Historians have long connected the rise of the capitalist world order to the emergence of the Caribbean plantation complex.Footnote 1 From the mid-seventeenth century onwards, ever increasing numbers of enslaved Africans toiled on American sugar plantations. European merchants sold the fruit of their labour to the growing middling sorts back home, who liked to add it to their tea and coffee, in turn imported from Asia.Footnote 2 The growth of slavery in the Caribbean was mirrored by an expansion of serfdom in Eastern Europe. Here, feudal lords forced peasants to produce textiles for export into the Atlantic.Footnote 3 By the early eighteenth century, serf-produced linens had become the main product European merchants exchanged for captives on the West African coast.Footnote 4 Perhaps surprisingly, the expansion of forced labour regimes in East and West was accompanied by growing efforts to liberalize the trade that connected them. Against the backdrop of protectionist mercantilist policies, European merchants lobbied for the relaxation and abolition of trade restrictions and customs duties.Footnote 5 Their efforts resulted in a growing number of ‘free ports’. Free ports thus stood at the heart of early modern globalization, and as such they constitute an important topic of global history.

Scholars like Corey Tazzara, Koen Stapelbroek, Grant Kleiser, and Pernille Røge have studied free ports’ intellectual and political history, tracing ideas and political debates on the merits and demerits of free trade and protectionism from the Enlightenment to the nineteenth century.Footnote 6 At the same time, they have paid little attention to free ports’ economic function. Given (free) ports’ unparalleled importance to the global economy, both past and present, such an investigation, however, seems warranted. Building upon research on the economic history of Atlantic trade, as well as the new history of free ports, this article for the first time offers an economic explanation for the spread of early modern free ports.

My argument is twofold: first, I present quantitative data demonstrating that the spread of free ports during the early modern period closely coincided with Atlantic trade expansion from c.1650; second, I show that free ports’ geographical focus began to shift at the same time. While early free ports clustered around the Mediterranean, from 1650, new free ports are found overwhelmingly on the Atlantic. They thus shadowed the shift of Europe’s centre of economic gravity from the south to the north-west which Atlantic trade expansion ushered in. I then conduct a qualitative analysis of the debate surrounding the proposed introduction of a free port at Hamburg during the 1750s. Hamburg is an interesting case: not only did it constitute the main trading hub connecting Central and Eastern Europe to the Atlantic; as a city-republic, its government comprised representatives of different interest groups, whose views are clearly articulated in the sources. The Hamburg records show that arguments in favour of a free port all centred on the importance of Atlantic trade to that city. While further research on the economic history of free ports is needed, my findings suggest that the correlation between the spread of free ports and the unprecedented expansion of the Atlantic trade from the 1650s was not a mere coincidence. Rather, they indicate the likelihood of a causal relationship: European polities considered free ports a tool that enabled them to better benefit from the economic opportunities Atlantic trade expansion offered. I argue that princes and magistrates opened individual ports to foreign merchants and reduced duties in order to attract more commerce, support new industries based on colonial goods, as well as create jobs for the local population. The remainder of this article is structured as follows. The first section provides an overview of the literature on free ports and Atlantic trade expansion respectively, and presents the quantitative data. The second section discusses the historiography on Hamburg’s economic history and the town’s place within the genealogy of free ports, as well as the sources for the qualitative part of the study. Two analytical sections follow, which draw out the arguments for and against a free port in the Hamburg debate. A final section concludes that, while local circumstances mattered to the debates taking place in Hamburg, to fully understand early modern free ports, we need to also consider global economic developments.

Atlantic trade expansion and the spread of free ports

Before the Industrial Revolution brought steam power and factory production, long-distance trade constituted the main driver of economic growth.Footnote 7 Over the course of the early modern period, economies in different parts of the globe grew increasingly connected, as well as dependent on maritime supply routes. Competition within the European state system led governments to favour economic policies of exclusion, often summed up under the term ‘mercantilism’, which aimed at reserving the profitable colonial trades for their own subjects, whilst excluding foreigners. Against this backdrop of protectionist economic policies, attempts to selectively liberalize trade gained traction. One approach to doing this were free ports.Footnote 8

Approaches to understanding early modern free ports have led to two historiographies. The first one, beginning with Fernand Braudel’s seminal study La Méditerranée in 1949, was developed further by Immanuel Wallerstein and followers of World Systems Theory.Footnote 9 This literature regarded free ports as a means by which Northern European states subjugated and exploited the Mediterranean. The second, more recent strand of literature rejects the notion of free ports as instruments of informal imperialism. In his seminal study of Livorno, the first free port, Corey Tazzara found that this port’s ‘meteoric rise was connected to that of the Atlantic economies’.Footnote 10 By first accepting, then supporting trade liberalizations at Livorno, the Medicis’ aim was to ‘facilitate commerce between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean’.Footnote 11 Tazzara argued that the further spread of free ports in the Mediterranean constituted ‘an adaptive response to changing patterns of long-distance trade and commercial competition among the small states of north-central Italy’.Footnote 12 However, as he emphasized, this was not a symptom of encroaching northern imperialism. Contrary to Braudel’s and Wallerstein’s reading, Tazzara argued that northern European economies did not come to dominate the Mediterranean. Instead, regional economic ties remained more important to Livorno, and trade liberalizations in the region over the following century reflected local agency as well as political and economic competition.Footnote 13 Historians since have followed Tazzara’s example and emphasized the distinctness of individual free ports and the importance of unique local or regional circumstances in their creation.Footnote 14 They have identified three motives for the introduction of early modern free ports.

Early free ports were often established in order to secure food supply to struggling regions. For example, the series of commercial policies the Medici introduced in Livorno from the 1590s onwards aimed to attract grain shipments to the famine-struck region.Footnote 15 A second motive emerged from colonial expansion to the Americas during the seventeenth century. Historians have frequently pointed to the ubiquity of smuggling in the Atlantic.Footnote 16 Seated at desks in London, Paris, and Amsterdam, mercantilist bureaucrats devised protectionist trade policies in order to prevent the enemy from sharing in the gains from trade with one’s colonies. However, enforcement of these policies proved difficult. Imperial governments who wished to steer colonial trade flows found that the protectionist barriers they erected failed to withstand the force with which markets expanded. Opening a port to free trade constituted one response to this. By conceding their inability to control economic borders, colonial governments hoped to benefit from trade at least indirectly.Footnote 17 Moreover, they hoped that by selectively opening individual colonial ports to all, they might outcompete and thereby economically weaken rival powers.Footnote 18

A final motive for free ports arose from the desire to ensure the continuation of trade in times of war. As the importance of the Atlantic trade to European economies grew, governments tried to control maritime trade routes.Footnote 19 By the eighteenth century, Europeans routinely went to war over trade. The great powers battled each other at sea, and belligerent navies and privateers targeted enemy merchants. To ensure that trade could continue despite ongoing conflict, European governments began implementing policies of maritime neutrality. During the mid-eighteenth century, a cluster of Scandinavian, French, British, and even Spanish ports were declared ‘free’, serving, in Leos Müller’s words, to ‘neutralize’ wares.Footnote 20 This allowed trade to continue despite ongoing conflict. Especially for France, Leos Müller argued that ‘trade under neutral flags became essential’.Footnote 21 As during free ports’ earlier spread in the Mediterranean, Grant Kleiser and Pernille Røge have shown that free ports in the Caribbean evolved in concert with each other, as European colonial powers paid close attention to their rivals’ policies and were keen ‘to borrow their methods to achieve similar results’. At the same time, Kleiser and Røge emphasized that ‘emulation was not replication’: Colonial powers’ incentives and aims for introducing free ports differed greatly from case to case. The literature thus maintains that motives for the introduction of free ports were highly localized and rooted in each port’s particular circumstances.Footnote 22 This article challenges this view: it argues that to fully understand the spread of free ports, we need to take their global economic context into consideration.

The new historiography has greatly improved our understanding of early modern free ports, especially by moving them out of the shadow of World Systems Theory. At the same time, its focus on political and intellectual developments has led to a neglect of economic aspects. These, however, are important: ports were and are economic institutions, which governments built and maintained primarily, if not exclusively, to facilitate trade. Economic historians working on the Atlantic, meanwhile, have so far not taken note of the new research on free ports. This article brings the two literatures into conversation with each other. While recognizing the political autonomy of sovereign states who introduced free ports which the recent historiography has emphasized, this article suggests that governments’ decisions to liberalize individual ports still constituted a response to global economic change.

The early modern period’s most important economic development was an unprecedented expansion of the Atlantic trade from c. 1650. An extensive literature testifies to the immense economic importance of the Atlantic trade, crediting it with facilitating the onset of sustained economic growth in Europe and thus constituting the root cause of present-day global inequality.Footnote 23 The literature on free ports has contextualized some of these within the context of European colonialism. However, while colonialism and trade were closely related phenomena, they were not synonymous and neither suffices to explain the other.Footnote 24 A glance at their respective timelines reveals that a distinction between the political history of colonialism and the economic history of trade may improve our understanding of free ports significantly. European colonialism in the Atlantic spans the entire early modern period and beyond. In contrast, economic historians have identified the mid-seventeenth century as a watershed in the region’s commercial development. This was driven by the sugar revolution. In 1630, the Dutch conquered the Brazilian province of Pernambuco from Portugal, and colonists began growing sugar there. Portugal’s reconquest of Pernambuco in 1654 sent colonial planters scattering across the Caribbean. They brought their technology and organizational skills with them – as well as their practice of relying on enslaved African labour, rather than indentured Europeans. The following decades witnessed the emergence of the ‘plantation complex’, the mass production of agricultural products through the combination of American land, African labour, and European capital.Footnote 25 Economic historians believe that the dramatic growth of trade in the Atlantic that followed this innovation transformed European economies and constituted the root cause of sustained economic growth in those European states that were situated on the Atlantic rim (see Figure 1).Footnote 26 Recently, Ulrich Pfister has shown that Atlantic trade expansion had the same effect on parts of Central Europe, including Hamburg.Footnote 27 At the same time, as Anka Steffen argued, it drove the expansion of bonded labour in Eastern Europe, where local serfs were forced into producing textiles for the Atlantic trade, likely retarding this region’s economic development.Footnote 28 The mid-seventeenth century thus constituted a pivotal moment in the development of the Atlantic trade, as well as global economic history.Footnote 29

Figure 1. Caribbean free ports, 1500–1800

Sources: Figures 1 and 2 are based mostly on Corey Tazzara’s (2014) list of free ports. For ports not included in Tazzara, see: Tortola: Mulich, ‘Microregionalism’; Hamburg, Amsterdam, Bremen: Pfister, ‘Great Divergence’; Lucea (Jamaica) 1766: Hunt, ‘Contraband; Barthelemy 1785: Han and Wilson, ‘Eighteenth-Century’; St Eustacius 1663: Kleiser, ‘Emulating Empires’. For full references see footnotes throughout. Copyright with the author.

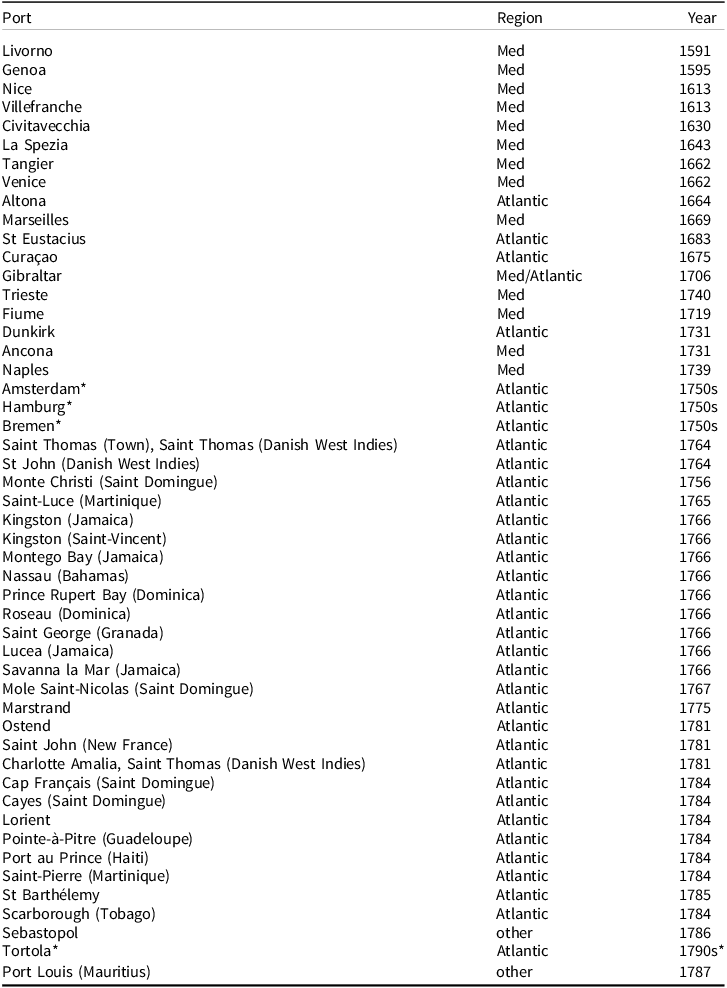

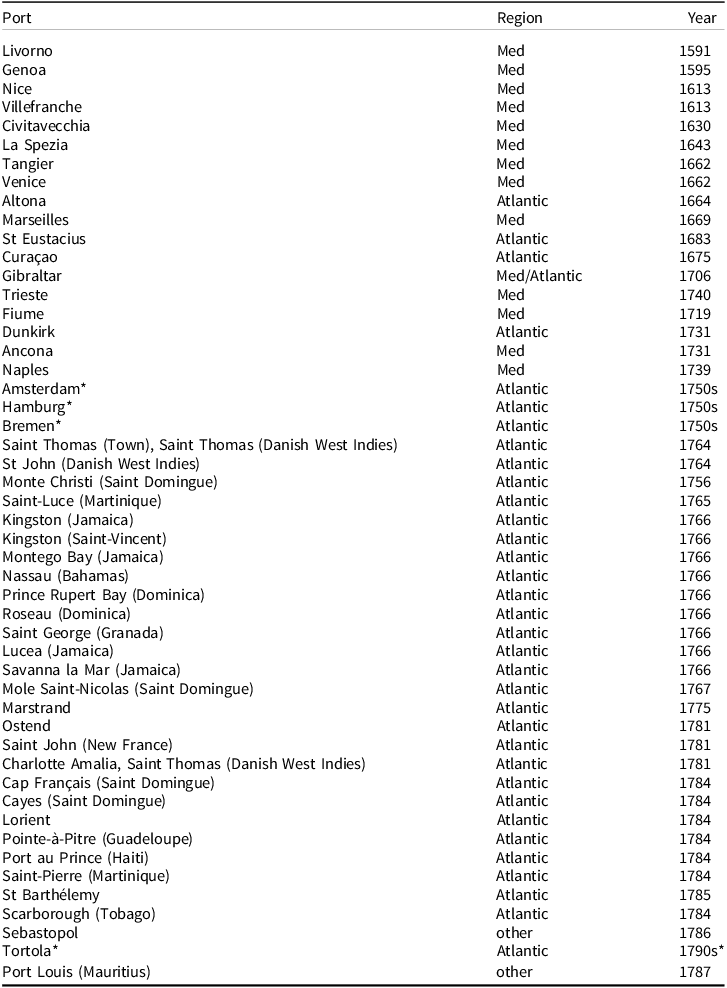

In order to explore the relationship between Atlantic trade expansion and free ports, I surveyed the secondary literature in five different languages and compiled a list of free ports.Footnote 30 I found a total of forty-six free ports for the early modern period, plus a further four ports that debated liberalization but did not implement it. A closer look at the dates of their liberalization reveals a close correlation between the growth of free ports and trade in the Atlantic. Between 1590 and 1650, European rulers founded only six free ports: Livorno, Genoa, Nice, Villefranche, Civitavecchia, and La Spezia. All of these were located on the Mediterranean. A significant change can be observed during the mid-seventeenth century: the total number of free ports increased dramatically, as shown in Table 1. Between 1650 and 1800, forty ports were declared ‘free’.Footnote 31

Table 1. The establishment of free ports, 1591–1800

*Ports marked with an asterisk debated becoming a free port but did not proceed before 1800. I include North Sea Ports in the category ‘Atlantic’ as the North Sea formed the gateway to the Atlantic.

Sources: see text.

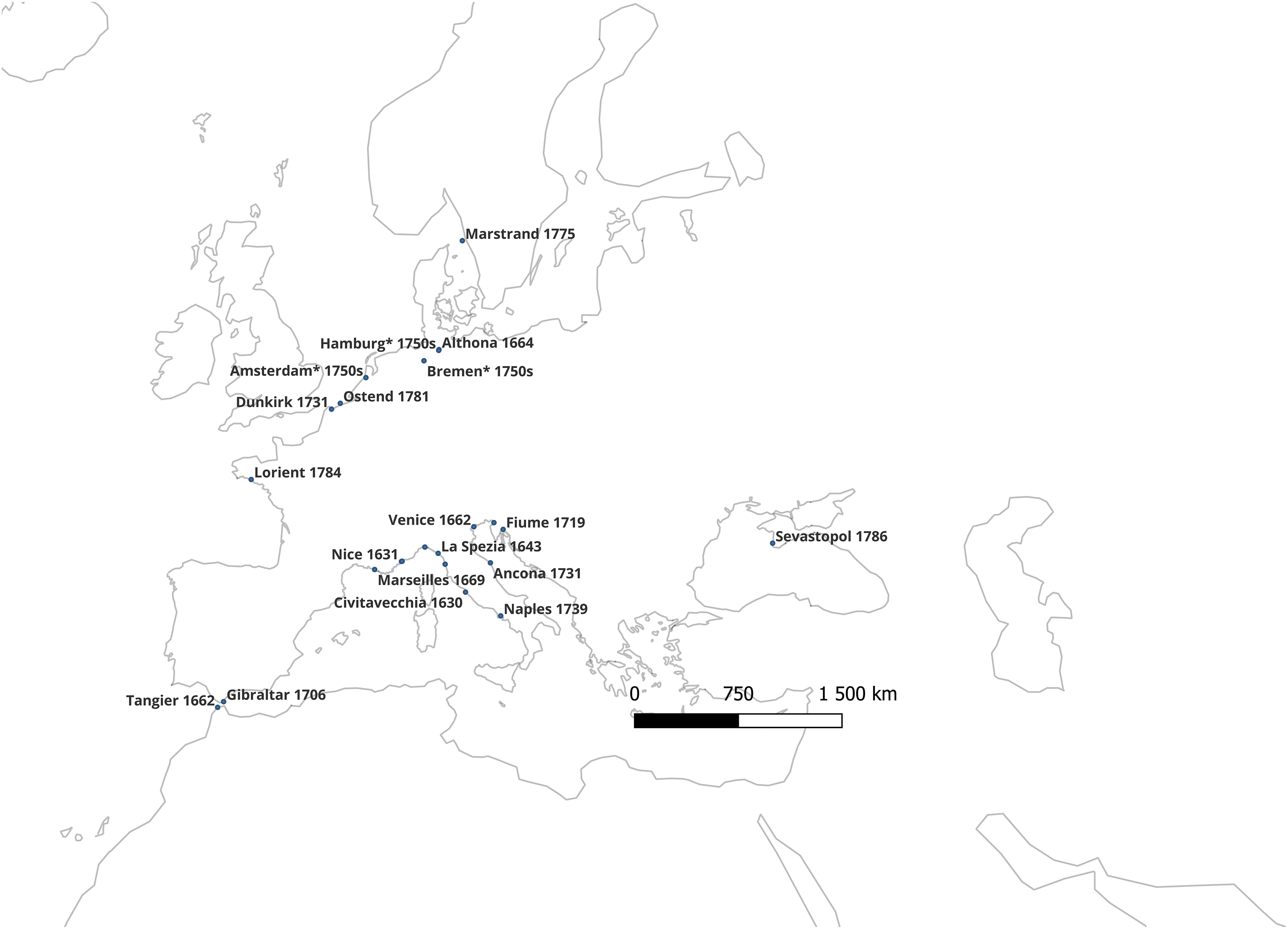

Along with their numerical increase, free ports’ geographic focus changed. Plotting free ports on a map shows that all those founded prior to 1650 were located on the Mediterranean (see Figure 2). Of the forty free ports founded after 1650, a staggering thirty-one (75 per cent) were situated on the Atlantic. What is more, Hamburg and Amsterdam were two of an additional four ports located either on the Atlantic or functioning primarily as entrepôts for Atlantic goods that deliberated becoming ‘free’ but did not proceed during the 1750s (Bremen, Amsterdam, and Hamburg) or the 1790s (Tortola). Of the remaining free ports, eight (20 per cent) were on the Mediterranean, one was in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius), and one in the Black Sea (Sevastopol).

Figure 2. European free ports, 1500–1800

Note: Ports marked with an * debated becoming a free port, but decided against it.

The data suggests a pattern: free ports followed commercial development. Until the early seventeenth century, the Mediterranean constituted Europe’s most important economic theatre. Over the course of the seventeenth century, this situation changed: trade in the Atlantic increased while that in the Mediterranean stagnated. Europe’s centre of economic gravity shifted from the south to the north-west. Free ports followed this move. Of course, correlation does not equal causation. However, given that free ports’ primary purpose was the facilitation of trade, it seems likely that their evolution and the growth of the Atlantic trade, as the period’s most important commercial development, were indeed connected. Accordingly, this article suggests that the two were causally related: governments adopted and adapted the free port model in order to benefit from the new economic opportunities the growing Atlantic trade promised.

Hamburg

During the early modern period, the term ‘free port’ referred to a bundle of liberal trade policies implemented in a certain port. As Tazzara and others have shown, rather than a comprehensive political ideology, the policies the Medici introduced in Livorno constituted codifications of pre-existing practices, which had evolved over time and proven useful.Footnote 32 Free ports thus constituted early experiments in liberal trade policies, with conditions varying greatly between locations and over time.Footnote 33 ‘Free’, as Grant Kleiser recently put it, meant ‘commerce that extended beyond national and imperial borders’.Footnote 34 The essence was not a complete absence of duties on goods, as modern usage of the term might suggest, but trading conditions that were simply more favourable than what merchants would find elsewhere.Footnote 35 The brothers Savary’s Dictionnaire Universel de Commerce of 1723 first defined the ideal form of a free port, as contemporaries thought of it then: free ports were places where merchants could trade on equal terms, irrespective of place of origin or religion, with low or few duties on storage or transit.Footnote 36

This changed with the opening of Hamburg’s free port in 1888. At that moment, free ports became tangible. City authorities cut off a slice of Hamburg’s harbour and designated it ‘free’. Henceforth, this piece of Hamburg would exist outside the customs zone, beyond the economic border of the German Zollverein, which Hamburg had joined a few years earlier. The new free port area constituted ‘an exclusively commercial space’, home to large warehouses and other commercial infrastructure, but without inhabitants.Footnote 37 According to Dara Orenstein, Hamburg’s innovative free port ‘dazzled visitors’.Footnote 38 It was quickly replicated by foreign policymakers and served as a model for modern free ports across Europe and the United States. What was more, it constitutes the ancestor of foreign trading zones, of which over 3,500 are spread across the globe today. As such, Hamburg played an important part in the genesis of modern free trade policy instruments.Footnote 39

Despite its apparent importance within the family tree of free trade institutions, the new history of free ports has largely ignored Hamburg.Footnote 40 Instead, the city on the Elbe is best known for the commercial importance it achieved as one of the leading towns in the Medieval Hanseatic League, connecting trade in the Baltic and North Seas. During the early modern period, most Hanseatic ports declined, but Hamburg continued to flourish.Footnote 41 Economic historians have explained Hamburg’s continued commercial importance with reference to its ability to forge ties to the growing Atlantic economies.Footnote 42 As a city-republic without colonies of its own, Hamburg was excluded from intercontinental trade.Footnote 43 However, beginning in the seventeenth century, it found a way of working around this predicament: it introduced policies with the specific goal of encouraging merchants to build commercial relationships with the American colonies. This is when we first find traces of free trade ideas in Hamburg’s sources: the city emulated elements of Livorno’s free port model by inviting minoritized and persecuted Atlantic merchants to settle and trade from the city, especially Sephardic Jews and French Huguenots.Footnote 44 Furthermore, Hamburg merchants settled in British, French, Spanish, and Portuguese ports in order to trade with these countries’ colonies.Footnote 45 They bought primary products from the Americas, especially sugar, tobacco, indigo, and coffee, and shipped these to their home town. France and England were Hamburg’s two most important partners in overseas trade, accounting for 80 per cent and more of all recorded imports up to c. 1790. As Ulrich Pfister put it, during the eighteenth century, Hamburg ‘functioned as the downstream end of France’s merchant empire for Central Europe’.Footnote 46 Hamburg merchants re-exported these colonial goods all over Central and Eastern Europe, as far as Austria, Bohemia, Hungary, and eastern Poland.Footnote 47 In return, as Klaus Weber and Margit Schulte-Beerbühl showed, they channelled especially Central and Eastern European textiles to the same European Atlantic ports, from where they found their way to Africa and the Americas.Footnote 48

By the 1750s, commercial ties to the Atlantic had come to dominate the city-republic’s economy, and colonial imports made up roughly half of Hamburg’s overall import values.Footnote 49 The city’s inner economy also changed. Hamburg emerged as one of Europe’s leading centres for sugar refining, counting about 350 sugar boiling houses in 1750.Footnote 50 Calico printing and tobacco processing were also important industries.Footnote 51 Clearly, its commercial relationships to the Atlantic played an important role for Hamburg’s economy. Thus, despite a lack of direct involvement in New World colonialism, Hamburg emerged as a major entrepôt for colonial goods sold to the European hinterland, as well as linens destined for the Atlantic.

Politically, too, Hamburg constitutes a useful example for the study of free ports: it differed from the free ports the literature has focused on so far, in that it was not a monarchy, but a small city-republic. While formally part of the Holy Roman Empire, legislative and executive power rested with the Council and Assembly, the Rat and Bürgerschaft. Furthermore, a formal body representing the merchant community, the Commerzdeputation, while not formally part of the government, was in constant conversation with the Council and wielded substantial influence.Footnote 52 Debates at government level therefore immediately reflect the interest of different stakeholder groups in the city. The merchants’ perspective, especially, emerges with greater clarity than in locations with less popular representation in government. While proponents of a free port did not prevail at this point, the Hamburg debate sheds light on how global economic forces and local economic, political, and social interests conspired to shape trade policies at a time when Central Europe became irrevocably entangled in the global economy. If Atlantic trade expansion drove the proliferation of free ports, we would expect Hamburg’s records to reflect this.

The main proponent of a free port in Hamburg was the Commerzdeputation. During the 1750s, it petitioned the Council for a free port at least eleven times. The merchants had reason to expect sympathy from the Council: of its twenty-four members, thirteen were merchants, whilst the other eleven were lawyers. Election to all posts was by co-option, provided that the candidate was Lutheran and over thirty years of age.Footnote 53 The Council’s powers included foreign policy, the dispensation of justice, and numerous other aspects of domestic administration. In most areas the Council’s power was administered in mixed disputations consisting of senators and citizens elected by the Bürgerschaft. Importantly for Hamburg’s free trade debate, the Council could not change or make new laws, or levy taxes, without the Bürgerschaft’s consent.Footnote 54 Unlike the Council, the Bürgerschaft primarily represented the interests of Hamburg’s guilds, artisans, and craftsmen who did not usually make their living from trade. As the new processing industries of sugar, tobacco, and coffee were not organized in guilds, their interests were not represented in the Bürgerschaft. Admission to the Bürgerschaft was based on freeholder property in the city.Footnote 55 The Bürgerschaft met biannually, at the Council’s request. At these meetings, it passed important legislation affecting the interpretation of the constitution. Importantly, its remit also included all matters relating to taxation, tolls, and customs.Footnote 56

During the eighteenth century, Hamburg’s main tolls were the admiralty and convoy tolls, levied to fund convoys for the protection of Hamburg’s merchant fleet from Mediterranean piracy. However, not all imports were subject to the admiralty and convoy tolls. Toll-free goods included all maritime imports from the northern Netherlands, the neighbouring German sea ports, the Baltic and Scandinavia, all river and overland trade, and all imports of goods for the use of citizens themselves, as well as coal and grain.Footnote 57 Liberalization of the port’s tolls began early in the eighteenth century. In 1713, the Council cut tolls on the transit of wares through the city and on goods that would be stored in Hamburg for up to six months. In 1727 it declared the city a porto transito, which meant tolls on exported goods were limited to a few areas of trade, notably grain. In 1748 tolls on grain exports were also abolished.Footnote 58 In 1751, when our analysis sets in, the city still levied tolls on all imports from France, Britain, Spain, Portugal, and the Mediterranean. The sources reveal that the inclusion of agricultural products from these countries’ colonies such as raw sugar, coffee, and cotton were a particular concern. In addition, exports of manufactures produced in the city continued to be subject to tolls.

One hundred years earlier, these toll reductions might have sufficed for contemporaries to consider Hamburg a free port. As the sources show, during the 1750s, it no longer did. Extensive records of the Council and the Commerzdeputation survive, while those of the Bürgerschaft do not. The Council and the Commerzdeputation’s records show Hamburg’s merchants and magistrates discussing the pros and cons of a free port for over 200 years. Ernst Baasch, perhaps the most prolific writer on Hamburg’s pre-modern economic history, noted that the free port debate entered a particularly heated phase during the 1750s.Footnote 59 Following his lead, I identified four sub-collections of sources related to the free port debate during this decade. Comprising almost 900 pages, the files include copies of the same documents and repeat the same arguments over and over, suggesting that they provide a comprehensive picture of the debate. Specifically, the documents viewed are first, the ‘Extracts of the Protocols of the Commerzdeputation, February 1751–September 1760’. This contains the minutes of sixty-two Commerzdeputation meetings during that time, spread relatively evenly across the decade. Second, the ‘Investigation whether the Hamburg tolls have an impact so detrimental to its commerce that they need to be abolished entirely’, from 1751, comprising eleven pages of anonymous authorship, parts of which appear identically in other records of the Council’s collection. Third, the ‘Recentiora regarding a free port’, a collection of around 600 pages, including copies of the Commerzdeptuation’s petitions to the Council, and extracts of minutes of Council meetings on these petitions. Fourth and finally, the ‘Toll-deliberations regarding the introduction of a free port, 1752–1756’, containing about fifty pages of commentary by Council member Z. Amsinck, explaining his views on a potential free port. Through these records, we can trace the ebb and flow of the free port debate.

The sources show that the debate over a free port rested upon two tropes: first, concerns over what contemporaries called the ‘jealousy of trade’ – that is, European states’ propensity to defend their commercial interests through military force;Footnote 60 and second, and perhaps even more importantly, participants considered contemporary ideas regarding both governments’ and individual citizens’ responsibility to contribute to the well-being of the polity as a whole. While both themes at first glance appear to reflect local and regional concerns, the sources show merchants and magistrates relating them explicitly to the Atlantic trade.

The Dutch threat and the competition for colonial imports

Hamburg’s free port debate during the 1750s was triggered by news arriving from Amsterdam, the city’s main commercial rival on the European continent.Footnote 61 First, in the summer of 1751, the Dutch Stadtholder William IV, commander-in-chief of the army and de facto head of state of the United Provinces, presented the States General with a ‘Proposal … for the reform and improvement of the trade of the republic’. This pamphlet lamented the decline of Dutch trade since its seventeenth-century heyday. It outlined a plan to recapture the Netherlands’ former commercial glory and regain its place among the world’s leading political powers. Its central point: the introduction of a free port at Amsterdam.Footnote 62 Plans for a free port in Amsterdam were halted when the Stadtholder unexpectedly died later that year. However, public debate on the benefits and drawbacks of a free port at Amsterdam continued. This led to the second piece of news to send Hamburg’s merchants into a frenzy: the Dutch abolition in 1754 of tolls on imported goods also prominently traded through Hamburg, namely wax, indigo, Russian leather, and jute.Footnote 63

Hamburg constituted Europe’s third-largest port after London and Amsterdam and vied with the latter for the role of primary gateway between Central Europe and the Atlantic, as both served as hubs for the import of colonial goods to Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe, and the export of continental European textiles into the Atlantic.Footnote 64 News from Amsterdam travelled quickly to Hamburg, and a copy of the Proposal is included among the Hamburg Council’s records of 1752. Footnote 65 The Hanseatic merchants perceived the plan of a free port at Amsterdam as a threat to their own business interests, as well as to Hamburg as a whole. Galvanized, they began petitioning the Council. The Commerzdeputation demanded the Council take measures to avert the pending disaster. They argued that it was to be expected that the Amsterdam free port would ‘overthrow’ Hamburg’s trade completely. Hamburg was in no position to compete with a Dutch free port, as its trade was already struggling due to the ‘manifold burdens’ the Council refused to lift.Footnote 66 The only way of avoiding ‘the Dutch robbing us of the major part of our trade’ was to immediately abolish tolls on trade in the same wares ‘for all nations’. The Commerzdeputation impressed upon the Council the urgent need to introduce a free port in Hamburg, too: ‘according to the majority of voices’, they warned, the introduction of an unlimited free port was ‘near unavoidable … lest the Dutch, once they executed their free port project, cause our trade a great disadvantage’.Footnote 67

Upon learning of the introduction of toll exemptions in Amsterdam in 1754, the Commerzdeputation again contacted the Council, informing it that the ‘latest post from Amsterdam contains reports that the introduction of a general free port there is imminent’.Footnote 68 They emphasized that the Dutch plan presented an immediate and grave threat to Hamburg, as ‘[c]ertainly, the foreign merchant will send his wares to places, and order them from places, that cost him least’. Merchants, always on the look-out for ways of saving costs, were bound to abandon Hamburg and move their business to Amsterdam. Even the smallest differences in transaction costs between ports would make merchants redirect their business, the Commerzdeputation argued.Footnote 69 A typical letter of the many the Commerzdeputation directed to the Council during this time read as follows:

For several years now, trade has increasingly abandoned our city, and our neighbouring towns, who are thriving, do so mostly thanks to trade that formerly went through Hamburg. And what other cause do foreigners have for abandoning us, than the tolls they have to pay here, but not elsewhere?Footnote 70

An abolition of tolls at Amsterdam would increase the relative cost of trading through Hamburg, which the latter’s trade would not survive. No loyalty could be expected from merchants presently trading through Hamburg, as even ‘German friends are writing that they will obtain wares from Holland with greater profit.’Footnote 71

The Commerzdeputation framed Dutch plans to liberalize trade as acts of political aggression directed purposefully at Hamburg. The merchants accused the Dutch Republic of deliberating a free port specifically out of ‘jealousy against Hamburg’s trade’.Footnote 72 Referring to the Proposal, they argued:

It has come to light now that the true aim of the free port is no other, than to benefit from the present depressed state of the economy to draw the Spanish trade, and with it the most considerable part of our trade, away from us and towards Amsterdam.Footnote 73

There was some base to this argument. The Proposal of 1751 did name Hamburg as one of the Netherlands’ main competitors, together with the much smaller ports of Ostend, Dunkirk, Bremen, Lübeck, and Altona.Footnote 74 Indeed, the Commerzdeputation pointed out that ‘when in 1752 trade between Hamburg and Spain was disrupted, Holland immediately concluded a treaty with Spain, which freed linen and various other import and exports to Spain from tolls’.Footnote 75 The letter did not mention how Hamburg had provided this opportunity, angering Spain by signing a treaty with Algiers to protect its ships from Barbary pirates. The treaty had included a secret passage in which Hamburg pledged to provide guns, powder, lead, and ship-building materials to the North African state. Spain learned of this promised aid to its enemy and cut Hamburg off.Footnote 76

The extent to which Hamburg’s merchants experienced losses due to the short disruption of trade with Spain is not clear. However, by the mid-1750s, they certainly struggled. War in the Atlantic, which raged in the years 1701–14, 1740–48, and 1756–63, had become increasingly impactful. Its political neutrality offered some protection to Hamburg ships, though many still fell victims to warring powers’ privateers. As the importance of the colonial trades for the city’s economy grew, so did Hamburg’s sensitivity to war in the Atlantic. The city’s reliance on French, British, and Spanish colonial imports meant that its trade and industries suffered from the disruption of those countries’ trade. The impact of the Seven Years War (1756–63) was the greatest. This saw Europe’s leading colonial powers battling each other around the globe, which severely disrupted maritime trade. Fighting in the Baltic disrupted trade flows to Prussian ports. As a consequence, one of the Commerzdeputation’s missives to the Council in July 1757 pointed out, ‘wares necessarily will have to be transited through either Hamburg or Altona in order to reach the Brandenburg lands’. They went on to say that unless Hamburg eliminated tolls on those goods, the Altonaers, who already enjoyed a free port, would be able to capture all trade in wine and spirits. ‘In view of the many advantages tied to [the Baltic trade], such as securing insurance, payment of bills of exchange, and employment for many people’, the letter warned, preventing them from underselling the Altona merchants by keeping tolls in place would be strategically unwise.Footnote 77 Hamburg imports dropped by about 20 per cent, and prices of colonial groceries in Hamburg exceeded peacetime levels by almost 40 per cent.Footnote 78 After the war, the city’s trade took an unusually long time to recover, compared with post-war periods earlier and later in the eighteenth century. Researchers have not been able to fully explain this, but lack of competitiveness with the new Dutch toll regime may have been one factor.Footnote 79

The merchants’ framing of the Dutch policy proposal as an act of aggression, founded in ‘jealousy’ and intended to harm Hamburg, hints at a key theme underlying the debate: the contemporary relationship between commercial competition and warfare. European states relied on monopolizing and taxing commerce in order to support their armies and navies. By excluding foreigners, European states hoped to secure revenue from trade for themselves. Their trade policies therefore aimed at generating income to fund military campaigns. At the same time, European powers employed military means to support their trade interests. Wars in support of commercial interests generated further need of funds, resulting in a vicious cycle of trade–war–trade.Footnote 80 Contemporaries across Europe referred to this political-economic relationship as ‘the jealousy of trade’.Footnote 81

Differences in economic power translated into hierarchical relations between states.Footnote 82 Their prominent role in trade allowed small republics like the United Provinces, and Hamburg to interact with greater empires like France and Britain on the global commercial stage. However, as a city-republic, Hamburg, far more than its peers Amsterdam and London, faced the threat of European rivals without the financial and military backing of a territorial ruler.Footnote 83 Indeed, one senator questioned whether Hamburg, ‘as the only city without any territory isn’t getting ahead of itself in pursuing commercial pretentions like some of the greatest nations in Europe?’Footnote 84

Hamburg’s position within the European state system rested entirely on its neutrality and favourable diplomatic relationships with the great powers. This constituted a delicate equilibrium, the maintenance of which was paramount to the city’s survival. Given the commonly understood connection between trade policies and war-finance, the senators warned that foreign powers might conceive the introduction of a free port in Hamburg as an act of political aggression – mirroring the merchants’ argument that the Dutch Proposal constituted just that. The senators argued that ‘most princes are watching our trade jealously and any new means of further encouraging the expansion of our commerce would only provoke them further’.Footnote 85

Hamburg especially struggled with aggression from neighbouring Denmark, who threatened Hamburg’s independence and its gateway function between inland and maritime trade. The Danish crown repeatedly used its superior military power to extort large sums from Hamburg.Footnote 86 It also weakened the Hamburg emporium by creating alternative seaports on the lower Elbe River and supporting the development of a commercial infrastructure there. Most important among these was Altona, which immediately bordered Hamburg and became an early free port in 1665. The Hamburg senators argued that Denmark had been forcing its subjects to purchase goods directly from the first port of origin, circumventing intermediary trades and thus putting traders out of business.Footnote 87

In the face of the Council’s staunch objections, in 1756 the Commerzdeputation suggested a limited free port as a compromise.Footnote 88 This would extend the transito of 1727 to abolish tolls on exports via the North Sea. Some senators acknowledged that this would help Hamburg’s trade, but warned that the geopolitical risks were still too great. They thought that ‘favouring certain powers and their countries over others would clearly cause the most dangerous consequences for the city … France is paying close attention to our tolls’, Senator Z. Amsinck explained in May 1756 in his ‘Recapitulation of the toll deliberations’ in which he summed up the discussion of the preceding years. If Hamburg were to abolish any further levies, France would immediately demand the lifting of duties on all goods arriving from French ports, he predicted.Footnote 89

Hamburg had concluded a commercial treaty with France in 1716. It provided the Hanseatic town with the most favoured status reserved until now for the Dutch, and protected its citizens’ freedom of movement and property rights in French seaports.Footnote 90 The treaty of 1716 thus granted Hamburg political neutrality and protected its commerce. Combined with the emergence of Hanseatic merchant communities in French seaports and a Huguenot community in Hamburg from the late seventeenth century, this treaty constituted a major institutional basis for Hamburg’s new commercial focus on sugar and coffee. Robert Stein estimated that during the eighteenth century, Hamburg received about four-fifths of its raw sugar from France.Footnote 91 By the 1730s, France was Hamburg’s principal trading partner.Footnote 92 Angering France might cause the more powerful partner to end the treaty, and thus the ‘loss of our entire neutral trade and shipping’.Footnote 93 The senators were right to be worried: with the onset of the Seven Years War in 1756, Hamburg’s relationship with France became increasingly strained and in 1760 the larger state did cancel the treaty.Footnote 94 While France remained Hamburg’s principal trading partner for more than two decades, Hamburg merchants in France now had to pay higher taxes and lost the preferential status they had long enjoyed. This sent the Commerzdeputation pushing for a new treaty, which was not concluded until 1769. It was similar to the treaty of 1716, except in the matter of several secret articles in which Hamburg granted French merchants far-reaching toll exceptions.Footnote 95

The senators emphasized that as a city-state, Hamburg found itself in a particularly precarious position vis-à-vis larger European powers’ aggressive commercial overbearance, even with commercial treaties in place. ‘Trading cities [such as Hamburg] hardly benefit from these [commercial treaties with foreign powers] as they are forced to follow them to the letter, while great powers interpret them as they wish and follow or ignore them as they please.’ The best way to avoid provoking the ‘jealousy of the great powers’ was to avoid ‘bragging about one’s own commerce to foreigners’ and hope that nobody would notice one’s success.Footnote 96 This reprimand hinted at Hamburg’s rivalry with Amsterdam, its main competitor for channelling Atlantic goods into continental Europe. Hamburg’s merchants were terrified that if the rival introduced a free port while Hamburg did not, this would tilt the scales significantly in Amsterdam’s favour. Hamburg would lose the benefits it enjoyed from its close ties to the Atlantic economies, followed by economic decline. In their petitions to the senate, Hamburg’s merchants framed the Dutch proposal as part of the contemporary ‘jealousy of trade’. Its threat to Hamburg’s economic interest was not an unfortunate by-product of the United Provinces’ economic policies, but an intentional provocation. When responding to the Commerzdeputation’s petitions, Hamburg’s Council also highlighted the threat the city faced given the ‘jealousy of trade’. However, the Council saw danger lurking in another corner: in their view, liberalizing Hamburg’s port might bring France onto the scene. France played an important role in supplying Hamburg with Atlantic goods. In the Council’s eyes, potential retaliations from France outweighed any threat Dutch competition might pose. Similarly, the Council saw a risk of attacks by Denmark, who had been threatening the city-republic both economically, through creating a number of free ports in Hamburg’s immediate vicinity, as well as militarily. As a small city-republic, Hamburg lacked the military means to support its economic interests vis-à-vis greater territorial states. Hence, it needed to find diplomatic means to ensure both its economic and political survival. While the merchants thought a free port would help with the former, the Council feared it would endanger the latter. In other words, in 1750s Hamburg both proponents and opponents to a free port saw the city’s commercial ties to the Atlantic at risk. They differed merely on their interpretation of how best to protect this relationship.

The question of social responsibility: Or, who foots the bill?

The Senators mostly agreed that trade was suffering. However, they objected to the free port as an appropriate remedy for Hamburg’s commercial crisis. Frequently, they pointed out that there had always been levies on trade in the past, and commerce had flourished anyway.Footnote 97 It was therefore not reasonable to blame the current crisis on tolls. Instead, the Council identified broader developments in European political economy as the root cause of Hamburg’s trouble. Specifically, Hamburg’s senators blamed other states’ protectionist policies. This period saw the ascent of Prussia and Russia as major powers, whose economic policies pivoted on controlling foreign trade and subsidizing local industries.Footnote 98 These developments presented a new and serious challenge to Hamburg’s commerce. According to the Council, foreign princes had lost their way: ‘In this century, monarchs in nearly all European states have been paying particular attention to increasing their own trade by building factories and banning the importation of foreign goods’, they argued.Footnote 99 No longer prioritizing the well-being of their citizens as a whole, they had begun to favour policies which enriched the few, while causing great harm to everyone else.

To illustrate their reasoning, the Council pointed to measures Russia had recently taken. In 1703, Peter the Great had founded St Petersburg. To increase trade, he invited merchants to settle there as well as ordered trade formerly transacted through Moscow to move to the new port.Footnote 100 They argued that the ‘building of St Petersburg and that government’s moving trade there’ made it more advantageous for many in Prussia, Bohemia, Hungary, and Austria, who formerly obtained goods from Hamburg, to import these through St Petersburg instead.Footnote 101 In 1721, the Tsar forced foreigners to move their bank accounts from the old Hanseatic port of Archangelsk to St Petersburg. While Archangelsk declined, St Petersburg ascended to become the growing empire’s primary port.Footnote 102 This necessarily also affected Hamburg’s traditional trade to the eastern Baltic.

Furthermore, the Council explained that Hamburg’s calico printers’ decline was due to their products having been ‘banned in so many places’. The merchants themselves bore some blame for goading others into such measures: ‘[we] wish to God one [meaning the merchants] hadn’t screamed and bragged so much to foreigners about [Hamburg calicos]’, they wrote.Footnote 103 A further important sector of Hamburg’s industry which protectionist measures threatened was sugar refining. Following the Caribbean sugar revolution, production increased and prices for sugar declined. During that time, Europe’s growing middling sorts were in the process of forging a culture of their own, which relied on new habits of consumption as markers of identity.Footnote 104 They especially enjoyed ‘exotic’ goods from overseas, and added sugar to their new favourite beverages of tea and coffee.Footnote 105 By the eighteenth century, the sweet stuff had become a staple of European diets. Merchants shipped raw sugar from the Caribbean to the colonial motherlands. From there, more often than not, it was re-exported for refining. The main locations for sugar refining at the time were Copenhagen, capital of Hamburg’s long-term political nemesis, Denmark, and Amsterdam, Hamburg’s main economic rival. The third was the Elbe city itself. By the mid-eighteenth century, sugar refining constituted one of Hamburg’s most important industries.Footnote 106

European states’ new economic polies threatened Hamburg’s refineries: Prussia and Austria, Hamburg’s main markets for refined sugar, had recently begun implementing protectionist tariffs in order to foster their own fledgling sugar industries.Footnote 107 The aim was to push export-led growth through import substitution.Footnote 108 Prussia also began implementing measures to redirect trade from the Elbe, Hamburg’s main route to Central Europe, towards the Oder river to establish alternative trade routes through its Baltic ports.Footnote 109 The end of the first Silesian War in 1742 had made this possible, as Prussia had gained the greater part of Silesia, and with it control of the Oder, which connected the Baltic to Central Europe.Footnote 110 The Prussian ports on the Baltic were built in order to avoid Hamburg, serving as alternative gateways to the German lands.Footnote 111 Especially during the Seven Years War, raw sugar from the Danish West Indies was exported via Copenhagen to various Baltic ports. Numerous Hamburg sugar refineries went bankrupt during the war.Footnote 112

Unsurprisingly, the senators were highly critical of other governments’ protectionist measures. They argued that these harmed those countries’ own inhabitants. Commenting on Prussia’s efforts to establish its own sugar industry, one senator wrote: ‘I doubt, whether such means of establishing sugar refineries in a country are even feasible. After all, to be successful, such a policy would require all inhabitants to pay far higher prices for sugar than if they imported it from abroad.’Footnote 113 They argued that foreign princes implementing protectionism were under the sway of projecteers, unscrupulous businessmen, who put their own interests before their countries’. The policies these individuals lobbied for served only their own interests, while inflicting great harm on the majority of the people. ‘[The projecteers] grow rich’, the senators lamented, ‘while 100 of their fellow citizens, who formerly had plenty of bread, are impoverished.’ Footnote 114 In this instance the senators were alluding to Frederick II’s new economic policies. He aimed to further foreign trade by granting monopolies to private individuals and companies. This included monopolies on trade with sugar and tobacco, both key products of Hamburg’s processing industries.Footnote 115 Fredrick furthermore supported the founding of the Emden East Asian Company in 1751, which traded with China from Prussia’s newly acquired North Sea port of Emden, near the Dutch border, and the Bengal Company, in 1753.Footnote 116

‘If a sovereign prince wants to support certain factories in his lands, as the King of Prussia wants to develop sugar refineries in his country, and in order to do so places levies on foreign sugar, what is one supposed to do about it?’, the senators asked rhetorically in 1751.Footnote 117 After only a few years, such policies would cause the ‘sad consequences of great poverty and thirst’.Footnote 118 The senators pointed to the example of Britain, probably referring to its Navigation Acts, a set of protectionist policies which reserved trade with its colonies to British merchants and ships. They argued that while some might ‘hold [England] up as an ideal to all other nation[s]’, all was not well with this country’s business, as evidenced by ‘near daily examples of desperate suicide’. Britain was also accumulating debts in the millions and one of these days ‘all ropes will tear’ and the government fall.Footnote 119 Prussia for its part would ‘soon discover, to their own great disadvantage, that trade through the Baltic during the six months of autumn and winter will be subject to danger and retardation’.Footnote 120

Anyway, the senators asked, ‘if such regents do not want to hear of the ruin their own countries are facing and change their erroneous ways, what can Hamburg hope to gain from lifting its own, really limited tolls? How will any of the current free ports benefit?’ An abolition of levies in Hamburg would hardly make foreign princes change their erroneous ways.Footnote 121 Hamburg’s tolls were moderate to start with; hence they posed a limited burden on merchants. ‘The declining public welfare would not be improved [by abolishing them]; rather the loss of the income from tolls would further weaken it.’Footnote 122 While foreign rulers were willing to neglect their responsibility towards their subjects and implement policies that supported business people to the detriment of their fellow citizens, Hamburg’s senators were not willing to follow their example. At the same time, they recognized that as a city-republic, Hamburg’s situation was different from its territorial neighbours. According to the senators, if Hamburg alone liberalized trade while its larger neighbours did not, this would have similarly destructive consequences for its inhabitants as foreign kings’ protectionism had on their subjects.

The senators’ concern over social justice related directly to the distribution of political and economic power within the city. Lifting tolls on trade would require an alternative source of income for the public purse. In practice, this would mean a shift of the financial burden from the merchants to the city’s non-mercantile inhabitants. Not only was this unethical; it was also not practical. Changes in customs and taxation required the consent of the Bürgerschaft, which was unlikely to be forthcoming.Footnote 123 The guilds and tradespeople whose interest the Bürgerschaft represented generally did not make their living from overseas trade. An alternative levy to replace the loss of income, should the tolls be slashed, would thus burden the Bürgerschaft’s electoral base and so it was unlikely to consent.

The senators pointed out that the Commerzdeputation’s earlier pushes for a free port, in 1710 and 1727, had failed and that the Council had considered a free port but decided against it because no alternative source of income was identified.Footnote 124 To further support their argument, the senators pointed out that the main reason Amsterdam’s free port had not been established was that officials had not found an alternative revenue stream.Footnote 125 Some senators argued that ‘[a] free port does not suit a great trading city, which has great expenses to bear, for which the tolls present the primary source of income’.Footnote 126

The senators’ financial argument was immediately related to the ethical objections they raised against other states’ protectionism: they framed the tolls as a matter of the merchants’ morality and their financial responsibilities to the community. Replacing the income from the tolls through other means would amount to shifting the financial burden of public goods away from the merchant community and toward the city’s other inhabitants. As the senators explained, ‘the tolls are a levy that is certain and commonly accepted. They irritate nobody, because everybody knows and is used to them. They provide an essential public income without anyone really noticing.’Footnote 127 They argued that tolls on trade goods were fair and therefore socially acceptable:

The tolls are the most proportionate and tolerable contribution [to the public purse], as he who does not consume much, also contributes little. However, he who out of his own free will choses to consume a great deal, can and ought to also contribute to the public [accordingly].Footnote 128

Thus, only those who wanted to directly profit from trade would suffer by the tolls. This was particularly the case for the convoy tolls, which funded Hamburg merchant ships’ protection against Mediterranean piracy.Footnote 129 Moreover, the tolls were the main contribution of the business community. The merchants ought to financially contribute to the public purse, just like anyone else. Granting the merchants, who constituted one social group within the town among many, preferential treatment over others would be unjust.Footnote 130

It is likely that the Council’s worries over redistributing the city’s financial burden were fuelled not only by a sense of social justice, but by real concern over the city’s political stability. From the end of the Thirty Years War in 1648 to 1713, Hamburg descended into a ‘virtual civil war’.Footnote 131 The causes for this conflict were complicated and historians have not yet been able to fully explain them. It appears, however, that at their heart lay discontent over the relationship between the populace and the magistrates. Peace had been restored in 1712 through the intervention of an imperial commission, which reformed the city’s constitution and affirmed its Lutheran status.Footnote 132 Moreover, in 1750 and 1753, Hamburg again experienced violent protests by artisans.Footnote 133 While these episodes never reached the extent and levels of violence of the earlier protests, they likely added pressure on the city government not to pass policies that might trigger discontent among the populace.

Given these considerations, the senators wondered whether the ‘advantage the merchants obtain from lifting the tolls would far exceed the damage the public would suffer?’Footnote 134 The Commerzdeputation insisted that it would. Trade itself would boost the public good, due to the ‘benefits it created to all employment and income of people of all stations’.Footnote 135 They argued that if local merchants were ‘forced to abandon the city for more suitable locations, local citizens, tolls and the conscience would suffer’, as trade supported a ‘great number of citizens’.Footnote 136 The Commerzdeputation explained that trade was the origin of the well-being of the citizens; the more trade flourished, the more the public would benefit. An increase in trade would eventually benefit the wider public through creating jobs in related sectors. Carrier fees, rents for storage facilities, labourers, packers, insurance, and bills of exchange would all benefit from a free port, as they were connected to trade ‘like links on a chain’.Footnote 137 Should, however,

foreigners turn for their commissions to our neighbours, as they have already begun to do, shortly a great many of our merchants will find themselves without trade, a not small number of attics and warehouses without goods, and a great number of all sorts of people, who depend on the merchant for their livelihood, will be without bread.Footnote 138

Without trade, the merchants explained, ‘we are like a body without a soul.’Footnote 139 As the wealth gained from trade was the ‘soul and life of the whole city’, salvaging trade was ‘a matter of the heart for every righteous patriot’.Footnote 140 By citing patriotism, the authors appealed to its mid-eighteenth-century understanding as ‘the spirit of commitment to public service and the public good’, as Mary Lindemann defined it.Footnote 141 Accordingly, the merchants argued that for the well-being of the state and the public, ‘all other concerns have to give way, no difficulties must seem too great, to protect the continuation of commerce’.Footnote 142 The ‘patriotic goal’ at hand, they concluded, was no less than ‘saving our beloved hometown from the threat of near downfall’.Footnote 143

One of the risks that came with the loss of trade was that bills of exchange and the income derived from interest for loans would be redirected elsewhere, to the detriment of Hamburg’s financial industry. Its emergence was closely connected to the increasing importance of the colonial trades to the city’s economy. As Karin Newman explained, during the seventeenth century, the presence of a large foreign merchant community, along with its increasingly global trade and Central European location, conspired to make Hamburg ‘a major financial centre holding a key position in the international exchange system, second only to Amsterdam’.Footnote 144 At its core stood the Bank of Hamburg, a public bank which facilitated the cashless settlement of balances.Footnote 145 During the wars of the eighteenth century, this established position and Hamburg’s status as a city-republic, as well as political neutrality, enabled it to serve as a hub for wares and financial services, diplomacy, and news, outcompeting ports who were part of one of the belligerent states.Footnote 146 Hamburg insurance firms, moreover, provided securities for vessels travelling initially to the North Sea and Baltic, but increasingly to the Atlantic and Mediterranean, and ultimately to the Indian Ocean and East Asia.Footnote 147

Its integration into the Atlantic trade since the seventeenth century also transformed the city’s manufacturing sectors. While the late medieval areas of ship building and brewing declined, the processing of colonial raw materials expanded. By the mid-eighteenth century, Hamburg’s most prominent industries were sugar refining, calico printing, and tobacco processing.Footnote 148 These depended on French imports. Indeed, Hamburg’s refineries processed the greatest part of French sugar.Footnote 149 It was all part of an economic system that, the merchants claimed, a free port would ensure would continue to flourish. Any decline in trade would cause a decline in the city’s secondary industries and thus the livelihood of the people in their employ. ‘Factories’, the Commerzdeputation explained, ‘contribute greatly to [the public good] (this is an indisputable truth)’. The Commerzdeputation therefore warned: ‘Our factories are struggling: this is especially the case for sugar refineries’, but also ‘Calico printers have declined greatly.’ Indeed, calico printers, sugar refineries, and dyers, they wrote, ‘appear to be nearing their downfall’.Footnote 150 The Commerzdeputation’s warnings were warranted at least in the matter of calico: Hamburg’s calico printers depended on imports of cotton, which at this time largely originated in India and reached Europe via the Atlantic.Footnote 151 Cotton goods had emerged as the second most important item in Hamburg’s import trade during the early decades of the eighteenth century. However, between 1740 and 1786 their value fell by 94.6 per cent. Indigo, the industry’s most important dye stuff, grown in the Americas, equally declined from the 1750s.Footnote 152

The secondary industries were the reason the Commerzdeputation was particularly concerned over export tolls. The processing industries depended on markets for finished goods. Hamburg as a city-republic had no market of its own; all production had to be exported abroad. What was more, the city had no unified market in its hinterland until the introduction of the Zollverein, the German customs union of 1834. This meant that re-exports from Hamburg had to pass multiple borders where tolls were levied before reaching consumers.Footnote 153 That such duties were harmful to local industries, they claimed, was the ‘first principle of all those who have written on commerce and financial matters’. They argued that the contrast between the toll-free transito, which meant that primary goods could pass through the city without being subjected to tolls, while any products finished in local manufacturing were subject to export tolls, directed raw materials away from the city and to its competitors, thus proving a competitive disadvantage to Hamburg’s secondary industries.Footnote 154

As the above discussion shows, concern over public welfare figured strongly in Hamburg’s free port debate. Merchants and members of the Council both in favour of and against a free port framed their arguments in terms of the contribution trade did or did not make to the public good. The Council raised concern over the distribution of the burden of the city’s financial upkeep and the merchants’ responsibility of contributing to this. The Commerzdeputation agreed in principle with the Council’s ethical concerns. In their responses, they outlined how trade was linked to various other sectors of Hamburg’s economy, including sugar refining, tobacco processing, calico printing, as well as the financial industry – all of which rested on the city’s trade with the Atlantic. The merchants argued that by engaging in trade, they created jobs and income opportunities for a great number of Hamburg’s inhabitants. A free port would increase trade, and thereby benefit the urban economy as a whole. Thus, the benefits the city as a whole derived from trade with the Atlantic outweighed the financial costs of taxes to replace the income from tolls.

Conclusion

For a while now, historians have problematized the traditional understanding of European trade policies as having moved from early modern ‘mercantilist’ protectionism to nineteenth-century free trade.Footnote 155 By highlighting how rulers introduced free ports alongside the better-known protectionist policies of the English/British Navigation Acts and the French Exclusif, the new history of free ports has added further nuance to this picture. Authors like Tazzara, Stapelbroek, Røge, and Kleiser have emphasized each port’s individual circumstances and local agency for their creation.Footnote 156 In doing so, they also reacted to an earlier literature which, influenced by world system’s theory, portrayed free ports as instruments of Northwestern European domination over the ‘periphery’. Along with rejecting this simplistic model, however, historians abandoned economic explanations for the spread of free ports altogether. Given ports’ function as institutions for the facilitation of trade, this perspective, however, remains important. Considering their global economic context, I have argued, sheds light on common factors driving the proliferation of early modern free ports.

The period in which free ports originated was characterized by the biggest economic transformation of the early modern era: Atlantic trade expansion. This began in the sixteenth century, intensifying in the mid-seventeenth century with the emergence of the Caribbean plantation complex. Historians consider the resulting system of trade, connecting Europe, Africa, the Americas, and Asia, as the beginnings of globalization. They have also credited it with triggering the onset of sustained economic growth in Europe.Footnote 157 Given the far-reaching nature of these commercial changes, we may expect them to have impacted the development of local trade policies, too, including free ports.

To investigate this possibility, the first part of this article gathered all available data on early modern free ports available in the secondary literature in different European languages. This revealed, first, a strong chronological correlation between the growing numbers of free ports on the one hand and Atlantic trade expansion on the other. Second, data on the location of these ports showed their geographical spread to have been equally correlated with Atlantic trade expansion: while early free ports clustered around the Mediterranean, ports liberalized after 1650 – that is, following the Caribbean sugar revolution – were located overwhelmingly on the Atlantic, in line with the early modern shift of Europe’s centre of economic gravity in that direction.

While these correlations are striking, the quantitative data does not allow conclusions regarding causality. In order to explore the possibility of a causal relationship between Atlantic trade expansion and free ports, the second part of the article undertook a qualitative analysis of the free port debate in 1750s Hamburg. As the main entrepôt connecting production sites in the Caribbean and Eastern Europe, Hamburg played a central role for the emerging global trade system. By the mid-eighteenth century, the city had become well-integrated into the new Atlantic economy. Moreover, its constitution as a city-republic rather than a monarchy, meant that its sources allow an unusually clear view of different stakeholder groups’ motives and reasoning.

Hamburg did not become a free port at this time. The Council’s objections to the port rested on concerns over the city’s inner stability, as well as its position within the European state system. Its reasoning against a free port thus partly echoes the findings of earlier studies on individual free ports – local and regional factors mattered and, in this case, proved decisive. However, the sources also revealed that the Commerzdeputation’s arguments in favour of a free port centred entirely on securing and expanding the city’s commercial ties to the Atlantic. The merchants expressed concern that Hamburg might lose out to Amsterdam, its main rival as a hub for the importation and distribution of colonial goods across continental Europe. They argued that the Atlantic trade supported the livelihoods of a great part of the city’s population, as it supplied the raw materials for its new main industries: sugar, coffee, and calico. Hamburg’s financial industry also emerged as a side-effect of its growing entanglement in the expanding Atlantic economies. The merchants felt that a weakening of the city’s commercial ties to the Atlantic threatened both.

The evidence from Hamburg thus supports the hypothesis that the relationship between Atlantic trade expansion and the spread of free ports was no mere coincidence, but a causal one. It shows that the emergence of free trade policies was closely intertwined with that of early modern globalization: the unprecedented growth of long-distance trade provided states with an incentive to experiment with liberal trade policies alongside those of mercantilist protectionism. They considered, and sometimes chose, liberalizing trade in individual ports in order to better benefit from the opportunities the growing Atlantic economy offered. In other words, local economic policy emerged in reaction to global economic change, without being determined by it. Early modern economic globalization and local agency were not mutually exclusive. On the contrary, to fully understand local developments, we need to consider the global economic contexts which shaped them and to which they responded.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the five anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, Guido van Meersbergen for exceptional editorial guidance, Theresa Duval and Inga Lange for supporting this work in lots of different ways, Ulrich Pfister for the idea, and Patrick Wallis and Kim Czajkowski for reading early drafts of this article.

Financial support

None to declare.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Esther Sahle holds a PhD in Economic history from the London School of Economics and at present an assistant professor of economic history at the University of Copenhagen.