15.1 Introduction

In July 2014, as a very first measure under newly elected President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, the Egyptian government drastically reformed domestic energy prices. It increased the prices of most petroleum products and electricity for a wide range of consumers including industry, commercial businesses and households. At the time these reforms were implemented, Egypt faced a disconcerting record-high fiscal deficit, public debt surpassing 100 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) and the highest unemployment rate in decades, particularly among the country’s youth (World Bank 2017).

While this dire situation had been long in the making due to Egypt’s inequitable and excessive subsidisation system, the Arab Spring aggravated the country’s predicament. In the wake of unprecedented political instability – and a political revolution that led to the ousting of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 – both the Morsi and El-Sisi governments had expanded certain patronage packages, while growth rates dropped about 4 percentage points to below 2 per cent. To top things off, the net-hydrocarbon-importing country had faced international oil prices of around USD 100 per barrel in the preceding years. As a consequence, fossil fuel subsidies had become the largest government expenditure item, comprising 20 per cent of expenditures in 2013–14 (Moerenhout Reference Moerenhout2017).

In short, it was a situation of superlatives: fossil fuel subsidy reforms were exceptionally urgent, while the political climate appeared utterly hostile. At first sight, Egyptian politics appeared in disarray. Among other demands, a quest for more socio-economic justice and dignity was at the heart of the Arab Spring (Beissinger et al. Reference Beissinger, Jamal and Mazur2015). When Mohamed Morsi failed to deliver, mass protests supported by the military led to his arrest. By the time General El-Sisi (who had led the revolt against Morsi) became President El-Sisi, it was considered a substantial political risk to reform what was the country’s foremost method of distributing welfare.

It was to the surprise of many that the sizeable reforms were implemented with relatively little public, political and private opposition – notwithstanding the fact that they fundamentally contradicted the implicit social contract that had existed for decades. This chapter explains why political economy conditions in 2014 were actually exceptionally beneficial to the implementation of subsidy reforms. It does so with reference to ‘behavioural realist traditions’, i.e. theories on how heterogeneous stakeholders act and why. I first shortly summarise political developments since the Arab Spring in Egypt. Next, I explain behavioural realism and how to understand key stakeholder dynamics in Egypt. I then discuss each of these stakeholder dynamics in detail for the July 2014 reforms (with reference to the historical context). Finally, I discuss how these dynamics have changed since 2014, effectively constraining the government’s legitimacy.

15.2 Crisis and Political Turmoil in Post–Arab Spring Egypt

In February 2011, President Mubarak was ousted as a result of large street protests and a decision by the military to stay neutral. The key slogans of the revolution were a demand for dignity and socio-economic justice and opportunity. In late 2011, the Muslim Brotherhood won the parliamentary elections and its leader, Morsi, won the presidential election in June 2012. The Brotherhood was the most organised opposition group and had wide support among the many groups to which it offered social services. In the end, Morsi won with a narrow margin in the second round against Mubarak’s former prime minister, Amhed Shafik.

The subsequent efforts of President Morsi and the Brotherhood to consolidate political power came at the expense of countering the economic crisis. As Morsi’s popularity decreased and he repeatedly antagonised the military establishment, the military strongly supported street protests, which quickly grew to more than a million people across Egypt. In early July 2013, the military intervened, officially ‘on behalf of the people’; by many, it was heralded as a de facto coup. The army removed Morsi and the Brotherhood from power and installed an interim government until new presidential elections were held. The leader of the armed forces, General El-Sisi, gained a huge amount of popularity during this time. The Muslim Brotherhood was removed (by force) from Egyptian politics.

In the July 2014 election, Sisi was elected in the first round by more than 90 per cent of the vote. The election was recognised internationally and by all opposition parties. His first measure in office was to reform the country’s fossil fuel subsidies. From 2014 to 2016, Sisi’s popularity decreased as the impact of reforms was painful and accusations of governmental corruption were rampant. In 2015, Sisi had to replace his entire government because of corruption allegations. Furthermore, he used repressive tactics to reduce potential domestic opposition.

While there were positive results from the necessary but drastic domestic reforms, the resulting fiscal breathing space was used to pursue further reforms in August 2016. This second round of large, structural reforms was required to unlock an urgent International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan. Reforms included energy pricing increases, the introduction of a value-added tax and the free floating of the Egyptian pound. These measures led to a spike in inflation, which further increased Sisi’s unpopularity. At the time of writing, it is best to understand Egypt’s reform process as a country walking on a balancing cord in a socio-political hurricane (Moerenhout Reference Moerenhout2017).

15.3 Behavioural Realism and the Implementation of Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform

15.3.1 The Nature and Pace of Reforms: Stakeholders Matter Most

The failure to reform fossil fuel subsidies is primarily due to the political economy aspects of reform (Victor Reference Victor2009). Many analysts (from the IMF, the World Bank and the Global Subsidies Initiative) point to a maze of conditions that explain why reforms are successful or not, including timing, political regime, internal coordination, interest-group behaviour and technical characteristics of reform (Beaton et al. Reference Beaton, Gerasimchuk and Laan2013; IMF 2013a, 2013b; Kojima Reference Kojima2016). While it is clear that different conditions affect each other and that a successful reform outcome is causally complex, it is possible to understand (and, to a certain extent, predict) the political arena by understanding the dynamics among stakeholders. A behavioural realist stakeholder assessment has the advantage of recognising that stakeholders reach decisions in heterogeneous ways.

What does this mean? In general, it means that a political economy analysis of subsidy reform starts with how stakeholders actually behave rather than with how they should rationally behave to achieve the economically best possible subsidy reform process. It is logical that organisations concerned with macroeconomic stability (such as the IMF and World Bank) prescribe gradual reform as a key to successful long-term subsidy reform. This would be the wisest path from an economically rational standpoint. A behavioural realist school of thought argues that this does not coincide with the political reality under which many subsidy reforms take place.

Behavioural realism argues that different stakeholders make choices in different ways. Some stakeholders act rationally and will decide on exercising pressure based on the distributive impact of reforms, their interest and their potential influence (Baron Reference Baron2013). As described later, in the Egyptian context, the military and political opposition parties behaved in a more rational way. Other stakeholders, however, do not necessarily act as economically rational individuals. This is where behavioural realism innovates: by looking at the psychological drivers of citizens. It is without a doubt that citizens can be a powerful opposition group to subsidy reforms. This was particularly the case in Egypt, where they had demonstrated their power twice in three years’ time.

Therefore, behavioural realism argues that analysing stakeholders’ interests from a mere conventional rational choice point of view is insufficient to predict political outcomes (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2013). To assess the behaviour of citizens, behavioural realism relies on ‘system justification theory’ and ‘loss aversion’. The latter is the notion in behavioural economics that explains people’s preference for avoiding losses instead of acquiring equal gains. The former explains how individuals tend to behave when various belief systems conflict with one another. For example, while reform might be economically disadvantageous, citizens may have different dominant belief systems at the time of reform (such as fear of physical security or patriotism). System justification theory finds that people are often willing to accept rationally negative consequences to remain consistent with such dominant belief systems at the time of reform (Blasi and Jost Reference Blasi and Jost2006).

System justification theory and framing are closely related. A key insight of the framing literature is that individuals do not just make decisions based on individual preferences but in evaluation of a social context (Madrian Reference Madrian2014). System justification theory would assess what types of conflicting and dominant belief systems are shared among citizens so that frames can be developed to maximise reform acceptance. In this way, the behavioural realist framework employed here focuses on the role of actors opposed and in favour of reform and how framing may influence such actors within the window of opportunity to change socio-political structures – the social contract – in Egypt (see Chapter 1).

15.3.2 A Behavioural Realist Framework for Studying Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform in Egypt

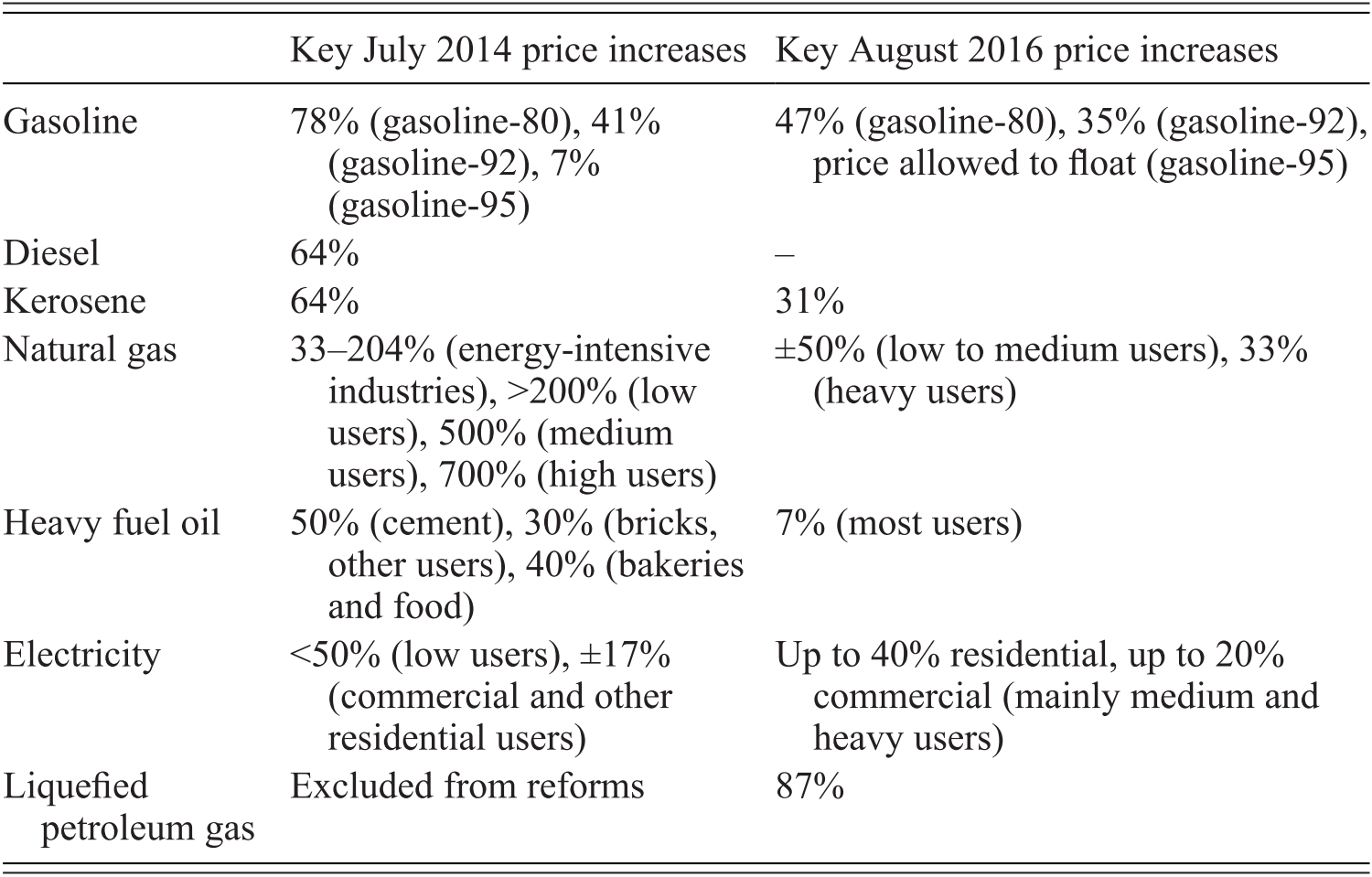

Researching Egypt’s 2014 subsidy reforms benefits from a behavioural realist approach. As Table 15.1 shows, the Egyptian reforms were of a ‘big bang’ nature. Egypt’s 2014 reforms are a good example of opportunistic reform. Many subsidy reforms in countries with traditionally low prices happen in shocks and during windows of opportunity, most often at the time of an observable fiscal crisis or after an election. Public choice scholars often speak of the ‘crisis hypothesis’ and the ‘honeymoon hypothesis’ to explain why structural reforms tend to be implemented in such an opportunistic fashion (Williamson Reference Williamson1994).

Table 15.1 Egypt’s 2014 and 2016 subsidy reforms

| Key July 2014 price increases | Key August 2016 price increases | |

|---|---|---|

| Gasoline | 78% (gasoline-80), 41% (gasoline-92), 7% (gasoline-95) | 47% (gasoline-80), 35% (gasoline-92), price allowed to float (gasoline-95) |

| Diesel | 64% | – |

| Kerosene | 64% | 31% |

| Natural gas | 33–204% (energy-intensive industries), >200% (low users), 500% (medium users), 700% (high users) | ±50% (low to medium users), 33% (heavy users) |

| Heavy fuel oil | 50% (cement), 30% (bricks, other users), 40% (bakeries and food) | 7% (most users) |

| Electricity | <50% (low users), ±17% (commercial and other residential users) | Up to 40% residential, up to 20% commercial (mainly medium and heavy users) |

| Liquefied petroleum gas | Excluded from reforms | 87% |

As the government is primarily responsible for the planning and implementation of reforms, the possibility of reform ultimately depends on its assessment of the need for reform, as well as whether key stakeholder groups are ready to accept such reforms without threatening the government’s legitimacy. In Egypt, I argue that legitimacy depends on three key stakeholder dynamics: (1) the social contract that guides the relationship between the state and its people, with the state composed of the government and the military, but with government primarily responsible towards its citizens, (2) the relationship between the military and the government and (3) the presence or absence of political alternatives to the government (Figure 15.1).

Figure 15.1 Stakeholder dynamics in Egypt.

First, the historical contract between the state and the people of Egypt has closely resembled that of other countries in the region. The key characteristic of that social contract is the exchange of people’s loyalty to the country’s authoritarian regime for a government-driven distribution of welfare. In practice, this means that the state was given a monopoly on Egypt’s economy, including the exploitation of hydrocarbons and other resources. In practice, the ruling government exploited the economy for its own benefit and without profound public oversight. In exchange, the government was expected to provide public employment and subsidised food, energy, housing, social security and so on (Fattouh et al. Reference Fattouh, Moerenhout and Sen2016). Taking away fossil fuel subsidies not only hurts people’s welfare, but it can also be a symbolic measure indicative of a changing social contract. Much of what Sisi has done so far is change the social contract unidirectionally: less distribution of welfare but a maintaining of authoritarian power.

Second, the relationship between the Egyptian military and government is one of checks and balances. The government needs the military to protect the country and, importantly, to support it in the domestic application of its policies. In simple terms, the government uses the security sector to be the ‘stick’ to ensure civil acquiescence to its regime. When people revolt against the state because of breach of the social contract, they often do this in the first place against the government and only secondarily against the military. This is because the military is believed to provide checks and balances to the government. In Egypt during the Arab Spring, for example, the army acted against Mubarak and Morsi. In reality, the military is a huge institutional apparatus that protects the political and economic power it shares with government. In practice, such interests are often linked to the energy sector, to large infrastructure projects and so forth. This makes the military a key stakeholder in large reforms.

Third, the government acts to silence political opposition. Political opposition attempts to manifest as a realistic alternative to rule the country. It seeks to influence the perception of stakeholder groups that it can cover their interests better than the current government.

15.4 Military Support and the Absence of Political Alternatives During the July 2014 Reforms

When Sisi implemented subsidy reforms in July 2014, two out of three constraining factors were mitigated, which made the implementation of fossil fuel subsidy reforms far easier. He had the support of the military, and there was no effective political alternative with the repression of the Muslim Brotherhood.

15.4.1 Why the Military Mattered to the Implementation of the July 2014 Reforms

Support of the military for fossil fuel subsidy reforms was necessary for two reasons. First, the military had strong interests in fossil fuel subsidies and could therefore be an opposing actor. Second, the military was needed to showcase strength and prevent unrest following reforms. The fact that President Sisi spent his life as an officer in the Egyptian army improved relationships. The military had been historically involved in non-military manufacturing, including energy-intensive industries (CMI 2013: 2), and in fuel black markets. Under Mubarak, however, many business deals went to private capitalists or internal security forces (Makara Reference Makara2013: 345–46). This was one of the reasons why the military ultimately did not suppress the Arab Spring protests (Barany Reference Barany2011; Akkas and Ozekin Reference Akkas and Ozekin2014: 83).

After Mubarak’s ousting, the military government re-established its economic and political position. In his one-year rule, President Morsi tried to reverse some of these steps and centralise power at the expense of the military’s political power (Brown Reference Brown2013: 45–50). He also pushed an Islamist agenda in which he counted on military support in safeguarding security. This challenge on two fronts made the military increasingly wary of its relationship with Morsi (CMI 2013: 4). At the same time, Morsi sought more oversight over the Suez Canal expansion project at the expense of the military (Marshall Reference Marshall2015: 11–12). Eventually, the military opposed Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood and started actively supporting massive demonstrations with the assistance of Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Marshall Reference Marshall2015: 18).

After his election as president, Sisi immediately extended the military’s influence on major manufacturing, transportation and infrastructure projects. Their leading role in the Suez Canal expansion project was also reaffirmed. He also involved the military in other projects, such as national bank loans to a subsidiary of Tharwa Petroleum, the only state-owned national oil company involved in upstream activities (Marshall Reference Marshall2015: 14–18). As such, fossil fuel subsidy reform could be advantageous for the military because it would strengthen the capacity of Egypt’s oil sector to pay off its debts to foreign operators. Via Tharwa Petroleum, the military would then benefit from foreign investors re-entering the Egyptian market (McMurray and Ufheil-Somers Reference McMurray and Ufheil-Somers2013). At the same time, following frequent negotiations with the military, Sisi decided to drop liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) from the 2014 subsidy reforms. It is believed that this is because the military was a key stakeholder benefiting from black markets for LPG cylinders (James Reference James2014). In exchange for these benefits, not only did the military support fossil fuel subsidy reform, but it also supported Sisi’s reign, which resembles that of a return to a repressive and authoritarian state (Khalaf Reference Khalaf2016).

15.4.2 The Absence of Political Alternatives and Prior Subsidy Reform Under Morsi

Because of its strong organisation, the Muslim Brotherhood was able to boost the numbers of protesters when it united with nationalistic civil society movements to oust Mubarak. It is also a key reason why it won the subsequent elections. However, the goal of replacing the Mubarak regime with an Islamic regime appeared far less important for most demonstrators than the primary economic reasons and the secondary demands for civil and political freedom (Beissinger et al. 2014: 4). The Muslim Brotherhood, however, spent most of its one-year reign on consolidating power. When the military intervened and removed Morsi from power, they also subsequently crushed the Muslim Brotherhood. Thereby, they effectively nullified the most organised opposition party.

In retrospect, the short time period that the Islamist government under President Morsi was able to govern mostly served as a catalyst for the subsequent El-Sisi presidency to actually implement substantial reforms. It confirmed the nationalistic sentiment that had been prevalent in the wake of the Arab Spring (Akkas and Ozekin Reference Akkas and Ozekin2014: 80) and the need for economic reforms. This is the platform on which Sisi would announce fossil fuel subsidy reforms. At the same time, the Brotherhood had become the scapegoat for the enduring financial crisis, with most political parties supporting its removal from power (Butter Reference Butter2013: 13). It also increased the popularity of the army, which gave Sisi a huge amount of political capital at the start of his presidency to actually implement reforms.

That said, Sisi benefited from some key fossil fuel subsidy reforms Morsi had initiated. In the 2012–13 period, prices for gasoline more than doubled for high-end vehicles, fuel oil prices increased by one-third for non-energy-intensive industries and by half for energy-intensive industries, while they rose by one-third for electricity generation. Electricity prices for households also increased on average by 16 per cent (Sdrazlevich et al. Reference Sdrazlevich, Randa, Younes and Albertin2014: 45). Natural gas prices also increased for residential, commercial and industrial consumers. However, the real prices for all refined products actually decreased due to inflation (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). In addition to actual price increases, some institutional innovations were prepared. One success was the development of an electronic tracking system to monitor fuel movements between suppliers and filling stations aimed at cutting fuel smuggling to Turkey and Gaza (James Reference James2014). The result was the uncovering of hundreds of fuel stations that only existed on paper (Butter Reference Butter2013: 14–15).

15.5 Energy Subsidy Reform and a Unidirectionally Changing Social Contract

Inevitably, the rationalisation of energy prices was going to impact a large part of his constituency, particularly lower- and middle-income households that had lambasted the Mubarak regime for not taking care of its people. To achieve acceptability for the reforms, Sisi attempted to mitigate distributional losses and change the perception of reform. He did this by playing into the belief systems of Egyptians via a wide variety of measures (described later). In this way, he tried to achieve buy-in for a structural reformation of the social contract. While in 2014 such a change may have appeared successful, his subsequent governing style resembles a return to the security state. This section shows that this attempt for a unidirectional change of the social contract has the potential to backfire on the regime.

15.5.1 A Crisis of Unprecedented Proportions and the July 2014 Reforms

By the time Morsi was ousted, Egypt’s debt surpassed 100 per cent of its GDP, the Egyptian government risked defaulting on its debts, GDP growth had dropped from 5 per cent pre-revolution to around 2 per cent in 2012–14 and unemployment had risen, particularly among the country’s youth (about 40 per cent of those aged between 20 and 24). At the same time, there was widespread inflation (rates were around 10 per cent after the Arab Spring) and a record-level budgetary deficit (nearly 14 per cent of GDP in 2012–13). Rural-urban income disparities also were on the rise, and there were considerable disruptions in fuel and electricity supply (Butter Reference Butter2013: 4; Paciello Reference Paciello2013: 2; ERPIC 2014; James Reference James2014; Muthuthi Reference Muthuthi2014). The only economic indicator that looked somewhat acceptable was the balance of payments, and that was only due to a generous financial support package from Gulf countries.

Energy subsidies were one of the main causes of this bleak picture. Expenditure on fuel subsidies had grown with a compound annual growth rate of 26 per cent between 2002 and 2013 (Clarke Reference Clarke2014), amounting to about USD 21 billion, which represented 8.5 per cent of GDP (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Laursen and Robertson2016: 2) and 20 per cent of public expenditure (El-Katiri and Fattouh Reference El-Katiri and Fattouh2015). The July 2014 reforms were steep price increases affecting various consumer groups and nearly all fuels and energy products, with LPG being the one notable exception. Among the main transport fuel price increases were a 64 per cent hike in diesel prices, a 78 per cent hike in gasoline-80 and a 40 per cent hike in gasoline-92. Kerosene prices also rose for all users by 64 per cent. Fuel oil prices did not increase for the electricity sector but did for the cement sector, food industry and other users. Natural gas prices increased substantially for all energy-intensive industries and for electricity generation. Residential natural gas prices were staggered by consumption levels, with larger consumers paying more; still, small-scale consumers saw their price double. Finally, electricity prices increased for all consumer groups but were also blocked to eventually allow for cross-subsidisation (Clarke Reference Clarke2014: 4–5).

15.5.2 Modest Mitigation Measures to Cover Distributional Losses

Besides using communication campaigns to affect belief systems (see below), the government also introduced several compensation measures to ease stakeholder reluctance about reform. As Egypt’s non-subsidy social safety net was poorly developed, a few short-term measures that strongly resembled conventional social contract politics were used to send out a message that Egypt’s government wanted to cushion the effects of the reform. With the crucial help of a USD 12 billion package from Gulf countries, Egypt implemented two stimulus packages in August 2013 and January 2014. Minimum wages in the public sector were raised, even though it increased the budget deficit (Muthuthi Reference Muthuthi2014: 4). This financial assistance from the Gulf also included USD 3 billion in fuel supplies to reduce the fuel shortages that had been so prominent during Morsi’s reign (Butter Reference Butter2013: 13–14).

Right before the fossil fuel subsidy reform, the government also extended the food subsidy system to include 20 new products (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). This was intended to reduce concerns about food price increases as a consequence of fossil fuel subsidy reforms. At the same time, the fact that it was implemented before and explicitly linked to the fossil fuel subsidy reform reduced the risk of protest due to loss aversion among the people. When a compensation measure is implemented before subsidy reforms and explicitly linked to such reforms, people are more likely to become attached to this compensation measure and, consequently, feel relatively less averse towards the associated subsidy reforms. Finally, there was a promise to keep LPG – a fuel widely used by poorer households – subsidised (El-Katiri and Fattouh Reference El-Katiri and Fattouh2015). As far as transport goes, there were several concerns (see below). In response, the government offered some free transport in army buses (James Reference James2014).

15.5.3 Psychological Drivers of Citizens at the Time of Reform

Relative to the size of the fossil fuel subsidy reforms, the aforementioned compensation measures were largely insufficient to ease the welfare losses of a large part of Egyptian households. The reason why the Egyptian population was willing to accept such reforms goes beyond mitigation measures. It is difficult to know whether Egyptians were simply tired of conflict or they were genuinely open to redrawing the blueprints of how Egypt was managed. However, it does seem likely that the government’s use of the carrot and stick – as well as the characteristics of reform – certainly played into the belief systems of Egyptians and, as such, increased the acceptability and support for reform. It did so in primarily four interdependent ways.

First, the timing of reform meant that Sisi could take full advantage of the so-called honeymoon period. In the wake of Morsi’s ousting, General El-Sisi and the military had gained popularity. Unlike Morsi, El-Sisi was also elected in one round and with about 90 per cent of the vote, giving him extensive political capital (James Reference James2014). El-Sisi used a large part of this political capital immediately by addressing fossil fuel subsidies, which had been left untouched by the transitional government (Paciello Reference Paciello2013: 3). System justification theory supports the notion that to be consistent with their electoral choice, people more easily trust the newly elected leader, even if his choices contradict their material interests (Blasi and Jost Reference Blasi and Jost2006).

Second, the immediate announcement of fossil fuel subsidy reform and the communication around subsidy reform left no space for people to doubt that reform was actually happening. By pressing the inevitability of reform, Sisi reduced a status quo bias as change was imminent, not just a potential plan. Behavioural psychology has shown that when change is certain, people adjust more easily to the idea of it (Blasi and Jost Reference Blasi and Jost2006). Egyptians were also aware that there were no real political alternatives. After three years of political turmoil, Sisi had a firm grip on power. In a ruthless display of power, he had cracked down violently on the apparatus of the Muslim Brotherhood. At the same time, public protests had been banned in 2014. This discouraged demonstrations (fear as a dominant belief system), particularly with the awareness that the leading general had just been elected president.

Third, the framing of reform and complementary measures linked back to the key demands protesters called for during the Arab Spring. Communication campaigns addressed the inequitable nature of fossil fuel subsidies by explaining how they disproportionally reached the rich. This argument fell in line with the protesters’ argument for more socio-economic justice. It also stressed the urgency of the measure to revive the Egyptian economy, which also played into the major concern that had caused the country’s two popular uprisings. Right after his election, Sisi also increased taxes on the wealthy and imposed a new capital gains tax on business. These moves got him praise, as they showed a contrast with the Mubarak regime (Marshall Reference Marshall2015: 19) and increased the belief that the government was serious about its intention to revive the Egyptian economy.

Fourth, a key element of Sisi’s strategy was to target the nationalistic sentiment that had been so dominant in the uprisings (patriotism constituting a dominant belief system). Sisi stressed the responsibility and need for ‘shared sacrifice’ (a key slogan in the fossil fuel subsidy reform communication campaign) to repair Egypt’s economy, while admitting that the price increases themselves were unpopular. He mixed the promise of renewed economic opportunity with a Nasseresque national pride to gain the most effective support for reform possible. One notable example outside of fossil fuel subsidy reform is the Suez Canal expansion project, which increased national sentiment by limiting sales of investment certificates to Egyptian nationals.

15.5.4 Intra-Governmental Coordination and External Support for Subsidy Reform

It is a consensus among international experts (such as the IMF, World Bank and the Global Subsidies Initiative) that subsidy reform requires a large level of international coordination and a supportive coalition. Stakeholder interests and influence gave the government a nearly blank cheque for economic reforms in July 2014. On the side of the government, Sisi had a predominantly technocratic cabinet that also favoured reform. This in itself already reduced internal competition within the high ranks of government. Sisi also took on leadership over reform and profiled himself as such externally. That said, even before Sisi’s election, Egypt’s government was working with internal and external experts (such as the Global Subsidies Initiative and the World Bank’s Energy Sector Management Assistance Programme) to prepare an extensive public relations campaign. This effort was essential given the severe lack of awareness about the costs and inequity of fossil fuel subsidies. Apart from some initial inconsistencies, there generally was consistency in messaging, from everyday governmental communication in the media to Sisi’s widely broadcasted televised speech (Clarke Reference Clarke2014).

Sisi could also count on the supporting stance of several other stakeholders. Already for years an informal coalition of businesses, industry, commentators and academics had argued in favour of meaningful subsidy reform (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). The media were also generally supportive of Sisi’s proposed reforms (Marshall Reference Marshall2015: 19) and mainly focused on the impact on households and on what the government could do to protect the poor. Both the general media and social media appeared to react in a balanced manner towards the reforms (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). Because of this wide coalition and consensus, other political stakeholders generally did not strongly oppose reform. Most political parties saw their role marginalised following Sisi’s landslide election. Some leftist political parties did oppose reform, but mainly on the grounds that they wanted more preparation, particularly with regard to the impact on households (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). Similarly, the wealthy elite did not oppose reforms, even though there was a clear direction from the government to target subsidies better. As in many parts of the middle class, a fatigue and desire for order and stability made the wealthy favour Sisi’s proposed reforms (The Economist 2015).

The most vocal actor opposing subsidy reform was the transportation sector. Transport operators believed that they were providing a public service and that this ought to remain supported. President Sisi and the prime minister negotiated with transport operators to make sure that they would not resort to increasing prices in the face of uncertainty. However, transport operators did increase their prices when subsidy reform was announced and even resorted to strikes and demonstrations in Cairo, Sinai and Alexandria (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). Many drivers, however, are not linked to particular political parties or associations, and the drivers’ union was fairly weak. This explained how their opposition was relatively well contained during the implementation process.

15.5.5 How People’s Belief Systems Changed, but Only Temporarily

Even though many people remained sceptical about the ability of the government to redistribute and invest savings from the subsidy reforms (El-Katiri and Fattouh Reference El-Katiri and Fattouh2015), system justification theory (Blasi and Jost Reference Blasi and Jost2006) suggests that people can easily extend the acceptability of a government within one issue (overthrowing Morsi, favouring economic recovery, measures targeting the rich, etc.) to another (actually being able to achieve tangible economic progress via subsidy reforms). The characteristics of reforms and actions by Sisi, as mentioned earlier, fundamentally altered the framing of subsidy reform from a measure that affirmed corruption during Mubarak to a necessity for economic revival under Sisi.

As in other countries in the Middle East and North Africa, the gradual acceptance that subsidy reforms were necessary to counter deteriorating economies represented a significant shift in the belief systems of Egyptian people (Moerenhout et al. Reference Moerenhout, Vezanis and Westling2017). The communication campaign approach used by Sisi was also in stark contrast to Morsi’s approach and generally to how the earlier social contract had operated for decades. It showed an understanding on the part of the government that convincing the Egyptian people of a particular policy had become a necessity to progress on impactful reforms.

At this stage, the social contract began to shift tangibly. The Egyptian people accepted that the government would no longer support a subsidy-based distribution of welfare, and in exchange, the government spent more effort to communicate its policies to the people. Nonetheless, the people’s expectations were high. The government promised more economic opportunity and more targeted social safety mechanisms for those in need. In the years after the subsidy reforms, these expectations were not met. Consequently, and also as a result of Sisi’s repressive mode of governing, a large part of the Egyptian people started to notice that the social contract was changing unidirectionally.

15.6 Frustration with the Change of the Social Contract Since the 2014 Reforms

In the two years following the July 2014 reforms, Sisi’s popularity decreased, as it became increasingly obvious that the social contract was changing in just one direction. Sisi was not able to meet the people’s expectations to deliver more targeted social assistance or to spur domestic economic growth. At the same time, Sisi was increasingly using repressive tactics to silence and prevent domestic opposition. Civil society organisations played a crucial role in mobilising Arab Spring protesters. The ability to freely organise during the Mubarak years covertly shifted the power balance in the social contract. Sisi attempted to undermine such a civil society response to his authoritarian rule.

Already in 2014, the price increases were very unpopular among the poor and lower-middle-income households, subsequently reducing the popularity of Sisi with this group (Clarke Reference Clarke2014). Notwithstanding Sisi’s efforts to better target social assistance to the poorer segments of Egyptian society, the slow pace of progress in this field does not re-establish trust in Sisi. On the eve of the 2014 reform, social safety nets had low coverage and inadequate financing and often disproportionally targeted the non-poor. Given other stakeholder dynamics (see below), strengthening social safety nets is a key priority for the El-Sisi government to retain trust in the reform process. Even though the government is working together with the World Bank to strengthen two large social safety net programmes (World Bank 2015), progress has been slow, while the Egyptian people feel the negative impact of the reforms (Moerenhout et al. Reference Moerenhout, Vezanis and Westling2017).

At the same time, Egypt is still waiting for economic growth. The tourism sector has not recovered, and there are overall few new job opportunities. The drop in international oil prices has been a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it reduces the gap between international prices and domestic prices. On the other hand, Gulf countries stalled financial aid packages because of their own internal fiscal problems (Aman Reference Aman2016). This has increased scepticism about Sisi’s competence to restore the economy. Also, wealthy Egyptians who favoured stability in 2014 are increasingly discontent as they feel the grip of Sisi’s policies that generally favour the poor (Walsh Reference Walsh2016). As far as the military is concerned, the 2014 reforms caused a shift in production and investment to the construction sector (Griffin et al. Reference Griffin, Laursen and Robertson2016). However, not all construction projects have yielded results as fast as hoped. For example, while the jury on the Suez Canal expansion is still out, many analysts believe that the government’s estimate of additional revenue was on the ambitious side (Egyptian Streets 2016).

On top of all of this, Sisi was obliged to pass a second round of large reforms to access a USD 12 billion IMF loan in August 2016. These reforms included energy price increases, the introduction of a value-added tax and a free floating of the Egyptian pound. The result was a large and unpopular inflation spike that reached almost 20 per cent in November 2016 (Moerenhout Reference Moerenhout2017).

The 2016 reforms and delay in results seem to have changed the perception of many poor and middle-income groups. One part of system justification theory is that people easily resort back to stereotyping. This played out in Egypt as the trust put in Sisi in July 2014 eroded very fast and was replaced with the traditional stereotype of a corrupt and incompetent government. While there had been allegations of corruption in the social security sector earlier on (James Reference James2014), a painful reality check occurred in the summer of 2015 when Sisi was forced to replace his entire government due to corruption scandals (Moerenhout et al. Reference Moerenhout, Vezanis and Westling2017).

15.7 Conclusion

Tough economic reforms and Sisi’s repressive mode of governing have frustrated the Egyptian people. The hope for a sustainable, new social contract seems stuck in the history books. In 2014, that hope had seemed real. The Arab Spring had demonstrated the strength of the people vis-à-vis government. The key priority was socio-economic justice and economic growth. At the same time, the government had a great window of opportunity to pass the difficult reforms needed to restart the engine of economic growth. These reforms included an alteration of the social contract: government could no longer provide across-the-board subsidies. At the same time, Sisi seemed aware of the need to communicate why these reforms were necessary and to ask for ‘shared sacrifice’. Whether or not the government intended it, the messaging and combination of measures played into the behavioural psychology of the Egyptian people, which ultimately led to a smooth implementation of energy pricing reforms.

Soon after 2014, however, the hope for a durable alteration of the social contract disappeared. It became increasingly clear that Sisi was attempting to alter the social contract unidirectionally by clinging to an authoritarian mode of power, while economic pressure on the population kept growing. His popularity decreased because of the negative impacts of subsidy reform. His Nasseresque political gamble to unite the country under a nationalistic discourse until the realisation of economic results failed. He had to replace his entire government due to corruption allegations, and the development of targeted social safety nets was much slower than anticipated. Finally, because of a drop in oil prices, financial aid from Gulf countries was cut off, leaving Sisi no choice but to implement more painful reforms to unlock IMF loans.

Egypt’s situation will be unsustainable if reforms do not quickly spur the engine for economic growth. Unless it provides tangible improvements for its citizens, an unpopular and repressive government that is reforming to comply with the conditions of international financial institutions will be at significant risk of political instability. Fossil fuel subsidy reforms that constitute unidirectional changes to the social contract are not durable in the long run.