1. Introduction

Gravity currents are flows driven by natural convection, where gravity acts on a density gradient within a fluid (Huppert Reference Huppert2006; Wells & Dorrell Reference Wells and Dorrell2021). These buoyancy-driven flows are ubiquitous in both industrial and environmental settings, where gradients in fluid density may arise due to spatial variation in temperature, or in the concentration of suspended particulate or solute material.

Environmental gravity currents are often large-scale events that may cause significant hazards to both human life and structures. Naturally occurring examples include pyroclastic flows, powder-snow avalanches and turbidity currents. Pyroclastic flows, dense surface currents consisting of volcanic material and interstitial air, pose some of the most significant geohazard risks following a volcanic eruption. This is due to the high temperatures and speeds with which they propagate, often over 30 m s−1 and 500

![]() $^\circ$

C, with a current thickness typically of the order of hundreds of metres (Wilson Reference Wilson2008). Powder-snow avalanches are a widely known form of gravity current on the Earth’s surface. They are driven by the suspension of snow particles, with air forming the interstitial fluid (Hopfinger Reference Hopfinger1983). Turbidity currents are ocean-floor sedimentary gravity currents that can run-out for thousands of kilometres along the ocean floor. Their deposits can host important natural resources (Reece, Dorrell & Straub Reference Reece, Dorrell and Straub2024). They travel with depth-averaged velocities of 0.1–6.6 m s−1, a current thickness of 95–135 m, and may pose a threat to ocean floor infrastructure such as pipelines and telecommunication cables (Meiburg & Kneller Reference Meiburg and Kneller2010; Peakall & Sumner Reference Peakall and Sumner2015; Wells & Dorrell Reference Wells and Dorrell2021).

$^\circ$

C, with a current thickness typically of the order of hundreds of metres (Wilson Reference Wilson2008). Powder-snow avalanches are a widely known form of gravity current on the Earth’s surface. They are driven by the suspension of snow particles, with air forming the interstitial fluid (Hopfinger Reference Hopfinger1983). Turbidity currents are ocean-floor sedimentary gravity currents that can run-out for thousands of kilometres along the ocean floor. Their deposits can host important natural resources (Reece, Dorrell & Straub Reference Reece, Dorrell and Straub2024). They travel with depth-averaged velocities of 0.1–6.6 m s−1, a current thickness of 95–135 m, and may pose a threat to ocean floor infrastructure such as pipelines and telecommunication cables (Meiburg & Kneller Reference Meiburg and Kneller2010; Peakall & Sumner Reference Peakall and Sumner2015; Wells & Dorrell Reference Wells and Dorrell2021).

The current and ambient fluid have initial densities of

![]() $\rho _{{0}}$

and

$\rho _{{0}}$

and

![]() $\rho _{{a}}$

, respectively. The system has a reduced gravity

$\rho _{{a}}$

, respectively. The system has a reduced gravity

![]() $g'=g(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}$

, where

$g'=g(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}$

, where

![]() $g$

is the acceleration due to gravity. When

$g$

is the acceleration due to gravity. When

![]() $(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}\ll 1$

the current can be modelled using the Boussinesq approximation, where density variations within the fluid are neglected in the governing equations unless they are acted on by gravity (Meiburg & Kneller Reference Meiburg and Kneller2010; Tritton Reference Tritton2012; Fukuda et al. Reference Fukuda2023). Non-Boussinesq flows are beyond the scope of the present study.

$(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}\ll 1$

the current can be modelled using the Boussinesq approximation, where density variations within the fluid are neglected in the governing equations unless they are acted on by gravity (Meiburg & Kneller Reference Meiburg and Kneller2010; Tritton Reference Tritton2012; Fukuda et al. Reference Fukuda2023). Non-Boussinesq flows are beyond the scope of the present study.

Environmental gravity currents are challenging to observe directly due to their large scale, infrequent and destructive nature. The dynamics of dilute currents are studied using theoretical, experimental and numerical modelling. Quantifying and predicting front propagation speeds is of particular interest when studying the dynamics of gravity currents. Canonical idealised models consider a ‘lock-gate’ release of a denser than ambient fluid (Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983; Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Meiburg, Radhakrishnan & Nasr-Azadani Reference Meiburg, Radhakrishnan and Nasr-Azadani2015). Such models consist of a straight channel with a gate, separating a relatively dense fluid of concentration

![]() $\rho _{{0}}$

, from a lighter ambient fluid of concentration

$\rho _{{0}}$

, from a lighter ambient fluid of concentration

![]() $\rho _{{a}}\lt \rho _{{0}}$

. When the gate is removed a horizontal hydrostatic pressure gradient is created, which induces a gravity current to propagate along the channel (Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Andrews & Manga Reference Andrews and Manga2012). The characteristic length scale in the vertical and horizontal directions are taken to be the initial current depth

$\rho _{{a}}\lt \rho _{{0}}$

. When the gate is removed a horizontal hydrostatic pressure gradient is created, which induces a gravity current to propagate along the channel (Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Andrews & Manga Reference Andrews and Manga2012). The characteristic length scale in the vertical and horizontal directions are taken to be the initial current depth

![]() $h_{{0}}$

, and lock length

$h_{{0}}$

, and lock length

![]() $x_{{0}}$

, respectively. The buoyancy velocity,

$x_{{0}}$

, respectively. The buoyancy velocity,

![]() $U_{{b}}=\sqrt {g'h_{{0}}}$

, is the characteristic velocity scale. The non-dimensional parameters that govern the dynamics of the lock-exchange gravity current are the buoyancy Reynolds number,

$U_{{b}}=\sqrt {g'h_{{0}}}$

, is the characteristic velocity scale. The non-dimensional parameters that govern the dynamics of the lock-exchange gravity current are the buoyancy Reynolds number,

and Schmidt number,

where

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity of the ambient fluid, and

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity of the ambient fluid, and

![]() $D$

is the diffusivity of the scalar concentration field.

$D$

is the diffusivity of the scalar concentration field.

Following a brief acceleration phase, gravity currents transition through three distinct phases: slumping, inertial and viscous (Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980). In the slumping phase the current propagates at a constant velocity referred to as the buoyancy Froude number,

![]() $\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=u_{\!{f}}/U_{{b}}$

, under a balance of pressure and drag forces. The inertial phase is governed by a balance of inertial and buoyancy forces, where front location scales like

$\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=u_{\!{f}}/U_{{b}}$

, under a balance of pressure and drag forces. The inertial phase is governed by a balance of inertial and buoyancy forces, where front location scales like

![]() $x_{\!{f}}\propto t^{({2}/{3})}$

(Fay Reference Fay1971; Hoult Reference Hoult1972; Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and Garcia2007). The viscous phase is governed by a balance of viscous and buoyancy forces, where front location scales like

$x_{\!{f}}\propto t^{({2}/{3})}$

(Fay Reference Fay1971; Hoult Reference Hoult1972; Huppert & Simpson Reference Huppert and Simpson1980; Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and Garcia2007). The viscous phase is governed by a balance of viscous and buoyancy forces, where front location scales like

![]() $x_{\!{f}}\propto t^{({1}/{5})}$

(Hoult Reference Hoult1972; Huppert Reference Huppert1982; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and Garcia2007).

$x_{\!{f}}\propto t^{({1}/{5})}$

(Hoult Reference Hoult1972; Huppert Reference Huppert1982; Cantero et al. Reference Cantero, Lee, Balachandar and Garcia2007).

Standard lock-exchange experiments model an environmental flow in which a finite volume of dense fluid is instantaneously released. However, in naturally occurring currents dense material is often released in successive stages, generating pulsed currents. Pulsed flows have various potential causes, including temporal variation in seismic activity, retrogressive slope failure and the confluence of two gravity current flows (Mulder & Alexander Reference Mulder and Alexander2001; Beeson, Johnson & Goldfinger Reference Beeson, Johnson and Goldfinger2017; Goldfinger et al. Reference Goldfinger, Galer, Beeson, Hamilton, Black, Romsos, Patton, Nelson, Hausmann and Morey2017; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Gomberg, Hautala and Salmi2017). The geological record at the Cascadia margin, Washington, USA, provides evidence of deposits formed by the merging of turbidity currents at multiple channel confluences (Goldfinger et al. Reference Goldfinger, Galer, Beeson, Hamilton, Black, Romsos, Patton, Nelson, Hausmann and Morey2017).

The pyroclastic flow generated by the Soufrière Hills Volcano eruption in 1997 contained three distinct current releases. However, hazard assessments assumed a single release (Loughlin et al. Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002). Using the details documented by Loughlin et al. (Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002) we can estimate the non-dimensional delay time between the first and second pulse. Loughlin et al. (Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002) states that the current eruption was associated with three seismic events, which occurred at times 12:57:15 (

![]() $\pm \, 20 \,\mathrm{s}$

), 12:59:55 (

$\pm \, 20 \,\mathrm{s}$

), 12:59:55 (

![]() $\pm \, 30 \,\mathrm{s}$

) and 13:08:20 (

$\pm \, 30 \,\mathrm{s}$

) and 13:08:20 (

![]() $\pm \, 30 \,\mathrm{s}$

). The first and second pulse were therefore separated by 110–210 s. Loughlin et al. (Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002) reports a reference density for the current of

$\pm \, 30 \,\mathrm{s}$

). The first and second pulse were therefore separated by 110–210 s. Loughlin et al. (Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002) reports a reference density for the current of

![]() $1.6\:\mathrm{kg\,m}^{-3}$

, and we assume ambient air is at standard temperature and pressure (

$1.6\:\mathrm{kg\,m}^{-3}$

, and we assume ambient air is at standard temperature and pressure (

![]() $1.29\:\mathrm{kg\,m}^{-3}$

). Given these values we have a reduced gravity of

$1.29\:\mathrm{kg\,m}^{-3}$

). Given these values we have a reduced gravity of

![]() $g' = 2.36\:\mathrm{m\,s}^{-2}$

. Finally, we must assign a characteristic length scale for the system as Loughlin et al. (Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002) does not estimate the initial flow depth. We take the length scale to be in the range

$g' = 2.36\:\mathrm{m\,s}^{-2}$

. Finally, we must assign a characteristic length scale for the system as Loughlin et al. (Reference Loughlin, Calder, Clarke, Cole, Luckett, Mangan, Pyle, Sparks, Voight and Watts2002) does not estimate the initial flow depth. We take the length scale to be in the range

![]() $[500, 1000]\,\mathrm{m}$

, as this is the order of magnitude of the flow depth of pyroclastic currents (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Beckett, Bernard, Breard, Dioguardi, Dufek, Engwell and Eychenne2023). A length scale of

$[500, 1000]\,\mathrm{m}$

, as this is the order of magnitude of the flow depth of pyroclastic currents (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Beckett, Bernard, Breard, Dioguardi, Dufek, Engwell and Eychenne2023). A length scale of

![]() $500\,\mathrm{m}$

results in a buoyancy velocity of

$500\,\mathrm{m}$

results in a buoyancy velocity of

![]() $U_{\textit{b}} = 34.3\:\mathrm{m\,s}^{-1}$

, and a non-dimensional time delay between the first and second pulse in the range

$U_{\textit{b}} = 34.3\:\mathrm{m\,s}^{-1}$

, and a non-dimensional time delay between the first and second pulse in the range

![]() $[7.55, 14.42]$

, accounting for uncertainty in the release times. Taking a length scale of

$[7.55, 14.42]$

, accounting for uncertainty in the release times. Taking a length scale of

![]() $1000\,\mathrm{m}$

results in a buoyancy velocity scale of

$1000\,\mathrm{m}$

results in a buoyancy velocity scale of

![]() $U_{\textit{b}} = 48.55\:\mathrm{m\,s}^{-1}$

, and a non-dimensional time delay between the first and second pulse in the range

$U_{\textit{b}} = 48.55\:\mathrm{m\,s}^{-1}$

, and a non-dimensional time delay between the first and second pulse in the range

![]() $[5.34, 10.20]$

. We investigate the dynamics of pulsed currents using an idealised experiment to allow careful study of the impact on front propagation relative to an instantaneous release for a wide range of non-dimensional delay times between pulses. Here, for simplicity, we use conservative flows as a proxy for non-conservative depositional flows (Meiburg et al. Reference Meiburg, Radhakrishnan and Nasr-Azadani2015).

$[5.34, 10.20]$

. We investigate the dynamics of pulsed currents using an idealised experiment to allow careful study of the impact on front propagation relative to an instantaneous release for a wide range of non-dimensional delay times between pulses. Here, for simplicity, we use conservative flows as a proxy for non-conservative depositional flows (Meiburg et al. Reference Meiburg, Radhakrishnan and Nasr-Azadani2015).

There have been limited studies on pulsed gravity currents. Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018a

) conducted lock-exchange experiments where two locks of length

![]() $x_{{0}}$

were released successively, with a non-dimensional delay time of

$x_{{0}}$

were released successively, with a non-dimensional delay time of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} = (t_{\textit{re}} U_{\textit{b}})/x_0$

separating the release of the first and second lock, where

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} = (t_{\textit{re}} U_{\textit{b}})/x_0$

separating the release of the first and second lock, where

![]() $t_{\textit{re}}$

is the dimensional delay time. The results showed the second current propagated as an intrusion into the first and ultimately the pulses merged to form a unified front, as can be observed in the visualisations of the experiments presented in figure 1. Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018a

) also considered the implications for sedimentary deposits in turbidity currents, which was explored further by Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Thomas, Burns, Baas and McCaffrey2019). Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018b

) conducted an analysis of the length scales of pulse merging. The pulsed gravity problem has similarities to the two-layer stratified locks, in that two gravity currents interact and mix over the lifetime of the flow (Dai Reference Dai2017; Zhu, He & Meiburg Reference Zhu, He and Meiburg2023).

$t_{\textit{re}}$

is the dimensional delay time. The results showed the second current propagated as an intrusion into the first and ultimately the pulses merged to form a unified front, as can be observed in the visualisations of the experiments presented in figure 1. Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018a

) also considered the implications for sedimentary deposits in turbidity currents, which was explored further by Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Thomas, Burns, Baas and McCaffrey2019). Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018b

) conducted an analysis of the length scales of pulse merging. The pulsed gravity problem has similarities to the two-layer stratified locks, in that two gravity currents interact and mix over the lifetime of the flow (Dai Reference Dai2017; Zhu, He & Meiburg Reference Zhu, He and Meiburg2023).

Figure 1. Visualisation of a sequential lock-box gravity current release (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018a

). In the experiments the lock-box length

![]() $x_{{0}}=0.125\:\mathrm{m}$

, the initial current depth

$x_{{0}}=0.125\:\mathrm{m}$

, the initial current depth

![]() $h_{{0}}=0.05\:\mathrm{m}$

, the second lock was released at

$h_{{0}}=0.05\:\mathrm{m}$

, the second lock was released at

![]() $t_{\textit{re}}=4\:\mathrm{s}$

and the buoyancy velocity scale

$t_{\textit{re}}=4\:\mathrm{s}$

and the buoyancy velocity scale

![]() $U_{{b}}=0.1566\:\mathrm{m}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}$

. Time is non-dimensionalised as

$U_{{b}}=0.1566\:\mathrm{m}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}$

. Time is non-dimensionalised as

![]() $\tilde {t}=(t U_{{b}})/x_{{0}}$

, resulting in a non-dimensional release time of

$\tilde {t}=(t U_{{b}})/x_{{0}}$

, resulting in a non-dimensional release time of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=5$

.

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=5$

.

Methods used to numerically model idealised lock-gate releases can broadly be divided into two categories: depth-averaged models based on the shallow-water equations (SWEs) (Dorrell et al. Reference Dorrell, Darby, Peakall, Sumner, Parsons and Wynn2014), and depth-resolving models based on the Navier–Stokes equations (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Dorrell, Dutta, Keevil, Peakall and Tobias2021). Numerical simulations of pulsed gravity currents were conducted by Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020), where the authors applied a depth-averaged SWE model to simulate the flow generated by a pulsed lock-exchange experiment, and explored pulsed flows for different regimes of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) showed that as

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) showed that as

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\to \infty$

the pulses propagate as separate currents, and for

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\to \infty$

the pulses propagate as separate currents, and for

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\lt 1$

flow is equivalent to a single stage release of twice the volume, as the backwards travelling wave has yet to impact the second lock. For intermediate values of

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\lt 1$

flow is equivalent to a single stage release of twice the volume, as the backwards travelling wave has yet to impact the second lock. For intermediate values of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, the second pulse advanced more rapidly than the first and ultimately merged with it, in agreement with the experimental findings. Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) also observed that the speed of the second current at the time of merging was positively correlated with the delay time between releases. However, Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) terminated simulations at the time of pulse merging. The front propagation of pulsed gravity currents after the currents merge, as a function of

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, the second pulse advanced more rapidly than the first and ultimately merged with it, in agreement with the experimental findings. Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) also observed that the speed of the second current at the time of merging was positively correlated with the delay time between releases. However, Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) terminated simulations at the time of pulse merging. The front propagation of pulsed gravity currents after the currents merge, as a function of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, has not been studied.

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, has not been studied.

The present study aims to address this open research question using the results of pulsed lock-exchange physical experiments, in combination with depth-averaged and depth-resolving numerical models. The research objectives are to investigate the front propagation of pulsed currents as a function of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

and elucidate the underlying dynamics.

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

and elucidate the underlying dynamics.

2. Methods

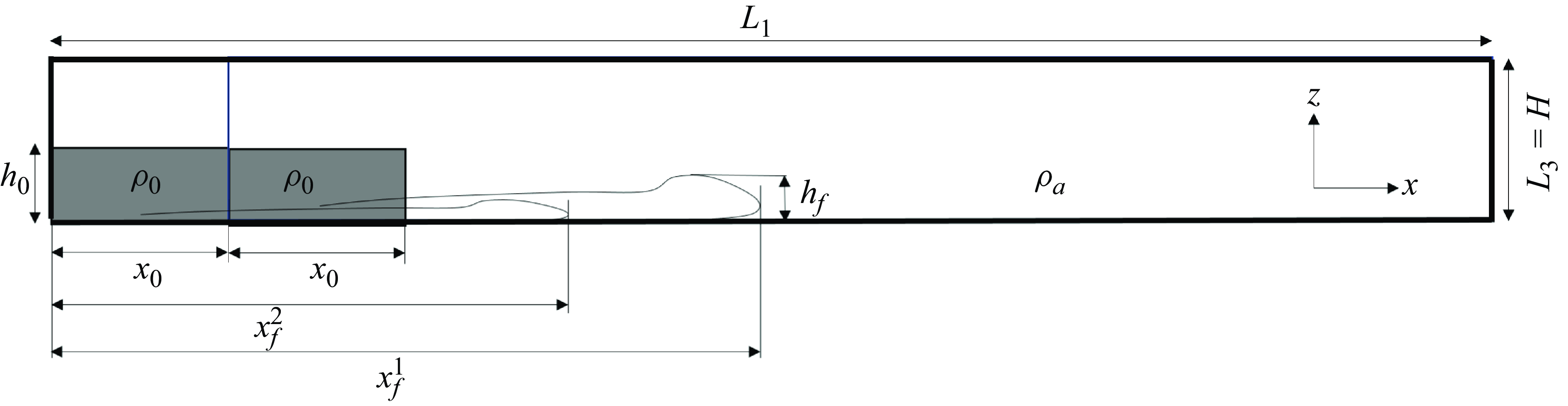

The dynamics of pulsed gravity currents are investigated using physical experiments and numerical simulations, where the simulations include both depth-averaging and depth-resolving numerical models. We consider the dual-stage release lock-exchange problem. A schematic of the problem set-up and key parameters are presented in figure 2. The set-up consists of a straight channel of length

![]() $L_{{1}}$

, width

$L_{{1}}$

, width

![]() $L_{{2}}$

and height

$L_{{2}}$

and height

![]() $L_{{3}}$

. The channel contains two locks, each retaining a saline mixture of density

$L_{{3}}$

. The channel contains two locks, each retaining a saline mixture of density

![]() $\rho _{{0}}$

, separated from ambient fluid of density

$\rho _{{0}}$

, separated from ambient fluid of density

![]() $\rho _{{a}}$

. The density difference between the saline mixture and ambient fluid is small,

$\rho _{{a}}$

. The density difference between the saline mixture and ambient fluid is small,

![]() $(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}\ll 1$

, hence the Boussinesq approximation can be applied. The initial depth of dense fluid is

$(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}\ll 1$

, hence the Boussinesq approximation can be applied. The initial depth of dense fluid is

![]() $h_{{0}}$

, with the remaining channel depth (

$h_{{0}}$

, with the remaining channel depth (

![]() $L_3-h_{{0}}$

) containing ambient fluid. Both locks have a length of

$L_3-h_{{0}}$

) containing ambient fluid. Both locks have a length of

![]() $x_{{0}}$

. The gates are released successively, with a delay time of

$x_{{0}}$

. The gates are released successively, with a delay time of

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=({ t_{\textit{re}} U_{{b}} }/{x_{{0}}})$

between the release of the first and second lock. The front location of the pulses generated by the first and second release are

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=({ t_{\textit{re}} U_{{b}} }/{x_{{0}}})$

between the release of the first and second lock. The front location of the pulses generated by the first and second release are

![]() $x_{\!{f}}^1$

and

$x_{\!{f}}^1$

and

![]() $x_{\!{f}}^2$

, respectively.

$x_{\!{f}}^2$

, respectively.

Figure 2. Schematic of dual-stage lock-exchange experiment.

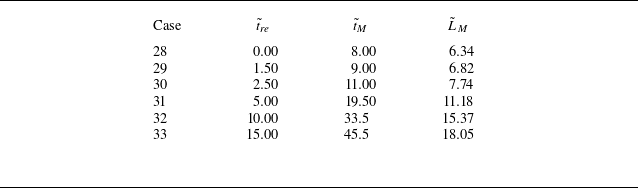

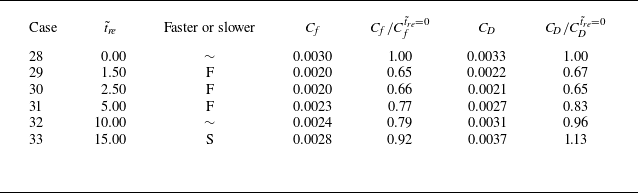

Table 1. Case parameters for the dual-stage release lock-exchange study. The parameter space was investigated using a combination of physical experiments (Exp), depth-averaged SWE simulations and depth-resolving LBM simulations as indicated in the table.

Thirty-three physical and numerical experiments quantifying dual-stage release flows are considered, the parameters for each case are presented in table 1. The physical experiments were conducted at a buoyancy Reynolds number of

![]() $\textit{Re}_{{b}} \approx 6000$

. The case list includes fractional depths of release of

$\textit{Re}_{{b}} \approx 6000$

. The case list includes fractional depths of release of

![]() $h_{{0}}/L_{{3}} \in {\{10^{-5}, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5\}}$

. For each fractional depth of release we vary the non-dimensional delay time between the release of the first and second lock,

$h_{{0}}/L_{{3}} \in {\{10^{-5}, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5\}}$

. For each fractional depth of release we vary the non-dimensional delay time between the release of the first and second lock,

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. As indicated in table 1, depth-averaged SWE simulations were conducted for Cases 1–27, physical experiments are run for Cases 13–18 and 25–27, and depth-resolving lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) simulations were run for Cases 25–33. The LBM simulations were run with a Reynolds number of

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. As indicated in table 1, depth-averaged SWE simulations were conducted for Cases 1–27, physical experiments are run for Cases 13–18 and 25–27, and depth-resolving lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) simulations were run for Cases 25–33. The LBM simulations were run with a Reynolds number of

![]() $\textit{Re}_{{b}}=6000$

. This allows the results of the physical experiments, SWE simulations and LBM simulations to be directly compared for Cases 25–27, where

$\textit{Re}_{{b}}=6000$

. This allows the results of the physical experiments, SWE simulations and LBM simulations to be directly compared for Cases 25–27, where

![]() $h_{{0}}/L_{{3}} = 0.5$

. We are able to explore a wider parameter space with the SWE model due to its low computational cost relative to the depth-resolving LBM simulations.

$h_{{0}}/L_{{3}} = 0.5$

. We are able to explore a wider parameter space with the SWE model due to its low computational cost relative to the depth-resolving LBM simulations.

2.1. Physical experiments

Physical experiments modelling pulsed-release lock-exchange gravity currents were conducted in a 5 m-long flume. At one end of the flume, two saline fluid regions of the same volume were contained in two lockboxes set up in series to model a pulsed current with two releases. The experimental set-up follows that of Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018a , Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018b ) and Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). Fluid in the two lockboxes were dyed yellow and blue to enable the visualisation of current mixing. The timing between two lock gates was set to vary between 0 s and 21.2 s using a pneumatic lock control box that ensured repeatability of both the timing and the speed of withdrawal of the lock. The density excess of the saline was 5 %. The height of the initial saline fluids and the length of each lock box were 0.05 m and 0.125 m, respectively. Ambient heights were set at 0.1 m and 0.25 m. The evolution of flows was captured using two rail mounted high-definition cameras, tracking individual pulse fronts.

2.2. Numerical modelling

The macroscopic governing equations for a pulsed lock-exchange saline gravity current flow are those of mass and momentum conservation for an incompressible flow coupled, via the Boussinesq approximation, with an advection–diffusion equation for the scalar concentration field. Fluid density is defined as

where

![]() $\alpha =(\rho _{{s}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}$

,

$\alpha =(\rho _{{s}}-\rho _{{a}})/\rho _{{a}}$

,

![]() $\rho _{{s}}$

is solute density and

$\rho _{{s}}$

is solute density and

![]() $\chi (\boldsymbol{x},t)$

is solute concentration. The body force generated by the action of gravity is

$\chi (\boldsymbol{x},t)$

is solute concentration. The body force generated by the action of gravity is

![]() $\boldsymbol{G}$

,

$\boldsymbol{G}$

,

where

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{z}}$

is the unit vector in the upward vertical direction.

$\hat {\boldsymbol{z}}$

is the unit vector in the upward vertical direction.

![]() $\boldsymbol{G}$

includes a constant term that is the hydrostatic pressure term in the momentum equation,

$\boldsymbol{G}$

includes a constant term that is the hydrostatic pressure term in the momentum equation,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} P= \boldsymbol{\nabla }(p_{{k}}(\boldsymbol{x},t))-g\rho _{{a}} z$

, where

$\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} P= \boldsymbol{\nabla }(p_{{k}}(\boldsymbol{x},t))-g\rho _{{a}} z$

, where

![]() $p_{{k}}$

is the kinematic pressure. The driving force is the Boussinesq forcing term

$p_{{k}}$

is the kinematic pressure. The driving force is the Boussinesq forcing term

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}_{\!\textit{B}}$

,

$\boldsymbol{F}_{\!\textit{B}}$

,

The governing equations are non-dimensionalised using the characteristic length scale

![]() $h_0=0.05$

m, and velocity scale

$h_0=0.05$

m, and velocity scale

![]() $U_{\textit{b}}=0.1566$

m s−1, resulting in the non-dimensional incompressible mass and momentum conservation equations,

$U_{\textit{b}}=0.1566$

m s−1, resulting in the non-dimensional incompressible mass and momentum conservation equations,

and an advection–diffusion equation for the scalar concentration field

![]() $\tilde {\chi }$

,

$\tilde {\chi }$

,

In addition to the buoyancy Reynolds number (

![]() $\textit{Re}_{{b}}$

) the governing equations are also parameterised by the Schmidt number

$\textit{Re}_{{b}}$

) the governing equations are also parameterised by the Schmidt number

![]() $Sc= ({\nu }/{D})$

, where

$Sc= ({\nu }/{D})$

, where

![]() $D$

is the diffusivity of the scalar field. All simulations are run with

$D$

is the diffusivity of the scalar field. All simulations are run with

![]() $Sc=1$

. The Schmidt number of real-world flows may be orders of magnitude larger, but the structure and dynamics of Boussinesq currents are relatively insensitive to Schmidt number for high Reynolds numbers of

$Sc=1$

. The Schmidt number of real-world flows may be orders of magnitude larger, but the structure and dynamics of Boussinesq currents are relatively insensitive to Schmidt number for high Reynolds numbers of

![]() $\mathcal{O}(10^4)$

(Bonometti & Balachandar Reference Bonometti and Balachandar2008; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Dorrell, Dutta, Keevil, Peakall and Tobias2021).

$\mathcal{O}(10^4)$

(Bonometti & Balachandar Reference Bonometti and Balachandar2008; Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Dorrell, Dutta, Keevil, Peakall and Tobias2021).

The concentration field is scaled relative to the initial saline concentration in the lock

![]() $\chi _{{0}}$

, i.e.

$\chi _{{0}}$

, i.e.

![]() $\tilde {\chi },(\boldsymbol{x},t)=\chi (\boldsymbol{x},t)/\chi _{{0}}$

. Fluid density is non-dimensionalised using the initial density of the current and ambient, such that

$\tilde {\chi },(\boldsymbol{x},t)=\chi (\boldsymbol{x},t)/\chi _{{0}}$

. Fluid density is non-dimensionalised using the initial density of the current and ambient, such that

![]() $\tilde {\rho }(\boldsymbol{x},t) = (\rho (\boldsymbol{x},t) - \rho _{{a}})/(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})$

. Variables with a

$\tilde {\rho }(\boldsymbol{x},t) = (\rho (\boldsymbol{x},t) - \rho _{{a}})/(\rho _{{0}}-\rho _{{a}})$

. Variables with a

![]() $\tilde{}$

accent are non-dimensionalised, and variables with a

$\tilde{}$

accent are non-dimensionalised, and variables with a

![]() $\bar {}$

accent are the spanwise average of a non-dimensionalised variable, i.e.

$\bar {}$

accent are the spanwise average of a non-dimensionalised variable, i.e.

\begin{equation} \bar {\rho }(\tilde {x},\tilde {z},\tilde {t})=\frac {1}{\tilde {L}_2}\int \limits _{0}^{\tilde {L}_2}\tilde {\rho }(\tilde {x},\tilde {y},\tilde {z},\tilde {t})\,\mathrm{d}\tilde {y}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \bar {\rho }(\tilde {x},\tilde {z},\tilde {t})=\frac {1}{\tilde {L}_2}\int \limits _{0}^{\tilde {L}_2}\tilde {\rho }(\tilde {x},\tilde {y},\tilde {z},\tilde {t})\,\mathrm{d}\tilde {y}. \end{equation}

Here the macroscopic governing equations are not solved directly. We compare the use of: a depth-averaged model, implemented using the shallow-water approximation (§ 2.2.1); and a depth-resolving model, solving the governing equations at a mesoscopic scale, using a LBM model (§ 2.2.2).

2.2.1. Depth-averaged shallow-water equations model

In this section the methodology for an analytical SWE model is presented. Shallow-water models have extensively been used to study the lock-exchange problem as they exploit the small ratio between depth and length scales

![]() $ \delta \sim h_{{f}}/x^1_{{f}}$

. Consider a two-layered flow of immiscible fluids of thicknesses

$ \delta \sim h_{{f}}/x^1_{{f}}$

. Consider a two-layered flow of immiscible fluids of thicknesses

![]() $h_1(x,t)$

and

$h_1(x,t)$

and

![]() $h_2(x,t)$

and of similar, but distinct densities

$h_2(x,t)$

and of similar, but distinct densities

![]() $\rho _{{a}}$

and

$\rho _{{a}}$

and

![]() $\rho _{{0}}$

, respectively, with

$\rho _{{0}}$

, respectively, with

![]() $\rho _{{a}}\lt \rho _{{0}}$

, figure 3. The flow is assumed to be symmetric in the cross-stream (

$\rho _{{a}}\lt \rho _{{0}}$

, figure 3. The flow is assumed to be symmetric in the cross-stream (

![]() $y$

-direction) and the flow properties only vary over the direction of propagation

$y$

-direction) and the flow properties only vary over the direction of propagation

![]() $x$

. Further, by assuming that the flows are inviscid, the depths

$x$

. Further, by assuming that the flows are inviscid, the depths

![]() $h_i$

and depth-averaged velocities

$h_i$

and depth-averaged velocities

![]() $u_i$

for each layer are functions of

$u_i$

for each layer are functions of

![]() $(x,t)$

only. Surface tension and other intermolecular forces are assumed to be negligible. With the rigid-lid assumption total depth is

$(x,t)$

only. Surface tension and other intermolecular forces are assumed to be negligible. With the rigid-lid assumption total depth is

![]() $\mathcal{H}(x,t)=h_1+h_2 = L_3$

and the the two-layer shallow-water model that was formulated by Rottman & Simpson (Reference Rottman and Simpson1983) can be applied. Using

$\mathcal{H}(x,t)=h_1+h_2 = L_3$

and the the two-layer shallow-water model that was formulated by Rottman & Simpson (Reference Rottman and Simpson1983) can be applied. Using

![]() $l_{{0}}$

as the length scale,

$l_{{0}}$

as the length scale,

![]() $h_{{0}}$

as our depth scale,

$h_{{0}}$

as our depth scale,

![]() $\sqrt {h_{{0}}g'}$

as the velocity scale and the convective time scale

$\sqrt {h_{{0}}g'}$

as the velocity scale and the convective time scale

![]() $\sqrt {h_{{0}}/g'}$

, the dimensionless equations two-layer shallow-water equations are

$\sqrt {h_{{0}}/g'}$

, the dimensionless equations two-layer shallow-water equations are

where

\begin{align} b &= \frac {\tilde {h}}{\tilde {L}_3} + \frac {\tilde {m}^2}{\tilde {L}_3\tilde {h}^2}\left (1-\frac {\tilde {h}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right )^{-2}\!. \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} b &= \frac {\tilde {h}}{\tilde {L}_3} + \frac {\tilde {m}^2}{\tilde {L}_3\tilde {h}^2}\left (1-\frac {\tilde {h}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right )^{-2}\!. \\[9pt] \nonumber \end{align}

Figure 3. Double lock-release configuration for the shallow-water model: before the second gate release, (a)

![]() $\tilde {t}\lt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, and after the second gate release, (b)

$\tilde {t}\lt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, and after the second gate release, (b)

![]() $\tilde {t}\gt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. The second release creates a shock in the solution which propagates forwards towards the head of the current. Horizontal and vertical lengths are non-dimensionalised by the lock-length

$\tilde {t}\gt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. The second release creates a shock in the solution which propagates forwards towards the head of the current. Horizontal and vertical lengths are non-dimensionalised by the lock-length

![]() $l_{\textit{lock}}$

and lock depth

$l_{\textit{lock}}$

and lock depth

![]() $h_{\text{0}}$

, respectively. The position of the head is labelled

$h_{\text{0}}$

, respectively. The position of the head is labelled

![]() $\tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

and the second release that appears as a shock

$\tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

and the second release that appears as a shock

![]() $\tilde {x}^2_{{f}}$

.

$\tilde {x}^2_{{f}}$

.

Note that in the infinitely deep ambient limit,

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

and

$\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

and

![]() $a,b\to 0$

, the single-layer equations are recovered (Ungarish & Zemach Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005; Ungarish Reference Ungarish2009). For flows in relatively deep

$a,b\to 0$

, the single-layer equations are recovered (Ungarish & Zemach Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005; Ungarish Reference Ungarish2009). For flows in relatively deep

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\gg 1$

, the standard shallow-water equations can still be used and flow in the ambient neglected (Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983; Hogg, Ungarish & Huppert Reference Hogg, Ungarish and Huppert2000; Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). However, as the ambient depth

$\tilde {L}_3\gg 1$

, the standard shallow-water equations can still be used and flow in the ambient neglected (Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983; Hogg, Ungarish & Huppert Reference Hogg, Ungarish and Huppert2000; Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). However, as the ambient depth

![]() $\tilde {L}_3$

decreases the propagation speed of characteristic curves reduces, which leads to quantitative differences in the solution for lock-exchange gravity currents. For example, the duration of the slumping phase (where the head moves at constant speed) is increased (Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983). The influence on the flow dynamics of the finite ambient depth increases as

$\tilde {L}_3$

decreases the propagation speed of characteristic curves reduces, which leads to quantitative differences in the solution for lock-exchange gravity currents. For example, the duration of the slumping phase (where the head moves at constant speed) is increased (Rottman & Simpson Reference Rottman and Simpson1983). The influence on the flow dynamics of the finite ambient depth increases as

![]() $\tilde {L}_3$

decreases until

$\tilde {L}_3$

decreases until

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\lt 2$

, where the formation of a backwards propagating shock causes qualitative differences in the solution (Klemp, Rotunno & Skamarock Reference Klemp, Rotunno and Skamarock1994; Ungarish & Zemach Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005). The changing dynamics as

$\tilde {L}_3\lt 2$

, where the formation of a backwards propagating shock causes qualitative differences in the solution (Klemp, Rotunno & Skamarock Reference Klemp, Rotunno and Skamarock1994; Ungarish & Zemach Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005). The changing dynamics as

![]() $\tilde {L}_3$

decreases arise because of the increased work done by current accelerating the ambient fluid as it moves.

$\tilde {L}_3$

decreases arise because of the increased work done by current accelerating the ambient fluid as it moves.

The initial and boundary conditions reflect a double lock-release and are equivalent to those used in Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020) to study dual-stage releases gravity currents in a infinitely deep ambient,

\begin{align} \tilde {h}(\tilde {x},0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\in [0,2],\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise}, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde {h}(\tilde {x},0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\in [0,2],\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise}, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \tilde {h}}{\partial \tilde {x}}(\tilde {x}_0,\tilde {t}) =& 0 \quad \text{for}\quad \begin{cases} \tilde {x}_0 = 0 ,1 \quad &\text{for}\quad 0\leqslant \tilde {t} \lt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}},\\ \tilde {x}_0 = 0 \quad &\text{for} \quad \tilde {t} \gt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}, \end{cases} \end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {\partial \tilde {h}}{\partial \tilde {x}}(\tilde {x}_0,\tilde {t}) =& 0 \quad \text{for}\quad \begin{cases} \tilde {x}_0 = 0 ,1 \quad &\text{for}\quad 0\leqslant \tilde {t} \lt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}},\\ \tilde {x}_0 = 0 \quad &\text{for} \quad \tilde {t} \gt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}, \end{cases} \end{align}

where

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

is the release time of the second lock box.

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

is the release time of the second lock box.

As discussed in the introduction, the moving head of the gravity current (right-hand boundary in this configuration) requires supplementation with a Froude number condition to accurately predict the propagation dynamics. The Froude number condition is expressed as a relationship between the depth

![]() $\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}$

and velocity

$\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}$

and velocity

![]() $\tilde {u}_{{f}}$

at the head of the flow

$\tilde {u}_{{f}}$

at the head of the flow

![]() $\tilde {x}=\tilde {x}_{{f}}^1(t)$

. At the head of the flow the dynamic boundary condition is also imposed giving

$\tilde {x}=\tilde {x}_{{f}}^1(t)$

. At the head of the flow the dynamic boundary condition is also imposed giving

where

![]() $\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}(\tilde {t}) = \tilde {h}(\tilde {x}=\tilde {x}^1_{{f}},\tilde {t})$

. In general the Froude number is a decreasing function of

$\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}(\tilde {t}) = \tilde {h}(\tilde {x}=\tilde {x}^1_{{f}},\tilde {t})$

. In general the Froude number is a decreasing function of

![]() $\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}/\tilde {L}_3$

and many experimental or analytical expression exist for it (Benjamin (Reference Benjamin1968), Huppert & Simpson (Reference Huppert and Simpson1980), Rottman & Simpson (Reference Rottman and Simpson1983)). As

$\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}/\tilde {L}_3$

and many experimental or analytical expression exist for it (Benjamin (Reference Benjamin1968), Huppert & Simpson (Reference Huppert and Simpson1980), Rottman & Simpson (Reference Rottman and Simpson1983)). As

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

, the Froude number tends to a constant value and for deep ambient flows a constant value is taken (Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). Ungarish & Zemach (Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005) present a semiempirical formulation,

$\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

, the Froude number tends to a constant value and for deep ambient flows a constant value is taken (Hogg Reference Hogg2006; Allen et al. Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). Ungarish & Zemach (Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005) present a semiempirical formulation,

\begin{equation} \textit{Fr} \left (\frac {\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right ) = \textit{Fr}_{\textit{u}z}\left (\frac {\tilde {h}_{\!{f}}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right ) \left (1+3\frac {\tilde {h}_{\!{f}}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right )^{-1/2}\!, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \textit{Fr} \left (\frac {\tilde{h}_{\kern-1pt f}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right ) = \textit{Fr}_{\textit{u}z}\left (\frac {\tilde {h}_{\!{f}}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right ) \left (1+3\frac {\tilde {h}_{\!{f}}}{\tilde {L}_3}\right )^{-1/2}\!, \end{equation}

as a compromise between other correlations whilst maintaining a reasonable agreement with a variety of experimental results. Crucially, the difference between these expressions is not particularly large in the region of shallow-water solutions

![]() $h_{\!{f}}/\tilde {L}_3 \lt 0.6$

(Ungarish & Zemach Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005). The present study is limited to the ranges

$h_{\!{f}}/\tilde {L}_3 \lt 0.6$

(Ungarish & Zemach Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005). The present study is limited to the ranges

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\geqslant 2$

, or

$\tilde {L}_3\geqslant 2$

, or

![]() $\tilde {h}_{\!{f}}/\tilde {L}_3 \lt 0.5$

. As

$\tilde {h}_{\!{f}}/\tilde {L}_3 \lt 0.5$

. As

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

,

$\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

,

![]() $\textit{Fr}_{\textit{u}z}\to 1$

. In addition to simulations conducted with

$\textit{Fr}_{\textit{u}z}\to 1$

. In addition to simulations conducted with

![]() $\textit{Fr}=\textit{Fr}_{\textit{u}z}$

, constant values of the Froude number

$\textit{Fr}=\textit{Fr}_{\textit{u}z}$

, constant values of the Froude number

![]() $ \textit{Fr} $

are also used for simulations with an infinitely deep ambient

$ \textit{Fr} $

are also used for simulations with an infinitely deep ambient

![]() $\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

.

$\tilde {L}_3\to \infty$

.

To numerically solve the two-layer shallow-water model, ((2.8) and (2.9)) are mapped onto the unit interval

![]() $[0,1]$

using the transformation

$[0,1]$

using the transformation

![]() $ (\zeta ,\tau )= (\tilde {x}/\tilde {x}^1_{{f}},\tilde {t} )$

. These scaled equations are solved using a Lax–Wendroff finite difference method similar to Bonnecaze, Huppert & Lister (Reference Bonnecaze, Huppert and Lister1993), Ungarish & Zemach (Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005) and Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). A small artificial viscosity term is introduced using the formulation presented in Ungarish & Zemach (Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005) to remove spurious oscillations that arise near large gradients and prevent the chequerboarding instability that arises with the Lax–Wendroff. For further details see Appendix A.

$ (\zeta ,\tau )= (\tilde {x}/\tilde {x}^1_{{f}},\tilde {t} )$

. These scaled equations are solved using a Lax–Wendroff finite difference method similar to Bonnecaze, Huppert & Lister (Reference Bonnecaze, Huppert and Lister1993), Ungarish & Zemach (Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005) and Allen et al. (Reference Allen, Dorrell, Harlen, Thomas and McCaffrey2020). A small artificial viscosity term is introduced using the formulation presented in Ungarish & Zemach (Reference Ungarish and Zemach2005) to remove spurious oscillations that arise near large gradients and prevent the chequerboarding instability that arises with the Lax–Wendroff. For further details see Appendix A.

2.2.2. Depth-resolving LBM model

Depth-resolving simulations are produced by solving the macroscopic governing equations at the mesoscopic scale, i.e. between the macroscopic and microscopic scales, using the LBM (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017). The LBM simulations are run in VirtualFluids, an open-source graphics processing unit accelerated code developed by the Institute for Computational Modelling in Civil Engineering (iRMB) at TU Braunschweig. Adekanye et al. (Reference Adekanye, Khan, Burns, McCaffrey, Geier, Schönherr and Dorrell2022) validated VirtualFluids for the simulation of instantaneous release lock-exchange gravity currents with Reynolds numbers up to

![]() $\textit{Re}_{{b}}=30\,000$

, showing good agreement with high-resolution simulations and physical experiments.

$\textit{Re}_{{b}}=30\,000$

, showing good agreement with high-resolution simulations and physical experiments.

At the mesoscopic scale fluid motion is described by the particle distribution function (PDF)

![]() $f(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{\xi }, t)$

, where

$f(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{\xi }, t)$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }$

is particle velocity. The PDF defines the density of particles at location

$\boldsymbol{\xi }$

is particle velocity. The PDF defines the density of particles at location

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

, moving with velocity

$\boldsymbol{x}$

, moving with velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }$

, at time

$\boldsymbol{\xi }$

, at time

![]() $t$

. The evolution of

$t$

. The evolution of

![]() $f(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{\xi }, t)$

is governed by the Boltzmann equation, which when discretised in space and time produces the lattice Boltzmann equation. In the present study we solve two two-way coupled lattice Boltzmann equations, one for the conservation of mass and momentum in the fluid,

$f(\boldsymbol{x},\boldsymbol{\xi }, t)$

is governed by the Boltzmann equation, which when discretised in space and time produces the lattice Boltzmann equation. In the present study we solve two two-way coupled lattice Boltzmann equations, one for the conservation of mass and momentum in the fluid,

and a second for the advection and diffusion of the scalar concentration field,

Solving the system of lattice Boltzmann equations for the PDFs

![]() $f_{\textit{ijk}}$

and

$f_{\textit{ijk}}$

and

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

is equivalent to to solving the macroscopic governing equations, (2.4)–(2.6) (Junk, Klar & Luo Reference Junk, Klar and Luo2004; Dubois Reference Dubois2008). The equations are coupled via their respective collision operators,

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

is equivalent to to solving the macroscopic governing equations, (2.4)–(2.6) (Junk, Klar & Luo Reference Junk, Klar and Luo2004; Dubois Reference Dubois2008). The equations are coupled via their respective collision operators,

![]() $\varOmega ^f_{\textit{ijk}}$

and

$\varOmega ^f_{\textit{ijk}}$

and

![]() $\varOmega ^\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

.

$\varOmega ^\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

.

The discretised PDF

![]() $f_{\textit{ijk}}(\boldsymbol{x}, t)$

, is defined at the nodes of a lattice structure in which lattice nodes are connected by a discrete velocity set

$f_{\textit{ijk}}(\boldsymbol{x}, t)$

, is defined at the nodes of a lattice structure in which lattice nodes are connected by a discrete velocity set

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }_{\textit{ijk}}$

. The indices

$\boldsymbol{\xi }_{\textit{ijk}}$

. The indices

![]() $i,j,k$

are permutations of the values

$i,j,k$

are permutations of the values

![]() $\{1, 0, -1\}$

, and so

$\{1, 0, -1\}$

, and so

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }_{\textit{ijk}}$

is a set of vectors to neighbouring nodes, which includes the zero vector. In the present study a

$\boldsymbol{\xi }_{\textit{ijk}}$

is a set of vectors to neighbouring nodes, which includes the zero vector. In the present study a

![]() $D3Q27$

lattice is used, which results in the lattice structure presented in figure 4. In effect, distributions are constrained to stream along the vectors

$D3Q27$

lattice is used, which results in the lattice structure presented in figure 4. In effect, distributions are constrained to stream along the vectors

![]() $\boldsymbol{\xi }_{\textit{ijk}}$

in time

$\boldsymbol{\xi }_{\textit{ijk}}$

in time

![]() $\Delta t$

, where they collide and are redistributed according to the collision operator

$\Delta t$

, where they collide and are redistributed according to the collision operator

![]() $\varOmega _{\textit{ijk}}$

. The raw moments of a distribution, of order

$\varOmega _{\textit{ijk}}$

. The raw moments of a distribution, of order

![]() $\alpha +\beta +\gamma$

, are defined as

$\alpha +\beta +\gamma$

, are defined as

Figure 4. The

![]() $D3Q27$

lattice structure.

$D3Q27$

lattice structure.

The macroscopic fluid density and momentum density are recovered from the zeroth and first-order raw moments of

![]() $f_{\textit{ijk}}$

,

$f_{\textit{ijk}}$

,

\begin{align} \rho \boldsymbol{u} = \rho (m_{100},m_{010},m_{001}=\left ( \sum _{i,j,k}i \kern-1pt f_{\textit{ijk}}+\frac {\Delta t}{2}F_B^x , \sum _{i,j,k}j \kern-1pt f_{\textit{ijk}}+\frac {\Delta t}{2}F_B^y, \sum _{i,j,k}k f_{\textit{ijk}}+\frac {\Delta t}{2}F_B^z \right )\!. \\[-2pt] \nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} \rho \boldsymbol{u} = \rho (m_{100},m_{010},m_{001}=\left ( \sum _{i,j,k}i \kern-1pt f_{\textit{ijk}}+\frac {\Delta t}{2}F_B^x , \sum _{i,j,k}j \kern-1pt f_{\textit{ijk}}+\frac {\Delta t}{2}F_B^y, \sum _{i,j,k}k f_{\textit{ijk}}+\frac {\Delta t}{2}F_B^z \right )\!. \\[-2pt] \nonumber \end{align}

The zeroth raw moment of the

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution gives the macroscopic concentration,

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution gives the macroscopic concentration,

Collisions for the

![]() $f_{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution are performed in cumulant space (Geier et al. Reference Geier, Schönherr, Pasquali and Krafczyk2015). Cumulants,

$f_{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution are performed in cumulant space (Geier et al. Reference Geier, Schönherr, Pasquali and Krafczyk2015). Cumulants,

![]() $C_{\textit{nrs}}$

, are relaxed towards their equilibria

$C_{\textit{nrs}}$

, are relaxed towards their equilibria

![]() $C_{\textit{nrs}}^{\textit{eq}}$

, at a rate

$C_{\textit{nrs}}^{\textit{eq}}$

, at a rate

![]() $\omega _{\textit{nrs}}$

,

$\omega _{\textit{nrs}}$

,

The relaxation rate of the second-order cumulants determine the macroscopic fluid viscosity,

Collisions for the

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution are conducted in central moment space, using the method presented by Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Mehmani, Perkins, Pasquali, Schönherr, Kim, Perego, Parks, Trask and Balhoff2016). The factorised central moments

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution are conducted in central moment space, using the method presented by Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Mehmani, Perkins, Pasquali, Schönherr, Kim, Perego, Parks, Trask and Balhoff2016). The factorised central moments

![]() $M_{\textit{nrs}}$

are relaxed towards zero at the rate

$M_{\textit{nrs}}$

are relaxed towards zero at the rate

![]() $\omega _{\textit{nrs}}$

,

$\omega _{\textit{nrs}}$

,

The diffusivity of the scalar field is determined by the relaxation rate of the first-order factorised central moments,

The dimensions of the computational domain are chosen to reflect the experimental conditions, with

![]() $L_1=27x_{{0}}$

, and

$L_1=27x_{{0}}$

, and

![]() $L_2=h_{{0}}$

, resulting in a non-dimensional domain size of

$L_2=h_{{0}}$

, resulting in a non-dimensional domain size of

![]() $\tilde {L}_1=27$

,

$\tilde {L}_1=27$

,

![]() $\tilde {L}_2=1$

,

$\tilde {L}_2=1$

,

![]() $\tilde {L}_3=L_3/h_0$

. Simulations are run on uniform meshes, with a spatial and time discretisation of

$\tilde {L}_3=L_3/h_0$

. Simulations are run on uniform meshes, with a spatial and time discretisation of

![]() $\Delta \tilde {x}={\Delta x}/{h_{{0}}}=0.01$

and

$\Delta \tilde {x}={\Delta x}/{h_{{0}}}=0.01$

and

![]() $\Delta \tilde {t}=3\times 10^{-4}$

, respectively. The grid resolution is chosen such that the largest length scales of turbulent motion are directly resolved, whilst stability is maintained by limiting the relaxation rate of the third-order cumulant, as specified in the parameterised cumulant method of Geier, Pasquali & Schönherr (Reference Geier, Pasquali and Schönherr2017).

$\Delta \tilde {t}=3\times 10^{-4}$

, respectively. The grid resolution is chosen such that the largest length scales of turbulent motion are directly resolved, whilst stability is maintained by limiting the relaxation rate of the third-order cumulant, as specified in the parameterised cumulant method of Geier, Pasquali & Schönherr (Reference Geier, Pasquali and Schönherr2017).

No-slip boundary conditions for the velocity field, and no-flux boundary conditions for the concentration field are applied to all external boundaries of the computational domain. These boundary conditions model the experimental set-up of the standard lock-exchange gravity current experiment, enabling direct validation against the observed front locations in the experimental results of Ho et al. (Reference Ho, Dorrell, Keevil, Burns and McCaffrey2018a ).

The specific conditions for the

![]() $\tilde {x}_{{B}}$

boundary are defined as

$\tilde {x}_{{B}}$

boundary are defined as

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ \boldsymbol{0}\\ \frac {\partial \tilde {\chi }}{\partial \tilde {x}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ 0 \end{aligned} \quad \text{for}\quad \begin{cases} \tilde {x}_{\!{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {x}_0 \lor \tilde {L}_1 \quad &\text{for}\quad 0\leqslant \tilde {t} \lt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\\ \tilde {x}_{\!{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {L}_1 \quad &\text{for} \quad \tilde {t} \geqslant \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} \end{cases}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ \boldsymbol{0}\\ \frac {\partial \tilde {\chi }}{\partial \tilde {x}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ 0 \end{aligned} \quad \text{for}\quad \begin{cases} \tilde {x}_{\!{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {x}_0 \lor \tilde {L}_1 \quad &\text{for}\quad 0\leqslant \tilde {t} \lt \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\\ \tilde {x}_{\!{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {L}_1 \quad &\text{for} \quad \tilde {t} \geqslant \tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} \end{cases}. \end{align}

A dual-stage release is achieved by inserting a no-slip and no-flux boundary condition on the

![]() $yz$

-plane at

$yz$

-plane at

![]() $\tilde {x}=\tilde {x}_0$

, which remains in effect until

$\tilde {x}=\tilde {x}_0$

, which remains in effect until

![]() $\tilde {t}=\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, as shown in (2.27). The removal of this internal wall simulates the release of the second lock gate.

$\tilde {t}=\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

, as shown in (2.27). The removal of this internal wall simulates the release of the second lock gate.

The no-slip and no-flux conditions for the

![]() $\tilde {y}_{{B}}$

and

$\tilde {y}_{{B}}$

and

![]() $\tilde {z}_{{B}}$

boundaries are defined as

$\tilde {z}_{{B}}$

boundaries are defined as

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ \boldsymbol{0}\\ \frac {\partial \tilde {\chi }}{\partial \tilde {y}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ 0 \end{aligned} \quad \text{for}\quad \tilde {y}_{\!{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {L}_2,\end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ \boldsymbol{0}\\ \frac {\partial \tilde {\chi }}{\partial \tilde {y}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}_{\!{B}}, \tilde {z}), \tilde {t}) =&\ 0 \end{aligned} \quad \text{for}\quad \tilde {y}_{\!{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {L}_2,\end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}_{{B}}), \tilde {t}) =&\ \boldsymbol{0}\\ \frac {\partial \tilde {\chi }}{\partial \tilde {z}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}_{{B}}), \tilde {t}) =&\ 0 \end{aligned} \quad \text{for}\quad \tilde {z}_{{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {L}_3. \end{align}

\begin{align} \begin{aligned} \tilde {\boldsymbol{u}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}_{{B}}), \tilde {t}) =&\ \boldsymbol{0}\\ \frac {\partial \tilde {\chi }}{\partial \tilde {z}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}=(\tilde {x}, \tilde {y}, \tilde {z}_{{B}}), \tilde {t}) =&\ 0 \end{aligned} \quad \text{for}\quad \tilde {z}_{{B}} = 0 \lor \tilde {L}_3. \end{align}

No-slip and no-flux boundary conditions are implemented using the bounce-back method (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017).

The initial conditions of the computational domain are

\begin{align} \tilde {\chi }(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}, \tilde {t}=0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\leqslant 2\tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {z}\leqslant \tilde {h}_0\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde {\chi }(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}, \tilde {t}=0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\leqslant 2\tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {z}\leqslant \tilde {h}_0\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}, \end{align}

These conditions align with the schematic of the dual-stage release experiment shown in figure 2. The initial and boundary conditions extend the methods used in Adekanye et al. (Reference Adekanye, Khan, Burns, McCaffrey, Geier, Schönherr and Dorrell2022) to multistage releases. Adekanye et al. (Reference Adekanye, Khan, Burns, McCaffrey, Geier, Schönherr and Dorrell2022) validate LBM models of single-stage releases against experimental data. Therefore, we expect that the initial and boundary conditions will provide sufficient accuracy to capture the dynamics of pulsed flows.

For the simulations of Cases 28–33 two passive scalars distributions are added to the simulation,

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P1}}$

and

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P1}}$

and

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P2}}$

, which simulate the advection–diffusion of two scalar fields

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P2}}$

, which simulate the advection–diffusion of two scalar fields

![]() $\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}$

and

$\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}$

and

![]() $\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}$

. The passive scalars are used to track the propagation and mixing of each release of dense material separately. The boundary conditions applied to the advection–diffusion simulations for

$\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}$

. The passive scalars are used to track the propagation and mixing of each release of dense material separately. The boundary conditions applied to the advection–diffusion simulations for

![]() $\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}$

and

$\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}$

and

![]() $\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}$

are the same as those applied to the

$\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}$

are the same as those applied to the

![]() $\tilde {\chi }$

scalar field in (2.27)–(2.29). The initial conditions for the passive scalar fields are defined such that

$\tilde {\chi }$

scalar field in (2.27)–(2.29). The initial conditions for the passive scalar fields are defined such that

![]() $\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}=1$

in the first lock and is zero elsewhere, while

$\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}=1$

in the first lock and is zero elsewhere, while

![]() $\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}=1$

in the second lock and is zero elsewhere,

$\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}=1$

in the second lock and is zero elsewhere,

\begin{align} \tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}, \tilde {t}=0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\leqslant 2\tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {x}\gt \tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {z}\leqslant \tilde {h}_0\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}, \tilde {t}=0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\leqslant 2\tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {x}\gt \tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {z}\leqslant \tilde {h}_0\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}, \tilde {t}=0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\leqslant \tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {z}\leqslant \tilde {h}_0\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}(\tilde {\boldsymbol{x}}, \tilde {t}=0) =& \begin{cases} 1 \quad & \text{if} \quad \tilde {x}\leqslant \tilde {x}_0 \land \tilde {z}\leqslant \tilde {h}_0\\ 0 \quad & \text{otherwise} \end{cases}. \end{align}

The passive scalars track the mixing of both pulses and can be used to determine the provenance of dense material at any time after the release of the lock gates.

Both the

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P1}}$

and

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P1}}$

and

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P2}}$

are one-way coupled to the

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}^{{P2}}$

are one-way coupled to the

![]() $f_{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution, so they are advected by the numerically calculated flow. The passive scalar distributions are solved for in an identical fashion to the two-way coupled distribution

$f_{\textit{ijk}}$

distribution, so they are advected by the numerically calculated flow. The passive scalar distributions are solved for in an identical fashion to the two-way coupled distribution

![]() $\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

, using (2.18). As the Peclet number (

$\varPhi _{\textit{ijk}}$

, using (2.18). As the Peclet number (

![]() $ \textit{Pe}=\textit{Re}_{{b}} Sc$

) is large (

$ \textit{Pe}=\textit{Re}_{{b}} Sc$

) is large (

![]() $\textit{Pe} \approx 6000$

), we assume the impact of the diffusion term in (2.6) is negligible, hence

$\textit{Pe} \approx 6000$

), we assume the impact of the diffusion term in (2.6) is negligible, hence

![]() $\tilde {\chi }(\boldsymbol{x},t)\approx\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}(\boldsymbol{x},t)+\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

.

$\tilde {\chi }(\boldsymbol{x},t)\approx\tilde {\chi }^{{P1}}(\boldsymbol{x},t)+\tilde {\chi }^{{P2}}(\boldsymbol{x},t)$

.

3. Results

3.1. Physical experiments

The front location of the gravity currents in Cases 13–18 and Cases 25–27 are presented in figure 5(a) and figure 5(b), respectively. The lock-exchange currents in Cases 13–18 have a fractional depth of release of

![]() $h_0/L_3 =0.2$

and delay times

$h_0/L_3 =0.2$

and delay times

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} \in [0.25,42.61]$

. Cases 25–27 have a fractional depth of release of

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} \in [0.25,42.61]$

. Cases 25–27 have a fractional depth of release of

![]() $h_0/L_3 =0.5$

and delay times

$h_0/L_3 =0.5$

and delay times

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} \in [0.21,10.15]$

. The solid curves in figure 5 correspond to the front location of the current produced by the release of the first lock-gate, while the dashed lines track the front of the second pulse. When the pulses merge the dashed curve merges with the solid curve from the merge time

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}} \in [0.21,10.15]$

. The solid curves in figure 5 correspond to the front location of the current produced by the release of the first lock-gate, while the dashed lines track the front of the second pulse. When the pulses merge the dashed curve merges with the solid curve from the merge time

![]() $\tilde {t}_{{M}}$

onwards. We observe a maximum variance in measured front location of

$\tilde {t}_{{M}}$

onwards. We observe a maximum variance in measured front location of

![]() $\sigma ^2=0.19x_0$

across four repeats of physical experiments of Case 13.

$\sigma ^2=0.19x_0$

across four repeats of physical experiments of Case 13.

Figure 5. (a) Plots of front location of first pulse (

![]() $x_{\!{f}}^1$

) in physical experiments (Exp) for

$x_{\!{f}}^1$

) in physical experiments (Exp) for

![]() $h_0/L_3 =0.2$

, Cases 13–18. (b) Plots of front location of first pulse (

$h_0/L_3 =0.2$

, Cases 13–18. (b) Plots of front location of first pulse (

![]() $x_{\!{f}}^1$

) in physical experiments for

$x_{\!{f}}^1$

) in physical experiments for

![]() $h_0/L_3 =0.5$

Cases 25–27. (c) Plots of front location in physical experiments of Cases 13–18 relative to Case 13 (

$h_0/L_3 =0.5$

Cases 25–27. (c) Plots of front location in physical experiments of Cases 13–18 relative to Case 13 (

![]() $\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

). (d) Plots of front location in physical experiments of Cases 25–27 relative to Case 25 (

$\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

). (d) Plots of front location in physical experiments of Cases 25–27 relative to Case 25 (

![]() $\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

). The solid curves correspond to the front location of the current produced by the release of the first lock-gate, while the dashed lines track the front of the second pulse.

$\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

). The solid curves correspond to the front location of the current produced by the release of the first lock-gate, while the dashed lines track the front of the second pulse.

The results for Cases 13 and 25, where

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\approx 0$

, provide baselines against which to measure the impact of varying

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\approx 0$

, provide baselines against which to measure the impact of varying

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. Cases 13 and 25 are single stage releases of a lock with dimensions

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}$

. Cases 13 and 25 are single stage releases of a lock with dimensions

![]() $2\tilde {x}_0\times \tilde {h}_0$

. Within the slumping phase, where

$2\tilde {x}_0\times \tilde {h}_0$

. Within the slumping phase, where

![]() $\tilde {x}_{{f}}\propto \tilde {t}$

, the current propagates with a buoyancy Froude number

$\tilde {x}_{{f}}\propto \tilde {t}$

, the current propagates with a buoyancy Froude number

![]() $ (\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=u_{\!{f}}/U_{{b}} )$

of

$ (\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=u_{\!{f}}/U_{{b}} )$

of

![]() $\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=0.51$

in Case 13, and

$\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=0.51$

in Case 13, and

![]() $\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=0.55$

in Case 25. This value is calculated by taking the mean velocity of the front for

$\textit{Fr}_{{b}}=0.55$

in Case 25. This value is calculated by taking the mean velocity of the front for

![]() $\tilde {t}\leqslant 8$

. After exiting the slumping phase the single stage release currents transition through the inertial phase and into the viscous phase. This is demonstrated in figure 5(a,b), where we observe the the current front locations briefly scaling like

$\tilde {t}\leqslant 8$

. After exiting the slumping phase the single stage release currents transition through the inertial phase and into the viscous phase. This is demonstrated in figure 5(a,b), where we observe the the current front locations briefly scaling like

![]() $\bar {x}_{{f}} \propto \tilde {t}^{2/3}$

, before scaling like

$\bar {x}_{{f}} \propto \tilde {t}^{2/3}$

, before scaling like

![]() $\bar {x}_{{f}} \propto \tilde {t}^{1/5}$

at later times.

$\bar {x}_{{f}} \propto \tilde {t}^{1/5}$

at later times.

In Cases 14–18, where there is a delay between the release of the first and second lock, the current initially propagates as a single release of a lock with dimensions

![]() $\tilde {x}_0\times \tilde {h}_0$

. The release of the second lock gate generates a dense intrusion into the leading gravity current. The pulses ultimately merge to form a unified front, as seen in figure 1. The merging time corresponds to an inflection point in the solid curve tracking the front location of the leading current. This is due to the acceleration of the front relative to its velocity immediately prior to the time of merging. The same trends are observed in Cases 25–27, where Case 25 is the baseline case

$\tilde {x}_0\times \tilde {h}_0$

. The release of the second lock gate generates a dense intrusion into the leading gravity current. The pulses ultimately merge to form a unified front, as seen in figure 1. The merging time corresponds to an inflection point in the solid curve tracking the front location of the leading current. This is due to the acceleration of the front relative to its velocity immediately prior to the time of merging. The same trends are observed in Cases 25–27, where Case 25 is the baseline case

![]() $(\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=0.25)$

against which Cases 26 and 27 are compared. Although both lock gates in Cases 13 and 25 are released simultaneously, there is still a non-zero merging time due to the transit time for the downstream buoyancy-flux in the inner region of the body to transport dense material to the head of the current.

$(\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=0.25)$

against which Cases 26 and 27 are compared. Although both lock gates in Cases 13 and 25 are released simultaneously, there is still a non-zero merging time due to the transit time for the downstream buoyancy-flux in the inner region of the body to transport dense material to the head of the current.

The findings here are best illustrated through plots of the relative front location of each pulsed current

![]() $(\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\gt 0)$

compared with a single release of an equal volume of dense fluid, i.e. the

$(\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\gt 0)$

compared with a single release of an equal volume of dense fluid, i.e. the

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\approx 0$

case with equivalent parameters. The relative displacement between the front of a single and pulsed release is defined as

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\approx 0$

case with equivalent parameters. The relative displacement between the front of a single and pulsed release is defined as

Plots of relative front location

![]() $(\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}})$

against time are presented in figures 5(c) and 5(d) for Cases 13–18 and Cases 25–27, respectively. These are plots of front location in a frame of reference moving with the front of the single release currents.

$(\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}})$

against time are presented in figures 5(c) and 5(d) for Cases 13–18 and Cases 25–27, respectively. These are plots of front location in a frame of reference moving with the front of the single release currents.

The same trends are observed in both sets of results. For the benchmark cases, Cases 13 and 25 where

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\approx 0$

, the

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\approx 0$

, the

![]() $\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

curve is identically zero for all

$\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

curve is identically zero for all

![]() $\tilde {t}$

by definition. Several clear trends emerge when comparing the front position of pulsed currents with their respective benchmarks. At early times the relative front location is negative,

$\tilde {t}$

by definition. Several clear trends emerge when comparing the front position of pulsed currents with their respective benchmarks. At early times the relative front location is negative,

![]() $\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}\lt 0$

. This distance continues to grow until the merge time of each pulsed current. At the merge time there is an inflection point in the

$\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}\lt 0$

. This distance continues to grow until the merge time of each pulsed current. At the merge time there is an inflection point in the

![]() $\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

curves, and the unified fronts of the pulsed gravity currents accelerate relative to the front of the single release current. The relative acceleration of the pulsed flows does not continue indefinitely, ultimately the acceleration slows and the relative front position plateaus at a constant value. At late times the unified front propagates under the viscous scaling law,

$\Delta \tilde {x}^1_{{f}}$

curves, and the unified fronts of the pulsed gravity currents accelerate relative to the front of the single release current. The relative acceleration of the pulsed flows does not continue indefinitely, ultimately the acceleration slows and the relative front position plateaus at a constant value. At late times the unified front propagates under the viscous scaling law,

![]() $\bar {x}_{{f}} \propto \tilde {t}^{1/5}$

.

$\bar {x}_{{f}} \propto \tilde {t}^{1/5}$

.

The key result is that for pulsed currents with relatively short delay times – specifically

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\in \{5.26,11.02\}$

in figure 5(c), and

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}\in \{5.26,11.02\}$

in figure 5(c), and

![]() $\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=5.14$

in figure 5(d) – the front of the pulsed current accelerates beyond the velocity of a single release current and plateaus at a value

$\tilde {t}_{\textit{re}}=5.14$

in figure 5(d) – the front of the pulsed current accelerates beyond the velocity of a single release current and plateaus at a value