Introduction

This is the understory to an overstory and retrospective in nature. We present a Canadian forest imaginary that chronicles how a forest led to exploring the phenomenon of mystery and how this served as the inspiration behind a novel philosophy of education featuring mystery [herein poetism] (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harveyforthcoming). Essentially, what follows is the back story to an extended writing project examining the phenomenon of mystery whose source of inspiration is the forest. The Critical Forest Studies (CFS) Collaborative is visionary in imagining this call inviting researchers to share their experiences with forests.

Our work is the culmination of an extended attunement with nature, nurtured and instilled in us by our forebearers (a grandfather and aunt) who valued nature beyond economic gain or benefit, impressing upon us its potential to enliven our imaginations. This work is a humble recognition of their lifetime influence and a thank you for the love they instilled in us for nature.

The setting for this inquiry is a forest that has been spared and cared for over the generations our family has lived by it, now going on six generations. In return, the forest has spared and cared for us during our short time living with it. In a spiritual and aesthetic sense, it provides daily wonder and awe, a sense of reverential mystery, all the while enlivening our imaginations. Psychologically and emotionally, it provides important respite from the day’s demands; physiologically, oxygen for us to breathe, and biologically, food for us to eat and fuel to keep us warm. Most importantly, the forest reminds us of our entangled relations with it. Collectively the forest connects us with the great chain of being. It reminds us through such metaphysics and cosmology that we are in relation with this forest. A relationship increasingly at risk. Our inquiry has been and continues to be set in this forest. Our inquiry and discoveries are specific to this place and this time.

Scientists and philosophers by academic training we have come to learn that our academic epistemologies significantly and fundamentally frame our understandings of the world. We tend to default to these in our everyday engagements with the natural world. We learn only to see the natural world in ways shaped by modern worldview. Such a worldview increasingly views nature through a scientific lens, all too commonly reduced to economics, efficiency, reserve, potential, capacity and profit. It is time to listen to our forebearers. It is time to learn how to see the forest differently.

With this in mind, we have two objectives and questions that circumscribe our work. Objectives include: (1) demonstrating how eco-phenomenology reveals our relational engagement with forests and inspires poetism, a novel philosophy of education founded on a doctrine of mystery (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harveyforthcoming) useful to teacher environmental education; and (2) demonstrating the unsettling and decolonising of Western settler views of a Canadian forest (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Tuck and McKenzie2016). While the former objective is explicit; the latter is more implicit assuming the following forms: (1) the acknowledgement of our Western-European privilege and the humility the Land Acknowledgement to the Ojibway of the Anishnnabekiing instils; and (2) the recognisition of Indigenous scholars whose work deeply resonates with ecological aesthetics, ethics, epistemology and ontology – common ground supporting our distinct yet overlapping ecological philosophies. We discover and appreciate a common project, concern and effort through Bang et al’s., (Reference Bang, Curley, Kessel, Marin, Suzukovich, Strack, McCoy, Tuck and McKenzie2016) recognition that:

Indigenous scholars have [too] focused much attention on relationship between land, epistemology and importantly ontology. Places produce and teach particular ways of thinking about and being in the world. (p. 44).

The following questions stem from these objectives:

-

• What are the ways a Canadian uplands deciduous forest provides creative ways of understanding and relating to the sentient forest?

-

• How do creative encounters with a sentient forest lead to more relational and caring imaginaries of human–forest relationships? (Rousell et al., Reference Rousell, Hill, Ryan, Harvey, Barns, Aleksic and Boadu2025).Footnote 1

Our Canadian forest imaginary begins in Part I: Canadian Uplands Deciduous Forest. We describe important historical and epistemological contexts setting the stage for our inquiry. Moving on to Part II: Understory – Overstory: A Canadian Forest Imaginary, we outline our eco-phenomenological method of inquiry, recognising our philosophical and theoretical influences. We then demonstrate eco-phenomenology through a series of shared lived experiences within our forest, interspersed with theoretical reflection. In contrast to a scientific episteme in Part I, this artistic episteme enlivens the imagination. Through eco-phenomenology three concepts are revealed – the sylvan fringe, the clearing and the care structure. How these translate into a philosophy of education nurturing an ethos of mystery for education theory and practice are considered. Here, the “roots” of poetism are interpreted through ontological, epistemology and axiological domains. Turning our attention to Part III: Critical Forest Studies and Teacher Environmental Education, we consider theoretical and programmatic features supporting CFS in teacher environmental education. The foundational work of Sauvé (Reference Sauvé2005) who provides a theoretical cartography of environmental education and Evan’s et al., (Reference Evans, Stevenson, Lasen, Ferreira and Davis2017) who offer programmatic models for environmental education are informative. Lastly Part IV: Summary, revisits our objectives and research questions and then considers our inquiry’s limitations and outstanding questions.

Part I: Canadian uplands deciduous forest

In what follows we provide a historical and epistemological context for our work. Reaching back into history requires we present this as factually as possible based on the evidence available. Epistemologically, we default naturally to a scientific episteme because of our academic background and training. Forest ecology as a scientific episteme tends to regard the forest as an object. In addition to establishing important context, this descriptive foray lays the groundwork, dialogically, for us to engage with forests in other ways; other realms of experience; other epistemes that enliven the imagination. Descriptive in character, this first part establishes important historical and epistemological context for the balance of our work.

Originating sometime during the last ice age (12,000–15,000 years ago) (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Beaudoin, David, Delcourt and Richard2025). this southern Ontario forest succeeded paleolithic peoples’ nomadic existence (Storck, Reference Storck2004). It is part of the territory belonging to their descendants, the Ojibway of the Anishnnabekiing who live and reside today on the Saugeen Ojibway Territory, transferred to the English Crown, as The 1836 Saugeen Treaty, No. 45 ½ (Environment Office Saugeen Ojibway Nation, 2025). Millennia ago, neolithic peoples occupied the region prior to this time as small nomadic tribes hunting, trading and re-creating. The re-greening of the lands as the glaciers retreated, ultimately culminating in mature deciduous forests, had a profound effect on post-glacial peoples who were largely nomadic – following roaming herds of caribou, elk, mammoth, buffalo. As we will discover these were the peoples whose lives changed most radically – from nomads to agrarians – as they experienced the forest, cleared small dwellings within its floors, learning how to cultivate its rich humus, remaining connected with the land, establishing places within the land, guarding and safekeeping the land. Cajete (Reference Cajete1996) comments the “diverse adaptations amongst Indigenous groups. . . took many forms: Living in the forests of the Northeast, Indians venerated the trees and integrated that reality of their environment into every aspect of their lives and expression as a people” (p. 136). These were truly the first peoples of North America who provided the template for living respectfully and caringly with the forest. Harrison (Reference Harrison1992) adds:

This transformation in the human mode of existence has, to be sure, brought many blessings to the race, but in the beginning the neolithic transformation amounted to a deep humiliation of the human species – a helpless surrender to the law of vegetation that had chocked the land with forests depriving the nomads of their prior freedom of mobility. Agriculture was a means of cultivating and controlling, or better domesticating, the law of vegetative profusion which marked the new climatic era (pp. 197–198).

Learning how to live with forests, modelled successfully by Indigenous peoples for millennia, became something successive migrations of non-Indigenous peoples undid (Bacher, Reference Bacher2011) through clearing the land of its forests and colonising its native peoples. The recent history of non-Indigenous people in North America demonstrates they excelled at this, however, this has not always been the case. Ancient non-Indigenous peoples (e.g., Celts, Vikings, Britons, Saxons, etc.) lived with forests too--in a world of enchantment (Harrison, Reference Harrison1992; Taylor, Reference Taylor2024). Similar to Indigenous peoples, their connection with the forest assumed cosmological significance (McCoy et al., Reference McCoy, Tuck and McKenzie2016). However, in more recent times, non-Indigenous people, largely have forgotten this sacred relationship with forests and must shoulder a disproportionate responsibility for re-enlivening it. Living the imaginative potential of the forest is one way to undo the dehumanising effects of colonisation, for all its peoples and more-than-human beings. On all levels – ontological, sociological, ecological and cosmological – re-enlivening the imaginative potential of the forest secures an ethical relationship with the world and earth. Our contribution to this call, is a small step toward this.

Today, our Footnote 2 forest comprises land now overlain by the modern cartographic designations (themselves, colonising) including the country of Canada, the province and region of southern Ontario, the county of Grey, slightly west of a town called Dundalk. Geographically and geologically, this forest is located at the central-western slope of a plateau, referred to as the Dundalk Plateau the highest elevation in southern Ontario created through either the culmination and accretion of several ice ages, shaped by thick ice sheets or the emergence of seawater (Karrow & White, Reference Karrow and White2002). Its limestone base ensures alkaline soils, clear artesian springs, good drainage, rich loam, cooler springs and warmer falls. At 1400 ft. above sea level (Ontario Topographic Map, 2025), our forest is elevated relative to other forests in southern Ontario because it grows on the western edge of the Dundalk Plateau along the southern shore of a late glacial river valley land. Lidar scans reveal a large cobblestone washout, millennia of debris from a retreating glacial riverway. Here, summer steals fall as winter borrows spring. This subtle yet definite shift of seasons may indicate climate change. Yet it is not uncommon to experience five months of winter. Today, a 15-acre parcel of mature deciduous upland forest saved and conserved by an earlier generation who saw fit to cordon off livestock with grazing mandibles from germinating seeds and reaching seedlings, remains largely untouched since 1947 – relative solitude for almost 80 years. Because it has remained in a family for six generations, it has resisted the common tendency that periodic turnovers in property (every 7–12 years) foretell – where sellers maximise the sale of their property by harvesting marketable timber prior to sale or purchasers do the same to offset their purchase prices (Elliott, Reference Elliott1998). Of course, there have been a few selective “cuts” of the forest at 15-year intervals to maintain diversity of species and age.Footnote 3 This was not for commercial or economic purposes but rather to increase the heterogeneity of the age and species of the forest’s trees, which from colonisation (1860s) to 1947 were mature enough to survive the common practice of allowing livestock (cattle, oxen, horse, sheep and pigs) to graze freely within its shadows, a routine practice up to that time when forests were less revered than they are now (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harvey2025). Unrestricted grazing impinges upon the forest’s understory robbing it of successive generations of trees (the understory) eroding the soil and disrupting the forest ecology. It is not uncommon to hear rural folk to this day, lament the forests for the toll they took on their ancestors’ (colonists’) lives – endless days of toil and back-breaking work during blackfly and mosquito infected springs and summers, navigating thigh-burning deep snow and bone-chilling cold winters, to access the forest, fell trees, uproot stumps and burn slash, just to create a clearing amidst the depth of the dark forest, at first, to build a crude shelter, and then in time a homestead and barn to grow and raise animals for sustenance. This recounting of earlier days “clearing the land” is frank:

Clearing the land was a laborious task. Large trees were chopped by axe, and the stumps had to be removed by hand if the pioneer was unfortunate enough not to own a horse or oxen. Only then could the pioneer begin the task of levelling the land and removing stones and sticks (Drimmie, Reference Drimmie and Cork1984, p. 95).Footnote 4

This was the way of the colonist who took up the invitation by their Queen (or King) to travel from Europe over to what became known as the Queen’s Bush.Footnote 5 The vast track of forested land covering much of southern Ontario, south from Waterloo County, north to Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, originally set aside for the protestant clergy (Pavlakos, Reference Pavlakos2021). Of significance many of the first pioneers of the Queen’s Bush were black settlers from the United States, fleeing persecution and slavery in the 1830s (Figure 1). At one time, 2000 black settlers lived in or around the Queen’s Bush, finding safe refuge through the underground railway portering slaves from south of the Mason–Dixon line in Massachusetts across to the British colony that became Canada some 47 years later.Footnote 6 However, many early black settlers could not afford the purchase of land offered up by the crown and left the area for larger urban centres (Pavlakos, Reference Pavlakos2021). Western Europeans came next – Scottish, English, Irish, French, British, Germany, Dutch – further displacing Canada’s First People’s. Many peoples have travelled through, lived, sought refuge and food/material, within our forest.

Figure 1. Southern Ontario’s early non-Indigenous African American peoples.

Our forest is a mature upland deciduous forest (Figure 2) in that it has a variety of hardwood species – sugar maple, black cherry, beech, ash, ironwood, basswood, walnut and a few remaining butternutFootnote 7 – at full and varied maturity (Elliott, Reference Elliott1998). There is a well-established “over-story” or canopy as it’s referred to, and several stages of under-story, generations of the forest to come. But in addition to the trees, there are varieties of early spring wildflowers (e.g., Coltsfoot, Blood Root, Trillium, Dog-Tooth Violet and Pink Lady Slippers) and some edible herbs, including wild ginger, garlic and leeks. The typography is well drained, the highest point on our land, with cobblestone and gravel beneath a rich and loamy topsoil. Bird life is rich, fluid and migrating. During the summer months we often hear the songs of many birds. Even during the winter, the calls of Chickadees, Pileated, Downy and Hairy Woodpeckers, and occasionally during a clear night Northern Great Horned Owls, Saw-wet Owls, Screech Owls and occasionally Barred Owls, pierce the air. Red-tailed Hawks, Bald Eagles, Peregrines and a variety of Kestrels find home in or around our forest during the spring, summer and fall months. Wild Turkey, re-introduced in the late 1980s, forage in crop land and roost in the boughs of the forest’s trees. Around dusk, any unexpected intruder will startle these birds precipitating a pterodactyl-like departure. Mammals, usually nocturnal, include deer, porcupine, racoon, skunk, opossum, coyote, fox, hare, mink and weasel, several species of squirrels and chipmunk. On rare occasions a black bear may travel through. Amphibians are less numerous but include many varieties of frog and toads. Spring Peepers and American Toads’ distinctive calls punctuate early and late spring evenings. Snakes, salamanders and newts commonly seek refuge along the forest floor. Insects are too numerous to list and over-represented by spring blackflies, several species of mosquitoes and flies, namely the deer fly. But hundreds of unknown insects undoubtedly live in the forest contributing invaluably to its ecosystem. As the dry and hot summers give way to fall, plentiful rain and cooler temperatures bring forth an abundance of fungi. A particularly large species, the Giant PuffballFootnote 8 can be found growing within the forest floor during the wet months of September and October.

Figure 2. Southern Ontario uplands deciduous forest.

Our historical and ecological description of “our” forest has established important context and set the stage for the dialogical exploration of episteme. Moving beyond a scientific description of the forest, what other epistemes enliven our imaginations?

Part II: Understory – Overstory: A Canadian forest imaginary

In this section we provide some background on eco-phenomenology—a unique philosophical approach to inquiry. Interspersions of eco-phenomenological inquiry (concepts the forest reveals) alongside theoretical perspectives are interpreted. Photographic images and artwork illustrate and extend various eco-phenomenologies. Through eco-phenomenological sensing and engaging with our uplands forest, these artful experiences have helped explore creative ways of understanding and relating to our forest, leading as we shall see, to a more relational and caring imaginary of human–forest relationships (Rousell et al., Reference Rousell, Hill, Ryan, Harvey, Barns, Aleksic and Boadu2025). We are beginning to recognise our own work, methodologically, parallels Indigenous people’s “understanding of ecological relationship reflected in every aspect of their lives, their language, art, music, dance, social organisation, ceremony and their identity of themselves as human beings” (Cajete, Reference Cajete1996, p. 136).

Our methodological approach is informed philosophically through eco-phenomenology the “intersection of environmental philosophy with phenomenology” (Brown & Toadvine, Reference Brown and Toadvine2003, p. xii). It is based on two claims: an account of “our ecological situation requir[ing] the methods and insights of phenomenology; and, that phenomenology becomes a philosophical ecology, the study of the interrelationship between organism and world in its metaphysics and axiological dimensions” (xiii). Thereby, eco-phenomenology avoids the dualism of classical Cartesian thought while paving the way for a “new rationality where reason encounters and enters dialogue within the values of our human and more-than-human experienced worlds” (xix).

Adopting an eco-phenomenological approach to the recording of our experience(s) within our uplands forest, not only provides the physical setting for existential experiences in the natural world, but too, imaginative opportunities to expand our constrained modern relationships with the natural world. Three significant eco-phenomenological experiences are shared here, revealed through extended encounters within our forest. Through our practical engagement with the world, rather than our Cartesian perspective of the world (objectified through distance), natural phenomena are revealed – rather than explaining these phenomena, the phenomena reveal themselves. Of course, nothing revealed to humans exists without interpretation. Descriptions of phenomena are subject to our interpretation and this leads to further understanding. This is the significant insight and contribution of philosopher Martin Heidegger (Reference Heidegger1927/1962). Heidegger’s critique of traditional analytic philosophy offers up hermeneutic phenomenology. A philosophy recognising the descriptive and reiterative interpretive processes (hermeneutic circle) germane to human understanding (Moran, Reference Moran2000).

From the outset, we have drawn to an assemblage of theoretical influences heralding from several realms of experience, for example, science, literature, philosophy and the arts. The manner these theoretical and philosophical insights are presented here, recapitulates the chronology of our inquiry. Here too we discover Indigenous people’s embodiment of a “Philosophy of Native Science. . . that can include metaphysics and philosophy, art, architecture, practical technologies and agriculture, as well as ritual and ceremony practices” (Cajete, Reference Cajete and Waters2004, p. 47). In Part I, we began first with the sciences. Our attempt at an ‘ecological’ description in the previous section draws from the scientific realm of experience. Furthermore, the ecological concept of “understory” and “overstory” describe the vertical layers of the forest ecosystem. This figuratively and architecturally orients our work: an eco-phenomenological investigation within a forest and how this inspired a philosophy of education called poetism. Over-simply and literally, the forest understory consists of several layers including herbaceous plants (< foot), shrub plants (3–6 feet), younger perennial trees (20–30 feet). The overstory consists of those mature tree species that exceed 30 feet forming a relatively consistent canopy layer toward the top of the forest ecosystem. In like manner, the understory (our eco-phenomenological disclosures) inspired the overstory (poetism). Figuratively, the understory reflects direct experience (eco-phenomenology), while the overstory represents the broader philosophy (poetism) that grows from it. First-hand, immediate lived experiences traversing our forest’s under-overstories, accrued through daily and seasonal walking and exploring, provide rich opportunities for interpretive reflection. Traversing the forest understory imagines poetism as an overstory. Poetism as a philosophy of education aims to reclaim mystery in our lives.

From the field of literary studies, our work is inspired and enlivened through Robert Harrison’s Forests: The Shadow of Civilization (Reference Harrison1992). Harrison’s literary breadth and depth of knowledge regarding the role literature serves in enlivening the imagination through forests is remarkable. His is a literary work inspired by numerous scholars and artists who are in turn inspired by forests. The premise of his book is that since antiquity, forests have shared a paradoxical relationship with humans. On the one hand, they are revered; on the other hand, held hostile. He argues, that only by examining the “genetic psychology of the earliest myths and fables, which preserve in their figures the hieroglyphs of that enigmatic psychic history from which empirical history derives its inspiration” (p. 3) can we come to understand our present.

While his work informs ours on several levels, it is his explicit reference to Giambattista Vico’s New Science (Reference Vico1725/1968) that we find both intriguing and insightful. In Vico’s New Science, he applied to the ancient myths a genetic psychology leading him deep into the forests of prehistory in search of the origins of “three universal institutions” (p. 3), what he termed, religion, matrimony and burial of the dead. The evolution of these universal institutions follows this course: “first the forests, after that the huts, then the villages, next the cities, and finally the academies” (§232). Adds, Harrison (Reference Harrison1992) “The order is systematic, progressive, and self-sustaining, but it comes to an end, haunted by finitude” (p. 11). The entropic drive to dissolution drives civilisation to disorder. It operates on another level too, that of humanity adds Vico (1725/1968): “The nature of peoples is first crude, then severe, then benign, then delicate, finally dissolute” (§242). In sum he concludes that the drive to greater and greater synthesis sustains the order during its initial stages but eventually gives way to analysis and then collapse. The culprit, he argues is irony (Harrison, Reference Harrison1992). When we lose the admiration and respect for tradition, because of its fallibility, we can become consumed by cynicism and despondency. The myths and fables of the forest have much to reveal about human–forest relations.

Over time Vico’s theory (Reference Vico1725/1968) has become a fable yet retains the psychic influence of theory as it offers a sort of “imaginative insight that makes its theory irrevocable, long after it has become a fable” (p.3). As fable, Vico’s work provides its most essential insights. Also unique to Vico’s work, is the introduction to tragedy. The myths of antiquity are resplendent with tragedy, revealed as a fatal collision between divergent laws. Where opposing laws abide, an edge or border manifests.

This extreme edge, where opposing laws strive against one another and where the more primordial one wins out, is the boundary at which the city meets the forest [our emphasis] (Vico, Reference Vico1725/1968, p. 3).

Where and when this boundary is drawn becomes the founding feature of our work. Hannigan (Reference Hannigan2024) a contributor to the CFS Collaboratory, recognises the same:

Forest Boundaries: In our increasingly urbanised world, forests often exist within defined boundaries, interfacing with farmlands or suburban areas. These demarcations highlight forests as places of urban and regional regeneration, repair and reimagining. (https://www.criticalforestlab.com/portfolio-collections/my-portfolio/forest-boundaries)

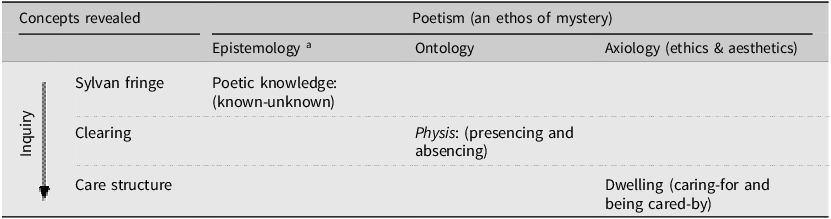

Through our periodic ramblings through the forest, three concepts came to the fore: the sylvan fringe, the clearing and the care structure. We have previously disseminated important insights into the concept of the sylvan fringe (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harvey2025). The bulk of this work centres on the latter two concepts, the clearing and the care structure. The latter concept is given by the former. Important to recognise is that the three forest phenomena are co-constituted and mutually interdependent. A brief retrospective of the sylvan fringe builds to a detailed examination of the clearing and its care structure. Table 1 is helpful in tracing the relationship between the concepts of the sylvan fringe, the clearing and the care structure revealed through lived experiences within the forest, and their respective interpretation through the ontological, epistemology and axiological domains of a philosophy of education (Ornstein et al., Reference Ornstein, Levine, Gutek and Vocke2017). Poetism as a novel philosophy whose aim is to nurture an ethos of mystery for education theory and practice is imagined. Beginning with the left-hand column heading, the concepts revealed within the forest included the sylvan fringe, the clearing and the care structure. The evolution of our inquiry proceeded with lived experiences first revealed through the sylvan fringe, then the clearing and last the care structure. Moving from left–right, we trace the manner each of these concepts could be interpreted through the column headings: epistemology, ontology and axiology as domains of philosophy of education. Where respective rows and columns intersect, the character of mystery is elaborated. Collectively, through these domains, poetism as a philosophy of educating nurturing an ethos of mystery is imagined. We turn our attention now to the eco-phenomenologies imagining poetism.

Table 1. Poetism as a philosophy of education

Note.Table 1 demonstrates the epistemological, ontological and axiological domains of poetism as a novel philosophy of education. aPhilosophy of education consists of ontological, epistemological and axiological domains (Ornstein et al., Reference Ornstein, Levine, Gutek and Vocke2017).

Sylvan Fringe. Daily transits through our Canadian uplands forest have revealed a fascinating phenomenon – the sylvan fringe. Sylvan from the Latin sylvanae meaning “goddess of the woods” and silvanus “pertaining to the woods or forests” (Etymonline.com, 2025b). The term fringe derives from the Latin fimbria meaning “fibers, threads, or fringe”; “a border, edge”; and recently the “outer edge, or margin” (Etymonline, 2025c). Together sylvan + fringe suggests a wooded margin or border (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3. The Sylvan fringe: wooded margin #1.

Figure 4. The Sylvan fringe: wooded margin #2.

Our sojourning – meanderings between the forest proper and adjacent farm fields first provided encounters with mystery catalysed through a particularly unusual forest flower growing in the open along the forest floor. Resisting temptation to “explain away” (e.g., naming or labelling it) the flower, we remained silent – staying with it, letting-it-be. Further reflections upon this experience led to the following.

Forest, from the Latin foris meaning “outside” (Etymonline, 2025a) from that which is settled, as a psychic, physical, intellectual, emotional, cultural, natural and imaginative boundary separating humans from nature, qua nature. This leads naturally to the philosophical work of Charles S. Brown and Ted Toadvine, specifically their work Nature’s Edge: Boundary Explorations in Ecological Theory and Practice (Reference Brown and Toadvine2007) who profile boundaries, conceptually, as places that mediate binary extremes.

The forest, “that which is outside” human existence, exhibits a unique feature where separations between binary constructs are blurred. This feature of the sylvan fringe, that boundary on the edge of a forest clearingFootnote 9 – where light and dark are diffuse, where sound and silence mollify one another, where moisture and desiccation comingle, ultimately, where nature and culture encounter one another, where being and non-being reside; is where the transit of mystery resides – the oscillating interplay between the known-unknown. The “unknown” flower we discovered one day while transiting a well-trodden path across the sylvan fringe revealed this to us. This stage of our inquiry exposed an epistemological appreciation for mystery, as a binary co-relate of knowledge. We refer to this dynamic between the known-unknown as poetic knowledge,Footnote 10 Fragment (Karrow, Reference Karrow2010, p. 95). However, upon further investigation and reflection we realised there was another facet to mystery, an ontological dimension elaborated further through our eco-phenomenological ventures through the sylvan fringe.

Thinking about the unusual forest flower situated within the transit of the sylvan fringe got us thinking deeply about nature. Heidegger (Reference Heidegger1927/1962) was attentive to the manner our modern understanding of nature has increasingly been shaped by technology and retrieved from a careful historical analysis of Western history a more primordial understanding of the term (The ancient view of nature he resurrects from the Greek is termed physis). Physis as an ancient understanding of nature preserves much about it – namely, a sense of mystery. Here we were able to make a connection between our “mysterious” forest flower and an ancient view of nature as physis. Within this ancient concept of nature was too, the enigma of mystery (Caputo, Reference Caputo1986), preserved beautifully and wholly.

Unlike our modern conception of nature (using the forest as an example) construed mainly as resource (e.g., lumber, pulp and paper, sap, heat and energy), the ancient view of nature could be understood in terms of physis.

Physis . . . emerges from itself (e.g., the emergence, the blossoming of a rose), the unfolding opens itself up, the coming-into-appearance in such unfolding, and holding itself and persisting in appearance – in short, the emerging-abiding sway (Heidegger, 1953/Reference Heidegger, Fried and Polt2000, p. 15).

Paraphrasing Bigwood (Reference Bigwood1993) provides a more accessible definition. “Physis implies a two-fold movement: an entity surges up into the unconcealment of appearance, and yet it rises out of concealment, reclining into concealment even in its rising” (Karrow, Reference Karrow2010, p. 23). Simply, a tree soars up, extending and opening itself to the sky, and in the other direction, it reclines back into its roots, hiding itself in the earth. In this way, it grows and yet stays with itself (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Physis: ancient Greek word for nature – presencing and absencing (mystery).

Our thinking about the forest through the ancient view of nature as physis and its juxtaposing with the unusual forest flower as “mysterious” furthered our understandings about mystery as a phenomenon. In addition to viewing mystery as an epistemological phenomenon (revealed through our encounter with the unknown flower, confronted by what it is, we began to appreciate that mystery also has an ontological domain, that it is.

The clearing. Further transits across, through and within the sylvan fringe revealed the concept of the clearing. A forest clearing consists of an open region which may occur in various ways (e.g., when a mature tree dies within a forest (Figure 6 and 7), when land adjacent to a forest is cleared for human purposes (e.g., agriculture) (Figures 3 and 4) and when a body of water interrupts the forest floor (Morrison, Reference Morrison2003). The forest clearing presented in Figures 6 and 7 is the result of the decline of a mature tree. Upon dying and decomposing, the forest floor now “opened” receives light and moisture, ideal to the conditions optimal for germination of successive forest beings. The lit region toward the centre of the photograph, at the destination of the forest path, is the epi-centre of the clearing (Figure 6). From an aerial perspective, the clearing appears as an opening in the forest canopy (Figure 7). Here we catch a glimpse, a remnant of a mature beech tree, its erect trunk the vestige of its being; its canopy sheared off, decomposing upon the forest floor. In its place, the canopy “clears” allowing sunlight and rain upon that region of the forest floor. New tree “beings” come forth. If we look carefully another generation of trees and shrubs (greenery) are becoming.

Figure 6. Terranean forest clearing.

Figure 7. Aerial forest clearing. Photo credit Callum McLellan.

Heidegger’s thoughts expressed in Being and Time (BT) (1927/Reference Heidegger1962), and On the Origin of the Work of Art (OWA) (Heidegger, 1953/Reference Heidegger and Krell1993a) and Building, Thinking, and Dwelling (Heidegger, 1971/Reference Heidegger and Krell1993b) have been informative. Specifically, Heidegger’s (1971/Reference Heidegger and Krell1993b) concept of the clearing (Figures 6 and 7) was formative in his conceptualisation of human being or Dasein. Although BT is the fulsome articulation of Dasein (human being) we gather some sense of how the forest’s clearing furthered his thinking on the matter from his OWA.

In the midst of being as a whole an open place occurs. There is a clearing, a lighting. Thought of in reference to what is, to beings, this clearing is in a greater degree than are beings. This open centre is therefore not surrounded by what is; rather, the lighting center itself encircles all that is, like the Nothing which we scarcely know. That which is can only be, as a being, if it stands within and stands out within what is lighted in this clearing. Only this clearing grants and guarantees to us humans a passage to those beings that we ourselves are not, and access to the being that we ourselves are. (p. 178)

The clearing and sylvan fringe work together (Figures 3, 4, 6 and 7). They are proximate and co-constituted. And while our previous work was useful in thinking through the imaginative and philosophical potential of the sylvan fringe (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harvey2025) it is the clearing that helped us understand the phenomenon of mystery ontologically. The enigma of mystery is held together through dual ontological movements of presencing-absencing. Mystery, as we discovered, also has an ontological domain to it.

Care structure. Within the clearing, another concept alluded to in the previous eco-phenomenology, comes to the fore. When one carefully observes the clearing within a forest one sees how the gradual decline of a mature forest tree gives way to another generation of trees (Figures 6 and 7). Upon the lit region toward the end of the path (Figure 6), centred across the field of the picture, careful examination reveals tiny tree seedlings growing upward. In Figure 7, the area immediately surrounding the declining beech tree trunk is plush with regenerative growth. For some tree species (e.g., beech trees), the growth of another generation precedes the death of the mother tree. Often referred to as “nurse trees,” while the decline of the mother tree creates space and nutrients for seeds to germinate, and important soil nutrients supported through mycorrhizal networks (Simard, Reference Simard2021) for the developing saplings, strong and virile trees (already 5–15 years old) become well established within the clearing. Not only does the mother tree appear in the clearing but it does so particularly. This facet of the concept of clearing gives way to something else.

From his previous description of Dasein (human being) (Heidegger, 1927/Reference Heidegger1962), Heidegger turns his attention to another concept beyond detailed exploration here, dwelling (Heidegger, 1953/Reference Heidegger, Fried and Polt2000), yet essential to poetism. We take a slight detour here to explore dwelling, which reveals the care structure experienced through the clearing. Through his careful analysis of dwelling Heidegger elaborates on the concept of the care structure.

To dwell is to be at peace, to be brought to peace, to remain in peace. The word for peace, Friede, means the free, das Frye [in old German] and fry means: preserved from harm and danger, preserved from something, that is, taken-care-of [geschont]. To free really means to care-for [schonen]. The caring-for itself consists not only in the fact that we do no harm to that which is cared-for. Real caring-for is something positive and happens when we leave something beforehand in its nature [Wesen], [or] when we gather [Bergen] something back into its nature, when we ‘free’ it in the real sense of the word into a preserve of peace. To dwell, to be set at peace, means to remain at peace within the free sphere that cares-for each thing in its own nature. The fundamental character of dwelling is this caring-for (Heidegger, 1971/Reference Heidegger and Krell1993b, p. 149).

In other words, to dwell is: (1) to be cared-for in the dwelling-place and (2) to care for the things of the dwelling-place. Young (Reference Young2002) expands on this by adding,

To dwell is to experience oneself as safe in, cared-for-by, the dwelling-place in a way one is not safe in or cared-for by the foreign, and to dwell is to care for the place where one dwells in a way one does not care for the place where one does not (p. 64).

Through the forest clearing we observed an example of the care structure through nurse beech trees and young beech saplings. The mother beech tree cares-for its beech tree saplings; and in turn, is cared-for by them. This essential care structure is the foundation for our existential existence (Heidegger, 1927/Reference Heidegger1962). It manifests within the clearing and is articulated through the concept of dwelling. Given the care structure is a responsibility (it involves security and guardianship) it expresses the axiological domain of poetism as a philosophy of education. And while beyond detailed examination here, dwelling comprises an axiological domain of poetism (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harveyforthcoming) (Table 1).

Summarising Table 1, our eco-phenomenologies, situated within the forest’s sylvan fringe initially revealed mystery epistemologically, as the dynamic between the known-unknown. The strange and unknown flower along the forest floor initially got us thinking in this way. Being open or receptive to mystery required acceptance of the dynamism between the known-unknown. We refer to this dynamism as poetic knowledge. Through the sylvan fringe we experienced forest clearings. Further reflection upon these clearings and an ancient understanding of nature as physis expanded our appreciation of mystery to include the ontological. We recognised that inherent to physis is an ontological dynamism, expressed through presencing-absencing. In addition to our initial and naïve understanding of mystery as epistemological (known-unknown), mystery could be considered ontologically (presencing-absencing). Furthermore, within the forest clearing the deeply fundamental concept of the care structure was revealed. The intimate, delicate yet enduring relationship mother nurse beech trees share with successive beech tree saplings through the clearing exposed an eternal existential care structure. Expressed through dwelling as the axiological domain of poetism, we expanded our understanding of mystery to include epistemological, ontological and axiological domains. Mystery then is the playful enigma manifesting ontologically as presencing-absencing (physis) (Caputo, Reference Caputo1986), epistemologically as the continuum of the known-unknown (poetic knowledge) and axiologically as dwelling (the mystery of existence between being and place). In this way, our forest inspired an enlivened imagination. Poetism as a philosophy of education’s central aim is to nurture an ethos of mystery in education theory and practice.

Part III: Critical forest studies and teacher environmental education

How does our work supporting CFS relate with teacher environmental education? CFS has an important and pivotal role to play in the future of teacher education. Preparing future teachers to understand the critical role forests play in our ecosystems, the imaginative potential they hold to engage humans so necessary to nurturing an ethos of mystery for education theory and practice, is vital to our very survival on this planet. We turn our attention to consider this now. Explicating this requires that we consider where CFS might fit into traditional currents of environmental education (Sauvé, Reference Sauvé2005) and what programmatic models support its implementation.

In her groundbreaking work, Lucie Sauvé (Reference Sauvé2005), Currents in Environmental Education: Mapping a Complex and Evolving Pedagogical Field, provides a cartography of the main currents in environmental education since the field’s origin in the 1970s. Identifying the main currents, she highlights the current’s conception of the environment, aims of education, [pedagogical] approaches and examples of these. The cartography provides a useful way of thinking about the myriad philosophical/theoretical approaches underpinning the field, and, while dated, allows new disciplinary sub-fields (e.g., CFS) to orient and differentiate their contribution to the field. In referring to this period piece, we recognise the importance of environmental education in teacher education (Karrow & DiGiuseppe, Reference Karrow and DiGiuseppe2019), specifically in the province of Ontario, Canada, where it is officially recognised by our Ministry of Education through policy (OME, 2009). As policy, environmental education is to be taught within Ontario’s K-12 schools, and by implication Ontario teachers are to be educated and trained how to do this. Faculties of education who educate and train future teachers are required to ensure they comply with this policy and their accreditation by professional colleges is contingent upon this.

Critical Forest Studies (CFS), with its emphasis on the relationship between humans and forests appears to align naturally with many of Sauvé’s (Reference Sauvé2005) currents of environmental education. In particular, Sauvé’s holistic environmental education current, whose concept of the environment orients to Holos, Gaia, All, or The Being, whose aim of education is to “develop the many dimensions of one’s being in interaction with all aspects of the environment” while somewhat anthropocentric, begins to recognise the contributions the theoretical foundations of CFS, inspired by (post-humanism and neo-materialism), could make to this current, and environmental education, more broadly. Regarding our own philosophy of education (poetism) and its celebration of mystery, we see resonances with Sauvé’s (Reference Sauvé2005) holistic environmental education current. In this way, CFS and poetism readily complement one another.

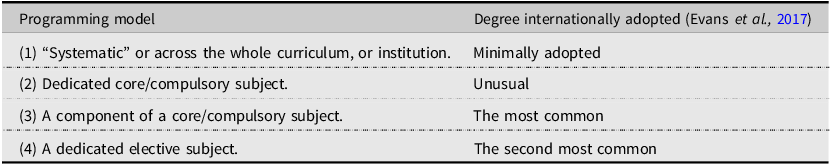

Lastly, what programmatic models might support CFS in teacher education? Again, there are a variety. We point the reader to the work of Evans et al., Reference Evans, Stevenson, Lasen, Ferreira and Davis(2017) who present a useful typology of programmatic models for implementing environmental education (Table 2). A careful review of table demonstrates the degree to which environmental education is the programming focus of education.

Table 2. Environmental education programming: models of implementation

Note. Table demonstrates various environmental education programming models and degrees of adoption in international teacher education.

Of course, a variety of variables are at play determining the degree to which any environmental education programme model (e.g., CFS) might get traction in teacher education and by implication K-12 education. In the international context (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Stevenson, Lasen, Ferreira and Davis2017) models (3) and (4) are the most common approaches to implementing environmental education in teacher education, whereas models (1) and (2) are uncommon. We would argue, poetism because it resonates with the holistic current of environmental education could support and direct progamming models (1) and (2) in the hands of an experienced environmental educator. The efforts of postsecondary teacher educators in supporting teachers through such programming models are ongoing. In summary, the holistic current of environmental education and the programming models considered for implementation – (1) systematic or (2) dedicated – can go some way to ensuring CFS influences traditional environmental education in teacher education and K-12 education.

IV: Summary

Revisiting research objectives and questions

Regarding our first objective, we have demonstrated how eco-phenomenology reveals our relational engagement with forests and inspires poetism, useful to teacher environmental education. Regarding the second objective we have begun to demonstrate the unsettling and decolonising of Western settler views of a Canadian forest. There is more work to do here and we will speak to this shortly. Turning our attention to the research questions – In what ways might a Canadian uplands deciduous forest provide creative ways of understanding and relating to the sentient forest? – we have demonstrated how our immediate first-hand experiences traversing our Canadian deciduous uplands forest holds within it the promise of imaginative and theoretical engagement. Eco-phenomenologies experienced first-hand within our forest have revealed three concepts – the sylvan fringe, the clearing and the care structure – and their interpretation through various theoretical perspectives. Enlivened, our imagination has conjured poetism as a novel philosophy of education nurturing an ethos of mystery for education theory and practice. Poetism, nurtures mystery in our lives by foregrounding being’s duel ontological movements of presencing-absencing, an appreciation and acknowledgement for poetic knowledge preserving the dynamism of the known-unknown and an axiology founded upon a care structure expressed through dwelling. An eco-phenomenological understory creates a philosophical overstory. Forests have much to share with us if we are open and receptive to them. Critical Forest Studies (CFS) as a field of inquiry, legitimises the important space such inquiry demands.

Limitations and outstanding questions

We recognise several limitations to our work. First, our initial efforts to decolonise our work are minor first steps. There is the ongoing work of decolonising our Western privilege beyond Land Acknowledgement as we begin to recognise such Indigenous scholars as Cajete (Reference Cajete and Waters2004, Reference Cajete1996), Bang et al. (Reference Bang, Curley, Kessel, Marin, Suzukovich, Strack, McCoy, Tuck and McKenzie2016) and McCoy et al. (Reference McCoy, Tuck and McKenzie2016) who also value ecological aesthetics and traditional ecological knowledge. Through our combined efforts such philosophies (poetism and Indigenous philosophy) can support CFS. Second, our Canadian perspective may confer certain assumptions we may be blind to. For instance, Canada as a relatively young country retains much forested land and it takes this for granted. This is simply not the case in other places in the world where forest decline predates Canada. Canada could benefit from applying traditional ecological knowledge or forest-related wisdom from other countries before it repeats the mistakes of other countries. This would underscore the importance of maintaining international perspectives such as those fostered and supported through the CFS Collaborative. Although Canada has much to share, it can learn from others. And last, while poetism as a philosophy of education may seem esoteric and impractical, we have considered practical strategies applying it to teacher education and K-12 education (Karrow & Harvey, Reference Karrow and Harveyforthcoming). Outstanding questions include: (1) How can eco-phenomenology continue to support philosophical thinking? (2) How might poetism continue to support CFS and strategically educate teachers and K-12 students?

In closing, we make an appeal to the people and their forests of the world. In some cultures of the world the word for forest is “wild” or “mystery.” Quite simply, “The word for forest is mystery” (Bahnson, Reference Bahnson2022). In our last photograph (Figure 8) taken during the super full moon of last October, a deeply felt sense of forest as mystery was revealled. When we lose the capacity to sense and appreciate this, Harrison’s (Reference Harrison1992) startling conclusion is even more poignant:

Figure 8. The word for forest is mystery.

In the final analysis only this much seems certain: that when we do not speak our death to the world we speak death to the world. And when we speak death to the world, the forest’s legend falls silent (p. 249).

Acknowledgements

Reinhard Frederick Karrow (1907–2007), who inspired a deep appreciation of forests and trees through his conservation efforts.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical standard

Not applicable.

Author Biographies

Douglas D. Karrow is an Associate Professor in the Department of Educational Studies, Faculty of Education, Brock University. His current research interests are empirically and philosophically oriented. His empirical work focuses on environmental education programmes in P-20 contexts and his philosophical work explores the application of Martin Heidegger’s ideas to education.

Sharon R. Harvey serves as Associate Teaching Professor with Arizona State University in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts. Her research interests include environmental education, and Heidegger and education. She worked with K-12 schools through supervising an after-school tutoring programme and has served on the local governing school board.