Introduction

Evidence of how written input influences developing L2 phonology has demonstrated that orthographic effects are varied, pervasive across different facets of phonology, and persistent into high levels of proficiency (see Bassetti, Reference Bassetti2023; Hayes-Harb & Barrios, Reference Hayes-Harb and Barrios2021 for reviews). Orthographic effects are found in relation to speech perception, processing, and production, with examples of facilitative, null, and inhibitory effects, depending on a range of mediating factors. Studies have predominantly focused on learning across languages which share the same script, usually the Latin alphabet, and where either the known or target language is English. A focus on English can be justified by the global status of the language, in terms of the quantity and dispersion of those learning English around the world, but less so for the Latin script, considering the large proportion of people learning languages that do not share writing systems or graphic representations (Shepperd, Reference Shepperd2024). The current study heeds calls for larger and more diverse samples in language acquisition research (Andringa & Godfroid, Reference Andringa and Godfroid2020; Plonsky, Reference Plonsky2023; Shepperd, Reference Shepperd2022) and specifically aims to improve insights into cross-scriptal orthographic influence on lexical encoding of L2 phonological contrasts.

Written forms may support the encoding and production of difficult L2 contrasts (Erdener & Burnham, Reference Erdener and Burnham2005; Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008; Nimz & Khattab, Reference Nimz and Khattab2020; Rafat, Reference Rafat2015; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2013). However, inhibitory and null orthographic effects are frequently evidenced in contexts where: (1) phonology is not systematically represented by the L2 writing system (Bassetti & Atkinson, Reference Bassetti and Atkinson2015; Hayes-Harb & Barrios, Reference Hayes-Harb and Barrios2021); (2) there is incongruence between grapheme-phoneme correspondences in shared L1 and L2 orthographic scripts (Bassetti et al., Reference Bassetti, Sokolović-Perović, Mairano and Cerni2018; Cerni et al., Reference Cerni, Bassetti and Masterson2019; Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014; Rafat, Reference Rafat2016); (3) the script is unfamiliar to learners (Hayes-Harb & Hacking, Reference Hayes-Harb and Hacking2015; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2016; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015); and (4) a phonological contrast is difficult to perceive (Escudero, Reference Escudero2015; Nimz & Khattab, Reference Nimz and Khattab2020; Rafat & Stevenson, Reference Rafat and Stevenson2018; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015). Negative orthographic effects often manifest in the form of sound additions, deletions, and substitutions, depending on the orthographic knowledge of the L2 learner and how written representations function in the L2 (Bassetti, Reference Bassetti2023). Orthographic effects are also moderated by L2 proficiency, where reliance on L1 knowledge and processes reduces with increasing L2 proficiency (Silveira, Reference Silveira2012; Veivo et al., Reference Veivo, Porretta, Hyönä and Järvikivi2018; Veivo & Järvikivi, Reference Veivo and Järvikivi2013). Notably, research on unfamiliarity often reports a lack of orthographic influence, rather than negative effects. It also seems that shared script incongruence poses more challenges for L2 phonological development than navigating an unfamiliar script (Hayes-Harb & Cheng, Reference Hayes-Harb and Cheng2016; Showalter, Reference Showalter2018; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015). However, more research is needed to make sense of varied findings and how orthographic input relates to perceptibility of the target contrast, L2 proficiency, and literacy experience in a distinct written language.

The present study contributes to this research by investigating the lexical encoding of difficult phonological contrasts by L1 Arabic-speaking adult learners of L2 English, using internet-based methods to include a wide sample of international participants, with varying proficiency in L2 English. To contextualize the predictions and findings of this study, references to written input in models of L2 speech learning are initially outlined. Research investigating orthographic influence on encoding confusable contrasts during novel word learning is then presented, followed by studies exploring cross-scriptal orthographic effects on encoding L2 contrasts.

Models of L2 phonology and orthographic influence

Dominant models of speech learning broadly agree that L2 learners encounter the most difficulty perceiving and producing an L2 sound when it is insufficiently dissimilar to an existing L1 category, and a false equivalence is established (see SLM and SLM-r, Flege, Reference Flege and Strange1995; Flege & Bohn, Reference Flege and Bohn2020; PAM and PAM-L2, Best, Reference Best and Strange1995; Best et al., Reference Best, Tyler, McRoberts, Goodell, Munro and Bohn2007; Tyler, Reference Tyler, Nyvad, Hejná, Højen, Jespersen and Sørensen2019; and L2LP, Escudero & Boersma, Reference Escudero and Boersma2004; Van Leussen & Escudero, Reference Van Leussen and Escudero2015). Minimal reference is made to the influence of written input on L2 phonology in these models. Focusing on the earliest stages of L2 learning, Tyler (Reference Tyler, Nyvad, Hejná, Højen, Jespersen and Sørensen2019) speculatively discusses the predictions of PAM in relation to instructed environments, with specific reference to written input. He observes that written input can be highly effective in supporting the rapid expansion of L2 vocabulary, with the potential unintended effect of reducing opportunities for perceptual learning. A substantial number of words may also be learned from written input alone. Here, the application of L1 phonology is particularly likely if both languages share the same orthographic script. Therefore, early exposure to written input reduces time for sensitization to phonetic differences in speech before establishing a larger vocabulary, exacerbating difficulty discriminating confusable L2 contrasts. It is also observed that written input could support encoding of L2 phonology if the written form unambiguously reflects the phonological contrast. However, this is not the case when the written form does not clearly signal phonological distinctions. There is then little to no speculation around the influence of written input when languages do not share the same script. Arguably, L2LP has also been discussed in reference to orthographic influences on speech perception (Escudero, Reference Escudero2015; Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014). However, it remains unclear precisely how to model orthographic effects on developing L2 phonology (Yazawa et al., Reference Yazawa, Whang, Kondo and Escudero2023).

Another perspective is offered by lexical representation theories, with some using the term “fuzziness” to capture the lack of precision in phonological form and meaning for L2 speakers (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Pandža, Lancaster and Gor2016; Darcy et al., Reference Darcy, Daidone and Kojima2013; Gor et al., Reference Gor, Cook, Bordag, Chrabaszcz and Opitz2021). While the fuzzy lexical representation hypothesis has been primarily applied to the learning of spoken L2 words, theoretical developments, such as the Ontogenesis Model of L2 Lexical Representation (Bordag et al., Reference Bordag, Gor and Opitz2022), offer insight into the interface between phonology and orthography in the L2 mental lexicon. This model highlights the co-activation of representations, simultaneous emergence of representations, and how the strength of mappings between the two domains can be advantageous or disadvantageous. It acknowledges that low-quality encoding of word forms, due to either imprecise phonological or orthographic representations, may result in confusion between similar words. Phonological categorization problems are assumed to underpin phonological encoding difficulties, whereas orthographic depth (Katz & Frost, Reference Katz and Frost1992) and the potential need to develop literacy in a distinct L2 script are relevant and potentially inhibiting factors for orthographic encoding. Although promising, further work is needed to develop testable predictions and increase the explanatory power of this model (Escudero & Hayes-Harb, Reference Escudero and Hayes-Harb2022).

Orthographic influence on confusable contrasts in novel words

Empirical studies offer evidence of varying facilitative and inhibitory orthographic effects on lexical encoding of confusable contrasts. In particular, studies by Escudero and colleagues have demonstrated that orthography can help, but not always. Facilitative effects were demonstrated by Escudero, Hayes-Harb, and Mitterer (Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008), who taught 50 Dutch-English bilinguals pseudowords differing by English vowels /ɛ/ and /æ/, which are confusable for L1 Dutch speakers. Pseudowords were presented with a line drawing, in audio-only or audio+spelling conditions. Results from a visual world eye-tracking task revealed that written input supported encoding of the confusable contrast, where spelled forms triggered asymmetric lexical activation. In contrast, those in audio-only condition exhibited symmetrical confusion, thus lacking a lexical contrast.

Escudero, Simon, and Mulak (Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014) later highlighted the negative effects of incongruence between orthographic systems for L1 Spanish participants learning Dutch pseudowords. Participants (43 Dutch-learning and 30 naïve listeners) were divided into audio-only or audio+ortho groups, then taught 12 Dutch pseudowords. Target words differed by perceptually easy and difficult vowel contrasts, accompanied by congruent or incongruent written forms. Spanish and Dutch share the same writing system (alphabetic), and orthographic script (Latin alphabet), but shared graphemes do not always map to the same phonemes, introducing incongruence between L1 and L2 grapheme-phoneme correspondences. An audio-visual matching task revealed that Dutch proficiency significantly predicted accuracy and audio+ortho participants were more accurate with congruent written input. Importantly, experienced learners outperformed naïve listeners with congruent, but not incongruent, input. Furthermore, participants in the audio+ortho condition outperformed the audio-only groups with congruent input but exhibited lower accuracy with incongruent written forms.

Using the same method and materials, Escudero (Reference Escudero2015) taught Dutch pseudowords to 73 L1 Spanish and 78 L1 Australian English speakers. The English speakers had no experience with Dutch, while the Spanish participants were the same as those in Escudero et al. (Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014) and varied in their Dutch proficiency. Results showed that experience with Dutch predicted higher accuracy when learning new words that differ by confusable sounds. There was no orthographic effect on non-minimal pairs or perceptually easy vowel contrasts, and no effect of language background. Instead, written input improved accuracy for the two relatively easier contrasts among the perceptually difficult pairs. Escudero interpreted this as evidence that “orthography acted as a redundant or extra cue to enhance differences that could already be perceived” (2015, p. 18). This aligns with assertions by Cutler (Reference Cutler2015) that lexically encoded distinctions which cannot be reliably perceived in the input can generate more hindrance than help, such as increased lexical competition and processing delay. Thus, lexical encoding based on segmental distinctions visualized in orthography is only useful if a contrast can be perceptually discriminated.

Related studies have shown that written input can have a salience-enhancing effect for L2 production of difficult contrasts, as well as benefits for retention and retrieval (Bürki et al., Reference Bürki, Welby, Clément and Spinelli2019; Cerni et al., Reference Cerni, Bassetti and Masterson2019; Rafat, Reference Rafat2016). Specifically, pseudowords were produced faster and with fewer errors, as well as more words being learned than based on audio-only input. However, the same studies also report non-target productions arising from incongruence between L1 and L2 grapheme-phoneme correspondences. Thus, both positive and negative orthographic effects can be found in combination, often varying in relation to the mapping congruence between shared scripts. This prompts the question of how orthographic effects vary across distinct scripts, where there are fewer congruence issues but added complications of script familiarity. Key studies on cross-scriptal effects are highlighted in the next section.

Cross-scriptal orthographic effects when encoding confusable contrasts

Recently, increased attention has turned to orthographic influence on L2 phonology across a range of different orthographic scripts and writing systems. Orthographic scripts refer to the specific graphic representation of a language, whereas writing systems broadly represent individual phonemes (alphabets), syllables (syllabaries), or morphemes (logographs) with a single graphic unit (Ziegler & Goswami, Reference Ziegler and Goswami2005). Other writing systems include those that predominantly represent consonants (abjads), found in Arabic and Persian languages, or represent consonants and vowels together (abugidas), which are common in South and Southeast Asian languages. Studies investigating cross-scriptal orthographic influence on L2 phonology initially focused on the influence of entirely unfamiliar written input on lexical encoding of confusable contrasts in early exposure word learning experiments with L1 English speakers (Hayes-Harb & Cheng, Reference Hayes-Harb and Cheng2016; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2016; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015). Attention is currently turning to cross-scriptal influence at different levels of L2 proficiency and with a wider range of language combinations (Han & Kim, Reference Han and Kim2017, Reference Han and Kim2022; Hao & Yang, Reference Hao and Yang2021; Mok et al., Reference Mok, Lee, Li and Xu2018).

Experiments investigating the influence of entirely unfamiliar written input on the lexical encoding of L2 contrasts have resulted in varied findings. Showalter and Hayes-Harb (2015) conducted four experiments investigating whether naïve English-speaking participants benefit from Arabic written input when learning 6 minimal pairs of Arabic pseudowords, differing by the velar-uvular contrast /k-q/ (e.g., [kubu]-[qubu]). Participants were assigned to different input groups, namely: (1) Arabic script vs. audio-only with two speakers (n = 30), (2) Arabic script with explicit instruction (n = 8), (3) Latin script (n = 8), (4) Arabic script vs. audio-only with one speaker (n = 30). Across all experiments, there was no significant difference between the audio-only and Arabic script groups. These findings may reflect the low perceptual salience of the contrast for L1 English speakers, or the small samples. However, and in contrast to predictions, the Latin script group were significantly less accurate than the unfamiliar and audio-only conditions, suggesting orthography-induced transfer, due to <k> and <q> both mapping onto /k/ in English (e.g., “king” and “queen”).

Using a similar research design, Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2016) investigated the influence of different degrees of script familiarity on the lexical encoding of the Arabic uvular-pharyngeal /χ - ħ/ contrast by naïve L1 English speakers. Participants were assigned to one of four script input conditions (n = 21 per group): audio-only, Arabic script, Cyrillic script, or a hybrid script blending the Cyrillic and Latin alphabets (e.g., [χal]—<خال>, <xaл>, <жal>). Results revealed an inhibitory effect of entirely unfamiliar (Arabic script) and partially unfamiliar (Cyrillic script) input, in comparison to other input conditions. As with Showalter and Hayes-Harb (Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015), it is difficult to know the extent to which participant performance related to the perceptual difficulty of the L2 contrast. Offering some insight into this question, Hayes-Harb and Cheng (Reference Hayes-Harb and Cheng2016) investigated the influence of entirely unfamiliar written input on words that differed by both native and nonnative contrasts. They taught 30 naïve L1 English speakers 16 Mandarin pseudowords with either familiar Pinyin or unfamiliar Zhuyin written input. Romanised Pinyin written forms then differed by incongruence, where half were congruent and half were incongruent with L1 grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs) (e.g., [nai]-<nai> or [ɕiou]-<xiu>). Both the Pinyin group and the Zhuyin group performed with ceiling levels of accuracy in the congruent trials of an audio-written form matching task and an audio-picture matching task. However, the Zhuyin group outperformed the Pinyin group when the written form was incongruent with L1 GPCs, demonstrating that, if there is an inhibitory influence of entirely unfamiliar written input, it poses less of a problem than shared and incongruent orthographic forms.

Other studies have demonstrated that the influence of different script input is likely to change at different points in a learner’s development. Hao and Yang (Reference Hao and Yang2021) found that encoding of segmental and tonal contrasts in Mandarin was facilitated by L1-distinct Chinese characters for advanced L1 English learners, whereas naïve L1 English participants were more accurate with L1-shared Pinyin input. Mok et al. (Reference Mok, Lee, Li and Xu2018) also found that distinct script input can support the perception and production of nonnative tonal contrasts, in the context of L1 Cantonese learners of L2 Mandarin. However, their findings add to evidence that distinct script input is of limited benefit when the target language is difficult to perceive, and highlight the need to consider task complexity, proficiency, and script literacy in future research. Beyond the studies outlined here, there is limited research investigating cross-scriptal orthographic effects on the lexical encoding of confusable contrasts, with clear scope for further enquiry.

The present study

This study aims to (1) investigate the influence of cross-scriptal orthographic input on participants’ ability to lexically encode the distinction between pseudowords which differ by a confusable contrast and (2) explore the role of proficiency as a moderating variable. The research question being addressed is:

Does exposure to shared and distinct script input differentially influence the lexical encoding of L2 phonological contrasts during novel word learning?

-

a. Is this influence moderated by the difficulty of the target contrast?

-

b. Is this influence moderated by L2 proficiency?

Adult L1 Arabic-speaking learners of L2 English were tested on their ability to lexically encode two phonological contrasts, /f-v/ and /m-n/, which were chosen for their phonological and orthographic mappings between English and Arabic. As both Arabic and English contain the /m-n/ nasal contrast, words differing by these sounds were expected to pose little difficulty for participants. This contrast is also represented consistently by two distinct letters in both orthographic scripts (<m-n> and <ن-م>). Therefore, L1 Arabic speakers were predicted to perform with high accuracy across all script input conditions when encoding words with this contrast. Meanwhile, the English /f-v/ labiodental voicing contrast is more challenging, as voiced /v/ is not typically found in varieties of Arabic and is expected to assimilate to voiceless /f/.Footnote 1 It was therefore predicted that a consistent representation of /f/ and /v/ as <f> and <v> in English written input could support the lexical encoding of this contrast, especially as there are no issues of incongruence across the visually distinct L1 and L2 written representations. Arabic written input was then predicted to exacerbate the difficulty of encoding the contrast, as both /f/ and /v/ are typically transcribed by the same letter <ف> in Arabic, which would promote the perceived homophony between words based on L1 phonological categories. Finally, it was predicted that performance would improve with higher L2 English proficiency, as learners are likely to have more experience with the nonnative contrast and the L1-distinct script, facilitating improved processing of both auditory and orthographic input.

Following studies by Hayes-Harb and colleagues (Hayes-Harb et al., Reference Hayes-Harb, Nicol and Barker2010; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2016; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015), in order to assess the influence of differing script input, participants were exposed to Arabic spelling, English spelling, or no written input when learning novel words and their pictured meanings. Alongside the L1 Arabic speakers, a group of L1 English speakers, with little to no experience in Arabic, participated in the study, functioning as a control for reliability and validity of the test instruments. It was expected that L1 English speakers would perform well with both contrasts when learned with audio only and with English written forms. However, the L1-distinct and unfamiliar Arabic written forms were predicted to have a null or inhibitory effect on word learning.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Department of Education at the University of York. All participants gave informed consent to take part in the study and received debriefing information upon study completion. Pronunciation videos, aimed at L1 Arabic learners of English and created by the lead researcher, were shared with participants after completing the study as an incentive for participation.

Methods

Participants

The final sample included 114 L1 Arabic-speaking learners of L2 English (86 females, age M = 31.19, SD = 7.7), with a range of English proficiency levels, alongside 117 L1 English speakers (76 females, M age = 35.21, SD = 12.35), with limited experience of learning Arabic (see Table 1). Participants were recruited through personal networks and social media posts, resulting in 180 L1 Arabic participants and 145 L1 English participants beginning the experimental session. Dropout during the session was moderate (L1 Arabic n = 50, L1 English n = 12). A further 11% data loss across groups resulted from exclusions made on the basis of incomplete consent forms, age,Footnote 2 disproportionate distraction,Footnote 3 and lack of same-day completion.Footnote 4

Table 1. Participant background information

1 age in years.

2 completed qualifications.

3 level of ability in L2 English for the L1 Arabic group or L2 Arabic for the L1 English group.

4 scale of 0–12.

Most L1 Arabic participants were from Saudi Arabia (55%), followed by Algeria (12%), Egypt (8%), and Iraq (8%). Most L1 English participants were from the UK and spoke British varieties of English (76%). A range of proficiency-related variables was measured for level of L2 English and L2 Arabic, for both groups. Table 1 reports two key variables of self-reported level and score on a short English test for the L1 Arabic group. Based on the included measures, all L1 Arabic participants were literate in the Latin alphabet.

Material

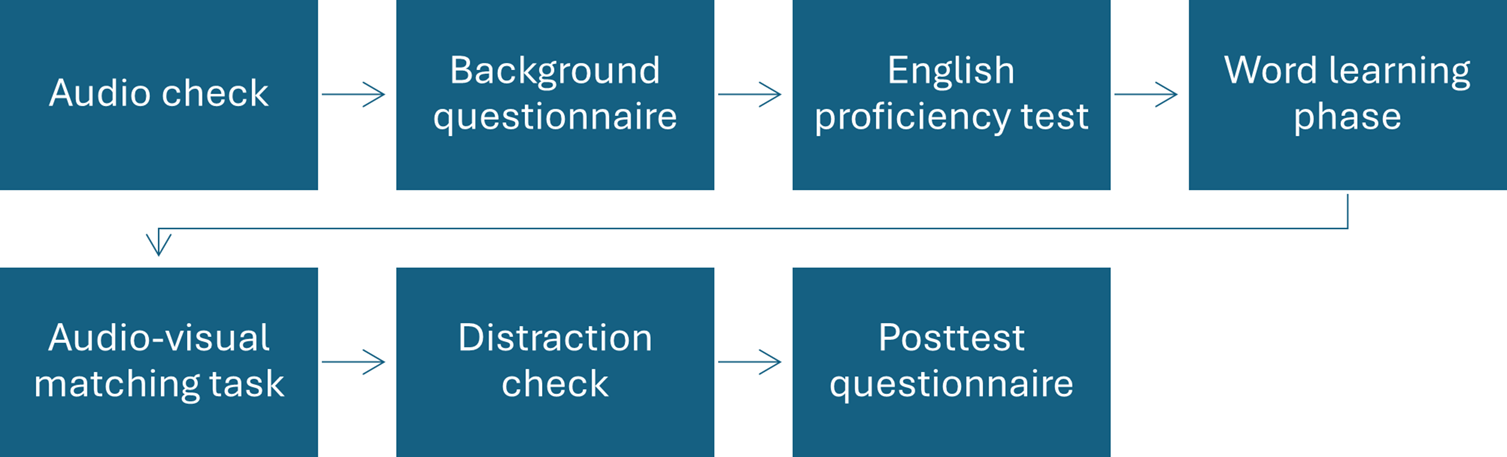

The stimuli consisted of 12 bisyllabic CVCVC pseudo-English words, which were matched with images from the NOUN database (Horst & Hout, Reference Horst and Hout2016). Half differed by /f-v/ and the other half differed by /m-n/. One pair of each phonological contrast was presented in each orthographic input (OI) condition (see Figure 1). The OI conditions included the presentation of the auditory form and image with (1) English OI, (2) Arabic OI, or (3) no OI. Pseudowords were chosen over real words to manage L1 association, L2 vocabulary differences, and ambient exposure outside of the experiment (see supplementary materials for more information). The number of items was chosen in line with previous single-session experiments using pseudowords (Cerni et al., Reference Cerni, Bassetti and Masterson2019; Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008; Hayes-Harb et al., Reference Hayes-Harb, Nicol and Barker2010, Reference Hayes-Harb, Brown and Smith2018; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2016; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015). All audio stimuli were recorded by a female phonetician and native speaker of British English, using a Marantz PMD661MKII handheld recorder and analyzed using PRAAT.

Figure 1. Stimuli overview with /auditory form/, image, and orthographic input.

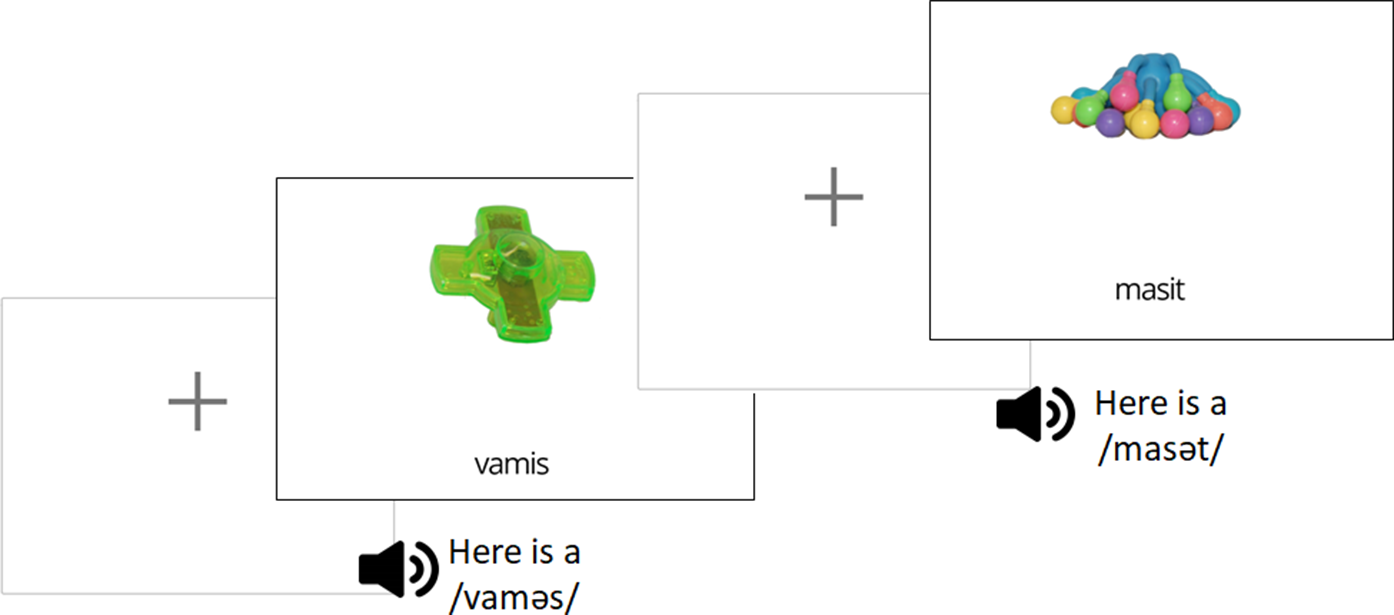

Procedure

The study was built and run using Gorilla Experiment Builder (Anwyl-Irvine et al., Reference Anwyl-Irvine, Massonnié, Flitton, Kirkham and Evershed2020). All participants completed an audio check, background questionnaire, word-learning phase, audio-visual matching task, distraction check, and a posttest questionnaire (Figure 2). L1 Arabic participants also completed a short English proficiency test. The session lasted ~35 minutes for the L1 Arabic group and slightly less for the L1 English group, as there was no English test. All instructions were provided in the participants’ L1, with all written content “read aloud” for both clarity and accessibility. Arabic audio instructions were recorded by a Saudi female L1 Arabic-speaker, in Modern Standard Arabic, while the English instructions were recorded in Standard Southern British English. The analysis reported below focuses on word learning and matching phases, with reference to the English proficiency test and distraction check, so only those parts of the test battery are further outlined.

Figure 2. Experimental flow for the L1 Arabic participants.

English proficiency check

The L1 Arabic participants completed a short English proficiency test, adapted from the Oxford Placement Test, to provide a more objective measure of English proficiency alongside a range of self-reported measures in the background questionnaire. Self-reported measures included English language qualifications, length of English study, age of acquisition, length of stay in an anglophone country, and estimated regular exposure to spoken and written English. The first eight questions of the proficiency test were multiple-choice gap-fill sentences, testing grammar and vocabulary, presented in order of progressive difficulty. Then, two basic open questions, one spoken and one written, required participants to type their answers in English. The gap-fill answers received one point per correct answer, while the open-response questions were given one point for comprehension of the question and another point for the production of a well-formed answer. Correlations were explored between all proficiency measures and accuracy in the matching task, leading to the use of the English proficiency test score when modeling the data.

Word-learning phase

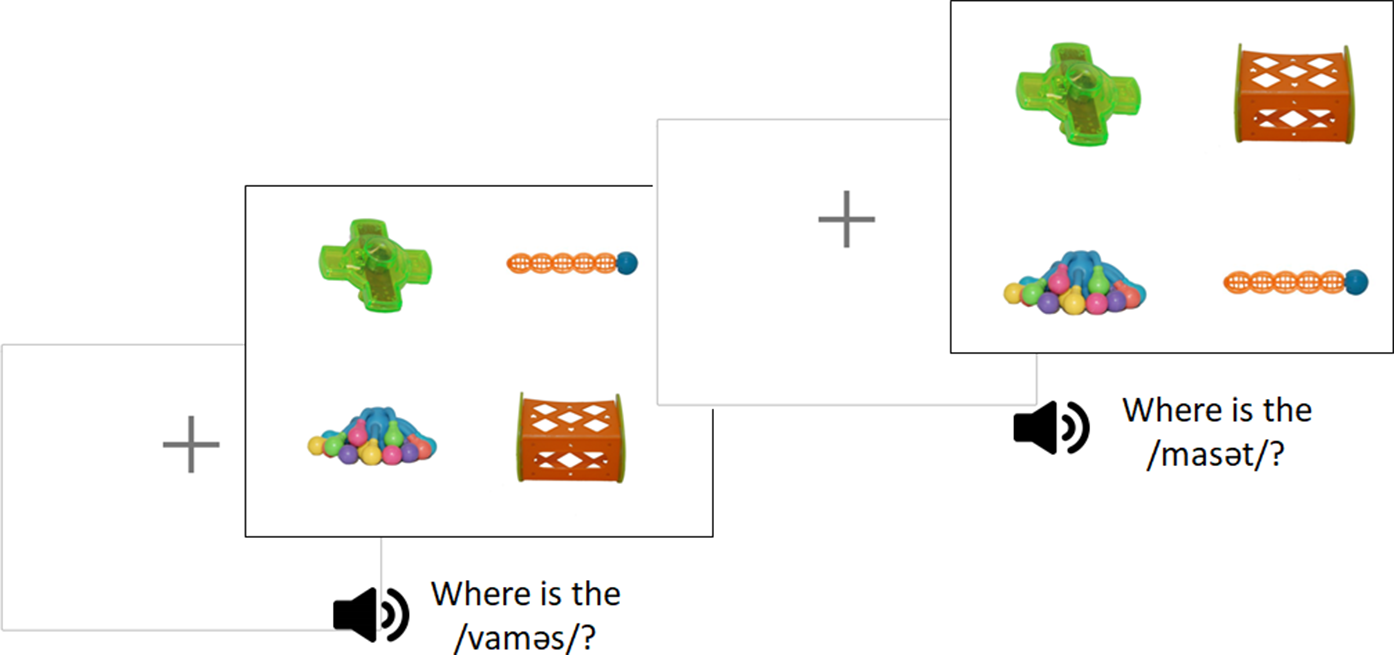

Although the design of word learning and matching tasks is inspired by earlier work (Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Hayes-Harb and Mitterer2008; Hayes-Harb et al., Reference Hayes-Harb, Nicol and Barker2010; Mathieu, Reference Mathieu2016; Showalter & Hayes-Harb, Reference Showalter and Hayes-Harb2015), the present study differs in that testing with feedback was integrated throughout the learning phase, and there was no criterion test after the words were presented. Based on our piloting, this increased engagement, minimized loss of attention, and reduced dropout rates. Adapting the procedure without a criterion test from Rafat and Stevenson (Reference Rafat and Stevenson2018), target items were presented in blocks of two that were non-minimal pair items from the same OI condition, and then tested pairs immediately after presentation.

Each word was presented four times over 24 randomized blocks, so items were presented twice with each possible paired word. Trials were randomized within blocks and in each trial the participant heard the spoken word in the carrier sentence “Here is a…”, alongside seeing the accompanying image and written form for four seconds (Figure 3). After the presentation of each pair, participants saw four images and chose the image which matched the audio for a word they had just learned, embedded in the carrier sentence “where is the…?” (Figure 4). Two of the images were the word pair they had just seen and the other two were distractors. The distractors were never a minimal pair item and never started with the same phoneme as the target item, meaning the distractors were also never from the same OI condition. The second testing trial then played the audio of the other word from the pair and the same images in the grid. There was a 700-ms delay with a fixation cross before each testing screen. The order of the images was shuffled for each trial and the trial order was randomized. After each response, the participant was given immediate feedback on whether they made the correct choice.

Figure 3. Word-learning phase presentation trial sequence.

Figure 4. Word-learning phase testing trial sequence.

The short delay of 700 ms between presentation and first testing trial during the word-learning phase does not fully disambiguate the mechanism that facilitates learning (i.e., short-term memory or phonological learning). However, performance on the matching task after the word-learning phase is the focus of the present study, and here a longer delay was present, including intervening instruction screens and practice trials.

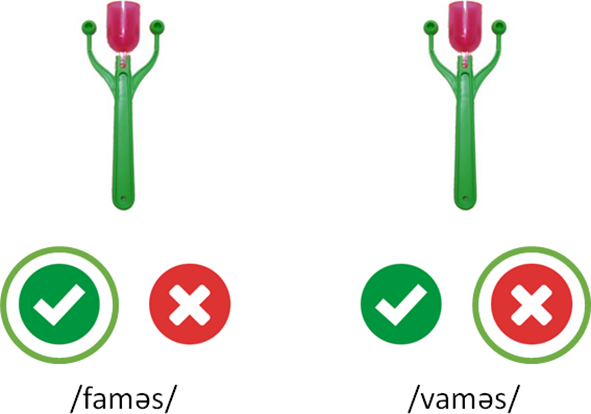

Audio-visual matching task

After completing the word-learning phase, the matching task involved the auditory presentation of each word with either the matching image or the image of its minimal pair item. Participants indicated whether the image and the auditory word matched, yes or no (Figure 5). Each item was presented as an isolated word, twice in a match trial and twice in a mismatch trial, resulting in 48 trials per participant. Trials were randomized and split into eight blocks of six trials. Immediate feedback on the accuracy of the response was given after each trial. It was assumed that participants who were unable to correctly detect when the image and audio matched and mismatched had encoded the minimal pair items as homophonous.

Figure 5. Match and mismatch trial screens.

Distraction check

At the start of the session, participants were instructed to complete the experiment on their own in a quiet environment and ideally using headphones. Embracing the fact that participants would come from a range of backgrounds and were completing the session during varying COVID-19 lockdown situations, we added a short self-reported distraction check to the end of the experiment to estimate the amount and type of disruptions that were experienced by participants. A self-report check was preferred to keep the online session short during COVID-related restrictions. After completing the word learning and testing phases, participants were asked how distracted they were during the experiment on a sliding scale, from “no distractions” to “a lot of distractions” (ranging from 0 to 100). They also reported the type of distractions they experienced from a multiple-choice selection, where they could make multiple selections and add their own additional text. The main distractions reported by those who were included in the analysis related to interruption from a household member (33%), phone notifications (18%), tiredness (18%), and background noise (17%).

Results

The following sections outline the analysis of participant accuracy for the word learning and word testing phases of the study. Emphasis is placed on the results from the L1 Arabic group, where the L1 English group data ensures the validity of the test rather than functioning as a native-like target for the L1 Arabic group. The accuracy data were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) in R, using the lme4 package. For all analyses, a maximal random effects structure was adopted, including varying intercepts by participant and by item. Model comparisons with likelihood tests explored interactions and improved fit with additional fixed effects, based on demographic and environmental variables. Such variables included: age, level of completed education, audio setup, device type, and amount of distraction. Likelihood ratios were calculated using the anova() function in R and compared the full model to a model without each fixed effect and interaction (Winter, Reference Winter2019). The chi-square results reported alongside model estimates indicate whether effects and interactions significantly contributed to the final model.

Word learning

Both groups demonstrated ceiling accuracy scores (L1 Arabic M = .92 (SD = .27), L1 English M = .95 (SD = .22), indicating little difficulty with the initial task of memorizing the words and distinguishing them from either a non-minimal pair item or distractor image. Accuracy scores were further analyzed using GLMMs to assess whether performance was (1) significantly different between the two groups, (2) influenced by the difficulty of the phonological contrasts, or (3) affected by the OI condition. A stepwise procedure was followed to build the model, whereby fixed effects of L1 group, phonological contrast, and OI were initially added to the model. Fixed effects of L1, OI, and phonological contrast were contrast coded to center the variables. The two-level variables of L1 group and phonological contrasts were sum coded (L1 Arabic 1, L1 English -1; fv 1, mn -1). Meanwhile, the three-level factor of OI was Helmert coded to facilitate the comparison between any OI and no OI, then Arabic OI and English OI (Brehm & Alday, Reference Brehm and Alday2022; Schad et al., Reference Schad, Vasishth, Hohenstein and Kliegl2020).

This analysis revealed a main effect of L1, where accuracy was lower in the L1 Arabic group than in the L1 English group (β = –0.29, SE = 0.08, χ2(1) = 14.4, p <.001). There was also a main effect of OI, where accuracy was lower when words were accompanied with any OI compared to the audio only condition (β = –0.27, SE = 0.13, z(11140) = –2.07, p = .04); however, likelihood testing revealed that inclusion of this factor as a fixed effect did not significantly improve the model fit (χ2(2) = 3.67, p = .15). Words differing by the two contrasts or taught with English OI compared to Arabic OI did not significantly predict accuracy. There were also no significant interactions between these fixed effects. However, there was an additional main effect of age, where accuracy was lower when participants were older (β = –0.02, SE = 0.01, χ2(1) = 13.8, p <.001). Table 2 provides a model summary for word learning accuracy.

Table 2. Model summary for word learning accuracy

These results demonstrate that after exposure to target items, followed by a short interval, participants were able to distinguish the words and images with a high level of accuracy from non-minimal pair words and distractor images. It is unsurprising that the L1 English group outperformed the L1 Arabic group, as task demands were higher for the L1 Arabic speakers. This was due to the (1) L2 English-like quality of pseudowords, including nonnative phonological contrasts, (2) embedding of words in L2 English carrier phrases, (3) switching demands between L1 Arabic instruction screens and L2 English trials, and (4) switching demands between Arabic and English orthographies, as the L1 Arabic group were literate in both. Neither the difficulty of phonological contrast nor the orthographic input condition was found to have a significant influence on performance during the word-learning phase, although some indication of orthographic influence was suggested.

Word matching

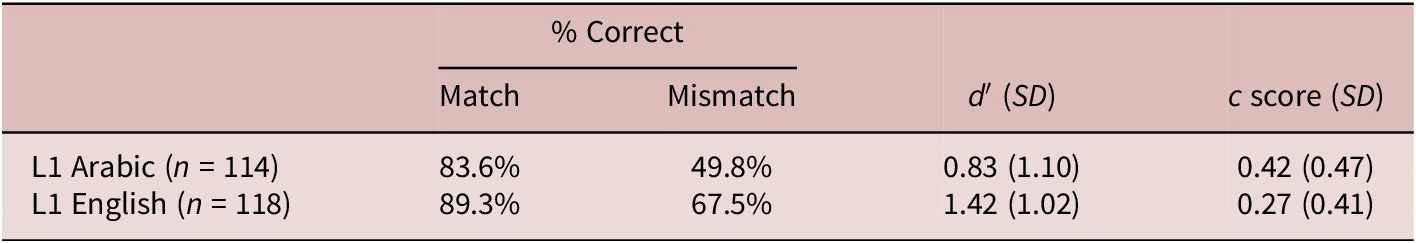

Participant responses in the matching task were binary coded for accuracy with levels “correct,” where either a match or mismatch was correctly identified, and “incorrect” where a match was identified as a mismatch or vice versa. Table 3 offers a summary of mean percentage accuracy for the language groups, alongside d-prime (d′) and criterion scores (c), calculated according to signal detection theory (Stanislaw & Todorov, Reference Stanislaw and Todorov1999). D-prime scores were calculated as d′ = z(hit rate) – z(false alarm rate). The hit rate and false alarm rate were adjusted with the log-linear approach to avoid extreme values of 0 or 1 (Hautus, Reference Hautus1995). In addition, criterion scores assess the direction of bias and are calculated as c = ((z (hit rate) + z (false alarm rate))/2) * 1 (Stanislaw & Todorov, Reference Stanislaw and Todorov1999).

Table 3. Mean % correct in match and mismatch trials, matching task d′ and c scores

As expected, L1 English speakers descriptively outperformed L1 Arabic speakers in percentage correct answers, as well as sensitivity to signal and noise trials (Table 3). Both groups demonstrate a “yes” bias, where words and images were more likely to be accepted as a match than rejected. However, the bias was stronger with L1 Arabic speakers, suggesting that minimal pair items were incorrectly accepted as homophonous more so than the L1 English speakers.

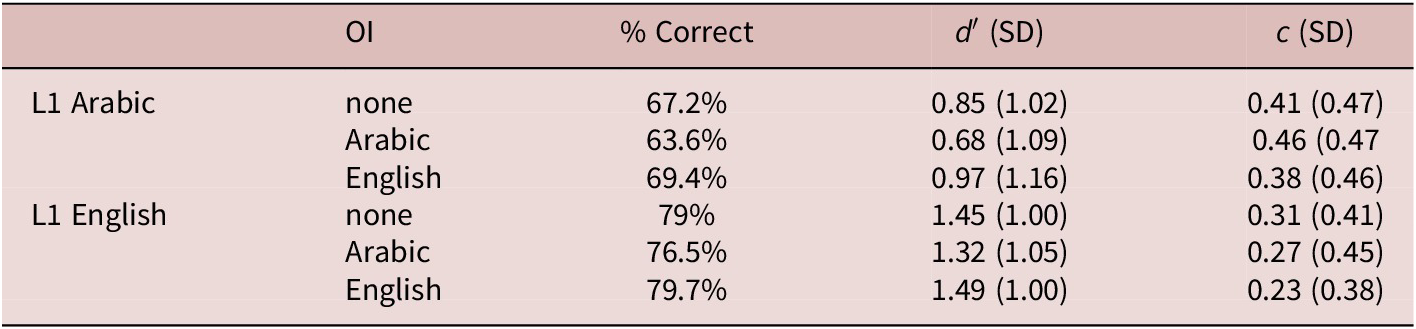

The influence of phonological contrast and orthographic input on correct responses by the two language groups is summarized in Tables 4 and 5. While the accuracy of the L1 English group was higher across both phonological contrasts, both groups found /f-v/ words more difficult than /m-n/ words. This was anticipated for the L1 Arabic group but less so for the L1 English group and is discussed below. L1 English participants were still able to respond to /f-v/ items with above chance accuracy, which was not the case with the L1 Arabic group, who exhibited particularly low d′ and high c scores. The accuracy of the L1 English group also remained higher across all orthographic input conditions compared to the L1 Arabic group. Both groups performed with higher accuracy with English spelling than with Arabic spelling. However, the difference between each OI condition in the different language groups was minimal in comparison to the effect of phonological contrast.

Table 4. Mean % correct responses, matching task d′ and c scores by phonological contrast

Table 5. Mean % correct responses, matching task d′ and c scores by OI condition

GLMMs with L1 Arabic-speaker accuracy

It was predicted that L1 Arabic speakers would be less accurate when distinguishing /f-v/ minimal pair items than /m-n/ items. It was also predicted that this difficulty would be exacerbated by exposure to shared-incongruent Arabic spelling, whereas the distinct and reliable English spelling would visually disambiguate the difficult auditory contrast. However, it was anticipated that this would differ depending on L2 English proficiency. As with the word learning analysis, a stepwise procedure was followed to build the GLMMs in R, whereby fixed effects of trial type (match vs. mismatch), orthographic input, phonological contrast, and proficiency were initially added to the model. The two-level variables of trial type and phonological contrasts were sum coded (mismatch 1, match -1; fv 1, mn -1) and the three-level factor of OI was Helmert coded.

This analysis revealed main effects of proficiency and orthographic input, where accuracy was higher when participants had higher proficiency in English (β = .15, SE = .03, χ2(1) = 16.7, p <.001) and words had been taught accompanied by English spelling compared to Arabic spelling (β = .37, SE = .18, χ2(4) = 8.2, p = .08). However, model comparisons revealed that the inclusion of orthographic input as a fixed effect was only approaching significance. There were also main effects of phonological contrast, trial type, and amount of distraction. Accuracy was significantly lower (1) with words differing by /f-v/ (β = –0.37, SE = 0.09, χ2(3) = 13.9, p = .003), (2) in mismatch trials (β = –0.95, SE = 0.05, χ2(1) = 41.7, p<.001), and (3) when participants reported higher levels of distraction (β = –0.56, SE = 0.27, χ2(1) = 4.3, p = .04). Finally, there was a significant interaction between OI and phonological contrast, where accuracy was lower for /f-v/ words taught with any OI compared to no OI (β = –0.47, SE = 0.18, χ2(2) = 6.4, p = .04). Table 6 provides a model summary.

Table 6. Model summary for L1 Arabic matching task accuracy

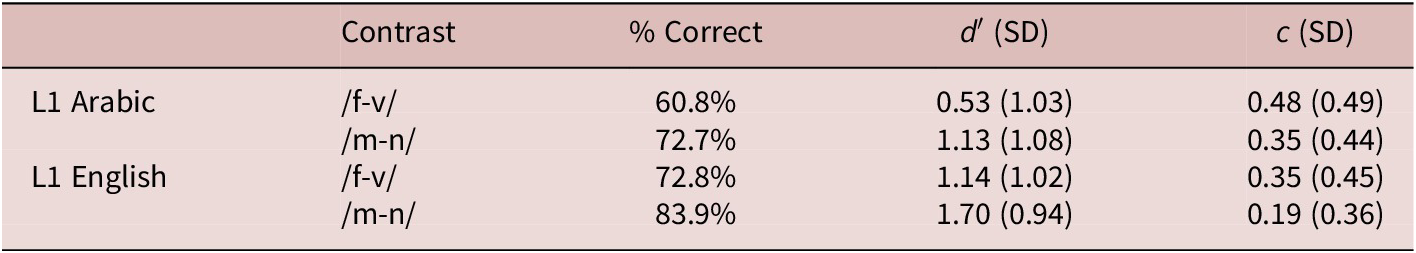

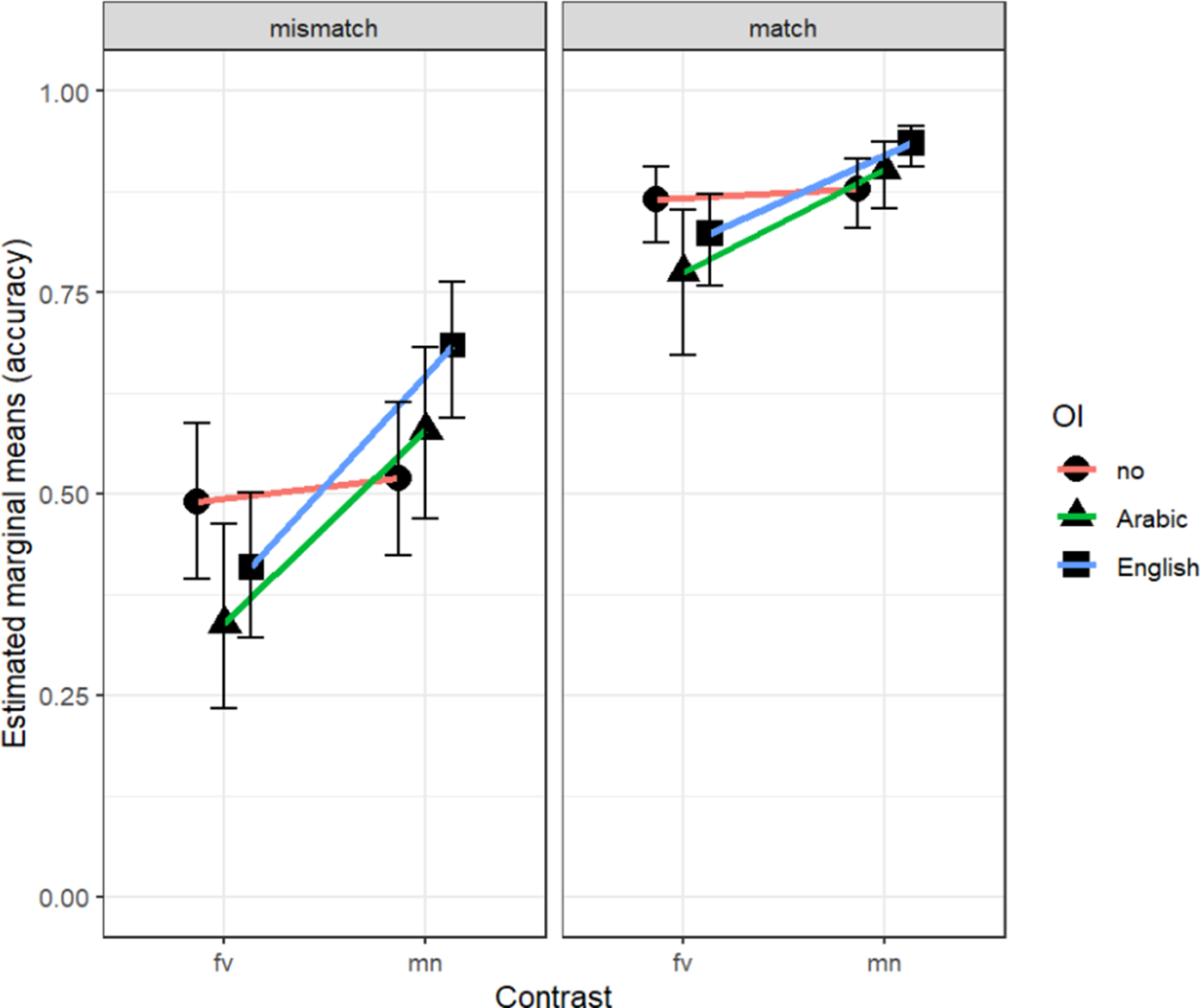

The strongest predictor of participant accuracy was trial type. Due to the anticipated difficulty of the mismatch trials compared to match trials, it was of particular interest how participants performed on those trials. Figure 6 visualizes a slight advantage when words were taught with English spelling compared to Arabic spelling and the added difficulty when items differed by /f-v/. Figure 7 visualizes the interaction between OI condition and phonological contrast, where it was especially clear in mismatch trials that accuracy was significantly lower when /f-v/ words were taught with any OI, compared to audio-only input, while the opposite was true for the easier /m-n/ words.

Figure 6. Model estimated marginal means for L1 Arabic accuracy, by (a) OI and (b) phonological contrast for match and mismatch trials.

Figure 7. Model estimated marginal means for L1 Arabic accuracy, plotting interaction between phonological contrast and OI for match and mismatch trials.

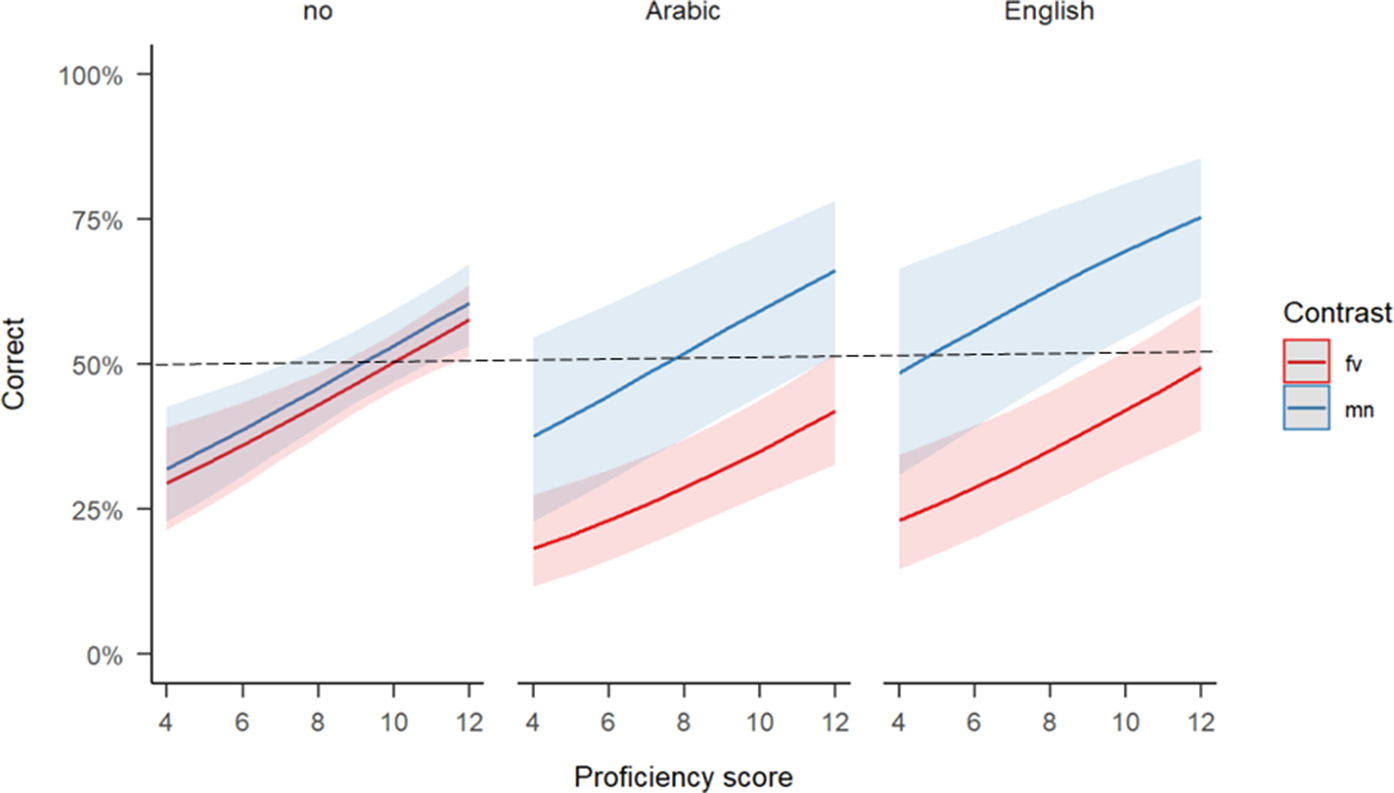

As mentioned, L2 English proficiency significantly predicted higher accuracy. Figure 8 shows the relationship between proficiency and the interaction between OI and phonological contrast. Accuracy was lower for the /f-v/ contrast words with both English and Arabic OI, compared to audio-only input, whilst accuracy was higher for the /m-n/ contrast words presented with any OI. Through the lens of proficiency, predictions for /f-v/ and /m-n/ contrast words were similar in the audio-only condition, even though higher proficiency with the /m-n/ contrast words would have been anticipated across all OI conditions. This implies that encoding both phonological contrasts posed a certain amount of difficulty for the learners, which eased as proficiency increased. However, exposure to OI had a different effect on each contrast. Performance with the easier, well-established /m-n/ contrast was supported by OI, whereas performance with the more difficult, nonnative /f-v/ contrast was inhibited by OI. Notably, even those with the highest proficiency struggle to perform above chance when /f-v/ words are presented with any form of written input.

Figure 8. Model-predicted probabilities for L1 Arabic accuracy, plotting interaction between phonological contrast and OI by L2 English proficiency.

In order to better understand the effect of distraction on performance, further analysis was conducted with a more stringent cutoff of 50% reported distraction. This approach clarified the exclusion of highly distracted participants, while preserving around 75% of the data for additional analysis (N = 83; distraction mean = 8% and range = 0–40%). When running the same models with this dataset, the same factors and interactions showed significant effects, except that distraction was no longer a significant predictor. Additionally, the slight advantage of English input over Arabic input was no longer significant and the interaction between the phonological contrast and orthographic input was strengthened.

GLMMs with L1 English-speaker accuracy

Based on the performance of the L1 English speakers, we can confidently assume that it was possible to complete the audio-visual matching task with a high level of accuracy, after a short word-learning phase introducing the novel words. Indeed, even though performance was lower for both language groups with the /f-v/ items, it was possible to perform the matching task with above chance accuracy across all contrasts and orthographic conditions. Additionally, the high performance for both groups when distinguishing /m-n/ contrast words indicates that the task was not the primary source of difficulty for participants. Therefore, it is assumed that the results from this task indicate the influence of orthography on a difficult nonnative contrast for L1 Arabic learners of L2 English.

The L1 English group were predicted to perform similarly with words differing by both phonological contrasts, as the words followed L1 phonotactic constraints and differed by well-established L1 contrasts. It was also predicted that orthographic information in Arabic spelling would be inaccessible, as none of the participants reported literacy in Arabic, leading to an inhibitory or null influence of Arabic spelling. In comparison, performance with the English spelling was predicted to be higher. As indicated by the descriptive overview of accuracy, these predictions were not entirely borne out. The results were analyzed further using GLMMs, following the same procedure as reported above for the L1 Arabic data.

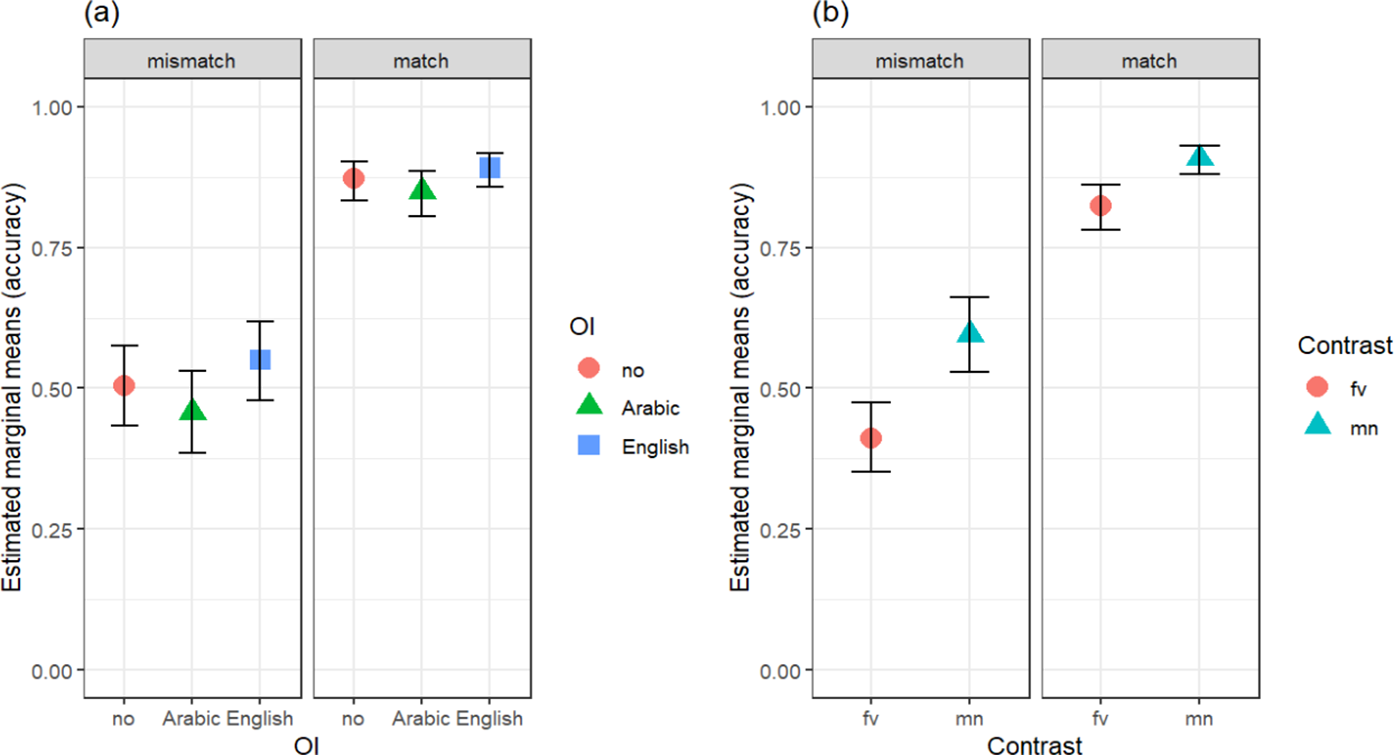

This analysis revealed a main effect of OI, where accuracy was higher when words had been taught accompanied by English spelling compared to Arabic spelling (β = .26, SE = .13, χ2(4) = 11.2, p = .02). There were also main effects of phonological contrast, trial type, and age. Accuracy was significantly lower (1) with words differing by /f-v/ (β = –0.47, SE = .07, χ2(3) = 23.5, p <.001), (2) in mismatch trials (β = –0.80, SE = .08, χ2(1) = 26.1, p <.001), and (3) when participants were older (β = –0.02, SE = .01, χ2(1) = 9.3, p = .002). Finally, there was a significant interaction between OI and phonological contrast, where accuracy was lower for /f-v/ words taught with any OI compared to audio only (β = –0.40, SE = .11, χ2(2) = 9.2, p = .01). The model summary is provided in Table 7.

Table 7. Model summary for L1 English matching task accuracy

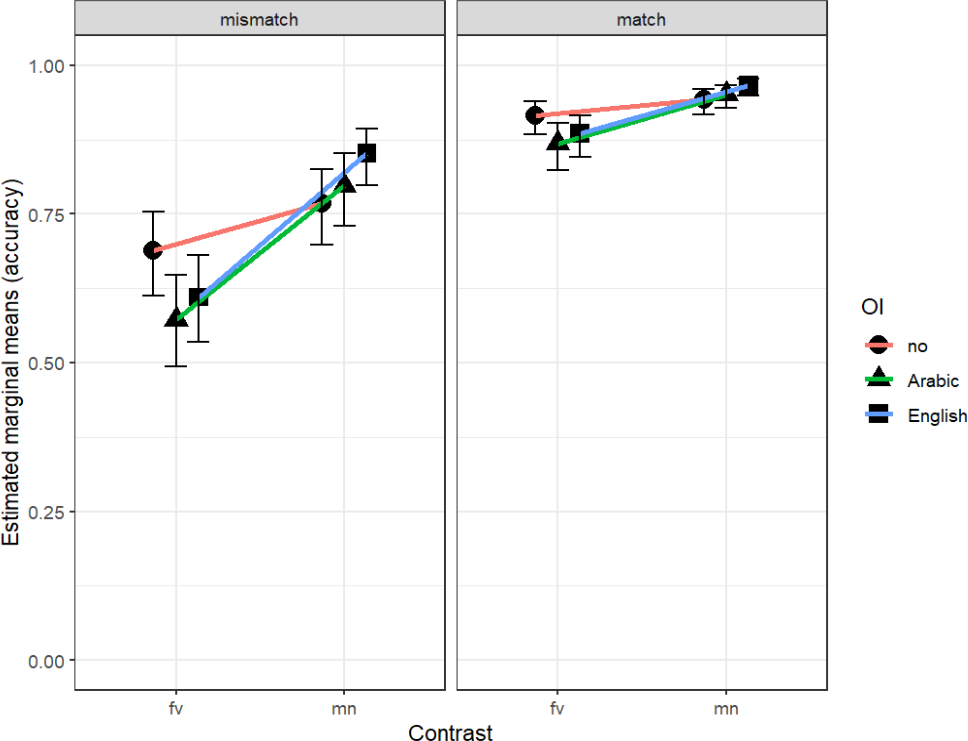

The largest predictor of participant accuracy was trial type and the model predictions were plotted for the main effects of OI condition and phonological contrast, in both trial types separately (Figure 9). These figures visualize the slight advantage when words were taught with English spelling compared to Arabic spelling, and the difficulty when words differed by the /f-v/ contrast. Predicted accuracy remains above chance for items differing by /f-v/. However, this could indicate a problem with the items themselves, which is addressed in the discussion. The interaction between contrast and OI condition shows that difficulty was exacerbated by exposure to OI, as accuracy was significantly higher when participants were exposed to the audio only for /f-v/ words (Figure 10). Critically, the L1 English speakers were able to perform the matching task with above chance accuracy for the words differing by /f-v/, meaning that while the task was difficult, it was possible. The interaction between phonological contrast and orthographic input, where accuracy was highest for /f-v/ words in the audio-only condition, further indicated that the contrast was sufficiently salient to lexically encode the contrast in memory, yet not sufficiently salient to benefit from the added orthographic input.

Figure 9. Model estimated marginal means for L1 English accuracy, by (a) OI and (b) phonological contrast for match and mismatch trials.

Figure 10. Model estimated marginal means for L1 English accuracy, plotting interaction between phonological contrast and OI for match and mismatch trials.

Discussion

This study addressed the question: Does exposure to shared and distinct script input differentially influence the lexical encoding of L2 phonological contrasts during novel word learning? In line with predictions, L1 Arabic-speaker accuracy was higher when words were presented with English spelling compared to Arabic spelling. However, a significant interaction between OI condition and phonological contrast revealed that accuracy was lower for /f-v/ words that were presented with any form of OI, compared to audio-only. In other words, any OI inhibited accurate encoding of items differing by the confusable /f-v/ contrast, whereas accuracy was supported by any OI when items differed by the easier /m-n/ contrast. Furthermore, while accuracy improved with increased proficiency, even the highest proficiency participants struggled to perform above chance with words differing by /f-v/ accompanied by any written input. These results suggest orthographic influence is moderated by the perceptual difficulty of the target contrast. Thus, even when OI is familiar and letters map transparently to sounds, it is not always useful in visually disambiguating the speech signal but rather enhances only what is already perceptible to the learner.

These findings align with proposals by Escudero and colleagues (Reference Escudero2015; Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014), who argue the supportive influence of OI is limited by the perceptibility of target contrasts. Cutler (Reference Cutler2015) also reiterates that without a firm perceptual basis, a lexically encoded distinction via orthography may not reduce L2 confusion when perceiving and processing spoken language. Knowing the distinction exists may not be enough to perceive it correctly in speech. As such, explicit instruction, drawing further attention to an orthographically represented contrast, is likely to be of most benefit when the contrast has already been phonologically established to some extent, perhaps with higher levels of proficiency. Mixed findings regarding the effects of explicit instruction in this context would benefit from further academic attention (Hayes-Harb & Barrios, Reference Hayes-Harb and Barrios2021).

Escudero and colleagues (Reference Escudero2015; Reference Escudero, Simon and Mulak2014) report a null influence of shared orthographic input when learning difficult contrasts, rather than a negative influence. However, like the present study, an inhibitory effect was reported by Mathieu (Reference Mathieu2016), who compared performance across a range of different script conditions. He found that written input conditions accompanying a confusable contrast, which varied in familiarity based on the L1 script, did not differ from each other but together exhibited an inhibitory effect on accuracy encoding a confusable contrast, compared to no orthographic input. This was attributed to the “foreign-ness” of the written input, as participants had no experience with Arabic or Cyrillic scripts. In the present study, English OI could be conceived of as “foreign” to the L1 Arabic speakers. However, familiarity and foreignness are ill-fitting terms for learners with varying English proficiency and literacy experience, illustrating the benefit of articulating the degree of visual overlap between scripts to separate established L1 knowledge from developing L2 experience.

The marginal advantage of L1 English written input across both target and control contrasts may be indicative of Arabic speakers’ high levels of proficiency in English, and a more macro-level congruence between script and English-like nature of the words. By congruence here, we refer to the case where the presentation of L1 transliteration to L2 lexical items acquires a peculiarity and additional level of processing for biscriptal L2 learners who are used to learning new English words accompanied by English spelling. For example, Hao and Yang (Reference Hao and Yang2021) reported increased word learning accuracy for L1 English speakers with higher proficiency in L2 Mandarin words, and found that advanced learners in a Chinese character group generally outperformed those in a Romanised Pinyin group. This tendency was also apparent for the intermediate learners, whereas naïve learners were significantly more accurate with Pinyin than characters. Improved accuracy with characters for advanced learners was interpreted to reflect learners’ accustomed way of learning new vocabulary, as character-based literacy practices become more prevalent as proficiency increases.

Focusing also on proficiency, Veivo and colleagues (Reference Veivo, Porretta, Hyönä and Järvikivi2018; Reference Veivo and Järvikivi2013) explored orthographic bias in adult L2 lexical knowledge and imprecise phonological representations. They posit that late L2 learners’ orthographic representations may be more robust than their phonological representations, although this bias can decrease with proficiency. For example, as proficiency increases, they observed a reduced reliance on L1 knowledge and less impact of orthographic information on L2 spoken word recognition. Given these findings, the steady improvement and lack of interaction between written input and proficiency in the current study could indicate that as proficiency increased, participants were better able to navigate interference from L1 Arabic written forms and integrate the L2 English written forms with phonological representations in memory. However, more systematic exploration of these questions, such as using online techniques like eye-tracking found in work by Veivo and colleagues, would be valuable to better understand these processes.

Considering the difficulty that advanced learners faced when encoding a confusable contrast with both shared and distinct orthographic input, these findings support recommendations against an overreliance on early orthographic input, or at least some pedagogical caution, in instructed environments (Hayes-Harb et al., Reference Hayes-Harb, Brown and Smith2018; Rafat & Stevenson, Reference Rafat and Stevenson2018; Sokolović-Perović et al., Reference Sokolović-Perović, Bassetti and Dillon2019; Tyler, Reference Tyler, Nyvad, Hejná, Højen, Jespersen and Sørensen2019). Criticality and caution are recommended here, rather than avoidance, for two reasons. Firstly, it is both implausible and often unnecessary to completely restrict early exposure to written forms in most educational settings and literate societies. Secondly, written forms can support language learning broadly and phonological development specifically. For example, in the present study, accuracy improved for the easier /m-n/ items with any OI in comparison to audio only, further indicating that orthographic influence depends on the perceptibility of target items. Thus, it is hypothesized that when learners can perceptually distinguish lexical items, OI functions as an enhancing cue that supports lexical encoding. However, when learners are not able to perceptually distinguish novel lexical items, OI causes interference or distracts from attending to the necessary phonetic detail. It would therefore be beneficial for teachers and learners to reflect on the mappings between both the phonology and orthographies of the target and known languages when leveraging written input during early language instruction.

This interpretation of the findings and call for caution echoes Tyler’s (Reference Tyler, Nyvad, Hejná, Højen, Jespersen and Sørensen2019) speculative extension of PAM-L2 to instructed settings. In line with the recommendations above, Tyler predicted that alphabetic orthographies which clearly signal a phonological difference may help to tune into phonetic differences in the speech signal. However, when the orthographic signal is not clear “their internal rehearsal of the pronunciation of L2 words via orthography may reinforce a perception that the L2 phonemes are equivalent rather than distinct” (Tyler, Reference Tyler, Nyvad, Hejná, Højen, Jespersen and Sørensen2019, p. 617). While there is a lack of detail in what Tyler means by a “clear” orthographic signal, these ideas are supported by empirical findings, in the present study and others (Hayes-Harb & Barrios, Reference Hayes-Harb and Barrios2021), regarding both (in)congruence and perceptibility. However, further research is needed to formalize predictions and the lack of reference to non-alphabetic orthographies or learning across distinct writing systems in this and other theories of speech learning remains notable. As such, this article joins the growing chorus seeking theoretical developments which take the influences of written input on instructed second language speech learning into account (Bassetti et al., Reference Bassetti, Sokolović-Perović, Mairano and Cerni2018; Nimz & Khattab, Reference Nimz and Khattab2020; Rafat & Stevenson, Reference Rafat and Stevenson2018; Yazawa et al., Reference Yazawa, Whang, Kondo and Escudero2023). Further, methodological innovation is called for, including mixed methods approaches (c.f., Bassetti et al. Reference Bassetti, Mairano, Masterson and Cerni2020, who combined experimental and qualitative methods to explore participants’ perceptions of orthographic effects on their developing phonology).

We acknowledge several limitations in the current study. The number of stimuli and trials across conditions was limited. Furthermore, while the difficulty encoding the /f-v/ words was predicted for the L1 Arabic group, the lower-than-expected (albeit above-chance) performance with this contrast by the L1 English group suggested an issue of perceptual salience, as well as L1 perceptual bias. Closer analysis of the audio stimuli revealed only partial voicing of the word-initial voiced labiodental fricative /v/, as is expected in an intervocalic position in connected speech (see supplementary materials). This could go toward explaining the reduced salience of the contrast. Future research would benefit from an increased number of trials and stimuli per condition and/or investigating a different confusable contrast, such as /b-p/, to see if findings are replicated. Future applications of this study design may also consider the advantages of within- and between-subject designs for stimuli presentation. For example, participants noted the additional processing demands of switching between different script inputs during word learning, which was a more artificial aspect of the design.

While the use of online data collection was beneficial for recruiting a large international sample when lab-based research was not available, it is important to acknowledge potential differences in stimuli presentation. As noted in Table 1, participants completed the study with varying devices and audio equipment, which could have impacted participant performance. We conducted analyses controlling for these variables, but they did not significantly predict performance or improve the fit of the model. For further discussion around conducting auditory perception studies online see Eerola et al. (Reference Eerola, Armitage, Lavan and Knight2021). The inability to control the level of distraction during participation in the present study was also a limiting factor. However, self-reported information on the amount and type of distraction proved insightful, especially as the level of distraction proved to be a significant predictor of L1 Arabic group accuracy in the matching task. This then demonstrates the usefulness of collecting distraction data, both for informing exclusion procedures and to include as part of analysis. Since conducting this study, many advances have been made and best practices established for conducting online research. As such, future research on this topic would benefit from implementing a more objective measure of attention, such as an easy control task. Additionally, targeted assessment of the memory and executive function of participants would clarify the extent to which task performance relates to these individual differences rather than orthographic encoding. A future study could also explore the effect of a longer interval between stimulus presentation and response in the word-learning phase, to disambiguate between learning mechanisms.

Arguably, single-session word learning studies offer limited insight into learning and reflect processes more associated with short-term memory (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Takashima, Van Hell, Janzen and McQueen2014), especially without a consolidation period of sleep (Dumay & Gaskell, Reference Dumay and Gaskell2007; Gaskell et al., Reference Gaskell, Warker, Lindsay, Frost, Guest, Snowdon and Stackhouse2014). For this reason, it is difficult to tease apart phonological learning and short-term memory in our design. Others argue that lexicalization of newly learned words can take place rapidly and without consolidation (Kapnoula & McMurray, Reference Kapnoula and McMurray2016), and there is clear precedent in the field to draw conclusions based on single-session studies. That being said, to gain more insight into learning over time, studies should move beyond single sessions. Additionally, the inclusion of perception and production testing in an extended battery of tests would prove useful to further investigate how orthographic influence relates to the development of robust mental representations of confusable L2 contrasts. This would also help address continuing queries around the relationship between proficiency, L2 phonological development, and orthographic input. Proficiency is a multilayered concept; thus, it would be useful to investigate relevant individual differences, including measures of language experience and exposure, cognitive function, auditory processing, and language learning strategies.

Conclusion

Cross-scriptal written input is influential when adult L2 learners lexically encode phonological contrasts in novel L2 words. This study contributes to evidence that orthographic effects are pervasive across L1 shared and distinct orthographic scripts and into high levels of L2 proficiency. Furthermore, evidence of orthographic effects on L2 phonology with a far larger sample than typical of previous studies demonstrates that orthographic influence is robust and deserves greater attention when investigating and theorizing in relation to L2 phonological development. Contrary to predictions, the present study did not clearly demonstrate the benefits of reliable, distinct L2 written input when learning a confusable L2 contrast. In fact, the findings presented here suggest that exposure to any orthographic input, irrespective of L1 overlap or systematicity of representation, had an inhibitory effect on the ability to lexically encode a difficult-to-perceive phonological contrast. In light of the persistent difficulty encoding confusable contrasts with orthographic input, caution around a reliance on written input is particularly recommended for the earliest stages of language learning.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263125101514.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Data availability statement

Materials for this study are openly available through Gorilla open materials (Arabic version, https://app.gorilla.sc/openmaterials/630644; English version, https://app.gorilla.sc/openmaterials/631053). Audio recordings and images are also available on IRIS (https://www.iris-database.org/details/1CYtr-XnPKS). Data supporting this study is openly available on OSF (https://osf.io/3t9wd/). Rmd files with the analysis of word learning and matching data are also available on OSF (https://osf.io/xhqzb/). The experiment in this article earned Open data and Open Materials badges for transparent practices.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge participants who contributed to this project, in spite of all that was taking place in the world during the COVID-19 pandemic. We are also grateful for the insightful comments and suggestions from anonymous reviewers and Editor Kazuya Saito on earlier versions of the manuscript. This project was funded by a UKRI ESRC Doctoral Studentship (ES/P000746/1) awarded to Louise Shepperd.