1 Introduction

1.1 Overview

Branching graphs – particularly the Young lattice

![]() $\mathbb {Y}$

of integer partitions – have long held a central position at the crossroads of representation theory, combinatorics, and probability. Indeed, the Young lattice powers the representation theory of symmetric and (by Schur-Weyl duality) general linear groups, giving rise to Schur functions and driving profound connections to random matrix theory and statistical mechanics. In this landscape, the Plancherel measure on

$\mathbb {Y}$

of integer partitions – have long held a central position at the crossroads of representation theory, combinatorics, and probability. Indeed, the Young lattice powers the representation theory of symmetric and (by Schur-Weyl duality) general linear groups, giving rise to Schur functions and driving profound connections to random matrix theory and statistical mechanics. In this landscape, the Plancherel measure on

![]() $\mathbb {Y}$

and its generalization, the Schur measures, have emerged as foundational objects. These probability measures (in the terminology of statistical mechanics, ensembles of random partitions) serve as a framework for exploring phenomena such as limit shapes, random tilings, and universal distributions governing eigenvalues in random matrix ensembles.

$\mathbb {Y}$

and its generalization, the Schur measures, have emerged as foundational objects. These probability measures (in the terminology of statistical mechanics, ensembles of random partitions) serve as a framework for exploring phenomena such as limit shapes, random tilings, and universal distributions governing eigenvalues in random matrix ensembles.

Despite the prominence of the Young lattice, kindred combinatorial structures remain relatively underexplored from a probabilistic perspective. One notable example is the Young–Fibonacci lattice

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

[Reference Fomin33], [Reference Stanley67], [Reference Okada54], [Reference Goodman and Kerov40]. Like the Young lattice,

$\mathbb {YF}$

[Reference Fomin33], [Reference Stanley67], [Reference Okada54], [Reference Goodman and Kerov40]. Like the Young lattice,

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

possesses a 1-differential poset structure defined, not on integer partitions, but rather binary words composed of the symbols

$\mathbb {YF}$

possesses a 1-differential poset structure defined, not on integer partitions, but rather binary words composed of the symbols

![]() $1$

and

$1$

and

![]() $2$

(known as Fibonacci words). As a 1-differential poset,

$2$

(known as Fibonacci words). As a 1-differential poset,

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

carries a Plancherel measure on Fibonacci words. The Young–Fibonacci lattice also mirrors other structures found in the classical Young lattice, such as versions of the Robinson-Schensted (RS) correspondence, multiparameter analogues of Schur functions, and a representation-theoretic framework introduced by Okada [Reference Okada54]. At the same time,

$\mathbb {YF}$

carries a Plancherel measure on Fibonacci words. The Young–Fibonacci lattice also mirrors other structures found in the classical Young lattice, such as versions of the Robinson-Schensted (RS) correspondence, multiparameter analogues of Schur functions, and a representation-theoretic framework introduced by Okada [Reference Okada54]. At the same time,

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

exhibits novel combinatorial and probabilistic behaviors, which are the main focus of the present work.

$\mathbb {YF}$

exhibits novel combinatorial and probabilistic behaviors, which are the main focus of the present work.

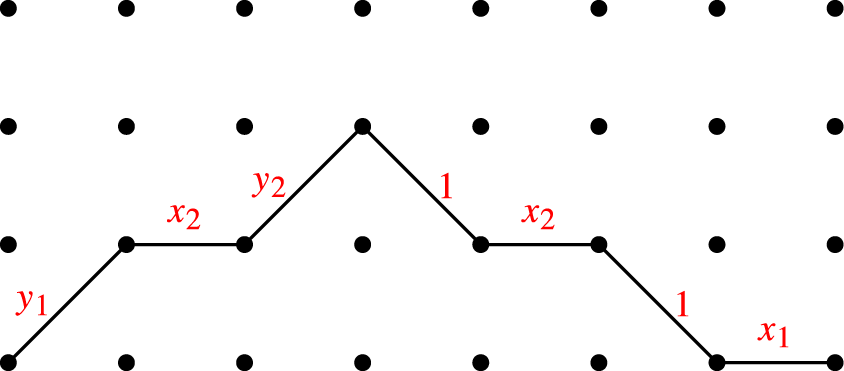

Our starting point is the theory of biserial clone Schur functions [Reference Okada54], a family of functions

![]() $s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

indexed by Fibonacci words

$s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

indexed by Fibonacci words

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}$

and involving two sequences of parameters

$w\in \mathbb {YF}$

and involving two sequences of parameters

![]() $\vec {x}= (x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots )$

and

$\vec {x}= (x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots )$

and

![]() $\vec {y}= (y_1, y_2, y_3, \ldots )$

. Clone Schur functions, first introduced by Okada, parallel the classical Schur functions

$\vec {y}= (y_1, y_2, y_3, \ldots )$

. Clone Schur functions, first introduced by Okada, parallel the classical Schur functions

![]() $s_\lambda (\vec z\hspace {1pt})$

,

$s_\lambda (\vec z\hspace {1pt})$

,

![]() $\lambda \in \mathbb {Y}$

,

$\lambda \in \mathbb {Y}$

,

![]() $\vec z=(z_1, z_2, z_3, \ldots )$

, in several aspects. Both Schur and biserial clone Schur functions branch according to a Pieri rule and, more generally, obey a Littlewood-Richardson rule which reflects the structure of covering relations in the

$\vec z=(z_1, z_2, z_3, \ldots )$

, in several aspects. Both Schur and biserial clone Schur functions branch according to a Pieri rule and, more generally, obey a Littlewood-Richardson rule which reflects the structure of covering relations in the

![]() $\Bbb {Y}$

and

$\Bbb {Y}$

and

![]() $\Bbb {YF}$

lattices. As a consequence, both Schur and biserial clone Schur functions give rise to harmonic functions on

$\Bbb {YF}$

lattices. As a consequence, both Schur and biserial clone Schur functions give rise to harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {Y}$

and

$\mathbb {Y}$

and

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

, defined respectively by

$\mathbb {YF}$

, defined respectively by

where n is the rank of

![]() $\lambda \in \mathbb {Y}$

or

$\lambda \in \mathbb {Y}$

or

![]() $w \in \mathbb {YF}$

. The Plancherel harmonic function (associated with the Plancherel measure) for each lattice arises from a special choice of parameters in Schur and clone Schur functions, respectively.

$w \in \mathbb {YF}$

. The Plancherel harmonic function (associated with the Plancherel measure) for each lattice arises from a special choice of parameters in Schur and clone Schur functions, respectively.

Positive specializations of classical Schur functions (sequences

![]() $\vec z$

for which

$\vec z$

for which

![]() $s_\lambda (\vec z\hspace {1pt})$

is positive for all

$s_\lambda (\vec z\hspace {1pt})$

is positive for all

![]() $\lambda \in \mathbb {Y}$

) are central in the study of the Young lattice. They are related to total positivity [Reference Aissen, Edrei, Schoenberg and Whitney2], [Reference Aissen, Schoenberg and Whitney3], [Reference Edrei24], [Reference Edrei25], characters of the infinite symmetric group [Reference Thoma70], and asymptotic theory of characters of symmetric groups of increasing order [Reference Vershik and Kerov71].

$\lambda \in \mathbb {Y}$

) are central in the study of the Young lattice. They are related to total positivity [Reference Aissen, Edrei, Schoenberg and Whitney2], [Reference Aissen, Schoenberg and Whitney3], [Reference Edrei24], [Reference Edrei25], characters of the infinite symmetric group [Reference Thoma70], and asymptotic theory of characters of symmetric groups of increasing order [Reference Vershik and Kerov71].

One important distinction with the

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

-lattice is that the harmonic functions on

$\mathbb {YF}$

-lattice is that the harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {Y}$

associated with positive specializations of classical Schur functions are extremal (this property is also often called ergodic, or minimal). Extremality means that the functions

$\mathbb {Y}$

associated with positive specializations of classical Schur functions are extremal (this property is also often called ergodic, or minimal). Extremality means that the functions

![]() $\lambda \mapsto s_\lambda (\vec {z}\hspace {1pt} ) / s_{\scriptscriptstyle \Box }^n(\vec {z}\hspace {1pt})$

cannot be expressed as a nontrivial convex combination of other nonnegative harmonic functions. In contrast, this extremality property does not generally hold for positive harmonic functions arising from specializations of biserial clone Schur functions. One of the initial motivations for our work was to investigate the broad question of how clone harmonic functions on

$\lambda \mapsto s_\lambda (\vec {z}\hspace {1pt} ) / s_{\scriptscriptstyle \Box }^n(\vec {z}\hspace {1pt})$

cannot be expressed as a nontrivial convex combination of other nonnegative harmonic functions. In contrast, this extremality property does not generally hold for positive harmonic functions arising from specializations of biserial clone Schur functions. One of the initial motivations for our work was to investigate the broad question of how clone harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

decompose into extremal components. The classification of extremal harmonic functions on

$\mathbb {YF}$

decompose into extremal components. The classification of extremal harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

was established in [Reference Goodman and Kerov40], and results on the boundary of

$\mathbb {YF}$

was established in [Reference Goodman and Kerov40], and results on the boundary of

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

were strengthened in the preprints [Reference Bochkov and Evtushevsky10], [Reference Evtushevsky26].

$\mathbb {YF}$

were strengthened in the preprints [Reference Bochkov and Evtushevsky10], [Reference Evtushevsky26].

Our first goal is to investigate conditions for which a specialization

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

is Fibonacci positive – in the sense that the biserial clone Schur functions

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

is Fibonacci positive – in the sense that the biserial clone Schur functions

![]() $s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

are strictly positive for all Fibonacci words

$s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

are strictly positive for all Fibonacci words

![]() $w \in \Bbb {YF}$

. Subsequently, we explore probabilistic and combinatorial properties of Fibonacci positive specializations and related ensembles of random Fibonacci words. The present work extends and completes several well-studied classical topics associated with the Young lattice

$w \in \Bbb {YF}$

. Subsequently, we explore probabilistic and combinatorial properties of Fibonacci positive specializations and related ensembles of random Fibonacci words. The present work extends and completes several well-studied classical topics associated with the Young lattice

![]() $\mathbb {Y}$

and Schur functions, adapting them to the Young–Fibonacci lattice

$\mathbb {Y}$

and Schur functions, adapting them to the Young–Fibonacci lattice

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

and clone Schur functions. Our four main contributions can be summarized as follows.

$\mathbb {YF}$

and clone Schur functions. Our four main contributions can be summarized as follows.

1. Characterization of Fibonacci positivity. We establish a complete classification of specializations

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

for which the clone Schur functions

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

for which the clone Schur functions

![]() $s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

are positive for all

$s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

are positive for all

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}$

. The concept of Fibonacci positivity strengthens the notion of total positivity of tridiagonal matrices whose subdiagonal consists entirely of 1’s. We identify two classes of Fibonacci positive specializations, of divergent and convergent type.

$w\in \mathbb {YF}$

. The concept of Fibonacci positivity strengthens the notion of total positivity of tridiagonal matrices whose subdiagonal consists entirely of 1’s. We identify two classes of Fibonacci positive specializations, of divergent and convergent type.

2. Stieltjes moment sequences and orthogonal polynomials. The connection to tridiagonal matrices places the Fibonacci positivity problem within the context of the Stieltjes moment problem and Jacobi continued fractions associated to totally positive tridiagonal matrices. We obtain two new combinatorial formulae for the moments of a Borel measure on

![]() $[0,\infty )$

in terms of the recursion parameters of the corresponding family of orthogonal polynomials. The first is a general formula that involves noncrossing set partitions, while the second requires a Fibonacci positive specialization of divergent type and is expressed as a sum over all set partitions. The first formula also exhibits a novel splitting of an integer composition into a unique pair of Fibonacci words.

$[0,\infty )$

in terms of the recursion parameters of the corresponding family of orthogonal polynomials. The first is a general formula that involves noncrossing set partitions, while the second requires a Fibonacci positive specialization of divergent type and is expressed as a sum over all set partitions. The first formula also exhibits a novel splitting of an integer composition into a unique pair of Fibonacci words.

For many examples of Fibonacci positive specializations, the Borel measure on

![]() $[0,\infty )$

is (after performing a change of variables) the orthogonality measure for a family of orthogonal polynomials from the (q-)Askey scheme [Reference Koekoek and Swarttouw48], including the Charlier, Type-I Al-Salam–Carlitz, Al-Salam–Chihara, and q-Charlier polynomials. In the latter two examples, the Fibonacci positivity enforces the atypical condition

$[0,\infty )$

is (after performing a change of variables) the orthogonality measure for a family of orthogonal polynomials from the (q-)Askey scheme [Reference Koekoek and Swarttouw48], including the Charlier, Type-I Al-Salam–Carlitz, Al-Salam–Chihara, and q-Charlier polynomials. In the latter two examples, the Fibonacci positivity enforces the atypical condition

![]() $q>1$

on the deformation parameter, in contrast to the usual assumption

$q>1$

on the deformation parameter, in contrast to the usual assumption

![]() $|q|<1$

in the q-Askey scheme.

$|q|<1$

in the q-Askey scheme.

3. Asymptotics of random Fibonacci words. We investigate the behavior of random Fibonacci words, (with respect to various Fibonacci positive specializations) in the limit as the word length grows. We find examples when growing random words

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

,

$w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

,

![]() $n\to \infty $

, exhibit one of the following three patterns:

$n\to \infty $

, exhibit one of the following three patterns:

-

○

$w=1^{r_1}21^{r_2}2\ldots $

, where

$w=1^{r_1}21^{r_2}2\ldots $

, where

$r_i$

scale proportionally to n;

$r_i$

scale proportionally to n; -

○

$w=2^{h_1}12^{h_2}1\ldots $

, where

$w=2^{h_1}12^{h_2}1\ldots $

, where

$h_i$

scale proportionally to n;

$h_i$

scale proportionally to n; -

○

$w=1^\infty v$

, that is, the word has a single growing prefix of 1’s, followed by a finite (random) Fibonacci word

$w=1^\infty v$

, that is, the word has a single growing prefix of 1’s, followed by a finite (random) Fibonacci word

$v\in \mathbb {YF}$

.

$v\in \mathbb {YF}$

.

In the first two cases, the joint scaling limit of either

![]() $(r_1,r_2,\ldots )$

or

$(r_1,r_2,\ldots )$

or

![]() $(h_1,h_2,\ldots )$

displays a “stick-breaking”-type behavior. More precisely, we extend the result of Gnedin–Kerov [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] who showed that, in the case of the Plancherel measure on

$(h_1,h_2,\ldots )$

displays a “stick-breaking”-type behavior. More precisely, we extend the result of Gnedin–Kerov [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] who showed that, in the case of the Plancherel measure on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

, the sequence

$\mathbb {YF}$

, the sequence

![]() $(h_1,h_2,\ldots )$

converges to the GEM distribution with parameter

$(h_1,h_2,\ldots )$

converges to the GEM distribution with parameter

![]() $\theta =\frac {1}{2}$

.

$\theta =\frac {1}{2}$

.

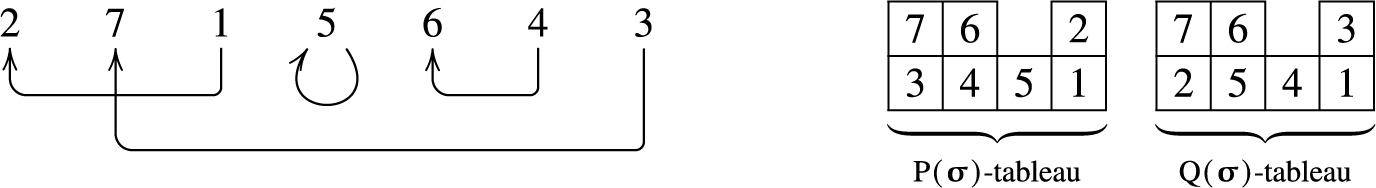

The Robinson-Schensted correspondence for the

![]() $\Bbb {YF}$

-lattice introduced by [Reference Nzeutchap53] (which we revisit in Section 16), the approach using the Stieltjes moment sequences mentioned above, and the results of [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] connect four distinguished probability distributions:

$\Bbb {YF}$

-lattice introduced by [Reference Nzeutchap53] (which we revisit in Section 16), the approach using the Stieltjes moment sequences mentioned above, and the results of [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] connect four distinguished probability distributions:

-

○ the uniform measures on permutations of

$\{1,2,\ldots ,n\}$

,

$\{1,2,\ldots ,n\}$

, -

○ the Plancherel measures on

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

determined by the differential poset structure,

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

determined by the differential poset structure, -

○ the Poisson distribution on

$\mathbb {Z}_{\ge 0}$

with parameter

$\mathbb {Z}_{\ge 0}$

with parameter

$\rho =1$

, and

$\rho =1$

, and -

○ the stick-breaking GEM scheme powered by the Beta distributions.

We extend and deform all these interrelated distributions. In particular, on the Beta distributions side, we find a new family of dependent stick-breaking schemes.

For random Fibonacci words almost surely behaving as

![]() $w=1^\infty v$

(the third pattern mentioned above), we determine the probability law of the random finite suffix

$w=1^\infty v$

(the third pattern mentioned above), we determine the probability law of the random finite suffix

![]() $v \in \Bbb {YF}$

in the limit in terms of the parameters

$v \in \Bbb {YF}$

in the limit in terms of the parameters

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

of the Fibonacci positive specialization. This distribution on the v’s gives the desired decomposition of the clone harmonic function

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

of the Fibonacci positive specialization. This distribution on the v’s gives the desired decomposition of the clone harmonic function

![]() $w\mapsto s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})/(x_1\cdots x_{|w|})$

into the extremal components.

$w\mapsto s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})/(x_1\cdots x_{|w|})$

into the extremal components.

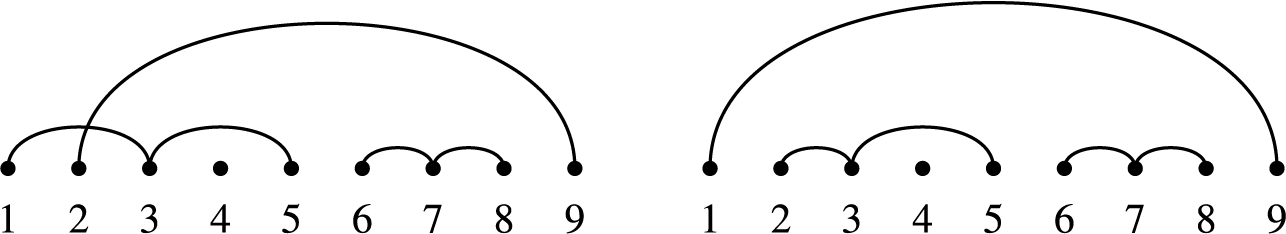

4. Clone Cauchy identities and random permutations. We establish clone Cauchy identities which are summation identities involving clone Schur functions, in parallel to the celebrated Cauchy identities for Schur functions. In the Young–Fibonacci setting, the right-hand side of each Cauchy identity is expressed by a quadridiagonal determinant (and not a product, like for classical Schur functions). We employ clone Cauchy identities to study models of random permutations coming from random Fibonacci words and a Robinson–Schensted correspondence for the

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

-lattice introduced in [Reference Nzeutchap53]. In particular, we compute the moment generating function for the number of two-cycles in a certain ensemble of random involutions, and explore its asymptotic behavior under a specific Fibonacci positive specialization. Other specializations may lead to interesting models of random permutations with pattern avoidance properties.

$\mathbb {YF}$

-lattice introduced in [Reference Nzeutchap53]. In particular, we compute the moment generating function for the number of two-cycles in a certain ensemble of random involutions, and explore its asymptotic behavior under a specific Fibonacci positive specialization. Other specializations may lead to interesting models of random permutations with pattern avoidance properties.

In the remainder of the Introduction, we formulate our main results in more detail. Further discussion of possible extensions and open problems is postponed to the last Section 18.

1.2 Clone Schur functions and Fibonacci positivity

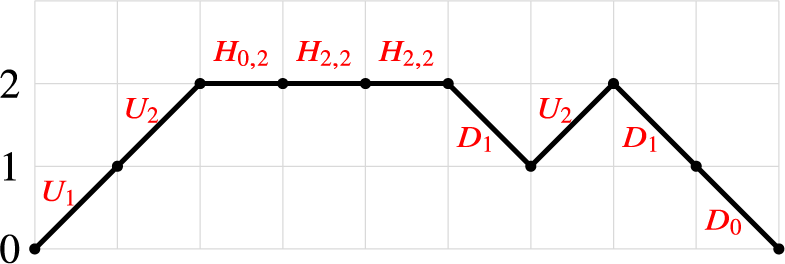

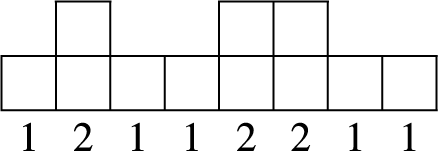

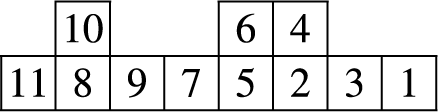

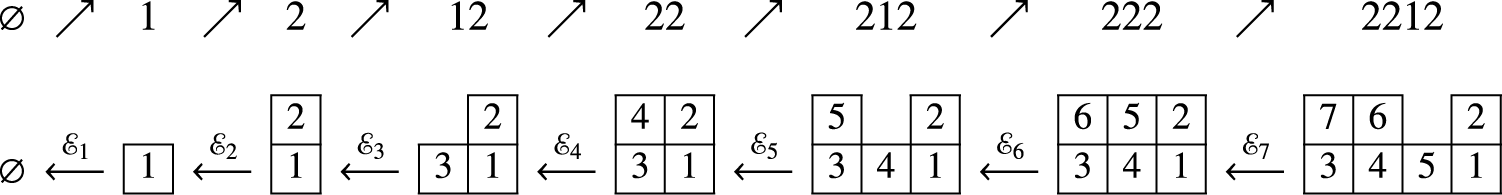

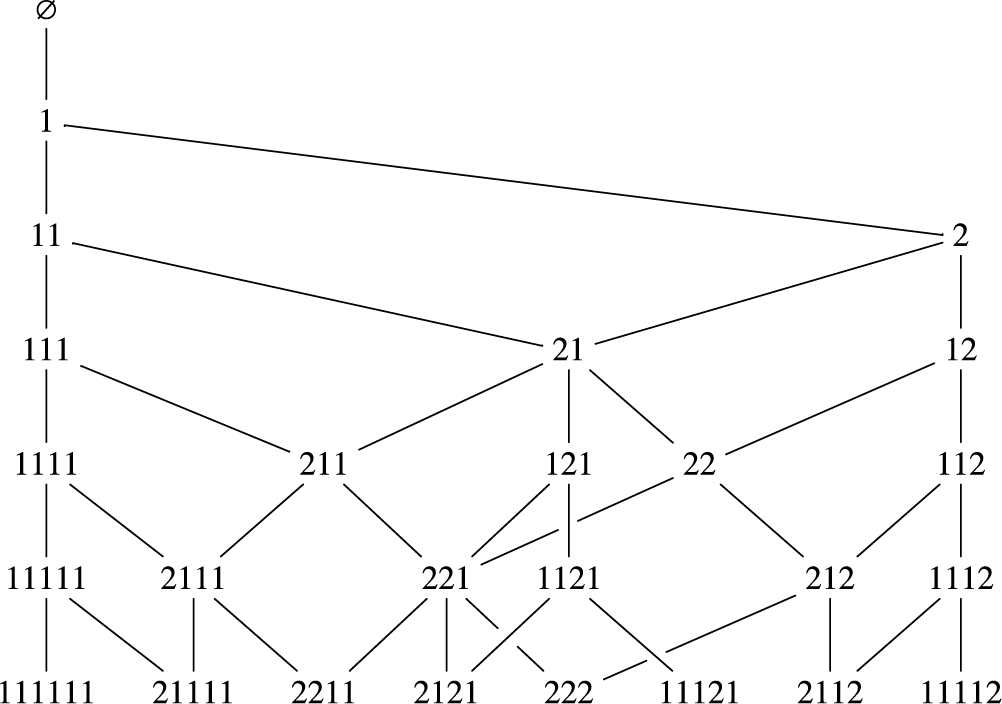

A Fibonacci word w is a binary word composed of the symbols 1 and 2. Its weight

![]() $|w|$

is the sum of the symbols. For example,

$|w|$

is the sum of the symbols. For example,

![]() $|12112|=7$

. By

$|12112|=7$

. By

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_n$

we denote the set of Fibonacci words of weight n. The lattice structure on

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

we denote the set of Fibonacci words of weight n. The lattice structure on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

is defined through branching (covering) relations

$\mathbb {YF}$

is defined through branching (covering) relations

![]() $w \nearrow w'$

on pairs of Fibonacci words, where

$w \nearrow w'$

on pairs of Fibonacci words, where

![]() $|w'| = |w| + 1$

. This relation is recursively defined to hold if and only if either

$|w'| = |w| + 1$

. This relation is recursively defined to hold if and only if either

![]() $w' = 1w$

, or

$w' = 1w$

, or

![]() $w' = 2v$

with

$w' = 2v$

with

![]() $v \nearrow w$

. The base case is given by

$v \nearrow w$

. The base case is given by

![]() $\varnothing \nearrow 1$

. Let

$\varnothing \nearrow 1$

. Let

![]() $\dim (w)$

denote the number of saturated chains

$\dim (w)$

denote the number of saturated chains

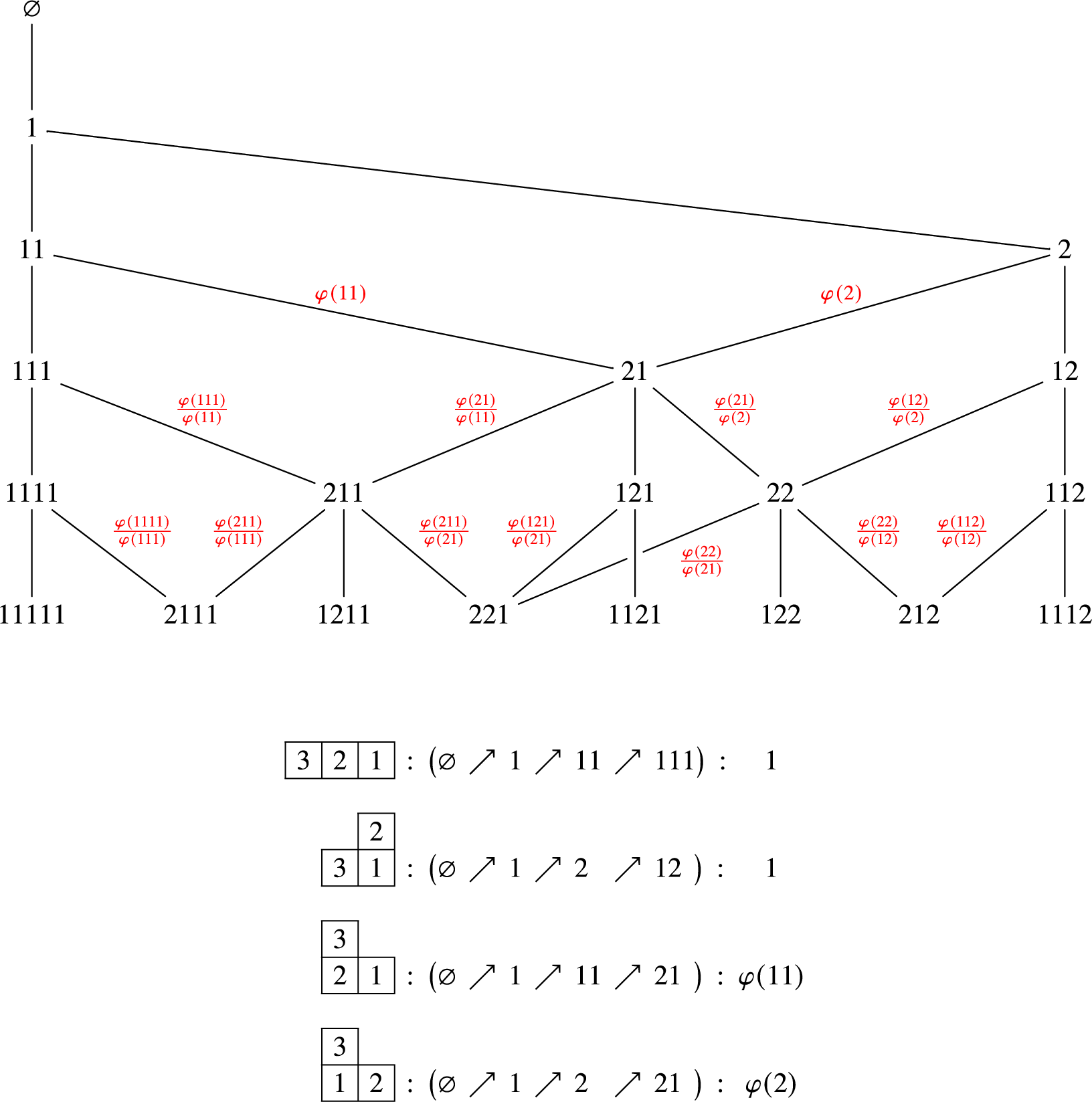

in the Young–Fibonacci lattice starting at

![]() $\varnothing $

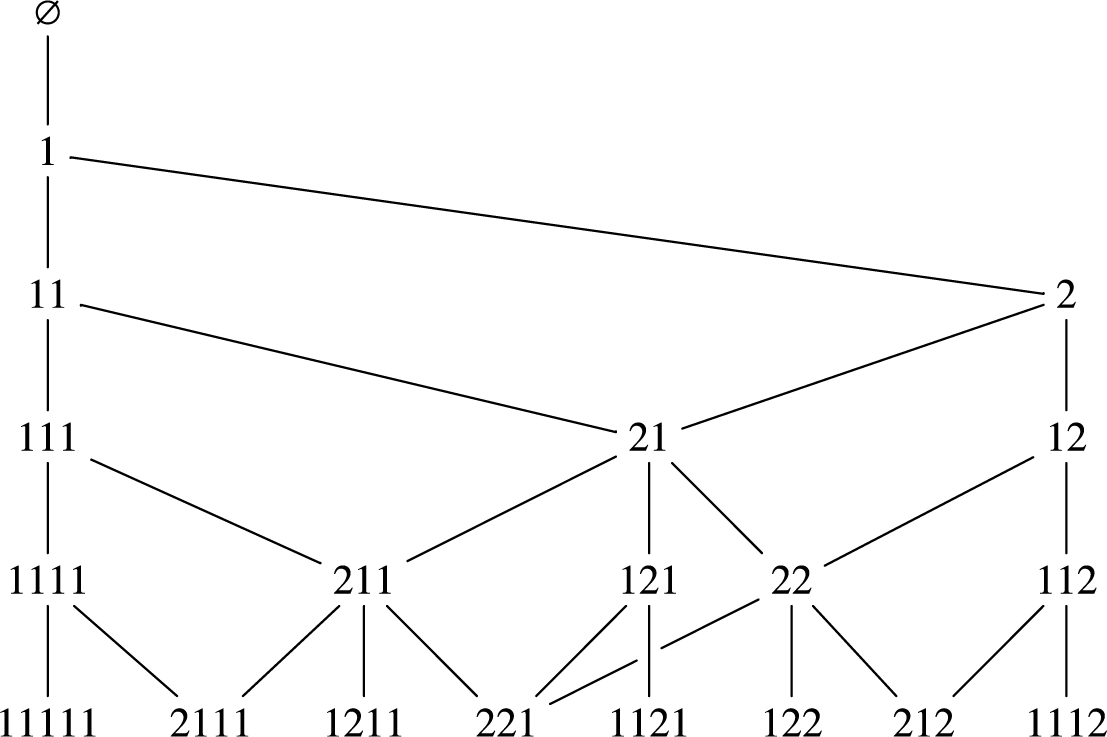

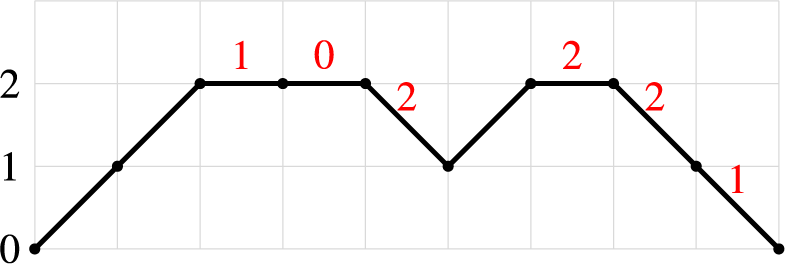

and ending at w. See Figure 1 for an illustration of

$\varnothing $

and ending at w. See Figure 1 for an illustration of

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

up to level

$\mathbb {YF}$

up to level

![]() $n=5$

. A function

$n=5$

. A function

![]() $\varphi $

on

$\varphi $

on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

is called harmonic if

$\mathbb {YF}$

is called harmonic if

for all

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}$

.

$w\in \mathbb {YF}$

.

Let

![]() $\vec x=(x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots )$

and

$\vec x=(x_1, x_2, x_3, \ldots )$

and

![]() $\vec y=(y_1, y_2, y_3, \ldots )$

be two sequences of parameters. Define the

$\vec y=(y_1, y_2, y_3, \ldots )$

be two sequences of parameters. Define the

![]() $\ell \times \ell $

tridiagonal determinants by

$\ell \times \ell $

tridiagonal determinants by

where nonzero elements in all rows in

![]() $A_{\ell }$

and all rows in

$A_{\ell }$

and all rows in

![]() $B_{\ell -1}$

except for the first one follow the pattern

$B_{\ell -1}$

except for the first one follow the pattern

![]() $(1,x_j,y_j)$

. Here and throughout the paper,

$(1,x_j,y_j)$

. Here and throughout the paper,

![]() $\vec x+r$

and

$\vec x+r$

and

![]() $\vec y+r$

denote the sequences with indices shifted by

$\vec y+r$

denote the sequences with indices shifted by

![]() $r \in \Bbb {Z}_{\geq 0}$

.

$r \in \Bbb {Z}_{\geq 0}$

.

The clone Schur function

![]() $s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

is defined by the following recurrence:

$s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

is defined by the following recurrence:

The function

is harmonic on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

. It is normalized so that

$\mathbb {YF}$

. It is normalized so that

![]() $\varphi _{\vec x,\vec y} \hspace {1pt} (\varnothing )=1$

.

$\varphi _{\vec x,\vec y} \hspace {1pt} (\varnothing )=1$

.

Our first main result is a complete characterization of the Fibonacci positive sequences

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

for which the clone Schur functions

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

for which the clone Schur functions

![]() $s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

are positive for all

$s_w(\vec {x}\,|\, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

are positive for all

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}$

:

$w\in \mathbb {YF}$

:

Theorem 1.1 (Theorem 4.12)

All Fibonacci positive sequences

![]() $(\vec x,\vec {y}\hspace {1pt})$

have the form

$(\vec x,\vec {y}\hspace {1pt})$

have the form

where

![]() $\vec c$

is an arbitrary positive sequence, and

$\vec c$

is an arbitrary positive sequence, and

![]() $\vec t=(t_1,t_2,\ldots )$

(with

$\vec t=(t_1,t_2,\ldots )$

(with

![]() $t_0=0$

, for convenience) is a positive real sequence of one of the two types:

$t_0=0$

, for convenience) is a positive real sequence of one of the two types:

-

○ (divergent type) The infinite series

(1.1) $$ \begin{align} 1+t_1+t_1t_2+t_1t_2t_3+\ldots \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} 1+t_1+t_1t_2+t_1t_2t_3+\ldots \end{align} $$

diverges, and

$t_{m+1}\ge 1+t_m$

for all

$t_{m+1}\ge 1+t_m$

for all

$m\ge 1$

;

$m\ge 1$

; -

○ (convergent type) The series (1.1) converges, and

$$ \begin{align*} 1+t_{m+3}+t_{m+3}t_{m+4}+ t_{m+3}t_{m+4}t_{m+5}+\ldots \ge \frac{t_{m+1}}{t_{m+2}(1+t_m-t_{m+1})} , \qquad \text{for all } m\ge0. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} 1+t_{m+3}+t_{m+3}t_{m+4}+ t_{m+3}t_{m+4}t_{m+5}+\ldots \ge \frac{t_{m+1}}{t_{m+2}(1+t_m-t_{m+1})} , \qquad \text{for all } m\ge0. \end{align*} $$

The sequences

![]() $\vec c$

and

$\vec c$

and

![]() $\vec t$

are determined by

$\vec t$

are determined by

![]() $(\vec x,\vec {y}\hspace {1pt})$

uniquely.

$(\vec x,\vec {y}\hspace {1pt})$

uniquely.

The distinguished Plancherel harmonic function

is obtained from clone Schur functions by setting

![]() $x_k=y_k=k$

,

$x_k=y_k=k$

,

![]() $k\ge 1$

. Throughout the paper we are primarily concerned with two deformations of the Plancherel specialization, of convergent and divergent type, respectively: the shifted Plancherel specialization

$k\ge 1$

. Throughout the paper we are primarily concerned with two deformations of the Plancherel specialization, of convergent and divergent type, respectively: the shifted Plancherel specialization

![]() $x_k=y_k=k+\sigma -1$

,

$x_k=y_k=k+\sigma -1$

,

![]() $\sigma \in [1,\infty )$

, and the Charlier specialization

$\sigma \in [1,\infty )$

, and the Charlier specialization

![]() $x_k=k+\rho -1$

,

$x_k=k+\rho -1$

,

![]() $y_k=k\rho $

,

$y_k=k\rho $

,

![]() $\rho \in (0,1]$

. In Section 6, we describe other examples of Fibonacci positive specializations, both of divergent and convergent type.

$\rho \in (0,1]$

. In Section 6, we describe other examples of Fibonacci positive specializations, both of divergent and convergent type.

1.3 Stieltjes moment sequences and orthogonal polynomials

As a corollary of the Fibonacci positivity of a specialization

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

, we see that the infinite tridiagonal matrix with the diagonals

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

, we see that the infinite tridiagonal matrix with the diagonals

![]() $(1,1,\ldots )$

,

$(1,1,\ldots )$

,

![]() $(x_1,x_2,\ldots )$

, and

$(x_1,x_2,\ldots )$

, and

![]() $(y_1,y_2,\ldots )$

is totally positive, that is, all its minors which are not identically zero are positive. It is known from [Reference Flajolet28], [Reference Viennot72], [Reference Sokal65], [Reference Pétréolle, Sokal and Zhu59] that totally positive tridiagonal matrices correspond to Stieltjes moment sequences

$(y_1,y_2,\ldots )$

is totally positive, that is, all its minors which are not identically zero are positive. It is known from [Reference Flajolet28], [Reference Viennot72], [Reference Sokal65], [Reference Pétréolle, Sokal and Zhu59] that totally positive tridiagonal matrices correspond to Stieltjes moment sequences

![]() $a_n=\int t^n \unicode{x3bd} (dt)$

,

$a_n=\int t^n \unicode{x3bd} (dt)$

,

![]() $n\ge 0$

, where

$n\ge 0$

, where

![]() $\unicode{x3bd} $

is a Borel measure on

$\unicode{x3bd} $

is a Borel measure on

![]() $[0,\infty )$

. Moreover, the monic polynomials

$[0,\infty )$

. Moreover, the monic polynomials

![]() $P_n(t)$

,

$P_n(t)$

,

![]() $n\ge 0$

, orthogonal with respect to

$n\ge 0$

, orthogonal with respect to

![]() $\unicode{x3bd} $

can be determined directly in terms of the parameters

$\unicode{x3bd} $

can be determined directly in terms of the parameters

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

:

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt})$

:

We refer to Section 7 for a detailed discussion of the connection between total positivity of tridiagonal matrices and Stieltjes moment sequences.

According to the (q-)Askey nomenclature [Reference Koekoek and Swarttouw48], in Section 10 we find several Fibonacci positive specializations whose orthogonal polynomials are (up to a change of variables and parameters):

-

○ Charlier polynomials;

-

○ Type-I Al-Salam–Carlitz polynomials;

-

○ Al-Salam–Chihara polynomials;

-

○ q-Charlier polynomials.

In these cases, we also explicitly determine the orthogonality measures

![]() $\unicode{x3bd} $

. For example, in the Charlier case, the orthogonality measure is simply the Poisson distribution with the parameter

$\unicode{x3bd} $

. For example, in the Charlier case, the orthogonality measure is simply the Poisson distribution with the parameter

![]() $\rho $

. For the Al-Salam–Chihara and q-Charlier polynomials, the Fibonacci positivity enforces the atypical condition

$\rho $

. For the Al-Salam–Chihara and q-Charlier polynomials, the Fibonacci positivity enforces the atypical condition

![]() $q>1$

, in contrast to the usual assumption

$q>1$

, in contrast to the usual assumption

![]() $|q|<1$

in the q-Askey scheme.

$|q|<1$

in the q-Askey scheme.

The shifted Plancherel specialization

![]() $x_k=y_k=k+\sigma -1$

which we consider in Section 11 corresponds to the so-called associated Charlier polynomials [Reference Ismail, Letessier and Valent42], [Reference Ahbli1]. The orthogonality measure

$x_k=y_k=k+\sigma -1$

which we consider in Section 11 corresponds to the so-called associated Charlier polynomials [Reference Ismail, Letessier and Valent42], [Reference Ahbli1]. The orthogonality measure

![]() $\unicode{x3bd} $

in this case is not explicit, but we find its moment generating function (Proposition 11.4). Notably, all orthogonality measures

$\unicode{x3bd} $

in this case is not explicit, but we find its moment generating function (Proposition 11.4). Notably, all orthogonality measures

![]() $\unicode{x3bd} $

related to known orthogonal polynomials turn out to be discrete. However, not all orthogonal polynomial families with discrete measures correspond to Fibonacci positive specializations (for example, Meixner polynomials do not). An open question is whether there exists a family of orthogonal polynomials with a continuous measure that is Fibonacci positive.

$\unicode{x3bd} $

related to known orthogonal polynomials turn out to be discrete. However, not all orthogonal polynomial families with discrete measures correspond to Fibonacci positive specializations (for example, Meixner polynomials do not). An open question is whether there exists a family of orthogonal polynomials with a continuous measure that is Fibonacci positive.

We also find combinatorial interpretations of the Stieltjes moments

![]() $a_n$

associated with Fibonacci positive specializations. There is a rich literature addressing the combinatorics of moments coming from orthogonal polynomials, notably [Reference Wachs and White73], [Reference Zeng74], [Reference Anshelevich4], [Reference Kim, Stanton and Zeng47], [Reference Kasraoui and Zeng46], [Reference Josuat-Vergès and Rubey44], [Reference Corteel, Kim and Stanton20]. Most of the results in Sections 8, 9, and 11 follow from techniques developed in these references. In the case of the Charlier specialization,

$a_n$

associated with Fibonacci positive specializations. There is a rich literature addressing the combinatorics of moments coming from orthogonal polynomials, notably [Reference Wachs and White73], [Reference Zeng74], [Reference Anshelevich4], [Reference Kim, Stanton and Zeng47], [Reference Kasraoui and Zeng46], [Reference Josuat-Vergès and Rubey44], [Reference Corteel, Kim and Stanton20]. Most of the results in Sections 8, 9, and 11 follow from techniques developed in these references. In the case of the Charlier specialization,

![]() $a_n$

is the Bell polynomial in the parameter

$a_n$

is the Bell polynomial in the parameter

![]() $\rho $

(often called the Touchard polynomial)

$\rho $

(often called the Touchard polynomial)

where the sum is over all set partitions

![]() $\pi $

of

$\pi $

of

![]() $\{1, \dots , n\}$

. This example is representative of the general behavior of Stieltjes moments arising from Fibonacci positive specializations of divergent type. We prove the following:

$\{1, \dots , n\}$

. This example is representative of the general behavior of Stieltjes moments arising from Fibonacci positive specializations of divergent type. We prove the following:

Proposition 1.2 (Proposition 9.1)

Let

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt} )$

be a Fibonacci positive specialization of divergent type

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y} \hspace {1pt} )$

be a Fibonacci positive specialization of divergent type

where

![]() $\vec {c}$

and

$\vec {c}$

and

![]() $\vec {\epsilon }$

are sequences of positive real numbers uniquely determined by (4.7) and Corollary 4.9. Then the associated n-th Stieltjes moment is given by

$\vec {\epsilon }$

are sequences of positive real numbers uniquely determined by (4.7) and Corollary 4.9. Then the associated n-th Stieltjes moment is given by

As in the Charlier case, the sum is taken over all set partitions

![]() $\pi \in \Pi (n)$

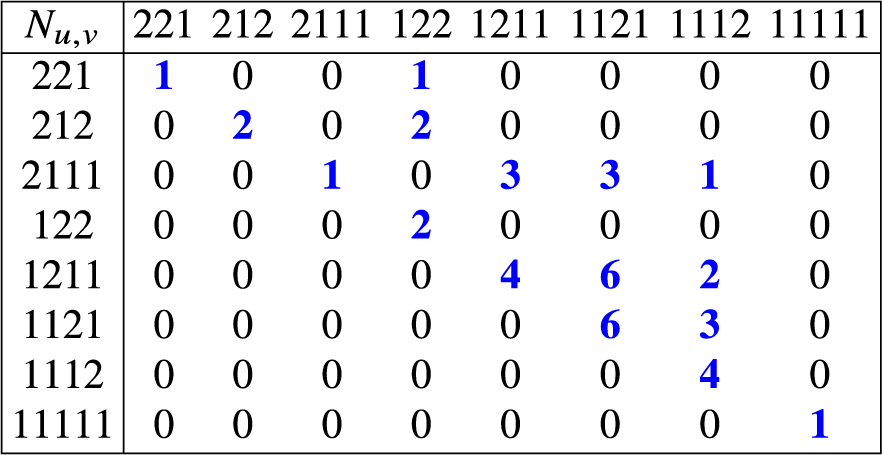

. The statistics

$\pi \in \Pi (n)$

. The statistics

![]() $\ell _k(\pi )$

and

$\ell _k(\pi )$

and

![]() $g_k(\pi )$

are defined in Equation (8.1) and are standard in the analysis of set partitions. Although the shifted-Charlier specialization is Fibonacci positive of convergent type (and not divergent type), its Stieltjes moments nevertheless obey a similar expansion formula involving all set partitions; see Proposition 11.7.

$g_k(\pi )$

are defined in Equation (8.1) and are standard in the analysis of set partitions. Although the shifted-Charlier specialization is Fibonacci positive of convergent type (and not divergent type), its Stieltjes moments nevertheless obey a similar expansion formula involving all set partitions; see Proposition 11.7.

Proposition 8.8 presents an expansion formula for the moments

![]() $a_n$

of a general Borel measure on

$a_n$

of a general Borel measure on

![]() $[0, \infty )$

involving noncrossing set partitions; this result does not require Fibonacci positivity as an assumption. Corollary 8.20 is a compressed version of Proposition 8.8 where

$[0, \infty )$

involving noncrossing set partitions; this result does not require Fibonacci positivity as an assumption. Corollary 8.20 is a compressed version of Proposition 8.8 where

![]() $a_n$

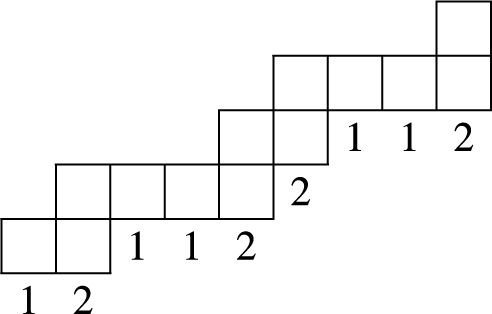

is expressed instead as a sum of monomials indexed by integer compositions of n. This result exhibits an intriguing splitting which can be applied to an integer composition to obtain a unique pair of Fibonacci words; see Definition 8.12.

$a_n$

is expressed instead as a sum of monomials indexed by integer compositions of n. This result exhibits an intriguing splitting which can be applied to an integer composition to obtain a unique pair of Fibonacci words; see Definition 8.12.

While we have a complete description of Fibonacci positive specializations

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y})$

and an understanding of their corresponding moment sequences

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y})$

and an understanding of their corresponding moment sequences

![]() $a_n$

(at least in the divergent case), characterizing their associated Borel measures

$a_n$

(at least in the divergent case), characterizing their associated Borel measures

![]() $\unicode{x3bd} $

within the space of all Borel measures on

$\unicode{x3bd} $

within the space of all Borel measures on

![]() $[0,\infty )$

remains an open problem.

$[0,\infty )$

remains an open problem.

1.4 Asymptotics of random Fibonacci words

We investigate asymptotic behavior of growing random Fibonacci words distributed according to clone coherent probability measures

![]() $M_n$

on

$M_n$

on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_n$

:

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

:

The measures

![]() $M_n$

are called coherent since they are compatible for varying n; see (2.5).

$M_n$

are called coherent since they are compatible for varying n; see (2.5).

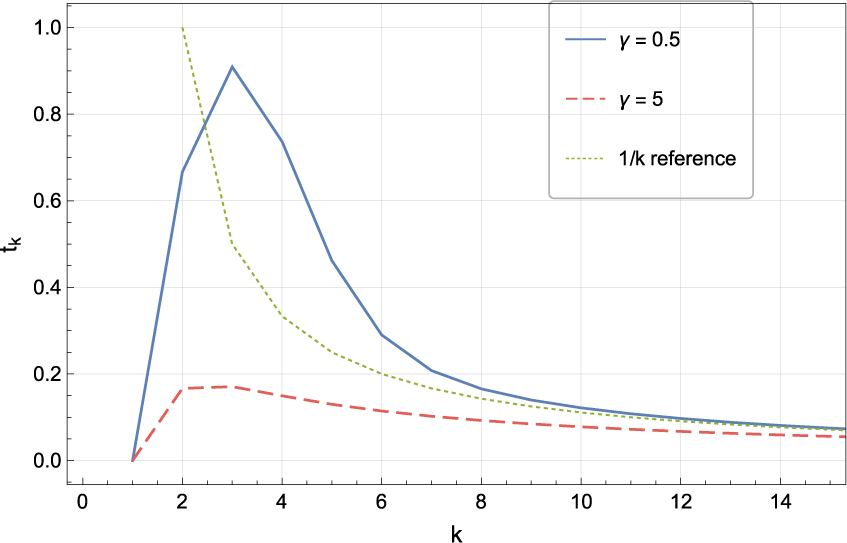

In Sections 13 and 14, we prove two limit theorems concerning the asymptotic behavior of random Fibonacci words under the Charlier and the shifted Plancherel specializations. For the Charlier specialization

![]() $x_k = k + \rho - 1$

,

$x_k = k + \rho - 1$

,

![]() $y_k = k\rho $

(which is of divergent type), we decompose the random word as

$y_k = k\rho $

(which is of divergent type), we decompose the random word as

![]() $w=1^{r_1}21^{r_2}2\ldots $

.

$w=1^{r_1}21^{r_2}2\ldots $

.

Theorem 1.3 (Theorem 13.2)

Fix

![]() $\rho \in (0,1)$

. Let

$\rho \in (0,1)$

. Let

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

be distributed according to the Charlier clone coherent measure

$w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

be distributed according to the Charlier clone coherent measure

![]() $M_n$

. Then for each fixed

$M_n$

. Then for each fixed

![]() $k\ge 1$

, the joint distribution of runs

$k\ge 1$

, the joint distribution of runs

![]() $(r_1(w),\ldots ,r_k(w))$

converges to

$(r_1(w),\ldots ,r_k(w))$

converges to

$$\begin{align*}\frac{r_j(w)}{n - \sum_{i=1}^{j-1}r_i(w)} \xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{d}\eta_{\rho;j}, \qquad j=1,\dots,k, \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\frac{r_j(w)}{n - \sum_{i=1}^{j-1}r_i(w)} \xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{d}\eta_{\rho;j}, \qquad j=1,\dots,k, \end{align*}$$

where

![]() $\eta _{\rho ;1}, \eta _{\rho ;2}, \dots $

are i.i.d. copies of a random variable with the distribution

$\eta _{\rho ;1}, \eta _{\rho ;2}, \dots $

are i.i.d. copies of a random variable with the distribution

This distribution is a convex combination of the point mass at 0 and the Beta random variable

![]() $\mathrm {beta}(1, \rho )$

, with weights

$\mathrm {beta}(1, \rho )$

, with weights

![]() $\rho $

and

$\rho $

and

![]() $1 - \rho $

.

$1 - \rho $

.

Equivalently, we have

![]() $\{r_j/n\}_{j\ge 1}\to X_j$

, where

$\{r_j/n\}_{j\ge 1}\to X_j$

, where

![]() $X_1=U_1$

and

$X_1=U_1$

and

![]() $X_n=(1-U_1)\cdots (1-U_{n-1})U_n$

for

$X_n=(1-U_1)\cdots (1-U_{n-1})U_n$

for

![]() $n\ge 2$

, where

$n\ge 2$

, where

![]() $U_j=\eta _{\rho ;j}$

are i.i.d. The representation of the vector

$U_j=\eta _{\rho ;j}$

are i.i.d. The representation of the vector

![]() $(X_1,X_2,\ldots )$

through the variables

$(X_1,X_2,\ldots )$

through the variables

![]() $U_j$

is called a stick-breaking process.

$U_j$

is called a stick-breaking process.

Note that if

![]() $U_j$

have the distribution

$U_j$

have the distribution

![]() $\mathrm {beta}(1, \theta )$

, then the distribution of the vector

$\mathrm {beta}(1, \theta )$

, then the distribution of the vector

![]() $(X_1,X_2,\ldots )$

is called the Griffiths–Engen–McCloskey distribution

$(X_1,X_2,\ldots )$

is called the Griffiths–Engen–McCloskey distribution

![]() $\mathrm {GEM}(\theta )$

. We refer to [Reference Johnson, Kotz and Balakrishnan43, Chapter 41] for further discussion and applications of GEM distributions, in particular, in population genetics.

$\mathrm {GEM}(\theta )$

. We refer to [Reference Johnson, Kotz and Balakrishnan43, Chapter 41] for further discussion and applications of GEM distributions, in particular, in population genetics.

We see that the runs of

![]() $1$

’s under the Charlier specialization scale to the

$1$

’s under the Charlier specialization scale to the

![]() $\mathrm {GEM}(\rho )$

vector with additional zero entries inserted independently with density

$\mathrm {GEM}(\rho )$

vector with additional zero entries inserted independently with density

![]() $1-\rho $

.

$1-\rho $

.

For the shifted Plancherel specialization

![]() $x_k=y_k=k+\sigma -1$

(which is of convergent type), we decompose the random word as

$x_k=y_k=k+\sigma -1$

(which is of convergent type), we decompose the random word as

![]() $w=2^{h_1}12^{h_2}1\ldots $

. Denote

$w=2^{h_1}12^{h_2}1\ldots $

. Denote

![]() $\tilde h_j=2h_j+1$

.

$\tilde h_j=2h_j+1$

.

Theorem 1.4 (Theorem 14.4)

Fix

![]() $\sigma \ge 1$

. Under the shifted Plancherel clone coherent measure

$\sigma \ge 1$

. Under the shifted Plancherel clone coherent measure

![]() $M_n$

, we have for the joint distribution

$M_n$

, we have for the joint distribution

![]() $(\tilde h_1(w),\ldots ,\tilde h_k(w))$

for each fixed

$(\tilde h_1(w),\ldots ,\tilde h_k(w))$

for each fixed

![]() $k\ge 1$

:

$k\ge 1$

:

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\tilde h_j(w)}{n-\sum_{i=1}^{j-1}\tilde h_i(w)}\xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{d}\xi_{\sigma;j},\qquad j=1,\ldots,k. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \frac{\tilde h_j(w)}{n-\sum_{i=1}^{j-1}\tilde h_i(w)}\xrightarrow[n\to\infty]{d}\xi_{\sigma;j},\qquad j=1,\ldots,k. \end{align*} $$

The joint distribution of

![]() $(\xi _{\sigma ;1},\xi _{\sigma ;2},\ldots )$

can be described as follows. Toss a sequence of independent coins with probabilities of success

$(\xi _{\sigma ;1},\xi _{\sigma ;2},\ldots )$

can be described as follows. Toss a sequence of independent coins with probabilities of success

![]() $1,\sigma ^{-1},\sigma ^{-2},\ldots $

. Let N be the (random) number of successes until the first failure. Then, sample N independent

$1,\sigma ^{-1},\sigma ^{-2},\ldots $

. Let N be the (random) number of successes until the first failure. Then, sample N independent

![]() $\mathrm {beta}(1,\sigma /2)$

random variables. Set

$\mathrm {beta}(1,\sigma /2)$

random variables. Set

![]() $\xi _{\sigma ;k}$

,

$\xi _{\sigma ;k}$

,

![]() $k=1,\ldots ,N $

, to be these random variables, while

$k=1,\ldots ,N $

, to be these random variables, while

![]() $\xi _{\sigma ;k}=0$

for

$\xi _{\sigma ;k}=0$

for

![]() $k>N$

.

$k>N$

.

When

![]() $\sigma>1$

, the random variables

$\sigma>1$

, the random variables

![]() $\xi _{\sigma ;k}$

are not independent, but

$\xi _{\sigma ;k}$

are not independent, but

![]() $\xi _{\sigma ;1},\ldots ,\xi _{\sigma ;n} $

are conditionally independent given

$\xi _{\sigma ;1},\ldots ,\xi _{\sigma ;n} $

are conditionally independent given

![]() $N=n$

. Almost surely, the sequence

$N=n$

. Almost surely, the sequence

![]() $\xi _{\sigma ;1},\xi _{\sigma ;2},\ldots $

contains only finitely many nonzero terms.

$\xi _{\sigma ;1},\xi _{\sigma ;2},\ldots $

contains only finitely many nonzero terms.

At

![]() $\sigma =1$

(Plancherel measure), we have

$\sigma =1$

(Plancherel measure), we have

![]() $N=\infty $

almost surely, so the random variables

$N=\infty $

almost surely, so the random variables

![]() $\xi _{1;k}$

are i.i.d.

$\xi _{1;k}$

are i.i.d.

![]() $\mathrm {beta}(1,\sigma /2)$

. Thus, we recover the convergence to GEM

$\mathrm {beta}(1,\sigma /2)$

. Thus, we recover the convergence to GEM

![]() $(1/2)$

obtained in [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38].

$(1/2)$

obtained in [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38].

Theorems 1.3 and 1.4 follow from product-like formulas for the joint distributions of

![]() $r_j(w)$

and

$r_j(w)$

and

![]() $h_j(w)$

, respectively. The product-like formulas are valid for arbitrary Fibonacci positive specializations, but they greatly simplify in the Charlier and shifted Plancherel cases.

$h_j(w)$

, respectively. The product-like formulas are valid for arbitrary Fibonacci positive specializations, but they greatly simplify in the Charlier and shifted Plancherel cases.

Consider now generic specializations of convergent type with an additional property that the infinite product

![]() $\prod _{i=1}^\infty (1+t_i)$

converges to a finite nonzero value.

$\prod _{i=1}^\infty (1+t_i)$

converges to a finite nonzero value.

Theorem 1.5 (Propositions 15.4 and 15.6)

For a sequence

![]() $\vec t$

of convergent type subject to the assumption above, the behavior of a random word

$\vec t$

of convergent type subject to the assumption above, the behavior of a random word

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

, sampled with respect to the corresponding clone coherent measure, in the limit as

$w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

, sampled with respect to the corresponding clone coherent measure, in the limit as

![]() $n\to \infty $

is as follows:

$n\to \infty $

is as follows:

-

○ either

$w \to 1^\infty $

$w \to 1^\infty $

-

○ or

$w \to 1^\infty 2v$

, where

$w \to 1^\infty 2v$

, where

$v \in \mathbb {YF}$

is a finite random Fibonacci word.

$v \in \mathbb {YF}$

is a finite random Fibonacci word.

That is, the growing word w stabilizes to a random element of the set

Moreover, the distribution

![]() $\mu _{\hspace {0.5pt}\mathrm {I}}$

of the limiting random word

$\mu _{\hspace {0.5pt}\mathrm {I}}$

of the limiting random word

![]() $w\in 1^\infty \mathbb {YF}$

is given by

$w\in 1^\infty \mathbb {YF}$

is given by

$$ \begin{align*} \mu_{\hspace{0.5pt}\mathrm{I}}\left( 1^\infty \right)= \prod_{i=1}^\infty(1+t_i)^{-1}, \qquad \mu_{\hspace{0.5pt}\mathrm{I}}\left( 1^\infty2u \right)= \Bigg( \, \prod_{i \hspace{1pt} = \hspace{1pt} 1}^{|u|-1}(1+t_i) \Bigg) \big(|u|+1 \big)\hspace{1pt} M_{|u|}(u) \hspace{1pt} \frac{B_{\infty}(|u|)}{\prod_{i=1}^{\infty}(1+t_i)}, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mu_{\hspace{0.5pt}\mathrm{I}}\left( 1^\infty \right)= \prod_{i=1}^\infty(1+t_i)^{-1}, \qquad \mu_{\hspace{0.5pt}\mathrm{I}}\left( 1^\infty2u \right)= \Bigg( \, \prod_{i \hspace{1pt} = \hspace{1pt} 1}^{|u|-1}(1+t_i) \Bigg) \big(|u|+1 \big)\hspace{1pt} M_{|u|}(u) \hspace{1pt} \frac{B_{\infty}(|u|)}{\prod_{i=1}^{\infty}(1+t_i)}, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $u\in \mathbb {YF}$

is arbitrary, and

$u\in \mathbb {YF}$

is arbitrary, and

![]() $B_\infty (m)$

,

$B_\infty (m)$

,

![]() $m\ge 0$

, is an infinite series defined below in (4.4). Moreover,

$m\ge 0$

, is an infinite series defined below in (4.4). Moreover,

![]() $\mu _{\hspace {0.5pt}\mathrm {I}}$

is a probability measure on

$\mu _{\hspace {0.5pt}\mathrm {I}}$

is a probability measure on

![]() $1^\infty \mathbb {YF}$

.

$1^\infty \mathbb {YF}$

.

In Corollary 15.7, we obtain the following decomposition of the clone harmonic function

![]() $\varphi _{\vec x, \vec y}$

for specializations of convergent type satisfying

$\varphi _{\vec x, \vec y}$

for specializations of convergent type satisfying

![]() $\prod _{i=1}^\infty (1+t_i)<\infty $

:

$\prod _{i=1}^\infty (1+t_i)<\infty $

:

Here,

![]() $\unlhd $

denotes the partial order on

$\unlhd $

denotes the partial order on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

(induced from the branching relation). The functions

$\mathbb {YF}$

(induced from the branching relation). The functions

![]() $\Phi _{1^\infty }$

and

$\Phi _{1^\infty }$

and

![]() $\Phi _{1^\infty 2u}$

for

$\Phi _{1^\infty 2u}$

for

![]() $v \in \Bbb {YF}$

are called Type-I harmonic functions, and they are extremal.

$v \in \Bbb {YF}$

are called Type-I harmonic functions, and they are extremal.

1.5 Clone Cauchy identities and random permutations

In Section 3, we derive clone Cauchy identities generalizing the classical Cauchy-type summation formulas for the usual Schur functions. Two identities are presented in Propositions 3.8 and 3.9, with the second being

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{|w| = n} s_w (\vec{p} \,|\, \vec{q}\hspace{1pt}) \hspace{1pt} s_w (\vec{x} \,|\, \vec{y}\hspace{1pt}) = \det \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} \mathrm{A}_1 & \mathrm{B}_1 & \mathrm{C}_1 & 0 & \cdots \\ 1 & \mathrm{A}_2 & \mathrm{B}_2 & \mathrm{C}_2 & \\ 0 & 1 & \mathrm{A}_3 & \mathrm{B}_3 & \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & \mathrm{A}_4 & \\ \vdots & & & & \ddots \end{pmatrix}}_{n \times n \ \mathrm{quadridiagonal \, matrix}}, \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \sum_{|w| = n} s_w (\vec{p} \,|\, \vec{q}\hspace{1pt}) \hspace{1pt} s_w (\vec{x} \,|\, \vec{y}\hspace{1pt}) = \det \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} \mathrm{A}_1 & \mathrm{B}_1 & \mathrm{C}_1 & 0 & \cdots \\ 1 & \mathrm{A}_2 & \mathrm{B}_2 & \mathrm{C}_2 & \\ 0 & 1 & \mathrm{A}_3 & \mathrm{B}_3 & \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & \mathrm{A}_4 & \\ \vdots & & & & \ddots \end{pmatrix}}_{n \times n \ \mathrm{quadridiagonal \, matrix}}, \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\mathrm {A}_k = p_k x_k$

,

$\mathrm {A}_k = p_k x_k$

,

![]() $\mathrm {B}_k = q_k(x_k x_{k+1} - y_k) + y_k(p_k p_{k+1} - q_k)$

,

$\mathrm {B}_k = q_k(x_k x_{k+1} - y_k) + y_k(p_k p_{k+1} - q_k)$

,

![]() $\mathrm {C}_k = p_k x_k q_{k+1} y_{k+1}$

.

$\mathrm {C}_k = p_k x_k q_{k+1} y_{k+1}$

.

The identity in (1.3) can be used to define clone analogues of Schur measures, extending the framework from harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

. Indeed, when one of the specializations in (1.3) is Plancherel,

$\mathbb {YF}$

. Indeed, when one of the specializations in (1.3) is Plancherel,

![]() $p_k = q_k = k$

, identity (1.3) reduces to the normalizing identity for the clone harmonic function

$p_k = q_k = k$

, identity (1.3) reduces to the normalizing identity for the clone harmonic function

![]() $\varphi _{\vec x, \vec y}$

. For the Young lattice, Schur measures were introduced in [Reference Okounkov55] and generalized to Schur processes (measures on sequences of partitions) in [Reference Okounkov and Reshetikhin57]. They found extensive applications in random matrices, interacting particle systems, random discrete structures like tilings, geometry, and other areas [Reference Okounkov and Pandharipande56], [Reference Okounkov, Reshetikhin, Vafa, Etingof, Retakh and Singer58], [Reference Borodin and Ferrari11], [Reference Borodin and Gorin12], [Reference Borodin and Petrov15], [Reference Corwin and Hammond21]. We leave clone analogues of Schur measures and processes for future work.

$\varphi _{\vec x, \vec y}$

. For the Young lattice, Schur measures were introduced in [Reference Okounkov55] and generalized to Schur processes (measures on sequences of partitions) in [Reference Okounkov and Reshetikhin57]. They found extensive applications in random matrices, interacting particle systems, random discrete structures like tilings, geometry, and other areas [Reference Okounkov and Pandharipande56], [Reference Okounkov, Reshetikhin, Vafa, Etingof, Retakh and Singer58], [Reference Borodin and Ferrari11], [Reference Borodin and Gorin12], [Reference Borodin and Petrov15], [Reference Corwin and Hammond21]. We leave clone analogues of Schur measures and processes for future work.

In Section 16, we introduce ensembles of random permutations and involutions by utilizing the Young–Fibonacci RS correspondence [Reference Nzeutchap53] and positive harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

. In full generality, the distribution of a permutation or involution depends, respectively, on a triplet

$\mathbb {YF}$

. In full generality, the distribution of a permutation or involution depends, respectively, on a triplet

![]() $(\unicode{x3c0} , \varphi , \psi )$

or a couple

$(\unicode{x3c0} , \varphi , \psi )$

or a couple

![]() $(\unicode{x3c0} , \varphi )$

of harmonic functions. We do not treat the general case in the present work, but focus on the clone harmonic / Plancherel random involutions, that is, corresponding to setting

$(\unicode{x3c0} , \varphi )$

of harmonic functions. We do not treat the general case in the present work, but focus on the clone harmonic / Plancherel random involutions, that is, corresponding to setting

![]() $\unicode{x3c0} = \varphi _{\vec x, \vec y}$

and

$\unicode{x3c0} = \varphi _{\vec x, \vec y}$

and

![]() $\varphi = \varphi _{{}_{\mathrm {PL}}}$

, where

$\varphi = \varphi _{{}_{\mathrm {PL}}}$

, where

![]() $(\vec x, \vec y)$

is a Fibonacci positive specialization. Using clone Cauchy identities, in Section 17 we find the moment generating function for the number of two-cycles in a random involution

$(\vec x, \vec y)$

is a Fibonacci positive specialization. Using clone Cauchy identities, in Section 17 we find the moment generating function for the number of two-cycles in a random involution

![]() $\boldsymbol {\unicode{x3c3}} \in \mathfrak {S}_n$

(Proposition 17.1):

$\boldsymbol {\unicode{x3c3}} \in \mathfrak {S}_n$

(Proposition 17.1):

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}\big[ \tau^{\# \hspace{1pt} \mathrm{two \text{-} cycles}(\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3c3}}) } \big] = (x_1 \cdots x_n)^{-1} \hspace{1pt} \det \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} x_1 &(1 - \tau ) y_1 & - \tau x_1 y_2 &0 &\cdots \\ 1 &x_2 &(1 - 2 \tau)y_2 &- 2 \tau x_2 y_3 & \\ 0 &1 &x_3 &(1 - 3 \tau )y_3 & \\ 0 &0 &1 &x_4 & \\ \vdots & & & &\ddots \end{pmatrix}}_{n \times n \ \mathrm{quadridiagonal \, matrix}} , \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \operatorname{\mathbb{E}}\big[ \tau^{\# \hspace{1pt} \mathrm{two \text{-} cycles}(\boldsymbol{\unicode{x3c3}}) } \big] = (x_1 \cdots x_n)^{-1} \hspace{1pt} \det \underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} x_1 &(1 - \tau ) y_1 & - \tau x_1 y_2 &0 &\cdots \\ 1 &x_2 &(1 - 2 \tau)y_2 &- 2 \tau x_2 y_3 & \\ 0 &1 &x_3 &(1 - 3 \tau )y_3 & \\ 0 &0 &1 &x_4 & \\ \vdots & & & &\ddots \end{pmatrix}}_{n \times n \ \mathrm{quadridiagonal \, matrix}} , \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $\tau $

is an auxiliary parameter.

$\tau $

is an auxiliary parameter.

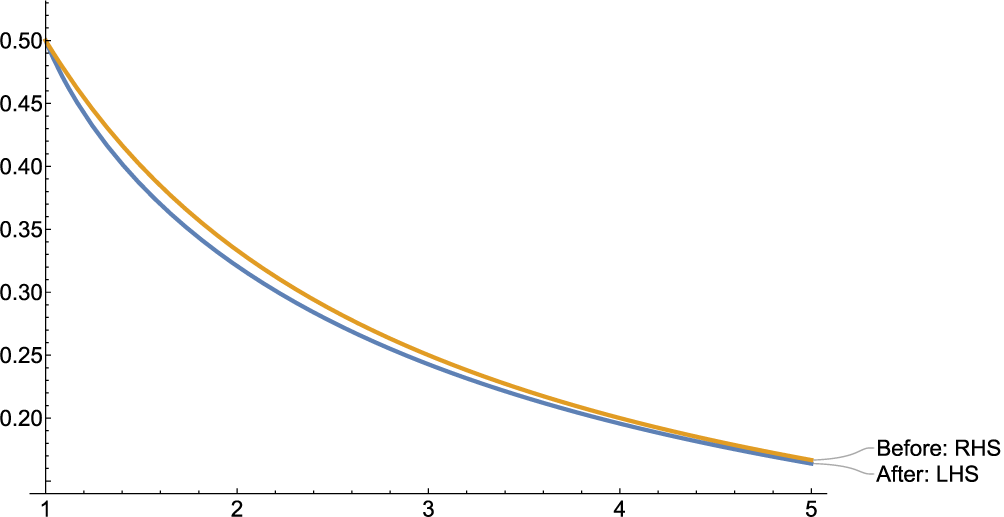

When

![]() $(\vec {x}, \vec {y})$

is the shifted Plancherel specialization (

$(\vec {x}, \vec {y})$

is the shifted Plancherel specialization (

![]() $x_k = y_k = k + \sigma - 1$

,

$x_k = y_k = k + \sigma - 1$

,

![]() $\sigma \in [1,\infty )$

), the Young–Fibonacci shape

$\sigma \in [1,\infty )$

), the Young–Fibonacci shape

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

of a random involution

$w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

of a random involution

![]() $\boldsymbol {\unicode{x3c3}} \in \mathfrak {S}_n$

under the RS correspondence has the same distribution as a random Fibonacci word considered in Theorem 1.4 above. In this way, we can compare the asymptotic behavior of the total number of

$\boldsymbol {\unicode{x3c3}} \in \mathfrak {S}_n$

under the RS correspondence has the same distribution as a random Fibonacci word considered in Theorem 1.4 above. In this way, we can compare the asymptotic behavior of the total number of

![]() $2$

’s in a random Fibonacci word (which is the same as the number of two-cycles), and the scaling limit of initial long sequences of

$2$

’s in a random Fibonacci word (which is the same as the number of two-cycles), and the scaling limit of initial long sequences of

![]() $2$

’s from Theorem 1.4. We establish a law of large numbers (Proposition 17.6) for the total number of

$2$

’s from Theorem 1.4. We establish a law of large numbers (Proposition 17.6) for the total number of

![]() $2$

’s:

$2$

’s:

For

![]() $\sigma> 1$

, this value exceeds the expectation of the sum of the scaled quantities

$\sigma> 1$

, this value exceeds the expectation of the sum of the scaled quantities

![]() $h_j$

in Theorem 1.4. This discrepancy reveals that additional digits of

$h_j$

in Theorem 1.4. This discrepancy reveals that additional digits of

![]() $2$

remain hidden in the growing random Fibonacci word after long sequences of

$2$

remain hidden in the growing random Fibonacci word after long sequences of

![]() $1$

’s. This behavior is unaccounted for in the scaling limit of Theorem 1.4 but contributes to the law of large numbers (1.4).

$1$

’s. This behavior is unaccounted for in the scaling limit of Theorem 1.4 but contributes to the law of large numbers (1.4).

Outline of the paper

The paper is organized into three parts.

In Part I (Sections 2 to 6), we introduce the Young–Fibonacci lattice, the biserial clone Schur functions, and the associated clone coherent measures. We prove the clone Cauchy summation identities, and give a complete characterization of Fibonacci positive specializations of both divergent and convergent type. Representative examples include the shifted Plancherel and Charlier cases that will serve as running examples in later sections.

In Part II (Sections 7 to 11), we develop the link between Fibonacci positivity, total positivity of tridiagonal matrices, and Stieltjes moment sequences. We obtain general combinatorial formulas for moments, identify families of orthogonal polynomials from the (q-)Askey scheme (Charlier, Type-I Al-Salam–Carlitz, Al-Salam–Chihara, q-Charlier), and highlight the atypical

![]() $q>1$

regime enforced by Fibonacci positivity. For these and other specializations, we determine the corresponding discrete Borel orthogonality measures and give explicit combinatorial interpretations of the moments.

$q>1$

regime enforced by Fibonacci positivity. For these and other specializations, we determine the corresponding discrete Borel orthogonality measures and give explicit combinatorial interpretations of the moments.

In Part III (Sections 12 to 17), we study the asymptotic behavior of random Fibonacci words under various Fibonacci positive specializations. Our results include stick-breaking-type limit laws extending the GEM(

![]() $\tfrac 12$

) scaling limit of [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38], new dependent stick-breaking schemes, and the description of extremal components in terms of Type-I harmonic functions in the Martin boundary. We further employ clone Cauchy identities to define and analyze models of random permutations and involutions, computing exact generating functions for cycle statistics and establishing laws of large numbers.

$\tfrac 12$

) scaling limit of [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38], new dependent stick-breaking schemes, and the description of extremal components in terms of Type-I harmonic functions in the Martin boundary. We further employ clone Cauchy identities to define and analyze models of random permutations and involutions, computing exact generating functions for cycle statistics and establishing laws of large numbers.

The paper concludes in Section 18 with a discussion of possible extensions and open problems.

Reading guide

Parts II and III are largely independent and can be read in either order after Part I. Readers primarily interested in the asymptotic behavior of random Fibonacci words (like the scaling limit in Theorem 13.2) may proceed directly to Part III after reading Part I, specifically Sections 2, 4 and 6 for the necessary background and definitions.

Part I Young–Fibonacci lattice and Fibonacci positivity

In this part we recall, and when necessary introduce, the principal objects of our study: the Young-Fibonacci lattice

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

, the clone Schur functions, and the clone coherent measures on Fibonacci words. We then characterize those specializations of the clone Schur functions that give rise to positive harmonic functions on

$\mathbb {YF}$

, the clone Schur functions, and the clone coherent measures on Fibonacci words. We then characterize those specializations of the clone Schur functions that give rise to positive harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

. Finally, we present several examples of Fibonacci positive specializations, including the ones whose asymptotics we analyze in Part III.

$\mathbb {YF}$

. Finally, we present several examples of Fibonacci positive specializations, including the ones whose asymptotics we analyze in Part III.

2 Young–Fibonacci lattice and clone Schur functions

In this preliminary section we review the Young–Fibonacci lattice

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

(also referred to as the Young–Fibonacci branching graph) [Reference Fomin33], [Reference Stanley67], [Reference Goodman and Kerov40] and the clone Schur functions introduced in [Reference Okada54]. The biserial clone Schur functions are harmonic on

$\mathbb {YF}$

(also referred to as the Young–Fibonacci branching graph) [Reference Fomin33], [Reference Stanley67], [Reference Goodman and Kerov40] and the clone Schur functions introduced in [Reference Okada54]. The biserial clone Schur functions are harmonic on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

, and we use them to define coherent probability measures on Fibonacci words.

$\mathbb {YF}$

, and we use them to define coherent probability measures on Fibonacci words.

2.1 Young–Fibonacci lattice and harmonic functions

A Fibonacci word

![]() $w=w_1\ldots w_\ell $

is any binary word with letters

$w=w_1\ldots w_\ell $

is any binary word with letters

![]() $w_j\in \left \{ 1,2 \right \}$

. The integer

$w_j\in \left \{ 1,2 \right \}$

. The integer ![]() is called the weight of the word w. The total number of Fibonacci words of weight n is equal to the n-th Fibonacci number,Footnote 1

hence the name. Denote the set of all Fibonacci words of weight n by

is called the weight of the word w. The total number of Fibonacci words of weight n is equal to the n-th Fibonacci number,Footnote 1

hence the name. Denote the set of all Fibonacci words of weight n by

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_{n}$

, where

$\mathbb {YF}_{n}$

, where

![]() $n\ge 0$

.

$n\ge 0$

.

Definition 2.1. The Young–Fibonacci lattice

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

is the union of all sets

$\mathbb {YF}$

is the union of all sets

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_{n}$

,

$\mathbb {YF}_{n}$

,

![]() $n\ge 0$

. In this lattice,

$n\ge 0$

. In this lattice,

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

is connected to

$w\in \mathbb {YF}_n$

is connected to

![]() $w'\in \mathbb {YF}_{n+1}$

if and only if

$w'\in \mathbb {YF}_{n+1}$

if and only if

![]() $w'$

can be obtained from w by one of the following three operations:

$w'$

can be obtained from w by one of the following three operations:

-

F1.

$w'=1w$

.

$w'=1w$

. -

F1.

$w'=2^{k+1}v$

if

$w'=2^{k+1}v$

if

$w=2^k1v$

for some

$w=2^k1v$

for some

$k\ge 0$

and an arbitrary Fibonacci word v.

$k\ge 0$

and an arbitrary Fibonacci word v. -

F1.

$w'=2^\ell 1 2^{k-\ell }v$

if

$w'=2^\ell 1 2^{k-\ell }v$

if

$w=2^kv$

for some

$w=2^kv$

for some

$k\ge 1$

and an arbitrary Fibonacci word v. While F1 and F2 each generate at most one edge, this rule generates k edges indexed by

$k\ge 1$

and an arbitrary Fibonacci word v. While F1 and F2 each generate at most one edge, this rule generates k edges indexed by

$\ell =1,\ldots ,k$

.

$\ell =1,\ldots ,k$

.

We denote this relation by

![]() $w\nearrow w'$

(equivalently,

$w\nearrow w'$

(equivalently,

![]() $w'\searrow w$

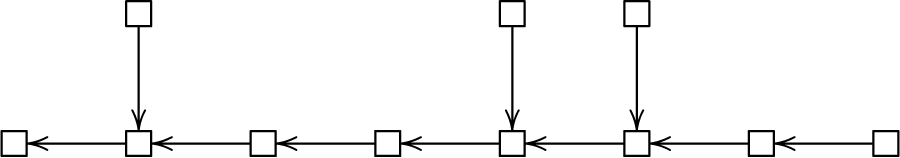

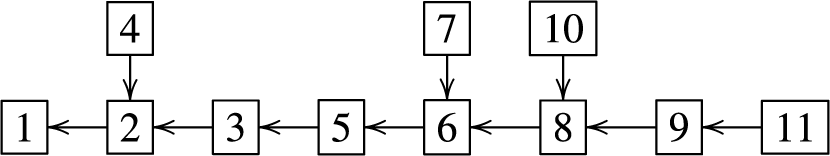

). An example of the Young–Fibonacci lattice up to level

$w'\searrow w$

). An example of the Young–Fibonacci lattice up to level

![]() $n=5$

is given in Figure 1.

$n=5$

is given in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The Young–Fibonacci lattice up to level

![]() $n=5$

.

$n=5$

.

Definition 2.2. A function

![]() $\varphi $

on

$\varphi $

on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

is called harmonic if it satisfies

$\mathbb {YF}$

is called harmonic if it satisfies

A harmonic function is called normalized if

![]() $\varphi (\varnothing )=1$

.

$\varphi (\varnothing )=1$

.

For

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}$

, denote by

$w\in \mathbb {YF}$

, denote by

![]() $\dim (w)$

the number of oriented paths (also known as saturated chains) from

$\dim (w)$

the number of oriented paths (also known as saturated chains) from

![]() $\varnothing $

to w in the Young–Fibonacci lattice. Let

$\varnothing $

to w in the Young–Fibonacci lattice. Let

![]() $I_2(w)$

be the sequence of all positions of the letter 2 in w, reading from left to right. Then

$I_2(w)$

be the sequence of all positions of the letter 2 in w, reading from left to right. Then

Equivalently,

![]() $\dim (w)$

obeys the following recursion:

$\dim (w)$

obeys the following recursion:

$$ \begin{align} \dim(w) \, = \, \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } w = \varnothing ;\\ \dim(v), & \text{if } w = 1v \text{ for a Fibonacci word } v ;\\ (|v| + 1) \dim(v), & \text{if } w = 2v \text{ for a Fibonacci word } v. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \dim(w) \, = \, \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } w = \varnothing ;\\ \dim(v), & \text{if } w = 1v \text{ for a Fibonacci word } v ;\\ (|v| + 1) \dim(v), & \text{if } w = 2v \text{ for a Fibonacci word } v. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

For example, if

![]() $w=22121$

, then

$w=22121$

, then

![]() $I_2(w)=( 1,2,4 )$

, and

$I_2(w)=( 1,2,4 )$

, and

![]() $\dim w=70$

. Since

$\dim w=70$

. Since

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

is a

$\mathbb {YF}$

is a

![]() $1$

-differential poset, we have [Reference Stanley67, Corollary 3.9], (see also [Reference Fomin29]):

$1$

-differential poset, we have [Reference Stanley67, Corollary 3.9], (see also [Reference Fomin29]):

With any nonnegative normalized harmonic function we can associate a family of probability measures

![]() $M_n$

on

$M_n$

on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_n$

as follows:

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

as follows:

The fact that

![]() $\sum _{w\in \mathbb {YF}_n} M_n(w)=1$

follows from the normalization of

$\sum _{w\in \mathbb {YF}_n} M_n(w)=1$

follows from the normalization of

![]() $\varphi $

, and the harmonicity of

$\varphi $

, and the harmonicity of

![]() $\varphi $

translates into the coherence property of the measures

$\varphi $

translates into the coherence property of the measures

![]() $M_n$

:

$M_n$

:

$$ \begin{align} M_n(w)=\sum_{w'\colon w'\searrow w} M_{n+1}(w')\hspace{1pt} \frac{\dim (w)}{\dim (w')}, \qquad w\in \mathbb{YF}_n. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} M_n(w)=\sum_{w'\colon w'\searrow w} M_{n+1}(w')\hspace{1pt} \frac{\dim (w)}{\dim (w')}, \qquad w\in \mathbb{YF}_n. \end{align} $$

The set of all nonnegative normalized harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

forms a simplex

$\mathbb {YF}$

forms a simplex

![]() $\Upsilon (\mathbb {YF})$

. The set of extreme points of this simplex (the ones not expressible as a nontrivial convex combination of other points) is denoted by

$\Upsilon (\mathbb {YF})$

. The set of extreme points of this simplex (the ones not expressible as a nontrivial convex combination of other points) is denoted by

![]() $\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

. In general,

$\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

. In general,

![]() $\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

is a subset of the Martin boundary, denoted by

$\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

is a subset of the Martin boundary, denoted by

![]() $\Upsilon _{\mathrm {Martin}}(\mathbb {YF})$

. The latter consists of harmonic functions which can be obtained by finite rank approximation. The Martin boundary of the Young–Fibonacci lattice is described in [Reference Goodman and Kerov40]. Recently, it was shown in the preprints [Reference Bochkov and Evtushevsky10], [Reference Evtushevsky26] that the Martin boundary coincides with the set of extreme points

$\Upsilon _{\mathrm {Martin}}(\mathbb {YF})$

. The latter consists of harmonic functions which can be obtained by finite rank approximation. The Martin boundary of the Young–Fibonacci lattice is described in [Reference Goodman and Kerov40]. Recently, it was shown in the preprints [Reference Bochkov and Evtushevsky10], [Reference Evtushevsky26] that the Martin boundary coincides with the set of extreme points

![]() $\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

.

$\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

.

For any coherent family of measures

![]() $M_n$

on

$M_n$

on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_n$

,

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

,

![]() $n=0,1,2,\ldots $

, there exists a unique probability measure

$n=0,1,2,\ldots $

, there exists a unique probability measure

![]() $\mu $

on

$\mu $

on

![]() $\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

such that

$\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

such that

Here

![]() $\varphi _\omega $

is the extremal harmonic function corresponding to

$\varphi _\omega $

is the extremal harmonic function corresponding to

![]() $\omega \in \Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

.

$\omega \in \Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

.

2.2 Plancherel measure and its scaling limit

An important example of a harmonic function on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

is the Plancherel function defined as

$\mathbb {YF}$

is the Plancherel function defined as

In [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] it is shown that

![]() $\varphi _{{}_{\mathrm {PL}}}$

belongs to

$\varphi _{{}_{\mathrm {PL}}}$

belongs to

![]() $\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

. Moreover, for the Plancherel measure

$\Upsilon _{\mathrm {ext}}(\mathbb {YF})$

. Moreover, for the Plancherel measure

![]() $M_n(w)=\dim ^2 (w)/n!$

corresponding to

$M_n(w)=\dim ^2 (w)/n!$

corresponding to

![]() $\varphi _{{}_{\mathrm {PL}}}$

as in (2.4), [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] establishes a

$\varphi _{{}_{\mathrm {PL}}}$

as in (2.4), [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] establishes a

![]() $n\to \infty $

scaling limit theorem for the positions of the

$n\to \infty $

scaling limit theorem for the positions of the

![]() $1$

’s in the random Fibonacci word w which we now describe.

$1$

’s in the random Fibonacci word w which we now describe.

Represent

![]() $w\in \mathbb {YF}$

as a sequence of contiguous blocks of letters 2 separated by 1’s. For example,

$w\in \mathbb {YF}$

as a sequence of contiguous blocks of letters 2 separated by 1’s. For example,

![]() $w=122112=(1)(221)(1)(2)$

. Each block except possibly the rightmost one contains exactly one 1, which is its terminating letter. Denote by

$w=122112=(1)(221)(1)(2)$

. Each block except possibly the rightmost one contains exactly one 1, which is its terminating letter. Denote by

![]() $\tilde {h}_1, \tilde {h}_2, \ldots $

the sequence of weights of the blocks, reading from left to right. For the example above,

$\tilde {h}_1, \tilde {h}_2, \ldots $

the sequence of weights of the blocks, reading from left to right. For the example above,

![]() $\tilde {h}_1=1, \tilde {h}_2=5, \tilde {h}_3=1, \tilde {h}_4=2$

, and

$\tilde {h}_1=1, \tilde {h}_2=5, \tilde {h}_3=1, \tilde {h}_4=2$

, and

![]() $\tilde {h}_j=0$

for

$\tilde {h}_j=0$

for

![]() $j\ge 5$

. We have

$j\ge 5$

. We have

![]() $\tilde {h}_1+\tilde {h}_2+\ldots =n$

.

$\tilde {h}_1+\tilde {h}_2+\ldots =n$

.

Definition 2.3. The GEM (Griffiths–Engen–McCloskey) distribution with parameter

![]() $\theta>0$

(denoted

$\theta>0$

(denoted

![]() $\mathrm {GEM}(\theta )$

) is a probability measure on the infinite-dimensional simplex

$\mathrm {GEM}(\theta )$

) is a probability measure on the infinite-dimensional simplex

obtained from the residual allocation model (also called the stick-breaking construction) as follows. By definition, a random point

![]() $X=(X_1,X_2,\ldots )\in \Delta $

under

$X=(X_1,X_2,\ldots )\in \Delta $

under

![]() $\mathrm {GEM}(\theta )$

is distributed as

$\mathrm {GEM}(\theta )$

is distributed as

where

![]() $U_1,U_2,\ldots $

are independent

$U_1,U_2,\ldots $

are independent

![]() $\mathrm {beta(1,\theta )}$

random variables (i.e., with density

$\mathrm {beta(1,\theta )}$

random variables (i.e., with density

![]() $\theta (1-u)^{\theta -1}$

on the unit segment

$\theta (1-u)^{\theta -1}$

on the unit segment

![]() $[0,1]$

). We refer to [Reference Johnson, Kotz and Balakrishnan43, Chapter 41] for further discussion and applications of GEM distributions.

$[0,1]$

). We refer to [Reference Johnson, Kotz and Balakrishnan43, Chapter 41] for further discussion and applications of GEM distributions.

Theorem 5.1 in [Reference Gnedin and Kerov38] establishes the convergence in distribution as

![]() $n\to \infty $

:

$n\to \infty $

:

$$ \begin{align} \left( \frac{\tilde{h}_1(w)}{n}, \frac{\tilde{h}_2(w)}{n}, \ldots \right) \longrightarrow X=(X_1,X_2,\ldots ), \qquad X\sim \mathrm{GEM}(1/2), \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \left( \frac{\tilde{h}_1(w)}{n}, \frac{\tilde{h}_2(w)}{n}, \ldots \right) \longrightarrow X=(X_1,X_2,\ldots ), \qquad X\sim \mathrm{GEM}(1/2), \end{align} $$

where

![]() $\tilde {h}_j(w)$

are the block sizes (described above) of the random Fibonacci word w distributed according to the Plancherel measure on

$\tilde {h}_j(w)$

are the block sizes (described above) of the random Fibonacci word w distributed according to the Plancherel measure on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}_n$

. One of the aims of the present paper is to extend this scaling limit result to a wider class of harmonic functions on

$\mathbb {YF}_n$

. One of the aims of the present paper is to extend this scaling limit result to a wider class of harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

arising from the constructions in Section 2.3 below.

$\mathbb {YF}$

arising from the constructions in Section 2.3 below.

2.3 Harmonic functions from clone Schur functions

A rich family of nonextremal harmonic functions on

![]() $\mathbb {YF}$

comes from clone Schur functions [Reference Okada54] which we now describe. Let

$\mathbb {YF}$

comes from clone Schur functions [Reference Okada54] which we now describe. Let

![]() $\vec x=(x_1,x_2,\ldots )$

and

$\vec x=(x_1,x_2,\ldots )$

and