1. The unknowns of transitions call for creative preservation

Over time, design theory and design creativity have unfolded together through dynamic interactions (Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2011; Cascini et al. Reference Cascini, Nagai, Georgiev, Zelaya, Becattini, Boujut, Casakin, Crilly, Dekoninck, Gero, Goel, Goldschmidt, Gonçalves, Grace, Hay, Le Masson, Maher, Marjanović, Motte, Papalambros, Sosa, V, Štorga, Tversky, Yannou and Wodehouse2022). Design creativity works have contributed to identifying creativity issues of the time and hence have explicated challenges to be overcome by design theorists, who, in turn, could develop design theory that inspires new creative methods and processes to address creativity issues. As early as the 1830s in the Grand Duchy of Baden, Carl Friedrich Nebenius, a top-level civil servant in charge of the country’s education and socioeconomic development, noticed that technicians and engineers reproduced the same machines. To address this issue, he asked for education courses to help expand their creative capacities; to this end, he hired Ferdinand Redtenbacher, who formulated the ratio method, one of the most important design theories for machine design in 19th-century Germany (Nebenius Reference Nebenius1833; König Reference König1999; Heymann Reference Heymann2005; Le Masson and Weil Reference Le Masson and Weil2022). How can design theory be used to approach contemporary challenges?

Today, energy, climate or digital transitions raise new creativity issues that could require advances in design theory. In particular, a critical issue of contemporary transitions is creative preservation; one wonders how design theory can help address the challenges associated with this issue. Let us characterize this issue. First, contemporary transitions, also called grand challenges, require strong creative design efforts (Tonkinwise Reference Tonkinwise2015; Zolfagharian et al. Reference Zolfagharian, Walrave, Raven and Romme2019; Mention et al. Reference Mention, Pinto Ferreira and Torkkeli2019; McMahon and Krumdieck Reference McMahon, Krumdieck, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022; McMahon et al. Reference McMahon, Subrahmanian and Reich2022; Tarba et al. Reference Tarba, Ahammad, Gregory-Smith, Cooper and Bauer2024; Ritala Reference Ritala2024). Among the many creativity issues raised by transitions, one is particularly striking: Contemporary transitions require both creativity and preservation. For instance, historians of ‘transitions’ (Fressoz Reference Fressoz2022) have emphasized that transitions of the past did not mean the disappearance of material or energy sources (e.g., wood, coal) but rather the creative combination of past and new sources. Physicists, experts in matter transitions, would explain that this transformation involves both the radical change of all the state variables of the system and the preservation of chemical composition! Closer to design creativity, authors have emphasized that transitions require disruptive innovation combined with the preservation of ancient objects or ancestral techniques preservation (Verger et al. Reference Verger, Duymedjian, Wegener and Glăveanu2024), possibly with incumbent firms (Bergek et al. Reference Bergek, Berggren, Magnusson and Hobday2013; Abadzhiev et al. Reference Abadzhiev, Sukhov and Johnson2023), with certain continuities (Tonkinwise Reference Tonkinwise2015) or with keeping (parts of) engineering systems (McMahon and Krumdieck Reference McMahon, Krumdieck, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022; Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen, Vermaas, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022a): Creativity is required to design sustainable energy, mobility, ways of living, supply chains of circular economy and so forth, but preservation is required to preserve natural resources, biodiversity, societal cohesion or, more specifically, existing complex engineering systems in energy, communication, transportation, healthcare and so forth Hence, transitions call for a non-Schumpeterian innovation: not creative destruction but creative preservation (see Appendix A1).

Second, creative preservation raises specific questions related to design theory. Without going here into all the details provided in Section 2, we need to emphasize why design theory can help address creative preservation. We recall that design theory is needed to help designers overcome fixations to increase their generativity (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson and Weil2011b; Agogué et al. Reference Agogué, Hooge, Arnoux and Brown2014; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Weil and Hatchuel2017). In the case of creative preservation, there is a risk of specific fixations: As we will show in Section 2, creative preservation should not be limited to a trade-off between tradition and innovation; it should not be limited to the reuse of existing objects or techniques (because reusing does not necessarily mean preservation and/or creativity) nor to design within a predefined generative model (because this ‘within’ implies limits to creativity and overlooks the logic of ‘generative constraint’ related to creative preservation – e.g., Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel, Weil, Tromp, Sternberg and Ambrose2023b). There is a strong generativity in creative preservation, which we can illustrate through famous cases within different design fields: Einstein formulated special relativity, a highly creative theory that preserves Newtonian physics at low speed by smartly relying on Lorentz transformation (Holton Reference Holton1981); across several centuries, culinary art has revisited past tradition to invent radically new ‘grande cuisine’ (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson, Weil and Carvajal-Perez2019); artists constantly revisit past traditions to build new artistic worlds in which past artists are included, such as Hiramatsu Reiji’s creative preservation of Monet paintings (Koyama-Richard and Candil Reference Koyama-Richard and Candil2018). Hence, the research gap that this article contributes to bridging: How can design theory account for the generativity of creative preservation and help overcome the typical fixations related to creative preservation?

This paper consists of three sections. In Section 2, we show how advances in design theory and creativity methods lead to the framing of specific research questions related to the generativity of creative preservation. We also explain why an extension of design theory is needed to answer these questions. In Section 3, we build one extension by combining C-K design theory (C for concept, K for knowledge) with topos theory. This theoretical section also uses as a ‘red thread’ an illustrative case involving the design of the renovation of a local railroad in France (a typical case of sustainable mobility that requires creative preservation). In Section 4, we show how the resulting C-K/Topos theory helps characterize the critical properties of creative preservation: (a) a large variety of design strategies, all related to creative preservation; (b) a knowledge structure that can support creative preservation, combining fixed ontology and the revision of the identity of objects and (c) a design process that (curiously enough) combines strong predictability and open-endedness. In this section, we also show how C-K/Topos enables us to highlight key features of ‘creative preservation’ cases in the literature. We discuss the implications of C-K/Topos for the management of creative preservation.

2. Uncovering the generativity of creative preservation with design theory

Creative preservation appears to be a promising notion for the design of transitions. However, restrictive interpretations can lead to critical design fixations. We first analyze some of these restrictive intuitive interpretations of the notion; this helps us better characterize where existing design theory can already be of service and where extension of design theory is needed to better account for the specific generativity of creative preservation.

2.1. The paradoxes of creative preservation

We characterize three ‘paradoxes’ from the literature – we refer to them as ‘paradoxes’ (para-doxa, against the beliefs) in the sense that these are results known in the literature that tend to go against received wisdom.

1. Self-evidently, creative preservation can be seen as a trade-off between preserving traditions (such as design rules, routines, object features, technologies and requirements) and proposing innovation (such as new uses, new features and new materials such as biomaterials, new architectures and new technologies such as digital technology). Creative preservation would appear to find the balance between what must be kept and what must be modified via a combinatorial logic wherein the designer should find the balance between two conflicting types of attributes. Such a process can appear as creative preservation, but creative preservation cannot be limited to this; beyond the trade-off, one can expect that creative preservation consists of being very creative to preserve (Carvajal Pérez et al. Reference Carvajal Pérez, Le Masson, Weil, Araud and Chaperon2020); hence, creativity would appear as a means at the service of preservation or vice versa and preservation would appear as leverage for creativity. In this logic of generative constraint (Tromp et al. Reference Tromp, Sternberg and Ambrose2024; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel, Weil, Tromp, Sternberg and Ambrose2023b), creativity and preservation are not necessarily in opposition; they can be in symbiosis (Paradox 1).

2. Authors recently identified practices for creative preservation, such as upcycling, bricolage, low-tech and crafts (Verger et al. Reference Verger, Duymedjian, Wegener and Glăveanu2024). They propose a ‘working definition of creative preservation [that] refers to practices of creation that prevent the decay of existing materials and ideas by updating and adapting them, or reexpressing them in another way through the exploration of their affordances’ (Verger et al. Reference Verger, Duymedjian, Wegener and Glăveanu2024, p. 270). Descriptions of these practices actually highlight two critical aspects of creative preservation:

a) On the one hand, the reuse of an object or existing material is not necessary preservation – think of the people in Europe during the High Middle Ages reusing stone from the monuments of antiquity and thereby destroying them; or, more subtly, think of a plagiarist artist making use of another painter’s techniques or motives without making sense of it. Hence, the reuse of something in a design process does not mean that this something is preserved: reusing does not mean preserving (Paradox 2a).

b) On the other hand, creative preservation is not always a two-step process where the designer begins by declaring what must be preserved and then is creative – in creative preservation, what must be preserved can emerge during the design process (and not necessarily before the design process!). In other words, the design process of creative preservation should account for the design of what has to be preserved (Paradox 2b).

In brief, in creative preservation, preservation is not limited to reuse and has to be designed (Paradox 2).

3. Another approach to the task of creative preservation consists of remembering that, historically speaking, creative destruction was already overcome by engineering department practices relying on generative models that enable a large variety of creative combinations (Reuleaux Reference Reuleaux and Debize1877; König Reference König1999; Heymann Reference Heymann2005; Le Masson and Weil Reference Le Masson and Weil2013; Lachmayer et al. Reference Lachmayer, Mozgova, Reimche, Colditz, Mroz and Gottwald2014; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2021); this notion of combinatorial generativity is present in many domains (Boden Reference Boden and Sternberg1999; Epstein Reference Epstein, Runco and Prtzker1999; Zittrain Reference Zittrain2006). These practices of combinatorial creation within a given ‘generative grammar’ can be considered creative preservation, but they also raise the following questions: Should accounting for creative preservation encompass the design of the ‘generative model’ itself? Should it also account for the stability (or regeneration!) of this generative model itself over repeated design? How long can one ‘preserve’ and are there limits to repeated ‘creative preservation’ design? Hence, creative preservation can go beyond a combinatorial generativity within a generative grammar and should encompass (repeated) creative preservation design (Paradox 3).

These paradoxes emphasize the facts that (a) creative preservation can be interpreted in a ‘fixated’ way (Duncker Reference Duncker1945; Jansson and Smith Reference Jansson and Smith1991; Crilly Reference Crilly2015) and (b) the generativity potential of the notion can be very high, provided that designers can overcome fixations. This is where design theory can be helpful: How can one use design theory to account for creative preservation and support defixation in creative preservation design processes?

2.2. Creative preservation raises questions about design theory

We do not provide an overview here of all the available proposals for design theory. We focus on three approaches that have already proposed combining creation and preservation: systematic design, the design theory of engineering systems and C-K design theory.

2.2.1. Creative preservation and systematic design

Systematic design (Pahl and Beitz Reference Pahl, Beitz and Arnold Pomerans1977; Bender and Gericke Reference Bender and Gericke2021) is a design theory that relies strongly on preexisting engineering knowledge (see multiple knowledge libraries on functions, conceptual models, embodiment etc.) to support design creativity. This logic of creativity has often been overlooked but was strongly underlined in the recent reedition of Pahl & Beitz’s book by Bender and Gericke (Reference Bender and Gericke2021). Hence, it can be considered a form of creative preservation. It has been shown that this logic of preserving engineering knowledge (reusing, accumulating, etc.) can be repeated over several design projects and hence be extremely generative (Reuleaux Reference Reuleaux and Debize1877; König Reference König1999; Heymann Reference Heymann2005; Le Masson and Weil Reference Le Masson and Weil2013; Lachmayer et al. Reference Lachmayer, Mozgova, Reimche, Colditz, Mroz and Gottwald2014; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2021). We learn here that creative preservation in systematic design depends on knowledge collection, knowledge organization in different types (functional, conceptual and embodiment) and a highly structured way to make use of the accumulated knowledge during the design process (first functional knowledge, then conceptual models and then embodied knowledge).

However, systematic design remains inconclusive with respect to some of the paradoxes mentioned above: First, it is unclear whether and how the preservation of certain design rules could lead to a form of creativity (see Paradox 1 ‘beyond trade-off’). Second, how does creativity in the systematic design process preserve or renew the design rules – that is, how can it be avoided that creativity breaks certain rules or how can new rules be elaborated in the design process and preserved in the future in coherence with past ones (Paradoxes 2a and 2b)? Third, how can the dynamics of the systematic design process over repeated design processes be predicted? Is there a limit to creative preservation in systematic design (e.g., fixation on outdated design rules) and are there ways to overcome possible limitations? (Paradox 3).

2.2.2. Creative preservation and systems engineering

The recent synthesis of design theory for engineering system design (Isaksson et al. Reference Isaksson, Wynn, Eckert, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022) highlights that the theory of technical systems (developed by Hubka and Eder Reference Hubka and Eder1988) and then extended and improved by Andreasen et al. Reference Andreasen, Howard, Bruun, Chakrabarti and Blessing2014 and Štorga et al. Reference Štorga, Myrup and Marjanović2010 aims at proposing a model of technical systems that is general enough to evolve “from one existing state to desired state through a sociotechnological transformation system” (Isaksson et al. Reference Isaksson, Wynn, Eckert, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022, p. 78). Hence, the technical system model contains both states and is preserved in the transformation. From this perspective, the theory of the technical system appears to be a creative preservation that is based on one ‘generative model’ (the model of the technical system and its related transformation system) that contains potential creative evolution. In the (re)design of complex engineering systems (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen, Vermaas, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022c), this approach could help guide the ‘design intervention’: An ideal ‘theory of the system’ could account for the existing engineering system (e.g., telecommunication, energy supply and healthcare), for the desired systems and for the transformation from the existing to the desired system.

However, these authors have also highlighted some limits or open questions (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen, Vermaas, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022a) related to some of the abovementioned paradoxes. One first open question is how to design the relevant theory for a particular system that must be transformed via an ‘intervention’ logic, hence preserving without knowing in advance what must be preserved (this corresponds to Paradoxes 2a and 2b). A second open question is how to ensure that the redesign process does not ‘break the theory of the system’ via a disruptive logic that appears beyond the scope of engineering system design. (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen, Vermaas, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022c) has analyzed this question thoroughly (see pp. 17–18), proposing, first, to consider that innovation and engineering system design could be in opposition (hence they encounter Paradox 1: Creative preservation would be a trade-off?); they also propose to go beyond this ‘trade-off’ logic and analyze innovation in engineering system design either as ‘longer-term accumulations of smaller changes’ (p. 18) or as ‘tipping points […][i.e.,] a series of design interventions in engineering systems can bring a system to a rapid transition’ (p. 18). These propositions raise questions about the logic of creative preservation: Is this the end of preservation? Or a more creative preservation? Such propositions call for a design theory that could account for the variety and complexity of preservation strategies (Paradox 1) and could also contribute to our understanding of the dynamics of repeated creative preservation (Paradox 3).

2.2.3. Creative preservation and C-K theory

C-K theory (Hatchuel and Weil Reference Hatchuel and Weil2009) is known as a theory that can account for strong generativity (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson, Reich, Weil, Culley, Hicks, McAloone, Howard and Reich2011a), including rule breaking and the redefinition of the identity of objects (Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Weil and Hatchuel2017; Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson, Reich and Subrahmanian2018). It is also well known for helping manage fixations (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson and Weil2011b). In C-K theory, preservation is not impossible: C-K theory can include knowledge reuse, and it includes knowledge-reordering phases (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Weil and Le Masson2013) in which ‘old’ knowledge (available at the start of the design process) and new knowledge (obtained through the design process) are well articulated.

However, C-K theory does not provide a clear understanding of the intricacies that characterize the relationship between preservation and creativity. Paradox 1 (beyond trade-off): Examples of the use of C-K theory tend to focus on how C-K theory can break the design rules – preservation is not impossible and can certainly be understood as a generative constraint (Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel, Weil, Tromp, Sternberg and Ambrose2023b) – but this has yet to be demonstrated. Paradoxes 2a and 2b (beyond reuse, beyond predefined preservation): Typically, C-K theory clearly accounts for K-reuse and predefined K-preservation (when the design decides not to break specific design rules), but as we have shown, the critical point is that reusing is not preserving and preservation does not occur only at the beginning of the design process and can actually be designed during the design process; again, it has not been proven that C-K theory cannot account for these processes, but we still need formal proof that it can do so and how it does so. Paradox 3 (include repetition): C-K theory is well adapted to account for repeated innovation (see several demonstrations, such as Hatchuel and Le Masson Reference Hatchuel and Le Masson2006; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Weil and Hatchuel2010), but we still need to investigate the dynamics of repeated creative preservation.

2.3. Research questions and methods: Extending design theory to elicit creative preservation paradoxes

On the basis of this literature review, we clarify our research questions. We would like to account for the paradoxes emphasized above, hence contributing to overcoming fixations related to creative preservation. We can reformulate the paradoxes into the following research questions:

Research Question 1 is related to the basic aporia of creative preservation: How can design theory help go beyond trade-off and account for the variety of preservation strategies, that is, the various ways in which preservation leverages creativity, and, vice versa, creativity enables unexpected preservation?

Research Questions 2a and 2b relate to the creative preservation process, aiming at going beyond reuse and beyond ‘predefined preservation’. Research Question 2a: Beyond reuse, how can design theory account for the complexity of ‘knowledge preservation’, including the preservation of complex semantic networks and meanings? Research Question 2b: Beyond predefined preservation, how can design theory account for the design of what is preserved during the creative preservation design process?

Research Question 3 relates to repeated creative preservation: Given that the ‘creative preservation’ design process should account for the repetition of design processes with creative preservation, how ‘easy’ is repeated ‘preservation? Are there limits to repeated ‘creative preservation’?

The literature review also guides us in terms of method: Since all the approaches that we reviewed are compatible with creative preservation, we can rely on them. Since these same theories also fail to elicit rich and complex creative preservation processes that would go beyond the paradoxes, we need to extend this theory to better account for creative preservation design. Hence, our method is as follows:

a) We decide to rely on C-K theory, a highly generative design theory that has already been proven to be relevant for overcoming fixations and is not contradictory to creative preservation. For readers who are not familiar with C-K theory, it accounts for design generativity by considering two spaces: K space (knowledge space), where propositions have a logical status (true or false, e.g., engineering rules) and C space (concept space), where propositions are neither true nor false but are partially unknown – a space for chimera, imagination and so forth (e.g., “an affordable renovation of a local railroad”). In C-K theory, the design process combines four operators: from K to C (using knowledge to create new concepts); from C to K (a concept stimulates the creation of knowledge); from K to K (deduction, inference, observation, simulation, optimization etc.) and from C to C (controlling the rigor of the C-exploration). A design process results in an expansion of C (new ideas, products etc.) and of K (new knowledge, competences, scientific progress etc.). An illustration of C-K graphs is given in Figure 1.

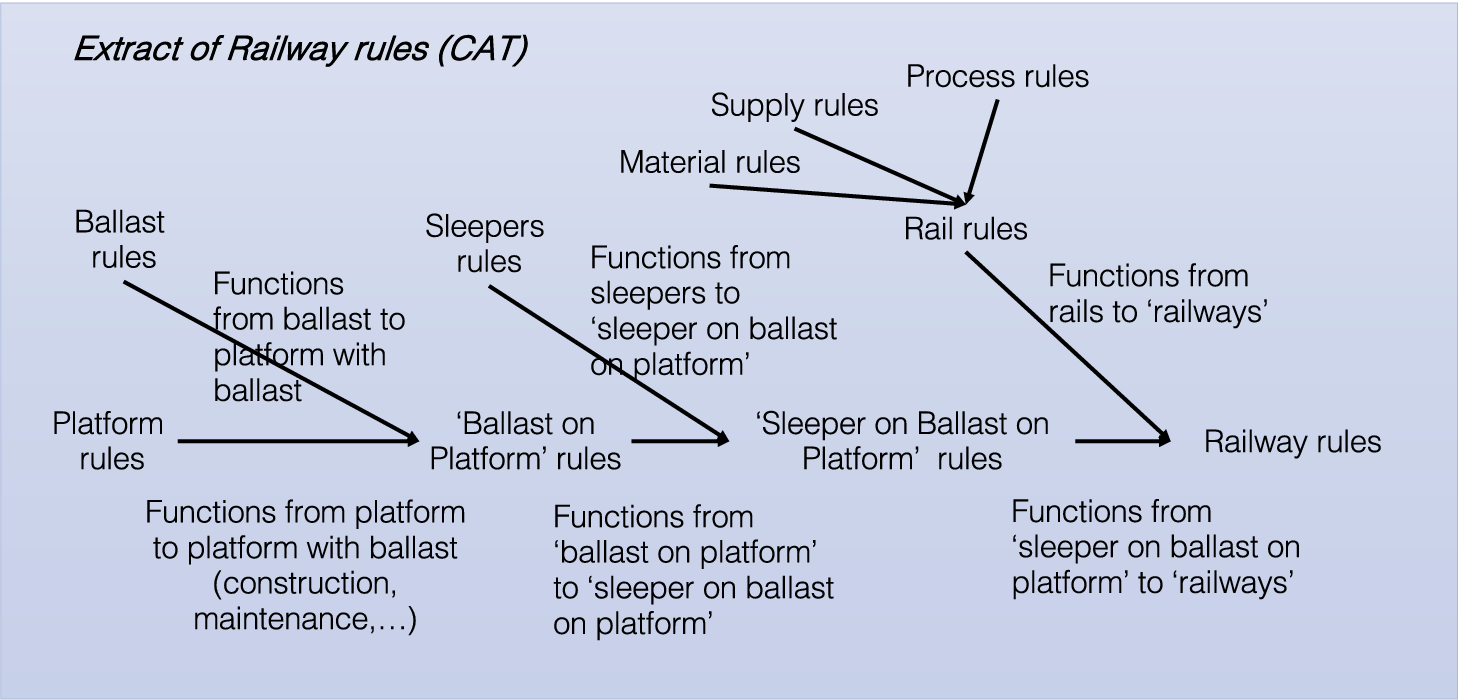

Figure 1. A simplified C-K representation of one of the design paths for creative preservation in the renovation of a local railroad.

b) Knowledge structures play a critical role in the creative preservation of systematic design or in the theory of the technical system. In contrast, in C-K theory, knowledge structure is said to be a “free parameter” of the theory. This means that it is possible to develop specific models of C-K with a specific knowledge structure X in K; these models are called C-K/X (this method has already been used in several papers; see Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Weil and Le Masson2013; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel, Kokshagina and Weil2016a; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, El Qaoumi, Hatchuel and Weil2019; Bordas et al. Reference Bordas, Le Masson, Weil and Thomas2024).

c) In this article, we choose to rely on topos theory for X, and we develop C-K/Topos. As we will show below, this toposic knowledge structure is coherent with knowledge structures available in the systematic design and in the theory of technical systems and it is compatible with the generative power of C-K theory.

d) In the following section, we develop the C-K/Topos model. Given the abstraction of C-K/Topos, we use one illustrative case (the renovation of a local railroad by the French railroad company SNCF Reseau) as a red thread throughout the theoretical development. We know that it is highly unconventional to mix theory and example – we ask the reader to bear with us. Topos theory, developed in the 1960s by Alexander Grothendieck (Fields Medal 1966), is producing increasingly groundbreaking results in the mathematics community (Caramello Reference Caramello2017). Many new disciplines have begun using it, particularly in engineering (Breiner and Subrahmanian Reference Breiner and Subrahmanian2017; Rosiak Reference Rosiak2022). However, it remains relatively little known, and we will try to make it as accessible as possible in this article, both on the basis of our simplified case on railroad renovation and through the presentation of a simple (yet not trivial) topos case presented as introductory case below.

e) In the final section, we show how some unique properties of the C-K/Topos model contribute to addressing the research questions. We can translate the research questions into the C-K/Topos as follows:

-

- Research Question 1 reformulated in C-K terms: We need to show how C-K/Topos clarifies the variety of creative preservation strategies beyond trade-off, and this should be visible in the C-space structure of C-K/Topos.

-

- Research Question 2 reformulated in C-K terms: We need to show how knowledge preservation and knowledge creation logics unfold in the K space of C-K/Topos.

-

- Research Question 3 reformulated in C-K terms: We need to show how C-K/Topos predicts the development of repeated creative preservation processes, and this should result from an analysis of patterns of repeated ‘dual expansions’ of C-K/Topos.

In this final section, we illustrate these C-K/Topos properties through some cases from the literature.

3. Developing design theory for creative preservation: C-K/Topos

3.1. Introductory case – Renovation of a local railroad in France

We provide a quick presentation of the case of the renovation of a local railroad, with a first analysis in the C-K analytical framework (Figure 1). In France, there is a very large network of old local railroads (approx. 9200 km). They contribute to territorial cohesion and low-emission transportation, but their maintenance is a complex and costly issue, framed by a massive set of engineering rules (called ‘referentials’), and several thousand pages of sociotechnical rules should be applied to ensure safe railway exploitation.

The design issue is as follows: For one given local railroad, how can its renovation be designed? (see simplified C-K; Figure 1). A design path could be ‘by changing the railroad engineering rules’ – but this design path is actually too costly (because it would imply the redesign of rules, their scientific and legal validation at the national level etc.); hence, the alternate design path involves preserving the railroad engineering rules. If the designers try to apply the rules by considering that each element (to simplify: the elements are platform, ballast, sleepers and rail) is known, then the designers will tend to consider existing elements, but these elements become older and older, and there is a risk that this aging assembly no longer meets the rules and that the railroad will be considered invalid and will be closed; alternatively, the designers will propose replacing every old material with new material, and there is a risk that it will be much too costly (see Appendix A2) – hence, a design dead end.

However, designers have creatively investigated another path: they preserve the rules while accepting that some elements are unknown – and they design the unknown elements by following the engineering rules. For instance, they consider that the rail is unknown (while the platform, the ballast and the sleepers are kept unchanged), and they design the unknown rail accordingly. One issue for this design path is to obtain the required rigidity for the railroad, whereas all the basic elements (platform, ballast and sleepers) are old. Designers discovered that a relevant newly designed rail would be inspired by long-welded rails (of the kind used on high-speed train railroads), which would have the advantage of bringing rigidity to the whole system (old platform, old ballast, old sleeper and new rail). This newly designed solution is evaluated as valid and not excessively costly (affordable in terms of cost).

Some properties of this design are as follows:

a) This design represents a successful design for transitions: The design helps preserve a low-emission transportation system at a sustainable cost.

b) There is creativity and preservation: Engineering rules are preserved, as are many elements of the past railroad (platform, ballast and sleepers); creativity is visible in the highly original idea to use types of rails that had been considered for high-speed trains and not for local railroads.

c) This design represents more than a trade-off (see Research Question 1): A trade-off would have been a design solution between ‘keep all elements versus replace all elements’ without ‘unknown’; here, the long-welded-rail solution is not just “replace the old rail with a new version of the previous rail” but is a newly designed rail that enables us to retain far more elements than initially expected.

d) What is preserved was not predefined ex ante before the design process – the design process consisted precisely of exploring whether and how the platform, ballast and sleepers could be preserved (see Research Question 2b). ‘Reuse’ does not describe what is preserved (Research Question 2a): Strangely enough, the designer ‘reused’ long-welded rail, but this cannot be seen as a preservation in the sense that these long-welded rails are used in very different contexts (new functional requirements, new railroad context etc.) and hence actually require some work for a full validation of the solution.

e) Engineering knowledge plays a critical role in supporting the creative design of a solution; further analysis is needed to understand the knowledge structure that actually supports the creative preservation design process.

We now develop a theoretical framework that will help analyze the case.

3.2. Why C-K/Topos?

As briefly demonstrated above, there is a long tradition of knowledge structures for design. The first tradition of linking design to mathematical approaches developed after Herbert Simon described knowledge as “sets of rules”. Later, knowledge was described with ontologies or type models. In mathematics, the past few decades have seen scholars assess the generality, richness and power of topos theory, which introduces highly flexible representations of knowledge that can address global and local knowledge structures (Caramello Reference Caramello2017; see Appendix A3). Topos theory also combines, in a unique and general way, spatial properties and logic. Thus, topos theory appears to be the best means of formalizing X in C-K/X for the following reasons.

a) Topos theory has generative power: It has been demonstrated as corresponding to the models used in set theory (cf. Lawvere Reference Lawvere1964; Tierney Reference Tierney and Lawvere1972). In particular, it has been shown that the technique of forcing (Cohen Reference Cohen1963), which is a form of design used in models of set theory, can be generalized in topos theory (Tierney Reference Tierney and Lawvere1972). Note that topos theory also contains the notions of graphs and topological spaces; thus, it contains all the models already used in C-K theory and can generalize them.

b) Topos theory captures universes that present layers of information and are too complex to be described by sets and standard logic. Hence, they are adapted to models of complex engineering systems (such as those of the theory of technical systems) or complex engineering knowledge (as mobilized in systematic design).

c) Intuitively, Prouté aimed to develop a software package to teach mathematics, including its creative aspect. Hence, Prouté was effectively working on creative preservation logics in mathematics, for which the fundamental framework was topos theory (Prouté Reference Prouté2007). Hence, we follow Prouté here.

3.3. Basic assumption: Developing a category Cat in the knowledge space

In C-K theory, the K space contains propositions that are either true or false. To construct C-K/Topos, we assume that some of these propositions can be organized into a category (Assumption 1).

By definition, a category comprises objects and arrows (or morphisms from one object to another) such that there is an identity arrow for each object and arrows are stable by composition (if there is an arrow from A to B and an arrow from B to C, then there is an arrow from A to C). The category Set consists of objects that are sets, and arrows that are functions between those sets (it is a category because of the classical properties of sets and functions). A category is a general notion that is widely used in many disciplines, particularly in engineering science (Spivak Reference Spivak2013; Breiner and Subrahmanian Reference Breiner and Subrahmanian2017). Hence, it is not a strong assumption to consider that some of the propositions in K can be organized into a category.

In the case of the railroad, we can, for instance, deduce from all the design rules the category below (Figure 2, highly simplified for the sake of illustration): The objects are platform rules, ballast rules, sleeper rules, and rail rules but also ‘ballast on platform rules’, ‘railway’ and so forth; the arrows are the rules that relate one object (the source) to another (the target), for example, the rules to apply to make the rail related to the railway (construction, maintenance, etc.).

Figure 2. A (highly simplified) extract of the category of railway engineering rules.

In this first step, ‘engineering rules’ were represented into a Cat. In the second step, let us consider how engineering ‘objects’ (artifacts) can now be represented on the basis of Cat. Set theory is a well-known tool in mathematics that allows us to study collections (of artifacts) and relationships between these collections via functions (e.g., engineering rules seen as properties shared by some objects). Category theory takes this much further: It begins with the rules and helps represent different ‘artifacts’ derived from the Cat. Let us explain this second step.

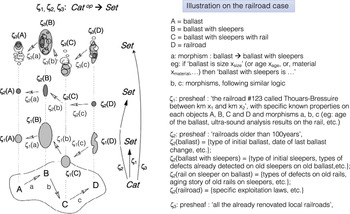

Associated with this category, denoted Cat, we have all of the applications ζ(Cat), called presheaves, defined from Cat to Set (see Figure 3, derived from Kostecki Reference Kostecki2011); hence, each ζ associates particular sets with each object and morphism of the Cat. Each of these ζ can be seen as specific (set of) instantiations of Cat. For instance, one presheaf ζ could be ‘the specific railway section between km x and km y’ for which there is a specific platform, specific ballast, specific sleepers, specific rails, with specific relations and so forth. Another presheaf could be ‘railroads older than 100 years’ (see Figure 3). The family of all these presheaves is a topos (see Appendix A4).

Figure 3. A category and its presheaves. The category Cat has objects A, B, C and D and arrows a, b and c (and the compositions thereof); ζ1, ζ2 and ζ3 are presheaves of sets on Cat. (From Kostecki (Reference Kostecki2011)) – on the right-hand side: illustration of the ‘railroad’ case.

For instance, one particular presheaf can consist of a data structure that is made of local data/observations that are mapped onto our category, and in this case, the category brings a strong formalism determining the meaning of local data/observations. Note that a presheaf does not guarantee consistency: How do local observations build a coherent global observation? This issue will be addressed with the notion of the ‘sheaf’, presented below. In general, a presheaf can be locally defined without necessarily having global consistency yet. For instance, a presheaf enables the consideration of one railroad section made of two different subsections, each with different types of ballast (or sleepers or even rail gauges!). One might want to design a consistent ‘global’ railroad on the basis of these two different, apparently incompatible subsections; hence, a presheaf can be a starting point for the design of complex interfaces or strange syntheses (we thank one anonymous reviewer for suggesting this example). More generally, Cat being the language of all known relations between objects, a presheaf is precisely a way to design with these relations and, more subtle, to explore the design of new relations, that is, new interfaces.

More generally, a presheaf is not composed solely of ‘observations’: One can describe with the same formalism presheaves that are composed of expected properties that have not necessarily been observed yet. For instance, a presheaf might be given by ‘the (future) renovated railroad between km x and km y’.

Metaphorically, the category Cat plays the role of a basic geometry or space in which one describes specific (railways) artifacts (real ones or theoretical combinations of engineering rules). Note that in the presheaves, one can find all the previous railways (that follow the engineering rules) as well as many combinations of engineering rules that are not (not yet?) real artifacts: The already-known objects and combinations are contained in this topos. This is one of the beauties of the topos approach: One can account for the ‘artifactualization’ of engineering rules, with the following critical properties for engineering designers:

a) One can account for ‘unfinished’ artifacts, in the sense that a specific presheaf ζ can be silent on certain objects of the Cat, considered ‘unknown’;

b) One can speak of the artifacts based on the ‘relationships’ between objects and without specifying the particular objects we are speaking of. This is a common approach in engineering design, where designers deal with rules, regularities, properties and so forth, and not only with a singular existing artifact;

c) This approach represents a rich way to account for the back-and-forth movement from singular artifacts and rules, showing how artifacts follow the rules and how the rules lead to the design of an artifact. For instance, as suggested by a reviewer, one can use the category to compute the cost of a particular railroad section renovation project, and conversely, one can use a target cost to design alternative renovation projects for this particular railroad section.

3.4. Design process in C-K/Topos

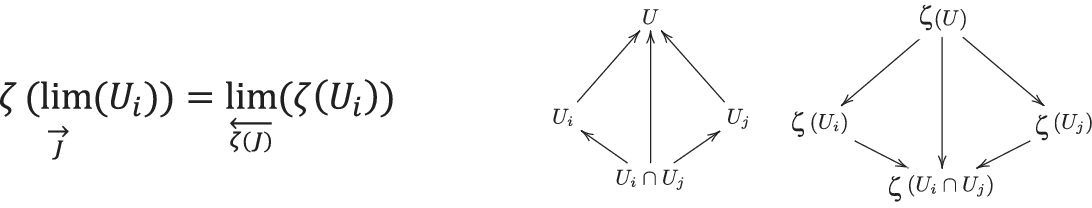

We now discuss how design develops in C-K/Topos. Note that we present here a simplified process, which we will explain later how to generalize. In this simplified process, we clarify the following (critical) points: (i) how, from the category Cat, we can derive specific concepts in the C space (recall that a concept C in C-K theory is a proposition interpretable in K but without logical status, hence not in K space) and (ii) how we can design from one of these concepts (and hence obtain refinements of the concept with dual expansions in C and K spaces) to ‘validate’ a design solution derived by refinement from one concept (in C-K term: a conjunction), that is, consider that these concepts C become knowledge. We will need a critical notion of topos theory: the notion of Grothendieck topology.

Let us begin with the railway case and, more specifically, the moment where designers would like to design a renovation strategy that (i) keeps the engineering referential (and hence is based on the Cat); (ii) also keeps platform, ballast and sleepers, as they are on the railroad to be renovated and (iii) considers that the rails are unknown and have to be ‘designed’. This formulation corresponds to a presheaf on Cat, but we cannot specify the value of this presheaf for all objects of Cat because the rail is unknown (this is a concept in C-K theory). How can one ‘validate’ this presheaf, that is, check that, after some refinements, the concept can be considered as known?

A self-evident case is when all the objects are well identified. In that case, the designers make one simple partition: They decide to consider one known rail ‘xyz’ in place of the previously unknown rail, that is, they ‘show’ a rail, so that now all the objects are known and it becomes possible to state whether the system is true or false – this is a conjunction in C-K theory, and, in topos theory, one can state that now the presheaf can be said to be a sheaf, under the specific validation criterion ‘all objects are well identified’.

However, there are more complex, highly interesting cases: Perhaps the rail can be deduced from all the known elements in the presheaf (and its related Cat); in that case, the designers would use knowledge or create new knowledge to draw a ‘deduction’ so that the rail becomes sufficiently known. If one accepts this technique of validation (where the rail it not fully instantiated but is yet sufficiently known), this also creates a conjunction in C-K theory, and in topos theory, the presheaf is also said to be a sheaf, but this time it is a sheaf with different validation criteria (since deductions on rails are allowed).

The critical point is that as soon as one decides to preserve the Cat, then there are several possibilities for validation criteria (linked to the variety of allowed deductions) associated with the Cat. As a consequence, for a given C0 and a Cat to be preserved, one should distinguish two steps in the design process:

-

i) The designers decide whether they will accept drawing deductions and which ‘deductions’ they may draw. In doing so, designers actually design what, in Cat, cannot be deduced (and hence is considered as known, as ‘preserved’), and what, in the same Cat, can be deduced. This design creates a particular structure of Cat called a topology (denoted J in the rest of this paper).

-

ii) Then, the designers begin to ‘deduce’ and add specific deduction functions on the presheaf ‘inside’ the given topology to transform the presheaf into a J-sheaf, that is, a sheaf validated in the J topology.

These steps describe design with topos. For a given Cat (to be preserved), a mathematician can ‘decide’ to leave more or less freedom for ‘deduction’; this ‘degree of freedom’ corresponds to a particular topology and this topology corresponds to a particular preservation strategy ‘inside’ the Cat. In terms of C-K theory, a topology has two facets:

-

a) From K to C, a topology creatively characterizes how the Cat is ‘injected’ into the C0, which part will be considered known (and hence ‘preserved’) and which part is ‘unknown’ (and has to be preserved as part of Cat);

-

b) From C to K, a topology characterizes the conjunction conditions.

The great input of topos theory lies in the fact that it enables to build on critical properties to model C-K/Topos design process (and then account for creative preservation):

-

1. Topos theory tells us that there are actually some limits to the designer’s freedom: For a given Cat, not everything can be deducted; that is, there are always some minimal ‘given’ elements required to begin drawing mathematical deductions. This concept is one of the great contributions made by Grothendieck, clarifying the rules for being a ‘relevant’ topology – a topology that is today called a ‘Grothendieck topology’ J (see Appendix A5). The pair (Cat, J) is called a site; a site characterizes a certain space composed of rules (the Cat) in which it is possible to generate (deductive) mathematics! A topology J fixes the elements that must be known to draw deductions in the Site – hence, it corresponds to a specific preservation strategy within a given Cat.

-

2. The surprise is that there are many possible Grothendieck topologies and it is possible to identify all the Grothendieck topologies associated with a given Cat systematically, that is, to identify all the different kinds of ‘deductive freedom’ left to mathematicians within a given Cat (see Appendix A6). This possibility can be seen as the first ‘magic’ of topos theory for design.

From our railway example, we understand that for one given Cat (the engineering referential), we can have several J corresponding to different preservation strategies: either we leave no space for deduction, in which case, for instance, the rail must be known ‘from the start’ – this corresponds to a specific topology, called discrete topology, Jdiscrete; or we leave space for deduction, in which case, the rail can be initially unknown, and designers will design the ‘deduction’ – this corresponds to another topology and can be seen as a dense topology, Jdense.

-

3. The (second) magic of topos theory for design is the notion of sheafification: A powerful theorem in topos theory states that in a site (Cat, J), for any presheaf ζ that is not a J-sheaf, it is possible to associate a J-sheaf that contains the presheaf ζ (see Appendix A7). This is called a sheafification. In the C-K/Topos design process, sheafification indicates that, at the expense of some knowledge expansion (the new sheaf is an extension of the presheaf), the design process can always end with a conjunction (note that this conjunction might be true – there is a newly designed solution at the site (Cat, J) – or false – it is proven that there is no solution at the site (Cat, J)) (for an in-depth study of sheafification in the design process, see Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2023a; note that Lawvere and Tierney showed precisely that forcing can be interpreted as a sheafification; Tierney Reference Tierney and Lawvere1972).

We propose in Figure 4 a very simplified illustration of design with topos based on the Ordinal-2 category. This example is actually derived from (Prouté Reference Prouté2016a, Reference Proutéb) and is developed in more detail in (Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2023a) – we thank one anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

Figure 4. Designing with topos – a simplified case.

To summarize, in C-K/Topos, a simplified design process can be described as follows (see Figure 5):

-

- Step 0: Initially, in K, there are propositions that are either true or false (in the railway case: knowledge on existing railways, on engineering rules etc.); in C, we have a usual C0 (a proposition that is neither true nor false, a desirable unknown; in the railway case: renovate a given railway).

-

- Step 1: The designer can choose to design with a certain Cat in K. C0 becomes C1 = C0 + ‘keep Cat’, and mathematically, this is a presheaf on Cat. The objective is now to ‘sheafify’ this presheaf. To this end, a Grothendieck topology is needed (in the railway case, C1 is ‘keep the engineering rules’ (and according to Assumption 1, these rules can be codified into a Cat); note that the alternative is C1’ = C0 + ‘change the engineering rules’).

-

- Step 2: With this Cat, the designer can identify possible Grothendieck topologies J on Cat, extending from the most ‘restrictive’ ones (Jdiscrete) to more ‘generative’ ones (e.g., Jdense). Within each of these J, it becomes possible to study whether the presheaf is a J-sheaf. The concept becomes C2 = C0 + ‘keep Cat’ + ‘validate in the topology J’.(In the railway case: Jdiscrete would mean ‘name each and every element of the railway and then check whether the railway is valid’; Jdense would allow the designer to study a design proposal such as ‘renovate the railway following the engineering rules, by keeping the platform, the ballast and the sleeper’ – hence with the rail being unknown).

-

- Step 3: If the presheaf is not a J-sheaf, then the presheaf must be designed further within the (Cat, J). Sheafification ensures that this process will always result in a J-sheaf.

-

○ At this point of the C-K/Topos design process, a first solution (step 3.1) is as follows: see whether available knowledge enables ‘deduction’ (in the railway case: One could attempt to prove that, in the Cat, the engineering referential, no rail can ever be used on the preserved platform, ballast and sleepers, the chosen topology J – if this proof can be made, then the presheaf becomes a sheaf, even if a ‘false’ one).

-

○ Another solution (step 3.2) is to expand the knowledge to design a deduction (in the case of the railway: Knowledge expansion did help design a new type of long-welded rail derived from high-speed trains, so the proposition ‘renovate this railway’ becomes true).

-

Figure 5. C-K/Topos design process, superimposed on a railway renovation case.

We present this C-K/Topos design process in Figure 5 as a superimposition on the railway case shown in Figure 1.

Importantly, we present here a simplified C-K/Topos process. A more general process would consist of progressively constructing the Cat and its related J. A real design process could begin with a particular Cat (derived from available knowledge) and then expand knowledge that could open the possibility of redesigning the Cat into a new Cat’. Consequently, steps 1 and 2 in Figure 4 can actually occur in a more intertwined way.

4. How C-K/Topos accounts for creative preservation

4.1. Some unique properties of C-K/Topos: Accounting for creative preservation

We now analyze the unique properties of C-K/Topos related to creative preservation, and we address the research questions.

1. C-K/Topos accounts for well-known design strategies, particularly the trade-off between creation and preservation. In Step 1, the designer can choose to change the engineering referential, which corresponds to changing the category itself. In this case, the scope of creation is completely open, and engineering rules are lost. In Step 2, the designers have decided to preserve the rules (hence preserve Cat), and they can use these rules with a specific preservation strategy, namely, define all the objects at the start (hence choose the discrete topology Jdiscrete); for instance, all the old elements are kept – with the risk that this preservation strategy ultimately leads to closing the railroad or all the elements are replaced by new ones, and this preservation strategy leads to very costly projects, which are usually beyond the means of the funders. Between these two extreme cases, designers might investigate all the combined trade-offs ‘keep versus replace’ for each element. In this preservation strategy, Jdiscrete, the presheaf with ‘unknown rail’ is interpreted as ‘rail = false’ and hence is a sheaf that is false; that is, it cannot exist at the site (Cat, Jdiscrete). This preservation strategy, Jdiscrete, impedes innovation.

These two cases correspond to various well-known design strategies that illustrate the trade-off between preservation and creation.

2. However, C-K/Topos also accounts for creative preservation beyond the trade-off (Research Question 1). We recall Research Question 1 reformulated in C-K terms: We need to show how C-K/Topos clarifies the variety of creative preservation strategies beyond the trade-off, and this should be visible in the C-space structure of C-K/Topos.

In C-K/Topos, in the C space at step 2 (see Figure 5), there are several design paths associated with different topologies J, where J is not the discrete strategy and, hence, where some presheaves are not (yet) a J-sheaf; hence, a design process is required to transform the presheaf into a J-sheaf. Each of these topologies enables creative preservation. Topos theory teaches us that, in general, for a given Cat, there are actually many such Grothendieck topologies J. Hence, C-K/Topos accounts for a surprisingly broad range of creative preservation strategies beyond the trade-off, hence offering a first answer to Research Question 1.

Moreover, topos theory ensures that for each of the presheaves that are not J-sheaves, sheafification is possible, meaning that it is possible to design an extension of the Cat that contains the Cat and in which the presheaf is a J-sheaf (see Appendix A8). In other words, sheafification ensures that each of these diverse preservation strategies is not a design dead end; it leads to C- and K-expansions, which are the specific signatures of C-K generalizability. Hence, a second answer to Research Question 1 is offered.

Complementary remark 1: in particular, it was noticed that Cat models the relations inside complex systems of (engineering) rules and presheaves can be seen as the exploration of new ‘interfaces’ inside this system of rules: with C-K/Topos, we have a way to design new interfaces, seen as additional relations between objects of the system while keeping the system. That’s why C-K/Topos can be seen as a promising avenue to study many types of interventions in engineering systems such as ‘system redesign’ or integration of systems or the creation of new forms of symbiosis at the interface of multiple systems (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022b).

Complementary remark 2: We note that C-K/Topos overcomes an apparent opposition between ‘fixed ontology’ and ‘changing the identity of objects’ (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Weil and Le Masson2013). On the one hand, in C-K/Topos, the Cat is preserved: It appears as a ‘fixed ontology’ that does not change below C1 (see Figure 5; C1 appears at step 1, C1 = C0 + ‘keep the Cat’). On the other hand, in C-K/Topos, a dense topology (defined over Cat) ‘fixes’ some parts of the Cat and leaves the others ‘unknown’ (for deduction and sheafification), and sheafification enables the generation of systematically all the possibilities for each of the ‘unknowns’ remaining within the Cat. Performing this sheafification leads to surprising designs for these unknowns (one example being the long-welded rail), far beyond the previously known ‘instantiations’ (the known rails for local railroads, and even the known rails for high-speed trains – the long-welded rail for local railroad is a new type of rail). Hence, sheafification enables the identity of these parts to change. C-K/Topos shows how to combine ‘fixed ontology’ (Cat) and the new identities of some of the objects of this fixed ontology (J-sheafification).

3. C-K/Topos introduces elements pertaining to Research Questions 2a and 2b. We recall Research Question 2 reformulated in C-K terms: We need to show how knowledge preservation and knowledge creation logics unfold in the K space of C-K/Topos.

-

- On ‘reuse’ and preservation (Research Question 2a): Some knowledge is reused in a preservation mode, such as the engineering rules coded into Cat, but some knowledge can also be reused and deeply transformed; for example, the long-welded rails of high-speed trains inspire the design of new rails for local railways, but these rails play very different roles in the whole system.

-

- On predefined preservation (Research Question 2b): In the C-K/Topos design process, creative preservation occurs first with Cat, and in our simplified design process, the Cat is ‘predefined’ in Step 1. Then, in Step 2, the J-topology characterizes an intention to preserve some known elements of Cat and to extend others by creating knowledge (via sheafification). Hence, a J-topology characterizes another facet of preservation, and it is constructed during the design process. Accordingly, C-K/Topos shows how preservation can be a mix of ‘predefinition’ (Step 1) and ‘in-process design’ (step 2).

-

- As we explained at the end of Section 3, Figure 5 shows a simplified C-K/Topos process. In a more general approach, one should consider that the design process will more actively explore the construction of possible Categories and the exploration of their related Grothendieck topologies. Such a process describes the design of the preservation, hence providing an answer to Research Question 2.

Complementary remark: In C-K/Topos, the K-space has a specific structure – a stabilized K-structure that enables generativity. This K-structure meets what has been called elsewhere a creation heritage (Carvajal Perez et al. Reference Carvajal Perez, Araud, Chaperon, Le Masson and Weil2018; Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson, Weil and Carvajal-Perez2019; Carvajal Pérez et al. Reference Carvajal Pérez, Le Masson, Weil, Araud and Chaperon2020; Harlé et al. Reference Harlé, Le Masson and Weil2021). Explanation: In usual C-K processes, the K-space is said to be ‘archipelagic’ (Hatchuel and Weil Reference Hatchuel and Weil2009); however, it has been shown that specific knowledge structures, such as ‘splitting knowledge structure’ (Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2016b) ensure that the knowledge space can lead to generativity – but without clear control of how the splitting condition is preserved. The notion of ‘creation heritage’ describes a knowledge structure that is stable but enables generativity. C-K/Topos clarifies a model for these knowledge structures: In C-K/Topos, the K space can remain archipelagic, but following Assumption 1, there is (at least) one Cat that ‘links’ several knowledge ‘islands’ of the archipelago, and this Cat is stable by design; however, this same Cat contains topologies that ensure generativity (similarly to the splitting condition); furthermore, ‘above’ this stable Cat are expansions that simultaneously preserve and expand the Cat. Hence, in C-K/Topos, the Cat and its related sites (Cat, J) model a creation heritage.

4. C-K/Topos provides elements for Research Question 3 (repetition). We recall Research Question 3 reformulated in C-K terms: We need to show how C-K/Topos predicts the development of repeated creative preservation processes, and this should result from an analysis of (possible) patterns of repeated ‘dual expansions’ of C-K/Topos.

First, C-K/Topos guarantees that any presheaf that is not a J-sheaf can be sheafified in (Cat, J) through an extension of the presheaf into a (‘bigger’) sheaf. Such a possibility is surprising: Creative preservation can ‘systematically’ end through expansion. This eventuality clearly echoes the type of creative preservation that occurs in one systematic design process. Moreover, a clear repetition is possible: Sheafification can be repeated for several presheaves within one given (Cat, J), and topos theory demonstrates that, for a given site (Cat, J), the repetition will follow the same sheafification process, resulting in the same Cat extension.

This theoretical result can explain the interesting property of the ‘repeated creative preservation’ of systematic design engineering (Bender and Gericke Reference Bender and Gericke2021): One can assimilate engineering design knowledge to a Cat, and the engineering design process can be assimilated to a topology where specific parts are considered ‘knowns’ (keep the same functional referential, keep the same machine elements, rely on existing industrial machines etc.), and others are ‘unknowns’ (level to be reached on each functional requirement, choice of the conceptual models, detailed design of each component, etc.). Hence, engineering design can be viewed as a design within a given site (Cat, J); each new product to be designed on this knowledge base is a presheaf that must be made a sheaf on this site. Sheafification predicts that on a stable site, the engineering design process will always follow a similar design process (even if the presheaves are different), and the knowledge structure will be extended by new knowledge, but these additional extensions preserve the knowledge structure.

Second, in C-K/Topos, for a given Cat, several J (nondiscrete ones) can be built; hence, repetition can extend to every topology (which is not discrete). In this case, each sheafification will result in different extensions of the initial Cat. Compatibilities between these extensions are not guaranteed, but all these extensions share the same Cat.

This theoretical result can contribute to our understanding of design multiple ‘interventions’ on engineering systems (Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen, Vermaas, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022a): For a given engineering system, if one can extract a category of the rules to be preserved (Assumption 1), then a design intervention could appear as follows: (a) fixing the ‘limits’ that should remain ‘unchanged’ – this corresponds to fixing the topology; (b) designing the ‘unknown’ parts (to be changed) by using the Cat rules – this corresponds to designing on the chosen site (Cat, J), and this is related to a sheafification on (Cat, J) and (c) this process can be redone at several places, with the same Cat but with different ‘fixed known limits’ and ‘unknowns’ in the system, hence with different topologies (J1, J2, etc.). Each Jx-sheafification leads to a new Cat extension. Even if all extensions share the same Cat, there is a risk that they will not be compatible, which may lead to difficulties with the repetition of design interventions in engineering systems. Following the model, one could study the dynamics of repeated ‘interventions’ in engineering system design (such as ‘tipping point’ or ‘long accumulation of small innovations’ see Maier et al. Reference Maier, Oehmen, Vermaas, Maier, Oehmen and Vermaas2022c) as repeated sheafifications on a stable Cat leading to incompatibilities in the resulting expansions.

Third, of course, a designer can always design a new category Cat* related to Cat (e.g., that could contain Cat or, conversely, be strictly included in Cat) and use a new C-K/Topos process based on Cat*.

4.2. Main contribution: C-K/Topos to uncover the generativity of creative preservation

We have shown how C-K/Topos can help overcome critical fixations to better explore the rich generativity of creative preservation:

-

1. Beyond the trade-off, creative preservation can follow a variety of preservation strategies, which are uncovered, via C-K/Topos, when modeled as sites (Cat, J) constructed in the K-space and J-based concepts in the C-space (Result 1);

-

2. Beyond knowledge reuse and predefined preservation, creative preservation can include the design of preservation, which can be modeled, in C-K/Topos, as the design of the category Cat and the exploration of J-topologies (Result 2);

-

3. Beyond combinatorial generativity within a stable grammar, repeated creative preservation can have surprising dynamics, which C-K/Topos enables us to describe as the J-sheafification of multiple presheaves on multiple sites (Cat, J), obtained by varying J and Cat (Result 3).

One must emphasize the fact that these theoretical results are in line with empirical studies of original, high-performing ‘creative preservations’ already described in the literature. Let us quickly review some cases:

-

1. In the railroad case (Jibet et al. Reference Jibet, Le Masson, Weil, Chazelle and Laousse2023), research has shown that a strong design effort helps avoid overly costly repairs and facilitates the discovery that engineering rules could actually be compatible with highly creative solutions (hence successful creative preservation). Research (relying on a C-K/Topos-based analysis; Jibet Reference Jibet2025) has revealed that the success of the renovation is linked to a variety of preservation strategies, including ‘preserve the ballast and the sleepers and explore the rails’ – several other similar preservation strategies unfolded in the ‘creative renovation’ of local railroads (see Result 1). Empirical research has shown that ‘what has to be preserved’ is explored and designed during the design process (see Result 2); repetition of creative preservation requires complex coordination processes to ensure that all the ‘local’ creative preservations will be compatible (Result 3). These results also show that engineering rules can support creativity, perhaps to a point that goes beyond usual approaches in engineering design, insofar as this creativity is stimulated by the need to preserve the rules themselves (Bender and Gericke Reference Bender and Gericke2021). The organizational and managerial conditions of these results require further investigation, for which the C-K/Topos model provides solid analytical tools.

-

2. Harlé et al. (Reference Harlé, Hooge, Le Masson, Levillain, Weil, Bulin and Ménard2022) and Harlé (Reference Harlé2022) have shown how radical innovations can occur at the plant level in a situation where production rules must be strictly followed (workers cannot change the design of the aircraft they build!). The empirical investigations revealed that workers explored several creative preservation strategies (Result 1) and ultimately revisited what the ‘production rules’ are and mean, hence redesigning what has to be preserved and thereby rejuvenating the creation heritage of the plant (Result 2); specific organizations need to repeat creative preservation at different places and at different moments (Result 3). These results also show how production rules, usually used to ‘stop’ changes in production plants and confine design to engineering departments, can actually become leverage for creativity. Analysis with C-K/Topos enabled the identification and support of some of the complex managerial processes required for creative preservation at the plant level (Harlé et al. Reference Harlé, Le Masson, Weil, Bourlier and Veslin2023), paving the way for further research.

-

3. Taupin (Reference Taupin2023) and Taupin et al. (Reference Taupin, Barbier, Redheuil, Le Masson, Segrestin and Valibhay2024a, Reference Taupin, Le Masson and Segrestin2024b) have shown that the scale-up of the so-called ‘deep tech’ start-ups requires both innovation (technical breakthrough, business model evolution etc.) and the construction of a stable core of technical and business rules. The work uncovers the surprising complexity of these creative preservation strategies, far beyond the logic of ‘pivoting’ (creation without preservation) or pure duplication (preservation without creation) (Result 1), encompassing the management of the emergence and stabilization of a fixed, preserved set of design rules to design the creative heritage of the firm (Result 2), and the necessitating sophisticated management and leadership through which top managers organize the repetition of preservation to support the growth of the firm (Result 3).

-

4. Carvajal Pérez et al. Reference Carvajal Perez, Araud, Chaperon, Le Masson and Weil2018 and Reference Carvajal Pérez, Le Masson, Weil, Araud and Chaperon2020 have shown an extreme case of innovation for tradition in the design of luxury champagne, emphasizing that preservation does not (only) consist of fixing a set of ‘unchangeable’ building blocks but mostly consists of identifying ‘preserved’, constantly reopened, so-called ‘paradoxes’, that is, never-resolved tensions in the taste, aspects, and flavor of the wine (Result 1), these building blocks and paradoxes being ultimately the creation heritage of the firm (Result 2) that enables the division of design work (Result 3). It is possible to show that this type of ‘creation heritage’ works like a category and its topology (the paradoxes are the fixed points that leave degrees of freedom to create an original, new champagne vintage yearly that nevertheless corresponds to the luxury brandmark (Hatchuel et al. Reference Hatchuel, Le Masson, Weil and Carvajal-Perez2019). There is a deep link between the structure of the site (Cat, J) and the division of design work ranging from the cellar master (designing the yearly vintage juice) to the sommelier (creating food and wine pairings in the restaurant).

This paper also contributes to show how fundamental principles introduced by topos theory advance C-K design theory. Basically, in C-K theory, K is a free parameter; with topos theory one can inject a rich K structure adapted to design expansions and this helps to deepen key topics of C-K theory:

-

1. topos theory provides a rich language of interdependences and interfaces in complex systems, enabling to deepen both the impact of interdependences on design generativity and how design generativity can aim at creating new independences and dependences.

-

2. The definition of ‘objects’, its revision and related K-reordering is a key issue of C-K design theory – the relational approach of objects definition in topos theory enables C-K/topos to account for the complex articulation between preservation and changing identity of objects.

-

3. Topos theory enables to systematically identify topologies associated with a category and the related sheafifications, so that C-K/topos can systematically account for several creative preservation strategies. It also enables to figure out how a variety of loosely of even un-coordinated designers working on the same complex system will together redesign the system – a question highly relevant when it comes to transition design.

-

4. Topos theory offers powerful tools such as categories or topologies that appear as unique operators in a C-K process, combining K-structure, preservation, validation and expansions.

4.3. Future perspectives opened by C-K/Topos

This article contributes to the interplay between creativity issues and design theory: It shows how C-K/Topos uncovers the rich generativity of creative preservation beyond fixations.

From a design creativity perspective, we now expect that this C-K/Topos model can also lead to the development of methods, tools, organizations and collective processes that support collective creative design actions for contemporary societal issues in a variety of contexts, from manufacturing plants to engineering departments, from large companies to start-ups, and from well-trained design experts to lay citizen-designers. In particular, one can emphasize the fact that C-K/Topos is a highly promising approach in terms of software design support: Since topos theory is actually very computational (Caramello Reference Caramello2017), one could consider systematizing creative preservation via the following steps:

-

a) For a given set of (engineering) rules, generate (at least) one related category (see Spivak Reference Spivak2013; Breiner and Subrahmanian Reference Breiner and Subrahmanian2017).

-

b) Within this Cat, identify/explore the Grothendieck topologies (with computer aid).

-

c) Within the site (Cat, J), design the related sheafification – a topology being a specific structure on Cat where some parts are known and others are kept unknown; designing the related sheafification consists of designing all the missing rules to extend Cat in such a way that presheaves become J-sheaves in this extended Cat.

-

d) With such a model, one would investigate in more depth the variety of creative preservation and techniques to organize the process in a more official way.

From a design theory perspective, this article lays a foundation for the exploration of new models of design theory adapted to design intervention within complex sociotechnical systems, hence providing solid theoretical foundations to support works on systemic design, design for transitions and engineering system design.

It also lays a foundation for efforts to address other design situations involving creative preservation, such as artistic pieces that reinvent and reinterpret great masters. As an acknowledgment of our Japanese colleagues (who organized the International Symposium on Design Creativity in Fukuoka, where an early version of this work was presented), we illustrate in Figure 6 how C-K/Topos proposes an interpretation of Hiramatsu Reiji’s ‘creative preservation’ of Monet’s work: Based on the exhibition catalog (Koyama-Richard and Candil Reference Koyama-Richard and Candil2018), it appears that Hiramatsu Reiji aimed at revisiting Monet’s work from the perspective of traditional pre-Meiji painting (so-called Nihonga painting (see Appendix A9)), relying on knowledge of Monet’s painting and the Giverny site. According to art critics, it appears that Hiramatsu Reiji actually relies on the same category as Monet in K: “use a masterpiece from a foreign country to better understand light and movement in the art of one own’s culture, by studying white lilies on a pound at Giverny, France, at different seasons and daytime”. Hiramatsu Reiji does not break the category (this is done by other artists who are just ‘inspired’ by Monet without retaining a complex knowledge structure); he keeps the category (just inverting the countries: Monet used the Japanese art of his time to revisit Western painting, whereas Hiramatsu Reiji uses Monet’s Western painting to revisit Japanese painting), and he does not apply the category in a simple (discrete) way (which would consist of simply copying Monet with a Nihonga technique) but applies the category in a ‘dense’ way by revisiting complex notions such as light, vibrations, patterns, and transparency. We see how C-K/Topos might help analyze how artists use complex cognitive patterns in a logic of creative preservation (see also Tashi Reference Tashi2019).

Figure 6. Top: Hiramatsu Reiji Lilies at Giverny; bottom: Analyzing Hiramatsu Reiji’s creative preservation of Monet with C-K/Topos.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants in the International Symposium on Design Creativity (Fukuoka, Japan 2024) for their contributions to this article. The authors also would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the editors of the Design Science Journal for their very helpful and constructive comments.

Appendix: Technical notes

Appendix A1

Language note: We decided to keep the term ‘preservation’, although English-speaking colleagues have recently advised that the term ‘conservation’ might account for the richness and variety of ways to keep known things (including services, models, values and resources) during the design process more effectively. The reason for this decision is that our first publications in French on this notion used the French term ‘preservation’ (Le Masson and Weil Reference Le Masson and Weil2020; Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2021; Jibet Reference Jibet2025), and our first publications in English, which were perhaps victims of a Gallicism, used the term ‘preservation’ (Le Masson et al. Reference Le Masson, Hatchuel and Weil2023a; Verger et al. Reference Verger, Duymedjian, Wegener and Glăveanu2024; Lakemond and Holmberg Reference Lakemond and Holmberg2025).

Appendix A2

Of course, several trade-offs can be considered: Replace some old parts with new ones and keep the others— but these alternatives have been evaluated as too costly or invalid.

Appendix A3

Set theory raises some issues regarding the objects themselves. First, regarding mathematical objects, as explained by Prouté (Reference Prouté2007) – one of the leading topos theory scholars – in set theory, the exponential function (exp: R➔R) or the ring M2x2(Z/7Z) of the 2x2 matrices with coefficients in Z/7Z are both sets. Set theory also posits that if X and Y are sets, so is their intersection X∩Y. Thus, set theory allows us to write exp ∩ M2x2(Z/7Z), which is a nonsense object for any mathematician. Prouté uses this example to underline his point that “set theory is too lax” and requires a capacity to name and handle types. He also shows that topos theory is particularly suited to this role (even more so than type theory)

Appendix A4

More precisely, in mathematical technical terms, a topos comprises the contravariant functors from Cat to Set, and hence it can be denoted by SetCat_op (set to the power of Cat with contravariance, denoted by ‘op’). For further details on topos theory, see, for instance (Kostecki Reference Kostecki2011; Prouté Reference Prouté2016a; Caramello Reference Caramello2017; Rosiak Reference Rosiak2022)

Appendix A5

One definition of Grothendieck topology is given by (Stacks project authors 2025). A Grothendieck topology defined on a category Cat is a set Cov(Cat) of families of morphisms with fixed target {Ui→U}i∈I, known as coverings of Cat, satisfying the following axioms:

-

(1) If V→U is an isomorphism, then {V→U} ∈ Cov(Cat). («isomorphisms are coverings»);

-

(2) If {Ui→U}i∈I ∈ Cov(Cat), and for each i we have {Vij→Ui}j∈Ji ∈ Cov(Cat), then {Vij→U}i∈I,j∈Ji ∈ Cov(Cat) («the composition of coverings are coverings»);

-

(3) If {Ui→U}i∈I ∈ Cov(Cat) and V→U is a morphism of Cat, then Ui ×U V (fibered product) exists for all i, and {Ui ×U V → V}i∈I ∈ Cov(Cat). (Explanation: If U and V are two opens of a topological space X, then their fibered product U ×X V is the intersection U∩V. Further, the axiom relates to the fact that if (Ui)i∈I is a covering by opens of U, then (Ui∩V)i∈I is a covering by opens of U∩V).