Introduction

Honesty, defined as truth-telling and rule obedience (Rose-Ackerman, Reference Rose-Ackerman2001, 526; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Christensen and Pandey2013), is a long-standing desirable characteristic of public servants and carries implications for the quality of governance, economic growth and public trust. Normatively, the ideal of public sector honesty can be found across time and cultures, from Confucian administrative ethics of the 6th century BCE (Frederickson, Reference Frederickson2002), Plato’s 5th century prescriptions of Athenian public officials (Plato, The Republic), to more recent scholars (Wilson, Reference Wilson1918; Weber, Reference Weber1978; Hegel, Reference Hegel2015). (Dis)Honesty norms of public officials are conceptually and empirically linked to corruption (Rose-Ackerman, Reference Rose-Ackerman2001; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022), defined as deviant behavior involving the self-interested abuse of governmental power by public officeholders (Shleifer and Vishny, Reference Shleifer and Vishny1993; Gardiner, Reference Gardiner2017). Corruption impedes economic growth (Mauro, Reference Mauro1995; Gründler and Potrafke, Reference Gründler and Potrafke2019), imposes excess costs on government programs and on firms’ operations, thus diminishing their efficiency, and corrupt practices such as bribe weaken the rule of law by reducing the marginal cost of violations (Olken and Pande, Reference Olken and Pande2012). Honest behavior of bureaucrats is also important for maintaining quality of governance, by sustaining the level of public trust in institutions (Seligson, Reference Seligson2002; Anderson and Tverdova, Reference Anderson and Tverdova2003; Chang and Chu, Reference Chang and Chu2006) and lowering costly monitoring and sanctioning procedures (Miller, Reference Miller2005). However, despite the importance of honesty in the public sector, we know little about the causal effect of public sector culture on honest behavior.

Identifying the effects of public sector culture on honesty involves several challenges. A simple comparison of moral behavior among public and private sector employees can be misleading. Varying levels of honesty may be associated with selection into (out of) the public sector (see: Hanna and Wang, Reference Hanna and Wang2017; Barfort et al., Reference Barfort, Harmon, Hjorth and Olsen2019), thus conflating cultural and selection effects. Furthermore, public and private sector employees may vary along numerous unobservable dimensions, some of which may affect moral behavior. Failing to account for such dimensions could result in spurious correlations.

To overcome these challenges, we estimate the causal effect of priming public sector identity on the honest behavior of public employees. We take advantage of the relationship between culture and identity (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014), and the possibility to selectively prime identity. Contemporary theories of social identity in psychology and economics (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1970; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004; Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2010) posit that individuals hold multiple social identities, based on socially significant categories such as gender, religiosity, ethnicity or profession. Each of these identities is associated with specific social norms prescribing permissible behaviors. The relative weight an individual attributes to an identity determines which identity and associated norms are behaviorally relevant, and thus elicited (Shih et al., Reference Shih, Pittinsky and Ambady1999; Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Choi and Strickland2010; LeBoeuf et al., Reference LeBoeuf, Shafir and Bayuk2010). If the public sector favors particular values, it should be possible to trigger the expression of such values in public sector employees by rendering their public sector identity salient.

Studies in social sciences have made use of priming as a methodological tool to temporarily activate the salience of various identities, for the purpose of causally identifying the effects of these identities on a range of behaviors and attitudes (e.g., Transue, Reference Transue2007; Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014; Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Choi and Fisher2016; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018). Such methods enable researchers to randomly treat the salience of these identities, thereby overcoming the challenges that observational studies present. The assumption within all of these studies is that the short-lived effect of priming an identity is indicative of its long-term effect.

To test this expectation, we developed an instrument to prime public sector identity and validated this instrument among public employees in Germany and Israel. Next, we utilized the priming instrument to test the causal effect of public sector culture on unethical behavior among public employees. Following random assignment to the identity prime or a control condition, online versions of the ‘dice in mind’ game (Jiang, Reference Jiang2013; Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hjorth, Harmon and Barfort2019a) or the collaborative cheating game (Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015) are used to measure individual and collaborative honesty. While the effect of public sector culture on behavior is at the center of the design, we also investigate in a subordinate step whether priming public sector culture has consequences for self-reported values. For this purpose, respondents reported their Public Service Motivation (PSM) ‘understood as an individual’s predisposition to respond to motives grounded primarily or uniquely in public institutions and organizations’ (Perry and Wise, Reference Perry and Wise1990, 368), after the behavioral task. The dice-in-mind experiment was conducted on public employee samples in four countries: Israel (Study 1), Germany (Study 2), Sweden (Study 3), and Italy (Study 4). The collaborative cheating task has been conducted on a sample of public employees in the UK (Study 5).

This study contributes to existing research on honesty in the public sector in five main ways: First, we provide a priming instrument enabling researchers to experimentally increase the salience of public sector employees’ professional identity, to address a wide range of behavioral questions in public administration. Second, using two behavioral cheating measures, we apply the priming instrument to estimate the causal effect of public sector culture on individual and collaborative honesty. Third, conducting preregistered experiments in five countries with more than 2,500 public employees provides robust evidence that priming public employees’ public sector identity does not increase honest behavior. Fourth, there is equally robust evidence that priming public employees’ public sector identity increases self-reported PSM. Fifth, in policy terms, these findings suggest that public sector culture should not be relied upon as a safeguard against corruption. Instead, it highlights the importance of alternative mechanisms, such as robust institutional measures like monitoring, audits, and meritocratic recruitment, to maintain honest behavior among public employees.

Theoretical framework

Mechanisms that determine public sector honesty

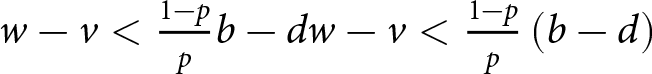

A useful starting point for reviewing the theory and findings about corruption and honesty in the public sector is the Becker–Stigler model (Becker and Stigler, Reference Becker and Stigler1974; Olken and Pande, Reference Olken and Pande2012; Rose-Ackerman, Reference Rose-Ackerman2013) that specifies the extrinsic and intrinsic motivations (Frey and Jegen, Reference Frey and Jegen2001; Yair et al., Reference Yair, Sulitzeanu-Kenan and Dotan2020; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022) that underlie corruption:  $w - v \lt \frac{{1 - p}}{p}b - dw - v \lt \frac{{1 - p}}{p}\left( {b - d} \right)$. The model suggests that an officeholder will engage in corruption as long as the earnings loss if caught (

$w - v \lt \frac{{1 - p}}{p}b - dw - v \lt \frac{{1 - p}}{p}\left( {b - d} \right)$. The model suggests that an officeholder will engage in corruption as long as the earnings loss if caught (![]() $w - v$) is lower than the expected utility from corruption (

$w - v$) is lower than the expected utility from corruption ( $\frac{{1 - p}}{p}b$) from which the ‘cost of dishonesty’ (

$\frac{{1 - p}}{p}b$) from which the ‘cost of dishonesty’ (![]() $d$) is deducted. The latter element pertains to an intrinsic motivation to act honestly, or rather the importance of honesty norms for the officeholder, whereas the former elements makeup the incentive structure that shapes one’s extrinsic motivation. In line with the Becker–Stigler model, the honesty of both prospective and actual public sector workers – assessed by behavioral measures in the lab and in the field – was found to be negatively associated with corruption levels across countries (Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hjorth, Harmon and Barfort2019b; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022). While much research on determinants of corruption concentrates on extrinsic motivations by exploring the implications of various incentive structures (Olken and Pande, Reference Olken and Pande2012, 496–99; Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Borges, Makarin, Mannah-Blankson, Nickow and Zhang2018), this research focuses on the role of honesty norms among public sector workers, and more specifically, the extent to which public sector culture promotes such norms.

$d$) is deducted. The latter element pertains to an intrinsic motivation to act honestly, or rather the importance of honesty norms for the officeholder, whereas the former elements makeup the incentive structure that shapes one’s extrinsic motivation. In line with the Becker–Stigler model, the honesty of both prospective and actual public sector workers – assessed by behavioral measures in the lab and in the field – was found to be negatively associated with corruption levels across countries (Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hjorth, Harmon and Barfort2019b; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022). While much research on determinants of corruption concentrates on extrinsic motivations by exploring the implications of various incentive structures (Olken and Pande, Reference Olken and Pande2012, 496–99; Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Borges, Makarin, Mannah-Blankson, Nickow and Zhang2018), this research focuses on the role of honesty norms among public sector workers, and more specifically, the extent to which public sector culture promotes such norms.

The existing literature identifies three potential processes that determine the honesty norm of public sector workers. First, given that bureaucrats are members of their society, they learn and internalize a set of ideas, attitudes, beliefs, and norms defined as their social culture (North, Reference North1991; Guiso et al., Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2015; Simpser, Reference Simpser2020). Cross-cultural differences in honesty norms have been found to predict the honest behavior of public officials’ honest behavior and corruption levels (Fisman and Miguel, Reference Fisman and Miguel2007; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022).

The two other processes that shape the honesty norm of public sector workers point to the fact that members of a particular organization within a given society may share a unique set of values as a result of selection, socialization, or both (Arieli et al., Reference Arieli, Sagiv and Roccas2020, 257). Olken and Pande (Reference Olken and Pande2012, 496) theoretically posited honesty-based selection into the public sector, and subsequent studies have shown evidence for such selection in both direction. Individuals seeking public sector employment in India, exhibited less honesty, gauged by cheating rates in a ‘corruption game’ and a dice-roll game, compared to those seeking private sector jobs (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Baul and Rosenblat2015; Hanna and Wang, Reference Hanna and Wang2017). Conversely, similar studies in Denmark, Germany and Russia found that students seeking to join the public-sector were more honest than those seeking private sector employment (Tepe, Reference Tepe2016; Tepe and Vanhuysse, Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2017; Barfort et al., Reference Barfort, Harmon, Hjorth and Olsen2019; Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Kalgin, Klimenko, Vorobyev and Yakovlev2021). While some studies claim that this honesty-based selection accounts for the level of corruption (Barfort et al., Reference Barfort, Harmon, Hjorth and Olsen2019), others contend that it is the existing level of corruption that shapes the direction of honesty-based selection (Olken and Pande, Reference Olken and Pande2012; Brassiolo et al., Reference Brassiolo, Estrada, Fajardo and Vargas2021). Either way, these studies show that honesty norms in the public sector may very likely be affected by honesty-based selection (Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022, 321).

A third process that potentially shapes the public sector honesty norm, and the focus of this study, stems from the culture of the public sector. Public sector culture refers to the set of social norms and values adopted or internalized by people working in the public sector, constituting part of their professional identity. Traditional conceptions of public sector culture suggest that it involves a relative emphasis on the value-set of honesty and fairness and the value-set of security and resilience, compared to the private sector’s typical emphasis on economy and effectiveness (Hood, Reference Hood1991; Schwartz and Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Reference Schwartz and Sulitzeanu-Kenan2004). Public sector culture is related to public sector motivation (PSM), that can be defined as ‘the beliefs, values and attitudes that go beyond self-interest and organizational interest, that concern the interest of a larger political entity and that motivate individuals to act accordingly whenever appropriate’ (Vandenabeele, Reference Vandenabeele2007). Thus, while PSM should not be conflated with public sector culture, norms and values that are arguably inherent to the culture of the public sector and the professional identity of its members are assumed to be a key source of motivation for many employees. Membership in the public sector is associated with a higher prosocial orientation (Vandenabeele, Reference Vandenabeele2008; Coursey et al., Reference Coursey, Brudney, Littlepage and Perry2011), altruism (Brewer, Reference Brewer2003; Dur and Zoutenbier, Reference Dur and Zoutenbier2015), and the likelihood of volunteering for a charity (Holt, Reference Holt2020) or donating blood (Houston, Reference Houston2006). Relying on these findings, it is plausible to hypothesize that a unique public sector culture exists and that it may place a premium on honest behavior.

Public sector culture and honest behavior

Public-sector institutions may promote a unique public sector culture (i.e., a set of norms and informal rules), which can either emphasize or understate the honesty norm, causing the level of honest behavior among its workers to deviate from that of the general society. For example, if the public sector culture places a premium on high ethical standards, we can expect that such considerations would affect recruitment, training, monitoring and promotion processes. Inversely, if the public sector culture envisages the role of the public sector as a facilitator of rent extraction and a vehicle for obtaining corrupt rewards for its members, it will motivate similar processes, in this case, promoting less-honest entrants, and socialization of cooperative values that facilitate continued corruption (see Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015). Thus, public sector culture is expected to affect public sector honesty.

Studies focusing on PSM similarly theorized that higher levels of PSM are associated with ethical behavior. It should be noted, however, that evidence on this relationship is mixed. Some studies reported a positive association between PSM and intentions to act in an honest and ethical manner (Brewer and Selden, Reference Brewer and Selden1998; Wright et al., Reference Wright, Hassan and Park2016), yet evidence regarding the relationship between PSM and actual ethical behavior is less consistent (Christensen and Wright, Reference Christensen and Wright2018; Meyer-Sahling et al., Reference Meyer-Sahling, Mikkelsen and Schuster2019; Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hjorth, Harmon and Barfort2019a; Schott and Bouwman, Reference Schott and Bouwman2024).

Identifying the causal effect of public sector culture on honesty is methodologically challenging. Naïve cross-sector comparisons may confound cultural effects with honesty-based selection into and out of the public sector. Public and private sector employees may also vary in numerous unobservable dimensions, some of which may affect moral behavior. Failing to account for these dimensions could result in omitted variable bias. The third key challenge in estimating the causal effect of public sector culture on honesty relates to measurement validity. Public sector employees may report specific social norms and values merely due to social desirability pressure. Moreover, even if public sector culture is characterized by the stated norms and values that prioritize honest behavior, these norms do not necessarily translate into honest behavior. For example, the norm of pro-sociality should not be equated with honesty, as it is not uncommon that prosocial motives are used to justify dishonest conduct (Zamir and Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Reference Zamir and Sulitzeanu-Kenan2018).

To overcome the challenges of omitted variable bias, including selection (Heckman, Reference Heckman1979), we leverage the relationship between culture and identity, and the possibility of randomly priming the latter (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014). Theories of social identity in psychology and economics (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1970; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004; Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2010) posit that individuals possess multiple social identities based on socially significant categories such as gender, religiosity, ethnicity or profession. Each of these identities is associated with specific social norms that prioritize and prescribe certain behaviors. The relative weight an individual ascribes to an identity determines which associated norms are behaviorally relevant, and thus eliciting norm-conforming behavior (Shih et al., Reference Shih, Pittinsky and Ambady1999; Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Choi and Strickland2010; LeBoeuf et al., Reference LeBoeuf, Shafir and Bayuk2010). This theory has been utilized to devise methods of priming particular social identities, in order to identify their causal effects (Cohn and André Maréchal, Reference Cohn and André Maréchal2016). While priming effects are typically temporary, the fact that temporary priming does shift preferences and behaviors confirms that identity exerts a causal effect on decision-making (Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Choi and Strickland2010; LeBoeuf et al., Reference LeBoeuf, Shafir and Bayuk2010). It has already been successfully used to prime national (Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018), ethnic (Transue, Reference Transue2007), religious (Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Choi and Fisher2016), partisan (Margolis, Reference Margolis2018) and professional identities (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014), as well as the identity of criminals (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, André Maréchal and Noll2015). Thus, randomly assigning public sector workers to such treatment (versus control) can be used to identify the effect of public sector culture on honest behavior.

The effect of public sector culture on individual and collaborative honesty

Drawing on this established theoretical framework, we expect that when the public sector identity of public servants becomes more salient, they become less likely to engage in dishonest behavior. Thus, our baseline hypothesis is:

H1: Priming public sector identity will decrease individual dishonest behavior.

The second hypothesis relaxes the assumption that public sector culture promotes honesty in general, and posits that the role of honesty norms in public sector culture may vary across countries and, consequently, so does the effect of priming public sector identity on honest behavior. Testing this hypothesis requires case selection that is based on the relative importance of the honesty norm among public sector workers. A useful measure of this country-level attribute is the observed relative public sector honesty – the difference in honest behavior between public and private sector workers (Tsuruta et al., Reference Tsuruta, Ojima, Hayashi and Morikawa2021; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022). These studies, indicate that public sector workers in some countries act more honestly than their private sector counterparts, while public sector workers in other countries, act less honestly than private sector employees (in the remaining countries no significant sector difference is found).

We therefore hypothesize that priming public sector identity of public sector workers in a country characterized by an observed positive relative public sector honesty will decrease individual dishonest behavior (H2a)Footnote 1; whereas priming the public sector identity of public sector workers in a country with an observed positive relative public sector honesty will cause them to increase their dishonest behavior (H2b).Footnote 2

Third, dishonest behavior is not necessarily a solitary act; instead, there are multiple cases in which unethical behavior necessitates cooperation. Examples of such collaborative settings include bureaucrats and business leaders working together to secure government contracts at taxpayers’ expense. Hence, public sector workers’ decisions, whether to act honestly or to violate rules, often occur in collaborative settings, which tend to increase dishonest behavior compared to individual tasks (Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015; Leib et al., Reference Leib, Köbis, Soraperra, Weisel and Shalvi2021). The collaborative cheating game (Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015) captures this often neglected aspect of corruption. Multiple studies that have applied the collaborative cheating game suggest, for example, that collaborative cheating is contagious (Gross et al., Reference Gross, Leib, Offerman and Shalvi2018; Kocher et al., Reference Kocher, Schudy and Spantig2018), that it increases with communication (Tønnesen et al., Reference Tønnesen, Elbæk, Pfattheicher and Mitkidis2024) and with feelings of similarity among group members (Irlenbusch et al., Reference Irlenbusch, Mussweiler, Saxler, Shalvi and Weiss2020). Going beyond H1, which addresses the effect of public sector identity on individual honest behavior, to assess its effect on collaborative (dis)honesty, we hypothesize that priming public sector identity will decrease collaborative dishonest behavior (H3). Finally, we account for whether public sector culture affects public employees’ self-reported values. In this context, PSM is a reported measure of the intensity of a value-set.

Research design

Experimental procedures

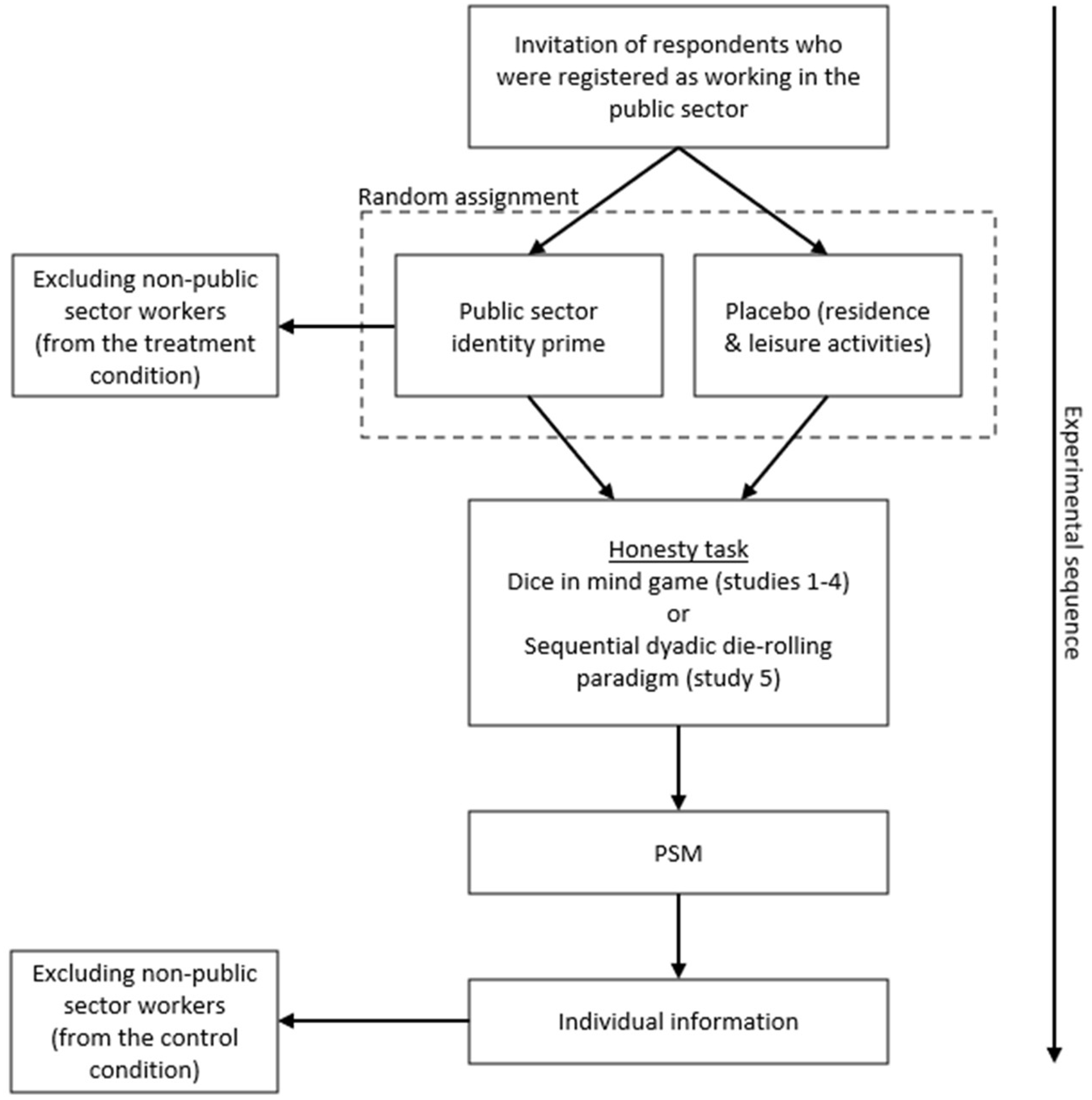

The three hypotheses were tested in five preregistered and ethically approved experiments.Footnote 3 All data and analyses are publicly available.Footnote 4 The general experimental design is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the experimental design.

In each of the five countries we contracted survey companies that operated large opt-in panels of registered respondents (Germany, Sweden and Italy: YouGov; Israel: iPanel; UK: Prolific). Only respondents who were registered with their respective survey company as working in the public sector were invited to participate. Respondents assigned to the treatment condition were asked about the sector of work (see Supplementary Table 1) as part of the treatment, and this question was also used to exclude non-public sector workers. Respondents assigned to the control condition received this question at the end of the experiment, as part of the ‘Individual information’ battery (see Figure 1), and it was similarly used to exclude non-public sector workers from the control condition. This selection process therefore requires that a respondent be both registered with the survey company as a public sector worker and self-report working in the public sector at the time of the experiment.

Subjects were randomly assigned to receive a public sector culture prime or a placebo. The public sector prime was pretested in two pilot studies to verify their effective treatments of the independent variable of interest (Mutz and Pemantle, Reference Mutz and Pemantle2015) – namely, the salience of public sector identity, measured by a word-completion task (see Supplementary Section A for details). The effectiveness of the public sector prime is comparable and slightly stronger than the average effect of four other identity primes (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014, Reference Cohn, André Maréchal and Noll2015; Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Choi and Fisher2016; Levendusky, Reference Levendusky2018). Notably, two of these primes successfully affected (dis)honesty among bankers (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014) and prisoners (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, André Maréchal and Noll2015), specifically increasing dishonesty in both cases.

After completing the priming task, subjects in Study 1–4 played a sequential mind game (Jiang, Reference Jiang2013). Subjects in Study 5 played an online version of the sequential dyadic die-rolling paradigm (Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015). After completing these honesty tasks, respondents completed a 5-item battery that measures PSM (see Methods and Supplementary section B for details). The wording of the 5-item PSM scale (Wright et al., Reference Wright, Christensen and Pandey2013) is provided in Supplementary Section B. While other recent studies used a lengthier, 16-items PSM scale (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Vandenabeele and Wright2013), it includes a direct question about honesty (the ‘to act ethically is essential for public servants’ item), which we wanted to avoid. Thus, we opted for an alternative validated PSM scale that is less overtly related to our dependent variable. The 5-item PSM scale is reasonably reliable with an overall α = .73 (Italy: α = .753; Sweden: α = .737; Germany: α = .673; Israel: α = .735; UK: α = .728). It was scaled to vary between 0 and 1, with higher values denoting greater public-service motivation. Measuring PSM after treatment assignment and completion of the honesty tasks serves several purposes. First, since many studies show that public sector workers score higher on PSM values, it provides an indirect manipulation check (beyond the two pilots). If the treatment is successful, we should expect a positive effect on PSM score. Second, a treatment effect on PSM, measured after the honesty task, allays concerns regarding the (in)effectiveness of the treatment due to inattentiveness or pre-treatment (Kane and Barabas, Reference Kane and Barabas2019; Kane, Reference Kane2025).

Measuring individual honesty

Participants in Study 1–4 took part in an online adaptation of the ‘mind game’ (Jiang, Reference Jiang2013; see also: Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hjorth, Harmon and Barfort2019b), used to measure individual-level (dis)honesty. This game involves asking participants to make a private prediction (guess) regarding a future die roll. They are not required to express that prediction but only to confirm (by pressing a button) that they have made one. Then, the dice roll result appears on the screen, and the participant reports their prediction. If the prediction matches the actual result, the participant receives a payoff; otherwise, they receive nothing. Given the monetary incentive to report a prediction that matches the outcome, respondents in such games tend to cheat. Moreover, since true predictions are reliably unobservable, mind game paradigms tend to elicit relatively higher cheating rates compared to other behavioral honesty measures (Gerlach et al., Reference Gerlach, Teodorescu and Hertwig2019). Under perfect honesty, a player is expected to correctly ‘guess’ one out of six results; however, previous studies have shown that people often report successful ‘predictions’ at much higher rates (Abeler et al., Reference Abeler, Nosenzo and Raymond2019; Gerlach et al., Reference Gerlach, Teodorescu and Hertwig2019). Importantly, this paradigm has been shown to correlate with real-world dishonest behaviors (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, André Maréchal and Noll2015; Hanna and Wang, Reference Hanna and Wang2017).

In experiments reported here, each subject played 12 consecutive rounds of the mind game and received 1€ (or an equivalent sum in the local currency) for each correct guess. Dishonest behavior was measured by each participant’s total number of reported successful guesses. This paradigm enables us to detect individual cheating at the aggregate level, based on the size of the deviation between the expected rate of successful guesses under perfect honesty (two in this experiment) and the group mean (reported) rate of success. The mean number of successful guesses in all of the experiments was greater than two (see Supplementary Figure 5 for details).

Measuring collaborative honesty

For the purpose of measuring honest behavior in collaborative settings (Study 5), we designed an online adaptation of the sequential dyadic die-rolling paradigm (Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015), programmed in oTree (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Schonger and Wickens2016).Footnote 5 Collaborative cheating is a form of cheating in which two or more individuals must work together to gain an unfair advantage. This interdependence reflects the inherently collaborative nature of corruption, highlighting that it is not necessarily a solitary act but sometimes necessitates collusion between parties. Respondents are assigned into dyads and play an online version of the sequential dyadic die-rolling paradigm (Weisel and Shalvi, Reference Weisel and Shalvi2015), with monetary rewards. Each dyad consists of two roles: X and Y. Players are randomly assigned to these roles at the start of the experiment and play all the rounds in this role within their assigned dyad. The game proceeds in three steps: (1) Player X privately rolls a dice and reports the result on the computer. As participants may not have an actual dice, the instructions include links to a set of publicly available virtual dice rolls. (2) Player Y is informed about the number reported by Player X. Player Y then privately rolls a dice and also reports the result on the computer. (3) The two players are informed about the reported numbers and their payoff. The payoff for each player depends on both reported numbers. The payoff is 0£ (GBP) if the two reported numbers differ. If the two reported numbers are equal (‘double’), the payoff for each player equals the number they both reported in GBP, i.e., higher doubles lead to a higher reward. This sequential interaction is repeated 15 times. After round 15, respondents answer a post-experimental survey, and at the end of the survey respondents are paid in GBP a payoff based on one randomly selected round, in addition to a fixed show-up fee (2£). The key dependent variables measuring cheating is the number of reported ‘doubles’ and the average reported value of the dice rolls.

Data collection and samples

Using survey companies in all five countries, we recruited a total of 2,827 public sector employees (descriptive statistics are provided in Supplementary Table 5). Participants were randomly assigned to either an identity treatment condition – which increased the salience of their public sector identity – or a control condition. The random assignment ensures that subjects in the two conditions are statistically balanced in both observable and unobservable characteristics, thus addressing the inferential challenges that stem from selection and spurious correlation.

The treatment condition in all five experiments included a public sector prime, pretested in two pilot studies (see Supplementary Section A for details). This prime included a set of open-ended questions regarding respondents’ work experience in the public sector. Respondents in the control condition were asked a set of questions about their place of residence and preferred leisure activities (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). Following this stage, participants took part in an online adaptation of the ‘mind game’ (Studies 1–4) or the sequential dyadic die-rolling paradigm (Study 5).

Treatment randomization in studies 1–4 was assessed by utilizing logit models to estimate the experimental condition (treatment/control) based on a set of seven individual-level attributes (Supplementary Table 6).Footnote 6 In three of the countries, these analyses show no predictive power (insignificant LR χ2 tests); however, in the Italian experiment, the number of years in the public sector was positively associated with being assigned to the treatment condition (b = 0.004, p = 0.019). While it is likely to get such an association by chance within 28 comparisons (4 × 7 = 28), the treatment effects in Italy were re-estimated, controlling for this attribute, and no substantive differences in treatment effects were found. Treatment randomization in Study 5 was similarly assessed, based on a set of five individual-level attributes (Supplementary Table 7). This analysis shows no indication of a systematic relationship between these attributes and the experimental condition.

Studies 1 and 2, conducted simultaneously in Germany (n = 436) and Israel (n = 414) in 2019, examine whether priming public sector identity increases honest behavior (H1). In both of these countries, no significant sector differences in honest behavior were found by Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al. (Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022). Swedish public employees were found to be more honest than private sector employees, whereas in Italy, the opposite has been observed (Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022). Studies 3 and 4, conducted in Sweden (n = 609) and Italy (n = 604) in 2022, tested whether the effect of public sector culture increases honest behavior in countries that emphasize honesty in the public sector (H2a), and decrease honest behavior where honesty is relatively de-emphasized (H2b), respectively. Study 5, conducted among 382 dyads of public sector workers (n = 764) in the UK in 2022, examine whether priming public sector identity increases honest behavior in collaborative settings (H3). The UK is among the countries where public sector workers were found to act more honestly than their private sector counterparts (Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022).

Results

Effect of public sector culture on individual honesty (studies 1–4)

As preregistered, the effects of priming public sector identity on honest behavior and PSM were estimated using randomization inference (permutation) tests. This method involves computing the distribution of the test statistic under random permutations of the sample units’ assignments to the treatment and control conditions. The effect in each study was estimated through 10,000 re-randomizations using the ‘ritest’ command in Stata (Heß Reference Heß2017). The main result of interest is the likelihood of obtaining a treatment effect on the number of reported successful guesses that is equal to or larger than the original effect found.

The estimated effects of priming public sector identity on individual dishonest behavior (number of correct guesses) are small and statistically insignificant in all four countries (Studies 1–4). These findings do not support hypotheses H1, H2a and H2b, i.e., we find no support for the proposition that public sector culture increases honest behavior, nor that it variably influences honest behavior depending on the country-level of relative public honesty and corruption. Priming public sector identity positively affected PSM levels in all four studies, but this effect was not statistically significant in the German study (p = 0.328). Overall, these results support the validity and efficacy of our manipulation. The results of these analyses are presented in full tabulated form in Supplementary table 8.

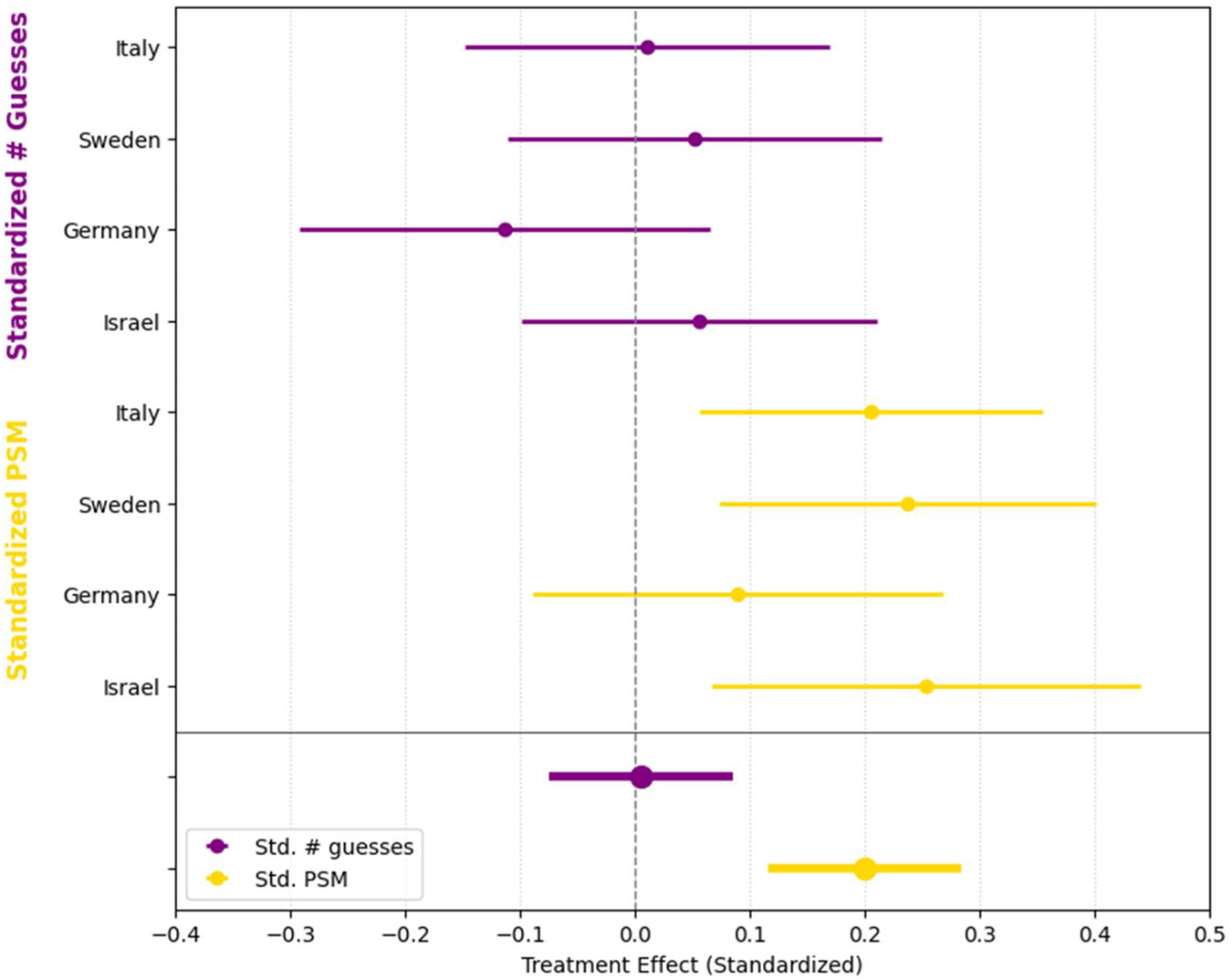

To present the results of Studies 1–4 jointly, the number of correct guesses and PSM scores were converted to standardized scales (Mean = 0, SD = 1), and OLS regressions were used to estimate the treatment effect on these standardized measures for each of the four countries, as well as for the joint dataset, controlling for country-fixed effects. Figure 2 graphically presents these results (full tabulated results are provided in Supplementary Table 9), showing that the joint treatment effect on honest behavior (number of successful guesses) is negligible (Cohen’s d = 0.005) and statistically insignificant while the effect on PSM is positive (Cohen’s d = 0.200) and statistically significant.

Figure 2. The effects of priming public sector identity on standardized no. Of successful guesses and standardized PSM across four countries (studies 1–4). Error bars represent 95% CIs. Bottom thick estimates represent the overall pooled treatment effects on standardized no. Of successful guesses and PSM, controlling for country-fixed effects, with 95% CIs.

Priming experiments often raise the question of whether the treatment effect indeed operates solely through the intended mechanism (Cohn and André Maréchal, Reference Cohn and André Maréchal2016; Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Mandel and Rinott2025). The results of the pilot studies show that our treatment affects the salience of the public sector and this is also supported by the effect on PSM. However, it is possible that priming public sector identity may have also activated other concepts. Specifically, while thinking about their sector affiliation, respondents may also be reminded that they earn less compared to members of the private sector and relative financial standing may likewise influence honest behavior.

To address this concern, we take advantage of a post-treatment question about respondents’ level of private expenditure relative to the average level in each country that was included in the studies in Sweden and Italy. We use this measure to assess the effect of the treatment on perceived relative financial standing by comparing the distribution of responses between the treatment and control conditions. No significant difference was found in the distribution of responses in either country sample (Italy: Pearson χ2 = 0.787, p = 0.978, N = 606; Sweden: Pearson χ2 = 3.978, p = 0.553, N = 611), nor in the pooled sample (Pearson χ2 = 1.959, p = 0.855, N = 1217). Supplementary Figure 11 shows these distributions graphically. This analysis allows us to allay the concern that the treatment effect influenced honesty through respondents’ perceived relative financial standing.

Given the null effect of priming public sector identity on honest behavior, we went beyond our preregistered analysis and conducted an equivalence test to reject the null hypothesis of a meaningful effect. Given that we did not preregister the value of the smallest effect size of interest (SESOI), we considered two alternative values. First, considering the potential to report up to 12 successful guesses, whereas the expected number under perfect honesty is 2 and the actual mean number in the pooled sample is 5.97, 0.5 guesses is subjectively considered a reasonable SESOI. Alternatively, a recent, large-scale study of honest behavior used a SESOI of Cohen’s d = .075, which in our data represents 0.2622 guesses (Zickfeld et al., Reference Zickfeld, Ścigała and Elbæk2024). The latter value was used for SESOI because it was set independently of this research and provides a more stringent test of equivalence. Using two one-sided tests (TOST), we can reject the presence of a smallest effect size of interest (p = 0.047, p = 0.042), and the absence of a meaningful effect of priming public sector identity on individual public honesty can be declared. Assessment of heterogeneous treatment effects suggest that this null effect is also consistent across gender, age, work seniority and organization type (see Supplementary section C for details).

The effect of public sector culture on collaborative honesty (study 5)

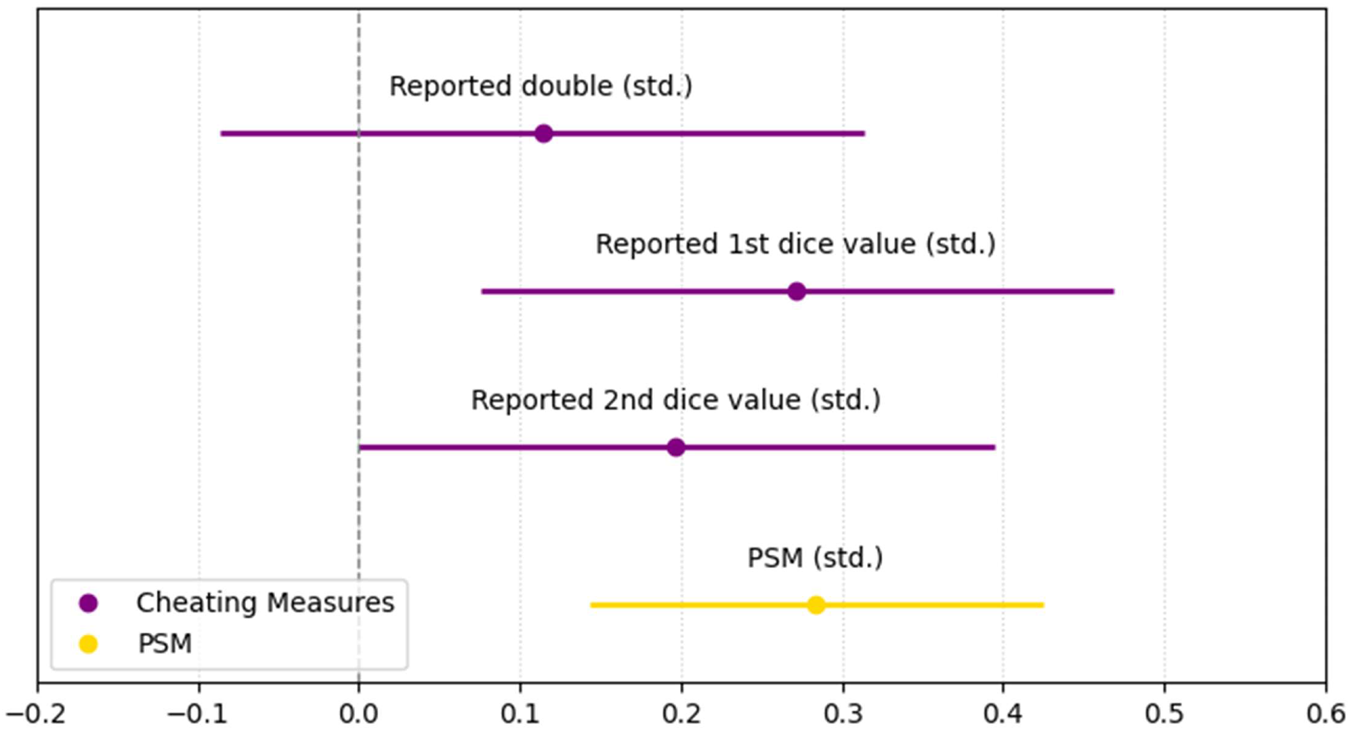

To test the hypothesis that priming public sector identity reduces collaborative cheating among public sector employees, this effect was estimated on the reported number of doubles and on the mean value of reported dice results in Study 5 using randomization inference (as pre-registered). Priming public sector identity, again, has a significant, positive effect on PSM (Cohen d = .284; p < 0.001). Regarding dishonest behavior, these analyses show no significant effect on the reported number of doubles; however, unexpectedly, significant and marginally significant, positive effects were found on the mean reported first and second dice values, respectively. The effect size on first dice values is d = 0.272 (p = 0.006) and the effect on second dice values is d = 0.197 (p = 0.047) (full tabulated results are reported in Supplementary Table 11).

To present the results of study 5 graphically, the three measures of honesty (no. of doubles, first and second dice values) and PSM were converted to standardized scales (Mean = 0, SD = 1), and OLS regressions were used to estimate the treatment effects for these standardized measures. These results are shown in Figure 3 (full tabulated results are in the Supplementary Table 12). In summary, a positive effect on PSM and mixed evidence for the effect of priming public sector identity on collaborative honest behavior were found. While no significant effect on the number of reported doubles was found, there are positive effects on cheating based on the reported dice value measures, though the statistical significance of one of these is marginal based on the planned, randomization inference. These findings do not support our hypothesis that priming public sector identity decreases collaborative cheating (H3).

Figure 3. The effects of priming public sector identity on standardized measures of collaborative cheating and PSM (study 5). The estimates represent the treatment effect on standardized number of reported doubles (top), on standardized reported value of first and second dice values (second and third from top, respectively), and on standardized PSM, with 95% CIs.

Discussion

Under the assumptions of social identity theory (Tajfel, Reference Tajfel1970; Tajfel and Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Hatch and Schultz2004; Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2010), the design of these incentivized experiments satisfies the conditions for an unbiased comparison between public sector workers who vary in the salience of their public sector identity, and thereby the norms associated with public sector culture. Experimental results show that making civil servants’ public sector identity salient has no causal effect on their individual honest behavior, as measured in four countries. There is also no support for a negative effect of priming public sector identity on collaborative dishonest behavior among public sector workers in a fifth study in the UK. Specifically, some measures of collaborative dishonesty (reported doubles) were unaffected, whereas others (reported dice values) indicated a positive effect on cheating. These findings offer no evidence to support the longstanding, empirical proposition that honesty is central to public sector culture, despite the normative attractiveness of this proposition. Moreover, these results do not support the proposition that variance in the role of honesty in different public sector cultures accounts for cross-country differences in the effect of public sector culture on honesty (Studies 3–4).

Previous studies provide evidence for cross-country differences in honesty (Gächter and Schulz, Reference Gächter and Schulz2016; Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, André Maréchal, Tannenbaum and Zünd2019) and that this society-level honesty strongly predicts the honesty of public sector workers and accounts for country-level variations in corruption (Sulitzeanu-Kenan et al., Reference Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Tepe and Yair2022). Beyond the effect of honesty in society, observational studies have shown that honesty-based self-selection may account for corruption levels in some cases (Banerjee et al., Reference Banerjee, Baul and Rosenblat2015; Tepe, Reference Tepe2016; Hanna and Wang, Reference Hanna and Wang2017; Tepe and Vanhuysse, Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2017; Barfort et al., Reference Barfort, Harmon, Hjorth and Olsen2019), although not in all (Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Kalgin, Klimenko, Vorobyev and Yakovlev2021). In this context, the lack of a public sector culture effect may emphasize the role of societal differences in accounting for corruption levels more than sector specific attributes. Regarding honesty-based selection, it is possible that its effect is short-lived as new workers socialize into public organizations (Kjeldsen and Bøtcher Jacobsen, Reference Kjeldsen and Bøtcher Jacobsen2013). Moreover, it is an open question whether honesty-based selection shapes public sector corruption levels (Barfort et al., Reference Barfort, Harmon, Hjorth and Olsen2019), or whether the norms associated with the public sector shape honesty-based selection patterns (Brassiolo et al., Reference Brassiolo, Estrada, Fajardo and Vargas2021). Even if selection does have a lasting effect on the honest behavior of public sector workers, these results do not provide evidence to support the notion that this process shapes the shared culture of the sector, at least to the extent that it has an independent effect on honest behavior.

Given the established role of organizational culture and socialization in shaping behavior (Cohn et al., Reference Cohn, Fehr and André Maréchal2014, Reference Cohn, André Maréchal and Noll2015; Arieli et al., Reference Arieli, Sagiv and Roccas2020), a plausible inference from the results of this research is that the public sector, as a category that encompasses diverse public organizations and professional groups, may simply be too varied to elicit a common culture, at least in the sense of entailing a shared emphasis on honesty. The public sector in most countries comprises a host of very different organizations (e.g., schools, hospitals, tax bureaus, police units) and professions within them (e.g., social workers, accountants, lawyers, fire-fighters), which may give rise to various organizational cultures. It is feasible that some organizational cultures within the public sector prioritize honesty while others do not, resulting in an aggregate sector null effect. Future research may consider more particular organizational cultures and identities of professions within the public sector (e.g., judges, accountants, street-level bureaucrats, etc.), and their potential influence on honest behavior.

Conclusions

A policy implication of the current research is that public sector culture should not be relied upon as a particularly strong safeguard against corruption. This conclusion highlights the relative importance of alternative mechanisms, such as robust institutional measures like monitoring, audits (Gans-Morse et al., Reference Gans-Morse, Borges, Makarin, Mannah-Blankson, Nickow and Zhang2018), and meritocratic recruitment (Dahlström et al., Reference Dahlström, Lapuente and Teorell2012).

The positive effect of priming public sector identity on PSM provides additional validation for the public sector identity treatment and contributes to the PSM literature. It is interesting that although priming public sector identity increases PSM, it does not affect honest behavior. Furthermore, there is no association between individual honest behavior and PSM in these data (controlling for experimental condition and country fixed effects) (see Supplementary Table 13 for details), nor between collaborative honest behavior and PSM (Supplementary Table 14). These results add to the mixed findings regarding this relationship in previous studies (Christensen and Wright, Reference Christensen and Wright2018; Meyer-Sahling et al., Reference Meyer-Sahling, Mikkelsen and Schuster2019; Olsen et al., Reference Olsen, Hjorth, Harmon and Barfort2019a; Schott and Bouwman, Reference Schott and Bouwman2024). They also highlight a more fundamental limitation of PSM as a self-report-based measure. Specifically, the notion of ‘ethical blindspot’ (Banaji and Greenwald, Reference Banaji and Greenwald2013) – the consistent finding that ethical violations often remain consciously unregistered due to effective rationalization mechanisms – may hinder the validity of PSM measures in the context of moral behavior, as people can deviate from consciously held values associated with the public service, while maintaining a conscious adherence to those values (Zamir and Sulitzeanu-Kenan, Reference Zamir and Sulitzeanu-Kenan2018).

Finally, demonstrating the possibility of priming public sector identity contributes to future research since identifying the behavioral effects of activating this identity is at the center of many research questions in behavioral public administration (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Jilke, Olsen and Tummers2017). While previous research relied on observational data (Tepe, Reference Tepe2016; Tepe and Vanhuysse, Reference Tepe and Vanhuysse2017), the priming instrument developed and used in this research allows for causal inferences about various potential effects of civil servants’ public sector identity. Moreover, in line with our suggestion that future research may consider more particular organizational cultures and identities, this priming instrument can be revised to address these specific identities to study their potential effects on honest behavior, as well as other behaviors and attitudes.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2026.10032

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor, Adam Oliver, two anonymous reviewers and participants of seminars at FGV Sao Paolo School of Public Administration, Haifa University, Hebrew University, Leuphana University, Reichman University, EGPA Conference 2024, Politics & Economics Workshop 2024, IRSPM Conference 2025. The Ministry of Science and Culture of Lower Saxony and the VolkswagenStiftung via the program ‘Niedersächsisches Vorab: Research cooperation Lower Saxony-Israel’ provided generous financial support.