Policy Significance Statement

The extension of AI applications into government services necessitates understanding user motivations for these services. Policy needs to be aligned with these applications to ensure the successful integration of AI technologies into society. The study highlights some essential factors (knowledge building, attitudinal refinement, and discomfort elimination) as important areas around which policymakers can formulate policies to successfully integrate AI-enabled government services into the fabric of emerging economy societies. Policymakers can therefore leverage AI education strategies at all levels to improve users’ understanding of AI, which is an important pathway to adoption. Eliminating areas of discomfort through AI in government services is an important avenue, as it can dispel insecurities and drive adoption. Policies that enforce usability and trust in these services must be pursued to drive adoption.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has, in recent years, rapidly transformed from a nascent technological innovation to an essential everyday resource (Bryson, Reference Bryson and Misselhorn2015; Mehr et al., Reference Mehr, Ash and Fellow2017; Holmström, Reference Holmström2022; Bressler and Bressler, Reference Bressler and Bressler2024). AI technology has become an important resource transforming various sectors globally, from the private sector to public sector service delivery (Desouza et al., Reference Desouza, Dawson and Chenok2020; Schiff et al., Reference Schiff, Borenstein, Biddle and Laas2021). Institutions across the globe, including government institutions, recognise the potential of AI to enhance the efficiency, accuracy, and responsiveness of service delivery to consumers (Dafoe, Reference Dafoe2018; Margetts, Reference Margetts2022). Private-sector focus on AI technology use is often driven by profit-seeking, innovation for competitiveness, and market-expansion goals (Bonde and Nyakora, Reference Bonde and Nyakora2023; Bressler and Bressler, Reference Bressler and Bressler2024). In the public sector (government services), AI is leveraged to achieve efficient service delivery, transparency, extended reach, and the public good (Mehr et al., Reference Mehr, Ash and Fellow2017). Government entities across developed economies are leveraging AI to enhance service delivery, policy formulation, and citizen engagement, highlighting a shift in how public services are managed and delivered (Wirtz et al., Reference Wirtz, Becker and Langer2023). Applying these AI solutions in government services has yielded mixed results (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Guo, Gao and Liang2021; Iong and Phillips, Reference Iong and Phillips2023). The benefits primarily relate to AI’s ability to advance development in countries but also point to issues relating to talent, which are the skills needed to develop and maintain AI technologies, as well as user privacy, which can influence the decision to adopt AI in government services (Kinkel et al., Reference Kinkel, Baumgartner and Cherubini2022). This highlights an essential area of enquiry into the driving factors of AI adoption and use.

Despite the global growth in AI adoption, emerging economies, such as Ghana, are consumers/procurers of AI technologies from foreign countries, lacking their own developed solutions or infrastructure to support them. Emerging economies, therefore, remain at the infantile stages of AI integration into government services (Addy et al., Reference Addy, Asamoah-Atakorah, Mensah, Dodoo and Asamoah-Atakorah2024). The disparity in AI adoption between developed and emerging economies can be attributed to factors that include, but are not limited to, technological infrastructure, digital literacy, financial constraints, user apprehension, and threats to existing cultures and values (Addy et al., Reference Addy, Asamoah-Atakorah, Mensah, Dodoo and Asamoah-Atakorah2024; Segun, Reference Segun2024). These contributing factors often result in governments in emerging economies facing slower integration of these technologies (Mikalef et al., Reference Mikalef, Lemmer, Schaefer, Ylinen, Fjørtoft, Torvatn and Niehaves2022; Addy et al., Reference Addy, Asamoah-Atakorah, Mensah, Dodoo and Asamoah-Atakorah2024). This contributes to the vast gap in AI adoption between developed and emerging economies, especially in the public sector.

Successfully integrating AI into government services does not depend solely on the availability of technological infrastructure but also on the ability to court user interest towards AI technologies (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Ward and Yoon2021). This makes it essential to understand users’ knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to use AI solutions. Knowledge and familiarity with AI significantly influence users’ willingness to accept these technologies, with knowledge serving as a vital enabler of technological adoption (Capestro et al., Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024). Attitudes towards AI are similarly pivotal, as individuals with positive perceptions are more likely to engage with AI-enabled services (Buck et al., Reference Buck, Doctor, Hennrich, Jöhnk and Eymann2022). Similarly, the technological readiness of users (Holmström, Reference Holmström2022), characterised by the positives such as optimism and innovativeness along with the negatives such as discomfort and insecurity, is a key driver of technological adoption and use, and the same holds for AI technologies. However, challenges remain, particularly regarding the mixed reactions of optimism and discomfort that AI technologies tend to evoke, as some users may be intrigued by its innovation, while others may hesitate due to insecurity or concerns over job displacement (Hagendorff and Wezel, Reference Hagendorff and Wezel2020; Yadrovskaia et al., Reference Yadrovskaia, Porksheyan, Petrova, Dudukalova and Bulygin2023).

It is important to understand these complex dynamics, especially for government-initiated AI services, which depend heavily on broad public support for successful implementation. The complex interaction of knowledge, attitudes, and technology readiness factors encapsulates the broader challenges of introducing AI into public services, where negative affects can hinder adoption despite optimism about the potential benefits (Montoya and Rivas, Reference Montoya and Rivas2019). Furthermore, drivers of AI adoption are multifaceted and context-dependent, with citizens’ perceptions shaped by their unique scenarios (Afful-Dadzie et al., Reference Afful-Dadzie, Lartey and Clottey2022; Al-Emran et al., Reference Al-Emran, AlQudah, Abbasi, Al-Sharafi and Iranmanesh2023). For instance, AL-Emran et al.’s (Reference Al-Emran, AlQudah, Abbasi, Al-Sharafi and Iranmanesh2023) study identified utility factors, such as performance expectancy and effort expectancy, as drivers of AI chatbot adoption for knowledge sharing, while social and conditional factors exerted little influence. This is hardly the case in emerging economies, where social and conditional factors, including family and friends’ recommendations (social) and the presence of enabling infrastructure (conditional), are the main drivers of AI adoption (Afful-Dadzie et al., Reference Afful-Dadzie, Lartey and Clottey2022). The adoption of AI in government services is complex and influenced by a variety of interacting factors. AI adoption should not just be framed from a simplistic view that assesses direct factor influence, ignoring the combined influence of multiple factors (Desouza et al., Reference Desouza, Dawson and Chenok2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Rau and Yuan2023). Therefore, it is crucial to examine how these factors, as combinations, influence AI adoption in government services in emerging economies, where AI has the potential to transform governance but faces substantial barriers to widespread adoption.

This article investigates the configurations of factors contributing to user adoption of AI in government services and unearths the essential contributors to this phenomenon. The study, therefore, seeks to answer the question: how can government-initiated AI services be successfully accepted by citizens? The study is timely, as governments across emerging economies are exploring the possibilities of implementing AI solutions across the services they offer citizens and grappling with the dynamics of citizens’ adoption of these services. Interrogating knowledge, attitude, and readiness factors, identified as antecedents of user adoption (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020), within configurational approach aids in unearthing the mechanisms underlying user adoption. The study combines FsQCA and PLS-SEM to compare configurational and correlational insights on AI adoption in government services. FsQCA is employed to identify the configuration of factors and core conditions for adopting government-led AI services. PLS-SEM further supports the FsQCA findings by testing the regression support for the factors. The study progresses by discussing the theoretical perspectives, followed by the methodology. The results, which combine results from FsQCA and PLS-SEM, are presented, followed by a discussion of the results and the study’s conclusion.

2. Conceptualising AI readiness

Different theoretical frameworks allow us to study and understand user adoption and acceptance of technology, including the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, Reference Davis1989), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Morris, Davis and Davis2003), and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, Reference Ajzen1991). These theoretical frameworks emphasise dimensions such as perceived usefulness, ease of use, social influence, and behavioural intentions as predictors of adoption and user acceptance, offering valuable insights into the dynamics that shape user decision-making. However, these theories’ focus on general technology acceptance factors (utilitarian and social constructs) may limit their applicability to complex, emerging technologies like AI, where psychological readiness plays a critical role. This study employs Parasuraman and Colby’s (Reference Parasuraman and Colby2015) Technology Readiness Index (TRI) to assess users’ positive and negative predispositions towards technology. To enhance the TRI’s explanatory power, this study extends the theoretical framework to include knowledge and attitudes, as these constructs address cognitive and affective barriers specific to AI.

TRI focuses on the psychological factors that lead to technology adoption (Parasuraman and Colby, Reference Parasuraman and Colby2015; Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020) but is limited in its capacity to capture cognitive (knowledge) and cognitive-affective (attitude) factors that are equally important in driving technology adoption (Koch et al., Reference Koch, Graczykowska, Szumiał, Rudnicka and Marszał-Wiśniewska2024). Criticisms of the theory (TRI) have been with respect to its ability to effectively explain technology adoption (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020), as it relies heavily on psychological factors. This limitation has led to integration with other acceptance models, such as TAM, to help improve on its explanatory power (Acheampong et al., Reference Acheampong, Zhiwen, Antwi, Otoo, Mensah and Sarpong2017; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Graczykowska, Szumiał, Rudnicka and Marszał-Wiśniewska2024). These theoretical extensions have, however, paid minimal attention to the full range of cognitive, affective, and psychological factors contributing to technology adoption, particularly with AI, and therefore necessitate the incorporation of cognitive (knowledge) and cognitive-affective (attitudes) factors into the theory to help improve the explainability of adoption of AI solutions. This extension is supported by evidence that knowledge shapes user confidence, and attitudes influence adoption readiness (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022; Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). In the subsequent sub-sections, a discussion of the selected constructs; knowledge, attitudes, optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity are advanced, demonstrating their explanatory power for AI-enabled government service readiness and the justification for their inclusion in the study.

2.1. Knowledge of AI

Users’ pre-knowledge of technology is a well-established antecedent of technology adoption within technology adoption models (Forman and Van Zeebroeck, Reference Forman and Van Zeebroeck2019; Capestro et al., Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024), as knowledge serves as a fundamental aspect that shapes individuals’ ability and willingness to interact with new and emerging technologies (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Knowledge in this study is conceptualised as the accumulation of information and skills through which individuals recognise the value and potential applications of technologies, fostering confidence in their use (Forman and Van Zeebroeck, Reference Forman and Van Zeebroeck2019). Knowledge facilitates cognitive processing, allowing users to evaluate the benefits and risks of adopting new technology (Capestro et al., Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024). The diffusion of innovation theory supports this view (Rogers et al., Reference Rogers, Singhal and Quinlan2014), positing that early adopters are those who typically possess greater knowledge and understanding of the technological landscape, leading them to appreciate the emerging technology’s potential and further adopt these technologies (Kinkel et al., Reference Kinkel, Baumgartner and Cherubini2022). This assertion extends to AI technologies, given that the complexity of such systems requires users to possess an appreciable level of knowledge to overcome barriers to adoption, such as perceived difficulty or a lack of trust in AI (Cubric, Reference Cubric2020). This makes knowledge a cognitive enabler and a behavioural catalyst, preparing users for AI adoption.

Given the tendency for misunderstanding and misconceptions to inhibit AI adoption, knowledge becomes even more critical, as informed users are likely to dispel such misconceptions and engage with AI services introduced by government agencies (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). AI technologies are often characterised by an abstract and opaque nature, which can dissuade apprehensive users who distrust technology. A higher level of knowledge among users leads to better comprehension and appreciation of these AI technologies. As AI pans out to become an essential part of public administration, knowledge of AI is likely to play a critical role in shaping the attitudes and readiness of users, as individuals having a stronger understanding of AI have a higher propensity to perceive its benefits and express willingness to adopt it (Ahn and Chen, Reference Ahn and Chen2022). AI adoption studies across sectors further suggest that the lack of knowledge dissemination is likely to curtail the realisation of AI solutions’ full potential, affirming the need for continuous education and information sharing to promote AI readiness amongst users (Capestro et al., Reference Capestro, Rizzo, Kliestik, Peluso and Pino2024). The study therefore hypothesises:

H1: Knowledge of AI systems has a positive influence on adoption of government-led AI services.

Knowledge interplays with attitudes and readiness as users navigate anxieties and uncertainties about the technology (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). AI’s perceived complexity and citizens’ unfamiliarity with its inner workings create a cognitive gap, where a lack of or minimal knowledge can lead to heightened discomfort and resistance (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Guo, Gao and Liang2021). Conversely, knowledgeable users of AI are more likely to show positive affects and affinity for adoption (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Therefore, knowledge is essential in mitigating these negative perceptions by demystifying AI technologies and aligning users’ expectations with the actual functionalities and limitations of AI systems (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). Knowledge-sharing mechanisms, therefore, serve as a significant panacea for AI adoption, enabling individuals to develop a deeper understanding of AI technologies through collective learning and reducing cognitive dissonance, thereby increasing trust in AI services (Kinkel et al., Reference Kinkel, Baumgartner and Cherubini2022; Yigitcanlar et al., Reference Yigitcanlar, Li, Inkinen and Paz2022).

2.2. Attitude towards AI

Attitude, as a psychological (cognitive-affective) construct, is an established determinant shaping individuals’ readiness to adopt new technologies. Attitudes towards a behaviour strongly influence an individual’s intention to engage in that behaviour, leading to the actual performance of the behaviour (Yadegari et al, Reference Yadegari, Mohammadi and Masoumi2024). Technology adoption models construct attitude as the evaluative responses that potential users of a technology form, given their beliefs on the benefits, risks, and overall utility of that technology. Positive attitudes towards a technology tend to lower adoption resistance, encouraging ready technology engagement among individuals (Cubric, Reference Cubric2020). Conversely, negative attitudes often serve as barriers to the adoption process despite the robustness of the technological infrastructure (Buck et al., Reference Buck, Doctor, Hennrich, Jöhnk and Eymann2022). Attitudes are therefore realised through the continuous interplay of cognitive and emotional evaluations, which affect an individual’s readiness to engage with and adopt new technologies. Such dynamics are more elaborate in industries experiencing rapid transformation, where users’ attitudes are central to effectively implementing digital solutions (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023).

The complexities of AI technology further amplify the need to consider the psychological factor of attitude. Positive attitudes towards AI technologies are formed when users believe they enhance their performance and that the technology use is associated with fewer cognitive or operational burdens (Kinkel et al., Reference Kinkel, Baumgartner and Cherubini2022). However, because AI is often perceived as complex and opaque, user attitudes towards it can be coloured by fear and scepticism, especially in contexts where knowledge is limited (Yigitcanlar et al., Reference Yigitcanlar, Li, Inkinen and Paz2022). Users may further develop negative attitudes when they believe there are ethical implications, a loss of control, and potential biases in AI decision-making (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Kaye and Oviedo-Trespalacios2023). Positive attitudes can be further entrenched amongst users through knowledge-building initiatives that demonstrate AI’s utility in automating tasks, improving decision-making, and enhancing operational efficiency (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Ward and Yoon2021). Positive experiences lead to attitudinal shifts, increasing readiness for AI adoption, especially when paired with institutional support that fosters trust in the technology (Cubric, Reference Cubric2020; Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). In public services, characterised by cautionary AI adoption, attitudes towards AI are shaped by a mix of individual experiences and peer behaviours (Gesk & Leyer, Reference Gesk and Leyer2022). As public perception of AI evolves, attitudes towards the technology remain an important factor in determining whether citizens are willing to engage with AI solutions in government services and incorporate them into their daily activities (Yigitcanlar et al., Reference Yigitcanlar, Li, Inkinen and Paz2022). This emphasises understanding the attitudinal dynamics of AI adoption to enhance readiness and ensure successful technology integration in public sector service delivery. The study therefore hypothesises:

H2: Positive attitude towards AI systems positively influences adoption of government-led AI services.

2.3. Readiness factors

Technological readiness plays a significant role in technological adoption. The TRI) developed by Parasuraman and Colby (Reference Parasuraman and Colby2015) offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how individuals and organisations approach technological adoption. TRI assesses users’ readiness to use new technologies along four key constructs: optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity (Parasuraman and Colby, Reference Parasuraman and Colby2015; Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020). The four constructs capture both positive and negative predispositions towards a technology. Optimism and innovativeness reflect the positive dimensions of technology readiness, emphasising a general belief in technology’s ability to enhance life and a tendency to leverage it as a tool in daily activities (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Conversely, the dimensions of discomfort and insecurity, which highlight the negative aspects, emphasise apprehension towards technology and feelings of being overwhelmed or anxious about it (Yahya et al., Reference Yahya, Rasyiddin, Mariko and Harsono2024).

Scholars argue that the dimensions of optimism and innovativeness facilitate the initial drive to engage with technology, while discomfort and insecurity create friction, potentially barring its full-scale adoption (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). In AI adoption, the dimensions of technology readiness offer a deeper insight into the psychological mechanisms that underpin AI adoption readiness amongst users (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). The pervasiveness of AI across organisational and societal frameworks underscores the importance of technology readiness, given individuals’ and organisations’ enthusiasm for AI’s potential and fears surrounding its ethical and operational complexities (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang and Zhao2022). This dualised reality creates a foundation for examining how readiness shapes the trajectory of AI adoption.

2.3.1. Optimism

Optimism reflects belief in the positive impacts of technology, particularly in enhancing efficiency, productivity, and overall quality of life (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020). It highlights the general sense that technological advances, including AI, improve various domains of human activity. In AI adoption, optimism plays a role as a catalyst for technological engagement, leading individuals to perceive AI as a tool that can augment human capabilities, streamline processes, and solve daily-life problems (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Optimism influences attitudes and, subsequently, behaviours towards using AI-based solutions, with citizens who are highly optimistic more willing to engage with new technologies such as AI and experience its potential (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). Optimism, therefore, plays a dual role as a psychological readiness factor and a predictor of actual technology use. Extant studies link optimistic attitudes with higher rates of AI adoption in sectors such as healthcare, manufacturing, and public administration (Najdawi, Reference Najdawi2020).

In government services, individuals expect technology to improve their service requests and overall livelihoods (Yahya et al., Reference Yahya, Rasyiddin, Mariko and Harsono2024). AI optimism may be particularly pronounced in contexts where the technology is perceived as groundbreaking and knowledge of AI leads to positive attitudes towards it (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Optimism about AI use may be influenced by individual characteristics, such as age, education, location (urban or rural), and prior technology experience, which can modulate how optimism influences readiness (Sing et al., Reference Sing, Teo, Huang, Chiu and Xing Wei2022). Similarly, optimism drives technology adoption by creating expectations that lead citizens to estimate AI’s transformative potential and anticipate better outcomes (Kullu and Raj, Reference Kullu and Raj2018). The study therefore theorises:

H3: Higher optimism towards AI systems has a positive influence on adoption of government-led AI services.

2.3.2. Innovativeness

Innovativeness reflects the tendency to be a technology pioneer, actively seeking out and adopting new tools ahead of others (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020). Innovators support the diffusion of technology by serving as early adopters, thereby enabling its widespread adoption (Horowitz and Kahn, Reference Horowitz and Kahn2021). High-innovation users are more likely to engage with AI technologies early in their development and deployment, serving as the critical mass that advances AI solutions from niche to mainstream adoption (Sing et al., Reference Sing, Teo, Huang, Chiu and Xing Wei2022). AI innovativeness, therefore, translates into a proactive stance of experimenting with AI applications (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). The propensity to innovate is particularly significant to public administration, where early AI adoption can significantly improve service delivery (Najdawi, Reference Najdawi2020).

Users characterised by high innovativeness are more likely to perceive AI government services as intuitive and manageable (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Innovativeness is not merely a personal trait but a reflection of values that prioritise experimentation and risk-taking. Furthermore, innovativeness is linked to a broader innovation culture, where the willingness to adopt AI is embedded within a nature that emphasises continuous improvement and technological agility (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). Innovativeness drives and pushes the boundaries for AI adoption, where citizens support a sustainable implementation and integration of the technology by driving its use (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang and Zhao2022). The study, therefore, posits:

H4: Higher innovativeness towards AI systems has a positive influence on adoption of government-led AI services

2.3.3. Discomfort

Discomfort is one of the negative-leaning dimensions of technology readiness, which measures the apprehension or unease users may feel when confronted with new technologies, particularly those considered more complex (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020). AI discomfort can manifest during adoption as fears of obsolescence, concerns about the perceived difficulty of learning new systems, and anxiety about how AI may disrupt established workflows (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Converse to optimism and innovativeness, discomfort amongst users presents a technological adoption barrier, slowing down or even halting the integration of AI in services. Users’ psychological discomfort is further grounded in a perceived lack of control over AI, where users feel overwhelmed by the advanced nature of AI, leading to resistance to change or avoidance behaviour (Yahya et al., Reference Yahya, Rasyiddin, Mariko and Harsono2024).

Discomfort may arise when users assess the effort expectancy or perceived difficulty associated with using AI services (Sing et al., Reference Sing, Teo, Huang, Chiu and Xing Wei2022). When technology appears opaque or complex, as most AI technologies may be characterised, users tend to exhibit greater discomfort, which, in turn, reduces the likelihood of adoption (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020). Discomfort with AI systems is heightened among non-expert users, who may find it challenging to understand and control AI technologies despite their tendency to produce high-accuracy, high-efficiency outputs (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang and Zhao2022). Discomfort can be further heightened in certain sectors of the economy, such as finance and healthcare, where misinterpretation of AI outputs could have significant consequences (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). This highlights discomfort as a psychological barrier that inhibits users’ readiness to adopt AI services. The study hypothesises:

H5: Higher discomfort towards AI systems has a negative influence on adoption of government-led AI services.

2.3.4. Insecurity

Insecurity as a readiness factor measures the fear or mistrust individuals or organisations may have regarding the reliability, safety, and ethical implications of new technologies (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020). Insecurity as a dimension is relevant in the context of AI in government services, with issues such as data privacy, algorithmic bias, and potential job displacement serving as foundations for fostering insecurity (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). Contrasting discomfort, which emphasises the perceived difficulty of interacting with AI, insecurity addresses broader concerns about the implications of AI’s integration into society. Users experiencing high insecurity levels tend to question the trustworthiness of AI systems, fearing that the AI use could result in unintended outcomes, including privacy violations, discriminatory outcomes, or loss of control over decision-making processes (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022).

AI insecurities may arise from perceived risks associated with its use, encompassing the functional and psychological risks associated with using new technologies (Yahya et al., Reference Yahya, Rasyiddin, Mariko and Harsono2024). Considering government services and AI usage, functional risks include concerns about system reliability, that is, whether AI systems will consistently perform as expected, while psychological risks consider fears about the broader societal implications of AI (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang and Zhao2022). These insecurities create significant barriers to AI adoption, as users become reluctant to fully trust AI systems despite their potential benefits. AI use in public administration, for instance, has been met with concerns among local government officials about the transparency and accountability of these technologies (Horowitz and Kahn, Reference Horowitz and Kahn2021).

Moreover, insecurity in AI intersects with broader societal narratives around the perceived dangers that AI presents. Media portrayals of AI as a disruptive force that could lead to widespread disruption or even the erosion of human autonomy contribute to increased insecurity among potential users (Sing et al., Reference Sing, Teo, Huang, Chiu and Xing Wei2022). This creates a feedback loop in which insecurity leads to the avoidance of AI technologies, further reinforcing negative AI perceptions. Unaddressed insecurities regarding AI result in significantly lower adoption of these technologies (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022). Managing insecurity is essential for fostering a readiness environment conducive to AI adoption, as it directly influences users’ willingness to engage with AI in government services. The study hypothesises:

H6: Higher insecurity towards AI systems has a negative influence on adoption of government-led AI services.

2.4. The interplay of knowledge, attitude, and readiness factors towards AI-enabled government services

User adoption and use of AI-enabled services are contingent on individual readiness factors interplaying with knowledge and attitudes. Knowledge, as a cognitive factor, shapes perceptions of the utility and risks associated with AI, while attitudes reflect emotional responses to its adoption (Flavián et al., Reference Flavián, Pérez-Rueda, Belanche and Casaló2022; Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). Users with a deeper understanding of AI’s capabilities are better prepared to adopt AI in government services, as knowledge helps address ambiguity and uncertainty, thereby mitigating discomfort and insecurity surrounding AI (Najdawi, Reference Najdawi2020). Knowledge, as a cognitive dimension, interacts with attitude and readiness factors, such as optimism, to create a more favourable disposition towards AI, as more knowledgeable users tend to exhibit positive emotional responses towards the technology (Kashive et al., Reference Kashive, Powale and Kashive2020; Sing et al., Reference Sing, Teo, Huang, Chiu and Xing Wei2022). This is affirmed by Selvam and Teoh (Reference Selvam and Teoh2024), who assert that technological (AI) knowledge is likely to minimise apprehension about technology and foster a perception of its usefulness. Conversely, a low level of knowledge, combined with positive attitudes and high optimism, may not be enough to overcome discomfort or insecurity, thereby barring users from adopting AI in government services.

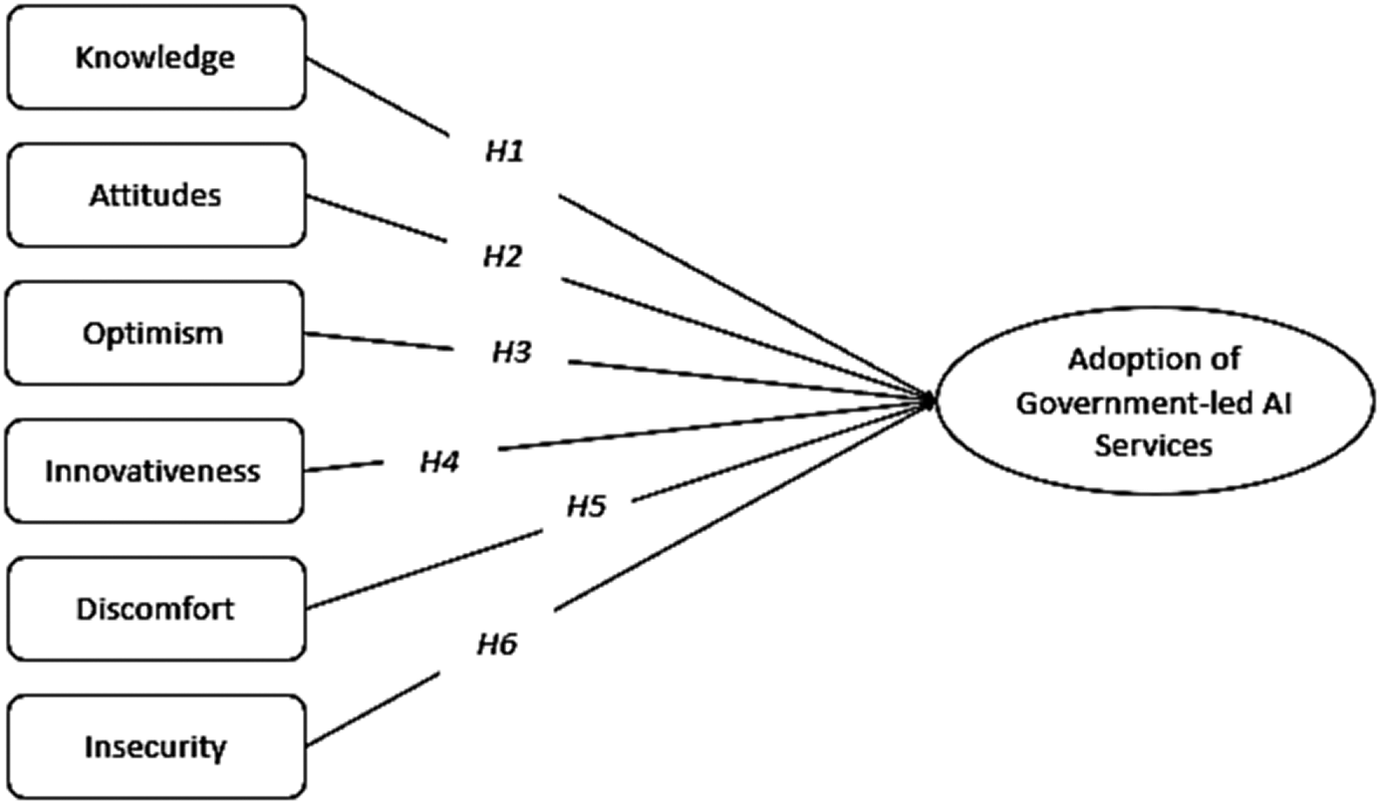

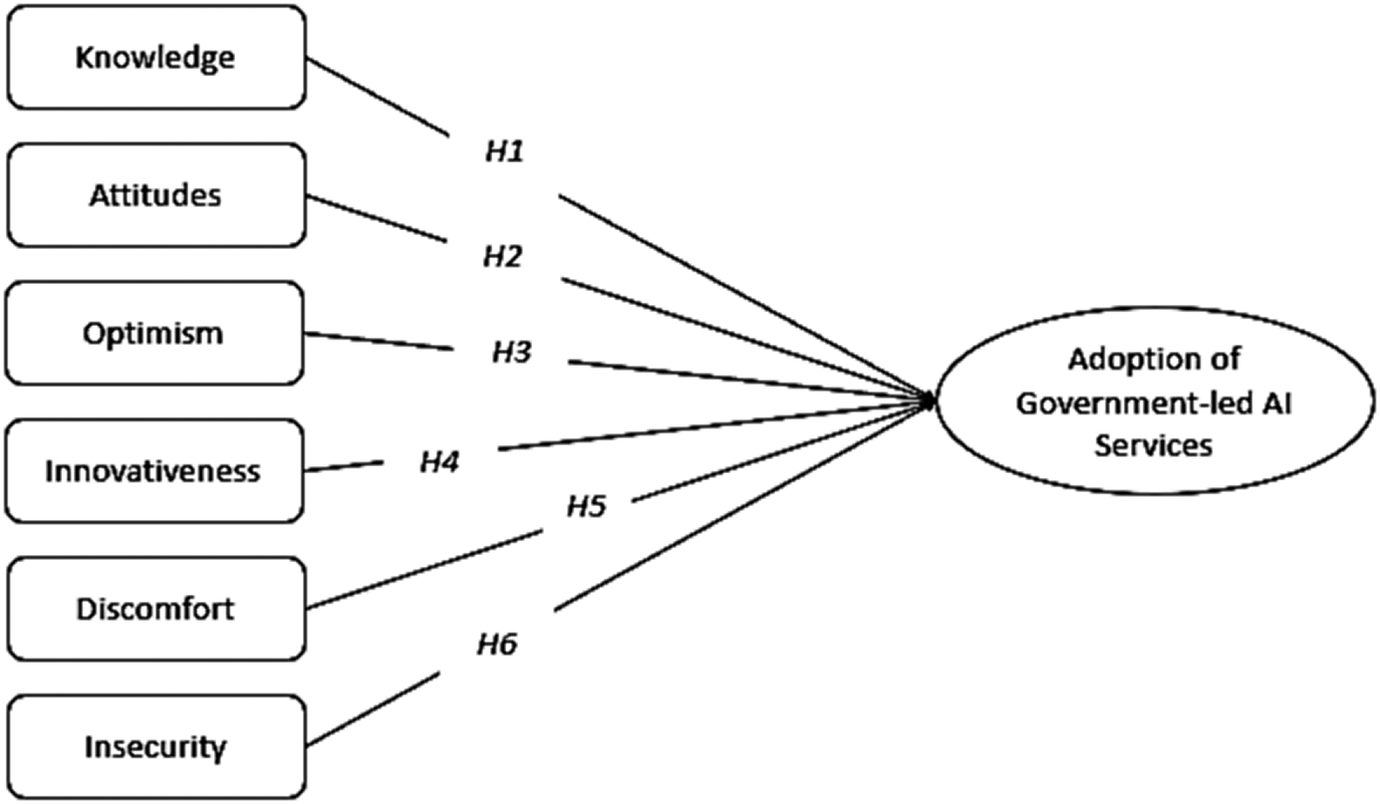

Additionally, AI adoption in government services influenced by readiness factors like optimism, innovation, discomfort, and insecurity is contingent upon the user’s pre-existing knowledge and attitudes towards AI, pointing to the configurational nature of adoption as against singular factor influence (Blut and Wang, Reference Blut and Wang2020; Yahya et al., Reference Yahya, Rasyiddin, Mariko and Harsono2024). Attitudes towards AI can interact with readiness factors to shape actual adoption behaviour: positive attitudes mitigate the negative effects of discomfort and insecurity, while negative attitudes can exacerbate these challenges. For instance, citizens with high optimism and low knowledge may adopt AI with unrealistic expectations, which may result in frustration and eventual technology resistance when it fails to meet their anticipated outcomes (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhang and Zhao2022). Similarly, understanding of AI formed from user knowledge can lead to positive affects, demonstrating how knowledge and attitudes synergistically facilitate the successful adoption of AI services (Horowitz and Kahn, Reference Horowitz and Kahn2021). For this reason, incorporating knowledge and attitudes into the current formulation of the TRI yields an extended Technology Readiness Framework that enables the investigation of AI readiness from a holistic viewpoint. The extended conceptualisation of readiness, which acknowledges the interaction among knowledge, attitudes, and readiness factors, offers a more contextually grounded model for understanding how adoption can be realised in AI-based government services. Figure 1 presents the conceptualisation of the extended Technology Readiness Framework, in which the constructs of knowledge, attitude, optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity combine under different conditions and configurations to realise the adoption of AI-based government services.

Figure 1. Conceptualisation of AI adoption in government services.

3. Methodology

3.1. Study sample and data collection

To understand the configuration of factors that drive citizens’ interest in using government-led AI services, the study pursued a quantitative survey research design. This was appropriate as it allowed the use of validated measurement scales to assess the variables for the Extended Technology Readiness Framework developed for the study. Technology Readiness Framework incorporates knowledge and attitudes into the TRI to determine AI use. Leveraging a non-probability snowball sampling technique, which offers a low-cost, target-driven approach to acquiring research respondents, online questionnaires were distributed to tertiary student-workers located in different regions of the country and snowballed to others within their circles. The study focused on an important respondent group of student workers. Extant studies have demonstrated that students and workers are the most inclined to use AI services (Pew Research Center, 2025). Students and workers leverage AI technologies as a productivity resource to help them effectively complete their workloads (Vargo et al., Reference Vargo, Zhu, Benwell and Yan2021). The focus on student workers who sit at the intersection of the two groups (students and workers) helps unearth the positive and negative dispositions towards AI among the likely users of government-led AI services when implemented. They represent the group most highly exposed to AI services and will exhibit the requisite levels of knowledge, attitudes, and other readiness factors to determine citizens’ overall readiness to adopt government-led AI services. The suggested generalisability of the findings from student-workers to other citizens of emerging economies is grounded in the position that lead users can offer an indicative understanding of how technology diffuses within the general population (Von Hippel, Reference Von Hippel1986; Von Hippel et al., Reference Von Hippel, Bartholmoes, Nohlin and Jeppesen2024). There is also support in the literature (Kaya et al., Reference Kaya, Aydin, Schepman, Rodway, Yetişensoy and Demir Kaya2024; Liu and Wang, Reference Liu and Wang2024) that positions students and workers (with student-workers being an intersection of these two groups) as lead users of AI services, further validating the selection of student-workers as a representative group for the study.

Data for this study were collected via an online survey administered via Google Forms to tertiary student-workers in Ghana. The survey was administered over 3 months, from November 2023 to January 2024. To ensure data integrity, measures were implemented to limit each individual to a single response, preventing duplicate responses and maintaining the accuracy of the sample. The online nature of the survey enabled efficient data collection and reached students across different institutions in Ghana. The survey was designed to gather insights into respondents’ demographics, readiness, knowledge, and attitudes towards AI adoption, utilising constructs from established scales.

At the end of the data collection period, the survey received responses from 385 tertiary student-workers across the country. A 64% full-response rate was achieved on the distributed questionnaire, with 245 of the total respondents completing their questionnaires. Participants aged 25 or younger accounted for 1.6% of the respondents, and those aged 25–34 accounted for 47.8% of the total complete responses. Participants aged 35–44 accounted for 35.9%, those aged 45–54 for 13.1%, and those aged 55–64 for 1.6%. Regarding participants’ sex, females accounted for 59.2% of respondents, while males accounted for 40.8%. In terms of educational level, 53.1% of the respondents held a bachelor’s degree, followed by 45.3% with a master’s degree, and a small 1.6% with a doctorate degree. The sectoral affiliation of respondents showed a slight leaning towards the private sector, accounting for 53.1% of respondents. Public sector respondents accounted for 40.8%, while the non-profit sector contributed 6.1% of the responses. The study sample demonstrated a high level of diversity in age, gender, educational level, and sectoral representation. The diverse respondents provide a well-rounded sample for investigating the readiness to adopt AI-enabled government services.

3.2. Constructs of study

All constructs for the study were drawn from existing, validated scales in the extant literature. The study leveraged Parasuraman and Colby’s (Reference Parasuraman and Colby2015) and Parasuraman’s (Reference Parasuraman2000) formulation of the Technology Readiness Index, which validates measures of optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity. The constructs are important measures for evaluating participants’ predisposition to embrace new technologies. The constructs were modified to fit the current study of AI in government services without losing their formulation from the established literature. The knowledge construct was sourced and modified from the study by Houshyari et al. (Reference Houshyari, Bahadorani, Tootoonchi, Gardiner, Peña and Adibi2012), which provides a set of scales to measure user knowledge in a topical area. This allowed for the assessment of respondents’ knowledge of AI. Attitudes and adoption behaviour towards AI were assessed using established scales modified from the study by O’Shaughnessy et al. (Reference O’Shaughnessy, Schiff, Varshney, Rozell and Davenport2023) and Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Chun and Song2009). All questionnaire items were Likert-type measured on a five-point scale spanning strongly disagree to strongly agree, with the midpoint set to neutral.

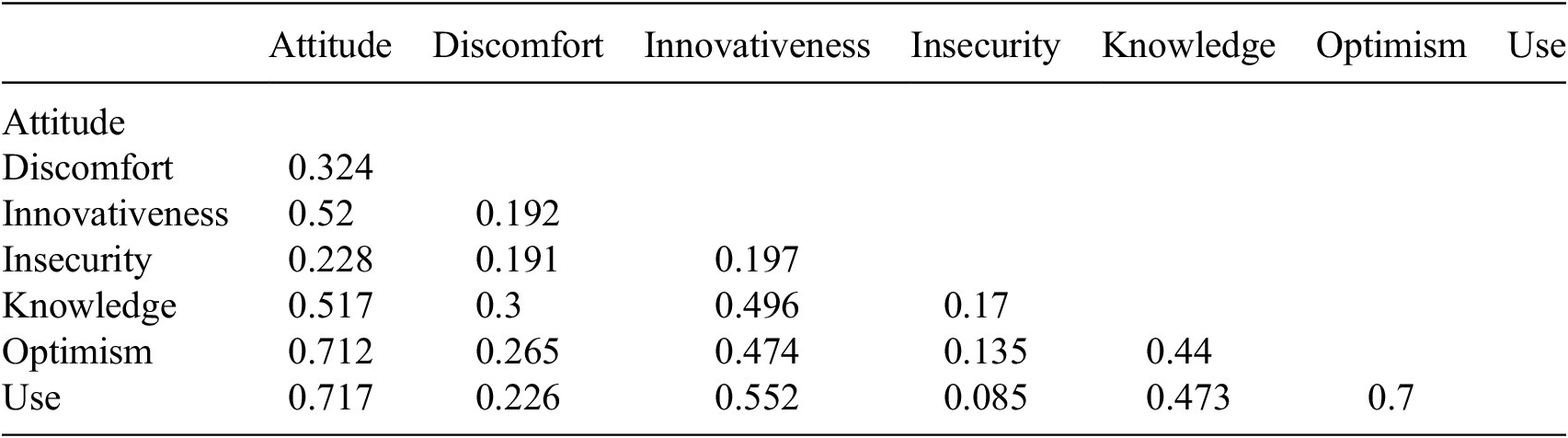

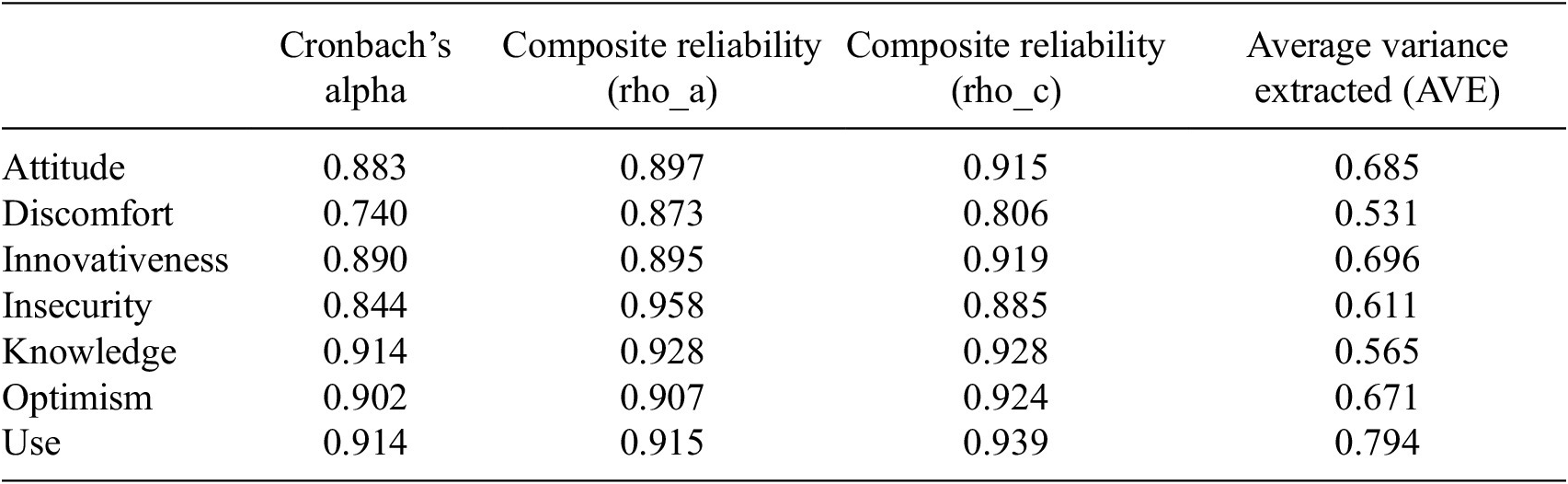

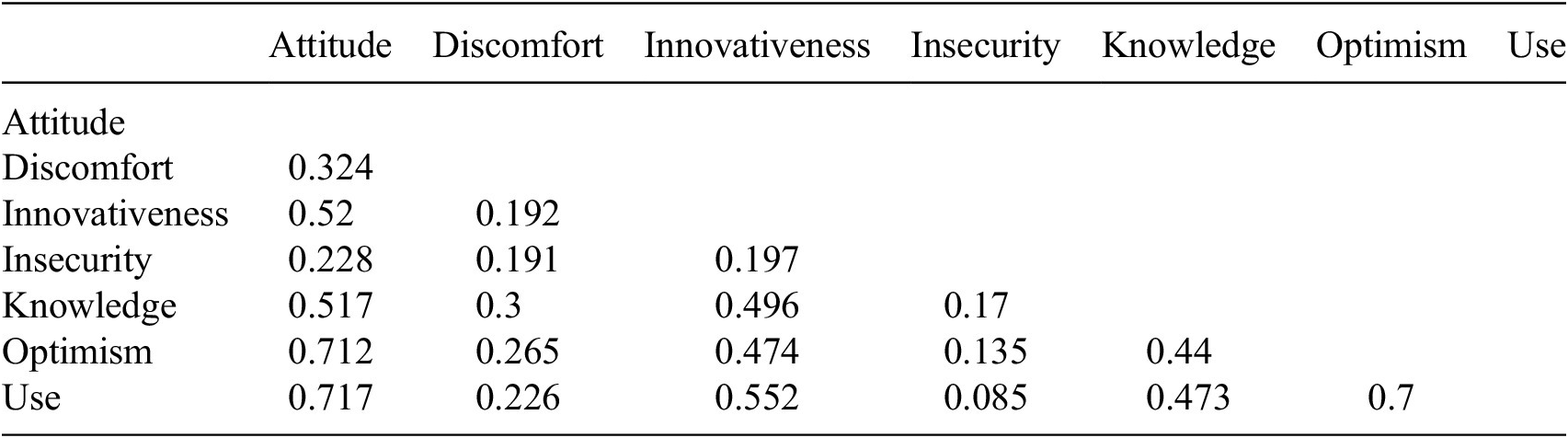

The test for reliability and validity of the modified scales was conducted, and the results demonstrated reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The Cronbach alpha and Composite reliability scores for all constructs, as shown in Table 1, exceeded the 0.7 threshold (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle, Sarstedt, Danks and Ray2021), affirming the reliability of the measurement items used in the study. Similarly, the convergent validity of the constructs, as measured by the average variance extracted (AVE) in Table 1, indicates that all constructs exceeded the 0.5 cut-off, thereby achieving convergent validity. The heterotrait-monotrait ratio was assessed to determine the discriminant validity of the constructs. As shown in Table 2, there is no instance in which the correlations exceed the threshold of 0.90 (Hair et al., Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle, Sarstedt, Danks and Ray2021), affirming the discriminant validity of the measurement items used in the study.

Table 1. Constructs reliability assessment results

Table 2. Heterotrait-monotrait ratio results for constructs

3.3. FsQCA analysis

The study employed the fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (FsQCA) procedure outlined by Afful-Dadzie et al. (Reference Afful-Dadzie, Lartey and Clottey2022). The first step was to average the scores of the measurement items for each construct for each individual, thereby obtaining the individual’s score for every construct. The averages represent the summary values for each construct under study. The data analysis then proceeded using FsQCA software. An important step in FsQCA analysis is data calibration, which involves determining thresholds informed by the data. The thresholds were identified as the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles of the summarised construct values. The thresholds helped define the set membership scores for each construct and each case (a case represents a row of data), where the 5th percentile served as the threshold for full non-membership, the 50th percentile served as the crossover point, and the 95th percentile served as the threshold for full membership (Ragin, Reference Ragin2007). This aligned the data with the requirements of the FsQCA approach by fuzzifying the data to values between 0 and 1, which is crucial for accurately identifying patterns of relationships among constructs (Afful-Dadzie et al., Reference Afful-Dadzie, Lartey and Clottey2022).

A truth table analysis was performed following the calibration, with the frequency cut-off set to 3. The frequency cut-off threshold of 3 was selected to ensure that the configurations identified adequately represented the data, following the guidance from Pappas et al. (Reference Pappas, Kourouthanassis, Giannakos and Chrissikopoulos2016), who applied this criterion in their study on online shopping behaviour. Additionally, to maintain the reliability of the resulting solutions, a consistency cut-off of 0.8 was used, ensuring that the identified combination patterns exhibited strong empirical consistency. Logical minimisation was implemented by specifying the “absence of insecurity” and the “absence of discomfort.” The obtained results were then interpreted.

3.4. PLS-SEM analysis

The study employed partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) to assess the statistical significance of the relationships among the constructs and AI adoption in government services. The study, having evaluated the measurement model, followed the procedures outlined by Hair et al. (Reference Hair, Hult, Ringle, Sarstedt, Danks and Ray2021) and Afful-Dadzie et al. (Reference Afful-Dadzie, Clottey, Kolog and Lartey2023) and established the constructs’ reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The structural model’s assessment, including path coefficients, R2 values, and the significance of relationships between variables, is presented in the results section and compared with the findings from the FsQCA analysis to provide a comprehensive view of the relationships among readiness factors and AI-enabled service adoption. This analysis was performed as a second layer to further validate the findings from the FsQCA analysis. It therefore served as a means of methodological triangulation to enhance the reliability and validity of the study’s findings (Jack and Raturi, Reference Jack and Raturi2006). Despite differences between the two approaches (configurational versus correlational), cross-validation can strengthen the study’s findings.

4. Results

4.1. FsQCA findings

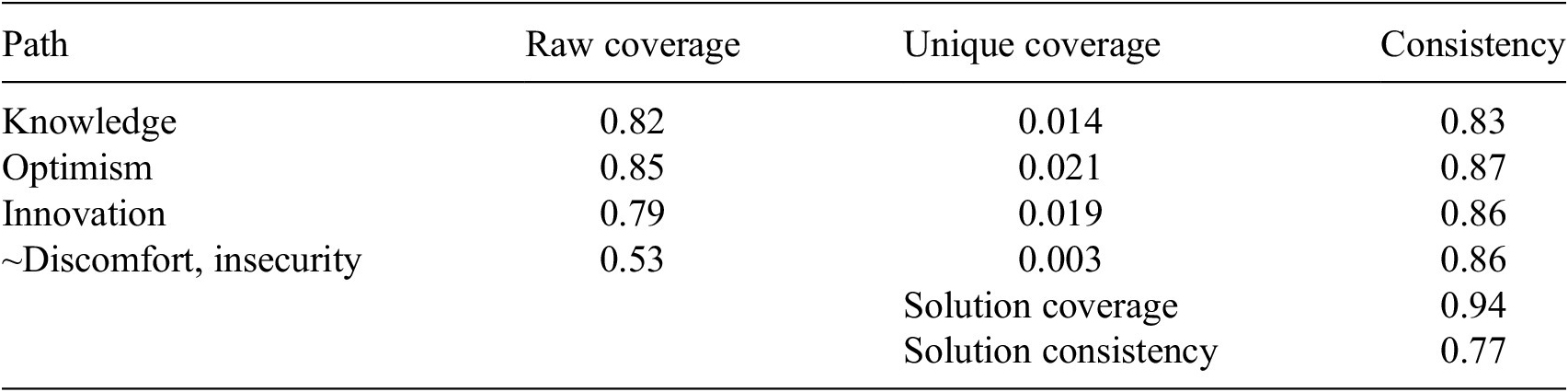

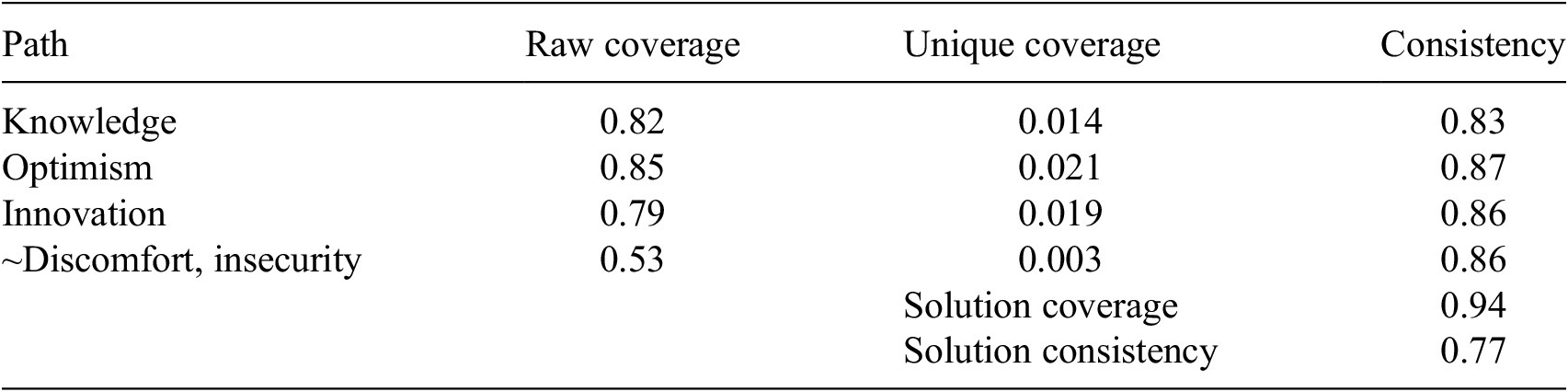

Table 3 presents the parsimonious solution obtained from the FsQCA analysis. The parsimonious solution presents the core conditions identified from the data that contribute to the outcome (Ragin, Reference Ragin2009), in this case, AI adoption in government services. Four core conditions were identified: knowledge, optimism, innovativeness, and absence of discomfort combined with insecurity, which, when present, likely leads to the adoption of AI in government services.

Table 3. Parsimonious solution to AI services adoption in government services

For each core condition, the raw coverage, unique coverage and consistency were presented. Raw coverage quantifies the proportion of cases explained by a specific causal configuration (Ragin, 2008). It reflects the extent to which a particular solution contributes to the outcome within the dataset. A high raw coverage suggests that the solution is relevant to the majority of cases, though it does not make it exclusive to those cases. The results in Table 3 show high raw coverage for optimism (0.85), knowledge (0.82), and innovativeness (0.79), while the absence of discomfort combined with insecurity shows a fair raw coverage (0.53). In the case of unique coverage, it measures the proportion of cases explained solely by a particular solution pathway, excluding cases in which other solutions overlap (Ragin, 2008). Unique coverage helps identify solutions that provide distinct explanatory value. Unique coverage helps determine the individual importance of a specific solution within the overall solution set. The results in Table 3 show the least unique coverage within the core solution, absence of discomfort paired with insecurity of 0.003 and the highest within the core solution, optimism of 0.021. Consistency measures the degree to which cases with a specific causal configuration exhibit the outcome (Ragin, 2008). Higher scores for consistency (typically above 0.8) suggest a solution that is a strong and consistent predictor of the outcome. Conversely, lower consistency scores indicate variability in how the solutions relate to the outcome. All the core conditions demonstrate a high consistency of above 0.8, suggesting that for each of the core conditions identified, the outcome occurs greater than 80% of the time when they occur.

Solution coverage measures the proportion of cases that can be explained by the entire set of identified solutions (Ragin, 2008). Solution coverage assesses the overall solution’s explanatory power; higher coverage indicates that the solutions collectively account for a larger share of cases with the outcome. With a solution coverage of 0.94, the solution set presented in Table 3, as core conditions, therefore accounts for 94% of cases in which AI adoption in government services occurs. The solution consistency measures the degree to which the solutions, as a whole, reliably predict the outcome (Ragin, 2008). High solution consistency (above 0.75) indicates that, collectively, the solutions consistently align with the presence of the outcome. The solution consistency, which measured 0.77, satisfies this criterion. The findings suggest that, for AI adoption in government services, knowledge of AI, optimism about AI, and AI innovativeness are essential. Interestingly, users with insecurities will adopt AI in government services when there is no discomfort. These core conditions point to the vital elements that implementers of such AI solutions need to focus on in order to maximise user adoption of these government services.

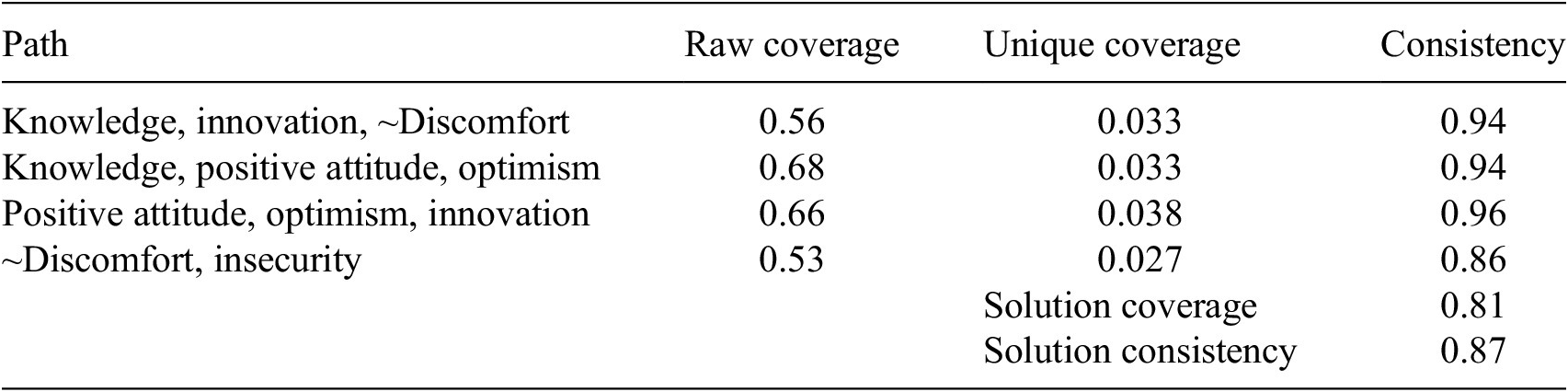

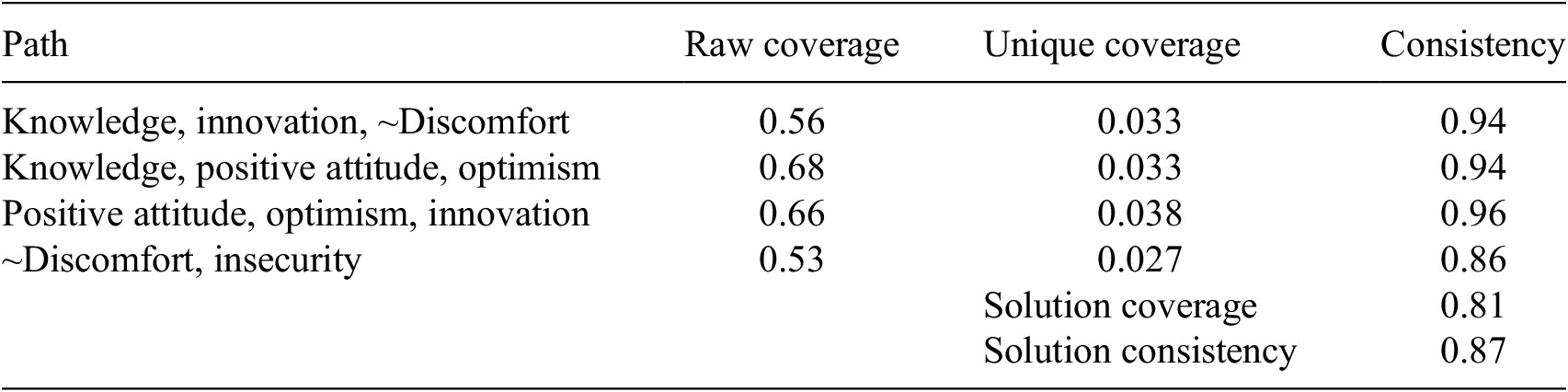

Table 4 shows the intermediate solution derived from the FsQCA analysis. The table shows four distinct pathways contributing to AI adoption in government services. The first pathway, involving knowledge, innovativeness, and the absence of discomfort, has a raw coverage of 0.56, a unique coverage of 0.033, and a consistency score of 0.94. The second pathway, consisting of knowledge, positive attitude, and optimism, has the highest raw coverage at 0.68, a unique coverage of 0.033, and a consistency of 0.94. The third pathway, composed of positive attitude, optimism, and innovation, demonstrates a raw coverage of 0.66, the highest unique coverage of 0.038, and the highest consistency of 0.96. The fourth pathway, characterised by the absence of discomfort paired with insecurity, shows a raw coverage of 0.53, the lowest unique coverage at 0.027, and a consistency of 0.86. The overall solution coverage of 0.81 indicates that these four pathways collectively explain 81% of AI adoption instances, demonstrating substantial explanatory power. The solution consistency of 0.87 suggests that the configurations reliably lead to AI adoption across cases, confirming the robustness of these identified pathways in predicting adoption. The significance of these pathways is elaborated on in the discussion of the findings.

Table 4. Intermediate solution to AI adoption in government services

4.2. Findings from PLS-SEM

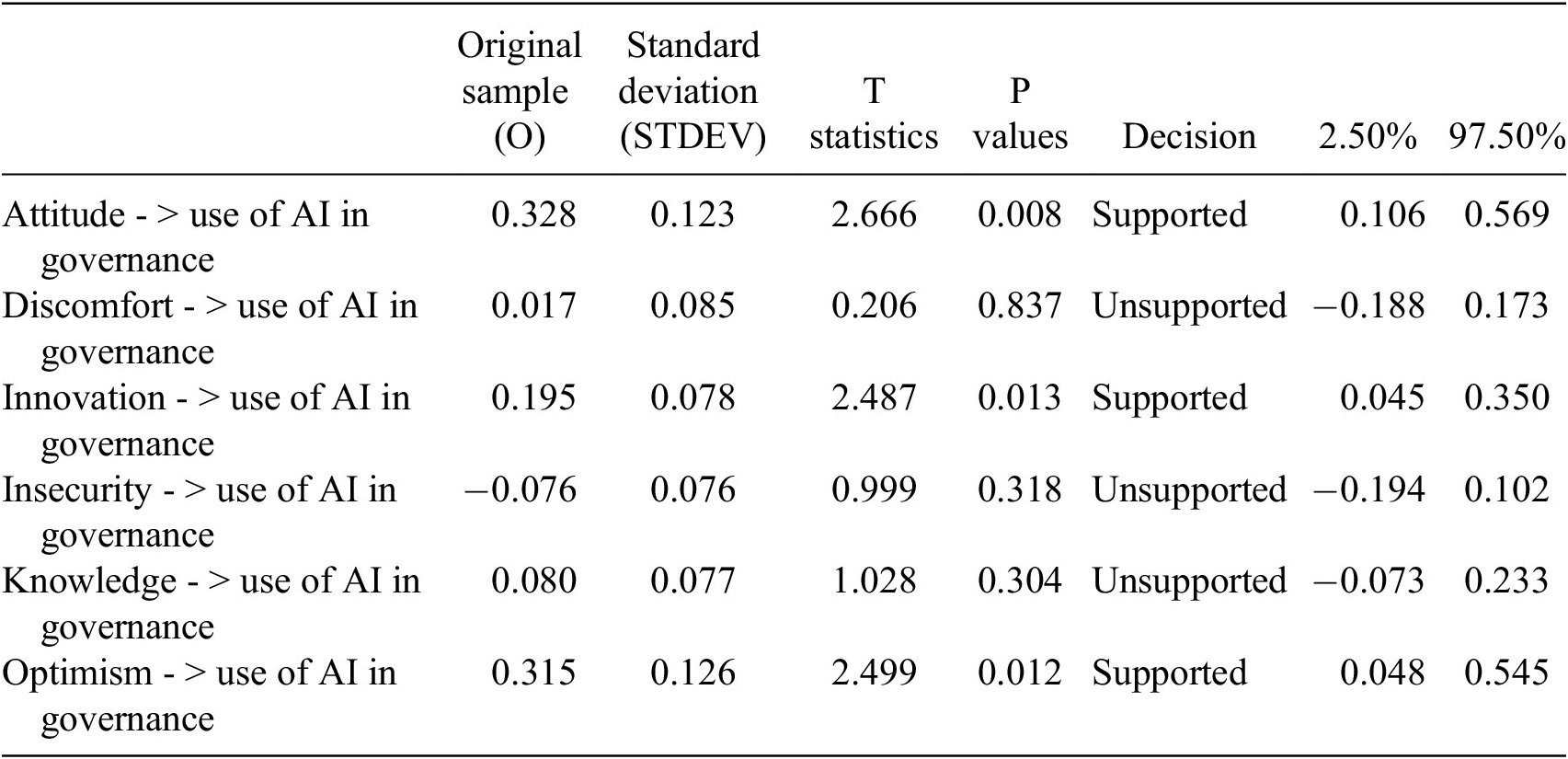

Table 5 presents the results of the structural model assessment using PLS-SEM. The result provides insights into the relationships among key variables influencing AI adoption in government services, as seen through a regression lens. Attitude demonstrated a high coefficient of 0.328 (p-value = 0.008), indicating a robust positive effect on AI adoption in government services. Similarly, optimism and innovation had significant positive coefficients of 0.315 (p = 0.012) and 0.195 (p = 0.013), respectively, supporting their contributions to AI adoption. These findings suggest that a positive attitude, optimism, and a tendency towards innovation contribute to motivating individuals to engage with AI-enabled government services. On the other hand, knowledge, discomfort, and insecurity did not exhibit significant effects on adoption, with coefficients of 0.080 (p = 0.304), 0.017 (p = 0.837), and − 0.076 (p = 0.318), respectively, leading to the rejection of these hypotheses. The lack of support for knowledge suggests that understanding AI alone does not directly drive adoption. Meanwhile, the non-significant effects of discomfort and insecurity indicate that these factors do not support users’ adoption of AI.

Table 5. Findings from PLS-SEM

5. Discussion and implications

The FsQCA findings analysis unearth four distinct pathways to AI adoption in government services, which can be broadly categorised under AI enthusiasts and AI sceptics. The AI enthusiasts’ pathways highlight positive dispositions towards AI in government services, including knowledge, positive attitude, optimism, and innovation. One such configuration, “knowledge, positive attitude, and optimism,” suggests that those with a strong knowledge of AI, combined with an optimistic outlook and a positive attitude towards AI, are predisposed to adopt AI-enabled solutions in government services. Similarly, the pathway “positive attitude, optimism, and innovation” reflects the predisposition of citizens who actively seek and embrace AI solutions, suggesting that a mindset of innovation, coupled with optimism, promotes AI adoption. The pathway “knowledge, innovation, and ~ discomfort” highlights users who adopt AI in government services, possessing adequate knowledge, being innovative, and avoiding discomfort. These pathways point to the role of psychological and experiential factors in shaping the profiles of individuals likely to engage proactively with AI solutions, characterising the AI enthusiast group.

Conversely, the pathway “~discomfort, insecurity” shows a different profile, representative of AI sceptics who, despite adopting AI, remain plagued by reservations. This pathway suggests that even citizens with insecurities about AI will still adopt AI solutions when certain enabling factors exist to minimise discomfort. These insecurities can be influenced by inherent cultural factors (O’Shaughnessy et al., Reference O’Shaughnessy, Schiff, Varshney, Rozell and Davenport2023) and can be overcome through carefully crafted strategies such as education and training (Tung & Dong, Reference Tung and Dong2023). In this pathway, an absence of discomfort in using these AI-enabled government services appears sufficient to drive adoption despite an underlying scepticism. This highlights the relevance of eliminating roadblocks and challenges that can help overcome insecurities and promote the adoption of these services. This finding aligns with the extant literature suggesting that technology sceptics can still adopt new systems in the wake of reduced apprehension factors or be compensated for by other influential factors, such as perceived usefulness (Venkatesh et al., Reference Venkatesh, Thong and Xu2012). Evidence from O’Shaughnessy et al. (Reference O’Shaughnessy, Schiff, Varshney, Rozell and Davenport2023) further suggests that risk aversion and techno-scepticism influence behaviours regarding the use of AI. This indicates that addressing discomfort with effective strategies can encourage sceptics to adopt, revealing an important insight into motivating reluctant users.

The core conditions identified; knowledge, optimism, innovation, and ~ discomfort paired with insecurity are critical for shaping citizens’ susceptibility to AI adoption. Knowledge, as a core condition, outlines the significance of AI familiarity and understanding in reducing ambiguity surrounding these services. Prior research emphasises that knowledgeable users feel confident in navigating AI interfaces and in understanding possible outcomes (Ahn and Chen, Reference Ahn and Chen2022), findings aligned with this study. Optimism, another core condition, suggests that a positive outlook on AI solutions enhances readiness for adoption, likely because optimistic individuals expect favourable outcomes from AI in public services. Innovation, as a core factor, captures the willingness to experiment with AI solutions, a trait crucial for early adoption. Finally, the solution of low discomfort paired with low insecurity reveals that minimising apprehension can make users more receptive to AI. This finding resonates with studies on technology readiness, which indicate that discomfort and insecurity act as psychological barriers that reduce technology acceptance (Parasuraman and Colby, Reference Parasuraman and Colby2015).

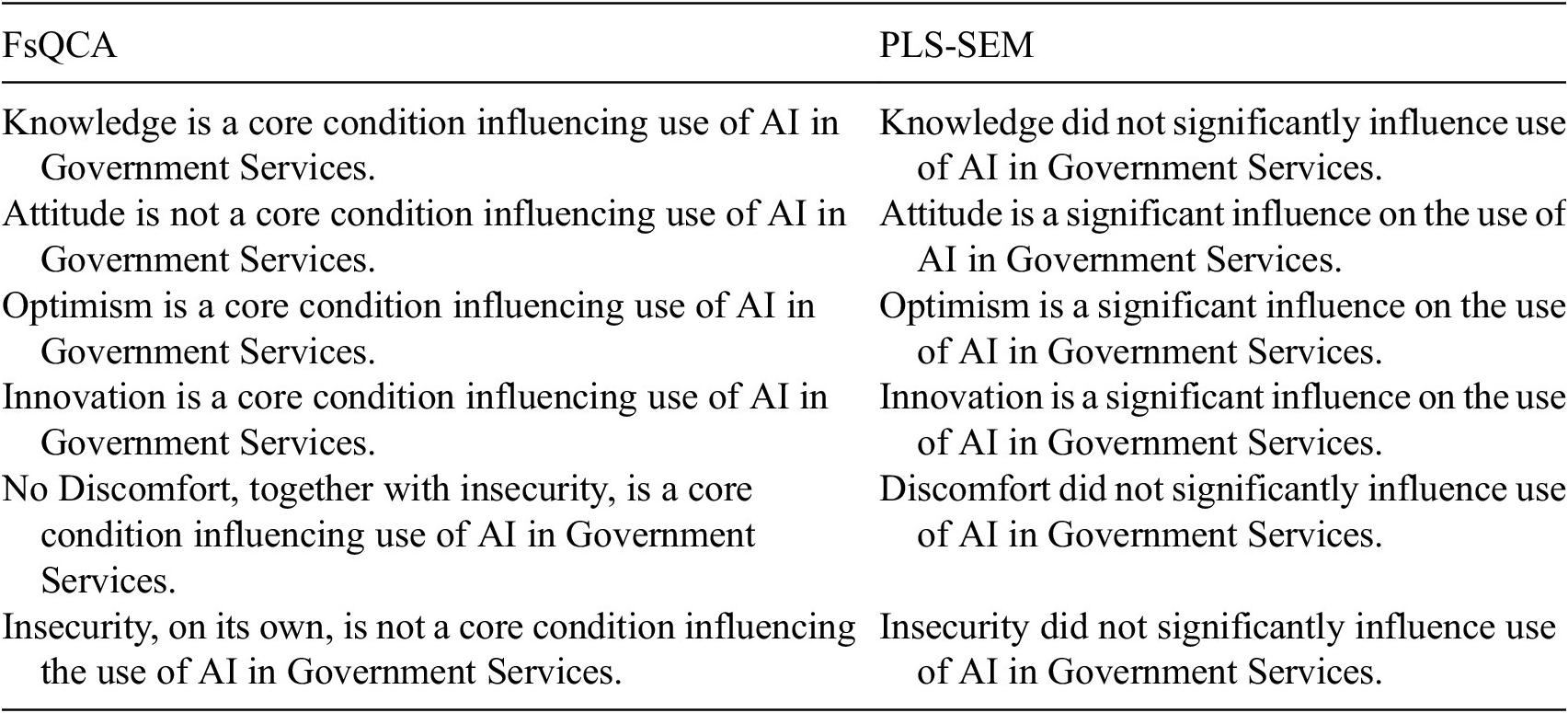

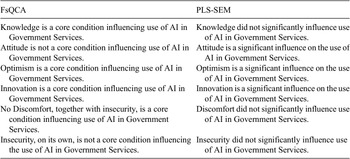

The PLS-SEM analysis results offer both support and divergence from the FsQCA findings, as summarised in Table 6. Notably, both analyses indicate that optimism and innovation significantly influence AI adoption, reflecting their consistent role in driving user engagement with AI services. Optimism and innovation had significant coefficients in the PLS-SEM model, reinforcing their central importance as core conditions in the FsQCA results. This alignment suggests that individuals with a positive outlook on AI and a tendency to innovate are highly likely to embrace AI-driven public services. However, the findings diverge with respect to knowledge and attitude. In FsQCA, knowledge is identified as a core condition, emphasising its relevance in driving adoption across various configurations. In contrast, the PLS-SEM results show that knowledge does not have a statistically significant effect on AI adoption, indicating that while knowledge can be part of successful adoption configurations, it may not independently predict adoption. Similarly, attitude was not considered a core condition in FsQCA, yet it is significant in the PLS-SEM results, suggesting that a positive attitude towards AI may still play a role in shaping adoption behaviour, even if it does not appear as essential in the configurational pathways identified in FsQCA. This discrepancy between the models highlights the complexity of technology adoption, in which certain factors may operate more effectively in conjunction with others rather than in isolation (Ragin, 2008).

Table 6. Comparison of FsQCA and PLS-SEM findings

The findings carry several practical and theoretical implications. For practice, these results underscore the need for public sector strategies that promote optimism, innovation, and knowledge while addressing discomfort and insecurity. Policymakers and technology implementers should focus on informational campaigns that clarify AI’s benefits, safety, and ease of use to increase citizens’ confidence and optimism. Training programs can boost users’ technological literacy and innovative thinking, equipping them with the skills to engage meaningfully with AI systems. Additionally, public institutions should address concerns related to discomfort and insecurity by emphasising transparency in data handling and ethical AI usage, as these factors have shown to significantly deter users when left unaddressed (Suseno et al., Reference Suseno, Chang, Hudik and Fang2023). Together, these initiatives could foster an environment where both enthusiasts and sceptics feel comfortable adopting AI, thus promoting broader acceptance in government services.

Theoretically, these findings contribute to understanding AI adoption in the public sector by revealing the configurational nature of core conditions like knowledge, optimism, and innovation. The FsQCA approach elucidates how these factors interact in complex combinations, offering a more nuanced view of adoption compared to linear models. Moreover, the observation that even technology sceptics, when discomfort is mitigated, can adopt AI solutions contributes new insights into the technology adoption literature, suggesting that other enabling factors can moderate psychological resistance. This study also contributes to the debate on the role of knowledge in technology adoption, where the differences between FsQCA and SEM suggest that knowledge may not operate as a direct predictor but rather as part of a multifaceted adoption configuration. This configurational perspective extends theoretical models of technology adoption, supporting a more holistic understanding of user engagement with AI in public services.

6. Conclusion

This study examined the factors influencing emerging economy citizens’ adoption of AI in government services, leveraging FsQCA and complemented by PLS-SEM methodologies to capture the complex interplay of psychological, experiential, and perceptual factors that drive or inhibit AI engagement. The results reveal two groupings: AI sceptics and AI enthusiasts who adopt AI in government services. There is a complex interplay of factors that drive user engagement with these services, which implementers of such solutions must consider to increase the likelihood of adoption.

This study opens avenues for further investigation. First, future research should explore the role of contextual factors in shaping AI adoption in different governance environments. While this study focused on psychological factors, further research could investigate how variations in cultural, regulatory, or infrastructural contexts influence citizens’ perceptions and readiness for AI. Comparative studies across countries or regions could provide insights into how external environmental factors interact with psychological and experiential conditions to either facilitate or hinder AI adoption in public services.

Second, further studies could delve deeper into the dynamics of AI adoption among technology sceptics, particularly examining the long-term sustainability of their engagement with AI services. This study suggests that sceptics may adopt AI under certain favourable conditions, but whether such adoption is sustainable over time or prone to reversal remains unclear. Longitudinal research could investigate whether initial adoption among sceptics persists as they gain experience with AI or whether sustained engagement requires additional interventions, such as continuous education and reassurance regarding AI’s ethical and security aspects. These future research directions would provide a richer understanding of how to create enduring engagement with AI in the public sector, building on the insights from this study.Top of Form.

Data availability statement

The Replication data (Lartey et al., Reference Lartey, Afful-Dadzie and Afful-Dadzie2025) can be found within the Harvard Dataverse from the URL: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GRVNCA.

Author contribution

Conceptualization-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D., A.A-D.; Data Curation-Lead: S.O.L., E.A-D.; Data Curation-Supporting: A.A-D.; Formal Analysis-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D.; Investigation-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D.; Methodology-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D.; Project Administration-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D.; Resources-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D.; Supervision-Lead: E.A-D.; Supervision-Supporting: S.O.L., A.A-D.; Validation-Lead: E.A-D.; Validation-Supporting: S.O.L.; Visualization-Equal: S.O.L.; Writing – Original Draft-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D., A.A-D.; Writing – Review & Editing-Equal: S.O.L., E.A-D., A.A-D.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.