Introduction

Collagen is the most abundant structural protein in animals. In humans, it constitutes approximately 30% of total body protein and is found in the extracellular matrix of all connective tissues (skin, tendons, bones, cartilage, ligaments, cornea and blood vessels)(Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1–Reference Kirmse, Hein and Schäfer4). The main animal collagen sources, particularly for type I collagen, include land mammals such as pigs, cows and sheep(Reference Steele5–Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7). However, cultural, religious and health constraints (for example, immune reactions and zoonosis) can, in some cases, reduce the applicability of mammalian-derived collagen. For this reason, marine organisms, including fish, jellyfish and sponges, are attracting increasing scientific and industrial attention as a good alternative for obtaining collagen in the healthcare sectors(Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1,Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7–Reference Li9) . Structurally, although marine collagen is highly homologous to terrestrial collagen, it contains a lower molecular weight, which can significantly improve digestion and absorption(Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7) .

Collagen is composed of three polypeptide chains (α helices) that intertwine to create a triple helix structure. Each α chain contains approximately 1000 amino acids and is characterised by a repeating pattern known as Gly-X-Y; X and Y correspond frequently to the amino acids proline and hydroxyproline(Reference Wang2,Reference Gelse, Pöschl and Aigner10,Reference Khatri, Naughton and Clifford11) . Glycine plays a crucial role in stabilising the three α helices, while proline and hydroxyproline have a fundamental role in maintaining the structural integrity of the triple helical structure under physiological conditions, forming hydrogen bonds that prevent free rotation(Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1,Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Soutelino, Rocha and de Oliveira12) . Twenty-nine types of collagens have been identified in chronological order (I–XXIX), with type I collagen being the most abundant, representing 80–85% of total collagen in the human body(Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3). Collagen types differ in their molecular and supramolecular composition, organisation, function and tissue distribution(Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1,Reference Steele5,Reference Gelse, Pöschl and Aigner10) .

Collagen can be partially hydrolysed by denaturation (thermal or chemical) as the hydrogen bonds that stabilise the triple helix can be broken, transforming collagen into gelatine(Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13) . The subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis of gelatine degrades it into short-chain bioactive peptides and amino acids (molecular weight ≤10 kDa, usually 3–6 kDa), turning it into collagen hydrolysate (CH), thus, improving the functional properties of collagen(Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13) , since it has a higher water solubility that facilitates digestion and absorption within the intestinal barrier before entering the bloodstream(Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7,Reference Khatri, Naughton and Clifford11,Reference Kviatkovsky, Hickner and Ormsbee14) . Contrary to earlier assumptions that CH is fully degraded to single amino acids for protein synthesis, current evidence demonstrates that bioactive di- and tripeptides also enter the bloodstream after ingestion(Reference Kleinnijenhuis, van Holthoon and Maathuis15,Reference Virgilio, Schön and Mödinger16) . These peptides are transported across the intestinal epithelium via the PepT1 system(Reference Spanier and Rohm17), enabling CH to deliver bioactive molecules capable of modulating physiological functions beyond basic nutrition. Recent findings have clarified that these Hyp-containing peptides are rapidly absorbed but exhibit transient systemic availability. For example, prolyl-hydroxyproline (Pro-Hyp) reaches its peak plasma concentration within approximately 1·2 h and maximal urinary excretion within 2 h, while most Hyp-containing peptides show similar kinetics, with peaks within 0·5–2 h followed by a rapid decline(Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7). These data confirm that collagen-derived peptides are bioavailable, although their systemic persistence is brief. Crucially, collagen-derived peptides exert unique biological activities that free amino acids cannot replicate. For instance, peptides such as Pro-Hyp and Gly-Pro-Hyp have been shown to stimulate fibroblast proliferation(Reference Asai, Oikawa and Yoshikawa18), enhance extracellular matrix synthesis(Reference Kitakaze, Sakamoto and Kitano19) and promote osteoblast differentiation(Reference Kimira, Ogura and Taniuchi20), thereby supporting skin, joint and bone health, and indicating that absorbed peptides retain biological activity in vivo (Reference Campos, Santos Junior and Pimentel21–Reference Martínez-Puig, Costa-Larrión and Rubio-Rodríguez23). In contrast, individual amino acids are primarily substrates for general protein synthesis and do not trigger these specific signalling or regulatory effects. As an outlook, preclinical encapsulation strategies are being explored to protect peptides from digestion and prolong systemic exposure, potentially improving oral bioavailability(Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7).

Collagen is a versatile biomaterial owing to its availability, bioactivity and biocompatibility with human tissues, as it can interact with cells and extracellular matrices without inducing adverse immune or inflammatory reactions, thereby supporting cellular adhesion, proliferation and tissue regeneration(Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13) . Therefore, it is employed as a supplement in the cosmetic, biomedical, pharmaceutical and food industries(Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1,Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13) . In the food industry, gelatine collagen has been used as a functional component(Reference Jalili, Jalili and Moradi24) thanks to its emulsifying and surface stabilising capacity (good surfactant) and its gelling and viscoelastic behaviour, which allows it to form films and foams by thickening, texturising and retaining water(Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Gomez-Guillen, Gimenez and Lopez-Caballero8,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13,Reference Said25) . In the non-food sector, collagen has gained importance thanks to the following beneficial consequences: high biological compatibility and biodegradability, efficient antigenicity, low allergenicity, and haemostatic activity(Reference Wang2,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13) . Among the various beneficial effects of dietary CS on body health, several studies have found positive evidence regarding arthritis and osteoporosis, skin ageing, joint health and wound healing(Reference Wang2,Reference Tawalbeh, Kha’sim and Mhd Sarbon3,Reference Steele5,Reference Zhou, Jiang and Zhang7,Reference Khatri, Naughton and Clifford11–Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13) . These effects indicate that collagen can improve the structural and functional integrity of connective tissues, particularly those rich in collagen such as bone, cartilage and dermal matrices.

MetS is a multifactorial disorder characterised by a cluster of metabolic abnormalities, including hyperglycaemia/insulin resistance, visceral obesity, atherogenic dyslipidaemia and hypertension, and represents a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D) and other adverse health outcomes(26). MetS affects approximately 12·5–31·4% of adults worldwide and is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, oxidative stress and disturbances in tissue metabolism(Reference Peterseim, Jabbour and Kamath Mulki27). Emerging evidence suggests that collagen-derived peptides may positively influence these pathological processes by modulating extracellular matrix remodelling and adipose tissue function, reducing oxidative stress, improving lipid and glucose metabolism, enhancing insulin sensitivity and supporting intestinal barrier integrity, through mechanisms involving PPAR-α/γ, AMPK, mTOR, DPP-IV and ACE signalling pathways, as well as modulation of gut microbiota and oxidative stress(Reference Giangregorio, Mosconi and Debellis28).

While most mechanistic evidence originates from in vitro and animal studies, a growing number of human trials have begun to explore these associations. However, results remain heterogeneous and, in some cases, inconclusive. Therefore, this narrative review, which includes all the intervention studies performed in human subjects to date, offers an innovative approach and aims to critically integrate mechanistic and clinical evidence on CS and its potential impact on each modifiable risk factor comprising MetS, emphasising translational and public-health relevance. In addition, this work addresses the influence of collagen intake on intestinal dysbiosis, a factor intimately linked to chronic inflammation and oxidative stress in MetS pathophysiology.

Methods

This work was performed as a narrative review designed to provide a critical and integrative overview of the current literature on CS and its relationship with MetS-related dysregulations in humans, contextualised by preclinical (in vitro and animal) mechanistic evidence. Given the heterogeneity and limited number of human clinical trials available, a narrative rather than systematic approach was chosen to enable a broader and mechanism-oriented synthesis, integrating preclinical and clinical findings within a translational and public health framework.

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus using the following keywords, alone or in combination: ‘collagen’, ‘dietary supplements’, ‘body composition’, ‘body weight’, ‘weight loss’, ‘obesity’, ‘overweight’, ‘adiposity’, ‘satiety’, ‘appetite’, ‘hunger’, ‘glucose’, ‘glycemia’, ‘insulin’, ‘type 2 diabetes’, ‘blood pressure’, ‘hypertension’, ‘lipids’, ‘lipoproteins’, ‘triglycerides’, ‘dyslipidaemia’, ‘cholesterol’, ‘atherosclerosis’, ‘cardiovascular disease’, ‘metabolic syndrome’, ‘intestinal microbiota’, ‘dysbiosis’, ‘inflammation’, ‘oxidative stress’, ‘human’. No automated study selection, meta-analysis or quantitative data pooling was performed.

Studies were selected on the basis of conceptual relevance and scientific contribution rather than exhaustive inclusion. Priority was given to human studies published in the last thirty years, while preclinical studies were incorporated to elucidate underlying biological mechanisms and support translational interpretation. This narrative review does not aim to provide a systematic quantitative synthesis but rather to integrate and critically discuss mechanistic and clinical evidence to identify consistent biological pathways and potential therapeutic implications.

References were chosen to highlight key findings and illustrate the biological mechanisms through which collagen may influence MetS-related outcomes.

Figures were created with BioRender.com.

Results and critical discussion

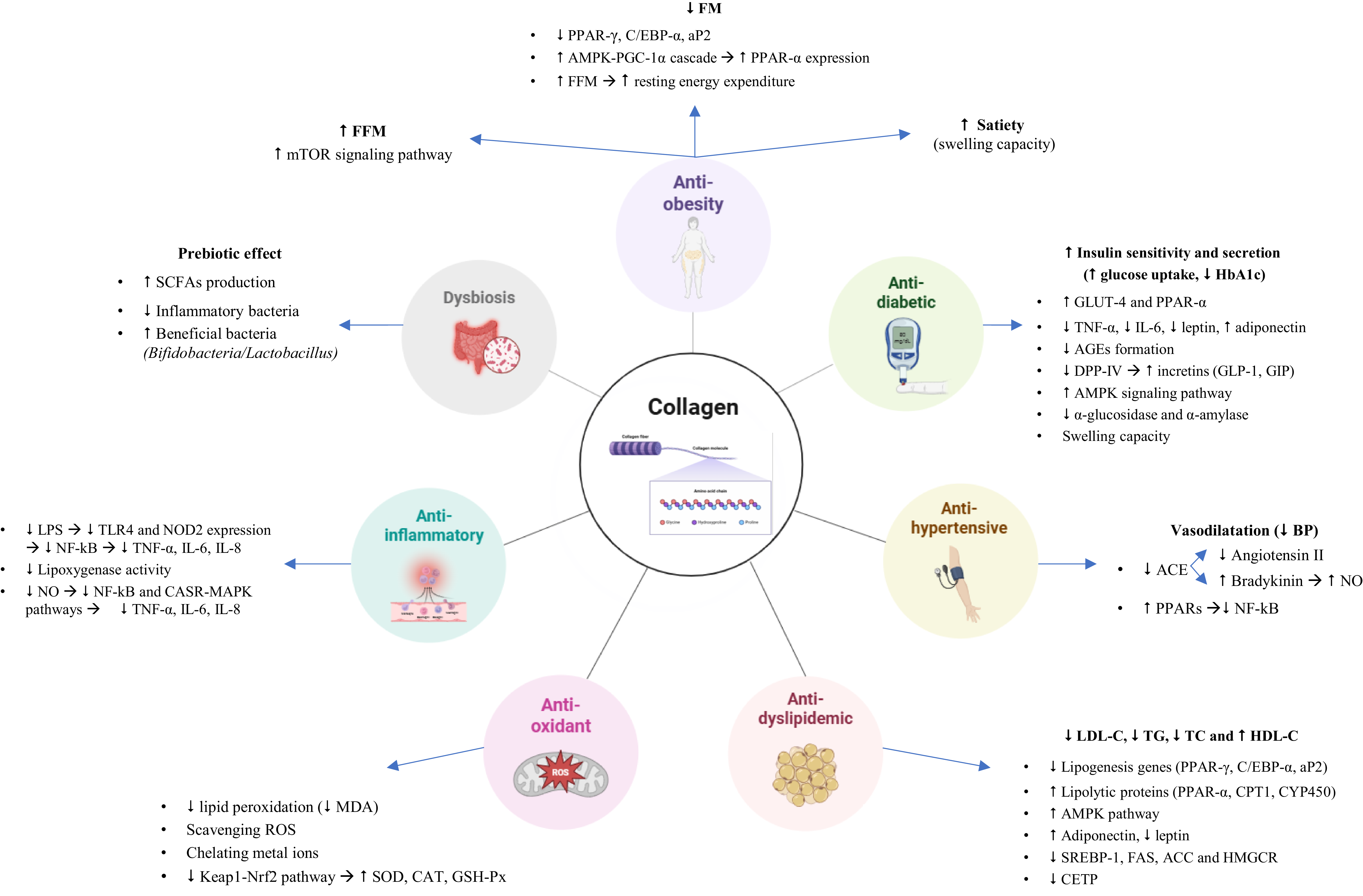

The main beneficial effects of dietary supplementation with collagen for health are represented in Fig. 1 and explained in detail in the next section. We present a narrative synthesis of the evidence by MetS-relevant outcomes, presenting human studies and discussing preclinical mechanisms that may explain or contextualise clinical findings.

Fig. 1 Main beneficial effects of dietary supplementation with collagen, and their mechanisms of action. FM, fat mass; FFM, fat free mass; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; TG, triacylglycerol; TC, total cholesterol; SCFA, short chain fatty acids; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MDA, malondialdehyde; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

Effects of CS on MetS

Anti-obesity effect. Body composition: fat-free mass (FFM) and fat mass (FM)

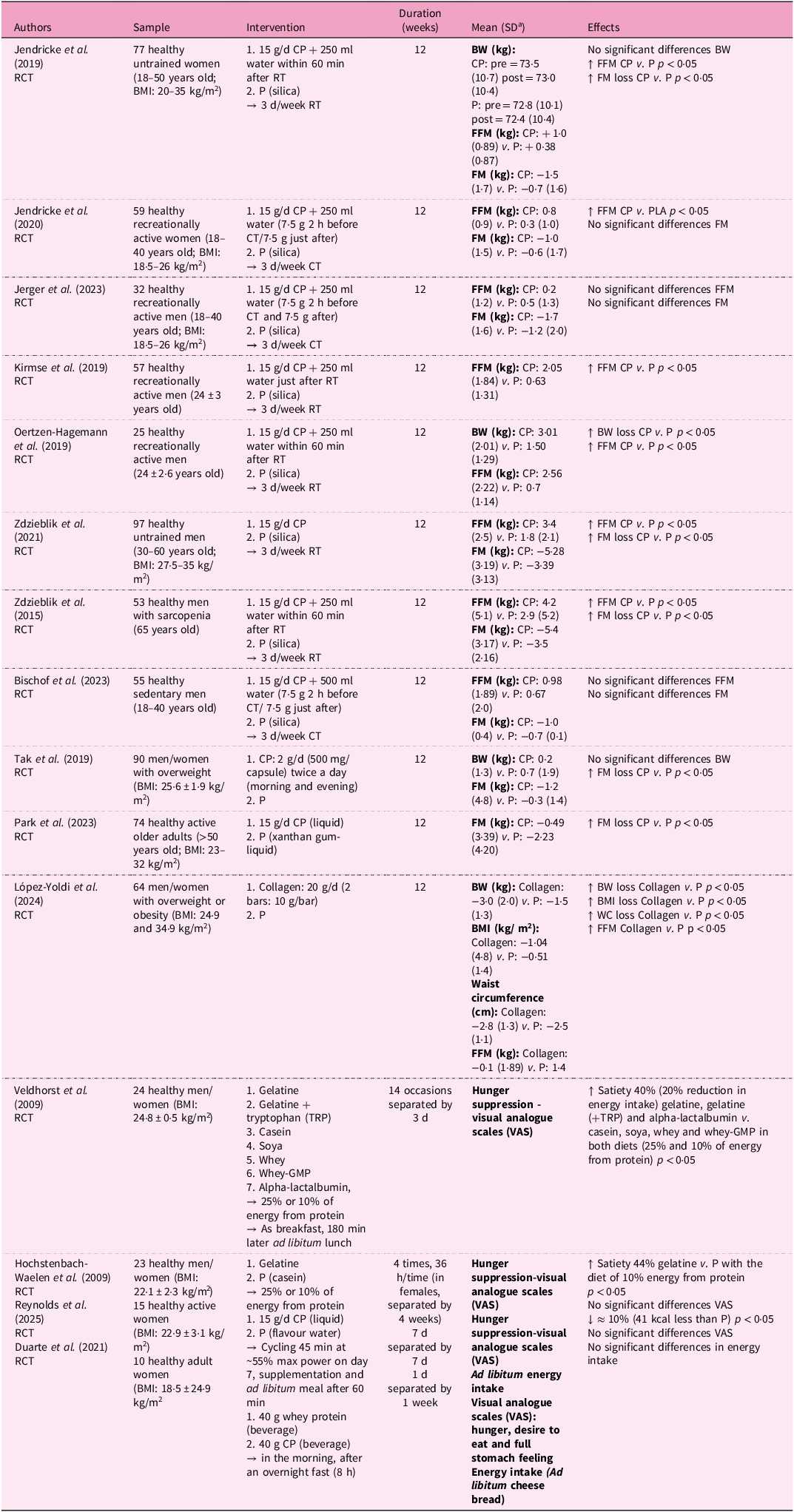

Human clinical trials evaluating the effects of collagen peptide supplementation (CPs) on body composition have yielded heterogeneous results, as summarised in Table 1. Fifteen human studies using CS have been included; in twelve studies the supplement administered was CH, while in the other three it was native collagen or gelatine. Eight of the twelve interventions that administered CH examined the anti-obesity effect of 15 g of CPs (12 weeks) in combination with resistance training (body-weight-specific or barbell and machine training) or concurrent training (body weight exercises combined with running) in healthy adults. Several results indicated significant improvements in FFM and reductions in FM(Reference Jendricke, Centner and Zdzieblik29–Reference Zdzieblik, Jendricke and Oesser34). However, not all trials observed these changes.

Table 1. Nutritional interventions examining the anti-obesity effects of collagen supplementation in humans

a Standard deviation.

RCT, controlled trial; BMI, body mass index; CP, collagen peptides; RT, resistance training; P, placebo; BW, body weight; FFM, fat-free mass; FT, fat mass; CT, concurrent training; WC, waist circumference; TRP, tryptophan; Whey-GMP, whey without glycomacropeptide; VAS, visual analogue scales; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; ↔, equal.

Mechanistic context (preclinical and limited human evidence): potential pathways underlying increases in FFM and muscle mass

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the potential increases in fat-free mass observed in some trials. The muscle mass gain observed with strength training is mainly regulated by the activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTOR), a key modulator of protein synthesis and ultimately of skeletal muscle hypertrophy(Reference Hoppeler35). The changes reported in FFM among the studies included in this work may be supported by the association with this mTOR signalling pathway, activated mainly by branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) such as leucine(Reference Hoppeler35). Hydrolysed collagen has a low concentration of this amino acid but shows high levels of arginine and glycine that also have the ability to stimulate the mTOR cascade(Reference Sun, Wu and Ji36,Reference Liu, Wang and Wu37) . In mouse models, this pathway promotes C2C12 myoblast differentiation and myotube hypertrophy(Reference Kitakaze, Sakamoto and Kitano19).

Despite these observations, evidence for mTOR activation and increased muscle protein synthesis (MPS) in humans is limited. Some trials, such as Jerger et al. and Bischof et al., reported no significant FFM gains, suggesting that responses may depend on training modality, minimal impact of CT on the stimulus needed for hypertrophy, baseline activity, individual variability, participant characteristics, collagen dosage or supplementation duration(Reference Fyfe, Bishop and Stepto38,Reference Murach and Bagley39) . Another potential contributor to FFM is the reinforcement of collagen in the extracellular matrix of muscle and connective tissues, which comprise approximately 10% of muscle tissue(Reference Zdzieblik, Oesser and Baumstark33,Reference Hoppeler35,Reference Turrina, Martínez-González and Stecco40) .

Mechanistic context (human and preclinical): potential pathways underlying reductions in FM

Beyond lean mass, evidence from human observations and animal models points to mechanisms potentially underlying fat mass reductions. The significant increase in FFM enhanced by CPs, given that muscle is one of the most metabolically active tissues, can contribute to reductions in body weight at the expense of FM mainly owing to a greater energy expenditure at rest(Reference Nielsen, Hensrud and Romanski41). Several clinical studies reported significant concomitant increases in FFM and decreases in FM(Reference Jendricke, Centner and Zdzieblik29,Reference Zdzieblik, Oesser and Baumstark33,Reference Zdzieblik, Jendricke and Oesser34) . However, reductions in FM have also been observed independently of FFM gains. For example, Tak et al. and Park et al. reported significant decreases in FM without corresponding increases in FFM, indicating that collagen may influence body composition through additional mechanisms such as modulation of adipose tissue metabolism, satiety and energy balance(Reference Tak, Kim and Lee42,Reference Park, Kim and Shin43) . Other trials, as mentioned before, found no significant changes in FFM or FM, further emphasising the heterogeneity of individual and methodological factors across studies(Reference Jerger, Jendricke and Centner44,Reference Bischof, Stafilidis and Bundschuh45) .

Furthermore, in the context of a long-term exercise programme, FM reductions with CPs can occur independently of FFM gains. CPs have been linked to activation of the AMPK–PGC-1α cascade(Reference Margolis and Pasiakos46). Peroxisome proliferator co-activator-1 α (PGC-1α) signalling is involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and improves fat metabolism(Reference Margolis47). PGC-1α affects the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR), which contains nuclear transcription factors PPAR-α (liver), PPAR-δ (skeletal muscle) and PPAR-γ (adipocytes), that fulfil the function of regulating the expression of genes involved in adipose metabolism such as pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4), phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), adiponectin, perilipin and 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3), among others(Reference Nakamura, Yudell and Loor48,Reference Tometsuka, Koyama and Ishijima49) . Therefore, there is evidence in mouse models suggesting the beneficial effect of CP intake on the function of PGC-1α and PPAR, both involved in fat oxidation(Reference Tometsuka, Koyama and Ishijima49,Reference Woo, Song and Kang50) .

The other clinical trials, among the twelve that analysed the impact of CP administration on body composition, excluded a physical training intervention(Reference Tak, Kim and Lee42,Reference Park, Kim and Shin43) . Park et al. (Reference Park, Kim and Shin43) revealed that 15 g/d of CPs, over 12 weeks, significantly reduced FM in healthy and active older adults, while Tak et al. (Reference Tak, Kim and Lee42) found the same results after 2 g/d of marine CPs in healthy overweight adults. The biological mechanism explaining this anti-obesity effect was previously highlighted in animal studies where obese mice were fed with fish collagen peptides (FCP)(Reference Lee, Hur and Ham51,Reference Astre, Deleruyelle and Dortignac52) . FCP have been reported to inhibit lipid accumulation during the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes into mature adipocytes by suppressing the expression of master adipogenicity transcription factors – PPAR-γ, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha (C/EBP-α) and adipocyte protein 2 (aP2) – which mainly regulate adipocyte differentiation and maintenance, leading to a significant decrease in adipocyte enlargement(Reference Woo, Song and Kang50,Reference Lee, Hur and Ham51) . Moreover, Woo et al. observed increased phosphorylation of 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (p-AMPK) following CP ingestion in male mice(Reference Woo, Song and Kang50). Stimulation of this protein is known to induce fatty acid oxidation and reduce adipocyte differentiation and fatty acid cholesterol synthesis(Reference Lage, Diéguez and Vidal-Puig53).

Importantly, in both the Park et al. (Reference Park, Kim and Shin43) and Tak et al. (Reference Tak, Kim and Lee42) studies, participants were instructed not to change their habitual diet or physical activity patterns during the intervention. While this reduces some confounding from intentional lifestyle changes, the studies did not strictly control energy intake or objectively monitor physical activity, meaning that the observed FM reductions cannot be fully attributed to CPs alone. Moreover, greater fatty acid oxidation does not necessarily translate into fat-mass loss in the absence of an energy deficit. Therefore, although CPs may influence adipocyte metabolism and fatty acid oxidation, these anti-obesity effects should be interpreted cautiously, within the context of overall energy balance, adherence, dietary compensation, training modality and baseline characteristics.

In vitro, a collagen-derived dipeptide, prolyl-hydroxyproline (Pro-Hyp), has been shown to reduce adipocyte size and increase the expression of beige-fat-specific genes, including C/EBPα, PGC-1α and uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1). This upregulation is accompanied by mitochondrial activity, suggesting improved efficiency of brown adipocytes. Further analysis revealed that a Pro-Hyp sequence was identified in the PGC-1α gene promoter, facilitating the binding of the transcription factor FoxG1. This interaction plays a crucial role in regulating PGC-1α transcription, as FoxG1 binds to the AT-rich motif within the PGC-1α promoter, potentially influencing thermogenic gene expression. However, although this in vitro finding reveals a previously unknown regulatory pathway, the mechanisms underlying brown adipocyte differentiation remain unclear(Reference Nomura, Kimira and Kobayashi54).

Five additional experimental studies conducted in humans with native collagen, CP or gelatine examined their impact on body composition through appetite modulation. López-Yoldi et al. demonstrated that, after 3 months of intervention without a hypocaloric diet, supplementation with 20 g/d of technologically modified bovine collagen to absorb water at an acidic pH produced a significant decrease in body weight, BMI and waist circumference, as well as an increase in FFM(Reference López-Yoldi, Riezu-Boj and Abete55).

Similarly, Reynolds et al. recently reported that short-term supplementation with CP (15 g/d for 7 d) in physically active females reduced post-exercise energy intake by about 10%, accompanied by higher glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and insulin levels and lower ghrelin and leptin concentrations, although subjective appetite/satiety ratings did not differ. This lack of visual analogue scale (VAS) change was attributed to the relatively low energy content of the supplement, the transient appetite-suppressive effect of exercise, and the fact that the study, like previous trials, was probably not adequately powered to detect small but statistically significant differences in subjective appetite(Reference Reynolds, Hansell and Thorley56). In agreement, Duarte et al. observed that acute supplementation with hydrolysed collagen increased leptin concentrations compared with whey protein but did not affect subjective appetite ratings in healthy women. This neutral response likely reflects the acute, low-dose design, the low leucine content and biological value of collagen, and limitations in the sensitivity of VAS methods, which together may have attenuated measurable effects on satiety(Reference Duarte, De Freitas and Marini57).

Other studies also demonstrated an appetite-suppressing effect of gelatine compared with other types of protein such as casein, although these effects were mainly attributed to differences in amino-acid composition and gut-peptide responses (for example, GLP-1, PYY, ghrelin) rather than to gastric swelling(Reference Hochstenbach-Waelen, Westerterp-Plantenga and Veldhorst58,Reference Veldhorst, Nieuwenhuizen and Hochstenbach-Waelen59) .

Mechanistic context: satiety and appetite regulation

The mechanisms proposed for collagen-induced appetite modulation may involve both physical and hormonal components. The mechanism proposed by López-Yoldi et al. and demonstrated in vitro involves native collagen with high swelling capacity in the stomach, whose low digestibility and high water-retention capacity enable volumetric expansion under acidic pH, promoting gastric distension and an early feeling of fullness, satiety and satisfaction(Reference López-Yoldi, Riezu-Boj and Abete55).

Nevertheless, CP may modulate appetite via endocrine pathways involving changes in GLP-1, insulin, ghrelin, and leptin, although the direction and magnitude of these effects vary across studies(Reference Reynolds, Hansell and Thorley56,Reference Duarte, De Freitas and Marini57) . Conversely, gelatine appears to act mainly through peptide composition and stimulation of anorexigenic gut hormones(Reference Hochstenbach-Waelen, Westerterp-Plantenga and Veldhorst58,Reference Veldhorst, Nieuwenhuizen and Hochstenbach-Waelen59) . Together, these complementary pathways may explain the appetite-suppressing and weight-regulating potential of CS. Further well-controlled human trials incorporating physiological assessments are warranted to confirm the in vivo relevance of these mechanisms and their long-term clinical implications.

In summary, CPs, particularly when combined with a training programme, may improve body composition by promoting skeletal muscle growth, potentially via the mTOR signalling pathway,(Reference Hoppeler35) and by enhancing lipid metabolism owing to increased PPAR family expression and function(Reference Tometsuka, Koyama and Ishijima49). In the short term, it influences appetite regulation through endocrine responses involving GLP-1, insulin, leptin and ghrelin. However, responses are heterogeneous and largely mechanistic: some studies report FFM gains and FM reductions, whereas others do not. The mechanistic evidence for mTOR-mediated MPS in humans is limited, and reductions in FM should be interpreted cautiously in light of energy intake and potential confounders.

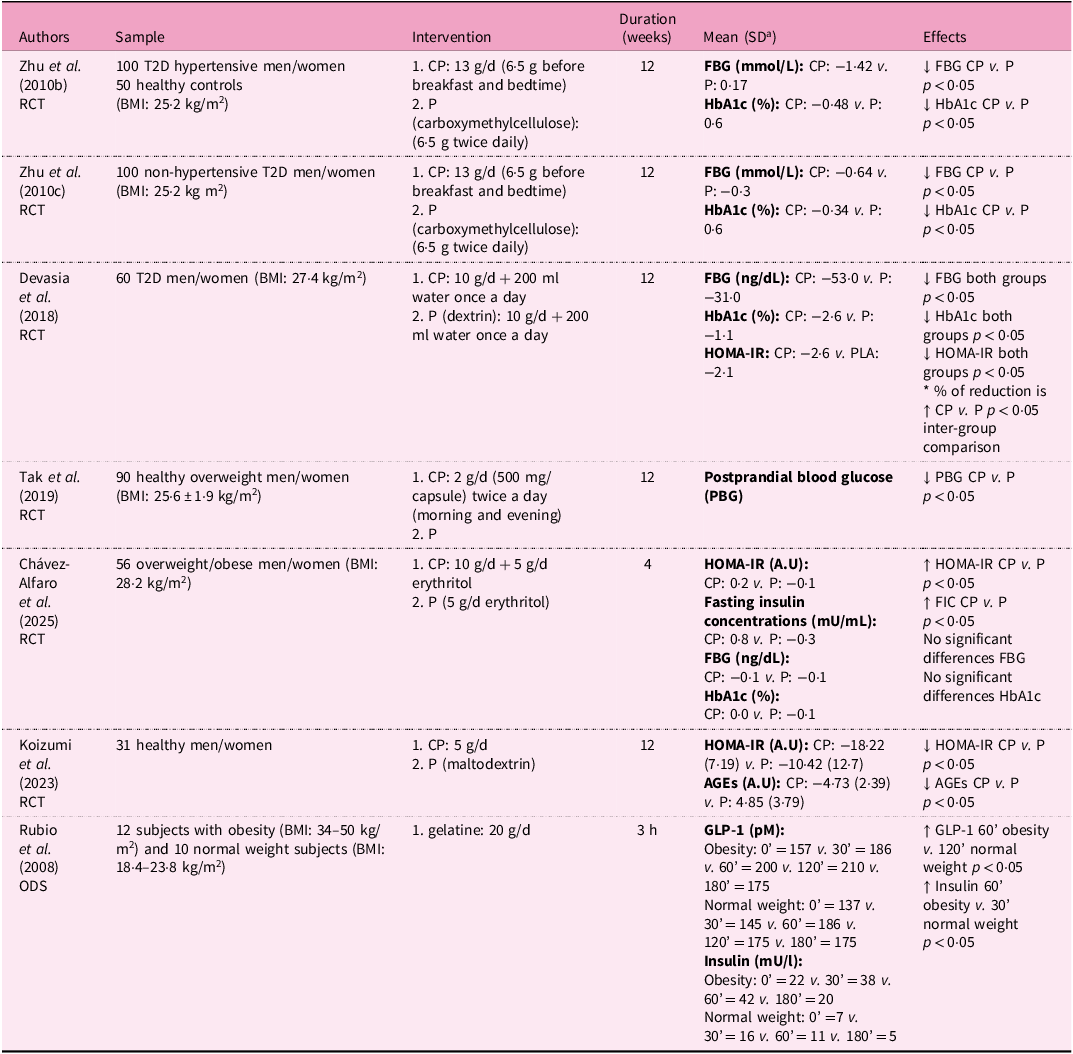

Anti-diabetic effect

Human studies evaluating the effects of CH or gelatine on glycaemic parameters are summarised in Table 2. Zhu et al. conducted two investigations with a daily supplementation of 13 g of CP for 12 weeks in patients with T2D with(Reference Zhu, Li and Peng60) and without hypertension(Reference Zhu, Li and Peng61). In both studies, the results showed an improvement in glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity by reducing fasting glucose and HbA1c in patients with T2D, as suggested by modulation of GLUT4 and PPAR-α expression in the same studies. The same authors conducted a third investigation in both populations (patients with T2D with/without hypertension) with the aim of exploring the biological mechanism underlying the results found in previous studies. Regulation of metabolic nuclear receptors, such as PPAR-α expression, by CP could be the possible mechanism for the observed effects(Reference Zhu, Li and Peng62).

Table 2. Nutritional interventions examining the anti-diabetic effects of collagen supplementation in humans

a Standard deviation.

RCT, controlled trial; T2D, type 2 diabetes mellitus; BMI, body mass index; CP, collagen peptides; P, placebo; FBG, fasting blood glucose; HbA1c, glycosylated haemoglobin; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment ratio; A.U, arbitrary units; PGB, postprandial blood glucose; FIC, fasting insulin concentrations; AGE, advanced glycation end products; ODS, observational-descriptive study; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; ↔, equal.

In contrast, Chávez-Alfaro et al. found that 4 weeks of porcine CP intake did not improve glucose metabolism in non-diabetic subjects, likely because their baseline glucose levels were already within the normal range(Reference Chavez-alfaro, Mensink and Plat63).

Collectively, these clinical findings indicate that while CP may improve glycaemic parameters in individuals with impaired glucose metabolism, benefits in normoglycaemic populations are less evident. These findings highlight that the metabolic benefits of CPs may depend on the metabolic status of participants and underscore the need for further studies in diabetic or prediabetic populations.

Mechanistic context (in vitro and animals): potential pathways underlying improvements in glucose metabolism

Insulin resistance is a primary pathophysiological factor for the development of T2D as a result of the simultaneous implications of a cascade of events including oxidative stress and the activities of GLUT-4 and PPAR-α(Reference Tangvarasittichai64). In preclinical studies, regulation of PPAR-α expression in diabetic rats suggests that marine CP can ameliorate diabetes by improving insulin sensitivity(Reference Zhu, Zhang and Mu65). Woo et al. similarly proposed that high glycine content in collagen has a regulatory effect on some factors related to fat accumulation and energy consumption, such as PPAR-α, -γ, -δ, and uncoupling protein type 2 (UCP2)(Reference Woo, Song and Kang50). Other studies conducted in subjects with T2D showed that CP increased adiponectin and decreased leptin and resistin levels, suggesting an improvement in insulin sensitivity through the regulation of these inflammatory adipocytokines(Reference Woo, Song and Kang50,Reference Affane, Louala and el Imane Harrat66) . In addition, in humans, 5 g/d FCP with high concentrations of prolyl-hydroxyproline (Pro-Hyp) and hydroxyprolyl-glycine (Hyp-Gly) decreased advanced glycation end products (AGE) and homeostatic model assessment (HOMA)-IR levels in thirty-one healthy individuals, suggesting an improvement of insulin resistance and AGE-related disturbances(Reference Koizumi, Okada and Miura67).

Beyond peripheral insulin sensitivity, additional in vitro and animal data point to incretin-mediated mechanisms. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and GLP-1 are incretin hormones responsible for modulating pancreatic insulin secretion in β-cells, thereby, maintaining normal blood glucose levels(Reference Juillerat-Jeanneret68). In this context, a possible explanation for the role of CP in weight management and T2D is based on the downregulation of a glycoprotein located in liver, kidney, small intestine and blood: the dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV)(Reference Devasia, Kumar and Stephena69). DPP-IV cleaves incretins, preventing insulin release. This enzyme acts on the proline or alanine residues in the second position of the N-terminus of polypeptides that bind to the active side of GIP and GLP-1, preventing their function(Reference Cunningham and O’Connor70). In fact, DPP-IV inhibitors increase GIP and GLP-1 activity in the fight against T2D(Reference Drucker and Nauck71). CP with a high proline content have been shown in vitro to inhibit DPP-IV activity(Reference Wang, Yu and Yokoyama72), and in animal models, shown to stimulate GLP-1 secretion(Reference Iba, Yokoi and Eitoku73). In addition, oral administration of CH in mice improved glucose tolerance by reducing intestinal glucose uptake and enhancing insulin secretion, suggesting the possible antidiabetic effect of CP administration(Reference Iba, Yokoi and Eitoku73). However, direct inhibition of DPP-IV by collagen peptides has not yet been demonstrated in humans, and the available human data remain inconclusive.

Complementary animal studies also highlight AMPK activation and gut-microbiota modulation as possible mechanisms. AMPK acts as a kinase and an essential energy sensor to regulate glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. Thus, the phosphorylation and activation of AMPK (p-AMPK) contribute to lower blood glucose levels by modulating key enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis(Reference Hou, Zhao and Fang74). In a T2D mouse model, CP can activate AMPK, promoting glycogen synthesis and leading to a significant reduction in blood glucose and lipid levels, along with a decrease in the abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroides. At the same time, it increased the concentration of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) in the gut microbiota and elevated the serum levels of GLP-1, accompanied by a substantial decrease in HOMA-IR(Reference He, Gao and Ju75). These preclinical findings in mice provide valuable insight into the potential of CPs to alleviate symptoms of T2D.

In vitro findings further indicate that CH may inhibit digestive enzymes such as α-amylase and α-glucosidase(Reference Gaspardi, da Silva and Ponte76). For this reason, the absorption of monosaccharides and, therefore, their presence in the blood is reduced, thus preventing the increase in postprandial glycaemia(Reference Luijpers, Nuijten and Groenhuijzen77). These findings corroborate what was described in Zhang’s previous research, which found that amino acids present in carbohydrates can inhibit these pancreatic enzymes exhibiting a dose-dependent hypoglycaemic effect in diabetic mice supplemented with CP(Reference Zhang, Chen and Jiang78).

In human studies, collagen-derived proteins have been associated with incretin responses. A clinical trial conducted by Rubio et al. found that a simple protein meal containing 20 g of gelatine can elevate GLP-1 levels 30 min after ingestion. The mean plasma GLP-1 level was significantly higher at 60 (normal weight) and 120 min (obesity) compared with baseline levels, with a peak at 120 min in all population, decreasing to baseline values at 180 min. As a consequence, an increase in serum insulin levels was observed, with a significantly higher peak level at 60 min (obesity) and 30 min (normal weight). On the basis of these results, it was assumed that gelatine, as a protein with specific physicochemical properties – similar to those highlighted in discussions of collagen’s anti-obesity effects – can swell and retain large amounts of water in the stomach. This suggests a potential insulinotropic effect mediated by GLP-1(Reference Rubio, Castro and Zanini79). Consistent with these observations, animal models support a GLP-1-mediated glucose-lowering effect of specific CH. H80, a CH capable of enhancing natural GLP-1 secretion, was selected to evaluate its effects on glucose tolerance in lean, normoglycaemic mice, as well as in overweight, prediabetic mice. The data indicated that H80 has significant GLP-1-mediated effects on the primary outcome in lean and prediabetic mice, showing a reduction in blood glucose levels at a dose of 4 g/kg by increasing plasma secretion of active GLP-1. Furthermore, in chronically supplemented prediabetic mice, acute administration of H80 slowed down gastric emptying and increased plasma insulin(Reference Grasset, Briand and Virgilio80).

Taken together, evidence from in vitro, animal and human studies suggests that CP may improve glycaemic control by modulating glucose metabolism, insulin sensitivity and incretin responses(Reference Tak, Kim and Lee42,Reference Zhu, Li and Peng61,Reference Devasia, Kumar and Stephena69,Reference Rubio, Castro and Zanini79) . However, most mechanistic insights derive from preclinical data, and clinical evidence remains limited and heterogeneous.

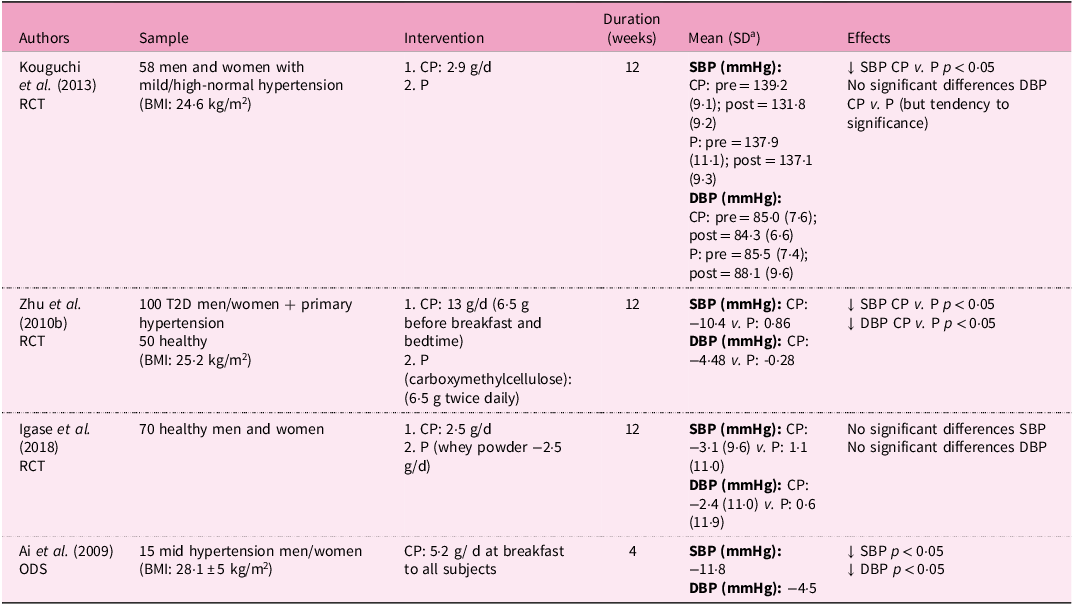

Anti-hypertensive effect: systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP)

Human trials investigating the effects of CP on blood pressure are summarised in Table 3. Four studies (three clinical trials and one observational–descriptive study) have evaluated the effect of CP on SBP and DBP. Kouguchi et al. showed that the administration of 2·9 g/d of CP derived from chicken for 12 weeks significantly reduced SBP in patients with mild hypertension(Reference Kouguchi, Ohmori and Shimizu81). Similarly, Zhu et al. found that daily intake of 13 g of CPs for 12 weeks improved blood pressure regulation in patients with hypertension, potentially through activation of PPAR receptors, downregulation of the NF-κB pathway and increased bradykinin production, leading to significant reductions in both SBP and DBP(Reference Zhu, Li and Peng62).

Table 3. Nutritional interventions examining the anti-hypertensive effects of collagen supplementation in humans

a Standard deviation

RCT, controlled trial; BMI, body mass index; CP, collagen peptides; P, placebo; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; T2D, type 2 diabetes mellitus; ODS, observational-descriptive study; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; ↔, equal.

The observational study indicated that supplementation with 5·2 g of chicken collagen octapeptide (C-COP) in fifteen individuals with mild hypertension resulted in significantly reduced SBP and DBP after 2 and 4 weeks. The authors suggested that C-COP may inhibit renin, at the head of the RAS cascade, as well as ACE, reducing angiotensin II production(Reference Ai, Iwai and Hayakawa82). However, Igase et al. reported no differences in SBP or DBP in healthy older adults after ingestion of 2·5 g/d of pork CP. These discrepancies may partly reflect differences in ACE-inhibitory activity between chicken and pork CPs, with the former demonstrating stronger inhibition(Reference Igase, Kohara and Okada83).

Collectively, the available human data suggest that CP may modestly lower blood pressure in individuals with mild hypertension, although findings are heterogeneous across studies.

Mechanistic context (human and animal): potential pathways underlying reductions in blood pressure

The renin–angiotensin system (RAS) plays a central role in the regulation of blood pressure. At low blood pressure levels, renin secreted from the juxtaglomerular apparatus catalyses the production of angiotensin I, which is then converted by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) into angiotensin II. This peptide increases myocardial contractility and causes vascular smooth-muscle constriction, ultimately raising blood pressure to restore homeostasis(Reference Wood, Maibaum and Rahuel84). Therefore, suppressing this protein helps to regulate hypertension(Reference Chen, Xuan and Fu85). CP contains a high concentration of branched-chain aliphatic amino acids, as well as high levels of proline, which is considered to be one of the amino acids with the greatest inhibitory effect on ACE(Reference Byun and Kim86–Reference Saiga, Iwai, Hayakawa and Takahata90). Nonetheless, this effect of anti-hypertensive peptides, by inhibiting angiotensin-I-converting enzyme, has frequently been evaluated in animal experiments (hypertensive rats)(Reference Ichimura, Yamanaka and Otsuka87,Reference Saiga, Iwai, Hayakawa and Takahata90–Reference FitzGerald, Murray and Walsh92) .

In addition, ACE not only converts angiotensin I into angiotensin II but also degrades bradykinin. Bradykinin has been shown in vitro to promote the release of nitric oxide (NO) by endothelial cells, a vasodilatory agent that reduces arterial stiffness, and these effects have also been confirmed in vivo (Reference Ancion, Tridetti and Nguyen Trung93). Therefore, by inhibiting ACE activity, CP may contribute to increased bradykinin levels and NO release, decreased arterial stiffness and lowered blood pressure.

Beyond enzymatic inhibition, collagen also provides arterial structure so that blood can flow freely to and from the heart. In this context, CP may have a beneficial effect on the vascular system, with some clinical studies finding improvements in SBP(Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13).

Further insight into molecular mechanisms comes from animal studies. Song et al. evaluated a treatment combining a particular CP (LR-7) and taurine on cardiovascular health in hypertensive mice induced by an 8% high-salt diet. The findings showed a significant reduction in SBP, aortic intimal thickening, myocardial fibre density and fibrosis. These effects were elucidated by the calpain 1/junctophilin-2 (JP2) pathway in cardiac tissue. Calpain 1 expression is activated by angiotensin II which degrades the JP2 protein, found in mature cardiomyocytes, ultimately disrupting the excitation–contraction coupling of the heart, leading to myocardial damage. Furthermore, it upregulated the levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in the heart, demonstrating the synergistic efficacy of a CP and a sulphur-containing amino acid(Reference Song, He and Lin94).

Overall, current evidence supports the potential of CP as functional ingredients capable of exerting modest antihypertensive effects, primarily through ACE inhibition, increased bradykinin-mediated nitric oxide release and improved endothelial function. Nevertheless, findings across human studies remain inconsistent, and most mechanistic insights derive from animal models.

Anti-dyslipidaemia effect (Total cholesterol - TC, LDL-C, HDL-C and triacylglycerols - TG)

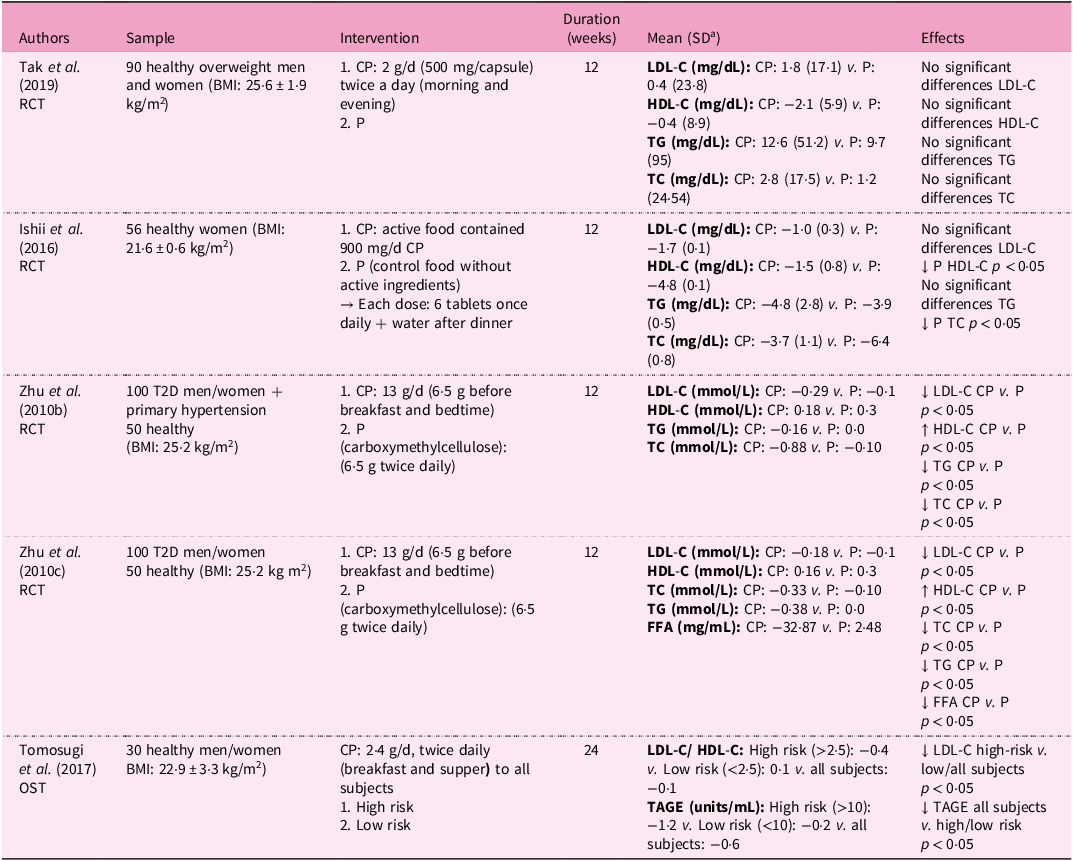

Human studies investigating the effects of CPs on serum lipid profiles are summarised in Table 4. Five clinical trials have examined the impact of CPs on circulating lipids, while complementary animal data also report improvements in lipid accumulation and metabolism following FCP therapy in obese mice(Reference Wang, Lv and Zhao95).

Table 4. Nutritional interventions examining the anti-dyslipidaemic effects of collagen supplementation in humans

a Standard deviation

RCT, controlled trial; BMI, body mass index; CP, collagen peptides; P, placebo; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol; T2D, type 2 diabetes mellitus; FFA, fatty free acids; OST; open-label, single-dose trial; TAGE, toxic advanced glycation end-products; ↓, decrease; ↑, increase; ↔, equal.

Zhu et al. indicated that supplementation of 13 g/d of CP for 12 weeks led to a significant reduction in LDL-C, TG and TC, and an increase in HDL-C in subjects presenting T2D with and without hypertension(Reference Zhu, Li and Peng60,Reference Zhu, Li and Peng61) . In contrast, Tak et al. (2 g/d of CP) and Ishii et al. (active food containing 900 mg/d CP) failed to find improvements in lipid profiles with up to 12 weeks of CPs because subjects had normal lipid levels from the very beginning and received lower doses compared with other trials(Reference Tak, Kim and Lee42,Reference Ishii, Okada and Matsuoka96) .

Collectively, the available clinical evidence suggests that CPs may modestly improve lipid metabolism, although results vary across studies depending on baseline lipid status, dosage and intervention duration.

Mechanistic context (in vitro and animal): potential pathways underlying lipid profile modulation

Preclinical evidence indicates that CP may modulate lipid metabolism through transcriptional and enzymatic regulation. The underlying biological mechanism is a probable reduction in gene expression of C/EBP-α, PPAR-γ and aP2(Reference Lee, Hur and Ham51,Reference Astre, Deleruyelle and Dortignac52) . At the same time, the expression of genes involved in unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis, the PPAR signalling pathway and fatty acid metabolism were upregulated. In particular, PPAR-α, a lipid sensor that monitors and activates fatty acid oxidation, was significantly upregulated(Reference Tometsuka, Koyama and Ishijima49).

Woo et al. observed that FCP intake suppressed hepatic lipid accumulation and reduced lipid droplet size in adipose tissue of mice fed a high-fat diet in a dose-dependent manner, inducing a decrease in serum TC, TG and LDL-C levels, while increasing HDL-C. This was due to the inhibition of hepatic expression of proteins that regulate fatty acid synthesis (sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (SREBP-1), fatty acid synthase (FAS), and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC)) and cholesterol synthesis (SREBP-2 and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGCR)). In addition to this, activation of proteins involved in β-oxidation (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-α) and carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1)) and bile acid synthesis (cytochrome P450) was observed. Moreover, hepatic p-AMPK and plasma adiponectin, key factors in fat oxidation, showed a high level of upregulation. In contrast, leptin showed low levels(Reference Woo, Song and Kang50).

In vitro, specific collagen-derived peptides may also contribute to hypolipidaemic activity. The peptide ‘GAPGFPGPR’, rich in arginine, aromatic and hydrophobic amino acids, has shown potent inhibition of cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP)(Reference Bi, Zhang and Liu97). CETP is a crucial enzyme in hyperlipidaemia, as it facilitates the conversion of cholesterol esters from HDL to LDL, which predisposes to hyperlipidaemia(Reference Barter, Brewer and Chapman98). An in vitro assay verified that GAPGFPGPR bound to CETP and inhibited its activity. Consequently, it significantly reduced TC, TG and LDL-C levels, and increased HDL-C levels, revealing its inhibitory effect on hyperlipidaemia(Reference Bi, Zhang and Liu97).

Clinical and vascular implications

Beyond lipid modulation, CP may also influence vascular and inflammatory processes associated with atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory process recognised as a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD)(Reference Tang, Sakai and Ueda99,Reference Libby100) . A clinical trial in healthy humans suggested the contribution of a specific collagen tripeptide (CTP), with a Gly-Pro-Hyp sequence in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerosis, since the LDL-C:HDL-C ratio was significantly lower in the high-risk group (>2·5). This indicates that CP is only effective in the plaque-prone condition, with an imbalance in the two cholesterol levels. The authors also observed a significant decrease in toxic advanced glycation end products (TAGE), commonly used as indicators of the development of atherosclerosis, caused only by the group with dysfunctional glucose metabolism, suggesting that CP may be beneficial in conditions where vascular wall damage is more likely to occur(Reference Tomosugi, Yamamoto and Takeuchi101).

There is evidence of dietary interventions as strategies to prevent and/or treat atherosclerosis and thrombosis-related CVD, with CS being one of them(Reference Wang2,Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13,Reference Jalili, Jalili and Moradi24,Reference Song, Zhang and Luo102) . Oral administration of CH has demonstrated modest antihypertensive effects in humans, as reported in a recent meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials(Reference Jalili, Jalili and Moradi24), and the underlying mechanisms have been proposed in preclinical studies to involve ACE inhibition. Other trials also reported reductions in arterial stiffness and increases in HDL-C levels, decreasing the likelihood of coronary heart disease(Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13). However, an imbalance between the two types of cholesterol (LDL-C:HDL-C ratio) is a well-known risk for CVD(Reference Al Hajj, Salla and Krayem13). In this context, CP has been shown to decrease the LDL-C and HDL-C ratio in healthy individuals(Reference Jalili, Jalili and Moradi24,Reference Song, Zhang and Luo102) .

Overall, current evidence indicates that CP may exert modest hypolipidaemic and vasoprotective effects, primarily through modulation of lipid metabolism genes, inhibition of CETP and activation of β-oxidation and AMPK pathways. However, human studies remain limited and heterogeneous, with small sample sizes, short durations and variable doses.

Other parameters related to MetS

Gut microbiota dysbiosis

Preclinical studies suggest that CS can influence gut microbiota composition and intestinal function, potentially contributing to metabolic regulation(Reference Wang, Lv and Zhao95,Reference Cani, Bibiloni and Knauf103) . Evidence from animal models indicates that CP can modify microbial balance and inflammation-related taxa, linking these effects to improvements in obesity- and diabetes-associated parameters(Reference Steele5). A microbial analysis performed in high-fat diet fed mice demonstrated that marine CP can regulate the composition of the intestinal microbiota by decreasing the abundance of inflammatory intestinal bacteria (Erysipelatoclostridium and Alistipes) and enhance taxa that have a positive effect on health, such as Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, Parabacteroides and Odoribacter. These results reveal the prebiotic effect of collagen as a potentially therapeutic mechanism for the management of obesity and metabolic diseases(Reference Wang, Lv and Zhao95).

Baek et al. recently described the effect of marine CP, soyabean or yeast, combined with a high-fat diet, on the Firmicutes:Bacteriodetes ratio in obese mice. Although no changes in microbial diversity or Akkermansia muciniphilia were observed, several bacterial taxa, such as Faecalibaculum, were associated with anti-obesogenic effects following CP administration(Reference Baek, Yoo and Kim104). In animal models of iron deficiency, modifying CP by ferrous chelation has been described to reverse intestinal dysbiosis. The collagen–iron peptide complex increased the amount of SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Blautia, Ruminococcus and Roseburia, which can maintain optimal pH of the intestinal lumen, promote intestinal tissue regeneration and decrease inflammation(Reference Jiang, Dong and Zhang105). It also promoted the growth of Subdoligranulum and the Christensenellaceae R-7 group, which have been associated with anti-obesity and anti-diabetic effects(Reference Chen, Zhang and Guo106).

Mechanistic context: prebiotic and metabolic effects

CP can exhibit prebiotic potential by interacting with the gut microbiota, leading to the release of SCFA and branched-chain fatty acids (BCFA) that can improve symptoms associated with metabolic diseases(Reference Ren, Yue and Zhang107). CP administration can modify the composition and metabolism of these bacteria, influencing gastrointestinal homeostasis by modulating barrier and immune function(Reference Bao and Wu108). Depending on the molecular weight of CP peptides, they can be directly absorbed in the intestine (low molecular weight), or, conversely, bypass absorption in the small intestine and reach the colon, where they are fermented by intestinal microorganisms (high molecular weight)(Reference Diether and Willing109). The high amino acid content of CP provides a source of nitrogen and carbon for the intestinal microbiota, promoting the production of nitrogenous microbial products, such as SCFA, BCFA and colonic gas, which exhibit prebiotic actions(Reference Larder, Iskandar and Kubow110). As a consequence, CP can generate bioactive fermentation products that provide health benefits to the host(Reference Li, Li and Guo111).

Overall, available evidence from in vitro and animal studies support a potential role of CP in promoting intestinal eubiosis by selectively stimulating beneficial bacteria and reducing pathogenic taxa. The resulting enhancement in SCFA production and barrier function could contribute to the prevention or mitigation of metabolic disturbances associated with obesity and diabetes. However, these findings remain preliminary, as human evidence is currently lacking.

Low-grade inflammation

Preclinical (in vitro and animal) studies demonstrate that CP and their constituent amino acids attenuate inflammation by modulating cytokine production, nitric oxide (NO) balance and lipoxygenase (LO) activity. FCP has reported anti-inflammatory activity in vitro by reducing LO activity and NO radicals(Reference Chen, Liang and Wu112). LO plays a crucial role in the synthesis of leukotrienes, mediators of numerous allergic and inflammatory conditions, and its expression is elevated in metabolic disease models, such as obese Zucker rats, where increased 5-LO and 12-LO in visceral adipose tissue is associated with higher leukotriene levels and pro-inflammatory cytokines(Reference Chakrabarti, Wen and Dobrian113). Therefore, reducing and inhibiting the lipoxygenase enzyme and NO can improve the inflammatory process. This is due to the ability of the hydroxyl (–OH) and amino (–NH2) groups of CP to neutralise NO radicals and bind to the active site of lipoxygenase, blocking its activity and reducing its production(Reference Chen, Liang and Wu112). Such effects align with the pathophysiological role of chronic low-grade inflammation in metabolic syndrome and related cardiometabolic disorders(Reference Masenga, Kabwe and Chakulya114–Reference Neeland, Lim and Tchernof117).

Glycine, one of the main structural units of collagen, has been found to have potent anti-inflammatory properties, as demonstrated in preclinical in vitro and animal models(Reference Hartog, Cozijnsen and de Vrij118). Glycine has been reported to decrease TNF-α levels and reduce muscle mRNA expression of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and nucleotide binding oligomerisation domain protein 2 (NOD2), two major proteins that act as sensors to detect harmful molecules and trigger inflammatory responses. By downregulating their expression, glycine suppresses excessive inflammation, helping to maintain immune balance, as demonstrated in vivo in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-challenged piglets(Reference Liu, Wang and Wu37). This mechanism involves glycine binding to glycine-gated chloride channels (GlyR) on immune cells, which reduces calcium influx and inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine release(Reference Wheeler, Stachlewitz and Yamashina119,Reference Liu, Yang and Liu120) . In animal models, glycine supplementation inhibited LPS-induced IL-6 production, attenuating endotoxin-driven inflammation(Reference Hartog, Cozijnsen and de Vrij118,Reference Wheeler, Stachlewitz and Yamashina119) .

Astre et al. showed that FCP administered to mice fed a high-fat-diet reduced the production of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and IL-1β) in isolated adipocytes(Reference Astre, Deleruyelle and Dortignac52). In addition, Zhu et al. also found that marine CP reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in rat models of T2D(Reference Zhu, Zhang and Mu65). Liu et al. investigated the effect of fish CH in ameliorating atherosclerosis in high-fat diet mice. This hydrolysate contained various bioactive peptides with anti-inflammatory, antiplatelet and antioxidant activity that combined synergistically. The results indicated that the fish CH had great potential to regulate the levels of inflammation biomarkers (IL-6 and TNF-α), endothelial injury (monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1)), platelet activation (thromboxane A2 (TXB2) and platelet factor (PF4)) and oxidative stress (malondialdehyde (MDA))(Reference Liu, Yang and Liu120). It is known that a high-fat diet induces inflammation, and that the development of atherosclerosis is modulated by vascular endothelial cell injury, lipid metabolism disturbances, chronic inflammation and oxidative stress(Reference Rader and Daugherty121). Taking this into account, the strong anti-inflammatory activity exhibited in the study was assigned to two multifunctional peptides from the hydrolysate: FAGPPGGDGQPGAK (FK-14) and IAGPAGPRGPSGPA (IA-14), which owing to the high content of hydrophobic and positively charged amino acids at the N and C termini of the peptide chain, promoted this anti-inflammatory effect(Reference Liu, Yang and Liu120).

Mechanistic context: molecular pathways underlying the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity of CP

Inflammation and oxidative stress are intimately related as ROS can induce inflammation directly or indirectly through cytoplasmic proteins that modulate inflammatory activity(Reference Monserrat-Mesquida, Quetglas-Llabrés and Capó122,Reference Keane, Cruzat and Carlessi123) . Within this framework, CPs may act on key molecular pathways such as nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB), a transcription factor that regulates immune-related gene expression, and the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, which modulate cell survival, differentiation and inflammation(Reference Hao, Xing and Wang124). CPs may also influence NO bioavailability: while NO serves essential roles in host defence, its overproduction by activated macrophages promotes inflammation via tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and interleukins (IL-6 and IL-8)(Reference Kim and Lee125). By modulating NO and LO pathways, CPs may restore redox balance and reduce inflammatory signalling.

These mechanistic interactions highlight how CP-derived peptides and amino acids could help counteract the chronic low-grade inflammation underlying metabolic disorders. Collectively, experimental evidence supports the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of CP through suppression of LO activity, modulation of NO and ROS levels, and regulation of NF-κB- and MAPK-dependent pathways. These effects appear to involve both direct chemical neutralisation of reactive species and indirect regulation of inflammatory signalling via glycine- and peptide-mediated mechanisms. While these findings are consistent across preclinical models, well-designed human trials are needed to confirm their relevance to the chronic low-grade inflammation characteristic of MetS and related disorders.

Oxidative stress

Preclinical (in vitro and animal) evidence suggests that CP, particularly FCP, enhance antioxidant-enzyme activity and reduce oxidative damage in models of metabolic dysfunction. Studies in diabetic mice supplemented with FCP showed increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities, along with reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. These enzymatic changes contribute to restoring oxidative balance, bringing it closer to that observed in non-diabetic controls(Reference Zhang, Chen and Jiang78,Reference Raksha, Halenova and Vovk126,Reference Raksha, Potalitsyn and Yurchenko127) . This hypothesis was supported by Zhu et al., who showed that FCP modulates oxidative stress by regulating glutathione (GSH) and NO levels in T2D diabetic rats(Reference Zhu, Zhang and Mu65). Such improvements in endogenous antioxidant defences are consistent with the broader evidence that oxidative stress and ROS overproduction play a central role in metabolic and degenerative diseases(Reference Sindhi, Gupta and Sharma128–Reference Lepetsos and Papavassiliou130).

It has been proposed that CP exert their antioxidant effects primarily because of their high glycine and proline content. While CP do not form a highly reactive site against free radicals, they may contribute to the reduction of oxidative stress indirectly by chelating metal ions and enhancing endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity rather than directly scavenge ROS(Reference Wu, Chen and Liu131). Accordingly, several studies suggest that both the amino acid composition and the degree of collagen hydrolysis play a crucial role in determining its antioxidant capacity, as demonstrated primarily in vitro (Reference Salvatore, Gallo and Natali1).

Known for the structure–function relationship of bioactive peptides, Val, Leu, Pro, Tyr and Ala residues could play an important role in this antioxidant capacity. Hydrophobic amino acid sequences have been identified as lipid radical scavengers and proton or electron donors. Tyr, Met, His, Lys and Trp exhibit potent radical-scavenging activities by donating electrons or hydrogen atoms to stabilise free radicals(Reference Nikoo, Regenstein and Yasemi132,Reference Prakash Nirmal, Singh Rajput and Bhojraj Rathod133) . However, multiple factors apart from amino acid composition, including chain size and length and sequence arrangement, influence the capacity of FCP and hydrolysates to exhibit antioxidant properties(Reference Nikoo, Regenstein and Yasemi132,Reference Cadar, Pesterau and Prasacu134) .

Hydrolysed collagens from various animal sources have demonstrated antioxidant properties in vitro. Porcine byproducts exhibit strong antioxidant properties, evidenced by their high reducing power and 2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) radical-scavenging activity(Reference Hong, Min and Jo135), while hydrolysed collagens from sheep skin show significant antioxidant activity in both ABTS and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assays, likely owing to their high hydrophobic amino acid content(Reference León-López, Fuentes-Jiménez and Hernández-Fuentes136). Hydrolysates from skipjack tuna bone, chicken skin, grass carp scale and red lip croaker scale can significantly accelerate free radical scavenging activity and protect cells against H2O2-induced oxidative damage by activating antioxidant enzymes including SOD, CAT and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), while simultaneously reducing ROS and MDA levels(Reference Du, Zhang and Deng137). Similarly, peptides from yak bone hydrolysates show significant scavenging activity against ABTS and hydroxyl radicals, and the peptide Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Ala-Asp-Gly-Val-Ala demonstrates a protective effect in Caco-2 cells subjected to oxidative stress(Reference Sun, Wang and Gao138). Moreover, CP from Siberian sturgeon cartilage provided protection against H2O2-induced DNA damage in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (in vitro)(Reference Du, Zhang and Deng137).

The development of hypertension caused by high salt intake is intimately linked to oxidative stress, which causes endothelial dysfunction that damages vascular tissue and consequently increases blood pressure(Reference Touyz, Rios and Alves-Lopes139). Some researchers tested a combined treatment of CP (LR-7) and taurine (an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory amino acid) on cardiovascular health in hypertensive mice induced by an 8% high-salt diet. They observed improvements in antioxidant enzyme levels (catalase and glutathione peroxidase) and inflammatory markers (IL-6, IL-1 β and NF-κB) in the hypertensive mice treated with LR-7 plus Tau(Reference Song, He and Lin94).

Mechanistic context: molecular basis of antioxidant activity of CP

The mechanism of action of antioxidants is mainly on the basis of electron transfer reactions, donating electrons to carbonyl compounds, metal ions and free radicals. This process neutralises harmful substances, thus mitigating their detrimental effects(Reference Ivanova, Gerasimova and Gazizullina140). ROS, including singlet oxygen species, alkyl radicals, hydroxyl radicals (•OH), peroxide radicals and superoxide radicals (O2-)(Reference Wu, Wu and Liu141), are natural byproducts of the oxidative mechanism of aerobic respiration(Reference Augustyniak, Bartosz and Čipak129,Reference Adjimani and Asare142) . CP appear to modulate both ROS production and antioxidant defences in preclinical models, thus improving redox homeostasis.

The Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1)–nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signalling pathway plays a crucial role in the cellular responses to oxidative stress, making it a promising target for antioxidant peptide research(Reference O’cathail, Wu and Thomas143). Upon oxidative stress, Nrf2 dissociates from Keap1 and translocates to the nucleus to upregulate the production of antioxidant enzymes(Reference Lu, Ji and Jiang144,Reference Zhu, He and Huang145) . Therefore, CP capable of binding Keap1 and inhibiting Keap1–Nrf2 complex formation enhances cellular resistance to oxidative stress. In vitro studies have shown that Nrf2 can bind to Keap1 target receptors via hydrogen bonds with arginine residues, suggesting that peptides interacting with these sites could serve as potential Keap1–Nrf2 inhibitors(Reference Hancock, Bertrand and Tsujita146).

Du et al. selected four novel antioxidant CP (GPAGPIGPVG, GPAGPpGPIG, ISGPpGPpGPA and IDGRPGPIGPA), which stabilise interactions with Keap1 through hydrogen bonds, thereby enhancing the activation of antioxidant enzymes and scavenging ROS. Among them, IDGRPGPIGPA exhibited the highest DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging capacity, probably owing to its N-terminal hydrophobic amino acid content. GPAGPpGPIG, however, significantly increased cellular resistance to H2O2-induced oxidative stress through Nrf2 activation and enhanced the production of antioxidant enzymes in HepG2 cells(Reference Du, Zhang and Deng137). Other in vitro studies have also reported antioxidant peptides in CH, such as GFGPEL and VGGRP(Reference Cai, Wu and Zhang147), GPIGPVGAR and GPIGSRGPS(Reference Song, Fu and Huang148), and PMRGGGGTHT(Reference Wu, Wu and Liu149).

Collectively, experimental and in vitro findings support the antioxidant potential of CP through enhancement of enzymatic defences (SOD, CAT and GSH-Px), metal-ion chelation, radical scavenging and activation of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway. These effects depend on peptide sequence, amino acid composition and hydrolysis degree, which together determine bioactivity. However, evidence for direct ROS scavenging in humans is still limited.

Clinical translation and public health relevance

Beyond its mechanistic actions, CS may hold translational potential for the prevention and management of MetS and its associated risk factors. Preclinical evidence suggests modest benefits on body composition, glucose regulation, lipid metabolism and vascular function, but these effects remain context-dependent and should be interpreted within broader dietary and lifestyle frameworks, although in humans there are studies showing no relevant effects. Given its high tolerability, low allergenicity and versatility in food formulations make it a feasible adjunct to balanced dietary and lifestyle interventions, particularly among older adults or individuals with suboptimal protein intake. From a population-health perspective, collagen should be regarded as a complementary, rather than substitutive, strategy within integrated approaches to metabolic disease prevention.

Nonetheless, several limitations constrain the clinical translation of current evidence. Most data originate from preclinical studies that use high or supra-physiological doses, uniform animal strains, or controlled environments that do not capture human variability, and outcomes observed in vitro may not fully replicate systemic effects in vivo. In human studies, translation remains limited, as clinical trials are generally small, short-term and heterogeneous in design, dosing and endpoints, with some reporting no significant effects. Variability in collagen sources, formulations and molecular weights complicate interpretation, as does incomplete control of participants’ dietary background and physical activity. Future investigations should focus on elucidating optimal dosing, treatment duration and potential synergistic effects with other nutrients, using rigorous randomised controlled designs and standardised biomarkers. Addressing these gaps will enhance the translational validity of CS in metabolic health. Strengthening the link between mechanistic findings and clinical outcomes will also help establish its relevance for public health nutrition.

Conclusions

CS has been reported to reduce fat mass, improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood pressure and regulate lipid profiles, and is therefore considered a promising strategy for the management of MetS in humans. The beneficial effects of collagen are attributed to the stimulation of different metabolic pathways regulated by mTOR, PPAR, AMPK, PGC-1α or C/EBP-α; the inhibition of blood pressure-related enzymes (that is, ACE); the regulation of glucose metabolism by stimulating incretin secretion (that is, GLP-1 and GIP); the modulation of the gut microbiota; and the mitigation of the pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative status. Although several studies suggest its therapeutic potential, additional evidence is needed to confirm its effectiveness in humans, optimise its clinical application, including dosage, duration and grade of hydrolysation, and unveil the mechanisms of action.

Financial support

This work was financially supported by CIBEROBN (CB12/03/30002), CINFA and Viscofan. They had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they are research members of the Center for Nutrition Research at the University of Navarra, which has a programme agreement with the companies CINFA and VISCOFAN.

Authorship

Conception and design: M.P.-A. and F.I.M. Analysis and interpretation of the data: M.P.-A., M.A.Z. and F.I.M. Original draft of the paper: M.P.-A., S.N.-C. and F.I.M. Critical revision for intellectual content: M.L.-Y., S.N.-C., C.J.G.-N., M.A.Z. and F.I.M. Final approval: M.P.-A. and F.I.M. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.