Impact statement

The use of plastic in food packaging continues to contribute to the growing plastic pollution crisis. Plastic materials commonly used for food packaging (polyethylene, polypropylene, polystyrene) are difficult to recycle, often ending up in landfills and ecosystems. Plastic pollution has generated interest in alternatives to recycling food packaging, such as reusing food packaging or encouraging consumers to bring in their own packaging for shopping. One of the most commonly implemented systems to incentivize consumers to return packaging and to avoid accumulation in the environment are deposit return systems (DRS). Consumers pay a deposit upon purchase of a product, which is returned upon return of the packaging. This approach could significantly impact society and help address the growing plastic pollution crisis by promoting sustainable food packaging practices. However, DRS are frequently implemented to ensure effective collection of used packaging for the purpose of recycling, not the re-use of packaging. In this article we illustrate how lessons from key areas of concern in the implementation of DRS could be applied to truly circular packaging reuse systems. For this purpose, we present two case studies. One case shows how environmentally conscious consumers are encouraged to reuse their own packaging by fostering community engagement and volunteering. The other case shows how a DRS can be implemented using well-established multi-use food containers. Together, the two cases illustrate innovative solutions to help minimize the need for new plastic production and reducing the overall environmental footprint of food packaging, beyond the most frequently implemented solution of DRS for single-use plastic packaging.

Introduction

Plastic pollution is a major environmental problem, contributing an estimated 19–23 million metric tons of waste annually to oceans and aquatic ecosystems (Borrelle et al., Reference Borrelle, Ringma, Law, Monnahan, Lebreton, McGivern, Murphy, Jambeck, Leonard, Hilleary, Eriksen, Possingham, De Frond, Gerber, Polidoro, Tahir, Bernard, Mallos, Barnes and Rochman2020). Because of the complex material composition, plastic waste is difficult to recycle (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Awasthi, Wei, Tan and Li2021) and subsequently often mismanaged, meaning it most frequently ends up in landfills or the environment (about 60% of all plastics produced; Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Jambeck and Law2017). Of special concern are single-use plastics (i.e., plastic products that are disposed of after a single use), which are frequently used for packaging (Geyer et al., Reference Geyer, Jambeck and Law2017; Geyer, Reference Geyer2020; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Awasthi, Wei, Tan and Li2021). Due to their short life cycle, plastic packaging used for food products is especially problematic and they are among the most frequently found items in the environment (Morales-Caselles et al., Reference Morales-Caselles, Viejo, Martí, González-Fernández, Pragnell-Raasch, González-Gordillo, Montero, Arroyo, Hanke, Salvo, Basurko, Mallos, Lebreton, Echevarría, van Emmerik, Duarte, Gálvez, van Sebille, Galgani and Cózar2021; Baxter et al., Reference Baxter, Lucas and Walker2022; González-Fernández et al., Reference González-Fernández, Cózar, Hanke, Viejo, Morales-Caselles, Bakiu, Barceló, Bessa, Bruge, Cabrera, Castro-Jiménez, Constant, Crosti, Galletti, Kideys, Machitadze, de Brito, Pogojeva, Ratola and Tourgeli2022; Cowger et al., Reference Cowger, Willis, Bullock, Conlon, Emmanuel, Erdle and Wang2024).

A promising solution to reduce plastic waste from the environment is packaging reuse systems. We define those as systems incentivizing consumers (i) to reuse their own packaging and bring it in for grocery shopping (e.g., in zero-waste stores; Watson and Smith, Reference Watson and Smith2020), or (ii) to return multi-use packaging by charging a deposit upon purchase (e.g., Rhein and Sträter, Reference Rhein and Sträter2021). These systems are understudied, especially in relation to multi-use packaging for solid and semi-solid food products. Deposit return systems (DRS) for beverage containers (either single- or multi-use) are well studied in scientific literature, and offer lessons for the implementation of packaging reuse systems for other food products (e.g., Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gu, Wu, Gong, Mu, Han and Chang2020; Calabrese et al., Reference Calabrese, Costa, Levialdi Ghiron, Menichini, Miscoli and Tiburzi2021).

If designed effectively, DRS can result in return rates of more than 80%, as reported for systems implemented for beverage containers in European countries (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gu, Wu, Gong, Mu, Han and Chang2020; Görgün et al., Reference Görgün, Adsal, Misir, Aydin, Ergün, Keskin, Acar and Ergenekon2021). Therefore, they are efficient in keeping used packaging out of the environment (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gu, Wu, Gong, Mu, Han and Chang2020; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Tomić and Raal2021). However, most DRS primarily aim to increase collection rates of packaging (single-use DRS), but do not necessarily address the challenge of recycling single-use packaging, meaning that collected packaging is downcycled or disposed of (Rhein and Sträter, Reference Rhein and Sträter2021; Loy et al., Reference Loy, Lim, How, Yiin, Lock, Lim, Alhamzi and Yoo2023; Singh and Walker, Reference Singh and Walker2024; Walker, Reference Walker2025). Conversely, multi-use DRS require companies to implement more sustainable business practices to re-fill packaging with products and distribute them for consumer purchase (multi-use DRS; Calabrese et al., Reference Calabrese, Costa, Levialdi Ghiron, Menichini, Miscoli and Tiburzi2021). DRS are managed in different ways, for example, as part of extended producer responsibility schemes, by governmental institutions, or by delegation to specifically created organizations. Funding of DRS consequently varies and includes, for example, administrative fees for participating companies, using the deposit fee of unreturned packaging, and selling containers for their post-consumer value (in the case of single-use DRS (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gu, Wu, Gong, Mu, Han and Chang2020).

Based on literature relating to DRS of beverage packaging, different areas of concern can be identified that are relevant to exploring the applicability of packaging reuse systems for solid and semi-solid food products. Hygiene is a key issue when reusing packaging. Costs for producers and retailers arise, for example, to sanitize used packaging or to subcontract third-party companies responsible for the hygiene of containers (Picuno et al., Reference Picuno, Gerassimidou, You, Martin and Iacovidou2025). Further, the maintenance and cleaning of secondary packaging (such as crates and pallets), and dispensers of bulk food incur costs (Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster and Worrell2020; Theobald et al., Reference Theobald, Mich, Hillesheim, Hartard and Rohn2024). For consumers, aspects of hygiene can create real or perceived health concerns that could cause them to prefer products with single-use packaging (Blumhardt, Reference Blumhardt2023). It is, therefore, pertinent that companies make it apparent through their packaging and marketing that their containers meet appropriate health and safety standards (Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster and Worrell2020).

Another key concern is transport and logistics. While the flow for single-use packaging is unidirectional, multi-use DRS involve frequent transport processes of full and empty containers between different actors (e.g., producers, retailers, storage and cleaning facilities and consumers (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gu, Wu, Gong, Mu, Han and Chang2020). The implementation of single- and multi-use DRS requires producers and retailers to restructure their supply chain organization (Blumhardt, Reference Blumhardt2023). This entails considerable upfront costs for new infrastructure and retail settings (Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster and Worrell2020; Blumhardt, Reference Blumhardt2023), for example, for the installation of reverse vending machines and allocating store space to DRS, which, in turn, is not available as sales area (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Hasselström, Finnveden and Johansson2022). Further, producers must consider the risk of low return rates, potentially making it necessary to procure new packaging (Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster and Worrell2020). Due to reasons of cost efficiency, the cleaning and repackaging facilities need to be in proximity of collection locations to ensure lower transportation time and emissions, and therefore lower personnel costs and potential costs to offset CO2 emissions (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Hasselström, Finnveden and Johansson2022).

Brand identity in relation to DRS is another concern, as standardized DRS packaging may present limited opportunities for marketing purposes (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Styles and Thomas Lane2022). Brand identity is essential for companies to differentiate themselves from the competition and maintain customer recognition and awareness (Jain, Reference Jain2017). Brand identity is influenced by graphics, colour and text on the container as well as by the shape of the container itself, and it plays a particularly vital role in communicating the values, ideals and intentions of the company to the customer (Hawkins, Reference Hawkins2012).

Consumer behaviour and convenience play a major role in the implementation of DRS. It is crucial that deposit return locations are located conveniently, geographically speaking, for consumers to encourage participation in DRS (Romanillos et al., Reference Romanillos, Williams and Wever2024). For example, in Halifax (Nova Scotia, Canada), cans and glass bottles must be returned to a recycling center, not to the location of purchase (Divert NS, 2024). DRS also need to consider different population variables, as the uptake may vary with socioeconomic background, gender or physical ability (Song et al., Reference Song, Lee and Jung2020; Kremel, Reference Kremel2023). Consumer acceptance further depends on the awareness of alternative packaging options, as a study of returnable take-out food packaging in Germany showed (Theobald et al., Reference Theobald, Mich, Hillesheim, Hartard and Rohn2024). The up-front deposit cost of the packaging also needs to be considered (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Hasselström, Finnveden and Johansson2022).

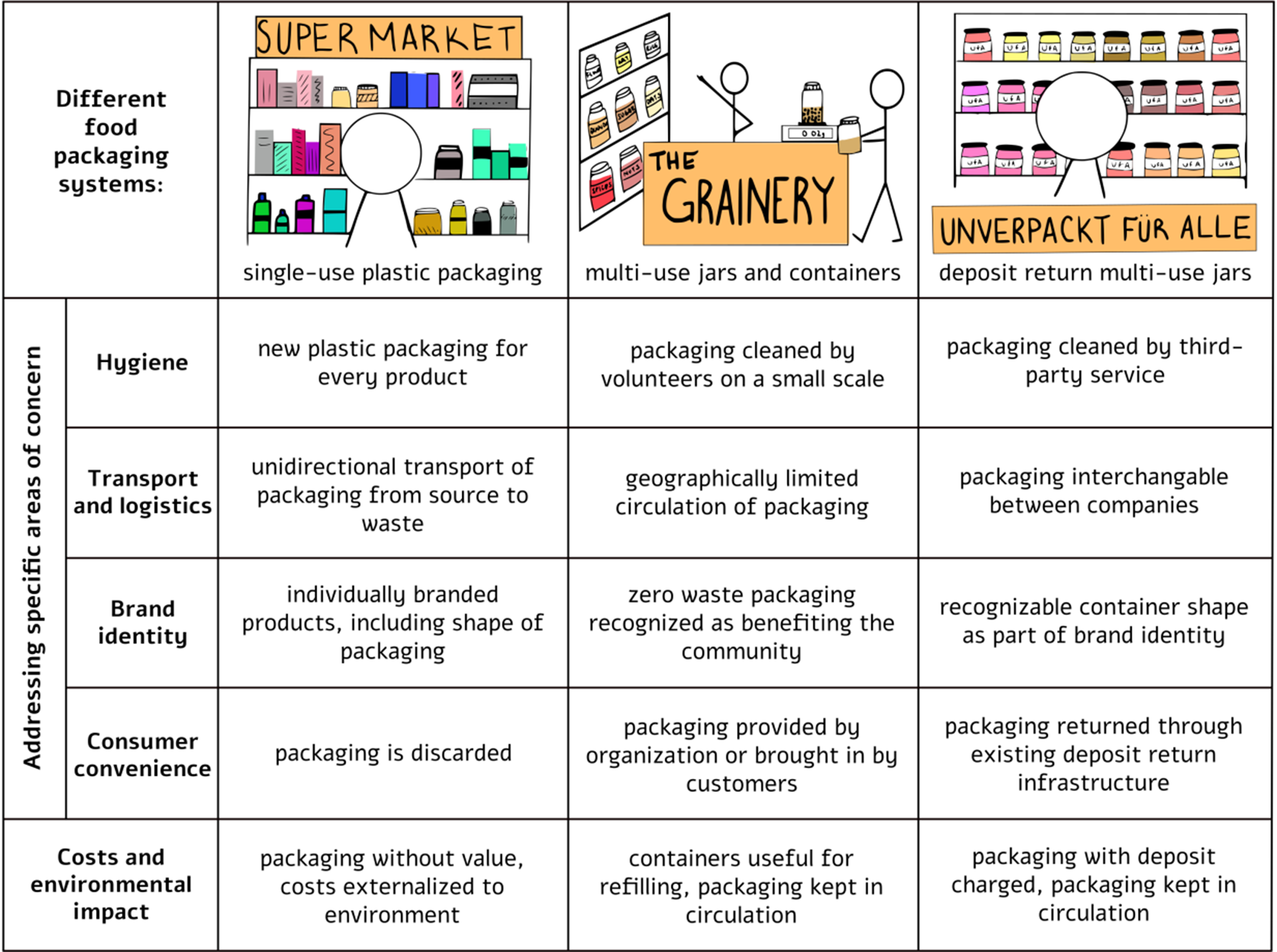

Most of these areas of concerns incur costs to stakeholders participating in DRS, or inconvenience consumers. This is because DRS (at least) partially internalize the costs that companies using single-use plastic packaging externalize to the environment (Morales-Caselles et al., Reference Morales-Caselles, Viejo, Martí, González-Fernández, Pragnell-Raasch, González-Gordillo, Montero, Arroyo, Hanke, Salvo, Basurko, Mallos, Lebreton, Echevarría, van Emmerik, Duarte, Gálvez, van Sebille, Galgani and Cózar2021; Cowger et al., Reference Cowger, Willis, Bullock, Conlon, Emmanuel, Erdle and Wang2024). Based on these areas of concern, we evaluated two innovative packaging reuse systems for solid and semi-solid food products. They are employed by The Grainery in Canada (a food cooperative based in Halifax, comparable to a zero-waste store) and Unverpackt für Alle in Germany (a company using a singular standardized reusable glass jar for their products). We interviewed representatives of the two organizations to illustrate their insights in navigating these areas of concerns to implement sustainable packaging solutions to avoid the generation of single-use plastic waste.

Methods

Interviews were conducted with two stakeholders implementing variations of packaging reuse systems for food products: a representative from The Grainery (Canada) and Unverpackt für Alle (Germany), respectively. Canada and Germany were selected as the case study locations since we are familiar with the plastic pollution problem, as well as the waste, recycling, and DRS in these two countries. Since research surrounding packaging return systems for food products is relatively novel, this knowledge – along with the definition of key areas of concern above – helped to formulate the questions for the semi-structured interviews. It further facilitated finding interview partners.

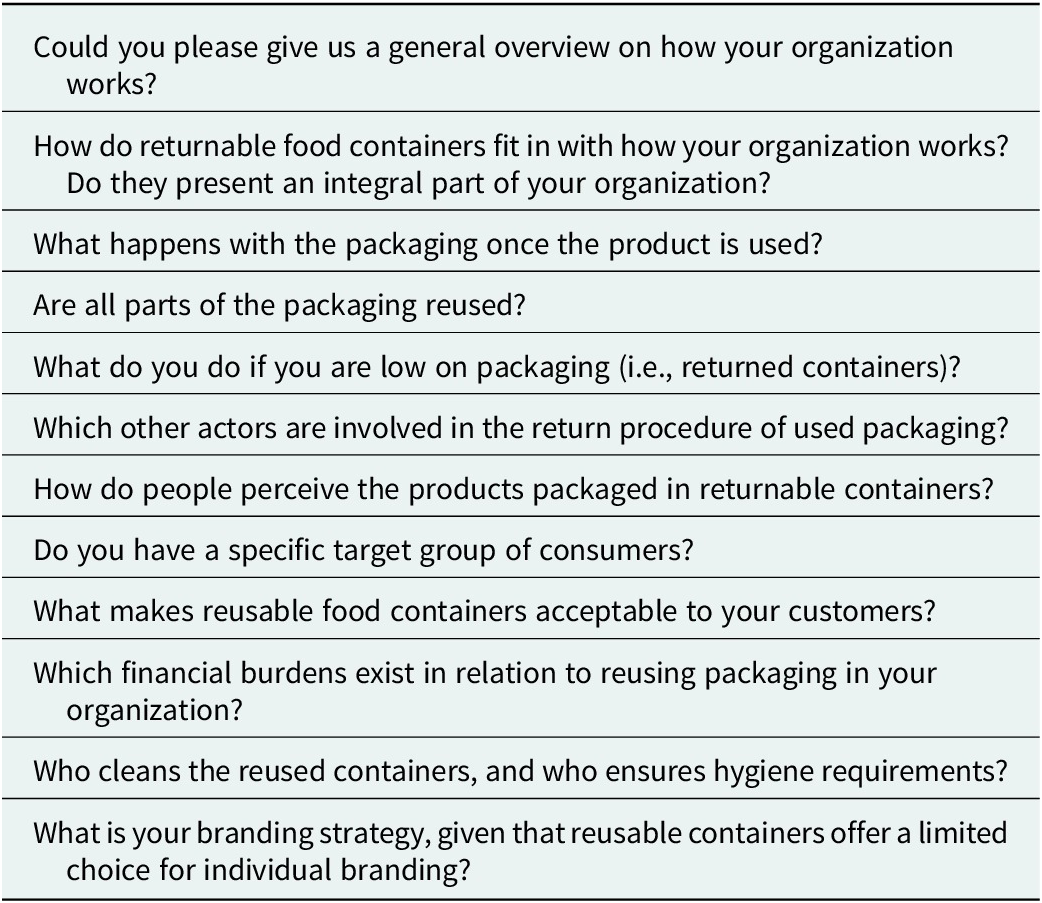

The interview with the representative from The Grainery was conducted in person, while the representative from Unverpackt für Alle was interviewed online (using Zoom software). The interviews lasted between 30 and 45 minutes and were transcribed using Microsoft Word text-to-speech and TurboScribe. Interviews were semi-structured; first, the representatives were asked to give general information about business practices and the implemented packaging return system. This was followed up by questions covering areas of concern described previously to supplement information (Table 1). After the interview, both representatives subsequently reviewed the text about their respective organizations to ensure that the data collected during the interviews were accurate.

Table 1. Prepared questions to guide the semi-structured interviews with representatives from The Grainery and Unverpackt für Alle

Note: Apart from the first question, the other questions were asked in unspecified order or omitted if the topic was already sufficiently covered by other answers.

Results

The Grainery – Local packaging return system with a focus on consumer interaction

The Grainery is a volunteer-run bulk food co-operative in Halifax, Nova Scotia (Canada). One of the main goals of The Grainery is to keep their products as package free as possible, thereby representing concepts of a zero-waste store (Figure 1A). The Grainery facilitates processes related to transport and logistics: customers can bring in their own containers or opt for empty, previously used containers provided by the store. Most of The Grainery’s food is delivered in bulk from organic and/or local wholesalers. The products come in bags or cardboard boxes which they take out for recycling each week or give to customers for reuse. Concerning hygiene, there is no concern of cross contamination of products through contact with customer containers as the customer does not fill their own containers. Customers bring their desired product to the counter and The Grainery’s volunteers pour the product into the customer’s container. Containers are tared (meaning the weigh scale is zeroed with the empty container) before filling and the customer is charged according to the price listed. Volunteers are responsible for cleaning all donated containers and keeping the stores sanitation up to provincial standards (additionally maintained by health and safety inspectors).

Figure 1. (A) Products sold in bulk at the food cooperative, The Grainery in Halifax, Canada. Copyright: The Grainery. (B) Products of Unverpackt für Alle sold in deposit return glass jars (MMP containers) in Germany. Copyright: Venividiwander.

The Grainery’s brand identity is tied to their focus on interacting with their clientele to build lasting relationships within the community. The store has been able to operate for over 20 years with low profit margins and zero full-time employees because of their focus on community, volunteerism and sustainability. The Grainery’s packaging return system can positively influence consumer behaviour and convenience by providing clean, reusable containers and handling the transfer of products, thus removing barriers such as time, effort and sanitation concerns that often discourage sustainable practices (Figure 2). The Grainery functions at low cost, with small profit margins, operating solely on volunteers to run the store, so it is able to offer products below the prices of typical supermarkets. According to the interview partner, The Grainery promotes an environmentally responsible community through meaningful interactions with volunteers and demonstrates that eco-friendly choices do not need to be expensive or inconvenient.

Figure 2. Three approaches to food packaging, illustrating how important concerns relating to food packaging are addressed by regular supermarkets, The Grainery and Unverpackt für Alle, respectively. The latter two organizations implement packaging reuse systems to reduce single-use plastic waste. Figure created by Arden Goodfellow (Creative Commons license CC BY 4.0).

Unverpackt für alle – Standardized deposit return containers in convenient locations

Unverpackt für Alle (“Unpackaged for Everybody,” UfA) is a German company, offering an assortment of organic food products including spices, nuts, grains and semi-solid foods (such as nut butters) through a one-size-fits-all packaging. This packaging is the Mach Mehrweg Pool (“Make it Returnable-Pool"; MMP) glass container, which has been used by the dairy industry for decades (Mach Mehrweg Pool, Reference Pool2023; Figure 1B). The MMP container allow UfA to have a cohesive brand identity that is easily recognizable by consumers. The interview partner stated that the uniform look of the MMP glass is not an obstacle for brand recognition but rather an integral part of their brand identity and emphasizes the overall mission of UfA to offer sustainable products through sustainable packaging. The MMP containers are filled by UfA and sent to supermarkets, including a barcode, so the product can be purchased by customers like any other item in the supermarket. The empty container can be brought back to any supermarket that sells products in MMP glasses (not limited to products by UfA) and is returned through the same reverse vending machine accepting other deposit return packaging such as plastic and glass bottles and aluminum cans. These easy purchasing and return experiences positively influence consumer behavior and convenience.

Regarding transport and logistics, contrary to other deposit return packaging in Germany, MMP glass does not need to be brought back to the company that had originally filled it, as the glass is not specific to an individual company and, excluding the label, is not branded. UfA purchases returned MMP glasses, sends them to a company providing all-inclusive services related to the hygiene of the glasses (including removal of labels), and then refills them. Importantly, and in contrast to the regular DRS in place in Germany for most beverage bottles, upon purchase of the contained product, the container changes ownership as well (i.e., the packaging is not rented). In case not enough MMP glasses are available via returns, new ones are ordered from a glass factory at approximately the same cost per container compared to the cleaning process of the glass. UfA’s interview partner stated that one MMP glass can complete 30–50 cycles before it becomes too degraded to be refilled. The lid, consisting of tinplate and a rubber seal, is not reused but recycled (though not downcycled). The interview partner noted the importance of offering competitive pricing, even though their products are likely to cater to more environmentally conscious consumers and therefore emphasized the importance of scalability to remain cost-efficient, for example, in terms of using the mentioned central and all-inclusive third-party cleaning services (Figure 2).

Discussion

Food packaging return systems as a chance to reduce single-use plastics

Studies show that consumers increasingly care about sustainable choices while purchasing food products, in addition to the cost and health implications (Tobi et al., Reference Tobi, Harris, Rana, Brown, Quaife and Green2019). In the past years, zero-waste shopping has become an increasing trend that satisfies this consumer desire (Watson and Smith, Reference Watson and Smith2020). However, these, often small-scale businesses, are susceptible to disruptions, as the COVID-19 pandemic showed, overshadowing concerns for the environment with strict hygiene requirements (Vanapalli et al., Reference Vanapalli, Sharma, Ranjan, Samal, Bhattacharya, Dubey and Goel2021; Molloy et al., Reference Molloy, Varkey and Walker2022) and forcing many businesses to (temporarily) stop their sale of bulk food products or prohibiting the sale in containers that customers brought in (Varkey et al., Reference Varkey, Walker and Saunders2021; Molloy et al., Reference Molloy, Varkey and Walker2022). In this study, we showed how two organizations developed resilient approaches to offer zero-waste shopping opportunities to their customers while addressing main areas of concern (i.e., costs associated with the hygiene of reusable packaging, demand for efficient transport and logistical processes, limited opportunities for brand identity on uniform containers, and consumer behavior and convenience dealing with reusing product packaging).

These case studies also highlight that packaging reuse systems need to be adaptable to their specific context and to consider the scale of operation. The Grainery is a local initiative, operating for more than 20 years and is rooted in the community. As a volunteer-based organization it takes financial costs for personnel out of the equation, which also allows The Grainery to offer their products at competitive prices and instead focuses on community engagement to sustain business. This advantage of building social capital has been identified for other volunteer-run and participatory food initiatives (Richards and Reed, Reference Richards and Reed2015; Rondeau et al., Reference Rondeau, Stricker, Kozachenko and Parizeau2020). One downside is the reliance on volunteer availability, for example, for cleaning containers and maintaining convenient opening hours, which, in turn, might inconvenience consumers. Apart from offering a waste-free shopping experience for their bulk products, the case of The Grainery shows that there is space for and value in interacting with other people while procuring groceries. This contrasts with shopping for groceries in supermarkets, which has become increasingly centralized in the hands of few companies (Van Dam et al., Reference Van Dam, Wood, Sacks, Allais and Vandevijvere2021; Gaucher-Holm et al., Reference Gaucher-Holm, Wood, Sacks and Vanderlee2023), and lately increasingly anonymous through the implementation of self-serve checkouts (Leung & Matanda, Reference Leung and Matanda2013), and doorstep food drop-off (Khandpur et al., Reference Khandpur, Zatz, Bleich, Taillie, Orr, Rimm and Moran2020).

In contrast to The Grainery, Unverpackt für Alle sells products at a national scale and takes advantage of the convenience of supermarkets and online shopping. It operates as a regular business and has turned a competitive disadvantage (limited branding opportunities for food packaging) into an integral part of their brand identity. This marketing strategy is used to create visual uniform displays in supermarket shelves (known as “blocking,” Deng et al., Reference Deng, Kahn, Unnava and Lee2016) and communicates UfA’s focus on sustainability to consumers. These uniform containers can be exchanged with other companies, as the containers are not branded. Furthermore, UfA takes advantage of existing deposit return infrastructure in Germany in almost every supermarket for beverage DRS (for single-use as well as multi-use containers; Rhein and Sträter, Reference Rhein and Sträter2021). Interestingly, our interview partner at UfA noted that the existing glass containers are not always the technologically best solution for specific products, yet due to universal use, the MMP glass remains the container of choice. Therefore, UfA is placing environmental concerns above technological solutions to avoid the use of single-use plastics.

Overall, all packaging reuse systems imply costs to producers, packagers and retailers, and are at least slightly inconvenient for consumers. This is due to internalizing costs, that are commonly externalized, either to the environment, for example, due to excessive use of single-use plastic packaging for food products (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Awasthi, Wei, Tan and Li2021; Ncube et al., Reference Ncube, Ude, Ogunmuyiwa, Zulkifli and Beas2021) or to taxpayers through waste collection and recycling programs (see da Cruz et al., Reference da Cruz, Ferreira, Cabral, Simões and Marques2014 and Pan et al., Reference Pan, Bolingbroke, Ng, Richter and Vu2019 for some European countries, and Canada, respectively). On the other hand, many packaging reuse systems are effective in keeping targeted product packaging out of the environment (Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Gu, Wu, Gong, Mu, Han and Chang2020; Görgün et al., Reference Görgün, Adsal, Misir, Aydin, Ergün, Keskin, Acar and Ergenekon2021; Schneider et al., Reference Schneider, Tomić and Raal2021) and have further potential positive consequences, for example, raising consumer’s environmental awareness (Miao et al., Reference Miao, Magnier and Mugge2023), increasing extended producer responsibility (Diggle and Walker, Reference Diggle and Walker2020; Diggle and Walker, Reference Diggle and Walker2022; Laubinger et al., Reference Laubinger, Brown, Borkey and Dubois2022; Diggle et al., Reference Diggle, Walker and Adams2023), causing food packagers and retailers to rethink their business models (Coelho et al., Reference Coelho, Corona, ten Klooster and Worrell2020), and promote a reuse culture, one of the primary goals of the circular economy approach (Calabrese et al., Reference Calabrese, Costa, Levialdi Ghiron, Menichini, Miscoli and Tiburzi2021). Similarly, the two exemplary case studies showed how packaging return systems are used as a central component to further community building and developing innovative business approaches.

Limitations and recommendations for packaging reuse systems

Findings are limited to insights from two case studies from Canada and Germany, and therefore, to countries with globalized and industrialized food systems (Van Dam et al., Reference Van Dam, Wood, Sacks, Allais and Vandevijvere2021; Gaucher-Holm et al., Reference Gaucher-Holm, Wood, Sacks and Vanderlee2023). The Grainery and Unverpackt für Alle represent smaller actors in these systems, which are often at the forefront of establishing waste reduction practices. Therefore, further research is needed to explore the applicability of these insights for countries with different food systems (e.g., still involving a majority of local and small-scale food producers and processors e.g., Chilote and Dhakal, Reference Chilote and Dhakal2025) as well as for different stakeholders within these systems (e.g., larger corporations acting as food producers and retailers). Investigating the needs of other stakeholders (such as farmers, food processors, retailers and different groups of consumers) is vital to extend the applicability of the presented research. Future studies should also investigate and compare the environmental impacts of various food packaging containers that could be used for packaging reuse systems through life cycle assessments, considering potential benefits to the environment through the reduction of pollution by single-use plastics (Maga et al., Reference Maga, Galafton, Blömer, Thonemann, Özdamar and Bertling2022; Jiao et al., Reference Jiao, Ali, Alsharbaty, Elsamahy, Abdelkarim, Schagerl and Sun2024).

Considering these limitations, we suggest that successful packaging reuse systems for food products implemented at the scale of the two case studies (i) use either existing containers that consumers have access to, or use standardized containers that are accessible to a variety of companies, and are, therefore, not physically modified to accommodate branding, (ii) focus on reusable containers rather than representing efficient waste collection for single-use containers destined to be disposed or recycled, (iii) fit in with existing solutions, such as already established DRS for beverage containers, (iv) cater to the daily routine of consumers, not inconveniencing them with different drop off locations or requiring them to bring in empty containers for shopping, (v) clearly communicate sustainability goals to consumers and (vi) have municipal and governmental support, for example, to allow for different scales of implementation and consider business practices by smaller organizations.

Conclusion

We explored how two organizations developed resilient strategies to offer zero-waste shopping options. The Grainery, a volunteer-driven, local initiative based in Halifax, Canada, focuses on connecting the local community with organic, zero-waste products and utilizing used containers for packaging. Unverpackt für Alle, based in Germany, leverages the convenience of large supermarkets and uses uniform container sizes as a core element of their brand identity. They focus on reusing packaging instead of an efficient collection of single-use containers for recycling through DRS. While no perfect return system for food packaging exists, these case studies suggest that market-driven approaches, which prioritize technological solutions and the availability of food products regardless of origin or season, are insufficient to tackle excessive single-use plastic production and waste. Success hinges on addressing costs related to hygiene, transport and logistics, brand identity and consumer convenience and behavior through thoughtful design, scalability and collaboration – key factors for leveraging packaging return systems to contribute to global policy-making efforts to reduce the impacts of the growing plastic pollution crisis.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/plc.2025.10034.

Data availability statement

To ensure anonymity of the interview partners, the transcript of the interviews was not published. No further data were used to inform the results of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the willingness of the interview partners to share insights into the approaches, philosophies and working practices of their organizations. Without their involvement, this study would not have been possible! We are further grateful for the comments of two anonymous reviewers and the editor. Their constructive feedback has substantially improved this paper.

Author contribution

AG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – Original draft preparation. TRW: Writing – Reviewing and Editing, Supervision. TK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – Original draft preparation, Supervision.

Financial support

Arden Goodfellow received funding from the Government of Canada’s New Frontiers in Research Fund – Exploration. Tony R. Walker was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Grant/Award Number: RGPIN-2018-04119. Tim Kiessling received funding by Kiel University – “Zukunftsvertrag Studium und Lehre stärken” and the Ocean Frontier Institute’s Visiting Fellowship Program 2024, through an award from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.