Introduction

Behavioural science has become an increasingly important tool for improving public policy outcomes, including in health, education and taxation. A large body of research in psychology and behavioural economics demonstrates that individual decision-making is often shaped by heuristics, biases and contextual cues rather than by fully rational calculation (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Building on these insights, persuasion research has identified a set of influence principles – such as reciprocity, commitment and consistency, social proof, authority and scarcity – that systematically affect compliance and agreement when applied ethically (Cialdini, Reference Cialdini2009). In parallel, nudge theory has shown that small changes in choice architecture or message framing can produce substantial behavioural effects without restricting choice (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008). Together, these approaches offer a powerful toolkit for influencing behaviour in socially desirable directions.

In the domain of public finance, behavioural insights have increasingly been applied to tax compliance and debt collection, complementing a long-standing literature on deterrence and enforcement. As emphasized in Slemrod’s (Reference Slemrod2019) comprehensive overview of tax compliance and enforcement, traditional economic models – most notably the Becker–Allingham–Sandmo framework – treat tax evasion as a risky choice in which detection probabilities and penalties play a central deterrent role. Empirical evidence strongly supports this view, particularly through the effectiveness of third-party information reporting and withholding systems. At the same time, Slemrod (Reference Slemrod2019) underscores that compliance is shaped not only by formal enforcement parameters but also by taxpayers’ perceptions, beliefs and interactions with tax authorities. This recognition has motivated a growing body of research examining how communication, information and behavioural signals affect compliance decisions.

Within this broader enforcement context, behaviourally informed interventions – typically low-cost and communication-based – have emerged as a promising complement to audits and sanctions. Revenue authorities worldwide face persistent challenges in reducing arrears and encouraging timely payment, often relying on resource-intensive enforcement mechanisms with diminishing marginal returns. Behavioural interventions have therefore been deployed to influence compliance through messages that leverage social norms, salience and perceived monitoring (Behavioural Insights Team, 2012; Kettle et al., Reference Kettle, Hernandez, Sanders, Hauser and Shafir2016). Evidence from high-income countries shows that carefully designed messages can substantially increase compliance. In the United Kingdom, for example, social norm messages embedded in tax reminders significantly increased timely payment, generating additional revenue of £1.9 million within weeks (Hallsworth et al., Reference Hallsworth, List, Metcalfe and Vlaev2017). Similar effects have been documented in Belgium through message simplification and deterrence framing (De Neve et al., Reference De Neve, Imbert, Spinnewijn, Tsankova and Luts2019).

Related evidence from middle- and lower-income settings highlights both the potential and the constraints of behavioural approaches. Studies from Eastern Europe show that behaviourally informed communications improved compliance in Latvia and Poland (Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Jamison, Korczyc, Mazar and Sormani2017; Jamison et al., Reference Jamison, Mazar and Sen2021), while evidence from Bulgaria indicates that audit probability messages and reciprocity-based framing can influence compliance and agreement on delayed payments (Dimitrov and Vlaev, Reference Dimitrov and Vlaev2022; Doerrenberg et al., Reference Doerrenberg, Pfrang and Schmitz2022). More broadly, research on value-added tax systems in developing countries emphasizes the importance of enforcement capacity, information trails and institutional design in shaping compliance outcomes (Gerard and Naritomi, Reference Gerard and Naritomi2018). These studies show that while behavioural incentives can reinforce compliance, their effectiveness depends critically on how enforcement is implemented and communicated at the operational level.

Despite the rapid growth of behavioural interventions in tax compliance and debt collection, a significant gap remains in our understanding of how behavioural insights operate in direct, live, person-to-person communication. Most behavioural approaches focus on written or digital channels – letters, emails or text messages – implicitly treating compliance as the outcome of centrally designed messages delivered to passive recipients. Telephone-based interactions, by contrast, remain comparatively understudied, despite the fact that call centres constitute a primary interface between citizens and revenue authorities in many tax systems. This omission is particularly consequential because frontline staff do not merely transmit information – through their behaviour, communication style and enforcement approach, they actively shape how taxpayers perceive authority, fairness and compliance expectations.

A growing body of evidence suggests that tax officials’ behaviour plays a crucial role in shaping taxpayer compliance through multiple channels, including service quality, interaction style and perceived enforcement power. Research consistently shows that clear, competent and supportive assistance from tax officers reduces confusion and compliance costs, thereby increasing both filing and truthful reporting (Alm et al., Reference Alm, Cherry, Jones and McKee2010; Yusril and Awaluddin, Reference Yusril and Awaluddin2015; Wahyuni and Setiyawati, Reference Wahyuni and Setiyawati2023; Manap et al., Reference Manap, Mustangin, Sasmiyati, Edy and Zainuddin2024). Laboratory and field studies demonstrate that when tax administrations provide calculation assistance and personalized guidance, compliance improves (Alm et al., Reference Alm, Cherry, Jones and McKee2010), while survey-based evidence across individual, corporate and local taxpayers links higher compliance to officers’ clarity, responsiveness, friendliness and expertise (Yusril and Awaluddin, Reference Yusril and Awaluddin2015; Putra et al., Reference Putra, Loist, Butarbutar, Efendi and Sudirman2023; Manap et al., Reference Manap, Mustangin, Sasmiyati, Edy and Zainuddin2024; Robbi et al., Reference Robbi, Putra, Elyta and Mahdi2024; Pradisa and Ferdiansyah, Reference Pradisa and Ferdiansyah2025; Widyari and Supadmi, Reference Widyari and Supadmi2025). These findings underscore that compliance is not solely a function of enforcement intensity but is also shaped by how taxpayers experience their interactions with the tax authority.

Interaction style and respect appear to be particularly important. Evidence from Indonesia shows that respectful treatment by tax officials increases compliance, whereas authoritarian procedures reduce it, largely through their effects on trust (Prastiwi and Diamastuti, Reference Prastiwi and Diamastuti2023). Similarly, mixed-methods research from Rwanda indicates that facilitative, educational interactions enhance trust and perceived professionalism, while purely enforcement-focused encounters can undermine tax morale, especially among larger taxpayers (Mascagni et al., Reference Mascagni, Scarpini, Mukama, Santoro and Hakizimana2025). Qualitative studies further suggest that taxpayers expect proactive, fast and competent service, and that such interactions are viewed by both taxpayers and officials as central to voluntary compliance (Arisanti and Sujana, Reference Arisanti and Sujana2024). These findings emphasize that compliance emerges from the joint influence of enforcement power and trust – both of which are embodied in the behaviour of frontline tax employees.

Within this context, emerging evidence indicates that live, interpersonal communication may be particularly powerful. A field experiment with Colombia’s national tax agency found that replacing letters with scripted phone calls increased tax payments fivefold, yielding a 25 percentage-point improvement in compliance (Mogollon et al., Reference Mogollon, Ortega and Scartascini2021). Complementary qualitative and observational studies highlight the importance of conversational dynamics – such as rapport, emotional tone and the balance between authority and cooperation – in shaping repayment outcomes (Harrington, Reference Harrington2018; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Du, Yang and Huang2021). Harrington (Reference Harrington2018), for example, shows how debt collection agents in a UK utility company navigate tensions between institutional demands for enforcement and the need to maintain cooperative, face-saving interactions, tensions that can constrain effectiveness. Likewise, Liao et al. (Reference Liao, Du, Yang and Huang2021), analysing more than 3,000 recorded debt collection calls from a large consumer finance firm in East Asia, find that emotional cues such as reassurance or fear predict repayment behaviour, whereas excessively punitive messages provoke anger and reduce compliance.

Despite these insights, systematic evaluations of behaviourally informed training for public-sector tax authority employees – particularly at the national level – remain rare. This study addresses that gap by examining whether a behavioural training intervention can improve the effectiveness of phone-based tax debt collection in a public revenue agency. In collaboration with the Bulgarian National Revenue Agency (NRA), we designed and implemented a behaviourally informed intervention centred on a two-day soft-skills training programme for call centre agents. Drawing on principles from behavioural science, persuasion and negotiation theory, the training aimed to enhance agents’ ability to balance authority and cooperation, build rapport and secure payment commitments during outbound calls. The two-day training was attended by all 42 agents employed in the NRA call centre. To ensure full participation, the training was delivered in two separate groups held in two different weeks. This scheduling served two purposes: first, it allowed for smaller group sizes that facilitated greater interactivity and more in-depth discussion during the sessions; second, it ensured that agents who were on sick leave or had pre-planned absences could attend the session that best suited their availability. In addition to the 42 agents, three supervisors also participated in the training groups, which helped ensure consistent implementation and oversight of the newly introduced communication practices.

The empirical analysis relies on descriptive comparisons of monthly aggregated administrative data on debt-collection outcomes before and after the intervention. While the design does not permit definitive causal inference, it allows us to examine whether performance patterns following the training differ meaningfully from both prior periods and historical seasonal trends.

We find that, following the intervention, debt collection outcomes improved substantially across multiple indicators, including higher rates of full repayment, increased conversion among contacted debtors and a marked increase in total debt collected. These outcome measures follow the standard operational definitions of the Bulgarian NRA. These outcome measures follow the standard operational definitions of the Bulgarian NRA. Although call agents request that payment be made within seven days during the phone conversation, a full repayment is recorded when the outstanding amount is paid within this seven-day period following the initial call. In line with the NRA’s debt-collection process, each debtor case is typically associated with a single outbound call by a phone operator. If no payment or payment agreement is secured within approximately one week after the call, the case is escalated and transferred to a separate ‘special collection’ pathway (e.g., legal or court-based enforcement), which lies outside the scope of this intervention and the available data. At that point, both the debtor and the corresponding debt are removed from the call centre’s active calling lists, and there is generally no repeated calling of the same debtor within this collection stage. Notably, these improvements coincide with a period that historically exhibits a seasonal decline in collections, strengthening the plausibility of an intervention-related effect.

The study contributes to the literature in three main ways. First, it extends behavioural public policy research beyond written nudges to live, interpersonal communication, highlighting the importance of delivery channel in shaping behavioural outcomes. Second, it provides rare field evidence on the role of behavioural training for frontline public servants, showing how behavioural insights can be embedded in everyday administrative practice. Third, it offers policy-relevant evidence from a real-world institutional setting, contributing to the growing body of Findings from the Field that document how behavioural interventions perform under operational constraints.

The objective of the intervention was to equip call centre staff with practical skills grounded in persuasion and nudge theories, thereby improving the effectiveness of phone-based debt collection. We hypothesized that, relative to business-as-usual practice, calls conducted by behaviourally trained agents would be associated with higher repayment rates and greater amounts of debt recovered, reflecting the use of more effective influence and communication strategies.

Methodology

The present study seeks to make those contributions to the literature by evaluating a behavioural intervention in the context of tax debt collection calls. Our focus was on enhancing debt collection efficiency through targeted interventions, including training programs for call centre teams of NRA in Sofia and Plovdiv. In collaboration with the Bulgarian NRA, we designed and conducted a ‘nudge-type’ intervention consisting of three stages.

Main activities implemented

Stage one

Stage one was a preliminary stage. The main activity here was the listening and the analysis of more than 500 recorded calls of the operators working for the NRA call centre. Based on the analysis, we designed a two-day training, addressing the needs and the areas for improvement of the operators, creating case studies and role play based on real scenarios and the most common situations they encounter.

Between the 10th and the 20th of September 2024, the preliminary stage was conducted. We listened to and analysed over 500 recorded calls. Basically, we requested from the NRA prior to the training for the consulting team with a minimum of three calls from every agent (a future participant in the upcoming training) and also calls that cover all the different aspects of tax collectors’ work (company taxes, traffic fines, residential property taxes, mandatory health cover contributions, etc.). As a result of the analysis, we recognized the certain places in the dialogue where nudge messages can be implemented. Based on that, we customized a training design for interactive training based on two days of training sessions.

Stage two

Stage two included the conduction of the two-day soft skill training for the agency’s call centre employees focused on applying behavioural science techniques during calls with taxpayers. The training curriculum integrated concepts from negotiation and communication theory with evidence-based influence tactics derived from psychology and behavioural economics. Specifically, agents were trained in techniques such as: using empathetic and trust-building language, framing payment options in ways that leverage loss aversion (e.g., highlighting consequences of inaction), invoking social norms or peer examples when appropriate, employing reciprocity and commitment (e.g., thanking taxpayers for past compliance and seeking a pledge to pay) and structuring conversations to present easy ‘default’ solutions (like instalment plans) to encourage immediate action.

Between 1 and 15 November 2024, we conducted a two-day training sessions for call centre employees of NRA in Sofia and Plovdiv. The training was designed to improve their skills in negotiation, persuasion and psychological techniques (with a special focus on nudge techniques) for increasing debt collection success. The sessions were interactive and included activities such as case studies, role-playing and group exercises based on the call recordings.

The primary goal of the training was to enhance employees’ effectiveness in telephone-based debt collection by equipping them with:

1. Standardized communication strategies, ensuring consistency between new and experienced employees.

2. Positive attitudes towards innovative debt collection approaches, including behavioural psychology techniques such as ‘nudge’ interventions.

3. Advanced negotiation skills, allowing employees to apply persuasive tactics tailored to individual debtor profiles.

The training sessions were additionally tailored based on pre-training discussions with the managers and supervisors of the call centre.

The training was conducted over two days; the topics and activities are shown in the Appendix.

Stage three

Stage three included a summary of the suggestions derived through group work during the training brainstorming sessions and their presentation as part of a written script for telephone calls, which includes the key elements of the operator’s conversation with citizens and provides pre-prepared impact phrases containing certain ‘nudges’. For greater transparency regarding the script used prior to the training and the modifications introduced by the intervention, both versions of the script are provided in the Appendix.

Between the 16th and 26th of November 2024, stage three of the intervention. In this stage the ideas that were collected in the group discussions and brainstorming formats during the two-day training were organized into call scripts with specific phrases that should be used in tax collection calls. The new scripts were communicated to the call agents by their managers and supervisors, demonstrating organizational support for the newly presented approach.

Results

Overview and unit of analysis

This section presents descriptive evidence on changes in tax debt collection outcomes following the behavioural training intervention. All results are based on monthly aggregated administrative data provided by the NRA, which summarize outcomes across all outbound debt-collection calls conducted during each month. As described in the Methods section, call-level, case-level and debtor-level units largely coincide during the phone-based collection stage, and outcomes are routinely monitored by the NRA at the monthly level. Although the administrative data are available only in aggregated form and do not permit the reconstruction of the exact number of unique debtors or calls, the scale of operations can be approximated from institutional targets. The NRA call centre employs 42 debt collection agents, each with a daily target of approximately 90 calls, which is closely monitored by supervisors and tied to monthly performance evaluations. Assuming an average of 22 working days per month, this implies roughly 83,160 outbound calls per month. This figure reflects the volume of interactions underlying the analysis. It does also correspond with the number of unique debtors, because if payment or payment agreement is not secured within approximately one week following the call, the case is escalated and transferred to a separate ‘special collection’ pathway (e.g., legal or court-based enforcement), which lies outside the scope of this intervention and the available data. As a result, there is generally no repeated calling of the same debtor within the same collection stage, and call-level, case-level and debtor-level units largely coincide during the phone-based collection phase.

To assess whether debt collection outcomes changed following the intervention, we compare performance across defined pre- and post-intervention periods using multiple benchmarks. Given the absence of randomization and the use of aggregated data, the analysis is purely descriptive. The results should therefore be interpreted as indicative patterns rather than causal estimates.

Outcome measures

We focus on four primary outcome indicators, calculated monthly and averaged across comparison periods:

1. The proportion of contacted cases that resulted in full repayment (within seven days of the call);

2. The proportion of cases that made any payment or a partial payment (within seven days of the call and signed an agreement to pay the remaining balance);

3. The share of full repayments as a proportion of total payments (in Bulgarian leva);

4. The share of full repayments as a proportion of total outstanding debt (in Bulgarian leva).

Together, these indicators capture both behavioural responses (conversion to full repayment) and monetary outcomes.

Post-intervention performance relative to the previous year

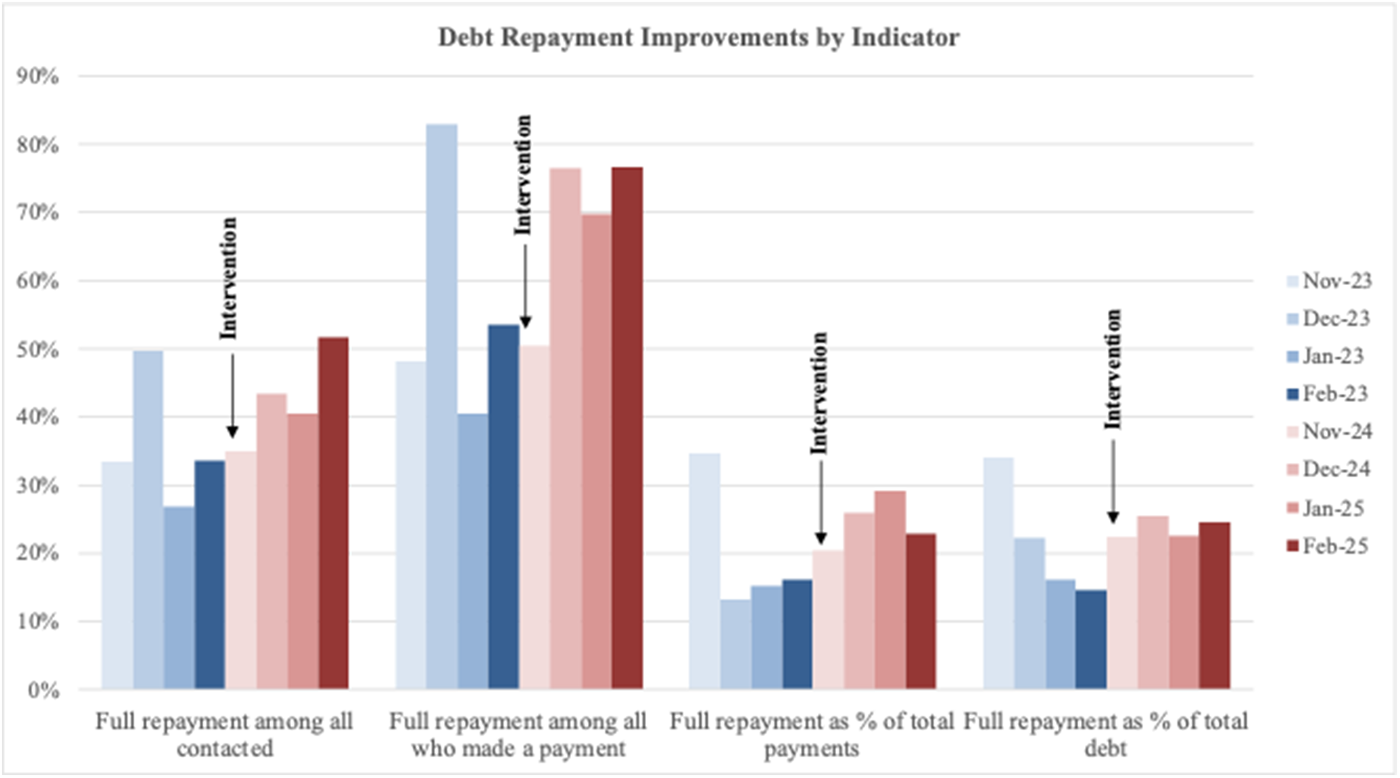

We first compare outcomes during the four-month period following the intervention (November 2024–February 2025) with the same calendar months in the previous year (November 2023–February 2024), thereby accounting for seasonality.

Across these indicators, performance improved markedly following the intervention:

• The proportion of contacted cases with full repayment increased from 36% to 43% (+7 percentage points).

• Among cases where any payment was made, the proportion resulting in full repayment increased from 56% to 68% (+12 percentage points).

• Full repayments as a share of total payments increased from 20% to 25% (+5 percentage points).

• Full repayments as a share of total outstanding debt increased from 22% to 24% (+2 percentage points).

In monetary terms, the increase in full repayments relative to total payments corresponds to approximately BGN 3.21 million in additional collections, while the increase relative to total outstanding debt corresponds to approximately BGN 1.31 million. Because these aggregates combine both new and legacy obligations and are not calculated at the individual debtor level, we adopt a conservative approach by averaging these estimates. This yields an approximate increase of BGN 2.26 million in full repayments over the four-month post-intervention period.

Figure 1 plots monthly outcomes for each indicator and marks the timing of the intervention (conducted during the first two weeks of November 2024). Relative to the same months in the previous year, post-intervention performance is both higher and more stable, whereas outcomes in the earlier period exhibit greater volatility consistent with seasonal effects.

Figure 1. Monthly debt repayment indicators before and after the behavioural training intervention, compared with the same calendar period in the previous year.

Outcomes shown include: (i) the proportion of contacted cases with full repayment; (ii) the proportion of full repayment among cases with any payment; (iii) full repayments as a share of total payments; and (iv) full repayments as a share of total outstanding debt. All values are calculated from monthly aggregated administrative data and are descriptive in nature; they are not adjusted for covariates and should not be interpreted as causal estimates. The comparison is intended to illustrate differences relative to historical seasonal patterns.

Intra-year comparisons: before vs after the intervention

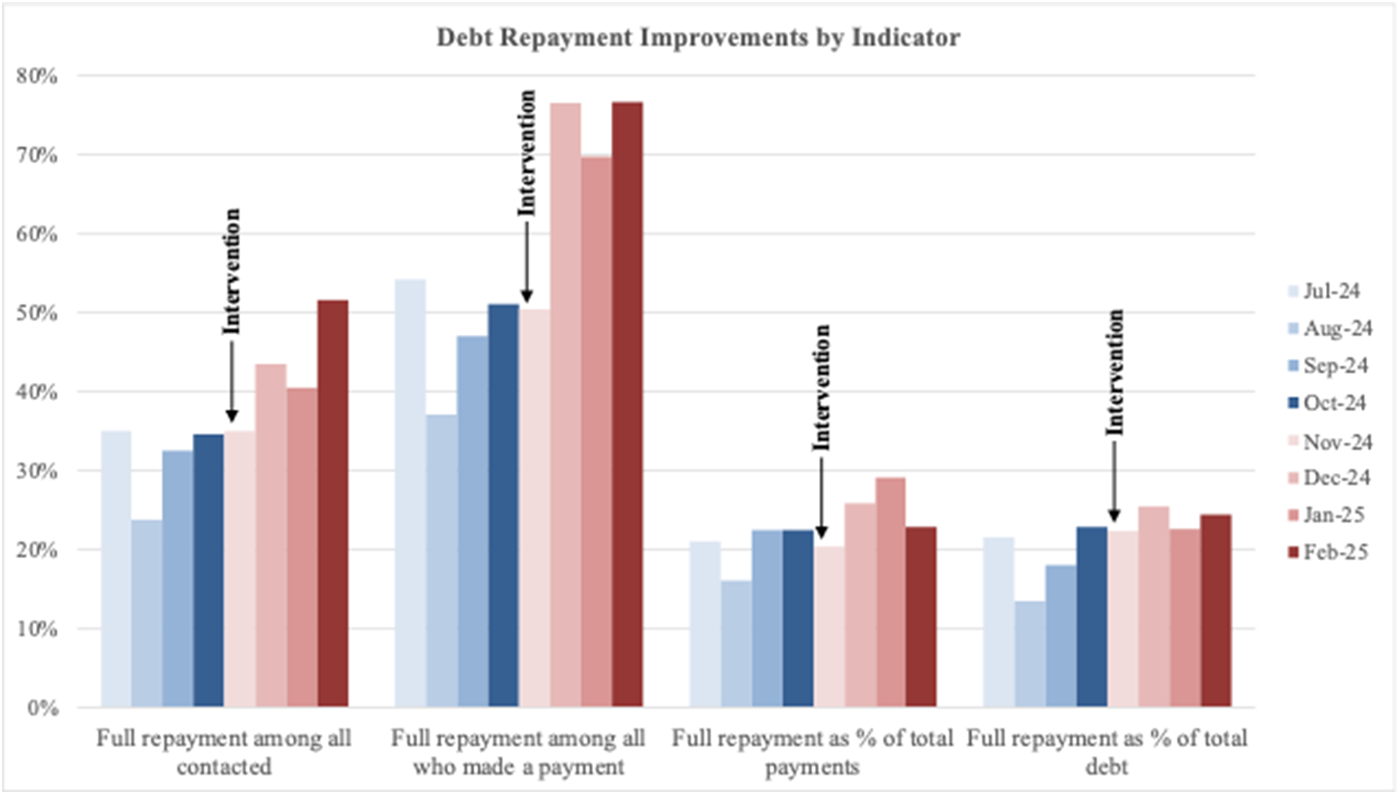

To further contextualize these findings, we compare post-intervention outcomes (November 2024–February 2025) with the four immediately preceding months (July–October 2024). This comparison captures short-run changes relative to the agency’s recent pre-intervention trajectory.

Relative to this baseline, we observe:

• An increase in full repayment among contacted cases from 31% to 43% (+11 percentage points);

• An increase in full repayment among paying cases from 47% to 68% (+21 percentage points);

• An increase in full repayments as a share of total payments from 21% to 25% (+4 percentage points);

• An increase in full repayments as a share of total outstanding debt from 19% to 24% (+5 percentage points).

Figure 2 presents the monthly evolution of these indicators before and after the intervention. The figure shows a consistent upward shift following the training period, rather than a continuation of pre-existing trends.

Figure 2. Debt repayment indicators during the four months before and after the intervention.

Seasonal benchmark: patterns in the absence of training

To assess whether similar improvements occurred in the absence of the intervention, we conduct an analogous comparison for the previous year, contrasting November 2023–February 2024 with July–October 2023.

In this period, when no behavioural training had taken place, outcomes follow a markedly different pattern:

• Full repayment among contacted cases increased marginally from 35% to 36% (+1 percentage point);

• Full repayment among paying cases declined sharply from 83% to 56% (−14 percentage points);

• Full repayments as a share of total payments declined from 21.5% to 19.8% (−2 percentage points);

• Full repayments as a share of total outstanding debt increased from 17% to 22% (+5 percentage points).

These results are consistent with a well-documented seasonal decline in repayment capacity during the year-end holiday period, when household expenditures tend to rise (Martin, Reference Martin2016). Notably, following the intervention, this seasonal decline is not only absent but reversed, with improvements observed across all four indicators.

Qualitative feedback from participants

In addition to administrative outcomes, we collected qualitative feedback from participating call centre agents. This written feedback was gathered by supervisors and subsequently provided to the authors. A synthesis of the responses indicates a broadly positive assessment of the training. When asked to evaluate the programme and its relevance to their professional needs, respondents emphasized its practical orientation, strong relevance to their daily work and the usefulness of behavioural influence techniques. Common themes included the clarity of the examples, the balance between theory and practice, and the value of role-play and discussion-based exercises.

When asked which behavioural ‘nudges’ they found most applicable in their interactions with debtors, agents most frequently mentioned social norming, salience and loss aversion. In addition, several respondents identified further training needs. In particular, they expressed a desire for continued behavioural training focused on handling aggressive clients, tailoring communication strategies to different debtor types and managing difficult conversations. Taken together, these responses suggest that while the intervention improved several dimensions of performance – especially full repayment outcomes – additional support may be required to address more resistant or adversarial cases, which may help explain the more limited changes observed in partial-payment outcomes.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that a behaviourally informed training intervention for call centre employees can significantly enhance debt collection performance in a real-world government setting. Over the course of a four-month post-intervention period, we observed measurable improvements across all core indicators: an increase in the proportion of cases with full repayment, a higher conversion rate among those who made payments and an overall rise in the share of full payments both as a percentage of total payments and total debt. The positive patterns observed relative to both previous seasonal trends and matched comparison periods strengthen the plausibility that the observed improvements are related to the intervention. These findings are consistent with existing evidence on the power of global behavioural interventions to influence compliance-related behaviour (Behavioural Insights Team, 2012; Kettle et al., Reference Kettle, Hernandez, Sanders, Hauser and Shafir2016; Hallsworth et al., Reference Hallsworth, List, Metcalfe and Vlaev2017; Hernandez et al., Reference Hernandez, Jamison, Korczyc, Mazar and Sormani2017; De Neve et al., Reference De Neve, Imbert, Spinnewijn, Tsankova and Luts2019; Jamison et al., Reference Jamison, Mazar and Sen2021; Doerrenberg et al., Reference Doerrenberg, Pfrang and Schmitz2022; Holz et al., Reference Holz, List, Zentner, Cardoza and Zentner2022; Mascagni and Nell, Reference Mascagni and Nell2022; Persian et al., Reference Persian, Prastuti, Adityawarman, Bogiatzis-Gibbons, Kurniawan, Subroto, Mustakim, Scheunemann, Gandy and Sutherland2023; Ramírez-Álvarez, Reference Ramírez-Álvarez2023; Abdelnabi et al., Reference Abdelnabi, Afraz, Ahmed, Ayub, Makki, Said, Schiektekat and Vlaev2024).

Beyond average treatment differences, the temporal pattern of outcomes provides additional insight into the dynamics and persistence of the intervention. Improvements are observed consistently across multiple post-intervention months, rather than being driven by a single spike immediately following training. Importantly, these gains persist throughout a period that historically exhibits a decline in debt repayment around the year-end holiday season. While the use of monthly aggregated data limits our ability to assess longer-run decay or reinforcement effects at a finer temporal resolution, the sustained elevation of outcomes over several consecutive months suggests that the training altered agents’ interaction practices in a way that endured beyond the immediate post-training period.

Importantly, as already mentioned, this study addresses a critical gap in the behavioural public policy literature by focusing on live, spoken communication. While previous field experiments, such as those by Mogollon et al. (Reference Mogollon, Ortega and Scartascini2021), have demonstrated the efficacy of replacing written tax notices with scripted phone calls, most behavioural interventions to date have relied heavily on written or digital messaging. Our results suggest that the interpersonal dynamics and immediacy of voice-based communication may amplify behavioural levers such as trust-building, social commitment and psychological accountability.

From a theoretical perspective, our findings extend the literature in three key ways. First, they affirm that behavioural influence strategies grounded in persuasion science and choice architecture (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008) retain their effectiveness when delivered in real-time, interactive conversations. This supports emerging work on the persuasive efficacy of spoken dialogue (DellaVigna and Gentzkow, Reference DellaVigna and Gentzkow2010) and aligns with insights from Liao et al. (Reference Liao, Du, Yang and Huang2021), who showed that emotional dynamics play a key role in compliance outcomes during debt collection calls. Second, the study highlights the value of training public sector employees in behavioural communication techniques – complementing growing calls to embed behavioural insights at the frontline of service delivery (John et al., Reference John, Smith and Stoker2009). This also echoes Harrington’s (Reference Harrington2018) findings, which emphasized the challenges agents face in balancing institutional demands with rapport-sensitive interaction styles.

Finally, by focusing on a debt collection call centre within an NRA, this study contributes with empirical insights to a domain where behavioural applications remain largely underexplored. While much of the existing research has centred on consumer finance or small-scale trials, our findings demonstrate that behaviourally informed training can be effectively implemented and scaled within public sector institutions. In doing so, the study responds to ongoing calls for more systematic evidence on how behavioural science can be integrated into real-time, voice-based government interventions – offering both practical benefits for debt recovery and a meaningful contribution to the expanding field of behavioural public policy.

From a practical standpoint, the intervention provides a replicable and cost-efficient model for enhancing compliance through human-centred behavioural training. Public agencies – particularly those relying on phone-based outreach – can leverage these insights by embedding behavioural principles into call scripts, agent coaching and performance evaluation systems. Moreover, our results suggest that live verbal interactions represent a promising frontier for adaptive behavioural influence, enabling agents to dynamically adjust their approach in response to the emotional cues, hesitation or resistance expressed by individual debtors.

Limitations

Nonetheless, this study has several important limitations that warrant careful interpretation of the findings. First, the empirical analysis is descriptive in nature and relies on comparisons of monthly aggregated administrative data rather than on individual-level or experimental variation. The intervention was not implemented as a randomized controlled trial, and while comparisons to both historical seasonal patterns and immediately preceding periods strengthen plausibility, causal inference cannot be definitively established.

Second, data availability constraints limited the granularity of the analysis. Daily, call-level or agent-level data – which would have enabled more sophisticated statistical modelling and tighter control for heterogeneity – were not accessible due to system complexity and confidentiality restrictions within the revenue agency. As a result, the analysis cannot control for changes in case mix, agent-level variation or repeated interactions beyond the phone-based collection stage.

Third, although we account for seasonality by design, the observed changes may still reflect unobserved confounding factors, such as contemporaneous organizational changes, shifts in enforcement practices or broader economic conditions. For these reasons, the results should be interpreted as strong indicative evidence consistent with an intervention effect, rather than as definitive causal estimates. Longer time horizons and finer-grained data would be required to assess whether these persistent effects attenuate, stabilize or compound over time.

Future research

Finally, this study raises several important questions for future research. Which behavioural influence techniques are most effective in live, interpersonal interactions? How can training programmes be optimized for different public service roles and institutional contexts? And how do different debtor characteristics shape responsiveness to specific influence strategies? Addressing these questions would benefit from richer data, experimental or quasi-experimental designs and finer-grained measurement of conversational dynamics.

More broadly, further research examining the interaction between message content, delivery channel and recipient characteristics could substantially deepen behavioural science’s contribution to public administration and compliance policy.

With respect to the present study, the findings underscore the value of viewing front-line public employees not merely as policy implementers but as behavioural change agents whose communication practices can materially influence policy outcomes.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2026.10031.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria under contract SUMMIT BG-RRP-2.004-0008-C01.

Competing interests

The authors declare there are no competing interests.