Introduction

Dinoflagellates are key components of marine ecosystems (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Zhang, Lu, Fu, Lu, Zhang and Gao2025), with over 2400 species recorded (Gómez, Reference Gómez and Rao2020; Hoppenrath et al., Reference Hoppenrath, Murray, Chomérat and Horiguchi2014). Approximately half of them are primary photosynthetic producers, while the rest are mixotrophic, combining photosynthesis with the ingestion of secondary producer prey. Some species are even endosymbionts of marine animals, whereas others are strictly predatory or parasitic (Janouškovec et al., Reference Janouškovec, Gavelis, Burki, Dinh, Bachvaroff, Gornik, Bright, Imanian, Strom, Delwiche, Waller, Fensome, Leander, Rohwer and Saldarriaga2017; Kwok et al., Reference Kwok, Chan and Wong2023). Most dinoflagellates exhibit planktonic habits (Gómez Reference Gómez2012; Hoppenrath and Leander Reference Hoppenrath and Leander2010), and fewer than 10% are associated with benthic habitats (Hoppenrath et al., Reference Hoppenrath, Murray, Chomérat and Horiguchi2014; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hoppenrath and Saldarriaga2008). Morphologically, dinoflagellates are divided into armoured dinoflagellates, which possess one or more thecal plates covering their cells, and unarmoured dinoflagellates that lack such plates (Hoppenrath and Leander Reference Hoppenrath and Leander2010; Orr et al., Reference Orr, Murray, Stüken, Rhodes and Jakobsen2012; Taylor Reference Taylor, Steidinger, Landsberg, Tomas and Vargo2004; Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hoppenrath and Saldarriaga2008). Benthic dinoflagellates have evolved diverse morphologies, allowing them to colonize a wide range of habitats such as sandy sediments, intertidal and subtidal areas, tide pools, macroalgal surfaces, seagrasses, and epilithic and artificial substrates (Hoppenrath et al., Reference Hoppenrath, Murray, Chomérat and Horiguchi2014; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Zou, Zheng, Y and Lu2022).

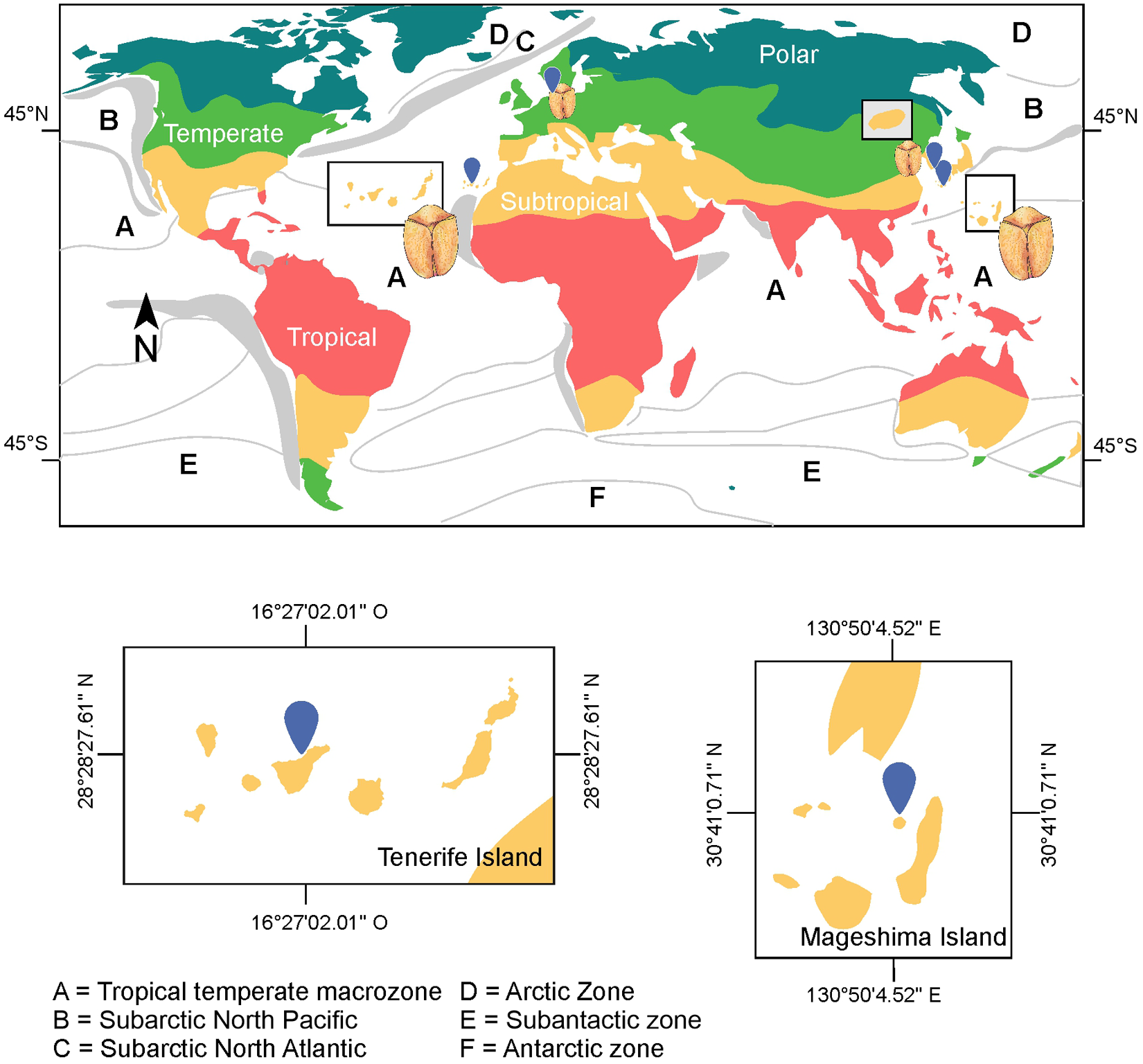

The ideal habitats and ecological niches for benthic dinoflagellates are predominantly found in tropical and subtropical zones (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Hoppenrath and Saldarriaga2008). Notably, several studies have reported their presence on tropical and subtropical islands (Biessy et al., Reference Biessy, Wood, Chinain, Roué and Smith2021; Chinain et al., Reference Chinain, Darius, Gatti and Roué2016; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Frontalini, Martins and Lee2016; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Fraga, Ramilo, Rial, Figueroa, Riobó and Bravo2017; Xie et al., Reference Xie, Zou, Zheng, Y and Lu2022), with some island endemic species. Such is the case for Amphidinium yuroogurrum (Murray and Patterson Reference Murray and Patterson2002), Amphidinium cupulatisquama (Tamura et al., Reference Tamura, Takano and Horiguchi2009), Spiniferodinium palauense (Horiguchi et al., Reference Horiguchi, Hayashi, Kudo and Hara2011), and Bispinodinium angelaceum (Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013).

The Canary Islands provide favourable environmental conditions for benthic dinoflagellates, characterized by a thermally stable marine environment throughout the year (David et al., Reference David, Laza-Martínez, Rodríguez, Fraga and Orive2019), and low-biomass, very oligotrophic waters where nutrients are depleted in summer (Neuer et al., Reference Neuer, Cianca, Helmke, Freudenthal, Davenport, Meggers, Michaela Knoll, Santana-Casiano, González-Davila, Rueda and Llinás2007). In this region, new toxic and non-toxic species of Coolia and Gambierdiscus have been described (Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Penna, Bianconni, Paz and Zapata2008; Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Rodríguez, Caillaud, Diogene, Raho and Zapata2011; Fraga and Rodríguez Reference Fraga and Rodríguez2014), as well as other warm water genera, such as Ostreopsis, Prorocentrum, Amphidinium, Sinophysis, and Vulcanodinium (Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Rodríguez, Ramilo and Afonso-Carrillo2020; David et al., Reference David, Laza-Martínez, Rodríguez, Fraga and Orive2019; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Fraga, Ramilo, Rial, Figueroa, Riobó and Bravo2017; Tudó et al., Reference Tudó, Gaiani, Rey Varela, Tsumuraya, Andree, Fernández-Tejedor, Campàs and Diogène2020).

However, research has mainly focused on HABs and toxin-producers’ dinoflagellates, including new records of Gambierdiscus (Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Rodríguez, Ramilo and Afonso-Carrillo2020; Tudó et al., Reference Tudó, Gaiani, Rey Varela, Tsumuraya, Andree, Fernández-Tejedor, Campàs and Diogène2020). In particular, the potential expansion of Gambierdiscus, which produces toxins associated with ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP), has positioned the Canary Islands as a ‘hotspot for ciguatera’, making this genus a major focus of study (David et al., Reference David, Laza-Martínez, Rodríguez, Fraga and Orive2019; Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Penna, Bianconni, Paz and Zapata2008; Fraga and Rodríguez Reference Fraga and Rodríguez2014; Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Rodríguez, Caillaud, Diogene, Raho and Zapata2011; Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Fraga, Ramilo, Rial, Figueroa, Riobó and Bravo2017). This, however, resulted in a narrow understanding of benthic dinoflagellate dynamics in the Canary Islands, potentially jeopardizing our understanding of distribution patterns and habitats preferences. To address the gap in the knowledge regarding the biogeography of non-HAB benthic dinoflagellates in the Canary Islands, we sampled unexplored areas along the north coast of Tenerife to record new occurrences and expand understanding of benthic dinoflagellate biodiversity. Additionally, the identification of new species provides a foundation for future research on bioactive compounds and their biotechnological potential.

Here, we report our findings including some Amphidinium and important record on the rare B. angelaceum and discuss biogeographic and environmental factors associated with their occurrence.

Materials and methods

Sampling procedures

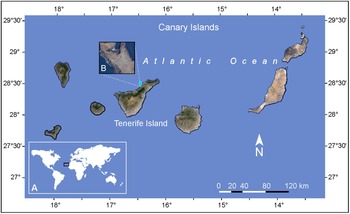

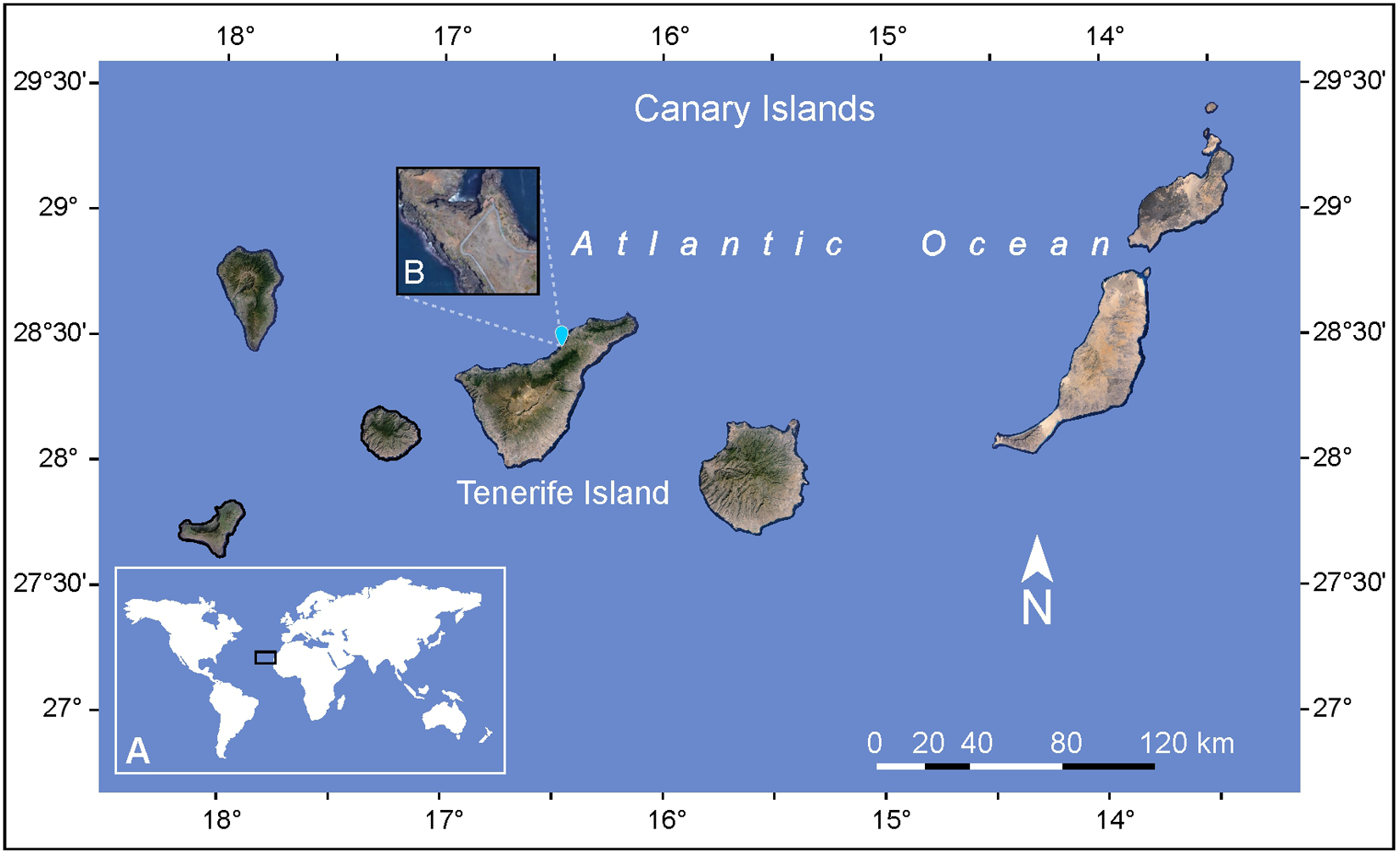

Two sediment samples were collected by snorkeling at a depth of 2 m during low tide in July 2023 from the sandy bottom of a tidal pool at Playa de Rojas, El Sauzal, Tenerife, Canary Island (28°28′27.18″N, 16°26′59.22″W) (Figure 1). The samples also contained macroalgae of the genera Padina and Dictyota, which were separated using a 16.5 cm stainless steel spatula (Chemglass Inc. 10034-424). The collected material, consisting of seawater, sediment, and macroalgae, was transferred into 1 L Nalgene bottles and transported in a cooler to the laboratory for further processing. Historical sea surface temperature (SST) data for the study area was obtained from the State Meteorological Agency (AEMET) based on the time series from 1981 to 2022, including records for the sampling day in July 2023. Marine and tide forecast for the same day were also retrieved from AEMET (2024). In addition to the historical data retrieved from AEMET, sea temperature and salinity were recorded in situ using a Tracer Pocket Tester (La Motte 1766).

Figure 1. (A) Geographical location of the Canary Archipelago in the East Atlantic Ocean. (B) Detailed view of the study area showing the sampling site on Tenerife Island.

In the laboratory, the collected material was filtered through a 100 µm mesh sieve to collect the benthic dinoflagellates. Subsequently, 500 mL of each sample were mixed with 500 mL of modified Guillard K medium (de Vera et al., Reference de Vera, Díaz Crespín, Hernández Daranas, Montalvão Looga, Lillsunde, Tammela, Perälä, Hongisto, Virtanen, Rischer, Muller, Norte, Fernández and Souto2018), supplemented with 6 mg L−1 of germanium oxide (IV) (GeO2) (Sigma-Aldrich, Sigma-Aldrich), to inhibit diatom growth, in 1 L Nalgene bottles. The samples were incubated for 24 h in a culture room under controlled conditions: temperature 20 ± 2ºC, 18:6 h light:dark photoperiod, and an irradiance of 25 ± 1 µmol photons m−2 s−1 provided by horizontally positioned fluorescent lamps (Osram Lumilux cool daylight L 58 W/865).

Isolation and culturing of B. Angelaceum cells

Two motile cells of B. angelaceum were isolated using a capillary micropipette under an inverted microscope (MOTIC® AE31E Binocular) in bright-field mode, equipped with a PL PH10×/0.25 (WD 4.1 mm) objective lens. Each cell was individually transferred to a flat-bottom 24-wells plate (Corning® Costar®) containing 1.5 mL of modified Guillard K medium adjusted to salinity of 35. The two isolated B. angelaceum cells were successfully divided, and clonal cultures were established as strains BpTF-1 and BpTF-2. These cultures were maintained under controlled conditions: 24 ± 2ºC temperature, 16:8 light:dark photoperiod, and irradiance of 35 ± 1 µmol photons m−2 s−1 using horizontal fluorescent illumination (Osram Lumilux cool daylight L 58 W/865).

Live B. angelaceum cells were monitored directly in the culture plate using an inverted microscope (MOTIC® AE31E Binocular) equipped with a Moticam 5 camera (5 MP resolution). Cell counts were performed every 3 days by scanning the entire well area to calculate the growth rate and the number of cell divisions per day from a single cell (Guillard, Reference Guillard and Stein1973; Guillard and Ryther Reference Guillard and Ryther1962) using the LH 20×/0.30 (WD 4.7 mm) objective lens. Micrographs and videos were recorded using a LWD PH40×/0.50 (WD 3.0 mm) objective lens. Measurements were performed on live cells photographed at random using the Motic Images Plus 3.0 and Imagenview software, with a fine focus precision adjustment of 2 µm.

Morphology and taxonomy

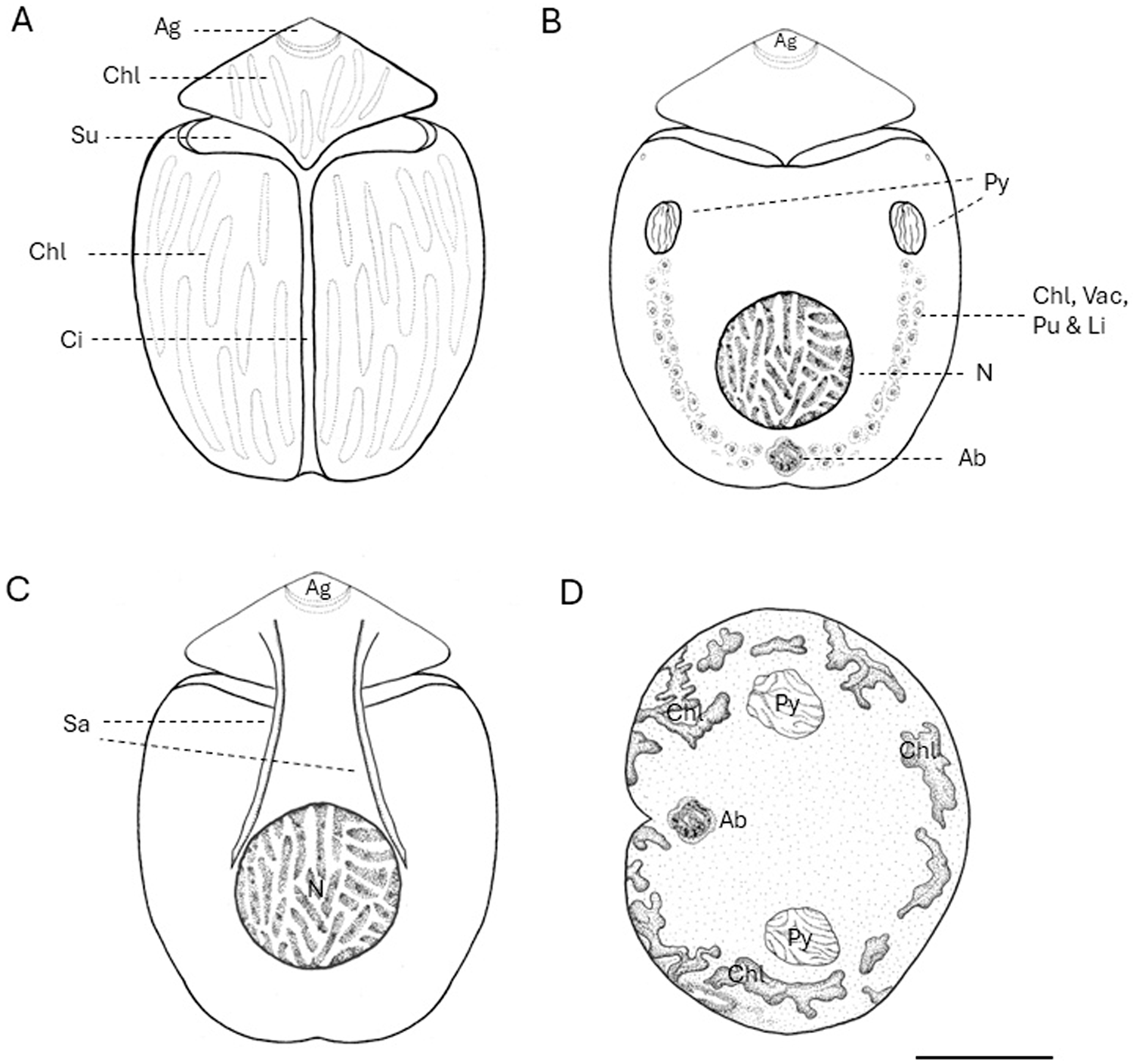

In this study, the morphological description of B. angelaceum is based on observations of living cells from strains BpTf-1 and BpTf-2. Morphological characterization was initially carried out following the guidelines for unarmored benthic dinoflagellates proposed by Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Flø Jørgensen, Daugbjerg and Rhodes2004) and Flø Jørgensen et al. (Reference Flø Jørgensen, Murray and Daugbjerg2004a, Reference Flø Jørgensen, Murray and Daugbjerg2004b) for the genus Amphidinium sensu stricto, and classified sensu lato according to Hoppenrath et al. (Reference Hoppenrath, Murray, Chomérat and Horiguchi2014). Under light microscopy (LM), we considered cell size and shape, the presence of irregular triangular or crescent-shaped epicones deflected to the left, and position of the sulcus, noting whether it is separated from or connected to the cingulum. The cells observed did not meet the taxonomic criteria for Amphidinium and were reclassified following Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) and Hoppenrath et al. (Reference Hoppenrath, Murray, Chomérat and Horiguchi2014). We determined the dorsoventral shape of the cells; measured the size of the epicone and hypocone, and calculated the ratio of the epicone to the total cell length. We also examined the proportion of the cingulum surrounding the cell, the shape of the apical groove, and the symmetry along the plane of the sulcus. In addition, we identified the position and shape of the nucleus. The maximum correspondence with B. angelaceum was established by the presence of the ‘spinoid apparatus’, which extends from just below the circular apical groove to a point near the nucleus, together with the characteristic shape of the chloroplasts and the presence of two pyrenoids located on either side of the hypocone.

Results and discussion

Morphological description

During a sampling campaign targeting benthic Amphidinium spp., we observed a dinoflagellate that did not match known morphological descriptions of the genus Amphidinium. In this study, we report the presence of the benthic dinoflagellate Bispinodinum angelaceum in the intertidal zone in Tenerife, Canary Islands. To the best of our knowledge, this species has only been previously recorded in Mageshima Island (Kahoshima Prefecture, Japan), Jeju Island (South Korea), and the Wadden Sea (Germany) (Kang and Lee Reference Kang and Lee2018; Reñé et al., Reference Reñé, Timoneda, Khodami, López-García, Martinez and Hoppenrath2023; Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013).

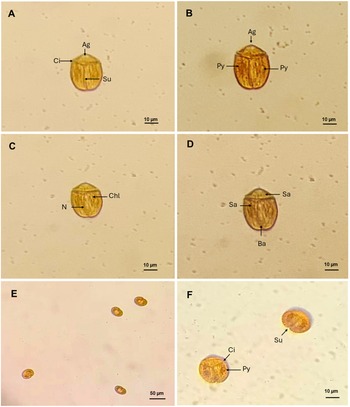

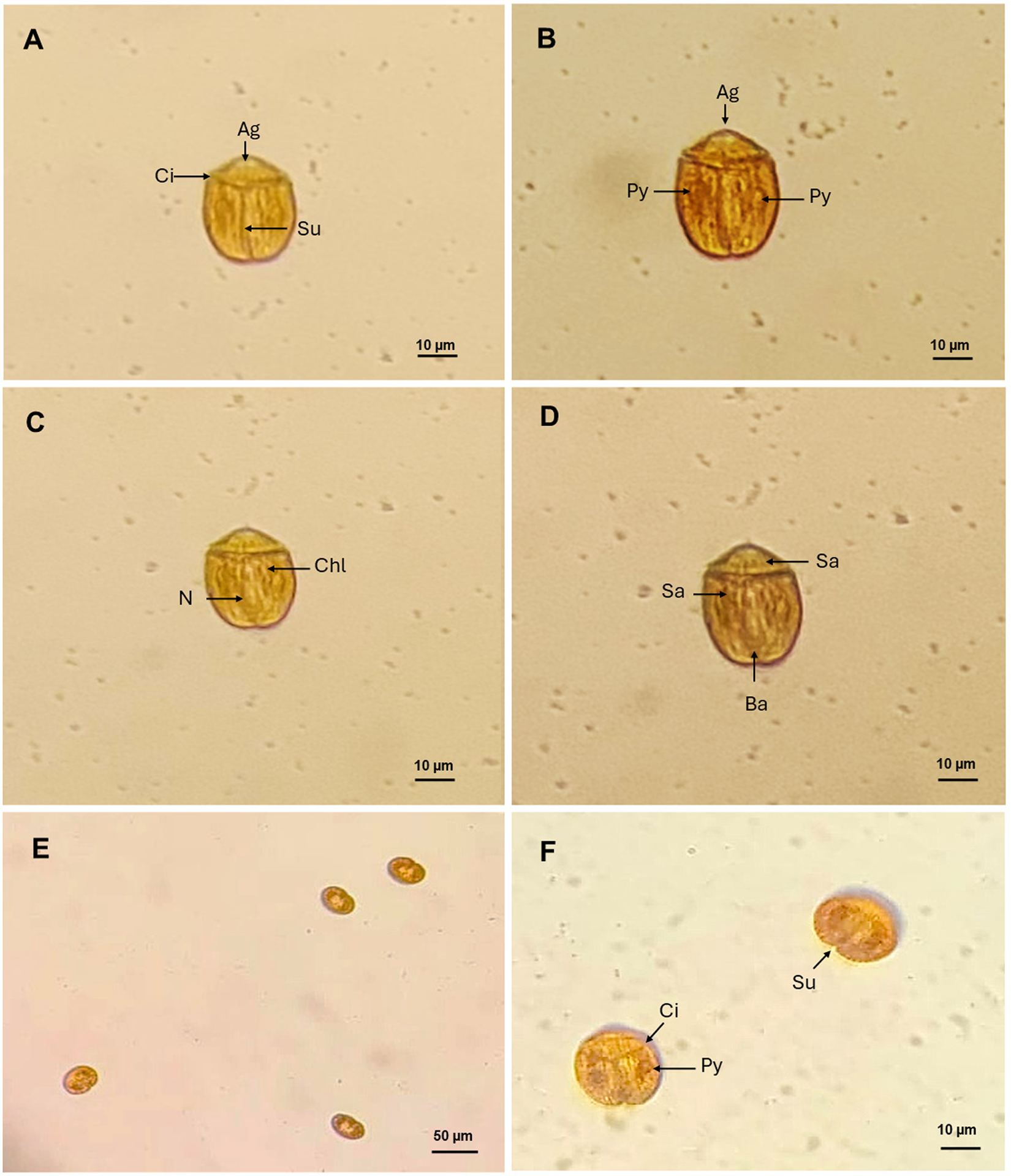

B. angelaceum, isolated in Tenerife, is a photosynthetic, unarmoured dinoflagellate characterized by its brownish-yellow coloration. Cells are oblong in ventral view (Figure 2A) and dorsoventrally flattened. Cell length ranges from 34.12 to 43.16 µm (mean 38.64 ± 2.76, n = 6), and width from 26.30 to 34.21 µm (mean 30.25 ± 2.56, n = 6).

Figure 2. Light microscopy images of Bispinodinium angelaceum. (A) Ventral view of vegetative cells showing the cingulum (Ci) and sulcus (Su). (B) Ventral view (arrow) shows the apical groove (Ag) in the epicone, and two pyrenoid (Py) located on the left and right sides of the hypocone. (C) Dorsal view; arrows indicate chloroplast lobes (Chl) and the nucleus (N). (D) Dorsal view of a vegetative cell; arrow shows the spinoid apparatus (Sa) and accumulation body (Ab). (E–F) Non-motile cells observed standing upright on antapical position. Scale bar: 10 µm.

In this study, the cells are divided longitudinally, with a short epicone positioned above the cingulum, which is located approximately one-third of the total cell length (ratio 0.29–0.34). The epicone bears a circular apical groove reminiscent of an angels halo characteristic of the species as described in Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013). The hypocone is approximately twice as the length of the epicone, and the sulcus is straight and narrow, extending to the antapex and slightly widening toward its anterior end. The sulcus is aligned with the transverse flagellar beat, resembling wings; this position of the sulcus confers axial symmetry along its plane, and the cingulum completely encircles the cell, delineating lobed chloroplasts (Figure 2B). Isolated cells present in dorsal view, two pyrenoids on the left and right sides of the cell, with the nucleus centrally located. These morphological characters are consistent with the original description of B. angelaceum by Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013; Figure 2C). We observed an organelle like the spinoid apparatus, which surrounds the nucleus and connects the pyrenoids in a U-shape. At the end of the hypocone, an accumulation body is also observed (Figure 2D).

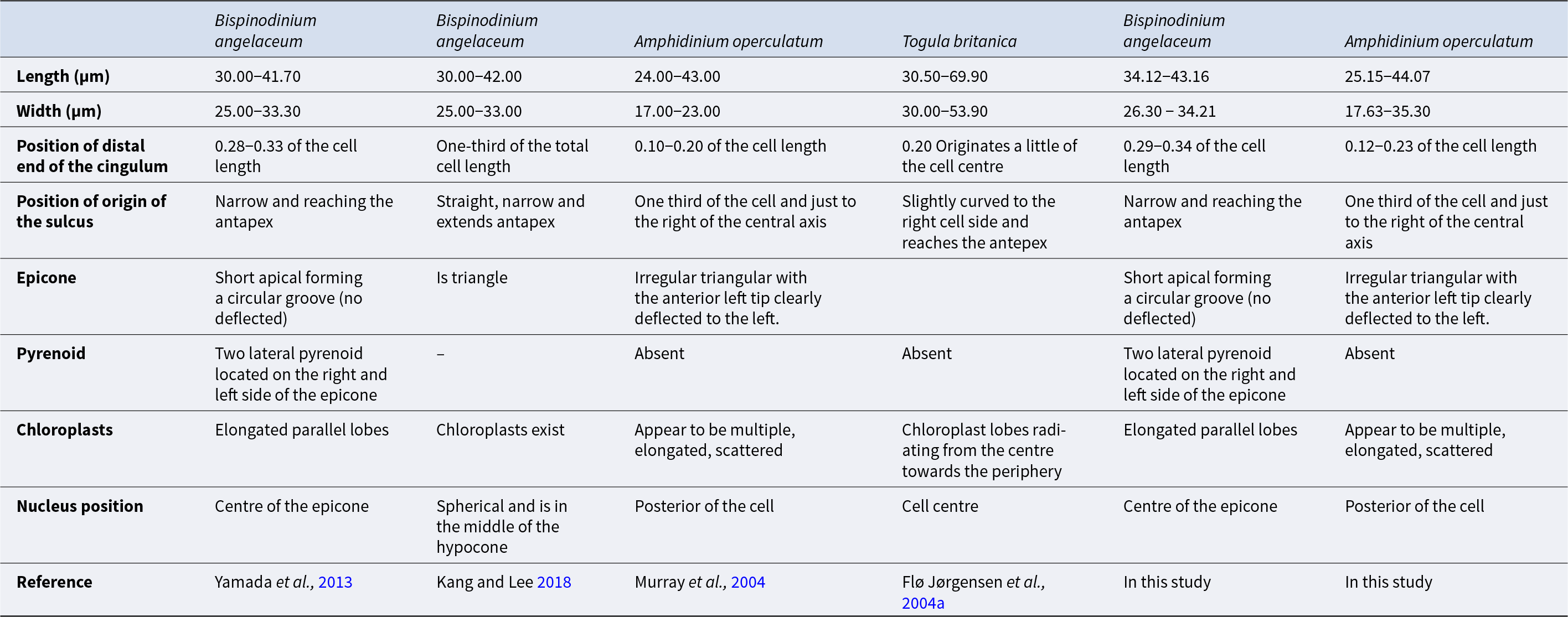

B. angelaceum was originally described with cell sizes of 30.00 to 42.00 µm in length and 25.00–33.30 µm in width (Kang and Lee Reference Kang and Lee2018; Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013), whereas the cells described in this study were slightly larger, ranging from 34.12 to 43.16 µm in length and 26.30 to 34.21 µm in width. (Table 1). The original description of B. angelaceum by Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) reported a cingulum ratio of approximately one-third of the total cell length (0.28–0.33), which was later confirmed in Korean specimens by Kang and Lee (Reference Kang and Lee2018). In Tenerife specimens, the cingulum ratio was similar (0.29–0.34) (Table 1).

Table 1. Morphological description of Bispinodinium angelaceum and the differences between the discussed species

Without description.

These slight differences in cell size and proportions are likely due to methodological variation, as measurements and observations of B. angelaceum in our study were conducted exclusively in live cells, while in the original description a more thorough assessment was conducted via Scanning and Transmission Electron Microscopy. Nonetheless, measurements are comparable, supporting the use of living cells for accurate measurement of B. angelaceum cells.

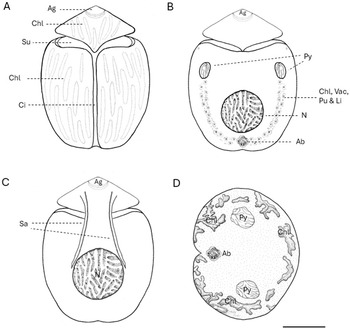

Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) reported that the cingulum of B. angelaceum is axially symmetrical and the cell body remains undeflected, unlike most benthic unarmored dinoflagellates, which are slightly displaced or curved (Murray et al., Reference Murray, Flø Jørgensen, Daugbjerg and Rhodes2004; Flø Jørgensen et al., Reference Flø Jørgensen, Murray and Daugbjerg2004a, Reference Flø Jørgensen, Murray and Daugbjerg2004b; Hoppenrath et al., Reference Hoppenrath, Murray, Chomérat and Horiguchi2014). Cells in this study exhibited the same axial symmetry. Morphological identification of B. angelaceum relies primarily on the epicone shape and its central position (Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013), distinguishing B. angelaceum from the left-deflected epicone of Amphidinium spp., and the tongue-like form of Togula spp. (Flø Jørgensen et al., Reference Flø Jørgensen, Murray and Daugbjerg2004b; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Flø Jørgensen, Daugbjerg and Rhodes2004; Figure 3). The nucleus position and presence of a pyrenoid were also key diagnostic characters, confirming that Tenerife cells match the description of B. angelaceum (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Line drawings of Bispinodinum angelaceum, created to scala based on original light micrographs from Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) and from this study. (A) Ventral view showing the apical groove (Ag), chloroplasts (Chl), sulcus (Su), and cingulum (Ci). (B) Dorsal view showing pyrenoids (Py) in the epicone; a U-shaped belt composed of various organelles is apparent under light microscopy, including chloroplasts (Chl), vacuoles (Vac), pusule (Pu), and lipid droplets (Li); nucleus (N) and accumulation body (Ab) are also visible. (C) Dorsal view showing a fiber of spinoid apparatus (Sa). (D) Non-motile cell stands standing upright on tits antapical end. Scale bar: 10 µm.

In contrast, Kang and Lee (Reference Kang and Lee2018) did not describe the two pyrenoids and the spinoid apparatus, and chloroplasts were only noted without details of shape or arrangement (Table 1). These structures were probably not mentioned in the micrograph due to their observations being based on fixed cells. These structures may have been disturbed or collapsed during the fixation process, making their identification difficult through microscopic techniques. These reflect the fragile nature of unarmoured dinoflagellates and their susceptibility to structural damage during sampling, fixation, and observation under a microscope (Gómez et al., Reference Gómez, López-García, Takayama and Moreira2015; Lv et al., Reference Lv, Zhen, Cen, Lu, Li, Liu, Chi, Yuan and Wang2025).

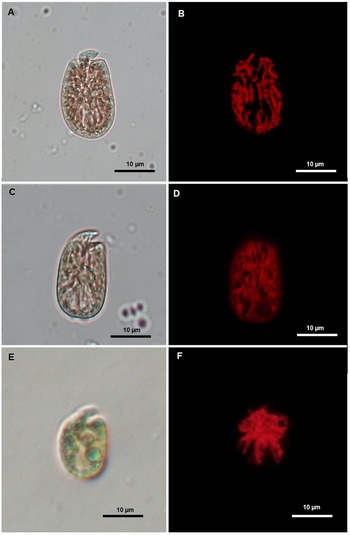

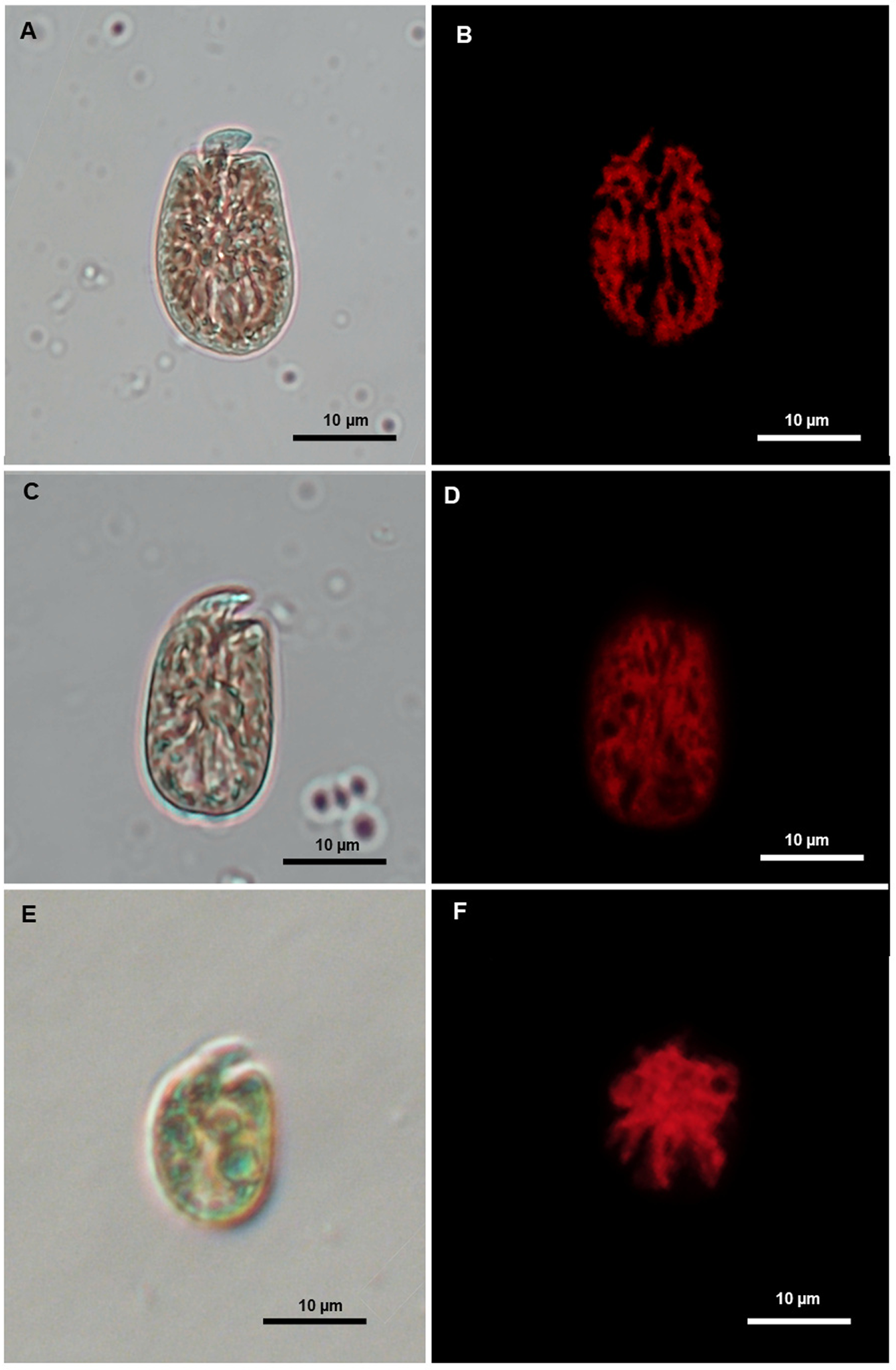

Several behavioural differences were observed in B. angelaceum from Tenerife when compared with previously isolated unarmoured benthic dinoflagellate strains identified morphologically as Amphidinium operculatum, Amphidinium operculatum var. gibbosum, and Amphidinium massartii (Figure 4). One notable feature was the increased number of motile cells during the light/dark cycle transition, along with a characteristic zigzag-shaped swimming behaviour, both of which are consistent with the observations reported byby Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) in the culture of B. angelaceum (Supplementary materials Video S1).

Figure 4. Light microscopy images (left) and corresponding epifluorescence microscopy images (right) showing the morphology and chloroplast of Amphidinium species isolated in Tenerife during the sampling campaign. (A–B) A. Operculatum. (B–C) A. Operculatum var. gibbosum. (D–E) A. Massarti.

To date, B. angelaceum has been successfully cultivated using Daigo’s IMK medium under 50 µmol photons m−2 s−1 irradiance (Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) and using modified Guillard K medium under 35 ± 1 µmol photons m−2 s−1 (this study). In both cases, temperature and light:dark cycle conditions were similar, suggesting that the variations in culture medium and irradiance do not significantly affect the morphology of B. angelaceum. Furthermore, we monitored the growth of B. angelaceum for 19 days, reporting for the first time a growth rate of 0.26 div/day−1 and a number of divisions per day of 0.38.

During cell division, non-motile cells of B. angelaceum were observed standing upright on their antapical end on the flat bottom culture plate, exhibiting an ovoid form (Figure 2E). Prior to division, cells became wider and displayed a rounded hypocone and an oval epicone (Figure 2F). However, no formation or division of a new epicone was observed. These morphological changes are likely associated with division and reproduction and resemble those described in other benthic unarmoured dinoflagellates that exhibit sedentary stages in culture, such Togula and Amphidinium, where cell shape plasticity and antapical initiation of division have been documented (Flø Jørgensen et al., Reference Flø Jørgensen, Murray and Daugbjerg2004b; Murray and Patterson Reference Murray and Patterson2002).

Morphological features of both armoured and unarmoured dinoflagellates are known to be influenced by environmental conditions, including light intensity, salinity, temperature, depth, and nutrient availability, which may alter swimming behaviour, cell size, life cycle, and even trophic strategies (Jeong et al., Reference Jeong, Lee, Yoo, Kang, Song, Kim, Seong, Kim and Potvin2018; Karafas et al., Reference Karafas, Teng, Leaw and Alves-de-souza2017; Murray and Patterson Reference Murray and Patterson2002; Smayda Reference Smayda2010). In particular, unarmoured species can undergo rapid shape changes in response to light intensity d (Escobar-Morales and Hernández-Becerril Reference Escobar-Morales and Hernández-Becerril2015; Larsen Reference Larsen, Sar, Ferrario and Reguera2002). In our observations, B. angelaceum exhibited considerable plasticity in both motile and non-motile cells, suggesting possible metabolic movement during specific life stages, as also described in some Amphidinium species (Gómez and Artigas Reference Gómez and Artigas2014; Murray and Patterson Reference Murray and Patterson2002). Importantly, no morphological changes were observed during the isolation process or during microscopic observations for cell counting. Unfortunately, the strains were lost during maintenance, which prevented us from obtaining sufficient material for gene sequencing and, consequently, from comparing our results with the molecular data reported in previous studies.

Habitat description

B. angelaceum was collected from a tide pool at Playa de Rojas, El Sauzal, Tenerife, Canary Islands, characterized by rugged, rocky formations, and a coarse-grained sandy substrate (García-Casanova Reference García-Casanova and Acosta-Dorta2021). The pool is exposed to direct sunlight in the morning and shaded in the afternoon due to the adjacent coastal cliff. Water temperature at the time of sampling was 20.5 °C, salinity was 36, and tidal amplitude ranged from 0.34 to 2.28 m (AEMET, 2024; www.tide-forecast.com). Average SST in the Canary Islands is 20.5 °C, with anomalies of +0.4 °C based on the 1981–2022 time series (AEMET, 2024; Gutiérrez-Guerra et al., Reference Gutiérrez-Guerra, Pérez-Hernández and Vélez-Belchí2024).

The northern region of Tenerife experiences prolonged periods of solar exposure, although solar radiation varies throughout the day due to cloud cover (Dorta Reference Dorta1996; Font Reference Font1956). Near the B. angelaceum isolation site, the photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) has been evaluated with irradiance levels ranging from 150 to 500 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 (Domínguez-Álvarez et al., Reference Domínguez-Álvarez, Rico and Gil-Rodríguez2011). These values are consistent with the irradiance range reported by Yamada et al. (Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013) for B. angelaceum, who estimated that 250 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at the depth of its habitat representing optimal conditions for its distribution.

Compared to the original record from Mageshima Island, Japan, where B. angelaceum was collected at 36 m depth, in this study it was collected at 2 m; however, the hydrographic conditions, including temperature (18–21 °C) and high-water clarity, are comparable (Yamada et al., Reference Yamada, Terada, Tanaka and Horiguchi2013). Both islands are seasonally influenced by regional oceanographic dynamics that present oligotrophic conditions: the Canary Island by the eastern boundary current of the North Atlantic subtropical gyre (Neuer et al., Reference Neuer, Freudenthal, Davenport, Llinás and Rueda2002, Reference Neuer, Cianca, Helmke, Freudenthal, Davenport, Meggers, Michaela Knoll, Santana-Casiano, González-Davila, Rueda and Llinás2007) and the Mageshima Island by the Osumi and Kuroshio currents (Ichinomiya et al., Reference Ichinomiya, Nomiya, Komorita, Kobari, Kume, Habano, Arita and Makino2022), which shape the coastal hydrography of southern Japan (Maeda et al., Reference Maeda, Yamashiro and Sakurai1993). Hydrographic variability in the Canary Islands contributes to spatial and temporal structuring of planktonic communities (Arístegui et al., Reference Arístegui, Barton, Álvarez-Salgado, Santos, Figueiras, Kifani, Hernández-León, Mason, Machú and Demarcq2009; (Ichinomiya et al., Reference Ichinomiya, Nomiya, Komorita, Kobari, Kume, Habano, Arita and Makino2022), and temperature is a primary driver of seasonal fluctuations in benthic dinoflagellate communities, including taxa associated with Gambierdiscus spp. (Bravo et al., Reference Bravo, Rodríguez, Ramilo and Afonso-Carrillo2020; Tudó et al., Reference Tudó, Gaiani, Rey Varela, Tsumuraya, Andree, Fernández-Tejedor, Campàs and Diogène2020).

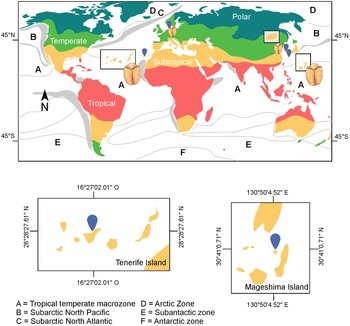

According to Taylor’s biogeographic framework for dinoflagellates based on SST, B. angelaceum occurs at the intersection of two major biogeographic zones: (a) the tropical-temperate macrozone and (b) the subarctic zones of the North Atlantic and North Pacific. This distribution is consistent with previous records from Hamduk Beach, Jeju Island, South Korea (33°32ʹ36.11ʺN, 26°40ʹ4.98ʺE) (Kang and Lee Reference Kang and Lee2018), and Wilhelmshaven, Germany (53°30′36ʺN; 8°07ʹ43ʺE) (Reñé et al., Reference Reñé, Timoneda, Khodami, López-García, Martinez and Hoppenrath2023; see Taylor Reference Taylor1987). Overall, available records suggest that this species is restricted to subtropical and temperate climatic regions (Köppen Reference Köppen1884; Figure 5).

Figure 5. Distribution of Bispinodinium angelaceum. Letters indicate major dinoflagellate biogeographic zones as proposed by Taylor (Reference Taylor1987). Colours represent macroclimatic zones; grey areas indicate regions of seasonal upwelling, and hatched areas denote zones of mixed oceanographic character.

The coastal zones of Tenerife harbour highly diverse habitats where new species of armoured benthic dinoflagellates have been described (David et al., Reference David, Laza-Martínez, Rodríguez, Fraga and Orive2019; Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Penna, Bianconni, Paz and Zapata2008; Fraga et al., Reference Fraga, Rodríguez, Caillaud, Diogene, Raho and Zapata2011; Fraga and Rodríguez Reference Fraga and Rodríguez2014) (Supplementary materials Figure S1). Our findings highlight the potential for additional discoveries of unarmoured benthic dinoflagellates in this region, though current sampling often targets economically important taxa usually related to HAB’s. Expanding sampling strategies is therefore necessary to improve our understanding of benthic dinoflagellate biodiversity, biogeography, and ecology.

Future studies should increase sampling efforts to detect new species and isolate B. angelaceum for molecular characterization to confirm its taxonomic status. Additionally, investigations into its chemical profile and biological activity are warranted. A better understanding of its ecological role, evolutionary relationships, and geographical distribution could provide valuable insights and potentially reveal new species within the genus Bispinodinium.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S002531542510074X.

Acknowledgements

L.J.F.-H. dedicates this work to the memory of Jeronimo Santiago Herrera Suarez (1930–2023). L.J.F.-H. thanks to Universidad de La Laguna for the support ‘Estancias cortas de profesorado y personal investigador de reconocido prestigio internacional’ programme (Plan propio de investigación 2023 incentivación de la actividad investigadora), and to CONAHCYT for the postdoctoral fellowship (project 319865 and Postdoctoral residence for Mexico 2022 (3) Programme CVU 337101). S.G.-D. acknowledges funds of María Zambrano Programme (Programme of Requalification of the Spanish University System from Spanish Ministry for Universities, ULL, Next-Generation EU Funds). The authors thank scientific illustrator Isis San Juan Flores for creating the drawing of Bispinodinium angelaceum.

Author contributions

Sampling and collection of material: L.J.F.-H., V.H.L. and S.G.-D.; Methods: L.J.F.-H. and S.G.-D.; Conceptualization, data curation & formal analysis: L.J.F.-H.; Financing & Project administration: J.J.F. and S.G.-D.; Original draft: L.J.F.-H. and S.G.-D.; Writing – review & editing: J.J.F., V.H.L. and S.G.-D. All authors approved the final version manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for- profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare none.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are contained within the article and its supplementary materials. Additional images and raw files can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.