![]() $t\gt 0^+$

is already contained in the zeroth-order term

$t\gt 0^+$

is already contained in the zeroth-order term

![]() $\hat \varPhi _0$

and, hence, it can be omitted, i.e.

$\hat \varPhi _0$

and, hence, it can be omitted, i.e.

![]() $\hat \varPhi _1=0$

. This is a consolidated procedure in the multiple-scale approach, for example, see Mei et al. (Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005).

$\hat \varPhi _1=0$

. This is a consolidated procedure in the multiple-scale approach, for example, see Mei et al. (Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005).

The equation for the free-surface elevation is

which yields trivially

![]() $\hat \zeta _1=0$

. The expressions for the unknown amplitudes

$\hat \zeta _1=0$

. The expressions for the unknown amplitudes

![]() $a(t_2)$

and

$a(t_2)$

and

![]() $b(t_2)$

must be found at the order

$b(t_2)$

must be found at the order

![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$

.

$O(\epsilon ^2)$

.

Order

![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$

$O(\epsilon ^2)$

At second order in

![]() $\epsilon$

, the BVP is

$\epsilon$

, the BVP is

hence, the leading order potential forces the lateral propagation along

![]() $y$

at order

$y$

at order

![]() $O(\epsilon ^2)$

.

$O(\epsilon ^2)$

.

The particular solution to (2.40) which satisfies (2.42) is

where again the homogeneous solution is discarded as it is already included at the leading order. Substituting (2.43) into the free-surface boundary condition (2.41) yields

where

Now, (2.44) is satisfied for all

![]() $t\gt 0^+$

only if

$t\gt 0^+$

only if

![]() $\varOmega _a=\varOmega _b=0$

. Cross-differentiating (2.45) and (2.46) yields a system of evolution equations for

$\varOmega _a=\varOmega _b=0$

. Cross-differentiating (2.45) and (2.46) yields a system of evolution equations for

![]() $a(t_2)$

and

$a(t_2)$

and

![]() $b(t_2)$

, namely

$b(t_2)$

, namely

\begin{align}& \frac {d^2a}{{\textrm{d}} t_2^2}+\left (\frac {\mathcal{F}}{2\omega } \right )^2a=0, \end{align}

\begin{align}& \frac {d^2a}{{\textrm{d}} t_2^2}+\left (\frac {\mathcal{F}}{2\omega } \right )^2a=0, \end{align}

where, making use of (2.24),

Solution of the system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs) (2.47)–(2.48), together with the initial conditions (2.28), yields

Substituting (2.50)–(2.51) back into (2.29) and recalling

![]() $t_2=\epsilon ^2 t$

yields the sought leading order potential in non-dimensional form

$t_2=\epsilon ^2 t$

yields the sought leading order potential in non-dimensional form

\begin{eqnarray} \hat \varPhi _0(z,t;k_x,k_y) = &-&\frac {\hat H_0(k_x,k_y)}{\omega \cosh (k_x/\beta )}\left [\tanh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right )\sinh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }z\right )+\cosh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }z \right )\right ]\nonumber \\ &\times & \sin \left [\left (\omega +\epsilon ^2\frac {k_y^2}{2k_x}C_{g}\right )t\right ]\!, \end{eqnarray}

\begin{eqnarray} \hat \varPhi _0(z,t;k_x,k_y) = &-&\frac {\hat H_0(k_x,k_y)}{\omega \cosh (k_x/\beta )}\left [\tanh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right )\sinh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }z\right )+\cosh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }z \right )\right ]\nonumber \\ &\times & \sin \left [\left (\omega +\epsilon ^2\frac {k_y^2}{2k_x}C_{g}\right )t\right ]\!, \end{eqnarray}

where, again, primes are omitted for the sake of simplicity and

is the group velocity in the

![]() $x$

direction. Substitution of (2.50)–(2.51) into (2.30) and inverse transformation (2.11) give the leading order free-surface elevation in non-dimensional form,

$x$

direction. Substitution of (2.50)–(2.51) into (2.30) and inverse transformation (2.11) give the leading order free-surface elevation in non-dimensional form,

where, again, primes are omitted for brevity and

is the higher-order effective frequency accounting for

![]() $y$

-axis propagation, which has a leading order effect in slowly modulating the wave field. Equation (2.54) highlights that the effect of 2-HD propagation is to increase the frequency (i.e. reduce the period) of each wave component, since

$y$

-axis propagation, which has a leading order effect in slowly modulating the wave field. Equation (2.54) highlights that the effect of 2-HD propagation is to increase the frequency (i.e. reduce the period) of each wave component, since

![]() $\tilde {\omega }\gt \omega$

. We next turn to the magnetic field.

$\tilde {\omega }\gt \omega$

. We next turn to the magnetic field.

2.2. Magnetic field

The magnetic formulation developed in the following applies to the deep-ocean regime, where the induction response is governed primarily by the large-scale tsunami flow and is least affected by coastal, bathymetric or site-specific conductivity effects. The total magnetic field in physical variables is

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {b}=(b_x,b_y,b_z)$

is the perturbation induced by the tsunami, generated by sea bed displacement, and

$\boldsymbol {b}=(b_x,b_y,b_z)$

is the perturbation induced by the tsunami, generated by sea bed displacement, and

is the steady Earth’s field. In (2.57),

![]() $I$

is the dip angle at which the magnetic field lines intersect the Earth’s surface (ranging from

$I$

is the dip angle at which the magnetic field lines intersect the Earth’s surface (ranging from

![]() $0^\circ$

at the equator to

$0^\circ$

at the equator to

![]() $90^\circ$

at the poles) and

$90^\circ$

at the poles) and

![]() $\varTheta$

is the angle between the wave propagation direction and the magnetic meridian (an imaginary line on the Earth’s surface that connects the magnetic north and south poles), see Wang & Liu (Reference Wang and Liu2013).

$\varTheta$

is the angle between the wave propagation direction and the magnetic meridian (an imaginary line on the Earth’s surface that connects the magnetic north and south poles), see Wang & Liu (Reference Wang and Liu2013).

Under the assumption that the characteristic speed of fluid flow is much smaller than the speed of light, the magnetic field

![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$

satisfies the induction equation for incompressible fluids in the non-relativistic limit,

$\boldsymbol {B}$

satisfies the induction equation for incompressible fluids in the non-relativistic limit,

where

![]() $\eta$

is the constant magnetic diffusivity (

$\eta$

is the constant magnetic diffusivity (

![]() $\textrm{m}^2\,\textrm{s}^{-1}$

) and

$\textrm{m}^2\,\textrm{s}^{-1}$

) and

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}=\boldsymbol{\nabla }\varPhi$

is the ocean’s velocity field (Gilbert Reference Gilbert2003; Galtier Reference Galtier2016). Equation (2.58) describes the induction of magnetic field

$\boldsymbol {u}=\boldsymbol{\nabla }\varPhi$

is the ocean’s velocity field (Gilbert Reference Gilbert2003; Galtier Reference Galtier2016). Equation (2.58) describes the induction of magnetic field

![]() $\boldsymbol {B}$

in a fluid medium moving with velocity

$\boldsymbol {B}$

in a fluid medium moving with velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}$

. Physically, the terms on the left-hand side of (2.58) represent the material derivative of the magnetic field. The first term on the right-hand side of (2.58) represents the field production by stretching of the magnetic flux lines (analogous to the vortex-stretching term in the vorticity equation, see Kundu, Cohen & Dowling Reference Kundu, Cohen and Dowling2016) and, finally, the second term on the right-hand side represents diffusional transport of the magnetic field (analogous to diffusion of vorticity by viscosity, see Moreau Reference Moreau1990). Similar dynamics is also found in mass/temperature transport, e.g. see Michele et al. (Reference Michele, Stuhlmeier and Borthwick2021, Reference Michele, Borthwick and van den Bremer2023). Now, let us consider the physical scales associated with (2.58). Typically,

$\boldsymbol {u}$

. Physically, the terms on the left-hand side of (2.58) represent the material derivative of the magnetic field. The first term on the right-hand side of (2.58) represents the field production by stretching of the magnetic flux lines (analogous to the vortex-stretching term in the vorticity equation, see Kundu, Cohen & Dowling Reference Kundu, Cohen and Dowling2016) and, finally, the second term on the right-hand side represents diffusional transport of the magnetic field (analogous to diffusion of vorticity by viscosity, see Moreau Reference Moreau1990). Similar dynamics is also found in mass/temperature transport, e.g. see Michele et al. (Reference Michele, Stuhlmeier and Borthwick2021, Reference Michele, Borthwick and van den Bremer2023). Now, let us consider the physical scales associated with (2.58). Typically,

![]() $|\boldsymbol {F}|=F\sim 10^4$

nT, whereas

$|\boldsymbol {F}|=F\sim 10^4$

nT, whereas

![]() $|\boldsymbol {b}|=b \sim 1-10$

nT; for example, see Minami & Toh (Reference Minami and Toh2013) and Wang & Liu (Reference Wang and Liu2013). Therefore,

$|\boldsymbol {b}|=b \sim 1-10$

nT; for example, see Minami & Toh (Reference Minami and Toh2013) and Wang & Liu (Reference Wang and Liu2013). Therefore,

![]() $b\ll F$

and the induction (2.58) simplifies into the kinematic dynamo equation

$b\ll F$

and the induction (2.58) simplifies into the kinematic dynamo equation

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {F}$

is assumed constant during the duration of the tsunami and second-order terms are neglected (see Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013; Minami, Schnepf & Toh Reference Minami, Schnepf and Toh2021; Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023).

$\boldsymbol {F}$

is assumed constant during the duration of the tsunami and second-order terms are neglected (see Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013; Minami, Schnepf & Toh Reference Minami, Schnepf and Toh2021; Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023).

In the air layer, the conductivity

![]() $\sigma _a\sim 0$

, and hence, the diffusivity

$\sigma _a\sim 0$

, and hence, the diffusivity

![]() $\eta =\eta _a\rightarrow \infty$

and (2.59) simplifies to

$\eta =\eta _a\rightarrow \infty$

and (2.59) simplifies to

In the water layer, the magnetic field satisfies

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {u}$

is the velocity associated with the wave field, and finally, in the seafloor layer,

$\boldsymbol {u}$

is the velocity associated with the wave field, and finally, in the seafloor layer,

where

![]() $\eta _w=1/(\mu _0\sigma _w)$

and

$\eta _w=1/(\mu _0\sigma _w)$

and

![]() $\eta _s=1/(\mu _0\sigma _s)$

represent the magnetic diffusivity in saltwater and the seafloor, respectively. We now turn to the boundary conditions: we require that

$\eta _s=1/(\mu _0\sigma _s)$

represent the magnetic diffusivity in saltwater and the seafloor, respectively. We now turn to the boundary conditions: we require that

![]() $|{\boldsymbol {b}}|$

be bounded in the far field as

$|{\boldsymbol {b}}|$

be bounded in the far field as

![]() $|z|\rightarrow \infty$

(Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013; Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023).

$|z|\rightarrow \infty$

(Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013; Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023).

2.2.1. Non-dimensionalisation and multiple scale analysis

Let us introduce the following non-dimensional quantities for the analysis of the magnetic field:

Applying the latter in combination with (2.5) to the governing equation (2.60), valid in the air region, yields

Similarly, the non-dimensional form of (2.61) becomes

\begin{align} & \big(F_x^{\prime},F_y^{\prime},F_z' \big)\, \begin{bmatrix} \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_x^{\prime}}{\partial x'} & \epsilon \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_x^{\prime}}{\partial y'} & \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_x^{\prime}}{\partial z'}\\ \\ \displaystyle \epsilon \frac {\partial u_y^{\prime}}{\partial x'} & \displaystyle \epsilon ^2\frac {\partial u_y^{\prime}}{\partial y'} & \epsilon \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_y^{\prime}}{\partial z'}\\ \\ \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_z^{\prime}}{\partial x'} &\epsilon \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_z^{\prime}}{\partial y'} & \beta ^2\displaystyle \frac {\partial u_z^{\prime}}{\partial z'} \end{bmatrix}^T\!, \quad z'\in (-1,0), \end{align}

\begin{align} & \big(F_x^{\prime},F_y^{\prime},F_z' \big)\, \begin{bmatrix} \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_x^{\prime}}{\partial x'} & \epsilon \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_x^{\prime}}{\partial y'} & \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_x^{\prime}}{\partial z'}\\ \\ \displaystyle \epsilon \frac {\partial u_y^{\prime}}{\partial x'} & \displaystyle \epsilon ^2\frac {\partial u_y^{\prime}}{\partial y'} & \epsilon \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_y^{\prime}}{\partial z'}\\ \\ \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_z^{\prime}}{\partial x'} &\epsilon \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial u_z^{\prime}}{\partial y'} & \beta ^2\displaystyle \frac {\partial u_z^{\prime}}{\partial z'} \end{bmatrix}^T\!, \quad z'\in (-1,0), \end{align}

where

![]() ${{R}_m^w}=h\sqrt {gh}/\eta _w$

is the magnetic Reynolds number of seawater. Finally, the non-dimensional form of the governing equation in the seafloor (2.62) is

${{R}_m^w}=h\sqrt {gh}/\eta _w$

is the magnetic Reynolds number of seawater. Finally, the non-dimensional form of the governing equation in the seafloor (2.62) is

where

![]() ${{R}_m^s}=h\sqrt {gh}/\eta _s\ll {{R}_m^w}$

. We emphasise that the fluid velocity vanishes in the seabed, so the usual definition of magnetic Reynolds number as the ratio of motional forcing to magnetic diffusion is not applicable. Here,

${{R}_m^s}=h\sqrt {gh}/\eta _s\ll {{R}_m^w}$

. We emphasise that the fluid velocity vanishes in the seabed, so the usual definition of magnetic Reynolds number as the ratio of motional forcing to magnetic diffusion is not applicable. Here,

![]() ${{R}_m^s}$

should instead be interpreted as a dimensionless magnetic diffusion parameter in the seafloor. We retain the notation for consistency with the seawater case, but note this distinction explicitly.

${{R}_m^s}$

should instead be interpreted as a dimensionless magnetic diffusion parameter in the seafloor. We retain the notation for consistency with the seawater case, but note this distinction explicitly.

Application of the double Fourier transform (2.10) to (2.64) yields

Similarly, (2.66) becomes

\begin{align} &\beta ^2 \frac {\partial \hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial t}-\frac {1}{{{R}_m^w}}\left [-k_x^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} -\epsilon ^2 k_y^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} +\beta ^2\frac {\partial ^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial z^2}\right ]= \end{align}

\begin{align} &\beta ^2 \frac {\partial \hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial t}-\frac {1}{{{R}_m^w}}\left [-k_x^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} -\epsilon ^2 k_y^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} +\beta ^2\frac {\partial ^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial z^2}\right ]= \end{align}

\begin{align} &(F_x,F_y,F_z)\, \begin{bmatrix} \displaystyle \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_x & \epsilon \textrm{i} k_y \hat {u}_x & \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_x}{\partial z}\\ \\ \epsilon \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_y & \epsilon ^2\textrm{i} k_y \hat {u}_y & \epsilon \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_y}{\partial z}\\ \\ \beta \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_z &\epsilon \beta \textrm{i} k_y \hat {u}_z & \beta ^2\displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_z}{\partial z} \end{bmatrix}^T \!,\quad z\in (-1,0), \end{align}

\begin{align} &(F_x,F_y,F_z)\, \begin{bmatrix} \displaystyle \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_x & \epsilon \textrm{i} k_y \hat {u}_x & \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_x}{\partial z}\\ \\ \epsilon \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_y & \epsilon ^2\textrm{i} k_y \hat {u}_y & \epsilon \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_y}{\partial z}\\ \\ \beta \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_z &\epsilon \beta \textrm{i} k_y \hat {u}_z & \beta ^2\displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_z}{\partial z} \end{bmatrix}^T \!,\quad z\in (-1,0), \end{align}

and finally, (2.67) becomes

\begin{align} &\beta ^2 \frac {\partial \hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial t}-\frac {1}{{{R}_m^s}}\left [-k_x^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} -\epsilon ^2 k_y^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} +\beta ^2\frac {\partial ^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial z^2}\right ]=0,\quad z\in (-\infty ,-1), \end{align}

\begin{align} &\beta ^2 \frac {\partial \hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial t}-\frac {1}{{{R}_m^s}}\left [-k_x^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} -\epsilon ^2 k_y^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}} +\beta ^2\frac {\partial ^2\hat {\boldsymbol {b}}}{\partial z^2}\right ]=0,\quad z\in (-\infty ,-1), \end{align}

where, again, primes have been dropped for the sake of simplicity.

Finally, let us introduce the multiple scales (2.15) and expand the magnetic and velocity fields in powers of the small parameter

![]() $\epsilon$

,

$\epsilon$

,

At the leading order, the governing equations (2.68)–(2.71) become

in the air layer,

\begin{align} &(F_x,F_y,F_z)\, \begin{bmatrix} \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_{x_0} & 0 & \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_{x_0}}{\partial z}\\ \\ 0 & 0 & 0\\ \\ \beta \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_{z_0} & 0 & \beta ^2\displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_{z_0}}{\partial z} \end{bmatrix}^T \!,\quad z\in (-1,0) \end{align}

\begin{align} &(F_x,F_y,F_z)\, \begin{bmatrix} \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_{x_0} & 0 & \beta \displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_{x_0}}{\partial z}\\ \\ 0 & 0 & 0\\ \\ \beta \textrm{i} k_x \hat {u}_{z_0} & 0 & \beta ^2\displaystyle \frac {\partial \hat {u}_{z_0}}{\partial z} \end{bmatrix}^T \!,\quad z\in (-1,0) \end{align}

in the water layer and

in the seafloor.

2.2.2. Vertical magnetic field

Field observations show that the vertical magnetic field component reaches its peak earlier than the horizontal component (Minami & Toh Reference Minami and Toh2013). Consequently, the vertical component is considered the most suitable for potential use in early warning systems. In this section, we focus on the vertical magnetic field. A similar procedure can also be applied to obtain the horizontal components, which, in some cases, can exhibit an initial rise, as discussed by Minami et al. (Reference Minami, Toh and Tyler2015).

In Fourier space, the vertical magnetic field

![]() $\hat {b}_{z_0}$

is governed by a Helmholtz equation in the air layer,

$\hat {b}_{z_0}$

is governed by a Helmholtz equation in the air layer,

a forced, linear equation of time-dependent Schrödinger form in the water layer,

where the substitution

![]() $\hat {u}_{z_0}=\partial \hat {\varPhi }_0/\partial z$

has been made (see 2.52), and a homogeneous time-dependent equation in the seafloor layer,

$\hat {u}_{z_0}=\partial \hat {\varPhi }_0/\partial z$

has been made (see 2.52), and a homogeneous time-dependent equation in the seafloor layer,

Finally, we request that

![]() $|\hat {b}_{z_0}|$

be bounded as

$|\hat {b}_{z_0}|$

be bounded as

![]() $|z|\rightarrow \infty$

. The system (2.77)–(2.79) can be solved separately in each domain and then matched by requesting that

$|z|\rightarrow \infty$

. The system (2.77)–(2.79) can be solved separately in each domain and then matched by requesting that

![]() $\hat {b}_{z_0}$

and

$\hat {b}_{z_0}$

and

![]() $\partial \hat {b}_{z_0}/\partial z$

be continuous at the interfaces

$\partial \hat {b}_{z_0}/\partial z$

be continuous at the interfaces

![]() $z=0$

(water–air) and

$z=0$

(water–air) and

![]() $z=-1$

(seabed–water). These matching conditions are a result of conservation of the magnetic flux

$z=-1$

(seabed–water). These matching conditions are a result of conservation of the magnetic flux

and continuity of the normal and tangential components of

![]() $\boldsymbol {b}$

across the air–water and water–soil interfaces, see Moreau (Reference Moreau1990) and Tyler (Reference Tyler2005). This boundary-value problem is solved here by means of a Green function approach (Morse & Feshback Reference Morse and Feshback1953).

$\boldsymbol {b}$

across the air–water and water–soil interfaces, see Moreau (Reference Moreau1990) and Tyler (Reference Tyler2005). This boundary-value problem is solved here by means of a Green function approach (Morse & Feshback Reference Morse and Feshback1953).

The Green function

![]() $G(z,\xi ,t;k_x,k_y)$

solves the governing equations (2.77)–(2.79) where the forcing term on the right-hand side of (2.78), valid in the liquid layer, is replaced by a double Dirac delta distribution

$G(z,\xi ,t;k_x,k_y)$

solves the governing equations (2.77)–(2.79) where the forcing term on the right-hand side of (2.78), valid in the liquid layer, is replaced by a double Dirac delta distribution

![]() $\delta (t-0^+)\delta (z-\xi )$

, with

$\delta (t-0^+)\delta (z-\xi )$

, with

![]() $\xi \in (-1,0)$

representing the vertical position of the source term, see Mei (Reference Mei1997) and Mei et al. (Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). The derivation of the Green function is detailed in Appendix A.

$\xi \in (-1,0)$

representing the vertical position of the source term, see Mei (Reference Mei1997) and Mei et al. (Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). The derivation of the Green function is detailed in Appendix A.

Use of Laplace’s convolution theorem and careful integration in the complex plane reveals that the vertical component of the magnetic field at the seabed is the sum of an evanescent part, which fast decays soon after generation, and a transient propagating component that travels away from the fault (see Appendix A). This physical picture is consistent with Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023)’s results in two dimensions. The magnetic signal at the seabed for transoceanic tsunami propagation is given by

\begin{align} b_{z0}(x,y,-1,t)&=\frac {1}{2\pi }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\left \{\mathcal{G}_+(k_x,k_y)\exp \left [\textrm{i}(k_x x+k_y y+\tilde \omega t) \right ]\right .\nonumber \\&\quad +\left .\mathcal{G}_-(k_x,k_y)\exp \left [\textrm{i}(k_x x+k_y y-\tilde \omega t) \right ]\right \}\, {\textrm{d}} k_x\, {\textrm{d}} k_y, \end{align}

\begin{align} b_{z0}(x,y,-1,t)&=\frac {1}{2\pi }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\left \{\mathcal{G}_+(k_x,k_y)\exp \left [\textrm{i}(k_x x+k_y y+\tilde \omega t) \right ]\right .\nonumber \\&\quad +\left .\mathcal{G}_-(k_x,k_y)\exp \left [\textrm{i}(k_x x+k_y y-\tilde \omega t) \right ]\right \}\, {\textrm{d}} k_x\, {\textrm{d}} k_y, \end{align}

where

![]() $\tilde {\omega }$

(2.55) is the modified frequency taking into account

$\tilde {\omega }$

(2.55) is the modified frequency taking into account

![]() $y$

-axis propagation. Still in (2.81),

$y$

-axis propagation. Still in (2.81),

![]() $\mathcal{G}_\pm (k_x,k_y) = \mathcal{G}(\pm \textrm{i}\omega ,k_x,k_y)$

, where

$\mathcal{G}_\pm (k_x,k_y) = \mathcal{G}(\pm \textrm{i}\omega ,k_x,k_y)$

, where

\begin{align} \mathcal{G}(s,k_x,k_y)&=-\frac {\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)}{2\omega \cosh ^2(k_x/\beta )}\frac {k_x^2}{\beta ^2}\left \{\alpha _w\left [-\textrm{i} F_x\frac {k_x}{\beta }\left (\cosh (\alpha _w)-\cosh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta } \right )\right ) \right .\right .\nonumber \\&\quad -\left . F_z\alpha _w\sinh (\alpha _w)+F_z\frac {k_x}{\beta }\sinh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right )\right ]+\frac {|k_x|}{\beta }\left [-\textrm{i} F_x \frac {k_x}{\beta }\sinh (\alpha _w) \nonumber \right .\\&\quad +\left .\left .\alpha _w\left (-F_z\cosh (\alpha _w)+F_z \cosh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right )+\textrm{i} F_x\sinh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right ) \right )\right ]\right \}\nonumber \\&\quad \times \left \{\tilde {\omega }\left [\alpha _w\left (\sigma \alpha _s+\frac {|k_x|}{\beta }\right )\cosh (\alpha _w)+\left (\alpha _w^2+\sigma \alpha _s\frac {|k_x|}{\beta } \right )\sinh (\alpha _w)\right ]\right \}^{-1}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \mathcal{G}(s,k_x,k_y)&=-\frac {\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)}{2\omega \cosh ^2(k_x/\beta )}\frac {k_x^2}{\beta ^2}\left \{\alpha _w\left [-\textrm{i} F_x\frac {k_x}{\beta }\left (\cosh (\alpha _w)-\cosh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta } \right )\right ) \right .\right .\nonumber \\&\quad -\left . F_z\alpha _w\sinh (\alpha _w)+F_z\frac {k_x}{\beta }\sinh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right )\right ]+\frac {|k_x|}{\beta }\left [-\textrm{i} F_x \frac {k_x}{\beta }\sinh (\alpha _w) \nonumber \right .\\&\quad +\left .\left .\alpha _w\left (-F_z\cosh (\alpha _w)+F_z \cosh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right )+\textrm{i} F_x\sinh \left (\frac {k_x}{\beta }\right ) \right )\right ]\right \}\nonumber \\&\quad \times \left \{\tilde {\omega }\left [\alpha _w\left (\sigma \alpha _s+\frac {|k_x|}{\beta }\right )\cosh (\alpha _w)+\left (\alpha _w^2+\sigma \alpha _s\frac {|k_x|}{\beta } \right )\sinh (\alpha _w)\right ]\right \}^{-1}. \end{align}

In (2.82),

![]() $\alpha _w(s,k_x)$

is the magnetic wavenumber in the water layer, given by (A11),

$\alpha _w(s,k_x)$

is the magnetic wavenumber in the water layer, given by (A11),

![]() $\alpha _s(s,k_x)$

is the magnetic wavenumber in the seabed layer, given by (A13), and

$\alpha _s(s,k_x)$

is the magnetic wavenumber in the seabed layer, given by (A13), and

![]() $\sigma =\textrm{sign}({Re}\{\alpha _s\})$

.

$\sigma =\textrm{sign}({Re}\{\alpha _s\})$

.

Equation (2.81) demonstrates that

![]() $y$

-axis propagation induces similar effects in the magnetic field as it does in the wave field, notably increasing the frequency of the signal components compared with one-horizontal-dimension (1-HD) propagation. In the following section, we derive an asymptotic formula for the magnetic anomaly induced by the leading long wave which separates from the group at very large distance from the fault.

$y$

-axis propagation induces similar effects in the magnetic field as it does in the wave field, notably increasing the frequency of the signal components compared with one-horizontal-dimension (1-HD) propagation. In the following section, we derive an asymptotic formula for the magnetic anomaly induced by the leading long wave which separates from the group at very large distance from the fault.

3. Asymptotic formula at very large distance from the fault

In this section, we derive an asymptotic formula for the magnetic signal associated with the leading long wave, in the weakly dispersive limit

![]() $\beta \gg 1$

(equivalently,

$\beta \gg 1$

(equivalently,

![]() $\mu \ll 1$

). For the sake of simplicity, we consider a symmetric deformation of the seabed with respect to both

$\mu \ll 1$

). For the sake of simplicity, we consider a symmetric deformation of the seabed with respect to both

![]() $x$

- and

$x$

- and

![]() $y$

-axes; similar calculations can be undertaken for more complex geometries, using superposition of effects (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). As a result of symmetry,

$y$

-axes; similar calculations can be undertaken for more complex geometries, using superposition of effects (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005). As a result of symmetry,

![]() $\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)$

is real and even in

$\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)$

is real and even in

![]() $k_x$

and

$k_x$

and

![]() $k_y$

, and after some lengthy algebra, (2.54) becomes

$k_y$

, and after some lengthy algebra, (2.54) becomes

\begin{align} \zeta _0(x,y,t) &= \frac {1}{2\pi }{\textrm{Re}} \Biggl \{ \int _0^{\infty }\int _0^\infty \frac {\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)}{\cosh (k_x/\beta )}\Bigl [\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}+\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}\Bigr ]\,{\textrm{d}} k_x\,{\textrm{d}} k_y \Biggr \}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \zeta _0(x,y,t) &= \frac {1}{2\pi }{\textrm{Re}} \Biggl \{ \int _0^{\infty }\int _0^\infty \frac {\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)}{\cosh (k_x/\beta )}\Bigl [\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}+\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}\Bigr ]\,{\textrm{d}} k_x\,{\textrm{d}} k_y \Biggr \}. \end{align}

To obtain an approximation for the magnetic field at large distance from the fault, consider an observer at

![]() $x\gt 0$

,

$x\gt 0$

,

![]() $y\gt 0$

(similar considerations can be made for observers at other locations). At large distance from the epicentre, i.e.

$y\gt 0$

(similar considerations can be made for observers at other locations). At large distance from the epicentre, i.e.

![]() $|\boldsymbol {x}|=|(x,y)|\gg 1$

, only outgoing waves survive (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005), so that (3.1) can be rewritten more compactly as

$|\boldsymbol {x}|=|(x,y)|\gg 1$

, only outgoing waves survive (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005), so that (3.1) can be rewritten more compactly as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol {k}=(k_x,k_y)$

is the wavenumber vector,

$\boldsymbol {k}=(k_x,k_y)$

is the wavenumber vector,

is a forcing function and

is the solution for an outgoing monochromatic wave in the transformed space, but accounting for the perturbed frequency

![]() $\tilde \omega$

(2.55). Note that the integral form (3.2) for the free-surface elevation is common to other linear-system responses, such as tsunamis generated by landslides (Renzi & Sammarco Reference Renzi and Sammarco2010).

$\tilde \omega$

(2.55). Note that the integral form (3.2) for the free-surface elevation is common to other linear-system responses, such as tsunamis generated by landslides (Renzi & Sammarco Reference Renzi and Sammarco2010).

In the limit

![]() ${{R}_m^s}\rightarrow 0$

(i.e. for an insulating seabed), the governing equation (2.75) for the vertical magnetic field in the water layer and the expression for the free-surface elevation (3.2) share the same functional structure as the relationships derived for one-dimensional propagation over insulating seabed by Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023). They showed that if the leading surface wave has the expression

${{R}_m^s}\rightarrow 0$

(i.e. for an insulating seabed), the governing equation (2.75) for the vertical magnetic field in the water layer and the expression for the free-surface elevation (3.2) share the same functional structure as the relationships derived for one-dimensional propagation over insulating seabed by Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023). They showed that if the leading surface wave has the expression

then a Boussinesq expansion of the phase function in the weakly dispersive regime (

![]() $\beta \gg 1$

) yields

$\beta \gg 1$

) yields

for the vertical magnetic field at the seabed (

![]() $z=-1)$

, where

$z=-1)$

, where

![]() $\mathscr{a}$

and

$\mathscr{a}$

and

![]() $\mathscr{b}$

are complex constants related by

$\mathscr{b}$

are complex constants related by

and

![]() $\chi (x,t)$

is a function representing the wave profile. Remarkably, this corresponds to a time-dependent extension for transient motion of the original Tyler formula, which is valid for long waves in simple harmonic motion, where

$\chi (x,t)$

is a function representing the wave profile. Remarkably, this corresponds to a time-dependent extension for transient motion of the original Tyler formula, which is valid for long waves in simple harmonic motion, where

![]() $\chi =\exp (i(k_x x-\omega t))$

, see Tyler (Reference Tyler2005).

$\chi =\exp (i(k_x x-\omega t))$

, see Tyler (Reference Tyler2005).

The main distinction between our problem and that of Renzi & Mazza (Reference Renzi and Mazza2023) is that the magnetic field and free-surface elevation now depend on both the longitudinal wavenumber

![]() $k_x$

and the transverse wavenumber

$k_x$

and the transverse wavenumber

![]() $k_y$

. If we write (3.2) as

$k_y$

. If we write (3.2) as

where

it is plausible to expect that for slow lateral propagation and because of linearity, the magnetic field is

where relationship (3.7) still applies at all transverse coordinates

![]() $y$

, but with the local wavenumber

$y$

, but with the local wavenumber

![]() $\boldsymbol {k}$

. This assumption is analogous to using the constant-depth dispersion relation, but with the local depth, in the context of the mild slope equation (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005; Renzi Reference Renzi2017). Hence, the magnetic field associated with the leading long wave at large distance from the fault is

$\boldsymbol {k}$

. This assumption is analogous to using the constant-depth dispersion relation, but with the local depth, in the context of the mild slope equation (Mei et al. Reference Mei, Stiassnie and Yue2005; Renzi Reference Renzi2017). Hence, the magnetic field associated with the leading long wave at large distance from the fault is

Using a similar argument for the remaining directions of propagation in (3.1) and combining everything together, the vertical component of the magnetic field for all

![]() $(x,y)$

at large distance from the epicentre reads

$(x,y)$

at large distance from the epicentre reads

where

\begin{align} \psi (x,y,t;k_x,k_y) &= \frac {\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)}{\cosh (k_x/\beta )}\Bigl [\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}+\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}+\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}\Bigr ]. \end{align}

\begin{align} \psi (x,y,t;k_x,k_y) &= \frac {\hat {H}_0(k_x,k_y)}{\cosh (k_x/\beta )}\Bigl [\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}+\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x+k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )} \nonumber\\ &\quad +\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y+\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}+\exp {\left (\textrm{i} (k_x x-k_y y-\tilde {\omega }t)\right )}\Bigr ]. \end{align}

Expressions (3.12)–(3.13) are algebraically simpler than the full solution (2.81)–(2.82) and, therefore, they are significantly easier and faster to calculate. This result has important practical implications, because (3.7) can be also solved for

![]() $\mathscr{a}$

as a function of

$\mathscr{a}$

as a function of

![]() $\mathscr{b}$

. This enables one to solve the inverse problem of finding the free-surface elevation of a tsunami corresponding to a recorded geomagnetic signal, for example, see Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Toh and Minami2021).

$\mathscr{b}$

. This enables one to solve the inverse problem of finding the free-surface elevation of a tsunami corresponding to a recorded geomagnetic signal, for example, see Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Toh and Minami2021).

4. Modelling benchmark: the 2011 Tōhoku tsunami

We consider the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku–oki tsunami to benchmark the theoretical model derived previously. The source is taken at the earthquake hypocentre

![]() $(38.103^\circ \textrm{N}, 142.{}860^\circ \textrm{E})$

, and wave propagation is examined towards the deep-ocean DART buoys 21 401

$(38.103^\circ \textrm{N}, 142.{}860^\circ \textrm{E})$

, and wave propagation is examined towards the deep-ocean DART buoys 21 401

![]() $(42.617^\circ \textrm{N},\,152.583^\circ \textrm{E})$

and 21 419

$(42.617^\circ \textrm{N},\,152.583^\circ \textrm{E})$

and 21 419

![]() $(44.455^\circ \textrm{N},\,155.736^\circ \textrm{E})$

, located at epicentral distances of approximately

$(44.455^\circ \textrm{N},\,155.736^\circ \textrm{E})$

, located at epicentral distances of approximately

![]() $965\,\textrm{km}$

and

$965\,\textrm{km}$

and

![]() $1287\,\textrm{km}$

, respectively (see figure 2 and Minami et al. Reference Minami, Toh, Ichihara and Kawashima2017).

$1287\,\textrm{km}$

, respectively (see figure 2 and Minami et al. Reference Minami, Toh, Ichihara and Kawashima2017).

Figure 2. Location of the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku–oki earthquake hypocentre (HC), the deep-ocean DART buoys 21 401 and 21 419, and the NWP geomagnetic seafloor station. Map data © 2025 Google, TMap Mobility Imagery ©NASA.

A local Cartesian reference frame is introduced with origin at the hypocentre, the

![]() $y$

-axis aligned with the main fault strike (

$y$

-axis aligned with the main fault strike (

![]() $\approx 25^\circ$

) and the

$\approx 25^\circ$

) and the

![]() $x$

-axis orthogonal to it. The earthquake source is represented using a simplified geometric model consistent with published rupture dimensions for the Tōhoku event. Finite-fault and tsunami waveform inversion studies indicate rupture extents of the order of

$x$

-axis orthogonal to it. The earthquake source is represented using a simplified geometric model consistent with published rupture dimensions for the Tōhoku event. Finite-fault and tsunami waveform inversion studies indicate rupture extents of the order of

![]() $400\,\textrm{km}$

in length and

$400\,\textrm{km}$

in length and

![]() $180\,\textrm{km}$

in width (Yagi & Fukahata Reference Yagi and Fukahata2011). Accordingly, we adopt an effective source of dimensions

$180\,\textrm{km}$

in width (Yagi & Fukahata Reference Yagi and Fukahata2011). Accordingly, we adopt an effective source of dimensions

![]() $2L=400\,\textrm{km}$

and

$2L=400\,\textrm{km}$

and

![]() $2d=180\,\textrm{km}$

, and prescribe the vertical seabed deformation using a smooth Gaussian distribution (Sammarco & Renzi Reference Sammarco and Renzi2008; Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023) characterised by half-widths

$2d=180\,\textrm{km}$

, and prescribe the vertical seabed deformation using a smooth Gaussian distribution (Sammarco & Renzi Reference Sammarco and Renzi2008; Renzi & Mazza Reference Renzi and Mazza2023) characterised by half-widths

![]() $L$

and

$L$

and

![]() $d$

comparable to these geometric scales; hence, back to physical variables

$d$

comparable to these geometric scales; hence, back to physical variables

This idealised representation captures the dominant spatial extent of the coseismic deformation.

Wave propagation is modelled over a flat seabed of constant depth

![]() $h$

. We adopt an effective depth

$h$

. We adopt an effective depth

![]() $h=4500\,\textrm{m}$

, corresponding approximately to the mean of the bathymetric depth near the source region (

$h=4500\,\textrm{m}$

, corresponding approximately to the mean of the bathymetric depth near the source region (

![]() ${\approx} 3800\,\textrm{m}$

) and at the receivers (

${\approx} 3800\,\textrm{m}$

) and at the receivers (

![]() ${\approx} 5200\,\textrm{m}$

). Since the coseismic deformation is applied instantaneously in the present model, the comparisons are made relative to an effective source time. Taking the rupture duration to be

${\approx} 5200\,\textrm{m}$

). Since the coseismic deformation is applied instantaneously in the present model, the comparisons are made relative to an effective source time. Taking the rupture duration to be

![]() ${\sim} 6\,\textrm{min}$

(Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019), we interpret

${\sim} 6\,\textrm{min}$

(Li et al. Reference Li, Mei and Chan2019), we interpret

![]() $t=0$

as the centroid of moment release, corresponding to a uniform time shift of

$t=0$

as the centroid of moment release, corresponding to a uniform time shift of

![]() ${\sim} 3\,\textrm{min}$

relative to the earthquake origin time.

${\sim} 3\,\textrm{min}$

relative to the earthquake origin time.

The peak amplitude

![]() $A$

of the Gaussian seabed uplift is selected based on the displaced water volume. For a Gaussian source, the displaced volume is

$A$

of the Gaussian seabed uplift is selected based on the displaced water volume. For a Gaussian source, the displaced volume is

![]() $V=\iint H_0\,\textrm{d}x\,\textrm{d}y = A\pi \,{\rm d}L$

. Using

$V=\iint H_0\,\textrm{d}x\,\textrm{d}y = A\pi \,{\rm d}L$

. Using

![]() $A=11\,\textrm{m}$

yields

$A=11\,\textrm{m}$

yields

![]() $V\approx 6.2\times 10^{11}\,\textrm{m}^3$

, corresponding to an equivalent uniform vertical displacement of approximately

$V\approx 6.2\times 10^{11}\,\textrm{m}^3$

, corresponding to an equivalent uniform vertical displacement of approximately

![]() $9\,\textrm{m}$

over the

$9\,\textrm{m}$

over the

![]() $400\times 180\,\textrm{km}^2$

source region. This magnitude is consistent with the overall scale of coseismic deformation inferred from tsunami waveform inversions of the Tōhoku earthquake, which report mean slip amplitudes of approximately

$400\times 180\,\textrm{km}^2$

source region. This magnitude is consistent with the overall scale of coseismic deformation inferred from tsunami waveform inversions of the Tōhoku earthquake, which report mean slip amplitudes of approximately

![]() $9\,\textrm{m}$

over comparable areas (Satake et al. Reference Satake, Fujii, Harada and Namegaya2013). The parameter

$9\,\textrm{m}$

over comparable areas (Satake et al. Reference Satake, Fujii, Harada and Namegaya2013). The parameter

![]() $A$

should therefore be interpreted as an effective source amplitude that reproduces a realistic displaced water volume.

$A$

should therefore be interpreted as an effective source amplitude that reproduces a realistic displaced water volume.

For the present geometry, the resulting value of the small parameter is

![]() $\epsilon =0.45$

, which remains below unity, but is not

$\epsilon =0.45$

, which remains below unity, but is not

![]() $\ll 1$

, placing the model at the upper limit of its formal range of applicability. The parameter

$\ll 1$

, placing the model at the upper limit of its formal range of applicability. The parameter

![]() $\beta =20$

, so that the dispersion parameter

$\beta =20$

, so that the dispersion parameter

![]() $\mu =1/\beta =0.05$

, indicates that wave propagation in the transoceanic region is only weakly dispersive.

$\mu =1/\beta =0.05$

, indicates that wave propagation in the transoceanic region is only weakly dispersive.

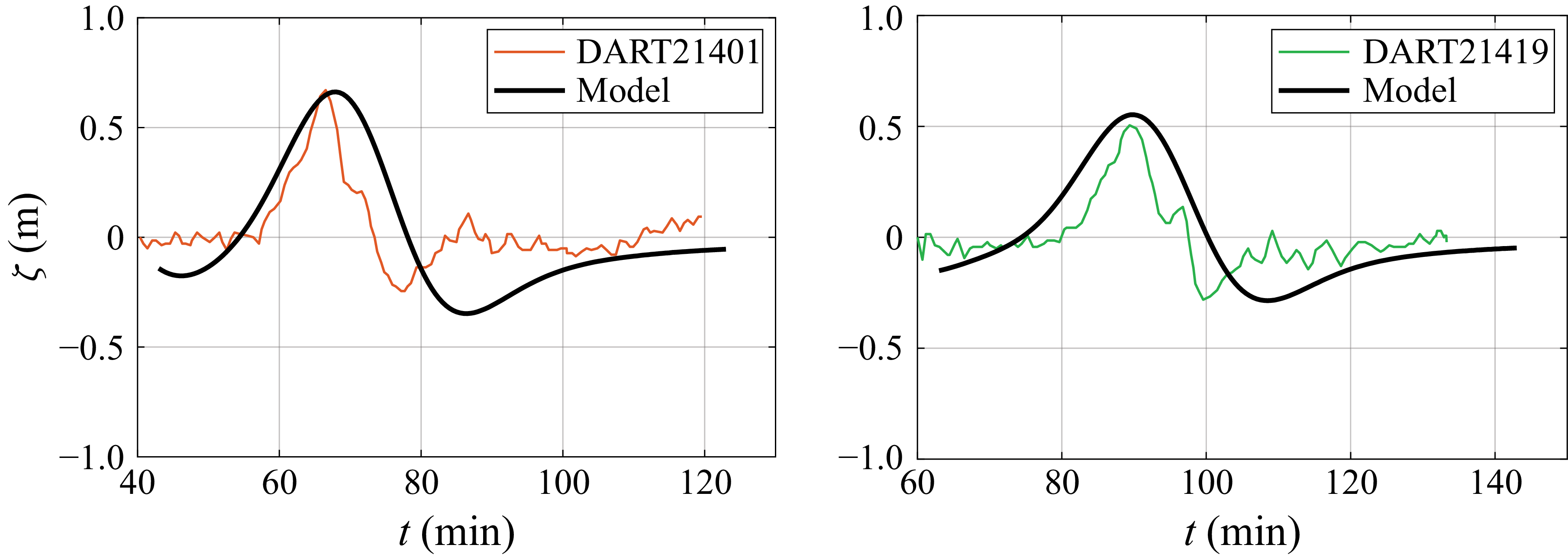

Figure 3. Comparison between leading-order free-surface elevation (2.54) and deep-ocean DART observations at stations 21 401 and 21 419 for the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku–oki tsunami. The DART records were digitised from Minami et al. (Reference Minami, Toh, Ichihara and Kawashima2017). Parameters are

![]() $\epsilon =0.45$

and

$\epsilon =0.45$

and

![]() $\beta =20$

. Time is in minutes since the earthquake occurrence. The comparison illustrates the ability of the idealised hydrodynamic model to reproduce the timing, polarity and amplitude of the leading tsunami signal at basin scale.

$\beta =20$

. Time is in minutes since the earthquake occurrence. The comparison illustrates the ability of the idealised hydrodynamic model to reproduce the timing, polarity and amplitude of the leading tsunami signal at basin scale.

Figure 3 compares the modelled free-surface elevation with the deep-ocean DART records at stations 21 401 and 21 419. Despite the idealised nature of the hydrodynamic model, the arrival times of the leading tsunami signal are reproduced with good accuracy at both locations, confirming that the modelling approach captures the dominant propagation speed over basin scales. The polarity and overall amplitude of the first wave are also correctly represented. Discrepancies in the detailed waveform shape and in later oscillations are expected, as these features are sensitive to bathymetric variability introducing wave refraction and reflection, which are neglected in the present flat-bottom framework. The comparison is therefore intended as a benchmark of the hydrodynamic wave propagation component, demonstrating that even at the upper limit of its formal asymptotic range, the model reproduces the correct arrival times, polarity and amplitude scale of the tsunami signal at deep-ocean stations.

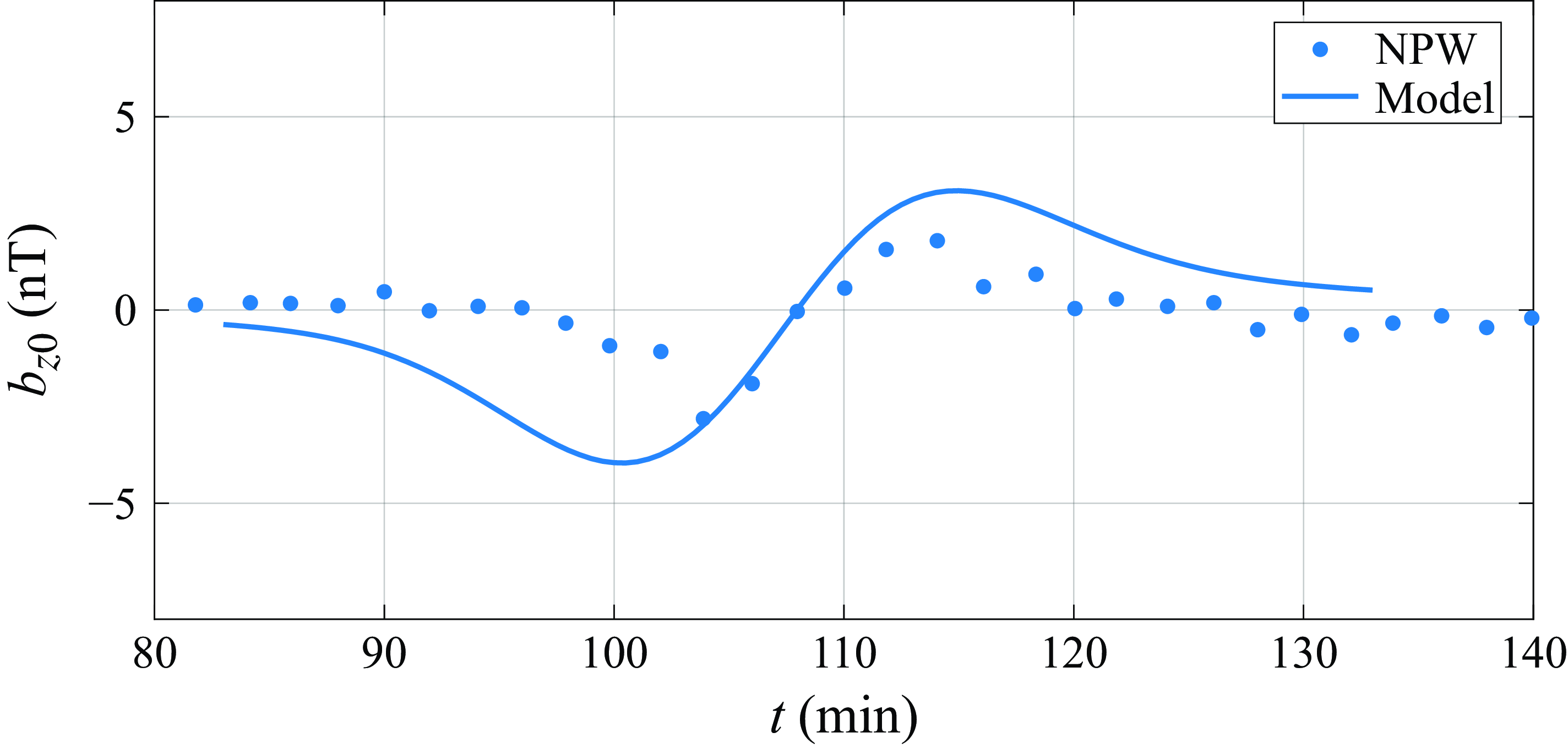

Figure 4. Comparison between the asymptotic vertical magnetic perturbation

![]() $b_{z_0}$

(3.12) and observations at the deep-ocean station NWP for the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku–oki tsunami. Model parameters are

$b_{z_0}$

(3.12) and observations at the deep-ocean station NWP for the 11 March 2011 Tōhoku–oki tsunami. Model parameters are

![]() $F=5\times 10^4\,\textrm{nT}$

,

$F=5\times 10^4\,\textrm{nT}$

,

![]() $F_z=-3.5\times 10^4\,\textrm{nT}$

and a representative deep-ocean conductivity

$F_z=-3.5\times 10^4\,\textrm{nT}$

and a representative deep-ocean conductivity

![]() $\sigma =2\,\textrm{S m}^{-1}$

(consistent with Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013). Observational data are digitised from Minami & Toh (Reference Minami and Toh2013). The model captures the correct polarity and timing of the signal, with amplitudes of the correct order.

$\sigma =2\,\textrm{S m}^{-1}$

(consistent with Wang & Liu Reference Wang and Liu2013). Observational data are digitised from Minami & Toh (Reference Minami and Toh2013). The model captures the correct polarity and timing of the signal, with amplitudes of the correct order.

Figure 4 compares the predicted vertical magnetic perturbation

![]() $b_{z_0}$

at the deep-ocean station NWP with the corresponding observations. While an effective depth is used to represent basin-scale tsunami propagation, the magnetic amplitude depends on the local water depth at the station; for this comparison, the local NWP depth (

$b_{z_0}$