Introduction

The importance of input for language learning has been on the research agenda for several decades, ever since Krashen (Reference Krashen1982) formulated the monitor model and the input hypothesis. Usage-based theories of language learning have argued that exposure to and experience with language are essential for language learning to take place (Bybee & Hopper, Reference Bybee and Hopper2001; Ellis, Reference Ellis2002). In the context of L2 English learning, exposure to the target language is not only present or instigated through formal instruction but, as English is perceived as the lingua franca in large parts of the world (Dewey, Reference Dewey2007), exposure to English also takes place outside the classroom in many L2 English learning contexts (e.g. through social media, watching television or listening to music). This type of exposure to English has been referred to as extramural English (EE, Sundqvist, Reference Sundqvist2009). Many studies have shown that EE is an important predictor of L2 English knowledge and skills even for young and adolescent learners (e.g. Lindgren & Muñoz, Reference Lindgren and Muñoz2013; Puimège & Peters, Reference Puimège and Peters2019; Sylvèn & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2012). Some studies found that learners not only pick up some of this input receptively but that some learners are also able to use language productively, even before or at the very start of formal English instruction. Studies have looked into productive vocabulary knowledge (Bollansée et al., Reference Bollansée, Puimège and Peters2020), writing (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2023), and speaking skills (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020; Lefever, Reference Lefever2010) before or at the start of L2 English instruction. These studies have consistently shown large differences in learning gains between learners and thus different initial conditions in the early stages or at the start of L2 English classroom instruction. Longitudinal studies with adolescent learners (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009; De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2025; De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021; Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017) have shown that prior knowledge at the start of the study systematically predicted learners’ L2 English vocabulary knowledge (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2025; De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021), receptive skills (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009; Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017), and writing (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009). For speaking, De Wilde et al. (Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021) found that prior L2 knowledge measured at the start of the study, and before the start of formal L2 English instruction, explained 58% of the variability in speaking scores two years later. The authors further found that, even though all learners made considerable progress, there was evidence that more learning occurred in learners who were less proficient. It has not been investigated, however, how these differences in initial proficiency might impact the learning process.

In the present study I aim to uncover whether and how adolescent learners’ prior L2 English knowledge gained through extramural input impacts the learning process by looking into 12 learners’ L2 English speaking development throughout the first year of formal English instruction. I will explore the development of various aspects of lexical and syntactic complexity over time and whether and how prior L2 knowledge has an impact on the developmental process.

Complex Dynamic Systems Theory and the role of initial proficiency in L2 development

An approach in which language development and the learning process have a central place is Complex Dynamic Systems Theory (CDST). In this approach to language learning and development, language is seen as a complex system which is driven by internal and external resources which are interrelated. Furthermore, development is considered highly individual and dependent on the initial conditions.

One of the important characteristics of dynamic systems is their dependence on initial conditions which are often seen as precursors for language development. De Bot et al. (Reference De Bot, Lowie and Verspoor2007) posited that an event which occurs in early childhood (e.g. a middle-ear infection) could have a lasting effect on second language acquisition. Larsen-Freeman (Reference Larsen-Freeman1997: 144) wrote that ‘a slight change in initial conditions can have vast implications for future behavior’. Children’s engagement with activities in which they are exposed to English (e.g. gaming or watching television) and the differences in L2 prior knowledge that result from it could have such an effect (cf. De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021).

Below, I will give an overview of previous studies which have investigated the role of initial proficiency in the L2 learning process and more specifically in the development of L2 speaking. Then, I will consider how complexity can be defined and how it can be operationalized in second language speech with low proficiency learners.

The development of L2 speaking skills

In a book chapter which discusses process-oriented research on the development of L2 speaking from a CDST-perspective, Lowie and Verspoor (Reference Lowie, Verspoor, Derwing, Munro and Thomson2022) point towards the fact that only a limited number of studies have investigated L2 speaking. The authors give several explanations for this scarcity. First, working with spoken data is rather complicated as the data need to be transcribed before they can be analyzed. Second, they also point towards another reason, namely the fact that many different factors affect speaking which leads to rather messy data with high levels of inter- and intraindividual variation. Despite these challenges, some studies did investigate L2 speaking development.

In Reference Larsen-Freeman2006, Larsen-Freeman published a study in which she examined the development of various aspects in the oral and written production of five adult, high-intermediate Chinese learners of English who were in an English course in the United States which used a communicative grammar textbook and asked learners to engage with English outside the classroom on a daily basis (e.g. through reading or watching television). The participants in the study did four tasks over a period of six months. Every six weeks, they were asked to tell a story about a past episode they wanted to share. Even though the spoken data were recorded and transcribed, the paper mainly reported on the written data and the oral narratives were only used for qualitative analysis. The qualitative analysis showed the value of looking at the level of the individual learner over time. In the present study both idiosyncrasies of individual learners’ development and general principles of change will be studied.

Quantitative research investigating L2 speaking development

More recently, several studies have been conducted which investigated L2 speaking development from a quantitative perspective. Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Verspoor and Vahtrick2015) studied development in speaking and writing of English as a foreign language (EFL) in identical twins. The twins were 15-year-old girls, growing up in Taiwan. They had already had 10 years of English instruction, but they were mainly exposed to written input before the start of the study. The participants did three tasks per week until the researchers had gathered 100 speaking samples per participant. The speaking topics were taken from TOEFL tests and could, for example, ask learners to give their opinion about a topic. The study’s main focus was on changes and shifts in the learners’ syntactic complexity development. There was a large variability in the spoken data within but also between the learners, even though they were identical twins. The study showed that two very similar learners followed different developmental paths.

Lowie et al. (Reference Lowie, Van Dijk, Chan and Verspoor2017) further examined data from these twins. They looked into the development of the girls’ syntactic complexity (mean length of T-unit) and lexical diversity (VocD) in spoken and written texts. The authors investigated whether there were differences between the participants’ learning trajectory and whether there was a change in the two aspects of complexity over time. Monte Carlo analyses for the spoken data showed that syntactic development was generally stable, but when it came to development of lexical diversity a different pattern emerged with clear differences between the girls. The girl with the highest starting proficiency seemed to stabilize over time, whereas the girl who initially had a lower proficiency showed a clear increase over time. This could partly be because she was able to perform the task at the start of the study and thus there was less room for improvement. Overall, the study showed clear differences in the girls’ L2 development.

Yu and Lowie (Reference Yu and Lowie2019) looked into the development of L2 English speaking of 10 Chinese learners who were in the first year of university. Prior to their English course at university, they had received 10 years of EFL instruction. They seldom had the opportunity to use English in daily life and had never visited an English-speaking country. Improvement in speaking proficiency over the course of the semester was investigated with all ten students. The researchers also focused on development of spoken accuracy and complexity for two students. The participants did a speaking task every week for 12 consecutive weeks. Topics were selected from the IELTS speaking test. Each week, participants were asked to talk about a topic related to social issues, locations or places, life experience, and figure images. The complexity variables under investigation were mean length of AS-unit (MLA, a measure of syntactic complexity), and Voc D (a measure of lexical diversity). The authors found that there was an increase in MLA between the first and the last measurement. To investigate the learning trajectory, the authors used moving min-max graphs and Monte Carlo simulations. At the individual level, the authors found clear differences between learners’ proficiency and high variability in the individual learning trajectories. The two learners came from different provinces in China and had received a different type of English instruction. One learner received instruction in the four skills, whereas the other learner had never had speaking or listening courses. Results showed this prior knowledge, gained through previous EFL classes, continued to play a large role which is in line with the idea that initial state is an important aspect of a complex dynamic system (De Bot et al., Reference De Bot, Lowie and Verspoor2007; Larsen-Freeman, Reference Larsen-Freeman1997).

Pfenninger (Reference Pfenninger2020) looked at young learners’ speaking development from a CDST-perspective. The author investigated longitudinal L2 speaking development of 91 young learners (ages 5 to 13) who were in different types of CLIL-programs. The speaking task was a retelling task in which learners were asked to recount the plot of a silent video four times a year. In order to uncover periods of significant growth in the participants’ learning trajectories the author investigated various aspects of complexity, accuracy, and fluency. The measures that were chosen for this study were rather crude measures (mean length of utterance, clause ratio, and measure of textual lexical diversity). Generalized additive mixed models (GAMMs) were used to model the learning trajectory and highlight significant changes in development. Lexical richness developed more in children who started CLIL at an earlier age but there was no impact of starting age of CLIL on syntactic oral complexity. At the level of the individual learner, the results showed that variability and growth increased with time (and length of instruction) which seemed to suggest that a certain threshold of language proficiency needs to be present before much variability can occur.

Crossley et al. (Reference Crossley, Salsbury and McNamara2010) explored the development of lexical proficiency and growth of lexical networks in a longitudinal study with low-level, adult learners of English who did biweekly interviews for one year. The researchers found rapid growth in lexical networks in the first four months which then seemed to stabilize. Follow-up analyses showed that after this initial, rapid growth learners extended the core meanings of polysemous words.

Longitudinal studies investigating speaking development have thus shown that learning trajectories can differ according to learners’ initial proficiency and the input they have received (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021; Pfenninger, Reference Pfenninger2020; Yu & Lowie, Reference Yu and Lowie2019). The studies further suggest that beginner learners might need to reach a threshold or basic starting proficiency before much change can be observed (Pfenninger, Reference Pfenninger2020). At the same time, studies have shown a stabilization after phases of initial and rapid growth (Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Salsbury and McNamara2010; Lowie et al., Reference Lowie, Van Dijk, Chan and Verspoor2017)

Measuring linguistic complexity in L2 English

The studies that have been discussed above all investigated the development of lexical and/or syntactic complexity in L2 speaking. To be able to make an informed choice about which measures are suitable to be used in this study I will first look into a proposed framework of complexity and then consider studies which have focused on aspects of complexity in research with young and adolescent learners.

The construct of complexity has proven to be problematic and difficult to define (Norris & Ortga, Reference Norris and Ortega2009; Pallotti, Reference Pallotti2009). In Reference Bulté, Housen, Housen, Kuiken and Vedder2012, Bulté and Housen proposed a taxonomy of complexity constructs which was meant to give researchers a framework to start from. They made a distinction between relative complexity, which is complexity in relation to language users and which is also called cognitive complexity, and absolute complexity, which is the number of components a language feature or system consists of and the number of connections between these components. Inherent or absolute complexity can be subdivided into three components: propositional complexity, discourse-interactional complexity, and linguistic complexity. In L2 research the notion of linguistic complexity has received a lot of attention. Recently, Bulté et al. (Reference Bulté, Housen and Pallotti2025) proposed an update of this framework. The authors further discuss the distinction between complexity, which refers to structural complexity, and difficulty, which refers to cognitive complexity or the difficulty with which language features are processed. They suggest using the terms complexity and difficulty rather than the umbrella term complexity to distinguish between the two concepts. Previous studies which looked into the development of L2 speaking from a CDST-perspective have mainly investigated aspects of syntactic and/or lexical complexity and difficulty. Below, I give an overview of studies that have investigated language development in young and often beginner learners of English and discuss which measures are suitable when investigating L2 development in this population.

Investigating L2 development in young and adolescent learners

Only one of the studies discussed above investigated L2 learning with young learners who were in the early stages of L2 English learning (Pfenninger, Reference Pfenninger2020; cf. supra). A few other studies have investigated L2 development in adolescent learners’ L2 English. These studies mainly looked at written production.

Verspoor et al. (Reference Verspoor, Schmid and Xu2012) investigated adolescent learners’ L2 English writing in a Dutch secondary school. The participants were in the first (12 to 13 years old) or third year (14 to 15 years old) of secondary education. They were asked to write about a familiar topic that did not require specialized language (their new school, a previous vacation). The authors studied various aspects of complexity and accuracy in 489 adolescent learners’ written texts and found that the best predictors for learners’ proficiency were broad measures such as sentence length, Guiraud index, use of chunks, and use of present and past tenses. In the transition from proficiency level 1 to proficiency level 2 there were mainly lexical changes; between levels 2 and 3 the authors mainly observed syntactic changes, and between levels 3 and 4 both lexical and syntactic changes occurred.

Kyle and colleagues (Reference Kyle, Crossley and Jarvis2021) investigated adolescent Dutch learners’ longitudinal writing development. They explored the role of syntactic complexity and syntactic sophistication in the writing development of 9 L2 English learners who were 12 to 13 years old at the start of the study and who wrote six essays about a topic that was relevant to them and did not require specialized language. The study showed that there was significant development in two aspects of syntactic complexity (mean length of T-unit and the proportion of clauses in a text that are dependent clauses) and two aspects of syntactic sophistication (main verb frequency and verb-VAC frequency).

Finally, De Wilde (Reference De Wilde2023) studied lexical characteristics of adolescent learners’ writing (n = 3168) who were at the very start of formal instruction (11–13 years old). The participants in the study did a picture narration task. Like Verspoor and colleagues (Reference Verspoor, Schmid and Xu2012), the author found that proficiency scores were mainly impacted by broad characteristics such as lexical diversity (measured with MTLD), frequency, and lexical productivity (word count). It remains to be seen whether these aspects also play a role in the development of adolescent L2 English learners’ oral development.

The studies that were done with young learners selected different types of tasks (retelling tasks, picture narration tasks, or descriptive/informative tasks). Even though previous studies have shown effects of task type in L2 development (Alexopoulou et al., Reference Alexopoulou, Michel, Murakami and Meurers2017) the studies with young and adolescent learners have all shown that overall broad measures were most suitable to investigate L2 development.

Aims and RQs

The aim of this study is to explore longitudinal development of lexical and syntactic complexity in adolescent learners’ L2 English speaking development and to investigate the role of initial proficiency. I therefore set up a longitudinal microdevelopment study. Spoken data was collected every week throughout the first year of English classes (cf. Method section).

In the study I will address the following research questions:

-

- RQ1: How do various aspects of lexical and syntactic complexity develop in adolescent L2 learners’ spoken English?

-

- RQ2: What is the relationship between L2 learners’ initial proficiency and complexity in L2 English speaking?

-

- RQ3: How does initial proficiency impact complexity development of adolescent learners’ L2 English speaking during the first year of formal L2 English instruction?

In line with previous research on the development of L2 speaking, I hypothesize that learners will follow an individual trajectory in which various aspects of complexity do not necessarily develop in a similar manner (cf. Chan et al., Reference Chan, Verspoor and Vahtrick2015; Lowie et al., Reference Lowie, Van Dijk, Chan and Verspoor2017; Yu & Lowie, Reference Yu and Lowie2019).

I further hypothesize that learners’ initial proficiency will be an important factor in the complexity of their spoken language. A significant relationship between proficiency and linguistic complexity has been found in studies investigating L2 writing with learners who were similar to the participants of our study, especially with regard to broad measures such as lexical diversity (cf. Verspoor et al., Reference Verspoor, Schmid and Xu2012; De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2023). Furthermore, studies looking into L2 English learning through out-of-school exposure have found that there are large differences in prior knowledge between learners and that prior knowledge was highly predictive of speaking skills two years later (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021; Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017).

Finally, we will not only look at the impact of initial proficiency on learners’ L2 speaking but also investigate how their initial proficiency impacts their learning trajectory. Based on previous studies I hypothesize that initial proficiency will impact the learning trajectory and learners with different L2 prior knowledge will exhibit different amounts and patterns of growth. Crossley et al. (Reference Crossley, Salsbury and McNamara2010) found rapid growth with beginners but a stabilization of vocabulary size after a few months. Lowie et al. (Reference Lowie, Van Dijk, Chan and Verspoor2017) found that for lexical diversity the learner with the highest proficiency seemed to stabilize over time, whereas the other learner showed an increase in lexical diversity throughout the study. Yu and Lowie (Reference Yu and Lowie2019) compared two participants and found that their developmental trajectory was influenced by their initial proficiency, which was caused by differences in the input they had received. Finally, Pfenninger (Reference Pfenninger2020) found that with beginners and at the level of the individual learner, variability and growth increased over time which seemed to suggest that a certain threshold of language proficiency has to be reached before much change can be observed. This means that absolute beginners might need some time before learning becomes visible. When this happens, we expect a period of fast and significant growth. Learners with high initial proficiency might show slower growth and/or stabilize over time.

Method

Research context

The study was conducted with adolescent L2 English learners who were living in Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. Belgium has three official languages: Dutch, French, and German. German is spoken only by a small group of people who are living close to the border with Germany. Dutch and French are spoken in Flanders and Wallonia, respectively, and in the bilingual capital region of Brussels. Therefore, it has been decided by the Flemish government that the first foreign language to be taught in Flemish schools is French rather than English. English lessons typically start in the first and sometimes even in the second year of secondary school when learners are 12 to 13 years old. However, as previously mentioned, exposure to English outside the classroom typically starts a lot sooner than that and quite a few learners’ English knowledge is higher than their knowledge of French (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Noreillie, Heylen, Bulté and Desmet2019; De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2022). This leads to a situation in which many learners have already acquired some English before the start of English classes but, since not all learners have engaged with English outside of school in a similar manner, there typically are large individual differences between learners’ proficiency at the onset of formal L2 English lessons.

Participants

The participants in this study were 12 L2 English learners who were in the first year of secondary school. They were all in the same school and class. They received two hours of formal English instruction per week from a trained English teacher. The lessons focused on the four language skills and the knowledge necessary to develop these skills. The teacher followed the national curriculum objectives which state that learners should have a CEFR A2-level at the end of the second year of secondary school. The participants were a subgroup from a larger microdevelopment study in which 63 adolescent learners participated every week for an entire school year (De Wilde & Lowie, Reference De Wilde and Lowie2025). These twelve learners were selected because they were all in a school which offered formal English lessons in the first year of secondary school and they were followed from the start of the lessons until the end of their first year of formal L2 English instruction (30 data collection points). The class consisted of 21 learners. The twelve learners in the present study were the ones who participated in the study very regularly (between 25 and 30 times per participant). The learners’ L2 English speaking skills were tested weekly over 10 months. In total, there were 30 weeks when data were collected. No data were collected during holidays or exams weeks. The group consisted of seven boys and five girls. Two girls (participants S1 and S2) were monozygotic twins. Nine participants were 12 years old, two participants were 11 years old, and one participant was 13 years old. Similar to previous studies in this context, De Wilde and Lowie (Reference De Wilde and Lowie2025) showed that some learners frequently engaged with English outside the classroom but that there were large differences in L2 English engagement between individual learners.

Learner corpus

To map individual learners’ development, a longitudinal study with dense measurements was conducted. I selected tasks that were suitable for this age group and proficiency level. Kyle and Crossley (Reference Kyle and Crossley2018) cautioned researchers about possible effects of task type. Therefore, learners each week did two different speaking tasks: a picture narration task and a task in which learners received an open question and were asked to talk about a topic (e.g. their friends, their school, a surprise party). The picture narration tasks were sample tasks from Cambridge English for Young Learners tests, and the questions were taken from sample tasks from the Pearson Test of English Young Learners. Fifteen different prompts per task type were selected that were suitable for the learners. The tasks can be found on osf.io (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FZCN9). After 15 weeks, the learners started again with the task from week 1. We should keep in mind that there might be a possible learning effect which stems from repeating the task type and/or the exact same task (cf. Nitta & Baba, Reference Nitta, Baba and Bygate2018) but this is difficult to avoid in longitudinal studies. The learners received the instructions from the researcher or the teacher during class. The learners then left the classroom to do the speaking task in a quiet room where they recorded themselves with their mobile phones and sent the recordings to the researcher. There was no preparation time, and they went back to the classroom immediately after the activity. Afterwards all recordings were scored, transcribed, and cleaned by two researchers. Each week learners received an overall proficiency score (minimum score = 0, maximum score = 20) that was assigned using a rubric taking grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and interactive communication into account. The rubric can be found on osf.io (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FZCN9). All tasks were scored by the same rater. A second rater scored 65% of the tasks a second time. The interrater agreement between the two raters was very high (r = .97). The speaking score was communicated to the teacher who could use this information when designing lessons but not to the learners since some learners were real beginners and we did not want to discourage them when the scores were low.

In order to be able to calculate fine-grained measures, I followed the procedure adopted by Chan et al. (Reference Chan, Verspoor and Vahtrick2015) and Kyle et al. (Reference Kyle, Sung, Eguchi and Zenker2024). Filled pauses, disfluencies, and utterances that did not involve linguistic meaning (e.g. laughter) were deleted. The texts were preprocessed for automatic analysis by adding punctuation based on clausal constructions, intonation, and pauses in the speech. Clausal constructions were considered as one segment in order to be able to do an automatic analysis. As the participants were beginner learners of English, some of the tasks contained Dutch words. These were manually deleted by the researcher. The text length varied from 0 to 145 English words after cleaning. The transcriptions were double-checked by a researcher before the automatic analysis. The corpus was then automatically analyzed with various NLP-tools (cf. infra).

Complexity measures

Based on previous CDST-studies and the taxonomy of complexity which was proposed by Bulté et al. (Reference Bulté, Housen and Pallotti2025), I decided to look into five measures capturing linguistic development. I chose broad measures as these measures have proven to be impactful in the prediction of proficiency and/or development at beginner to intermediate levels of proficiency with adolescent L2 learners. Two syntactic measures were chosen: length of T-unit (MLT), a measure of syntactic complexity, and verb-VAC frequency, a component measure of syntactic sophistication (Kyle, Reference Kyle2016). In research on oral development, researchers often work with AS-units rather than T-units but as I added punctuation in the transcriptions because I wanted to do an automatic analysis, I opted for the equivalent measure in writing that can be analyzed automatically, i.e. T-unit. Both syntactic measures (MLT and verb-VAC frequency) have been shown to play a significant role in adolescent learners’ writing (Kyle et al., Reference Kyle, Crossley and Verspoor2021). In this study I wanted to investigate whether they also play a role in speaking development. Both measures were calculated with the Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Syntactic Sophistication and Complexity (TAASSC, Kyle, Reference Kyle2016). The other measures under investigation were lexical measures. The first lexical measure, MTLD, measures lexical diversity. I chose MTLD to investigate lexical diversity as it can be used with short, spoken texts (Kyle et al., Reference Kyle, Sung, Eguchi and Zenker2024; Zenker & Kyle, Reference Zenker and Kyle2021). MTLD was calculated with the Tool for the Automatic Analysis of Lexical Diversity (TAALED, Kyle et al., Reference Kyle, Crossley and Verspoor2021). I also included a measure of lexical sophistication. As most studies looking into lexical sophistication have focused on word frequency, I also used a frequency measure in this study. Subtlex-US frequency was chosen as it has proven to be an adequate measure for this context and age group (e.g. De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2023). Mean log frequencies for all words in the text (content and function words) were calculated with the Tool for Automatic Analysis of Lexical Sophistication (TAALES; Kyle et al., Reference Kyle, Crossley and Berger2018). Finally, I also added English word count after cleaning as a measure of lexical productivity. Even though this is not a complexity measure, previous studies have shown that lexical productivity has a large impact on the assessment of learners’ overall proficiency development, especially with beginners for whom finding the correct English words might be a challenge (Bulté & Housen, Reference Bulté and Housen2014; De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2023).

Analysis

To be able to answer the research questions which addressed the development over time and the role of initial proficiency (RQ1 and RQ2), I fit GAMMs. As previous research (Kyle & Crossley, Reference Kyle and Crossley2018; Nitta & Baba, Reference Nitta, Baba and Bygate2018) has found that task type and task (repetition) can impact the results, I also took these variables into account in the analyses. GAMMs consider iterative learning and variability in their algorithm and are therefore particularly suited to look into individual variation and nonlinear change over time (Murakami, Reference Murakami2016; Pfenninger Reference Pfenninger2020; Winter & Wieling, Reference Winter and Wieling2016). Apart from the group trajectories, I also fit each participant’s individual learning trajectory (per individual, per complexity measure, and per task type) to be able to answer RQ1 and RQ3. The analyses contained no interactions. Adding an interaction would make the model more complicated, difficult to interpret, and would increase the risk of overfitting. Therefore, I first looked at the development over time (to answer RQ1), then at the impact of initial proficiency on linguistic measures (RQ2), and then combined both, ‘how does initial proficiency impact development over time’ by looking at individual learners’ trajectories rather than adding an interaction term. All variables were z-centered before the analyses. I used the mgcv (Wood & Wood, Reference Wood and Wood2015), gratia (Simpson & Singmann, Reference Simpson and Singmann2018), and ggplot2 (Wickham, Reference Wickham2011) packages in R version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023). To uncover periods of significant change in individual learners’ trajectories, I followed the procedure adopted by Pfenninger (Reference Pfenninger2020) and Kliesch and Pfenninger (Reference Kliesch and Pfenninger2021), who computed the first derivatives of the fitted trend for each task and participant. The first derivative tells us how fast a learner is improving or declining. Periods where zero is not included in the confidence intervals show important, significant periods of change as we can be confident about the observed changes. All data and code can be found on osf.io (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FZCN9).

Results

Complexity development over time

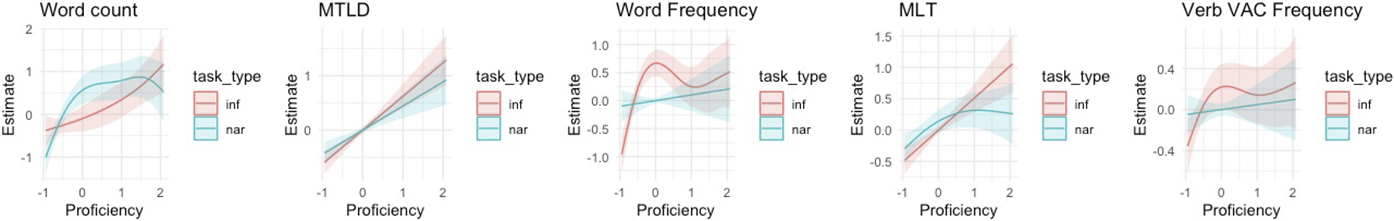

I first calculated correlations between the different L2 measures. These were weak to moderate (ranging from .12 to .47, see Table 1 in the Appendix), showing that the measures captured different aspects of L2 development. To investigate how various aspects of lexical and syntactic complexity developed over time, I modeled a GAMM for each lexical and syntactic variable using the mgcv package in R. I modeled the effect of each variable over time and allowed this variable to be nonlinear. Smooths are linear when the edf-value (effective degrees of freedom) is 1 and nonlinear when the edf-value is higher than 1. I added task type (narrative or informative) as a by-variable to be able to capture possible effects of task type over time. I also added two random effects, one random effect which allowed individual variability, both at the start of the study and over time, and another random effect which accounted for possible effects of specific tasks. Figure 1 shows the development over time per task type for each complexity variable. R-code and model summaries per complexity measure can be found in the appendix.

Figure 1. Development over time for each complexity variable.

The results showed a significant growth over time for lexical productivity (word count). The model showed linear growth for the informative task (edf = 1) and nonlinear growth for the narrative task (edf = 1.47). The development of lexical diversity (MTLD) was linear for both task types (edf = 1), significant for the informative task, and nonsignificant for the narrative task. The development of lexical sophistication (frequency) was linear (edf = 1), nonsignificant, and highly similar for both task types. There was a linear (edf = 1), significant development of syntactic complexity (MLT) in the informative tasks but a nonlinear (edf = 1.44), nonsignificant development in the narrative tasks. Finally, verb-VAC frequency significantly and linearly (edf = 1) increased over time for the informative tasks, whereas there was no significant increase in the narrative tasks. The models showed significant differences between individuals for all measures and a significant random effect for task for all measures except for word frequency.

I then modeled individual trajectories per task type to get more insight into the differences between individuals. Figures 2 to 6 show trajectories over time and periods of significant growth for individual learners. The individual trajectories illustrate the large differences between individual learners. The results furthermore showed that the shape of the learning trajectories was also highly individual. The green dots represent periods of significant growth (increase or decrease), whereas the red dots represent periods in which there is no significant growth. Overall, about half of the learners produced longer and more diverse texts toward the end of the study (Figures 2a, 2b, 3a, and 3b). For the narrative tasks, little change was observed for learners who were already able to produce relatively long texts at the start of the study, and learner S1 who seemed to produce very short texts throughout the study. For the informative texts, again about half of the learners were able to produce longer and more diverse texts. Some participants showed a development in terms of lexical sophistication (Figures 4a and 4b). Most of these learners produced more frequent words over time. There was one exception (narrative tasks, participant S15) but this participant was an absolute beginner and often hardly spoke any English which might explain the shape of the curve. Fewer learners exhibited significant growth for syntactic complexity (Figures 5a and 5b) and change only took place in the narrative tasks. Finally, hardly any significant changes were observed in syntactic sophistication over time (Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 2. Development of lexical productivity per individual and task type. (a) Narrative tasks; (b) informative tasks.

Figure 3. Development of lexical diversity per individual and task type. (a) Narrative tasks; (b) informative tasks.

Figure 4. Development of lexical sophistication per individual and task type. (a) Narrative tasks; (b) informative tasks.

Figure 5. Development of syntactic complexity per individual and task type. (a) Narrative tasks; (b) informative tasks.

Figure 6. Development of syntactic sophistication per individual and task type. (a) Narrative tasks; (b) informative tasks.

The relationship between initial proficiency and complexity

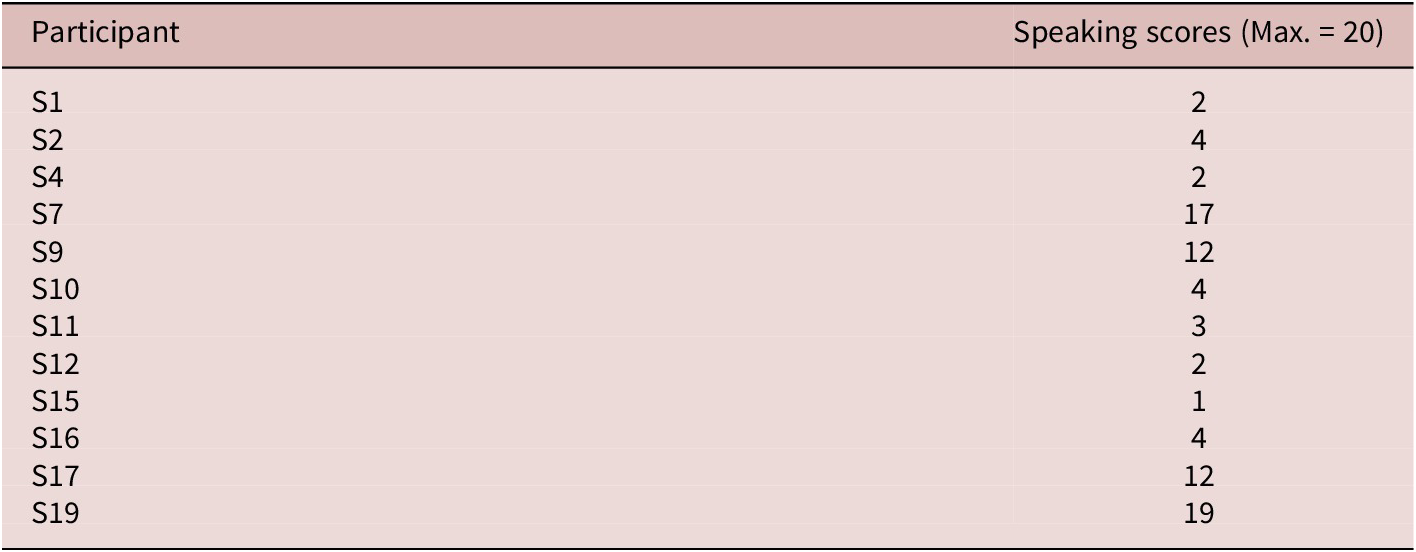

In order to be able to answer RQ2 about the relationship between initial proficiency and complexity in adolescent learners’ L2 English speaking, I added initial proficiency in the GAMM models (see Appendix for R code). The holistic speaking scores learners obtained in week 1 were added as the participants’ initial proficiency score. The maximum score that could be obtained was 20. Learners’ scores ranged from 1 to 19. The mean was 6.64, the median was 4 and the standard deviation was 6.38. Table 1 gives an overview of the holistic speaking scores in week 1 for all 12 participants.

Table 1. Holistic speaking scores in week 1 per participant

Figure 7 and Tables 7–11 in the Appendix show how each complexity variable varied according to the learners’ initial proficiency. The results showed that complexity scores differed according to learners’ initial proficiency level and the analysis further showed differences by task type. The models in which initial proficiency was added all had a better fit than the models without initial proficiency. Lexical productivity was affected by initial proficiency in a nonlinear and significant manner for both task types (edf informative tasks = 1.70, edf narrative tasks = 3.36). Word count seemed to increase steeply and then leveled off for the narrative tasks, whereas it showed an increase throughout proficiency levels for the informative task. Lexical diversity increased linearly (edf = 1) and significantly across proficiency levels. There seemed to be no clear changes in frequency for the narrative tasks (edf = 1) but there does seem to be a nonlinear (edf = 3.53) and significant relationship with word frequency scores in the informative task. Mean length of T-unit significantly increased across proficiency levels for the informative task (edf = 1) but not for the narrative task, which showed a nonlinear trajectory (edf = 1.99) with no significant effect for initial proficiency. No significant effects were found for verb VAC-frequency and this final model only slightly improved when initial proficiency was added (edf informative tasks = 2.68, edf narrative tasks = 1).

Figure 7. Estimated scores for each complexity variable by proficiency.

Initial proficiency and the learning trajectory

To answer RQ3, about the impact of initial proficiency on longitudinal complexity development I inspected the individual learning trajectories (Figures 2–6) while also considering learners’ holistic speaking scores in week 1 (cf. Table 1). One learner with a very low initial proficiency (S1) did not go through any periods of significant growth. Another learner with a very low initial proficiency (S15) only showed periods of significant growth in the learning trajectory for the narrative speaking task. Furthermore, this growth was observed towards the end of the study. When looking into the trajectories of learners who had some L2 prior knowledge (e.g. S2, S10, S11, S16) periods of growth can be observed in all learners, especially for the lexical measures word count and MTLD. For the four learners with the highest initial proficiency (S7, S9, S17, S19) hardly any significant growth in linguistic complexity was observed throughout the study.

Overall, the study showed growth over time for all measures except lexical sophistication at the group level. The growth was most pronounced in the informative task. The analyses further showed that L2 speaking was significantly impacted by learners’ initial proficiency for all measures except syntactic sophistication. More proficient learners produced longer, more diverse texts which contained more high-frequency words and longer sentences. The results also showed large differences between individual learners. When looking at development over time for learners with a different starting proficiency, I observed that absolute beginners showed no growth throughout the study or only exhibited signs of growth toward the end of the study. Learners with ‘medium proficiency’ had the largest L2 speaking development, especially with regard to producing longer and more diverse texts. Finally, for the most proficient learners there was little evidence of growth throughout the study.

Discussion

The present study’s aim was to examine the developmental process of L2 English speaking in adolescent learners who are living in a context where there is easy access to English outside the classroom. Previous research (e.g. De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020; Puimège & Peters, Reference Puimège and Peters2019) in similar contexts has shown that learners start formal English education with large individual differences in initial proficiency and longitudinal studies have shown that initial proficiency is highly predictive for language learning outcomes two years later (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2021). In the present study I looked into the learning process and the impact of initial proficiency in this process. This study wanted to expand on previous microdevelopment studies investigating L2 speaking development from a CDST-perspective by looking at multiple case studies in order to uncover real-time development and to shed light on possible differences between learners but also on overall principles of change related to learners’ initial proficiency level.

I first investigated how learners’ L2 English speaking developed over time. In line with previous studies that addressed L2 English speaking development from a CDST-perspective (e.g. Lowie et al., Reference Lowie, Van Dijk, Chan and Verspoor2017; Yu & Lowie, Reference Yu and Lowie2019) I found that various measures developed at different speeds. Lexical productivity clearly developed over time, whereas other measures (lexical diversity, syntactic complexity, and syntactic sophistication) significantly developed for one task type (informative task) but no significant changes were found over time for lexical sophistication (word frequency). Even though this was not the primary focus of the present study, the results showed that task type also significantly impacted the results, which is in line with previous studies (Alexopoulou et al., Reference Alexopoulou, Michel, Murakami and Meurers2017; Kyle & Crossley, Reference Kyle and Crossley2018).

The results for individual learners further showed that, overall, periods of significant growth were observed more frequently in lexical measures than in syntactic measures. A finding which is in line with other studies that have investigated real-time L2 development (Caspi, Reference Caspi2010; e.g. Verspoor et al., Reference Verspoor, Lowie and Van Dijk2008) and with studies that have looked into L1 acquisition. Research into first language acquisition has found that lexical knowledge precedes the emergence of grammar (Bates & Goodman, Reference Bates, Goodman and MacWhinney1999). This has been explained by the critical mass hypothesis (Marchman & Bates, Reference Marchman and Bates1994) which states that learners should have a certain amount of lexical knowledge before syntactic knowledge can develop. As the learners in our study were at the start of L2 English instruction and some of them were absolute beginners, it was thus not surprising that more growth was observed for lexical measures.

As I was particularly interested in the relationship between initial proficiency and L2 speaking development, I then modeled GAMMs for each variable in which I added language proficiency as an independent variable. All models improved when this variable was added which showed that initial proficiency and speaking development were clearly related. There was a significant increase in the word count dependent on the learners’ initial proficiency, but the variable had a different impact on each task type. For the narrative tasks learners with a low initial proficiency produced short texts. Text length first steeply increased with higher initial proficiency but leveled off at a certain proficiency level. For the informative tasks this stabilization did not take place and text length continued to increase with increasing proficiency. This might be explained by a ceiling effect in the picture-narration task. The task was quite closed and once a learner could tell what was happening in the picture, there was no incentive to produce longer texts, whereas with an open question, someone with a higher proficiency level could give longer and more elaborate answers. A similar picture emerges for mean length of T-unit, even though the shape of the smooths is slightly different and the effect of proficiency on MLT was not significant in the narrative task. Learners with lower proficiency levels answered the questions with short sentences or even single words, whereas more proficient learners were inclined to use longer sentences. As would be expected, lexical diversity also increased with higher proficiency. This happened in a linear manner and for both tasks. The impact of initial proficiency on word frequency and verb-VAC frequency was only significant for word frequency in the informative task. The results for the frequency measures further show large confidence intervals. From previous studies on L2 speaking (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Crossley and Kyle2019; Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Skalicky, Kyle and Monteiro2019; Eguchi & Kyle, Reference Eguchi and Kyle2020) and L2 writing in adolescents (De Wilde, Reference De Wilde2023) we know that it takes some time before frequency effects become visible as absolute beginners do not have enough knowledge to already be sensitive to frequency. Overall, the more proficient learners in this study, who were still not advanced learners but who were able to use English for A2-level tasks, used high-frequency words. These could be frequent content words which they encountered frequently in the input they received, but also function words, which are highly frequent words, but which are often omitted by beginners. Furthermore, longer texts likely also contained more high frequency words. The findings in our study are thus in line with previous studies but at the same time still show large variability among learners who are more proficient.

Finally, I considered the role of initial proficiency on individual learners’ trajectories. The learning trajectories of the individual learners seemed to suggest that learners with higher scores at the start of the study seemed to exhibit less growth, as did learners with very low scores. This was in line with findings from previous studies which suggested a stabilization of growth in learners with higher proficiency (Crossley et al., Reference Crossley, Salsbury and McNamara2010; Lowie et al., Reference Lowie, Van Dijk, Chan and Verspoor2017) and the need for a certain threshold of language proficiency before variability and growth can occur (Pfenninger, Reference Pfenninger2020). Proficient learners’ language exhibited the desired complexity that was necessary for this task type from the beginning of the study, and it was thus not necessary to use more or less complex language. As the learners were able to do the given task, we can conclude that their language was adequate for this specific type of task and thus the complexity is at the appropriate level (cf. Pallotti, Reference Pallotti2009). Even though I could detect trends in individual learners’ trajectories, none of the trajectories are identical for individual learners. The specificities in the individual trajectories confirm previous CDST-studies which have shown that the language learning process is highly individual and dependent on many different linguistic and nonlinguistic variables. Thus, both group trajectories and individual trajectories should be considered (cf. Lowie & Verspoor, Reference Lowie and Verspoor2019; Yu & Lowie, Reference Yu and Lowie2019).

The study also has clear pedagogical implications. The learners in this study were all in the same class group and all received the same English instruction, even though they widely differed in their L2 English proficiency, even at the start of the school year. This situation is not an exception in a context in which contact with English is not limited to the classroom, and a lot of learning can take place outside the school context, a context in which a lot of European young learners grow up (Lindgren & Muñoz, Reference Lindgren and Muñoz2013). The present study showed that teachers are confronted with many different learners and that the differences persisted throughout the year. The most proficient learners might in fact benefit from different, more challenging, and open-ended tasks in order to be able to practice L2 English speaking activities they do not yet master. On the other hand, teachers should be aware that some learners have a very low level and their progress in L2 speaking might be minimal at the start of the lessons or maybe even throughout the school year (e.g. participants S15 and S1). Finally, the study showed that even for the learners who seemed to be at the “optimal level” to learn, L2 speaking development followed a trajectory with ups and downs and various aspects of complexity in L2 speaking developed at different moments in time and at different rates. The results of the present study showed challenges and maybe difficulties for teachers, but some guidelines could be formulated that may assist teachers who work in these mixed-ability classrooms. One thing that was clear in the development of multiple individual learners is the importance of vocabulary at the early stages of L2 English learning and speaking. This finding confirms the importance of explicit vocabulary teaching to give students some basic tools to start expressing themselves.

Finally, this study also has some limitations. Even though this study contributed to CDST-studies on L2 speaking development by looking into multiple individual cases, the sample size is still quite small. It is therefore warranted to conduct similar studies looking into the development of L2 English speaking in other contexts. Furthermore, the investigation of lexical diversity could be less reliable for short texts (Koizumi, Reference Koizumi2012) even when using MTLD as a measure. Future studies could investigate the relationships between other aspects of complexity but also measures of accuracy or fluency and consider individual difference variables such as affective or cognitive variables. One of the measures in the study, lexical productivity, might be considered a fluency measure rather than a complexity measure (even though the tasks were not timed). However, as some of the learners in the study are in the very early stages of learning English and the first evidence of learning is the use of English words, I believe it was crucial to also add this variable to the study in order to be able to meaningfully interpret the results.

Data availability statement

The experiment in this article earned Open Data and Open Materials badges for transparent practices. The data are available at https://osf.io/fzcn9/overview.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263126101570.

Competing interests

The author declares none.