Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The 1987 Brundtland Report (Our Common Future), led by Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland, established the globally recognized definition of sustainable development: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The commission synthesized diverse research streams to elevate sustainable development as a vital field of study. Brundtland is since dubbed the “Mother of Sustainable Development.”Footnote 1

Nordic leadership in sustainability thinking has a longstanding scientific tradition. Nearly a century before the Brundtland Report, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius published the first academic article linking activities during the Industrial Revolution to climate change, “On the Influence of Carbonic Acid in the Air upon the Temperature of the Ground,” in 1896. His work laid the scientific foundations for understanding the greenhouse effect, demonstrating how atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) influences Earth’s surface temperature.Footnote 2 Arrhenius’s subsequent 1908 book, Worlds in the Making, expanded on these ideas, pioneering the concept that human industrial activities, specifically the burning of fossil fuels, could lead to long-term climate changes. This early Nordic contribution to climate science set crucial groundwork for later understanding of planetary boundaries in relation to climate change.Footnote 3

Sustainable Development

I first encountered the definition of sustainable development during an elective course in my American MBA program in the early 2000s. It resonated with me as a timeless and universal goal, offering a more profound and overarching purpose than the narrow focus on shareholder profit maximization emphasized elsewhere in my MBA program and prevalent in Corporate America.

Sustainable development represents a significant shift from the traditional economic models prevalent throughout the twentieth century, which focused almost exclusively on economic growth. Sustainable development recognizes the interconnectedness of economic development with pressing social and environmental challenges, including poverty, hunger, increasing inequalities, climate change, and the eradication of biodiversity. Addressing these intrinsically linked challenges demands a holistic, systems-based approach.

The period from the late eighteenth to the nineteenth century is characterized by profound industrialization and innovation that reshaped societies at an unparalleled pace and profoundly changed humankind’s relationship with the Earth. Beginning in the 1760s, the epicenter of the Industrial Revolution was England. It soon reverberated throughout Europe, the young US, and beyond, radically altering human beings’ everyday lives during the nineteenth century and after that. Characterized by a shift from piecemeal production by hand to mass production by machines in ever-growing factories, the Industrial Revolution brought about unparalleled advances in efficiency and accelerated economic development.

Yet as is often the case with revolutionary transformations, the advances of the Industrial Revolution came with unintended consequences. The industrial era heralded widespread environmental degradation. For the first time, humankind affected the Earth’s geology and ecosystems. As the twentieth century progressed, the need for a more holistic approach to development that integrated environmental, social, and economic dimensions became increasingly apparent. The concept of sustainable development was born of this need.

Systems Thinking: The Earth as a System

Sustainable development emphasizes the necessity of systems thinking.Footnote 4 The Brundtland Report highlighted that economic development is intertwined with environmental sustainability, where poverty and inequality contribute to and are exacerbated by environmental degradation.Footnote 5 It highlights the interconnectivity of critical issues, including population, food security, species loss, energy, industry, and urban development, advocating for integrated, holistic solutions.

The Brundtland Report built upon seminal works, such as Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring and Donella Meadows and colleagues’ The Limits to Growth, which warned that human activity associated with industrialization would exceed the Earth’s carrying capacity.Footnote 6

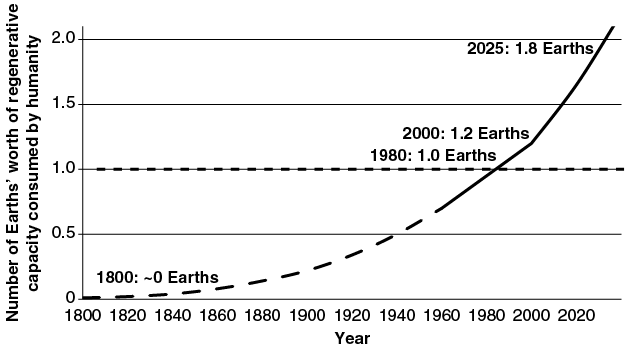

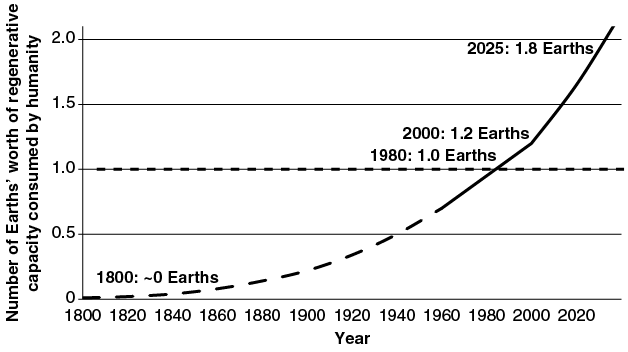

Since the early 1980s, humanity has consumed resources faster than the Earth can regenerate them – driving natural resource depletion, rising greenhouse gas emissions, and biodiversity loss. The 2004 Limits to Growth thirty-year update illustrated this starkly. Using data from Mathis Wackernagel and colleagues, published in “Tracking the Ecological Overshoot of the Human Economy,” it featured a striking graph showing the ecological footprint rising from just over 0.6 Earths’ worth of annual regenerative capacity in 1960 to 1.2 Earths’ worth by 2000.Footnote 7

As depicted in Figure 2.1 – which offers an expanded view of the graph from the Limits to Growth update – humanity’s impact was negligible at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution era but has since surged. By 2025, it reached an estimated 1.8 Earths, corresponding to Earth Overshoot Day falling on July 24 – the symbolic date of the year when humanity has already consumed the Earth’s full annual regenerative capacity.Footnote 8

Figure 2.1 Number of Earths needed to support human activity.

Patterns of overconsumption are deeply unequal worldwide. US citizens rank among the highest per capita consumers globally – if everyone consumed at the level of the average American, more than five Earths’ worth of regenerative capacity would be required. All of the world’s wealthiest nations, including all OECD and Nordic nations, exceed sustainable consumption levels.Footnote 9

Overconsumption is closely tied to wealth. The wealthiest 1 percent have a carbon footprint double that of the poorest 50 percent combined.Footnote 10 Alarmingly, research shows that the wealthiest individuals often view their consumption as fair. This perception gap is especially concerning given the disproportionate influence the wealthiest individuals have over global policy decisions.Footnote 11 Furthermore, as lower-income nations continue to develop, their consumption levels are also rising, further intensifying pressure on the planet’s finite resources.

Addressing the global crisis of overconsumption necessitates a fundamental reassessment of our production and consumption models. Consumption levels have drastically altered the planet, and many scientists now refer to the present as the Anthropocene epoch, defined by the dominant impact of human activity on Earth’s geological history (from anthropo, for man, and cene, for new).Footnote 12 Before this was the Holocene epoch, which began 11,700 years ago after the last ice age, offering stable climates that allowed human civilization to flourish. Preceding the Holocene was the Pleistocene epoch from about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. The Pleistocene epoch posed significant challenges for early humans, with repeated ice ages and harsh conditions that made survival difficult due to extreme cold, food scarcity, and unstable environments. While the official designation of the current epoch is debated, it is evident that humanity’s ability to alter Earth’s systems now significantly poses severe risks to human survival and well-being.

Earth: Humanity’s Endowment

Earth is humanity’s ultimate endowment – an irreplaceable asset that sustains all life and human civilization. Like any precious endowment, it is passed from generation to generation, with each inheritor serving as both beneficiary and trustee.

When a financial endowment is responsibly stewarded, it regenerates a stream of financial resources in perpetuity from which current and future generations benefit. Responsible stewardship entails withdrawing only resources generated from interest and not touching the principal of the asset.

Consider, for example, an endowment of $100 million. At a 4 percent interest rate, commonly accepted in financial management as a sustainable rate minimizing the risk of depleting the principal, such an endowment can regenerate $4 million annually in perpetuity. By withdrawing only the interest generated, the principal is preserved over the long term while providing a reliable revenue stream from interest to live on for each generation of benefactors. However, if a beneficiary extracts more than the $4 million annually generated through interest, the principal is eroded, and the asset is impaired. As a result, the endowment’s regenerative capacity is diminished. For example, imagine a beneficiary extracting $20 million from the $100 million endowment in one year. That $20 million would be $4 million from interest and $16 million from the principal. The value of the endowment is thereby reduced to $84 million.

While the present beneficiary may benefit from their heightened withdrawals by taking from the endowment’s principal, they are effectively stealing from all future beneficiaries – an $84 million endowment only regenerates $3 million annually in interest.

This endowment metaphor parallels environmental scientists’ conceptualization of Earth’s resources: as “stocks” (like an endowment’s principal) and “flows” (like the interest generated). All existing trees on Earth represent a stock, while the annual growth of new trees represents a flow. Similarly, healthy soil is a critical stock that can take centuries to build, generating annual flows of food and biomass. Biodiversity represents another crucial stock, with flows that include vital ecosystem services and medical innovations. More than half of cancer drugs have been discovered from natural sources, with compounds from plants, microorganisms, and marine life providing breakthrough therapies.Footnote 13 While advances in artificial intelligence enhance our ability to identify promising compounds in nature, the accelerating loss of biodiversity through habitat destruction and climate change permanently eliminates potential discoveries that could cure humanity’s most devastating diseases. These natural stocks – our forests, soils, freshwater bodies, oceans, and biodiversity – create vital flows that sustain life: carbon sequestration, food production, air and water purification, and life-saving medicines.

Herman Daly, a pioneering ecological economist, emphasized this distinction between stocks and flows as fundamental to understanding sustainability.Footnote 14 Just as an endowment trustee must distinguish between drawing down principal and living off generated interest, environmental scientists differentiate between depleting Earth’s stocks and sustainably harvesting its flows. When stocks are responsibly stewarded, these flows continue indefinitely. However, every year that humankind consumes more than Earth regenerates, its stocks are depleted and its regenerative capacity diminished.

The economic costs of failing to act as responsible trustees of our planetary endowment are increasingly conspicuous. According to a 2024 study published in Nature, climate change impacts will reduce global economic income by 19 percent within the next twenty-six years. Annual damages are estimated at $38 trillion in 2049 and grow with every passing year of increasing atmospheric CO2 ppm levels.Footnote 15 Harvard economist Adrien Bilal asserts, “By the end of the century, people may well be 50 percent poorer than they would’ve been if it wasn’t for climate change,”Footnote 16 based on his working paper with Diego Känzig, an economist at Northwestern University.Footnote 17

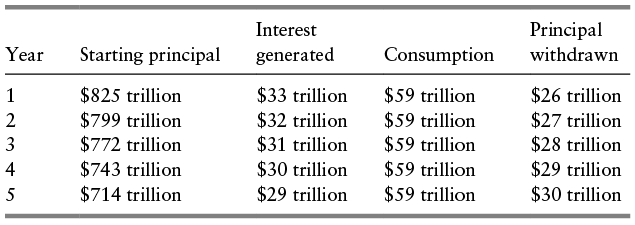

To further illustrate the Earth as an endowment metaphor through a numerical example, we can draw upon the 1997 study published in Nature. Robert Costanza and colleagues estimated the total value of ecosystem services provided by Earth’s biomes – effectively Earth’s annual “interest generated” – at $33 trillion, nearly double the global gross national product (GNP) of $18 trillion at that time. This valuation underscored the immense economic importance of natural ecosystems and the devastating costs of their degradation.Footnote 18

Using Costanza et al.’s valuation of Earth’s annual ecosystem services as our starting point, we can further develop the Earth endowment metaphor to illustrate the consequences of overconsumption. If we treat Earth’s annual ecosystem services of $33 trillion as “interest” generated by our planetary endowment and apply a standard endowment interest rate of 4 percent, we arrive at an Earth “principal” value of $825 trillion ($33 trillion ÷ 0.04). While this arbitrary calculation vastly simplifies Earth’s complex systems and their varying regeneration rates, it will illustrate how overconsumption compounds over time to erode Earth’s regenerative capacity.

Humankind currently consumes resources at about 1.8 times Earth’s annual regenerative capacity. In the endowment metaphor, this equates to withdrawing 7.2% annually (4% × 1.8). While $33 trillion could be sustainably withdrawn each year (at 4%), humankind currently withdraws $59 trillion. The excess $26 trillion comes directly from Earth’s principal Table 2.1.

| Year | Starting principal | Interest generated | Consumption | Principal withdrawn |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | $825 trillion | $33 trillion | $59 trillion | $26 trillion |

| 2 | $799 trillion | $32 trillion | $59 trillion | $27 trillion |

| 3 | $772 trillion | $31 trillion | $59 trillion | $28 trillion |

| 4 | $743 trillion | $30 trillion | $59 trillion | $29 trillion |

| 5 | $714 trillion | $29 trillion | $59 trillion | $30 trillion |

As withdrawals routinely exceed interest generated, Earth’s principal is continually drawn down and its regenerative capacity further erodes – visible in the declining annual interest generated. While alarming, this example actually understates the challenge, as global consumption is accelerating beyond the current 1.8 rate. On current trajectories, humanity could be consuming the equivalent of two Earths’ annual regenerative capacity by 2030 or soon thereafter, with no slowdown in sight.

Moreover, while the endowment metaphor is useful for illustration, it has a critical limitation: It assumes linearity. Earth’s systems, in contrast, contain tipping points – critical thresholds beyond which changes become both dramatic and irreversible, with potentially devastating consequences for human civilization. These tipping points represent a fundamental difference between financial and ecological systems: While a depleted financial endowment might be rebuilt over time, a crossed ecological tipping point permanently alters Earth’s life-supporting capacity.

Consider three critical tipping-point examples: The Greenland Ice Sheet may irreversibly melt if warming exceeds 1.5–2°C; the Amazon Rainforest could transform from carbon sink to carbon source, shifting to dry savannah with continued deforestation; and the Atlantic Ocean circulation may collapse, fundamentally altering global climate patterns.Footnote 19 These potential system changes underscore the urgency of correcting humanity’s consumption to levels within planetary boundaries.

While subject to debate, many scientists assert Earth is experiencing the “sixth mass extinction,” representing another critical tipping point in Earth’s systems. Unlike previous mass extinctions caused by natural events like asteroid impacts and volcanic eruptions, this extinction is unique – for the first time, Earth’s inhabitants are driving their own extinction crisis. Species are now disappearing at rates up to 1,000 times greater than the natural background extinction rate. Each lost species weakens the resilience of Earth’s interconnected ecosystems, further compromising its capacity to support human civilization.Footnote 20

Each of us is a trustee of humanity’s sole life-supporting endowment: Earth. While we all share responsibility, some individuals, institutions, and nations wield far greater influence over the fate of humanity’s endowment. How effectively we govern ourselves – particularly those with outsized influence over Earth’s systems – will determine whether future generations judge us as responsible trustees of their inheritance … or not.

Nordic Sustainability Contributions

The Nordic region has pioneered numerous sustainability innovations, from philosophical frameworks to practical policies. The Brundtland Report sparked global efforts to tackle sustainable development challenges. The following examples showcase several more key contributions with Nordic connections that have had significant global influence.

Environmental Protection Agencies

Recognizing the interconnected challenges of economic growth and environmental sustainability, in the 1960s and early 1970s, Nordic nations established some of the world’s first national environmental protection agencies within their respective governments. In 1967, Sweden created the world’s first national environmental protection agency (Statens Naturvårdsverket / Nature Protection Agency), and by the early 1970s, Denmark, Finland, and Norway had followed suit. These agencies were tasked with developing and enforcing stringent environmental regulations, monitoring pollution levels, and promoting public awareness about the ecological impacts of industrialization. The Nordic agencies demonstrated global leadership by actively participating in international environmental dialogues and treaties, notably through initiatives like the 1974 Nordic Environmental Protection Convention that resulted in the first legally binding international convention addressing transboundary pollution.Footnote 21

Deep Ecology

In the 1970s, Norwegian philosopher Arne Næss introduced the concept of “deep ecology,” advocating a profound shift in human–nature relationships from exploitation to recognition of nature’s intrinsic value. Næss was inspired by Western philosophical traditions, his ecological research, and the environmental consciousness ignited by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring. His work aimed to fundamentally reshape how humanity views and interacts with the natural world.

Næss contrasted deep ecology with “shallow” ecological thinking, which considers living things merely as resources for industrialization, their value determined solely by the marketplace.Footnote 22 In contrast, he argued that all forms of life – human, animal, plant, and beyond – deserve respect as ends in themselves. Deep ecology emphasizes the interdependence of all life forms and calls for acknowledging the interconnectedness that sustains the planet.

While Næss formalized deep ecology, the concept of nature’s intrinsic value has long existed in Indigenous philosophies. Deep ecology inspires circular economy innovations by emphasizing respect for nature’s regenerative systems and promoting sustainability as a core principle rather than an afterthought.Footnote 23

Circular Economy Practices

The Nordic region is globally recognized for its leadership in circular economy practices, with comprehensive deposit-return systems for beverage containers as a defining achievement. Tracing their origins back to material shortages during World War I, the Nordic nations began pioneering nationwide deposit-return programs in the 1980s, setting the global standard for the recycling and reusing of glass, aluminum, and plastic containers. With return rates exceeding 90 percent, these systems drastically reduce waste, preventing millions of bottles and cans from ending up in landfills or oceans. The success of these deposit-return systems hinges on cooperation across the beverage industry, active collaboration with governments, and the establishment of nonprofit, nongovernmental entities that govern the take-back systems. These nongovernmental entities work with beverage producers, retailers, governments, and consumers to ensure effective operation and regulatory compliance, set deposit rates, and oversee the overall financial viability of the system.

The deposit-return systems rely on the active involvement of shop owners and grocery stores, where take-back machines are strategically located at the point of sale. This setup provides convenience for consumers returning containers and strengthens the collection network, effectively embedding circular economy practices within daily life. Shop owners maintain these machines and facilitate the return process, illustrating the collaborative efforts across multiple sectors. Consumers are incentivized through significant deposit rates – ranging from approximately 10–45 cents, depending on the container’s size and material – paid at purchase and reclaimed upon returning the empty bottles and cans. This financial incentive encourages high participation rates and significantly increases the purity of the collected materials, unlike commingled recycling systems. By securing a steady supply of high-quality secondary materials, these deposit-return systems provide a crucial risk-mitigation strategy for the beverage industry, especially as access to virgin materials becomes increasingly uncertain.

As a result, the Nordic bottle and can take-back systems are now recognized as global benchmarks for effective circular economy practices. Other industries, including apparel and electronics, are increasingly examining these models as they seek to implement circular economy systems for reclaiming valuable materials, mitigating supply chain risks, and advancing sustainability objectives.

Renewable Energy

The Nordic region is a recognized global leader in renewable energy, with significant advancements in wind power, geothermal energy, hydroelectricity, and other clean energy sources. Denmark has been a pioneer in wind energy since the 1970s. It currently generates nearly 50 percent of its electricity from wind farms, both onshore and offshore, with an ambitious goal of achieving 100 percent renewable energy by 2050. Iceland, meanwhile, harnesses its unique geological resources, producing nearly 100 percent of its electricity from renewable sources, primarily geothermal and hydropower, making it one of the greenest energy producers globally. Finland and Sweden have invested heavily in diverse renewable energy sources, particularly bioenergy, wind, and solar power, with Sweden setting an ambitious target to achieve 100 percent renewable electricity production by 2040. Norway, known for generating over 90 percent of its electricity from hydroelectric power, also boasts the highest rates of adoption of electric vehicle (EV) globally. This means that most of Norway’s EVs are charged using clean, renewable hydroelectricity. Norway’s renewable energy leadership is often critiqued for its contradiction: despite domestic reliance on clean energy, it remains a significant fossil fuel exporter, keeping company with Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the US, highlighting the complexities and hypocrisies of the green energy transition.

Carbon Taxes

The Nordic nations have been global frontrunners in implementing carbon taxation, recognizing its importance in driving the transition to a low-carbon economy. A carbon tax is a fee imposed on the burning of carbon-based fuels like coal, oil, and gas. It aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by making fossil fuel consumption more expensive. This market-based approach incentivizes individuals and businesses to reduce their carbon footprint, invest in renewable energy, and adopt more sustainable practices.

Finland was the first in the world to introduce a carbon tax in 1990, setting a precedent for using economic policy to address climate change. Following closely, Sweden adopted its carbon tax in 1991, initially set at SEK250 (approximately $40) per ton of CO2. It later increased to around SEK1,200 (about $130), making it one of the highest carbon taxes globally. Norway also established its carbon tax in 1991, and Denmark followed in 1992. More recently, Iceland implemented a carbon tax in 2010, targeting sectors outside the European Union Emissions Trading System. These carbon taxes across the Nordic region have been pivotal in reducing emissions and promoting the adoption of renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies. The success of these policies has inspired similar initiatives worldwide, reinforcing the Nordic countries’ role as leaders in global sustainability efforts.

Labor Policies for the Green Transition

A successful green transition requires technological innovation, environmental policies, and a proactive approach to labor markets, where labor unions play a pivotal role. In the Nordic region, the “flexicurity” model – an integration of labor market flexibility and social security – ensures workers are supported through active labor policies, including retraining programs, educational opportunities, and social safety nets that facilitate the shift toward green jobs. Labor unions, such as the Danish Trade Union Confederation (Fagbevægelsens Hovedorganisation, FH), act as key enablers by advocating for a socially just transition and actively participating in policy-making. For instance, to understand the workers’ perspective on the green transition, FH commissioned a qualitative study to explore Danish workers’ views on a fair and balanced transition. This research revealed both opportunities and concerns and helped guide policy to ensure workers are not merely losing unsustainable jobs but are being retrained and reemployed in future-oriented sectors. Involving unions helps frame the green transition as a collective opportunity rather than a threat, ensuring workers feel supported and included. By providing job security, advocating for worker rights, and fostering upskilling in green industries, Nordic labor unions help promote societal acceptance of the green transition, aligning it with the region’s commitment to maintaining a robust welfare state. This strategy demonstrates how labor unions and proactive labor policies can drive the green economy forward while fostering inclusivity and equitable progress.

The Natural Step

Founded in Sweden in 1989, The Natural Step (TNS) was inspired by the Brundtland Report’s principles. Developed by cancer scientist Karl-Henrik Robèrt, TNS offers a framework for sustainable practices in various sectors, emphasizing economic and environmental health interdependence.Footnote 24 It instructs, “If Earth is a system, we’d better understand the conditions it needs to keep running the way we like it.”

TNS provides a framework of the following principles necessary for achieving sustainability:

In a sustainable society, nature is not subject to systematically increasing:

o concentrations of substances from the Earth’s crust (such as fossil CO2 and heavy metals),

o concentrations of substances produced by society (such as antibiotics and endocrine disruptors),

o degradation by physical means (such as deforestation and draining of groundwater tables).

And in that society:

o there are no structural obstacles to people’s health, influence, competence, impartiality, and meaning.Footnote 25

Corporations such as IKEA, Scandic Hotels, Nike, and Interface have incorporated TNS principles into their business operations, reflecting a commitment to sustainable practices.Footnote 26 Cities across the Nordics are guided by TNS principles, like the small municipality of Övertorneå, Sweden, whose government operations became fossil fuel-free in the early 2000s by adopting an integrated, systems-thinking approach. The systems-thinking approach overcame the challenges of conflicting priorities, scarce resources, and turf battles.Footnote 27 US cities like Madison, Wisconsin, adopted TNS as a guiding principle, stating, “This framework provides a model and a common language that facilitates cooperation in working toward the goal of sustainability. It is grounded in ‘systems thinking,’ which recognizes that what happens in one part of a system affects every other part.”Footnote 28

Industrial Symbiosis

Industrial symbiosis is a foundational concept in industrial ecology where different industries collaborate to enhance their competitive advantage through the physical exchange of materials, energy, water, and by-products. This approach transforms the waste or by-products of one industry into valuable resources for another, fostering mutual benefits and promoting environmental sustainability. The most notable example of this practice is the Kalundborg Eco-Industrial Park in Denmark, recognized as the world’s first industrial symbiosis formally established in 1972. This pioneering initiative has become a global model, showcasing how a circular approach to production can lead to substantial economic and environmental gains.

Located in Kalundborg, Denmark, the Kalundborg Symbiosis involves seventeen public and private companies that engage in resource-sharing and waste minimization. Nordic corporate giants, including Novo Nordisk, Novozymes, and Ørsted, are key players in this collaboration. A feature of this industrial symbiosis is the network of large green pipes that transport steam from the Asnæs Power Station to several partner companies. Initially, the power station had an overcapacity of steam, which has since become a primary product, with electricity as a by-product. This steam is crucial for various processes at companies like Novozymes and Novo Nordisk, including cleaning, sterilization, and distillation.

Moreover, the Kalundborg Symbiosis extends its innovative practices through various initiatives. For instance, Novozymes produces biogas from process wastewater, which powers a large engine and supplies electricity to thousands of Danish households. Novo Nordisk’s production processes generate residues converted into valuable biogas and fertilizers. Ørsted supplies deionized water for steam production for its operations and those of Kalundborg Refinery. Other notable collaborations include using surplus yeast slurry from Novo Nordisk to be converted into biogas at Kalundborg Bioenergy and Kalundborg Utility and treating wastewater used to produce district heating. Additionally, the city of Kalundborg benefits from district heating produced by Asnæs Power Station, which also supplies hot water to Inter Terminals for heating oil tanks.

Kalundborg’s industrial symbiosis fosters innovation and trust within the community, significantly reducing CO2 emissions. It also demonstrates how sustainability and profit can coexist and serves as a powerful inspiration for the global green transition.Footnote 29

New Nordic Cuisine Movement

In 2004, Danish chef and entrepreneur Claus Meyer spearheaded the establishment of the “Manifesto for the New Nordic Cuisine,” which emphasized sustainability, respect for nature and animal welfare, and democratic values. Meyer assembled a cohort of leading Nordic chefs, including René Redzepi, with whom he had co-founded the renowned Noma restaurant in 2003. Together, they crafted a ten-point manifesto that set forth the guiding principles of this culinary revolution. The first point articulated the movement’s core objective: “To express the purity, freshness, simplicity, and ethics we wish to associate with our region.”Footnote 30

Noma’s global recognition, earning the World’s Best Restaurant title in 2010, 2011, 2012, and 2014, brought unprecedented international attention to New Nordic Cuisine and solidified its status as a global culinary movement. Its influence extended beyond fine dining, inspiring initiatives such as the Nordic Children’s Kitchen Manifesto in 2013, which declared, “Every Nordic child has the right to learn how to cook good, healthy food.”Footnote 31 This movement sparked numerous satellite efforts, including schoolchildren growing their own vegetables, chefs training public school cafeteria staff to prepare daily meals from scratch, the removal of vending machines from schools, and comprehensive campaigns to tackle food waste.

The New Nordic Cuisine movement has evolved to embrace a plant-forward approach, emphasizing locally sourced ingredients and sustainable gastronomy while recognizing the environmental benefits of reduced meat consumption.

The impact of the New Nordic Cuisine movement extends into public policy, with the Nordic region now leading in sustainable food initiatives. In 2018, Solutions Menu: A Nordic Guide to Sustainable Food Policy was published, outlining twenty-four innovative policies across the region, such as universal free school meals, the integration of organic food in hospitals, and ambitious programs to reduce food waste. The guide attributes the “secret ingredients” of Nordic success to the implementation of food policies that are evidence-based, democratic, progressive, open, holistic, and sustainable. Reflecting on the broader implications of this culinary transformation, Claus Meyer asserts, “I believe that the way in which we have transformed food culture in the Nordic region can be an inspiration to many other countries in the world. Such a culinary transformation can be a weapon against both poverty and unhealthiness.”Footnote 32

Nature-Based Solutions

The Nordic region is recognized as a global leader in nature-based solutions, showcasing a commitment to integrating natural systems into both urban and rural landscapes to enhance sustainability. Nordic countries have implemented policies and practices that preserve biodiversity, combat climate change, and promote human well-being. A notable example is Finland and Sweden’s large-scale forest conservation and sustainable management efforts. Both countries, accounting for a significant portion of Europe’s forests, have adopted practices aligned with the Forest Stewardship Council certification standards since the early 2000s. These standards prioritize ecological functions, including carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation, and water regulation, while supporting local economies.

Nordic cities increasingly embrace nature-based solutions in urban planning efforts. Copenhagen’s Climate Adaptation Plan was launched in 2011 following a severe cloudburst in July of that year, with over 135 millimeters (5.3 inches) of rainfall within a couple of hours, causing extensive flooding and economic damages estimated at around $1 billion.Footnote 33 This event prompted the city to adopt nature-based solutions to manage stormwater, including green roofs, permeable surfaces, and urban wetlands to reduce flood risks and mitigate heat island effects. Nature-based solutions are vital to climate adaptation and resilience. Similarly, Oslo’s 2019 “City Tree Policy” promotes planting native species throughout the city, improving air quality and carbon capture while enhancing residents’ connection to nature.

Nordic countries, particularly Norway and Finland, are actively enhancing their engagement with the Indigenous Sámi to promote sustainable practices and nature-based solutions. The Sámi, with their deep-rooted traditions of living in harmony with the Arctic environment, offer crucial insights into sustainable reindeer herding, land management, and biodiversity conservation. While there has been an increase in Sámi participation in environmental policy, more work is needed to address power imbalances and ensure their perspectives are fully integrated into decision-making processes.

In 2022, the Nordic Ministers for the Environment and Climate adopted the “Nordic Ministerial Declaration on the Strengthening of Nature-Based Solutions in the Nordic Region,” emphasizing nature-based solutions to address climate change, biodiversity loss, and human welfare challenges.Footnote 34

Planetary Boundaries

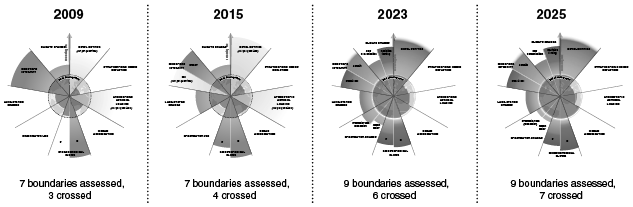

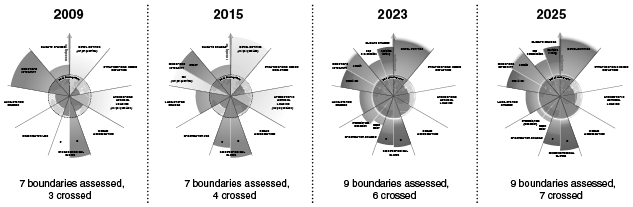

Swedish scientist Johan Rockström led a group of scientists to identify the processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth as a system. The Stockholm Resilience Centre was founded in 2007 by Rockström and colleagues – a global hub for leading climate scientists and experts in climate action – and the groundbreaking concept of “Planetary Boundaries” launched in 2009.Footnote 35 Planetary boundaries have become a foundational concept for global discussions on sustainability.

Building upon the Brundtland Report and The Limits to Growth, Rockström and colleagues portrayed the Earth as a finite system, delineating nine vital planetary boundaries to illustrate the system’s limits and relate them to considerations of fulfilling human needs. In the Stockholm Resilience Centre’s words, “The planetary boundaries concept presents a set of nine boundaries within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come.” The nine planetary boundaries are climate change, biosphere integrity, chemical pollution and the release of novel entities, stratospheric ozone depletion, ocean acidification, freshwater use, land-system change, nitrogen and phosphorus flows to the biosphere and oceans, and atmospheric aerosol loading. To the degree that any of the nine planetary boundary limits are exceeded, humankind is operating the Earth at an unsustainable level. Transgressing any of these boundaries could generate abrupt or irreversible environmental changes, compromising future generations’ ability to meet their needs.

Planetary boundaries are the Earth’s upper control limits (UCLs), representing thresholds that must not be crossed to maintain system stability for humankind.

In 2023, all nine planetary boundaries were quantified for the first time and published in a Science Advances article titled “Earth Beyond Six of Nine Planetary Boundaries.” Alarmingly, the 2023 assessment found that Earth was operating beyond the safe limits for six of these critical boundaries, including climate change and biosphere integrity, which measures genetic diversity and species extinction rates – breaching the biosphere integrity boundary risks irreversible biodiversity loss and the disruption of essential ecosystem services, such as food production and water purification, while increasing the likelihood of global health crises, such as pandemics.Footnote 36 In September 2025, an even more sobering update was released showing that Earth is now in excess of seven of the nine planetary boundaries, with ocean acidification added to the list.Footnote 37 Figure 2.2 illustrates how key Earth system processes have moved further outside the safe operating space for humanity, reflecting the expanding breach of planetary boundaries.

Figure 2.2 Planetary boundaries.

Figure 2.2Long description

Triptych of radial charts illustrates how humanity’s pressure on nine planetary boundaries has increased from 2009 to 2023. Each boundary is represented as a wedge radiating outward from a central circle labeled safe operating space. The degree to which each wedge extends beyond the safe zone indicates the extent of transgression.

In 2009, seven boundaries were assessed, and three were crossed: climate change, biosphere integrity, and biogeochemical flows. In 2015, seven boundaries were assessed; four were crossed, with worsening biosphere integrity and biogeochemical flows.

In 2023, all nine planetary boundaries were quantified. Six are now breached: climate change, biosphere integrity, novel entities, biogeochemical flows, land-system change, and freshwater change. Stratospheric ozone, ocean acidification, and atmospheric aerosol loading remain within limits.

The radial layout highlights the expanding breach of boundaries with red-orange shading and emphasizes the narrowing safe operating space for humanity.

The Planetary Health Check Report, first launched in 2024, now provides an annual dashboard that quantifies the current status of each planetary boundary.Footnote 38 With it, Rockström emphasized, “Stewardship of the planet is necessary in all sectors of the economy and in societies, for security, prosperity and equity. By quantifying the boundaries for a healthy planet, we provide policy, economics and business with the tools needed to steer away from unmanageable risks.”Footnote 39

The Planetary Boundaries Science initiative focuses on solutions and celebrates past successes where transgressions of planetary boundaries have been effectively addressed. One notable success story is the global response to the ozone hole discovery in 1985, which led to the 1987 Montreal Protocol and national policies phasing out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).Footnote 40 In response to scientific evidence from the 1970s highlighting the detrimental effects of CFCs and in anticipation of state regulations, DuPont developed hydrofluorocarbons, reducing harm to the ozone layer. This proactive innovation by DuPont, driven by the anticipation of future profits following regulations banning CFCs and the effective interaction between the state’s ‘visible hand’ and the market’s ‘invisible hand,’ underscore a symbiotic relationship that facilitated the rapid phase-out of CFCs.Footnote 41 The subsequent recovery of the ozone layer demonstrates that concerted international cooperation between governments and the private sector can indeed reverse environmental degradation. Now, the planetary boundary for stratospheric ozone depletion is safely within limits, serving as a powerful model for addressing other exceeded boundaries.

More recently, the Stockholm Resilience Center has emphasized the importance of integrating Indigenous knowledge into solutions for pressing sustainability challenges. Many Indigenous communities have developed sustainable stewardship practices over generations, offering invaluable insights into living in harmony with the natural world. The initiative aims to restore Earth’s systems to a safe operating space, drawing upon innovative and time-tested solutions.

SDGs

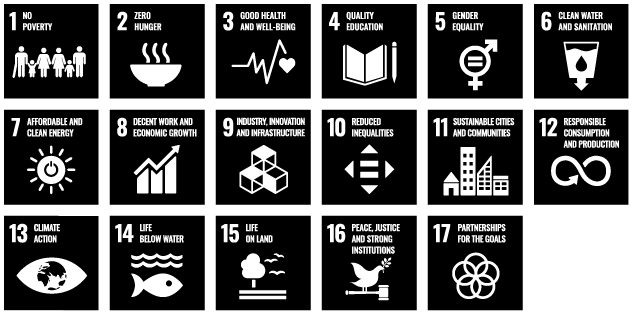

Launched in 2015, the SDGs represent the most significant global initiative to further the cause of sustainable development, as outlined in the Brundtland Report. The SDGs comprise seventeen interconnected goals: SDG #1 “No Poverty,” SDG #2 “No Hunger,” SDG #3 “Good Health and Well-Being,” SDG #4 “Quality Education,” SDG #5 “Gender Equality,” SDG #6 “Clean Water and Sanitation,” SDG #7 “Affordable and Clean Energy,” SDG #8 “Sustained, Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work for All,”Footnote 42 SDG #9 “Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure,” SDG #10 “Reduced Inequalities,” SDG #11 “Sustainable Cities and Communities,” SDG #12 “Responsible Consumption and Production,” SDG #13 “Climate Action,” SDG #14 “Life Below Water,” SDG #15 “Life on Land,” SDG #16 “Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions,” and SDG #17 “Partnerships for the Goals.” Figure 2.3 presents the SDGs.

Figure 2.3 SDGs.

Figure 2.3Long description

A row grid of 17 black-and-white square icons, each labeled with a goal number and name, represents the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Each icon includes a symbolic image. The SDGs are as follows:

1. No Poverty - a family with children and an elderly figure.

2. Zero Hunger - a steaming bowl.

3. Good Health and Well-Being - a heart and cardiogram line.

4. Quality Education - an open book and a pencil.

5. Gender Equality - an equal sign within a gender symbol.

6. Clean Water and Sanitation - a water droplet in a glass.

7. Affordable and Clean Energy - a sun with a power button.

8. Decent Work and Economic Growth - a rising bar chart and arrow.

9. Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure - interlocking cubes.

10. Reduced Inequalities - arrows pointing to an equal sign.

11. Sustainable Cities and Communities - buildings and a house.

12. Responsible Consumption and Production - circular loop arrow.

13. Climate Action - an eye containing a globe.

14. Life Below Water - a fish and waves.

15. Life on Land - a tree and birds.

16. Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions - a dove with olive branch and a gavel.

17. Partnerships for the Goals - five interlocking rings forming a flower-like symbol.

The 193 Member States of the United Nations unanimously adopted the SDGs in September 2015 at the UN Summit. All member states have committed to achieving the SDGs by 2030, making the SDGs a global framework for development across nations at all stages of development. The deliberations and consensus-building processes leading up to the SDG launch involved governments, civil society, and the business community.Footnote 43 The result is a globally recognized framework representing the world’s most pressing social, environmental, and economic challenges. The SDGs are described as the world’s most comprehensive materiality assessment.

The SDGs represent a global effort with deep Nordic ties. The basis for the SDGs is the Brundtland definition of sustainable development. The iconic packaging of the SDGs also has Nordic roots, as Swedish designer Jakob Trollbäck designed the SDGs’ vibrant and distinctive logos. The attractive SDG packaging has proven vital in helping propel the SDGs as a common global language.Footnote 44

The Nordic nations’ success in implementing the SDGs offers practical lessons for realizing sustainable capitalism. For example, Denmark’s 2024 agricultural carbon tax – the world’s first – demonstrates how democratic processes can create market mechanisms that internalize environmental costs while maintaining economic competitiveness. The policy emerged through Denmark’s tripartite negotiation system, where farmers, labor unions, and government representatives collaborated to design a system that both reduces emissions and supports agricultural innovation. This exemplifies how democratic capitalism can align market incentives with sustainability goals through inclusive stakeholder engagement.

The SDGs provide a framework for a holistic, systems-thinking approach to explore the connections among various sustainability challenges. Many of these connections are readily evident through the SDG framework. For example, SDG #1 “No Poverty” is directly connected with SDG #8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth,” because good jobs and decent work are the best way to alleviate poverty. SDG #13 “Climate Action” clearly connects with SDG #7 “Affordable and Clean Energy,” because the climate crisis demands an energy infrastructure enabling access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy.

Beyond obvious links, the SDGs also involve more subtle interdependencies. Educating girls, a combination of SDG #5 “Gender Equality” and SDG #4 “Quality Education,” is one of the most effective ways to address SDG #8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth” and SDG #3 “Good Health and Well-Being.” Girls who receive education are likely to earn higher wages and experience upward mobility, thereby fostering economic growth. They are less likely to marry as children or against their will. Their agricultural plots are more productive and their families are better nourished. A less apparent connection is that educating girls is one of the most effective means to tackle SDG #13 “Climate Action.” As Project Drawdown demonstrates, educated girls and women are “more effective stewards of food, soil, trees, and water.”Footnote 45 Educated women possess enhanced resilience and a greater capacity to handle shocks from natural disasters and extreme weather events, equipping them and society at large to confront the impacts of climate change.

The SDGs have effectively framed emerging global challenges, demonstrating their adaptability and relevance in diverse contexts. Covid-19 came after the launch of the SDGs, but the SDGs helped show how interconnected that crisis was with our other challenges. As a global pandemic, Covid-19 is connected with SDG #3 “Good Health and Well-Being” and SDG #8 “Decent Work and Economic Growth,” as the global economy took a significant hit and unemployment initially rose worldwide. Those at the lower end of the economic spectrum were disproportionately hit, which fits squarely into SDG #10 “Reduced Inequalities” and SDG #1 “No Poverty.” Throughout the world – certainly in the US – women bore the disproportionate brunt of increased work in the home, such as homeschooling children, which SDG #5 “Gender Equality” represents and connects with SDG #4 “Quality Education.”

The seventeen SDGs are linked to 169 targets, which are linked to 231 performance indicators. This breakdown focuses the higher-level SDGs into more specific domains and tracks measurable progress.Footnote 46 (Some targets have multiple performance indicators, resulting in more performance indicators than targets.) For example, SDG #12 “Responsible Consumption and Production,” has a suite of eleven targets (12.1, 12.2, 12.3, etc.) and thirteen performance indicators (12.1.1, 12.2.1, 12.2.2, 12.3.1, etc.).

Target 12.3 sets ambitious objectives: to halve per capita global food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reduce food losses along production and supply chains, including post-harvest losses, by 2030. Corresponding to this target is Performance Indicator 12.3.1, the “Global Food Loss Index,” which employs methodologies developed in partnership with the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) to gauge and monitor advancements.Footnote 47 Addressing food waste is crucial, as its contribution to climate change is so substantial that if it were a country, it would rank as the third-largest greenhouse gas emitter, behind only the US and China.Footnote 48 The connection between Target 12.3 and SDG #13 “Climate Action,” exemplifies the myriad interrelations that become evident upon a closer examination of the SDGs.

The Stockholm Resilience Center embraced the SDGs, relating them to planetary boundaries in their 2018 report, “Transformation Is Feasible: How to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals within Planetary Boundaries.” In it, they describe the adoption of the SDGs in 2015 and the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015 as a “global turning point.” Referring to the establishment of the SDGs, the report stated:

We have never before had such a universal development plan for people and planet. For the first time in human history the world has agreed on a democratically adopted roadmap for humanity’s future, which aims at attaining socially inclusive and highly aspirational socio-economic development goals, within globally defined environmental targets. Humanity’s grand ambition is surely to aim at an inclusive and prosperous world development within a stable and resilient Earth system.Footnote 49

The report also underlined the urgency of the challenges, highlighting the growing scientific consensus that humanity’s activities threaten to destabilize the Earth’s systems, putting future prosperity at risk. Establishing the SDGs represents a global triumph, but significant transformational action is still needed.

Benchmarking 101

Strong performances naturally attract attention. Benchmarking, a widespread practice across various industries and fields – from business to education and healthcare – provides a method for anyone, anywhere, to learn from top performers, aiming for continuous improvement. Nordic nations and Nordic-based companies frequently lead in many sustainability rankings, including the SDG Index and the Global 100 most sustainable corporations, making them ideal candidates for sustainability benchmarking.

Benchmarking involves four essential steps:

1. Identify strong performer(s).

2. Study how these performer(s) achieve strong results.

3. Examine the context of the strong performer(s) to understand differences and similarities with your own.

4. Assess how the lessons can be adapted to your local context, whether directly or with modification.

During the 1990s, industrial engineering and MBA programs across the US focused on benchmarking Japan due to its rapid advancements in efficiency measures. At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where I studied, we benchmarked Japan with heightened attention on the Japanese automobile company Toyota for its “lean manufacturing” successes. Texts like Toyota Production System and The Machine That Changed the World became required readings alongside classics like Frederick Taylor’s The Principles of Scientific Management.Footnote 50 Japanese terms like muda (waste), heijunka (level scheduling), kaizen (continuous improvement), kanban (pull system), and poka-yoke (error proofing) became essential components of the lexicon for efficiency professionals, regardless of their native language. In my first professional role as an industrial engineer at IBM’s largest manufacturing plant in Rochester, Minnesota, I applied these Japanese benchmarking lessons. Although manufacturing computers in the US presented a different context from automobile production in Japan, the insights from Toyota were adaptable, leading to notable improvements.

The rationale for benchmarking the Nordics on sustainability today mirrors the rationale for benchmarking Japan in the 1990s. Just as Japan made significant efficiency advances, the Nordics are recognized for their sustainability and societal well-being performances, making them essential subjects for associated benchmarking efforts.

More Sustainability Considerations

Triangle of Tensions: Efficiency–Equality–Sustainability

The twentieth-century economic discourse was largely dominated by what this work terms the “efficiency–equality tension.” This framework, exemplified in Arthur Okun’s seminal 1975 work Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff, conceptualized economic policy as a binary choice between maximizing market efficiency and promoting social equality. Neoclassical economists like Milton Friedman emphasized efficiency, arguing that market mechanisms would naturally optimize social outcomes, while welfare economists highlighted the necessity of redistributive policies to ensure equitable development.

However, this binary framework proved inadequate as environmental challenges emerged that markets failed to address. The presumption that price mechanisms would automatically resolve sustainability issues – such as the notion that timber price increases would naturally prevent deforestation – revealed a fundamental misunderstanding of ecological systems’ irreversibility. The dismissal of environmental concerns as “doomsday prophecies” by influential economists, including Friedman and Okun, reflected a theoretical blind spot that would have significant consequences.Footnote 51

While the shared error among economists to assume that markets would fix sustainability problems may be forgivable up to the mid twentieth century, by the latter part of the century, the problems had become too conspicuous to ignore. The 1987 Brundtland Report highlighted the undeniable changes human activity has had on our planet:

Over the course of [the twentieth] century, the relationship between the human world and the planet that sustains it has undergone a profound change. When the century began, neither human numbers nor technology had the power to radically alter planetary systems. As the century closes, not only do vastly increased human numbers and their activities have that power, but major, unintended changes are occurring in the atmosphere, in soils, in waters, among plants and animals, and in the relationships among all of these.Footnote 52

Hence, it is imperative to consider sustainability alongside efficiency and equality in this modern context.

Furthermore, we may be well served to shift our perspective from viewing these as tradeoffs to seeing them as tensions.

The concept of tensions, rather than tradeoffs, better captures the dynamic interplay between these forces. While tradeoffs suggest zero-sum relationships, tensions acknowledge the potential for productive synthesis and mutual reinforcement. As Okun observed, capitalism and democracy – representing efficiency and equality respectively – may actually require each other, with equality providing “humanity to efficiency” and efficiency bringing “rationality to equality.” This insight suggests the possibility of similar constructive tensions with sustainability.Footnote 53

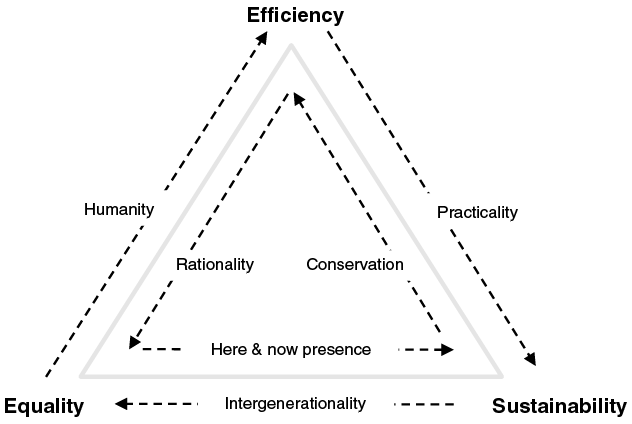

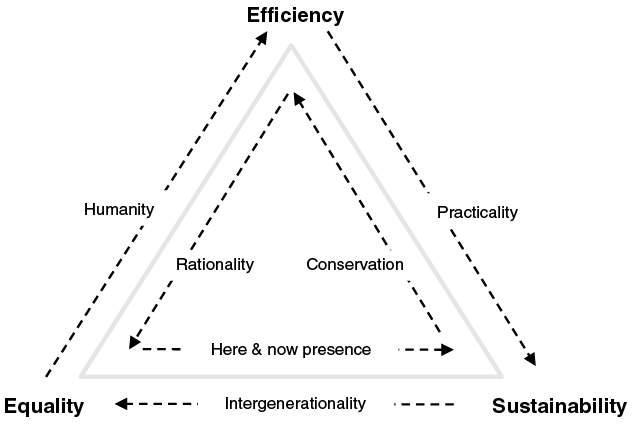

This work introduces the “Triangle of Tensions,” whereby sustainability constructively joins the efficiency and equality dimensions, as shown in Figure 2.4. This theoretical framework extends Okun’s binary model by incorporating sustainability as a third critical dimension of economic development, creating a more comprehensive analytical tool for understanding contemporary challenges. Okun articulated how efficiency and equality bring something of value to one another – rationality to equality and humanity to efficiency. Likewise, sustainability brings constructive considerations to efficiency and equality, as depicted within the Triangle of Tensions.

Figure 2.4 Triangle of Tensions.

Figure 2.4Long description

Triangle diagram titled Triangle of Tensions presents three foundational elements of sustainable development: Efficiency, Equality, and Sustainability. Each is positioned at one corner of the triangle.

- Efficiency is associated with Practicality and Rationality.

- Equality is associated with Humanity and here-and-now presence.

- Sustainability is associated with Conservation and Intergenerationality.

Arrows connect each corner, representing the constructive tensions between the three forces. The diagram emphasizes mutual influence rather than binary tradeoffs, highlighting how these elements together shape sustainable development.

The sustainability dimension enriches this framework in two crucial ways. First, it introduces conservation principles alongside efficiency considerations, challenging the assumption that maximum resource exploitation equates to optimal efficiency. Second, it expands the temporal scope of equality beyond contemporary distributional issues to encompass intergenerational justice. The sustainability dimension encourages consideration of equality for future generations, thereby addressing the potential problems associated with “present bias” identified in behavioral economics research.Footnote 54

The interplay of these three dimensions is illustrated in the popular children’s book The Lorax by Dr. Seuss, which presents an exemplary tension between short-term efficiency and long-term sustainability. The Once-ler invented the Super Axe Hacker, a symbol of industrial age efficiency that could whack off “four Truffula Trees at one smacker.” The Once-ler and his relatives secured handsome profits through the efficiency gains, but at an extreme cost to both sustainability and equality – devastating the environment while displacing the local inhabitants who depended on the Truffula Forest. This literary representation, published amid growing environmental awareness in the 1970s, captures the fundamental tensions between immediate efficiency, sustainability, and equality that characterize many contemporary development challenges.

The Triangle of Tensions framework helps illuminate complex policy decisions, such as when development projects potentially harm local biodiversity but bring much needed economic benefits to underprivileged communities. Like the endowment metaphor introduced earlier, which illustrates how overconsumption of principal diminishes regenerative capacity, the Triangle of Tensions framework demonstrates how privileging short-term efficiency over sustainability impairs Earth’s systems for future generations. Recognizing these three-way interactions – efficiency, equality, and sustainability – represents a foundational step toward understanding and managing the inherent complexities and negotiating the tensions in pursuing sustainable development.

The Greta Reality

In 2018, fifteen-year-old Greta Thunberg began a solo protest outside the Swedish Parliament during the nation’s hottest recorded summer, marked by wildfires. Her actions ignited a global youth movement demanding urgent climate action. Thunberg’s blunt statement – “I am doing this because you adults are shitting on my future” – succinctly captured the frustration of a generation facing the consequences of today’s inaction.Footnote 55

Despite Sweden’s top ranking in the SDG Index, Thunberg criticized her country for violating planetary boundaries and failing to safeguard the needs of future generations as outlined in the Brundtland definition of sustainable development. This critique applies broadly, as all OECD nations exceed planetary boundaries. The “Greta Reality” reflects how current overconsumption, particularly in developed nations, is effectively stealing future generations of their ability to meet their needs. Overconsumption today strips future generations of their freedom tomorrow. The Greta Reality also reflects the growing frustration among youth as they watch inaction by older generations in positions of power.

Denial of the Greta Reality persists, particularly in the US President Donald Trump personally attacked Thunberg, tweeting, “Greta must work on her Anger Management problem, then go to a good old fashioned movie with a friend! Chill Greta, Chill!”Footnote 56 Senator Dianne Feinstein condescendingly dismissed young climate activists, telling them, “Well, you know better than I do. So I think one day you should run for the Senate, and then you do it your way. But in the meantime, I just won a big election.”Footnote 57

Critics have dismissed Thunberg and other youth advocates for not offering detailed policy proposals or for speaking out on matters beyond climate, such as Thunberg’s more recent comments on the Israel–Palestine conflict. But expecting young people to produce comprehensive policy blueprints or remain confined to a single issue misses the point. Youth movements give voice to those who will live with the consequences of today’s decisions. They have every right to speak out about their future – and to demand that those in power take responsibility on matters that will directly impact their generation. These critiques risk distracting from the central issue: that continued denial and delay in addressing climate change are indefensible. The Greta Reality affirms that younger generations are justified in insisting their rights be respected, echoing themes in Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, which presents arguments for legal rights for future generations.Footnote 58

A significant legal victory in the US, Held v. Montana, where a judge ruled that the state violated children’s constitutional right to “a clean and healthful environment,” exemplifies this growing recognition of the rights of future generations.Footnote 59 The case represents a step toward protecting future generations and signals a potential shift from denial to confronting the Greta Reality.

Doughnut Economics

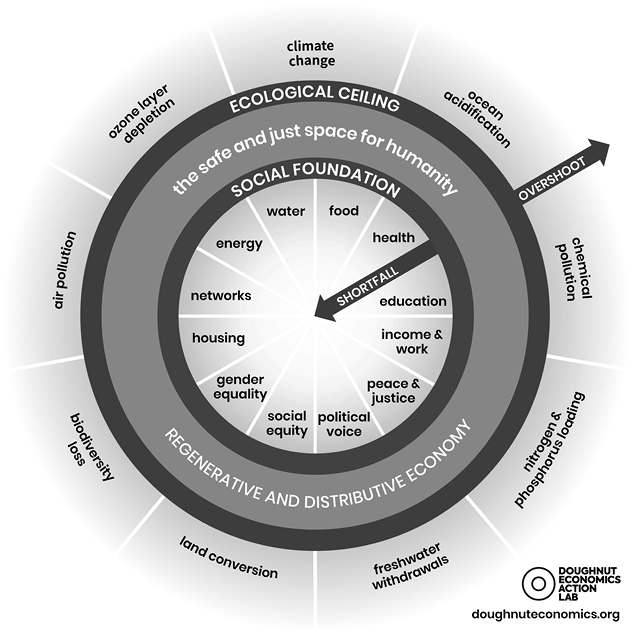

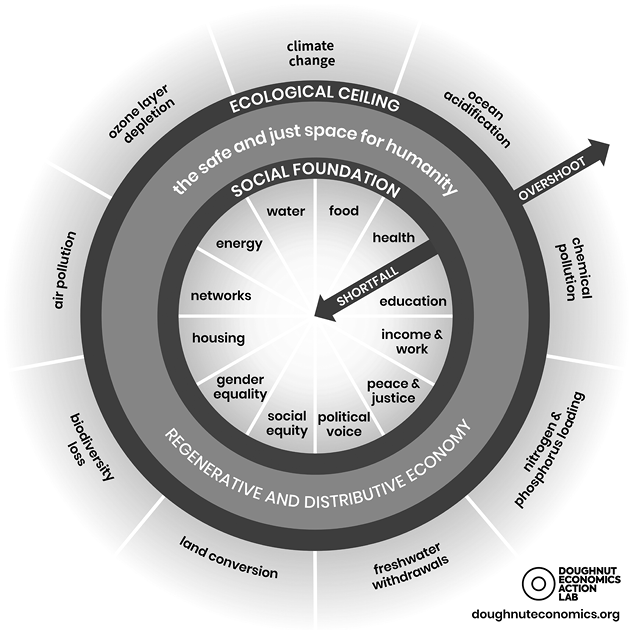

In her influential 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Kate Raworth challenges twentieth-century economists’ notions of limitless growth and disregard for sustainability.Footnote 60 Raworth proposed a model that resembles a doughnut, as shown in Figure 2.5, leveraging the round Planetary Boundaries figure as an “ecological ceiling” and the SDGs as the “social foundation.”Footnote 61

Figure 2.5 Doughnut economics.

Figure 2.5Long description

Circular doughnut diagram from the Doughnut Economics Action Lab.

- The inner ring, labeled Social Foundation, includes dimensions such as water, food, health, education, income & work, peace & justice, political voice, social equity, gender equality, housing, networks, and energy.

- The outer ring, labeled Ecological Ceiling, includes boundaries like climate change, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, nitrogen & phosphorus loading, freshwater withdrawals, land conversion, biodiversity loss, air pollution, and ozone depletion.

The space between the rings is labeled the safe and just space for humanity. Arrows show Shortfall pointing inward and Overshoot pointing outward.

Doughnut Economics balances environmental safeguards, using the Planetary Boundaries as a UCL, with the fulfillment of fundamental human needs – clean water, food, and healthcare – represented by the SDGs as the LCL. Doughnut Economics visually represents meeting the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

Doughnut Economics mirrors the Swedish principle of lagom, a word that implies moderation or balance that signifies “the right amount.” Lagom is more than a concept – it’s a way of life. I felt its ubiquitous presence upon moving to the Nordics. My new colleague scolded me soon after arrival for violating the norms of work–life balance. Noticing my early arrivals and late departures, my colleague asked, “Can’t you get your work done during regular hours? Can’t you work efficiently? Don’t you want to spend your free time with your family?”

Doughnut Economics reflects the principle of lagom, ensuring a good quality of life for all without exceeding Earth’s regenerative capacities. Achieving this balance requires the deliberate and ongoing management of the tensions between efficiency, equality, and sustainability. The Nordics have openly embraced Doughnut Economics. In 2020, the City of Copenhagen adopted Doughnut Economics as its guiding economic framework.Footnote 62 Various Nordic case studies, from the Oslo fjord to Finnish municipalities, provide tangible examples of its successful implementation.Footnote 63 In 2022, munkmodell (“doughnut model” in Swedish) was added to Swedish dictionaries, recognized by the Swedish Language Council as a representation of an economic system where the goal is to meet people’s needs within the limits of the planet.Footnote 64

Half-Earth

E. O. Wilson was an American biologist, researcher, theorist, naturalist, and author best known for his ecology and biodiversity conservation work. In 2016, his book Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life was published, in which he advocated for designating half of the Earth’s land and marine environments as protected, human-free zones to safeguard biodiversity and prevent mass extinctions. “Human beings are not exempt from the iron law of species interdependency,” wrote Wilson. “The biosphere does not belong to us; we belong to it.”Footnote 65 Half-Earth confronts the reality that humankind is violating Planetary Boundaries and eradicating biodiversity in the process, with dire consequences for future generations of humankind.

Wilson advocates for preserving vast areas of forests, grasslands, deserts, wetlands, and marine zones. However, it’s not just about the total area summing up to 50 percent of the Earth, but connecting the preserves is vitally important as well, where an essential aspect of Wilson’s proposal is to establish wildlife corridors – or biodiversity corridors – to ensure connectivity between protected areas. Such corridors include narrow strips of protected land to connect larger preservations and physical structures like wildlife overpasses, allowing species to migrate, interbreed, and adapt to environmental changes.

Wilson’s proposal may appear radical, but it reflects the scale of the challenges and the elevated need for extreme cooperation and coordination to address them. He writes, “The Half-Earth proposal offers a first, emergency solution commensurate with the magnitude of the problem: I am convinced that only by setting aside half of the planet in reserve, or more, can we save the living part of the environment and achieve the stabilization required for our own survival.”Footnote 66

Overcoming Denial

Overcoming denial in the US is especially difficult, given entrenched economic interests and deep political polarization that obscure the scale of sustainability challenges. The issue of science denial obstructs constructive and rational discourse. A 2019 Guardian headline encapsulated this challenge: “US Is Hotbed of Climate Change Denial,” a claim extensively substantiated by academic literature.Footnote 67

During her 2019 visit to the US, Greta Thunberg was asked whether climate change is approached differently in Sweden than in the US. She responded that in the US, climate change is treated as something you can choose to believe in, whereas in Sweden, it is accepted as a scientific fact.Footnote 68

American corporations realized that casting doubt on scientific consensus can be a powerful strategy to delay regulation and protect profits. As detailed in Merchants of Doubt, the tobacco industry – led by companies such as Philip Morris – pioneered science denial tactics to obscure health risks and resist regulation.Footnote 69 The report America Misled: How the Fossil Fuel Industry Deliberately Misled Americans about Climate Change shows how fossil fuel companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron later adopted these same strategies to challenge the scientific consensus on climate change and delay policy interventions such as carbon taxes or carbon markets designed to internalize negative environmental externalities.Footnote 70 Similarly, as documented in Soda Science, Coca-Cola funded academic research that diverted attention from the harms of sugary beverages.Footnote 71

Regulators and lawmakers are not unaware of these denial tactics. In 2019, Professor David Michaels of George Washington University testified before the House Natural Resources Committee in a hearing titled “The Denial Playbook: How Industries Manipulate Science and Policy from Climate Change to Public Health.”Footnote 72 His testimony drew on The Disinformation Playbook, a report from the Union of Concerned Scientists, which outlines how business interests deceive, misinform, and buy influence at the expense of public well-being.Footnote 73

Across industries, American capitalism’s profit imperative has consistently incentivized the distortion of science to protect short-term gains at the expense of public health and planetary well-being. Naomi Oreskes, co-author of Merchants of Doubt, has highlighted how this denial pattern extended into the Covid-19 pandemic. In response to public health measures like mask mandates, critics equated collective action with authoritarian socialism – typified by protests and declarations such as, “We don’t live in a communist country! This is supposed to be America.”Footnote 74 Such reactions reflect a deep-seated resistance to perceived constraints on individual freedom – even when collective action is essential. This resistance draws from the American identity rooted in rugged individualism and reinforced by neoliberal ideology, which elevates markets as the preferred problem-solvers and casts suspicion on government intervention. Within this framework, American capitalism doesn’t merely permit science denial – it rewards it. When scientific consensus threatens profits or justifies regulation, powerful actors are incentivized to manufacture doubt and stall reform.

Parting Reflections

The twentieth century’s dramatic economic growth, fueled by industrialization and the continued rise of capitalism, came at a steep cost: environmental degradation and deepening inequalities. As a result, the field of sustainable development emerged, emphasizing the inseparable links between economic, environmental, and social domains.

Today’s global sustainability crises demand coordinated, transformative action. Yet, denial remains pervasive, particularly in global seats of power, whether explicitly through outright rejection or implicitly through insufficient action. Humanity faces a choice: maintain denial or confront the challenges head-on. In American capitalism, denial often proves profitable, posing a major obstacle to sustainable progress. As Upton Sinclair observed, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.”Footnote 75 While Nordic societies are not without criticism, their functioning democracies enable reality-based policymaking; by contrast, in the US, entrenched oligarchic interests benefit from denial and actively obstruct democratic mechanisms that could deliver necessary reforms.

To fully meet Brundtland’s definition of sustainable development – ensuring present needs are met without compromising the future – requires sweeping changes in policy, business practices, and individual behavior. Policymakers must create strong incentives for sustainable practices and impose penalties on environmentally harmful actions, while business leaders must proactively adopt and champion sustainability initiatives. Economic models must encourage long-term stewardship, viewing the Earth as a precious endowment. Solutions must integrate technological and policy innovations with circular economy principles alongside nature-based approaches and Indigenous traditions emphasizing stewardship of resources and living in harmony with nature.

Achieving the ongoing balance between efficiency, equality, and sustainability requires collaboration across sectors and borders, with sustainable development as the ultimate guiding purpose. As we examine different varieties of capitalism in the next chapter, this imperative raises crucial questions: How can market economies be structured to reward sustainability with profits? What institutional arrangements best enable the collaboration to address mounting environmental and social challenges?

The Nordic experience offers compelling insights into how capitalism can be shaped to advance sustainable development, offering lessons that could help evolve American capitalism.