I feel that the American Dream can be achieved best in the Nordic countries, where every child, no matter their background or the background of their families, can become anything.

We can have democracy in this country, or we can have great wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we can’t have both.

Having explored Nordic capitalism at the individual level (Chapter 5) and organizational level (Chapter 6), this chapter shifts to the societal level through the lens of the American Dream – an ideal rooted in freedom, equal opportunity, and upward mobility.Footnote 1 Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin’s striking claim that the American Dream may be “achieved best in the Nordic countries” invites us to examine how American and Nordic capitalism translate shared aspirations into very different realities. In doing so, we explore contrasting views of freedom, the role of public institutions, and what it takes to make opportunity real for all.

Isaiah Berlin’s distinction between negative and positive freedom is central to understanding these differences. This framework helps us analyze how different forms of capitalism balance individual liberty and societal well-being. Negative freedom refers to “freedom from” – the absence of interference, particularly from government regulation or taxation. Positive freedom, by contrast, is “freedom to” – the ability to access opportunities or essential services such as healthcare, paid parental leave, or affordable education.

In his 2024 book On Freedom, Timothy Snyder observes, “Negative freedom is our (American) common sense.”Footnote 2 Nordic societies, by contrast, prioritize expanding positive freedoms.Footnote 3

Conflicts between negative and positive freedoms arise when expanding one requires limiting the other. For instance, ensuring universal access to clean water – a positive freedom – may require regulations restricting businesses’ negative freedom to operate without interference. Similarly, funding universal healthcare through taxation requires balancing the negative freedom from taxation with the positive freedom of universal access to care.

Examining how American and Nordic societies navigate the balance between negative and positive freedoms – and whose freedoms take precedence in moments of conflict – offers a powerful lens for understanding the defining characteristics of American and Nordic capitalism, respectively. This theoretical framework of negative and positive freedoms has been widely applied in political philosophy and institutional analysis,Footnote 4 providing a useful conceptual framework for comparing different varieties of capitalism.

The American Dream

Few expressions are as widely known, frequently invoked, and open to interpretation (and exploitation) as the “American Dream.” It has been a central theme in some of the most impactful pieces of American rhetoric, from Martin Luther King Jr.’s impassioned “Letter from Birmingham Jail,”Footnote 5 to the speeches of President Reagan.Footnote 6 “Has the American Dream Been Achieved at the Expense of the American Negro?” served as the title for the legendary 1965 debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley.Footnote 7 This question underscores the deep complexities and varied interpretations of the American Dream, highlighting its role as both an aspirational ideal and a subject of scrutiny.

The expression “American Dream” is not confined to the US, as indicated by the Finnish Prime Minister’s opening quote, but its definition is subject to debate. Insofar as the American Dream represents the promise of a good quality of life for current and future generations, it is consistent with sustainable development. However, the American Dream has many different connotations.

So, what exactly is the American Dream?

Jim Cullen describes the American Dream as the US “national motto” – a set of ideals promising that anyone, regardless of background, can realize their potential through hard work. At its heart are freedom, upward mobility, and equal opportunity.Footnote 8

The expression American Dream was first penned in 1931 by James Truslow Adams. He described it as “life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.”Footnote 9 Adams continued, describing how the American Dream was a worldwide source of inspiration, stating, “a better, richer, and happier life for all our citizens of every rank, which is the greatest contribution we have made to the thought and welfare of the world. That dream or hope has been present from the start [of the US].”Footnote 10

Inherent to the American Dream is a sense of optimism – a profound hope that has deep historical roots. Within his famed Democracy in America manuscript from the 1830s, the Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville wrote “the charm of anticipated success” was a central quality of the young US. While the American Dream as a term did not rise in popularity until a century later, Tocqueville had tapped into the “can do” spirit of the American ethos that he did not experience in Europe at that time where monarchies and aristocracies predetermined the lot in life at birth for most people.Footnote 11

According to Cullen, the “major moral underpinning” of the American Dream is that “everyone is eligible … At some visceral level, virtually all of us need to believe that equality is one of the core values of everyday American life, that it promises to extend to everyone.”Footnote 12 “Everyone is eligible” does not require equality of outcome.Footnote 13 Instead, it means equality of opportunity for everyone to flourish and realize their full potential.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent challenged a more recent conflation of consumerism with the American Dream in a 2025 speech on trade policy. “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American Dream,” he declared. “The American Dream is rooted in the concept that any citizen can achieve prosperity, upward mobility, and economic security.”Footnote 14 His statement emphasized that upward mobility – not consumer access – defines the American Dream’s core promise.

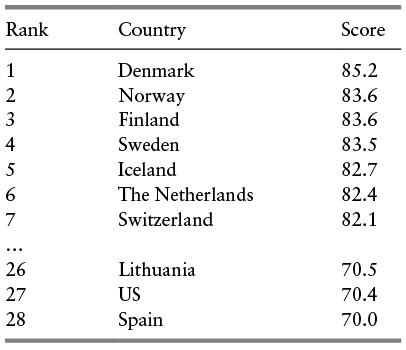

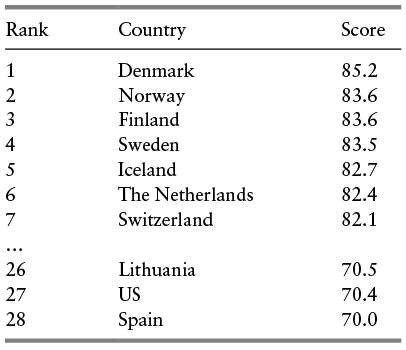

This focus on social mobility aligns with WEF’s Global Social Mobility Index, which measures precisely what the American Dream promises: equality of opportunity. The index evaluates how effectively different nations deliver “equally shared opportunities” and ensure “an equal and meritocratic footing irrespective of socio-economic background, geographic location, gender or origin.”Footnote 15 The WEF’s Global Social Mobility Index could justifiably be called the American Dream Index – yet ironically, the Nordic countries top the list, with the US ranked 27th, between Lithuania and Spain.

In the WEF’s 2020 report, all five Nordic countries claimed the top spots, with Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, and Iceland ranking first through 5th, respectively, as shown in Table 7.1. The US, by contrast, ranked 27th.Footnote 16 These findings are reinforced by researchers Mattia Fochesato and Samuel Bowles, who conclude that “in terms of economic and social success, it matters less who your parents are in the Nordic economies” – suggesting that Nordic capitalism may be more effective than American capitalism at delivering on the American Dream’s central promise of opportunity for all.Footnote 17

Table 7.1Long description

Table has three columns that list the Rank, Country, and Score. The top seven-ranked countries are as follows. Denmark: rank 1, score 85.2. Norway: 2 and 83.6. Finland: 3 and 83.6. Sweden: 4 and 83.5. Iceland: 5 and 82.7. The Netherlands: 6 and 82.4. Switzerland: 7 and 82.1. The table then skips to ranks 26 through 28, which are as follows. Lithuania: 26 and 70.5. United States: 27 and 70.4. Spain: 28 and 70.0.

While equality of opportunity is the focus of the American Dream – not equality of outcome – the two are related. When power and wealth become hyper-concentrated in society, and the gulf between rich and poor widens beyond a reasonable range, equality of opportunity can become compromised, and the American Dream is not a reality for everyone.

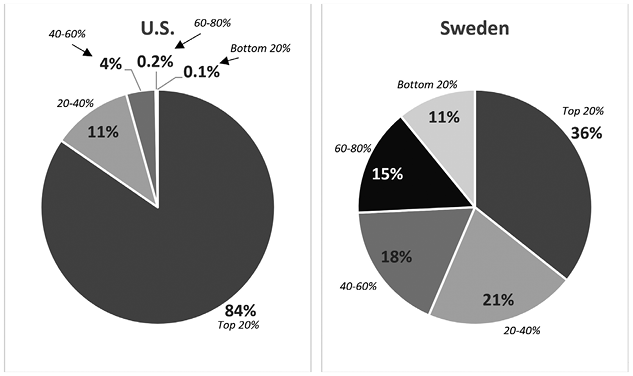

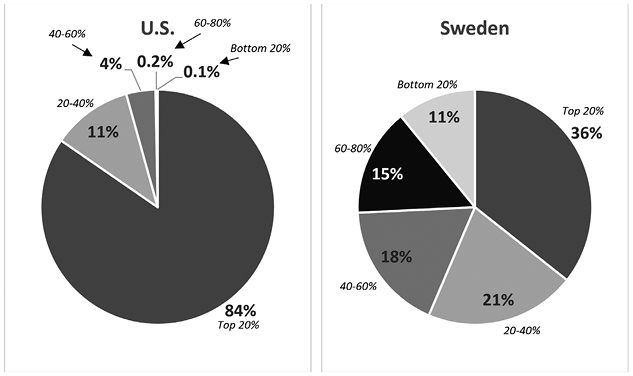

What is a reasonable range of economic inequality? When researchers Michael Norton and Dan Ariely presented actual levels of wealth inequality by country to US residents, as depicted in Figure 7.1, but without revealing the country’s name. Of the respondents, 92 percent expressed preference for the level of wealth inequality that corresponded to Sweden. Only 8 percent expressed a preference for a level of wealth inequality in the US.Footnote 18 Their 2011 study, published in Perspectives on Psychological Science, represented the first large-scale empirical investigation of Americans’ preferences regarding wealth distribution compared to actual levels of inequality.

Figure 7.1 Share of wealth by quintile: US and Sweden.

Figure 7.1Long description

Figure presents two pie charts comparing the distribution of national wealth across five income quintiles in the United States and Sweden. In the U.S. chart, the top 20% of earners hold 84% of the total wealth. The next 20% is in the second quintile, which holds 11%, followed by 4% for the middle quintile, 0.2% for the fourth quintile, and just 0.1% for the bottom 20%. In stark contrast, Sweden’s chart shows a more even distribution: the top 20% holds 36%, the second quintile holds 21%, the middle quintile holds 18%, the fourth quintile holds 15%, and the bottom 20% holds 11%. The visual highlights the extreme concentration of wealth in the U.S. compared to Sweden’s more equitable distribution.

In an Atlantic article titled “Americans Want to Live in a Much More Equal Country (They Just Don’t Realize It),”Footnote 19 Ariely explained how the vast majority of people in the US, regardless of political affiliation, income, and gender, prefer a distribution of wealth that “is very different from what we have and from what we think we have.” He writes:

Americans are actually in agreement about wanting a more equal distribution of wealth. In fact, the vast majority of Americans prefer a distribution of wealth more equal than what exists in Sweden, which is often placed rhetorically at the extreme far left in terms of political ideology – embraced by liberals as an ideal society and disparaged by conservatives as an overreaching socialist nanny state.

The US and Sweden each have significant levels of inequality, but strikingly different is that the bottom half of US citizens have virtually nothing. In contrast, the bottom half of Swedish citizens are doing okay. Norton and Ariely’s figure above shows that the bottom 40 percent of US citizens hold 0 percent of the nation’s wealth.

Extreme inequality in the US is not by accident but is the result of deliberate policy choices. During the Reagan administration, US tax rates were slashed in the 1980s, disproportionately for the wealthiest US citizens. The result is that the middle and lower economic classes paid a much more significant percentage of taxes in the US than before.

The neoliberal ideology presented a promise of “trickle-down economics,” implying that cutting taxes for the richest will spur economic growth, boost employment, and therefore flow down to the benefit of many people. However, the promise is proven untrue. In their 2022 Socio-economic Review paper “The Economic Consequences of Major Tax Cuts for the Rich,” David Hope and Julian Limberg show that in OECD nations from 1965 to 2015, tax cuts for the wealthiest lead to higher income inequality in the short and medium term, and do not have a significant effect on spurring economic growth or reducing unemployment as promised. They summarize, “Our results therefore provide strong evidence against the influential political–economic idea that tax cuts for the rich ‘trickle down’ to boost the wider economy.”Footnote 20

In the US, tax policies have increasingly been shaped by wealthy interests operating outside democratic accountability. Through strategies like “Buy, Borrow, Die” and specialized loopholes, wealthy individuals can leverage tax-advantaged investments and asset-based borrowing to reduce their tax rates to near zero, facilitating massive wealth transfer across generations. This system, designed through lobbying and political influence rather than democratic deliberation, undermines both economic efficiency and democratic governance.Footnote 21

US tax policies have created numerous loopholes that enable wealth concentration and intergenerational transfer with minimal taxation. A striking example is Harold Hamm, who in 2022 transferred over $11 billion to his children largely tax-free through carefully structured transactions that avoided the 40 percent estate tax.Footnote 22 Such legal maneuvers, available only to the wealthiest, demonstrate how US tax policy undermines equality of opportunity.

The American Dream narrative is powerful – and one many US residents hold as central to the American identity. However, it can be exploited by a powerful few who leverage it as mythology without supporting it with the concrete actions necessary to make it a reality for every American.

“If Americans want to live the American Dream, they should go to Denmark,” remarked Richard Wilkinson, summarizing the data he and Kate Pickett analyzed for their book, The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger.Footnote 23 Whether in Denmark, Sweden, or anywhere else in the Nordics, the evidence is compelling that most people in the US prefer the Nordic reality – they do not know it.Footnote 24

Freedom

“The American Dream is closely bound up with freedom,” wrote Cullen.Footnote 25 The expression “Land of the Free” is enshrined in the US national anthem, followed immediately by “and the home of the brave,” indicating that freedom and the courageous fight go hand in hand. In the US, freedom is commonly discussed in terms of freedom from some enemy – whether that enemy is represented by a foreign threat or domestic intrusion.

In the Nordics, however, freedom is not often discussed in terms of fighting and achieving freedom from some imagined enemy; rather, it is more commonly discussed in terms of freedom to do something. That is not to say Nordic nations do not understand the reality of bloodshed. During the twentieth century, roughly the same number of Finns died fighting the Soviet Union as US citizens died fighting in Korea and Vietnam (and Finland is only one-sixtieth the population of the US).Footnote 26 However, freedom is more likely discussed in the Nordics as something enabled through systems like universal education, healthcare, paid parental leaves, and support for older adults, which represent foundational elements of the Nordic model.

The Nordic approach to freedom is perhaps best illustrated through the considerations of children. Children in Nordic societies often experience a significantly higher level of freedom and independence than their counterparts in the US, reflected in various aspects of their daily lives and the social policies that support these freedoms. Children across Nordic societies commonly have the freedom to walk or bike to school and play outside unsupervised from a young age. These freedoms are enabled by safe, well-planned urban environments with bicycle lanes separate from car lanes. In contrast, concerns about safety and a more car-centric culture in the US often mean children are less likely to experience these freedoms. Nordic countries provide heavily subsidized childcare and preschool programs to ensure all children can access early childhood education. Relatedly, Nordic countries are known for their generous parental leave policies, allowing parents to spend significant time with their children during the early years without risking financial instability. Nordic countries’ comprehensive social welfare systems provide a safety net that includes healthcare, education, and social services that contribute to a society where children, regardless of their family’s financial status, can access services that ensure their well-being and development.

Ensuring the freedoms of future generations demands we consider future generations as part of the “We.” Nordic pro-business politicians and business leaders embrace the responsibility to consider future generations. Danish parliamentary and cabinet member Marie Bjerre, member of the pro-market, pro-business political party Venstre, stated in 2022, “I believe fighting for the climate is core to [pro-market, pro-business] politics. Because fighting for a better climate is part of a freedom agenda. It is about fighting for freedom and giving the same possibilities we had to the next generation. Also, it is our duty to not leave a heavy climate debt to the next generation.”Footnote 27

Former Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme (1969–1976, 1982–1986) emphasized that expanding freedom for every member of society was the foundational rationale for building the Nordic model. While speaking at Stanford University in the US in 1977, he explained:

I am speaking here today as a Swedish social democrat … We regard ourselves as a freedom movement … To us freedom means the removal of obstacles for the individual to develop her or his personality, the removal of injustices that quench our best yearnings for a better future, to quote one of my predecessors. We stress common responsibility and a sense of community above egoism and rugged individualism.Footnote 28

Freedom is not just an American ideal but also a Nordic one. However, views on how freedom is best enabled are dramatically different in the US than in the Nordics.

Nordic Theory of Love

Freedom is necessary to experience authentic love and friendship. This idea is the heart of the Nordic Theory of Love, a concept first articulated by Swedish scholars Lars Trägårdh and Henrik Berggren as the Swedish Theory of Love and later expanded by Anu Partanen to the Nordic Theory of Love (Chapters 4 and 6).Footnote 29 Trägårdh and Berggren’s Swedish Theory of Love argues that Swedes, while fiercely individualistic, achieve freedom through state support rather than family dependency.Footnote 30

Freedom is not achieved alone; we almost always depend upon support from elsewhere to secure freedom. Trägårdh and Berggren’s theory is that Swedes achieve individual freedom by combining the individual and State. This “statist individualism” can be seen in the State programs – healthcare, education, and so on – that Nordic countries hold as freedom enablers for the individual.

US citizens, by contrast, commonly achieve freedom through their families. Accessing healthcare and education in the US is often secured through one’s family, such as getting healthcare through a parent or spouse’s healthcare plan or relying upon a parent to pay tuition. In the States, women’s freedoms are also diminished by tending disproportionately to the home and childrearing; in the process, women become increasingly financially dependent on the men in their families. We could extend Trägårdh and Berggren’s nomenclature to call the US approach “familistic individualism,” where the individual secures freedom through one’s family.

Living in the US shaped Trägårdh’s view that the absence of social safety nets makes many US residents excessively dependent upon their families – parents, husbands, or rich uncles. Trägårdh and Berggren stress how freedom-limiting the US approach is for individuals, particularly those who do not win the birth lottery.Footnote 31

“Americans talk so much about freedom but have such little idea how little freedom they actually have,” a Danish exchange student told me at Copenhagen Business School. She was struck by how US students needed parental permission to change majors because their families paid tuition. “I can make my own choices without asking permission,” she noted, acknowledging that while Danes pay higher taxes for universal education, the freedom it provides is worth the cost. This contrast became vivid when I advised a UC Berkeley student to take the History of American Capitalism course. I said I thought he would appreciate the professor, who had authored the book Accounting for Slavery: Masters and Management.Footnote 32 He replied that the course sounded fascinating, but “My dad pays my tuition, and he would never let me take it.”

Before 1970, in-state students paid no tuition at University of California, Berkeley.Footnote 33 Fast forward fifty years, and four years of in-state tuition costs over $60,000.Footnote 34 UC Berkeley is a public university, but the financial burden has shifted to individual students paying increasingly higher tuition and widespread reliance upon philanthropic endeavors. (Reflecting upon her experiences as Chancellor of University of California, Berkeley, outgoing Chancellor Carol Christ remarked, “In the 1970s at Berkeley, there was no expectation that the chancellor was involved significantly in fundraising. Generally, we were generously supported by the state. Now, fundraising is probably the biggest part of my job.”Footnote 35) For most students, increased tuition means increased dependence on their families. For prospective students whose families cannot provide the necessary support, the choice is to either take on significant debt or forego attending a university altogether.

When parents fund their adult children’s education and expenses, the relationship transforms from one of guidance to patronage, often extending into middle age. This financial dependency, coupled with potential future inheritance, can turn family relationships into transactional negotiations. Whether one acknowledges it or not, the freedom achieved through dependency upon family charity is a reality of US life. In contrast, the Nordic focus has been on expanding freedom for everyone, irrespective of family, and honestly acknowledging that we do not secure freedom entirely by ourselves.

Freedom: Positive and Negative

Few thinkers have contributed more to ideas about freedom than Latvian-born theorist Isaiah Berlin. Berlin’s family moved to Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1909 when he was six. Witnessing the events of the 1917 October Revolution from their apartment window and feeling increased oppression as the Bolsheviks ascended to power, Berlin’s family later left for England in 1921.

As discussed earlier, Berlin’s distinction between negative and positive freedom provides a valuable lens. The Nordic model’s expansion of positive freedom – access to education, healthcare, childcare, and the natural world – underscores its alignment with Berlin’s trajectory of positive liberty.Footnote 36 The continued expansion of positive freedoms is the foundation of the Nordic model. The “core of Nordic modernity,” wrote Bo Stråth in Egalitarianism in Scandinavia, “mainly follows Berlin’s trajectory of positive freedom.”Footnote 37

Through democratic processes, Nordic societies establish and maintain efficient universal systems that ensure citizens’ access to essential services such as medical care and education. These systems are funded through income taxes supported by vibrant market economies, demonstrating how democracy and capitalism can work hand in hand. Democratic oversight helps keep these systems efficient and accountable while expanding positive freedoms for all citizens. This practical coupling of democratic processes with market dynamics makes Nordic societies powerful examples of democratic capitalism in action, increasing the likelihood that more citizens can flourish.

Positive freedom extends into property rights in the Nordics. Given how central property rights are to capitalism, this merits particular attention. Allemansrätten (Swedish) or Allemannsretten (Norwegian) translates to “everyman’s right,” referring to laws across the Nordics that ensure everyone has the freedom to hike, camp, and forage for berries and mushrooms on all lands, including privately owned (provided you stay five hundred feet from anyone’s home).

Also known as freedom-to-roam laws, the official website of Visit Norway explains, “The main rules are easy: Be considerate and thoughtful. Don’t damage nature and other surroundings. Leave the landscape as you would want to find it.” to roam represents “a traditional right from ancient times, and from 1957 it has also been part of the Outdoor Recreation Act. It ensures that everybody gets to experience nature, even in larger privately owned areas.”Footnote 38 In 2017, Sweden listed the entire country on Airbnb – bookable without fee – thanks to its constitutional right to roam. This stands in sharp contrast to US signage threatening violence against trespassers, revealing radically different views on property and public access.Footnote 39

The expansion of the freedom for everybody to roam entails a reduction of negative freedom for landowners whose freedom from having people roam on their land.Footnote 40 The tradeoff that Nordic societies have accepted is that the expansion of positive freedoms for everybody is worth a reasonable reduction of negative freedoms for property owners. In stark contrast, Walmart sells signs in the US stating, “No Trespassing. No Soliciting. Violators will be shot,”Footnote 41 and “Private Property. No Trespassing. We do not call 911,” with an image of a gun, heavily implying that property owners have the freedom to shoot (and kill) anyone who comes onto their property.Footnote 42 Such signs would be absurd in the Nordics and considered a gross violation of custom and law.Footnote 43

In contrast, the US has focused primarily on expanding negative freedoms throughout its history. Freedom in the US is frequently prioritized for individuals with power and property. Stråth writes, “the American dream of a society of equals often came close to the negative freedom as defined by Berlin … negative freedom is the freedom to do whatever one wants and becomes in the end a question of power.”Footnote 44 In Berlin’s words, “freedom for the wolves has often meant death to the sheep.”Footnote 45

There’s US history to consider, where the freedom to own another human being as property represented one of the most egregious examples of expanding negative freedom for a powerful few. When slavery was legal in the US, slavery advocates argued that abolishing slavery violated slaveholders’ freedom. The pro-slavery position supported the expansion of negative freedom for owners of slaves, advocating that they should have freedom from being interfered with by others to own human beings as property (consistent with the proprietarian ideology laid out in Chapter 4). Of course, such a position required a complete disregard for the freedoms of enslaved people.Footnote 46 Tocqueville observed the propensity in the young US to grant an expansion of negative freedom for the powerful few, even at the cost of eradicating freedoms for others: “They want equality in liberty, and if they cannot have it, they still want it in slavery.”Footnote 47

When assessing the claim that the US is the freest nation in the world, one could also ask freedom for whom?

Returning to the contentious matter of guns, Adults in the US have considerable freedom to own military-grade assault weapons, like the AR-15. Gun rights advocates in the US often frame the issue in terms of freedom from a tyrannical government, invoking an excerpt from the Second Amendment, “the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.” Upon turning eighteen, the age of adulthood in the US, the Uvalde killer legally purchased two AR-15-style weapons that he used in the killings just two days later.

Adults in Nordic nations have the freedom to own guns – just not military-grade weapons. Finland routinely ranks among the highest levels of gun ownership in the world, with 32 guns per 100 people. Norway is close behind with 29 guns per 100 people. (The US consistently ranks first in the world with 120 guns per 100 people.Footnote 48) However, civilian ownership of military-grade weapons is illegal across all Nordic nations. Therefore, adults in the Nordic nations have comparatively less freedom than their American adult counterparts to own and shoot military weapons as civilians.

However, concerning children, given the comparatively few military-grade weapons in circulation among Nordic citizens, children in Nordic nations enjoy greater freedom to go to school without fear that military-grade weapons could be present. The concept of freedom for children in a school setting usually involves a safe environment for learning and personal growth. Therefore, children in the US enjoy comparatively less freedom in this regard. Active shooter drills are now commonplace across US schools, resulting in increased anxiety, stress, and depression among children.Footnote 49 In this case of considering freedom for whom, the US appears to effectively prioritize the freedom of adults to own military-grade assault weapons, and the Nordics appear to effectively prioritize the freedom of children to live without fear of encountering military-grade assault weapons.

Leaky Buckets: Reducing Negative Freedom

Taxes represent a reduction in negative freedoms, as they are mandatory, reducing one’s freedom from coercion. Economists have long used a “leaky bucket” metaphor as a visual for how collecting taxes addresses issues of inequality, implying that all efforts to address inequality inevitably result in inefficiencies.

According to Arthur Okun (Chapters 2 and 3), efficiency is reduced when individuals receive universal benefits because they now have reduced incentives to work. The individuals paying increased taxes have reduced incentives to work since high taxes mean they keep less money. Additionally, administrative efforts must collect the taxes and direct the collected tax revenues wherever they go. According to Okun, collecting taxes to address inequality will always reduce efficiency, just as water is continuously lost from a leaky bucket.Footnote 50

The leaky bucket metaphor has had significant staying power, influencing how US economists think about inequality and the role of taxes in the US.

Efficient Hand Pumps: Increasing Positive Freedom

The leaky bucket metaphor fails to acknowledge that inequalities, when allowed to grow excessively, can impose their own efficiency costs on society. Trickle-down economics has also been extensively evaluated and found unsupported by empirical evidence. As Robert Reich summarizes, “Trickle-down economics is a cruel hoax.”Footnote 51

An “efficient hand pump” is a counter-metaphor to the leaky bucket, and this one is more suitable for describing the Nordics. A leaky bucket implies a subservient relationship, where the poor continually depend upon the rich to bring them water (and much water will be spilled along the way). In contrast, an efficient hand pump represents a commitment to increasing the freedom of individuals who can pump their water without dependency upon others. Installing and maintaining efficient hand pumps throughout society increases freedom for individuals who work hard to get their own water. The efficient hand pump metaphor aligns with insights from institutional economics, which demonstrate that well-designed universal systems can improve efficiency across society. Figure 7.2 contrasts two metaphors – the leaky bucket and the efficient hand pump.Footnote 52

Figure 7.2 Leaky bucket versus efficient hand pump.

Figure 7.2Long description

Image shows two line drawings placed side by side. On the left is a wooden bucket with two handles; water is leaking from a hole near the base, forming a puddle beneath it. On the right is a manual hand pump with a curved handle and a spout, from which a single drop of water is falling. The background is blank.

This metaphor can be extended further: Imagine if every individual had to dig their own well and install their own handpump to access water. Some would succeed through tremendous individual effort, while others might fail despite working equally hard due to hitting bedrock or lacking proper tools. Meanwhile, some individuals inherit fully functioning wells from their families, allowing them to access water with minimal effort. Those with inherited wells might look down on others struggling to build theirs, labeling them as lazy or undeserving – ignoring the vast difference in starting positions.

This scenario mirrors how many Americans access essential services, such as healthcare and education. Some must build their access from scratch, often facing nearly insurmountable obstacles, while others inherit access through family wealth and connections. The resulting system is not only deeply inefficient at a societal level – with countless individuals expending enormous effort to duplicate infrastructure – but it also undermines the American Dream’s promise of equal opportunity. Just as it would be more efficient to build a water system serving everyone, universal access to education and healthcare through public systems represents a more efficient approach than requiring each individual or family to secure access independently.

When the expressed purpose for collecting taxes is to expand positive freedoms for all citizens to access such essential services as medical care and education, and taxes are used efficiently to achieve said purposes, the overall societal-level efficiencies can be increased.Footnote 53 In these cases, a society may willingly choose a reasonable reduction in negative freedom (paying higher taxes) to secure a meaningful increase in positive freedoms (access to medical care and education).

Nordic citizens expect the value of the services they access will outweigh the taxes they pay. Nordic societies are responsive to citizens. Should citizens reject “leaky hand pumps” (i.e., if a service or program were inefficient), it must be improved or eliminated.

Universal access to education through university for all Nordic citizens has proven an efficient hand pump. Universal access to quality healthcare paid parental leave, and subsidized childcare ensures every child gets a good start, expanding their positive freedoms. Access to medical care – including preventative care – is an efficient hand pump to ensure sustained health that will serve the individual well into the future. (Finland’s under-five child mortality rate is 1.7 per 1,000 live births – the lowest in the world; the US is 6.53.Footnote 54)

The Nordic model can be seen as a collection of efficient hand pumps positioned throughout society that all citizens have the right to access. Nordic societies’ universal services result in efficiency gains at the societal level.

In the Nordics, the State is expected to expand the positive freedoms of every citizen. The state is discussed as an extension of the Nordic people, a mechanism for coordinating efforts and establishing efficient systems to address problems more significant than any individual or local group can effectively address. In the US, the State is characterized as the enemy, which has the impact of diminishing the negative freedoms of its citizens.

I have realized that many people in the US do not realize how inefficient US society is. US citizens often accumulate overwhelming out-of-pocket costs in the march toward paying fewer taxes. People still need healthcare and education, and US citizens pay for these services at levels higher than citizens of other nations pay in taxes. Partanen summarized:

All this talk of tax rates is primarily meaningless unless we spell out what people get in return for their money. The very high-quality and reliable services that Nordic citizens get in return for their taxes – including: universal public healthcare, affordable day care, universal free education, generous sick pay, year-long paid parental leaves, pensions, and the like – can easily incur additional tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of dollars in after-tax expense for Americans.

Bottom line: For middle-class people, the amount of disposable income you end up with in the United States versus in a Nordic country can be very similar in the end, or even turn out to be a better deal in a Nordic country.Footnote 55

Partanen’s words echo those of Olof Palme, who contrasted Swedish experiences with the US while speaking at Stanford University in the 1970s.

We pay very high taxes, much higher than in the US. But when I hear what you have to pay to keep your children in college or for a hospital bill, I sometimes wonder whether the difference is so large, after all. It is easy to claim that taxes are a limitation of personal freedom. But again, you face the question of whose freedom? In order to answer that question, you have to investigate for what purposes the revenue is used.Footnote 56

Public Libraries as Efficient Hand Pumps

Public libraries offer a clear example of an efficient hand pump – modest public investments that yield substantial returns while expanding positive freedom. A meta-analysis of library valuation studies found that every dollar invested in public libraries returns approximately four dollars in benefits.Footnote 57 Capital investments in libraries have also been associated with measurable improvements in children’s reading achievement in nearby schools, representing a cost-effective means of supporting literacy and educational development.Footnote 58

Public libraries help fulfill the American Dream by offering universal access to books, the Internet, and educational resources – giving individuals the chance to put in the hard work of learning and take greater ownership of their future.

Nordic countries lead the world in public library investment, with Finland and Denmark routinely topping international rankings. “Scandinavian libraries are in a league of their own,” one journalist observed.Footnote 59 Helsinki’s Oodi Library exemplifies how such investments advance positive freedom. Situated directly across from the Finnish Parliament, Oodi offers books, recording studios, maker spaces, meeting rooms, and exhibition galleries – freely accessible to all. It functions as both a civic commons and a cultural hub: an open, democratic space where citizens of all backgrounds can access tools for learning, creativity, and community engagement.

While bicycling through Copenhagen with Danish Minister of Transportation Benny Engelbrecht in 2022, we passed a local library where he paused to reflect on his childhood. Raised in a family of modest means, he recalled spending countless hours inside, reading everything he could. That library, he said, opened up his world and set him on the path to becoming a Minister in the Danish Parliament. His story is one of many that illustrate how public libraries function as efficient hand pumps – institutions that offer every child, regardless of background, the opportunity to explore, learn, and imagine new possibilities. Nordic societies invest heavily in universal access to institutions like public libraries that advance the promise of the American Dream for more children and citizens.

Beyond demonstrating the efficiency of public investment, libraries also challenge the notion that state involvement inevitably crowds out private enterprise. Though publicly funded, Nordic libraries have not diminished private book ownership or undermined the publishing industry. On the contrary, Nordic households are often filled with books, and the region’s publishing sector remains robust. Public libraries ensure universal access while preserving individual choice – citizens can rely on public services and build personal collections, while the private publishing market thrives.

This familiar example of library access illustrates the pragmatic blend of public and private efforts in Nordic universal healthcare. Just as individuals may borrow books from a public library while purchasing their own for their private collection, Nordic citizens have access to publicly funded healthcare and the option to buy supplemental private insurance. Universal access coexists productively with choice in the marketplace, establishing a shared foundation for all while allowing individuals to tailor services, whether in literature or healthcare, to their personal needs and preferences.

Corrosion of an Efficient Hand Pump: Public Universities in the US

Public universities are American Dream factories. Built through democratically accountable investments, public universities expanded opportunity for millions of Americans and generated the research that made the US a global innovation powerhouse in the twentieth century. Institutions like the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison became global talent magnets – educating millions while producing groundbreaking discoveries that shaped the world. These universities anchor larger public university systems – the University of California with ten campuses and the University of Wisconsin with thirteen – together educating millions who have realized the American Dream of upward mobility. I am one such beneficiary – a University of Wisconsin–Madison graduate who, now at the University of California, Berkeley, sees firsthand the opportunities these great public universities continue to provide.

Landmark research analyzing data from over 30 million college students found that public universities such as University of California, Berkeley, and University of Wisconsin–Madison rank among the most effective institutions for intergenerational economic advancement in US history.Footnote 60 The University of California, Berkeley, is a standout American Dream factory, enrolling large numbers of low-income and first-generation students and routinely welcoming community college transfers – a stark contrast to its private peers in the Ivy League. At the most elite private universities in the US, legacy status – often tied to parental alumni connections and financial contributions – increases an applicant’s odds of admission by more than threefold.Footnote 61 Public universities like UC Berkeley explicitly prohibit such practices, reinforcing their role as meritocratic engines of social mobility in contrast to the legacy preferences and donor-driven advantages that shape admissions at many elite private American universities.

Moreover, the research of public universities directly contributes to economic progress, creating conditions in which more individuals can realize the American Dream. A particularly striking example is UC Berkeley: Its innovations in science and technology were indispensable to the emergence of Silicon Valley as a global hub of innovation. Silicon Valley as we know it today could not have emerged without UC Berkeley.Footnote 62

Yet the efficient hand pumps of America’s public university systems are corroding, as decades of state disinvestment have forced many universities to rely increasingly on private funding and tuition hikes. In recent years, many US universities have also faced heightened federal political pressure that threatens to further erode what made the US a global innovation powerhouse and talent magnet.

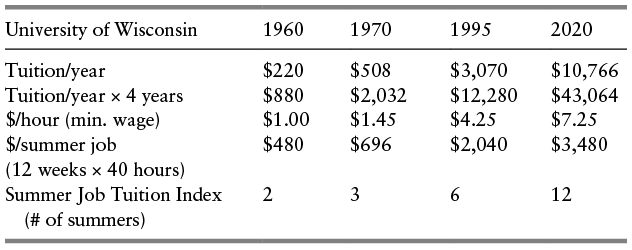

Summer Job Tuition Index: A Measure of Social Mobility

In 1960, a student could pay for four years at the University of Wisconsin–Madison with just two summers of full-time minimum-wage work. By 1970, it required three. When I attended in the mid 1990s, it took six summers – still within reach, as I worked full-time each summer from age sixteen through graduation and earned a degree with little debt. By 2020, however, the figure had doubled to twelve summers, as shown in Table 7.2, often resulting in dependence on one’s family or assuming significant debt. If current trends continue, by 2045, it will take twenty-four summers of minimum-wage work to cover the cost of four years of tuition.

| University of Wisconsin | 1960 | 1970 | 1995 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuition/year | $220 | $508 | $3,070 | $10,766 |

| Tuition/year × 4 years | $880 | $2,032 | $12,280 | $43,064 |

| $/hour (min. wage) | $1.00 | $1.45 | $4.25 | $7.25 |

| $/summer job (12 weeks × 40 hours) | $480 | $696 | $2,040 | $3,480 |

| Summer Job Tuition Index (# of summers) | 2 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

The steady rise of the Summer Job Tuition Index – the number of full-time summers at minimum wage required to pay for four years of in-state tuition – reveals the erosion of educational opportunity at America’s public universities and the narrowing of freedom for those without wealth.

As a student, I cleaned pit toilets at a Wisconsin state park during summer. It was unappealing work, but I chose it willingly because it allowed me to pay my tuition. A few years later, I was working as an industrial engineer at IBM. I was realizing the American Dream. That trajectory reflected the American promise: That hard work leads to upward mobility. Today, no amount of pit-toilet cleaning over summer breaks could generate enough income to cover tuition at most public universities.

By contrast, the Summer Job Tuition Index in the Nordic countries is effectively zero because public universities are fully funded through taxation. One can debate whether zero tuition is appropriate in the US context, but it is indisputable that access to public university education has become out of reach for many Americans.

Restoring credibility to the promise that hard work enables upward mobility requires lowering this index to a more reasonable level. This could be achieved through a combination of reduced tuition and higher wages. Had the minimum wage kept pace with US productivity growth from the 1960s to 2020 – as it had from the 1930s through the 1960s – it would have reached $21.45/hour by 2020 (see Chapter 3). The Summer Job Tuition Index would fall to four summers at that wage level. Combine that with a 50 percent reduction in tuition, and we would return to the two-summer level seen in 1960.

In recognition of the unsustainable nature of the current path, the University of Wisconsin introduced a tuition-free program in 2018 for students from families with annual incomes of less than $56,000. The initiative highlights key contrasts between American and Nordic approaches to higher education. Eligibility is based on family income rather than individual status, reflecting the US expectation that even adult students remain financially tied to their families. The program is also means-tested rather than universal – a model the Nordic countries abandoned in the 1950s to reduce stigma and protect social programs from political volatility. Finally, it is funded through philanthropy rather than public taxation, whereas Nordic nations treat higher education as a publicly funded good.Footnote 63

Deliberately Corroding Public Universities

The University of Wisconsin system illustrates the growing role of private funding in public higher education – and the corresponding erosion of democratic practices. Following political contributions from John Menard Jr. to Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker’s 2011 campaign, Walker enacted significant tax cuts that benefited Menard while sharply reducing public funding for the University of Wisconsin system. Soon after, the Menard Family Foundation and the Charles Koch Foundation emerged as major donors to the university. This sequence effectively transformed personal tax savings into privately directed university funding, accompanied by conditions that included influence over faculty hiring, curriculum content, and student data collection. These arrangements gave private donors unprecedented influence over academic discourse and institutional governance, further concentrating power in society.Footnote 64

The weakening of the University of Wisconsin system exemplifies how American capitalism is devolving into oligarchic capitalism, where wealthy private interests systematically undermine democratic institutions while expanding their control. This erosion is especially tragic given that public universities have long served as engines of social mobility.

A broader pattern emerges: private wealth first weakens public institutions through political influence and then reasserts control through philanthropic intervention. The cycle is instructive. Billionaire Menard used his wealth to influence political power by funding Governor Walker’s campaign. Walker, in turn, enacted tax cuts that favored Menards Corporation while slashing state support for public universities – a textbook case of concentrated wealth shaping public policy to entrench itself. Menard, alongside the Charles Koch Foundation, then returned as a philanthropist, offering a fraction of his tax savings back to the now-underfunded university system – but with strings attached. These included influence over curriculum and programming, shifting public universities further from their democratic mission.

The establishment of the Menard Center for Constitutional Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire in 2020 exemplifies this dynamic. Through the donation, Menard gained significant influence over the university’s academic programming. His stated intent was “to create new speaker forums and series that provide multiple points of view.”Footnote 65 Yet university officials are left to interpret the subtext: continued funding likely depends on ensuring that these “multiple views” align with the ideological preferences of major donors such as Menard and Koch. While no explicit quid pro quo is proven, the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire awarded Menard its first-ever honorary doctorate for “lifetime achievement” – a gesture that raises serious questions about the growing entanglement of donor influence.Footnote 66

Similarly, the Menard Center for the Study of Institutions and Innovation was established at the University of Wisconsin–Stout in 2019, again funded jointly by Menard and the Charles Koch Foundation. In 2022, the Center launched a system-wide survey on “First Amendment Free Speech Rights, Viewpoint Diversity, and Self-Censorship,” illustrating how privately funded initiatives can shape the terms of academic debate. Academic critics argued that the survey’s design appeared intended to produce findings that would justify further privatization of public education – culminating in the resignation of the University of Wisconsin–Whitewater’s chancellor in protest.Footnote 67

This incident reflects a broader pattern documented by scholars: Private funding of public universities often comes with conditions that shape faculty hiring, curriculum design, and institutional governance.

The divergent trajectories of American and Nordic capitalism are on full display. While American capitalism has increasingly evolved into an oligarchic model, where private wealth exerts growing influence over public institutions, Nordic democratic capitalism maintains institutional independence through robust public funding and democratic accountability. As Anand Giridharadas argues in Winners Take All, relying on philanthropic “winners” to fund essential public institutions poses a fundamental threat to democratic governance. The Nordic model offers an alternative: one in which transparent, tax-funded support ensures that public institutions serve the common good – not private interests.Footnote 68

Reliably Good Defaults Expand Freedom

The Nordic model provides reliably good default options – universal healthcare, high-quality education, safe transportation – that reduce stress and expand freedom. I could not fully appreciate the liberating effect of these defaults until I lived in the Nordics. In contrast, Americans have grown accustomed to constant anxiety, forced to fight for basic services that should be guaranteed.

When Finnish journalist Anu Partanen moved to the US, she described, “It’s hard to exaggerate how fundamentally the loss of health insurance destroyed my sense of personal security and well-being.”Footnote 69 Some might argue she had more freedom in America – she could “choose” from many insurance options – but the burden of navigating complex markets did not constitute freedom for Partanen. A lottery of poorly structured choices is no substitute for a well-designed, efficient default.

Psychologist Barry Schwartz’s The Paradox of Choice illustrates how excessive choice can overwhelm rather than liberate. Having to make constant decisions in complex systems – especially when opting out leads to personal or financial collapse – undermines freedom.Footnote 70 Few of us are healthcare experts or can reliably predict the risk of a family member getting sick or injured in the upcoming year. We are prone to select a plan that is too small (“I’m never going to get sick”) or too big (incurring excessively high premiums), depending upon our personality types and risk appetite.

Nudge Theory, developed by Nobel laureate Richard Thaler, demonstrates that well-designed defaults can improve outcomes without limiting choice. Automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans, for example, boosts long-term financial security while preserving individual freedom. Thaler and co-author Cass Sunstein argue that nudges promote better decisions at a systems level and expand individual freedoms.Footnote 71

The Nordics embed such nudges into daily life. In Copenhagen, even on rainy days, biking remains the most convenient form of transport because systems are designed to make it so. Exercise, health, and environmental benefits flow from infrastructure choices. Healthcare, too, is universal: Everyone has access to a solid baseline of care, and additional coverage is available on the market. Sarah and I chose the default, and it worked well – with no stressful insurance shopping required.

Creating good defaults requires systems thinking, democratic legitimacy, and economic efficiency. In Nordic societies, transparent public processes, not private interests, shape critical systems like healthcare and education. This ensures both effectiveness and trust. In contrast, the US often relies on market mechanisms that undermine democratic accountability and deliver suboptimal results. The Nordic experience shows that defaults, when designed thoughtfully with transparent, democratic oversight, can expand individual and societal-level freedom.

Freedom through Nordic Flexicurity

The Nordic model’s flexicurity system demonstrates how democratic capitalism can balance worker protection with economic dynamism. Unlike American capitalism, which often pits workers against employers, Nordic flexicurity emerged through democratic processes that recognize both as essential stakeholders. Its practical benefits become clear when comparing how different systems handle layoffs.

The 2008 PBS documentary Unnatural Causes illustrates how conceptions of “We” shape societal responses. When Electrolux closed factories in both Sweden and the US, the contrast was stark. Swedish workers received two years of paid retraining at 80 percent of their salary through coordinated programs involving government, unions, and employers. In Greenville, Michigan, American workers were left asking, “What happens to those people?” – a question that reveals the absence of collective responsibility.

Within months, many in the US faced depleted savings, lost health insurance, and growing uncertainty. One worker remarked, “I’ve always worked for everything I have, and now I can’t do anything.” In Sweden, where systems are built on what psychologist Rick Price calls “a sense of shared social responsibility,” workers transitioned to new careers and maintained stability.Footnote 72

A 2015 follow-up documented the long-term effects. Swedish workers had largely rebuilt their lives. Greenville, by contrast, was devastated – its downtown hollowed out, with former factory workers in low-wage retail jobs. The contrast highlights how Nordic flexicurity – by embedding economic adaptability within a framework of collective responsibility – better serves both individuals and society.Footnote 73

Trust: The Nordic Gold

The concept of social trust as institutional capital builds upon Putnam’s offerings on social capital and institutional performance,Footnote 74 providing a framework for understanding how Nordic societies maintain their distinctive form of capitalism.

“The Nordic region has the highest levels of social trust in the world, which benefits the economy, individuals, and society as a whole,” begins the 2017 Nordic Council of Ministers report Trust: The Nordic Gold by Ulf Andreasson.Footnote 75 This trust, built through democratic institutions and transparent governance, enables more efficient economic coordination while reinforcing democratic legitimacy – a virtuous cycle that distinguishes Nordic democratic capitalism from oligarchic forms.

The cooperative leadership norms (Chapter 5) and stakeholder-focused business practices (Chapter 6) both depend on and reinforce the high levels of trust that characterize Nordic societies. The Nordic model requires this foundation of trust to function effectively. This trust extends beyond individual relationships to encompass institutional trust – confidence in government institutions, businesses, and social systems. The high levels of transparency and democratic accountability discussed in previous chapters help maintain this institutional trust. Furthermore, the cooperative leadership norms explored in Chapter 5 both depend on and reinforce this culture of trust. “It is difficult to imagine societal models like those in the Nordic countries if citizens do not trust that other citizens also contribute to the economy through the tax system and that public authorities manage tax revenues fairly and efficiently, free from corruption.”Footnote 76 Andreasson succinctly summarizes a challenge for US citizens peering at the Nordic model to consider what lessons may be drawn.

The Nordic model builds trust among its residents. Universally subsidized childcare means every child can access high-quality childcare, regardless of their family situation. And because of it, children from families of very different backgrounds and means are more likely to be together. Because of that, parents from very different backgrounds and different means are more likely to come together and connect through the common project of their children’s well-being. In Nordic countries, children whose parents are corporate CEOs, janitors, unemployed persons, or university students can likely be in the same childcare program because of universally subsidized childcare. Through their daily interactions at drop-off and pickup and friendships with their children, these individuals from very different places can get to know one another and build trust, strengthening the social fabric of society.

Rawls and Nordic Capitalism

Nordic capitalism reflects many of the philosophical principles articulated by John Rawls, one of the twentieth century’s most influential political theorists.Footnote 77 Rawls’ central argument – that a just society must be designed as if we did not know our position within it – reflects Nordic institutional arrangements. His famous “veil of ignorance” thought experiment, where individuals design rules without knowing whether they will be born rich or poor, advantaged or disadvantaged, offers a powerful normative justification for universal programs and broad-based opportunity.Footnote 78

The veil of ignorance can also be understood as a philosophical rendering of the American Dream. At its core, the American Dream promises that anyone – regardless of background – should have a fair chance to fulfill their potential through hard work and determination. Rawls’ framework simply asks for the design of a society that delivers on that promise. The Nordic countries, in many ways, come closer to realizing this vision than the US itself. His framework also provides moral grounding for sustainable capitalism through its implications for intergenerational justice: designing policies and institutions behind a veil of ignorance means accepting the possibility of being born into the future – into a world facing the escalating consequences of climate change.

Rawls described a just society as a “property-owning democracy” – a vision that shares core features with democratic capitalism, but with a stronger emphasis on preventing the concentration of wealth and power. In such a system, economic power and opportunity are widely dispersed rather than concentrated in the hands of a few.Footnote 79 Nordic capitalism reflects this vision, emphasizing universal public goods, robust education systems, social mobility, and corporate forms like enterprise foundation-owned companies that diffuse economic control and prioritize long-term societal benefit over shareholder primacy. In doing so, it expands the circle of “We” to include current stakeholders and future generations.

Parting Reflections

The American Dream is a defining mythology of the US, though the extent to which it reflects reality remains subject to debate. It offers a powerful potential to unite society around shared aspirations, but this potential depends on how effectively the Dream is translated into concrete institutions that support social mobility and the broader conditions associated with opportunity and flourishing.

The Nordic region, too, has its own mythologies. In Denmark, Norse mythology helped shape national identity, most notably through the influence of Grundtvig. His enduring articulation of “freedom for Loke as well as for Thor,” from his 1832 poem “Frihed, Lighed og Brodersind” (“Freedom, Equality, and Brotherhood”), captures the tension between negative and positive freedoms that Isaiah Berlin would later theorize. Drawing from Norse mythology, Grundtvig invoked Thor, a symbol of strength and order, alongside Loke, a figure of disruption and relative weakness, to argue that true democracy must protect both the powerful and the dissenting. Freedom, he insisted, must extend across the full spectrum of society. His vision reflected a sophisticated balance: safeguarding negative freedoms by protecting dissenting voices, while building robust institutions that expand positive freedoms for all – thus fostering a collective sense of We.Footnote 80

The Nordic countries’ success in realizing Grundtvig’s inclusive vision stands in stark contrast to recent American experience. American capitalism has increasingly narrowed its sense of We by prioritizing negative freedoms that benefit the powerful few, often dismissing efforts to reduce inequality as inefficient “leaky buckets.” In contrast, Nordic societies have expanded their sense of We through universal systems that promote positive freedoms. Like efficient hand pumps, these systems enable all citizens to independently access essential resources such as education and healthcare, prompting deeper reflection on the meaning of freedom and how it might best be expanded for all.

Making the American Dream an American reality – and truly fulfilling the promise of the US as the Land of the Free – requires institutions that foster positive freedom, advancing both individual opportunity and collective well-being. Public universities like the University of California, Berkeley, University of Wisconsin–Madison, and many others across the US have served as American Dream factories, propelling millions of low-income students into higher economic brackets while attracting top talent from around the world. Yet their ongoing erosion offers a cautionary tale.

The Nordic experience shows how national mythology, when grounded in strong inclusive institutions and coupled with a commitment to pragmatically doing the hard work, can transform aspirational ideals into meaningful opportunity for all citizens.