In Iran, where religion is well embedded in the state and citizenry, same-sex sexual activity is punishable by death.Footnote 1 These criminalizing provisions of the penal code originate from Islamic law and interpretations of “Sharia principles” (Human Dignity Trust 2023). Interestingly, however, Iran legally authorizes and even subsidizes gender “reassignment” surgeries for transgender individuals (Jafari Reference Jafari2014; Javaheri Reference Javaheri2010). The same religious principles underlying the laws that condemn sexual orientation minorities to death permit those who do not identify with their birth-assigned sex to access medical care to affirm their gender expression.

While Iran does not embrace or otherwise protect transgender people (Jafari Reference Jafari2014), the legal differences raise important questions about how religion affects transgender rights. Several studies explore the connection between religion and sexual orientation rights (e.g., Asal et al. 2013; Hildebrandt et al. Reference Hildebrandt, Trudinger and Jackle2017; Knill and Preidel Reference Knill and Preidel2015), but empirical research on transgender-specific rights remains scarce. Therefore, this paper asks: how does religion affect countries’ protection of transgender rights? To answer this question, I provide a cross-national time-series analysis that examines the effects of religion depending on where and how it manifests within a country. More specifically, I distinguish between the presence of religion in state institutions versus society. This approach allows for a more nuanced investigation of the different avenues through which religion may influence a country’s laws (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015).

Overall, the analysis suggests that an increase in religion in the state or society is associated with fewer transgender rights. However, findings from models with societal measures are more consistently significant than those with state measures. The final model combines the significant state and societal variables for a head-to-head comparison. These results reveal that transgender rights are lower in countries with more religious populations and where policymakers more frequently consult religious organizations on policy issues.

Understanding how different aspects of religion affect these types of legal rights is important from both a scholarly and practical perspective. Though conventional wisdom may lead us to expect some of the findings, this article is among the first to formally provide robust evidence on a global scale for the relationship between religion and transgender rights. Disaggregating the complexities of this connection is a critical step towards furthering our academic understanding of the power religion holds over policy and can also help advocates better focus their strategies for pursuing rights advancements.

Religion and Rights

While difficult to define in a way that “encompasses all imaginable religious traditions,” most major religions “1) emphasize the supernatural, 2) are comprehensive in scope, and 3) are collective efforts” (Hale Reference Hale2020, 29). Building from this understanding, I define religion as the “public and collective belief system that structures the relationship of the individual to the divine and supernatural” (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012, 422). These belief systems often include moral and ethical guidelines that shape adherents’ perceptions of what is socially and politically acceptable (Fox Reference Fox2018; Knill et al. Reference Knill, Fernandez-i-Marin, Budde and Heichel2020). For some religions, these moral doctrines police numerous aspects of adherents’ lives with strict expectations of what is permissible in both the private and public spheres (Adamczyk Reference Adamczyk2017). This all-encompassing nature, especially when compounded with the threat of eternal damnation for deviance or disbelief, enables religion to influence individuals’ beliefs and behaviors (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012).

Supporting this argument, the literature suggests that religion plays a vital role in influencing public opinion and policy preferences, particularly for doctrinally relevant policy areas (Budde et al. Reference Budde, Knill, Fernandez-i-Marin and Preidel2018; Castle and Stepp Reference Castle and Stepp2021; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010). Scholars frequently point to abortion to illustrate this, given how issues regarding life and death are central concerns of many religious doctrines (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Stephens et al. 2009). These studies consistently find religion a powerful predictor of public opinion towards policies related to this issue (Adamczyk Reference Adamczyk2013; Adamczyk et al. Reference Adamczyk, Kim and Dillon2020; Jelen and Wilcox Reference Jelen and Wilcox2003). In short, the findings suggest that individuals who identify as religious or hold more religious beliefs tend to be less supportive of progressive abortion policies.

Similar findings persist in research investigating individuals’ feelings towards other morally or doctrinally charged issue areas. For example, several studies show that those who identify as religious or believe religion to be important in their lives are less likely to support liberal same-sex marriage policies (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Claes, Harell, Quintelier and Dejaeghere2010; Olson et al. Reference Olson, Cadge and Harrison2006; Sherkat et al. Reference Sherkat, Powell-Williams, Maddox and de Vries2011). This finding appears more prominent and consistent for followers of the major Abrahamic religions.Footnote 2 In many Judeo-Christian and Islamic sects, marriage is understood to be a holy or divine institution designed for the unification of “man” and “woman” (Yip Reference Yip2005). Therefore, relationships that fall outside of these bounds, such as same-sex marriages, violate this standard and invoke rejection or condemnation.

Gendered expectations of behavior extend beyond marriage in several religions. Though not necessarily inherent to all, conservative denominations within religions such as Christianity, Islam, and Judaism have historically promoted traditional gender roles and norms that subordinate women to men (Burke Reference Burke2012; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Shachar Reference Shachar2005). Further, these religious notions reinforce a static and binary view of gender, leaving little room for the recognition and acceptance of non-cisnormative identities (Sumerau et al. Reference Sumerau, Lain and Cragun2018). Falling in line with these religious principles, public opinion research suggests that religious individuals often hold more pessimistic views towards transgender people (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Hinton and Anderson2019; Nagoshi et al. Reference Nagoshi, Adams, Terrell, Hill, Brzuzy and Nagoshi2008; Norton and Herek Reference Norton and Herek2013) and transgender rights (Jones et al. Reference Jones, Brewer, Young, Lambe and Hoffman2018; Tee and Hegarty Reference Tee and Hegarty2006).

Scholarly studies also suggest that religion is a prominent force in shaping actual policy processes and outcomes, whether indirectly through public opinion or more directly via influence over state institutions (Fink Reference Fink2008; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2011, Reference Htun and Weldon2015). For instance, the Catholic Church has historically wielded substantial power over the development of family law matters and reproductive rights throughout Europe and Latin America (Htun Reference Htun2003; Grzymala-Busse 2016; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002). The Church’s doctrine served as the basis for these types of laws, thus enshrining religious principles into secular policies regarding issues like marriage, divorce, and reproduction (Htun Reference Htun2003, Reference Htun and Hagopian2009; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2011). This translated into an uphill battle for progressive laws about rights like same-sex marriage and abortion (Corrales Reference Corrales2017; Htun Reference Htun2003; Kollman Reference Kollman2007). While many countries in these regions have expanded reproductive and sexuality rights throughout the last two decades, several continue to maintain restrictive (and often religiously inspired) laws.Footnote 3

Religion also plays a role in influencing other legal areas concerning sexual minorities. For example, many of the countries that allow for the death penalty for consensual same-sex sexual activity derive their laws from religion (Asal and Sommer Reference Asal, Sommer and Nadal2017). Most commonly, these harsh policies stem from strict interpretations of Sharia law. According to Human Dignity Trust (2023), 10 of the 12 countries that permit the death penalty in this scenario do so based specifically on codified Islamic law.Footnote 4 Further, while not explicitly based on religion, Uganda’s 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act that punishes “aggravated homosexuality” with the death penalty received strong support from some major domestic and internationally based Christian organizations (Fichtmüller Reference Fichtmüller2022; Kaoma Reference Kaoma2023).

Despite the increased scholarly attention to the role of religion in shaping politics, including sexuality and gender rights, current research suffers from two significant limitations. First, scholars have differing views on what aspects of religion, if any, are essential to consider. Early secularization theorists doubted the (continued) relevance of religion in general, arguing that a modernizing world would erode the social and political impact of religion (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Fox Reference Fox2018; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2004). Despite these expectations, religion still appears to hold a privileged position within many societies and states worldwide. Estimates suggest that nearly 85 percent of the world’s population still identifies with a religious group (Pew Research Center 2015), providing religion a potential foundation for influencing politics from below. Further, while some states explicitly incorporate religion in the government, even “secular” countries often find themselves influenced by or sharing moral authority with religious institutions (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2010; Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Philpott Reference Philpott2007). Overall, “the political implications of religion remain both clear and enormous” (Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012, 433).

While the literature now supports the idea that religion as an institution is important, scholars remain divided on what aspects matter most for understanding variation in policy outcomes. Some scholars point to the significance of religion within society. These studies emphasize the effect of individual religious identification and the saliency of religion in the population (Fink Reference Fink2008; Kollman Reference Kollman2007). For example, in their study on development and reproductive policies, Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018) find that abortion laws are more restrictive in countries where a higher percentage of the population believes religion to be very important in life. Conversely, they fail to establish any significant relationship between these reproductive laws and measures of religious freedom or the separation of religion and the state.

However, other scholars find the connections between religion and the state critically important for understanding policy outcomes. These studies examine factors such as the political institutionalization of religious authority (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015) and party-church alliances (Corrales Reference Corrales2017; Warner Reference Warner2000). This line of research suggests that morality policies will be more restrictive where religion is more deeply embedded within the state and policymaking arenas rather than society. In sum, the diverging findings across the literature demonstrate the need for additional research on which features of religion have the most substantial effect on legal outcomes.

The second limitation in the literature concerns the absence of studies about the relationship between religion and the actual status of transgender rights on a global scale. While scholars have more closely investigated similar issue areas, such as reproductive and sexual orientation rights, the findings from those studies may not accurately represent how religion influences transgender rights. As the case of Iran in the introduction section illustrates (Jafari Reference Jafari2014; Javaheri Reference Javaheri2010), religious principles can be detrimental to the legal rights of sexual orientation minorities while simultaneously allowing progress on issues within the realm of transgender rights.

Global empirical research on the laws and policies concerning transgender rights remains scarce (Williamson Reference Williamson2023). Dicklitch-Nelson and Rahman (Reference Dicklitch-Nelson and Rahman2022) briefly discuss a potential correlation between a country’s respect for trans rights and factors like religion, regime type, and economic conditions in the final section of their work. More specifically, they report a negative association between a religious population and their collective index of transgender rights. However, they emphasize that an analysis to examine this relationship adequately falls beyond the scope of their article. Therefore, their preliminary comparison can only offer a glimpse into the complex relationship between religion and transgender rights.

In sum, the limitations of previous research indicate the need for more fine-grained analyses of religion’s role in shaping laws and policies. I extend the study of religion to transgender rights specifically, a policy area that previously received little empirical attention in cross-national political science research. The following section discusses the potential theoretical connections between these two concepts. Building from previous research, I distinguish between the different aspects of religion and how each may work to shape transgender rights.

Theory

As the discussion of the scholarly literature suggests, many religious traditions have historically emphasized rigid, binary gender norms and identities that are inherently connected to birth-assigned sex. These norms then serve as the foundation underlying the (gendered) family unit central to religious social structures. Thus, the recognition of transgender individuals (and, therefore, their rights) challenges not only the theological construction of what gender is or can be but also the very basis of society. Given this relationship between religion and gender, more broadly, in conjunction with the evidence from previous scholarship concerning similar issue areas, I expect to find a negative relationship between measures of religion and transgender rights.

However, it remains unclear how and when religious influences within a country might impact actual policies regarding these kinds of rights. Therefore, I investigate the relationship between religion and transgender rights by examining multiple features of religion and how it manifests within a state and society. Broadly following Htun and Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2015) and Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018), I focus on the formal and informal aspects of the religion-state relationship, the religious characteristics of society, and the doctrinal differences between religions.

The Religion-State Relationship

The development of the modern state required specific decisions regarding the “political institutionalization of religious authority” (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015, 456; Fox Reference Fox2008). The possible arrangements resulting from these decisions fall along a spectrum depending on the degree to which religion is fused with state power (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002, Reference Minkenberg2003). On one end, political and religious authority is unified or heavily overlaps. In such cases, religion is an “all-encompassing” force within the state that exerts considerable influence or control over political leadership and various aspects of the law (Fox Reference Fox2018, 65). States such as Iran and Saudi Arabia are two examples closer to this end of the spectrum. At the other end are states with a strict separation between the religious and political realms (Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002, Reference Minkenberg2003). Examples closer to this pole might include countries like China and North Korea or democracies like France and the United States (Fox Reference Fox2018; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002).Footnote 5

Characterizing the political institutionalization of religion requires an assessment of both the formal and informal components of the religion-state relationship. The formal aspect refers to the extent to which countries enshrine religion or religious principles into official laws and government policies. In other words, this includes laws that “monitor the relationship between religion and the state,” such as whether there is an officially recognized religion or a religious court with state-granted authority to enforce laws (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018, 51). Countries with a high level of formal political institutionalization of religion have more official laws and policies privileging one or more religions.

The official incorporation of religion into the state is essential to consider for two main reasons. First, connecting religion to the state through the law makes challenging religious principles more difficult. The state and religion become fused, and “challenges to the religious interpretations supported by state law come to be seen as challenges to the entire institutional configuration” (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015, 457). More simply, support for any laws contradicting the religion may be framed or interpreted as threatening the state or nation (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2014). Even without a perceived threat, historically present laws and policies “will often remain in effect out of sheer inertia or the strength and legitimacy of the tradition” (Fox Reference Fox2018, 137).

Second, codifying religious principles into official law freezes the current interpretation of that religion (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015). Therefore, even if certain denominations or reformist groups adopt more progressive stances over time, the law will continue to reflect the previous dominant notion. While laws can and do change, challenging the law becomes more difficult as religion and state become more intertwined. Because many major religions historically tend to hold cisnormative and patriarchal views of gender, as discussed earlier, I hypothesize that:

H1: Transgender rights will be lower in countries where the formal political institutionalization of religion is higher.

Even when official laws establish a high level of separation between religion and the state, religion may still wield considerable influence over government institutions and policymaking processes through informal channels. I consider two informal mechanisms through which religion might impact transgender rights. The first aspect concerns the source of support for the political regime.Footnote 6 If support from a specific group is crucial to the regime maintaining its power, then actors within the regime may be more sensitive to the policy preferences of that group (Wig et al. Reference Wig, Dahlum, Knutsen and Rasmussen2020). Regimes more reliant upon religious groups will, therefore, feel pressed to adopt laws and policies “that govern people according to the principles laid out in the religious teachings” (Schleutker Reference Schleutker2021, 218). Thus, transgender rights will likely be lower in these countries, given the cisnormative understandings of gender within many religions.

Religion can also influence politics when the stakes are lower than regime survival. For instance, policymakers may choose to consult religious groups about specific legislation. This may be a strategic tactic on behalf of the politician to bolster support from a particular sector or interest group, or this may reflect their personal religious beliefs (Ninsiima et al. Reference Ninsiima, Coene, Michielsen, Najjuka, Kemigisha, Ruzaaza, Nyakato and Leye2020). In either case, consulting religious actors or organizations about political matters provides another informal opportunity for religion to influence the state and its legal environment. This, in turn, extends the possibility that the law will reflect the preferences of that religion. Therefore, I expect a greater degree of religious influence through informal mechanisms will correspond with fewer transgender rights.

H2: Transgender rights will be lower in countries where the informal political institutionalization of religion is higher.

Religion in Society

Looking beyond the religion-state relationship, the presence of religion within society may also influence politics. Scholars have examined the existence of religion in society in various ways, each of which may impact a state’s laws and policies. Several studies focus on the degree of religiosity within the population (e.g., Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2003). Religiosity is “the extent to which people are religious” (Fox Reference Fox2018, 15). Scholars remain divided on how exactly to operationalize this concept but measures typically focus on factors such as ideological commitment (e.g., the importance of religion) or religious practice (e.g., attending places of worship) (Clayton and Gladden Reference Clayton and Gladden1974; Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018).

For example, Kollman (Reference Kollman2007) uses measures of monthly church attendance to examine how religiosity affects the adoption of same-sex union laws. In this study, Kollman (Reference Kollman2007, 347) finds that the religiosity of a country’s population was better than “how church-state relations are institutionalized” at explaining variation in these types of laws. More specifically, the analysis reveals that countries with the lowest levels of religiosity had laws recognizing these types of unions. Conversely, five of the seven countries with the highest levels of religiosity offered no legal recognition of same-sex relationships.

Other studies focus on individuals’ identification with religion or a specific denomination rather than the degree of commitment or practice. Asal et al. (Reference Asal, Brown and Figueroa2008) incorporate these types of measures in their analysis of abortion policies. They find that “as the percentage of Catholics in a country goes from its lowest point (none) to its highest point (99.8%), the probability of legalized abortion on demand drops from 39.3% to 8.6%” (Asal et al. Reference Asal, Brown and Figueroa2008, 278). Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018) came to similar conclusions about abortion laws in their study utilizing estimates of the population who identified as Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu. Of these denominations, only the percentages of the population identifying as Catholic, Muslim, and Buddhist were statistically significant. This finding suggests that not only does the presence of a religious population in general matter, but the specific denomination that is prevalent is also important (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012).

Finally, scholars also often emphasize the effects of religious diversity on political outcomes. In short, increased diversity creates more competition for followers between different religious groups. This competition, in turn, may incentivize religious elites to change strategies or stances toward certain political arrangements or issues to attract more members (Gill Reference Gill1998; Trejo Reference Trejo2009). For example, Gill (Reference Gill1998, 7) points to religious diversity to help explain why the Catholic Church in some Latin American countries defected from “their traditional alliance with the elite” to “defend the interests of the poor.” The growing Protestant competition in the region pushed Catholic leaders to alter their political strategies to maintain and grow their membership.

Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018) hypothesize that competition introduced by religious diversity may affect policy outcomes by limiting the influence a specific religion has in the political arena. Further, they argue that this competition may incentivize religious groups in the political sphere to “leave religion off the agenda altogether” out of fear “that a different group may one day promote its own religious program” (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018, 52). They fail to find support for their hypothesis, but they emphasize that different aspects of religion may not influence all policy areas in the same way. Given the importance of religious diversity in explaining other political outcomes (e.g., Gill Reference Gill1998; Trejo Reference Trejo2009), it is essential to consider it as a potential avenue through which religion may influence society and, ultimately, a country’s laws regarding transgender rights.

Building on this research, I present three hypotheses about the relationship between religion in society and transgender rights. The first hypothesis considers the effect of religious identification and the saliency of religion. Though differences persist depending on the measure used, the previous research primarily supports a negative relationship between religion in society and progressive laws concerning some morally or doctrinally relevant issues. Therefore, I expect to see similar results for transgender rights. I argue that a high degree of religion within society, meaning a higher percentage of people identifying as religious or believing religion to be important, reflects and reinforces traditional and conservative beliefs towards gender. This makes it more difficult to garner support for expanding transgender rights.

H3: Transgender rights will be lower in countries where religion is more prevalent within society

While hypothesis 3 focuses on religious influence over society in general, previous research also emphasizes the importance of considering which religious denomination is most prevalent (e.g., Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018; Grzymala-Busse Reference Grzymala-Busse2012; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2002). Based on sacred texts, the major Abrahamic religions appear to support binary and static views of gender. In Christianity and Judaism, these cisnormative principles are expressed in traditional interpretations of books such as Genesis and Deuteronomy. More specifically, Genesis 1:27 asserts that God created male and female, and Deuteronomy 22:5 prohibits individuals from wearing clothing of the opposite sex (Hartke et al. Reference Hartke, Markham and Vazquez2023; Plante Reference Plante2022; Stryker Reference Stryker2008). Some sects within these religions, namely Judaism, have moved towards more liberal stances on transgender issues, but traditional values still loom large (Human Rights Campaign 2023).

Islamic leaders have historically interpreted the Quran in a similarly conservative fashion, but there have been extensive debates centered around the permissibility of gender affirming procedures (Etengoff and Rodriguez Reference Etengoff and Rodriguez2022). Conservative Sunni and Shia scholars interpret the Quran (4:119) in a more restrictive manner, arguing that altering the “creation of Allah” is forbidden (Alipour Reference Alipour2017). Others argue that the Quranic verse (4:119) does not refer to “operations on the human body” and, therefore, these types of procedures are permissible under Islam (Alipour Reference Alipour2017, 168). Ayatollah Khomeini belonged to this latter camp and issued a fatwa allowing certain transgender-related surgical procedures in Iran (Javaheri Reference Javaheri2010). Despite the supportive interpretations by some religious scholars and jurists, more conservative Islamic ideas about gender currently prevail (Zaharin and Pallotta-Chiarolli Reference Zaharin and Pallotta-Chiarolli2020).

Buddhism and Hinduism appear to take more ambiguous stances on transgender issues compared to the Abrahamic religions, making it more challenging to hypothesize on the potential impact of these specific religions (Human Rights Campaign 2023). Diverse gender identities are referenced in several Hindu texts and narratives (Elischberger et al. Reference Elischberger, Glazier, Hill and Verduzco-Baker2018; Nagar and DasGupta Reference Nagar and DasGupta2023), and “Vedic culture allowed transgender people of the third sex, known as hijras, to live openly according to their gender identity” (Human Rights Campaign 2023). Despite this, there is no unified or dominant stance toward transgender identities in contemporary Hinduism, and some groups have adopted considerably more conservative views (Elischberger et al. Reference Elischberger, Glazier, Hill and Verduzco-Baker2018). Similar variation appears to be present across Buddhism, with the personalistic nature of the religion resulting in little consensus towards issues related to transgender individuals (Human Rights Campaign 2023).

In sum, the presence of certain religions in society may have a greater effect on transgender rights than others. Given the scarcity of research on religion and transgender rights, it is difficult to hypothesize which faiths would have the most significant impact. Building solely on the insights provided in this section, the Abrahamic religions appear to be the least likely to promote transgender rights, given the explicit religious principles privileging the (cis)gender binary. Therefore, I expect that countries with a greater percentage of the population belonging to one of these religions will have fewer transgender rights protections in place.

H4: Countries with a greater percentage of the population belonging to one of the Abrahamic religions will have fewer transgender rights

The final hypothesis in this section focuses on religious diversity. Following Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018), I expect increased religious diversity to correspond with greater transgender rights. The competition between religious groups weakens the power that one specific group has over influencing society and the policymaking process from below. However, religious diversity may not be beneficial if all the groups still maintain the same position on an issue. Despite this possibility, I expect to see a positive relationship between religious diversity and transgender rights.

H5: Countries with higher levels of religious diversity will have more transgender rights than countries with religiously homogenous populations.

Data and Methods

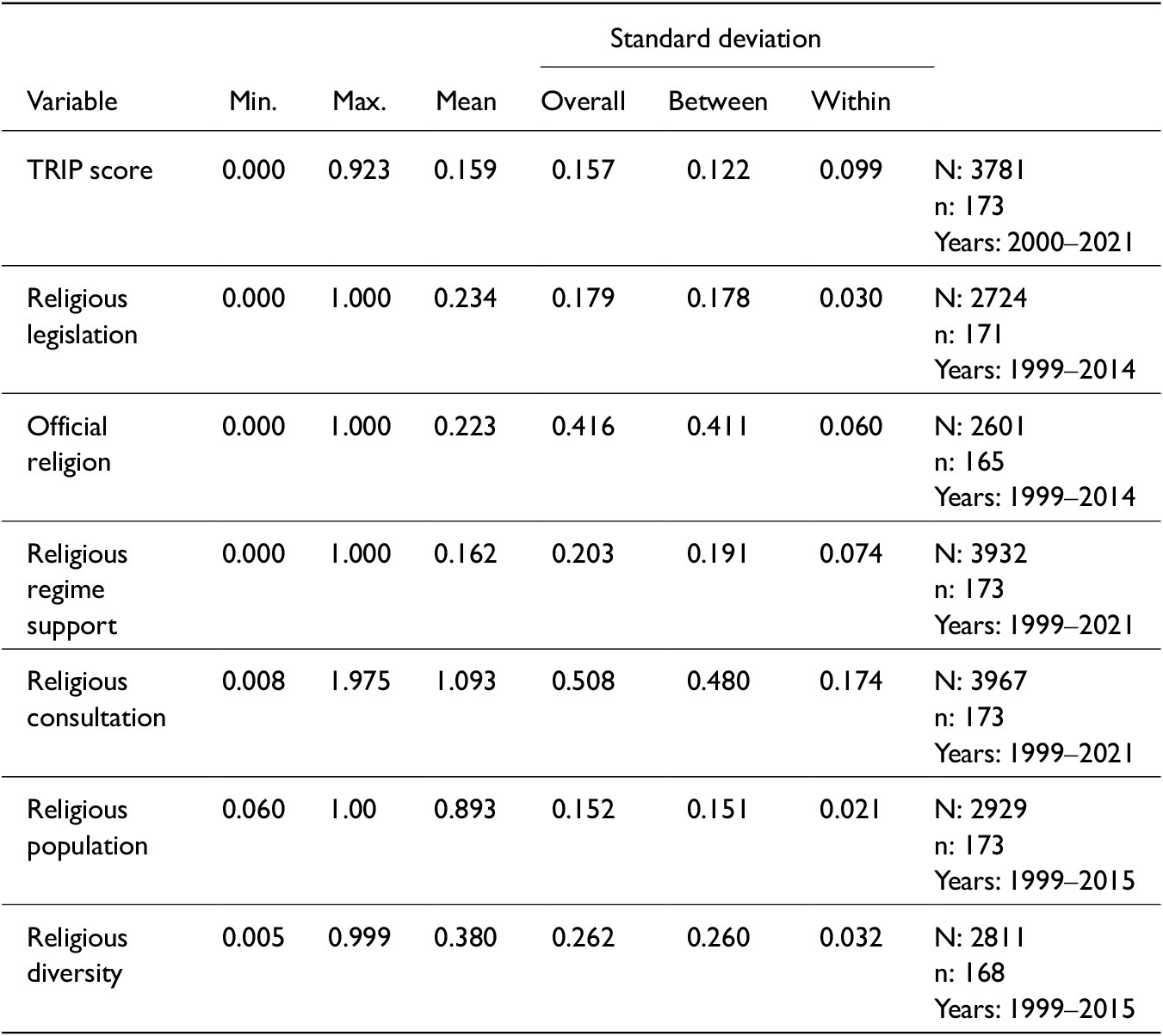

To test these hypotheses, I run OLS models with panel-corrected standard errors (PCSE) and lag all independent variables by one year (Beck and Katz Reference Beck and Katz1995, Reference Beck and Katz1996; Beck Reference Beck2001). Though fixed-effects or random-effects models are typical for time-series cross-sectional analyses (e.g., Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015; Velasco Reference Velasco2018), the nature of this data makes an OLS regression with PCSE superior to these alternatives. Several key variables in this analysis are slow-moving or rarely changing. As the standard deviations in Table 1 demonstrate, this results in minimal within-country variance, particularly for some of the measures of trans rights and religion.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of select key variables

Note: N = observations; n = countries.

Because fixed and random effects account for the within-country variance, these models have “low statistical power” in cases where that variance is low (Hill et al. Reference Hill, Andrew Davis and French2020, 361). Therefore, these models will produce biased and unreliable estimates (Beck Reference Beck2001; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Andrew Davis and French2020; Plümper and Troeger Reference Plümper and Troeger2007). Conversely, OLS regressions with PCSE can handle the slow-moving variables while also addressing potential issues of heteroskedasticity (Beck and Katz Reference Beck and Katz1996; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Andrew Davis and French2020).

To further rule out fixed and random effects, I also checked for the presence of multicollinearity. Before doing so, I ran a Hausman test to determine if fixed or random effects were more appropriate. The test provided support for the fixed effects model. However, a variance inflation factor (VIF) test reveals that the fixed effects models suffer from multicollinearity and may generate biased estimates. This issue disappears with the OLS models without fixed effects, thus lending additional support for the PCSE approach in this analysis.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable in this analysis is a composite measure of transgender legal rights. This measure comes from the Trans Rights Indicator Project (TRIP) dataset. It consists of a yearly score that reflects the trans-specific legal rights countries provide related to criminalization, legal gender recognition, and anti-discrimination protections (Williamson Reference Williamson2023). This variable was chosen as it is among the only publicly available and comprehensive measure of transgender rights globally over time. Table A1 in the appendix provides a breakdown of the specific indicators of trans rights that are captured in the TRIP score.

The indicators for criminalization account for national and subnational laws, while the indicators related to recognition and discrimination only consider national-level laws. Each indicator is dichotomous, where a country receives a 1 if the right is protected and a 0 otherwise. To construct the overall score, the individual indicators are summed together to form an index that ranges from 0 to 13. Higher values thus represent greater rights protections by the country. For this analysis, I rescale the score so that values range between 0 and 1 for more meaningful interpretation and comparisons with the independent variables.

Independent Variables

Given the scope of the hypotheses, I utilized a variety of measures to capture the different aspects of the religion-state and religion-society relationships. For hypothesis 1, I examine the formal element of the religion-state relationship through two variables. The first includes a measure capturing the extent of religious legislation upheld by the state. As Htun and Weldon (Reference Htun and Weldon2015, 464) explain, “the existence of religious laws in many areas evinces a significant fusion of ecclesiastical and political authority.” Data for this variable comes from the Religion and State (RAS) dataset (Fox 2017). The RAS provides data on 52 areas of law and government policy that support or entrench religion in the state. However, some of these indicators include religious laws concerning sexuality (e.g., same-sex marriage) and gender (e.g., public dress and modesty). Given the focus of this analysis, I exclude any indicators explicitly related to gender or sexuality to avoid any potential endogeneity problems (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015). The resulting variable consists of a cumulative index capturing a count of religious legislation across 40 areas.Footnote 7 I rescale the variable to range between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating a higher degree of religious legislation present.

The second variable includes a measure capturing the presence of an official state religion (Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2015). This data also comes from the RAS, which considers an official state religion to be present only if there is a “constitutional clause, a law, or the equivalent explicitly stating that a specific religion or specific religions are the official religions of that state” (Fox 2017, 2). For this variable, a value of 0 indicates no official religion, while a 1 indicates the presence of an established state religion.

For hypothesis 2, I use two variables from Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) to measure the informal religion-state relationship (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023). These measures aim to capture the less official, but no less important, ways in which religion may be entrenched within the government. The first variable measures how reliant the current political regime is on religious groups to maintain power. This variable draws from the responses by V-Dem country experts who answered the question, “Which groups does the current political regime rely on in order to maintain power?” with the clarification that the group retracting “support would substantially increase the chance that the regime would lose power” (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023, 140; Wig et al. Reference Wig, Dahlum, Knutsen and Rasmussen2020). Each country expert coded the religious group variable as 1 if religious support groups were present or 0 otherwise. The resulting variable provided by V-Dem and used in this analysis contains the mean response of all expert coders for each country-year (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023, 140; Wig et al. Reference Wig, Dahlum, Knutsen and Rasmussen2020, 13).

The second measure captures the extent to which policymakers consult religious organizations, providing insights into another informal way religion may influence the state and policymaking process. This variable is based on V-Dem country expert responses to the question, “Are major religious organizations routinely consulted by policymakers on policies relevant to their members?” (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023, 200). Experts respond to the question by indicating the degree of consultation, essentially ranging from complete government insulation from religious organizations to routine consultations with these groups. For this analysis, values for informal religion-state variables range between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 representing greater religious influence.

While the first informal variable captures the state’s reliance on religious organizations for survival, this second variable measures the active influence of religion over policymaking, even in the absence of the regime’s dependency on religion for power. In other words, the “religious regime support” variable captures a higher (but still informal) level of engagement between religion and the state. Meanwhile, the “religious consultation” variable captures lower-level processes where religious groups have less leverage over the state but may still influence areas where state policy and doctrinally relevant issues intersect.

For hypotheses 3 through 5, I measure religion in society in four ways. First, I include a measure of the degree of religiosity in society. Following Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018), I measure religiosity using data from the World Values Survey (WVS) question concerning the importance of religion. For this question, survey respondents indicated the level of importance on a four-point scale that ranged from “not at all important” to “very important” (EVS 2020; Haerpfer et al. Reference Haerpfer, Inglehart, Moreno, Welzel, Kizilova, Diez-Medrano, Lagos, Norris and Ponarin2021). The resulting variable consists of the average response for each country-year (Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Sundström, Holmberg, Rothstein, Pachon, Dalli and Meijers2023). Data for this variable are only available for a small subset of the larger sample due to the limited observations included in the WVS survey.

The next two variables capture religious identification. I use the Religious Characteristics of States (RCS) dataset to measure the overall percentage of a country’s religious population (Brown and James Reference Brown and James2017). I also include separate variables disaggregated by religion to account for denominational differences. These include Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism. The final variable for religion in society is religious diversity. Following Alesina et al. (2003) and Trejo (Reference Trejo2009), I calculate religious diversity by first summing the squares of each religious group share (i.e., a Herfindahl index). I then subtract this value from one for each observation so that the resulting variable reflects the “probability that two randomly selected individuals from a population belonged to different [religious] groups” (Alesina et al. 2003, 158-59).

Control Variables

I include measures of democracy, economic development, globalization, and geographic region as control variables in each model. While democracy does not guarantee that a government will adopt greater transgender rights, key dimensions of democracy may make these regimes more likely to advance these rights. Features such as elections, the freedom of expression, and the freedom of association may increase the likelihood that a country will protect transgender rights as these aspects enable trans individuals to exist more openly, advocate for their rights, and influence political processes and legislation (Corrales Reference Corrales2017; Encarnacion Reference Encarnacion2014). Alternatively, the closed nature of autocratic regimes restricts such opportunities.

To measure democracy, I use the electoral democracy index (EDI) from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023). This index captures the fundamental electoral element that is key to democracy, while also including the rights that make those elections meaningful in practice. Importantly, the EDI does not include any measure of “LGBT” or transgender rights, allowing for independent operationalization of the key variables (Poe and Tate Reference Poe and Tate1994). Broader measures of democracy introduce the risk of representing the dependent variable on both sides of the equation. For example, the political and civil rights measure provided by Freedom House specifically mentions the “LGBT” community in at least one indicator involved in the overall score (Freedom House 2022).

In terms of economic conditions, previous research tends to support a positive relationship between a country’s level of economic development and subsequent support for minority rights (Badgett et al. Reference Badgett, Waaldijk and van der Meulen Rodgers2019; Corrales Reference Corrales2017; Dicklitch-Nelson et al. Reference Dicklitch-Nelson, Buckland, Yost and Draguljic2019; Sommer and Asal Reference Sommer and Asal2013). Essentially, greater economic development and material security allow countries to shift from survival mode to focusing on tolerance and advancing the rights of groups within society (Inglehart and Baker Reference Inglehart and Baker2000). Given the potential for economic development to affect countries’ protections of transgender rights, I include a measure of GDP per capita using data from the World Bank (2022) as a control in each model. Following previous scholars (e.g., Asal et al. Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2012; Frank et al. Reference Frank, Camp and Boutcher2010; Velasco Reference Velasco2018, Reference Velasco2020), this measure is logged due to its skewed distribution.

I also control for globalization to account for the impact that international norms and values may have on domestic policies towards transgender rights. As Asal et al. (Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2012, 330) explain, “the world culture and normative diffusion literature argues that the strengthening of links between countries allows for the diffusion of new human rights and norms of tolerance.” Supporting this argument, Velasco (Reference Velasco2018) found that social globalization had a highly significant effect on policies related to sexual orientation minorities. Nevertheless, globalization can also potentially lead to pushback against norms perceived as foreign or incompatible with the dominant culture of a country (Long Reference Long2005).

In either case, the significance of globalization variables in other rights-focused studies might suggest that this variable also affects laws regarding transgender rights and should be included as a control. I use the KOF Index of Globalization to capture the economic, social, and political aspects of this phenomenon (Dreher Reference Dreher2006). I use the de facto version of the index to avoid any overlap between this variable and the dependent variable. The de jure version includes measures of gender parity and civil liberties that may create endogeneity issues.

Finally, I include regional dummy variables, with Western countries as the comparison base group. This helps account for any differences between countries that may stem from the influence of regional conditions or norms (Asal et al. Reference Asal, Sommer and Harwood2012; Dicklitch-Nelson et al. Reference Dicklitch-Nelson, Buckland, Yost and Draguljic2019; Frank et al. Reference Frank, Camp and Boutcher2010). Regional classifications are based on the politico-geographic regions provided by V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Agnes Cornell, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Glynn, Grahn, Hicken, Kinzelbach, Marquardt, McMann, Mechkova, Paxton, Pemstein, von Römer, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Tzelgov, Uberti, Wang, Wig and Ziblatt2023). Western countries are those that V-Dem codes as Western Europe and North America, which includes Australia and New Zealand.

Findings

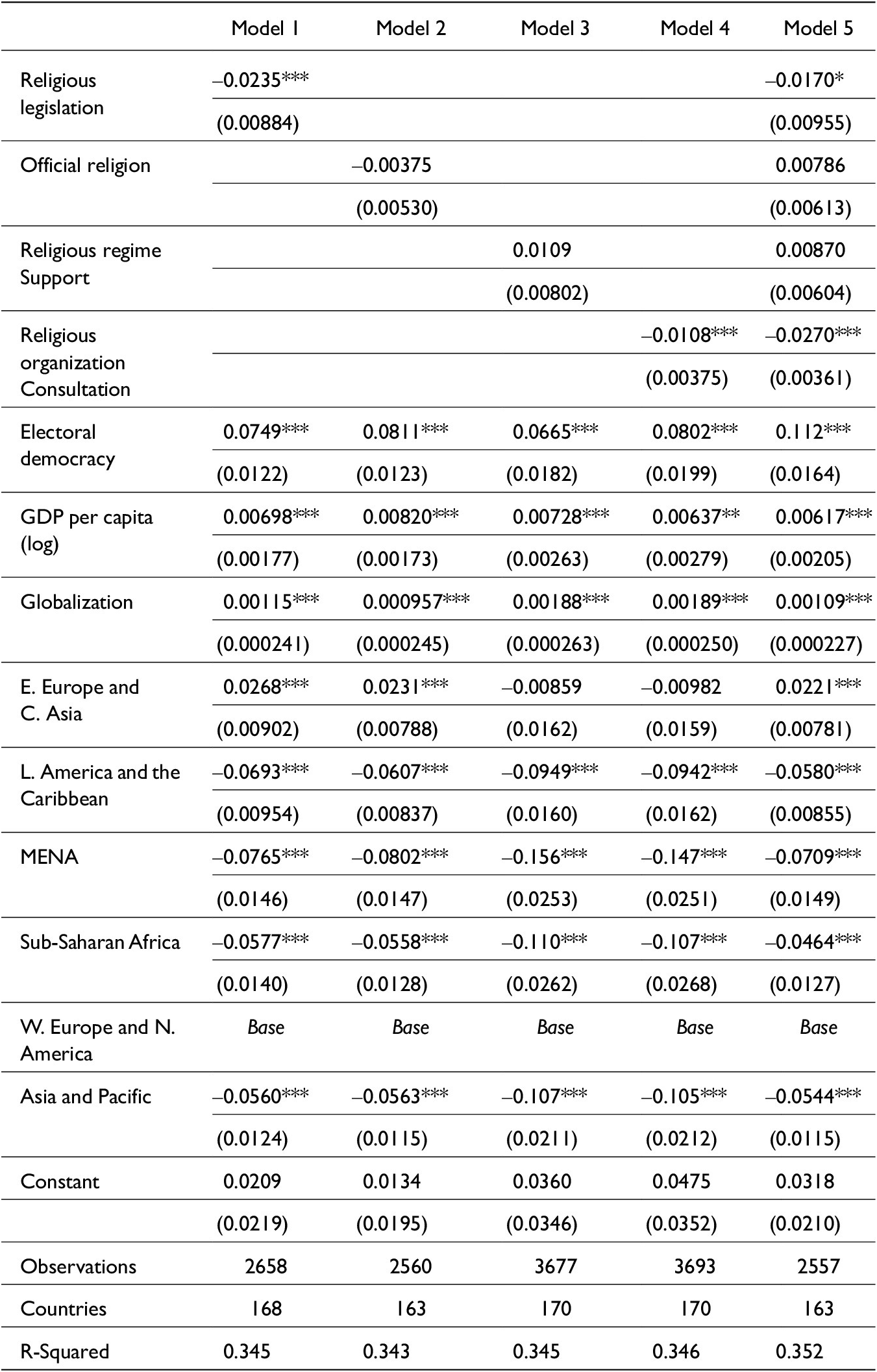

Table 2 presents model results testing the hypotheses concerning the religion-state relationship. The first two models include the measures of the formal institutionalization of religion in the state. Results from Model 1 show that religious legislation shares a negative and statistically significant relationship with transgender rights. This suggests that countries with more laws supporting or privileging religion tend to have fewer rights in place for transgender people. As Model 2 shows, the second formal measure is insignificant, meaning that the presence of an official religion does not appear to impact a country’s trans rights. These findings provide mixed support for hypothesis 1.

Table 2. Religion-state regression results

Note: Panel corrected standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Models 3 and 4 include the measures capturing the informal institutionalization of religion. As with the formal counterparts, the results provide mixed support for the hypothesis. Religious regime support is not statistically significant (Model 3), but religious organization consultation is in the expected direction (Model 4). Transgender rights suffer when policymakers routinely consult religious organizations about policy matters. Model 5 includes the formal and informal measures together. The results reflect the same basic findings from the other models.

Because missing values resulted in varying sample sizes across the models in Table 2, I ran additional analyses using unified samples for each religion-state variable. Table A3 in the appendix presents these results, which largely support the findings in the main models. Coefficients for religious legislation and religious organization consultation remain significant and in the expected direction, while official religion remains insignificant. The only substantial difference between the primary and robustness models is the significance of religious regime support. This variable is not significant in the primary model presented in the text but is in the robustness model. However, the unified sample contains roughly 1,100 fewer observations than the analysis presented in the main text. Therefore, the mixed results concerning religious regime support should be interpreted with caution.

Democracy, economic development, and globalization are statistically significant across all models in the main text and appendix. Further, these relationships are in the hypothesized directions. Increases in any of these variables correlate with an increase in transgender rights. Despite the positive and significant findings, the magnitude of the effects of GDP per capita and globalization are not very substantial. Apart from Central Europe and East Asia, all regional dummies are significant and negative across all models. This suggests these regions are less likely to protect transgender rights than Western Europe and North America on average.

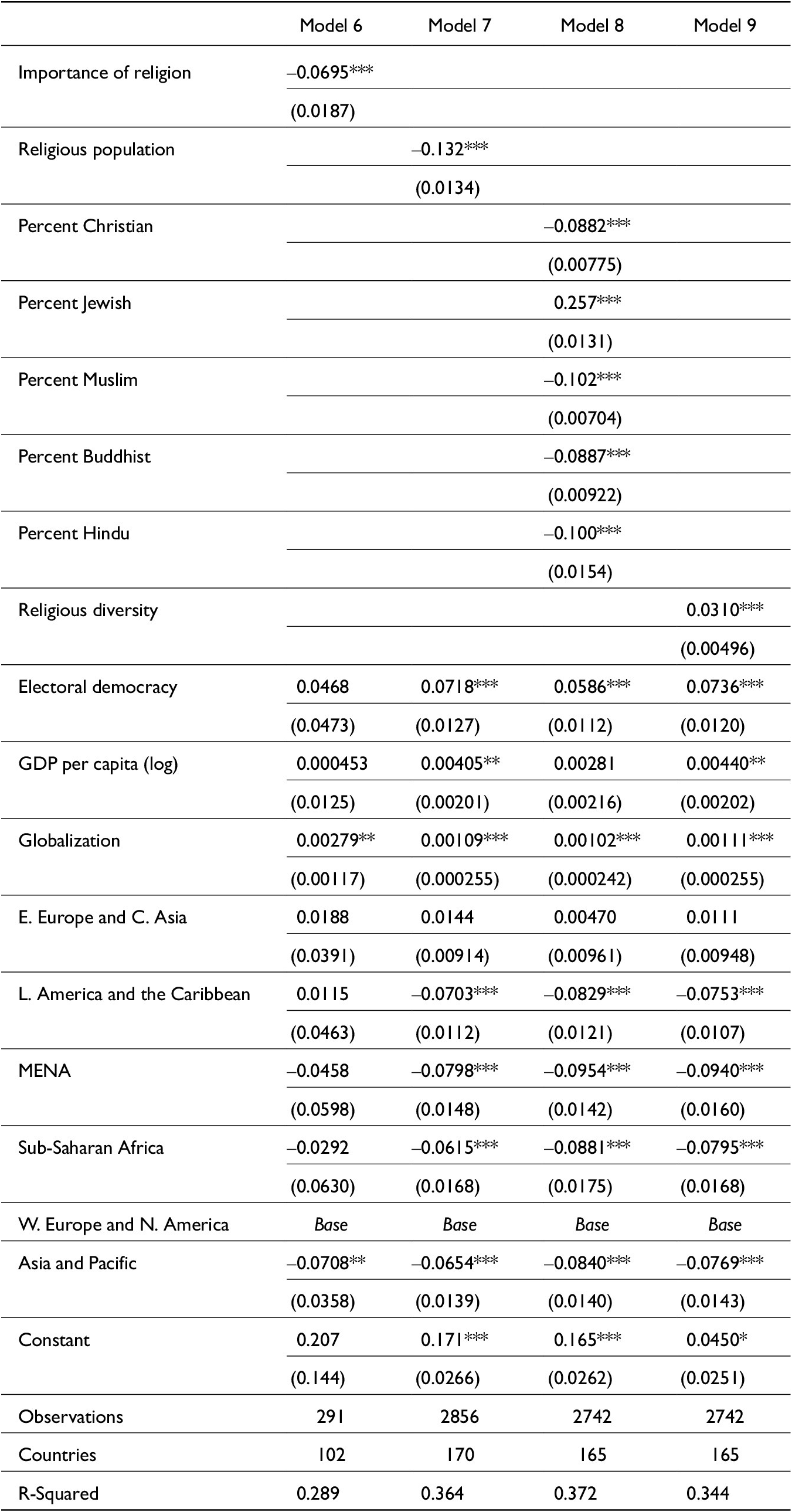

Table 3 presents results from the analyses that involved measures of religion in society. Model 6 includes the measure of religiosity based on the World Values Survey (WVS) question about the importance of religion in a respondent’s life. The results are statistically significant and negative, suggesting that countries with higher levels of religiosity have fewer transgender rights. However, the number of observations for this model is substantially lower than the other models due to the limited coverage by the WVS. Their surveys only include a select number of countries for certain years, which limits the number of observations. Despite this shortcoming, the finding suggests that this measure of religiosity is an important factor that could affect transgender rights protections.

Table 3. Religion-society regression results

Note: Panel corrected standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Model 7 displays the results for the analysis that includes the percentage of the religious population. The findings support the expectations of hypothesis 3. Religious populations are associated with fewer transgender rights. Model 8 presents some interesting results concerning the effect of the different religions. As hypothesis 4 posited, a higher population of Christians and Muslims corresponds with a decrease in transgender rights, but this finding did not persist for the measure of Jewish populations. Instead, the analysis suggests a positive relationship between the percentage of the population that is Jewish and transgender rights protections. Though Hinduism has some historical cultural recognition of gender diversity, the coefficient was negative and nearly matched the coefficient for Muslim populations. Finally, Buddhism was also significant and negative, closely resembling the coefficient for Christian populations. Importantly, the findings related to Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism should be interpreted cautiously, given the low percentages of these populations across most countries.Footnote 8

Model 9 includes the measure of religious diversity. The findings lend support to the final hypothesis. As religious diversity increases, transgender rights should also increase. Though this supports the expectations of hypothesis 5, this finding is interesting given the null effect found in the Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer (Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018) study on abortion. The diverging findings between these two studies help demonstrate how various aspects of religion may affect certain policy areas differently.

As with the religion-state measures, I again provide analyses with unified samples in the appendix as a robustness check for each religion-society measure (Table A5). I exclude the religiosity measure from the World Values Survey (WVS) because it has so few observations (N=291). For the other variables, only the sample size for the model with the overall religious population differed and only by 114 observations. The results in the robustness models (Table A5) echo the findings presented in the main text (Table 3), further supporting the religion-society hypotheses.

Findings concerning the control variables in Models 6 through 9 were less consistent than those for the models examining the religion-state relationship. Democracy is insignificant in Model 6, and economic development loses significance in Models 6 and 8. Additionally, the coefficients for economic development in all the models are small, suggesting that GDP per capita only has a marginal effect on transgender rights. Globalization retained its significance across each model, but like GDP per capita, the magnitude of its impact is slight. Results for regional dummies vary across the models, but each significant relationship suggests that all other regions are less likely than Western countries to advance transgender rights.Footnote 9

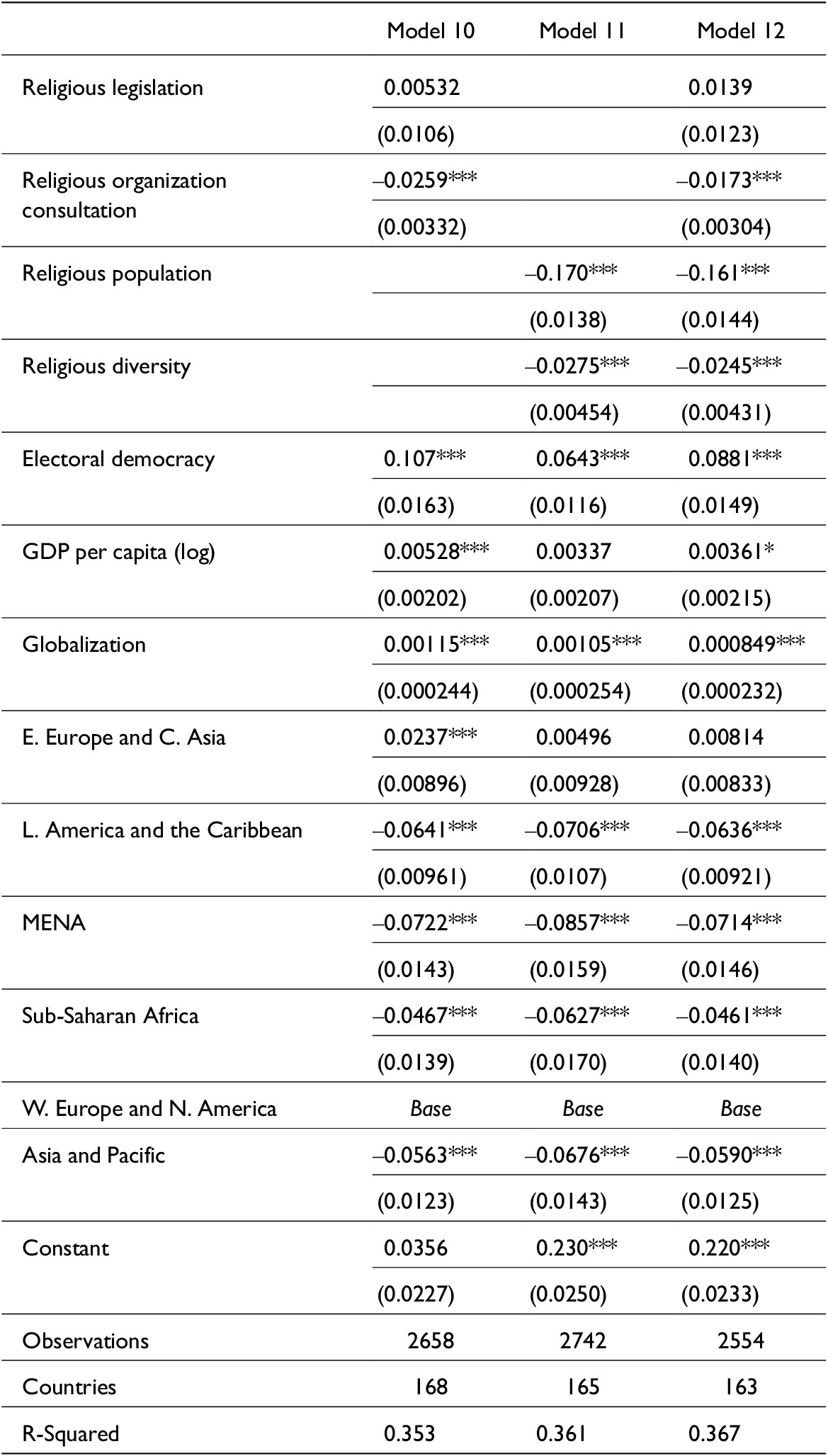

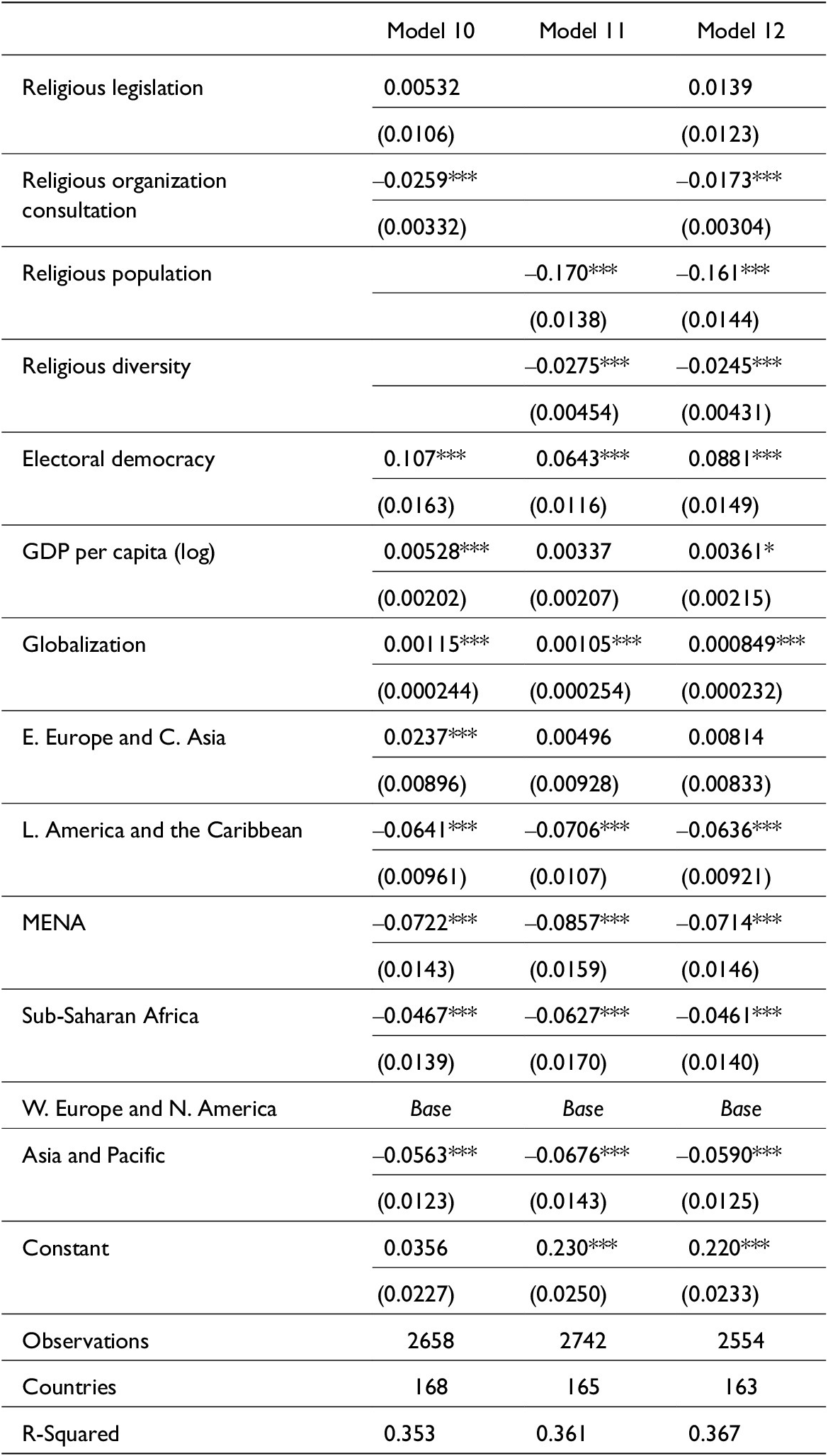

Finally, Table 4 presents additional models focused on the significant state (Model 10) and society measures (Model 11), as well as a final model testing both types of measures together (Model 12).Footnote 10 Interestingly, religious legislation is no longer significant in either of the models but results regarding religious organization consultation remain largely unchanged. Thus, the results suggest that transgender rights tend to suffer more in countries where policymakers routinely consult religious organizations, even when accounting for religion in society.

Table 4. Significant state and society results

Note: Panel corrected standard errors in parentheses. * p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Turning to the societal measures, the percentage of the religious population continues to be significant and negative in Models 11 and 12. Religious diversity also remains significant in these models; however, the direction of the relationship seems to change. While earlier models (Table 3) suggested a positive relationship, the coefficients for this variable in Table 4 are now negative. In other words, an increase in religious diversity appears to correspond with fewer transgender rights protections. This shift in the findings highlights these relationships’ complexities and warrants further investigation moving forward.

Results for the control variables remain relatively consistent with findings from earlier models. Levels of democracy, GDP per capita, and globalization are all significant and positive in the final model. However, the small coefficients of the latter two variables suggest that they have a marginal impact on transgender rights. Results regarding the regional controls echo earlier findings as well. Eastern Europe and Central Asia is the only region with a positive coefficient, but it is insignificant in the final model.

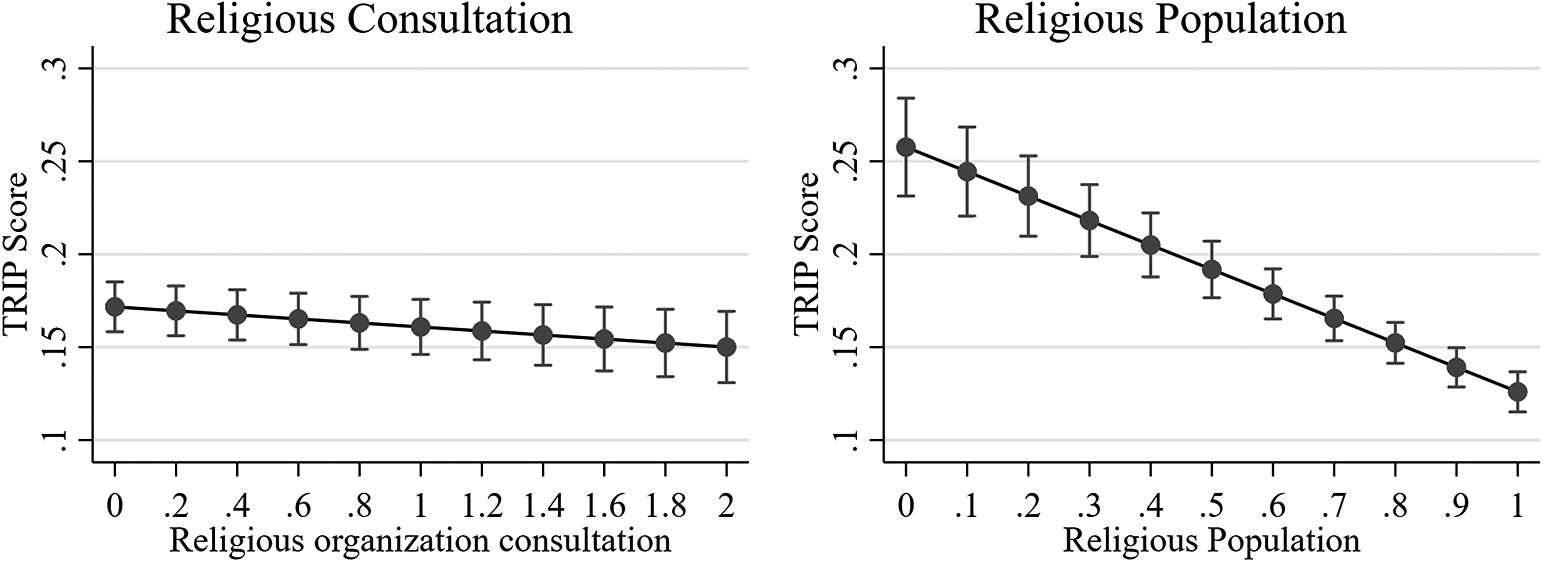

Figure 1 provides the predicted margins for religious consultation and population to summarize the major findings. These two variables were the ones that were consistently significant and in the same direction throughout every model in the analysis. Thus, the findings regarding these variables appear to be the most robust. As Figure 1 illustrates, increased religious consultation by policymakers and a more religious population corresponds with lower transgender rights protections. The magnitude of the relationship is relatively modest for religious consultation but more substantial for religious population. Ultimately, the results suggest that the effect of religion on transgender rights depends upon where and to what extent religion manifests within a country.

Figure 1. Predicted margins with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study sought to unpack the complex relationship between religion and transgender legal rights. Recognizing the different ways that religion can manifest and potentially affect politics, I incorporated a variety of measures that allowed me to examine religious influences in both the state and society (Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer Reference Forman-Rabinovici and Sommer2018). Overall, the results suggest that religion plays an important role in explaining variation in transgender rights. Where religious influences were more prevalent, transgender rights tended to be lower.

However, the effects of religion were not entirely uniform throughout the models. More specifically, while the formal and informal connections between religion and the state had some relevance, the level of religiosity within a country’s society appeared to have a more substantial and consistent impact on transgender rights protections. In other words, the findings support the idea that religion’s effect on political outcomes depends on how and where those religious influences manifest within a country. This contribution can help explain scenarios where countries’ laws or policies continue to be less progressive despite a decline in or absence of religious influences within the state itself. Thus, even if (or when) states reduce their ties to religious institutions, the prevalence of a religious society can keep religious influences over laws alive and well.

These primary findings have important implications for trans rights activists and scholars of gender politics in general. For activists, this article helps shed light on the conditions under which religion may impede trans rights advancements. In those cases (i.e., where religion in society is high), activists may have to dedicate additional resources or undertake different strategies to advance rights protections successfully. While a more secular society is potentially more amenable to progressive trans rights, secularization is not a quick process and attempts to convert adherents to or from a religion should not be the goal. Instead, activists may seek to find ways to demonstrate the compatibility between a religious society and one with equal rights for transgender people. Importantly, however, this is not a recommendation to pursue a “respectability politics” strategy that forces hetero-/cisnormative compliance from the trans community (Higginbotham Reference Higginbotham1993; Jones Reference Jones2022). Instead, strategies might aim to help deconstruct religiously inspired rigid gender norms and curb their presence in policy.

In terms of scholarly contributions, this article, first and foremost, provides an empirical examination of trans-specific legal rights – a topic historically understudied in cross-national political science research. This work is among the first to investigate the nuances of the relationship between religion and transgender rights on a global scale, providing a foundation for future research. Additionally, the findings from this analysis contribute to a broader understanding of the relationship between religion and gender. The hypotheses underlying this study were built around the idea that the religious traditions explored here often view gender as a binary, static concept intrinsically linked to an individual’s birth-assigned sex. The results support this assumption, as the negative relationships uncovered through the analyses suggest that religious perspectives on gender tend to be rooted in cisnormative beliefs. These beliefs then appear to influence the development of legal frameworks concerning gender-related politics, such as transgender rights or even issues like abortion and same-sex marriage.

While this article serves as one step towards better understanding the global variation in transgender rights, several of the findings also raised additional questions that still need to be addressed. For one, all measures of the specific religious populations were significant and negative, except for the one measuring the percentage of the Jewish population. The coefficient for this variable (Table 3, model 8) is 0.257, which is positive and quite substantial for this model. This result is primarily driven by the inclusion of Israel, which is the only country in the sample with a sizable Jewish population. The coefficient becomes negative once Israel is removed from the sample (Table A8). However, this result should also be interpreted cautiously, given the low concentration of Jewish populations in the other observations. Additional research, particularly work utilizing qualitative methods, is necessary to unpack the connection between Judaism and transgender rights.

While the positive and significant coefficients for Eastern Europe and Central Asia in some models may seem perplexing, the legacy of communism in the region may help contextualize these results. During communist rule, many governments worked to suppress religion in the public and private spheres (Pew Research Center 2017). This diminished influence of religion then helped create opportunities for more progressive rights, or at least helped prevent or slow down the adoption of harmful laws against the community. However, it is worth noting that the positive relationship for this region is only present in models capturing religion-state measures. Future work is necessary to unpack the regional-specific findings further.

Finally, though the results largely support a negative relationship, religion is incredibly complex and varied. Even within religious traditions that have historically treated gender as a fixed, binary concept tied to birth-assigned sex, there are examples of reinterpretations and adaptations over time. The case of Iran illustrates this point well, as religious authorities redefined the permissibility of gender-affirming surgeries within an Islamic framework. Though transgender rights have a long way to go in Iran, this shift highlights the potential for religious thought and practice to evolve. In sum, the relationship between religion and gender is dynamic, and this complexity should continue to be explored in future research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X25000078.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Amanda B. Edgell, Christopher W. Hale, Elif Kalaycioglu, Waleed Hazbun, Victor Asal, and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback and support.

Competing interest

The author declares none.