Archaeology as a discipline continues to overemphasize the importance of strenuous physical labor and mental toughness required of survey and excavation (Browman Reference Browman2013; Eskenazi and Herzog Reference Eskenazi and Herzog2020; Hamilton Reference Hamilton, Hamilton, Whitehouse and Wright2007; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018; Radde Reference Radde2018; Voss Reference Voss2021). As Laura Heath-Stout puts it:

Our macho, “cowboys of science” mentality leads archaeologists to emphasize our ruggedness and physicality. . . . We often respond by . . . emphasizing our strength and willingness to do physically demanding tasks in order to demonstrate that we belong. We have internalized the idea that physical strength is an essential part of being an archaeologist [Reference Heath-Stout2024:60].

The perception that archaeology is hard work undertaken by tough people has a long history rooted in the understanding of archaeology as comprised primarily of fieldwork. The prominence of toughness in archaeology has been attributed to wide-ranging and overlapping factors: class conflicts (McGuire and Walker Reference McGuire and Walker1999), homophobia and heteronormativity (Blackmore et al. Reference Blackmore, Drane, Baldwin and Ellis2016; Claassen Reference Claassen1994, Reference Claassen2000), masculinity (Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994; Gero Reference Gero1985; Neumann et al. Reference Neumann, Sanford and Harry2010:28; Woodall and Perricone Reference Woodall and Perricone1981), the disciplines’ “gray zones” (Markert et al. Reference Markert, Hodgetts, Cantin, Gauthier, Lyons, Supernant, Welch, Wiley and Dent2025), racism (White and Draycott Reference White and Draycott2020), and a combination of factors (d’Alpoim Guedes et al. Reference d’Alpoim Guedes, Gonzalez and Rivera-Collazo2021; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024; Leighton Reference Leighton2020; Moser Reference Moser2007; Overholtzer and Jalbert Reference Overholtzer and Jalbert2021). We suggest that archaeology’s disciplinary culture (sensu Moser Reference Moser2007) is usefully contextualized as one focused on toughness (both physical and mental), and that this culture has become normalized and negatively impacts archaeologists, particularly during fieldwork.

Although fieldwork is only one setting in which archaeological knowledge is produced (Gero Reference Gero1985; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024), it remains core to the identity of archaeology and is a key entry point to the discipline. Success in fieldwork is linked to career advancement in all archaeological sectors (i.e., cultural resource management [CRM], academia, and agency), though the pace, frequency, duration, and requirements of fieldwork differ across sectors. Consequently, fieldwork experiences can impact who begins and who continues a career in the discipline, and understanding how the culture of toughness presents during fieldwork is an opportunity to evaluate how these issues have explicitly and implicitly excluded archaeologists. The expectations and rules of behavior in archaeology, particularly in fieldwork settings, are rarely made explicit. Here, we find Mary Leighton’s (Reference Leighton2020) notion of performative informality a useful theoretical frame for understanding how this problematic culture is normalized and perpetuated. Performative informality is the concept that “an individual’s success depends on inhabiting or enacting that professional community’s specific kind of informality correctly” (Leighton Reference Leighton2020:445). As Leighton argues, the informality of archaeology is a mechanism for maintaining the status quo of dangerous field conditions and harassment (Leighton Reference Leighton2020), making archaeologists who perform the correct “cultural fit” more likely to be seen as suitable for fieldwork, regardless of their other abilities. We suggest that performative informality is the primary mechanism by which uncomfortable, unsafe, and unstructured field situations are normalized and speaking out against them becomes a violation of the unspoken rules of performance. Through this frame, enacting the culture of toughness correctly by emphasizing physical ability and accepting inappropriate or discriminatory banter becomes a requirement for success, and failure to enact this properly can result in a loss of enjoyment in archaeology, a stymied career, and physical and psychological injury.

This article presents the preliminary results of a quantitative survey designed to understand the relationship between demographics and field experiences. To understand how toughness is manifest in archaeological fieldwork, we investigated the prevalence of discrimination, and pressure to accept inappropriate behaviors and to push oneself physically, mentally, and emotionally. We selected these particular behaviors to understand the culture of toughness in archaeology because they exemplify the subtle ways archaeologists measure themselves and are measured as tough. That is, by measuring discrimination and the pressure archaeologists feel to push themselves and accept negative behaviors, we hope to illuminate the scale of this issue and identify impacted archaeologists. What we are not measuring is the toughness of archaeologists themselves; instead, we contend that the work of archaeology—both in and out of the field—is tough enough without the additional pressure to perform toughness. Our results indicate this culture of toughness impacts archaeologists primarily along gendered lines, when compared against age, archaeological sector, sexual orientation, and ethnicity. We further offer possible solutions for addressing problematic cultural norms in the field.

Background: “The Most Toxic Part of the Field . . .”

This work is inspired by and builds on the work of several previous surveys.Footnote 1 Many of these studies have been reviewed in-depth by Barbara Voss (Reference Voss2021) and Amber VanDerwarker (Reference VanDerwarker and Geller2024); however, a short review of the current work is offered as it relates to this project. Although our survey was designed to understand nuanced negative behaviors in archaeological fieldwork, an overview of these surveys (which have primarily centered on the prevalence of sexual assault, harassment, and bullying) is a critical starting point. Surveys related to sexual assault and harassment in the field sciences began in 2013 with the Survey of Academic Field Experiences (SAFE), which found that 70% of women had experienced harassment, compared with 40% of men for scientists across disciplines. SAFE also found that 26% of women and 6% of men had been sexually assaulted during fieldwork (Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014), and these assaults were most often perpetrated by members of the research team (rather than members of the community or strangers) against research team members in lower power positions (i.e., students, postdoctoral researchers, and employees; Clancy et al. Reference Clancy, Nelson, Rutherford and Hinde2014:4). These findings spurred research into discrimination and harassment in archaeology specifically. Surveys in archaeology related to assault, harassment, and bullying in archaeology are numerous and range in scope between regional archaeological societies (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2018; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018; Radde Reference Radde2018; VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018), individual countries (Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020), research regions (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024), and internationally (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023). Numbers of respondents, archaeological sector, sexual orientation, gender, and information on surveyed populations for each survey are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Compiled Data from This and Previous Related Surveys for Comparison.

a Our other category includes archaeologists who are unemployed, working in related and unrelated fields, and employed by Tribal organizations and agencies, museums and repositories, and as independent contractors (see Figure 1).

b Each survey used slightly different methodology when calculating percentage of respondents. Some calculated based only on respondents to questions while others included non-respondents in percentages. This table reflects the percentages reported in each survey and notes differences where relevant.

c Meyers and colleagues provided only male and female as gender options in their survey.

d Radde (Reference Radde2018) and Vanderwarker and others (Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018) segment CRM into three subcategories which we have reclassified. Specifically, their categories were changed from Private CRM and subcontract CRM to CRM, Public CRM to agency, and Tribal CRM, museum employees, retired, and others to the ‘other’ category. Percentages were calculated by the author using Table 4 in VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018 which reported data for both surveys.

e Radde (Reference Radde2018:233) uses the category “non-heteronormative” which includes asexual, bisexual, homosexual, questioning, and other (VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018:142-143).

f The SCA surveys use the category “transgender” rather than non-binary (Radde Reference Radde2018:233; VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018:139).

g Categories from Hodgetts and colleagues (Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020) were recategorized: Private CRM to CRM, Canadian government agencies to agency, and Indigenous governments and organizations, museums, avocational archaeologists, and other employers to the ‘other’ category. Hodgetts and colleagues (Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020:30) additionally note that “[b]ecause respondents could select more than one sector, we calculated percentages based on the total number of responses (N=600) rather than the number of respondents.”

h Hodgetts and colleagues’ (Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020:28) LGBTQ+ category comprises bisexual, asexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, other, and questioning.

i Hodgetts and colleagues (Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020:27) use the term “non-binary” to encompass “all respondents who self identified as something other than woman / female or man / male, and includes responses of ‘non-binary’, ‘bigender’, ‘kinda male’, ‘genderqueer’, and ‘trans man’.”

j Bradford and Crema (Reference Bradford and Crema2022:551) include non-respondents in their proportions of sexuality and gender; thus, the total reported in this table is less than 100% for both sexuality and gender.

k Coltofean-Arizancu and colleagues’ use the category “other” which comprises “no answer, non-binary, agender, and gender queer people” (Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023:730).

l Heath-Stout expanded her initial qualitative survey of 72 individuals to include 102 total interviews; however, some interviewees were interviewed more than once. Thus, the data presented here are adapted from the table of 72 initial respondents (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024:10)

m The non-heterosexual category in Heath-Stout’s (Reference Heath-Stout2024:10) survey comprises those who identified as gay, bisexual, queer, and complicated.

n Heath-Stout’s respondents are a “Transgender man” and a “Genderfluid Person” (Reference Heath-Stout2024:10), hence the label “non-cisgendered” may or may not apply to them.

Conducted between 2014 and 2021, these surveys have shown that women (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018; Radde Reference Radde2018), LGBTQ+ (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Radde Reference Radde2018), and those employed in entry-level positions such as field technicians and students (Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020) experience the highest rates of sexual assault and of sexual and nonsexual harassment and bullying in the discipline. These studies further show that not only are sexual assault, harassment, and bullying experiences relatively common during archaeological fieldwork but that sexual misconduct incidents also occur in office settings (Radde Reference Radde2018) and are more likely to occur on projects where protocols related to misconduct do not exist or are unclear (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017). Many of these surveys investigated multiple axes of identity individually (e.g., gender, sexual orientation, archaeological sector, job title); however, work to understand the intersections of these identities related to experiences in archaeology is emerging. Notably, Heath-Stout and Patricia Markert and colleagues have recently conducted qualitative interviews aimed at understanding how intersectional identities create differential experiences (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024; Markert et al. Reference Markert, Hodgetts, Cantin, Gauthier, Lyons, Supernant, Welch, Wiley and Dent2025).

Taken together, the previous surveys unequivocally document a culture of sexual harassment and assault, nonsexual harassment, and bullying in archaeology across sectors and geographies. These surveys indicate that women, LGBTQ+, and entry-level archaeologists experience the highest proportion of attacks and that the causal factors for this are myriad, including insufficient protocols related to inappropriate behaviors (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017), nonexistent or broken reporting mechanisms (Radde Reference Radde2018; VanDerwarker Reference VanDerwarker and Geller2024), lack of female and other minority mentorship relationships (Brown Reference Brown2018), an overemphasis on gendered roles in task and job assignments (Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2018), and a combination of these and more factors (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024; Markert et al. Reference Markert, Hodgetts, Cantin, Gauthier, Lyons, Supernant, Welch, Wiley and Dent2025). The high correspondence between these datasets inspired us to assess how these incidents and behaviors may be manifested in insidious and less overt ways outside of sexual and nonsexual assault and harassment.

The survey presented in this article diverges in key ways from the previous surveys described above. (1) This survey was conducted four years after the most recent quantitative survey (Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023) and 11 years since the first (Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018), providing insight into whether illuminating differential experiences for women and LGBTQ+ archaeologists has changed their prevalence in the discipline. (2) This survey focuses not on sexual assault, harassment, and bullying but rather on nuanced aspects related to the culture of toughness: discrimination, pressure to accept inappropriate behaviors and to push beyond mental, physical, and emotional limits. (3) This survey asks respondents why they consider leaving archaeology and about their insights into how to improve the field.

Survey Design and Dissemination

The survey was designed using Qualtrics software licensed through the University of Colorado Boulder (CU). The survey, project design, and recruitment processes were approved by the CU Institutional Review Board (IRB) for human research under the exemption protocol (Protocol #24-0818). To increase the likelihood of complete responses, the survey was designed with a duration of 10 to 15 minutes, as determined by Qualtrics software estimates. Following initial design, the survey was reviewed by volunteer CRM and agency-sector archaeologists, and their comments were incorporated in the survey design.

The survey collected demographic informationFootnote 2 before proceeding to questions about fieldwork experiences to allow comparison between demographics and experiences. The demographic information collected was vast and will not be fully explored in this analysis: age, race/ethnicity (following US census categories), gender identity, sexual orientation, marital status, caregiving status, years in archaeology, membership in professional archaeological organizations, education level, employment status, current employer type, presence/absence of fieldwork, and job title.

Questions about field experiences were asked in two parts, a strategy similarly employed by Hodgetts and colleagues (Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020:25). Respondents were first asked to select yes, no, or unsure relative to their experiences for each category. Respondents who answered yes were asked follow-up questions. These follow-up questions allowed the selection of numerous responses to capture the range of respondent experiences, reduce survey completion time for those who answered no/unsure, and identify broad trends rather than one-to-one examples of negative experiences.

All but the last two questions of the survey were multiple choice and included answers designed to capture a range of experiences and viewpoints. Additionally, “I don’t know / I’m not sure / None of these” was provided to allow respondents to acknowledge the question without providing a definitive answer. To reduce potential bias in survey responses, the display order of all multiple choice answers beyond demographics was randomized, except for “Other (please specify)” and “None of these,” which always appeared at the bottom of response options. Two open-response text boxes offered respondents opportunities to express their ideas and opinions for two questions: (1) What factors have contributed to positive fieldwork experiences for you? and (2) What recommendations would you make to those looking to improve archaeology, particularly fieldwork?

The survey was distributed using a snowball sampling strategy. Initial calls for survey participation were conducted using social media (i.e., the Archaeo Field Techs Facebook group comprised of over 5,000 current and former archaeologists, LinkedIn, and BlueSky) and email. Posts created by and citing the corresponding author as the principal investigator (per CU IRB protocols) were shared and reshared with users outside of the authors’ networks. An email solicitation was sent to the corresponding authors of this themed issue, which was subsequently shared across unconnected networks through email and social media. The survey was not formally solicited through any archaeological societies and organizations in order to capture archaeologists who are not members of these, which have historically been the basis for such surveys (Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018; Radde Reference Radde2018; VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018). This strategy was effective, resulting in nearly one-third of respondents (27.2%) without affiliation to an archaeological society or organization. Places of employment were not solicited as points of survey dispersal to avoid employers attempting to skew survey results (e.g., by sending only to employees with high satisfaction rates, higher status, etc.).

Respondents self-selected for inclusion in the survey by identifying themselves as current or former archaeologists with fieldwork experience. Rather than limiting respondents to those working or living in the United States, this survey allowed responses from all geographies in recognition that archaeologists frequently work outside of their home countries or regions.

The survey opened on January 7, 2025, and the analysis presented here was undertaken from data collected through April 6, 2025, resulting in 566 complete or nearly complete responses. The survey was officially closed July 7, 2025.

Statistical Analysis

To determine how demographic categories relate to each question, we employed a series of chi-square tests of significance to understand the relationship between responses and demographics. Approaching the analysis in this way allowed us to evaluate each factor for significance to provide a basis for future statistical analyses related to intersectional identities. Intersectional research originated in Black Feminist theory to explain how Black women’s experiences could not be realized “within the traditional boundaries of race or gender discrimination as these boundaries are currently understood” (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1991:1242) but required, instead, a lens that approaches these categories as interacting, additive, and complex (Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989, Reference Crenshaw1991). Intersectionality has since been applied to myriad contexts as an analytic which “views categories of race, class, gender, sexuality, class, nation, ability, ethnicity, and age—among others—as interrelated and mutually shaping one another” (Collins and Bilge Reference Collins and Bilge2020:2). Applying intersectional analyses to quantitative data is complex, and the methods for doing so are evolving (e.g., Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Churchill, Mahendran, Walwyn, Lizotte and Villa-Rueda2021; Bowleg Reference Bowleg2008; Bowleg and Bauer Reference Bowleg and Bauer2016; Cole Reference Cole2009; Collins and Bilge Reference Collins and Bilge2020; Else-Quest and Shibley Hyde Reference Else-Quest and Hyde2016; McCall Reference McCall2005; Nash Reference Nash2008). Complicating factors such as legibility, self-perception, and outward perception make understanding respondents’ intersectional identities and complex experiences difficult to ascertain from quantitative survey data alone. Beyond the difficulty in parsing intersectional identities from quantitative data, analyzing our survey data variable by variable provides an initial baseline of results and allows direct comparison between the experiences of our respondents and those of previous quantitative surveys. We present the results for our entire survey population, breaking out categories only where statistically significant deviations exist.

We conducted chi-square tests of independence for each question against five demographic categories: age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, job sector, and gender. These five factors were evaluated for all questions. To account for the low diversity of respondents for ethnicity, sexual orientation, and job sector, these were collapsed into broader categories: white and nonwhite/mixed, straight and/or heterosexual and nonheterosexual, and CRM, Academia, and Other. Only gender and job sector showed statistically significant results, and are detailed below.

Survey Results: “Who Am I to Express Dissent or Put forward Ideas?”

Demographics

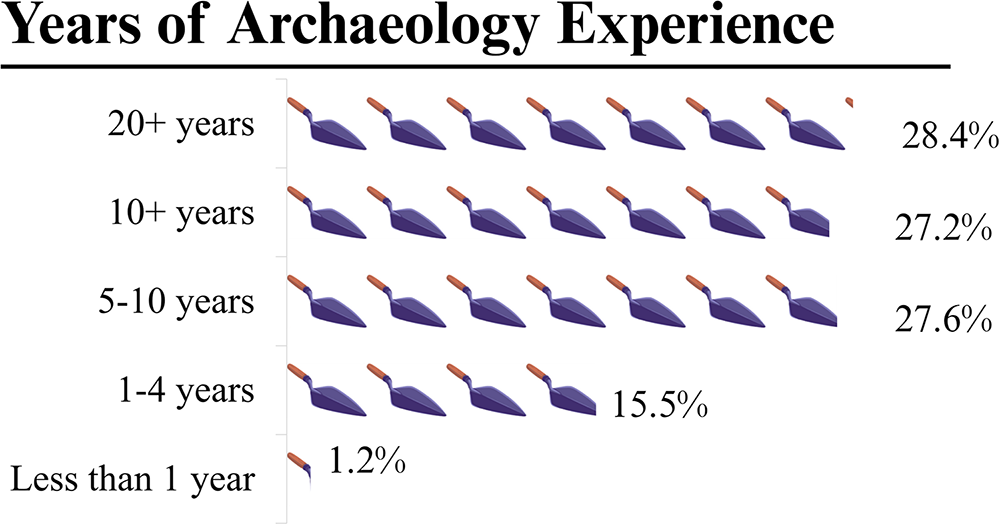

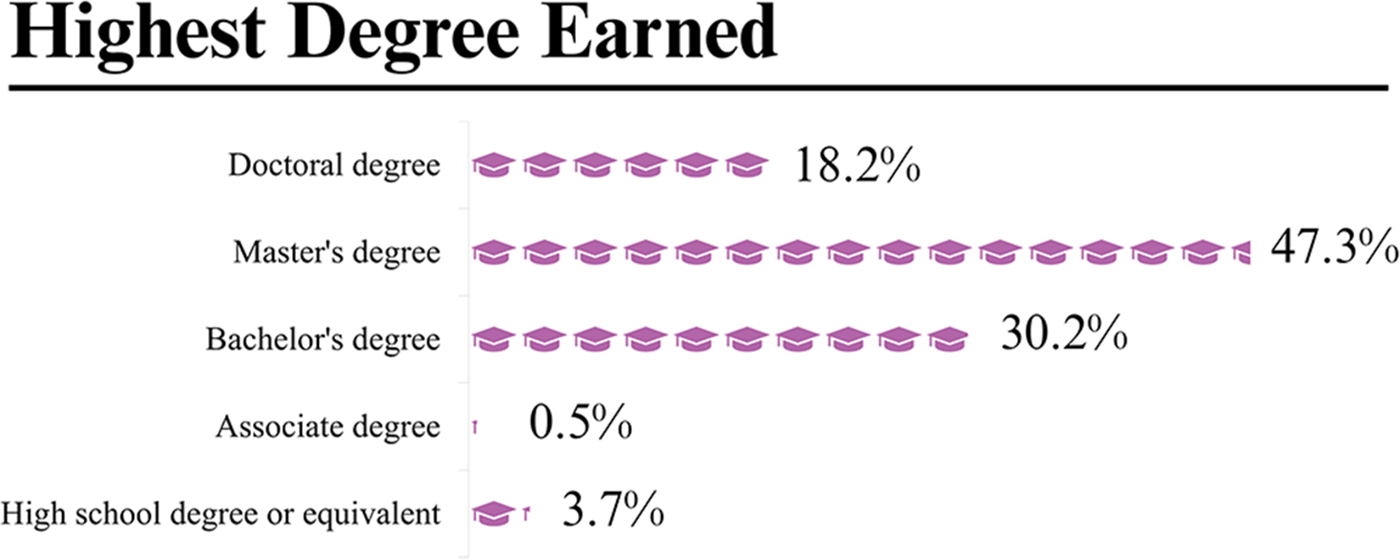

Demographic questions aimed to capture a range of data about respondents. Because no questions were mandatory, not all respondents answered all questions. Non-respondents were excluded from the analysis; percentages therefore reflect only the proportion of respondents for each question. Figure 1 visualizes the demographic factors used in our statistical analysis: gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, and sector. Most respondents identify as white (n = 457; 82.8%), female (n = 359; 63.5%), and straight and/or heterosexual (n = 395; 70.6%). Due to the low number of respondents who identify as nonbinary, transgender, and two or more gender identities, these responses were grouped together and categorized as “noncisgendered” (n = 18; 3.2%). The most common employers are CRM firms (n = 263; 46.5%), followed by colleges/universities (n = 100; 17.7%), federal/local/state agencies (n = 90; 15.9%), museums/repositories (n = 25; 4.4%), and unrelated fields (n = 21; 3.7%). A range of experience and education levels was captured, represented in Figure 2 and Figure 3, respectively.

Figure 1. Gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, age, and archaeological sector of respondents.

Figure 2. Years of archaeology experience of respondents.

Figure 3. Highest degree earned by respondents.

Demographic data captured by our survey correspond to those of similar studies (see Table 1 for comparison with other surveys), including the skew of respondents in ways that deviate from actual distributions and in the overrepresentation of white archaeologists, which aligns with the real distribution (Aitchison et al. Reference Aitchison, German and Rocks-Macqueen2021; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Society for American Archaeology 2021). Two demographic factors in our data deviate from the real distribution of archaeologists: job sector and gender. CRM archaeologists significantly outnumber academic archaeologists globally (Aitchison et al. Reference Aitchison, Alphas, Ameels, Bentz and Bors2014, Reference Aitchison, German and Rocks-Macqueen2021; Altschul and Klein Reference Altschul and Klein2022; Mate and Ulm Reference Mate and Ulm2021; Neumann et al. Reference Neumann, Sanford and Harry2010) but represent only 46.5% of our sample. Our survey reached more CRM archaeologists than similar surveys (Table 1) but failed to recruit a realistic proportion of CRM archaeologists, as they are likely underrepresented in online spaces such as LinkedIn (preferring instead archaeology-specific job boards) or Bluesky, and may not be readily reached through email forwards. Women also account for a higher proportion of respondents than the real distribution of archaeologists, estimated at closer to 50% globally (Aitchison et al. Reference Aitchison, Alphas, Ameels, Bentz and Bors2014, Reference Aitchison, German and Rocks-Macqueen2021; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Mate and Ulm Reference Mate and Ulm2021; Society for American Archaeology 2021). This is likely due to women’s higher participation in online surveys (Smith Reference Smith2008) and, as with previous surveys in archaeology, they may have been interested in sharing their experiences (Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020:28). Where our data are skewed but align with the demographics of archaeology (i.e., overrepresentation of white archaeologists) is cause for additional research, as the overall whiteness of archaeologists is likely related to the cultural issues examined in our study. Therefore, while our analysis investigates ethnicity (among other factors), it is possible that because our survey respondents are largely current archaeologists, those with negative field experiences along these axes of identity may have left the field and are therefore not adequately represented. Further investigation into the demographic skew of archaeologists beyond this survey could illuminate useful strategies toward reducing negative field experiences along several intersections.

Discrimination

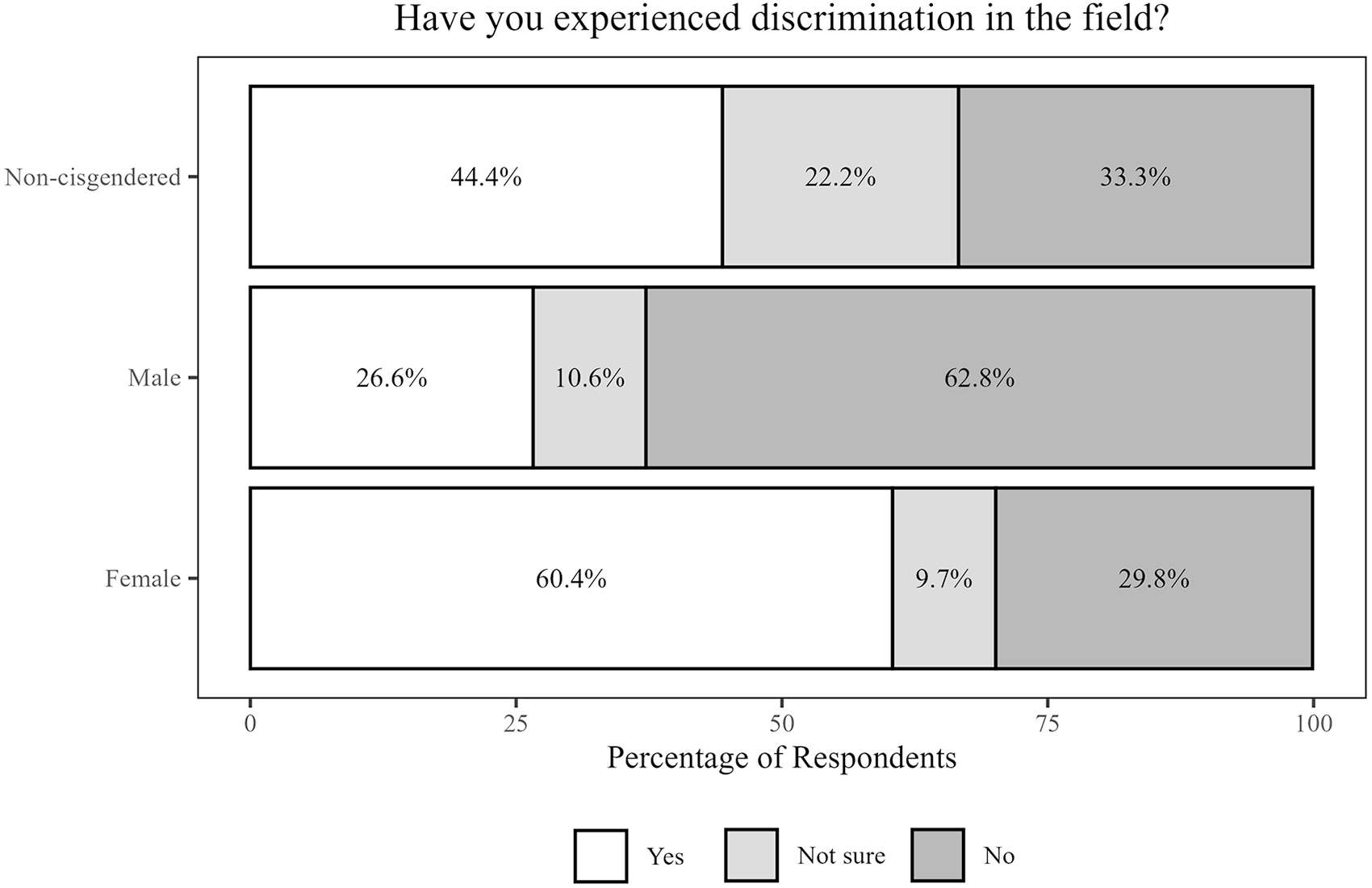

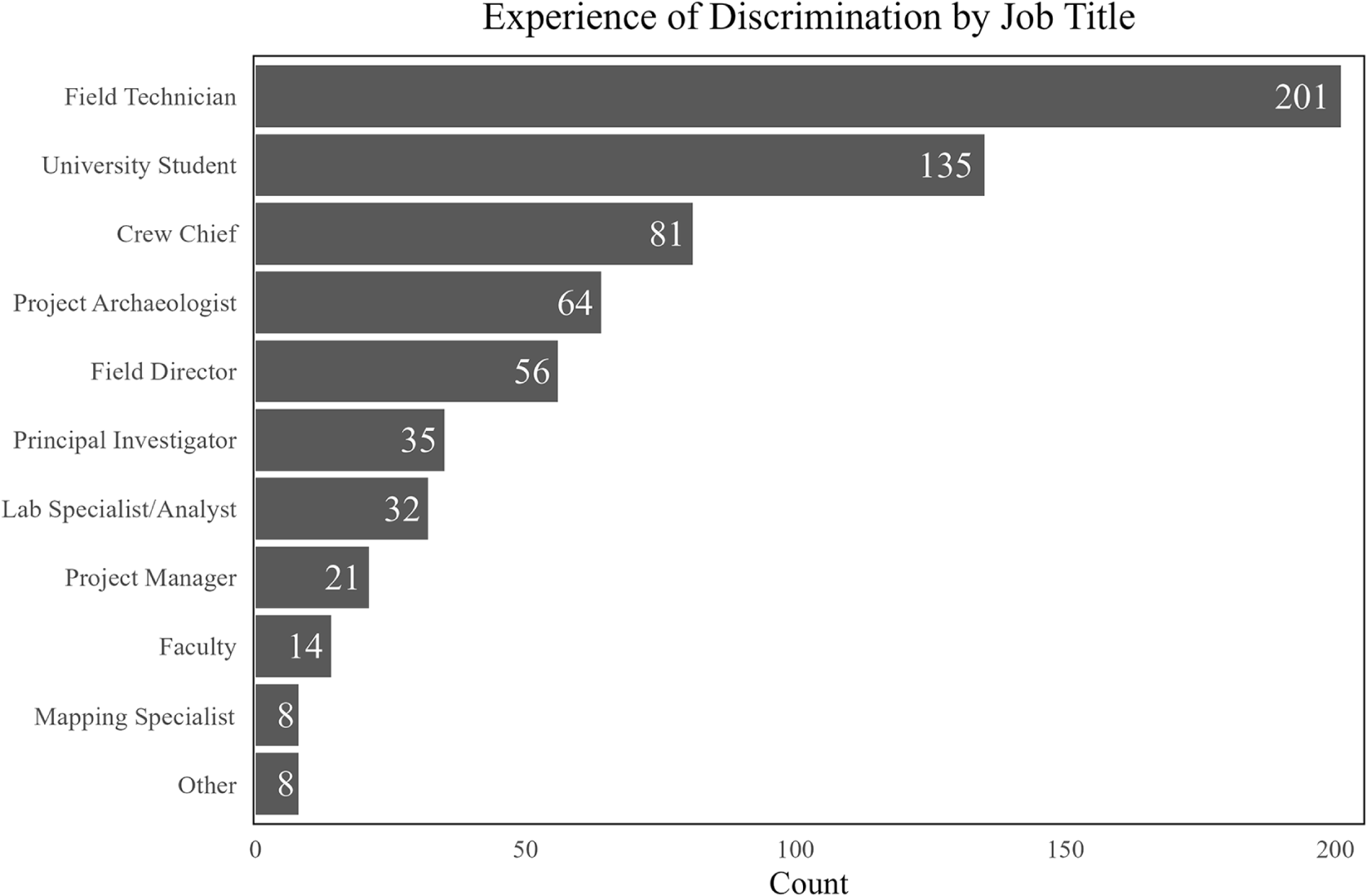

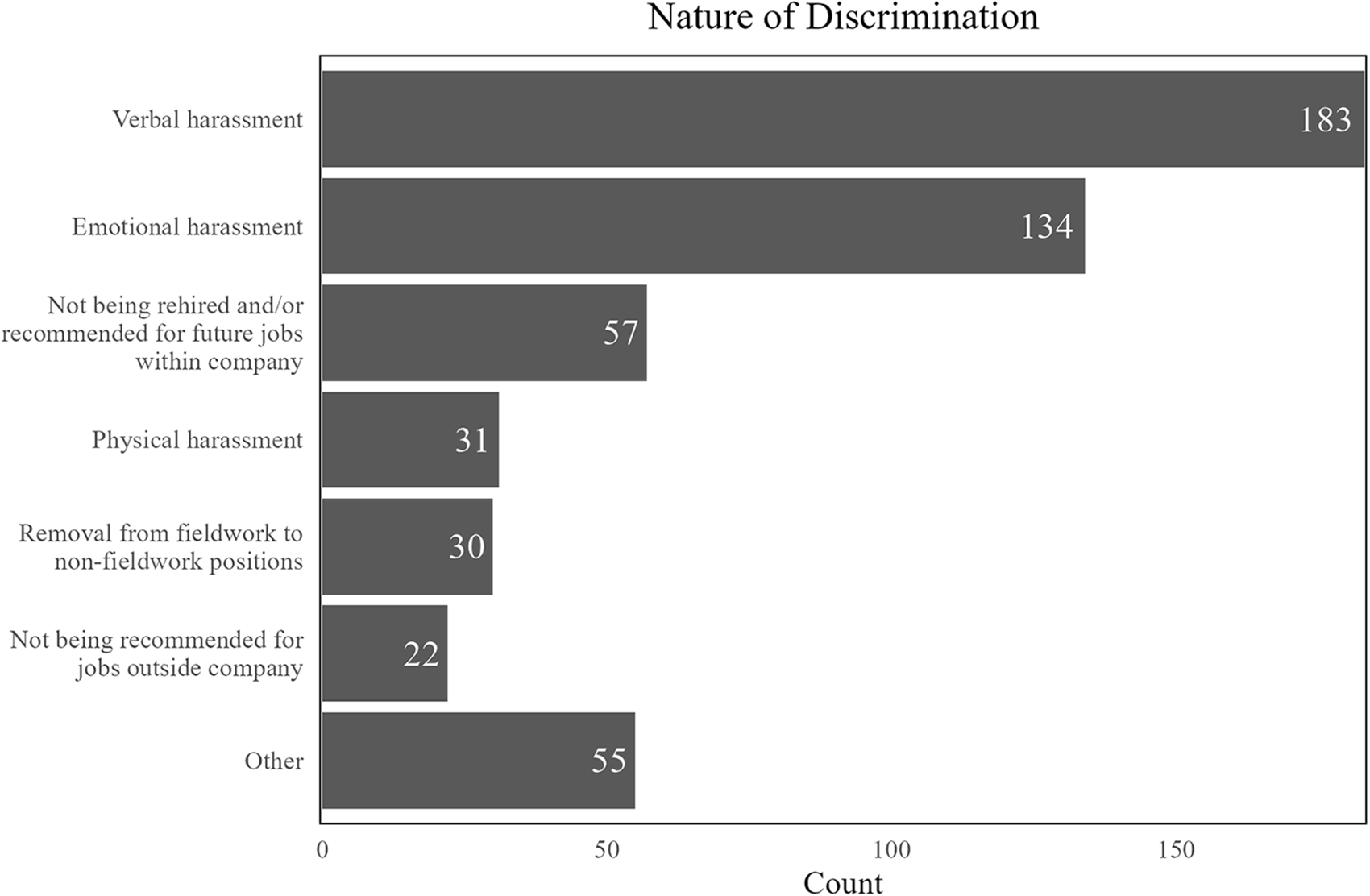

Respondents were asked questions that revolved around discrimination (defined as “the unjust or prejudicial treatment of different categories of people, especially based on age, disability, race/ethnicity, gender identity, sexual orientation, or physical appearance”). These data indicate that more archaeologists have experienced discrimination (48.7%, n = 275) than have not, or are unsure, and a majority of them are female (78.9%; n = 217), a finding aligned with previous survey results on sexual assault, harassment, and bullying (Brown Reference Brown2018; Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015, Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018; Radde Reference Radde2018; VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018). The proportion of each gender experiencing discrimination is statistically significant (ꭓ2 [4, n = 565] = 64.725, p < 0.001) and offers an additional insight: 60.4% of all female respondents and 44.4% of noncisgendered respondents have experienced discrimination, in contrast to the 26.6% of male archaeologists who indicated the same (Figure 4). Among those who indicated they had experienced discrimination, the highest proportion are employed in entry-level positions (i.e., field technicians and students), echoing the results of previous surveys on harassment, assault, and bullying (Figure 5). When asked about the basis of the discrimination they faced, gender identity/expression accounted for the highest proportion of responses for all genders, indicating that gender identity/expression is the top factor in differential treatment. Despite the prevalence of gender identity/expression as the basis of discrimination, it is worth noting that 64.1% of respondents chose more than one factor (most commonly age, education, and physical abilities), a finding that warrants further study in future intersectional analyses. With regard to the nature of discrimination, respondents of all genders identified the same top responses: verbal harassment and emotional harassment (Figure 6). These results suggest that verbal and emotional harassment are broad issues in archaeology, due to their prevalence among all respondents who have experienced discrimination. Enduring high proportions of discrimination, particularly verbal and emotional harassment, is yet another way that archaeologists must prove they are tough enough for the discipline. Finally, respondents who faced discrimination were asked whether they had the means to report their experiences. The results show a nearly equal split between “No, I could not report as there was no reporting structure” (n = 89; 32.3%) and “Yes, I could report but I had reason to fear retaliation or loss of wages/future job opportunities” (n = 86; 31.3%). Further, the frequency and content of pre-field health and safety meetings were investigated, given that previous survey work on sexual assault and harassment indicates higher prevalence in field settings with unclear or nonexistent protocols for behavior or reporting (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017). Most respondents (62.1%, n = 352) indicated they had been briefed in a majority (>50%) of field experiences and indicated that the four most prevalent topics are related to physical injury and that those topics reported least frequently were amenities/protocols for menstruation, Workers’ Compensation procedures, and the availability of an ombudsperson / human resources representative (Figure 7). These data suggest the informality of archaeology allows lax or unreliable reporting structures and provides inadequate briefing on procedures for seeking redress (e.g., through human resources or insurance), indicating there is a gap between experiences of discrimination and procedures and protocols for addressing such issues in health and safety meetings.

Figure 4. Respondents who have experienced discrimination, normalized to the total proportion of respondents in each gender.

Figure 5. Positions in which respondents faced discrimination.

Figure 6. The nature of discrimination faced by all respondents who indicated they have faced discrimination.

Figure 7. Topics covered in health and safety meetings.

Inappropriate Behaviors

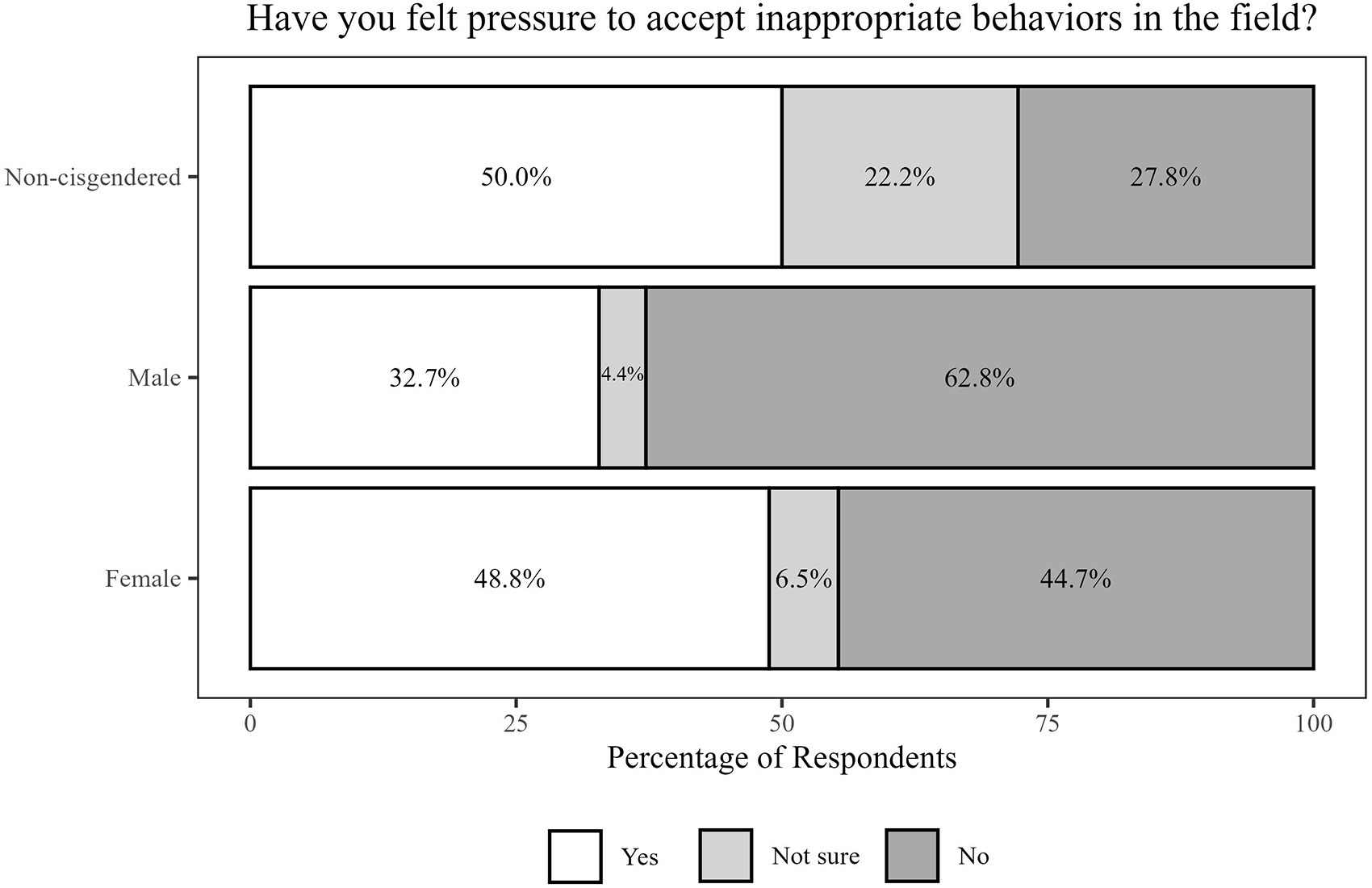

To explore other ways archaeologists may experience the culture of toughness during fieldwork, respondents were asked about whether they felt external pressure to accept sexist, homophobic, ableist, or otherwise inappropriate behavior. This question is related to the Society for California Archaeology (SCA) Gender Equity and Sexual Harrassment survey that indicated “banter, teasing, [and] flippant remarks” are perceived as intrinsic to archaeology (Radde Reference Radde2018:246). Thus, a goal of this survey was to understand whether or not individuals felt pressured to accept these behaviors and whether they were perceived as standard behaviors during fieldwork. Analysis of all respondents who answered this question (N = 539) indicates that a narrow majority do not feel pressured to accept these behaviors (n = 270; 50.1%), followed by those who do (n = 235; 43.6%) and those who were not sure (n = 34; 6.3%). There is a statistically significant difference between genders (χ2 = 24.887, df = 4, p <0.01; Figure 8): a majority of female (48.8%) and noncisgendered (50.0%) respondents felt pressure to accept these behaviors, whereas only a minority of male respondents (32.7%) felt the same pressure. The majority of those who had experienced this pressure noted they were field technicians and/or students at the time. This indicates that where professional norms are concerned, women and noncisgendered archaeologists experience fieldwork culture differently from their male counterparts, and that this difference is most common in entry-level positions. As with discrimination, it is both women and noncisgendered archaeologists, and those with the least authority, who more often experience the pressure to accept sexist, racist, homophobic, ableist, and inappropriate behaviors. This suggests women and noncisgendered archaeologists are disproportionately impacted by this norm, resulting in field environments that feel welcoming and fun to some but hostile and emotionally fraught to others.

Figure 8. Pressure to accept sexist, homophobic, ableist, or otherwise inappropriate behavior by gender, normalized to the total proportion of respondents in each gender category.

Pressure to Push beyond Physical, Mental, or Emotional Limits

Respondents were asked whether they had ever felt pressure to push beyond their physical, mental, and/or emotional limits and, if so, whether any negative outcomes resulted. A majority of respondents (n = 487; 86.0%) indicated they felt pressure to push themselves beyond their limits. Anticipating that the source of the pressures would be variable, respondents were asked to further identify the source of the pressure to push themselves. For 49.4% (n = 269) of respondents, the pressure to push themselves was both internal and external, 21.5% (n = 117) were only self-pressured, and 18.5% (n = 101) were only externally pressured. A minority 10.5%; (n = 57) indicated they had never felt pressured. When analyzed by the proportion of each gender (Table 2), the proportions are nearly equal across genders for those who indicated they felt pressured by both external forces and themselves and those who felt internal pressure and wanted to push themselves or were uncomfortable doing so (though a slightly higher percentage of noncisgendered and male archaeologists indicated they were uncomfortable pushing themselves relative to their female counterparts). Conversely, slightly more male respondents (14.4%) than female (8.7%) or noncisgendered (5.6%) reported never feeling pressured, possibly indicating differential expectations or norms across genders. These data largely show congruence between genders, suggesting that a majority of archaeologists feel their success as an archaeologist is linked to performing toughness, even if it means putting oneself at risk. As a respondent put it: “I, as a male, was pigeonholed into fieldwork, cut out of research and writing opportunities due to being the male tech, so I had to do the dangerous jobs with inadequate safety procedures.” The overall similarity between genders and feeling pressured to push physically, mentally, or emotionally indicates there is a systemic issue in archaeological fieldwork related to its emphasis on toughness and physicality.

Table 2. Proportion of Each Gender Who Selected Each Pressure-to-Push Category.

Those who felt pressure to push themselves beyond their limits (N = 487) were asked to select the consequences of doing so: emotional/mental distress, physical injury, loss of interest/enjoyment, loss of job opportunities, loss of wages, decrease in quality of work, and other (with optional text response). Because multiple answers could be selected, more responses than individuals were gathered for this metric (N = 1,014), and a majority selected a negative consequence (n = 426; 87.4%). Respondents selected emotional/mental distress (n = 289), a loss of interest/enjoyment (n = 212), decrease in quality of work (n = 186), and physical injury (n = 183) as the most common outcomes. Analyzing these results by gender shows no significant difference, signifying that there is no meaningful difference in attitude, effort, or negative consequences between genders. However, when analyzed by sector, emotional/mental distress and decrease in quality of work show a statistically significant difference for those employed in CRM (χ2 = 29.018, df = 9, p < 0.01 and χ2 = 19.427, df = 9, p = 0.02), indicating distress and decreased work quality are more prevalent consequences in CRM than other sectors (Figure 9). It is important to note that while we asked about negative consequences, we received a range of attitudes about the pressure to push in free responses. Some viewed the pressure negatively, with one respondent indicating, “I think this mindset is dangerous and makes it difficult for people to advocate for themselves.” Others viewed the pressure to push themselves positively, even when associated with negative consequences, with one respondent noting, “I very much like the cut-throat nature of the fieldwork.” While these views were not the majority, highlighting them is critical to understanding the range of attitudes related to archaeology’s culture of toughness and how the culture is perpetuated.

Figure 9. Highest proportion and statistically significant results of pushing oneself during fieldwork, showing proportion of respondents in each sector.

Reasons for Considering Different Careers

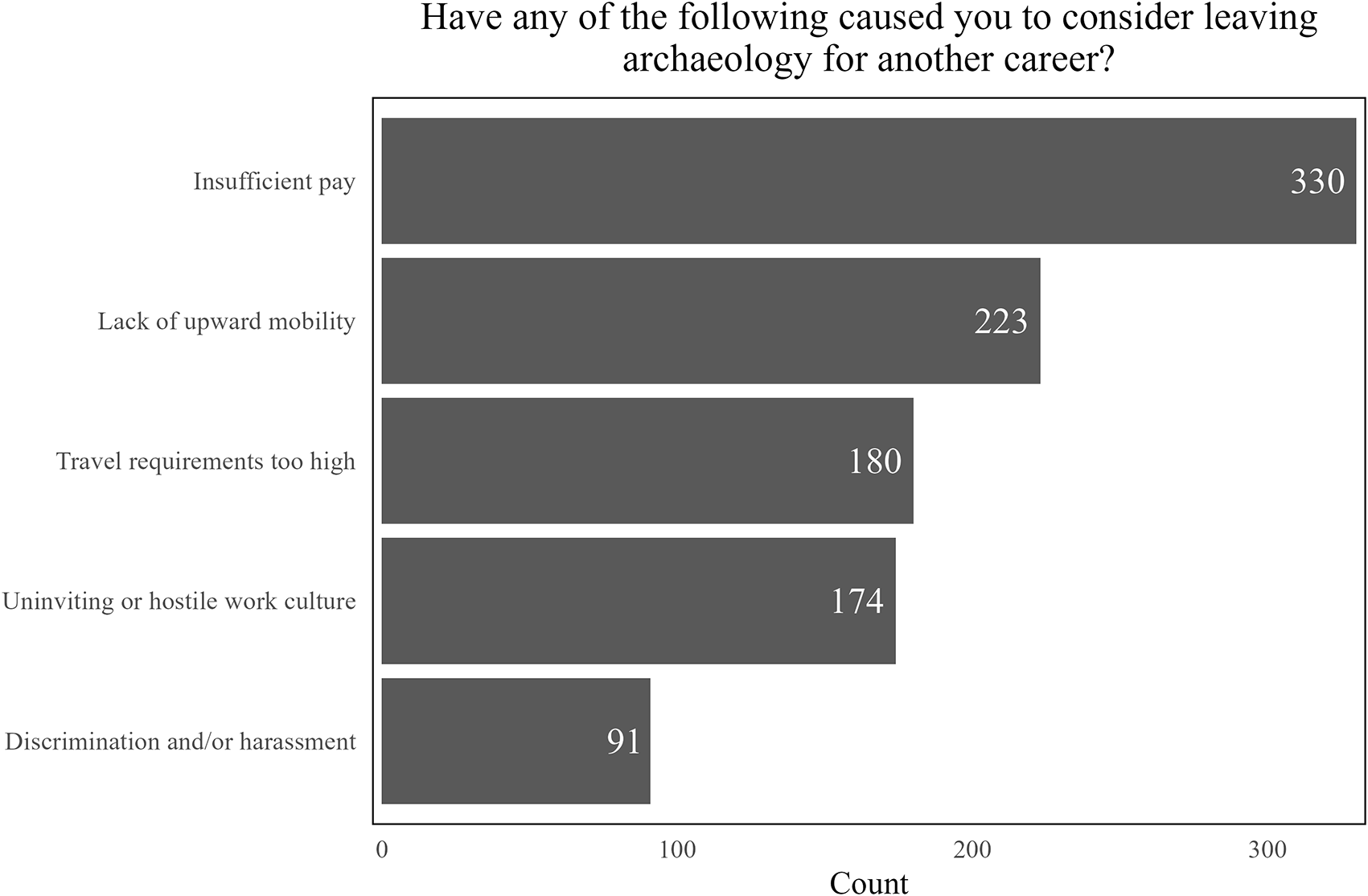

Respondents were asked to select all the reasons for which they consider leaving archaeology as a career (Figure 10). Insufficient pay, lack of upward mobility, and inconsistent work were the most common responses, with insufficient pay accounting for over 100 more responses than the next highest category. However, though it was not a top choice, only discrimination and harassment (16.1% of responses; n = 91) was statistically significant (χ2 = 8.9769, df = 3, p = 0.03). Of respondents who selected discrimination and harassment, 78.0% (n = 71) are women, while 18.7% (n = 17) are men, and 3.3% (n = 3) are noncisgendered people (Figure 11). An analysis by proportion of each gender indicates women and noncisgendered people selected this reason at approximately twice the rate of men (19.8% of women; 16.7% of noncisgendered people, compared with 9.0% of men), indicating they are nearly twice as likely as their male counterparts to consider leaving the discipline owing to discrimination and harassment (Table 3). When “years of experience” is factored into the analysis, we find that although a consistent proportion of archaeologists at all experience levels chose discrimination and harassment as a factor, women increasingly cite it as a reason they contemplate leaving over time (Figure 12). This suggests that no matter how advanced or established one’s career is, the impact of discrimination and harassment causes female archaeologists to continually contemplate leaving. This accords with Meyers and colleagues’ (Reference Meyers, Horton, Boudreaux, Carmody and Wright2018) finding that showed sexual harassment became a more prominent factor for which women considered leaving specific job positions after 6–11 years. For noncisgendered archaeologists, these data indicate discrimination and harassment are a factor early in their careers (one to four years), which may cause them to leave the field; however, given the low proportion of these archaeologists in the sample (n = 18), more work is required to understand the impact of discrimination and harassment on noncisgendered archaeologists. Although archaeologists across demographics are largely aligned in the reasons for which they consider leaving the discipline, the discrimination endured by women and noncisgendered archaeologists disproportionately affects their willingness to remain in archaeology at all career stages. Unfortunately, this survey sample did not capture many former archaeologists, representing an area where targeted research is needed.

Figure 10. Reasons respondents have considered leaving the field.

Figure 11. Reasons for which respondents have considered leaving the field, normalized to the total proportion of respondents for each answer category.

Figure 12. Percentage of respondents who selected “discrimination and/or harassment” as a factor for which they consider leaving archaeology, showing a line for each gender category and a line for all respondents.

Table 3. Proportion of Each Gender Who Selected “Discrimination and/or Harassment” among the Reasons for Which They Decide to Leave.

Discussion: “We Need to Stop the Work Culture of Move until You Drop”

As our data have shown, those most affected by archaeology’s culture of toughness are women and noncisgendered archaeologists and those in entry-level positions. Additionally, though men do not experience discrimination at the same rates, the culture of toughness in archaeology harms everyone. Our results show that the culture of archaeology has several major issues requiring reflection and improvement. First, women and noncisgendered archaeologists (particularly those in field technician and student roles) experience the most discrimination. Second, women and noncisgendered archaeologists feel pressured to accept sexist, homophobic, ableist, or otherwise inappropriate behaviors during fieldwork. Third, the pressure to push beyond one’s physical, mental, or emotional limits is shared across genders. Finally, female archaeologists cite discrimination and harassment more often than men and noncisgendered archaeologists as reasons for which they consider leaving the discipline. The following section discusses survey respondents’ ideas on how to improve archaeological fieldwork, focusing on both institutional and individual suggestions, aimed at illuminating subtle informalities and replacing them with clearly stated expectations and necessary skillsets for success in the field.

Institutional Improvements

Recommendations for improving the discipline were solicited during the survey via a multiple choice, multiple selection question. Increased pay (n = 450), more competitive benefits (n = 440), reporting protocols that protect against retaliation (n = 321), and unionizing (n = 320) were the top responses. As one respondent succinctly put it: “Techs need to be treated with more respect. They are not just disposable hard labor. . . . We need regulations, worker’s rights, and respect.” This call for increased wages, benefits, and labor protections is an indication of the needs of archaeologists across sectors. As such, our proposed solutions are directly tied to the issue of performative informality, as they call for increased formality and recognition of workloads within the discipline. Potential and complementary suggestions toward improving these systemic issues are increased industry oversight, changes to training pedagogy for incoming archaeologists, and feedback and expectation-setting policies in fieldwork settings.

Currently, there is no mandatory oversight authority for archaeological organizations in the United States. Several organizations offer codes of conduct and protections for members in specific circumstances (e.g., the Society for American Archaeology, the Register of Professional Archaeologists, and the American Cultural Resource Association); however, membership is not mandatory, and therefore adherence to codes of conduct and protections cannot be uniformly applied or enforced. It is, in part, the current reliance on self-governance by CRM firms, agencies, and universities that has led to distrust in reporting systems and impeded meaningful change by allowing archaeology’s culture of toughness to prosper. A potential avenue toward increasing wages, benefits, work standards, and faith in reporting structures is unionizing. A common refrain in the open responses was a lack of oversight, with one person noting: “We need to work more closely with people interested in unionization, government regulators, and policymakers, because archaeological organizations will do nothing to improve conditions without being forced.”

Indeed, unionization in archaeology has been discussed and been variably successful since the 1970s (Bryan et al. Reference Bryan, Foreman, Phillips, Watson, Cobb and Hawkins2025; Corwin and Helmer Reference Corwin and Helmer2024; MacDonald and Kolhatkar Reference MacDonald and Kolhatkar2021; Press Reference Press2024). Unionizing would allow archaeologists—particularly those at the field-technician level—to demand and receive better wages and working conditions, including increased oversight related to harassment and injuries.

As noted above, research indicates sexual harassment and assault are more likely to occur in field situations without clear guidelines on appropriate behavior (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Nelson et al. Reference Nelson, Rutherford, Hinde and Clancy2017), and our results indicate archaeologists are rarely briefed on these topics. This disparity indicates there is a gap between our knowledge of the issues and the application of solutions in fieldwork contexts. The mismatch between archaeological training at universities and the work itself has been well-documented (for a review, see Morgan Reference Morgan2023), and this research presents another opportunity to expand pedagogy toward rectifying discrimination and harassment in archaeology. One respondent suggested field schools as a place for effective early socialization intervention, recommending that “educating students (especially in field schools) re appropriate behavior will lead to them expecting/demanding better working conditions.” All archaeologists should learn how to create protocols for reporting assault, harassment, and discrimination and ensure that those protocols are effective (e.g., Davis et al. Reference Davis, Meehan, Klehm, Kurnick and Cameron2021). Archaeological pedagogy should also include appropriate and inclusive practices, and highlight the data on sexual assault, harassment, bullying, and discrimination as laid out in this and other articles. For incoming archaeologists, it is paramount to be explicit about appropriate behavior and inclusive practices, rather than relying on the informality of the field to bring attention to these issues.

CRM firms, universities, and other agencies should formalize expectations related to behavior, conduct, and workload. In CRM field settings, early-career archaeologists are often thrown into projects at the last minute, leaving little time for formal training or introduction to appropriate norms of the field. As one respondent put it, “a lack of continual training” is a problem in archaeology, and formal and informal expectation-setting should be foregrounded as a means of course-correcting the culture of toughness in fieldwork toward a more inclusive, safer one. Rather than asking new archaeologists to learn the unspoken, harmful current culture, thoughtful policies and organizational structures with these issues in mind can reorient field archaeology toward safer and more professional practice. Relatedly, several respondents indicated frustration at the lack of open dialogue with leadership and indicated that good leaders contributed to positive experiences. One respondent noted that “feeling respected and appreciated by senior colleagues” encouraged them to continue in the field.

Many respondents also expressed the need to communicate work expectations with field staff as a means of reality-checking management expectations, with numerous respondents calling for realistic and manageable labor goals to be explicitly communicated and adjusted as needed. Expectation-setting should include explicit discussion of physical expectations: length of field session/day, number of shovel tests, distance/acreage, and break times. During these expectation-setting meetings field leaders should make space for crew members to express the expectations they feel they cannot meet and collaborate on ways to complete the necessary work or other more suitable job assignments. Allowing open conversation about potential discrepancies in expectations can prevent subtle discrimination caused by archaeology’s current culture, which celebrates overexertion and risk-taking. This can be a starting point for new archaeologists to explore avenues within archaeology aligned with their skillsets, interests, and abilities, rather than being a place to remove people from the discipline.

Individual Improvements

While systemic solutions were primarily selected for ways to improve the field, respondents overwhelmingly cited good people and leadership as contributors to positive experiences. Despite the myriad valid critiques of mentorship in scholarship on this topic (for discussion, see Fladd et al. Reference Fladd, Kurnick, Heath-Stout, Williams, Simeonoff, Bishop and Maclellan2026), respondents had a strong desire for this type of repair. Taking the lead of respondents, increased mentorship is proposed as a foundational step toward a more equitable discipline through relationship-building. As one respondent aptly stated, we need more “collaborative teams that are open to learning from each other.” Our data demonstrate that entry-level archaeologists, particularly women and noncisgendered individuals, are the most vulnerable to negative field experiences, and that all archaeologists experience pressure to perform for career success. The SCA Mentorship survey noted that archaeologists with same-gender mentors have more fulfilling mentorship relationships (Brown Reference Brown2018), and the same is true for mentor/mentee relationships with shared racial/ethnic backgrounds (Blake‐Beard et al. Reference Blake‐Beard, Bayne, Crosby and Muller2011). Therefore, all archaeologists—men, women, noncisgendered, minority-status, disabled, nondisabled—are called upon to take the initiative as mentors and role models to improve the field. Archaeologists who wish to change the negative impacts of performative informality in archaeology should increase their efforts to mentor, particularly male archaeologists who, these data show, are more insulated than their female and noncisgendered peers against sexual assault and harassment and other negative experiences in archaeology.

While formal mentorship networks exist in archaeology through institutions and usefully tap into organizational structures, informal mentorship can also be useful. Providing mentorship and ensuring all archaeologists see themselves in a mentor is the responsibility of those in higher positions who wish to change the current status of the field. This recommendation is aligned with several previous studies that suggest a lack of mentorship contributes to gender and role inequity (Brown Reference Brown2018; Fladd et al. Reference Fladd, Kurnick, Heath-Stout, Williams, Simeonoff, Bishop and Maclellan2026; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024; Heath-Stout and Hannigan Reference Heath-Stout and Hannigan2020; VanDerwarker et al. Reference VanDerwarker, Brown, Gonzalez and Radde2018; Whittlesey Reference Whittlesey and Claassen1994).

Aside from mentorship, another mechanism of personal action to mitigate these negative experiences is to set expectations for behavior periodically through microinterventions (Sue and Spanierman Reference Sue and Spanierman2020). Like microaggressions, microinterventions are interpersonal exchanges between individuals that, instead of causing harm, aim to highlight and subvert microaggressions (e.g., inappropriate behaviors, harassment, or pressure to overexert yourself). When applied to archaeology in particular, Heath-Stout notes that using microinterventions to highlight these behaviors can “demonstrate to perpetrators and bystanders that microaggressions are not acceptable behavior, and interrupt the rhetorical processes through which marginalized people are positioned as outsiders” (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2024:65). As a respondent put it, “Have conversations about these realities of discrimination and call people out.” While recognizing that no individual should have the burden of educating about and correcting these behaviors, microinterventions are a means of supporting each other during fieldwork and an avenue for personal change. Creating the expectation that field leaders call out and correct negative behaviors and making space for others to do the same will facilitate a safer and more positive working environment for all archaeologists.

Conclusion: “Inclusive Practices and a Commitment to Fostering Both Safety and Learning”

The data from this survey show that the culture of toughness in field archaeology includes the persistent attitude that archaeological fieldwork is an occupation where archaeologists should expect physical, mental, and emotional injuries. This attitude shapes archaeology’s specific type of performative informality, which must be correctly enacted to succeed. This emphasis has led to a high proportion of discrimination in the discipline, particularly for nonmale archaeologists and those in entry-level positions. Many of these rules and social conditions are created and maintained inconspicuously, resulting not exclusively (or even majorly) from outright malice or a desire to alienate women and noncisgendered people from the field but instead are the result of decades of internalized norms. Not only do these unspoken rules have a negative impact on success and career continuation, they also subtly transmit to those unwilling or unable to embody the correct type of performative informality that they do not belong. The message is that if you can’t dig all day, you don’t belong; if you can’t survey 15 miles at a breakneck pace, you don’t belong. This messaging is made possible, in part, by a culture of toughness in archaeology that insists “the real archaeologist is the cowboy who digs” (Beaudry and White Reference Beaudry, White and Claassen1994:139), and that the field is where this real archaeology happens. This notion is untrue and marginalizing to a large proportion of archaeologists, both in the field and out.

There is an overlap in data from this survey and previous surveys, specifically as it reaffirms that women, noncisgendered, and entry-level archaeologists experience archaeology differently from male and higher-level archaeologists. This is particularly troubling, given it has been over 11 years since the Southeastern Archaeological Conference survey first investigated issues of sexual assault and harassment in archaeology (Meyers et al. Reference Meyers, Boudreaux, Carmody, Dekle, Horton and Wright2015), and the scale of the problem is demonstrably international, as elucidated by this and other surveys (Bradford and Crema Reference Bradford and Crema2022; Coltofean-Arizancu et al. Reference Coltofean-Arizancu, Gaydarska, Plutniak, Laura, Hlad, Algrain and Pasquini2023; Hodgetts et al. Reference Hodgetts, Supernant, Lyons and Welch2020; Markert et al. Reference Markert, Hodgetts, Cantin, Gauthier, Lyons, Supernant, Welch, Wiley and Dent2025). Archaeology as a discipline has a duty to reflect on, analyze, and, when possible, provide solutions to inequities within the field. As our discipline continues to reckon with its unwelcoming and colonial past, this article offers potential solutions to create and foster environments that welcome diverse archaeologists to broaden perspectives on the past. We want to end this article with a quotation from a respondent who left the discipline, one that we believe encapsulates the multilayered issues in archaeology and, we hope, serves as a call to reflect:

I tried for years to find a way to exist in a system that ultimately seems that it was not built for me. To be successful, I needed to be white. To be paid more, I needed to be a man. To have upward career mobility, I needed to have a good financial background that would allow me to get a master’s degree. To be safe in fieldwork, I needed to have money to purchase and maintain the right gear, outdoor clothing, footwear, and hi-vis (all of which is often designed for taller, larger bodies and unsafe for other body types). Who set these barriers, and who perpetuates them?

Acknowledgments

This article was inspired by our collective experiences in and conversations about archaeology. It is only through strong mentorships, friendships, and especially the trailblazing archaeologists before us that we are able to contribute to an entire published series about issues of equity. We would like to thank Sarah Kurnick and Samantha Fladd for inviting us to participate in this themed issue. We would also like to thank Dulce Aldama, Casey Campetti, Kathryn Goldfarb, Sarah Herr, Greta Mateu, and Allison Mickel for thoughtful comments and advice about the project. This work would not be possible without the pioneering and vulnerable work of previous surveys, and we want to thank the researchers who inspired us to investigate these issues: Isabelle Algrain, Edmond A. Boudreaux, Danielle J. Bradford, Kaitlin M. Brown, Marie-Pier Cantin, Laura Coltofean-Arizancu, Stephen B. Carmody, Enrico R. Crema, Victoria G. Dekle, Joshua Dent, Solène Mallet Gauthier, Bisserka Gaydarska, Toni Gonzalez, Marta Hlad, Laura Heath-Stout, Lisa Hodgetts, Elizabeth T. Horton, Natasha Lyons, Patricia G. Markert, Laura Mary, Maureen Meyers, Polona Janežič, Béline Pasquini, Sébastien Plutniak, Hugh Radde, Amanda Sengeløv, Elisavet Stamataki, Kisha Supernant, Amber M. VanDerwarker, Ségolène Vandevelde, Barbara Voss, John R. Welch, Adrianna Wiley, Barbora Wouters, and Alice P. Wright. Most importantly, we extend huge thanks to all 566 survey respondents who took time out of their lives to answer these questions, some of which no doubt triggered memories about past experiences. We further thank all of the archaeologists who approached us to discuss these issues, offer their opinions and experiences, and encouraged us that writing this article matters. Finally, we warmly thank the four anonymous reviewers who provided valuable insight and critique that inspired future research. This research was conducted under the University of Colorado Boulder Institutional Review Board Exempt Protocol #24-0818, confirmed on January 7, 2025.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant funding from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability Statement

The survey data used for this article are restricted to protect the anonymity of project participants in accordance with the project’s IRB protocol issued by the University of Colorado Boulder.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.