1. Introduction

Falling liquid films intervene in many engineering applications, such as rectification columns containing structured packings for cryogenic air separation (Fair & Bravo Reference Fair and Bravo1990). In this configuration, the liquid film is subject to a turbulent counter-current gas flow within narrow channels (Valluri et al. Reference Valluri, Matar, Hewitt and Mendes2005), which exacerbates the risk of flooding (Bankoff & Lee Reference Bankoff and Lee1986). In particular, surface waves forming due to the long-wave Kapitza instability (Kapitza Reference Kapitza1948) have been shown to trigger different types of flooding events, such as an obstruction of the channel cross-section (Vlachos et al. Reference Vlachos, Paras, Mouza and Karabelas2001), wave reversal (Tseluiko & Kalliadasis Reference Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2011), fragmentation and droplet entrainment (Zapke & Kröger Reference Zapke and Kröger2000), or (partial) liquid arrest (Trifonov Reference Trifonov2010, Reference Trifonov2019).

In the experiments of Kofman, Mergui & Ruyer-Quil (Reference Kofman, Mergui and Ruyer-Quil2017), which were performed in a weakly inclined falling liquid film sheared by a counter-current turbulent gas flow, flooding was triggered not by long waves, but via upward-travelling short ripples that overpower the Kapitza instability when the counter-current gas flow rate is increased. Recently, Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) linked the origin of these ripples to a new interfacial short-wave (ISW) instability mode revealed via a temporal stability analysis. By short-wave instability mode, we mean an instability mode that displays a finite wave number at neutral stability, as opposed to a long-wave instability mode, for which the onset of instability occurs at zero wave number. In the current manuscript, we extend the work of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) in two ways.

First, to characterise the nature of the ISW instability mode, we perform spatio-temporal linear stability calculations (Huerre & Monkewitz Reference Huerre and Monkewitz1990). In particular, we seek to identify the growth scenario of the ISW mode, i.e. to determine whether the instability is upward-convective, absolute or downward-convective. Further, our spatio-temporal analysis allows to identify the most-amplified instability mode, i.e. the one expected in an experiment, even beyond the absolute instability (AI) limit. This is particularly useful in our current study, where the ISW mode becomes unstable beyond the AI limit of the long-wave Kapitza mode. In addition, we seek to know whether the ISW mode can merge with the classical long-wave Kapitza mode upon increasing the counter-current gas flow rate, as was suggested by the temporal stability calculations of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023). We find that merging is also observed in the spatio-temporal formulation, but for larger inclination angles compared with the temporal formulation. This merging occurs beyond the AI limit of the Kapitza mode and, depending on the inclination angle, the most-amplified merged mode is associated either with positive or negative group velocities.

Second, we seek to determine the effect of the relevant control parameters, i.e. inclination angle,

![]() $\beta$

, channel height,

$\beta$

, channel height,

![]() $H^\star$

(stars denote dimensional quantities throughout), liquid (subscript L) and gas (subscript G) Reynolds numbers,

$H^\star$

(stars denote dimensional quantities throughout), liquid (subscript L) and gas (subscript G) Reynolds numbers,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

and

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

, and fluid properties, on the threshold of the ISW mode, whereas Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) considered only a single set of conditions (

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

, and fluid properties, on the threshold of the ISW mode, whereas Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) considered only a single set of conditions (

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

,

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

,

![]() $H^\star =13 \,\textrm {mm}$

,

$H^\star =13 \,\textrm {mm}$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

= 43.1). In particular, we are interested in knowing what happens to the ISW mode when the inclination angle is increased and we compare our linear stability predictions with appropriate new experiments that we have performed. We also investigate the limiting case of a vertically falling liquid film. The existence of upward-travelling ripples in that configuration is highly relevant for predicting flooding conditions in rectification columns used for cryogenic air separation. For this case, we find that upward-travelling linear waves linked to the ISW mode indeed exist, albeit as part of the merged mode. Another question that we address is whether turbulence in the gas flow is necessary for the ISW mode to exist. We find that turbulence is not required in theory, but that impracticable counter-current gas flow rates, i.e. far beyond the threshold for fully turbulent flow, are required to produce the ISW mode under the assumption of a laminar gas velocity profile. Further, we find that the difference in shape of the turbulent gas velocity profile significantly affects the ISW and merged modes.

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

= 43.1). In particular, we are interested in knowing what happens to the ISW mode when the inclination angle is increased and we compare our linear stability predictions with appropriate new experiments that we have performed. We also investigate the limiting case of a vertically falling liquid film. The existence of upward-travelling ripples in that configuration is highly relevant for predicting flooding conditions in rectification columns used for cryogenic air separation. For this case, we find that upward-travelling linear waves linked to the ISW mode indeed exist, albeit as part of the merged mode. Another question that we address is whether turbulence in the gas flow is necessary for the ISW mode to exist. We find that turbulence is not required in theory, but that impracticable counter-current gas flow rates, i.e. far beyond the threshold for fully turbulent flow, are required to produce the ISW mode under the assumption of a laminar gas velocity profile. Further, we find that the difference in shape of the turbulent gas velocity profile significantly affects the ISW and merged modes.

We proceed by discussing the state of the art, whereby we will focus on two aspects. First, we will briefly summarise the different instability modes that have been observed in gas-sheared falling liquid films, with the aim of highlighting the specificity of the ISW mode. For a more detailed account, the reader is referred to several comprehensive works (Tilley, Davis & Bankoff Reference Tilley, Davis and Bankoff1994; Boomkamp & Miesen Reference Boomkamp and Miesen1996; Vellingiri, Tseluiko & Kalliadasis Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015; Trifonov Reference Trifonov2017; Lavalle et al. Reference Lavalle, Li, Mergui, Grenier and Dietze2019; Kushnir et al. Reference Kushnir, Barmak, Ullmann and Brauner2021; Aktershev, Alekseenko & Tsvelodub Reference Aktershev, Alekseenko and Tsvelodub2022; Ishimura et al. Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023). Second, we will discuss previous works that have applied the concept of spatio-temporal linear stability analysis to (gas-sheared) falling liquid films.

An isothermal falling liquid film flowing in a passive atmosphere along a plane incline is subject to two instabilities. The first one is the inertia-driven long-wave Kapitza instability (Brooke Benjamin Reference Brooke Benjamin1957; Yih Reference Yih1963; Dietze Reference Dietze2016), for which the critical value of the Reynolds number,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

=

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

=

![]() $q^\star _{{L}}$

/

$q^\star _{{L}}$

/

![]() $\nu _{{L}}$

(the star superscript denotes dimensional quantities throughout), is given by

$\nu _{{L}}$

(the star superscript denotes dimensional quantities throughout), is given by

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

=

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

=

![]() $5$

/

$5$

/

![]() $6\cot (\beta )$

, where

$6\cot (\beta )$

, where

![]() $\beta$

,

$\beta$

,

![]() $q^\star _{{L}}$

and

$q^\star _{{L}}$

and

![]() $\nu _{{L}}$

denote the inclination angle, liquid flow rate per unit width and liquid kinematic viscosity (subscripts

$\nu _{{L}}$

denote the inclination angle, liquid flow rate per unit width and liquid kinematic viscosity (subscripts

![]() ${L}$

and

${L}$

and

![]() ${G}$

refer to the liquid and gas throughout). The second one is the short-wave Tollmien–Schlichting instability (Floryan, Davis & Kelly Reference Floryan, Davis and Kelly1987; Samanta Reference Samanta2020), which appears at extremely small

${G}$

refer to the liquid and gas throughout). The second one is the short-wave Tollmien–Schlichting instability (Floryan, Davis & Kelly Reference Floryan, Davis and Kelly1987; Samanta Reference Samanta2020), which appears at extremely small

![]() $\beta$

and very large

$\beta$

and very large

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

. The latter conditions are outside the scope of the current manuscript.

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

. The latter conditions are outside the scope of the current manuscript.

Subjecting a falling liquid film to a counter-current gas flow within a narrow channel greatly affects the Kapitza instability. In the case of small inclination angles, the effect of the gas is stabilising (Lavalle et al. Reference Lavalle, Li, Mergui, Grenier and Dietze2019; Kushnir et al. Reference Kushnir, Barmak, Ullmann and Brauner2021), whereas it is destabilising for large inclination angles (Trifonov Reference Trifonov2017; Kushnir et al. Reference Kushnir, Barmak, Ullmann and Brauner2021). Moreover, the gas flow can render the falling film unconditionally stable or unconditionally unstable in these respective configurations, both for laminar (Dietze Reference Dietze2022) and turbulent (Ishimura et al. Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) flow conditions. Further, Vellingiri et al. (Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015) showed via a spatial stability analysis that a turbulent counter-current gas flow can cause a transition of the Kapitza instability on a vertically falling liquid film from downward-convective to upward-convective. However, because the film thickness of the primary flow,

![]() $h_0$

(we will use the subscript 0 to designate the primary flow throughout), was fixed in their calculations, the sign of the liquid flow rate also changed. In our current work, we have considered only positive liquid flow rates, i.e.

$h_0$

(we will use the subscript 0 to designate the primary flow throughout), was fixed in their calculations, the sign of the liquid flow rate also changed. In our current work, we have considered only positive liquid flow rates, i.e.

![]() $q_{{L}}\gt 0$

, and, thus, the term upward-convective implies that waves travel counter to the average liquid flow. We will show in the current manuscript (see e.g. figure 15

d) that the Kapitza instability mode is never upward-convective in that case, but it does become absolutely unstable. Further, our spatio-temporal stability analysis has allowed us to produce data inaccessible to the spatial stability calculations of Vellingiri et al. (Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015), i.e. within the parameter gap where these authors observed AI of the Kapitza instability mode (figure 9).

$q_{{L}}\gt 0$

, and, thus, the term upward-convective implies that waves travel counter to the average liquid flow. We will show in the current manuscript (see e.g. figure 15

d) that the Kapitza instability mode is never upward-convective in that case, but it does become absolutely unstable. Further, our spatio-temporal stability analysis has allowed us to produce data inaccessible to the spatial stability calculations of Vellingiri et al. (Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015), i.e. within the parameter gap where these authors observed AI of the Kapitza instability mode (figure 9).

Two additional gas-induced instability modes were identified in the seminal work of Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016), who studied vertically falling liquid films sheared by a counter-current laminar gas flow via temporal linear stability analysis. The first one is a gas-side short-wave Tollmien–Schlichting mode, which was studied in detail by Trifonov (Reference Trifonov2017). In that work, it was shown that the corresponding neutral stability bound remains close to the classical result for single-phase channel flow, i.e.

![]() $|{\textit{Re}}_G|$

=

$|{\textit{Re}}_G|$

=

![]() $({4}/{3})5772$

= 7696 (Orszag Reference Orszag1971), where

$({4}/{3})5772$

= 7696 (Orszag Reference Orszag1971), where

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

=

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

=

![]() $q_{{G}}^\star$

/

$q_{{G}}^\star$

/

![]() $\nu _{{G}}$

denotes the (signed) gas Reynolds number based on the (signed) gas flow rate per unit width,

$\nu _{{G}}$

denotes the (signed) gas Reynolds number based on the (signed) gas flow rate per unit width,

![]() $q_{{G}}^\star$

, and the gas kinematic viscosity,

$q_{{G}}^\star$

, and the gas kinematic viscosity,

![]() $\nu _{{G}}$

. In particular, the stability bound is almost insensitive to the inclination angle of the falling liquid film. By contrast, we find in our current study that the ISW mode depends strongly on

$\nu _{{G}}$

. In particular, the stability bound is almost insensitive to the inclination angle of the falling liquid film. By contrast, we find in our current study that the ISW mode depends strongly on

![]() $\beta$

. Also, Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) have shown that the eigenfunctions of the ISW mode display maxima at the film surface, thus proving that this mode is indeed an interfacial one, whereas the growth mechanism of the Tollmien–Schlichting mode is localised in the bulk of the gas flow. The second gas-induced instability mode identified by Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016) is a long-wave so-designated internal mode, which can coalesce with the interfacial Kapitza mode. This mode appears at very large counter-current gas flow rates, i.e.

$\beta$

. Also, Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) have shown that the eigenfunctions of the ISW mode display maxima at the film surface, thus proving that this mode is indeed an interfacial one, whereas the growth mechanism of the Tollmien–Schlichting mode is localised in the bulk of the gas flow. The second gas-induced instability mode identified by Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016) is a long-wave so-designated internal mode, which can coalesce with the interfacial Kapitza mode. This mode appears at very large counter-current gas flow rates, i.e.

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 10\times 10^{4}$

.

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 10\times 10^{4}$

.

Most recently, Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) identified an ISW instability mode via temporal linear stability calculations based on the Navier–Stokes equations in the liquid film and the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations in the turbulent gas flow. In contrast to other studies (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016; Trifonov Reference Trifonov2017), turbulence was accounted for in the primary flow, which was made possible by techniques introduced in several previous works (Náraigh et al. Reference Náraigh, Spelt and Shaw2013; Vellingiri et al. Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015; Camassa, Ogrosky & Olander Reference Camassa, Ogrosky and Olander2017). Also, linear perturbations of the Reynolds stresses were accounted for, i.e. the quasi-laminar assumption (Miles Reference Miles1957; Brooke Benjamin Reference Brooke Benjamin1959) was not applied, although this is not always necessary (Náraigh et al. Reference Náraigh, Spelt, Matar and Zaki2011). The calculations of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) were performed for a single parameter set corresponding to a specific experiment by the same authors, i.e. a falling water film sheared by a counter-current air flow in a channel of height,

![]() $H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

, inclined at a small angle,

$H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

, inclined at a small angle,

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

, for a fixed liquid Reynolds number,

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

, for a fixed liquid Reynolds number,

![]() ${{\textit{Re}}_{{L}}}=43.1$

. It was found that the ISW mode emerges due to the counter-current gas flow and becomes unstable for

${{\textit{Re}}_{{L}}}=43.1$

. It was found that the ISW mode emerges due to the counter-current gas flow and becomes unstable for

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 5000$

. Importantly, this mode is associated with negative wave speeds, i.e. linear waves that travel counter to gravity. Further increase of

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 5000$

. Importantly, this mode is associated with negative wave speeds, i.e. linear waves that travel counter to gravity. Further increase of

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |$

leads to a coalescence of the ISW mode with the Kapitza mode. The most-amplified wave number and the associated (negative) wave speed of the resulting merged mode are dictated by the ISW mode and found to agree well with the upward travelling ripples observed in the experiments.

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |$

leads to a coalescence of the ISW mode with the Kapitza mode. The most-amplified wave number and the associated (negative) wave speed of the resulting merged mode are dictated by the ISW mode and found to agree well with the upward travelling ripples observed in the experiments.

A question that arises from the work of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) is why the ISW mode was not observed in the comprehensive stability analysis of Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016) and the subsequent work of Trifonov (Reference Trifonov2017). On the one hand, this could be due to neglecting turbulence in those two works, which amounts to underpredicting the magnitude of the tangential gas-shear stress at the film surface,

![]() $T_{{{G}} 0}$

, for a given

$T_{{{G}} 0}$

, for a given

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

. In our current study, we have found that the ISW mode persists also in the limit of a laminar gas velocity profile, provided

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

. In our current study, we have found that the ISW mode persists also in the limit of a laminar gas velocity profile, provided

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |$

is increased to reach the level of

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |$

is increased to reach the level of

![]() $T_{{{G}} 0}$

for the corresponding turbulent flow. However, as a result, the neutral stability bound of the ISW mode is shifted to much larger values of

$T_{{{G}} 0}$

for the corresponding turbulent flow. However, as a result, the neutral stability bound of the ISW mode is shifted to much larger values of

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |$

, e.g. from

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |$

, e.g. from

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 5000$

to

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 5000$

to

![]() $\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 25\,000$

for the experimental conditions discussed in the previous paragraph, where

$\left |{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}\right |\approx 25\,000$

for the experimental conditions discussed in the previous paragraph, where

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

.

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

.

On the other hand, Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016) considered only vertically falling liquid films, where the ISW mode may not exist. In our current study, we have found for the vertical case that the merging of the Kapitza and ISW modes occurs before the ISW mode can become unstable on its own. Thus, the ISW mode is hidden in the merged mode for the configuration studied by Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016). Based on the above-mentioned two observations, we have come to the conclusion that the interfacial mode reported by Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016), which displays a growth rate maximum at very large wave number values, is in essence our merged mode. Indeed, the maximally amplified wave number observed in that reference is far greater than those of the liquid-side and gas-side Tollmien–Schlichting modes, which are authentic short-wave modes. Moreover, we find that, as

![]() $\beta$

is decreased from the vertical orientation (

$\beta$

is decreased from the vertical orientation (

![]() $\beta ={90}^\circ$

), our merged mode splits into the (unstable) ISW mode and the classical Kapitza mode.

$\beta ={90}^\circ$

), our merged mode splits into the (unstable) ISW mode and the classical Kapitza mode.

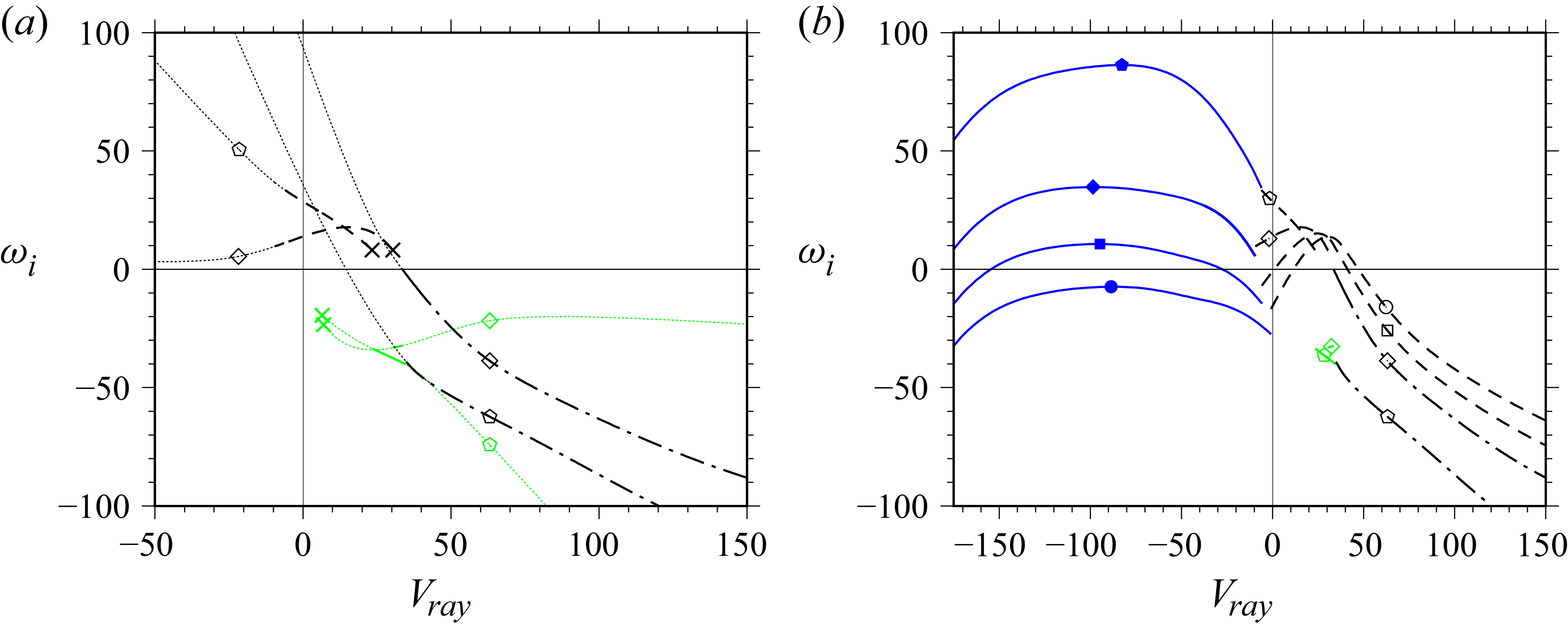

Next, we discuss works from the literature that have applied the concept of spatio-temporal linear stability analysis (Huerre & Monkewitz Reference Huerre and Monkewitz1990) to falling liquid films. In this approach, the Orr–Sommerfeld (OS) eigenvalue problem is written in a reference frame moving with the ray velocity,

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}$

, and both the wave number,

$V_{\textit{ray}}$

, and both the wave number,

![]() $k$

=

$k$

=

![]() $k_r+ik_i$

(subscripts

$k_r+ik_i$

(subscripts

![]() $r$

and

$r$

and

![]() $i$

designate the real and imaginary parts of a complex number), and angular frequency,

$i$

designate the real and imaginary parts of a complex number), and angular frequency,

![]() $\omega$

=

$\omega$

=

![]() $\omega _r+i\omega _i$

, of normal-mode linear perturbations are assumed complex with

$\omega _r+i\omega _i$

, of normal-mode linear perturbations are assumed complex with

![]() $i=\sqrt {-1}$

. Stability or instability is assessed for a given value of

$i=\sqrt {-1}$

. Stability or instability is assessed for a given value of

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}\in \mathbb{R}$

by considering the temporal growth rate,

$V_{\textit{ray}}\in \mathbb{R}$

by considering the temporal growth rate,

![]() $\omega _i$

, of a perturbation that is fixed in the moving reference frame at long times, i.e. for which the group velocity,

$\omega _i$

, of a perturbation that is fixed in the moving reference frame at long times, i.e. for which the group velocity,

![]() $\omega _k$

=

$\omega _k$

=

![]() $\mathrm{d}\omega$

/

$\mathrm{d}\omega$

/

![]() $\mathrm{d}k$

, is zero. A boundary value problem for

$\mathrm{d}k$

, is zero. A boundary value problem for

![]() $\omega _k$

can be obtained by differentiating the OS eigenvalue problem with respect to

$\omega _k$

can be obtained by differentiating the OS eigenvalue problem with respect to

![]() $k$

. Depending on whether

$k$

. Depending on whether

![]() $\omega _i\gt 0$

is observed for

$\omega _i\gt 0$

is observed for

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}\gt 0$

,

$V_{\textit{ray}}\gt 0$

,

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}\lt 0$

or

$V_{\textit{ray}}\lt 0$

or

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}=0$

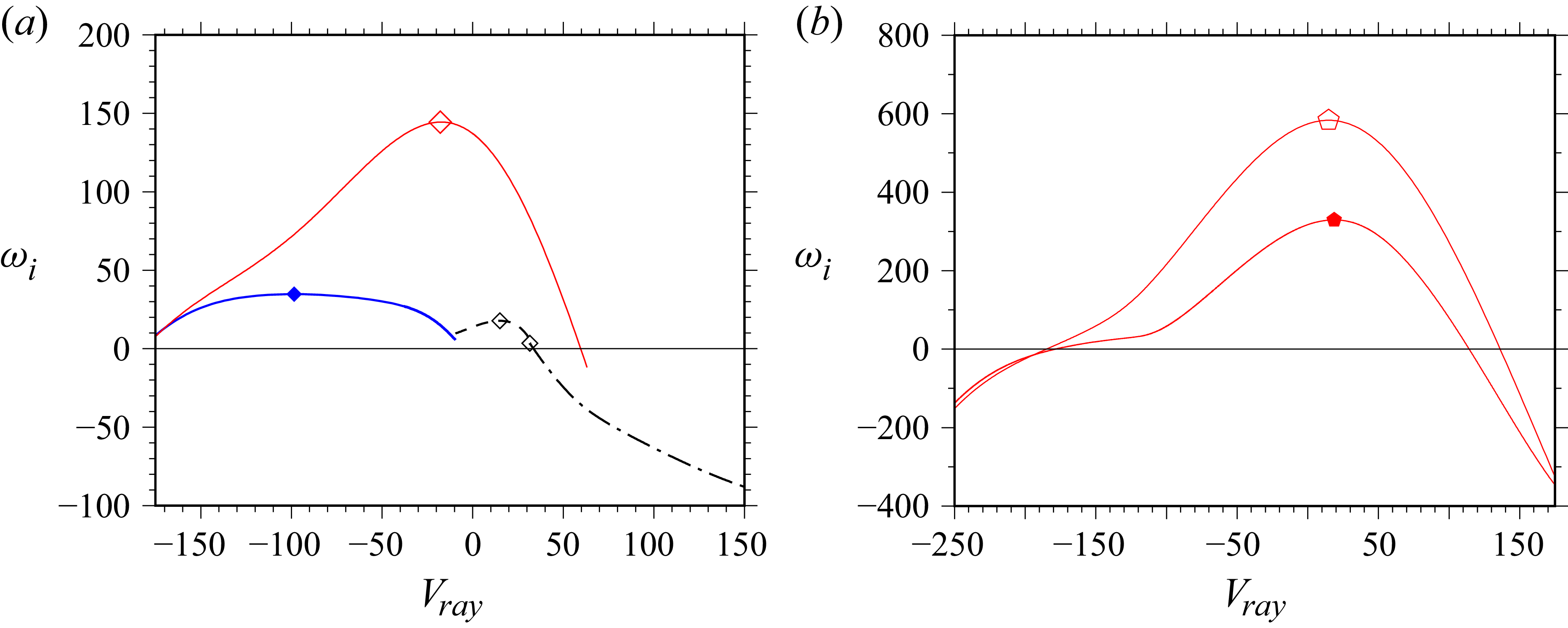

, the instability is designated as downward-convective, upward-convective or absolute. Then, the task is to construct a curve recording

$V_{\textit{ray}}=0$

, the instability is designated as downward-convective, upward-convective or absolute. Then, the task is to construct a curve recording

![]() $\omega _i$

versus

$\omega _i$

versus

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}$

. All points on such a curve are saddle points, where two spatial branches, i.e. curves of constant

$V_{\textit{ray}}$

. All points on such a curve are saddle points, where two spatial branches, i.e. curves of constant

![]() $\omega _i$

and

$\omega _i$

and

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}$

in the

$V_{\textit{ray}}$

in the

![]() $k_i$

–

$k_i$

–

![]() $k_r$

plane, collide as

$k_r$

plane, collide as

![]() $\omega _i$

is decreased from a sufficiently large value (larger than the maximum

$\omega _i$

is decreased from a sufficiently large value (larger than the maximum

![]() $\omega _i$

obtained from a temporal analysis, where

$\omega _i$

obtained from a temporal analysis, where

![]() $k_i$

= 0). An important task is to verify whether these saddle points are physical, i.e. whether the Briggs collision criterion is satisfied (Briggs Reference Briggs1964).

$k_i$

= 0). An important task is to verify whether these saddle points are physical, i.e. whether the Briggs collision criterion is satisfied (Briggs Reference Briggs1964).

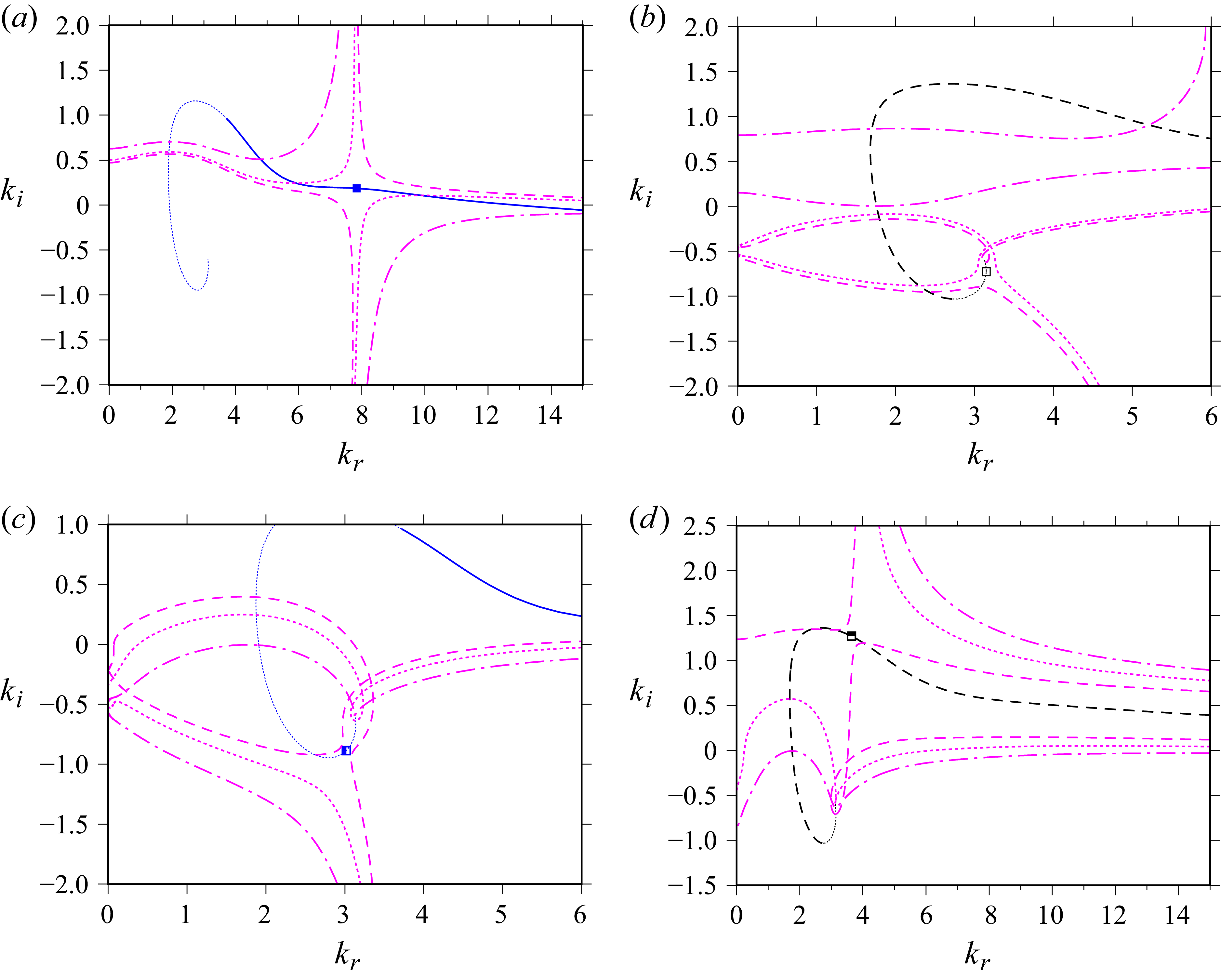

The first spatio-temporal stability investigation related to our problem was published by Brevdo et al. (Reference Brevdo, Laure, Dias and Bridges1999), who studied falling liquid films flowing in a passive atmosphere, and showed that both the Kapitza and Tollmien–Schlichting modes are convectively unstable. Good agreement with the experiments of Liu & Gollub (Reference Liu and Gollub1994) was observed for the predicted spatial growth rate,

![]() $-k_i$

, and angular wave frequency,

$-k_i$

, and angular wave frequency,

![]() $\omega _r$

, of the Kapitza mode. In the current work, we track saddle points via numerical continuation using the software Auto07P (Doedel & Oldeman Reference Doedel and Oldeman2009). This is made possible by the merging of the Kapitza and ISW modes in the temporal formulation, thus providing a continuation path that starts at a known analytical solution, i.e.

$\omega _r$

, of the Kapitza mode. In the current work, we track saddle points via numerical continuation using the software Auto07P (Doedel & Oldeman Reference Doedel and Oldeman2009). This is made possible by the merging of the Kapitza and ISW modes in the temporal formulation, thus providing a continuation path that starts at a known analytical solution, i.e.

![]() $k_r$

=

$k_r$

=

![]() $k_i$

=

$k_i$

=

![]() $\omega _i$

= 0 for the merged mode. However, Brevdo et al. (Reference Brevdo, Laure, Dias and Bridges1999) pointed out that care must be taken when tracking saddle points by continuation, so as not to miss additional saddle-point branches that may arise from a saddle point bifurcation or the sudden end of a physical saddle point branch. For some of the operating conditions considered in our manuscript, this indeed occurs. Further, there are additional instability modes in our configuration, as a result of the counter-current gas flow, in particular, the ISW mode. Thus, for a given

$\omega _i$

= 0 for the merged mode. However, Brevdo et al. (Reference Brevdo, Laure, Dias and Bridges1999) pointed out that care must be taken when tracking saddle points by continuation, so as not to miss additional saddle-point branches that may arise from a saddle point bifurcation or the sudden end of a physical saddle point branch. For some of the operating conditions considered in our manuscript, this indeed occurs. Further, there are additional instability modes in our configuration, as a result of the counter-current gas flow, in particular, the ISW mode. Thus, for a given

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}$

, it needed to be verified which one of several saddle point branches belonging to different instability modes is indeed physical. We have done this by checking the Briggs collision criterion manually at the relevant values of

$V_{\textit{ray}}$

, it needed to be verified which one of several saddle point branches belonging to different instability modes is indeed physical. We have done this by checking the Briggs collision criterion manually at the relevant values of

![]() $V_{\textit{ray}}$

.

$V_{\textit{ray}}$

.

Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016) extended the work of Brevdo et al. (Reference Brevdo, Laure, Dias and Bridges1999) to the case of a falling liquid film sheared by a counter-current laminar fluid flow, in the special case of a moderate density ratio,

![]() $\varPi _\rho$

=

$\varPi _\rho$

=

![]() $\rho _{{G}}$

/

$\rho _{{G}}$

/

![]() $\rho _{{L}}$

, i.e.

$\rho _{{L}}$

, i.e.

![]() $\varPi _\rho$

= 0.1, where

$\varPi _\rho$

= 0.1, where

![]() $\rho$

denotes the mass density. The authors observed AI for several long-wave instability modes and confirmed these observations via direct numerical simulation (DNS) representing the response to a pulse-like perturbation. In the current work, we find that the ISW mode is always upward-convective. However, after the ISW mode has merged with the Kapitza mode, AI is indeed observed.

$\rho$

denotes the mass density. The authors observed AI for several long-wave instability modes and confirmed these observations via direct numerical simulation (DNS) representing the response to a pulse-like perturbation. In the current work, we find that the ISW mode is always upward-convective. However, after the ISW mode has merged with the Kapitza mode, AI is indeed observed.

To conclude this state of the art, we compare the upward-travelling ripples that emanate from our ISW instability mode with wind-driven ripples observed in other configurations (Miles Reference Miles1957; Hanratty & Engen Reference Hanratty and Engen1957; McCready & Chang Reference McCready and Chang1994; Miesen & Boersma Reference Miesen and Boersma1995; Özgen et al. Reference Özgen, Carbonaro and Sarma2002; Alekseenko et al. Reference Alekseenko, Cherdantsev, Heinz, Kharlamov and Markovich2014; Vasques et al. Reference Vasques, Cherdantsev, Cherdantsev, Isaenkov and Hann2018; Burdairon & Magnaudet Reference Burdairon and Magnaudet2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Hector, Rabaud and Moisy2023). Figure 2(c), which represents new experiments that we have performed at

![]() $\beta ={1}^\circ$

, shows a typical example of upward-travelling ripples observed in our configuration. These ripples look similar to the ripples observed in the experiments of Özgen et al. (Reference Özgen, Carbonaro and Sarma2002), where a horizontal film of anti-icing liquid was sheared by an unconfined co-current turbulent gas flow and where the wavelength was of the same order of magnitude, i.e.

$\beta ={1}^\circ$

, shows a typical example of upward-travelling ripples observed in our configuration. These ripples look similar to the ripples observed in the experiments of Özgen et al. (Reference Özgen, Carbonaro and Sarma2002), where a horizontal film of anti-icing liquid was sheared by an unconfined co-current turbulent gas flow and where the wavelength was of the same order of magnitude, i.e.

![]() $\varLambda ^\star \approx {2}\,\textrm {cm}$

versus

$\varLambda ^\star \approx {2}\,\textrm {cm}$

versus

![]() $\varLambda ^\star \approx {1}\,\textrm {cm}$

in our experiment from figure 2. Similar ripples were observed in the recent experiments of Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Hector, Rabaud and Moisy2023), who measured dispersion curves of the spatial growth rate for wind-driven waves in a tank. These dispersion curves are quite similar to dispersion curves of the temporal growth rate obtained by Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) for their short-wave internal mode, via temporal linear stability analysis in the same configuration as Özgen et al. (Reference Özgen, Carbonaro and Sarma2002).

$\varLambda ^\star \approx {1}\,\textrm {cm}$

in our experiment from figure 2. Similar ripples were observed in the recent experiments of Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Hector, Rabaud and Moisy2023), who measured dispersion curves of the spatial growth rate for wind-driven waves in a tank. These dispersion curves are quite similar to dispersion curves of the temporal growth rate obtained by Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) for their short-wave internal mode, via temporal linear stability analysis in the same configuration as Özgen et al. (Reference Özgen, Carbonaro and Sarma2002).

However, there are several differences between the internal mode of Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) and the ISW mode observed in our counter-current falling-film configuration. In particular, we will show that the ISW mode strongly depends on the inclination angle, whereas Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) found their internal mode to be insensitive to the orientation of gravity, which is in line with experimental observations of nonlinear ripples in upward and downward co-current core-annular liquid–gas flows within vertical tubes (Alekseenko et al. Reference Alekseenko, Cherdantsev, Heinz, Kharlamov and Markovich2014; Vasques et al. Reference Vasques, Cherdantsev, Cherdantsev, Isaenkov and Hann2018). Further, the wave speed of the ISW mode is negative, while the primary-flow liquid velocity at the film surface is positive, i.e. the ripples travel upward whereas the liquid moves downward. This means that the critical surface (Miles Reference Miles1957), where wave speed and primary-flow velocity match, lies in the gas phase, in contrast to the internal mode of Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) and the experiments of Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Hector, Rabaud and Moisy2023). Finally, for lack of data in the long-wave limit,

![]() $k_r\to 0$

, it is not clear whether the growth rate curves of Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Hector, Rabaud and Moisy2023) tend towards zero growth rate at

$k_r\to 0$

, it is not clear whether the growth rate curves of Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995) and Zhang et al. (Reference Zhang, Hector, Rabaud and Moisy2023) tend towards zero growth rate at

![]() $k_r$

=

$k_r$

=

![]() $k_i$

= 0, whereas the ISW mode studied in the current manuscript clearly displays a negative temporal growth rate at

$k_i$

= 0, whereas the ISW mode studied in the current manuscript clearly displays a negative temporal growth rate at

![]() $k_r$

= 0 (see e.g. figure 10

a).

$k_r$

= 0 (see e.g. figure 10

a).

Data in the long-wave limit were provided by the temporal stability calculations of McCready & Chang (Reference McCready and Chang1994), who studied a similar configuration to Miesen & Boersma (Reference Miesen and Boersma1995), i.e. a horizontal (or weakly inclined) co-current two-layer liquid/gas channel flow, where ripples had been observed in corresponding experiments (Hanratty & Engen Reference Hanratty and Engen1957). The dispersion curves of the temporal growth rate obtained by McCready & Chang (Reference McCready and Chang1994) for the horizontal configuration display two unstable humps, one in the long-wave limit and another bounded by two finite-valued neutral wave numbers. These curves originate at

![]() $\omega _i$

=

$\omega _i$

=

![]() $k_r$

=

$k_r$

=

![]() $k_i$

= 0. In some sense, they are similar to the temporal growth rate curves obtained in our current manuscript when the Kapitza mode has merged with the ISW mode (see figure 10

a). However, the mode identified by McCready & Chang (Reference McCready and Chang1994) does not separate into a long-wave mode and an unstable short-wave mode upon decreasing the gas flow rate at constant liquid flow rate.

$k_i$

= 0. In some sense, they are similar to the temporal growth rate curves obtained in our current manuscript when the Kapitza mode has merged with the ISW mode (see figure 10

a). However, the mode identified by McCready & Chang (Reference McCready and Chang1994) does not separate into a long-wave mode and an unstable short-wave mode upon decreasing the gas flow rate at constant liquid flow rate.

Thus, although the ripples observed in the above-mentioned co-current configurations share similar features with the ripples in our falling-film configuration, the ISW mode studied in our current manuscript seems to be quite distinct, not the least because it merges with the long-wave Kapitza mode when the counter-current gas flow rate is increased and due to its strong dependence on the inclination angle.

In the current manuscript, we have opted for a two-dimensional linear stability analysis. This is motivated by the relevant earlier works (Vellingiri et al. Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015; Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016; Trifonov Reference Trifonov2017), where a two-dimensional formulation was also used. The spanwise confinement of our experimental channel is quite weak, i.e.

![]() $W^\star$

/

$W^\star$

/

![]() $H^\star \approx 20$

, and, thus, three-dimensional effects on the primary flow are weak. Further, two-dimensional disturbances have been shown to be more unstable than three-dimensional ones for falling liquid films flowing in a passive atmosphere (Yih Reference Yih1955) as well as for falling liquid films sheared by a laminar confined gas flow (Barmak et al. Reference Barmak, Gelfgat, Ullmann and Brauner2017). Having said this, the presence of turbulence in the gas may potentially alter this picture. Thus, a full three-dimensional analysis will need to be done at some point, but this is outside the scope of our current manuscript. Nonetheless, in Appendix A, we have performed the first three-dimensional calculation based on an equivalent two-dimensional formulation that can be obtained via Squire transformation rules (Squire Reference Squire1933) in the limit of neglecting the linear perturbation of the turbulent viscosity. It suggests that three-dimensional perturbations can be slightly (by 4 %) more unstable than two-dimensional ones for the ISW mode, which would imply that the Squire theorem does not hold for our current configuration. However, due to the assumption made on the turbulent viscosity, which in two-dimensional calculations leads to an 8 % error, these preliminary results need to be treated with caution. For the time being, our two-dimensional linear stability calculations, which are in very good agreement with our experiments, are warranted.

$H^\star \approx 20$

, and, thus, three-dimensional effects on the primary flow are weak. Further, two-dimensional disturbances have been shown to be more unstable than three-dimensional ones for falling liquid films flowing in a passive atmosphere (Yih Reference Yih1955) as well as for falling liquid films sheared by a laminar confined gas flow (Barmak et al. Reference Barmak, Gelfgat, Ullmann and Brauner2017). Having said this, the presence of turbulence in the gas may potentially alter this picture. Thus, a full three-dimensional analysis will need to be done at some point, but this is outside the scope of our current manuscript. Nonetheless, in Appendix A, we have performed the first three-dimensional calculation based on an equivalent two-dimensional formulation that can be obtained via Squire transformation rules (Squire Reference Squire1933) in the limit of neglecting the linear perturbation of the turbulent viscosity. It suggests that three-dimensional perturbations can be slightly (by 4 %) more unstable than two-dimensional ones for the ISW mode, which would imply that the Squire theorem does not hold for our current configuration. However, due to the assumption made on the turbulent viscosity, which in two-dimensional calculations leads to an 8 % error, these preliminary results need to be treated with caution. For the time being, our two-dimensional linear stability calculations, which are in very good agreement with our experiments, are warranted.

Our manuscript is structured as follows. In § 2, we will introduce new experimental data that have been obtained in our current study, using the experimental set-up of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023). In particular, we have determined the critical value of the gas Reynolds number at the onset of the ISW instability mode by varying the inclination angle and the liquid Reynolds number. In § 3, we will introduce the mathematical formulation of our spatio-temporal linear stability analysis (§§ 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3), as well as the employed numerical solution methods and their validation versus benchmark literature data (§ 3.4). Our results are presented in § 4. Therein, § 4.1 is dedicated to identifying the nature of the ISW instability mode, while § 4.2 discusses the effect of different control parameters on the threshold of the ISW mode. In § 4.2, we will compare our linear stability predictions with the new data obtained from our experiments. Appendix A contains first three-dimensional linear stability calculations based on an equivalent two-dimensional formulation obtained in the limit of an unperturbed turbulent viscosity. Appendices B and C contain a more detailed discussion of comparisons with calculations of Vellingiri et al. (Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015) and details regarding saddle-point curves obtained from our spatio-temporal stability calculations.

2. New experiments

In our previous work (Ishimura et al. Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023), we introduced an experimental set-up inspired by the work of Kofman et al. (Reference Kofman, Mergui and Ruyer-Quil2017) that allows to observe the dynamics of surface waves on a gas-sheared falling liquid film (figure 1). It consists of an inclined channel of height,

![]() $H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

, and width,

$H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

, and width,

![]() $W^\star ={27}\,\textrm {cm}$

, formed between two plane glass plates. A falling film of water flows down the bottom (quartz) glass plate and, after travelling through a protected zone of length,

$W^\star ={27}\,\textrm {cm}$

, formed between two plane glass plates. A falling film of water flows down the bottom (quartz) glass plate and, after travelling through a protected zone of length,

![]() $L_0^\star ={36.5}\,\textrm {cm}$

, enters into contact with a turbulent counter-current air flow. This set-up allows to vary three control parameters: the liquid Reynolds number,

$L_0^\star ={36.5}\,\textrm {cm}$

, enters into contact with a turbulent counter-current air flow. This set-up allows to vary three control parameters: the liquid Reynolds number,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

, the gas Reynolds number,

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

, the gas Reynolds number,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

, and the inclination angle with respect to the horizontal,

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

, and the inclination angle with respect to the horizontal,

![]() $\beta$

. Depending on the parameters chosen, the falling liquid film can develop surface waves due to two different instability modes: (i) the long-wave Kapitza mode and (ii) the new interfacial short-wave (ISW) mode. Surface waves can be visualised and recorded through the upper (acrylic) glass plate, and the film thickness can be measured via the confocal chromatic imaging (CCI) technique. Further details are provided by Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) and Mergui et al. (Reference Mergui, Lavalle, Li, Grenier and Dietze2023).

$\beta$

. Depending on the parameters chosen, the falling liquid film can develop surface waves due to two different instability modes: (i) the long-wave Kapitza mode and (ii) the new interfacial short-wave (ISW) mode. Surface waves can be visualised and recorded through the upper (acrylic) glass plate, and the film thickness can be measured via the confocal chromatic imaging (CCI) technique. Further details are provided by Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) and Mergui et al. (Reference Mergui, Lavalle, Li, Grenier and Dietze2023).

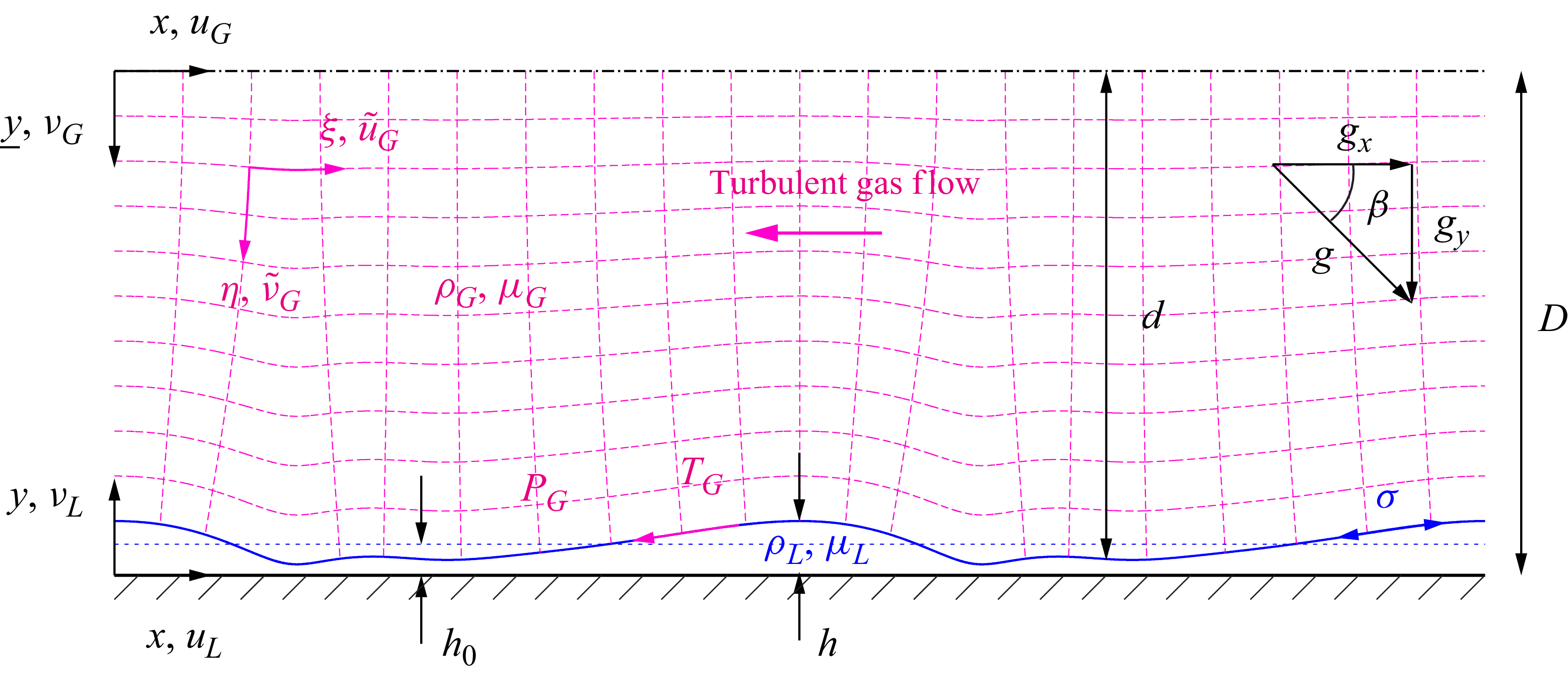

Figure 1. Sketch of our experimental set-up. A falling liquid film of water flows down a glass plate inclined at an angle

![]() $\beta$

and, after transiting through a protected zone, enters in contact with a counter-current turbulent air flow within a rectangular channel of height

$\beta$

and, after transiting through a protected zone, enters in contact with a counter-current turbulent air flow within a rectangular channel of height

![]() $H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

and width

$H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

and width

![]() $W^\star ={270}\,\textrm {mm}$

. The film surface deformation can be captured with two different cameras, a CCD camera with a line sensor (Basler, Sprint spl 4096) and a CMOS camera with a two-dimensional sensor (Basler, ace acA2440-75uc), both capturing a range of

$W^\star ={270}\,\textrm {mm}$

. The film surface deformation can be captured with two different cameras, a CCD camera with a line sensor (Basler, Sprint spl 4096) and a CMOS camera with a two-dimensional sensor (Basler, ace acA2440-75uc), both capturing a range of

![]() $x\approx {50}{-}{80}\,\textrm {cm}$

. The photograph shows upward-travelling ripples emanating from the ISW mode.

$x\approx {50}{-}{80}\,\textrm {cm}$

. The photograph shows upward-travelling ripples emanating from the ISW mode.

Figure 2. Spatio-temporal shadowgraphs obtained from new experiments (

![]() $T\approx {22}\,^\circ\textrm{C}$

) using the set-up of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023). Falling water film sheared by a counter-current turbulent air flow:

$T\approx {22}\,^\circ\textrm{C}$

) using the set-up of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023). Falling water film sheared by a counter-current turbulent air flow:

![]() $H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

. Bright contours track spatio-temporal evolution of wave crests. (a–d)

$H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

. Bright contours track spatio-temporal evolution of wave crests. (a–d)

![]() $\beta ={1}^\circ$

,

$\beta ={1}^\circ$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}=103 \pm3$

. (e–h)

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}=103 \pm3$

. (e–h)

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

,

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}=45.3 \pm1.1$

. (a,e) Quiescent gas. (b,f) First evidence of the ISW mode. (c,g) Upward-travelling (in negative

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}=45.3 \pm1.1$

. (a,e) Quiescent gas. (b,f) First evidence of the ISW mode. (c,g) Upward-travelling (in negative

![]() $x$

-direction) ripples emanating from the ISW mode overpower Kapitza waves. (d,h) Ripples extend over the entire gas-sheared film surface. (b)

$x$

-direction) ripples emanating from the ISW mode overpower Kapitza waves. (d,h) Ripples extend over the entire gas-sheared film surface. (b)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-2540$

, (c)

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-2540$

, (c)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3040$

, (d)

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3040$

, (d)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3515$

; ( f)

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3515$

; ( f)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-5200$

, (g)

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-5200$

, (g)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-6620$

, (h)

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-6620$

, (h)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-6760$

.

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-6760$

.

In the current manuscript, we have used the set-up of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023) to perform additional experiments that focus on characterising the ISW mode. Thereby, we have made the following improvements. First, in addition to a CMOS camera (Basler, ace acA2440-75uc) employed to obtain two-dimensional (2-D) shadowgraphs (see the inset in figure 1), we have employed a CCD camera with a linear sensor (Basler, Sprint spl 4096) to directly obtain highly resolved spatio-temporal recordings of the film surface along the central-axis of the channel across an interval spanning from

![]() $x^\star ={50}\,\textrm {cm}$

to

$x^\star ={50}\,\textrm {cm}$

to

![]() $x^\star ={80}\,\textrm {cm}$

, where

$x^\star ={80}\,\textrm {cm}$

, where

![]() $x$

is the wall-parallel coordinate in streamwise direction (see figure 5). Figure 2 shows typical spatio-temporal shadowgraphs generated from such recordings at constant

$x$

is the wall-parallel coordinate in streamwise direction (see figure 5). Figure 2 shows typical spatio-temporal shadowgraphs generated from such recordings at constant

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

. These highly resolved shadowgraphs allow a more precise detection of the onset of upward-travelling ripples. Second, we have varied the gas Reynolds number more finely, to detect more precisely the onset of the ISW mode from the spatio-temporal diagrams. We have determined the critical value of

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

. These highly resolved shadowgraphs allow a more precise detection of the onset of upward-travelling ripples. Second, we have varied the gas Reynolds number more finely, to detect more precisely the onset of the ISW mode from the spatio-temporal diagrams. We have determined the critical value of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

associated with the onset of the ISW mode for inclination angles ranging from

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

associated with the onset of the ISW mode for inclination angles ranging from

![]() $\beta ={1}^\circ$

to

$\beta ={1}^\circ$

to

![]() $\beta ={8}^\circ$

. In these experiments, surface waves developed naturally via the amplification of ambient noise.

$\beta ={8}^\circ$

. In these experiments, surface waves developed naturally via the amplification of ambient noise.

Two sets of experiments were performed with distilled water and air at ambient temperatures

![]() $T\approx {22}\,^\circ\textrm{C}$

(figures 2 and 21

b) and

$T\approx {22}\,^\circ\textrm{C}$

(figures 2 and 21

b) and

![]() $T\approx {19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

(figures 3 and 4). The density,

$T\approx {19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

(figures 3 and 4). The density,

![]() $\rho _{{L}}$

, and dynamic viscosity,

$\rho _{{L}}$

, and dynamic viscosity,

![]() $\mu _{{L}}$

, of the liquid were measured as

$\mu _{{L}}$

, of the liquid were measured as

![]() $\rho _{{L}}={997.8}\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}$

,

$\rho _{{L}}={997.8}\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}$

,

![]() $\mu _{{L}}={0.97}\,\textrm {mPa s}$

for

$\mu _{{L}}={0.97}\,\textrm {mPa s}$

for

![]() $T={22}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

and

$T={22}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

and

![]() $\rho _{{L}}={998.2}\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}$

,

$\rho _{{L}}={998.2}\,\textrm {kg}\,\textrm {m}^{-3}$

,

![]() $\mu _{{L}}={1.02}\,\textrm {mPa s}$

for

$\mu _{{L}}={1.02}\,\textrm {mPa s}$

for

![]() $T={19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

. The surface tension,

$T={19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

. The surface tension,

![]() $\sigma$

, was measured as

$\sigma$

, was measured as

![]() $\sigma ={72.2}\,\textrm {mN}\,\textrm {m}^{-1}$

for

$\sigma ={72.2}\,\textrm {mN}\,\textrm {m}^{-1}$

for

![]() $T={22}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

and interpolated from Vargaftik, Volkov & Voljak (Reference Vargaftik, Volkov and Voljak1983) as

$T={22}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

and interpolated from Vargaftik, Volkov & Voljak (Reference Vargaftik, Volkov and Voljak1983) as

![]() $\sigma ={72.83}\,\textrm {mN}\,\textrm {m}^{-1}$

for

$\sigma ={72.83}\,\textrm {mN}\,\textrm {m}^{-1}$

for

![]() $T={19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

. The data obtained from these experiments will be compared with our linear stability calculations (see figures 4

b and 21

b). The shadowgraphs in figure 2 correspond to two typical experimental runs, which were used to identify the onset of the ISW mode by increasing the counter-current gas flow rate at fixed

$T={19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

. The data obtained from these experiments will be compared with our linear stability calculations (see figures 4

b and 21

b). The shadowgraphs in figure 2 correspond to two typical experimental runs, which were used to identify the onset of the ISW mode by increasing the counter-current gas flow rate at fixed

![]() $\beta$

and

$\beta$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

. Two series are represented:

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

. Two series are represented:

![]() ${{\textit{Re}}_{{L}}}={103}$

at

${{\textit{Re}}_{{L}}}={103}$

at

![]() $\beta ={1}^\circ$

(figures 2

a–2

d) and

$\beta ={1}^\circ$

(figures 2

a–2

d) and

![]() ${{\textit{Re}}_{{L}}}={45.3}$

at

${{\textit{Re}}_{{L}}}={45.3}$

at

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

(figures 2

e–2

h). Figures 2(a) and 2(e) correspond to the reference configuration of a quiescent gas, where only downward-travelling long waves resulting from the Kapitza instability develop. In figure 2(a), the wave amplitude is too weak to generate shadows that can be detected by our camera. By contrast, in figure 2(e), wave crests associated with Kapitza waves are clearly visible via bright contours that possess a negative slope, i.e. these waves move in positive

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

(figures 2

e–2

h). Figures 2(a) and 2(e) correspond to the reference configuration of a quiescent gas, where only downward-travelling long waves resulting from the Kapitza instability develop. In figure 2(a), the wave amplitude is too weak to generate shadows that can be detected by our camera. By contrast, in figure 2(e), wave crests associated with Kapitza waves are clearly visible via bright contours that possess a negative slope, i.e. these waves move in positive

![]() $x$

-direction with increasing time. Intersections of crest contours evidence noise-driven wave coalescence events. In all other panels, the falling liquid film is subject to a counter-current air flow.

$x$

-direction with increasing time. Intersections of crest contours evidence noise-driven wave coalescence events. In all other panels, the falling liquid film is subject to a counter-current air flow.

Figure 3. Experiments using CMOS camera with two-dimensional sensor (

![]() $T\approx {19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

). Shadowgraphs showing upward-travelling ripples. Conditions similar to figures 2(c) and 2(d):

$T\approx {19.5}\,^\circ \textrm {C}$

). Shadowgraphs showing upward-travelling ripples. Conditions similar to figures 2(c) and 2(d):

![]() $\beta =1^\circ$

,

$\beta =1^\circ$

,

![]() $H^\star$

= 13 mm,

$H^\star$

= 13 mm,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}=100\pm 3$

. (a)

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}=100\pm 3$

. (a)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3040$

(very close to ISW threshold); (b)

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3040$

(very close to ISW threshold); (b)

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3515$

.

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}=-3515$

.

Figure 4. Frequency of upward-travelling ripples. Experiments with CCI probe for conditions according to figure 3(b). (a) Film thickness time trace obtained with 400 Hz acquisition frequency; (b) frequency spectrum obtained by averaging 20 film thickness time-trace signals of 25 s each. The frequency has been normalised with the linearly most-amplified frequency,

![]() $f^\star _{\textit{max}}={7.3}\,\textrm {Hz}$

, obtained from a spatial linear stability calculation, and

$f^\star _{\textit{max}}={7.3}\,\textrm {Hz}$

, obtained from a spatial linear stability calculation, and

![]() $\hat {h}_m$

denotes the amplitude of a Fourier mode with frequency

$\hat {h}_m$

denotes the amplitude of a Fourier mode with frequency

![]() $f^\star _m=m\Delta f^\star$

, where

$f^\star _m=m\Delta f^\star$

, where

![]() $m\in \mathbb{Z}$

and

$m\in \mathbb{Z}$

and

![]() $\Delta f^\star ={0.04}\,\textrm {Hz}$

.

$\Delta f^\star ={0.04}\,\textrm {Hz}$

.

Figure 5. Falling liquid film (subscript

![]() ${L}$

) on an inclined wall subject to a counter-current turbulent gas flow (subscript

${L}$

) on an inclined wall subject to a counter-current turbulent gas flow (subscript

![]() ${G}$

). The flow is confined by an upper wall at

${G}$

). The flow is confined by an upper wall at

![]() $y^\star$

=

$y^\star$

=

![]() $H^\star$

(not shown). In the linear limit, the gas flow is symmetrical about

$H^\star$

(not shown). In the linear limit, the gas flow is symmetrical about

![]() $y^\star$

=

$y^\star$

=

![]() $D^\star$

=

$D^\star$

=

![]() $(H^\star +h_0^\star )/2$

. Magenta dashed lines illustrate the orthogonal curvilinear coordinate system used for the gas, (

$(H^\star +h_0^\star )/2$

. Magenta dashed lines illustrate the orthogonal curvilinear coordinate system used for the gas, (

![]() $\eta$

,

$\eta$

,

![]() $\xi$

), where

$\xi$

), where

![]() $\eta$

=

$\eta$

=

![]() $\underline{y}d_0/d$

. The subscript

$\underline{y}d_0/d$

. The subscript

![]() $0$

denotes the primary flow.

$0$

denotes the primary flow.

We start by discussing figures 2(b)–2(d), which correspond to

![]() $\beta ={1}^\circ$

(see also figure 3, which will be discussed later). In figure 2(b), the value of

$\beta ={1}^\circ$

(see also figure 3, which will be discussed later). In figure 2(b), the value of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

is slightly beyond the threshold of the ISW mode, i.e. the first evidence of upward-travelling ripples is detectable. In particular, wave crest contours with a positive slope are observed in the lower half of figure 2(b) (

${\textit{Re}}_{{G}}$

is slightly beyond the threshold of the ISW mode, i.e. the first evidence of upward-travelling ripples is detectable. In particular, wave crest contours with a positive slope are observed in the lower half of figure 2(b) (

![]() $x^\star \gt {70}\,\textrm {cm}$

), evidencing wave fronts that move in negative

$x^\star \gt {70}\,\textrm {cm}$

), evidencing wave fronts that move in negative

![]() $x$

-direction with increasing time. These upward-travelling ripples coexist with downward-travelling Kapitza waves, as evidenced by the bright contours with positive slope in the top half of the panel. Upon increasing the counter-current gas flow rate further, ripples emanating from the ISW mode progressively invade the domain and eventually overpower the Kapiza waves (figure 2

d,

$x$

-direction with increasing time. These upward-travelling ripples coexist with downward-travelling Kapitza waves, as evidenced by the bright contours with positive slope in the top half of the panel. Upon increasing the counter-current gas flow rate further, ripples emanating from the ISW mode progressively invade the domain and eventually overpower the Kapiza waves (figure 2

d,

![]() ${{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}=-3515$

). This can be understood via figure 11 of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023), where it was shown for the same conditions that the counter-current gas flow exerts a stabilising effect on the Kapitza instability mode, eventually suppressing it at

${{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}=-3515$

). This can be understood via figure 11 of Ishimura et al. (Reference Ishimura, Mergui, Ruyer-Quil and Dietze2023), where it was shown for the same conditions that the counter-current gas flow exerts a stabilising effect on the Kapitza instability mode, eventually suppressing it at

![]() ${{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}=-3400$

. By contrast, the appearance of Kapitza waves between figures 2(a) (aerostatic) and 2(b) (

${{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}=-3400$

. By contrast, the appearance of Kapitza waves between figures 2(a) (aerostatic) and 2(b) (

![]() ${{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}=-2540$

) can be explained by an increased noise level when the falling liquid film is sheared by a turbulent counter-current gas flow.

${{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}=-2540$

) can be explained by an increased noise level when the falling liquid film is sheared by a turbulent counter-current gas flow.

Similar observations are made for the larger inclination angle,

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

(figures 2

f–2

h). However, in this case, Kapitza waves reach a developed nonlinear state within the protected zone of the experimental set-up, before coming into contact with the counter-current gas flow. Due to this, the onset of the ISW instability manifests itself in another way. As shown in figure 2( f), which corresponds to slightly supercritical conditions in terms of the ISW instability, the wave crest contours of the Kapitza waves are distorted by slight kinks, which evolve into positively sloped wave contours associated with upward-travelling ripples as the counter-current gas flow rate is increased (figure 2

g). That the first manifestations of the ISW mode occur on the wave humps of the nonlinear Kapitza waves is due to the higher local confinement of the gas flow there. We will see in § 4.2 that the critical value of

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

(figures 2

f–2

h). However, in this case, Kapitza waves reach a developed nonlinear state within the protected zone of the experimental set-up, before coming into contact with the counter-current gas flow. Due to this, the onset of the ISW instability manifests itself in another way. As shown in figure 2( f), which corresponds to slightly supercritical conditions in terms of the ISW instability, the wave crest contours of the Kapitza waves are distorted by slight kinks, which evolve into positively sloped wave contours associated with upward-travelling ripples as the counter-current gas flow rate is increased (figure 2

g). That the first manifestations of the ISW mode occur on the wave humps of the nonlinear Kapitza waves is due to the higher local confinement of the gas flow there. We will see in § 4.2 that the critical value of

![]() $|{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}|$

for the linear onset of the ISW mode decreases with increasing confinement (figure 19).

$|{{\textit{Re}}_{{G}}}|$

for the linear onset of the ISW mode decreases with increasing confinement (figure 19).

Because the experimental onset of upward-travelling ripples may be observed on an already nonlinear train of Kapitza waves, depending on the set of parameters (

![]() $\beta$

,

$\beta$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

), one should not expect agreement always with the linear onset of the ISW mode determined via our spatio-temporal stability calculations. However, for the conditions used in our experiments, we observe very good agreement (see e.g. figure 21

b), as the amplitude of nonlinear Kapitza waves is rather small compared with the channel height, and, thus, the variation in local relative gas confinement across a Kapitza wave is rather weak. For example, based on CCI measurements, the typical height of a Kapitza wave for the conditions in figure 2( f) at the onset of the ISW mode is

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

), one should not expect agreement always with the linear onset of the ISW mode determined via our spatio-temporal stability calculations. However, for the conditions used in our experiments, we observe very good agreement (see e.g. figure 21

b), as the amplitude of nonlinear Kapitza waves is rather small compared with the channel height, and, thus, the variation in local relative gas confinement across a Kapitza wave is rather weak. For example, based on CCI measurements, the typical height of a Kapitza wave for the conditions in figure 2( f) at the onset of the ISW mode is

![]() $h_{\textit{max}}^\star \approx {1}\,\textrm {mm}$

, and the typical thickness of the residual film in between wave humps is

$h_{\textit{max}}^\star \approx {1}\,\textrm {mm}$

, and the typical thickness of the residual film in between wave humps is

![]() $h_{{res}}^\star \approx {0.3}\,\textrm {mm}$

. Thus, the gas layer thickness,

$h_{{res}}^\star \approx {0.3}\,\textrm {mm}$

. Thus, the gas layer thickness,

![]() $H^\star {-}h^\star$

, varies by only 5 % of the channel height,

$H^\star {-}h^\star$

, varies by only 5 % of the channel height,

![]() $H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

. For larger values of

$H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

. For larger values of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

and/or

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

and/or

![]() $\beta$

, this variation increases, and comparison between experiment and linear stability calculations is no longer appropriate. Consequently, we have only considered

$\beta$

, this variation increases, and comparison between experiment and linear stability calculations is no longer appropriate. Consequently, we have only considered

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

–

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

–

![]() $\beta$

parameter pairs where the variation in local confinement is less than 7 % in the experiments used to validate our linear stability calculations of the ISW instability threshold (figure 21

b).

$\beta$

parameter pairs where the variation in local confinement is less than 7 % in the experiments used to validate our linear stability calculations of the ISW instability threshold (figure 21

b).

The main linear stability calculations presented in the current manuscript are based on a two-dimensional formulation. Thus, the question arises as to whether the upward-travelling ripples produced by the ISW mode are indeed two-dimensional. Figures 3(a) and 3(b) represent two-dimensional shadowgraphs captured with our CMOS camera for the conditions in figures 2(c) and 2(d). A similar snapshot is shown as an inset in figure 1. These experiments, performed at a very low inclination angle,

![]() $\beta ={1}^\circ$

, are favourable to the ISW mode, because Kapitza waves, which are prone to a gas-aided secondary three-dimensional instability mode (Kofman et al. Reference Kofman, Mergui and Ruyer-Qui2014, Reference Kofman, Mergui and Ruyer-Quil2017), entirely disappear upon increasing the counter-current gas flow rate (figure 2

d). Figure 3(a) corresponds to conditions only slightly above the onset of upward-travelling ripples and, thus, the shadows of the wave fronts are quite faint. Nonetheless, it can be observed that the fronts are more or less two-dimensional, even though three-dimensional defects are also visible. The latter become more pronounced in figure 3(b), which corresponds to a larger value of

$\beta ={1}^\circ$

, are favourable to the ISW mode, because Kapitza waves, which are prone to a gas-aided secondary three-dimensional instability mode (Kofman et al. Reference Kofman, Mergui and Ruyer-Qui2014, Reference Kofman, Mergui and Ruyer-Quil2017), entirely disappear upon increasing the counter-current gas flow rate (figure 2

d). Figure 3(a) corresponds to conditions only slightly above the onset of upward-travelling ripples and, thus, the shadows of the wave fronts are quite faint. Nonetheless, it can be observed that the fronts are more or less two-dimensional, even though three-dimensional defects are also visible. The latter become more pronounced in figure 3(b), which corresponds to a larger value of

![]() $|{Re_G}|$

. At present, it is not possible to determine whether the three-dimensional features are due to linear or nonlinear growth mechanisms. Preliminary three-dimensional stability calculations for the larger inclination angle,

$|{Re_G}|$

. At present, it is not possible to determine whether the three-dimensional features are due to linear or nonlinear growth mechanisms. Preliminary three-dimensional stability calculations for the larger inclination angle,

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

, which are presented in Appendix A and discussed in § 3, suggest that the ISW threshold may be slightly lower for three-dimensional perturbations than for two-dimensional ones. However, the shift of the critical gas Reynolds number magnitude observed in these calculations is of the order of 4 %, which is within the error bar of our experiments, and, thus, cannot be resolved experimentally. Further, our preliminary calculations are based on an equivalent two-dimensional formulation that can only be obtained by neglecting the perturbation of the turbulent viscosity and, thus, need to be confirmed with full three-dimensional calculations. These are outside the scope of the current manuscript. Thus, for the time being, and following Vellingiri et al. (Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015) and Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016), we rely on our two-dimensional stability calculations, which are in very good agreement with our experiments, e.g. they accurately predict the threshold of the ISW mode (see figure 21

b, which will be discussed in § 4). Very good agreement is also observed between the dominant frequency of the upward travelling ripples in our experiments and the linearly most-amplified frequency,

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

, which are presented in Appendix A and discussed in § 3, suggest that the ISW threshold may be slightly lower for three-dimensional perturbations than for two-dimensional ones. However, the shift of the critical gas Reynolds number magnitude observed in these calculations is of the order of 4 %, which is within the error bar of our experiments, and, thus, cannot be resolved experimentally. Further, our preliminary calculations are based on an equivalent two-dimensional formulation that can only be obtained by neglecting the perturbation of the turbulent viscosity and, thus, need to be confirmed with full three-dimensional calculations. These are outside the scope of the current manuscript. Thus, for the time being, and following Vellingiri et al. (Reference Vellingiri, Tseluiko and Kalliadasis2015) and Schmidt et al. (Reference Schmidt, Náraigh, Lucquiaud and Valluri2016), we rely on our two-dimensional stability calculations, which are in very good agreement with our experiments, e.g. they accurately predict the threshold of the ISW mode (see figure 21

b, which will be discussed in § 4). Very good agreement is also observed between the dominant frequency of the upward travelling ripples in our experiments and the linearly most-amplified frequency,

![]() $f_{\textit{max}}$

, obtained from a spatial linear stability calculation (as we will show, the ISW mode is upward-convective). Following Valluri et al. (Reference Valluri, Náraigh, Ding and Spelt2010), this is shown in figure 4(b), representing the frequency spectrum of the experimental wave profile represented in figure 4(a) and corresponding to the parameters in figure 3(b), whereby the frequency,

$f_{\textit{max}}$

, obtained from a spatial linear stability calculation (as we will show, the ISW mode is upward-convective). Following Valluri et al. (Reference Valluri, Náraigh, Ding and Spelt2010), this is shown in figure 4(b), representing the frequency spectrum of the experimental wave profile represented in figure 4(a) and corresponding to the parameters in figure 3(b), whereby the frequency,

![]() $f^\star$

, has been normalised with

$f^\star$

, has been normalised with

![]() $f_{\textit{max}}^\star ={7.3}\,\textrm {Hz}$

. The peak of the spectrum is observed at

$f_{\textit{max}}^\star ={7.3}\,\textrm {Hz}$

. The peak of the spectrum is observed at

![]() $f^\star$

/

$f^\star$

/

![]() $f_{\textit{max}}^\star {\approx }1$

.

$f_{\textit{max}}^\star {\approx }1$

.

3. Orr–Sommerfeld spatio-temporal linear stability calculations

We consider the two-dimensional configuration sketched in figure 5. A laminar falling liquid film (subscript L) of thickness,

![]() $h$

, and flow rate (per unit width),

$h$

, and flow rate (per unit width),

![]() $q_{{L}}$

, with constant density,

$q_{{L}}$

, with constant density,

![]() $\rho _{{L}}$

, dynamic viscosity,

$\rho _{{L}}$

, dynamic viscosity,

![]() $\mu _{{L}}$

, and surface tension,

$\mu _{{L}}$

, and surface tension,

![]() $\sigma$

, flows down a plane inclined at an angle,

$\sigma$

, flows down a plane inclined at an angle,

![]() $\beta$

, and is sheared by a turbulent counter-current gas flow (subscript G) of flow rate,

$\beta$

, and is sheared by a turbulent counter-current gas flow (subscript G) of flow rate,

![]() $q_{{G}}$

, with constant density,

$q_{{G}}$

, with constant density,

![]() $\rho _{{G}}$

, and dynamic viscosity,

$\rho _{{G}}$

, and dynamic viscosity,

![]() $\mu _{{G}}$

. Both fluids are considered Newtonian. The gas is confined by an upper wall at

$\mu _{{G}}$

. Both fluids are considered Newtonian. The gas is confined by an upper wall at

![]() $y^\star$

=

$y^\star$

=

![]() $H^\star$

, which is not shown. We assume that the superficial gas velocity,

$H^\star$

, which is not shown. We assume that the superficial gas velocity,

![]() $\mathcal{U}_{{G}}$

=

$\mathcal{U}_{{G}}$

=

![]() $q_{{{G}} 0}^\star$

/

$q_{{{G}} 0}^\star$

/

![]() $H^\star$

, is much greater than the superficial liquid velocity,

$H^\star$

, is much greater than the superficial liquid velocity,

![]() $\mathcal{U}_{{L}}$

=

$\mathcal{U}_{{L}}$

=

![]() $q_{{{L}} 0}^\star$

/

$q_{{{L}} 0}^\star$

/

![]() $H^\star$

, where, and throughout the manuscript, the star symbol and calligraphic typeface denote dimensional quantities, and the subscript

$H^\star$

, where, and throughout the manuscript, the star symbol and calligraphic typeface denote dimensional quantities, and the subscript

![]() $0$

denotes the primary flow. Thus, the liquid–gas interface is considered immobile and rigid from the point of view of the gas, and the gas-side problem can be solved independently for a given film height profile,

$0$

denotes the primary flow. Thus, the liquid–gas interface is considered immobile and rigid from the point of view of the gas, and the gas-side problem can be solved independently for a given film height profile,

![]() $h(x,t)$

. Due to this assumption, and because we are only interested in the linear response of the system, the gas flow can be considered symmetrical with respect to

$h(x,t)$

. Due to this assumption, and because we are only interested in the linear response of the system, the gas flow can be considered symmetrical with respect to

![]() $y^\star$

=

$y^\star$

=

![]() $D^\star$

=

$D^\star$

=

![]() $(H^\star +h_0^\star )/2$

, and only the bottom half of the gas layer needs to be represented. The effect of the gas on the liquid film is represented via the tangential and normal gas stresses,

$(H^\star +h_0^\star )/2$

, and only the bottom half of the gas layer needs to be represented. The effect of the gas on the liquid film is represented via the tangential and normal gas stresses,

![]() $T_{{G}}$

and

$T_{{G}}$

and

![]() $P_{{G}}$

, acting at the liquid–gas interface. Thus, we neglect normal viscous gas stresses. Figure 6 represents typical velocity profiles of the primary flow, which will be further discussed in §§ 3.1 and 3.2.

$P_{{G}}$

, acting at the liquid–gas interface. Thus, we neglect normal viscous gas stresses. Figure 6 represents typical velocity profiles of the primary flow, which will be further discussed in §§ 3.1 and 3.2.

Figure 6. Primary-flow streamwise velocity profiles in the (a) liquid and (b) gas for

![]() $H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

,

$H^\star ={13}\,\textrm {mm}$

,

![]() $\beta ={5}^\circ$

,

$\beta ={5}^\circ$

,

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

= 43.1,

${\textit{Re}}_{{L}}$

= 43.1,

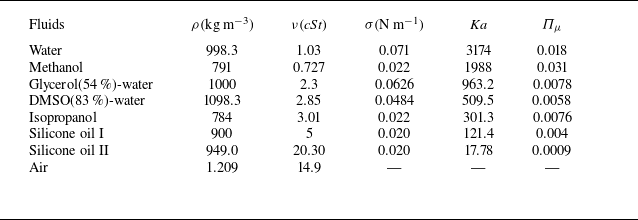

![]() $T_{{{G}}0}^\star ={478}\,\textrm {N}\,\textrm {m}^{-2}$