Introduction

A review of progress in medicine and the life sciences throughout the 20th century concluded that practically all advances in bacteriology, aerobiology, virology, and genetic engineering had found their way into offensive military biological weapons (BW) programs (Dando, Reference Dando1999). Yet, leading life scientists in a key gathering taking place in Asilomar, California, in 1975, decided not to engage with the misuse potential of the latest of these advances in the field of recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology. Instead, they sought to continue with business as usual, i.e., not to have rDNA securitized, which is discussed in terms of its misuse potential in offensive BW programs. While they acknowledged the dual-use potential of rDNA in principle, they did not engage in addressing its potential security ramifications by taking steps to prevent the development of genetically modified biological warfare agents. (Cobb, Reference Cobb2025a,Reference Cobbb; Cohen, Reference Cohen2025). This sidelining of the dual-use potential of rDNA biotechnology by leading life scientists notwithstanding, ever since the 1970s have some life scientists, outside observers, and policy makers have expressed concern about the misuse potential of this and subsequent biotechnology and life science breakthroughs. Over time, such concerns have varied in strength and scope, and resulted in (calls for) a variety of governance responses with a view to preventing the misuse of dual-use biotechnology. In this paper, we will analyze dual-use concerns and proposed or enacted governance measures related to three cases involving U.S.-based virology research and concomitant securitization discourses. This selection is due to the leading role of U.S.-based or funded life science research, the openness of the political processes surrounding the governance of such research, and the standard-setting roles that U.S. discourses and governance measures often play internationally. The three cases are (1) the heightened misuse potential of life science research by terrorist groups leading to the 2004 Fink report of the U.S. National Academies as well as the subsequent 2007 Proposed Framework for the Oversight of Dual Use Life sciences Research issued by the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB, 2007), (2) two influenza gain-of-function (GOF)-experiments in the early 2010s (Herfst et al., Reference Herfst, Schrauwen, Linster, Chutinimitkul, deWit, Munster, Sorrell, Bestebroer, Burke, Smith, Rimmelzwaan, Osterhaus and Fouchier2012; Imai et al., Reference Imai, Watanabe, Hatta, Hatta, Das, Ozawa, Shinya, Zhong, Hanson, Katsura, Watanabe, Li, Kawakami, Yamada, Kiso, Suzuki, Maher and Kawaoka2012), which raised biosecurity concerns as they increased the transmissibility of the highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus in ferrets via aerosol transmission, and (3) more recent GOF research undertaken in the Wuhan Institute of Virology, seeking to predict influenza evolution, which some claim has resulted in a lab leak that caused the COVID-19 pandemic.

In principle, GOF research describes a practice “that refers to techniques used in research to alter the function of an organism in such a way that it is able to do more than it used to do, and to understand how this occurs in the environment” (American Society for Microbiology, 2025). While much of the research involving GOF-based research and development has useful applications, a small subset of GOF raises biosecurity concerns related to the misuse potential of benignly intended work. Particularly prone to such misuse is “research [that] involves experimentation that aims or is expected to (and/or, perhaps, actually does) increase the transmissibility and/or virulence of pathogens” (Selgelid, Reference Selgelid2016, p. 923). It is this subset of GOF that is the focus of our analysis. What ties the three cases together are the underlying breakthroughs in parts of the life sciences, especially in virology, as will be detailed in subsequent sections. All three cases have triggered at times intense discussions among scientific experts and—to a lesser degree—in the political sphere. Discussion related to the most recent case of coronavirus research in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has focused both on debating the origins of the pandemic (see Section “The securitization of GOF research in the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the origins of COVID-19” below) and on how to govern future GOF-research (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Baez and Rutland2021; Gillum, Reference Gillum2025; Giordano & Di Eullis, Reference Giordano and Di Eullis2025; Kosal, Reference Kosal2021). Although the conceptual toolbox of both Kosal and Albert et al. draws on elements of securitization and related theories, a systematic analysis of the three cases under a single analytical framework is, up to now, absent. This paper closes this gap in the literature through the application of an updated version of securitization theory.

Recent research in securitization theory distinguishes between “threatification” and “riskification” as two variations of the original conceptualization of securitization proposed in the late 1990s by Barry Buzan and other members of the so-called Copenhagen School (Corry, Reference Corry2012; Diez et al., Reference Diez, von Lucke and Wellmann2016). For each of the three cases, we identify securitizing actors and discourses, and analyze proposed governance measures and their acceptance by the intended target audiences. Each of the three episodes of life sciences research and development thus analyzed concludes with an assessment of the extent to which securitization moves were successful and which facilitating conditions (see the section on securitization theory below) contributed to the outcome. By tracing the evolution of different securitization attempts over the past 25 years, the paper demonstrates that the distinction between riskification and threatification provides a useful analytical tool to better understand varying attempts to characterize and govern gain-of-function research as dual-use research of concern in the United States. To this end, the next section of the paper introduces the concepts of securitization, threatification, and riskification. It also provides some background information on understanding and manipulating viruses. Each of the subsequent three sections presents one of the three above-mentioned cases of dual-use concerns related to advances in the life sciences in general and virology in particular. In the concluding section, we summarize the argument and discuss some of the recently advanced proposals for the governance of future GOF research in light of the distinction between riskification and threatification.

Central concepts in securitization and virology

Securitization theory and its application to the life sciences/virology

Securitization theory was introduced into the academic discourse on international security issues in the second half of the 1990s by Barry Buzan and his colleagues from what has been labelled the Copenhagen School (McSweeney, Reference McSweeney1996). They sought to broaden the concept of security beyond the traditional military focus of security studies to include political, economic, societal, and environmental sectors, and to recognize actors beyond just the state (Buzan et al., Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998; Wæver, Reference Wæver and Lipschutz1995). In addition to broadening the scope of what counts as a security issue, securitization theory is based on the assumption that security is not an objective condition but a social construction, where securitization refers to a process during which a securitizing actor uses a speech act to identify an existential threat to a referent object—which could be an individual, a state, or the planet as a whole. The securitizing move then has to be accepted by a relevant audience, which, in turn, enables the securitizing actor to adopt extraordinary measures that go beyond normal politics as the final step in the securitization process. Thus, the key concepts in the securitization process are the securitizing actor, the threatened referent object, and the audience, whose buy-in is required. Since its original formulation, securitization theory has been applied to a wide range of issue areas, including migration (Ceyhan & Tsoukala, Reference Ceyhan and Tsoukala2002; Huysmans, Reference Huysmans2000), health (Maclean, Reference Maclean2008; McInnes & Rushton, Reference McInnes and Rushton2013), climate change (Albert, Reference Albert2023; Diez et al., Reference Diez, von Lucke and Wellmann2016), and cyber security (Bendrath et al., Reference Bendrath, Eriksson, Giacomello, Eriksson and Giacomello2007). The concept of securitization has also been the subject of discussion and refinement, with some arguing that practices, context, and power relations in the securitization process deserve greater attention (Balzacq, Reference Balzacq2005).

As Thomas Diez, Franziskus von Lucke, and Zehra Wellmann (Diez et al., Reference Diez, von Lucke and Wellmann2016) have noted, several scholars have criticized the strict dichotomy in securitization theory between normal politics and security. To accommodate the increasing salience of risk as an emerging concept, and to take account of the empirical observation that securitizing moves sometimes result in less than the dramatic measures that the theory would expect, Diez and colleagues “argue in favor of a re-conceptualization of politics, security and risk, which sees risk as a sub-category of security and relabels the Copenhagen School’s [original] concept of securitization as “threatification,” and thus only as a sub-set of different forms of securitization” (Diez et al., Reference Diez, von Lucke and Wellmann2016, p. 14). With securitization as the umbrella term, threatification refers to immediate danger, while riskification, which is the second form of securitization, is used to capture dangers that are less immediate and are regarded as more diffuse or weaker. Both threatification and riskification can be reversed by de-securitization, which moves an issue back into the sphere of normal politics. Due to the processes of threatification, riskification, and de-securitization, issue characterizations are not fixed.

This flexibility allows for different outcomes of securitization moves in relation to the three cases of virology research securitization, which stands in contrast to the assessment by Albert et al., who assert that infectious disease “clearly represents a threat across the theoretical spectrum” (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Baez and Rutland2021, p. 84). Albert et al. focus in particular on “human security theory and biosecurity. In both of these areas, COVID-19 poses an existential threat and should be taken seriously within national and international security” (Albert et al., Reference Albert, Baez and Rutland2021, p. 85). Similar to our approach, Kosal argues that the response to COVID-19 in the United States represents a significant shift in policy through the “conceptual amalgamation of emerging infectious disease and public health with biodefense and biosecurity” (Kosal, Reference Kosal2021, p. 83). However, while she is concerned that biological weapons might mistakenly be treated as “a lesser included set of emerging infectious diseases” (Kosal, Reference Kosal2021, p. 88), our goal is to use the differentiation between riskification and threatification to better explain the policy shift in response to the pandemic.

Given the focus of this paper on the governance of life science research in the United States, we will focus on the state level of securitization discourses in the three cases analyzed in subsequent sections, seeking to draw out riskification–threatification distinctions across the cases. Our discussion will be based on qualitative document analysis of published (or publicly available) texts produced by securitizing actors (Bowen, Reference Bowen2009; Morgan, Reference Morgan2022).

Turning to the actors pursuing securitization processes, these are more likely to succeed the more they speak from a position of authority. Yet such authority does not necessarily have to be tied to an official position in government. Instead, authority can also flow from prestige, status, or socialization. In light of the issue area at the center of our analysis, e.g., the dual use aspects of the life sciences and more specifically virology, the life science community, or its representatives, e.g., in learned societies or government-appointed advisory bodies, are clearly relevant actors that need to be considered. As Trine Villumsen Berling has pointed out, “scientific arguments and ‘facts’ are at work in at least three distinct mechanisms within and around securitization” (Villumsen Berling, Reference Villumsen Berling2011, 385). These are related to the objectivation of an issue that makes its securitization practically impossible, the increasing authority of an actor due to their membership in the scientific community, and the mobilization of scientific facts in support of a position taken. Thus, life scientists are not merely part of the target audience as recipients of securitizing moves, but, as will be demonstrated throughout the cases discussed, can themselves be securitizing or de-securitizing actors in the discourse on life science research and its governance. The cases will also demonstrate that life scientists in the United States over the past 25 years have succeeded until recently to use their positions of authority to limit the degree of securitization of their work whenever faced with dual-use aspects of new and emerging technologies.

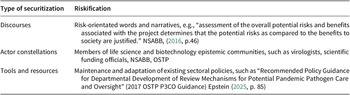

We follow Englund and Barquet’s (Reference Englund and Barquet2023) approach for operationalizing securitization by distinguishing between discourses, actor constellations, and the context of securitization in the form of tools and resources. They conceptualize “discourses […] as the words, narratives and scripts used to describe” (Englund & Barquet, Reference Englund and Barquet2023, p. 3) the issue area in question and its governance. Actor constellations are relevant for determining “who is responsible, who is setting the agenda, and who, if at all, is granted exceptional power? Tools and resources consider the policies, strategies, human and financial resources, and technologies mobilized to address” the issue of concern (Englund & Barquet, Reference Englund and Barquet2023, p. 3). Finally, Englund and Barquet point out the historical context in which securitization moves are located, in so far as “pre-existing actor constellations, organization of government, collective memory, and norms and ideas shape securitizing discourses” (Englund & Barquet, Reference Englund and Barquet2023, p. 3). In order to facilitate comparison of the three cases, we will provide the context in which the securitization moves have taken place, before discussing the relevant actors and their securitization attempts, and the effects these had on dual-use governance measures. The most relevant aspects will be summarized in a table at the end of each case study.

Given this historical embeddedness of securitization moves, the following section will provide a brief overview of the evolution of virology, in particular its combination with genetic engineering, and how advances in the latter have led this sub-field of the life sciences to emerge on the radar screens of experts concerned with the impact that advances in the life sciences, virology in particular, could have on the prohibition of biological and toxin weapons.

Understanding and manipulating viruses: some history

Viruses are too small to be seen by the naked eye. They vary in size from just below the size of the smallest bacteria to just above the size of some large chemical molecules. Given their small size, it is not surprising that viruses were only discovered at the end of the 19th century when it became possible to separate them from already known bacteria in a liquid by sieving it through a very small mesh that caught bacteria but allowed viruses to pass. Moreover, visualizing the structure of viruses was only possible when electron microscopes became available from the 1930s onwards. Therefore, it is not surprising that our understanding of viruses developed later than our understanding of bacteria (Burrell et al., Reference Burrell, Howard, Murphy, Burrell, Howard and Murphy2017). Genetic engineering, the technology that arose in the 1970s, allows the manipulation of the genetic material of organisms by splitting the DNA and joining it together with different DNA to make new recombinant DNA, thereby heralding the beginning of modern gain-of-function research.

Some 40 years ago, Erhard Geissler (Reference Geissler and Geissler1986a) divided the history of biological and toxin weapons (BW/TW) into three eras: the classical stage (pre-WWII), limited by lack of knowledge; the second stage (post-WWII), enhanced by microbial genetics; and the third stage, beginning with genetic engineering, which coincided with the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention. The introduction of genetic engineering immediately raised suspicions that it could lead to the creation of fundamentally new BW/TW agents. The issue of the impact of advances in genetic engineering and molecular biology on the potential development of novel biological and toxin weapons was therefore clearly identified as these new capabilities emerged.

By comparing open literature from 1969 and 1983, Geissler demonstrated a major shift in military interest concerning potential biological warfare agents: in 1969, most agents were bacteria and fungi, but by 1983, “viruses had become the majority of such agents (19 out of 22)” (Geissler, Reference Geissler and Geissler1986b, p. 22). He attributed this switch of military interest from bacteria and fungi to viruses to several reasons, such as the more dangerous nature and difficulty in diagnosing and treating viral diseases, and the advent of genetic engineering, making handling of dangerous viruses easier. In addition, the capabilities of genetic engineering advanced at a rapid rate over the following decades.

During the 1990s, DNA sequencing and synthesis became more and more possible through automatic systems and the Human Genome Project was completed in 2003. At this stage, it became clear that an engineering approach was the best way forward, and synthetic biological parts with standardized features were designed and developed. So, by 2008, it was possible to assemble the first synthetic bacterial genome. This genome was of an existing organism, but the experiment opened the way to the design of novel organisms in the future. Then, most importantly, in 2012, the CRISPR-Cas9 precise, cheap, and easy-to-use genome editing technique was discovered, and its use spread widely and very quickly. During the following years, artificial intelligence was used to design standard biological parts, and in 2020, synthetic biologists used such methods to produce xenobots—self-replicating synthetic organisms.

Securitization of virology in the context of bioterrorism concerns: The 2004 Fink Committee report and subsequent NSABB guidance

The second half of the 1990s saw the convergence of two security concerns. On the one hand, experts and policymakers were concerned that post-Soviet weapons of mass destruction (WMD) related expertise and materials might proliferate to countries or sub-state actors of concern. On the other hand, the salience of terrorism with WMD increased significantly after the 1995 Tokyo Sarin gas attack and the Oklahoma City bombings (Drell et al., Reference Drell, Sofaer and Wilson1999). At the end of the Clinton administration and certainly following the anthrax letters sent through the U.S. mail in the fall of 2001 (U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2008), bioterrorism and the potential misuse of advances in dual-use life science research in this context had moved center stage in most expert and official security assessments (Wright, Reference Wright2006).

Thus, advances in the life sciences, including in virology, during this period occurred in a context of heightened security concerns. Some virology experiments had caused widespread dual-use concerns to arise and thus to be hotly debated within parts of the life science community. Against this background, the U.S. National Academies in 2004 emerged as a securitizing actor when it established a new Committee on “Research Standards and Practices to Prevent the Destructive Application of Biotechnology,” chaired by Professor Gerald R. Fink. The committee included 17 United States experts, mostly from biotechnology and the life sciences, but also the law, military, and industrial affairs. The Fink Committee’s mandate was to find ways to reduce threats from biological warfare and bioterrorism while simultaneously ensuring the advancement of biotechnology for national health. This is difficult because almost all technology used for health benefits can be misused by hostile actors, and the materials needed for bioterrorism are often globally available and easy to acquire. Thus, the Fink Committee’s mandate clearly prioritized safeguarding the progress of biotechnology over minimizing its misuse. That this was a new issue that needed to be addressed was clear from the Preface to the report, which stated that “this is the first to deal specifically with national security and the life sciences” (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, pp. vii-viii).

The Committee was acutely aware of the dual-use dilemma and, in this context, quotes a former chairman of the National Intelligence Council’s view that the ongoing revolution in science and technology (including genomic profiling and genetic modification) would intensify the dual-use problem. While this technology offered great opportunities for scientists to enhance human life, it simultaneously granted terrorists and “other evildoers” a potent capacity to cause destruction (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 24).

During its subsequent elaboration of potentially problematic dual-use research, the Fink-Committee focused exclusively on recent advances in virology. It identified several “contentious research” experiments with dual-use potential that garnered attention from scientists, the media, defense experts, and policy analysts, specifically naming the Australian mousepox experiment, the synthesis of the poliovirus genome, and the comparison of immune responses to vaccinia and smallpox viruses.

The mousepox experiment was carried out by Australian scientists seeking means of dealing with mouse plague outbreaks (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Ramsay, Christensen, Beaton, Hall and Ramshaw2001). In the course of their work, the researchers, to their surprise, produced a virus lethal even to mice vaccinated against the original virus. Given that the paper was published with full information on the materials and methods in a key journal, this raised concerns that the same effect could be produced in other pox viruses, such as smallpox, by those with malign intent. However, the 2004 Fink-Committee took a different view, stating that:

since the ability of immunomodulatory factors to increase the virulence of this virus could have been predicted and the means to make such a virus were readily available, it was important to publicize that this strategy could overcome vaccination because it alerted the scientific community to such a possibility occurring either intentionally or spontaneously. (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 27).

The second example was a report of the reconstruction of poliovirus from synthesized chemicals that were linked together and then transfected into cells (Cello et al., Reference Cello, Paul and Wimmer2002). As the Fink-Committee report noted, the media coverage of the synthetic poliovirus experiment heightened public anxiety about bioterrorism. Reports implied that the experiment offered a “recipe” allowing terrorists to synthesize any virus merely by buying chemicals commercially (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 28). However, the Fink Committee suggested that what had been done was not new or unexpected by informed scientists, as this possibility had been known since 1981. Moreover, the virus produced was weak and the method used was very laborious.

The third example concerned a comparison of the immune response to a virulence gene from vaccinia virus and smallpox (variola) (Rosengard et al., Reference Rosengard, Liu, Nie and Jimenez2002). Vaccinia is used to vaccinate against smallpox and causes no disease in immunocompetent humans, whereas smallpox has a 30–40% mortality rate. Both viruses have an inhibitor of the human immune response—VCP in vaccinia and SPICE in smallpox (variola). According to the study, researchers synthesizing the variola SPICE gene found that it was far more active (nearly a hundredfold) than the VCP inhibitor found in vaccinia, specifically targeting the human immune system’s complement. Rosengard et al hypothesized that this difference in immune evasion might account for the greater virulence of smallpox and why it primarily affects humans. Again, while it might be argued that this was a serious dual-use security issue, the Fink Committee had a different view. It argued instead that:

publication of the article alerted the community of scientists to this mechanism for virulence. This information should stimulate scientists in both the public and private sectors to identify compounds or immunization procedures that disable SPICE… (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 29).

During six meetings between April 2002 and January 2003, the Committee was briefed by high-level officials from the National Institutes of Health, the Executive Office of the U.S. President and by a range of government and non-government experts. It also reviewed information available in the open literature and new material presented by groups of almost entirely United States experts on a series of topics. Thus, the discourse in the context of the Fink Committee deliberations showed a clear focus on the national dimension of the issues, and was led by scientific experts stemming from the life sciences community and related government bureaucracies. Notwithstanding the Committee’s mandate, which was formulated in terms of minimizing threats, the prevailing perspective amongst the committee members stood in the tradition of the first Asilomar conference. That prevailing perspective was based on the “objectivation” (Villumsen Berling, Reference Villumsen Berling2011) of rDNA research, asserting that the activities of civil scientists had little to do with biological weapons dangers and hence should not be subjected to any securitization-based restrictions. In other words, the framing of the Committee’s mandate with the emphasis on not hindering developments in biotechnology and the actor constellation within it, which was dominated by diverse members of the United States life science elite, resulted in a discourse that favored benevolent interpretations of contentious dual-use experiments in virology. The broader focus on biotechnology overall also lent itself to viewing the virology experiments discussed above as being part of a broader, more diffuse development that required an equally diffuse and broad-based risk governance approach.

Setting the stage for its recommendations, the Fink–Committee also considered the complex and evolving overall regulatory system for pathogens and toxins in the United States, but from our point of view, the key issue is how recombinant DNA (rDNA) research—the term for genetic engineering at that time—was regulated. The system was developed with a focus on biosafety following the Asilomar conference in the mid-1970s. Accordingly, any institution receiving NIH funding for recombinant DNA (rDNA) research was required to form an Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC), which would act as the foundation for institutional oversight of rDNA work. “On behalf of the institution, IBCs review rDNA research projects for compliance with the NIH Guidelines” (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 45).

The Fink Committee proposed a review system spanning multiple stages to ensure dual-use biotechnology research with bioterrorism potential receives responsible oversight. This system relies fundamentally on a combination of voluntary self-governance by scientists and the expansion of the existing regulatory process built around the NIH Guidelines for rDNA Molecules.

The second recommendation of the report specifies the seven classes of experiments to which the review system should apply, focusing on experiments involving rDNA with increased misuse potential. The seven types of experiment of concern are those that would defeat vaccines; confer drug resistance; enhance virulence; increase transmissibility; change host range; allow evasion of detection; or “enable the weaponization of a biological agent or toxin” (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 5).

Additionally, the Committee recommended a further self-regulation system to apply at the publication stage, putting the responsibility on science publishers and those involved in the academic peer-review process to decide about the publication of research results in light of the national security risk they might pose.

There were concerns at the time that few civil life science researchers would have the knowledge to make the judgments required. In order to address the knowledge gap in the life science community, the Fink Committee report recommended at the very outset that “national and international professional societies and related organizations and institutions create programs to educate scientists about the nature of the dual use dilemma in biotechnology and their responsibilities to mitigate its risks” (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, p. 4). As we now know, this recommendation has still not been carried out and the life science community, even in the United States, remains without systematic education about dual-use and biosecurity in general (Greene et al., Reference Greene, Relman and Palmer2025). Therefore, in addition to the lack of urgency indicated by the dual-use issue being seen as a risk rather than a threat, the facilitating conditions for making an informed decision on whether or not some form of securitization was warranted were absent, as the life science community in general lacked the knowledge necessary to engage effectively with the proposed policy for dealing with the dual-use dilemma.

In order to at least partially address this issue, the Fink-Committee also recommended that “the Department of Health and Human Services create a National Science Advisory Board for Biodefense (NSABB) to provide advice, guidance, and leadership for the [envisaged] system of review and oversight” (U.S. National Research Council, 2004, 9). This new actor in the life sciences securitization discourse was subsequently established and in 2007 published its “Proposed Framework for the Oversight of Dual Use Life Sciences Research” (NSABB, 2007). The framework was based on 12 guiding principles, the first of which stipulated that in such a system “the ‘default’ position should be the unfettered progress and communication of science. Any decision to do otherwise should be undertaken very carefully.” (NSABB, 2007, p. 7). The decision-making process at the heart of the envisaged oversight system for addressing potential dual-use issues related to life science research should be based on seven key features ranging from the promulgation of federal guidelines to “local evaluation and review of research for dual use potential” (NSABB, 2007, pp. 8–9). In this multi-layered system, the initial dual-use assessment was to be performed by the principal investigator, who was expected to be aware of potential dual-use issues of their research and appropriately trained in order to be able to perform such assessments. Other features of the proposed oversight system were its formalization into policies and guidelines by the U.S. Federal Government on the one hand (see the section below), and on the other hand, the risk assessment and risk management to be undertaken at the local level. Both of these features provide further evidence for the weak riskification approach proposed by the NSABB, which did not see the need to propose any exceptional measures for addressing the dual use problems presented by research in the life sciences, including virology. Table 1 below summarizes key elements of this case study.

Table 1. Securitization in the Fink Committee Report and NSABB Framework

The securitization of influenza GOF-experiments from the early 2010s to the pandemic period

In the early 2010s, two GOF-experiments with funding from the U.S. National Institutes of Health sought to increase the transmissibility of the highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus in mammals. Both teams of researchers succeeded in their efforts and the research results, prior to publication in highly regarded academic journals, were reviewed by a committee formed by the NSABB. Although this committee initially recommended publication of the two articles after redacting certain parts that would lend themselves to be directly misused, it subsequently changed its recommendation, “voting unanimously to recommend full publication of an updated version of one of the articles and voting 12–6 to recommend full publication of a revised version of the other” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 80). Although the articles were subsequently published by Nature (Imai et al., Reference Imai, Watanabe, Hatta, Hatta, Das, Ozawa, Shinya, Zhong, Hanson, Katsura, Watanabe, Li, Kawakami, Yamada, Kiso, Suzuki, Maher and Kawaoka2012) and Science (Herfst et al., Reference Herfst, Schrauwen, Linster, Chutinimitkul, deWit, Munster, Sorrell, Bestebroer, Burke, Smith, Rimmelzwaan, Osterhaus and Fouchier2012), respectively, the virologists involved also declared a voluntary moratorium on additional GOF research, which lasted for most of 2012 (Fouchier et al., Reference Fouchier, García-Sastre and Kawaoka2013).

This episode about the publication of two highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza virus triggered a securitization discourse that involved a number of different actors, ranging from the virologists and public health experts themselves—who generally advocated for limited or no securitization—to the U.S. Congress and different parts of the U.S. government, including advisory bodies such as the NSABB, and culminated in the May 2024 U.S. Policy for Oversight of Dual-Use Research of Concern and Pathogens with Enhanced Pandemic Potential, as well as a corresponding implementation guidance (Executive Office of the President, 2024a,b).

During the already mentioned period of the GOF moratorium, the U.S. Government issued in March 2012 a new Policy for Oversight of Life Sciences Dual-Use Research of Concern (US Government, 2012). This policy was largely based on the 2007 NSABB report (mentioned above). It thus followed a weak GOF-related riskification approach, which was built around research with 15 problematic pathogens or toxins, of which highly pathogenic H5N1 was one, alongside others whose misuse would most likely result in less severe consequences (than a H5N1-induced pandemic). Following a set of activities by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) throughout 2012, in early 2013, HHS issued a framework to guide funding decisions for research with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013). Of the seven principles or mandatory criteria for funding such research, three are expressly related to a risk management approach, and as such continue the type of riskification predominant in the governance of GOF research, or, in this particular instance, the funding of such research. The three criteria in question address (the absence of) feasible alternative methods that would allow obtaining the same results as GOF experiments, but with less risk, and require that biosafety and biosecurity risks will be sufficiently addressed. Also, in line with a riskification approach is the first of the seven principles, according to which “Such a virus could be produced through natural evolutionary processes” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2013, p. 5). As Epstein has pointed out, this first principle “is the most important” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 82). He elaborates that.

It might be called the “No Blue Sky” principle, since in effect it states that pathogens should not be constructed if they have been dreamed up “out of the blue sky”—in other words, if it would be extremely surprising for them to be the source of a future disease outbreak. Under such circumstances, research with such pathogens would pose considerable risk, given the possibility that they might escape confinement and initiate a pandemic, yet that research would have little benefit, since the disease that the research would be intended to counter would be very unlikely to arise otherwise. (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 82).

The context of the GOF-debate changed in 2014 when a number of biosafety lapses occurred at U.S. government funded laboratories.

In June, dozens of employees at a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention laboratory had been potentially exposed to anthrax. Then, on July 1, six vials of the virus that causes smallpox were discovered in an unsecured storage room on the NIH campus. Soon after that, news broke that the CDC had accidentally shipped out a dangerous flu virus. These incidents “raise serious and troubling questions,” said the then-CDC director at a July 11 press conference (Talpos, Reference Talpos2024).

This resulted in an August 2014 White House memorandum calling for a biosafety and biosecurity review and declaring a funding pause on selected GOF experiments. The funding pause explicitly prohibited new U.S. government funding for GOF projects anticipated to increase the pathogenicity or respiratory transmissibility of influenza, MERS, or SARS viruses in mammals. However, the pause did not cover testing or characterization of natural viruses, “unless the tests are reasonably anticipated to increase transmissibility and/or pathogenicity” (U.S. Government, 2014, p. 2).

The goal of the evaluation was to “determine which types of studies should go forward and under what conditions” (U.S. Government, 2014, p. 2). In principle, the U.S. government was not excluding the possibility that some types of experiments should not go forward at all, thereby indicating that it would potentially consider more drastic securitization measures. The deliberative process thus triggered included a specific charge to NSABB, which held a meeting on 22 October to discuss relevant issues (Lurie, Reference Lurie2014). The meeting heard several presentations by both supporters and critics of GOF research. Among the latter, Arturo Casadevall argued by reference to a paper he had co-authored that “this finding is of great value to humanity, because it suggested that a human H5N1 pandemic might be able to occur if and when similar mutations occurred spontaneously” (Casadevall & Imperiale, Reference Casadevall and Imperiale2014, p. 2). In this paper, the authors also recall the earlier NSABB discussion of the original H5N1 transmissibility papers. They note that the NSABB discussions initially centered on biosecurity (preventing deliberate misuse), as was their mandate. However, the focus gradually shifted to biosafety (preventing accidental release). This shift occurred because assessing biosecurity requires calculating the risk of intentional nefarious acts, “and such information is simply not always available” (Casadevall & Imperiale, Reference Casadevall and Imperiale2014, p. 2).

In other words, the NSABB, in spite of the mandate given to it in 2012, opted for a review along the lines of biosafety risk–benefit calculations instead of performing a biosecurity review. The same pattern can be observed in the 2014 GOF discourse at the NSABB. Here, one of the more critical voices, also by reference to published work, elaborated on the risks, not the potential threats posed by GOF research relative to alternative methods (Lipsitch & Galvani, Reference Lipsitch and Galvani2014). For the influenza GOF studies of concern, they expected a

rigorous, quantitative, impartial risk–benefit assessment [to] show that the risks are unjustifiable [and that] Alternative approaches would not only be safer but would also be more effective at improving surveillance and vaccine design, the two purported benefits of gain-of-function experiments to create novel, mammalian-transmissible influenza strains (Lipsitch & Galvani, Reference Lipsitch and Galvani2014, p. 2).

In 2015 and 2016, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine held two workshops to discuss the governance of GOF research, which in turn informed the 2016 NSABB recommendations for evaluation and oversight of proposed GOF research (NSABB, 2016). These recommendations remain firmly committed to a riskification approach, with portions of the document dedicated to analyzing and interpreting risks and benefits of GOF research, as well as devising strategies and frameworks for risk evaluation and management. In the process of its deliberations, the NSABB focused on GOF research of concern (GOFROC). As Epstein has noted, this characterization relied exclusively on a risk assessment that had moved away from previous list-based approaches and “depended on the properties of the pathogen that was to be generated in the course of the research” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 84).

As detailed in Epstein’s account, this general approach continued to be elaborated and broadened through to the pandemic period with the NSABB recommendations in turn informing the January 2017 Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight (P3CO) Guidance and December 2017 HHS P3CO Framework, as well as the May 2024 OSTP DURC/PEPP Policy, the latter of which was scheduled to come into effect in May 2025. In summary, then, this second case demonstrates a similar, or indeed weaker, riskification to the first case as illustrated in the table below.

However, Epstein’s review also makes two points that were clearly of concern to him. First, in the final iteration of the policy, there was an important omission: “The biggest surprise in the PEPP treatment within the 2024 OSTP DURC/PEPP policy is the deletion of the ‘No Blue Sky’ principle from the list of principles that PEPP research must satisfy” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 91). This, of course, raises critical questions, such as the lack of the principle allowing the researcher to argue that the knowledge gained from the experiment might be so beneficial in a future pandemic that it is worth the risk of creating one. As Epstein comments: “Such a justification obviates the entire rationale for review, since it assumes that the unquantifiable value of fundamental research justifies any amount of societal or planetary risk (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 91).” This significantly shifts the risk–reward calculation for any dual-use research and well illustrates the possibility of reversals of securitization processes, leading, in this case to a weaker riskification of PEPP research.

Secondly, Epstein points out that “To date, only four research projects have been put through these oversight frameworks, a surprising result that is inconsistent with survey data collected from biosafety professionals about how much PEPP research is currently underway” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 95). This clearly raises questions such as whether the scientists involved in the development and oversight of such experiments are able to properly assess the security implications—regardless of whether they would characterize these as risks or threats—of what they are doing. Table 2 below summarizes key elements of this case study.

Table 2. Securitization of influenza GOF-experiments from the early 2010s to the pandemic period

However, after the pandemic in 2022, a change of direction became visible with the Consolidated Appropriations Act that was passed by the U.S. Congress. This had a “subsection titled the ‘Prepare for and respond to Existing Viruses, Emerging Threats and Pandemics (PREVENT) Pandemics Act.’” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 89), and whilst restricted to federally funded research “within that domain, it authorized the OSTP Director to issue a government-wide policy that is binding on internal and external recipients of Federal Funding.” (Epstein, Reference Epstein2025, p. 90). The PREVENT Pandemics Act also created a new institutional actor by establishing the Office of Pandemic Preparedness and Response within the Executive Office of the U.S. President. It is thus evident that new actors—elected politicians—had developed an interest in this issue and sought its continuous monitoring and coordination at the highest level of government. This, as we shall see, also opened up new avenues of securitization of GOF research.

The securitization of GOF research in the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the origins of COVID-19

Early on during the pandemic, a paper published in Nature Medicine concluded unequivocally that the SARS-CoV-2 virus was not created in a laboratory or intentionally engineered (Andersen et al., Reference Andersen, Rambaut, Lipkin, Holmes and Garry2020). The paper then went on to discuss various ways in which this virus—the cause of the pandemic—could have arisen naturally. The United States was involved because, although the research was carried out in China, it was financed by the United States and therefore subject to its regulation.

Thus, at the start of the pandemic, the possibility of a laboratory leak being the origin of the pandemic was largely ignored, and those who worried about that possibility were widely considered to be misguided conspiracy theorists. We think that there is not enough publicly available information yet to decide between these two different views of either a natural origin of the virus or a laboratory leak. In the ensuing years, however, determined work by a wide range of qualified scientists called that early exclusion of a natural outbreak being the cause of the pandemic into considerable doubt. The ensuing extensive debate has been well described in some detail (Mills, Reference Mills2025), but here we focus on one particular example where the audience for the securitization moves performed by some scientists was the U.S. Senate and their suggested policy was to reject self-regulation by the life science community and replace it with legal oversight. Such more exceptional measures had already gained some traction among decision makers in the U.S. Congress. Accordingly, some politicians with an interest in GOF-issues had emerged as securitizing actors themselves, perceiving GOF-research as more of a direct threat than a diffuse risk that could be left to life scientists’ self-regulation (Paul, Reference Paul2024).

So, in June 2024, a Hearing on Origins of COVID-19: An Examination of Available Evidence was held in the United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs. Of course, the Senate took evidence in support of a range of views (see Garry, Reference Garry2024; Koblentz, Reference Koblentz2024), but here we concentrate on the evidence presented against the natural origin hypothesis, which at the outset of the pandemic had quickly developed into the official narrative. Two presentations during that Hearing by scientists detailed the evidence that they thought supported the view that the pandemic resulted from a laboratory leak of the dangerous pathogen. The first presentation was by Professor Richard Ebright of Rutgers University. He concluded that the weight of evidence suggests COVID-19 did not have a natural origin, but rather originated from a “human origin”—specifically, that the SARS-CoV-2 virus “entered humans through a research-related incident” (Ebright, Reference Ebright2024, p. 2).

His evidence was set out in 11 sections and was supported by 127 references and other additional information. In the first section of his evidence Ebright noted that Wuhan, where SARS-CoV-2 emerged in late 2019, is located 800 miles away from the nearest bat colonies hosting related coronaviruses (in Yunnan province) and is outside the typical flight range of those bats. This geographical distance makes a natural origin less likely. He also noted that Wuhan was the site of the world’s largest bat SARS-related coronavirus research program in 2019. Furthermore, laboratories in Wuhan had previously been identified by experts in 2015 and 2017 as conducting or planning research that carried an “unacceptably high risk” of a lab accident capable of causing a pandemic (Ebright, Reference Ebright2024, p. 4). In his view, this match between the place of emergence of the pandemic virus and the global center for high-risk research on bat-related coronaviruses again supported the possibility that the pandemic resulted from a laboratory-related incident.

In addition, Ebright’s testimony reviews worrying details of the type of work being done in Wuhan and its U.S. funding, the inadequate biosafety arrangements under which the work was carried out, and the genomic sequence of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and its properties. A significant part of Ebright’s testimony addresses the lack of evidence for a natural origin of the pandemic virus, concluding that:

No--zero--sound evidence has been presented that SARS-CoV-2 has a natural origin. No natural reservoir host has been identified, no natural intermediate host has been identified, suggestions that SARS-CoV-2 first entered humans at the Huanan Seafood Market in Wuhan are false, and papers widely cited as providing evidence for natural origin are unsound (Ebright, Reference Ebright2024, p. 15).

Ebright is also particularly critical of the oversight given by the funders for this work. The research in China was funded indirectly by the United States Institutes of Health (NIH) through a U.S. organization. As noted by Ebright “In 2017–2018, with NIH funding, the Wuhan Institute of Virology constructed novel ‘chimeric’ (hybrid) SARS-like coronaviruses … and obtain[ed] at least one novel chimeric virus” with massively enhanced growth rates and increased lethality. These research results were obtained despite the fact that the NIH had previously amended the terms of the grant “stating that construction of a virus having a 10x or higher enhancement of viral growth would necessitate stopping research and immediately notifying the NIH” (Ebright, Reference Ebright2024, p. 6). These guidelines were not followed and only later was the funding halted.

The second presentation was by Quay (Reference Quay2024) a very experienced scientist and medical practitioner. He focused on demonstrating why the virus could not have originated as a natural outbreak in the Wuhan Market. One particular aspect of interest here concerns the disruption of the immune defense system. As Quay pointed out, one of the unexpected characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was that it was often asymptomatic and this was important in the initial spread of the infection. He explained that an early product of the virus was a protein called ORF8. This, in part, blocks the production of interferon, which slows down infection and causes the familiar signs of infection—fever, sweating, and so on. ORF8 later on in the infection also interferes with the functions of the adaptive immune system. Quay testified that before 2019, the WIV performed extensive, unpublished research (found only in untranslated master theses) on optimizing the ORF8 gene, which included creating a synthetic biology pathway to manipulate the protein and insert it into viruses. He categorized this secret ORF8 research as “a classic ‘dual use’ research project” (Quay, Reference Quay2024, p. 19). Finding this, as well as several additional unusual characteristics, all combined in one virus, Quay suggests is highly improbable to have originated in nature, but is much more likely to have come from a laboratory carrying out this type of research.

Two further points are of interest here: First, Quay made a range of suggestions about what might be better done now to control such dangerous research. His own view is that there is no benefit to be gained from such research (for a detailed account of this viewpoint see Shinomiya et al., Reference Shinomiya, Minari, Yoshizawa, Dando and Shang2022), and that it should be banned, but given the vested interests involved, he thinks that is unlikely to be achieved. Therefore, he proposed subjecting all research involving select agents to an Institutional Review Board (IRB) structure, similar to the process used for human clinical trials. He argued this system would safeguard the most dangerous research and likely achieve international acceptance, including in China.

Secondly, in conclusion, Quay warned about the consequences of not improving regulation, pointing to similar dangerous research with other potentially pandemic viruses. He noted that in December 2019, synthetic biology experiments were being conducted at the WIV involving the Nipah virus. Nipah is classified by the CDC as a Bioterrorism Agent and is extremely deadly (>75% lethality). He concluded that a lab-acquired infection involving a modified, perhaps airborne, Nipah virus would result in a disaster far worse than the COVID-19 pandemic, making the latter “look like a walk in the park” (Quay, Reference Quay2024, p. 22).

The evidence presented by opponents of a natural outbreak thesis is discussed here in such detail as these views were increasingly resonating with the target audience, that is members of the U.S. Senate. This was demonstrated quite explicitly in the exchange between Senator Mitt Romney (R—UT) and Professor Ebright in the discussion following the oral testimonies. They both agreed that federal regulation with the force of law is required to protect society from the possible implications of such research. Scientists, they argued, just cannot be allowed to self-regulate their work in such areas of research. The Senate Hearing was designed to contribute to the development of such new regulations by the Senate, including the “Risky Research Review Act” introduced by Senator Rand Paul (R—KY) (Paul, Reference Paul2024).

In early 2025, the political context of the GOF-debate changed significantly when the second Trump Administration began. As a White House Fact Sheet in early May made clear, the new President had long “theorized that COVID-19 originated from a lab leak at the Wuhan Institute of Virology” (The White House, 2025a, p. 2). The Fact Sheet explained that the President had issued an Executive Order to deal appropriately with the issue. The 2025 Executive Order defined GOF research in terms of an imminent threat, stating that if left unregulated, it poses a significant danger to American citizens. The consequences of unregulated GOF research include widespread death, damaged public health systems, disruption of American life, and reduced economic and national security (The White House, 2025b). In addition to ending all federally funded dangerous GOF research in the United States, the order stated that a new oversight system was to be in place within 120 days and that this would “strengthen top-down independent oversight; increase accountability through enforcement, audits and improve public transparency; clearly define the scope of covered research” (The White House, 2025b, p. 2). By the middle of 2025, these different policies were being put into effect (NIH, 2025; USDA, 2025).

In sum, the actors pursuing some form of securitization of GOF-research involved in this case study were, on the one hand well qualified practicing scientists, but increasingly also politicians, initially in the form of members of the U.S. Congress and, beginning in 2025, U.S. President Trump. Throughout, the object of their concern was GOF experiments on dangerous, potentially pandemic pathogens. With the incoming Trump administration, which saw this as an immediate threat requiring drastic action, the measures taken to address related security concerns were in line with a threatification, not a riskification of GOF research. Key elements of the case are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. The securitization of GOF research in the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the origins of COVID-19

Conclusions

The aim of this paper was to demonstrate that the elaboration of the securitization process by dividing it into riskification and threatification sub-processes, as suggested by Englund and Barquet, was a useful means of gaining a better understanding of the different attempts to characterize and govern GOF research as dual-use research of concern in the United States since the turn of the century. Thus, we reviewed three cases, identifying the context in which they unfolded, the characteristics of the speech acts, the involved actors, and the relevant governance or policy proposals. This has revealed several similarities across the cases, but also significant differences between the first two and the final one. Applying Englund and Barquet’s framework allowed us to characterize two of the cases as instances of riskification and the final case as one of threatification.

The first two cases of biosecurity concerns, which were revolving around a set of virology experiments, referenced in and leading up to the 2004 Fink Committee Report and Subsequent NSABB Guidance and dual-use concerns triggered by two avian influenza GOF-experiments in the early 2010s and extending to the pandemic period, involved a debate about riskification largely confined to the practical scientific community and scientifically orientated officials. However, after the pandemic, and particularly when it became more widely accepted that the cause could have been a laboratory accident, the debate changed from one confined largely to the scientists and began to involve society as a whole (Mills, Reference Mills2025), and particularly their political representatives, that is members of the U.S. Congress and President Trump after taking office in early 2025. It can therefore be reasonably argued that the involvement of politicians in positions of authority and the shift in perception from the widely supported discourse of a natural cause of the pandemic, the dual-use risks of which should be governed by scientists, to the alternative discourse of scientists actually causing the pandemic provided the facilitating conditions for the shift from riskification to threatification. In other words: these contextual and actor-specific factors represent the core of the difference between the first two and the third case analyzed. As a recent study analyzing threat politics more broadly has noted, politicians may invoke a threat “to build public support for tackling it and to try to spur congressional or executive action” (Rosenberg, Reference Rosenberg2025, 3). Clearly, this was the intention of President Trump, aiming at an overhaul of the governance of dangerous GOF research. However, whether this threatification will persist and result in the intended policy change remains to be seen.

Already shortly after issuing the May 2025 Executive Order by President Trump, the threatification move was criticized by scientists and observers accustomed to believing in the necessity of freedom of scientific enquiry and self-regulation based on some form of risk–benefit calculation (Global Biodefense Staff, 2025; Gronvall, Reference Gronvall2025; Mallapaty, Reference Mallapaty2025). According to news reporting, parts of the federal public health bureaucracy tasked with stopping GOF funding and revising policy on GOF research have been trying to minimize restrictions on future research (Kopp, Reference Kopp2025). In addition, some biosafety and biosecurity practitioners have proposed “that all GOF research should be conducted under a robust framework of enhanced BSL controls that explicitly define its dual usability, classify any such enterprise as DURC, engage regulatory oversight, and establish ethical responsibility within the scope and tenor of international law” (Giordano & Di Eullis, Reference Giordano and Di Eullis2025). While some of the proposed measures are suitable to strengthen biosecurity in order to prevent misuse of dual-use GOF research, the system overall is based on a risk–benefit calculation and, if implemented, likely to fall short of the threatification pursued by U.S. President Trump. The same would apply to a localized governance approach that would “adopt a tiered risk governance approach to distinguish between low, moderate, and high-risk research” (Gillum, Reference Gillum2025, p. 4).

Although the top-down approach pursued by the Trump administration has relegated life scientists and their epistemic community from the front row of securitizing actors for the time being, it is to be expected that as the biotechnology revolution continues in the coming decades, there will remain wide support for freedom of scientific enquiry. However, there may be experiments that politicians decide should not be carried out, as such experiments are seen as creating direct threats rather than diffuse risks (Relman, Reference Relman2014).

While this paper has focused on the GOF discourse in the United States around the three cases discussed in some detail, GOF research on pathogens is clearly a global phenomenon. As a 2023 study has detailed, between 2000 and 2022, slightly more than half of global research publications (referenced in PubMed) on GOF or loss-of-function research were attributable to U.S. researchers and about one third of research was undertaken by researchers from multiple institutions in different countries (Schuerger et al., Reference Schuerger, Batalis, Quinn, Kinoshita, Daniels and Puglisi2023, pp. 13, 15). Given this global distribution of GOF research, second-order effects of the new United States approach are likely in countries where researchers have strong collaborative ties with U.S. institutions. We would expect the analysis of related governance discussions in these countries to benefit from adopting riskification and threatification perspectives on already ongoing or future securitization processes.

Finally, we are stating the obvious when noting that the revolution in the life sciences and concomitant biotechnology advances are not confined to GOF research, but are much broader in scope. Concerns about their dual-use potential have also been expressed by outside observers and stakeholders alike. Both the global nature and the accelerating progress of advances in the life and associated sciences were recognized, for example, in 2006 by a committee of the U.S. National Academies—often referred to after their two co-chairs as the Lemon-Relman Committee (National Research Council, 2006). Based on the recognition that lists of agents or of specific technologies may well be outdated by the time they have been printed, the Committee recommended to adopt a broader perspective on the range of potential future dual-use concerns that go beyond a list of pathogens or a particular technology. In its assessment, “advances in understanding the mechanisms of action of bioregulatory compounds, signaling processes, and the regulation of human gene expression—combined with advances in chemistry, synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and other technologies—have opened up new and exceedingly challenging frontiers of concern” (National Research Council, 2006, pp. 8–9). Almost two decades later, yet another illustration of such a new frontier of concern was highlighted in a paper in Science titled “Confronting risks of mirror life” (Adamala et al., Reference Adamala, Agashe, Belkaid, Bittencourt, Cai, Chang, Chen, Church, Cooper, Davis, Devaraj, Endy, Esvelt, Glass, Hand, Inglesby, Isaacs, James, Jones and Zuber2024). The essential points of the paper were summarized for a wide general audience in the New York Times (Zimmer, Reference Zimmer2024). In a nutshell, it is becoming possible for chemists to make mirror proteins and mirror RNA molecules. Thus, it is probable that in coming decades scientists could make mirror cells. The problem is that our immune systems would not recognize such invader cells, which could spread without any resistance through living organisms. In short, mirror bacteria would be capable of producing a disaster in many different ways. This prospect led the authors of the article in Science to characterize this prospect as a threat and to recommend that:

Unless compelling evidence emerges that mirror life would not pose extraordinary dangers, we believe that mirror bacteria and other mirror organisms, even those with engineered biocontainment measures, should not be created. We therefore recommend that research with the goal of creating mirror bacteria not be permitted, and that funders make clear that they will not support such work (Adamala et al., Reference Adamala, Agashe, Belkaid, Bittencourt, Cai, Chang, Chen, Church, Cooper, Davis, Devaraj, Endy, Esvelt, Glass, Hand, Inglesby, Isaacs, James, Jones and Zuber2024, p. 1353).

Scientists in many countries, in our opinion, should be aware that they may also confront such issues in the not-too-distant future. Given the resulting need to engage in some form of securitization discourse related to advances in the life and associated sciences, an increased awareness will be required across all of the scientific disciplines involved so that life and associated scientists and technologists can meaningfully contribute to such discourses. (Magne et al., Reference Magne, Ibbotson, Shang and Dando2025).

Acknowledgement

The contribution to this article by the corresponding author was funded by the German Ministry of Research, Technology and Space under grant number 01UG2202A.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.