This book is intended for anyone interested in inventing languages. You don’t need a previous background in linguistics or in language invention. Right now, you might not be confident about your ability to invent a language from scratch; but this book will help you reach this goal while learning a lot about languages along the way.

This chapter focuses on what language invention entails. Section 1.1 introduces constructed languages (such as Esperantor or Na’vi) in contrast to natural languages (such as Arabic or Cherokee). Section 1.2 distinguishes constructed languages from creative language forms such as slang and language games. This chapter also covers the main types of constructed languages and the key motivations underlying language invention (Sections 1.3, 1.4). Section 1.5 addresses some important considerations to keep in mind when creating a language, and Sections 1.6 and 1.7 walk you through a fictional scenario and a guided conlanging exercise. Section 1.8 previews the rest of the book, and Section 1.9 suggests additional sources if you want to learn more about the topics covered in this chapter.

Key Words

A priori conlangs

A posteriori conlangs

Alien languages (exolangs/xenolangs)

Alternative languages (altlangs)

Artistic languages (artlangs)

Auxiliary languages (auxlangs)

Compounds

Constructed languages (conlangs)

Engineered languages (engelangs)

Fictional languages

Grammar

Descriptive grammar

Prescriptive grammar

Language games (ludlings)

Linguistic systems

Logical languages (loglangs)

Morpheme

Morphology

Naming languages

Natural languages (natlangs)

Philosophical languages

Phonology

Secret languages

Slang

Syntax

1.1 What Are Constructed Languages?

If you were asked to provide an estimate of how many languages are spoken in the world today, what would be your guess? Although it’s hard to pinpoint exactly, many researchers calculate that there are between 5,000 and 7,000 languages nowadays. Some, like English or Hindi, are used by millions of people. Others, such as Ainu or Yaaku, only have a handful of speakers. Regardless of the number of speakers, the geographical area where they are spoken and whether they have a writing system, English, Hindi, Ainu and Yaaku are natural languages (natlangs) that arose without conscious design. Natlangs spoken today vary greatly; but the rich variation in language they evidence is expanded even more when we consider invented languages, most commonly referred to as constructed languages or conlangs.

Unlike natlangs, constructed languages are designed consciously. Some are relatively well known, such as Esperanto or Klingon. Some are more obscure, such as Balaibalan or Volapük. Some constructed languages have been around for a while, like Esperanto, invented in the nineteenth century. Others, including Klingon or Dothraki, are more recent. Conlangs appear to be more pervasive now than a few decades ago, but it is important to note that language invention is not an exclusively recent phenomenon. In fact, more than 1,000 constructed languages have been documented since the twelfth century, and the number of conlangs keeps on growing every year.

Do constructed languages resemble natlangs? They do in many respects. All conlangs feature large vocabularies and have developed grammatical systems. The best of them, such as Tolkien’s Quenya (High-Elven) and Sindarin (Grey-Elven), also include linguistic irregularities, ubiquitous in natlangs (unfortunately for adult learners). They also take into consideration how languages evolve through time.

Lingua Ignota (‘unknown language’ in Latin) is often considered the first documented conlang. It was devised by St. Hildegard von Bingen, a Benedictine abbess and polymath who lived in Germany in the twelfth century. St. Hildegard attributed the invention of Lingua Ignota to divine revelation. Lingua Ignota has 1,011 words, rendered in an invented alphabet composed of twenty-three litterae ignotae (‘unknown letters’). Most of these words are nouns, although there are some adjectives as well; examples are given below. Note that here and throughout, italics are used for words from other languages, and quotation marks for their English translation.

(1)

Lingua Ignota words (from Higley Reference Higley2007:205−230) a. Aigonz ‘God’ d. naurizin ‘ring’ b. diziama ‘licorice’ e. ornalz ‘hair’ c. gulzianz ‘potter’ f. razil ‘poison’

Having over 1,000 words is impressive, but this alone does not qualify Lingua Ignota as a language. This is because languages are not just collections of words; they are linguistic systems involving grammar, that is, systematic patterns that define how sounds, parts of words and words can combine in a given language.

Grammar is an often-maligned word, since it tends to be associated to restrictive, often out-of-touch language rules. If you went to school in an English-speaking country, you were probably told at some point that you should not end sentences with a preposition. In this view, common expressions such as Where (are) you at? or What’s up? would not be grammatical. So would a sentence such as My friend couldn’t adopt the kitty she fell in love with. This use of ‘grammar’ stands for prescriptive grammar. Prescriptive grammar is unavoidable in beginning language courses, or when you are learning to write formally in school. This book, however, focuses on descriptive grammar, which describes the ways in which sounds and words are organized in a language, irrespective of whether the language policy (typically self-appointed) decides if it’s proper.

Coming back to Lingua Ignota, researcher Sarah Higley shows that in addition to having a sizable vocabulary, this language includes morphemes as well. Consider, for example, the similarity in shape and meaning of the Lingua Ignota words in (2).

(2)

Lingua Ignota (II) (Higley Reference Higley2007:102) a. zaimzabuz ‘quince’ b. kisanzibuz ‘cotton tree’ c. scuanibuz ‘myrtle’ d. mizamabuz ‘mulberry tree’

You probably noticed that all words in (2) end in -buz and refer to bushes or trees. Because the same meaning patterns with a similar form, -buz ‘bush, tree’ is a morpheme, that is, a meaningful unit that cannot be divided further. Thus, since Lingua Ignota displays grammar, it can be considered a constructed language, albeit a primitive one.

Natlangs also have morphemes; consider, for example, the words in (3). The second verb in each example begins with re-, which adds the meaning ‘again’ to the basic verb form; thus redo is ‘to do again,’ reconsider is to consider again and so on. We conclude that re- is a morpheme in English. You can probably think of many other verbs in English carrying this morpheme.

(3)

English verbs a. do redo b. consider reconsider c. think rethink d. write rewrite

The Lingua Ignota scholar Sarah Higley is also a language inventor and sci-fi writer under the pen name of Sally Caves. One of the languages she invented is Teonaht, spoken by the Teonim, who live in a region that floats over or submerges below the Caspian and Black seas. Teonaht was recognized with the ‘Smiley Award’ in 2007. This award, given by conlanger David Peterson between 2006 and 2020, recognized noteworthy conlangs described online during a given year. Other conlangs that received this recognition include Brithenig, Rickchik, Kēlen and Ithkuil. We will consider these and other noteworthy conlangs further throughout this book.

Lingua Ignota features some morphology but lacks a well-developed grammar. On the other hand, recent conlangs such as Esperanto, Quenya or Na’vi have fully developed grammatical systems including an inventory of sounds that can be combined in specific ways (phonology), a set of morphemes indicating distinctions such as singular vs. plural (morphology), and a way in which words combine within a sentence (syntax). We will explore the grammatical characteristics of these and other languages throughout this book – some might even serve as inspiration as you work on your own conlang.

1.2 Slang, Secret Languages and Language Games

Conlangs evidence creativity and love of language, but they are not the only outlet humans have to play with or modify language. Throughout history, people have invented and enjoyed secret languages and language games (ludlings). Secret languages, codes or ‘argots’ are used by communities throughout the world to obscure meaning to outsiders and to foment a feeling of inclusiveness for those who are ‘in.' Examples of secret languages include Lunfardo, used by criminals in Argentina from the late nineteenth century, and Polari, a secret gay language used in Britain in the 1960s–1970s. Some Polari words are given in (4):

(4)

Polari words (Baker Reference Baker2019:288−296) a. polari ‘the gay language; to talk’ b. bona ‘good’ c. auntie ‘an older gay man’ d. dinarly ‘money’

Slang comprises words and phrases used informally by specific groups of people. It is also a creative form of language which sometimes derives from secret languages, although it emphasizes more the ‘insider/outsider’ perspective. Slang changes quickly and tends to be used mostly by younger speakers in casual contexts. You probably use slang with your peers; you might have noticed that other age groups use different slang words from you. Some well-known examples of slang include Valley Speak, which originated in California in the eighties, and which still lives on in expressions such as ‘whatever’ or ‘totally.’ Examples of fictional slang include Nadsat in A Clockwork Orange, and Slayer Slang in the Buffy the Vampire Slayer show.

Slang can overlap with language games, as in French ‘Verlan,’ based on syllable reversal (‘verlan’ is the reversed form of the French word l’envers ‘reverse’; the ‘s’ is silent). As shown in (5), in Verlan monosyllabic words, the consonant and vowel are switched. In longer words, syllables are reversed.

(5)

Verlan words Verlan French English translation a. ouf fou ‘mad’ b. looc cool ‘cool’ c. céfran français ‘French’ d. féca café ‘coffee’

Language games also have secrecy and in-grouping as goals, but they tend to be used more for fun. They occur throughout the world and are particularly favored by children. If you grew up in an English-speaking country, you’re probably familiar with Pig Latin. If you spoke Spanish as a child, you might have used or heard Jerizonga. Examples for both are given in (6). Can you figure out how they work?

(6)

Pig Latin and Jerizonga words English word Pig Latin Spanish word Jerizonga a. ‘sun’ unsay sol solpo b. ‘world’ orldway mundo munpudopo c. ‘night sky’ ightnay yskay firmamento firpimapamenpetopo d. ‘pulverize’ ulverizepay pulverizar pulpuveperipizarpa

Pig Latin and Jerizonga use specific ‘rules’ or patterns to obscure words. In Pig Latin, the word-initial consonant is moved to the end, followed by ‘ay.’ In Jerizonga, each syllable is followed by ‘p’ and a vowel identical to the one before.

Language games occur in other languages. For example, in Japanese Babigo the syllables ‘ba, bi, bo, bu, be’ are inserted after each syllable in the word (thus, the word sushi is pronounced ‘subushibi’), and in Swedish Rövarspråket (‘robber language’), each consonant is doubled and an ‘o’ is inserted between them (transforming Ikea into Ikokea, for example).

Are language games, secret languages and slang similar to conlangs? Like them, they are creative and evidence conscious design. Crucially, however, they lack a grammatical system different from the language they are associated with. Rather, they modify the ways that sounds and/or words are combined in a natlang to be playful or/and to make the meaning obscure to outsiders. Slang, secret languages and language games are certainly part of ‘language play,’ like puns and invented scripts, but they are not full languages.

1.3 Types of Conlangs

Several conlang types can be distinguished, beginning with naming languages, that is, conlangs consisting mostly of a list of words with little or no grammar. Examples of naming languages include Lapine, the rabbit language in Richard Adam’s novel Watership Down, and the alien languages Runa and Jana’ata in Mary Doria Russell’s novels The Sparrow and Children of God. Most scholars also consider Lingua Ignota a naming language as well since it has little morphology and no syntax.

Auxiliary languages (auxlangs) are conlangs designed to serve as common languages for people from diverse language backgrounds; they combine vocabulary and grammar from two or more languages. Some examples include Esperanto, based on Romance, Germanic and Slavic languages; Afrihili, building on Swahili, Akan and other African languages; and Guosa, combining aspects from Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo. The most successful auxlang to date is Esperanto. One of the reasons why it continues to be popular is that it is relatively easy to learn, particularly for speakers of Romance languages. Although Esperanto was more popular in the past, it still has a thriving community, particularly in Europe, and even hundreds of native speakers.

Artistic languages (artlangs) are designed for creative purposes. They are often connected to specific fictional groups. This is the case of Klingon, Na’vi and Quenya, developed for some of the fictional groups in Star Trek, Avatar and Lord of the Rings, respectively. Artlangs can also stand alone, as in Trent Pehrson’s Idrani. Fictional languages are those existing in a fictional world; Dothraki and Láadan are examples, and so is Loxian, designed by Roma Ryan for Enya’s albums Amarantine and Dark Sky Island. Exolangs (also referred to as xenolangs or alien conlangs) are languages used by fictional aliens. Examples include Klingon and Fith, spoken by centauroid sapient marsupials on the planet Fithia.

Engineered languages (engelangs) explore one or more properties of language and thus test the limits of how language works. Examples include Láadan and Kēlen. Láadan, created by Suzette Haden Elgin, explores how a language based on female experience would work. Kēlen, by Sylvia Sotomayor, explores what a language without verbs would be like. Logical languages (loglangs) aim to be logical and remove ambiguity from language. Well-known loglangs include Loglan, invented by James Cooke Brown, and its successor Lojban.

Other conlang types include philosophical languages and alternative languages (altlangs). Philosophical languages are conlangs that aim at building perfect languages that reflect thought precisely. Philosophical languages had their heyday in the seventeenth century; one example is John Wilkinson’s Philosophical Language. Altlangs are conlangs set in an alternative history. One example is Brithenig, invented by Andrew Smith; it explores what a Romance language in the British Isles would be like if it had displaced Celtic and undergone Celtic historical changes.

A conlang can belong to more than one category above. For example, John Quijada’s Ithkuil is both an engelang and a philosophical language; Láadan is both an engelang and a fictional language (since it features in Elgin’s Native Trilogy novels), and Heptapod B in Denis Villeneuve’s movie Arrival can be considered an artlang, exolang and engelang.

It is also useful to distinguish between a priori and a posteriori conlangs. A priori conlangs are created from scratch, with no direct connection to other languages; examples include Láadan and Na’vi. A posteriori conlangs, on the other hand, are based on one or more languages. For example, Brithenig is based on Latin and Celtic languages, and Eskayan is based on Boholano, Spanish and English.

1.4 Why Do People Invent Languages?

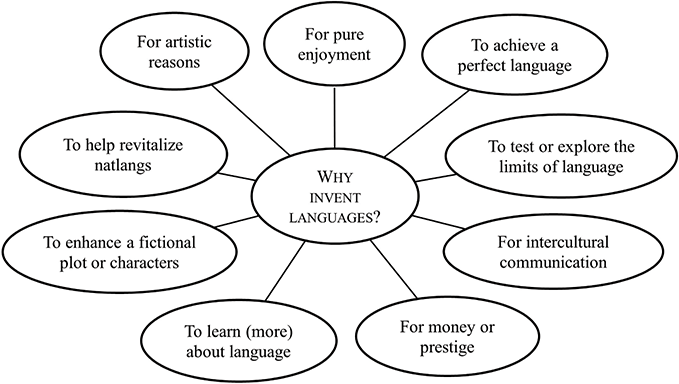

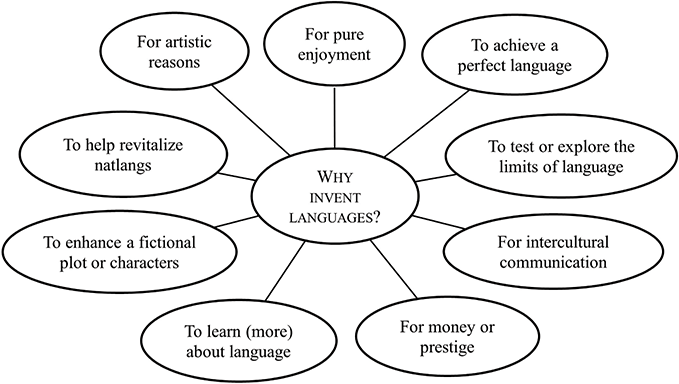

Conlang classification takes into consideration the goals of language invention (Figure 1.1). Some conlangs aim to improve language and achieve a perfect connection with thought (philosophical languages); others have as goals to achieve international (or intercultural) communication (auxlangs). Some conlangs explore the limits of language or linguistic avenues not attested in natlangs (engelangs), while others are designed for artistic purposes (artlang) and/or to enrich a fictional world (fictional languages).

Figure 1.1 Conlanging motivations.

Figure 1.1Long description

Titled Why Invent Languages?, the diagram presents various reasons for language invention. These reasons include: For artistic reasons, For pure enjoyment, To achieve a perfect language, To test or explore the limits of language, For intercultural communication, For money or prestige, To learn (more) about language, To enhance a fictional plot or characters and To help revitalize natlangs.

The paragraph above summarizes some of the main reasons why people throughout history, all around the world, decide or have decided to spend weeks, months or their whole lives to developing conlangs. But there are also other possible motivations underlying language invention, including pure fun or enjoyment.

In his 1931 talk ‘The Secret Vice,’ J. R. R. Tolkien comes out of the language inventor closet and addresses why he devoted so much time and effort to the invention of the languages featured in his literary works. Tolkien highlights artistic pleasure as his primary motivation. In fact, Tolkien wrote The Hobbit, Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion to provide a fictional world for his constructed languages – not the other way around.

J. R. R. Tolkien was the first language inventor that incorporated linguistic irregularities and historical change in conlanging. Partly because of this, Tolkien is considered by many to be the first modern language inventor.

Some inventors create languages for other reasons, including fame and fortune. Two examples are Edward Rulloff (1819/1820–1871) and Charles Bliss (1897–1985). Rulloff funded his unrelenting efforts to develop a philosophical language through a notorious criminal career involving theft, fraud and even murder. Charles Bliss, the inventor of Blissymbolics, hoped to become famous in the academic world. When Blissymbolics was successfully adopted as a means of communication by the Ontario Crippled Children’s Centre in the 1970s, Bliss sued the school. A settlement was reached, which Bliss used to print his own Blissymbolics teaching manual, all to become more famous.

Language invention can also be used to help revitalize declining or dormant languages. Some scholars consider Cornish, Hawaiian, Modern Hebrew and Maori to be invented in a way, since they involve conscious design of vocabulary and grammar, at least to some extent. More obvious examples include Patxohã and Houma. Patxohã is based on Pataxó, a language formerly spoken in Brazil. The revitalization of Patxohã is ongoing; much of its vocabulary was invented by the community, while its grammar is based on Portuguese and Maxakalí. For the dormant Muskogean language Houma, which appears to have been most closely related to Choctaw, there has been a community effort to reconstruct the language since 2013. Even communities that regularly use a language for everyday purposes regularly augment it by inventing new words in response to a changing world, as we will see in Chapter 16. Thus, the distinction between natlang and conlang is not absolute.

It is important to note that there might be more than one motivation at play in the invention of a given conlang. For example, Láadan was invented to explore what a female-centered language would be like; and to incorporate it into a fictional story. In addition, professional conlangers can be commissioned to invent a language for money; their conlangs certainly enrich the fictional world associated with them.

Some people think that language inventors are geeky; some might discount language invention as a waste of time. But as the documentary Conlanguing: The Art of Crafting Tongues shows, not only is language inventing an old endeavor in the history of humankind, it is also harmless (unless funded by a career in crime, à la Rulloff) and can be extremely fulfilling.

There is one more possible reason to invent a language: to learn about how languages work. This is the main goal of this book: to serve as a guide to conlanging, while learning more about the languages of the world.

1.5 How to Go About Constructing a Language

This book provides step-by-step guidance in inventing an original conlang. Regardless of your goals and motivation, it’s important (i) to avoid replicating languages you are familiar with; (ii) to be aware of which characteristics are unique, and which relatively common, in natlangs; and (iii) to strive to be consistent as you build your language from the bottom up.

It is extremely important to be aware of the linguistic characteristics of your native language so that you do not create a simplified or alternative version of it. This is a common pitfall for first-time language inventors. It also happened to me the first time I tried to invent a language. When I was twelve, inspired by Tolkien’s Elvish languages in Lord of the Rings, I invented a language that, in hindsight, sounded somewhat like Hawaiian as it was based on Spanish but had a limited number of consonants and vowels. I tried to teach this language to my three best friends at the time under the pretense that the radio was broadcasting lessons in it. Because they were good friends, they put up with my attempts to teach them my conlang for a couple of weeks.

You might be multilingual or familiar with several natlangs (and perhaps some conlangs as well). In this case, you might be tempted to model your conlang on another language. But although natlangs and conlangs certainly can serve as inspiration, it is important not to be overly influenced by them, unless of course the conlang you are developing is a posteriori.

It is also important to learn about how natlangs work; specifically, which linguistic characteristics are relatively common in the thousands of languages currently spoken, and which are unique or relatively uncommon. This is crucial to make informed decisions about what you would like your conlang to be like. In general, while conlangs strive for originality and tend to feature unique linguistic patterns, auxlangs typically incorporate well-represented linguistic characteristics, as a compromise among different linguistic systems and vocabularies. The best auxlangs are also easy to learn, at least for the speakers of the languages they are based on.

Finally, it is essential to keep track of your choices as you work though designing a sound system, applying it to make up dozens or hundreds of words in your conlang, and developing the morphological and syntactic structure that will help communicate the concepts embodied by those words. It is important to apply the phonological, morphological and syntactic structures you decide upon systematically to keep the language as consistent as possible.

This book provides examples of how English works, since it assumes that you are a native or fluent speaker of this language. It also includes many examples from Spanish, my native language and one that many English speakers are familiar with, as well as from a wide array of languages spoken in different parts of the world. It is expected that this approach will help you make informed decisions about the linguistic aspects you would like to include in your conlang, without being overly influenced by languages you know well.

The book will also guide you step by step in the process of conlanging. As you advance through the book, you will be reminded to step back each time you add layers to your conlang to make sure your conlang is as consistent as possible.

1.6 Fictional Scenario

When building a conlang, you first need to decide who the language is for. Who are your conlang speakers? What are they like? Where do they live? What is their world like? Your answers will inspire you and guide your linguistic choices to some extent.

Perhaps you already have a clear idea of the fictional or non-fictional group you would like to focus on. Regardless, bear with me while considering the following fictional scenario:

It is the year 3245. An apocalyptic disease (or a meteorite, or another civilization, or all three: your choice) has wiped out most of the population in the planet. The survivors need to come together to subsist/take their planet back. But the survivors come from linguistic communities speaking very dissimilar languages.

Do you envision this scenario applying to Earth? Another planet or moon? Was this planet or moon colonized by earthlings at some point? Or is it a fictional planet?

If you answered ‘Earth,’ or a real planet or moon overrun by earthlings, you need to decide which languages are spoken by most of the apocalyptic survivors, and a plausible reason why those languages survived. You could combine the characteristics of some of the surviving languages (as in Belter from The Expanse) or you could decide that the language spoken in this moon or planet is unrelated to any other language. Both are great choices, but your conlang approach will differ in each case. This book mostly focuses on inventing a language from scratch, but also provides you with some ideas and guidance of how to build a posteriori languages as well.

Inventing an auxlang might appear to be an easier endeavor than creating an a priori conlang, but in reality, it might be harder to invent an auxlang that is truly unique. The reason is that many auxlangs are based on well-known, widely spoken languages, mostly Indo-European. These include Romance languages (e.g., Spanish, French, Portuguese) or Germanic ones (e.g., English, German, Dutch). If you are interested in creating an original auxlang and do not wish to replicate Eurocentric ones such as Esperanto or Volapük, you should consider languages from other linguistic families and/or spoken in other areas of the world.

Considering current or plausible scenarios that result in bringing speakers of different languages together might inspire which languages to draw from. For example, the refugee crisis that started in 2011 as the result of the Syrian civil war inspired some of my students to develop an auxlang for refugee children and children living in the countries sheltering them. Before the COVID pandemic, another team of students devised a common language for a fictional medical community. We will consider some aspects of the latter conlang in Chapter 2.

1.7 Guided Conlanging Practice

To have a better idea of what conlanging entails, let’s walk through devising a mini-conlang for a language spoken in the fictional world of Ur. Ur has separate but interconnected regions, and its population is divided into four main groups, as described in (7).

(7) The population of UR

a. The Aqua people live deep under the ocean. They gather sea vegetables and shellfish. They are well known for their intricate dancing. b. The Gem people live underground. They dig for minerals and metals. They are master jewelers, and they love to sing, especially while they work. c. The Grass people are nomadic herders. They have a fierce reputation and trade all over Ur. d. The Fog people live in floating dwellings. They are the elite (philosophers, priestesses and royalty) and are fluent in all Ur languages.

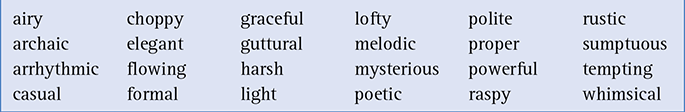

How do you imagine the language for each group sounds? Powerful, whimsical, graceful? Table 1.1 lists some additional options: having a sense of how the language sounds might inspire you and guide some of your linguistic choices.

Table 1.1 Some ways to describe how a language sounds

|

|

|

|

|

|

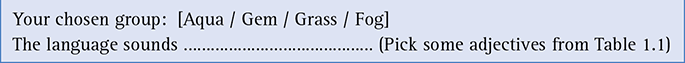

Next, pick the Ur group that strikes you as the most intriguing or fun, and follow the steps below to flesh out a mini-language for it.

1.7.1 Design a Basic Sound System

In this step you will select some of the vowels and consonants for your selected Ur group. Before we begin, fill out Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 Initial steps

|

1.7.1.1 Select the Vowels

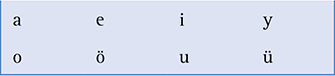

Choose four–six vowels from Table 1.3. Decide how each vowel sounds; their pronunciations should differ from each other.

Table 1.3 Vowels to choose from

| a | e | i | y |

| o | ö | u | ü |

1.7.1.2 Select the Consonants

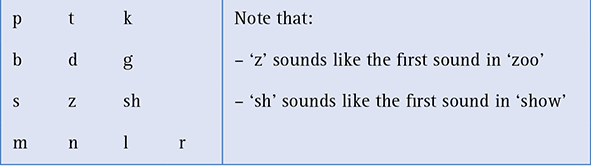

Choose nine–ten consonants from Table 1.4.

Table 1.4 Consonants to choose from

| p | t | k | Note that: | |

| b | d | g | – ‘z’ sounds like the first sound in ‘zoo’ | |

| s | z | sh | – ‘sh’ sounds like the first sound in ‘show’ | |

| m | n | l | r |

1.7.2 Create Some Initial Words

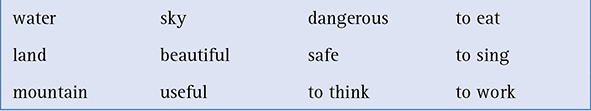

Combine the vowels and consonants that you selected above to render the words in Table 1.5. The words you come up with can be short (e.g., ‘zun’) or long (e.g., ‘meshitani’). Regardless, they should be pronounceable (i.e., avoid words like ‘nkrtz’ or ‘uueiszsh’).

Table 1.5 Initial words

| water | sky | dangerous | to eat |

| land | beautiful | safe | to sing |

| mountain | useful | to think | to work |

Note that the words in Table 1.5 represent different word types (nouns, adjectives, verbs); you can choose to make each word type differ in your conlang if so you wish.

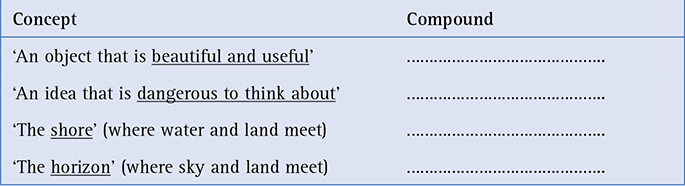

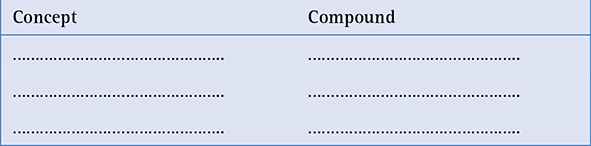

1.7.3 Create Some Compounds

Now, translate the concepts listed in Table 1.6 by combining the words you invented in Section 1.7.2 into compounds (words combining two or more words, such as playground, date night and well-known). You can also include additional compounds of your choice in Table 1.7; make sure to indicate the concept that they correspond to in English.

Table 1.6 Compounds

| Concept | Compound |

|---|---|

| ‘An object that is beautiful and useful’ | …………………………………….. |

| ‘An idea that is dangerous to think about’ | …………………………………….. |

| ‘The shore’ (where water and land meet) | …………………………………….. |

| ‘The horizon’ (where sky and land meet) | …………………………………….. |

Table 1.7 Additional compounds (optional)

| Concept | Compound |

|---|---|

| ……………………………………….. | ……………………………………….. |

| ……………………………………….. | ……………………………………….. |

| ……………………………………….. | ……………………………………….. |

1.7.4 Provide Some Basic Morphology

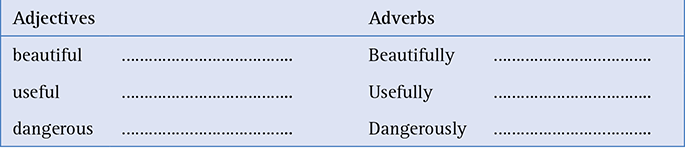

In this step, you will develop morphology to derive adverbs from adjectives, and to inflect verbs in the past, present and future tense.

1.7.4.1 Derive Adverbs from Adjectives

In many languages, adjectives and adverbs differ morphologically. For example, in English the suffix -ly is added to adjectives to create adverbs: compare beautiful with beautifully, and sad with sadly. In the Ur conlang you are developing, you can form adverbs by adding a prefix to an adjective related in meaning. To do so, decide which is the adverbializing prefix; and then add it to the adjectives in Table 1.8 to form the corresponding adverbs.

Table 1.8 Adjectives and adverbs

| Adjectives | Adverbs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| beautiful | ……………………………….. | Beautifully | …………………………….. |

| useful | ……………………………….. | Usefully | …………………………….. |

| dangerous | ……………………………….. | Dangerously | …………………………….. |

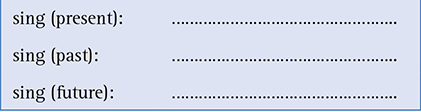

1.7.4.2 Inflect Verbs for Tense

Tense is often expressed morphologically on verbs. In this conlang, present, past and future tenses are conveyed by verb prefixes.

First, decide which prefixes indicate past, present and future; then, complete Table 1.9 to inflect the verb to sing in these three tenses.

Table 1.9 Tense

| sing (present): | ………………………………………….. |

| sing (past): | ………………………………………….. |

| sing (future): | ………………………………………….. |

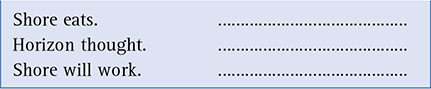

1.7.5 Decide the Word Order

In this step you will decide on the relative order between subject and verb, nouns and adjectives, and adverbs and verbs.

1.7.5.1 Subject-Verb Order

In many languages, including English, the subject (S) precedes the verb (V) in the sentence: Paul sleeps; Brennan walks (SV order). But in other languages such as Hawaiian, the subject follows the verb (VS order).

First, decide whether the conlang have SV or VS word order. Then, translate the sentences in Table 1.10 reflecting this word order. (Note that ‘Shore’ and ‘Horizon’ are popular names in Ur.)

Table 1.10 Subject-verb order

|

|

1.7.5.2 Adjective-Noun Order

Languages differ in whether adjectives precede nouns, as in English (beautiful house), or the other way around, as in Italian (casa bella). Indicate which order applies in your conlang: noun-adjective, or adjective-noun.

1.7.5.3 Verb-Adverb Order

Languages differ in whether adverbs precede verbs, or the other way around. Indicate which order applies in your conlang: verb-adverb, or adverb-verb.

1.7.6 Translate Some Sentences

Now, translate the sentences in Table 1.11 taking into consideration your word order choices above. You can also add some sentences of your own.

Table 1.11 Sentence translations

|

|

1.8 A Conlanging Blueprint

The guided practice in Section 1.7 illustrates some steps involved in conlanging: from choosing a fictional group, to creating words, to deciding on morphemes and syntax that make it possible to build fully formed sentences. The following chapters expand on these and other components, guiding you toward designing a fully fledged conlang. To help you envision the overall process, this section previews the content of the remainder of the book.

Chapter 2 focuses on the creation of the fictional world, taking into consideration your conlanging goals and how you would like the conlang to sound. In addition to fleshing out some characteristics of the fictional world and the fictional conlang speakers, it provides guidance on how to sketch a fictional map and to compose a short text related to the fictional world. This chapter also introduces the fictional world of the ‘Salt People,’ whose language will be developed throughout the book.

Chapters 3–6 cover sounds. Chapter 3 introduces the basics of speech sounds and how to select vowels for a conlang, while Chapter 4 focuses on consonants. Chapter 5 shows how both can combine in languages, while Chapter 6 covers stress and tone. By the end of Chapter 6, you will already have constructed several words for your conlang.

Chapter 7 addresses how to build a conlang vocabulary. You will expand and/or refine the words you have already created and combine some of them into compounds. You will also begin to translate your fictional text from Chapter 2.

Chapters 8 and 9 cover morphology for nouns and verbs, respectively. You will decide the types of affixes your conlang will have and consider whether you want your conlang to express gender, tense and/or other meanings morphologically. You will also continue translating your fictional text, focusing on its morphological aspects.

Chapters 10–13 discuss syntax. You will consider which word order could work best in your conlang, how negation is expressed and how different sentence types (such as questions or commands) are structured. We will also cover how languages express the source of information, and how they build complex sentences. You will also continue to translate your fictional text, focusing on its syntactic aspects.

Chapters 14–18 discuss other areas that can add depth to your conlang, including designing a constructed script or ‘conscript’ (Chapter 14) and expanding the lexicon further by considering nuances of meaning (Chapter 15). Chapter 16 addresses dialectal variation and historical evolution, and Chapter 17 introduces additional modalities used in languages. Finally, Chapter 18 wraps up the book and provides an example of a translated text from the language of the Salt People.

To Learn More

This chapter draws in part from Okrent (Reference Okrent2010), Adams (Reference Adam2011) and Sanders (Reference Sanders, Punske, Sanders and Fountain2020); see also Goodall (Reference Goodall2023). To learn more about Blissymbolics, see the 1974 documentary Mr. Symbol Man by Bob Kingsbury and Bruce Moir, available on You Tube (www.youtube.com/watch?v=HAjOJFEFbuI). To learn more about Edward Rulloff, Lingua Ignota and Eskayan, see Bailey (Reference Bailey2003), Higley (Reference Higley2007) and Kelly (Reference Kelly2022), respectively. Tolkien’s essay ‘The Secret Vice’ is included in Fimi and Higgins (Reference Fimi and Higgins2016).

Lapine is featured in Richard Adam’s novel Watership Down and its sequel Tales from Watership Down, and Runa and Jana’ata in Mary Doria Russell’s novel The Sparrow and its sequel Children of God; all are highly recommended. To learn more about slang and secret languages, see Davie (Reference Davie2018) and Baker (Reference Baker2019); the latter focuses on Polari. For Buffy Speak, see Adams (Reference Adam2003).

McWhorter’s TED talk ‘Are Elvish, Klingon, Dothraki and Na’vi Real Languages?’ is a great, short introduction to conlangs and their characteristics (http://ed.ted.com/lessons/are-elvish-klingon-dothraki-and-na-vi-real-languages-john-mcwhorter). The documentary Conlanging: The Art of Crafting Tongues (Britton Watkins Reference Watkins2017) is an informative, touching documentary on language inventors (a bonus feature titled Even More Conlanging is also available). You can learn more about philosophical languages in Eco (Reference Eco1997). For language play, see Crystal (Reference Crystal1998) and Cook (Reference Cook2000).

A fun introduction on secret languages is Okrent’s article ‘The Pig Latins of 11 Other Languages’ in Mental Floss, April 23, 2013 (http://mentalfloss.com/article/50242/pig-latins-11-other-languages). If you want to brush up on your Pig Latin, you can try a Pig Latin translator such as the one in https://lingojam.com/PigLatinTranslator.

The Language Creation Society supports conlangs and their inventors and offers a wealth of information about constructed languages: www.conlang.org. You can learn more about Teonaht on the Teonaht website (https://web.archive.org/web/20110608162956/ www.frontiernet.net/~scaves/teonaht.html) and about conlangs awarded the ‘Smiley Award’ by David Peterson here: http://dedalvs.com/smileys/. Fiat Lingua provides an archive of conlang languages: www.fiatlingua.org/. For a trove of information about auxiliary languages, see the International Auxiliary Languages website (http://interlanguages.net/).

We will return to many of the conlangs mentioned in this chapter later in the book. In addition, you can learn Esperanto, High Valyrian and Klingon in Duolingo; or Belter, Esperanto, Quenya, Lojban, Klingon, Na’vi and Interlingua in Memrise. To learn more about the reconstruction of the Houma language, see the Houma Language Project (www.houmalanguageproject.org/).