In cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), planning starts by writing a goal on a piece of paper and committing to trying to achieve it. The choice of what to do first is influenced by a range of complex factors. For example, the patient's and practitioner's understanding of the problems, strategies they have used before, personal strengths and weaknesses, and the resources available to them, such as other people or having the stability of a job and income. A decision needs to be made about what is most achievable, as well as identifying potential problems that may derail the plan.

However a clinician decides to help their patient make plans, the most important factor in making it effective is that it is made collaboratively. The goal needs to actively involve the patient, and not be defined by the clinician alone. With this in mind, we have outlined a handy three-step approach – Plan, Do and Review – with the first step, Plan, integrating this spirit of collaboration (Reference Williams and ChellingsworthWilliams 2010).

Step 1: Make a plan

It's important to start with small goals based on something that's important to the patient. Discussion could cover the top four or five things they would like to change. Of these, select one that you both think is achievable and relevant to the patient's problems. To inform that choice consider a target that is big enough to move things forward, but small enough that it doesn't seem impossible or too anxiety-provoking.

Larger or general goals can be broken down into constituent parts, steps or chunks; select one of those parts to start things off. It is helpful to make the goal specific and measurable, so that you and your patient know how far they've come towards achieving it.

Write down the plan. A good first plan might involve a small behavioural change. Examples include doing something that they rate highly for enjoyment, or that develops a sense of closeness to others or that gives a feeling of achievement (or all three at the same time). Ideally, what they choose should also fit their values and how they would like to live their life. Early successes make it more likely that your patient will feel good and stay motivated, so encourage them to choose something that will make a positive difference.

The plan should identify:

-

what they will do

-

when they will do it

-

any potential blocks or difficulties that may arise.

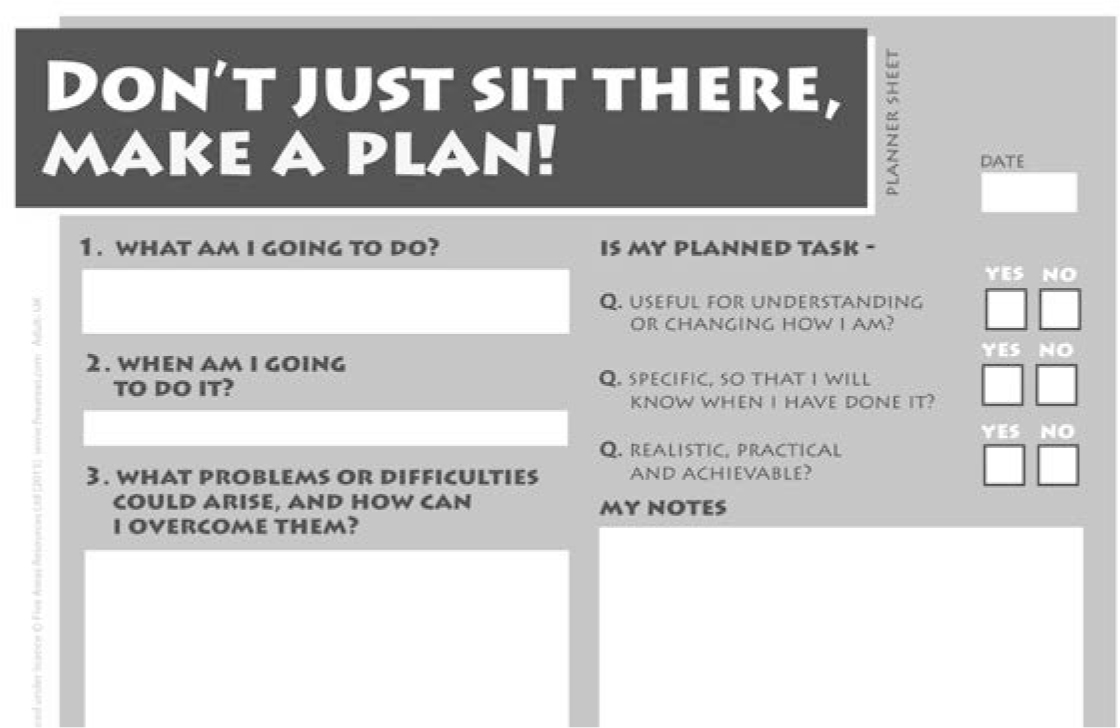

This allows a problem-solving stance to be taken even before the plan is put into action. For example, how could the patient modify things to adapt their plan if it rained that day, or their child was ill? A planner sheet (Fig. 1) aids writing a specific goal.

FIG 1 Planner sheet (© 2015 Five Areas Ltd, available free from www.llttf.com and reproduced with permission).

Step 2: Do

Here, the patient either does or doesn't do what was planned. Whatever happens, they can learn from it by completing a review.

Step 3: Review

Whether completed successfully or not, there is the opportunity to learn and to bring this learning into the structure of future plans.

Once the patient has tried their plan, make sure they write down what they did, when they did it and how it went. If it was a success, then the review process will be more concerned with whether to build on the progress to date or move to a completely new area.

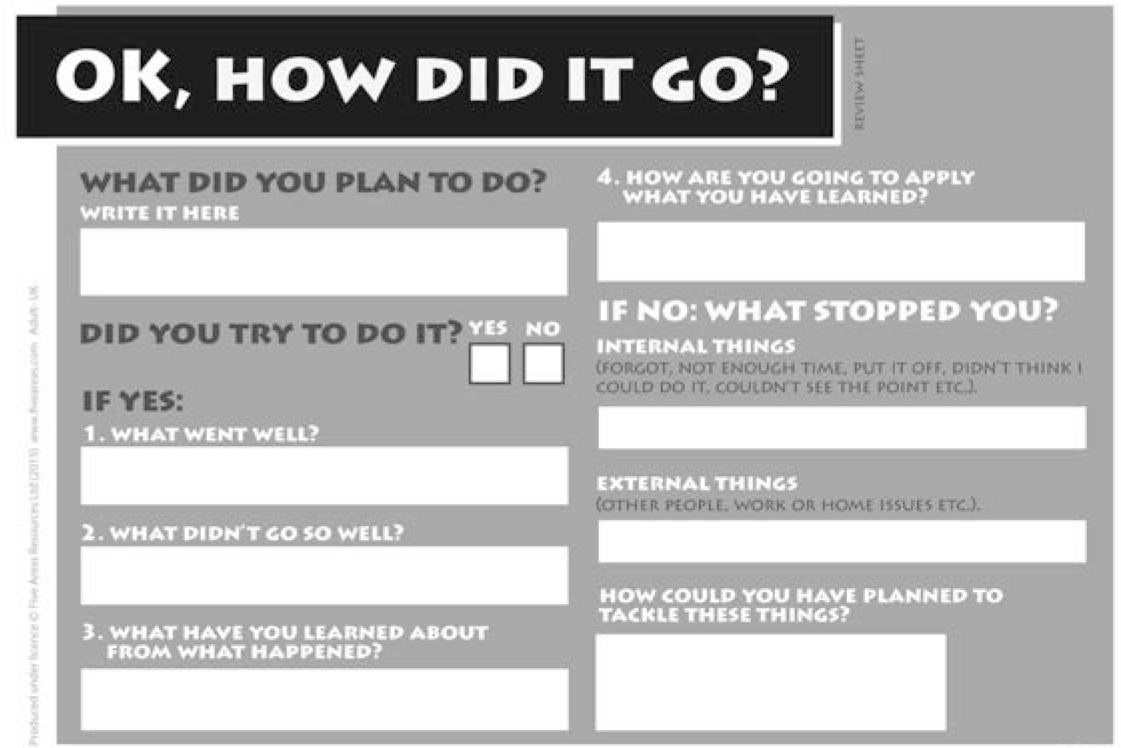

Failing to complete a plan can provide important insights into avoidance, thoughts and actions that create and confirm failure (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams 2002a), or giving in to the wishes of others and more. This is where the review stage becomes particularly useful in understanding exactly what happened (e.g. they forgot to do it, talked themselves out of it, or perhaps an unexpected external event occurred that made it hard to stick to the plan). Asking what they think went well first, followed by a joint discussion about what could have been done better, provides a constructive and structured approach to feedback. This aspect is worth slowing down, as significant learning can occur that can be applied to the next plan. Linking progress back to the initial CBT formulation (Reference Williams and GarlandWilliams 2002b; Reference Colvin and WilliamsColvin 2015) helps see progress in the light of the wider treatment plan. A review sheet (Fig. 2) promotes learning.

FIG 2 Review sheet (© 2015 Five Areas Ltd, available free from www.llttf.com and reproduced with permission).

You can find free copies of the planner and review worksheets at the Living Life to the Full website (www.Llttf.com).

Monitoring progress and moving forward

Rating scales can help monitor progress. Short-, medium- and long-term goals can then be used to plan a sequence of plans that aim to move the person towards their long-term goal.

Acknowledgements

The Plan, Do, Review model is used with permission of Five Areas Ltd.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.