1. Introduction: an examination of the Gāndhārī lexicon for “gift” in the epigraphical corpus

The gift (dāna) – in its two facets of gift-giving and gift-receiving – holds a central position within South Asian cultures, in which, from an anthropological point of view, it is characterized in ways that differ from other civilizations. Compared to Mauss’s general theory (cf. Mauss Reference Mauss1923), gifts are expected to be non-reciprocal in Indian society (see Parry Reference Parry1986: 459–63; Michaels Reference Michaels1997). From the last centuries before the Common Era, which constituted the post-Vedic period, the gift has undoubtedly been one of the issues on which Brahmanical, Buddhist and Jaina religious traditions have focused in systematizing their own rules of conduct. As Heim (Reference Heim2004) demonstrated, reflection on knowing how to give found its highest expression during the medieval period (particularly between the tenth and thirteenth centuries) when Brahmanical Dharmanibandhas, Jain Śrāvakācāras and Buddhist Saṅgahas were composed. However, as for earlier periods, there is a lack of normative texts, and there is consequently the risk of superimposing chronologically subsequent rules about gifts on the earlier Vedic periods. In this regard, Candotti and Pontillo (Reference Candotti and Pontillo2019a: 25–8) stated that the methodology to be employed has to mix philological and linguistic research, considering the diachronic, diatopic and diastratic features stratified in the Vedic corpus. Following this methodology, the scholars conducted a survey of Vedic sources resulting in different attitudes towards gift-accepting (based on the analysis of Ved. verbal base prati-grah-/-grabh- and its derivatives) which may reflect at least two specific Indo-Aryan cultural matrices most likely coexisting in different geographical areas (see Candotti and Pontillo Reference Candotti and Pontillo2019a). An analogous work was devoted to investigating the association between gift and merit after the donation of dakṣiṇā in the Vedic Saṃhitās and Suttapiṭaka (based on the analysis of Ved. dakṣiṇī́ya- and P. dakkhiṇeyya-), and a reappraisal of the original meaning of dakṣiṇā as “magnificence” (based on the analysis of Ved. dákṣiṇā- and P. dakkhiṇā) (see Candotti, Neri and Pontillo Reference Candotti, Neri and Pontillo2020; Reference Candotti, Neri, Pontillo, Poddighe and Pontillo2021).

In this framework, the article aims to explore a South Asian culture that has not been previously analysed, namely the Gandhāra culture. Within the Gāndhārī gift lexicon found in epigraphical sources, the focus is on a triad conveying the meaning of “gift”: G. dana- (which can also mean “giving”), danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- (in the version in which they are recorded in Baums and Glass Reference Baums and Glass2002b), which, in the actual corpus of Gāndhārī inscriptions,Footnote 1 occur 36, 111 and 14 times respectively, both as a single word and as a compound constituent. This triad has only partially interested scholars, who have limited themselves to recording their synonymous use or commenting on their grammatical construction in the case of the two compounds. Apart from some significant reflections by Damsteegt (Reference Damsteegt1978), there is a lack of scholarship that collects all the occurrences of these three word-forms, analyses them semantically and then questions whether a rationale can be established for their use over time in Gāndhārī inscriptions. This article seeks to address this gap. To commence, I present a comprehensive inventory of occurrences of G. dana-, danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- within the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus, hitherto unavailable. The findings are supplemented by a reference to their attestation in sources beyond the Gāndhārī context, encompassing both epigraphical and literary references (see section 2). Subsequently, I examine the data collected from the semantic point of view, focusing on the synchronic and diachronic relationship among the three word-forms denoting “gift” in Gāndhārī inscriptions (see section 3).

2. The occurrences of G. dana-, danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus and their attestation in extra-Gāndhārī sources

2.1. G. dana-

The G. word-form dana- (< OIA dāna-) is attested as a single word in the corpus of Gāndhārī inscriptions in 27 occurrences. For completeness, I report that it is also attested in manuscripts in 19 occurrences and documents in 4 occurrences, but it does not occur in coins. In all three corpora, the word-form maintains the semantic ambivalence with which it is endowed in the Vedic corpus: it can denote “gift” per se (i.e. nomen rei actae) and “giving” (i.e. nomen actionis). Sticking to inscriptions, G. dana- is also attested as a compound constituent in the following instances:

• The left-hand constituent of danamuha- (see section 2.2) and danasaṃyuta- (< OIA dānasaṃyukta-, “connected with giving”, attested twice in Aśoka’s inscriptions: CKI 5, 19).

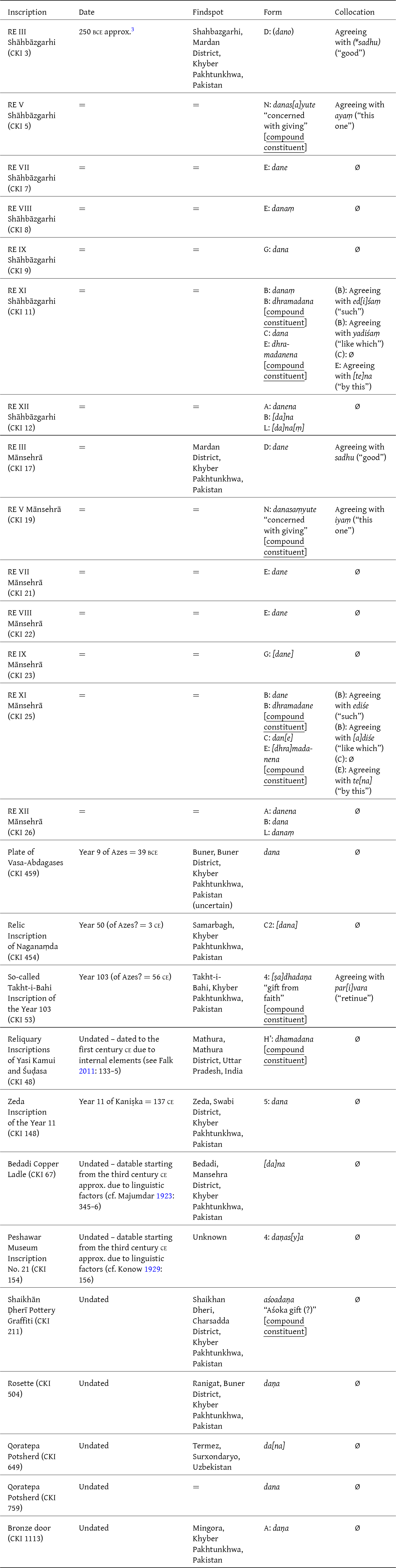

• The right-hand constituent of aśogadana- (presumably “an Aśoka gift (?)”, attested once in CKI 211), dhaṃmadana- (“giving/gift of the dharma”, attested five times in CKI 11, 25 and 48) and ṣadhadana- (“gift from faith”, attested once in CKI 53) (see Table 1).Footnote 2

Table 1. Comprehensive inventory of the 36 occurrences of G. dana- as a single word and as a compound constituent in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus (CKI)

Key: = equal to what is found above; Ø no collocation available.

2.2. G. danamuha

The G. compound danamuha- (mainly attested with the spelling danamukha- or daṇamukha-, more rarely with the spelling daṇamuha-) is only attested in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus – it is not attested in Gāndhārī manuscripts, documents and coins. Of the three word-forms under analysis, this one appears most frequently in the inscriptions, with a total of 111 occurrences (see Table 2). Its OIA equivalent (presumably *dānamukha- or *dānamukhya-) does not occur in Vedic and Sanskrit sources, and, as Damsteegt (Reference Damsteegt1978: 170–1) suggests for one of its rare extra-Gāndhārī occurrences, an influence from Gandhāra can reasonably be assumed.Footnote 4 For the current state of discoveries, the compound danamuha- with its variant spellings has to be considered a Gāndhārī coinage. The scholarship generally translates the compound danamuha- as “gift”/“donation” (therefore, as a synonym of G. dana- in the sense of “gift”; cf., for example, Baums Reference Baums, Rienjang and Stewart2018: 68) or “pious gift”/“pious donation” (cf., for example, Falk Reference Falk, Mevissen and Banerj2009: 27).Footnote 5

Table 2. Comprehensive inventory of the 111 occurrences of G. danamuha- in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus (CKI)

2.3. G. deyadhaṃma

The compound deyadhaṃma- (mainly attested with the spelling deyadharma-, more rarely with the spellings deyadhaṃma- and deyasama-) is attested only in the Gāndhārī inscriptions in 13 occurrences – it does not occur in Gāndhārī manuscripts, documents and coins. Like the previous case, its OIA equivalent (presumably *deyadharma-) does not occur in Vedic and Sanskrit sources. However, unlike G. danamuha-, it is extensively attested in other non-Gāndhārī MIA literary and epigraphical sources.Footnote 9 Regarding the interpretation of G. deyadhaṃma- in Gāndhārī inscriptions, scholars generally translate it as “gift”/“donation” (cf., for example, Baums Reference Baums, Rienjang and Stewart2018: 68) or, based on the parallel danamuha- (see section 2.2), as “pious gift”/“pious donation” (cf. Salomon Reference Salomon1999: 218).Footnote 10 Unlike G. danamuha- (see sections 2.2, 3.1), a Gāndhārī coinage cannot be assumed for G. deyadhaṃma-, given its wide occurrence in other MIA sources.

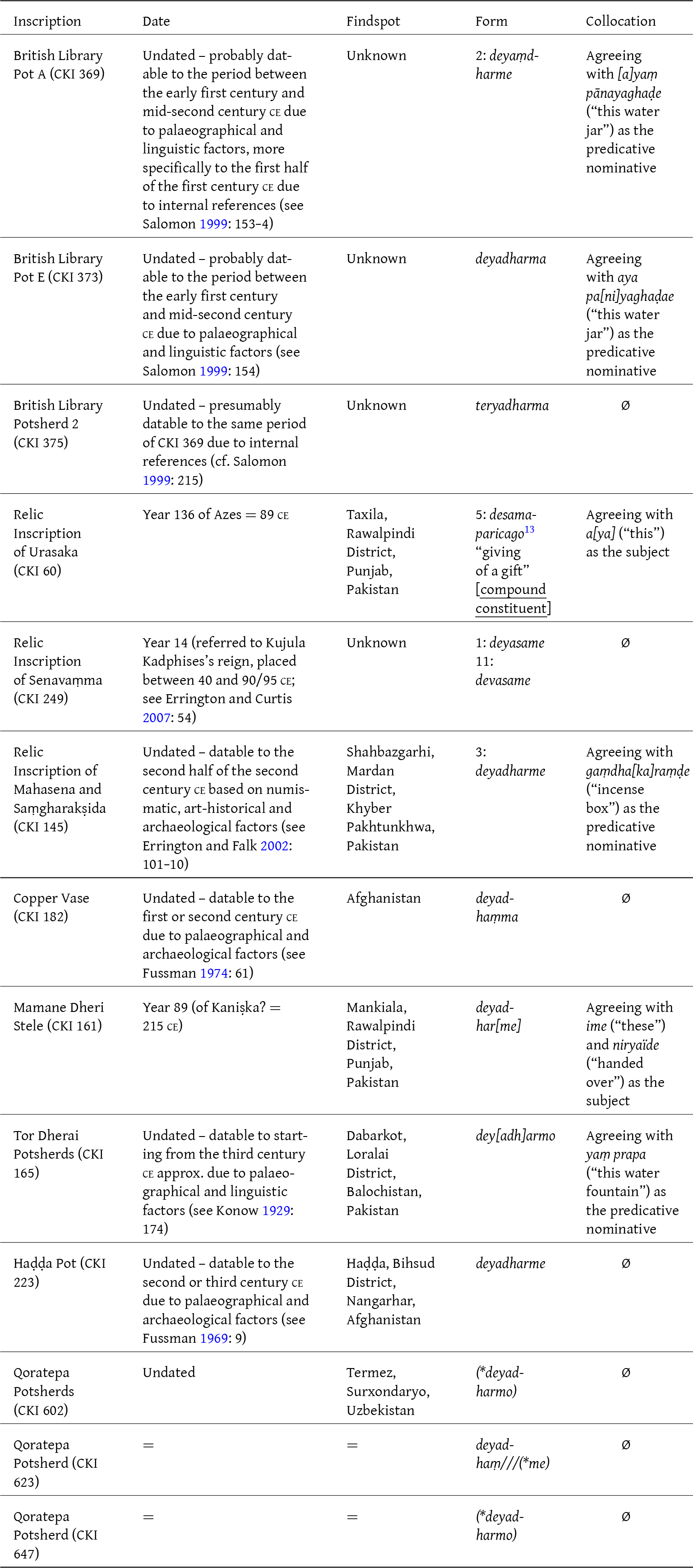

Furthermore, G. deyadhaṃma- also occurs as a member of the compound deyadhaṃmaparicaga- (lit. “leaving a gift” > “giving of a gift”) once in inscriptions: CKI 60 (see Table 3).Footnote 11 I note that, as in the case of G. deyadhaṃma- itself, this compound is also attested in extra-Gāndhārī Buddhist sources.Footnote 12

Table 3. Comprehensive inventory of the 14 occurrences of G. deyadhaṃma- as a single word and as a compound constituent in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus (CKI)

3. Semantic analysis of G. dana-, danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus

This section analyses the collected data regarding the three Gāndhārī word-forms denoting “gift”. Its final part proposes a hypothesis on the origin of the G. compound danamuha- (see section 3.1).

Starting with G. dana-, it has 36 occurrences in Gāndhārī inscriptions, 27 as a single word and 9 as a compound constituent. As far as I could ascertain for its attestation as a single word, in the early occurrences of G. dana-in Aśoka’s Edicts (18 out of 27),Footnote 14 the ambivalence between “gift” and “giving” (shared with OIA sources) is undoubtedly maintained. In the other occurrences (9 out of 27), attested in later sources (approximately between the first century bce and the third century ce), G. dana- is used in the donative formulas with the meaning of “gift”.

Turning to G. danamuha-, it has attracted the attention of scholarship since the earliest studies of Gāndhārī inscriptions, perhaps because it is attested almost only and so massively in such a corpus, numbering 111 occurrences. Scholars have focused on the relationship between G. danamuha- and dana- and the relationship between G. danamuha and deyadhaṃma-. As for the first, I refer to Damsteegt (Reference Damsteegt1978: 306, fn. 1), according to whom “[the word-form dāna-] is in the North-west generally replaced by the expression danamukha- or danamuha-” (cf. also Senart Reference Senart1890: 130–4; Thomas Reference Thomas1915: 97–9; Majumdar Reference Majumdar1922: 62–3). As for the second, I refer to Salomon (Reference Salomon1999: 241), according to whom the two G. compounds danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- are used as synonymous expressions denoting “pious gift” in Gāndhārī Buddhist donative inscriptions, regardless of their etymological difference (cf. also Senart Reference Senart1902–03: 55; Sircar Reference Sircar1966: 79, 90, 205). The employment of G. danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- in donative formulas (about the synonymous use of which there is little to dispute) has caused scholarship to neglect a structured reflection on their etymology (and, being two compounds, about their interpretation). A few attempts were still made. Pargiter (Reference Pargiter1913–14: 300; Reference Pargiter1921–22: 98–100) interpreted G. danamuha- as a karmadhāraya compound, translating it as “choice gift”. A similar conclusion is reached by Damsteegt (Reference Damsteegt1978: 246, 334, fn. 36), who interpreted it as a karmadhāraya compound meaning “excellent gift”, albeit he reports that -mukha is only attested in bahuvrīhi compounds with the meaning of “having…as best”. The most complete reflection on the etymology of G. danamuha- and also of G. deyadhaṃma- is by Bopearachchi and Salomon (Reference Salomon2022–23: 53, fn. 8), which I cite integrally as a basis for the discussion that will follow:

The widely attested (in inscriptions) but grammatically peculiar term dānamukha (Sanskrit and Pali; Gāndhārī daṇamukha), conventionally translated as “pious gift,” is perhaps best interpreted as a compound with the component members in reversed order, as is not uncommon in Sanskrit and various Middle Indo-Aryan languages […]; thus, dānamukha = *mukh(y)adāna, “principal/outstanding gift”. The same may be true of the more or less synonymous and even more common (both in inscriptions and Buddhist literature) deyadharma ≟ dharmadeya “to be given by/according to/for the Dharma”.

Analysing the hypothetical original OIA form *dānamukha- or *dānamukhya- with Pāṇini’s Aṣṭādhyāyī, there is, however, no need to assume an inversion of the constituents. Indeed, this compound could be interpreted either as a bahuvrīhi or a karmadhāraya:

• If interpreted as a bahuvrīhi compound (explained by the general rule A 2.2.24),Footnote 15 the order of the constituents follows A 2.2.35,Footnote 16 according to which the qualifying word (in this case: dāna-) occurs as the left-hand constituent. In this case, the meaning would be “having (the act of) giving as the principal feature/origin/purpose”, thus “gift”.

• If interpreted as a karmadhāraya compound (explained by the general rule A 1.2.42),Footnote 17 the order of the constituents would, in fact, break rule A 2.2.30,Footnote 18 according to which the non-head member (upasarjana, the notion of which is introduced in A 1.2.43)Footnote 19 occurs in the left-hand slot; however, this impasse is overcome by recourse to A 1.2.44,Footnote 20 which allows considering even a constituent that does not occupy the left-hand slot as the non-head member (see Pontillo Reference Pontillo, Ronzitti and Borghi2003; Mocci and Pontillo Reference Mocci and Pontillo2019: 5–7; Candotti and Pontillo Reference Candotti and Pontillo2022: 12–15; Mocci Reference Mocci2023: 291–4). In this other case, the meaning would be “chief/eminent gift”.

Pāṇini’s rules may support both interpretations. Nonetheless, interpreting it as a karmadhārayais undoubtedly more cumbersome than its more straightforward explanation as a bahuvrīhi, which I lean towards thanks to the analysis of this compound’s collocations (see Table 2). Excluding cases where it is attested not in co-occurrence with another word, the following groups of collocations are identified:

a) The G. compound danamuha- mainly occurs as the predicate nominative (CKI 52, 61, 110, 371, 452, 458, 506, 545, 556, 731, 833). Here is an example (CKI 371): [a]ya panighaḍa [da]ṇaṃmukh[o] Viratatae [Srva]hiamabharyae […] “This water jar is the gift (following its analysis as a bahuvrīhi: ‘originated from the act of giving’) for Viratata, wife of Srvahiama”. In these occurrences (particularly those in which the demonstrative adjective is missing), the compound can also be read not as the predicate nominative in nominal sentences but as a simple apposition.

b) In other cases, it occurs as the subject complement (CKI 148, 156, 177). Here is an example (CKI 177): Tramisa daṇamu〈*khe〉 ime śarira presthavida budhaṇa puyae “These relics are established as the gift (following its analysis as a bahuvrīhi: ‘originated from the act of giving’) of Trami in worship of the Buddha”.

c) In one case, it occurs as the object complement (CKI 461, at least based on the reconstructed reading of its final part): saṃ 20 20 20 20 4 1 Arsamiasa masasa di 1 Nribhratriśamaputra danamukho ekha [k](*ue) “In year 85 (of Kaniṣka? = 211 ce), month Artemisios, day 1, Nribhratriśama’s son had the well dug as a gift (following its analysis as a bahuvrīhi: ‘originated from the act of giving’)”.

The reading of G. danamuha- as a bahuvrīhi is reinforced by the fact that, in the occurrences mentioned above, a linguistic element agrees with the compound and serves as the headword of the syntagma. It is conceivable that in all the other cases in which G. danamuha- is not attested in co-occurrence with another word, zero (Skt. lopa, according to Pāṇinian authors) of a noun used as the head of the syntagma has become widespread, admitting the use of G. danamuha- as a single word with the sense of “gift”. The semantic change hypothesized here is as the following made-up example: *danamuho kuvo “the well (headword of the syntagma) originated from the act of giving (subordinate word of the syntagma)” > *danamuho “gift”.Footnote 21 Despite the vigraha of the compound (the coinage of which is further explored in section 3.1), it is hardly debatable that, based on the evidence gathered (see section 2.2), G. danamuha- is pragmatically used only in donative formulas with the meaning of “gift” in a ritual context, regardless of the conventional translation as “pious gift” that often appears in scholarship.

In the case of G. deyadhaṃma-, attested in the Gāndhārī epigraphical sources from around the first century ce onwards in a much smaller number (13 occurrences as a single word and 1 as a compound constituent), the grammatical analysis slightly changes. Analysing the hypothetical original OIA form *deyadharma- with Pāṇini’s rules, the same rules mentioned above apply, with the difference that this compound could be analysed either as a bahuvrīhi or a tatpuruṣa:

• If interpreted as a bahuvrīhi compound (regularly following A 2.2.35), the meaning would be “having the feature of having to be given”, thus “gift (to be given)”.

• If interpreted as a tatpuruṣa compound (with the non-head member in the right-hand position according to A 1.2.44), the meaning would be “to be given for the sake of the dharma” (analysed with M 1.458 l. 16 Vt. 6 ad A 2.3.36).Footnote 22

Again, Pāṇini’s rules would support both interpretations, but the one as bahuvrīhi is also preferable based on the analysis of this compound’s collocations (see Table 3). In this case, excluding its attestations as a single word, it only occurs as a predicative nominative (CKI 145, 165, 369, 373). Here is an example (CKI 373): aya pa[ni]yaghaḍae Hastadatae Teyavarmabharyae deyadharma saghe caturdiśe atmanasa arogadakṣine […] “This water jar is the gift (following its analysis as a bahuvrīhi: ‘featured by having to be given’) of Hastadata, wife of Teyavarman, to the community of the four directions for the benefit of her own health”. The same reasoning as above also applies here. As in the case of G. danamuha-, based on the evidence gathered (see section 2.3), G. deyadhaṃma- pragmatically means “gift” in the ritual context.

Regarding the relationship between the two compounds, the data at our disposal point to a synonymous use of the two word-forms, both denoting a ritual gift in the donative formulas regardless of etymological differences (for which there would be a nuance of duty in G. deyadhaṃma- which is then lost). Likewise, there is no pragmatic distinction between these two and the few late records of G. dana-, also referring to a ritual gift in donative formulas. There are no significant data to assume a distinction of period, place, material, (types of) donors or Buddhist schools. The only significant element is the difference in occurrences between G. danamuha-, which is extensively used, and G. deyadhaṃma-, which is seldom used (along with the later attestations of G. dana-). This disparity may be explained by the fact that G. danamuha-, which is most likely a Gāndhārī coinage and appears almost exclusively in the Gāndhārī epigraphical sources, is predominantly used in Gāndhārī donative formulas. Indeed, G. deyadhaṃma-, which is probably a loanword from another MIA language and appears extensively in MIA literary sources, is the least used term overall in Gāndhārī inscriptions.

3.1. A hypothesis on the origin of G. danamuha

As discussed above (see sections 2.2 and 3), it may be concluded that G. danamuha- is a Gāndhārī coinage (unlike G. deyadhaṃma-) and that it gradually replaced the earlier G. dana- (see Damsteegt Reference Damsteegt1978: 306, fn. 1). However, the origin of this compound has not been further explored by scholarship.

For the sake of readability, let me summarize the available data. From the mid-third century bce to the end of the first century bce, the meaning “gift” (nomen rei actae) was denoted only by the word-form G. dana-. However, this fluctuates between the meaning of “giving” (nomen actionis) and that of “gift” (nomen rei actae) in Aśoka’s inscriptions, just like the OIA corresponding word-form dāna-. From around the end of the first century bce onwards, the G. compound danamuha- is attested in Gāndhārī inscriptions with the sole meaning of “gift” (nomen rei actae). After the first attestations of G. danamuha-, the denotatum “gift” (nomen rei actae) was predominantly meant by the latter word-form in epigraphical donative formulas (111 occurrences) at the expense of G. dana- (9 occurrences as a single word) and deyadhaṃma- (13 occurrences as a single word), which pragmatically mean “gift” as well.

In relation to these data, I propose that a phenomenon of semantic change has occurred: specifically, a new compound was coined from an etymon with an ambiguous meaning to disambiguate its meaning in the formulas used in inscriptions.Footnote 23 The G. compound danamuha-, correctly interpreted as a bahuvrīhi “having (the act of) giving as its principal feature/origin”, thus “gift”, was coined from G. dana-, both meaning “giving” and “gift” (like OIA dāna-), to convey unambiguously the sole meaning of “gift” as nomen rei actae. The need to disambiguate the meaning of the etymon G. dana- is in line with the religious context of the inscriptions in which these word-forms occur, as they are attested in Buddhist donative objects. After the coinage of G. danamuha-, this is indeed by far the most used term denoting “gift” in the Gāndhārī inscriptions, although the other two word-forms G. dana- and deyadhaṃma- are also rarely attested with the same meaning.

4. Conclusion

In this article, I investigated the gift lexicon in the Gāndhārī epigraphical corpus, focusing on the triad formed by G. dana-, danamuha- and deyadhaṃma- (see section 1). These are attested 36, 111 and 14 times respectively (both as single words and compound constituents) in the Gāndhārī inscriptions, and a complete repertoire of their occurrences has been provided (see Tables 1–3). Among the three terms, only G. dana- has a counterpart in the Vedic and Sanskrit works, i.e. OIA dāna-. While G. deyadhaṃma- is frequently attested in other non-Gāndhārī MIA sources (e.g. P. deyyadhaṃma-; BHS deyadharma-) and can be considered a loanword from another MIA language, G. danamuha- can be regarded as a Gāndhārī coinage, as it appears almost exclusively in Gāndhārī inscriptions, except for a few very late occurrences in Pāli works (see section 2). When analysing the data collected, G. dana- is the earliest attested term. In the earliest attestations in Aśoka’s Edicts (dated to the mid-third century bce), its meaning oscillates between “giving” (nomen actionis) and “gift” (nomen rei actae). From around the end of the first century bce, G. dana- was gradually replaced by G. danamuha-, exclusively meaning “gift” (nomen rei actae). It has a far greater attestation (111 occurrences) than G. dana- (9 late occurrences as a single word) and deyadhaṃma- (13 occurrences as a single word), also with the sole meaning of “gift”. The interpretation of the two compounds as “gift” is supported by the vigraha of the compounds, which, from a grammatical perspective, have to be more consistently considered as bahuvrīhis (see section 3). In the final section, I propose analysing the coinage of G. danamuha- as a phenomenon of semantic change with respect to the earlier G. dana-. The new compound G. danamuha- was preferred to disambiguate the meaning of the earlier G. dana-, oscillating between “giving” and “gift”, and to restrict its meaning solely to that of a nomen rei actae. Indeed, this need for disambiguation is justified by the religious context in which such word-forms are attested, specifically Buddhist donative inscriptions (see section 3.1).

Abbreviations

- BHS

Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit

- G.

Gāndhārī

- MIA

Middle Indo-Aryan

- OIA

Old Indo-Aryan

- P.

Pāli

- Skt.

Sanskrit

- Ved.

Vedic

Acknowledgements

All translations from Gāndhārī and Sanskrit are my own unless otherwise stated. I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Mark Allon, Maria Piera Candotti, Beatrice Grieco, Davide Mocci, Leonardo Montesi, Chiara Neri, Tiziana Pontillo and Ingo Strauch for their valuable suggestions and corrections throughout this research or for reviewing a provisional draft of this article. I would also like to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers of this journal whose insightful feedback strengthened my argument and provided invaluable insights. Any remaining errors or omissions are, of course, entirely my responsibility.