Outcomes can be defined as the results that matter most to patients and an outcome measure is a method of quantifying these results. Reference Melchert and Melchert1 Measurement can be achieved through various means, including by quantifying hard outcomes, such as mortality or hospital admission rates, and questionnaires completed by a range of informants, such as patients, carers and clinicians. Reference Ryland, Carlile and Kingdon2 The Royal College of Psychiatrists endorses the routine use of outcome measures to support clinical care in mental health services. 3 It has produced several pieces of guidance for its members on the use of outcome measures, most notably the College Report entitled Outcome Measures in Psychiatry (CR240), published in June 2024. This report brought together the views of each faculty of the College, governed by the overarching principles that outcome measures should support patient care and be clinically meaningful and valid.

The use of outcome measures has been a topic of interest for psychiatrists since at least the 1990s, Reference Coates4–Reference Oyebode, Cumella, Garden and Nicholls6 when the UK Department of Health commissioned the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Research Unit (CRU) to develop the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS). Reference Wing, Beevor, Curtis, Park, Hadden and Burns7,Reference Wing, Curtis and Beevor8 This clinician-reported outcome measure (CROM), originally designed for working-age adults, has been subsequently adapted for a range of other settings and patient groups. Reference Harris, Sparti, Scheurer, Coombs, Pirkis and Ruud9 HoNOS was used as the basis for clustering, which was intended to underpin a move towards payment by results. Clustering was highly controversial, attracting criticism for being unnecessarily burdensome on clinicians’ time and unreflective of clinical realities. Reference Yeomans10 Clustering has since been abandoned, and work is underway to identify new payment systems. 11

In recent years there has been a particular focus on the importance of promoting patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), which are completed by patients themselves. Reference Roe, Slade and Jones12 For example, PROMs are integral to the National Health Service’s (NHS) Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme (now referred to as NHS Talking Therapies), which mandates practitioners to offer their patients the opportunity to complete PROMs to measure progress during treatment. Reference Wakefield, Kellett, Simmonds-Buckley, Stockton, Bradbury and Delgadillo13 Although PROMs are yet to be mandatory beyond IAPT services there is a proliferation of guidance. Different types of service currently demonstrate varying levels of maturity in the use of outcome measures. Liaison psychiatry services have published a framework for routine outcome measurement (FORM-LP), Reference Trigwell and Kustow14 which recommends specific measures for process, PROMs, CROMs, and patient and referrer satisfaction. The National Clinical Audit of Psychosis has been collecting data on HoNOS, DIALOG and the Process of Recovery Questionnaire (QPR) since 2018, but the reports do not analyse outcome scores to measure change. 15 The National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH) was commissioned by NHS England to produce an implementation guide in response to the commitment to increasing the use of PROMs in the NHS Long Term Plan (2019). Reference Alderwick and Dixon16 The NCCMH recommended the use of three measures – DIALOG, goal-based outcomes (GBOs) and the 10-item Recovering Quality of Life tool (ReQoL-10) – for community mental health services. Reference Keetharuth, Brazier, Connell, Bjorner, Carlton and Taylor Buck17–19

Past attempts to implement routine outcome data gathering have struggled to engage with clinicians. A national survey of consultant psychiatrists in the UK in 2002 with 340 eligible responses found that only a small minority used outcome measures routinely. Reference Gilbody, House and Sheldon20 Numerous barriers have been identified to the uptake of routine outcome measurement in clinical practice. Clinicians have expressed difficulty in understanding the clinical relevance of measurement and concerns about lack of integration with information technology systems such as electronic patient records. Reference Jacobs and Moran21 Other concerns centre on the perceived intrusiveness of the measurement process, lack of infrastructure and fears that results could be used inappropriately for containing costs by excluding individuals from services. Reference Gelkopf, Mazor and Roe22

In our survey we sought to obtain up-to-date information on the views of psychiatrists who are Fellows, Members or Associates of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The results will inform the College’s policy on outcome measures and guide the work of the outcome measures working group.

Method

Development

We conducted a cross-sectional survey managed through the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics XM, Qualtrics, Provo, Utah, USA; https://www.qualtrics.com/en-gb/). We are senior members of the outcome measures working group at the Royal College of Psychiatrists and we developed the survey ourselves. The survey had four sections, covering current use of outcome measures, views on barriers and facilitators to the use of outcome measures, resources that psychiatrists need to support their use of outcome measures and an optional section seeking feedback on the College Report CR240. The survey was piloted with other members of the working group prior to distribution. The survey was approved by the Registrar of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, who were asked to agree to use of their anonymised data and responses.

Distribution and analysis

An electronic link to the survey was sent by email to all Fellows, Members and Associates registered on the College database on 22 January 2025. The survey was also advertised through other College channels, such as the members’ newsletter. The survey was closed to responses on 2 April 2025. Incomplete responses were excluded from the analysis. Quantitative data from closed questions were analysed using appropriate descriptive statistics and free-text responses were analysed thematically.

Results

Sample characteristics

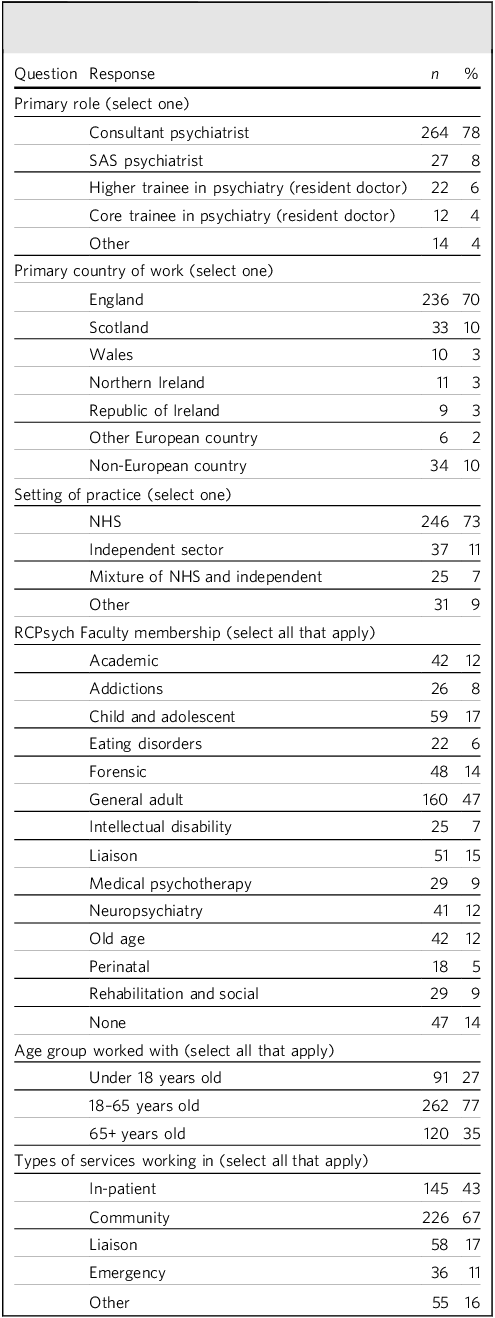

A total of 339 complete responses were received. Most respondents were consultant psychiatrists (78%), based in England (70%) and working primarily in the NHS (73%). The most common setting that respondents worked in was community mental health services (67%), followed by in-patient mental health services (43%) and liaison services in general hospitals. See Table 1 for more detailed sample characteristics.

Table 1 Characteristics of respondents to the survey (n = 339)

SAS, specialty and specialist; NHS, National Health Service; RCPsych, Royal College of Psychiatrists.

Current use of outcome measures

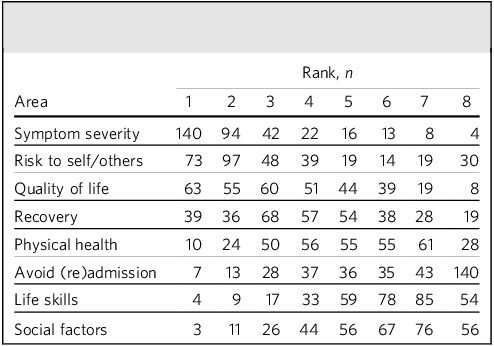

Respondents were asked to rank eight different outcome areas in terms of the importance of measuring each in their own practice. Symptom severity was most commonly ranked as the most important (n = 140; 41%), followed by risk to self/others (n = 73; 22%) and quality of life (n = 63; 19%). Life skills and social factors (such as employment and housing) were least frequently ranked as most important (n = 3 and n = 4 respectively; both 1%), and avoidance of admission/readmission was most frequently ranked as the least important (n = 140; 41%) (Table 2). Other areas that were identified as important included abstinence from substance use, ability to engage in treatment planning, side-effects of medication, family/carer support, family/carer quality of life, adherence to treatment, and interpersonal relationships. One respondent commented that the list was too focused on pathology and suggested that measures of self-esteem and self-efficacy should be prioritised. Another objected to being asked to rank the outcomes for all patients, highlighting that the relative importance fluctuates between individuals.

Table 2 Ranking of the importance of eight outcome areas by survey respondents (n = 339)

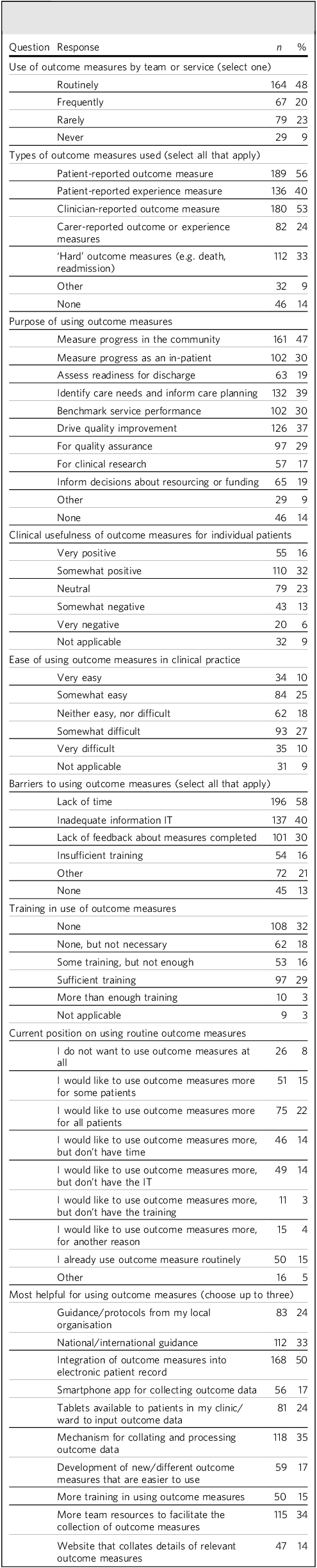

Almost half of respondents (n = 164; 48%) reported using outcome measures routinely. The most common type of measure that respondents reported using was a PROM (n = 189; 56%), followed by a CROM (n = 180; 53%). The most common ways that respondents reported using outcome measures in their practice were, first to measure their patients’ progress in the community (n = 161; 47%), second to identify needs and inform care planning (n = 132; 39%) and third to drive quality improvement (n = 126; 37%) (Table 3). Other reasons for using outcome measures reported by respondents included to measure their own performance as a clinician, to measure positive and negative effects of treatment, to satisfy commissioners and to ensure treatment is patient centred. Almost half of respondents found outcome measures clinically useful for their patients (n = 165; 49%). Respondents were roughly evenly divided about how easy they found outcome measures to use in their clinical practice.

Table 3 Survey respondents’ views on the use of outcome measures (n = 339)

IT, information technology.

Barriers and facilitators to using outcome measures

The most commonly cited barrier to using outcome measures was respondents’ lack of time in their job role to complete them (n = 196; 58%), followed by information technology preventing or limiting their use of outcome measures (n = 137; 40%) (Table 3). Half of respondents (n = 170; 50%) reported having received no training in using outcome measures, although over one-third of these felt it was not necessary to have any training for the outcome measures that they used. Of those who had received training, the majority received this through their employer (n = 102; 61%), the rest received it from an external organisation or from a variety of other sources, including colleagues, self-directed reading or even as part of the development team for particular measures. Only a small number of respondents reported that they did not want to use outcome measures at all (n = 26; 8%). Around double that number reporting they used outcome measures routinely (n = 50; 16%), with similar numbers reporting that they would like to use outcome measures more, but lacked time (n = 46; 14%) or information technology support (n = 49; 16%). Respondents reported that the most helpful action to help them use outcome measures would be the integration of the measures into the electronic patient records (n = 168; 50%), followed by a mechanism for collating and presenting outcome data (n = 118; 35%). More resources to collect outcome data (n = 115; 34%) and national guidance (n = 112; 33%) were also viewed as important by many respondents.

Free-text responses: themes

Three main themes were identified in free-text answers.

Theme 1: Need for outcome measures to be clinically meaningful and useful

The purpose of completing outcome measures was not clear for many respondents, who commented that they saw them as ‘box-ticking’ exercises, done to satisfy managers and commissioners. Respondents noted that measures were often completed only because they were mandatory, with data not being presented back to clinicians or used to inform care planning. The meaningful involvement of patients in rating and interpreting outcome measures was highlighted as important. Several respondents highlighted that scores could be at odds with clinical impressions, undermining confidence in measures. One commented that hard outcomes such as length of stay may not reflect the complexity of patients, where achieving stability and optimising quality of life in the context of severe mental illness is often the goal.

Respondents highlighted the need for repeated measures, with collation of data and feedback of results, ideally including graphical representation of change over time and longitudinal trends. Respondents also emphasised the importance of selecting specific measures for the particular population, for example in older adults employment may not be as relevant an outcome as in younger adults. Others highlighted that measures may not be culturally sensitive or suitable for different ethnic groups. Several respondents questioned whether it is possible to quantify patients’ experiences at all. Some felt that measures can be too generic and fail to capture the breadth of outcomes in all patients, for example in liaison psychiatry, where psychiatrists encounter a wide range of situations.

Some commented that patients appreciated the opportunity to complete measures, whereas other noted patients were wary of doing so. Several respondents emphasised the importance of PROMs and patient involvement in selecting suitable outcomes, but some noted the lack of suitable measures, and challenges to collecting reliable data from patients. Several commented that the act of asking patients to complete PROMs changed the tone of the consultation and may not be appropriate for certain groups or circumstances, such as younger people, who may be alienated by the formality of completing structured questionnaires, or people in a crisis, who may be further distressed when presented with a questionnaire. Several respondents highlighted the need for cultural change, where outcome measurement becomes routine practice.

Theme 2: Complexities and potential pitfalls of using aggregated outcome data

Some respondents commented that using aggregated scores could be misleading and that a measure’s psychometric properties may not be adequate to support service-level inferences. Some observed that competing incentives for patients and clinicians could influence the way measures are scored. Others cited the potential utility of outcome measures for research, quality improvement and service planning; however, they noted that to achieve this, systems need to be effective in capturing and processing the data. Some expressed concern that outcome measures could be used to justify reducing resources, although others pointed to their usefulness in comparing similar services. Some welcomed the idea of using outcomes to measure clinicians’ effectiveness, whereas others were wary of how attempts to measure individual clinicians’ performance might be misused. Respondents noted that, if scores are to be compared, they need to be filled in consistently and reliably. The data need to be complete and of good quality. Several reflected that employers did not appear to be interested in introducing or promoting the use of outcome measures, and without institutional buy-in they are unlikely to have an impact. Some commented that a lack of interrater reliability can limit usefulness of outcome measures when patients are seen by multiple clinicians.

Theme 3: The need to minimise the burden of outcome data gathering

Many respondents commented on the limited capacity of psychiatrists to spend time completing outcome measures, with potential opportunity costs of reduced clinical contact. Choosing measures that are quick to complete, involving other members of the multidisciplinary team and ensuring that technology supports the collection of responses were identified as facilitators that could minimise the burden on psychiatrists. Careful selection of the minimum number of measures would also help to limit the burden. Support from other members of the multidisciplinary team, such as care coordinators and assistant psychologists, was identified by some as useful in completing measures. Several respondents expressed their frustration with the erstwhile mental health clustering, feeling it was clinically unhelpful and time consuming. Some respondents felt that training was important, but others felt this was unnecessary and even indicated a problem with the outcome measure if it required extensive training to be useful.

Free-text responses: College support for members to use outcome measures

Respondents advanced a series of suggestions about what the Royal College of Psychiatrists could offer to support its members.

Training and access to information

Suggestions for training included masterclasses, courses, e-learning, books and videos. Some respondents suggested that all training should be suitable for the whole multidisciplinary team, not just psychiatrists. Others recommended the use of digital platforms such as mobile applications (apps) for College members or a QR code that could be given to patients that links to key information and resources on outcome measures. An alternative view from one respondent suggested that the College should not provide training, as good outcome measures should be intuitive and be usable without training.

Guidance

Many respondents suggested that specific guidelines would be helpful, such as a position paper, with a list of recommended measures for particular settings or populations. Several respondents emphasised the importance of clinical leadership by the College on the selection of measures, to ensure their relevance and ease of use. Some stated that the College should advocate for the mandatory use of outcome measures and their use in NHS benchmarking, and others highlighted the need to prioritise a small number of measures and promote standardisation. A few responses highlighted the importance of the College being clear about which measures are not useful, and working to avoid their imposition. Patient involvement was highlighted as important, including the need to provide information to patients and carers to increase their familiarity and skills in using outcome measures.

Research

Some respondents saw the College having a role in generating evidence on the benefits of outcome measures, with examples of how they have led to meaningful differences. Others wanted the College to examine the performance of common outcome measures in different populations. One respondent called for a national audit of outcome measures. Several respondents suggested the development of new measures to support specific patient groups, such as older people with dementia and adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ones that have a broader social perspective.

Other views

Some respondents expressed scepticism about the usefulness of outcome measures and suggested there should be more open discussions and active debate about whether they have a role in clinical practice at all. There were concerns that outcome measures detract from clinical time and that psychiatrists are increasingly expected to spend time on administration at the expense of patient contact. One response suggested that the College should make recommendations of what other work should be reduced to make time for outcome measurement. Many responses highlighted the need for adequate time and staffing levels to use outcome measures, with the College playing a role in advocating for these increased resources. When asked what else might be helpful in using outcome measures, many respondents emphasised the importance of administrative support and digital integration to collect, analyse and feed back the data from outcome measures.

Feedback on College Report CR240

Out of 330 respondents who chose to answer, 267 (80%) either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ with the principles in the College Report Outcome Measures in Psychiatry (CR240), with only 4% either disagreeing or strongly disagreeing. Other comments on the report included the need to mention carers and family members in the principles, and the need for a greater focus on individual patient care. Several respondents commented that the principles were aspirational and the College needs to develop a plan to influence practice on the ground.

Discussion

Key findings

This study is a cross-sectional survey of psychiatrists about their use of, and views on, outcome measures, conducted by the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ working group on outcome measures. Most of the 339 survey respondents were consultant psychiatrists, were working with working-age adults and were based in England. Almost half used outcome measures routinely and almost half were positive about the clinical usefulness of outcome measures for individual patients. Lack of time and inadequate information technology support were the most cited barriers to outcome measure use. Respondents reported that integration of outcome measures into electronic patient records, with a mechanism to collate and process those data, and more team resources to collect outcome data would be the most helpful facilitators to using outcome measures.

In free-text responses, respondents highlighted the need for outcome measures to be clinically meaningful, the complexities of using aggregate outcome data, and the need to minimise the burden of data collection for psychiatrists and other team members. Respondents called for better training and information resources on outcome measures; improved guidance at all levels, including guidance on which measures to use; and more research into the effectiveness of outcome measures and the development of measures in specialist areas where suitable tools are lacking.

Interpretation of results and comparison with existing literature

The results of the current study suggest that the routine use of outcome measures by psychiatrists is more widely embedded in practice compared with 25 years ago. A similar survey of 340 UK adult psychiatrists in 2000 reported rates of routine use of outcome measures to assess clinical change over time of between 4.7 and 11.2%, compared with 48% of respondents saying that they routinely use outcome measures in 2025. Reference Gilbody, House and Sheldon20 Although respondents were mostly positive about the clinical usefulness of outcome measures for individual patients, many expressed scepticism in the free-text comments about the use of aggregate outcome data, especially at a service level. The perception that outcome measures are a ‘tick-box exercise’ is not new and has been linked to a lack of feedback of outcome data to clinicians, previously described as ‘pouring valuable clinical information into a black hole’. Reference Jacobs and Moran21 Some respondents even feared that outcome measure data may be misused to castigate clinicians, cut funding or limit access to services, which echoes views reported elsewhere. Reference Gelkopf, Mazor and Roe22 Commissioners’ reliance on process measures, such as length of stay, may further contribute to clinicians’ antipathy towards measurement.

Although measurement-based care has some evidence to support its effectiveness, there remains a substantial gap between what is desirable in theory and what happens in practice. Reference DeSimone and Hansen23 Reducing the burden of collecting outcome data is a common concern across medicine and applies to measures reported by clinicians, patients and others. Reference Aiyegbusi, Cruz Rivera, Roydhouse, Kamudoni, Alder and Anderson24,Reference DiGiorgio, Ehrenfeld and Miller25 Recommendations to achieve this include the use of shorter measures, ensuring measures are relevant and designing administrative systems that support data collection. The importance of integrating outcome measures into existing electronic patient record systems has been widely reported elsewhere in medicine. Reference Mokanyk, Taylor, De la Garza Ramos, Tadepalli, Girasulo and Rossi26,Reference Neame, Reilly, Puthiyaveetil, McCann, Mahmood and Almeida27 Researchers have recommended that measures should be incorporated either directly into local records or through stand-alone systems that interface seamlessly with the local system. Reference Basch and Snyder28

Implications for policy, practice and research

Routine outcome data gathering is endorsed by the RCPsych which has established a working group on outcome measures and published guidance on this topic. Despite this, little was previously known about the wider experiences and views of UK psychiatrists and psychiatrists associated with the College on outcome measures. The current survey adds to our knowledge of how outcome measures are being currently used in mental health services mostly within the UK (based on where most of the respondents were from) and the perceptions of psychiatrists on their use. It also provides valuable feedback on how the College and other organisations can most effectively support the use of outcome measures.

The results from the current survey suggest that many psychiatrists in the UK are already using outcome measures and many feel positive about their use. However, serious reservations remain, with numerous barriers to the successful implementation of routine measurement in a way that benefits patients or enhances clinicians’ practice. A joined-up response is required from policymakers that emphasises the need for robust measurement systems to be embedded in, and align with, clinical practice. Measurement should focus on genuine outcomes that are important to stakeholders and not simply easy-to-quantify processes. Many respondents to our survey highlighted the need for a cultural shift to achieve this, which would involve organisations (such as NHS trusts), individual clinicians and teams, and patients and carers all recognising outcome measures as important and actively participating in measurement.

We would propose a model whereby outcome measures are chosen for relevance and ease of use, with the input of clinicians, patients and other stakeholders. These could then be integrated into the local electronic patient records, such that data collection is as simple as possible. Data from repeated measures over time could then be automatically processed to produce usable outputs, such as graphs, that are readily understandable to clinicians and patients. The use of aggregate data to inform benchmarking, service improvement and research is potentially transformative, but requires careful thought to avoid introducing perverse incentives. Aggregated data, when data quality is poor or response rates are low, should be used with caution, as they may not be generalisable or representative. The Royal College of Psychiatrists and other organisations have a role in providing guidance (including advising on which measures to use), developing training and guiding research into the implementation of outcome measures.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this survey is the first nationwide survey of psychiatrists’ views on outcome measurement in the UK for a quarter of a century. As a survey of Fellows, Members and Associates of the Royal College of Psychiatrists it was open to almost all doctors working in mental health services in the UK, and to psychiatrists in many other countries around the world, given the international nature of the College’s membership. Owing to the way that the survey was distributed it is not possible to calculate an exact response rate. Many invitations sent via email are likely to have been diverted to junk mail folders or otherwise misplaced. Equally, other respondents may have chosen to participate after seeing advertisements in social media and newsletters. The absolute number who responded is in line with similar surveys endorsed and disseminated by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. However, given the much larger number of psychiatrists and other doctors linked to the College, there is the possibility of response bias. Psychiatrists holding strong views about outcome measures, whether these are positive or negative, may have been more likely to complete the survey, owing to a desire for their views to be considered. As we included responses only from those who completed the whole survey (339/574; 59%) we did not include partial responses, which may have been systematically different (for example those who failed to complete the survey may be working in busier clinical settings). We only present descriptive statistics and did not attempt further analysis to explore associations in the data, as this was not felt to be meaningful. Given the short nature of most of the free-text responses, formal qualitative analysis using data management software was not deemed necessary and therefore was not conducted.

About the authors

Howard Ryland, MBBS, MSc, MA, DPhil, FRCPsych, is a consultant forensic psychiatrist with Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK, and an honorary senior clinical research fellow, Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Rahul Bhattacharya, MBBS, DPM, MSc, FRCPsych, is a consultant psychiatrist in the Tower Hamlets Directorate, East London NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK, and an honorary senior clinical lecturer, Centre for Psychiatry, Wolfson Institute of Preventative Medicine, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK. Jonathan Richardson, MBChB, MSc, FRCPsych, is a consultant old age psychiatrist and a chief clinical information officer with Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author, H.R., on reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We thank Thomas Denning from the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the members of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ outcome measures working group for their invaluable input in developing and disseminating this survey.

Author contributions

H.R., R.B. and J.R. all contributed substantially to the conception, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation. H.R. prepared the initial draft of this manuscript, with R.B. and J.R. reviewing and substantially contributing to the manuscript. All authors give permission for the final version to be published.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

At the time that this study was conducted, J.R. was the Associate Registrar for Outcomes and Payment Systems for the Royal College of Psychiatrists. H.R. and R.B. were co-vice-chairs of the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Working Group on Outcome Measures. R.B. is a member of the BJPsych Bulletin Editorial Board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this paper.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.