Corporate criminal liability may fill a gap in the traditional framework for punishing individual actors to deter mass atrocities. Corporate policies, according to many scholars, reward and coordinate the activities of natural persons who might have acted differently as individuals. The argument of this chapter is that the same may be true of organizations other than corporations, and that closing the many gaps left in the net cast around crimes against humanity and war crimes will require holding noncorporate organizations accountable in court.

At the Nuremberg Trial, US prosecutor Robert Jackson famously compared aggression to assault with bare fists, which was a crime under all “civilized” laws, and he argued that multiplying the offense by a million and adding machine guns and explosives to the mix was no defense.Footnote 1 Similarly, the hiring of “hit men” or the inflaming of social tensions to the point of assault or riot is also an offense under civilized laws. The question arises, does crossing national borders and multiplying the scale of the offense by thousands or millions – while adding missiles, mortars, and tanks to the mix – immunize from penal remedies what would otherwise be an offense?

The African Court of Justice and Human and Peoples Rights is poised to exercise the power to punish a plethora of pan-African population-level crimes. This chapter focuses on the modes of liability clause of the amended statute of the court, which extends African court criminal liability to legal persons. A complicating factor is the wording of the relevant article, Article 46C, which refers to “corporation[s],” “corporate personnel,” “corporate intention,” and a “body corporate” without referring in parallel provisions to organizations other than corporations.Footnote 2 Such organizations – which include partnerships, political parties, and unincorporated associations in the form of terror groups – are suspected of committing or facilitating a variety of crimes that will be within the jurisdiction of the future African court, and such organizations have been sued in U.S. federal courts for genocide, rape, torture, summary executions, terrorism, and other extrajudicial killings.Footnote 3

Political groups such as parties, armies, and fronts have been guilty of some of the worst atrocities in recent memory – the devastation of Sierra Leone, eastern Angola, eastern Congo (Kinshasa), and northern Uganda, for example. Religious organizations, charities, and foundations probably lie behind some of the most horrific episodes of terrorism and civilian enslavement and massacre by terrorist groups. For example one only needs to recall the African embassy bombings of 1998, the Somali university and other bombings, the Kenyan Westgate shopping mall massacre, the Boko Haram attacks on Christians and pro-government Muslims in northern Nigeria and neighboring states, and the Islamic State massacres of Copts and other Christians in Libya and Tunisia.Footnote 4 Religious and gender-related persecution by nonstate actors such as churches and armies has also been a problem, including the sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests rotated from parish to parish, female genital mutilation in northern and eastern Africa, the involvement of Christian churches in exorcisms and violence against albinos and other social groups, the destruction of Tawerga by the Libyan rebel thuwar, and violence between Christians and Muslims in the Central African Republic, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Eritrea. In Rwanda, in 1994, the church was a sanctuary for fleeing Tutsis but also a site of many massacres, sometimes with the direct complicity of the church. This led to the war crimes trial of Benedictine nuns, implicated in helping commit genocide.Footnote 5 Ethnic, local-territorial, and clan organizations such as tribes are also suspected of playing a major part in widespread atrocities in northern Nigeria, western Sudan (Darfur) Liberia, and elsewhere.

Other scholars have explored the criminal accountability of noncorporate associations under international law, especially in the context of the “Butare Four” case. Luc Reydams observes that one innovation in the Belgian disposition of that case was to convict an accused for preparing reports that fomented violence against ethnic Tutsis, in an environment that led to the massacres of thousands of them in the region, but which reports were not distributed as a public incitement, and which did not result in a conspiracy finding under Belgian law either; the charge was accessory or accomplice to murder and assassination.Footnote 6 Christopher Harding argues that organizational accountability apart from the accountability of members may be justified when there are organizational dynamics or cultures, independence of organizations from dominant individual personalities, organizational capacity for bilateral or multilateral dealings, and concrete objectives or interests of the organization.Footnote 7 Dov Jacobs has proposed that the phrase “or organizations” be added to Article 25(1) of the Rome Statute, governing the persons over whom the ICC has jurisdiction, currently “natural persons.”Footnote 8

Attribution of individual criminal accountability is seen as a key gap in the ICC Elements of Crimes, as is effective enforcement against clandestine groups such as paramilitaries and against groups created or used to sell arms or buy mineral or oil resources to knowingly finance armed attacks, war crimes, and dissolution of nation-states’ integrity. Aiding and abetting is a theory that is thought to fill some of the gaps left by superior responsibility, direct commission, and other theories that focus on the top or bottom of pyramidal or network-like organized criminality requiring cooperative acts.Footnote 9 However, the theory of joint criminal enterprise leaves a gap for large-scale ethnic cleansing or territorial destruction, and for members of a group who form a common design or plan to commit international crimes where such crimes occur as a natural and foreseeable result of the group enterprise but were outside its original design or plan.Footnote 10

This chapter has three sections. In Section 1, it makes the case that partnerships, trusts, and other unincorporated business associations are not currently covered by Article 46C, and that they should be. In Section 2, it surveys evidence that political and tribal groups, including parties, authorities, statelets, and clan groups are committing crimes within the jurisdiction of the African court and that Article 46C could beneficially apply to them. In Section 3, it concludes with a survey of how religious foundations, trusts, and associations could lead or become complicit in serious crimes, and describes situations in which Article 46C might need to extend to them. The collective crimes that this Section focuses on include genocide, torture, enslavement, recruitment of child soldiers, destruction of sacred sites, corruption, and terrorism, among others less commonly committed or aided by organizations besides corporations.

1. Business Organizations Other Than Corporations Could Exploit Loopholes in Article 46C

Article 46C of the Draft Protocol is entitled “Corporate Criminal Liability.” That provision has also been analyzed by Joanna Kyriakakis, in her separate chapter for this volume. However, it refers in its first paragraph or section to the court having “jurisdiction over legal persons, with the exception of States.”Footnote 11 This raises the question of whether noncorporate legal persons are included in this category.

It appears from the rest of Article 46C, with the exception of section 6, that only corporations may be criminally liable under the statute, as the title of Article 46C also implies. Section 2, for example, states that “Corporate intention to commit an offence may be established by proof that it was the policy of the corporation to do the act which constituted the offence.”Footnote 12 There is no provision made here for assessing the intentions of organizations other than corporations. Sections 3 through 5 and 7 of Article 46C, moreover, refer to attribution of policies and knowledge to a “corporation” or its “conduct” or “culture.”Footnote 13 Section 6, by contrast, states that: “The criminal responsibility of legal persons shall not exclude the criminal responsibility of natural persons who are perpetrators or accomplices in the same crimes.”Footnote 14 The phrase legal persons sweeps more broadly than “corporation,” but as with the preamble, its effect is unclear or arguably nonexistent with it comes to noncorporations, due to the title and sections 2–5, and 7 of Article 46C.

A survey of the other crimes defined in the Draft Protocol provides ample reason to be concerned that organizations other than corporations could exploit loopholes in Article 46C. For example, two or more persons might create a partnership whereby they murder or enslave other persons, but no one individual committed a murder or trafficked in persons with knowledge that multiple such acts had been or were being committed, thereby escaping a crime against humanity charge.Footnote 15 Likewise, such partners could plan to unlawfully and wantonly appropriate private property, while no one partner appropriates “extensive” properties; in such a case, only the partnership, but not the individuals, may be culpable under Article 28D(a)(iv).Footnote 16 Or they could establish a partnership by which one of them commits an unlawful act dangerous to public or private property or the cultural heritage of a state, and the other foments a general insurrection in a state without necessarily committing a particular unlawful act, in which case the individuals might escape prosecution for terrorism under Article 28B even though the partnership’s activities as a whole satisfy the elements of a crime.Footnote 17

Moreover, if some members of an unincorporated association intend to endanger the lives of persons in order to bring about a general insurrection by engaging in armed conflict, while other members take no part in armed conflict but do intend to endanger lives during the insurrection, all the members might avoid terrorism charges.Footnote 18 Finally, if two or more persons associate in a mafia or other corrupt organization to give gifts to government officials in exchange for acts or omissions, but one person gives the gifts, while the other(s) solicit or receive the official acts in exchange for them, none of them might be prosecutable under Article 28I, whereas if they were joined in a corporation and their knowledge and conduct was charged to it, then the corporation would have been subject to such a prosecution.Footnote 19 Some of the individuals in these hypotheticals might be chargeable as inciters, accomplices, conspirators, or joint criminal enterprise participants, but these forms of liability also leave significant gaps and impose often difficult hurdles in prosecuting enterprises.

Business organizations other than corporations also develop policies, practices, and cultures that transcend individual intentions. For comparative purposes, American courses on the subject often begin with an exploration of fiduciary duties to a venture, which Justice Cardozo described as an onerous burden of good faith and fair dealing, whether the venture was a joint enterprise, a partnership, or a trust.Footnote 20 A participant in such a joint project owes the enterprise “undivided loyalty” that is “relentless and supreme,” according to Cardozo’s opinion for the court.Footnote 21 Similarly, in civil-law systems it may be said that a partnership is an agreement among several persons to share in the proceeds from some venture – a winery, for example – and that these persons owe duties of care to one another in carrying out “the partnership business.”Footnote 22 Partners share the profits of ventures; the default rule is that they share equally, while they can contract for different shares.Footnote 23 A trust, at civil law, was a legal relationship in which one person requested another to convey a thing or perform some act – freeing a slave was one prominent example.Footnote 24 In modern societies, another kind of trust emerged to handle complex businesses such as railroads, oil companies, and banks. Some trusts combined so many competing companies into one venture that they stood accused of monopolizing a line of trade, and gave rise to anti-trust law.Footnote 25 Indeed, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act is said to have been the inspiration for charging the Schutzstaffel (the S.S.), the Nazi party, and other substate organizations as criminal actors at Nuremberg.Footnote 26 Today, legal persons include corporations, general partnerships, limited partnerships, trusts, joint stock companies, unincorporated membership associations, syndicates, unions, and other groups.Footnote 27

Like corporations, other forms of companies or entities can obtain knowledge of their representatives’ conduct, and develop policies or imputed activities as a consequence.Footnote 28 There is no reason why the corporate form would be uniquely capable of committing the crimes often acknowledged as involving organizations – bribery, environmental crimes, and genocide.Footnote 29 Indeed, under Canadian law, war crimes and crimes against humanity by “legal persons” – not restricted necessarily to corporations – are subject to actions for international crimes.Footnote 30 Pursuant to the doctrine of universal jurisdiction, a state is entitled to define the persons subject to prosecution for international crimes according to its own law and standards.Footnote 31

Moreover, various “legal persons” other than corporations act as complainants-plaintiffs or as defendants-respondents in civil as well as criminal cases.Footnote 32 By attempting to shape the legal rights and responsibilities of states and other nonstate actors, they arguably open the door to confronting a similar level of criminal accountability as corporations. In order to maintain parity of treatment among corporations, unincorporated associations, and other legal persons, it makes sense to extend the scope of Article 46C to partnerships, associations, foundations, trusts, armies, fronts, political parties, tribes, and other organizations that are not corporations.

2. Political and Clandestine Military Groups, and Their Crimes Against Civilians

A. Social Groups Other Than Corporations Can Commit Organizational Crimes

It may not be the norm that corporations commit grave crimes of international concern. More commonly, the wealthy and powerful – and sometimes the poor and ambitious – form political movements and their armed wings, variously known as parties, fronts, bases, armies, and states.

Many of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century began in this way. Before World War I, a political movement called the Committee of Union and Progress emerged in the Ottoman Empire, dedicated to the aim of seizing the businesses and properties of the empire’s Christian populations, events later known as the Armenian Genocide but actually broader than that. American and British diplomats wrote of the party’s scheme to kill, drive away, and plunder the Christian peoples of the empire.Footnote 33 The National Socialist Worker’s Party of Germany, and elite Death’s Head Units of the Schutzstaffel (S.S.), began as World War I veterans who had sported the silver “death’s head” associated with the aristocratic German cavalry officer prior to the war in order to indicate their trench warfare specialty.Footnote 34 In the 1920s, the Nazis evolved out of a veteran-dominated group called the Freikorps, some of whom – distinguished by their loyalty to Adolf Hitler – wore the silver Death’s Head of the elite trench soldiers.Footnote 35 Nationalism and anti-Semitism often motivated these paramilitary thugs, which grew into a militia of 200,000, including sympathizers.Footnote 36 Joining the Sturmabteilung, the Freikorps units murdered dozens of the Nazis’ political rivals per year, and developed a branch called the S.S. which would take a leading part in the Holocaust.Footnote 37 Hitler’s right hand, Heinrich Himmler transformed the Freikorps into an “organization called the Totenkopfverbände (Death’s Head Units) to run concentration camps and for other special duties.”Footnote 38 In 1939, Hitler told his troops that he was sending the Death’s Head Units to the east to kill without mercy those of Polish race and language. The Units grew to 40,000 persons by 1945.Footnote 39 If the Freikorps and Sturmabteilung had been banned by some international proceeding or institution in the 1920s, countless lives may have been saved.

Scholars use a variety of terms for such politico-military organizations that may seize part of the state’s authority, be deployed by the state, or seek to intimidate or displace the state: death squads, militias, irregular armed groups, vigilantes, civil defense forces, national guards, and paramilitary forces.Footnote 40 Famous examples include the Interahamwe of Rwanda, the Janjaweed of Sudan, the ZANU-PF of Zimbabwe, the Basij of Iran, the “Sons of Iraq,” the shabiha in Syria, and the village guards in Turkey. Moreover, Kenyan women’s organizations blamed militias for the post-election killings, tortures, and mutilations of members of ethnic groups during the month of January 2008.Footnote 41 The International Commission of Inquiry on Libya blamed the Misrata rebel militia or thuwar for ethnically cleansing and killing the Tawergas, referred to as slaves (abid) or blacks by the Misratans in language evoking the Darfur genocide.Footnote 42 Some of the crimes that motivated the creation of the Special Court for Sierra Leone began when Foday Sankoh’s Revolutionary United Front seized diamond fields in the Kono region of the country, advancing from there into other areas where child soldiers were conscripted, sex slaves taken, and killings and amputations were committed.Footnote 43 Even worse crimes (in terms of overall magnitude) took place in Angola, where Jonas Savimbi’s National Union for the Total Independence of Angola won control of the country’s major diamond-producing regions as early as 1992, and traded them around the world unhindered until 1999, when Security Council resolutions impacted the rebels’ $500 million per year in sales.Footnote 44 In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the Rally for Congolese Democracy (RCD-Goma), the National Congress for Defense of the People, and other proxy forces of Rwanda and Uganda have turned the east into a zone of terrible violence and mass rape, alongside the plunder of diamond and mineral resources.Footnote 45

In the 1990s, there were various reports that multinational corporations had acted in concert with local security forces or thugs to commit genocide, torture, and human-rights violations.Footnote 46 For example, the Amungme tribal council in Irian Jaya, the Republic of Indonesia, alleged that mining company Freeport-McMoran Copper & Gold, Inc. acted with local officials to deport his people from their habitat, to destroy this habitat, to commit genocide, and to commit torture and human-rights violations by death threats, surveillance, and other international torts.Footnote 47 Similarly, the residents of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea (PNG), alleged that an Australian mining company violated international law by colluding with PNG forces to blockade their community and ensure that war crimes and racial discrimination were perpetrated against them.Footnote 48 In a case arising out of Burma, a federal court initially ruled that an oil company could be held liable for international crimes involving a joint venture to use forced labor and violence to build a pipeline.Footnote 49 More recently, similar cases have emerged out of Africa.Footnote 50 In one of them, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit concluded that multinational corporations could be sued for having aided and abetted a violation of the law of nations, although the case is now likely to be dismissed for insufficient links to the U.S. mainland under the “touch and concern” test.Footnote 51

The continuing struggle for resources, as well as the rise of political and religious extremism, led to widespread atrocities over the past decade or two. By the second term of President Obama, crimes against children, civilians, cultural heritage, established governments, sectarian and tribal groups, and economic infrastructure were seemingly very common. Schools and shelters for children frequently come under attack, notably in Nigeria but also elsewhere.Footnote 52 Child soldiers continued to be conscripted in large numbers.Footnote 53 Stories of exploitation and enslavement appeared in an alarming number of press and nongovernmental organization (NGO) reports.Footnote 54 For example: “In Nigeria, the abduction of more than 250 school girls, and the killing of boys and girls in attacks on schools by Boko Haram, are tragic examples of how radicalized extremist armed groups are targeting children.”Footnote 55 Conflicts involving atrocities against civilians spread like wildfire from one nation to another, with Libyans traveling to Afghanistan and Iraq to perpetrate terrorist acts, returning to Libya to wage civil war there, driving other Libyans and Libyan arms into the Sahel, sparking conflagrations in those countries among others, and eventually contributing to the creation of the Islamic State.Footnote 56 Enslavement remains distressingly common, for example in Mauritania, Niger, Haiti, India, Pakistan, and the United States.Footnote 57

Churches and mosques were burned to the ground and the traditions of pagan and neo-pagan religions continued to be ground into dust.Footnote 58 Many Buddhist, Taoist, Hindu, and Jewish temples and historic sites would also be destroyed if China, India, and Israel were less powerful militarily. Plunder and the wanton destruction of villages, economic assets, and essential infrastructure continued unabated.Footnote 59 Large populations in diverse contexts lost secure access to food, safe water, sanitation, housing, warm clothing, employment, health, and personal security. Corruption’s role in diluting and diverting the wealth of developing nations into private stashes and foreign accounts persisted. Climate change threatened to kill millions of people.

Nonstate armed groups as well as some states perpetrated mass atrocities affecting children and other civilians.Footnote 60 The UN special rapporteur on torture and cruel, inhuman, or other degrading treatment or punishment highlighted “the exercise of de facto control or influence over nonstate actors operating in foreign territories,” as well as military occupation and more traditional military and law-enforcement operations, as presenting a danger of torture or violations of international humanitarian law, international criminal law or customary international law.Footnote 61

For example, Leila Zerrougui, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on children and armed conflict, has reported that assaults on schools and hospitals happened in many warzones, and were potentially war crimes. Child soldiers continued to be used, and the impact of war on children was worsening.Footnote 62 Ms. Zerrougi commented that children were being revictimized as child soldiers in the Central African Republic even after they had escaped this life once before.Footnote 63 During the same discussion, Nigeria pointed to the DRC and Mali as nations that it called upon to abide by their pledges to end the use of children in conflict.Footnote 64

The Russian Federation remarked that in Syria, “rebels, including Al Qaeda groupings, had forced minors into active participation in the conflict.”Footnote 65 The International Association for Democracy in Africa has observed that despite interventions against it, “Al Qaeda had been victorious since its depredations had fragmented heterogeneous democratic societies on the basis of religion and color, and set communities against each other.”Footnote 66 A US delegate to the General Assembly commented that macabre episodes around the world, “from Syria to the Central African Republic, South Sudan to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, were a reminder that the challenge of ending mass atrocities was greater than ever.”Footnote 67

These trends are visible in UN displacement data. The number of internally displaced persons according to estimates went from 1.2 million in 1982 to 24 million in 1992 to 40 million in 2015.Footnote 68 In 2011, there were many countries in Africa with large populations of displaced and stateless people according to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Angola, Burundi, CAR, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, the DRC, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Libya, Rwanda, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, Western Sahara, and Zimbabwe had 100,000 or more persons of concern to UNHCR.Footnote 69 By 2013, Mali and South Sudan were suffering insurgencies and had been added to the list of countries with 100,000 or more persons displaced or “of concern” to UNHCR, while the displacement crises in Kenya and Libya had abated somewhat. The number of those displaced from the CAR was nearly six times as large as in 2011.Footnote 70 By 2014, Nigeria and perhaps some others such as Kenya and Libya had rejoined the list of countries suffering mass displacement, with 1.2 million internally displaced persons in Nigeria and hundreds of thousands in Kenya and Libya.Footnote 71 More recently, Nigeria’s figure has surpassed two million, driven by Boko Haram’s actions such as attacking schools and enslaving boys and girls.Footnote 72

International and domestic criminal tribunals have belatedly begun to turn their attention to political organizations. In 1999, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia concluded that an individual could be charged with the likely or foreseeable crimes committed by a plurality of individuals who share a common purpose.Footnote 73 Two forms of this “joint criminal enterprise” mode of culpability relax the requirement that the individual intend to commit the underlying crime, requiring instead an intention to further an overall system of criminality, or an intent to carry out a criminal plan along with recklessness as to a crime outside that plan being committed.Footnote 74 In 2004, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia stated that this joint criminal enterprise mode of liability was available in genocide cases.Footnote 75 In 2012, the Special Court for Sierra Leone convicted Charles Ghankay Taylor for actions committed as President of Liberia that “assisted or encouraged” the Revolutionary United Front of Sierra Leone, to commit mass atrocities and plunder of resources including diamonds.Footnote 76 Revealingly, Libya reportedly funded and supplied forces that committed atrocities, whether affiliated with Taylor, Foday Sankoh, or Omar Hassan al-Bashir.Footnote 77 In 2014, the International Crimes Tribunal convicted the leader of a death squad during Pakistan’s 1971 civil war, the Bangladesh War of Independence, sentencing him to death for a massacre of hundreds of persons.Footnote 78 The Supreme Court of Bangladesh upheld the death penalty for the leader of the political movement Jamaat-e Islami, which collaborated with the Pakistanis in 1971.Footnote 79

The problems confronting such individualized prosecutions for organizational policies or crimes are manifold. First, most individuals escape prosecution because they are not extradited or their states do not submit to tribunals’ jurisdiction, and as natural persons they enjoy due-process rights not to be tried and punished with prison terms in absentia.Footnote 80 The accused might even be promoted to high office, as occurred in the DRC, Iraq, and Sudan.Footnote 81 The ICC has announced that it will suspend or abandon investigations, even when referred to it by the Security Council, if the accused are protected by the relevant state and its allies.Footnote 82 Second, even if jurisdiction over the person and the territory exists, the nature of clandestine death squads and other nonstate actors is that they may act independently of their supporters, feign ignorance, avoid wearing uniforms or accepting public responsibility for atrocities, and intimidate witnesses.Footnote 83 Third, as mentioned at the outset of this chapter, an individual accused might well lack knowledge of all elements of the crime, even when the organization would know or intend the remaining elements. Lacking knowledge of an element might preclude Rome Statute culpability.Footnote 84 Finally, a tribunal may find that joint criminal enterprise culpability is not consistent with the principle of legality or nullum crimen sine lege.Footnote 85

Statelets, or regions seeking autonomous governance or being subjected against their will to insurgencies or secessions against the state, can commit international crimes without necessarily being subject to traditional restraints such as World Court jurisdiction or responsible state institutions that might cooperate with the ICC or other tribunal and extradite individuals to it. Yet these statelets can be larger, richer, and more powerful than some states. The Palestinian Authority, for example, had institutions potentially larger and with more resources than those of East Timor (2008 budget of less than $800 million) or Liberia (less than $300 million).Footnote 86 The Islamic State in 2015 grew larger than Scotland or Jordan and had more revenue from oil and antiquities trafficking, as well as donations from persons in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, etc. than East Timor or Liberia, using those estimates from 2008.Footnote 87 The RCD in the DRC may have been larger than the armies of the CAR or Malian governments.Footnote 88 Terrorist movements like the Taliban insurgency in Afghanistan of 1992–1996, the Chechen insurgency in Russia of 1994–1996, and the Kosovo Liberation Army insurgency in Yugoslavia of 1994–1999 were nearly as large as the RCD and larger than the CAR military, for example.Footnote 89 An enormous gap in international law may exist if these territories escape most international judicial proceedings due to not being “states.” A window for clandestine international crimes may be opened for states desiring to undermine or destroy their neighbors, such as Pakistan in Afghanistan, Albania in Yugoslavia, etc.Footnote 90

Other than terrorism evolving into genocide as with the Nazis and the Islamic State, or corruption as defined in 28I, the extension of Article 46C could have implications for the fight against impunity for enslavement, recruitment of child soldiers, destruction of sacred sites, and torture. For example, the nation-states and their officials that perpetrate enslavement as a crime against humanity may be immune from accountability under various doctrines, while private organizations would enjoy no such immunity in some cases.Footnote 91 Government officials who support terrorist groups such as Boko Haram and the Islamic State that recruit child soldiers and destroy sacred sites might also enjoy immunity under limiting doctrines of international and domestic law, for example.Footnote 92 Alleged torturers might make similar arguments, although there is an emerging trend to reject such a ploy.Footnote 93 The persons perhaps least likely to fall into the custody of the African court or the ICC would theoretically be accountable, while officials in league with them would be immune. It may help to recognize the accountability of the group that includes officials or governmental agencies, and nonimmune suspects on the ground, but other persons as well.

B. How Article 46C Could Cover Political and Other Groups

Given these challenges, it would not be that difficult to clarify Article 46C’s application to noncorporate organizations.

A political party, like a partnership or other noncorporate business, could be defined as a legal person. Its policies, knowledge, and conduct could be aggregated or inferred from the statements or decisions of its leaders, or from the repeated actions of its followers. This is already permissible for corporations under 46C, as well as for conspirators, aiders and abettors, and joint criminal enterprise participants under international law and domestic counterparts like the Rome Statute and the U.S. Code. The Rome Statute established criminal responsibility for aiders and abettors and joint criminal enterprises (common purpose/knowing contribution) as well as conspirators.Footnote 94 The U.S. Code includes the War Crimes Act defining grave violations of the Geneva Conventions a U.S. offense, as well as sections making conspiracy and aiding and abetting crimes.Footnote 95 Civil-law systems such as the Netherlands may also recognize the culpability of those who aid states or other actors who commit international crimes.Footnote 96 The Allied Control Council Law No. 10, Article II(a), presumably developed with the participation of civil-law France or even with German legal principles in mind, imposed responsibility on anyone who, while not being accessories or abettors or inciters, “was a member of any organization or group connected with the commission of any such crime …”Footnote 97

There are precedents for creating new remedies for victims of criminal organizations. In the 1960s, the US Congress devoted renewed attention to the problem of La Cosa Nostra, the “Mafia,” and other “mobsters” and organized criminals who engage in “planned, ongoing, continuing crime as opposed to sporadic, unrelated, isolated criminal episodes.”Footnote 98 The problem addressed was that “large amounts of cash coupled with threats of violence, extortion, and similar techniques were utilized by mobsters to achieve their desired objectives: monopoly control of these enterprises.”Footnote 99 The “power of organized crime to establish a monopoly within numerous business fields” was repeatedly raised.Footnote 100 The law Congress passed, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, focuses on criminal organizations which perpetrate a pattern of interstate criminal activities as an enterprise.Footnote 101 Its scope extends to “any person employed by or associated with any enterprise engaged in … interstate or foreign commerce, to conduct or participate, directly or indirectly, in the conduct of such enterprise’s affairs through a pattern of racketeering activity,” or “who has received any income derived, directly or indirectly, from a pattern of racketeering activity or through collection of an unlawful debt … to use or invest, directly or indirectly, any part of such income, or the proceeds of such income, in … the establishment or operation of, any enterprise which is engaged in, or the activities of which affect, interstate or foreign commerce.”Footnote 102 In cases of murder, arson, and fraud, among others, the law “makes it unlawful to invest, in an enterprise engaged in interstate commerce, funds ‘derived … from a pattern of racketeering activity,’ to acquire or operate an interest in any such enterprise through ‘a pattern of racketeering activity,’ or to conduct or participate in the conduct of that enterprise ‘through a pattern of racketeering activity.’”Footnote 103

3. Religious Groups and the Perpetration of Crimes by Legal Persons Other than Corporations

Religious foundations or endowments are legal persons that may have policies, whether in writing or inferred as the most reasonable explanation of their adherents’ conduct.Footnote 104 Such a foundation’s knowledge that an offense is to be committed could be proven with evidence that the foundation or institution had knowledge of the crime being certain or likely, and that the foundation’s culture “caused or encouraged” it.Footnote 105 An institution’s culture could be an “attitude, … course of conduct or practice existing within the … area of the [institution] in which the relevant activities take place.”Footnote 106

International terrorism is an obvious case in which policies, cultures, and practices may make crimes likely because of a religious group’s actions. Article 28G of the Draft Protocol defines “terrorism” to include dangerous crimes “calculated or intended” to intimidate government officials, the public, or a public institution, or to disrupt public services such as schools, or to cause a general insurrection or revolution, or to incite or promote such intimidation, disruption, or insurrection.Footnote 107 There is a loophole, however, for actions by “organized armed groups” that are “covered by” international humanitarian law.Footnote 108 If terrorism rises to the level of civil war, it might cease to be terrorism under this provision, because murder, destruction of public property, kidnapping without trial, torture, rape, and starvation are “covered by” humanitarian law.Footnote 109

One example of terrorism by a religious group that has outraged the conscience of many and led to multinational efforts at suppression and accountability is the campaign by the Lord’s Resistance Army of Uganda (the LRA). Accused of waging 18 years of uninterrupted warfare by 2005, leading to possibly hundreds of thousands of deaths as well as the displacement of 400,000 people across three countries, the LRA is a religious group as its name suggests, and operates as an insurgency and terrorist organization with Sudan’s sponsorship.Footnote 110

Other notable examples of terrorism include the National Islamic Front (NIF), Boko Haram, Al Qaeda Islamic Army, the Al-Nusra Front, Ahrar al-Sham, the Army of Conquest, the Army of Islam, and the Islamic State. Al Qaeda emerged at the confluence of the NIF, the Muslim Brotherhood, and the Wahhabi takfiri movement from Saudi Arabia. The NIF of Sudan grew out of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood until it gained power from a more secular government in 1989.Footnote 111 The Brotherhood’s plan was to clean out the non-Arabs from a “belt” of territory adjoining the majority-Arab populations of northern Sudan, from the region of the Fur and Masalit in the west through the Nuba in the center to the Dinka and Beja further east.Footnote 112 The NIF preached “Salvation” for the nation and called its critics the enemies of Islam, a crime punishable by death.Footnote 113 In 1991, a global congress of Brotherhood-linked terrorist groups took place in Khartoum; its leader proclaimed the goal of erasing national borders and imposing Islamic law across the region.Footnote 114 In 1994, some in the NIF had welcomed Al Qaeda, Hamas, and similar groups from North Africa to Sudan.Footnote 115 Over the next decade, Islamic concepts such as jihad and mujahideen shaped the NIF’s ethnic cleansing of non-Arab populations, even finding a place in the constitution of 1998,Footnote 116 leading one scholar to conclude: “The raison d’être of the atrocities committed by government-supported Arab militias is the racist, fundamentalist, and undemocratic Sudanese state… Khartoum’s genocidal policy in Darfur and the south is also a grab for resources.”Footnote 117 Sudanese training camps allegedly dispatched assassins and saboteurs to Egypt, Ethiopia, and Saudi Arabia.Footnote 118 “Trainees included Egyptians, Sudanese, Eritreans, Palestinians, Yemenis, and Saudis.”Footnote 119 Hamas became the template for turning Muslim Brotherhood branches into terror groups region-wide.Footnote 120 At the same time, the Popular Defense Forces grew in size, later to take key roles in Sudan’s southern and Darfur genocides.Footnote 121 An NIF ideologue reportedly contacted Rashid al-Ghannouchi, whose Al-Nahdah or Ennahda party later took a leading role in the “Arab Spring.”Footnote 122 Western Europe as well as the more secular regimes in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia were suspected to be the targets of all this.Footnote 123

The path from the NIF’s Sudan to Al Qaeda and Boko Haram is not difficult to trace. Sudan and Iran supported the Bosnian secession from Yugoslavia, opening up a base of operations for the Afghan and Arab mujahideen to operate in Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia.Footnote 124 In the 1980s and 1990s, from bases in Afghanistan and Bosnia, Al Qaeda Islamic Army was formed out of various extremist social groups in Arab League countries, notably Egypt and Saudi Arabia.Footnote 125 Litigation attorneys offered to represent 2,000 families of victims of the September 11 massacre by Al Qaeda in New York City and Washington DC. They alleged that the “Saudi interests accused of having knowingly facilitated transfers of money to Al Qaeda were named as the principal defendants [and]… include[d] three Saudi princes, seven banks, and several international charities…”Footnote 126 In 2003, Arabic television networks such as Al-Jazeera carried the Al Qaeda message to kill the Jews and Americans around the world.Footnote 127 In 2008, the United States recognized al-Shabaab as a foreign terrorist organization; the next year, Al Qaeda announced that all Muslims should join its side in the Somali regional civil war.Footnote 128 The Somali capital of Mogadishu had fallen into the hands of Al Qaeda fighters and other jihadists and militias.Footnote 129 Reports surfaced in 2001 of bin Laden profiting from the Sierra Leone rebel diamonds.Footnote 130 Boko Haram began in 2003 and grew powerful in 2009–2010, after members allegedly traveled to Sudan and Somalia and made contact with Al Qaeda, and Boko Haram later launched an uprising that killed 700 in days.Footnote 131

In 2011 and early 2012, Al Qaeda and allied rebels in Syria obtained arms and men from Sudan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Libya, Turkey, and other Persian Gulf, North African, or NATO-member countries.Footnote 132 It did not take long for the rebels to declare a jihad against Syria, a U.N. member state, which they often waged by cleansing Christian populations, destroying churches, executing people without trial, abducting women and other hostages, setting off bombs, looting oil and antiquities and selling them in Turkey and elsewhere, and destroying civilian infrastructure while imposing mass poverty.Footnote 133 Having crossed into Syria from Iraq, the Islamic State of Iraq (and Syria) crossed back into Iraq, cleansing Assyrian Christians, Kurds, and Yezidis from Mosul and the roads to Erbil, Kirkuk, and Baghdad, and enslaving Assyrian Christians and Yezidis as a matter of policy.Footnote 134 This displaced more than 1.4 million people in Iraq, leaving zero out of the 35,000 to 50,000 Christians and few of the 50,000 to 70,000 Kurds and Yezidis who had lived in Mosul.Footnote 135 Radical Sunni clerics who allegedly arrived in northern Iraq from the Persian Gulf countries urged ISIS to cut off water and electricity to Christian villages across the front line, which it did.Footnote 136 The total decline in Iraq’s Christian population – on an indefinite basis – is expected to reach 95%, from 1.4 million at its peak to 50,000 or so. This parallels the expected disappearance of Christianity from the territory of the Palestine Liberation Organization, another alleged participant in the 1993 NIF religious conference, and Christianity’s near-disappearance from Turkey after 1924.Footnote 137 The Islamic State of Iraq inflicted more violence against civilians in 2011, or “one-sided violence,” than the government of Cote d’Ivoire, and more than Libya and Nigeria combined.Footnote 138 It perpetrated more such killings in 2010 than the government of Myanmar and the Janjaweed (part of the government of Sudan), combined.Footnote 139 Its crimes were on a par with those of the LRA.Footnote 140 In 2015, the Committee on the Rights of the Child reported that “children and families belonging to minority groups, in particular Turkmen, Shabak, Christians, Yazidi, Sabian-Mandaeans, Kaka’e, Faili Kurds, Arab Shia, Assyrians, Baha’i, Alawites, who are systematically killed, tortured, raped, forced to convert to Islam and cut off from humanitarian assistance by the so-called ISIL in a reported attempt by its members to suppress, permanently cleanse or expel, or in some instances, destroy these minority communities.”Footnote 141 This campaign was well underway in 2007.Footnote 142

Instead of insisting that all those contributing to jihad in Syria be punished, some persons in Turkey and the territories of the Arab League aided them. Fighters poured in from Qaeda-held area of Libya,Footnote 143 as veterans of Qaeda operations there and in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bosnia, Chechnya, and Iraq joined the insurgency.Footnote 144 Weapons for the terrorists often were paid for by donors from Saudi Arabia.Footnote 145 Instead of targeting that flow, the United States asked Russia to disarm Syria, contrary to its policy on the Iraqi government, its Kurdish region, and the Syrian Kurds.Footnote 146 The death toll may rise from an expected 5,400 or 15,000 from a government victory in 2011 or 2012, to a million or more from decades of terror and response as in Angola, Iraq, and the DRC.Footnote 147

Meanwhile, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Eritrea (EPLF) itself emerged in “1970 in a camp of the Palestinian Fatah movement in Amman, Jordan,” and by 1989 conquered Asmara.Footnote 148

In addition to Sudan and the Palestinian Authority, Eritrea, the CAR, the DRC, and Nigeria have become among the most unfree and persecution-prone places in the world. According to the State Department, Sudan, the CAR, the DRC, and Nigeria merited a 5 on the “Political Terror Scale” in 2010, indicating extreme levels of persecution on a par with Myanmar or North Korea.Footnote 149 Eritrea joined Afghanistan, Chad, Brazil, Burundi, China, Colombia, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, India, Israel and occupied territories, Kenya, Mexico, Russia, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Uganda, and some other countries as warranting a 4 on the scale in 2010.Footnote 150 Eritrea also had one of the worst levels of malnourishment in the world, at 65% of the total population in 2006–2008.Footnote 151

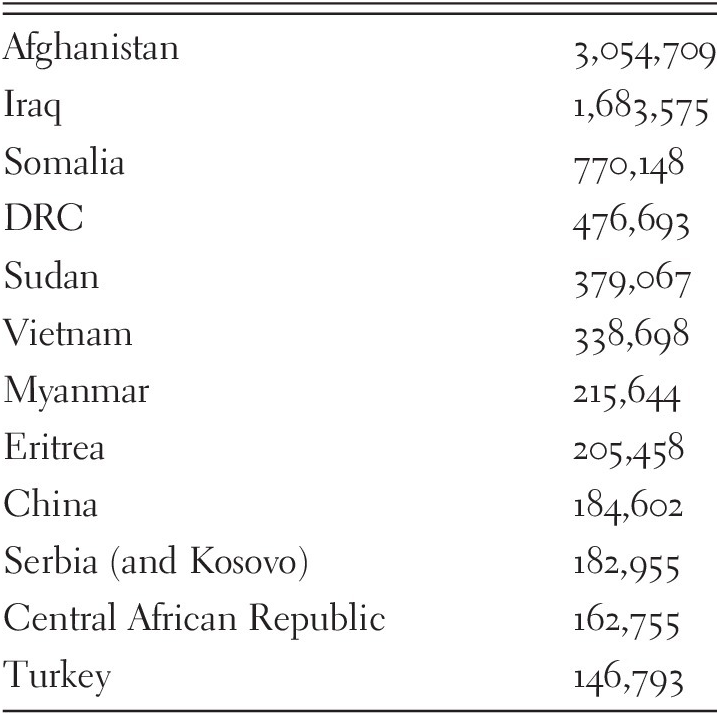

The rise of warlords, rebel armies, terrorist organizations, statelets, and other nonstate threats to population security and economic growth has arguably driven mass exoduses of civilians. Table 10.1 illustrates this phenomenon as of 2010; I discuss above some estimates published since then.

Table 10.1 Refugee Flows by Country of Origin at End of 2010

| Afghanistan | 3,054,709 |

| Iraq | 1,683,575 |

| Somalia | 770,148 |

| DRC | 476,693 |

| Sudan | 379,067 |

| Vietnam | 338,698 |

| Myanmar | 215,644 |

| Eritrea | 205,458 |

| China | 184,602 |

| Serbia (and Kosovo) | 182,955 |

| Central African Republic | 162,755 |

| Turkey | 146,793 |

If entire communities affected by these exoduses at the hands of terrorist groups proved to be unable to reconstitute themselves, this would be a completed genocide according to a broad, originalist reading of the Genocide Convention’s Article II, subsections II(b)–II(d).Footnote 152 Next to Sierra Leone, Somalia, Mali, the DRC, Chad, and the CAR had the worst rate of under-five mortality in the world, each over 164 deaths per 1,000 births, or 16%.Footnote 153

These events led to widespread terrorist massacres in Africa, ranging from the African embassy bombings of 1998 to the Somali university and other bombings, the Kenyan shopping mall massacre, the Boko Haram attacks on Christians and pro-government Muslims in northern Nigeria and neighboring states, and the Islamic State massacres of Copts and other Christians in Libya and Tunisia. In Nigeria, Boko Haram reported receiving support from persons in Saudi Arabia and Sudan.Footnote 154 In Mali, France believed that jihadists such as Ansar al-Dine had received cash from persons in Qatar, who also supported the jihadists in Syria according to the French government. In Afghanistan, the Taliban was receiving arms and money from similar sources as Boko Haram and Ansar al-Dine. The Seleka of the CAR as well as Ansar al-Dine procured weapons released by government stockpiles by the Libyan rebels, which included Al Qaeda members.Footnote 156 In South Sudan, the horrific atrocities of the White Army insurgents against the newly independent and desperately poor state were supercharged by arms shipments from the NIF regime in Khartoum.Footnote 157 Millions are homeless and starving as a result.Footnote 158 The country already has more child soldiers conscripted into fighting than Sierra Leone did at the end of its conflict, or 11,000 children separated from their families and almost 1,500 dead, possibly triggering Article II(e) of the Genocide Convention.Footnote 159

4. Conclusion

Imposing corporate criminal liability will not solve many of the atrocity-related problems confronting the African continent, because nonstate groups other than corporations may be responsible for a preponderance of these crimes. Armies, parties, fronts, and the like came to the fore in the DRC, Sierra Leone, and Uganda, for example. Religiously inspired groups linked to Sudan and Somalia have perpetrated serious crimes in Nigeria, among other places, while groups linked to persons in Sudan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, Libya, Turkey have perpetrated similar crimes in Iraq and Syria, among other places. Such groups can form knowledge of their members’ acts and adopt policies that may violate international norms, just as corporations do. Culpability for noncorporate organizations is necessary to ensure that perpetrators of population-level crimes such as enslavement, child soldiering, forcible transfer, destruction of essential infrastructure or government institutions, or genocide do not enjoy impunity. Moreover, recognizing broader associational responsibility may avoid impediments to the fight against impunity posed by doctrines of intent, immunity, and effects-based tests for crimes such as corruption, enslavement, murder, or terrorism.