A few recent studies have analyzed the effects of administrative reforms on state-building capacity, economic development, and urbanization (Becker, Heblich, and Sturm Reference Becker, Heblich and Sturm2021; Bai and Jia Reference Bai and Jia2023; Chambru, Henry, and Marx Reference Chambru, Henry and Marx2024). In this paper, we exploit one of the most ambitious state-building and reform processes that occurred in Europe in the first half of the nineteenth century (Davis Reference Davis2006), that is, the administrative reform implemented in 1806 by the Napoleonic authorities in the Kingdom of Naples, as a historical experiment to analyze the effects of a radical reform on long-run development. The Napoleonic reform established, for the first time, the division of the 12 “historical” provinces of the Kingdom of Naples into 40 districts—that is, intermediate geographical-administrative units between the provinces and the municipalities. Within each district, a city was selected on the basis of its “spatial centrality” as the district capital.Footnote 1 The identification of the districts and the selection of their capitals by the Napoleonic authorities was one of the major innovations of the 1806 reform.

We exploit the exogeneity in the selection of the district capitals to assess whether municipalities that experienced such a status change, having been selected as the seat of the Sub-Intendancy, gained a population growth premium due to acquiring supra-municipal administrative functions by law, thereby becoming “centers of power” at the local level. The introduction of such functions, coupled with population growth resulting from the initial influx of bureaucrats, soldiers, police officers, and their families, and subsequent immigration inflows from the rest of the Kingdom of Naples, had a positive impact on the urban and industrial development of these cities.

Two underlying mechanisms can reasonably be hypothesized to explain the relationship between administrative reforms, population growth, and urban and industrial development: the provision of public goods and transport network accessibility. First, population growth may have increased the demand for local public goods, thereby positively influencing urban and industrial development. Additionally, as district capitals assumed new supra-municipal administrative functions, they likely played a central role in connecting provincial and central government authorities with peripheral municipalities within district boundaries. Consequently, transport network accessibility was essential not only for the efficient transmission of information, laws, and regulations but also helped promote urban development and industrialization.

We assemble a large and original dataset, combining historical data at the municipality level from 1648 to 1911, and analyze development at the city level in terms of both population dynamics and industrialization up to the year 1911.Footnote 2 We find that district capitals gained a long-lasting population growth premium compared with non-capital municipalities and experienced higher industrial development both before and after the Italian unification that occurred in 1861. We corroborate our results through a number of robustness tests—among which kernel matching and synthetic control estimation approaches—and placebo exercises based on randomized treatment assignments. We also test the proposed mechanisms and find that district capitals tended to provide more public goods (e.g., hospitals, kindergartens, secondary schools) to the local population both before and after the Italian unification and were more connected to the railway network. Finally, we carry out a long-run analysis and provide evidence regarding a battery of current outcomes concerning population growth, agglomeration economies, human capital endowment, and economic performance.

Our paper contributes to two literature streams. The first concerns the state capacity and its role in influencing economic development (Besley and Persson Reference Besley and Persson2011). A basic dimension of state capacity is bureaucratic and administrative capacity (Savoia and Sen Reference Savoia and Sen2015; Acemoglu and Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2019). While this dimension has been widely investigated in terms of skills, competences, and abilities of an administrative system to achieve its objectives (Evans and Rauch Reference Evans and Rauch1999; Rauch and Evans Reference Rauch and Evans2000), the literature has only recently focused on the effects of administrative reforms on economic development (Bo Reference Bo2020; Becker, Heblich, and Sturm Reference Becker, Heblich and Sturm2021; Jia, Liang, and Ma Reference Jia, Liang and Ma2021; Bai and Jia Reference Bai and Jia2023; Chambru, Henry, and Marx Reference Chambru, Henry and Marx2024).Footnote 3 In this respect, we also contribute to the literature studying the effects of Napoleonic reforms (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Cantoni, Johnson and Robinson2011; Buggle Reference Buggle2016; Postigliola and Rota Reference Postigliola and Rota2021; Dincecco and Federico Reference Dincecco, Federico and Patrick2022). The reform of the administrative systems, based on the “French model,” not only originated in the so-called Napoleonic administrative tradition (Peters Reference Peters2021) but also affected the processes of state-building and economic development of certain European countries.Footnote 4

Second, our paper is related to the literature on the origins of the Italian regional divide (e.g., Cafagna Reference Cafagna1989; Federico, Nuvolari, and Vasta Reference Federico, Nuvolari and Vasta2019; Barone et al. Reference Barone, Chilosi, Ciccarelli and De Blasio2025) and specifically on the determinants of economic geography in continental southern Italy. The literature mostly follows a dualistic approach and suggests how the North-South divide: (i) had its roots in the Middle Ages (Galasso Reference Galasso2007); (ii) was characterized by different urban systems, consisting of “a polycentric urban system in the North and two parasitical urban centers (Naples and Palermo) in the South” (Accetturo and Mocetti Reference Accetturo and Mocetti2019, p. 206); (iii) declined over the Renaissance (1400–1600) but persisted until the Italian unification in 1861 (Chilosi and Ciccarelli Reference Chilosi and Ciccarelli2022); and, (iv) increased substantially only since the late nineteenth century. We contribute to this literature by considering growth differentials within the Italian Mezzogiorno, with a focus on urban developments induced by the 1806 Napoleonic administrative reform, when, for the first time, “the introduction of districts marked the appearance of the State in the countryside” (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990, p. 84, our translation).Footnote 5 In this respect, we contribute to a better understanding of how historical institutional and administrative choices—besides traditional factors identified in urban economics, such as natural advantages—can shape the development and evolution of the concentration of manufacturing and service activities and the spatial agglomeration of households, workers, and firms (Smith and Kulka Reference Smith and Kulka2024).

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Napoleonic Administrative Reform of 1806

Before 1806, during the Bourbon rule, the Kingdom of Naples was divided into 12 “historical” provinces (Galasso Reference Galasso2007). The presence of the state was mostly concentrated in provincial capital cities where the judicial courts were located (Giustiniani 1797, vol. I). Administrative powers at the local level were instead distributed among a plurality of actors, including feudal lords, religious orders, and aristocratic families (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990).Footnote 6

This picture radically changed with the entry of the French Revolutionary army into Naples on 15 February 1806, which marked the beginning of a new vision of society and the design, in terms of organization and functioning, of a proper modern state (Davis Reference Davis2006). Indeed, Joseph Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon and King of Naples between March 1806 and July 1808, undertook a profound process of institutional transformation in the Kingdom of Naples.

The reforms of August 1806 marked the transition from a sovereignty based on feudalism and its privileges to one based on the homogenization and standardization of administrative norms, practices, and structures (Peters Reference Peters2021), as well as the establishment of an administrative system structured on different geographical layers (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990). Two laws played a crucial role in this process: the one abolishing feudalism (2 August 1806) and the one introducing a new administrative system (8 August 1806).

The law of 8 August 1806 established the division of the Kingdom of Naples into 13 provinces, each with its capital city. However, the radical innovation concerned the division of the 13 provinces into 40 districts. The primary challenge for the Napoleonic authorities was delineating the geographical boundaries of the districts and choosing their capitals.Footnote 7 In line with the French model (Peters Reference Peters2021), the district was conceived as an intermediate geographical-administrative unit between the province and the municipality, and the selection of district capital cities was guided by the “spatial centrality” of a municipality within a district.Footnote 8

During the “French decade” (1806–1815), the number of provinces further increased from 13 to 14, and the number of districts rose from 40 to 49. Certain municipalities became district capitals, as some districts were created ex novo through a process of territorial reorganization, while other municipalities within existing districts simply underwent a change in status.Footnote 9

This process of reforming the administrative geography of the Kingdom of Naples was accompanied by the assignment of supra-municipal administrative functions to provinces and districts, thereby shaping the new administrative hierarchy of the state at the spatial level. Civil and financial administration, including tax collection, as well as police and public security functions, were managed at the provincial level by the Intendant. At the district level, the primary official was the Sub-Intendant, with her seat located in the capital city of the district.Footnote 10 The reform established that the Sub-Intendant was “charged with executing and enforcing the orders she shall receive from the Intendant and giving her opinion on grievances and petitions” (Law No. 132 of 8 August 1806, Title III, Article 2, our translation) originating from the municipalities of the district. Despite the Sub-Intendant’s subordinate role and dependence on the Intendant overseeing the respective province, these officials brought for the first time in the history of the Italian Mezzogiorno the presence of the state at the local level, notably into the district capitals (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990). Furthermore, officials, civil servants, soldiers, and policemen were dispatched to the district capitals to assist with the activities of the Sub-Intendants.

In this sense, the 1806 Napoleonic reform impacted the administrative geography and changed the prevailing urban hierarchy of the Kingdom of Naples. It also played a pivotal role in shaping economic geography within the Italian Mezzogiorno.

Administrative Reformism during the Restauration Period: 1816–1860

On 9 June 1815, the Congress of Vienna officially endorsed the reinstatement of the Bourbons in the Kingdom of Naples. In December 1816, Ferdinand I ascended to the throne as King of the Two Sicilies, a kingdom representing the union of the Kingdom of Naples (i.e., the continental Mezzogiorno) and the Kingdom of Sicily (i.e., the island of Sicily).

The Napoleonic tradition and administrative geography of the “French decade” were upheld during the Restoration period (1816–1860). The only notable change was the expansion of the number of provinces in the former Kingdom of Naples from 14 to 15, and the number of districts from 49 to 53, which occurred in 1816. Subsequently, between 1817 and 1860, in a few cases, the status of district capital was reallocated within these existing districts.Footnote 11

As established by the Napoleonic reform, each province was governed by an Intendant. The role and the administrative functions assigned to the Sub-Intendant were also confirmed by the Bourbons: supra-municipal administrative functions remained concentrated in the district capitals, where civil servants, officials, soldiers, and policemen resided and supported the Sub-Intendant’s activities (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1997).

Administrative Reformism in the Aftermath of Italian Unification

The Italian unification process (1859–1861), led by the Kingdom of Sardinia—roughly corresponding to the present-day regions of Piedmont, Liguria, and Sardinia—was accompanied by administrative reforms that laid the foundation of the public administration system of the new Kingdom of Italy (Pavone Reference Pavone1964). This process took place in two phases during the period of 1859–1865.

In the first phase, the Kingdom of Sardinia ratified and adopted the Rattazzi Law, which was extended to the territories gradually annexed to the country between 1859 and 1861. This law integrated the administrative geography of the Napoleonic tradition, which was founded on four distinct sub-national units: the province, the district, the mandamento, and the municipality.Footnote 12 The number of provinces of the former Kingdom of Naples was increased from 15 to 16, while the number of districts was raised from 53 to 56 with the creation of a new province; by contrast, no municipality experienced a status change within already existing districts. The law also assigned specific administrative functions to provinces and municipalities, yet it did not allocate any administrative functions to the district and the mandamento.Footnote 13

The second phase of this process occurred when the Italian Parliament approved the Lanza Law in 1865 concerning the administrative unification of the Kingdom of Italy. This law assigned a variety of supra-municipal administrative functions to district capitals, which served as the residence of the Sub-Prefect—corresponding to the role of the Sub-Intendant of the Napoleonic and, subsequently, Bourbonic eras. In particular, the number of administrative functions assigned to district capitals by the Lanza Law was considerably higher compared with those attributed by the Napoleonic and Bourbonic laws.

The presence of the Sub-Prefecture in the district capital cities had two fundamental roles. First, it functioned as a “center of powers” within the province, exercising specific functions such as overseeing public security and justice, managing public health matters, and issuing permits and licenses. Second, especially so in the pre-railway era, it served as a pivotal “node” at the local level for receiving and transmitting information, managing administrative procedures, and implementing political acts, regulations, and laws originating from the Prefect and the central government. Moreover, district capitals played a central role in coordinating various administrative activities at the local level and establishing connections between peripheral municipalities within the district boundaries and the authorities at the provincial and central government levels.Footnote 14

THE SELECTION OF DISTRICT CAPITALS IN 1806

In this section, we discuss the exogeneity of the criteria adopted by the French authorities in 1806 to delineate districts and select their capital cities, and assess the role that local lobbies and pre-existing economic and infrastructural characteristics at the municipality level could have played in this process.Footnote 15

Our study region includes the territories in continental southern Italy that were part of the Kingdom of Naples (Figure 1).Footnote 16 We rely primarily on a new set of population data ranging from the seventeenth century to 1911, and mapped the historical settlements of the Kingdom of Naples listed by Giustiniani (1797–1805, vols. I–X) in the municipalities recorded in the 1911 Italian population census provided by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT). We thus consider municipalities in their 1911 configuration as the reference to reconstruct municipal observations starting from the pre-Napoleonic period.Footnote 17 This procedure allowed us to identify 1,808 municipalities existing in 1911 and located within the 1806 boundaries of the Kingdom of Naples. However, five municipalities were enclaves of the Papal State in 1806, and another 35 municipalities existing in 1911 were established after 1806, and we were unable to identify previous human settlements. Therefore, we consider a starting sample of 1,768 municipalities that belonged to the Kingdom of Naples at the time of the Napoleonic reforms and still existed as municipal administrative units in 1911.Footnote 18

Figure 1 THE KINGDOM OF NAPLES AND THE OTHER ITALIAN PENINSULA’S STATES IN 1806

Notes: The map shows the Kingdom of Naples and the other states existing in 1806 within current Italian borders.

Source: Elaboration on Centennia Historical Atlas Research Edition.

The Creation of Districts and the Selection of District Capitals

In August 1806, Napoleonic authorities redrew the administrative geography of the Kingdom of Naples by creating 40 districts. This process was regarded as a “very hasty” territorial engineering operation (Russo Reference Russo and Russo2007, p. 118) during which French authorities “had to invent” districts, first, and then district capitals (Bonini Reference Bonini and Aimo2009, p. 293, our translation). The French authorities designed and created ex novo the 40 districts based on the information available in the geographical dictionaries written by Galanti (1786–1794), Sacco (1795–1796), and Giustiniani (1797–1805), with the assistance of some local geographers (Ciccolella Reference Ciccolella2000). It is not surprising that these authorities had significant “freedom of action” in delineating the districts, considering that these geographical units were completely new for this state (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990, p. 84, our translation).Footnote 19

A key feature of the 1806 Napoleonic reform concerned the criterion adopted for the selection of district capitals. The criterion adopted was guided by the “spatial centrality” of a municipality within a district.

The limitations and weaknesses of the road network and related infrastructures in the Kingdom of Naples (Ciccolella Reference Ciccolella2000), as well as the presence of natural obstacles (e.g., rivers, streams, and mountains), justified this selection criterion, which was “rationalized” by the Napoleonic authorities with the idea that a capital city should generate “the greatest convenience or least inconvenience to the population … of the district” (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990, p. 96, our translation).Footnote 20

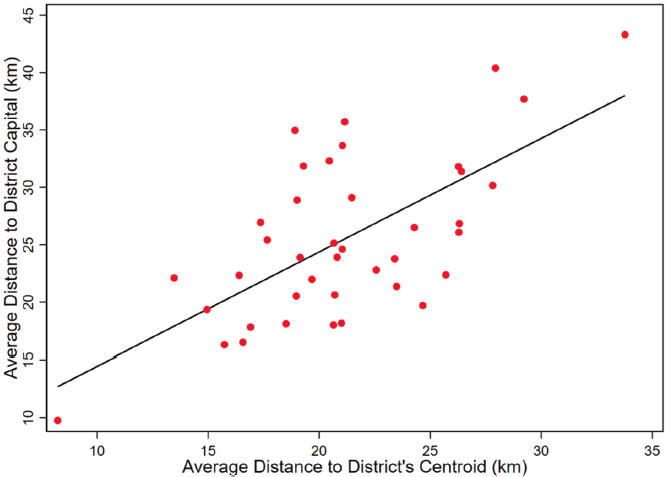

Our identification strategy leverages the exogeneity of the criterion used by the French authorities for selecting district capitals: that is, spatial centrality. The centroid of a district, which serves as the measure of spatial centrality within a district, is independent of the spatial distribution of population or economic activities within a district; it is solely determined by the geographical shape of the district (Campante and Do Reference Campante and Do2014). As such, once the geographical boundaries of each district are set, the centroid of a district is an arbitrary location that should not affect any outcomes at the district level. Therefore, we should expect a positive correlation between the location of the centroid of a district and the location of its capital city. Figure 2 does indeed show a strong positive correlation between the average distance (of municipalities within a district) to the centroid of the district and the average distance (of municipalities within a district) to the district capital—that is, between the centrality of districts’ centroid and the spatial centrality of district capitals.Footnote 21 This evidence further corroborates the claims of the historical literature that Napoleonic authorities primarily selected district capitals in 1806 based on their geographical centrality within districts.

Figure 2 DISTRICTS’ CENTROID AND SPATIAL CENTRALITY OF DISTRICT CAPITALS

Notes: The plot shows the correlation between the average distance (of municipalities within a district) to the centroid of the district and the average distance (of municipalities within a district) to the district capital for the 40 districts and district capitals established by the French authorities with Law No. 132 of 8 August 1806.

Source: Elaboration on digitized cartography provided by ISTAT.

The Role of Local Lobbies

It could be argued that the selection of district capitals may also have been influenced by a lobbying process involving local elites, such as feudal lords or supporters of the French regime. In this section, we investigate this possibility.

We begin our analysis by examining the historical evidence. The 1806 administrative reform was accompanied by two other fundamental reforms aimed at eliminating the influence of feudal lords, namely the law abolishing feudalism and the law establishing the land tax (Villani Reference Villani, Galasso, Romeo and Mozzillo1986). The law of 2 August 1806 abolished feudalism in the Kingdom of Naples without any compensation for feudal jurisdictions, tax privileges, or immunities. Additionally, a new fiscal system based on a progressive land tax was implemented in 1806.Footnote 22 As in France, the abolishment of feudalism served as “the juridical premise for everything that followed,” and it allowed the establishment of “the absolute sovereignty of the state” (Davis Reference Davis2006, p. 164). Consequently, these reforms allowed—and led to—the implementation of the French system of local administration in the Kingdom of Naples.

This historical evidence suggests that feudal lords could play no role in influencing the decisions made by the Napoleonic authorities in selecting district capitals. We test this empirically by relying on information on whether a municipality was under a feudal lord in 1797 drawn from Giustiniani (1797–1805, vols. I–X). We do not find a statistically significant correlation between a municipality’s feudal status in 1797 and the probability of being selected as district capital in 1806—see Column (1) of Table C2 (Online Appendix C).

Another potential local lobby could have been represented by the first-instance supporters of the French regime, namely those who took part in the Neapolitan Revolution of 1799, which saw the occupation of vast areas of the Kingdom of Naples by Napoleon’s troops and the proclamation of the Neapolitan Republic, which lasted from 23 January to 22 June 1799 (Rao Reference Rao2021). These individuals could have claimed “rights” and, therefore, could have influenced the choice of district capitals in 1806: indeed, French authorities and the senior officials of the new government established in Naples may have been influenced by these local elites through political or masonic connections (Davis Reference Davis2006). We thus investigate the role played by the “republican patriots” under the rationale that the selection of district capitals may have been influenced by the local elites comprised of patriots born in municipalities that exhibited greater adherence to the “republican values” of the Revolution, potentially serving as a form of recognition for their support to the French army in 1799 (Rao and Pavone Reference Rao, Pavone, Giarrizzo and Iachello2002). Thus, a significant presence of patriots born in a municipality, motivated to promote their hometown and leverage their ties with French authorities, could potentially explain the choice of that municipality as a district capital in 1806.Footnote 23

We capture the potential role played by the “republican patriots” connected with the French authorities by exploiting three different types of data. First, we have digitized the list of 119 members of the Neapolitan Republic who were sentenced to death by the Bourbon tribunals between 1799 and 1800, including information on their municipality of birth (Cuoco Reference Cuoco and Nicolini1913, pp. 369–75). We consider the share of executed patriots born in a municipality over the total number of executed patriots as a proxy for the relative importance a municipality may have had during the Neapolitan Revolution in supporting the French armies and, thus, to capture the potential recognition for its participation in the Revolution. Second, we have digitized the list of 875 patriots sentenced to exile by the Suprema Giunta di Stato in 1800, including information on their municipality of birth.Footnote 24 We consider the number of exiled patriots born in a municipality weighted by the distance between their municipality of birth and Naples, under the rationale that, once back in the Kingdom of Naples, such patriots could have potentially influenced the selection of district capitals based on their relative proximity to the French authorities and the new government headquartered in the city of Naples. We do not find a statistically significant correlation between a municipality’s “patriotic” nature in 1799 and the probability of being selected as district capital in 1806. By contrast, we find a negative and statistically significant association between a municipality’s distance to its district’s centroid and the probability of being selected as district capital in 1806—see Columns (2), (3), and (4) of Table C2 (Online Appendix C).

We have also digitized information provided by Rao and Pavone (Reference Rao, Pavone, Giarrizzo and Iachello2002) regarding 190 municipalities that, during the Neapolitan Revolution of 1799, were temporarily “republican,” having been under French rule for periods ranging from 15 days to six months. This information is available only for five provinces of the Kingdom of Naples, but allows us to identify also those municipalities—namely, 44 municipalities—that proclaimed themselves “republican” voluntarily; that is, before receiving orders from the central authority or the entry of French troops (Rao and Pavone Reference Rao, Pavone, Giarrizzo and Iachello2002). We find no evidence that self-proclaimed municipalities were more likely to be selected as district capitals by the French authorities in 1806 in recognition of the support shown during the Revolution. By contrast, we still estimate a negative and statistically significant association between a municipality’s distance to its district’s centroid and the probability of being selected as district capital in 1806 (Table C3, Online Appendix C).

Finally, we assess the potential lobbying role senior officials who directly engaged with the institutions of the new regime (e.g., State Councilors and Ministers) could have played by influencing the decisions made by the French authorities in 1806. This analysis also rules out the possibility that senior officials exerted political influence to favor their hometown municipalities as district capitals—see Online Appendix C.

The Role of Economic and Infrastructural Characteristics

It is also possible that the choice of certain cities was influenced by pre-existing economic and infrastructural factors. Indeed, some cities might have been selected because they were experiencing the early stages of a proto-industrialization process or were better integrated into the Kingdom’s road network, which was the most important transport infrastructure of that time.

We test for the potential role played by these pre-existing conditions through two exercises. As a first exercise, we estimate the probability that a municipality would be selected as the district capital as a function of economic and infrastructural characteristics, namely, population density in 1797, proto-industrialization in 1797, distance to the closest ancient Roman road, and distance to the closest postal road in 1804. We use 1797 population figures drawn from Giustiniani (1797–1805, vols. I–X), which are available for 1,704 out of the 1,768 municipalities that belonged to the Kingdom of Naples at the time of the Napoleonic reforms and still existed as municipal administrative units in 1911. We also rely on Giustiniani (1797–1805, vols. I–X) to identify the proto-industrial nature of a municipality and construct a dummy variable that takes a value of one for municipalities characterized by first forms of manufacturing activity in 1797, and a value of zero otherwise. We capture the infrastructural dimension through two proxies: first, we consider the distance between a municipality and the closest ancient Roman road (McCormick et al. Reference McCormick, Huang, Zambotti and Lavash2013); second, we have digitized the network of postal roads existing in 1804 as depicted in the map Carta delle stazioni militari in Italia realized by the Ministry of War of the Napoleonic Republic of Italy, and consider the distance between a municipality and the closest postal road. We do not find a statistically significant correlation between economic and infrastructural characteristics and the probability of being selected as district capital in 1806; by contrast, we find a negative and statistically significant association between a municipality’s distance to its district’s centroid and the probability of being selected as the district capital in 1806 (Table C4, Online Appendix C).

As a second exercise, we focus on the Strada Regia delle Calabrie as a case study. In the second half of the eighteenth century, the road system in the Kingdom of Naples was in a state of significant disrepair, both in terms of long-distance routes and local connections between small towns. As a result, in 1778, King Ferdinand IV initiated the construction of the Strada Regia delle Calabrie, that is, a 280-mile rolling road designed to connect Naples with Reggio Calabria, the southernmost city in the Kingdom of Naples, via the provinces of Basilicata, Calabria Citeriore, and Calabria Ulteriore (Esposito Reference Esposito2021). This primary infrastructure may have influenced the selection of district capitals. Cities located closer to the Strada Regia delle Calabrie likely benefited from better integration into the Kingdom’s road network, resulting in greater accessibility. We empirically examine whether proximity to this infrastructure influenced the selection of district capitals in 1806 by comparing municipalities located within one day’s travel from this road to those situated between one and two days’ travel away. We rely on digital cartography provided by Esposito (Reference Esposito2021) and construct a dummy variable taking a value of one for municipalities located within one travel day—defined as the distance a horse was able to travel in one day, that is, 18.5185 km—from the closest point on the Strada Regia delle Calabrie, and a value of zero for municipalities located between one and two travel days.Footnote 25 We find no evidence that a greater proximity to the Strada Regia delle Calabrie has influenced a municipality’s probability of being selected as district capital in 1806 (Table C6, Online Appendix C). By contrast, we find a negative and statistically significant association between a municipality’s distance to its district’s centroid and the probability of being selected as the district capital in 1806. In other words, we demonstrate that spatial centrality, rather than road network accessibility, was the primary selection criterion adopted by Napoleonic authorities in 1806.

Historical evidence supporting the primacy of spatial centrality over accessibility in the selection of district capitals in 1806 is also evident in the numerous petitions submitted by Intendants and Sub-Intendants to the central institutions of the Kingdom of Naples between 1807 and 1818. The main objective of these petitions—none of them sent before January 1807—was to request a revision of the administrative geography established in 1806, advocating for less reliance on “crude geographical data” and instead considering the actual accessibility of district capitals (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990, p. 86, our translation). Indeed, the arrival of Intendants and Sub-Intendants facilitated the gathering of new information about the geographical characteristics and internal road networks of the territories under their governance (Spagnoletti Reference Spagnoletti1990).Footnote 26

In conclusion, all these analyses consistently lead to the same result: neither local elites nor economic and infrastructural conditions appear to have influenced the selection of district capitals in 1806. This finding confirms that district capitals were chosen for their spatial centrality within districts, supporting the exogeneity of the selection criterion.

EMPIRICAL FRAMEWORK

Population Data and Estimation Sample

We assess whether the municipalities selected as district capitals gained an urban development premium by relying primarily on population data collected from a variety of sources. First, we have digitized population data for the pre-Napoleonic period, drawing from Giustiniani (1797–1805, vols. I–X), who provides information on the number of households (the so-called fuochi) for the years 1648 and 1669 and on the number of inhabitants for the year 1797.Footnote 27 We have obtained population figures for the years 1648 and 1669 by multiplying the number of households by the factor five (e.g., Beloch Reference Beloch and Carlo1959; Da Molin Reference Molin1990; Fusco Reference Fusco2011; Sakellariou Reference Sakellariou2012). Second, we have digitized population figures provided by Marzolla (Reference Marzolla1832) for the year 1828 and drawn from the Censimento degli Antichi Stati Sardi, published in 1864 by the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Trade (MAIC), for the year 1859.Footnote 28 Finally, we have collected population figures for the period 1861–1911 from the population censuses—carried out every 10 years starting in 1861—provided by ISTAT. Overall, we have been able to collect population data covering the pre-Napoleonic years 1648, 1669, and 1797; the Bourbonic years 1828 and 1859; and the post-Italian unification years 1861, 1871, 1881, 1901, and 1911.Footnote 29

We have identified the estimation sample in order to compare municipalities selected as district capitals in 1806 (i.e., our treatment group) with municipalities without supra-municipal administrative functions (i.e., our control group). To this aim, we have considered the following criteria: first, we have excluded all municipalities that have been provincial capitals from the sixteenth century until 1911 even for a short period of time; second, we have excluded all municipalities that have been the seat of governo during the Napoleonic period, and/or circondario under the Bourbons, and/or mandamento in the Kingdom of Italy even for a short period of time; third, we have excluded all municipalities that have been district capitals only for a period of time between 1806 and 1911.Footnote 30 Therefore, we have identified as treated units only those municipalities that were selected as district capitals by Law No. 132 of 8 August 1806 and maintained their status uninterruptedly until 1911; by contrast, we have identified as control units those municipalities that have never been selected as capital cities at any geographical-administrative level and, thus, have never been endowed with supra-municipal administrative functions by law over the entire period considered. The rationale behind these criteria for selecting the estimation sample is to compare only those municipalities that became district capitals as a result of the 1806 reform and maintained this status uninterruptedly during the period 1806–1911 with those that never received supra-municipal administrative functions during the same period, provided that both groups of municipalities were not capital cities and did not have supra-municipal functions prior to the 1806 reform.Footnote 31 Finally, we have excluded all municipalities for which we have not been able to reconstruct population figures for the entire period of 1648–1911.Footnote 32

Considering the aforementioned criteria and the availability of population data, our estimation sample includes 15 treated and 959 control municipalities, which are mapped in Figure 3.Footnote 33

Figure 3 MUNICIPALITIES INCLUDED IN THE ESTIMATION SAMPLE

Notes: The map shows the treated (cross) and control (circle) municipalities included in the estimation sample.

Source: Elaboration on digitized cartography provided by GEO-LARHRA and ISTAT.

Empirical Method

We evaluate whether district capitals gained an urban development premium compared with non-capital municipalities through the following difference-in-differences (DID) specification:

where Populationmdpt denotes the population (in thousand inhabitants) of municipality m located in district d within province p in year t; District Capitalmdpt denotes the treatment dummy variable, which takes a value of zero for the control municipalities over the entire observation period 1648–1911 and for the treated municipalities in the pre-Napoleonic observation years 1648, 1669, and 1797, while a value of one for the treated municipalities over the observation period 1828–1911; γm and δt capture municipality and year fixed effects (FE), respectively; ![]() denotes the yearly-specific distance between a municipality and the own provincial capital city to control for proximity to the seat of the reference Intendancy/Prefecture; Xmdp is a vector of geographical and historical municipality-level controls interacted with year FEs (δt); Xpt is a vector of province-level controls; µd denotes a time trend at the Bourbonic district level (defined as for districts in 1828); vd denotes a time trend at the Kingdom of Italy district level; and εmdpt is the error term.Footnote 34

denotes the yearly-specific distance between a municipality and the own provincial capital city to control for proximity to the seat of the reference Intendancy/Prefecture; Xmdp is a vector of geographical and historical municipality-level controls interacted with year FEs (δt); Xpt is a vector of province-level controls; µd denotes a time trend at the Bourbonic district level (defined as for districts in 1828); vd denotes a time trend at the Kingdom of Italy district level; and εmdpt is the error term.Footnote 34

The vector Xmdp of time-invariant municipality-level controls includes both geographical and historical (pre-1806) variables that enter Equation (1) interacted with year dummies. The set of geographical controls includes: a within-district centrality measure defined as the average pairwise distance among the municipalities belonging to a district in the year 1806 to control for a municipality’s geographical centrality within a district, being “spatial centrality” the criterion adopted by the Napoleonic authorities to select district capitals; a dummy variable for coastal municipalities; land surface; altitude; latitude; and an index of terrain ruggedness.Footnote 35 The set of historical controls includes: a dummy variable for state-owned (i.e., non-feudal) municipalities in 1797 to control for heterogeneity related to fiscal, commercial, and administrative prerogatives granted to such cities by the King (Borghi and Masciandaro Reference Borghi and Masciandaro2023); two dummy variables for municipalities that were the seat of a bishop or an archbishop in 1797, respectively, to control for the presence of first forms of political and institutional organization and coordination (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2016); a dummy variable for princedom municipalities in 1797 to control for the strength of the aristocracy (Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales Reference Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales2016); a dummy variable for municipalities hit by the plague in 1658 to control for heterogeneity related to an exogenous shock that could have affected city size (Fusco Reference Fusco2007); a dummy variable capturing whether a municipality recorded a population of at least 5,000 inhabitants in the period 1300–1500 to control for the early presence of a large city (Bosker, Buringh, and van Zanden 2013); a variable capturing the distance between a municipality and the closest ancient Roman road to control for proximity to ancient commercial routes that could have favored the growth of a city as a main trading, political, and administrative center (Oto-Peralías and Romero-Ávila Reference Oto-Peralías and Romero-Ávila2017); and a variable capturing municipalities’ exposure to earthquakes in the period 1005–1805 to control for systematic environmental risks that could not only have caused exogenous variations in city size but also increased the power and political strength of religious orders (Belloc, Drago, and Galbiati Reference Belloc, Drago and Galbiati2016).Footnote 36 The vector Xpt of province-level controls includes two time-varying variables: the share of a province’s population to the total population of the Kingdom of Naples to control for the relative size of provinces, and the density of the provincial railway network to control for the development of transport and communication infrastructures.Footnote 37

Although the inclusion of municipality FEs captures any time-invariant characteristics, such as geographical and pre-treatment (historical) features, controlling for their potential time-varying effects helps us relax potential biases related to unobserved heterogeneity and omitted variables (Bo Reference Bo2020). Moreover, the inclusion of Bourbonic and Kingdom of Italy district-specific time trends allows us to control for development paths that were specific to the districts to which the municipalities belong and that could have influenced their population dynamics. In addition, accounting for district-specific time trends helps us reduce any potential correlation existing between omitted variables and the expansion or rearrangement of borders that some of the districts included in the analysis have experienced over the observation period (Campante and Do Reference Campante and Do2014).

Identification Strategy

Despite Equation (1) including a large number of FEs and controls, our estimates could still be biased by unobservable factors that are not accounted for and that can be correlated simultaneously with the timing and the outcome of the 1806 reform, for example, a higher population growth potential that characterized district capitals compared with non-capital cities before 1806. Indeed, the reliability of our estimates relies on a standard parallel trend assumption, which requires the treated and control units to experience the same pattern in the outcome variable, conditional on observables, in the absence of the shocking event. In our case, the identification assumption requires that municipalities in the treatment and control groups would have experienced the same population dynamics if the Napoleonic authorities had not instituted the districts and selected—and, thus, attributed supra-municipal functions to—district capitals in 1806.

We test whether differential trends existed before the implementation of the 1806 reform by relying on a more flexible specification of Equation (1) that accounts for a set of yearly treatment effects. This allows us to test for the direction of causality by checking for anticipatory effects in the period before the implementation of the Napoleonic reform. Moreover, such a flexible specification allows us to assess the time-varying effects of the reform on urban development over the entire post-reform period. We modify Equation (1) according to an event study approach as follows:

which includes a set of lead dummy variables (![]() ) referring to the available pre-1806 observation years h = 1648, 1669, 1797, with ω denoting the implementation year of the reform, and a set of lag dummy variables (

) referring to the available pre-1806 observation years h = 1648, 1669, 1797, with ω denoting the implementation year of the reform, and a set of lag dummy variables (![]() ) referring to each post-1806 available observation year l starting from 1828. Therefore, we expect πω–h = 0 for all h if the parallel trend assumption holds prior to the implementation of the reform in 1806. We estimate Equation (2) by specifying the lead dummy variable referring to the year 1797 as the reference category.

) referring to each post-1806 available observation year l starting from 1828. Therefore, we expect πω–h = 0 for all h if the parallel trend assumption holds prior to the implementation of the reform in 1806. We estimate Equation (2) by specifying the lead dummy variable referring to the year 1797 as the reference category.

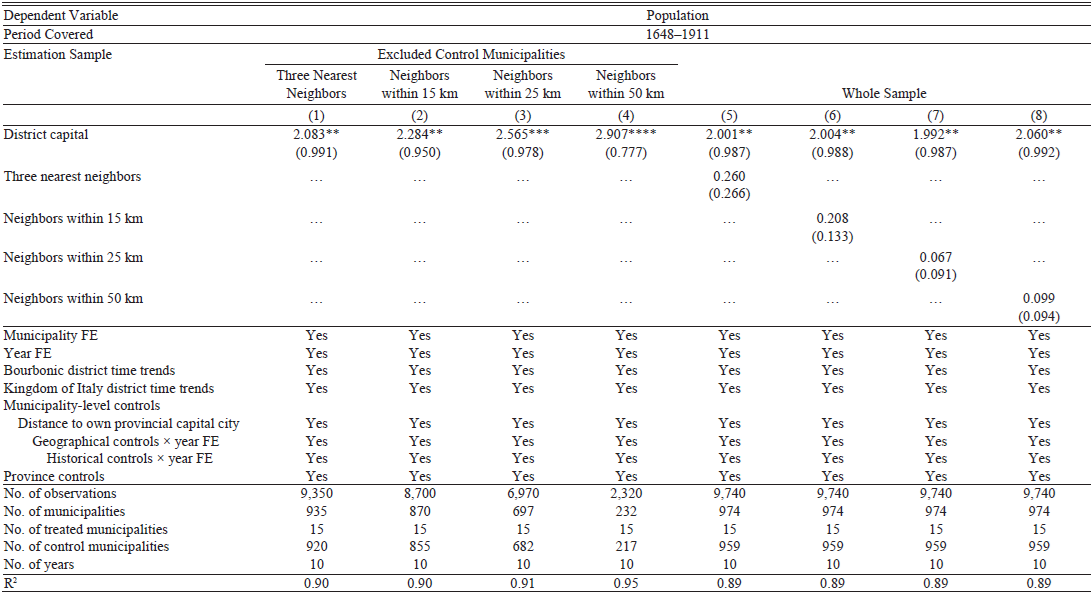

A second requirement of our identification strategy concerns the absence of spillover effects between the treated and control municipalities. Indeed, Equation (1) allows us to assess whether the Napoleonic reform has induced an urban development premium for district capitals compared with non-capital municipalities under the assumption that the reform had neutral effects on the latter type of municipality. However, such an urban development premium could be the result of a mere reallocation effect if the reform simply acted as a “pushing force,” inducing a migration of people from neighboring non-capital cities toward the district capital. In other words, evidence of spatial spillovers between a treated municipality and the neighboring control municipalities would imply a reallocation effect rather than an urban development effect of the reform (Bo Reference Bo2020). We test whether spatial spillovers are in place in two ways. First, we estimate Equation (1) by excluding either the three neighboring control municipalities closest to a district capital, or the neighboring municipalities located within distance φ from a district capital, with φ = 15, 25, 50 km, from the estimation sample. Second, we modify Equation (1) as follows:

where Neighborsmdpt denotes a binary variable referring to either the three neighboring control municipalities closest to a district capital, or those located within distance φ from a district capital. This alternative specification also allows us to assess whether the 1806 reform had indeed neutral effects on district capitals’ neighboring municipalities. The parameter ρ captures the spillover effect, such that we expect no spatial spillovers to be in place if ρ = 0.

EMPIRICAL RESULTS ON URBAN DEVELOPMENT

Baseline Results and Identification

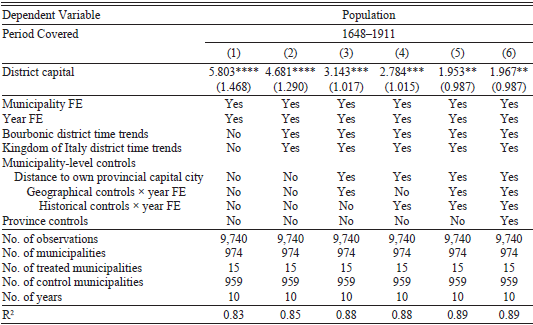

Table 1 reports the results of the estimation of Equation (1) with FEs, district time trends, and control variables included in the empirical specification according to a stepwise procedure. Looking at Column (6), we estimate an average urban development premium of approximately 2,000 inhabitants for district capitals compared with non-capital cities. This premium corresponds to a 92.43 percent population increase, given a sample average population of approximately 2,128 inhabitants.

Table 1 POPULATION EFFECTS OF DISTRICT CAPITAL CITY STATUS

Notes: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.001. The dependent variable is defined in thousands of inhabitants. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered at the municipality level.

Source: See text.

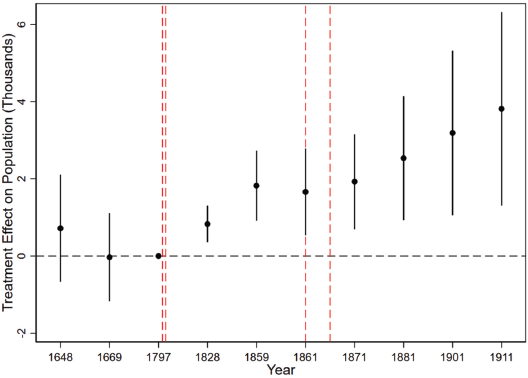

Figure 4 reports the results of the estimation of Equation (2). On the one hand, the coefficients referring to the pre-Napoleonic reform period are not statistically significant, and the 1669 coefficient is virtually equal to zero.Footnote 38 This result suggests that the parallel trend assumption holds, such that we can construe the results reported in Table 1 consistently with a causal interpretation. On the other hand, we find evidence of post-Napoleonic reform population dynamics that is consistent with the historical narrative previously presented. First, Figure 4 highlights a higher urban development premium for district capitals compared with non-capital cities after the approval of the Lanza Law in 1865, which assigned more functions and powers to the Sub-Prefect, thus increasing the relative importance of district capitals in the territorial administrative hierarchy of the Kingdom of Italy. Second, the annexation of the former Kingdom of Naples to the Kingdom of Italy, which occurred in 1861, caused a slowdown in urban development dynamics of district capitals. This is possibly due to a climate of institutional uncertainty that emerged during the unification process, as well as the increased phenomenon of brigandage and armed opposition from Bourbon officials that occurred in the first decade after unification (Pinto Reference Pinto2019).Footnote 39

Figure 4 POPULATION EFFECTS OF DISTRICT CAPITAL CITY STATUS: EVENT STUDY ANALYSIS

Notes: The dependent variable is population, defined in thousands of inhabitants. The model includes FEs, time trends, and controls as in Column (6) of Table 1. The pre-1806 Napoleonic administrative reform year 1797 is set as the reference period. Confidence intervals for lead and lag dummy variable coefficients are set at 90 percent. The vertical dashed lines refer to: the 1806 Napoleonic administrative reform; the 1816 restoration of the Bourbons; the 1861 Italian unification; and the 1865 Lanza Law.

Source: See text.

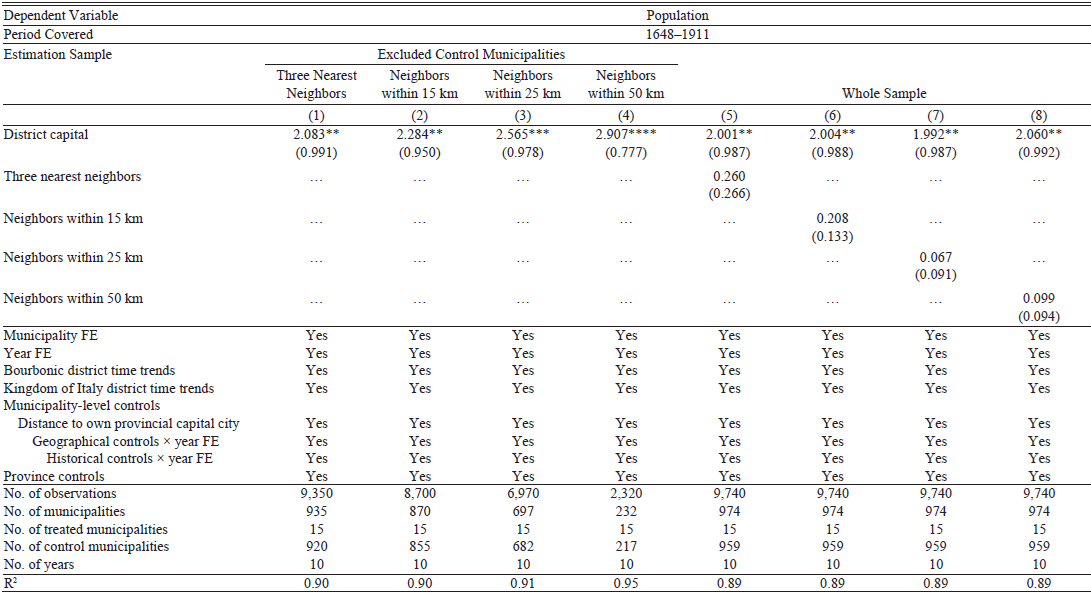

Table 2 reports the results concerning the potential existence of spillover effects between the treated and control municipalities. We do not find evidence of such effects and, in particular, the variables for neighboring control municipalities show negligible estimated coefficients. Moreover, the results confirm our main evidence of an average urban development premium of approximately 2,000 inhabitants for district capitals compared with non-capital cities. In other words, we find evidence that the 1806 Napoleonic reform had a growth effect for district capitals, rather than a mere reallocation effect between the treated and the neighboring control municipalities.Footnote 40

Table 2 POPULATION EFFECTS OF DISTRICT CAPITAL CITY STATUS: TESTING FOR SPILLOVER EFFECTS

Notes: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.001. The dependent variable is defined in thousands of inhabitants. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered at the municipality level.

Source: See text.

Robustness and Placebo Analyses

We corroborate our results through a series of robustness and placebo exercises, as well as by providing more suggestive evidence to disentangle the population effects of being a district capital city from those (potentially) related to the geographical centrality of district capitals. We discuss these exercises in detail and present the results in Online Appendix F.Footnote 41

EVIDENCE ON INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT

We now move to the analysis of industrial development in the late Bourbonic period and in the Kingdom of Italy period.

We analyze the Bourbonic period by looking at “industrial cities” in the 1850s, that is, municipalities identified by both Petrocchi (Reference Petrocchi1955) and Mangone (Reference Mangone1976) as centers of production activity in the period 1850–1860. We proxy for industrial development in the Kingdom of Italy period through employment in 1911 (relative to municipal population in 1911), with data on total, industrial, and services employment digitized from the Censimento degli Opifici e delle Imprese Industriali al 10 Giugno 1911 published by MAIC in 1913. We rely on a cross-sectional regression framework and estimate the following general-form equation:

where Ymdpc denotes the dependent variable for industrial development in municipality m located in district d within province p and compartimento c—that is, a geographical macro-region instituted in 1861 for statistical purposes; thus, the dependent variable can be either the dummy for “industrial city” in the period 1850–1860 or the number of (total, industrial, services) employees per inhabitant in 1911. The variable District Capitalmdpc denotes the treatment assignment, as before. The vector Xmdpc consists of municipality-level control variables and—depending on the output variable and, thus, period-specific data availability—includes: population density and population growth with respect to the pre-Napoleonic reform year 1797 to control for city size and growth dynamics; coastal feature; land surface; altitude; terrain ruggedness; latitude; and distance to the own provincial capital city to control for proximity to the seat of the Intendancy/Prefecture of reference. The vector Xpc consists of province-level control variables and—depending on the output variable and, thus, period-specific data availability—includes: the share of a province’s population to the total population in the Kingdom of Naples’ territory to control for the relative size of a province; the density of the railway network to control for the development of transportation and communication infrastructures; and the rate of literate adult population to control for human capital development. The term ζc denotes a set of compartimento dummies defined for the year 1871 and included only in the regression models for industrial development in 1911.Footnote 42 Finally, εmdpc is the error term.Footnote 43

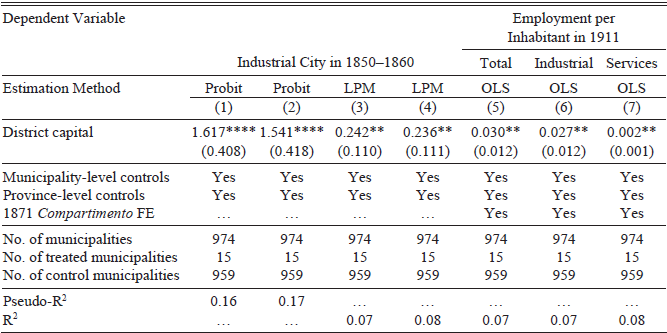

We estimate Equation (4), depending on the nature of the dependent variable, using Probit, Linear Probability Model (LPM), and Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). The results, reported in Table 3, suggest an industrial development premium of district capitals over non-capital cities both before and after the Italian unification. Looking at the Bourbonic period, we estimate that district capitals were approximately 24 percent more likely to be industrial cities than non-capital cities—see Columns (3) and (4). This suggests that the 1806 reform induced a (long-lasting) process of economic divergence between district capitals and non-capital cities, thus facilitating heterogeneity in the industrial development path of the Italian Mezzogiorno. We confirm this evidence when looking at the post-1865 Lanza Law period: we find that district capitals had approximately 30 employees per 1,000 inhabitants more than non-capital cities, and that this result is driven by industrial rather than services employment.Footnote 44

Table 3 INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT

Notes: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.001. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered at the municipality level. Municipality-level controls in all specifications include coastal feature, land surface, altitude, terrain ruggedness, and latitude. Estimates on industrial development in 1850–1860: the set of municipality-level controls includes population density in 1828, population growth in 1797–1828, and distance to the provincial capital city in 1828; the set of province-level controls in Columns (1) and (3) includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1828; the set of province-level controls in Columns (2) and (4) includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1828 and provincial railway density in 1859. Estimates on employment per inhabitant in 1911: the set of municipality-level controls includes population density in 1911, population growth in 1797–1911, and distance to the provincial capital city in 1911; the set of province-level controls includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1911, provincial railway density in 1911, and provincial literacy rate in 1911.

Source: See text.

Overall, this analysis confirms the previous results on urban development: district capitals experienced a higher development path—still observable about a century after the 1806 reform—relative to non-capital municipalities.Footnote 45

UNDERLYING MECHANISMS

We now discuss and test two potential mechanisms that may help explain the relationship between administrative hierarchy and development. The first mechanism concerns the provision of public goods (Campante and Do Reference Campante and Do2014; Becker, Heblich, and Sturm Reference Becker, Heblich and Sturm2021; Chambru, Henry, and Marx Reference Chambru, Henry and Marx2024). District capitals experienced the arrival of civil servants, officials, policemen, and soldiers, and this may have reasonably induced an increase in the demand for local public goods (e.g., schools, infrastructures) with positive externalities benefiting the local population and translating into greater industrial development. The second mechanism concerns transport network accessibility. The geographical-administrative organization envisaged by the Napoleonic reform was based on a multi-level transmission system of legal, administrative, and political information in which district capitals acted as key “nodes” of connection between the provincial capital of reference and the peripheral municipalities. Therefore, it was essential for district capitals to be connected to the transport network. We can reasonably hypothesize that greater accessibility has contributed to urban development in general, and to the development of production activities in particular, thus facilitating the industrialization process in district capitals.

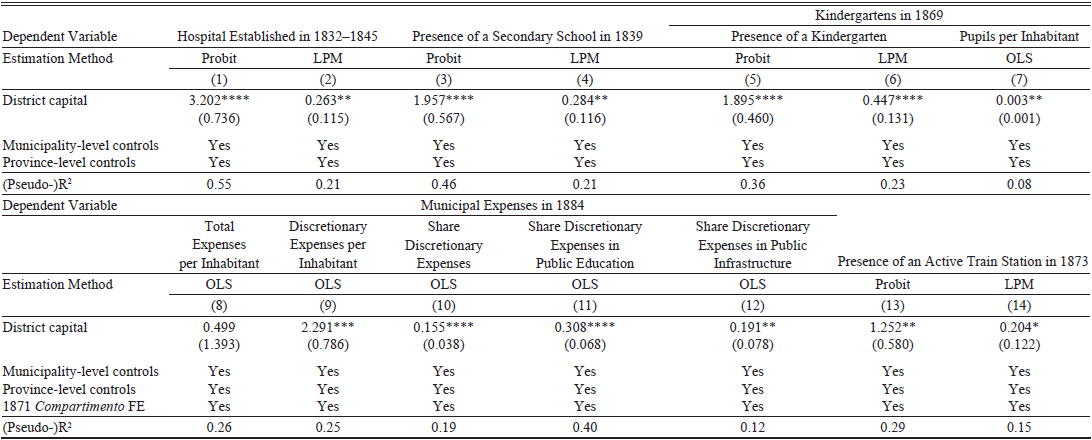

We capture public goods provision during the Bourbonic period through two variables: first, the establishment of a hospital in the period 1832–1845, with data drawn from the Annali Civili del Regno delle Due Sicilie published in 1857 by the Ministry of the Interior of the Kingdom of Naples; second, the presence of a secondary school in 1839, with data drawn from Serristori (Reference Serristori1839).Footnote 46

We capture public goods provision in the post-unification period through two main sets of variables concerning kindergartens in 1869 and municipal expenses in 1884. The rationale for this relies on the distinction between compulsory and discretionary expenses provided by Title II of the 1859 Rattazzi Law, which was later implemented in the annexed territories of the Italian Mezzogiorno with the approval of the 1865 Lanza Law that slightly increased the number of municipal compulsory expenses (Articles 115 to 117).Footnote 47 We consider discretionary expenses as a proxy for a municipality’s attention to local community needs and, thus, for public goods provision. First, we rely on information about the presence of a kindergarten—that was listed among municipalities’ discretionary expenses—in 1869 and the number of pupils enrolled (relative to municipal population in 1861), with data digitized from the Statistica del Regno d’Italia: Gli Asili Infantili nel 1869, published by the Italian Directorate General of Statistics in 1870. Second, we rely on balance sheet data digitized from the Bilanci Comunali per l’Anno 1884, published by MAIC in 1887. This source provides information on total revenues, while more disaggregated information on the expenditure side, namely compulsory and discretionary expenses, is aggregated with respect to three main categories: public education, public infrastructures, and other expenses. We construct different dependent variables: total (compulsory plus discretionary) expenses per inhabitant; discretionary expenses per inhabitant; share of discretionary expenses to total expenses; share of discretionary expenses to total expenses in public education; and share of discretionary expenses to total expenses in public infrastructures.Footnote 48

Concerning the second mechanism, we proxy for transport network accessibility through train station endowment in 1873. We have digitized information on active train stations existing in 1873 drawn from the third edition of the Dizionario dei Comuni del Regno d’Italia, published by the Italian Ministry of the Interior in 1874. We thus consider a binary dependent variable taking a value of one if a municipality was endowed with a train station in 1873, and a value of zero otherwise.Footnote 49

We rely on a cross-sectional regression framework similar to that of Equation (4) and on Probit, LPM, and OLS estimation approaches.Footnote 50

We start presenting the results concerning public goods provision. First, the LPM estimates on the establishment of a hospital in the period 1832–1845 suggest that district capitals were approximately 26 percent more likely to be endowed with a hospital than non-capital cities—see Column (2) of Table 4. Second, as shown in Column (4), we find that district capitals were approximately 28 percent more likely to be endowed with a secondary school than non-capital cities. Third, the LPM results on kindergartens in 1869 suggest that district capitals were approximately 55 percent more likely to provide the local population with a kindergarten. Moreover, district capitals had approximately 3 pupils enrolled in kindergartens per 1,000 inhabitants more than municipalities in the control group. Fourth, the results on 1884 municipal expenses suggest that district capitals tended to spend more on discretionary expenses compared with non-capital cities. We do not find evidence of statistically significant differences in total expenses per inhabitant, although we estimate a premium for district capitals when considering discretionary expenses per inhabitant. This last result is confirmed when proxying public goods provision through the share of discretionary expenses relative to total expenses, as well as when separating public education and public infrastructure expenses.

Table 4 UNDERLYING MECHANISMS

Notes: * p < 0.1; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01; **** p < 0.001. Estimates are based on 974 (15 treated and 959 control) municipalities. Standard errors (in parentheses) are clustered at the municipality level. Municipality-level controls in all specifications include coastal feature, land surface, altitude, terrain ruggedness, and latitude. Estimates on hospitals established in the period 1832–1845 and secondary schools in 1839: the set of municipality-level controls includes population density in 1828, population growth in 1797–1828, distance to the provincial capital city in 1828; the set of province-level controls includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1828. Estimates on kindergartens in 1869: the set of municipality-level controls includes population density in 1861, population growth in 1797–1861, and distance to the provincial capital city in 1861; the set of province-level controls includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1861, provincial railway density in 1861, provincial literacy rate in 1861, and provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples public primary schools in 1862. Estimates on municipal expenses in 1884: the set of municipality-level controls includes population density in 1881, population growth in 1797–1881, distance to the provincial capital city in 1881, and total expenses to revenues in 1884; the set of province-level controls includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1881, provincial railway density in 1881, and provincial literacy rate in 1881. Estimates on train stations in 1873: the set of municipality-level controls includes population density in 1871, population growth in 1797–1871, and distance to the provincial capital city in 1871; the set of province-level controls includes provincial-to-Kingdom of Naples population in 1871, provincial railway density in 1871, and provincial literacy rate in 1871.

Source: See text.

Columns (13) and (14) in Table 4 report the results concerning transport network accessibility. Looking at Column (14), we estimate that district capitals, at a time when the construction of the railway network was still underway, were approximately 20 percent more likely to be equipped with a train station.Footnote 51

Overall, these results suggest that district capitals tended to provide more public goods to the local population and enjoy greater connectivity compared with non-capital cities, thus making them suitable for higher urban and industrial development.

LONG-RUN ANALYSIS

We conclude our analysis by providing more suggestive evidence on the long-term effect of the Napoleonic administrative reform on the development and economic geography of the Italian Mezzogiorno. Specifically, we analyze whether there is still a gap between (former) district capitals and non-capital municipalities approximately 90 years after the abolition of the administrative unit of the district, which occurred in 1927 under the Fascist regime.Footnote 52

The results, based on a battery of current outcome variables (e.g., urban development, human capital endowment, income, labor productivity), suggest that former district capitals still show a premium compared with non-capital municipalities, even decades after the abolition of the district administrative unit and, therefore, after losing their status.Footnote 53

This evidence suggests that the Napoleonic reform represented a structural change in the urban and economic geography of southern Italy. In other words, the administrative reform process experienced by continental southern Italy in the early nineteenth century contributed to a process of long-run territorial divergence, resulting in heterogeneous development paths within the Italian Mezzogiorno.

CONCLUSIONS

We analyzed the 1806 Napoleonic administrative reform implemented in the Kingdom of Naples as a historical experiment to study how exogenous changes in the territorial administrative hierarchy of a country may have long-term consequences for urban and industrial development. In this respect, we contribute to the literature studying state capacity building and its role in influencing development and economic geography. Our results reveal that municipalities selected as district capitals enjoyed higher and enduring urban and industrial development compared with municipalities that did not experience a status change in the country’s geographical-administrative hierarchy and did not become “centers of power” at the local level.

Our evidence suggests how political and administrative hierarchies can shape the process of urban growth and local development. In other words, we identified in these radical reforms a historical explanation for the processes of urbanization and local development that occurred in southern Italy and a source of growth differentials within the Italian Mezzogiorno.